Introduction

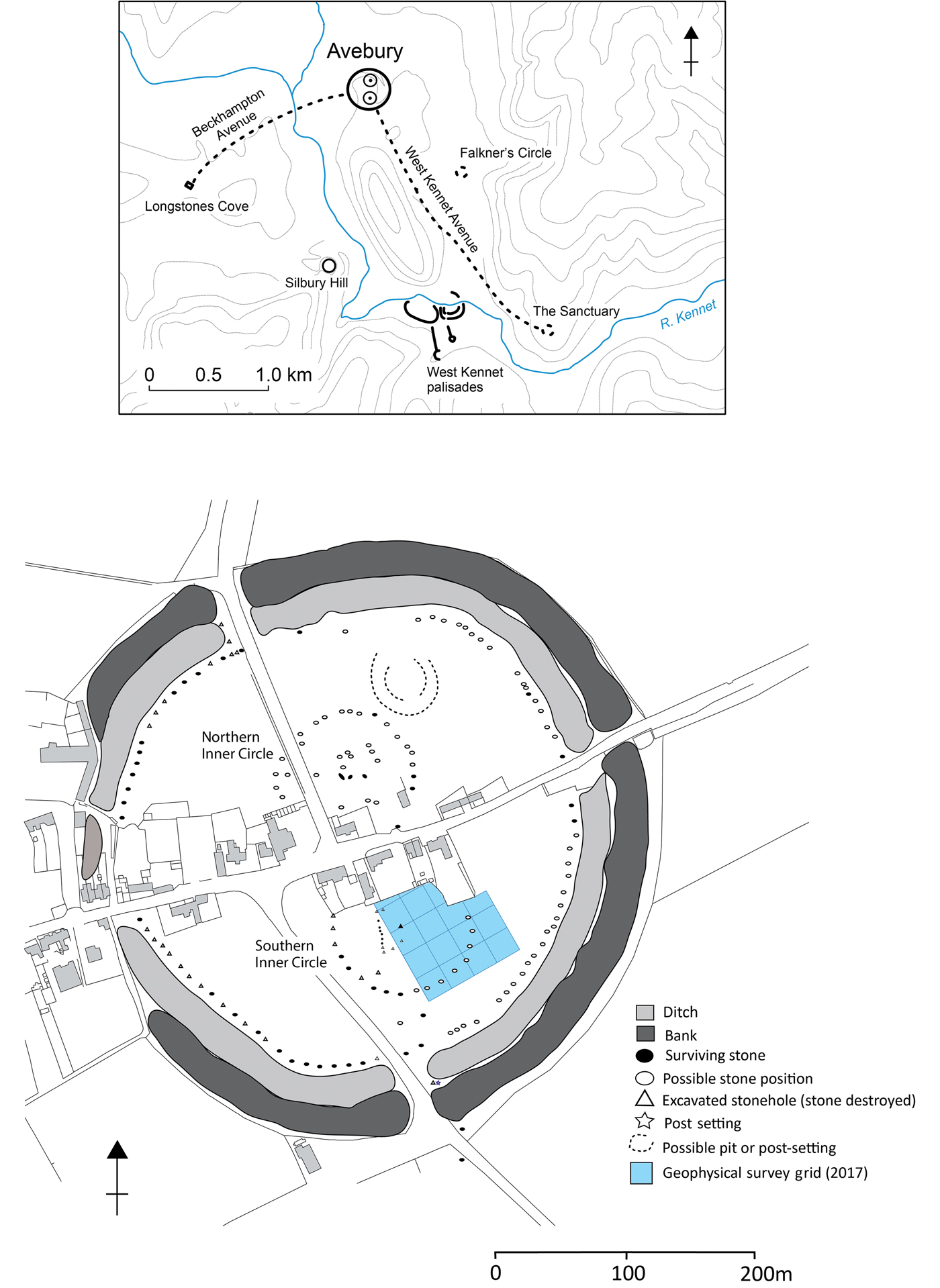

Alongside Stonehenge, the passage graves of the Boyne Valley and the Carnac alignments, the Avebury henge is one of the pre-eminent megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic. Its 420m-diameter earthwork encloses the world's largest stone circle. This in turn encloses two smaller yet still vast megalithic circles—each approximately 100m in diameter—and complex internal stone settings (Figure 1). Avenues of paired standing stones lead from two of its four entrances, together extending for approximately 3.5km and linking with other monumental constructions. Avebury sits within the centre of a landscape rich in later Neolithic monuments, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures (Smith Reference Smith1965; Pollard & Reynolds Reference Pollard and Reynolds2002; Gillings & Pollard Reference Gillings and Pollard2004).

Figure 1. The Avebury monument (incorporates data (c) Crown Copyright/database right 2007; an Ordnance Survey/(EDINA) supplied service) (figure by the authors).

Avebury and Stonehenge are inscribed within the same World Heritage Site. While recent programmes of research have contributed much to enhance our understanding of the prehistory of Stonehenge (Parker Pearson Reference Parker-Pearson2012), the same cannot be said for Avebury. The last major programme of excavation within the henge was undertaken by Alexander Keiller in the 1930s (Smith Reference Smith1965). Furthermore, reliable dates for the hypothesised construction phases at Avebury and other monuments in its environs remain scarce (Pollard & Cleal Reference Pollard, Cleal, Pollard and Cleal2004). We can be confident that the main Avebury earthwork was created around 2500 cal BC, but this seals a primary earthen bank whose precise date is uncertain; there is similar ambiguity with regard to the dating of the Southern and Northern Inner Circles and the megaliths that they enclose. Secure knowledge of the monument's chronology is essential, as it frames our understanding of how the henge and its megalithic settings came into being—whether through incremental development or as a single notionally planned entity. On the basis of the current evidence, we prefer the former scenario. Here, we make the case for a long history for the monument's initial development, arguing that events pre-dating the first phases of earthwork construction and stone erection at Avebury had a direct bearing on the monument's subsequent development. This in turn forces us to consider how matters of landscape inhabitation and historical memory relate to the origins of great monuments (Barrett Reference Barrett1994; Pollard Reference Pollard and Gibson2012, Reference Pollard and Hinzin press).

