Introduction

News media companies have long tried to grow by entering new markets, primarily within their home countries and by acquiring other established newspapers. Although many large national newspaper groups have the capacity to expand internationally, successful examples of internationalization are rare in the newspaper industry. News Corp and A&N International Media are notable exceptions, but they have primarily grown by acquiring existing newspapers.Footnote 1

Companies operating in large language groups have also expanded internationally by publishing their papers in local editions, sometimes with content adaptation and sometimes without. Through this process, some newspapers, mainly from the English-speaking world, have become international. These include the British Financial Times and the American International Herald Tribune. Footnote 2 In these cases, the business model remained the same as when the newspapers were operating only in their home countries. However, this internationalization model is difficult to copy for companies in countries that do not share a common language.Footnote 3

During the 1990s, three major Scandinavian newspaper groups—the Norwegian Schibsted Group (its newspaper division), the Swedish Bonnier Group (its financial newspaper Dagens Industri [Daily Industry]), and the Swedish Stenbeck/Kinnevik Group (its newspaper Metro)—internationalized.Footnote 4 While Schibsted primarily used the acquisition model, Bonnier’s and Kinnevik’s novel business models shaped the internationalization of Dagens Industri and Metro. What makes the internationalization processes of these three cases interesting for research are that they used different internationalization models based on three different business models; they did this during the same period; they were acting in the same institutional environment; they were exposed to the same opportunities by the opening of the Eastern European markets; and they belonged to a smaller language area. This last point means that the possibility to copy, for example, the internationalization model of UK’s Financial Times was closed to these companies. The Bonnier’s Dagens Industri, along with News Corp’s Wall Street Journal and Pearson’s Financial Times, is also a rare example of a successful international financial newspaper.Footnote 5

Both Metro and Dagens Industri later abandoned most of their foreign projects after significant losses. In both cases, however, the companies initially did well, and several other companies copied their business models. Bonnier Group’s business model for Dagens Industri, where technical production was outsourced, is now dominant in the newspaper industry.Footnote 6 The model used to spread Metro—ad-financed newspapers distributed free of charge in public transit systems—was also extensively copied. However, the internet has dramatically changed the conditions of business and distribution models. As Lanzolla and Giudici pointed out, different skills are required to operate digital and print media platforms.Footnote 7 The Metro papers did not manage this transition and went bankrupt in 2020.

Foreign direct investment was possible in the Scandinavian media industry before the 1990s. Nevertheless, the opening of the markets in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union gave the industry a new dynamic. This article focuses on this dynamic and the models used by the three aforementioned Scandinavian newspaper companies to enter the new markets.Footnote 8

Two of the groups, Bonnier and Schibsted, are long-established media conglomerates. The third, Kinnevik, was a late challenger in the Scandinavian media market.Footnote 9 These three companies differ in size and degrees of autonomy. Dagens Industri is a subsidiary of the Bonnier Group, while Metro International (Publishing the international Metro papers) was a listed company (from 1999), albeit one in which the Kinnevik Group held a majority position.

Although these internationalization models have been subject to previous research and are fairly well known, they have yet to be studied in depth for comparison or why the companies chose these models.Footnote 10

The research questions are as follows: What models did these major Scandinavian newspaper companies use when they first ventured into new markets? What may explain the choice of models used? What were the outcomes of these ventures?

The period covered in this article is 1989 to 2002.Footnote 11 In this case, the first steps toward internationalization are considered the most important. In this article, we analyze how the development the companies pursued during the early stages of internationalization significantly impacted their subsequent actions.Footnote 12 We particularly focus on the five years following the first of their international ventures. In the case of Bonnier/Dagens Industri, the period of interest is 1989 to 1994; for both Kinnevik/Metro and Schibsted, it is 1997 to 2002.Footnote 13 Events outside of these periods are included only when necessary for the analysis.Footnote 14

The article is organized as follows: First is a section on previous research, methods, and delimitations, which is followed by a two-part empirical investigation. The first part describes the early phases and model of each media company’s internationalization.Footnote 15 The second part compares the three companies according to a number of relevant criteria applied to the companies’ internationalization model and relating them to theories of internationalization. We also analyze the role of locally formed entrepreneurial teams in internationalization models. The final section offers conclusions.

Previous Research, Methods, and Delimitations

This article links empirically to business history research on media companies, including the three studied here.Footnote 16 However, in previous research on those, internationalization issues are only briefly touched on. Other historical examples available cover the United States, Canada, Australia, Poland, and Singapore and are theoretically linked, in most cases, to the literature on internationalization and entry modes.Footnote 17

Welch and Paavilainen-Mäntymäki identified two main approaches in internationalization research: variance and process.Footnote 18 Variance is concerned with finding explanations “in terms of relationships among dependent and independent variables (thus being positivistic).” Process seeks explanations from observed “patterns in events, activities, and choices over time,” resulting from human behaviors and decision making.Footnote 19 The second approach is also known as a progressive model of internationalization.Footnote 20 This emphasizes, among other things, stages (that is, incremental steps) of cultural or “psychic” distance in the internationalization process and in learning over time.Footnote 21 McAuley notes that the time dimension of internationalization has been neglected in much research.Footnote 22 This article’s research questions correspond to the specifications proposed by Paavilainen-Mäntymäki for studying internationalization over time as a process.Footnote 23 We use a comparative case study method to examine our three cases of internationalization.Footnote 24 Using a theoretical basis, we compare the strategies identified by the case studies with those previously described in the literature.Footnote 25 We analyze the level at which internationalization decisions were made, meaning that we study Dagens Industri rather than the entire Bonnier conglomerate and Metro rather than Kinnevik.

There is also much research concerning the different internationalization models. A basic model is direct exporting, either using own staff,Footnote 26 a subsidiary,Footnote 27 or foreign agents or distributors.Footnote 28 Direct exporting or establishing a subsidiary usually offers more control and is less risky but also more costly than using foreign agents or distributors. The possibilities for using the direct export model have exploded with digital developmentFootnote 29 and improved opportunities to become a “born global.”Footnote 30 However, neither of these options play a significant role in our case studies.

Another internationalization model is licensing, whereby the company provides a foreign company with the technologies or know-how in exchange for, for example, fees or royalties. A third model is franchising, whereby a number of products or services are provided, including the use of one’s brand. Both these models usually require rather limited resources but also result in less control over their own exports.Footnote 31

A joint venture model may require as many resources as direct exports. A contractual joint venture is where two or more companies engage in a partnership sharing the costs, the risks, and the profits.Footnote 32 An equity joint venture is where at least two companies form and invest in a new company, which they each own a part of.Footnote 33 A direct investment model usually requires the most resources but, on the other hand, results in a high degree of control either by acquiring another company or a share in it.Footnote 34 There is less control, of course, if only acquiring a share in another company, but then the risks are also shared. One advantage of both joint ventures and acquisitions with local partners is acquiring local knowledge and networks.

Our analysis focuses on five factors in the internationalization models used in our case studies. Four of these factors have previously been found in earlier research to be important in making internationalization decisions or in outcomes of internationalization. We had mixed findings that differ among our three case studies: (1) the degree of centralization within the newspaper, focusing on shared or independent corporate cultures;Footnote 35 (2) the different levels of control;Footnote 36 (3) the possible synergies within the internationalization of newspaper (found to have positive or negative consequences);Footnote 37 and (4) the importance of local entrepreneurs.Footnote 38 We also identify differences in the areas where the media groups maximized revenue and the possibilities for local expansion after entry. We here base our analysis on product lifecycle theory, which suggests that early in a product’s lifecycle, all resources used to produce the product will come from the area where it has been invented.Footnote 39 The extent to which this applies differs in our three cases.

It should be mentioned that neither the internationalization models used for Metro and Dagens Industri, nor the phases of their decline, have been the subject of business history research (although they were mentioned in Wadbring, in Risberg and Ainamo, and in Lakomaa).Footnote 40 However, Metro newspapers as a business case has been studied extensively, albeit rarely by historians.Footnote 41 Our study also connects to previous research on how companies have worked with self-formed entrepreneurial teams.Footnote 42

There is, as mentioned, extensive research on internationalization and entry models. Nevertheless, there are few studies on media companies, especially those that have entered markets outside of a company’s language area.Footnote 43 Historical examples have touched on the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, and Singapore, but these studies have been exclusively about traditional acquisitions.Footnote 44 The models used to internationalize Dagens Industri and Metro newspapers for market entry, later widely used, were pioneered by Swedish companies. This could be a result of the companies’ limited domestic market and the limited spread of the Swedish language. Therefore, a newspaper company that wanted to expand other than by acquiring established companies had to find a new entry model. It is thus valuable to examine both of these factors. We use Schibsted because the traditional acquisition model works inside and outside of a company’s language area.

