Introduction

Efforts to reduce biodiversity loss, implement international conventions and meet agreed global conservation targets will require increasing numbers of knowledgeable, skilled, experienced and committed people. Modern conservation is a multidisciplinary occupation, requiring workers who can succeed in complex and shifting work contexts, spanning (inter alia) life, earth and social sciences, agriculture, fisheries, forestry, tourism, recreation, economics, law, criminology, communication, education and human health, and requiring entrepreneurial, leadership and management skills.

To meet this need, there have been calls for conservation to be established as a profession ‘of equal importance to healthcare and the law’ (Dudley & Stolton, Reference Dudley and Stolton2020, p. 171). Mieg (Reference Mieg2009, p. 94) defined professions as ‘relatively autonomous occupational groups that claim jurisdiction over a certain class of tasks’ but there is currently no common understanding of what professionalization means in the context of conservation, what being a conservation professional involves, or the risks and benefits of professionalization.

Professionalization in the context of conservation

We searched, using search engines Google (Google, Mountain View, USA), Ecosia (Ecosia GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and ResearchGate (ResearchGate GmbH, Berlin, Germany), for generic definitions of the terms ‘profession’, ‘professional’ and ‘professionalization’ and for peer-reviewed articles and grey literature using these terms in the field of conservation. From these, we identified eight main attributes of professionalization through an iterative process, including discussions with peers, conference discussions, and a workshop on professionalization in conservation (BfN, 2017). The following sections identify how each attribute could potentially benefit the conservation sector, review progress to date and highlight aspects where generic concepts of professionalization do not readily align with the needs and directions of the emerging conservation profession.

(1) A defined and respected occupation

Established professions (e.g. doctor, lawyer) are generally based around a clearly defined sphere of knowledge and expertise (Saks, Reference Saks2012). Interpretations of the term ‘conservation professional’, however, vary widely. Jeanson et al. (Reference Jeanson, Soroye, Kadykalo, Ward, Paquette and Abrams2020) provided a non-exhaustive list of conservation professionals comprising the scientific community, policymakers and governing bodies, youth educators, resource managers, resource stakeholders, funding agencies and Indigenous knowledge holders. Papworth et al. (Reference Papworth, Thomas and Turvey2019, p. 405) asked ‘Do you consider yourself to work in biodiversity conservation?’ to identify professionals, whereas Lucas et al. (Reference Lucas, Gora and Alonso2017) stipulated possession of a master's degree. Blanchard et al. (Reference Blanchard, Sandbrook, Fisher, Vira, Larsen and Brockington2018) identified conservation professionals as those working for conservation NGOs, distinct from conservation science researchers and social scientists. Francis & Goodman (Reference Francis and Goodman2010) distinguished three main groups in conservation: researchers (mainly academics), professionals in governmental agencies (focusing mainly on decision-making), and those in NGOs focusing mainly on conservation practice.

Respect and trust are attributes widely associated with professionalism (Evetts, Reference Evetts2006), but the respect called for by Dudley & Stolton (Reference Dudley and Stolton2020) will be difficult to achieve without a more consistent understanding of what a conservation professional is, and will remain a challenge so long as conservationists are primarily regarded as activists (Klas et al., Reference Klas, Zinkiewicz, Zhou and Clarke2018), sentimental wildlife lovers or even economic terrorists (Handy, Reference Handy2019). According to Paterson (Reference Paterson2006, p. 149) ‘The concept of the wildlife conservationist is that of a resource manager whose job is to manage natural resources for the benefit of people, but who is fighting an ongoing battle to prove the value of this work.’

(2) Official recognition

Well-established professions are normally officially recognized through inclusion in national registers of occupations and/or through legal restrictions on practising the profession to those with required qualifications and certification, often defined by recognized professional associations. This helps to maintain common, consistent high standards and signals and encourages trust. Conservation, however, is not widely recognized as a distinct profession, or even as an occupation. The International Labour Office's (2008) standard classification of occupations includes Environmental Protection Professionals as a subcategory of Life Science Professions but does not mention conservation. Although some countries, for example Canada, recognize specific conservation occupations, many, such as India, classify conservation work alongside agriculture, forestry, fisheries and hunting.