Avebury before the henge

By the second and third quarters of the fourth millennium BC, the Upper Kennet Valley of central southern England, within which Avebury is located, had become a major focus for settlement, tomb building and periodic gatherings (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Bayliss, Healy, Whittle, Healy and Bayliss2011). Several areas of occupation spanning from the fourth into the earliest third millennium BC can be identified on and around the low saddle of ground upon which the Avebury henge was constructed. During the 1930s, excavations under the western circuit of the henge bank yielded sherds of earlier Neolithic (4000–3400 cal BC) plain bowl pottery and worked flint (Smith Reference Smith1965: 224–26). These might be linked to a phase of early plough cultivation exposed in a trench dug through the bank at the Avebury School Site (Evans Reference Evans1972: 273). Middle Neolithic (3400–2900 cal BC) ceramics and lithics were recovered from the pre-henge soil at two locations under the south-eastern section of bank (Gray Reference Gray1935; Smith Reference Smith1965: 184). Another concentration of pottery and worked flint comes from within the Southern Inner Circle and is notable as the only such scatter known within the henge interior (we return to this below).

In the zone immediately surrounding the earthwork are other areas of Early and Middle Neolithic activity. These are evidenced by flint scatters, a pit containing plain bowl pottery, located close to the northern end of the West Kennet Avenue, and a tree-throw with similarly early ceramics associated with an early fourth-millennium BC radiocarbon date, located within 100m of the east entrance (Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Allen, Cleal, Snashall, Gunter, Roberts and Robinson2012). Other traces of fourth-millennium BC occupation are known from low ground and mid-slope locations within 1km of the henge: to the west in the Winterbourne valley, to the east along the foot of Avebury Down, and to the south on Waden Hill and the line of the West Kennet Avenue (Thomas Reference Thomas1955; Smith Reference Smith1965; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Limbrey, Mate and Mount1993: 151–53; Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Gillings, Allen, French, Cleal, Snashall and Pike2015). Regionally, evidence for settlement is strong; the archaeological record for the first quarter of the fourth millennium BC could indicate dispersed and small settlement foci, with greater aggregation following 3700 cal BC—notably on Windmill Hill (Whittle et al. Reference Whittle, Pollard and Grigson1999).

A key question is the degree, or otherwise, to which these early episodes of activity influenced the siting of the henge and its architecture. Were former episodes of significant (i.e. important historically, or by association) settlement and the people and lineages connected to them remembered by later inhabitants? Could the conscious retention of memory relating to such former activity explain the ontological shift from a place of routine practices to one that was deeply sacred, as indexed by the creation of the henge and its megalithic settings? We contend that some events and their material traces did matter in an historical sense and were referenced in the building of the megalithic settings.

