The weaning of pigs in commercial production is quite abrupt and done at an early age (14–28 d after birth)( Reference Maxwell, Carter, Lewis and Southern 1 , Reference Carroll, Veum and Matteri 2 ). It is characterised by changes in diet, separation from the sow, and environmental and social adaptations. These abrupt changes reduce the voluntary feed intake and disturb the health balance of the intestine( Reference Pluske, Hampson and Williams 3 ). The intestinal imbalance is associated with morphological and physiological changes that include intestinal inflammation, villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and reduced epithelial brush border activity( Reference Pluske, Hampson and Williams 3 , Reference Lallès, Boudry and Favier 4 ). Collectively, these factors favour diarrhoea, translocation of bacteria, and reduced digestive and absorptive capacity of small-intestinal enterocytes( Reference Lallès, Boudry and Favier 4 ), which result in a decrease in daily gain. In the past, the post-weaning disorders were kept under control using antibiotic growth promoters in weaning pig diets( Reference Williams, Verstegen and Tamminga 5 ). High concentrations of dietary minerals, e.g. Zn in the form of ZnO at doses well above the requirements (1000–3000 mg/kg feed), have been shown to decrease the incidence of post-weaning diarrhoea and gut disorders and to improve the growth performance of newly weaned pigs( Reference Hu, Xiao and Song 6 , Reference Hu, Gu and Luan 7 ). Current European legislation prohibits the incorporation of antibiotic growth promoters into animal diets (EC Regulation no. 1831/2003), and there are concerns within the European Union regarding the feeding of pharmacological doses of ZnO to pigs and the associated accumulation of Zn in the environment( Reference Broom, Miller and Kerr 8 , Reference Miller, Toplis and Slade 9 ).

Recently, studies have shown that dietary provision of a Laminaria spp.-derived seaweed extract containing laminarin and fucoidan promotes improved growth and feed efficiency in the absence of in-feed antibiotics( Reference Gahan, Lynch and Callan 10 , Reference McDonnell, Figat and O'Doherty 11 ). It is known that seaweed extract supplementation modulates the gut environment, possesses potent antibacterial and immunomodulatory properties, and enhances growth performance partly through the improvement of the digestive and absorptive functions of the intestine( Reference McDonnell, Figat and O'Doherty 11 – Reference Sweeney, Collins and Reilly 13 ). It has been shown that laminarin and fucoidan supplementation after weaning improves nutrient digestibility( Reference Walsh, Sweeney and O'Shea 14 ). Nutrient digestibility can be improved by increasing villus height (VH) in the small intestine and by increasing the numbers of nutrient transporters, e.g. monosaccharide transporters (sodium–glucose-linked transporters (SGLT/SLC5A) and GLUT/SLC2A)( Reference Wood and Trayhurn 15 ), small-peptide (dipeptide and tripeptide) transporters (PEPT/SLC15A)( Reference Daniel 16 ) and unesterified long-chain fatty acid transporters (cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36/FAT) and fatty acid-binding proteins (FABP/I-FABP))( Reference Hajri and Abumrad 17 , Reference Glatz and van der Vusse 18 ).

The hypothesis of the present study was that supplementation of the diet with laminarin and/or fucoidan after weaning would improve nutrient digestibility by improving gastrointestinal architecture in the small intestine as well as by increasing the numbers of nutrient transporters. A further objective was to determine whether laminarin inclusion could be considered as an alternative to ZnO supplementation.

Materials and methods

All experimental procedures were conducted under experimental licence from the Irish Department of Health in accordance with the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 and the European Communities (Amendments of the Cruelty to Animals Act, 1876) Regulations (1994).