(3) Knowledge, learning, competences and standards

Brock et al. (Reference Brock, Leblebici and Muzio2014) characterize a profession as a knowledge-intensive occupation, but being a professional should also involve the application of knowledge (Abbott, Reference Abbott1988). Definitions of professions emphasize both the need for specialized education and training and for common standards of competence (e.g. Cambridge University Press, 2020; Corporate Finance Institute, 2020).

The volume of conservation knowledge products is continually increasing in the form of articles, reports, guidelines, books and websites, but much of this material is available only in English. Furthermore, expensive and/or unreliable internet connections may limit access in regions where many conservationists work. Scientific studies and new ideas are still mainly published in peer-reviewed journals that are often difficult to locate, in some cases expensive to access, and written using language and styles not aimed at practitioners, few of whom consult journals (Gossa et al., Reference Gossa, Fisher and Milner-Gulland2015; Giehl et al., Reference Giehl, Moretti, Walsh, Batalha and Cook2017; but see Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Bollmann, Brang, Heiri, Olschewski, Rigling, Stofer and Holderegger2019). These barriers are now being addressed by collating and presenting results and experiences in more accessible, diverse and engaging formats (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Dicks and Sutherland2015; O'Connell & White, Reference O'Connell and White2017; Fabian et al., Reference Fabian, Bollmann, Brang, Heiri, Olschewski, Rigling, Stofer and Holderegger2019; Conservation Evidence, 2021).

Indigenous and local knowledge is increasingly recognized as being as valuable to conservation as expert professional knowledge (Adams & Sandbrook, Reference Adams and Sandbrook2013). But formalizing Indigenous and local knowledge systems into frameworks of professional management can lead to erosion of endemic, place-based Indigenous and local knowledge and management practices (Nadasdy, Reference Nadasdy2003).

Availability of training and learning has also expanded. There has been a proliferation of high-level courses on topics such as conservation leadership (Bruyere et al., Reference Bruyere, Bynum, Copsey, Porzecanski and Sterling2020), and some academic institutions are successfully blending academic and professional/vocational conservation training; e.g. the African Leadership University, the Wildlife Institute of India, CATIE in Costa Rica and Colorado State University in the USA. However, the majority of such programmes are still based in Europe, North America and Australasia, are in English and are unaffordable for many students from tropical countries without scholarship support (Bonine et al., Reference Bonine, Reid and Dalzen2003).

Local or regional training colleges may be more accessible in many countries, and may be more experienced than universities in providing appropriate professional training. In Africa, for example, the Southern Africa Wildlife College (South Africa), the College of African Wildlife Management, Mweka (Tanzania) and the Ecole de Faune de Garoua (Cameroon) provide vocational programmes tailored to the needs of national and regional conservation practitioners. Some protected area agencies (e.g. in Kenya and Bhutan) have developed their own internal training and professional development programmes. Distance learning is also extending access to learning and knowledge: since launch in 2015 up until May 2020, the free certified online training programmes offered by the IUCN Programme on African Protected Areas and Conservation have attracted over 47,000 participants from over 120 countries (IUCN PAPACO, 2021).

Unlike established professions, however, the conservation sector lacks common competences and standards. This means that jobseekers with science-based academic qualifications are often inadequately prepared to enter the sector (Muir & Schwartz, Reference Muir and Schwartz2009), also creating an impression that only highly qualified scientists can be conservation professionals, and fuelling the demand for ever higher qualifications for the same job (‘qualification inflation’; Fuller & Raman, Reference Fuller and Raman2017, p. 4). Requirements for entrance exams or academic credentials may discriminate against Indigenous people and other highly competent individuals who have not benefited from conventional education.

The need to bridge the gap between mainly academic knowledge and conservation practice has been regularly highlighted (e.g. Whitten et al., Reference Whitten, Holmes and MacKinnon2001; Gossa et al., Reference Gossa, Fisher and Milner-Gulland2015) and is an issue likely to persist without common frameworks of professional competence and associated certification. Work is underway to address this, however. A competence register for protected area practitioners (Appleton, Reference Appleton2016) is increasingly being used to guide development of learning programmes, job descriptions and organizational structures, and similar register has been developed for threatened species recovery practitioners (Maggs et al., Reference Maggs, Appleton, Long and Young2021). The WIO-COMPAS programme has successfully pioneered the linking of competences, learning programmes and performance-based certification for marine protected area professional practitioners in the West Indian Ocean (WIOMSA, 2020). Beyond structured training and learning, some large conservation NGOs have developed formal continuing professional development programmes, and new professional networks, such as the Conservation Coaches Network, WildHub and CoalitionWILD, support professional development of conservationists through knowledge sharing, mentoring and co-development of new approaches and methods.