Newspaper companies differ from other companies regarding internationalization and entry mode, which is another reason this topic should be studied. The products of newspaper companies can rarely be transported because of the time it takes and are usually consumed in the local language.Footnote 45 These constrains also distinguishes newspapers from magazines, which do not have the same requirements for direct distribution and can be read in a language other than readers’ mother tongue.Footnote 46 Daily newspapers must, in principle, be produced in proximity to the time and place of consumption, which requires local production. That Dagens Industri, at the foundation of the paper in 1976, had chosen to outsource production affected how it later chose to internationalize.Footnote 47

Three Scandinavian Cases

Dagens Industri

Dagens Industri is a financial newspaper published by the Bonnier Group, a Swedish publishing and media company. The paper was founded in Sweden in 1976 and became the most profitable publication in the Bonnier Group in the early 1980s. When Dagens Industri was founded, its business model radically differed from that of existing newspapers. Instead of running composition and printing in-house, Bonnier outsourced these tasks. This offered reduced costs, advantages of new technology, and removal from the devastating labor conflicts that rocked the Swedish media industry, especially the Bonnier Group, in the late 1970s and early 1980s.Footnote 48

Bonnier became an international company early on. It started its internationalization of the publishing side in the mid-1950s when it began trials with a multimarket and multilanguage lifestyle magazine. This venture failed, and it was more than a decade before the group made another attempt at an international venture. In 1969, Bonnier acquired a minority stake in the Danish financial newspaper Børsen (The Stock Market). It was a small paper with a circulation of only six thousand. Bonnier also tried to acquire existing Scandinavian financial papers, but none of these other deals proved successful. Børsen later became wholly owned by Bonnier.Footnote 49

The Internationalization of Dagens Industri

In 1989 Bonnier’s Dagens Industri was the leading financial newspaper in Sweden, and highly profitable. The group began publishing Dagens Industri in Estonia in 1989, which was the company’s first international venture. In many respects, this was an unusual and unexpected decision, even though international expansion was not an entirely new idea. As early as 1956, senior executives in the Bonnier Group had been discussing the prospects for international ventures with financial papers, although such papers were more like Bonnier’s Swedish financial weekly magazine Veckans Affärer (Business Week) than the daily Dagens Industri. Footnote 50 There were also suggestions that Dagens Industri should enter the American market in the late 1970s, but the idea “never left the discussion phase.”Footnote 51

The choice by Dagens Industri to begin publishing in Estonia was not a strategic decision but was apparently triggered by a vacation trip.Footnote 52 In summer 1989, the Soviet system opened up somewhat, and it was finally possible for foreign pleasure boats to enter Estonian harbors. Hasse Olsson, then the editor-in-chief of Dagens Industri, was one of the private sailors who took the opportunity to enter the previously closed waters. He claimed that this sailing trip formed the foundation for internationalizing Dagens Industri. Footnote 53

The venture also had connections to the Estonian democracy movement. In 1989, Ülo Pärnits was the manager of the Estonian company Mainor. This consultancy firm advised small businesses (that is, companies in the Soviet Union with fewer than four thousand employees) on cost accounting and development work. Pärnits and other managers of Mainor, including Edgar Savisaar (later the first prime minister of independent Estonia), were also active in the independence and democracy movement.

In January 1989, Pärnits visited his friend Tönu Kerstell in Sweden.Footnote 54 During the visit, Pärnits met with Hasse Olsson at Dagens Industri, at which he suggested that, to help the democracy movement, Bonnier should start a business paper in Estonia. “It seemed impossible,” Olsson told him. However, that summer, when Olsson sailed to Tallinn in the Soviet Union, he again met with Pärnits. After some discussion, it was decided that a test issue should be published. This was a step that Olsson could approve without asking the board of directors.Footnote 55 He sent for Kjell Wågberg, then Bonnier’s technical director, who, together with Kerstell, went to Estonia a couple of weeks later. Olsson then hired Kerstell to serve as an adviser and door opener into Estonia.

Wågberg and Kerstell met with Pärnits and with Hallar Lind, an Estonian whom Kerstell had recommended as editor-in-chief for the new venture. Wågberg and Kerstell then scouted Estonia for a printer to manage the paper’s printing. None were to be found. The Estonian printers all used obsolete equipment that could neither print in color nor handle the required newsprint quality. Even if they had found a printer with modern equipment, they still would have faced a supply problem. In the Soviet Union, newsprint was allocated on a yearly basis, and it was virtually impossible to obtain an allocation midyear. Bonnier thus decided to print the Estonian version of Dagens Industri in Sweden and ship it by boat to Tallinn.Footnote 56

When the directors of Dagens Industri asked when the Estonian paper could be launched, Lind, who wanted to beat any potential competitors to the market, answered that he was ready to do so within a month.Footnote 57 Olsson found that somewhat optimistic but permitted Lind to go ahead. Lind and Pärnits then rapidly recruited a four-person editorial staff to design the paper. After a month, the Estonian team was ready. The first issue was printed at STC in Stockholm, the same printing company to which the Swedish version of Dagens Industri was outsourced. The initial run was ten thousand copies. Lind had, however, suggested thirty thousand.Footnote 58

The paper was named Äripääv (Business Day) and was launched on October 6, 1989, a month before the fall of the Berlin Wall. It became an immediate success when the initial run was sold out before noon. When Wågberg asked Lind to check on the paper’s progress, Lind asked for another twenty thousand copies, bringing it up to the thirty thousand he had originally suggested. These were printed and delivered two days later. These also sold out rapidly.

There are several explanations for the success of Äripääv. First, there was a substantial demand for news in Estonia, especially for financial information. Second, everything Western was also in demand. The new newspaper looked different, printed on pink newsprint, and had high-quality printing with images, color, and unique content; in other words, Western-style journalism instead of Soviet-style propaganda. Third, following a market penetration strategy, the paper was priced very low.Footnote 59

After the success of the test issue, the paper was quickly approved by the Dagens Industri board, who decided to publish Äripääv weekly. This weekly schedule, however, took time to achieve. Until January 1990 the paper was published monthly, then biweekly until May 1990, and weekly thereafter. By 1992, the paper increased its publication frequency to three times a week; from 1996, it was published five times weekly. Printing was performed in Sweden until February 1990.

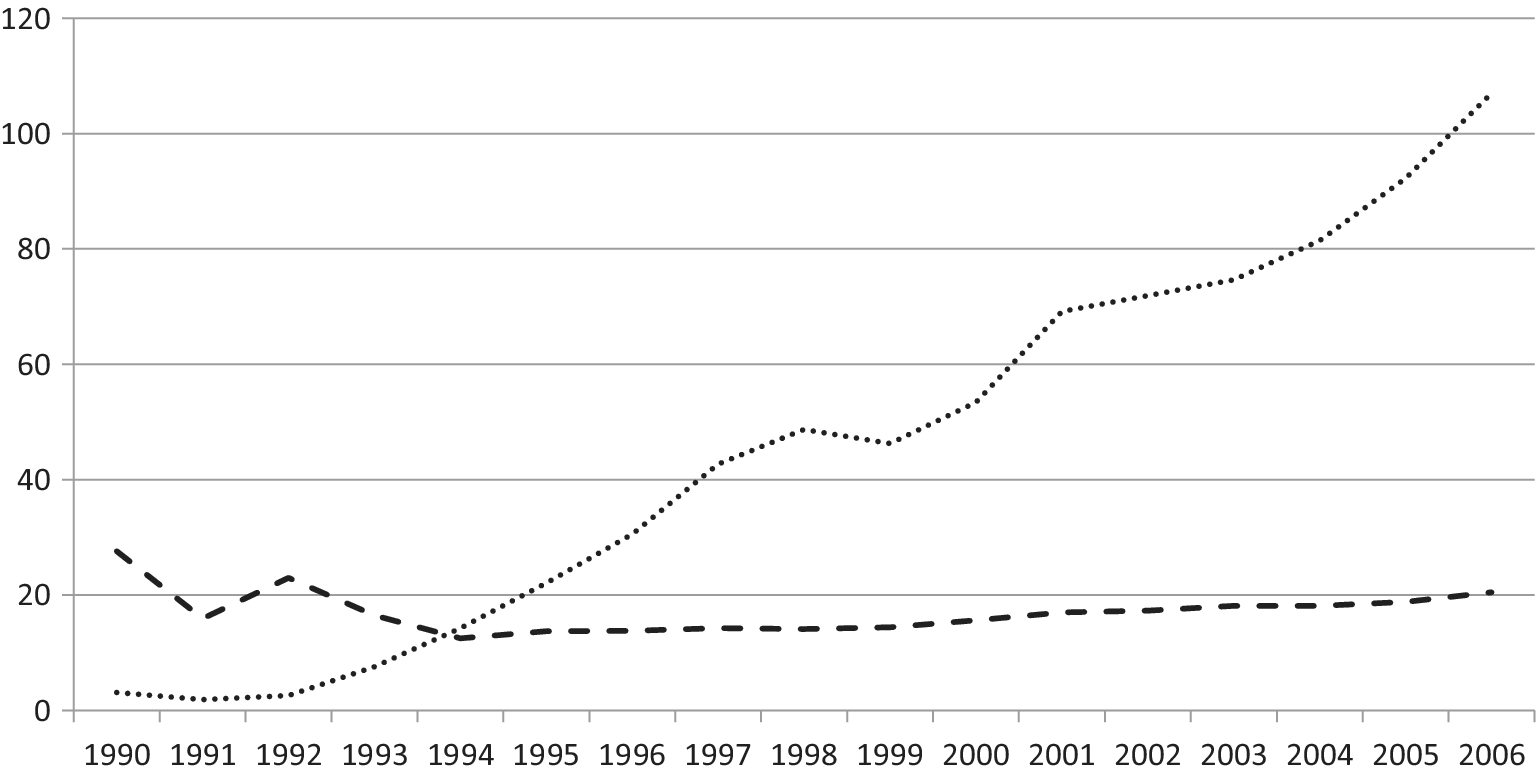

Äripääv only became highly profitable in 1993 (Figure 1). By 2006, the paper had generated net profits of approximately 100 million SEK.Footnote 60 This growth in revenue in Estonia was achieved by both raising the subscription price and increasing advertising content. However, as shown in Figure 1, revenue growth and growth in circulation were not associated. To initially build market share, the paper had a lower price than existing Soviet papers. When the price was increased, Äripääv lost subscribers.

