1. Introduction

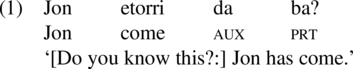

This article explores the interaction between intonation and syntax in expressing clause type and speech act, as well as the role that discourse particles play in this relationship. For this purpose, I will focus on a Basque structure, which has thus far not been researched sufficiently, presented in Example (1).

The pragmatic interpretation of the sentence in Example (1) is not that of a canonical declarative or interrogative sentence. Rather, the speaker asks the addressee about whether (s)he knows the sentence content; it is thus an instance of a noncanonical question. I will denominate this structure ‘Knowledge Confirmation Question’ (KCQ).Footnote 2

Three aspects interact in a KCQ: (i) a declarative clause-type, (ii) interrogative intonation and speech act and (iii) the discourse particle ba. Thus, KCQs are especially interesting for the study of the pragmatic aspect of the clause, more precisely, the interaction between clause type and speech act, and how discourse particles modify the speech act of the sentence. In this work, I will present a formative approach to Basque KCQs, focusing first on each defining aspect individually, and then on the interaction between all of them.

This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, I will talk about the correlation between clause types and speech acts. In Section 3, I will analyse the discourse particle ba within the Basque discourse particle system and its meaning in different clause types. Section 4 will bring together all the components addressed in previous sections in order to propose an analysis of KCQ sentences from a syntax–prosody interface. In Section 5, I will present the conclusions.

2. Clause types and speech acts

2.1. Disentangling clause types and speech acts

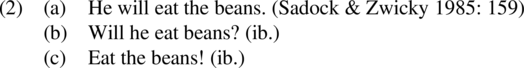

Clause types are specific forms of sentences that are associated with some canonical discursive function. Linguistic theory assumes that every clause must be typed (Cheng Reference Cheng1997: 29), that is, identified as declarative, interrogative or imperative, which are considered to be universal (Sadock & Zwicky Reference Sadock, Zwicky and Shopen1985, Portner Reference Portner2004), or other clause types that may be present in a language.Footnote 3 Example (2) shows examples of different clause types in English, declarative, interrogative and imperative, respectively.

In English, declarative sentences are recognisable by SVO word order with overt subject in Example (2a), interrogative sentences undergo subject-auxiliary inversion (or receive do-support if there is no auxiliary) in Example (2b) and imperative sentences lack an overt subject in Example (2c). Other languages use other mechanisms beyond word order and presence of subject for clause typing. Declaratives are usually the most unmarked clause type, deeming the regular word order in embedded clauses unmarked, but in some languages, they may be marked too, for example, by particles, such as Gascon que (Morin Reference Morin2008), or y(r)/r (affirmative) and ni(d) (negative) in Welsh (Sadock & Zwicky Reference Sadock, Zwicky and Shopen1985: 166). Yes-no questions are marked in most languages by final rising intonation, although most languages also use some other morphological or syntactic means: question particles, verb morphology, word order, etc. (Dryer Reference Dryer, Dryer and Haspelmath2013). Some widespread grammatical mechanisms to mark imperatives are verbal morphology, sentence final particles or imperative verbal mood.

Clause types are usually linked to some canonical pragmatic impact in discourse. Declaratives convey ‘assertions, expressions of belief, reports’ etc. (Sadock & Zwicky Reference Sadock, Zwicky and Shopen1985: 165). Interrogative sentences regularly ‘try to make the addressee […] provide a particular piece of information’ (Krifka Reference Krifka, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011: 1742). Finally, imperatives are usually associated with orders (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann, Matthewson, Meier, Rullmann and Zimmermann2021).

Things are more complicated than a first approach may suggest, however. Aside from clause type, which is the syntactic part of the sentence, we should also take into account the speech act conveyed by a sentence, that is, its pragmatic dimension. Austin (Reference Austin1962) broached the observation that not all sentences convey a statement that can be true or false; instead, when a speaker says something, (s)he performs an act, that is, a speech act. Besides the locutionary act, that is, what is explicitly said, the speech act has two other main dimensions, namely, the illocutionary act (i.e. what the speaker intends with the speech act) and the perlocutionary act (i.e. the effect of the speech act in the hearer) (Austin Reference Austin1962: 98–101). In what follows, I will focus on the illocutionary dimension of speech acts.

On this matter, two issues must be taken into account. First, a clause type does not express a single speech act but a certain range of them. For instance, interrogative sentences may express, for example, requests in Example (3a) and invitations in Example (3b) but also imperatives may convey requests in Example (3c) and invitations in Example (3d).

Examples like Example (3) lead us to think that there is no correspondence between clause type and speech act. Searle (Reference Searle1976) explores the relation between syntax and speech act, and shows that clause type does not directly mark the speech act of a sentence. In fact, an interrogative clause, for instance, may not convey a speech act of assertion.Footnote 4 Thus, clause type conditions the speech act, but it is not a means to explicitly express the exact speech act that the speaker wants. In this regard, Allan (Reference Allan2006) proposes that each clause type has a primary illocution (PI) that conditions the possible illocutions of an utterance but without completely determining it.Footnote 5

A second issue is that of sentences that seem to combine two clause types at once. The classical example are ‘declarative questions’ in Germanic languages (Gunlogson Reference Gunlogson2003, Reference Gunlogson2008), a type of noncanonical questions.Footnote 6

Declarative questions may at first sight seem to challenge the claim that ‘the types are mutually exclusive, no sentence being simultaneously of two different types’ (Sadock & Zwicky Reference Sadock, Zwicky and Shopen1985: 158), since sentences such as Example (4) appear to be declaratives but, at the same time, have the questioning properties of yes–no questions. If we look closer, however, it seems more reasonable to approach declarative questions as declaratives expressing an information-seeking speech act.

Comparing declarative questions, regular declaratives and regular interrogatives help us discern the pragmatic contributions of the clause type and the speech act, as well as the linguistic means to express each of them. Regarding the pragmatic aspect, declarative questions seem to combine the speaker’s commitment and inquisitivity.Footnote 7 Here, I understand commitment as ‘propositions […] publicly taken by the participants in a conversation as being true’ (Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010: 84), and inquisitivity as offering the addressee different alternatives to commit. Unlike interrogative sentences, regular declaratives are usually linked to assertions (Stalnaker Reference Stalnaker and Cole1978, Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010), which suggests that the declarative clause type contributes to the speaker’s commitment. On the other hand, both interrogative sentences and declarative questions have an inquisitive component, suggesting that it is derived from the questioning speech act rather than from the clause type, since they both share the inquisitive component, but they have different clause types. Thus, in general terms, it seems that the declarative clause type marks the speaker’s commitment, whereas the rising intonation present in both declarative questions and interrogative sentences conveys inquisitivity. Work on intonation shows that there is not one-to-one correspondence between speech act and intonation pattern (Thorson et al. Reference Thorson, Borras-Comes, Crespo-Sendra, del Mar Vanrell and Prieto2015), but it is clear that intonation plays a role in discerning between different speech acts, for example, between information-seeking and confirmation-seeking questions (Vanrell et al. Reference Vanrell, Mascaró, Torres-Tamarit and Prieto2012).Footnote 8 Thus, declarative questions would be the result of the combination of both components, as Gunlogson (Reference Gunlogson2003, Reference Gunlogson2008) suggests.