(4) Paid employment

A widespread definition of profession is that professionals are paid for their work (e.g. Cambridge University Press, 2020). In conservation, however, paid employment is a poor indicator of professional status, and the antonyms of professional (e.g. unprofessional, amateur) are potentially derogatory. Numerous volunteers commit their time and expertise freely and play substantive roles in most areas of conservation. For aspiring professionals seeking entry to the sector, volunteer or intern positions may be the only options (Hance, Reference Hance2017) and many skilled conservationists continue to work unpaid between periods of short-term employment, although the ethics and utility of unpaid conservation work are increasingly being questioned (Fournier & Bond, Reference Fournier and Bond2015). Many Indigenous people and local community members possess expertise analogous to that of acknowledged conservation professionals but are not specifically employed as conservationists. The term ‘paraprofessional’ has been used to describe Indigenous and local conservation co-workers (e.g. Painter & Kretser, Reference Painter and Kretser2012), but we suggest this term should be avoided because it could be seen as denigrating Indigenous and local knowledge and skills.

(5) Codes of conduct and ethics

A strong case for a common code for conservation professionals was made by Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Teh, Ota, Christie, Ayers and Day2017, p. 412): ‘Many other professions, including doctors, lawyers, engineers, accountants and teachers, have codes of conduct to establish a firm foundation for practice. However, there is no similar social standard or mechanism to guide the actions of individual conservation practitioners, organizations or governments, or to hold them accountable’. Codes exist for some aspects of conservation work, for example, research and field work in protected areas (Hockings et al., Reference Hockings, Adams, Brooks, Dudley, Jonas and Lotter2013), the work of rangers (International Ranger Federation, 2021) and ensuring respect for the cultural and intellectual heritage of Indigenous and local communities (the Tkarihwaié:ri Code adopted at the 10th Conference of Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity; CBD, 2010). Most international conservation NGOs have internal codes of conduct (e.g. WWF, 2009) as do professional associations in conservation-related fields such as the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM, 2019). Some peer-reviewed journals in the field of conservation have established ethical standards/codes of conduct for published research (e.g. Adams et al., Reference Adams, Balmford, McNeely, Maunder, Milner-Gulland, Racey and Robinson2001). As the conduct of conservation workers comes under increasing scrutiny (e.g. Warren & Baker, Reference Warren and Baker2019), the need for a common code is becoming more apparent, but codes alone are no guarantee against malpractice without mechanisms for monitoring, reporting on and responding to violations (Webley & Werner, Reference Webley and Werner2008).

(6) Individual commitment

Being professional implies a high degree of personal integrity and commitment, and conservationists are often expected to demonstrate exceptional dedication in a career that is for many ‘a vocation as well as a profession’ (E.J. Milner-Gulland, quoted in Hance, Reference Hance2017). But such commitment may lead employers and the public to assume that conservationists require lower remuneration than corporate employees (Fournier & Bond, Reference Fournier and Bond2015), favouring those able to afford the necessary personal and financial sacrifices (Hance, Reference Hance2017). This can potentially undermine professionalization; staff who are overworked, poorly paid, stressed and badly led are more likely to make mistakes, behave unprofessionally or even endure post-traumatic stress disorder (Belecky et al., Reference Belecky, Singh and Moreto2019). Although conservation is likely to remain a demanding occupation requiring particular commitment, the concept of a professional conservationist should not exclude those who are competent, committed and hard-working but who need to balance other life needs with the demands of work, or who are unable to engage in certain aspects of conservation work. This issue also affects public perceptions of conservationists as professionals. Strong commitment does not alone provide a mandate for conservation action and may even be perceived by some as indicating an ulterior financial motivation for doing the work (Holmes, Reference Holmes and Morvaridi2015).