Figure 1. The growth of Äripääv, 2006 prices.

Paid circulation in 1,000s (dashed line) of gross revenue SEK million (dotted line).

The paper rapidly reached a strong position in the Estonian business community and had a market share of close to 100 percent,Footnote 61 mostly due to Estonia being an undeveloped market—the Estonian stock exchange did not open until 1996—and thus lacked any real competition. However, the high market share limited further growth because there was little room for expansion.

Äripääv emulated all relevant aspects of the business model used for Dagens Industri. Printing and typesetting were outsourced locally, which made it possible to use the latest computer technology. The fact that the Bonnier Group hired Estonian subcontractors to do the printing and layout also made it possible for the company to put pressure on them; if a supplier did not deliver the agreed-upon quality and on time, another could be chosen, eliminating the hold-up problem that media companies often faced.Footnote 62

Further Internationalization of Dagens Industri

When Bonnier’s Estonian venture proved successful, management pressed to further exploit the newly opened Eastern and Central European markets. Initially, three countries were considered for the next step in the expansion: Latvia, Hungary, and Russia.Footnote 63 In Hungary, the Bonnier magazine division, Åhlén & Åkerlund, had been printing comic books since 1976.

In 1991, Hungary was chosen as the next market. The new paper, titled Uzlet (Business), was first published in 1991 as a joint venture with a local team of entrepreneurs, but the venture eventually proved unsuccessful. It was discontinued in 1993 after significant losses due to competition from other papers.Footnote 64 In April 1992, Bonnier Group’s internationalization goals continued with the founding of newspapers in Russia and Latvia. Unlike the Hungarian venture, these papers began on a smaller scale, and a lower rate of publication meant lower initial losses. In contrast to when Äripääv was launched in Estonia, modern printing technology was now available locally.

The Latvian Dienas Bizness (Today’s Business), also a joint venture, was profitable within three months but never truly took off. Olsson claims the reason was because it was a small Latvian market with a significant Russian-speaking minority, which Dienas Bizness could not reach. It faced competition from a Russian-language business paper, Biznis i Baltika (Baltic Business), which captured a substantial part of the advertising market. These factors together meant that Dienas Bizness never achieved the circulation needed for high profitability.Footnote 65

While the development in Latvia was slow, it was fast in St. Petersburg. After the fall of communism, St. Petersburg became the center of business life in Russia. In 1992, Bonnier Group started a new Russian paper named Delovoy Peterburg (Petersburg Business). It differed from the previous ventures in that the paper was wholly owned by the Bonnier Group and was not printed locally. Bonnier deemed production in Russia too risky, so the paper was printed in Lappeenranta, Finland, and then trucked to St. Petersburg.

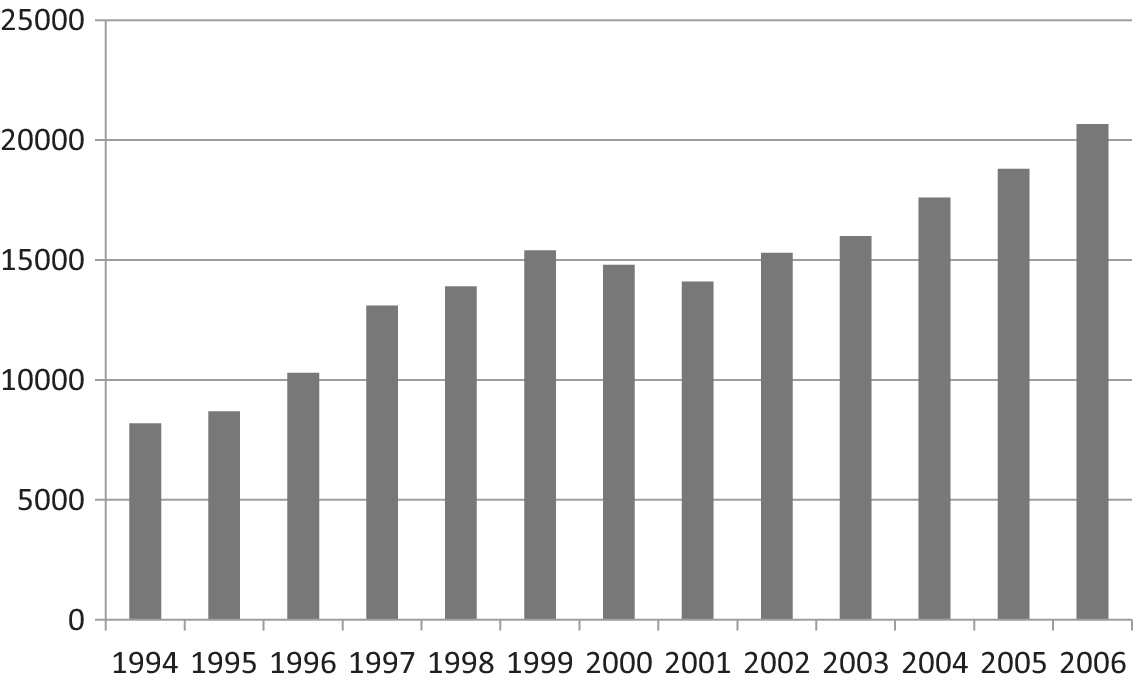

Delovoy Peterburg was an apparent financial success and the only one of Bonnier’s foreign ventures that was profitable from the beginning. From 1994 to 2006, the paper gave the Bonnier Group profits of approximately 50 million SEK.Footnote 66 However, the circulation never exceeded twenty-one thousand copies, and the paper had lower circulation than the Estonian Äripääv almost every year (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Circulation of Delovoy Peterburg, 1994–2006.

Circulation data from Dagens Industri, Bonnier Archive.

Bonnier’s ventures in Russia and Latvia were followed by ventures in Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Austria, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, and Scotland. Most of these were initiated by local entrepreneurs, who approached Bonnier and suggested that a local version of the Dagens Industri could be published.

Even though Dagens Industri was successful in its early internationalization, the company faced some significant setbacks. It pulled out of its Hungarian venture after only two years. In this case, the failure could be attributed to the presence of an established competitor. In Austria, Dagens Industri acquired a 50 percent stake in the local financial paper Wirtschaftsblatt but later sold its shares due to conflicts with the other owners.

Bonnier founded the Scottish paper Business a.m. in 1998, began publication in 1999, and folded in 2002 due to losses of 300 million SEK, three times the total profits of Äripääv, the most profitable of the previous papers. Initially, the idea was that the British Daily Mirror would be a partner in a joint venture project, but Bonnier decided to continue on its own after the Daily Mirror pulled out. A particular concern in Scotland was that the country lacked established subscription systems for newspapers. Instead, most people bought their copies at newsstands or in stores. Thus, Business a.m. not only had to acquire readers and advertisers but also build a system for home delivery and convince the general public of the benefits of having a subscription. A distribution system was created in cooperation with the Royal Mail; however, convincing readers to subscribe was more difficult, so the venture never took off. Circulation stayed at twelve thousand, higher than that of Financial Times in Scotland but a third of the required minimum to break even and far too low to support a staff of 150, including correspondents, advertising salesmen, and marketers. Business a.m. also had a specialized editorial office for the web edition of the paper.Footnote 67

After losing 160 million SEK in the first year (instead of an expected loss of 80 million), Bonnier made attempts to cut costs to break even with a circulation of only twenty-five thousand. This, too, failed, and after losing another 150 million SEK, the company pulled the plug.

The failure of these ventures could be attributed to three factors: (1) there was already an established paper on the market; (2) Dagens Industri used acquisitions to enter the market; and (3) production was started at full scale from the beginning. In Scotland, the absence of an established subscription system also likely contributed to the financial loss. On the other hand, newspapers were successful when Dagens Industri entered markets without competition and chose to publish on a small scale of two or three issues a week.

Was There a Bonnier Advantage?

A newspaper is easily copied, and there is no way to patent or copyright a publishing concept or a paper design.Footnote 68 Dagens Industri might have faced serious local competition if it were only for the paper. A newspaper concept is easy to imitate, and the success of Bonnier must have encouraged prospective competitors. Even so, the company went unchallenged in most cases, and there were few attempts to preempt Bonnier’s entry into new markets. This begs the question: What were Bonnier’s advantages ?