The Southern Inner Circle

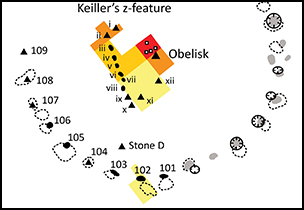

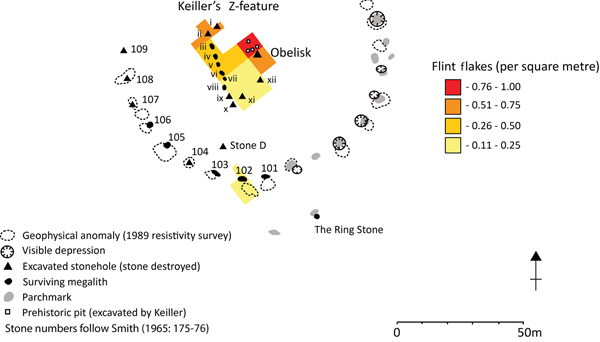

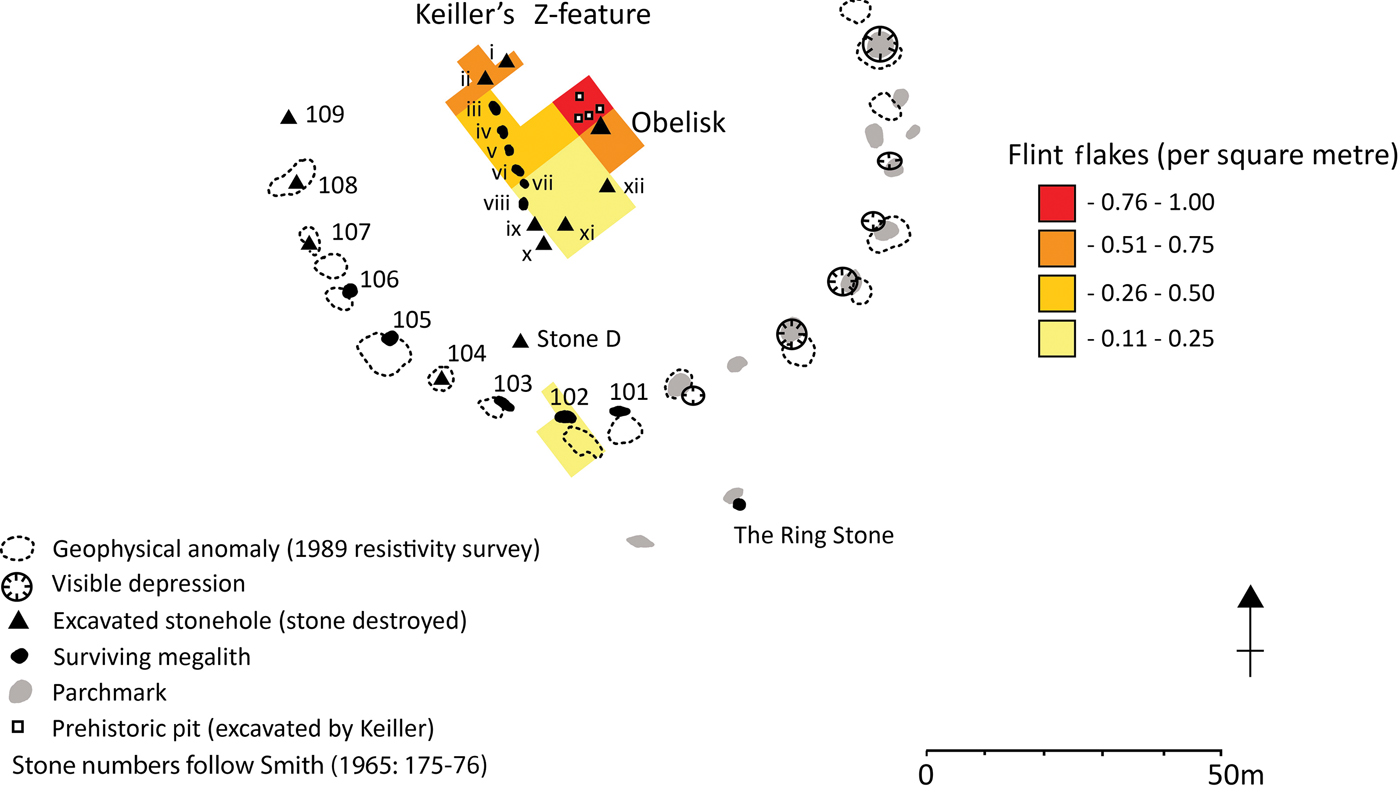

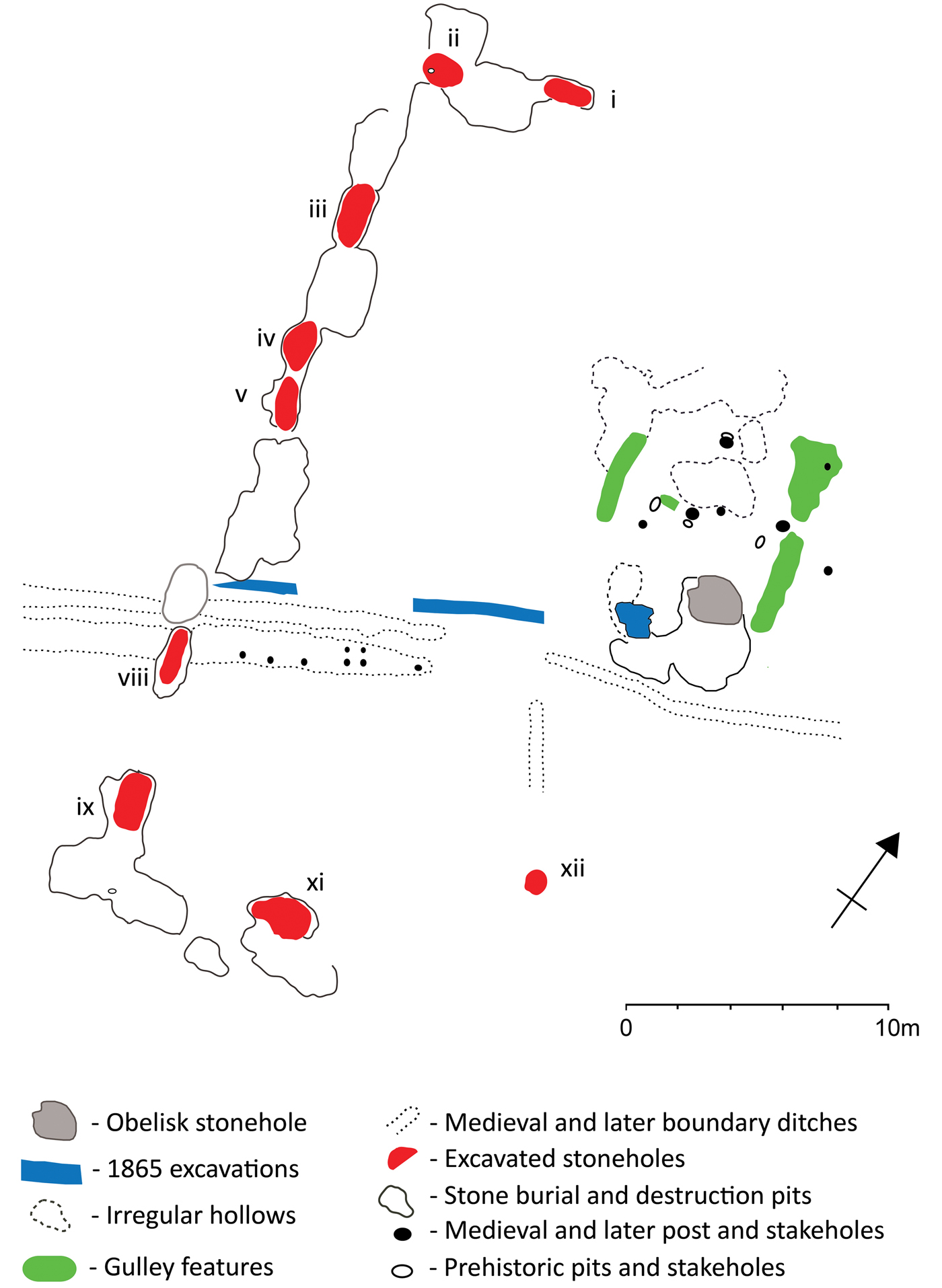

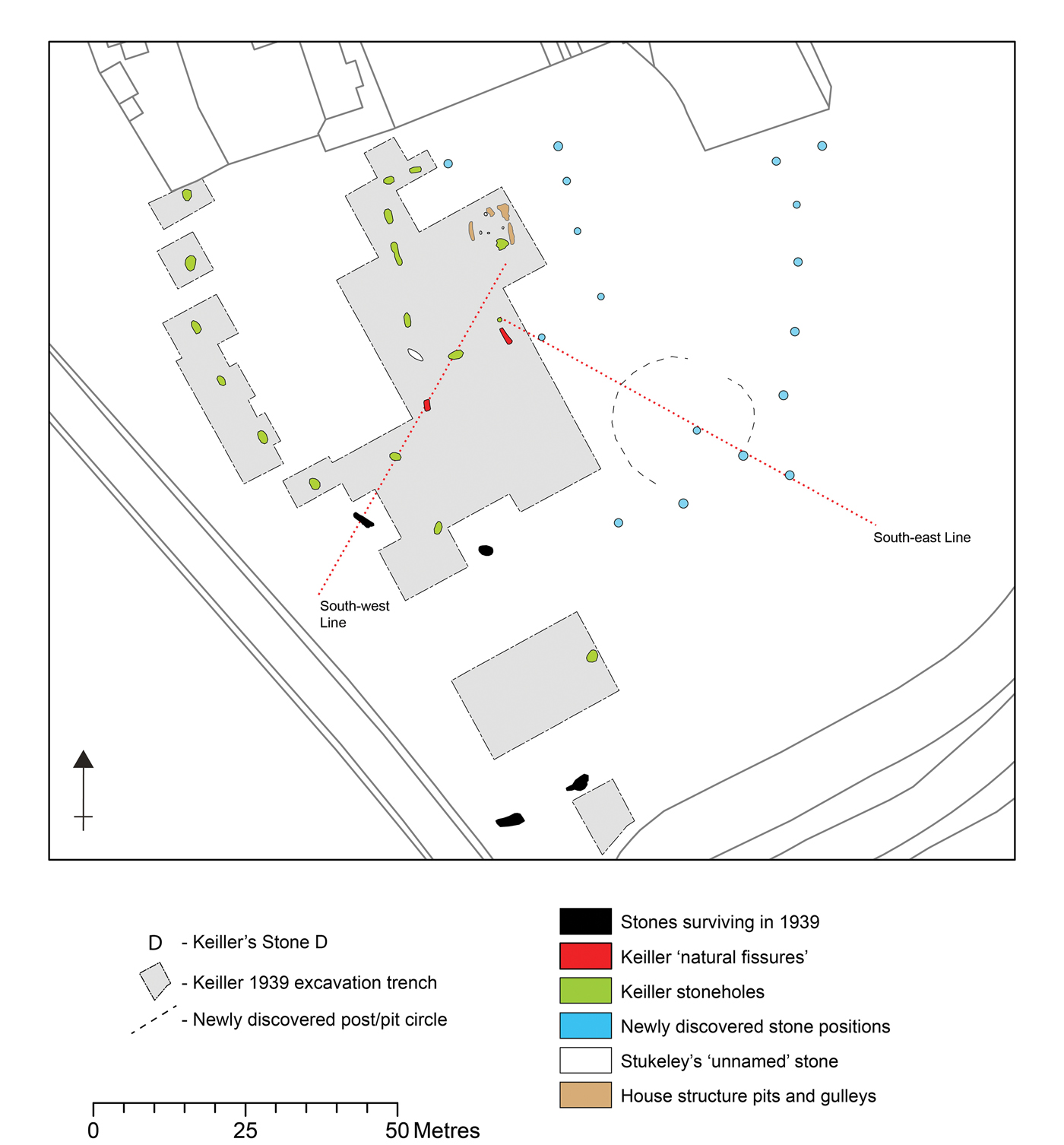

The Southern Inner Circle visible today is the product of a programme of excavation and reconstruction carried out by Alexander Keiller in 1939 (Smith Reference Smith1965). Utilising a 50ft (15.24m) grid of squares subdivided into 25ft (7.62m) quarters, Keiller's intention was to excavate areas not covered by village houses and gardens. The outbreak of the Second World War curtailed this operation, but not before a substantial area had been excavated, including the western arc and interior (Figure 2). Within the circle was the site of one of Avebury's largest stones, the Obelisk, which had been recorded and so-named by the eighteenth-century antiquary William Stukeley (Ucko et al. Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991). During excavation, Keiller discovered an unexpected 30.8m-long line of stoneholes that had formerly held megaliths to the west of the Obelisk. His excavations also unearthed a series of medieval stone burial pits (cut along the same line) that contained distinctive reddish sarsens, which were much smaller than other Avebury megaliths; the maximum dimensions of these stones ranged from 1.3–2.4m. Labelled by Keiller as the ‘Z-feature’, the presence of stoneholes perpendicular to the ends of the line (stones i and xi in Figure 2) hinted that these features may once have formed a