Despite growing interest in and research on populism, we have little knowledge about why voters support populist forces. Although there is little doubt that those who defend anti-immigration are in favour of populist radical right parties and those who endorse socioeconomic redistribution are inclined to vote for populist radical left parties (e.g. van Hauwaert and van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and van Kessel2018), much less clarity exists when it comes to identifying if the populist set of ideas plays an autonomous role in electoral behaviour. Do populist sentiments themselves explain the support for populist forces?

This article aims to answer this question not only by advancing a theory of populist voting that acknowledges the claims of previous research, but also by showing that populist attitudes among the population can explain varying support for populist actors in two otherwise similar countries: Chile, where support for populist actors is weak; and Greece, where support for populist actors is strong. In discussing these results, we aim to draw some lessons for those who are undertaking research on populism and to propose a general theory of populist voting that can be tested by further studies.

The article is structured as follows. We begin by clarifying our concept of populism and advancing our theory of populist voting. Next, we explain the Chilean and Greek cases and present our measures for populist supply. After this, we show measures of populist attitudes in both countries and the results of vote-choice models: for the 2013 presidential election in Chile and the January 2015 parliamentary elections in Greece. We close our article by discussing the relevance of our findings for the empirical study of populism.

Concept and theory

Our theory of populist voting draws from an ideational definition of populism. Rather than conceiving of populism as short-sighted economic policymaking (Dornbusch and Edwards Reference Dornbusch and Edwards1991) or a combination of charismatic leadership, movement organization and mass appeals (Barr Reference Barr2009; Weyland Reference Weyland2001), we follow others in defining it as a set of ideas – namely, ‘a discourse that sees politics in Manichaean terms as a struggle between the people, which is the embodiment of democratic virtue; and a corrupt establishment’ (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). Populist ideas may be present to a lesser or greater extent in a policy or organization – it is not a dichotomous phenomenon – but it is the presence of these ideas that allows us to characterize something as (more or less) populist.Footnote 1

Relying on this conceptual approach, scholars have started to develop techniques for measuring the supply side of populism by studying its presence in, for example, party manifestos (e.g. Rooduijn and Pauwels Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011), television programmes (e.g. Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007), newspaper articles (e.g. Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2014) and speeches of political actors (e.g. Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009). This scholarship is valuable because it helps demonstrate which leaders and parties actually employ populist ideas. Today we know that populist discourse is being used mostly by very specific electoral forces, such as populist radical right parties in Europe (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), radical populist leftist actors in Latin America (De la Torre and Arnson Reference De la Torre and Arnson2013) and more recently a small number of populist leftist forces in southern Europe such as SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left) in Greece (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis Reference Stavrakakis and Katsambekis2014).

However, this insight about the distinct qualities of populist ideas is only beginning to be applied to the study of populist demand. Until recently, scholars explained electoral support for populist forces not by considering the level of populist attitudes among voters, but by relying on proxy measures of populism such as support for restrictive immigration and asylum policies (Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008), employment sector and exposure to economic globalization (Oesch Reference Oesch2008) or levels of trust in the traditional political institutions of liberal democracy (Doyle Reference Doyle2011). These studies are helpful in that they identify why voters support particular subtypes of populism, especially radical right vs. radical left, and we agree that any study of populist voting that ignores the impact of the parties’ and the voters’ issue positions is incomplete. But the point of the ideational definition of populism is that there is an additional layer of ideas that politicians are expressing, one that is at least partly independent of traditional ideologies, and that voters may respond to these ideas.

To capture this ideational element at the level of voters, scholars have introduced the concept of populist attitudes (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012). Populist ideas at the mass level are called ‘attitudes’ because there is no claim that voters voice them, although there is tentative evidence elsewhere (plus our own everyday experience) suggesting that populist rhetoric is as much a mass-based phenomenon as an elite-level one. But we also refer to them as attitudes because of how they are measured and how they operate causally. A number of studies have begun to use public opinion surveys to assess the extent to which the populist set of ideas is widespread in society (besides the aforementioned studies, see Elchardus and Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Schulz et al. Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2018). Typically, these are inventories of populist-sounding statements capturing key components of the discourse: a Manichaean outlook, the virtue of ordinary citizens, and anti-elitism.

Recently, studies have found that these attitudes are correlated with voting for populist parties, at least in Europe. Studies of vote preference in the Netherlands (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017) and elsewhere in Western Europe (Van Hauwaert and van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and van Kessel2018) show that individuals with strong populist attitudes are more likely to vote for parties that are considered populist. What is less clear is why this is so. To begin with, if populist attitudes capture a set of beliefs that are always salient in voters’ minds, we might expect more populist voting; yet relatively few people with populist attitudes actually vote for populist forces. In addition, scholars remain unsure about the relationship of populist attitudes to traditional issue positions and ideologies. Their findings leave it unclear whether populist attitudes exist independently and compete with traditional issue positions and ideology, or if they have a more complementary relationship.

To bridge this theoretical gap, we argue that the special nature of populist attitudes as a discourse affects how they operate. First, they are subsidiary to, or conditional on the traditional ideological or issue positions of politicians and voters. Second, and more importantly, they are not always salient but must be activated by context.

The first argument reflects our earlier point that populist ideas should not be seen as a consistent ideology or a coherent programmatic position. Unlike classical ideologies such as conservatism, liberalism or socialism that represent conscious attempts to articulate comprehensive political programmes, populist discourses have limited programmatic scope. Thus, populism and other discourses such as elitism, nationalism or pluralism must be combined with political ideologies that provide needed programmatic content. This is one of the reasons why scholars using the ideational approach to populism often refer to it as a ‘thin-centred’ ideology, as opposed to a ‘thick’ or classical one (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). Statistically speaking, the political ideology moderates the effect of populist attitudes: once activated, populist attitudes strengthen support for favoured parties and candidates only when those politicians share the citizens’ issue positions.