2.2. The syntax of the discursive dimension of sentences

Let us now turn to the syntactic account for this dissociation between clause type and speech act. Traditionally, clauses were assumed to be typed in the left periphery of the clause, that is, in the complementizer phrase (CP). Rizzi (Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) proposed a more explicit account for the left periphery, where the CP was split into four phrases: ForceP, TopicP, FocusP and FinitenessP. However, in Rizzi’s account, there was no distinction between clause type and speech act, and both clause type and speech act were encoded in ForceP. Such analysis leaves no room for the data we have discussed in the previous section.

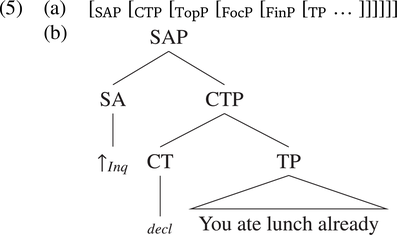

Coniglio & Zegrean (Reference Coniglio, Zegrean, Aelbrecht, Haegeman and Nye2012), in analysing evidence of German, Italian and Romanian discourse particles, propose splitting ForceP into two projections: a higher phrase that marks the speech act of the clause and a lower phrase where the clause type is encoded as in Example (5a).Footnote

9 Such an analysis succeeds in accounting for the dissociation between clause type and speech act. Thus, a declarative question like Example (4) could be analysed as Example (5b), where intonation (marked by

![]() $ \uparrow $

in Example (5b)) would encode the speech act of the sentence.

$ \uparrow $

in Example (5b)) would encode the speech act of the sentence.

The role of intonation in a speech act and its relation to clause type has been extensively discussed in literature. Truckenbrodt (Reference Truckenbrodt, Maienborn, von Heusinger and Portner2011), who has worked on the meaning dimension of intonation, concluded that intonational morphemes are linked to different speech acts, for example, English H* contour conveys assertion, whereas H- is used for questioning. Similarly, Heim & Wiltschko (Reference Heim and Wiltschko2020a, Reference Heim, Wiltschko, Kentner and Kremersb) have also argued that intonation plays a role in commitment and engagement management in conversation. They go a step further in proposing that speech acts do not form a natural class but instead arise from the combination of clause type and different values of commitment and engagement conveyed by intonation.

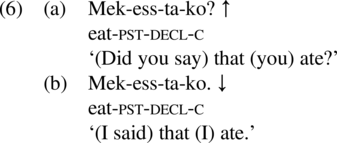

A different data set leads An (this volume) to draw a similar conclusion to Coniglio & Zegrean (Reference Coniglio, Zegrean, Aelbrecht, Haegeman and Nye2012) and Heim & Wiltschko (Reference Heim and Wiltschko2020a, Reference Heim, Wiltschko, Kentner and Kremersb), regarding both the distinction between clause type and speech act and the role of intonation in speech act marking. He analyses Korean stranded embedded clauses (SECs), finite verbs with clause typing particles and embedding complementisers that are used in main clause contexts. Crucially, the clause typing suffix of the verb does not mark the speech act of the sentence, which is independently marked by intonation.Footnote 10 , Footnote 11

An (this volume) proposes that the inquiring illocutionary force of the sentence is encoded in the speech act domain, following theories of syntactic speech act domain above ForceP (a.o. Speas & Tenny Reference Speas, Tenny and di Sciullo2003, Hill Reference Hill2007a, Reference Hillb). Although from a different perspective, this proposal does not differ from Coniglio & Zegrean (Reference Coniglio, Zegrean, Aelbrecht, Haegeman and Nye2012), in the sense that both structures distinguish clause type and speech act. Compare Example (5b) to Example (7).

In light of these works, it seems reasonable to consider a separation between clause type and speech act also in the syntactic domain.

As this article deals with a noncanonical question in Basque, in the next subsection, I will look at clause type and speech act marking in Basque.

2.3. Clause types and speech acts in Basque

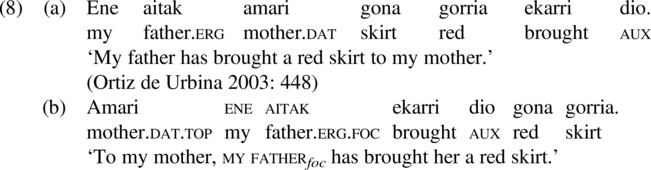

Contrary to English, Basque has a highly free word order, and the surface word order is not necessarily determinant in clause type marking. It is commonly agreed that declarative sentences have a neutral SOV order (Ortiz de Urbina Reference Ortiz de Urbina, Hualde and de Urbina2003: 448), as in Example (8a), but information structure (i.e. topicalisation, focalisation, etc.) plays a role in surface word order: foci must appear immediately to the left of the verbal complex (verb + auxiliary) and topics appear before foci (a.o. Elordieta Reference Elordieta2001), as in Example (8b).

Regarding interrogatives, ‘yes/no questions need not be signalled by any mark other than interrogative intonation’ (Etxepare & Ortiz de Urbina Reference Etxepare, de Urbina, Hualde and de Urbina2003: 467). Some researchers claim that verb fronting may also be used as a means of typing an interrogative clause (Etxepare & Ortiz de Urbina Reference Etxepare, de Urbina, Hualde and de Urbina2003: 468). Verb-initial is the neutral word order in interrogative clauses according to Ortiz de Urbina (Reference Ortiz de Urbina, Franco, Landa and Martin1999), who adapts the split–CP hypothesis by Rizzi (Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) to Basque, and proposes that the highest CP phrases, including ForceP, are head initial. In interrogative sentences the finite verb would move to Force0, causing a verb-initial surface order. However, the finite verb may appear in initial position in declaratives too, which suggests that word order is not a clause type marking tool but simply a means of information structure regulation in every clause type.