(7) Organizational capacity

Effective professional employees need effective, professional organizations. Progress is being made on building professionalism of conservation NGOs, supported by initiatives such as Capacity for Conservation (2021) and organizations such as Maliasili (2020) and Well-Grounded (2021). Building the capacity of government conservation agencies is often more challenging for multiple reasons, including: inflexible systems and processes; resource shortages; inadequate working and employment conditions (Belecky et al., Reference Belecky, Singh and Moreto2019); issues of transparency, equity, inclusion and diversity that limit recruitment, retention and promotion opportunities (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Biggs, John, Sas-Rolfes and Barrington2015); limited access to training and professional development (Appleton et al., Reference Appleton, Ioniță and Stanciu2017); high personnel turnover, often linked to political changes or funding fluctuations; and discrimination against women, including gender-based violence (Castañeda Camey et al., Reference Castañeda Camey, Sabater, Owren and Boyer2020).

Failure to address organizational deficiencies has direct impacts on professionalizing conservation. It can lead to demotivation, lowering of standards, weak performance, public distrust, corruption (UNODC, 2019) and the loss from the sector of talented professionals frustrated at the lack of progress and opportunities. A workshop on this topic (BfN, 2017) identified four main requirements for government conservation agencies to be more effective: structures and systems that allow them to manage, collaborate and adapt to change effectively; proactive, confident and collaborative individuals who deliver effectively and inspire others; engagement in diverse and productive partnerships; and responsiveness to the needs of a society that understands and supports conservation goals.

Adoption of certified performance standards has the potential to build capacity and improve overall professionalism in conservation organizations. Such standards are increasingly being adopted for protected and conserved areas through the IUCN Green List of Protected and Conserved Areas (IUCN & WCPA, 2017), the Conservation Assured Tiger Standards (Conservation Assured, 2018), and the ISO 9000 and 14000 standards for management (Cabayan, Reference Cabayan2019; Dolomiti Bellunesi National Park, 2020).

(8) Professional associations

Established professions generally have formal members' associations whose main functions are summarized by Hurd & Lakhani (Reference Hurd and Lakhani2008, p. 5): ‘Professional associations essentially establish identity and dignity for the profession by setting minimum educational requirements, national certification standards and a code of ethics that outlines the expectations of professional behaviour for members of that profession … Associations also provide mechanisms for members to advance knowledge, disseminate information and network with their peers.’ Although some existing professional associations (e.g. the UK Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management and the US-based Society for Ecological Restoration) meet these criteria and encourage global membership, no global association exists specifically for conservation professionals. Several bodies fulfil some roles of professional associations but are not constituted as such. For example, the International Ranger Federation is actively promoting professionalization of rangers (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Galliers, Appleton, Hoffmann, Long and Cary-Elwes2021); members of the Society for Conservation Biology have access to professional development networks and opportunities; and the six IUCN Commissions have expert memberships, a code of conduct and a commitment to developing and promoting professional good practice. In the early 1990s the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (the precursor to the World Commission on Protected Areas) considered creating an international society of protected area managers and professionals within the Commission (Munro, Reference Munro1992), but this was never established. Conservation workers in some countries are represented by labour unions, which advocate for improved employment and working conditions.

Professionalization of conservation could still continue in an ad hoc way, but without a widely recognized body or set of related bodies to establish and uphold common standards and promote the profession in a consistent way, progress is likely to remain fragmented and favour only certain groups. A formal professional body or network could potentially (1) build a valued identity for the profession; (2) establish a global framework of standards for professional practice; (3) research sectoral needs, trends and policies, and lobby for change; (4) promote diversity, equity, inclusion and justice in the profession; (5) be a hub for sharing knowledge, experience and good practice; and (5) represent all conservation professionals.

Discussion

All eight aspects of professionalization considered here offer potential benefits for conservation, but there may also be risks. Among conservation NGOs, for example, Larsen (Reference Larsen2018) distinguished The Good (small, idealistic, commitment-driven); The Ugly (professionalized, managerial and internationally financed institutions that increasingly rely on a capitalistic expansion of activities, public finance entanglements and flawed corporate partnership projects) and the Dirty Harrys (pragmatic conservation operators in a world of money). The latter reflect a perceived shift towards neoliberalism (Humble, Reference Humble2019), defined by Lang (Reference Lang2013, p. 63) as ‘the processes through which social movements professionalize, institutionalize and bureaucratize in vertically structured, policy-outcome-oriented organizations that focus on generating issue-specific and, to some degree, marketable expert knowledge or services’. This emergence of corporate conservation, exemplified by the growth of the so-called BINGOs (big international NGOs), has attracted extensive criticism, including accusations of colonialism (Mbaria & Ogada, Reference Mbaria and Ogada2017), undue influence by business donors (Hance, Reference Hance2016), lack of concern for Indigenous issues and human rights (Tauli-Corpuz et al., Reference Tauli-Corpuz, Alcorn, Molnar, Healy and Barrow2020), and over-professionalization (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Hulme and Edwards2015).