The second part of the argument is that populist attitudes require a political context that makes them salient. The argument that certain attitudes are only active in certain contexts is an increasingly common one in the political psychology literature and has been made for Big Five personality traits (Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hibbing, Canache, Seligson and Anderson2010), authoritarian personality (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Stenner Reference Stenner2005) and framing (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Oxley and Clawson1997). The core notion is that certain attitudes constitute dispositions whose effective presence depends on external triggers; the less consciously articulated these ideas are, the more likely they are to have this quality and require activation. Because populist attitudes are just such a set of loosely articulated ideas, it makes sense to assume that they generally lie dormant and require activation.

We argue that the context which is most likely to activate populist attitudes is one in which there are widespread failures of democratic governance that can be attributed to intentional elite behaviour. While short-term policy failures such as economic recession can contribute to this context by highlighting weaknesses of the government, they are insufficient (Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015); policy failures must be attributed to elite collusion. This latter type of failure undermines the democratic legitimacy of the political class and makes populism an intelligible response to the community’s problems. This means that if ‘the establishment’ can be blamed for the obstruction to the achievement of the goals of ‘the people’, anger will become widespread across the population and this in turn can trigger the activation of populist attitudes (Rico et al. Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017). The condition is most clearly fulfilled when there is widespread corruption. An explosion of scandals showing systemic corruption reveals that an important section of the elite – if not the whole of it – has been acting fraudulently. Consequently, an important part of the population will feel that the moral foundations of the democratic order are under threat. But it may be fulfilled to a lesser degree by political unresponsiveness – that is, by a distancing of political elites from the policy concerns of their constituents. This distance paves the way for the alienation of citizens from established political actors, who are increasingly viewed as anything but the genuine representatives of ‘the people’. That said, the lack of intentionality makes it more difficult to frame unresponsiveness in populist terms.

This theory makes sense of some of the patterns that scholars have long noted in the historical study of populism (Conniff Reference Conniff1999; Kazin Reference Kazin1998) as well as in more contemporary research (Castanho Silva Reference Castanho Silva2019; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Kriesi and Pappas Reference Kriesi and Pappas2015). For example, these studies show that populist forces win control of government and stay in power more frequently in underdeveloped countries; in developed countries, populist forces instead express themselves as third-party movements and upstart parties, which sometimes persist but secure relatively smaller portions of the vote. The explanation is not that citizens in developing countries are more populist in their outlook, but that their populist predispositions are activated more frequently by a context characterized by political unresponsiveness and the recurrent disclosures of systemic corruption. Hence, in a country such as Venezuela in the 1990s, the context (one of a collusive two-party system involved in a series of corruption scandals coupled with economic mismanagement) combined with the supply of a strong populist leader (Hugo Chávez) produced massive electoral support for populist forces (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010). By contrast, in countries such as France, the Netherlands and the UK, a somewhat weaker context in recent years (economic slowdowns and migrant inflows in the midst of generally better democratic governance) has produced ‘third parties’ that alter the political landscape in important aspects but are unable to win absolute control of government.Footnote 2

Case selection

If our theory is correct, then we should find that voters’ populist attitudes are important predictors of their support for populist parties and movements, but that these attitudes interact with issue positions in explaining which specific parties the voters support. We should also find that, although populist attitudes are fairly widespread across countries, their overall impact in any country depends on context (e.g. corruption scandals and failures of representation).

In order to maximize variance on some of our key variables, we test these claims through a detailed analysis of vote choice in Chile and Greece. Although they are located in different world regions, these countries have several similarities that allow us to better control for extraneous factors that are sometimes mentioned in the literature on populism. In particular, they have nearly identical levels of economic development and similar levels of democratic experience (on the general impact of these factors, see Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012). Of course, there are important differences between the countries regarding other factors mentioned in the populism literature. In particular, while Chile is a presidential democracy, Greece is parliamentary; as of 2013, Chile’s legislative electoral rules were highly disproportional; and while Chile’s domestic politics are not highly constrained by supranational political institutions, Greece is a member of the European Union (on these factors, see Carter Reference Carter2005; Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart2016). However, in two of these instances the effect on populism goes in the opposite direction one would expect, in that it is the parliamentary democracy in the European country (Greece) that has witnessed populist parties winning control of the government. And as we will see, Chile’s legislative electoral rules did not entirely prevent the emergence of populist presidential candidates.

Where these countries are most different is in terms of the context for the activation of populist attitudes; the result has been a very different set of outcomes for populism in recent elections. In Chile, the context is much less favourable to the activation of populist attitudes. Compared to the rest of Latin America, the country is characterized by not only its political stability but also a successful process of economic modernization. Since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s authoritarian rule in 1989, Chile has been governed by established political parties and well-known political leaders; although outsiders with a populist discourse have occasionally been presidential candidates, they have never obtained a sizeable share of the vote. Moreover, the economy has been growing continuously and an impressive decline in poverty has taken place. Chile is also one of the least corrupt countries of the world; Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ranked Chile as 21st out of 177 countries in 2014, together with Uruguay. Not by chance, Patricio Navia and Ignacio Walker (Reference Navia and Walker2010) maintain that post-transition Chile has been immune to populism because of sound economic and social policies, strong institutions and a stable party system.