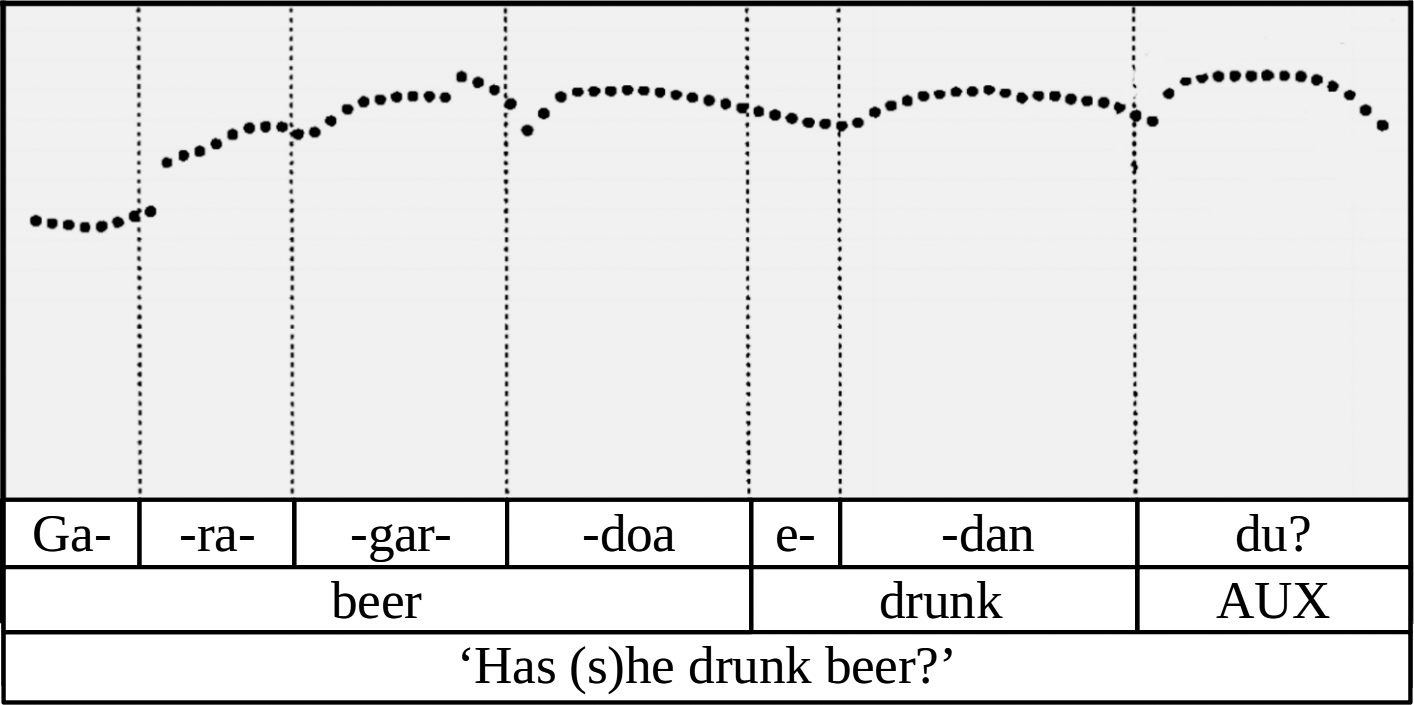

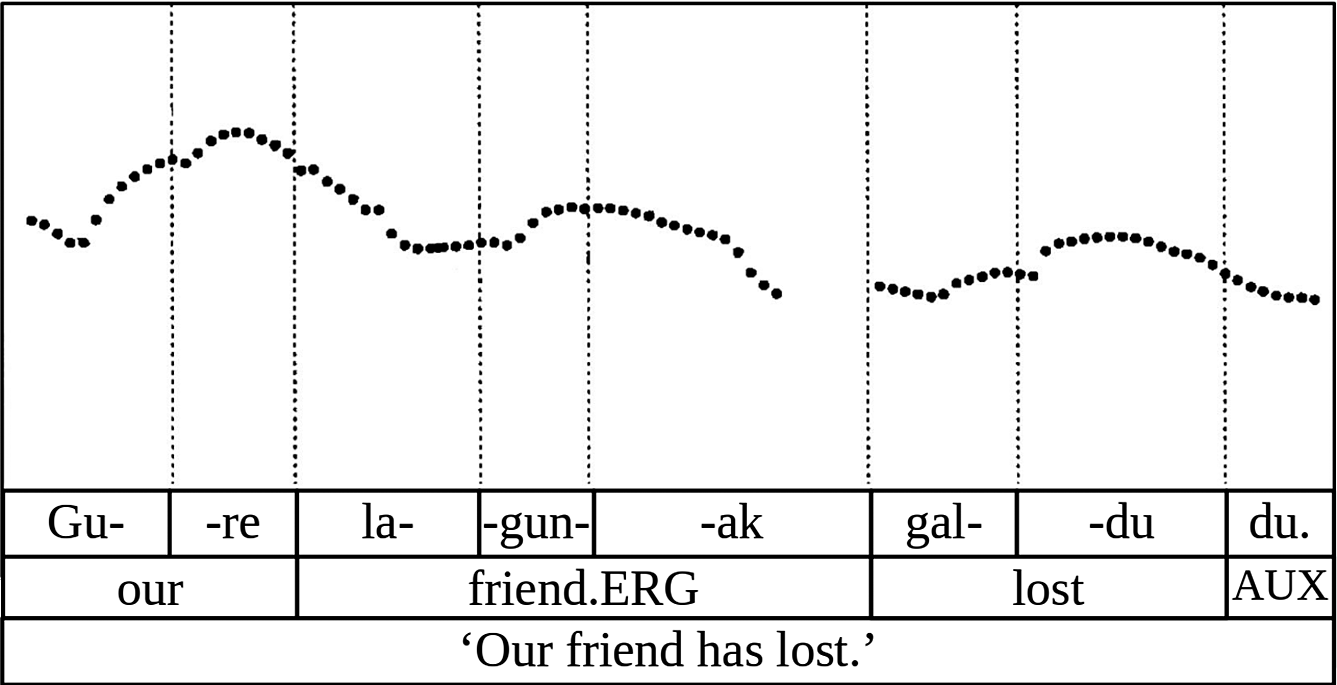

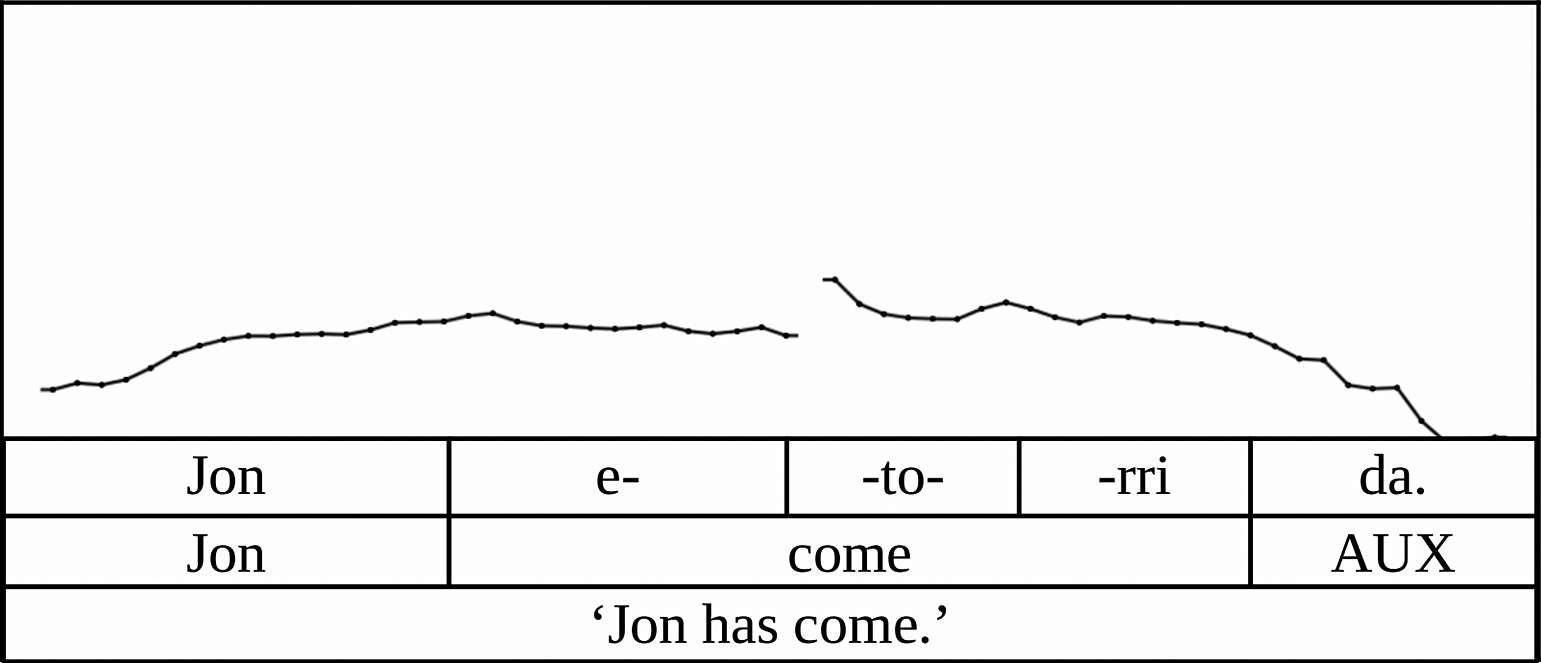

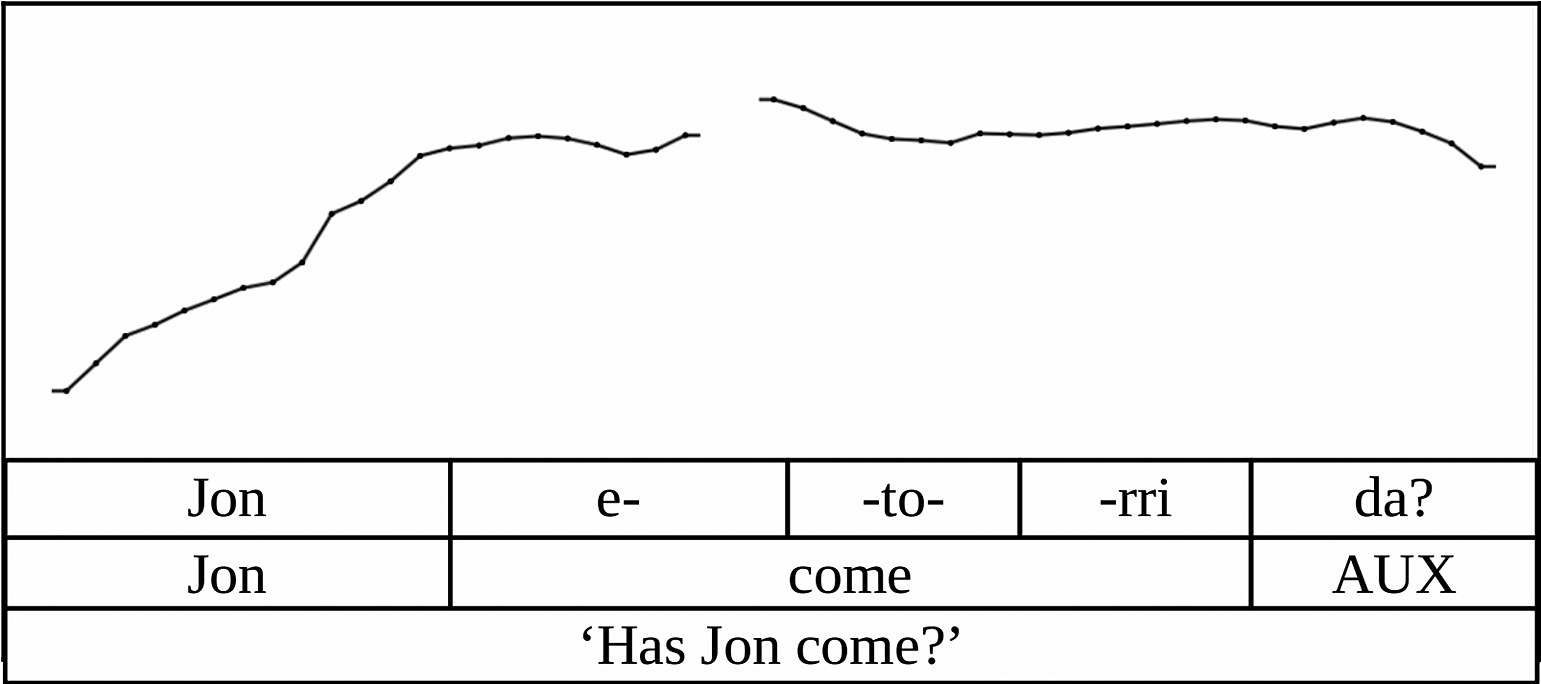

Interrogative sentences must have a special intonation. In central Basque, ‘the pitch rises at the first stressed syllable and continues high up to the last syllable of the sentence, where it falls’ (Elordieta & Hualde Reference Elordieta, Hualde and Jun2014: 456), as can be seen in Figure 1. In contrast, ‘pitch–accents in neutral declaratives are generally rising from a valley at the beginning of the stressed syllable’ (Elordieta & Hualde Reference Elordieta, Hualde and Jun2014: 444), as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 1 Intonation of a neutral yes/no interrogative sentence (Elordieta & Hualde Reference Elordieta, Hualde and Jun2014: 456).

Figure 2 Intonation of a neutral declarative sentence (Elordieta & Hualde Reference Elordieta, Hualde and Jun2014: 443).

As with the surface form only intonation distinguishes declaratives from interrogatives in Basque, and as KCQs have their special intonation, further tests beyond intonation will be needed to see whether noncanonical questions like KCQs have declarative or interrogative properties.

3. The discourse particle ba

3.1. A brief overview of Basque discourse particles

Discourse particles are common in many languages, including Basque (a.o. Elordieta Reference Elordieta1997, Haddican Reference Haddican, Arteatx, Artiagoitia and Elordieta2008, Zubeldia Reference Zubeldia2010, Etxepare & Uria Reference Etxepare, Uria, Fernández and de Urbina2016, Korta & Zubeldia Reference Korta and Zubeldia2016, Monforte Reference Monforte2020). Cross-linguistic research has distinguished two types of particles. Some particles merge in the TP field. In Basque, they appear to the left of the tensed verb. I will refer to this type as inner particles (InnPs). Other particles merge in the left or right periphery, and in Basque, they surface on the left or right edges of the clause. I will name them outer particles (OutPs). The former are generally evidential or epistemic particles that modulate the illocutionary strength of the proposition, whereas the latter regulate the way in which the utterance is to be understood in the conversation. The hearsay evidential omen is an example of an InnP, as in Example (10a), and ba, which will be analysed in depth in the remainder of the paper, is an instance of an OutP, as in Example (10b).