Being a large and foreign media house, the most apparent advantage was that compared to start-ups, Bonnier was at its financial strength. The failures in Austria and Scotland could at least partly be attributed to the presence of other financially strong competitors and, in the latter case, the lack of an established tradition of subscribing to newspapers. Establishing new newspapers is costly, even if they begin on a small scale. The time until profitability is usually measured in years; with Dagens Industri, Bonnier stretched the three-year time frame that Åhlén & Åkerlund used for new ventures in the magazine publishing business to five years. Bonnier assumed it would take ten years to recoup its investments in the new ventures. It was probably difficult to secure bank financing to launch a financial newspaper when profitability was expected only five or ten years later. The ventures were also risky. Due to lower-than-expected profitability, Bonnier pulled out of one-fourth of its ventures.

A second advantage could be that the Bonnier Group had access to internal know-how and could attract external know-how when needed. For example, local entrepreneurs often went to Bonnier with plans for local newspapers; and in some cases the entrepreneurs had already assembled teams of key personnel even before approaching Bonnier.Footnote 69 Part of this advantage seems to be the respected reputation of Dagens Industri and the Bonnier Group.

The entrepreneurs who approached Bonnier had different backgrounds; in Estonia, the local team had connections to the democracy movement; in Lithuania, it was the Swede Carl Berneheim, who then worked for the construction company NCC, who approached Bonnier, and Reuters journalist Rolandas Baristas also joined the team.Footnote 70 In Slovenia, Bonnier was approached by local businessman Slobodan Sibrinic, who contacted both Bonnier and the German Handelsblatt with a proposal for a new financial newspaper to be called Finanza. Sibrinic later led Dagens Industri’s Croatian venture called Business.hr. Footnote 71 In Russia, the venture was initiated by the Swedish advertising entrepreneur Rickard Högberg, who had good connections with leading politicians in St. Petersburg, including its mayor, Anatoly Sobchak.Footnote 72 These connections were essential in the politized business world of Russia. It helped that Högberg had previously worked with the city of St. Petersburg to design an inflight magazine promoting the city.Footnote 73

The third advantage was that Bonnier could use its bargaining power to reduce the cost of supplies. Even if the physical production of the papers was outsourced, the conditions in these new markets were such that, at times, subcontractors could not obtain the needed supplies or were forced to pay inflated prices for them. Bonnier’s Western origins made it possible to overcome some of these supply problems. For example, Wågberg mentions that the company managed to keep the production of Äripääv going by obtaining an export permit for a vital compound for the printing process from Sweden even though it was after office hours, and flying it in via a chartered aircraft.Footnote 74 This advantage is connected to the fourth advantage: the ability to stay out of local power politics. The political situation in Eastern European countries—especially in the early 1990s—was unstable. As a foreign company, Bonnier was less vulnerable to political pressure; the exception was in Russia, where Olsson saw being foreign “as disadvantageous.”Footnote 75 Despite this, the company had its share of incidents, including visits from local mobsters and protracted legal processes involving high-ranking government officials on more than one occasion.Footnote 76

Previous market knowledge must be considered unimportant in this case because Bonnier had been involved in ventures in Eastern Europe before the fall of communism. Despite its local presence, Dagens Industri’s venture in Hungary was the first to fold.

Metro

Metro International, a Swedish print media company, was controlled by Kinnevik and the Stenbeck family. The core product of the company was the free newspaper Metro. The company was founded in 1995 as Metro AB; in 2001, it was listed on the NASDAQ and in Stockholm, first on the alternative SBI list and then on OMX Stockholmsbörsen. Nevertheless, the company went bankrupt in 2020 after a period of prolonged decline.

The newspaper Metro was founded by entrepreneurs Pontus Braunerhielm, Per Andersson, and Monica Lindstedt. Their idea was that because the distribution costs of a paper could be approximated as being equal to the subscription fees, a paper with no (or very low) distribution costs could be profitable without subscribers.Footnote 77 This, of course, was true only if the circulation could be kept large enough by other means. The needed circulation could be met by distributing the paper to mass transit passengers on the Stockholm metro—hence the name, although the paper was later distributed by both delivery men and on mass transit systems other than subways.

The initial funding—50 million SEK—was provided by the Kinnevik Group, led by the entrepreneur and financier Jan Stenbeck.Footnote 78 Equity funding came after banks had declined to fund the undertaking.Footnote 79 The capital requirements were relatively large because the estimated number of readers needed to break even was 200,000.Footnote 80 The Metro’s initial run at launch on February 13, 1995, was 611,000 copies.Footnote 81 The Metro concept was based on papers published five days a week, which was probably necessary to persuade the advertisers and mass transit companies to sign on. Metro assumed it would be difficult to convince advertisers used to buying ad space in established morning or evening papers to switch to a new paper with a novel distribution model and unclear readership. This is why Metro decided to compete on price and target advertisers who were using direct mail.Footnote 82 Metro’s agreement with the mass transit system was equally important. Using mass transit as a distribution channel provided access to a group of readers that the established newspapers had not previously reached, and it reduced distribution costs and restricted competition. Metro was granted an exclusive agreement with the Stockholm Regional Council to distribute the paper in the Stockholm subway in exchange for a fixed fee, profit sharing, a full-page ad in each paper, and no prospective competition, making the venture less risky.Footnote 83 Metro later won tender offers to supply newspapers to the mass transit systems in the Swedish cities of Gothenburg (in 1998) and Malmo (in 1999), securing three local markets free of competition.

From the beginning, Metro was committed to keeping costs low by relying on outside contractors to provide the content and to produce Metro. Compared to other papers, Metro’s staff was minimal, with an average of forty people per edition, including fifteen to twenty journalists.Footnote 84

To achieve this, Metro had to cooperate with news agencies, primarily the Swedish news agency Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå (TT), although TT was owned by a consortium of Swedish newspapers competing with Metro. The people behind Metro were concerned this might derail the venture, but TT had no objections to supplying Metro with content, nor had Metro any trouble with finding outside printers. In this case, a potential competitor, Tidningstryckarna, which Aftonbladet and Svenska Dagbladet owned, won the printing bid. Notably, there was significant overcapacity in the newspaper printing industry at the time.Footnote 85

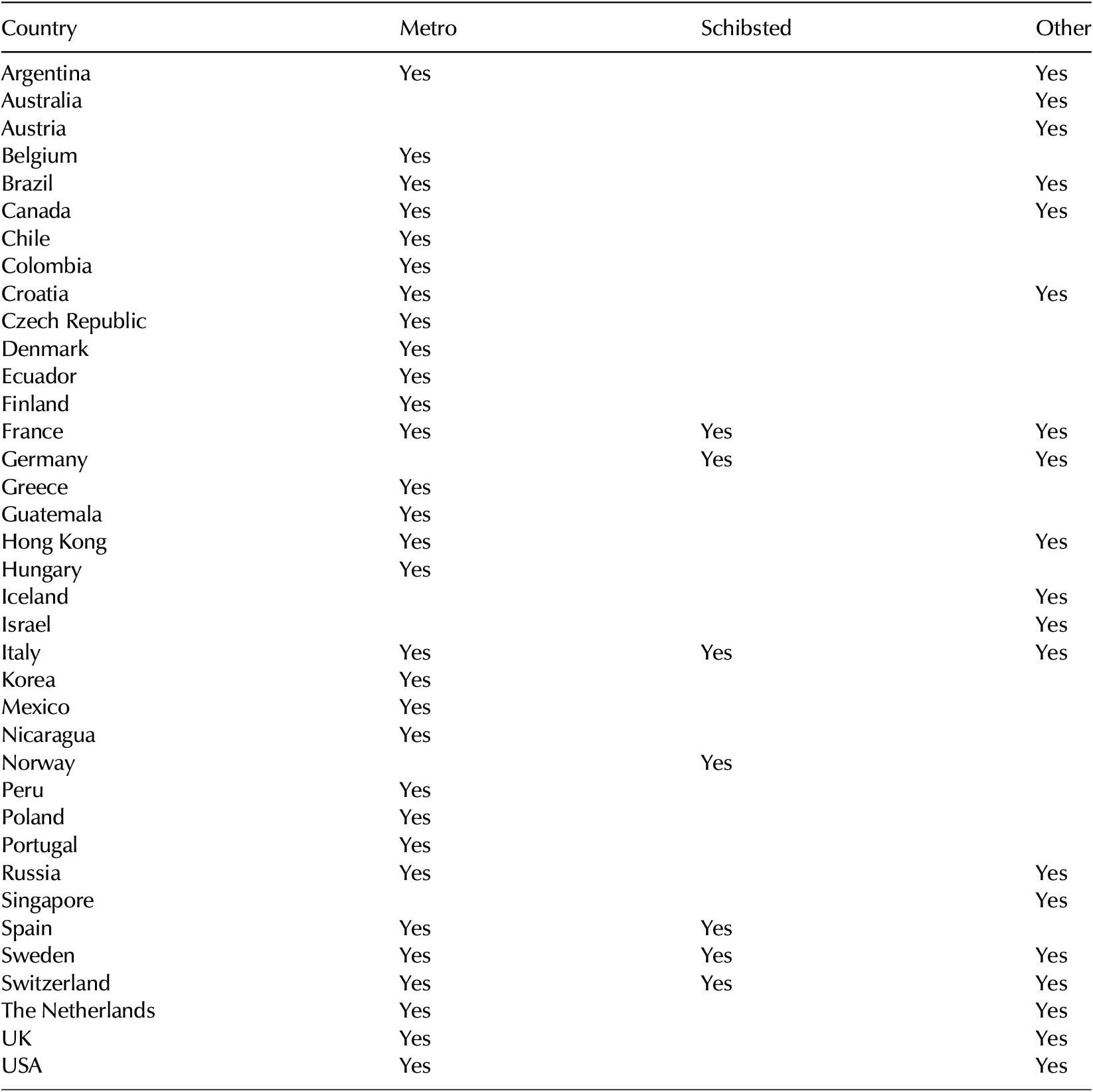

In 1997, before the Stockholm edition was profitable, Metro International began issuing its first international edition of Metro in Prague, Czech Republic. This was followed by editions in Budapest in 1998; in Amsterdam and Helsinki in 1999; in Santiago, Philadelphia, Rome, Toronto, Milan, Warsaw, and Athens in 2000; in Montreal, Barcelona, Boston, Madrid, and Copenhagen in 2001; and in Marseille, Hong Kong, and Lyon in 2002. Not all of these editions were wholly owned by Metro International. For example, the Montreal and Toronto papers were joint ventures, and the Seoul paper was a franchising agreement.Footnote 86 For an overview of the international expansion of free newspapers, see Table 1.