Professionalization will also perpetuate exclusivity if it does not address exclusion of, and discrimination against, professionals based on race (Mbaria & Ogada, Reference Mbaria and Ogada2017; Gantheru, Reference Gantheru2020), geographical origin or gender (Jones & Solomon, Reference Jones and Solomon2019). Conservationists whose career paths and education do not conform to professional models could also become excluded. The emerging conservation profession needs to rigorously examine and, where necessary, reshape prevailing attitudes and conservation norms that perpetuate discrimination, exclusion and abuse of rights. Establishing formal structures that attempt to centralize the profession, restrict entry to certain groups and individuals, favour certain viewpoints and charge high membership fees could hinder professionalization. Exclusivity may also undermine trust among the wider public. In the context of heritage conservation, Lowenthal (Reference Lowenthal1999, p. 7) warned that ‘professionalisation … has served more to increase public distrust rather than trust: with it goes resentment that heritage concerns are dominated by elites and special interest groups, and suspicions of self-interest undermine appreciation of heritage as a public commodity’.

Overall, the conservation sector does not readily fit the model of a traditional profession. It is highly multidisciplinary, blending elements of many occupations to the extent that a single professional identity is difficult to define. Whereas most traditional professions are built around selling or providing a defined set of services to individuals or organizations, conservation seeks to deliver a wide suite of services to society as a whole, services that are often not easily defined or readily marketable and that may not be mandated. Most professions tend to concentrate knowledge, expertise and, in some cases, the right to practise within exclusive groups, whereas the global and interconnected nature of conservation requires an expansion and diversification of its practitioners.

Conservation therefore needs to develop its own distinctive professional profile. The starting point is clarifying who is a conservation professional. We see the sector comprising three broad and significantly overlapping groups:

Facilitators

This group mainly comprises policy makers, conservation staff of government agencies, international NGOs and donors, and many in the academic community. Largely English-speaking or multilingual, this group is based mainly in more developed and middle-to-upper income countries and urban areas. Because of the seniority, capacity, connections and resources of its members, this group has a major influence on shaping and directing conservation research, policy and practice, and consequently on defining the conservation profession. Considered by Holmes (Reference Holmes2011, p. 2) as a ‘transnational conservation elite’, this group has been associated with the advance of so-called neoliberal conservation. Some influential members of this group are not directly engaged in conservation practice and, although this group provides much of the raw material that drives and evaluates applied conservation activities through policy, publications and media, they are often considered by many practitioners to be out of touch with the realities and needs of conservation practice.

Conservation sector practitioners

With a focus on applying plans and policies, this group has much more direct impact on day-to-day conservation practice than the facilitators. Practitioners work in public sector bodies responsible for environmental protection, protected areas and natural resource management, and as staff of private protected areas, small NGOs and local offices of larger NGOs. Many do not have English as a first language, although increasing numbers have benefited from training abroad (mainly in English). They include large numbers of young professionals and volunteers, albeit often with significant knowledge and experience. We consider this practitioner group constitutes the under-represented majority of mainstream conservation professionals, with disproportionately limited influence on the profession's development and direction. Working in organizations that are usually understaffed and under-resourced, many are multifunctional generalists as well as subject specialists, with limited access to learning opportunities or to the networks and events in which the profession is shaped. Public sector workers in particular may be restricted from expressing strong personal or professional opinions publicly.

Community and Indigenous practitioners

We acknowledge that the concept and language of professionalism as used in this paper may not reflect the traditional cultures and viewpoints of many conservationists around the world. Nonetheless, we consider people who use Indigenous and local knowledge, and skilful leadership and governance to guide natural resource stewardship and conservation, to be as much professionals as university-trained conservation managers. For many in this group, conservation is integral to their lives rather than being a job, and they may work within different conceptualizations of the purpose and practice of conservation. This group is securing increased recognition but still has limited influence on the development and direction of conservation practice and the profession in general. Some members of this group may be uncomfortable with being labelled as professionals and may even find themselves in conflict with the other two groups.