3.2. Exploring the meaning dimension of ba

Basque discourse particles and, specifically ba, have not received much attention in formal linguistics. According to grammars and dictionaries (Euskaltzaindia 1990, Mitxelena & Sarasola 1987-Reference Mitxelena and Sarasola2005, de Rijk Reference de Rijk2008), ba has a consecutive meaning, similar to beraz ‘therefore’ but with a ‘weaker illocutive meaning’ (de Rijk Reference de Rijk2008: 620). However, these approaches are too vague. Here, I will present pragmatic contexts to test the pragmatic felicity of ba, and I will analyse the meaning of the particle by using the conversational models developed by Farkas & Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) and Malamud & Stephenson (Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014).Footnote 12

Let us start with initial ba in regular declarative sentences. Without a previous context, initial ba is not felicitous. Observe (11).

When it follows a previous intervention, however, ba is felicitous. In such cases, it conveys that the speaker accepts the previous intervention, and that the utterance is a reaction to it.

Example (12) shows that ba accepts the previous move, linking the utterance as a response to the previous intervention. It marks acceptance that the speaker tackles the issue raised by the addressee. I will call this use the response-marker use of ba.

In imperative sentences, initial ba has a similar effect.

But final ba has a different effect.Footnote 13 In final position, ba conveys that the speaker has already given that order and wants to insist on it. Let us see it in this example, as in Example (14).

In Example (14), both the speaker and the addressee are aware that the speaker has uttered the command but the addressee has not obeyed, so the speaker uses ba to underline that the order is already given.

This use of ba marking the utterance as known is also observed in declaratives. This is best observed when final ba is used along with bai ‘yes’.

In Example (15), the expression bai ba conveys that Miren was already committed to the idea that Ane did not want to pay so much, and suggests that her previous words implied that idea. As in the case of imperatives, ba in final position expresses that the utterance was already known by the speaker before the sentence was uttered.

So far, we have seen that ba has different functions in initial and final positions. Sentence-initially, it expresses that the speaker accepts the previous intervention, whereas in sentence final position presents the sentence content as already known. In the next subsection, I will try to give a unitary pragmatic analysis for ba and derive its two meanings from a base meaning.

3.3. Towards a formal account of the pragmatics of ba

If we try to account for the impact of ba in discourse using the discourse model developed by i.a. Farkas & Bruce (Reference Farkas and Bruce2010) and Malamud & Stephenson (Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014), we will realise that this model is too narrow to do so.

Let us try to capture the meaning of ba in Example (12a), for instance. In this example, the propositional content p is ‘it is recommended to have studied Latin beforehand’, which is added to the top of the stack on the Table and to the DC S. Ba‘s function is to mark that the speaker is aware and accepts the previous utterance q, ‘what do you recommend for this subject?’ However, this meaning contribution cannot be accounted for by the tools offered by Malamud & Stephenson (Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014). First, it does not make sense to add q to the current or projected DCs of the speaker because it is an interrogative sentence that does not express commitment. If q were a declarative as in Example (12b), adding q to DC S would not solve any problem because the speaker does not commit to the addressee not having studied Latin before. Likewise, positing q on the Table is not opportune here. The addressee her/himself proposes q when (s)he utters it and, moreover, the speaker removes it from T when (s)he answers p. The last option is to add q to the CG, but this is not the case either. The CG comprises all the propositions that all participants commit to, which is not the case, since the speaker himself does not commit to q, as we have just mentioned.

In order to adapt the model to account for ba, I propose to add a new notion: the participants’ Doxastic State (DS), defined in Example (16).

Ba has the function of regulating the DS. I propose that ba expresses that an utterance was already in the speaker’s DS prior to the utterance time. Example (16) shows this in a more formal way.

The difference between initial and final ba is the proposition that ba adds to DS S. When ba is in initial position, it refers to the previous utterance (q); when ba is in final position, it refers to the speaker’s utterance itself (p).Footnote 15

Thus, Mikel’s utterance in Example (12a): (i) adds p (Mikel’s utterance) to DC S and to the top of the stack in T, and (ii) adds q (the student’s previous intervention) to DC S, indicating that q was already at the speaker’s DS before his utterance, that is, p.Footnote 16 In contrast, in an example like Example (15), the speaker adds p to DC S, to T and to DC S, indicating that p was already in the speaker’s knowledge, expressing that p is already known.

Thus far, I have made a review on the syntactic dimension of clause types and speech act, and I have proposed a pragmatic analysis for ba. In the next section, I will look at a Knowledge Confirmation Question in Basque, which contains this same ba, albeit with some different properties.

4. Knowledge Confirmation Question as the result of the syntax–prosody interface

Let us now focus on the structure of Basque KCQs.

KCQs are characterised by: (i) a declarative-like syntax, (ii) a question-like intonation, and (iii) the discourse particle BA. In this section, I will analyse the meaning of this utterance type as a result of the interaction between three elements: clause type, speech act and the discourse particle ba.