To the degree that the political context in Chile is at all favourable to the activation of populist attitudes, it seems more likely to assume the form of moderate unresponsiveness. Indeed, a number of studies indicate potential problems of political unresponsiveness in the country. Matías Bargsted and Nicolás Somma (Reference Bargsted and Somma2016) have recently demonstrated that a process of dealignment is taking place as there is a decreasing association between the political preferences of Chilean voters and their socioeconomic origin, religion and attitude towards the Pinochet regime – that is, the main issues that have structured the political system since the transition to democracy in 1989. Moreover, Juan Pablo Luna and David Altman (Reference Luna and Altman2011) have shown that the party system is frozen at the elite level and increasingly disconnected from civil society, while Ryan Carlin (Reference Carlin2014) finds that some Chileans distrust parties because of a lack of responsiveness. It is not a coincidence that the country has seen the emergence of massive waves of protests and the appearance of strong social movements in the last few years (Donoso and von Bülow Reference Donoso and von Bülow2017).

In contrast, Greece presents a context where our theory predicts populist attitudes to be highly active. To begin with, the country was heavily affected by the recession that hit Europe and other OECD countries starting in 2008. Because of a large fiscal deficit and low economic productivity, in 2010 the country was required by the European Commission, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – the so-called Troika – to undergo a series of painful fiscal adjustments. The adjustments resulted in a severe decline in economic output, widespread unemployment and a banking crisis. By itself this might not have activated populist attitudes, but already by the early 2000s there were significant discussions across Europe about the lack of democratic controls in these institutions and the European Union (EU) more generally (cf. Follesdal and Hix Reference Follesdal and Hix2006). In addition, within Greece the traditional parties were well known for patronage and corruption, and their fiscal mismanagement was a key contributor to the crisis (Pappas Reference Pappas2013). For several years, the country was ranked by Transparency International’s CPI as the most corrupt country in Western Europe, in 94th place globally as of 2012, roughly on a par with other countries in the Balkans.

Not surprisingly, Greeks blamed their economic crisis on the two political parties that had been governing the country since the restoration of democracy in 1974: the social democratic Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), and the centre-right New Democracy (Teperoglou et al. Reference Teperoglou, Freire, Andreadis and Leite Viegas2014). Not by chance, a number of new populist parties emerged on the left and the right that framed the crisis as an elite conspiracy against the Greek people.Footnote 3 The January 2015 election was called when the members of parliament, divided in their opinions about the Troika’s proposed bailout of the country, were unable to elect a president of the republic. As the results of the election made clear, most voters supported the anti-bailout, anti-Troika parties, and a new governing coalition was formed between two anti-bailout parties, radical left SYRIZA (led by Alexis Tsipras) and radical right Independent Greeks (led by Panos Kammenos). Although these parties represented different views on other ideological dimensions, both are regarded as highly populist.

To make clear, we do not think that the selection of these cases – and the obvious presence of strong populist parties in Greece or their relative weakness in Chile – prejudices the test in our favour. First, it remains to be seen just how populist these parties are in comparative context; neither party system has been systematically studied in previous attempts to measure populist discourse. Second, and more importantly, even if populist parties have a stronger presence in Greece during the time of our study, it has not been empirically demonstrated that the populist attitudes of their voters were connected to the parties’ electoral success.

The supply of populists

We start our analysis by clarifying which parties in each country can be considered populist and thus whether there was a ready supply of them. This allows us to discount any claims that the activation of populist attitudes (if we fail to find any) was merely the result of a lack of electoral options. We measure the level of populist discourse among the top presidential candidates and party leaders through a textual analysis of speeches and other documents for the 2013 presidential election (Chile) and the January 2015 parliamentary election (Greece). In Chile, we consider only candidates winning at least 5% of the vote in the first round. These include Michelle Bachelet, candidate of the centre-left New Majority coalition who won the election; Evelyn Matthei of the incumbent right-wing Alliance coalition; Marco Enríquez-Ominami, the leader of a new moderate-leftist coalition called PRO (Enríquez-Ominami is hereafter referred to, as in Chile, by his initials, MEO); and Franco Parisi, a right-wing independent. For added comparison, we also include Roxana Miranda of the radical-left Equality Party; although Miranda garnered a very small vote share (1%) that prevents us from including her in some of the models, she is a shantytown activist with a notoriously fiery rhetoric, and her discourse provides a helpful reference point.Footnote 4 In Greece, we consider the party leaders of the seven parliamentary parties: (1) Alexis Tsipras of SYRIZA; (2) Panos Kammenos of Independent Greeks (hereafter referred to by its Greek acronym ANEL); (3) Antonis Samaras of New Democracy (ND), the rightist party that led the incumbent government; (4) Evangelos Venizelos of PASOK, also in the incumbent government; (5) Stavros Theodorakis of POTAMI, a personalistic, centrist party in favour of austerity; (6) Dimitris Koutsoumbas of the Greek Communist Party (hereafter KKE); and (7) Nikolaos Mihaloliakos of Golden Dawn, an extreme-right party known for its violent tactics.

For every candidate in Chile except Miranda, the sample includes four texts: (1) their opening campaign speech (the one in which they announced their candidacy, always a written transcript); (2) their closing campaign speech (also a written transcript); (3) their participation in one of the televised presidential debates (the Anatel debate of 30–31 October 2013; only a video recording); and (4) their campaign platform (written text). For Miranda, her opening campaign speech was unavailable. Copies of all of these texts are available on request, except the Anatel debate, which we viewed in its entirety on YouTube.Footnote 5

For Greece, the sample of texts differs slightly. As in Chile, we score the opening and closing speeches of each party leader, but party platforms were unavailable for most of the parties because of the high frequency of elections, and televised debates were not held. Instead, we code the opening press conference of each candidate (like debates, a long, nationally broadcast event with relatively spontaneous responses) and an editorial that each of them prepared for major national newspapers. In retrospect, we felt the editorials were a poor substitute because they were much shorter than platforms (usually a few hundred words) and focused on just one or two issues. Thus, we report average scores with and without the editorial.