rectangular setting (Smith Reference Smith1965: 198–201, fig. 69). Keiller's excavations also revealed the stonehole for a megalith (stone D) that did not appear to be part of either circle or the Z-feature, and a cluster of postholes, gullies and pits to the immediate north of the Obelisk. The Z-feature remains something of an enigma. Smith (Reference Smith1965: 250) suggested that if the excavated features were duplicated in reverse on the east side of the Obelisk, this megalithic component might resemble the stone kerb of an Early Neolithic long barrow.

Figure 2. The Southern Inner Circle showing recovered lithic densities (figure by the authors).

Critical re-evaluation of the Keiller excavation archive indicates that the excavated stoneholes were far too large for the Z-feature stones that Keiller re-erected into them. As a baseline, the excavated stoneholes of the main Southern Inner Circle ring (stones 102, 104, 105–109; Figure 2) range from 1.7–2.5m in maximum length, and hold stones standing 2.74–4.15m in height. With the exception of stonehole xii, which was genuinely intended for a small stone, the Z-feature stonehole dimensions fall comfortably within this range (Table 1). Thus, these stoneholes originally held much larger stones—equivalent in size to those making up the Southern Inner Circle. This explains the difficulty Keiller had in matching Z-feature stones to stoneholes, and his decision to raise these megaliths above the bases of ‘their’ stoneholes, by between 0.15 and 0.40m, when re-erecting them (Smith Reference Smith1965: 199).