Table 1. Presence of free newspapers, 2001

The key success factor in these cases was finding the right local entrepreneurs. Staff from Stockholm was involved in founding most of the foreign editions, but having local people with the right connections was equally important. Local knowledge was essential because the Metro distribution model depended on reaching agreements with politically controlled mass transit systems.

Metro International’s internationalization model was to quickly build and establish Metro as an accepted advertising channel by keeping costs low, using inexpensive and exclusive distribution channels, and using local competencies (even if centrally controlled). However, as mentioned earlier, unlike other papers, Metro did not have to acquire subscribers. This means that the product was essentially the same from the start, and profitability resulted from growing advertising revenue and potential synergies with existing or future editions being realized. In most cases, Metro International had to pay the same to the mass transit companies regardless of readership, which further emphasized the need for quick advertising growth. For Metro International, growth came first and profitability came later. Initially, it did not need to be profitable but only to show enough potential for profitability, which was used as collateral when the company needed to finance the foundation of additional editions.Footnote 87

Metro International published a set of criteria for where to invest: “All Metro business plans assume the presence of competition. A rigorous set of criteria are applied to potential markets to assess their suitability, including the levels of economic growth, local media spend, and newspaper readership, as well as the structure of the local media industry.”Footnote 88

These criteria, however, imply no de facto limitation on the number of markets that could be entered. In fact, many cities met Metro International’s criteria, making local factors such as having key personnel in place or having local entrepreneurs approach the company with suggestions a driving factor for when and where to invest.

In 1996, before venturing abroad, Metro tried to launch a weekend edition, in an attempt to reach important advertising markets over the weekends, but the project was quickly abandoned due to low profitability.Footnote 89

It took three years, until 1998, for the Stockholm Metro edition to be profitable. In Gothenburg, it took four years, despite Metro having been both granted a monopoly by the municipality of Gothenburg through a tender process and sharing most of its content with Metro Stockholm.Footnote 90

The low profitability of the international editions was a significant problem. Metro International itself said that it was impossible to break even by using hand delivery. When it started publishing a Metro Zurich edition, it was mentioned that hand delivery was ten times as expensive as distribution through bins in the mass transit systems.Footnote 91 Yet hand delivery was the distribution method Metro International used for approximately 50 percent of the company’s local ventures. Wadbring claimed that there is no connection between circulation and the choice of distribution model.Footnote 92 However, it must be argued that there is undoubtedly a connection between the selected distribution model and profitability. Using hand delivery would contradict the basic assumption behind Metro; that is, a free newspaper can be sustainable in the absence of distribution costs.

Although Metro International has not published any figures on local profitability, we can infer from our analysis that the papers not distributed using bins in the mass transit systems were unprofitable; however, a 2001 annual report claimed that almost all editions that survived more than three years were profitable.Footnote 93

The rationale behind internationalizing the Metro was that sharing content would reduce costs across papers. Metro International even started its own news agency to provide Metro papers with content, although in reality, very little was shared. The shared content was, more or less, limited to movie reviews, celebrity interviews, and boxes with funny facts used on the front page. The lack of content sharing made the various Metro papers considerably less profitable than expected.

Another reason for Metro International to internationalize was that Metro could easily be copied or preempted by other companies. For example, Springer soon started advertising-financed free newspapers distributed in mass transit systems: in Germany, as did Kronenzeitung; in Austria, News Corp; in Australia, De Telegraf in the Netherlands; and, later, Daily Mail in the United Kingdom. In Toronto, Zurich, Marseille, and Paris, fierce wars were fought between Metro and established newspapers, some of which were founded as spoilers to ward off Metro. Footnote 94 Only four years after Metro’s first foreign venture, seventy-five similar papers to Metro were launched in twenty-six countries (Table 1).Footnote 95 The editor-in-chief of Metro Stockholm, Sakari Pitkänen, later noted that “an expensive lesson for newspaper publishers around the world is that a free newspaper is truly only a good deal if you are alone in the market.”Footnote 96

Metro International’s contracts with the transit systems and what it paid for distribution were considered trade secrets; and Metro’s annual reports offer few clues about the cost structure of individual papers. However, after Metro International’s 2020 bankruptcy, a 2003 contract between the Stockholm transit company Stockholms Lokaltrafik and the company was disclosed. It shows that the company paid 13.7 million SEK and 10 percent of the profits over 10 million SEK for distribution and the removal of discarded papers; in 2004, the fee increased to 17 million SEK. Stockholms Lokaltrafik had a right to 8 percent of profits up to 10 million SEK, advertising through Kinnevik’s MTG radio network for 1 million SEK, and advertising space in the paper itself.Footnote 97 The contract is complicated and opaque, so it is difficult to precisely assess what the deal was worth for Stockholms Lokaltrafik; additionally, it is impossible to determine what extent the Stockholm contract is representative of contracts with other mass transit operators.

Although its individual newspapers made money, Metro International did not become profitable until 2006, when the group posted a profit of USD13.1 million. However, this was followed by significant losses: USD 27.6 million in 2007, and 20 million euro in 2008.Footnote 98 Pitkänen estimates the total losses at 2,500 million SEK (USD 270 million).Footnote 99 Kinnevik delisted Metro International from the stock market in 2012.

Schibsted

Schibsted is a Norwegian media and publishing company founded in 1839. Among its titles are the largest newspapers in Norway: Verdens Gang and Aftenposten. During the period covered in our analysis, Schibsted was listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange with the Tinius Trust, a foundation created by the family that founded Schibsted, as the largest owner at 26 percent of the votes.