4.1. KCQs are declarative sentences and question speech acts

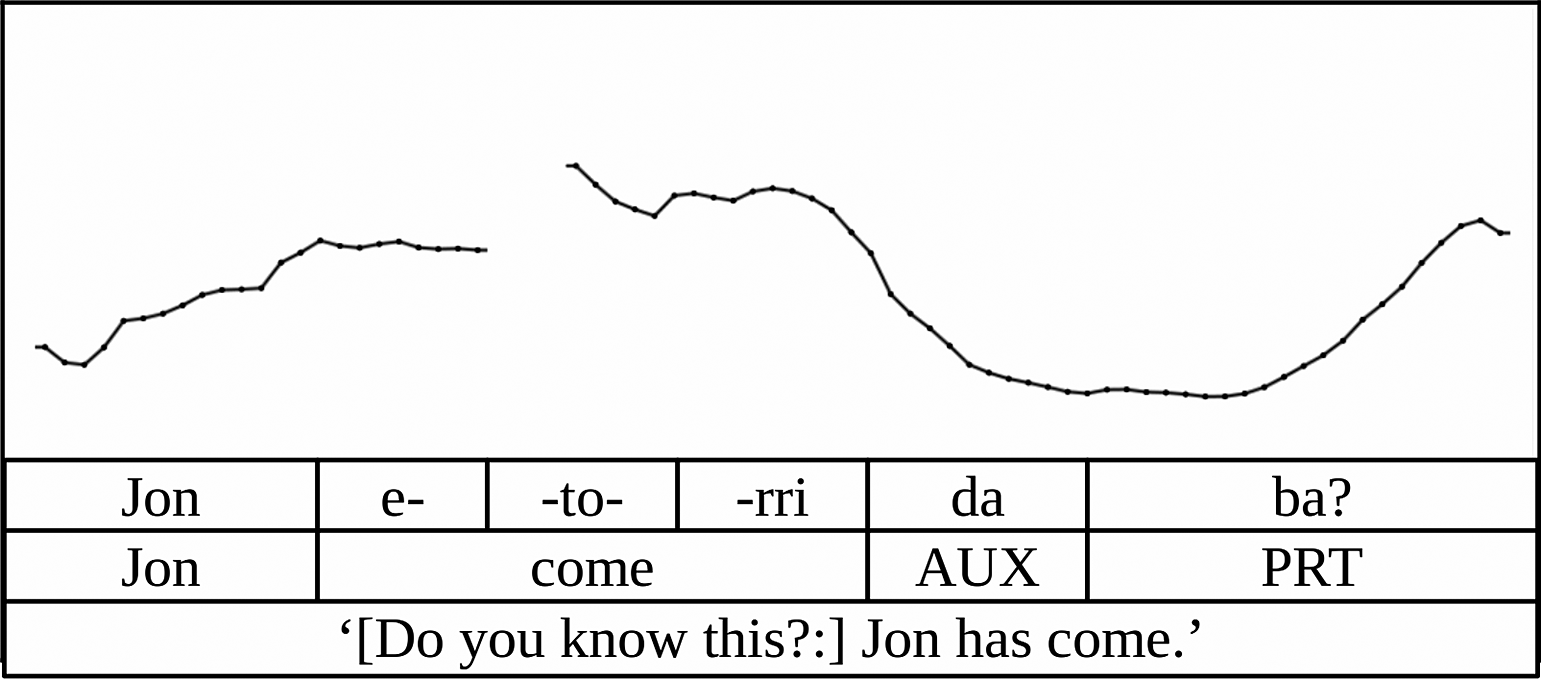

Let us first look at the intonation of KCQs (Figure 3) and compare it to the intonation of regular declarative sentences (Figure 4) and information-seeking questions (Figure 5), since it has not been done before.Footnote 17

Figure 3 Intonation curve of a KCQ utterance.

Figure 4 Intonation curve of a declarative sentence.

Figure 5 Intonation curve of a yes/no interrogative sentence.

From the intonational data shown so far, I conclude that the intonation pattern of KCQs is a combination between that of regular declaratives and interrogatives. First, from an impressionistic point of view, it seems that KCQs show a higher general pitch range than declaratives, although it is not as high as in interrogatives. Second, the intonation falls between the main verb and the auxiliary, as occurs in declaratives and contrary to interrogatives. Finally, there is a final rise on the particle ba Footnote 18 and the utterance ends in a high intonation followed by a little fall as in interrogatives, as opposed to declaratives, which end low. Thus, I conclude that the general high pitch range and the final rise cause the KCQ to be perceived as inquisitive in conversation.Footnote 19

Whereas intonation presents a mixed pattern, now I will offer arguments to defend the declarative nature of KCQs that syntax clearly shows. First, when any interrogative inner particle, for example, al, appears along with ba, the utterance cannot have a KCQ interpretation. Al is generally considered to have a yes–no interrogative clause typing function (Euskaltzaindia 1987, Hualde & Ortiz de Urbina Reference Hualde and de Urbina2003). When both al and ba appear in a question, the result is a yes-no question that conveys counter-expectation and surprise, but a KCQ interpretation is ruled out. Consider Example (19).

Second, polarity items (PIs) like inor ‘anyone’ may appear in regular interrogative sentences as in Example (20a), as well as in al questions with ba as in Example (20b), but they are ungrammatical both in KCQs in Example (20c) and in declaratives in Example (20d).

Let us now move on to interpretation. Declarative sentences convey a commitment of the speaker towards the sentence content (e.g. Stalnaker Reference Stalnaker and Cole1978, Farkas & Bruce Reference Farkas and Bruce2010, Malamud & Stephenson Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014). KCQs express such a commitment too. I draw this conclusion from the following pragmatic contexts. First, when the speaker utters a KCQ, the addressee may respond that (s)he is lying. This is only possible if the addressee perceives that the speaker commits to the sentence content. Declarative sentences produce the same effect on the addressee, but interrogative sentences do not. This is shown in Example (21).

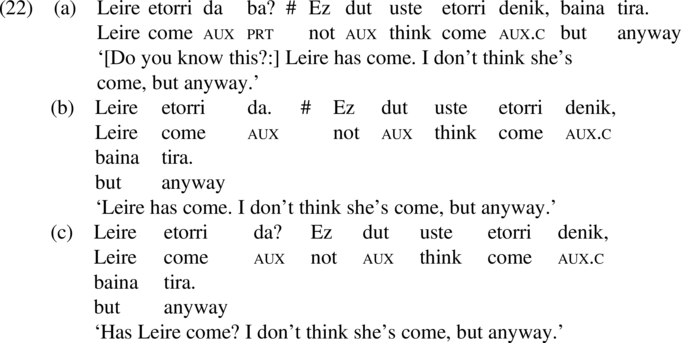

Moreover, if a speaker utters a KCQ and then says something that is incompatible with the sentence content of the KCQ, it is perceived as a contradiction as in Example (22a). Again, this effect happens with declarative sentences as well as in Example (22b), but it does not happen with interrogatives as in Example (22c).

So far, I have given syntactic evidence and pragmatic contexts like those presented in Examples (21) and (22) that show that, in KCQs, the speaker commits to the sentence content. These data point to the idea that KCQs are in fact declarative sentences.

However, I claim that KCQs are not only declaratives sentences but also questions, in the sense that they perform an inquisitive speech act.Footnote 20 First, the speaker that utters a KCQ expects an answer. When the speaker is not sure that the addressee knows the sentence content, the addressee’s answer is necessary, the conversation does not continue until the issue is resolved.

A second argument is that the most accurate way to paraphrase a KCQ is through an interrogative sentence involving a verb like know or remember and an assertive embedded clause marked by the complementizer -ela. Thus, Example (23) is the most accurate way to paraphrase Example (18), that is, Jon etorri da ba? ‘[Do you know this?:] Jon has come.’

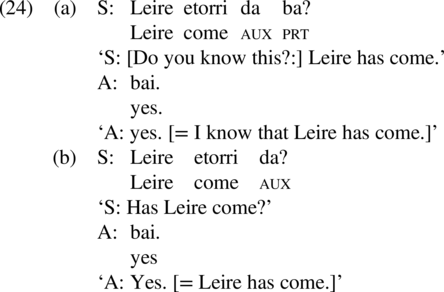

In conclusion, KCQs are questioning speech acts, but what exactly do KCQs ask about? The best way to check it is to look at the answers. In Example (24), I compare the meaning of answering yes to a KCQ and the meaning of answering yes to a regular interrogative sentence.

Moreover, answering a KCQ to decide on its polarity is ruled out, as Example (25) shows.