For the conservation sector to be better respected and recognized, and for professionalization to be a positive process, it needs to be a broad and inclusive profession that reflects the full diversity of its practitioners and the complexity of its work. We consider that the future expansion of the sector will and should be close to areas of high conservation value and that therefore the direction of this emerging profession should be shaped and led more by practitioners in the second and third groups than it is at present.

Professional conservation practice should be rooted in good science from multiple disciplines but also requires significant social, cultural and political skills, alongside generic skills such as leadership, communication and entrepreneurship. It should blend rational thinking with creation, innovation and sensitivity to develop and apply solutions that reduce threats and achieve conservation goals in the context of constant ecological, social, political and economic change and uncertainty. This multifunctional role is best understood in the context of trans-professionalism, involving ‘deliberate exchange of knowledge, skills and expertise that transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries’ (Chiocchio & Richer, Reference Chiocchio, Richer, Gurtner and Soyez2015, p. 163). It should also be viewed as a shift from traditional, closed models of knowledge production to more decentralized, reflective and transdisciplinary approaches (Reihlen & Mone, Reference Reihlen, Mone, Reihlen and Werr2012) that are also transcultural. Alongside adopting the core elements of a profession (i.e. codes, standards, professional development), we should work towards the first of Mieg's (Reference Mieg2008, p. 50) two main routes for professionalization: an ‘integrated value-and-work based professionalisation based on individual expertise and shared values among diverse experts from different occupational groups, some without university education’, rather than his second, ‘academia-based professionalisation’. We should share Kiik's (Reference Kiik2019, p. 392) vision of ‘Conservationland’: ‘a transnational social world of nature conservation, including both expat and local–national professionals’.

In short, conservation professionals should not remain on either side of the bridge between theory and practice, or between traditional and scientific approaches, they should be the bridge itself, spanning the facilitating framework and applied conservation practice. Their work should involve building knowledge and expertise of all types and facilitating diagnosis, prescription, monitoring and communication (Abbott, Reference Abbott1988). Conservation professionals may work within and across the cultural frameworks of both mainstream and Indigenous and community conservation, according to the context and the rights and wishes of traditional owners and users. On this basis, we propose a broad definition of conservation professionals as ‘all those whose work diagnoses conservation needs and implements appropriate conservation action, both making use of and generating knowledge, evidence and policy’. This definition can apply to all kinds of conservation professionals, while recognizing that Indigenous and community professional frameworks have their own identities. These may overlap to varying extents with more globally established professional frameworks but should not be subsumed into them.