Experimental design and animal management – Expt 1

Expt 1 was designed as a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement, comprising four dietary treatments. The dietary treatments were as follows: (T1) basal diet (control); (T2) basal diet+300 parts per million (ppm) laminarin; (T3) basal diet+240 ppm fucoidan; (T4) basal diet+300 ppm laminarin and 240 ppm fucoidan. Both laminarin and fucoidan were included in the diet during manufacture, and the concentrations of laminarin and fucoidan used were based on previous work carried out by Walsh et al. ( Reference Walsh, Sweeney and O'Shea 14 ). Laminarin (990 g laminarin/kg) and fucoidan (720 g fucoidan/kg, 180 g/kg crude protein and 100 g/kg ash) were derived from Laminaria spp. and sourced from BioAtlantis Limited. The diets were provided ad libitum in a meal form after weaning for 9 d, after which the pigs were humanely killed. The diets were formulated to have similar digestible energy (14·5 MJ/kg) and standardised ileal digestible lysine (12·5 g/kg) contents. All amino acid requirements were met relative to lysine( 19 ). Ingredient composition and chemical analysis composition of the basal diet used in Expt 1 are given in Table 1.

Table 1 Ingredient composition and chemical analysis composition of the basal diet (g/kg, unless otherwise indicated) used in Expt 1 and 2

* Provided (mg/kg complete diet): Cu, 100; Fe, 140; Mn, 47; Zn, 120; I, 0·6; Se, 0·3; retinol, 1·8; cholecalciferol, 0·025; α-tocopherol, 67; phytylmenaquinone, 4; cyanocobalamin, 0·01; riboflavin, 2; nicotinic acid, 12; pantothenic acid, 10; choline chloride, 250; thiamin, 2; pyridoxine, 0·015. Celite included at 300 mg/kg complete diet.

† Calculated for tabulated nutritional composition( Reference Sauvant, Perez and Tran 54 ).

For Expt 1, twenty-eight pigs (progeny of Large White × (Large White × Landrace sows)) were selected from a commercial pig unit at 24 d of age, with a weaning weight of 6·9 kg (sd 0·44 kg). The pigs were blocked on the basis of litter of origin and body weight, and they were randomly assigned to one of the four dietary treatments (n 7 replicates/treatment). The pigs were individually housed in a fully slatted pen (1·68 m × 1·22 m). House temperature was thermostatically controlled at 30oC throughout the experiment. The pigs were fed ad libitum from a four-space feeder with trays placed underneath the feeder to avoid wastage of feed. Water was available from nipple drinkers at all time points. Food was available up to weighing of the pigs and then weighed back for the purpose of calculating feed intake. Representative feed samples of each dietary treatment were collected on day 0. The pigs were weighed at the beginning of the experiment (day of weaning: day 0) and at the end of the experiment (day 9). Multiple fresh faecal samples were collected daily from all pens on days 6–9 for nutrient digestibility analyses using the acid-insoluble ash technique( Reference McCarthy, Aherne and Okai 20 ).

On day 9, all pigs were weighted and humanely killed by lethal injection of Euthatal (Pentobarbitone sodium BP; Merial Animal Health Limited) to the cranial vena cava at a rate of 1 ml/1·4 kg body weight. On removal of the digestive tract, sections of the ileum (15 cm from caecum) were excised: one part was fixed in 10 % phosphate-buffered formalin for morphological analysis and another part was opened along the mesentery, emptied and gently washed using sterile PBS (Oxoid) and stored in RNAlater solution (Applied Biosystems) overnight at 4°C. RNAlater was then removed, and samples were stored at − 70°C until RNA extraction.

Experimental design and animal management – Expt 2

Expt 2 was designed as a complete randomised block design comprising three dietary treatments. The dietary treatments were as follows: (T1) basal diet (control); (T2) basal diet+300 ppm laminarin; (T3) basal diet+3100 ppm ZnO from day 0 to day 14 and 2600 ppm ZnO from day 15 to day 32. The concentrations of laminarin and ZnO used were based on previous work carried out by McDonnell et al. ( Reference McDonnell, Figat and O'Doherty 11 ) and O'Doherty et al. ( Reference O'Doherty, Nolan and McCarthy 21 ), respectively. Laminarin was derived from Laminaria spp. and sourced from BioAtlantis Limited, and ZnO was sourced from Provimi Limited. The diets were provided ad libitum in a meal form for 32 d after weaning. The diets were formulated to have similar digestible energy (14·5 MJ/kg) and standardised ileal digestible lysine (12·5 g/kg) contents. All amino acid requirements were met relative to lysine( 19 ). Ingredient composition and chemical analysis composition of the basal diet used in Expt 2 are given in Table 1.