Table 1. Dimensions of ‘Z-feature’ stoneholes. Southern Inner Circle (SIC) stoneholes have a mean maximum dimension of 2.07m and standard deviation of 0.27m

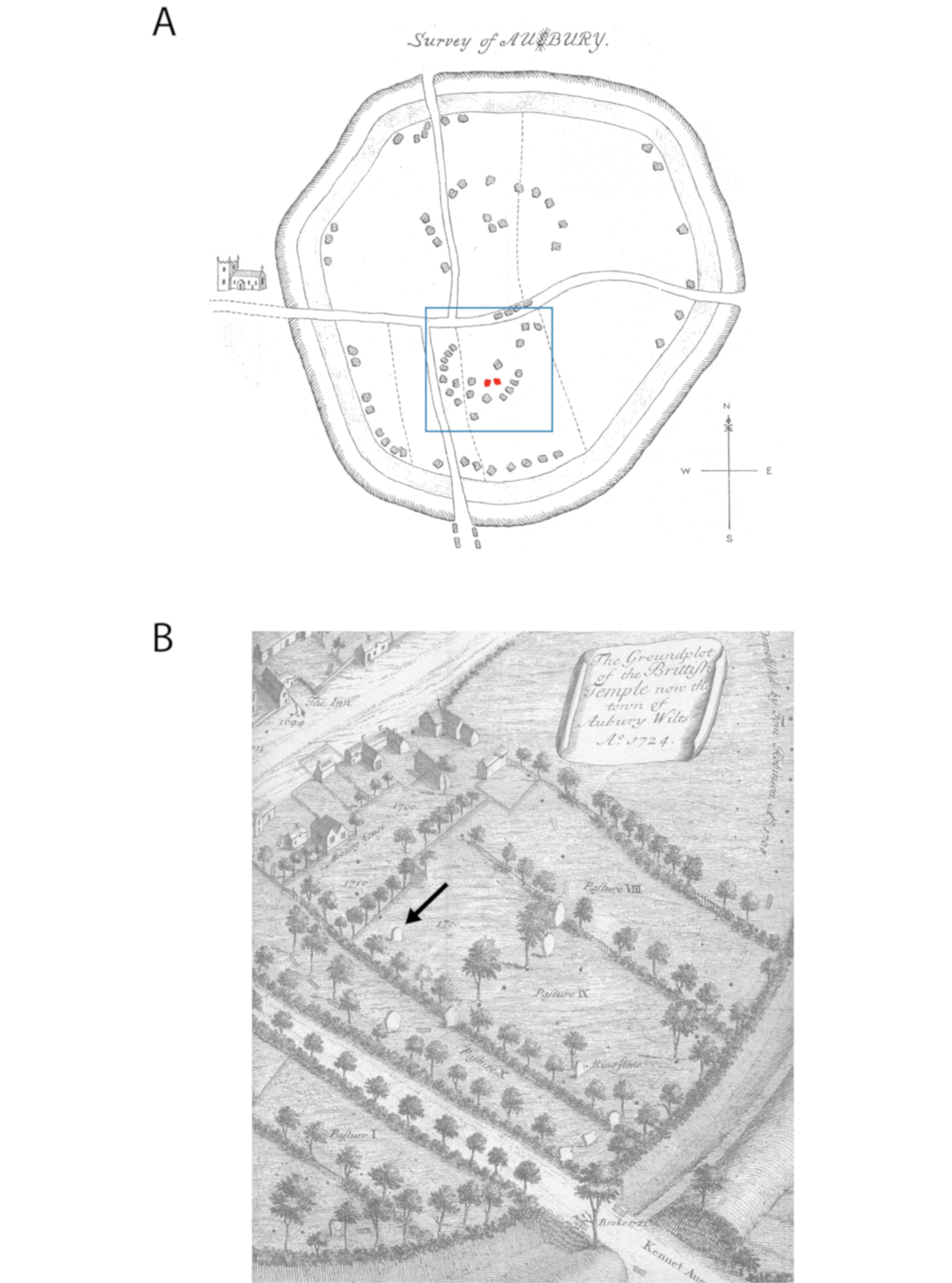

The antiquarian record

The earliest antiquarian records for the Southern Inner Circle comprise those made by John Aubrey and Walter Charleton in 1663, and William Stukeley's plan and written narrative compiled between 1719 and 1724. Ucko et al. (Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991) discussed the veracity of these records in forensic detail, revealing few definitive areas of agreement between them. Charleton's schematic plan, for example, depicts the Obelisk surrounded by a perfect circle of 13 megaliths. In contrast, Aubrey's plan A offers a more confused picture of the Southern Inner Circle's settings (Figure 3A). Aubrey mapped a portion of the Circle's arc, within which he recorded four large stone positions and two smaller stone symbols annotated with the letter ‘Z’. To the north-east are three further stones, and Aubrey makes no mention of the Obelisk. By the time Stukeley began recording the site 56 years later, a combination of entropy and active destruction had taken its toll. The Obelisk had fallen, and much of the complexity in layout hinted at by Aubrey was gone (Figure 3B). The presence of a single megalith standing in a somewhat anomalous location in the context of the Southern Inner Circle stones led Stukeley to propose the existence of a second concentric inner circle. Although Smith associated this anomalous stone with Keiller's ‘stone D’, Ucko et al. (Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991: 215–16) demonstrated that it corresponded instead to the location of Keiller's stones ix, x and xi. Despite their insistence that it was “a small stone” (Ucko et al. Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991: 215–16), however, Stukeley's drawings show a stone of substantial size, comparable in basal dimension to the main Southern Inner Circle stones—much larger than the stones of Keiller's Z-feature (Figure 4). In this location, Keiller's records show only a multi-lobate destruction pit, and his argument that this masked the stoneholes of three small Z-feature stones is questionable. On balance, the evidence suggests a more straightforward interpretation: this pit is related to a single, more substantial megalith.