The technique we use for analysing these texts, known as holistic grading (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; White Reference White1985), asks coders to read the text in its entirety, then assign a score based on their overall impression of its form and content. It requires a coding rubric, a set of anchor texts that match each possible score, and a simple scale with no more values than there are distinguishable anchor texts. The technique is best suited for latent, diffuse attributes of the text such as tone, theme or the quality of an argument. Readers assign a score using an interval-level scale of 0=little or no populism, 1=moderate populism (specifically, a clear mention of the people in the populist sense, but with mention of other pluralist elements as well), and 2=strong populism (clear mention of the people, no countervailing pluralist elements). We use two readers and have both of them read each speech.Footnote 6 Final scores for each candidate are an average of each coder’s scores for all speeches in the set.

Average scores for each candidate and party are found in Table 1. The results for Chile are not surprising, showing at least two populist candidates, although both of these are on the left. MEO shows up as populist with a score of 0.9 – a moderate level – and Miranda shows up at a full 2.0. By way of comparison, the scores of MEO are similar to the scores given elsewhere to the campaign speeches of Néstor Kirchner in Argentina and Mauricio Funes in El Salvador, both of whom lost most traces of populism once they took office, while the scores of Miranda are similar to those of campaign speeches by Hugo Chávez and Rafael Correa, who needless to say did not become less populist after entering government. The remaining candidates in Chile show only slight traces of populism, if any. Parisi and Bachelet come in at 0.1 (a strong suggestion of populism appeared only in Bachelet’s campaign platform and Parisi’s closing campaign speech), while Matthei comes in last, without any traces of populism.

Table 1. Average Populist Discourse of Presidential Candidates and Party Leaders

The results for Greece largely conform to scholarly wisdom. Overall levels of populism are much higher than in Chile. The leaders of the outgoing coalition (Venizelos and Samaras of New Democracy) both have no or low levels of populism; the leader of POTAMI, a new centrist party formed by a political amateur, shows up with a low level of populism, as does the leader of Golden Dawn. Although Golden Dawn is sometimes considered as a populist party, its main characteristics are anti-immigrant attitudes and the engagement of its members in violent actions against immigrants (Papathanassopoulos et al. Reference Papathanassopoulos, Giannouli and Andreadis2017). As Yannis Stavrakakis et al. (Reference Stavrakakis, Andreadis and Katsambekis2017: 450) argue, it is not correct to classify Golden Dawn as a predominantly populist party because ‘references to the “people” within its discourse remains peripheral, ultimately reduced to a nativist and racist conception of the nation’ (see also Stavrakakis and Katsambekis Reference Stavrakakis and Katsambekis2014). In contrast, the KKE shows up as highly populist if we omit the scored editorials from the total; it is moderate otherwise. And the leaders of the two parties that went on to govern, Tsipras (SYRIZA) and Kammenos (ANEL), show up as highly populist, especially if we omit the editorials. This latter finding confirms the argument of scholars that the coalition of SYRIZA and ANEL, two otherwise ideologically dissimilar parties, can be explained by their populist opposition to austerity (Aslanidis and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Aslanidis and Rovira Kaltwasser2016).

Measuring (latent) populist demand

Thus, in both Chile and Greece populist candidates and parties were available at the time of our study (although in Chile these were limited to left-populists – a difference that will affect our vote choice analysis). The question raised by our theory is whether populist attitudes were widespread and correlated with other attitudes and behaviour, especially a preference for these populist parties. In Greece, we expect underlying attitudes and their connection to vote choice to both be strong; in Chile, we also expect underlying attitudes to be strong, but for this demand to be latent and disconnected from vote choice for all but a handful of voters.

We measure the voters’ underlying populist attitudes through two surveys. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Survey in Chile is a nationally representative face-to-face survey conducted at the homes of respondents roughly at the time of the 2013 president election: 1,800 people were surveyed with probability proportional to population (ppt), using a sample that was stratified by region and zone (urban/rural); the resulting margin of error is 2.5% with 95% confidence, and the design effect is 1.15. The survey was in the field between 17 August and 9 October 2013 and was carried out by the firm STATCOM.

The Hellenic Voter Study for the Greek parliamentary elections of January 2015 (Andreadis et al. Reference Andreadis, Kartsounidou and Chatzimallis2015) is a mixed-mode survey conducted by the Laboratory of Applied Political Research at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The recruitment process lasted from 12 June until 16 July 2015 using RDD (random digit dialling). The respondents were asked to provide their email address in order to participate in a web survey conducted by Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The 1,008 completed cases were collected either as web-based self-administered questionnaires or using computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI). The web was the main data collection mode of the survey and the telephone interview was used as an auxiliary method for respondents who lacked internet access and/or an email account (Andreadis et al. Reference Andreadis, Kartsounidou and Chatzimallis2015).

To measure populist attitudes, in each survey we rely on an inventory developed by Agnes Akkerman and others (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012), and which we translated into Spanish and Greek. Descriptive statistics for these items along with a comparison of means between Chile and Greece are displayed in Table 2. In the online Appendix, we show that these individual statements cluster together reliably, much as in previous surveys. Since we use Likert type items, we follow Cees Van der Eijk and Jonathan Rose (Reference Van der Eijk and Rose2015) and apply Weighted Mokken Scale Analysis in R (Andreadis Reference Andreadis2017) to the inventory; technical results can be found in the online Appendix (Table A.3). The analysis shows that all six populist items are associated with a single underlying dimension. The scalability coefficients for all items both in Chile and in Greece are larger than 0.30 and the homogeneity coefficients H are 0.39 in Chile and 0.44 in Greece.Footnote 7 Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha for the populist statements is 0.70 in Chile and 0.74 in Greece. The descriptive statistics of the index created as the mean value of the six populist attitudes items are displayed in the last line of Table 2. Importantly, mean values of each item are nearly identical across countries, showing that underlying populist attitudes are similarly high; although some differences are statistically significant at the p<0.05 level or greater, absolute differences are no more than 0.5 on a scale of 1 to 5.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Populist Attitudes Items and Comparison of Means

Sources: The United Nations Development Programme Survey in Chile and the 2015 Hellenic National Election Voter Study.