In Expt 2, forty-eight pigs (progeny of Large White × (Large White × Landrace sows)) weaned at 24 d, with an initial weight of 7·0 kg (sd 0·67 kg), were used. The pigs were blocked on the basis of live weight and litter of origin and were randomly assigned to one of the three treatments (n 8 replicates/treatment, n 2 pigs/replicate). The pigs were housed in pairs on a fully slatted pen (1·68 m × 1·22 m). House temperature was thermostatically maintained at 30oC for the first 7 d and then reduced by 2oC per week. The pigs were weighed at the beginning of the experiment (day of weaning: day 0), day 7, day 14, day 21 and day 32. The pigs were fed ad libitum from a four-space feeder with trays placed underneath the feeder to minimise wastage of feed. Water was available ad libitum from nipple drinkers. Food was available until the pigs were weighed and then weighed back for the purpose of calculating feed intake. Representative feed samples of each dietary treatment were collected at regular intervals throughout the experiment for chemical analysis. Multiple fresh faecal samples were collected daily from all pens on days 10–15 for nutrient digestibility analyses using the acid-insoluble ash technique( Reference McCarthy, Aherne and Okai 20 ) and volatile fatty acid (VFA) analyses. For VFA analyses, samples were mixed with sodium benzoate and phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride to stop any bacterial activity and minimise the effects of post-thawing fermentation on resulting VFA. The samples were then stored at − 20oC for VFA analyses. Multiple fresh faecal samples were collected from all pens on day 10 and stored at − 20oC for microbial genomic DNA analysis.

Laboratory analyses

Ileum morphological analysis – Expt 1

Preserved ileal tissue samples were prepared using standard paraffin-embedding techniques. The samples were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and stained with haemotoxylin and eosin( Reference Pierce, Sweeney and Brophy 22 ). VH and crypt depth (CD) were measured in the stained sections (4 × objective) using a light microscope fitted with an image analyser (Image-Pro Plus; Media Cybernetics). Measurements of fifteen well-orientated and intact villi and crypts were taken for each segment. VH was measured from the crypt–villus junction to the tip of the villus, and CD was measured from the crypt–villus junction to the base. Results are expressed as mean VH or CD in μm.

RNA extraction, complementary DNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR – Expt 1

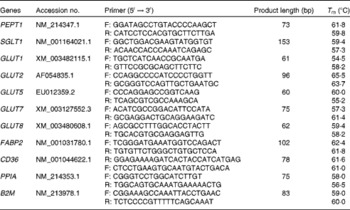

RNA was purified using the phenol–chloroform extraction method. Total RNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg of tissue samples using the GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich). Total RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop-ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RNA integrity was assessed on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, and all RNA integrity number values were >8·9 (Agilent Technology). Complementary DNA was synthesised from 1 μg of total RNA using the Superscript™ III First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) and oligo(dt) primers following the manufacturer's instructions. The final reaction volume of 20 μl was then adjusted to 120 μl using nuclease-free water. The quantitative real-time PCR assay mixtures were prepared in a total volume of 20 μl, containing 10 μl Fast SYBR PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 1·8 μl forward and reverse primer mix (300 nm), 5·7 μl nuclease-free water and 2·5 μl complementary DNA. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out in duplicate on the 7500 ABI Prism Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Thermocycling conditions were as follows: 95oC for 10 min for one cycle, followed by 95oC for 15 s and 60oC for 1 min for forty cycles. Dissociation analyses of the PCR products confirmed the specificity of all targets. All primers for the selected nutrient transporters (PEPT1/SLC15A1, SGLT1/SLC5A1, GLUT1/SLC2A1, GLUT2/SLC2A2, GLUT5/SLC2A5, GLUT7/SLC2A7, GLUT8/SLC2A8, FABP2/I-FABP and CD36/FAT) are presented in Table 2. All primers were designed using the Primer ExpressTM Software (Applied Biosystems) and synthesised by MWG Biotech. Dissociation analyses of the PCR products were carried out to confirm the specificity of the resulting PCR products. All samples were prepared in duplicate. The mean cycle threshold values of duplicates of each sample were used for calculations. Normalised relative quantities were obtained using the qbase PLUS software (Biogazelle) from two stable housekeeping genes (β-2-microglobulin (B2M) and peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA)).