Recommendations

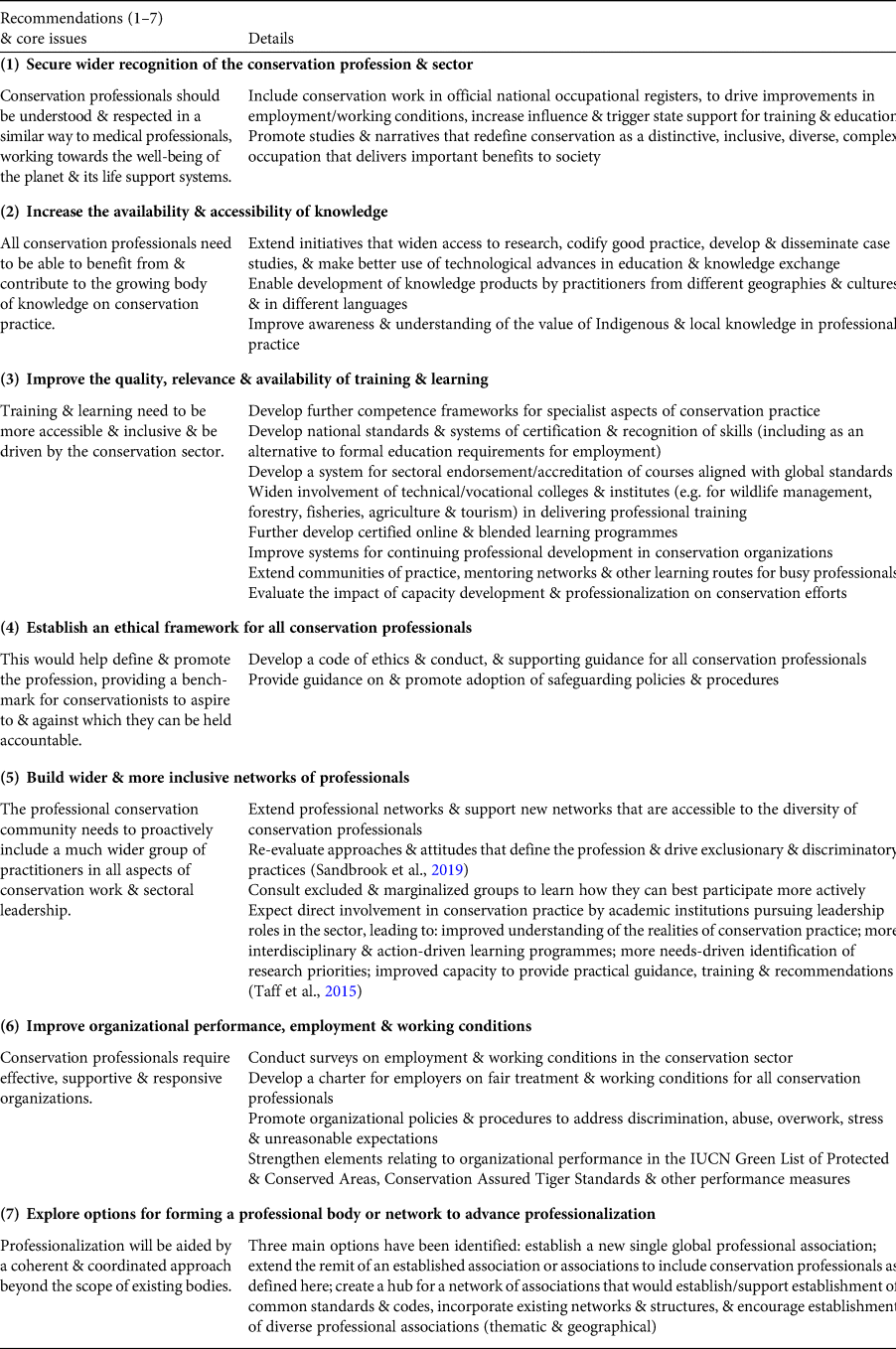

Table 1 outlines seven broad recommendations that we identify for advancing the professional attributes of the conservation sector and for creating a distinct, inclusive profession without constraining the benefits that come from the diverse and multidisciplinary nature of the sector. Specific measures for pursuing these recommendations will need to reflect the geographical, cultural and institutional contexts in which they are implemented. Figure 1 summarizes these recommendations in the context of the framework for conservation professionals set out here.

Fig. 1 Visualization of how conservation should be professionalized. The three intersecting groups that comprise the conservation sector operate at different scales (global, national, community, local, organizational). Based on our definition, the work of all conservation professionals should encompass the shaded area where these groups overlap, and should seek to expand these areas of overlap, within which our seven recommendations (Table 1) should be implemented.

Table 1 Seven general recommendations for advancing professionalization of conservation, with the core issues identified for each recommendation.

This review was stimulated by the need for a better understanding of the terms ‘professional’ and ‘professionalization’ in the context of conservation. Although both terms are widely used, this is the first such review that we are aware of. Our intention here is to encourage further studies and debate, and more importantly to encourage development of a distinctive and inclusive profession that can meet the challenges of conservation in the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Academy for Nature Conservation of the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation for supporting the workshop in 2017, where many of the ideas presented here first took shape. We acknowledge the contributions of organizers and participants at the 2019 London Capacity Building for Conservation Conference, at related conferences in Colombia (2013), Kenya (2015) and India (2017), at the III Latin American and Caribbean Congress of Protected Areas (2019) and the 9th World Ranger Congress (2019). We thank two anonymous reviewers and the Editor for their comments and suggestions, which helped improve and clarify this review.

Author contributions

Conception, writing: MRA; Fig. 1: NRO, MRA; literature search: ES; revision: all authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This review abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards and did not involve human or animal test subjects or the collection of specimens.