A canonical yes-no question like in Example (24b) denotes a set of two propositions, namely, the sentence content (‘Leire has come.’) and its negation (‘Leire has not come.’) (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1977, Groenendijk & Stokhof Reference Groenendijk and Stokhof1984). Answering yes to such a question means picking up the proposition with the positive polarity between the two alternatives (Holmberg Reference Holmberg2015). In contrast, answering a KCQ does not mean choosing between the positive or the negative alternative of the sentence content but to decide whether the person providing a response knows the sentence content or not. In other words, answering yes means to accept that the sentence content is in the answerer’s DS. Consequently, KCQs are questions on whether the sentence content is in the addressee’s DS.

Thus, I conclude that, in uttering a KCQ, the speaker commits to the sentence content and (s)he asks whether the sentence content is in the addressee’s DS. Example (26) shows this in a formal fashion, based on the KCQ in Example (24a).

The contribution of KCQs should not be confused with that of tag questions.Footnote 21 Tag questions involve ‘a tentative speaker commitment to the anchor proposition’ (Malamud & Stephenson Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014: 289). Tag questions do not express direct speaker commitment but indicate that ‘if p is confirmed she will share responsibility for it’ (Malamud & Stephenson Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014: 291). Therefore, Malamud & Stephenson (Reference Malamud and Stephenson2014) propose that in tag questions, p does not add to DC A but to the projected DC A. Regarding KCQs, the speaker expresses an independent and direct commitment to p, contrary to tag questions. Speaker’s commitment to p does not depend on the addressee’s confirmation, and the speaker presents p as an undeniable fact. Besides, the speaker asks the addressee whether p is already in DS A. Although both structures may seem alike at first sight, they differ substantially when analysed more closely.

Similarly, KCQ ba may also seem to convey a similar meaning as the English final discourse marker you know? at first sight. However, closer investigation does not support this identification. Östman (Reference Östman1981: 23) identifies the meaning of you know? with ‘do you agree?’ or ‘do you see what I mean?’, and claims that you know? conveys uncertainty on the part of the speaker. However, I have already argued in Subsections 3.3 and 4.1 that KCQs convey speaker certainty. Moreover, ba acts in speech participants’ DS, rather than in the agreement dimension, as you know? does. Therefore, I do not think that KCQ ba can be translatable as English you know?.Footnote 22

In the next subsection, I will propose a syntactic analysis for KCQ in which the relation between the declarative clause type, the questioning speech act and the particle ba gives as a result the meaning of KCQs as characterised in this subsection, and raises interesting theoretical issues on the behaviour of particles and the syntactic characterisation of the speech act.

4.2. The syntax of KCQs

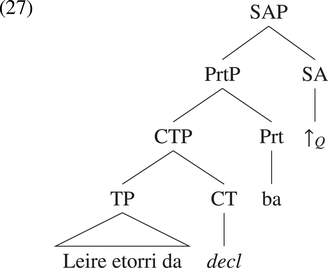

I propose that the final surface meaning of KCQs is the result of syntax. Example (27) illustrates my proposal, based on the KCQ in Example (24a)

In the structure in Example (27), the particle ba is sandwiched between the SA projection and the clause type phrase. The clause type projection types the clause as declarative, expressing the speaker’s commitment to p. Ba merges above CTP and, as final ba in imperatives and declaratives commented in Subsection 3.2, presents the sentence content as known information.

Finally, I propose that the ‘rising’ intonation contour that characterises KCQs has two effects on the utterance. First, it produces an origo or context shift upon the particle ba. In Example (17), I have formalised ba’s meaning contribution, claiming that it marks that the proposition was already in the speaker’s DS before the utterance time. The questioning speech act alters the speaker reference of the particle and transfers it to the addressee. In other words, ba no longer refers to the speaker’s DS but to the addressee’s. Secondly, the intonation produces a questioning speech act. Crucially, the questioning speech act does not affect the sentence content but the particle ba. Consequently, the question is not on the polarity of the sentence content but on the value of the particle, that is, ‘is p in your doxastic state?’.

This proposal makes a contribution to the syntactic representation of discourse and raises some interesting issues regarding the nature of clause types, particles and speech acts. In what follows, I will comment on the theoretical implications of this analysis.

4.2.1. The syntactisation of discourse

My proposal for the analysis of KCQs in Example (27) goes along similar lines to different works on the syntactic analysis of discourse of different traditions. The Split Force proposal by Coniglio & Zegrean (Reference Coniglio, Zegrean, Aelbrecht, Haegeman and Nye2012) divides the original Rizzi’s (Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997) ForceP into a phrase dedicated to clause typing and a phrase that encodes speech act. KCQs show that the discursive syntactic layer must be further split. Ba does not mark the clause type, nor the speech act, but it specifies the commitment expressed by the declarative clause type as being previously known. Thus, we need at least one other phrase where such meaning is encoded. This analysis fits with Paul (Reference Paul2014) and Paul & Pan (Reference Paul, Pan, Bayer and Volker2017), who distinguish ForceP (which marks clause type) from AttitudeP for Mandarin, where particles like ba could be accommodated.

KCQs also show the need for a speech act projection.Footnote 23 Several works have pointed out this need. Haegeman (Reference Haegeman2014), Wiltschko & Heim (Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenbock, Keizer and Lohmann2016), Corr (Reference Corr2016), Heim & Wiltschko (Reference Heim and Wiltschko2020a, Reference Heim, Wiltschko, Kentner and Kremersb), Wiltschko & Heim (Reference Wiltschko, Heim and Achiri-Taboh2020) and Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021) have proposed a bipartite structure for the speech act domain. Despite small differences in the precise characterisation of each phrase, all three coincide that the lower phrase is more ‘attitudinal’ (Haegeman Reference Haegeman2014: 135), whereas the higher phrase is more ‘dynamic’ and encodes the what the speaker wants the addressee to do with the utterance, that is, ‘call on addressee’ (Beyssade & Marandin Reference Beyssade, Marandin, Bonami and Hofherr2006, Wiltschko & Heim Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenbock, Keizer and Lohmann2016). Wiltschko & Heim (Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenbock, Keizer and Lohmann2016, Reference Wiltschko, Heim and Achiri-Taboh2020), Heim & Wiltschko (Reference Heim and Wiltschko2020a, Reference Heim, Wiltschko, Kentner and Kremersb) and Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021) have specified the function of each layer of the speech act structure in greater detail. The higher layer, ResponseP, would regulate engagement, whereas the lower layer, GroundP, would be responsible for regulating commitment. Labels aside, the spirit of these works is consistent with my analysis of KCQs in Example (27): the SAP can be identified with the ResponseP of Wiltschko & Heim (Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenbock, Keizer and Lohmann2016), Heim & Wiltschko (Reference Heim and Wiltschko2020a, Reference Heim, Wiltschko, Kentner and Kremersb), Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021), since the intonation seeks addressee’s engagement, as an answer is expected from the addressee. Similarly, ba fits in their GroundP, as it manages the grounding process of the utterance, relating it to addressee’s Doxastic State.