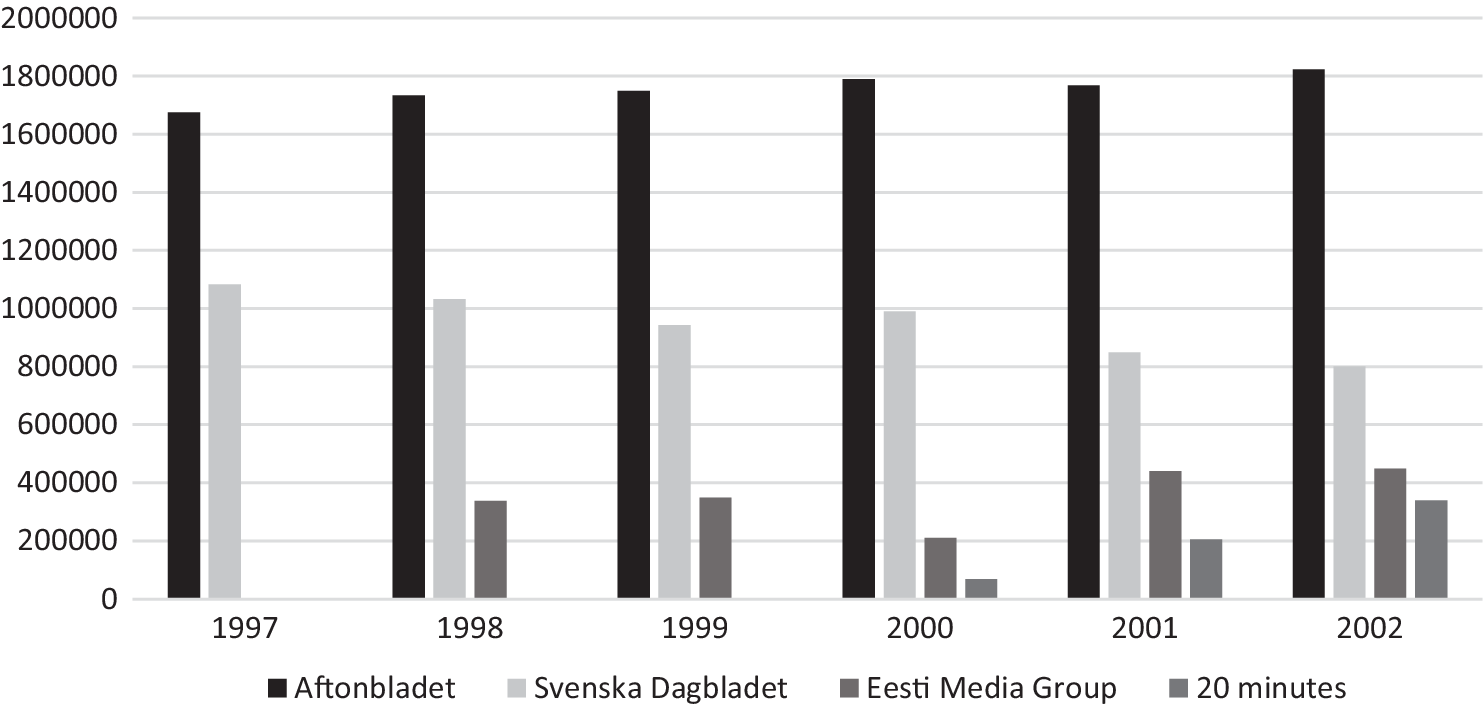

Schibsted began internationalizing its newspaper business in 1997, when it became the majority shareholder in the most prominent Swedish evening tabloid, Aftonbladet. The following year, Schibsted acquired a majority stake in the second-largest morning paper, Svenska Dagbladet. Footnote 100 In 1998, Schibsted moved into the Estonian print media market by acquiring 92 percent of the stock in AS Eesti Media, the largest media company in Estonia. AS Eesti Media owned or had controlling stakes in the two national newspapers, Postimees and Linnaleht, five local newspapers, and nine magazines. There are few similarities among the papers that Schibsted took over. Their first was originally owned by LO (The Swedish Federation of Labour), which wanted to exit the newspaper industry. At the time of acquisition, Aftonbladet had the highest circulation in Sweden and was highly profitable. Schibsted’s second acquisition, Svenska Dagbladet, was a morning paper that struggled financially for decades and faced fierce competition from Bonnier’s morning paper Dagens Nyheter and financial paper Dagens Industri. The owners were a consortium of Swedish companies and a foundation controlled by conservative interests. What Aftonbladet and Svenska Dagbladet had in common, besides their owners wanting to divest from them, was that they shared certain printing facilities.

A unique part of Schibsted’s internationalization process was the development of the free 20 Minutes newspapers.Footnote 101 This was a joint venture that began in 1999 with Swiss investors. Schibsted distributed the free papers in mass transit systems in Cologne (Germany) and in Basel and Zurich (Switzerland).Footnote 102 The Cologne issue was discontinued in 2000, and Schibsted then moved into Madrid and Barcelona (Spain) in 2001 and into Paris (France) in 2002. Also in 1999, Schibsted launched the free newspaper Avis1 in Oslo (Norway).Footnote 103 Schibsted ran the papers as separate entities and intended them to be profitable in their own right.

In most of the acquisitions, Schibsted first gained majority shares of the target companies before acquiring all of the shares of the papers. Schibsted’s internationalization strategy was to focus on a few markets. Even though Schibsted owned and still owns a large number of papers, the markets it serves outside Norway are limited to Sweden, Estonia, France, and Spain (excluding the discontinued papers in Germany and Switzerland). The reason was that the company could cut costs by reducing staff and sharing overhead and facilities costs. Svenska Dagbladet was heavily overstaffed when it was acquired; Schibsted quickly achieved significant savings by reducing the staff from 530 to 270 people over the first five years. Despite their strength, the local unions voiced no strong opposition to the cost-reducing measures, except for some saber-rattling in 2000. Some union officials realized that Schibsted—unlike the former owners—would not support an unprofitable operation indefinitely and that it was in their own best interest to accept the savings program.Footnote 104

Aftonbladet was better managed and profitable, but its staff was also substantially reduced.Footnote 105 Schibsted looked for synergies in all new markets, but was only successful in Sweden. With 20 Minutes, the content was, and still is, shared among the local editions in the same country; for example, among the papers in Zurich and Basel, and the papers in Madrid and Barcelona. There was no exchange of material between the German and Swiss editions, indicating that there may be problems with sharing material across borders, even when there is no language barrier.

The process of finding suitable investments was relatively uncomplicated: Schibsted looked for established media companies or papers where profitability could be increased through savings. The targets were easy to find.Footnote 106

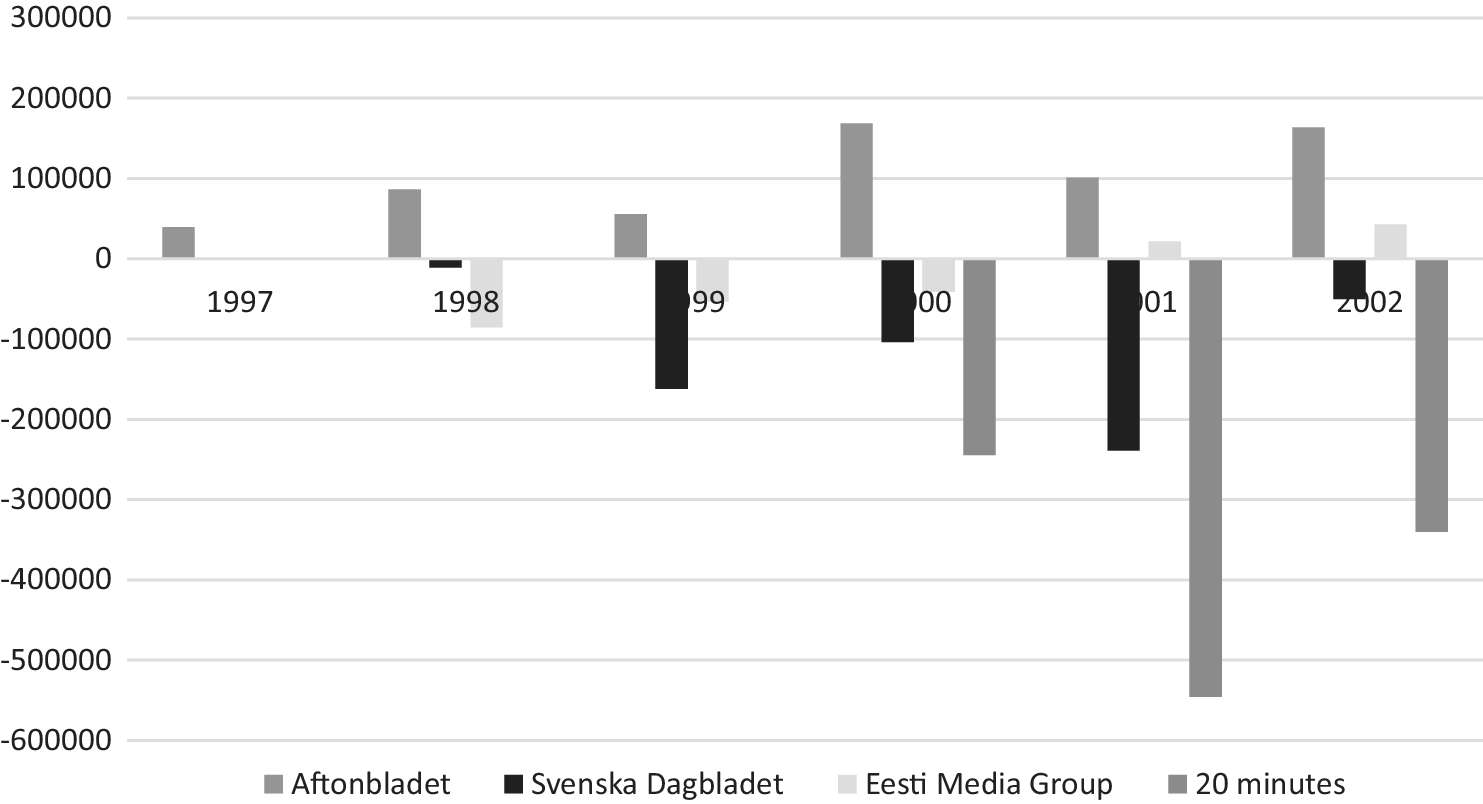

While Aftonbladet was profitable during the first five years of Schibsted’s ownership, and significantly improved both total revenue and operating profit over time, the company’s international profitability in total was negative (Figures 3 and 4). This can be attributed primarily to significant losses by 20 Minutes and Svenska Dagbladet, although the later eventually reduced its losses significantly.Footnote 107

Figure 3. Total revenue for Schibsted’s international newspaper ventures 1997–2002, MNOK (2002 prices).

Source: Schibsted annual reports.

Figure 4. Operating profit/loss for Schibsted’s international newspaper ventures 1997–2002, MNOK (2002 prices).

Source: Schibsted annual reports.

Analysis

In this section, we analyze the three media groups’ business and internationalization models. Bonnier, with its Dagens Industri, and Kinnevik, with its Metro papers, have distinct models, at least under an ex post analysis. Schibsted could be viewed as having two models: acquisitions and, for 20 Minutes, green-field investment and joint ventures. However, for the factors analyzed in this section, the similarities between Schibsted’s acquired papers and the 20 Minutes are so significant that we have treated them together.