Table 2 Swine-specific primers used for real-time PCR in Expt 1

PEPT, peptide transporter; F, forward; R, reverse; SGLT, sodium–glucose-linked transporter; FABP, fatty acid-binding protein; CD36, cluster of differentiation 36; PPIA, peptidylprolyl isomerase A; B2M, β-2-microglobulin.

Extraction and quantification of microbial DNA from faecal samples – Expt 2

Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from faecal samples using the QIAamp DNA Stool Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND1000; Thermo Scientific). Standard curves were prepared as described by O'Shea et al. ( Reference O'Shea, Sweeney and Bahar 23 ). Briefly, genomic DNA from all faecal samples were pooled and amplified through routine PCR using Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus spp. and Escherichia coli specific primers. For Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp., the primer sequences were as follows: Bifidobacterium spp. – forward 5′-GCGTGCTTAACACATGCAAGTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CACCCGTTTCCAGGAGCTATT-3′, 59°C, 125 bp( Reference Penders, Vink and Driessen 25 ); and Lactobacillus spp. forward 5′-AGCAGTAGGGAATCTTCCA-3′ and reverse 5′-CACCGCTACACATGGAG-3′, 55°C, 341 bp( Reference Metzler-Zebeli, Hooda and Pieper 26 ). Serial dilutions of these amplicons served to generate standard curves using quantitative real-time PCR (ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems Limited) permitting estimations of absolute quantification based on gene copy number( Reference Lee, Kim and Shin 27 ). Real-time PCR were carried out in a final reaction volume of 20 μl containing 1 μl template DNA, 1 μl forward and reverse primers (100 pm), 10 μl SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 8 μl nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling conditions involved an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min followed by forty cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 1 min. Dissociation analyses of the PCR products were carried out to confirm the specificity of the resulting PCR products.

To enhance the specificity of E. coli detection, a dual-labelled probe containing 6-carboxyfluorescein as the reporter dye and 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine as the 3′ quencher dye was used (MWG Operon). The primer and probe sequence set for E. coli were as follows: forward 5′-CATGCCGCGTGTATGAAGAA-3′, 5′-CGGGTAACGTCAATGAGCAAA-3′ (probe), 59°C, reverse 5′-TATTAACTTTACTCCCTTCCTCCCCGCTGAA-3′, 68°C, 96 bp( Reference Huijsdens, Linskens and Mak 24 ). The real-time PCR was carried out in a final reaction volume of 20 μl, containing 1 μl template DNA, 1 μl forward and reverse primers (100 pm), 1 μl probe (250 nm), 8 μl Mastermix 16S Basic, 0·64 μl Taq polymerase (Molzym) and 8·36 μl nuclease-free water. Thermocycling conditions during PCR were as those described above, apart from the absence of an initial denaturation step. Thus, reagents were prepared on ice. The mean threshold cycle values from the triplicate of each sample were used for calculations. Estimates of gene copy numbers for selected bacteria were log-transformed, and they are presented as gene copy numbers/g fresh faeces.

Coefficient of total tract apparent digestibility – Expt 1 and 2

Feed and faecal samples were analysed for N, DM, organic matter, ash, gross energy (GE) and neutral-detergent fibre (NDF). Following collection, faecal samples were dried at 100oC for 48 h. The feed samples and dried faecal samples were milled through a 1 mm screen (Christy and Norris Hammer Mill). DM content was determined after drying overnight at 103oC. Ash content was determined after ignition of a known weight of concentrates in a muffle furnace (Nabertherm) at 500oC for 4 h. N content was determined using the LECO FP 528 instrument (Leco Instruments). Neutral-detergent fibre content was determined according to the method of Van Soest et al. ( Reference Van Soest, Robertson and Lewis 28 ) using the Ankom 220 Fibre Analyser (AnkomTM Technology). GE content was determined using a Parr 1201 oxygen bomb calorimeter (Parr). Total laminarin content in the diets was determined using a commercial assay kit (K-YBGL; Megazyme International Ireland Limited). Fucoidan content in the diets was determined according to the method described by Usov et al. ( Reference Usov, Smirnova and Klochkova 29 ). Thawed faecal samples were analysed for VFA concentration and profile using the method of O'Connell et al. ( Reference O'Connell, Callan and O'Doherty 30 ).