Note: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p <0.001.

The activation of populist attitudes

To determine whether these attitudes are activated and combining with other ideological positions and attitudes in ways that our theory predicts, we perform a series of vote choice analyses for each country using the UNDP and Hellenic survey data sets. The dependent variable in all of these models is the presidential candidate (Chile) or political party (Greece) that the respondent preferred. The numbers in favour of each candidate or party are reported in Table 3, together with their actual percentage of the vote from the first round.

Table 3. Candidate and Party Preferences in UNDP and Hellenic Surveys (questions P107, Q5LH-a, Q1ELNES)

Sources: The United Nations Development Programme Survey in Chile and the 2015 Hellenic National Election Voter Study.

We use multinomial logit to model the likelihood of voting for each of these candidates and parties (Dow and Endersby Reference Dow and Endersby2004; Kropko Reference Kropko2008).Footnote 8 Descriptive statistics for all independent variables are found in the online Appendix (Table A.4). The main predictor of interest in all models is the populist attitudes index (Populist attitudes). The models also include a standard array of controls for vote choice models, which explore many of the issues favoured in current studies of populist demand. In Chile, we use support for Matthei as the baseline because she was selected by a sizeable minority of respondents, and because she was clearly the least populist; in Greece, we use New Democracy as the baseline for the same reasons, thus allowing us to compare coefficients in the Chilean and Greek models more directly. Thus, coefficients indicate how each independent variable increases the probability of voting for another candidate versus Matthei or a party besides New Democracy.