Besides, KCQs go some way to supporting the idea of separating that speech act domain from the clause typing phrase, where declarative clause type is encoded in KCQs. Some proposals (e.g. Wiltschko & Heim (Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenbock, Keizer and Lohmann2016), Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021)) do not specify where clause typing of the clause occurs. On the contrary, KCQs show that we need at least a tripartite speech act domain: a lower phrase for clause typing, an intermediate projection for epistemic, attitudinal and discourse-related grammatical elements and a higher phrase for grammatical means that encode speech act, such as intonation.

4.2.2. Particles and operators

When analysing discourse particles, many scholars claim that particles have sentential scope (Potts Reference Potts2005) and that they cannot fall under the scope of any operator. Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015: 252) claims that particles cannot be questioned, and links this property to their scopelessness. In contrast, KCQs demonstrate that at least some particles may be questioned. Ba in imperatives and regular declaratives means that the speaker conveys that the sentence content was old information for him/her, whereas in KCQs, the speaker asks the addressee whether the sentence content is old information for them. This is clearly an instance of a questioned discourse particle: the meaning content of the particle ba is on the conversational table in KCQs.

In this regard, there is an interesting contrast between KCQs and al questions with ba. In the case of the former, the meaning contribution of the particle is questioned, whereas in the case of the latter, the questioned element is the sentence content, and the particle ba remains scopeless, as expected with a discourse particle. This may be linked to the syntactic nature of the question. KCQs are in fact declarative sentences with an inquisitive speech act. As shown in Example (27), SAP merges above ba, which allows SA to scope over the particle. On the contrary, al questions with ba are interrogative sentences, and its inquisitivity seems to be derived from CT0 rather than from SA0. Since the interrogative clause type merges below ba, it is clear that ba is not questioned in interrogative sentences.

In other words, the semantic arguments offered by Gutzmann (Reference Gutzmann2015: 250–252) do not explain KCQs, and our data suggest that syntactic reasons may be behind the alleged impossibility of falling under the scope of sentence operators of discourse particles. In any case, this is only an exploring hypothesis. Further research is needed in order to accept or rule out this possibility, which goes beyond the scope of this paper.

4.2.3. Context shift and discourse particles

Some expressions (pronouns, evidentials, locative adverbs a.o.) receive a noncanonical referent in different contexts, for example, modification, conditionals, attitude contexts or questions (McCready Reference McCready2007, Bylinina et al. Reference Bylinina, McCready and Yasutada2014). In principle, discourse particles are not in this list. This is linked to the point addressed in the previous subsection: if discourse particles do not fall under the scope of any sentential operator and they cannot be semantically embedded, they should not undergo context shift, since the element that would cause the shift could not affect the particle. Again, KCQs show not only that at least some discourse particles as ba may fall under sentential speech act operators like questioning but also that a sentential operator may cause context shift on a discourse particle.

In Subsection 3.3, I have shown that final ba expresses that the sentence content was in speaker’s DS before the utterance time. In KCQs, however, ba refers to addressee’s DS. I consider that this change in the direction of the contribution of the particle from speaker to addressee is caused by the questioning speech act. When ba is in declarative sentences, it refers to the speaker’s DS, whereas when it is questioned, that is, in KCQs, it refers to the addressee. Following Lam (Reference Lam2014) and Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021), we could propose that ba merges in different positions (e.g. GroundP

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{Sp}} $

and GroundP

$ {}_{\mathrm{Sp}} $

and GroundP

![]() $ {}_{\mathrm{Add}} $

, in line with Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021)), depending on whether it takes the speaker or the addressee as its referent. However, such an approach does not explain why the same element should merge in different positions, nor what causes this change of perspective. I rather defend that it is not accidental that context shift occurs when it is precisely the particle that is questioned, rather than the sentence content. Interrogative sentences with ba do not show context shift, but in those cases, the questioned element is the proposition, not ba. Thus, I explain ba‘s context shift as a consequence of ba’s meaning contribution being questioned.

$ {}_{\mathrm{Add}} $

, in line with Wiltschko (Reference Wiltschko2021)), depending on whether it takes the speaker or the addressee as its referent. However, such an approach does not explain why the same element should merge in different positions, nor what causes this change of perspective. I rather defend that it is not accidental that context shift occurs when it is precisely the particle that is questioned, rather than the sentence content. Interrogative sentences with ba do not show context shift, but in those cases, the questioned element is the proposition, not ba. Thus, I explain ba‘s context shift as a consequence of ba’s meaning contribution being questioned.

Context shift has been reported for elements such as evidentials. For instance, Quechua has a system of three evidential clitics, which are anchored to the speaker in regular declarative sentences. However, in questions, the direct evidential -mi and the reportative -si ‘can either be anchored to the speaker or to the addressee’ and the conjectural -cha ‘is always anchored to the person who provides the answer’ (Faller Reference Faller2002: 230). This shows that evidentials are sensitive to context shift caused by questions. In the case of discourse particles, Döring (Reference Döring, Gutzmann and Gärtner2011) explores the effect of shifting contexts in the German particles ja, doch and wohl. She demonstrates that the only particle that is grammatical in questions, that is, wohl, suffers context shift and expresses addressee’s uncertainty towards the sentence content.

These examples raise the question whether context shift is possible in nontruth-conditional elements like discourse particles. KCQs are a further argument that they are. Moreover, they constitute an interesting case of study in this respect, as in KCQs context shift only happens when the questioning speech act affects the discourse particle.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, I have presented KCQs, a type of noncanonical question in Basque I consider to be worthy of more research given that it has previously been discussed very little. Throughout the paper, I have shown that KCQs constitute an interesting example to analyse the interaction between intonation and syntax in discourse.

The characteristic pragmatic import of KCQs, which can be paraphrased as ‘Do you know that p?’, derives from the interaction between three elements: clause type, intonation and the discourse particle p. KCQs are formally declarative sentences with the discourse particle ba, which regulates the participants’ DS. The characteristic intonation of KCQs conveys, as a result, an inquiry into the meaning contribution of the discourse particle.

KCQs represent an interesting case study, as they raise some interesting questions on the synctatisation of discourse and the properties of discourse particles. First, KCQs reinforce current theories of the syntax of discourse as a bi-layered syntactic domain (a.o. Haegeman Reference Haegeman2014, Wiltschko & Heim Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenbock, Keizer and Lohmann2016, Corr Reference Corr2016, Heim & Wiltschko Reference Heim and Wiltschko2020a, Reference Heim, Wiltschko, Kentner and Kremersb, Wiltschko Reference Wiltschko2021),Footnote 24 in addition to a dedicated phrase for clause typing (Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997, Coniglio & Zegrean Reference Coniglio, Zegrean, Aelbrecht, Haegeman and Nye2012). Second, KCQs are examples of a dissociation between clause type and speech act, and that the latter may be expressed by intonation (Gunlogson Reference Gunlogson2008). Third, they contradict the assumption that discourse particles cannot fall under the scope of sentential operators (Potts Reference Potts2005, Gutzmann Reference Gutzmann2015), and that they cannot suffer context shift, in line with evidentials (a.o. Faller Reference Faller2002) or some German modal particles (Döring Reference Döring, Gutzmann and Gärtner2011).