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analysed as a 2 × 2 factorial, randomised complete block design using the general linear model procedure of SAS (version 6.12; SAS Institute, Inc.). The statistical model used included the main effects of laminarin, fucoidan and block and the associated interaction between laminarin and fucoidan. In Expt 2, data were analysed as a complete randomised block design. The model included block and treatment and their associated interaction. The pig was the experimental unit in Expt 1, while pen was the experimental unit in Expt 2. All the data were initially checked for normality using the PROC univariate procedure in SAS (version 6.12; SAS Institute, Inc.). Gene copy estimates of selected bacteria and nutrient transporters were log-transformed before statistical analysis. The probability level that denotes significance is P< 0·05, while P values between 0·05 and 0·1 are considered numerical tendencies. Data are presented as least-square means with their standard errors.

Results

Expt 1

Performance – 0 to 9 d

No difference was recorded in average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI) and gain:feed (G:F) ratio among the treatment groups (P>0·05; Table 3).

Table 3 Effects of dietary laminarin and fucoidan on pig growth performance (0–9 d) and nutrient digestibility coefficient in Expt 1 (Least-square mean values with their standard errors)

Control, basal diet; LAM, basal diet+300 parts per million (ppm) laminarin; FUC, basal diet+240 ppm fucoidan; LAM+FUC, basal diet+300 ppm laminarin and 240 ppm fucoidan; ADG, average daily gain; ADFI, average daily feed intake; G:F, gain:feed; CTTAD, coefficient of total tract apparent digestibility of nutrients.

* P< 0·05.

Coefficient of total tract apparent digestibility

The effects of laminarin and fucoidan supplementation on the coefficient of total tract apparent digestibility (CTTAD) of nutrients are presented in Table 3. There was an interaction between laminarin and fucoidan on the CTTAD of DM, ash and GE (P< 0·05). Pigs fed the laminarin diet alone had increased CTTAD of DM, ash and GE compared with those fed the basal diet. However, there was no effect of laminarin supplementation on the CTTAD of DM, ash and GE when combined with fucoidan. Laminarin supplementation increased the CTTAD of N compared with the non-laminarin treatments (P< 0·05).

Ileal morphology

There was no effect of laminarin or fucoidan supplementation on VH, CD or VH:CD (VH:CD) ratio in the ileum (P>0·05). The overall mean for VH, CD and VH:CD ratio was 265·8 μm, 267·3 μm and 1·0, respectively.

Gene expression of nutrient transporters in the ileum on day 9

There was an interaction between laminarin and fucoidan on GLUT1, GLUT2 and SGLT1 expression (P< 0·05) in the ileum. Pigs fed the laminarin diet alone had increased GLUT1, GLUT2 and SGLT1 expression compared with those fed the basal diet. However, there was no effect of laminarin supplementation on GLUT1, GLUT2 and SGLT1 expression when combined with fucoidan. There were no effects of dietary treatments on PEPT1, GLUT5, GLUT7, GLUT8, CD36 and FABP2 (P>0·05) expression (Table 4).

Table 4 Effects of fucoidan and laminarin supplementation on the normalised relative abundance of nutrient transporter mRNA in the ileal tissue of weaned pigs (Least-square mean values with their standard errors)

Control, basal diet; LAM, basal diet+300 parts per million (ppm) laminarin; FUC, basal diet+240 ppm fucoidan; LAM+FUC, basal diet+300 ppm laminarin and 240 ppm fucoidan; PEPT, peptide transporter; SGLT, sodium–glucose-linked transporter; FABP, fatty acid-binding protein; CD36, cluster of differentiation 36.

a,bMean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P< 0·05).

* P< 0·05.

Expt 2

Performance

The effects of laminarin and ZnO supplementation on ADG, ADFI and G:F ratio are presented in Table 5. Neither laminarin nor ZnO supplementation affected ADG, ADFI and G:F ratio during the first 7 d post-weaning (P>0·1). Pigs fed the ZnO diet had increased ADG and G:F ratio compared with those fed the laminarin diet (P< 0·05) during days 7–14. Pigs fed the laminarin diet had higher ADG (P< 0·05) compared with those fed the basal and ZnO diets during days 14–21 and 21–32. Pigs fed the laminarin diet had higher (P< 0·05) ADG and G:F ratio compared with those fed the basal diet during the whole study period (days 0–32). There was no difference in the effects of the laminarin and ZnO diets on ADG and G:F ratio during the whole study period (P>0·05).