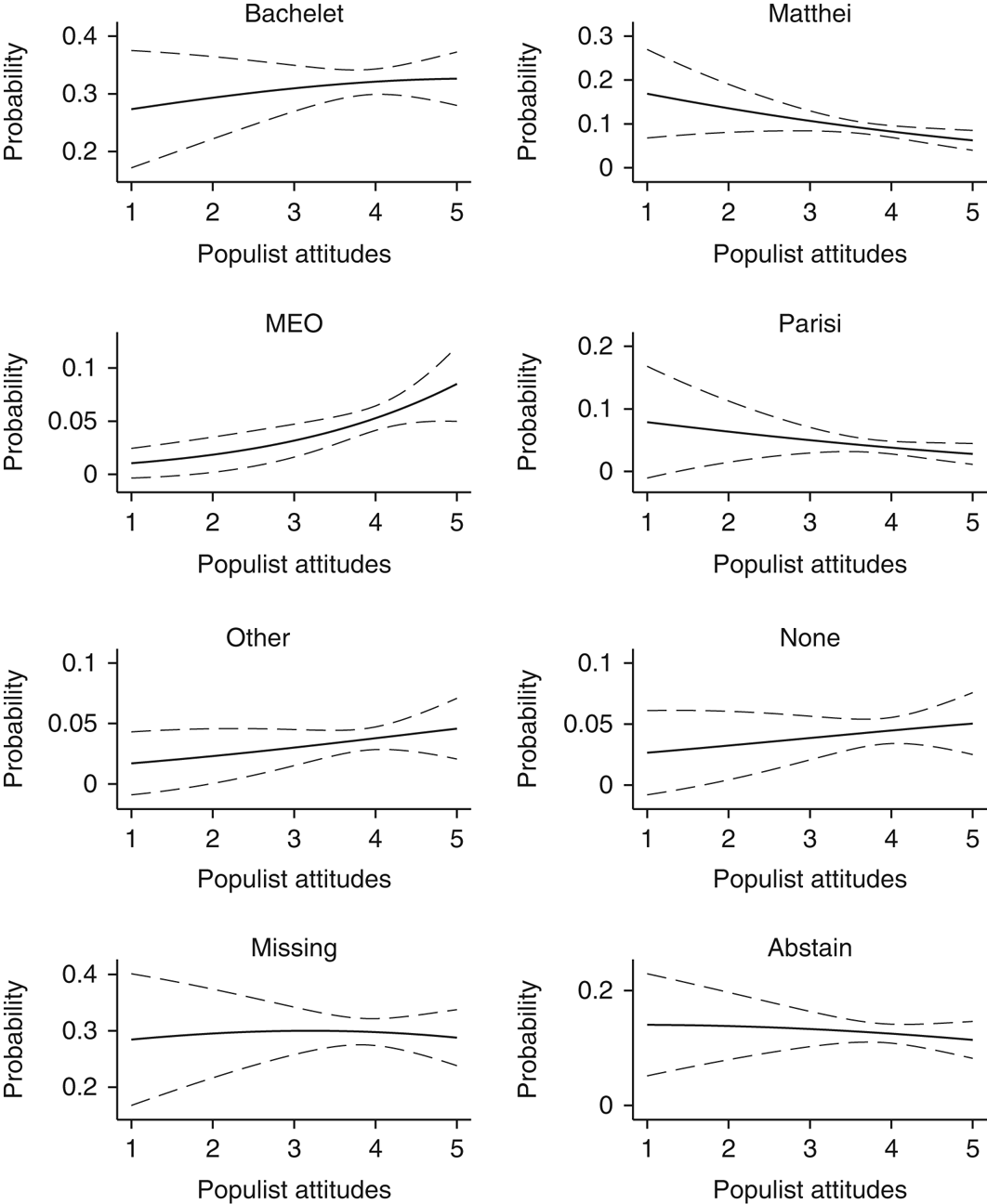

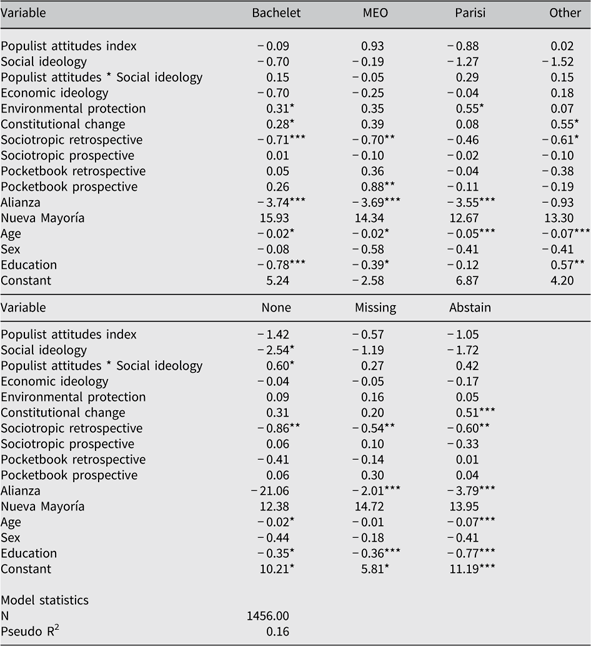

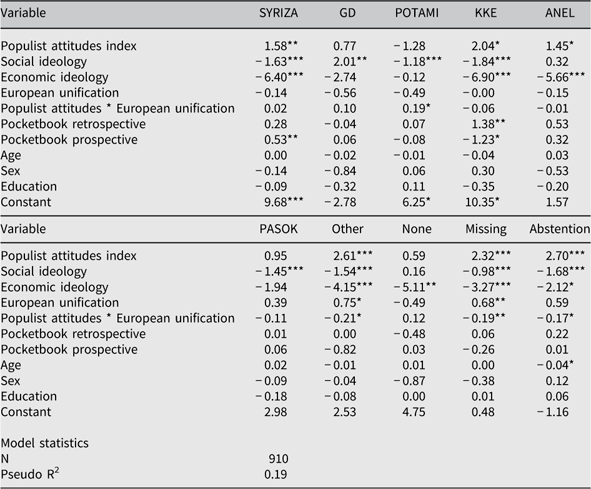

We start with unconditional models for each country. These include our key independent variable (populist attitudes) without any interaction terms. Our question here is whether populist attitudes correlate with vote choice for particular candidates after controlling for all other independent variables. Results are in Tables 4 and 5. Because the logit coefficients can be difficult to interpret, we also produce a series of plots showing the predicted probabilities of voting at different levels of populist attitudes, where the point of comparison is with all other options and not just the baseline. These are found in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 4. Unconditional Model of Candidate Preference in Chile (multinomial logit; baseline category is Matthei)

Note: * p <0.05; ** p <0.01; *** p<0.001.

Table 5. Unconditional Model of Party Preference in Greece (multinomial logit; baseline category is New Democracy)

Notes: GD=Golden Dawn. * p<0.05; ** p <0.01; *** p<0.001.

Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities of Chilean Voting, by Populist Attitudes (95% confidence interval)

Figure 2. Predicted Probabilities of Greek Voting, by Populist Attitudes (95% confidence interval)

Looking at both countries, we see that populist attitudes are important predictors of the vote for the most (or least) populist candidates. In Chile, although Bachelet and MEO both have statistically significant coefficients for populist attitudes in comparison with Matthei (see Table 4), the predicted probabilities make clear that only MEO’s vote and, in a negative direction, that of Matthei have any real connection to populism. Bachelet’s vote leans populist (as does a vote for other candidates), and Parisi leans away, but the effects for these are not statistically significant. For MEO and Matthei, the effect is moderately large. If we consider a range of 2.5–5.0 on the scale of populist attitudes (about two standard deviations above and below the mean), the predicted shift in voting probability for MEO or Matthei is about 5 percentage points. Considering that MEO received 11% of the vote in the actual election, this is an important effect.

In contrast, the effect in Greece represents a much more important predictor of the overall vote. Populist attitudes are a clear predictor in the positive direction for SYRIZA and in the negative for New Democracy, POTAMI and PASOK. Voters for the KKE, ANEL and Golden Dawn also lean populist, but the effect in this model is not statistically significant. The effects of populism for the first two parties are quite large: a shift of 2.5–5.0 in populist attitudes is associated with a 30 percentage point shift in the vote for SYRIZA and a (negative) shift of 25 percentage points for New Democracy. These are sizeable differences that would have had a strong impact on the outcome of the election.

Although these results go some way towards confirming our argument by showing that populist attitudes were more active in Greece than in Chile, they do not yet show us how populist attitudes interact with ideology or related issue positions to explain the vote for particular populist parties. That is, while our theory argues that populist attitudes matter for political behaviour once they are activated, it does not argue that they override traditional ideology or issue positions; they are moderated by those positions, working their effects only among ideological proximate groups, depending on the candidate. This interaction should better explain the support for specific populist parties and candidates, especially when (as is more clearly the case in Greece) a variety of populists are available.