Figure 3. A) Aubrey's ‘RUDE SKETCH’ (after Long Reference Long1858). Blue square denotes the Southern Inner Circle. The stones in red were originally drawn by Aubrey at half the size and marked with a ‘Z’ notation; B) Stukeley's Frontispiece (Stukeley Reference Stukeley1743)—the single stone that had survived to the early eighteenth century is indicated by the arrow; it was subsequently destroyed.

Figure 4. Stukeley's views of the Southern Inner Circle, with the surviving stone indicated: A) Stukeley 1743: tab XVI; B) Stukeley 1743: tab. XVII.

A Neolithic house

Within the Southern Inner Circle, Keiller excavated two features, both of which he labelled ‘Natural Fissure (?)’, alongside a cluster of gullies, pits and postholes to the immediate north of the Obelisk (Smith Reference Smith1965) (Figure 5). This cluster included a series of shallow hollows (maximum 2.7 × 1.8m), which he interpreted as medieval marl pits. Of greater significance are the parallel lengths of gulley, which define a structure approximately 6.9m wide and 6.8m long—although the southern extent has been affected by the destruction of the Obelisk. Running between these gullies was a line of three oval pits or postholes, with hints of a shallow slot linking the westernmost two (Figure 5). A fourth such pit was located on the approximate central axis to the north. While Keiller was content to assign a prehistoric date to these pits/postholes, he was confident that the gullies formed part of a much later, open-ended structure, presumably medieval in date. This, he surmised, had been opportunistically built against the fallen bulk of the Obelisk, using the latter as an ersatz rear wall. While Keiller toyed with the idea of the structure being a pigsty, his supervisor, W.E.V. Young, suggested that it may have been a cart shed. By the time that the fieldwork was formally published, these features had been reduced to the status of field boundary ditches (Smith Reference Smith1965: fig. 69).

Figure 5. The features excavated and interpreted by Keiller in 1939. The ‘1865 excavations’ refer to trenches dug in 1865 by A.C. Smith and W. Cunnington on behalf of the Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society (Smith Reference Smith1965: 183; Gillings & Pollard Reference Gillings and Pollard2004: 167–68) (figure by the authors).

The medieval date assigned to the pits and structure can be questioned, as no medieval pottery was found within the gullies, and only three sherds were recovered from one of the pits. This is surprising, given the high density of twelfth- to fourteenth-century pottery recorded in the excavation archive that was recovered from the overlying soil (up to 100 sherds per 25ft/7.62m square). The three sherds of medieval pottery from the pit are probably intrusive, as rabbit burrows were recorded in the vicinity. The pits may even be naturally formed features (e.g. tree-throw pits) of prehistoric date. It is the gulley-defined structure, however, that takes on particular significance, once Keiller's unsupported claim for a medieval origin is rejected. Several lines of evidence, we argue, suggest a prehistoric—and specifically Early Neolithic—date for the structure:

• Its axis is parallel to the excavated line of the Z-feature stoneholes, and it occupies the geometric centre of the Southern Inner Circle, which is located just north of the Obelisk.

• It is associated with a localised spread of Neolithic worked flint and pottery, which is otherwise rare in the interior of the monument.

• The plan of the structure bears a remarkable resemblance to those of smaller Early Neolithic houses from Britain and Ireland.

The spread of Neolithic artefactual material includes 346 pieces of worked flint from soil contexts in the area of the Southern Inner Circle, comprising 334 flakes, nine scrapers, a knife, a retouched flake and a polished axe. In addition, there are 138 worked flints from the Z-feature stoneholes and burial pits, from features associated with the Obelisk, and from the gullies. Amongst this material are two awls, a fabricator, a knife and a bifacially retouched flake. The associated debitage includes blades, narrow flakes and several thinning flakes. Such an assemblage is consistent with an Early Neolithic domestic site. Smith (Reference Smith1965: 226) records the retrieval of 30 sherds of Early Neolithic bowl and undecorated Peterborough Ware from stoneholes 104–106, i, iv, viii and ix. Relatively fresh sherds of Neolithic bowl were recovered from stonehole x. The distribution of this material is particularly striking, as the greatest concentration of worked flint is focused on the gulley-defined structure, with a lower-density ‘halo’ of approximately 20m radius around this (Figure 2). This distribution compares to the artefact spreads around the Early Neolithic buildings at Hazleton North and Ascott-under-Wychwood (Saville Reference Saville1990; Benson & Whittle Reference Benson and Whittle2007).

The most expedient interpretation is that this structure is a Neolithic house. Keiller was correct to interpret the gullies as wall trenches, although, unfortunately, descriptions of fills and sections are lacking. Three of the prehistoric pits sit within the interior, central and perpendicular to the gullies. Their small diameter probably indicates that they are postholes for an internal division. The fourth pit is located at the end of the structure in a central, gable-end position. Taken together, they form a plan that has close parallels with several small post- and trench-constructed houses of the thirty-eighth to early thirty-seventh centuries cal BC from mainland Britain and Ireland (Smyth Reference Smyth2014; Gibson Reference Gibson2017; Figure 6). At close to 7 × 7m, the Avebury structure falls comfortably within the size range (Gibson Reference Gibson2017: fig. 14). Close parallels include Fengate, Cambridgeshire, Ballintaggart 1 and 3, County Down, Newrath, County Kilkenny and Horton, Berkshire (Pryor Reference Pryor1974; Barclay et al. Reference Barclay, Chaffey and Manning2012; Smyth Reference Smyth2014). The larger structure at White Horse Stone, Kent (Booth et al. Reference Booth, Champion, Foreman, Garwood, Glass, Munby and Reynolds2011) was constructed within clear sight of a substantial sarsen spread, much as the Avebury building would have been (Gillings & Pollard Reference Gillings and Pollard2016). This would be the first such Early Neolithic house to be identified in Wessex (Barclay & Harris Reference Barclay, Harris, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017: 231).

Figure 6. The Early Neolithic house structure in the centre of the Southern Inner Circle and comparators (figure by the authors).