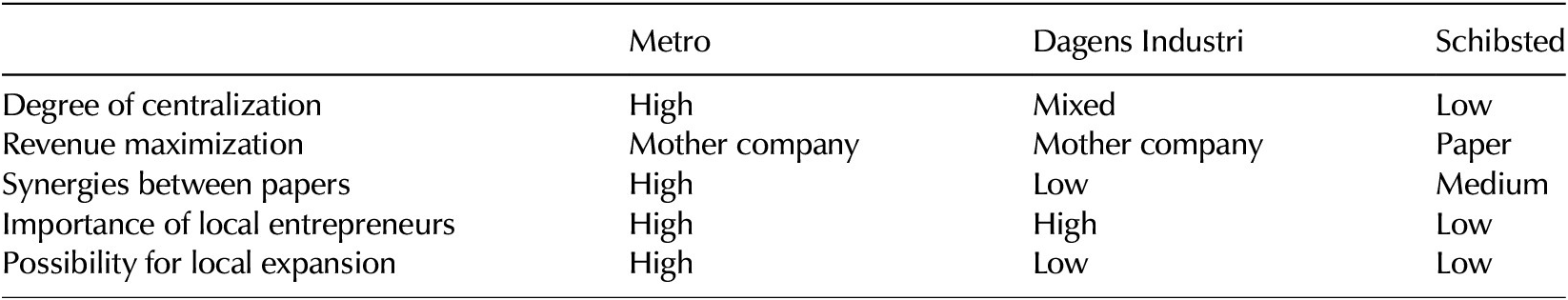

Analyzing the three different groups, we find that they differed in several important ways: regarding the degree of centralization (both in corporate control and corporate culture); the level at which revenue was maximized; possible synergies between local papers; the degree to which companies depended on local entrepreneurs; and possibilities for local expansion. These differences shaped the companies’ respective internationalization models. Some of these differences have already been addressed, albeit indirectly. Here, these previous findings will be put into perspective (Table 2.)

Table 2. Summary of key findings

In this section we also compare the three groups’ choices of market, entry modes, and time to profitability, both with each other and with internationalization theory.

Degree of Centralization

The companies’ choice of business models are a reflection of their degree of centralized control, with Metro International having more centralized control and Schibsted having more autonomy. In the case of Bonnier, the Dagens Industri papers were initially controlled on group level, but it ceded control to the local papers, although Bonnier still monitored them to maximize revenue.

Within Schibsted, the local subsidiaries were given a high degree of autonomy, even sharing overhead. In Estonia, autonomy was achieved through a joint holding company. During the first years following Schibsted’s acquisitions in Sweden, the local papers stayed separate and cooperation was limited. Schibsted’s 20 Minutes business model can be considered a copy of the Metro concept, although it differed regarding corporate control. The 20 Minutes newspapers were initially a Swiss–Norwegian joint venture—with Schibsted later buying out the outside partners—and the papers enjoyed a high degree of independence, reflecting the overall Schibsted model.

In contrast, all local editions of the Metro were managed in the same way. All new subsidiaries founded during the period studied were established directly by or under the guidance of Stockholm staff, although entrepreneurs from the local markets might have influenced Metro International’s decision to launch the subsidiaries.Footnote 108 Metro International produced a handbook that described how to run local papers. While the company posted losses for most years, that did not prevent the Kinnevik Group from successfully floating a substantial portion of the company on the stock market.

The Metro case is similar to Dagens Industri, although not completely. The use of local content gave the papers within the group considerable room to differentiate, such as in style and tone.Footnote 109 Nevertheless, readers could easily recognize the local editions as part of the same group. For example, the graphic design of the papers was standardized, and, in many cases, the future core staff traveled to Sweden to be trained in Western journalism.

The degree of autonomy influences corporate cultures. All Schibsted papers have individual corporate cultures and identities, with the exception of 20 Minutes, which are intended to look the same. The autonomy for papers within the Schibsted Group was also indicated by the fact that the group did not discontinue unprofitable papers but, on the contrary, willingly supported struggling papers for a long time financially.Footnote 110 On the other hand, Metro International worked hard to build a common culture, even when the local papers were run as franchises. Bonnier chose a road somewhere in between. One thing both Bonnier and Metro International had in common was policies of shutting down (or selling off) operations that did not reach their financial targets within a predefined time limit.

Profit Maximization

The cases also differ regarding the companies’ concerns for where profits were to be maximized, which is related to how long local losses were accepted. Metro International and Bonnier wanted to maximize profits at the parent company; Schibsted, in general, wanted to maximize profits locally.

Like most free newspapers, Metro International started its local editions at full scale with high circulation, such as five editions a week. Starting a full-scale edition was probably a requirement of both advertisers and local mass transit companies, which, in most cases, were the distributors. This necessitated an ability to absorb large initial losses, which could be taken more easily by a parent company than a local one, and made time to profit shorter than for a financial newspaper like Dagens Industri. An existing newspaper is running and generating a return on investment (ROI), although it may be negative. After it is acquired, it is expected to continue doing the same. Schibsted either acquired newspapers already yielding a positive ROI (such as Aftonbladet) or saw the potential in turning losses into profits through cost reductions (such as Svenska Dagbladet). One exception was 20 Minutes because it started as a joint venture. This indicates that Schibsted was willing to deviate from its main acquisition strategy when an opportunity appeared.

Synergies

Metro International was a deeply centralized operation with a high potential for synergies among the papers. Its business model allowed both content sharing between editions and more than one edition to be published in a specific country. Conversely, there were few possibilities for synergies among the different editions of Dagens Industri because there was never more than one paper in the same market. Schibsted focused on a few markets and, by the 2010s, controlled more than one dozen papers in Estonia and two each in Sweden, France, and Spain, which allowed for some content sharing, at least in theory. Metro International believed that by sharing content and some overhead, costs could be kept low enough to make the papers profitable without relying on subscription fees. Corporate headquarters closely monitored the local operations in the Metro group with extensive use of financial targeting and reporting. With Metro having the same graphic design for all of its papers and material from the same news agencies, the journalistic content was often the same. The idea was also that non-news agency content (e.g., local and feature articles) would be shared, but this rarely happened. In practice, there was little content sharing that was unplanned, yet there were still synergies in production and advertising sales. This was especially true when multiple papers operated in the same country.

Importance of Local Entrepreneurs

Another differentiating factor between Metro International and Bonnier, on the one hand, and Schibsted, on the other hand, was the importance of local entrepreneurs to the ventures. The former depended on finding the right local entrepreneurs. Even if almost all Metro editions were created by staff from Stockholm, they still needed people with local knowledge to, for example, negotiate agreements with mass transit systems. Without this knowledge, the chance of being profitable was severely limited. In the case of Dagens Industri, the key factor for success was finding good local managers and journalists. As mentioned earlier, in many cases, local entrepreneurs approached them with an already assembled core staff to be hired as a group. Meanwhile, Metro papers had a limited need for journalists because most of the content was bought from news agencies. The entrepreneurs involved in setting up the local Metro and Dagens Industri ventures had mainly economic or political skills rather than journalistic. This may be because local Dagens Industri, Metro, and 20 Minutes papers were already established with their own journalistic styles. In this respect, despite the differences in distribution models, there is less of a difference between these three papers as compared to the papers acquired by Schibsted.

To entice entrepreneurs, media companies had to be established and respected, but that was not enough, at least in the minds of the managers of these companies. To reach potential local entrepreneurs, the managers had Dagens Industri and Metro papers participate in international media conventions.

The media companies’ strategies to search for local opportunities were not new; all industries search for new ideas, products and people.Footnote 111 However, few media companies have been as dependent on search as Bonnier and Metro International, which gave them an advantage over prospective new entrants.

Schibsted’s acquisition model for internationalization was much less dependent on finding new local entrepreneurial teams because the newspapers they acquired already had them in place. These papers were also well known, so the challenge was finding targets at the right price. If Schibsted already had a presence in the country, the number of potential targets were even more limited, as was the need for local expertise. With teams in place, Schibsted made few staffing changes and limited reshuffling to the most senior management positions, and even some of these were left intact.

The case of 20 Minutes was somewhat different. The first 20 Minutes in Zurich was the result of local entrepreneurs approaching Schibsted, with later papers founded by Schibsted staff. For Metro and Dagens Industri papers, having established teams with local knowledge in place was critical for profitability. For example, a Metro was granted monopoly access to distribution in the mass transit systems, and this exclusivity meant profitable operations. It is unlikely that exclusivity agreements would have been granted to those without deep knowledge of local power politics.Footnote 112

Metro International was also known to generously reward individual talent, which might have attracted local entrepreneurs to offer their services instead of trying to start their own papers. It is likely that the location randomness was the result of entrepreneur groups willingness, or not, to help Metro International start local editions. To recruit entrepreneurs, Metro International used various profit-sharing models, such as co-ownership (as in Canada) and franchising (as in Seoul). We must, however, conclude that profit sharing was not a very powerful incentive because many Metro operations were unprofitable. In many cases, the company obviously preferred market share over profitability.Footnote 113

The use of local entrepreneurs likely made it possible for Dagens Industri newspapers to scare off competitors. At the same time, Bonnier must have been aware of the risk of local entrepreneurs approaching potential competitors instead. If any propositions were successful, the market became closed to others. However, this did not occur. One possible explanation is that Bonnier was successful in attracting local entrepreneurs—so successful that editor-in-chief Hasse Olsson claimed that they could not respond to all propositions.Footnote 114 That Bonnier and its Dagens Industri were well-known actors in the media market likely played a role in attracting entrepreneurs with proposals.