To see this effect in Chile, we examine the interaction of populist attitudes with social ideology. Although mainstream political parties have sometimes had difficulties taking into account this programmatic dimension (Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011; Morgan and Meléndez Reference Morgan and Meléndez2017), voters in Chile have become increasingly divided over social issues such as divorce and abortion (Blofield Reference Blofield2006). In our unconditional model of the 2013 survey, these issues were better predictors of vote choice than economic ideology. Thus, we should find that the effect of populist attitudes for both MEO and Matthei (the only candidates for whom populist attitudes mattered) is moderated by social ideology. Specifically, in the case of MEO, we would expect populist attitudes to have their positive effect primarily among voters with socially left positions; MEO was the most socially leftist of all the candidates, and unless voters with active populist attitudes also had social left views, they would not have voted for him.Footnote 9 In contrast, we expect the negative effect of populist attitudes on Matthei’s support to be concentrated among voters who were socially right; Matthei was the most socially right of any of the candidates, and voters on the social left would not have voted for her anyway. Hence, populist attitudes would tend to make socially right voters turn from Matthei to other options. Note that ‘other options’ included abstention or casting a blank/null ballot, to the degree that populist attitudes alienated voters from candidates that would have otherwise been proximate (the reverse being true for MEO). For the other candidates, populist attitudes had no discernible association to begin with, and we do not expect any interactive effect either.

Table 6 and Figure 3 show results from the interactive model and a set of marginal effects plots. Note that these plots are no longer predicted probabilities, but the added effect of populist attitudes on vote probabilities given the impact of social ideological positions. Thus, at ranges of the interaction variable where populism has a positive added effect, the confidence interval will be above the zero-effect line. For MEO in particular, we expect the confidence interval to be above the zero line on the left, indicating that the added positive effect of populist attitudes is concentrated among voters with socially left positions. In contrast, for Matthei we expect to find a curve below the zero-effect line on the right; that said, because the effect of populist attitudes in the unconditional model was smaller for Matthei, we might not see a discernible effect here. Finally, because left-populist voters had an option (MEO) but right-populist voters lacked any, for the options of ‘abstain’ and ‘none’ we might see a marginal effect above the zero-effect line on the right and below the zero-effect line on the left.

Table 6. Model of Candidate Preference in Chile, Populism * Social Ideology (multinomial logit; baseline category is Matthei)

Notes: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Figure 3. Marginal Effects Plots of Chilean Voting, Populism * Social Ideology (95% confidence interval)

We find almost all of these expected effects. For MEO, populism has a positive marginal effect on vote intention that becomes statistically significant only for respondents with socially leftist positions. For Matthei, the negative marginal impact of populist attitudes is visible on the social right (and turns out to be statistically significant). For the ‘abstain’ and ‘none’ options, the marginal effect of populist attitudes just misses statistical significance, but in both cases is in the expected directions. For all other candidates, the effect of populist attitudes does not vary with social ideology and remains close to nil (the confidence interval overlaps the zero line).

In Greece, the set of issues over which populists competed was more complex. To begin with, as in Chile, voters could choose among populists based on their social positions – the socially conservative ANEL and the nationalist (and questionably populist) Golden Dawn, versus socially liberal or moderate populists such as the KKE and SYRIZA. In addition, voters could choose among parties based on their attitudes towards austerity and separation from the EU and eurozone. Moderate parties such as SYRIZA supported staying in the EU and renegotiating austerity measures and IMF/ECB conditionality, while more radical parties such as the KKE sought full exit from the EU as the best way of dealing with creditor institutions; ANEL was somewhere in between. We capture the latter effect by interacting populist attitudes with European unification, and the former effect with social ideology.

To deal with these complex effects, we proceed in two stages. As we did with Chile, we start by rerunning the multinomial logit model for Greece with a simple interaction effect, in this case between populist attitudes and European integration. We then rerun a model with a multiple interaction between populist attitudes, European unification and social ideology.

Consider first the simple interaction between populist attitudes and European integration. Results are in Table 7 and Figure 4, the latter again being a series of marginal effects plots. They confirm most of our expectations. For SYRIZA, the positive effect of populist attitudes is concentrated among voters who are in favour of the EU, as indicated by the confidence interval above the zero-effect line on the right. In contrast, for the ‘Other’ option as well as abstention, the positive effect of populist attitudes is concentrated among voters who are against the EU (confidence interval above the zero-effect line on the left). ‘Other’ primarily captures the vote for ANTARSYA and KKE-ML, two communist parties which we were unable to include in our discourse analysis but which are generally regarded as extremist and anti-establishment; and abstention essentially represents a decision to vote against the highly popular but pro-EU SYRIZA. Finally, the results for other, clearly non-populist parties (New Democracy, PASOK and POTAMI) are as expected: populist attitudes have a general negative effect regardless of attitudes towards European integration, with one exception: the impact of populism on voting for PASOK is not significant on the anti-EU side. This is probably related to the fact that PASOK has been the party with the stronger pro-EU policies since the beginning of the financial crisis; as a result, citizens with anti-EU attitudes are not expected to vote for PASOK, no matter what their preferences are on other issues.

Table 7. Model of Party Preference in Greece for Populism * European Unification (multinomial logit; baseline category is New Democracy)

Notes: * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p< 0.001.

Figure 4. Marginal Effects Plots of Greek Voting, Populism * European Unification (95% confidence interval)

There are two negative findings for our theory. First, the interaction effect for the KKE is in the expected direction but not statistically significant. Although upwards on the left, suggesting that the effect of populist attitudes for KKE voters is also associated with negative attitudes towards the EU, its confidence interval fails to clear the zero-effect line. We suspect that, given the initially small effect of populism for the KKE and the modest number of respondents in the survey, this is the best we can do. Despite its high populism score as a party, the effect of populist attitudes among its voters is only modest.