The 2017 survey

To investigate further the possible connection between the house and the excavated portion of the Z-feature, more data are required. Since Keiller's excavations, fieldwork in the Southern Inner Circle has been limited to an inconclusive geophysical survey in 1989, alongside more ad hoc mapping of parch marks (Ucko et al. Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991: 220). More recent surveys elsewhere at Avebury have proven the efficacy of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and soil-resistance survey for the detection of buried sarsens (e.g. Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008; Papworth Reference Papworth2012). Given the known presence of large (between 15 and 100 tonnes), buried sarsen stones at Avebury in close association with highly compacted stoneholes, it is surprising that no previous large-scale GPR surveys have been attempted. This is despite the success of GPR in detecting buried megaliths on the Beckhampton Avenue (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008: 64–66).

In April 2017, 0.567ha were surveyed to the east of the areas excavated by Keiller (Figure 1). Soil-resistance survey was carried out using twin-probe and square arrays, and this was complemented by GPR (a technical report on the survey can be found in the online supplementary material (OSM)). The resistance results are presented in Figure 7, and display several anomalies indicative of former megaliths. These take the form of discrete high-resistance anomalies (marking buried stones), moderately high responses (indicating either deeply buried stones or concentrations of stone debris) and lower-resistance features (destruction pits). Some of these had been previously identified as hollows by Keiller, and as generalised anomalies in the 1989 survey; several had not been identified at all. There are also south-east- to north-west- (and perpendicularly) aligned linear features corresponding to former boundaries—some of which are clearly visible in the field as earthworks—along with probable drainage features. Although not indicated on the interpretation plot, it is interesting to note that the interior of the Southern Inner Circle seems to be characterised by higher resistance. The south-west to north-east band of low resistance crossing the top third of the plot (Figure 7) probably reflects the complex sequence of medieval and post-medieval boundary ditches that criss-cross this area (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008: fig. 8.8).

Figure 7. Results of the soil-resistance survey carried out across the Southern Inner Circle with interpretation (for a location plan of the surveyed area, please see Figure 1) (figure by the authors).

Several clear anomalies are visible in the time-sliced GPR results, from the surface to a depth of 3.1m (Figure 8). An interpretation is presented in Figure 9, in which the level of re-inscription (i.e. over-drawing) can be read as a direct proxy for the persistence of the features with depth. Alongside linear medieval property boundaries and the general ‘noise’ adjacent to the modern gardens, 16 stone-related (1–16) and three other features (A–C) have been identified (see Figure 8 & Table 2). Feature A is adjacent to a modern boundary and manifests as a zone of high resistance, as well as an amorphous GPR anomaly; it probably derives from medieval and/or post-medieval building activity. Feature B is the edge of Keiller's 1939 excavation trench. Other anomalies, however, correspond to elements of Neolithic monumental architecture:

• Feature C: a sub-circular feature evident in the GPR data at a depth between 0.5 and 0.9m below the present surface. This appears to comprise a series of discrete, small circular anomalies that are probably postholes or pits.

Figure 8. Key GPR depth slices extracted at depths of 0.6–0.9m (A) and 1.2–1.6m (B). Plans of all of the extracted depth slices are provided in the technical report that has been included as online supplementary material (figure by the authors).

Figure 9. GPR interpretation combining anomalies identified in the sequential depth slices. In this figure, the level of re-inscription (i.e. over-drawing) acts as a direct proxy for the persistence of the features with depth (figure by the authors).

Table 2. Maximum dimensions and depths of buried sarsens.

Maximum dimension range for excavated Z-stones = 1.3–2.4m; maximum dimension range for Southern Inner Circle stones (allowing a metre for the unexposed base) = 3.74–5.15m

• Features 1–3 & 6: buried sarsens associated with the continuation of the Z-feature setting.

• Features 4–5: destruction pits or debris relating to the continuation of the Z-feature setting.

• Features 7–8, 11, 13 & 15: substantial, deeply buried sarsens of the Southern Inner Circle.

• Features 10 & 12: probable destruction pits (low resistance) and the compressed bases of megalithic stoneholes (GPR reflection) of the Southern Inner Circle.

• Features 9 & 16: probable destruction pits (low resistance) and compressed stone sockets (GPR reflection) relating to a pair of stones that form a linear alignment with anomalies 10 and 6.

• Feature 14: a spread of large fragments of sarsen or packing stones, resulting from the destruction of a substantial Southern Inner Circle sarsen.

• Feature ?: a possible stone position visible in the GPR data (depths 0.3–0.6m), but partially masked by debris relating to the modern boundary. Later boundaries tend to align on standing stones (see Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008: fig. 8.8).

Features 1–6 mirror the position of the excavated Z-feature stoneholes. Taken together, they form a 30 × 30m square megalithic setting that has been aligned to echo the principal axes of the house. The maximum dimensions of the GPR responses for the buried sarsens have been recorded as a proxy for the size of the buried stone, along with an estimate of the depth of the burial pit (Table 2). Anomalies 1–3 and 6 fall at the upper end of the size range for the smaller Z-stones, while 7, 8, 11, 13 and 15 are comparable in size to the main Southern Inner Circle megaliths. In all cases, the depth of burial is within the known range (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008: 25, tab. 9.1). Enough of this megalithic square had survived into the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries for both Aubrey and Stukeley to record its remnants. This suggests that the constituent megaliths had not been dismantled or reconfigured in prehistory. The excavated sarsens and the unusually large stoneholes encountered by Keiller indicate a mixture of larger and smaller stones. If set in alternate fashion, the result would form a contrast between the grey of the larger sarsens and the distinctive orange-red of the surviving Z-stones. The megalithic square is a highly unusual monument in its own right, the closest parallel being the ‘cove’ inside site IV at Mount Pleasant in Dorset (Wainwright Reference Wainwright1979: 28–31). At 36m2, however, the latter is considerably smaller.