Table 5 Effects of laminarin and zinc oxide supplementation on pig performance in Expt 2 (Least-square mean values with their standard errors)

Control, basal diet; LAM, basal diet+300 parts per million (ppm) laminarin; ZnO, basal diet+3100 ppm ZnO from day 0 to day 14 and 2600 ppm of ZnO from day 15 to day 32; ADG, average daily gain; ADFI, average daily feed intake; G:F, gain:feed.

a,bMean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P< 0·05).

Coefficient of total tract apparent digestibility

The effects of laminarin and ZnO supplementation on the CTTAD of nutrients are presented in Table 6. The laminarin diet increased the CTTAD of DM, organic matter, ash, neutral-detergent fibre and GE compared with the basal and ZnO diets (P< 0·05). There was a decrease in the CTTAD of DM, organic matter, ash, GE and N in pigs fed the ZnO diet compared with that in pigs fed the basal and laminarin diets (P< 0·05). Pigs fed the ZnO diet had lower CTTAD of neutral-detergent fibre compared with those fed the laminarin diet.

Table 6 Effects of dietary treatment on the coefficient of total tract apparent digestibility (CTTAD, g/kg) in Expt 2 (Least-square mean values with their standard errors)

Control, basal diet; LAM, basal diet+300 parts per million (ppm) laminarin; ZnO, basal diet+3100 ppm ZnO from day 0 to day 14 and 2600 ppm of ZnO from day 15 to day 32; OM, organic matter; NDF, neutral-detergent fibre; GE, gross energy.

a,b,cMean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P< 0·05).

Faecal microbiology and volatile fatty acids

The effects of laminarin and ZnO supplementation on selected faecal microbial populations and faecal VFA are presented in Table 7. Pigs fed the ZnO diet had decreased populations of E. coli and Bifidobacterium compared with those fed the basal and laminarin diets. Pigs fed the laminarin diet had increased numbers of Lactobacillus spp. compared with those fed the basal and ZnO diets.

Table 7 Effects of laminarin and ZnO supplementation on faecal populations of Escherichia coli, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. and concentrations of faecal volatile fatty acids (VFA) in Expt 2 (Least-square mean values with their standard errors)

Control, basal diet; LAM, basal diet+300 parts per million (ppm) laminarin; ZnO, basal diet+3100 ppm ZnO from day 0 to day 14 and 2600 ppm ZnO from day 15 to day 32.

a,bMean values within a row with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P< 0·05).

* Log10 colony-forming units/g digesta.

Pigs fed the ZnO diet had a decreased total faecal VFA concentration compared with those fed the basal diet (P< 0·01). There was no effect of laminarin supplementation on total VFA concentration (P>0·05). Pigs fed the ZnO diet had a decreased proportion of acetic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid compared with those fed the basal diet (P< 0·05). Pigs fed the laminarin diet had a lower proportion of propionic acid compared with those fed the basal diet (P< 0·05).

Discussion

The hypothesis of Expt 1 was that supplementation with laminarin and fucoidan, independently or in combination, increases nutrient digestibility in weaned pigs through an improved gastrointestinal architecture in the small intestine and an increased number of nutrient transporters. A further objective was to determine whether laminarin inclusion could be considered as an alternative to ZnO supplementation in weaned pig diets. The results of the present study demonstrate that laminarin supplementation increases the expression of GLUT in the ileum (SGLT1, GLUT1 and GLUT2). This improvement might be related to the improvement in nutrient digestibility of the diet. Furthermore, in Expt 2, laminarin supplementation improved growth performance after 2 weeks post-weaning. This was probably through improved nutrient digestibility and increased number of Lactobacillus spp.