Second, the simple interaction still produces an insignificant result for ANEL: the confidence interval overlaps the zero-effect line, and the trendline is basically flat. Fortunately, the multiple interaction with social ideology allows us to address this lingering concern. Because the results of this triple interaction are difficult to depict even graphically, in Figure 5 we focus on just two parties, ANEL and, for a reference point, SYRIZA. Full results of the model, as well as graphs for other parties, are found in the online Appendix. The array of graphs describes the average marginal impact of populist attitudes at different levels of social ideology (vertically, across the rows of graphs) and European integration horizontally (across the x-axis).

Figure 5. Marginal Effects Plots of Greek Voting, Populism * European Unification * Social Ideology (SYRIZA and ANEL only)

As can be seen, for SYRIZA the strong connection between populist attitudes and (positive) attitudes towards European integration is still visible, but somewhat concentrated among voters towards the middle of the social ideological scale. The slope of the line is towards the upper right and is furthest from the zero reference line in the three middle graphs. This means that SYRIZA (although a radical left-wing party) was able to earn votes from a number of citizens with stances on social issues that were different from the official position of the party. We suspect this is because social issues were less salient in this campaign than relations with the EU and populism, and among the parties taking a strong positive stance on European unification, only SYRIZA is a populist party. However, we now also have a clear finding for ANEL. There is a strong connection between populist attitudes and (negative) attitudes towards European integration, but only among voters with a strong right ideology; the marginal effects line slopes towards the left (low support for European integration) and clears the zero reference line only in the last row of graphs. Thus, the impact of populist attitudes for ANEL (and even SYRIZA) becomes clearer once we take into account the multiple issues affecting this election.

In summary, we find that populist attitudes are a modest predictor of the vote in Chile and a very strong predictor of the vote in Greece. While populist attitudes are widespread in both countries, they are highly active in determining vote choice in only one of them. This holds true even after controlling for a host of other factors, including issue positions, partisan identity, economic assessments and voter demographics. Importantly, the effect of populist attitudes in both countries interacts in sensible ways with other, equally important ideological positions and attitudes. In Chile, where voters could justifiably take a more positive view of economic performance over the past few decades, the low levels of active populist attitudes generally have a modest impact that is moderated by social issues. In Greece, in contrast, populist attitudes are not only much more active but are generally associated with a desire to remain in the EU and with moderate positions on social issues, a fact that seems to explain much of SYRIZA’s success. The intersection of these attitudes especially helps explain the split in voters between SYRIZA (attracting citizens with left or moderate social ideology) and ANEL (a radical right party). The only party we are not able to explain very well is the KKE, where effects are in the expected direction but not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Although an increasing number of scholars are undertaking research on populism, there is little knowledge about the role that populist ideas play at the individual level. In other words, we are not certain if mass support for populist forces is driven by populist sentiments. This article begins to fill this gap by offering a theory of populist voting and analysing the extent to which populist attitudes explain voting behaviour. Relying on survey data for recent elections in Chile and Greece, we show that populist sentiments not only exist but are positively associated with voting for populist forces: a candidate with a moderately populist discourse in the case of Chile (Marco Enríquez-Ominami) and at least three parties in Greece that have been employing the populist set of ideas (SYRIZA, ANEL and the KKE). Furthermore, these attitudes are associated with negative voting for several other candidates or parties, including the runner-up in Chile (Matthei) and the two in the previous Greek government (New Democracy, PASOK).

This finding supports our theory of populist voting. Populist attitudes are as widespread in Chile as in Greece, yet these attitudes are relatively dormant in the former and active in the latter. We think this shows that political context must be taken into account. The 2013 presidential election in Chile took place in a fairly responsive political system, not to mention a more positive economic scenario. By contrast, the January 2015 parliamentary elections in Greece were marked by major failures of economic policy in a context of relatively high corruption and state weakness. We also find telling indicators of the activation of populist attitudes at the individual level. Not only are these attitudes important predictors of the vote for populist parties, but they interact in predictable ways with ideological and issue positions that have traditionally been used to predict populist party support. This confirms that multiple levels and types of ideas affect the willingness of citizens to vote for populists.

We admit that further tests of this theory are necessary. To begin with, our contribution has focused on only two countries, and future studies could employ the techniques used here to advance large-N comparisons, including cases from not only Western Europe and Latin America, but also Eastern Europe, North America and Scandinavia. By including a larger set of cases from various world regions, we could not only replicate our individual-level findings, but better analyse the extent to which contextual factors at the country level (economic performance, corruption levels, etc.) explain the activation vis-à-vis latency of populist attitudes. Additional surveys would also allow us to test more explicitly for the mediating relationship we have postulated for populist attitudes. In this study, we were unable to incorporate such a test because of the lack of exogenous predictors in the survey data set (e.g. experienced corruption or ideological distances from parties), but we think this kind of test is crucial to provide a more persuasive account of the role that populist attitudes play. Future research could also show what voters with high levels of populist attitudes look like and what socializing forces generate their attitudes. For instance, it would be interesting to examine if populist attitudes have an impact on positive and negative identification with political parties, since this would permit us to see if those who support populist forces are against established political parties or not (e.g. Mélendez and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2017).

Another important avenue for future research is experimental. Tests of causality that rely on observational data, especially quantitative analysis, are problematic. In addition to future survey-based research for gauging causal mediation, it would be desirable to show these causal connections through lab-based or online experiments. Experimental work has already been done examining the links between populist framing and electoral support, as well as the ability of populist attitudes to mediate this causal relationship (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Van Der Brug and De Vreese2013; Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers, Bos and de Vreese2016), but so far these have only been done in single-country studies. Future tests could also consider how contextual issues enhance the impact of populist rhetoric and how consistent these effects are across national contexts.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.23

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments and advice from participants in multiple conferences. Moreover, we would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Any remaining errors are ours alone. Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser acknowledges support from the Chilean National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FONDECYT project 1180020) and the Center for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES, CONICYT/FONDAP/15130009).