For the entrepreneurs, approaching Bonnier with a proposition to start a local Dagens Industri edition was less risky than other options. Bonnier was known to pay high-performing individuals well. Being part of an established and financially strong group made such ventures more likely to succeed, thereby giving the entrepreneurs a higher payoff.Footnote 115 The alternative of starting a newspaper on their own was, in most cases, not an option. Combined, these factors gave Bonnier an advantage over prospective competitors. Its ability to scare off competitors also prevented the paper from being copied.

Helgesen attributed the internationalization model used by Schibsted to the educational background of Schibsted management. Many executives attended the Norwegian Business School, in Bergen, as students in the 1970s,Footnote 116 where they studied and were possibly influenced by contemporary internationalization theories. Some of these theories were used as guides when former business students gained management positions.Footnote 117 However, Helgesen gave no guidance on which models he was referring to, although growth and international expansion via acquisitions were possible models. Nevertheless, the future executives were likely exposed to product lifecycle theory and the internationalization process model by Jan Johanson and Jan-Erik Vahlne, known as the Uppsala model.Footnote 118

Product lifecycle theory suggests that early in a product’s lifecycle, all resources used to produce the product come from the geographical area where it has been invented.Footnote 119 After the product is adopted in other countries, production gradually moves to these areas. In some situations, the product later becomes an import of the country where it was originally invented. The model applies to labor-saving and capital-intensive products demanded by high-income groups. According to the Uppsala model, which is a top-down model, internationalization is a learning process in which international expansion occurs gradually and incrementally and in which market commitment and market knowledge play essential roles. There are no indications that Schibsted tried to influence journalistic principles, or that it tried to teach a new way of working, as Bonnier did with Dagens Industri. Footnote 120 The journalistic operations of the Schibsted papers were run as before, albeit with fewer staff. The acquired papers kept their separate brands and style, and little material is shared.

Possibilities for Local Expansion

The last of our identified differentiating factors between the three companies is the potential for local expansion. This relates to how companies selected their markets and their different views on competition.

Bonnier chose with Dagens Industri a cautious policy in which they carefully examined each market before deciding to enter it, and entered only markets that fulfilled the following two criteria: (1) no competition, and (2) high growth potential (primarily due to catching-up effects following the newly won freedom from communism). Bonnier also implicitly reduced the potential for expansion through its choice of entry criteria.

Dagens Industri limited the number of markets it could enter at a single point in time to one. In addition, they entered new markets only on a small scale,Footnote 121 with issues that published once or twice a week—this success was possible only because competition was absent. Dagens Industri discontinued unprofitable papers after a certain number of years—five, in most cases, but they discontinued others with high losses sooner.

All measures were intended to reduce potential future losses. It takes a long time—approximately five years—for a paper such as Dagens Industri to become profitable and five more until it recoups the initial investment.Footnote 122

This timeline requires the limitation of losses if the venture is to eventually be successful.

Bonnier’s unambiguous criteria for selecting markets clearly signaled to potential competitors which prospective markets it expected to enter its Dagens Industri. Competitors could have, but did not, use this information to preempt these moves, possibly because the company gave no indication in its timing since local entrepreneurs drove the forward momentum. Bonnier first had to be approached by a suitable group of entrepreneurs about Dagens Industri, but then they responded quickly to enter the new market on short notice—but only if market conditions were right. (In other cases, as noted above, Dagens Industri representatives actively looked for such groups.)Footnote 123

Unlike with Dagens Industri, the Metro newspaper concept was widely copied. As noted earlier, only four years after Metro International’s first international venture, there were free daily newspapers distributed in mass transit systems in twenty-six countries.Footnote 124 One reason could be that, unlike financial papers, there is room for more than one free paper in markets, as explained by Metro International itself.Footnote 125 There are many examples of cities with more than one free daily newspaper; Pitkänen notes that in 2006, there were seven free papers in Seoul and four each in Prague, Paris, and London.Footnote 126 However, some markets could not sustain more than one paper, so some newspapers were shut down. This occurred, for example, in Stockholm (Stockholm News, Everyday), Cologne (20 Minuten, Köln Extra, Kölner Morgen), and Buenos Aires (Metro, El Dario del Bolsillo).Footnote 127

Without the restriction of a no-competition criterion, the number of potential markets to start free newspapers is far more open. And because Metro was not a national paper, this circumstance was further accentuated. Whereas e.g., Poland was a potential market for Dagens Industri, Warsaw, Krakow, and Poznan were potential markets for Metro.

In process models of internationalization, firms tend to move gradually into specific foreign markets that are geographically or culturally close to the domestic market and wait to enter more distant markets.Footnote 128 Firms start their foreign operations by exporting products via agents, establishing local subsidiaries, and finally moving to local production. This is consistent with the product lifecycle model, in which all resources used to produce the product initially come from the area where it has been invented.Footnote 129

In our analysis, we found two distinct models. When Bonnier and Schibsted acquired existing papers, they usually followed market entry models compatible with Johanson and Vahlne’s Uppsala model. Both began their internationalization long after they had built successful operations in their home markets, and both entered geographically closer markets before more distant ones. Schibsted used an internationalization model where it could slowly enter markets that were close (geographically or culturally) to its home market and then try to build groups of local papers.Footnote 130 Since the papers were already established when Schibsted entered the new market, the risk was lower than with green-field investments. Schibsted, however, always faced the risk of overpaying, especially when the acquisition targets were well-managed papers.Footnote 131 The Bonnier Group also used the Uppsala model when expanding within Sweden. However, for political reasons related to their dominant positions in their home markets, neither Schibsted nor Bonnier could quickly expand in their own markets. This made internationalization necessary for continued growth, as shown by the Dagens Industri case, where Bonnier first chose markets geographically close to Sweden.

Metro International showed a willingness to enter more than one market simultaneously, and markets that were neither geographically or culturally similar, and it entered new foreign markets long before its previous operations were profitable. Even with the underlying strategy of the Metro group to find synergies between papers, they did not always enter markets close to existing ones, implying that market presence was considered more important than profitability. The same applies to 20 Minutes. Here, however, the company appears to sometimes use entry into markets as only a spoiler; the significant losses for 20 Minutes indicate this might have been an investment strategy to keep out potential competitors.

However, Johanson and Vahlne later expanded their Uppsala model, arguing that (1) firms with abundant resources may take their internationalization to more geographically distant markets because the relative commitments are smaller; (2) markets that are stable or homogeneous allow knowledge to be acquired from sources other than a company’s own previous market experience; and (3) firms with plenty of experience in similar markets can generalize this experience to other specific markets.Footnote 132

Conclusion

By analyzing the internationalization of the three Scandinavian media companies of Bonnier (Dagens Industri) Kinnevik/Metro International (Metro), and Schibsted, we observed multiple models for entering new markets and differences in the markets they entered, although all attracted to the newly opened Eastern European markets. Bonnier and Kinnevik/Metro International exhibited novel internationalization processes as they broke new ground in the media industry: Bonnier did this by outsourcing Dagens Industri´s printing and typesetting and by creating a powerful presence in Eastern Europe; and Kinnevik/Metro International did so by outsourcing the production of Metro content and by creating a distribution model centered on the mass transit systems. Schibsted, on the other hand, took the more traditional route for international expansion and company growth by acquiring already established newspaper companies. Dagens Industri’s and Metro’s novel approaches were easily copied and thus attracted competition, most likely contributing to their newspapers’ later failures. In contrast, Schibsted’s acquisition model meant the company entered markets with already established competition.

To successfully internationalize Dagens Industri and Metro, Bonnier and Kinnevik/Metro International had to attract local entrepreneurs to form the core staff for their new papers. This implies that they used a bottom-up model of internationalization, in which determining the markets to enter—and the timing—were driven by a great extent by where such local entrepreneur groups were found or approached the media companies. It is also worth noting that despite this dependence on local search, there was no explicit strategy behind Bonnier’s model of internationalization for Dagens Industri papers; instead, they relied on both experimentation and management to pursue a business culture that had proven to be successful in the past. Metro International and the Schibsted Group, on the other hand, employed strategy-driven internationalization models for their newspapers. Our comparative study shows that companies selling similar products, facing the same challenges, operating under the same institutional restrictions, and having access to the same markets may act very differently. In all three of our cases, the companies can be viewed as having a historical anchor:Footnote 133 they continued to do what previously worked reasonably well, even while using an explicit strategy. That is, internationalization strategies are not chosen but rather an implementation of national practices in new markets.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ingela Wadbring, Udo Zander, Espen Storli, Hans Sjögren, Håkan Lindgren and participants at the 2020 Economic and Business History Conference and the EHFF seminar for valuable comments and suggestions. Funding has been received from the Ridderstad Family Foundation, the Gunvor and Josef Anér Foundation and the Ollie and Elof Ericsson Foundation.