In Expt 1, the performance levels were similar between the treatment groups. The lack of response in growth performance was probably due to the duration of the experiment (9 d). However, longer duration studies (e.g. 21 d) have shown positive effects of laminarin and fucoidan on ADG and G:F ratio( Reference McDonnell, Figat and O'Doherty 11 , Reference O'Doherty, McDonnell and Figat 31 ). Pigs fed the laminarin diet alone had increased CTTAD of DM, ash, N and GE. Nutrient digestibility can be increased by improving VH in the small-intestinal epithelium and by increasing the numbers of nutrient transporters during the weaning period. Changes in the diet and reduction in voluntary feed intake during the weaning period result in intestinal villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia( Reference Pluske, Hampson and Williams 3 , Reference Lallès, Boudry and Favier 4 ), and as a consequence, the expression of nutrient transporters is down-regulated( Reference Boudry, Peron and Le Huerou-Luron 32 , Reference Pluske, Piva, Bach Knudsen and Lindberg 33 ). In Expt 1, there was no difference in VH, CD and VH:CD ratio in the ileum between the treatment groups, resulting in similar absorptive area between the treatment groups. In an identical experiment, Walsh et al. ( Reference Walsh, Sweeney and O'Shea 14 ) found no significant effect of laminarin or fucoidan on VH in either the ileum or the jejunum. However, supplementation with both laminarin and fucoidan significantly increased VH and VH:CD ratio in the duodenum.

Pigs fed the laminarin diet had higher SGLT1, GLUT1 and GLUT2 expression in the ileum, which may partially explain the increase in nutrient digestibility in this group of pigs, as these nutrient transporters are responsible for transporting glucose from the intestinal lumen to the enterocyte and then to the blood stream. The protein levels of SGLT1 and GLUT2 are crucial to the absorption and uptake of glucose in the small intestine( Reference Rodriguez, Guimaraes and Matthews 34 , Reference Sangild, Tappenden and Malo 35 ). A wide range of monosaccharides are effective in enhancing the expression of GLUT( Reference Shirazi-Beechey, Hirayama and Wang 36 , Reference Lescale-Matys, Dyer and Scott 37 ). The up-regulation of GLUT (SGLT1, GLUT1 and GLUT2) expression with laminarin supplementation in the present study may be due to the chemical structure (β-(1 → 3)-linked glucans with β-(1 → 6)-linked side chains)( Reference Read, Currie and Bacic 38 , Reference Brown 39 ) and/or molecular weight (approximately 5 kDa)( Reference Ruperez, Ahrazem and Leal 40 ) of laminarin. Fucoidan has a higher molecular weight (43–1600 kDa)( Reference Ruperez, Ahrazem and Leal 40 ) and a different structure (fucose-linked in α-(1 → 3) containing sulphated polysaccharides)( Reference Berteau and Mulloy 41 ). This may explain the absence of an effect of fucoidan on the up-regulation of nutrient transporter expression.

In Expt 2, dietary treatments did not affect pig performance during the first week post-weaning. During the second week, pigs fed the ZnO diet had higher ADG and G:F ratio compared with those fed the laminarin diet. However, during the third and fourth weeks, pigs fed the laminarin diet had higher ADG and G:F ratio compared with those fed the basal and ZnO diets. There was no effect of laminarin or ZnO supplementation on ADFI. Carlson et al. ( Reference Carlson, Hill and Link 42 ) suggested that nursery pigs need to be fed ZnO-supplemented diets for at least 2 weeks after weaning for any growth-promoting effects to become apparent, implying that at least 1 week pre-test (or preloading) period may be required for clear ZnO responses in growth rate. Increased growth without an associated increase in feed intake indicates that the effects of laminarin and ZnO on growth performance involve a more complex mechanism than simply enhancing feed intake.