Additional newly identified features include the sub-circular anomaly seemingly cut by the Southern Inner Circle (Figure 9: feature C) and two lines of stoneholes radiating from the centre. The former is reminiscent of a double concentric circular anomaly identified by Ucko et al. (Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991: pl. 67) in the Northern Inner Circle. Of the latter, the south-west running line comprises the Obelisk, stone xi, stonehole D, stone 103 of the Southern Inner Circle and a rectangular feature recorded by Keiller as a ‘natural fissure’ that may well be a stonehole. The south-east running line comprises stonehole xii and features 6, 9, 10 and 16. These radiating lines were wholly unexpected and invite comparison with the radial palisade fence at the nearby West Kennet Palisades (Figure 1) (Whittle Reference Whittle1997; Barber Reference Barber, Leary, Field and Campbell2013: 234–35, fig. 8.2). A Google Earth overlay file (in .kmz format) recording the locations of the megaliths revealed by the surveys has been included in the OSM.

The sequence reconsidered

Our preferred structural sequence for these newly identified features begins with the putative house, followed by the erection of the Obelisk and the square stone setting, and then the construction of the Southern Inner Circle and associated lines (Figure 10 & Table 3). The circular anomaly may pre-date the Southern Inner Circle, but direct dating evidence is currently lacking. By analogy with other Early Neolithic structures, the putative house should date to the second quarter of the fourth millennium BC. Sherds of Neolithic bowl and Peterborough Ware from stoneholes i, iv, viii and ix of the square setting are presumably residual (Smith Reference Smith1965: 226), although some appear quite fresh. Perhaps this and the Obelisk were constructed in the late fourth or early third millennium BC—a period that might also have witnessed the erection of the Cove stones inside the Northern Inner Circle (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008: 164–65). The radiating lines form a final megalithic phase. They each have a different origin point and both appear to have been carefully keyed into stones of the square and Southern Inner Circle, implying that the former were already in place. Smith (Reference Smith1965: 227) claimed there were weathered sherds of Beaker (in fact in an Early Bronze Age fabric) from beneath clay packing in a stakehole close to the edge of stonehole D, but the stakehole cannot be definitively related to the stonehole. Overall, we may be seeing activity spanning as much as 1500 years, from the Early Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age.

Figure 10. The newly revealed structural detail of the Southern Inner Circle (incorporates data (c) Crown Copyright/database right 2007; an Ordnance Survey/(EDINA) supplied service) (figure by the authors).

Table 3. Suggested phases of activity

Conclusion

If our new interpretation of the structure within the Southern Inner Circle as an Early Neolithic house is correct, the implications for understanding Avebury's origins are profound: the ancestry of one of Europe's great megalithic monuments can be traced back to the monumentalisation of a relatively modest dwelling. This supports Julian Thomas's (Reference Thomas2013: 294) view that fourth-millennium BC tombs and houses/halls played an active role in the creation and commemoration of foundational social groups. Eventually encased within the centre of the ‘deepest’ space of the henge, we hypothesise that it was the connections that this erstwhile building had with a significant, perhaps founder, lineage that led to it taking on a (mytho-)historic importance; and for the status of the site to move from the quotidian to the sacred. Avebury is not unique in this transformation from ‘mundane’ to monumental structure. The process is evidenced at several Neolithic monuments, such as in the construction of an earlier fourth-millennium BC chambered tomb over a former house at Hazleton North, Gloucestershire (Saville Reference Saville1990), and the later reworking of large free-standing buildings or halls into henges and timber and stone circles at Stenness, Orkney, and Coneybury, Wiltshire (Bradley Reference Bradley2003; Pollard Reference Pollard and Gibson2012; Richards Reference Richards2013). What marks Avebury as exceptional is the heightened significance and long-term resonance of this act of ontological transformation.

The Early Neolithic house at Avebury would have lasted perhaps only a generation or two; the collapsed daub walls would probably have left a visible earthwork that was subsequently afforded careful respect. Later acts of pit digging and artefact deposition highlight the long-term memory work that could attend the visible traces of Early Neolithic houses. Hey et al. (Reference Hey, Bell, Dennis and Robinson2016: 60), for example, highlight the deliberate digging and filling of later Neolithic pits containing Grooved Ware into the house/hall sites at Yarnton (Oxfordshire), White Horse Stone (Kent) and Littleour (Fife). A Middle Neolithic pit group was carefully dug between the traces of two early fourth-millennium BC houses at Llanfaethlu, Anglesey (Rees & Jones Reference Rees and Jones2015), while at Cat's Water, Fengate, Cambridgeshire, pits containing Peterborough Ware were dug along the edge of a centuries-old house (Pryor Reference Pryor2001: 48–49).

Since its unexpected discovery in 1939, the Z-feature at Avebury has presented an interpretative conundrum. Smith (Reference Smith1965: 251) came close to our preferred explanation when she proposed a link with Early Neolithic funerary architecture, in that the settings within the Southern Inner Circle deliberately echo elements of a long barrow, with the Obelisk representing a burial deposit. Instead of a tomb, however, the Z-feature settings can now be considered to commemorate a form of domestic architecture. The temporal currency of that commemorative reference was extended through further monumental elaboration. Neolithic house forms in Britain changed over time, from square and rectilinear to more oval and rounded later forms (Smyth Reference Smyth2014). It may be that an explicit link with concepts of the house and household was maintained at Avebury; the subsequent enclosure of the square megalithic setting and erstwhile house by the Southern Inner Circle may replicate—on a truly monumental scale—the square-in-circle format of later Neolithic houses and halls (Bradley Reference Bradley2003).

Finally, given the frequency with which Early Neolithic houses in Britain and Ireland occur in pairs or small groups, we might expect there to be more early houses at Avebury. Indeed, the Cove that sits in the centre of the Northern Inner Circle, amidst a confusing array of un-investigated stone settings, may be a good candidate for the site of a second foundational building.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Permission for the survey was kindly granted by Historic England and the National Trust. Rosamund Cleal facilitated access to the unpublished archives. Field assistance was provided by Jeremy Taylor and Dominic Barker.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.37