The mode of action of ZnO and its associated growth-promoting effects in the young pig remains unclear. The improvement in growth in Expt 2 could be due to a number of reasons. First, the higher growth rate of pigs fed the ZnO diet observed in the second week of Expt 2 may be attributable to the reduction in E. coli population. In studies carried out by different authors( Reference Hu, Xiao and Song 6 , Reference Hu, Gu and Luan 7 , Reference Molist, Hermes and Segura 43 – Reference Roselli, Finamore and Garaguso 45 ), dietary ZnO has been shown to reduce the incidence of diarrhoea in weaned pigs, by reducing E. coli colonisation. Second, the decrease in E. coli population in pigs fed the ZnO diet was also associated with a reduction in protein fermentation in the colon. The reduction in the concentrations of isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid and valeric acid indicates a reduction in protein fermentation as these short-chain fatty acids are exclusively derived from protein fermentation( Reference Macfarlane, Gibson and Beatty 46 , Reference O'Shea, Lynch and Callan 47 ). Such fermentation can lead to the formation of toxic metabolites such as NH3 and amines( Reference Russell, Sniffen and Van Soest 48 ) that have been implicated in the clinical expression of diarrhoea( Reference Macfarlane and Macfarlane 49 ). Furthermore, the reduction in total VFA concentration in pigs fed the ZnO diet indicates a decrease in microbial activity in the gastrointestinal tract( Reference Macfarlane and Macfarlane 49 ). This may also explain the reduction in the decreased CTTAD of N in this diet. It is known that E. coli breaks down protein as an energy source for its metabolism( Reference Macfarlane and Macfarlane 49 ). However, the digestibility measurements were made over the entire gastrointestinal tract, something that may not be accurate because of microbial fermentation in the large intestine. It has been shown that there is significant metabolism of dietary nutrients in the large intestine( Reference Sauer and Ozimek 50 ), and subsequently the apparent faecal digestibility method has been labelled as an inaccurate method for the measurement, especially of protein and amino acid digestibility.

The improved performance of pigs fed the laminarin diet observed in the third and fourth weeks of the Expt 2 may be due to a number of reasons. First, the improved performance may be attributable to the improved nutrient digestibility of the diets, and second, the improved performance can be attributable to an increase in Lactobacillus spp. population. The improvement in nutrient digestibility is in agreement with Expt 1 and other studies( Reference McDonnell, Figat and O'Doherty 11 , Reference O'Doherty, McDonnell and Figat 31 ), where pigs fed diets containing laminarin had higher CTTAD of gross energy compared with those fed the basal diet.

The increased nutrient digestibility, as a result of laminarin supplementation, may also be due to the increase in the Lactobacillus population. This would suggest that a proportion of the supplemented laminarin is escaping hydrolysis in the foregut and passing into the colon for bacterial fermentation. Furthermore, these bacteria have an ability to produce a wide range of cell-associated polysaccharide depolymerases that may aid in nutrient digestion( Reference O'Doherty, McDonnell and Figat 31 ). Laminarin has been shown previously to exhibit prebiotic properties by increasing the populations of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. in the large intestine( Reference Mathers, Annison, Samman and Annison 51 , Reference Jaskari, Kontula and Siitonen 52 ), thus having a positive effect on gut health. The positive response of growth performance to laminarin may also be attributable to its immunomodulatory effects( Reference Sweeney, Collins and Reilly 13 , Reference Walsh, Sweeney and O'Shea 14 ). Laminarin supplementation has been shown to suppress the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines( Reference Walsh, Sweeney and O'Shea 14 ). It has been shown that low activation of the immune system during the weaning period could result in an improvement in growth performance( Reference Li, Li and Xing 53 ). However, in the present study, the immunomodulatory effects of laminarin were not measured.

In conclusion, the up-regulation of gene expression of GLUT (GLUT1, GLUT2 and SGLT1), the increase in ADG and G:F ratio, the increase in nutrient digestibility and the increase in the population of Lactobacillus spp. suggest that laminarin may provide a dietary means to improve gut health and pig growth performance after weaning.

Acknowledgements

The present study was financially supported by the Enterprise Ireland Innovation Partnership Programme (Enterprise Ireland) and BioAtlantis Limited (grant no. IP 2009 0030). Enterprise Ireland and BioAtlantis had no role in the design and analysis of the study or in the writing of this manuscript.

The authors' contributions were as follows: G. H. wrote the manuscript, collected samples and carried out the laboratory analyses; J. V. O. D. was the principal investigator responsible for the design of the experiments, supervision of data collection and statistical analysis and correction of the manuscript; T. S. designed the study and corrected the manuscript; A. M. W., D. N. D., C. J. O. S. and M. T. R. contributed to data collection and laboratory analyses; G. H. and M. T. R. contributed equally to the laboratory work. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

None of the authors had a financial or personal conflict of interest in relation to the present study.