INTRODUCTION

The Kunstkammer, or cabinet of wonder, of Schloss Ambras in Austria is one of the iconic cabinets of curiosities for twenty-first-century tourists.Footnote 1 Located on a hill just a few minutes away from the city of Innsbruck, the secluded castle gives visitors the illusion of being transported in time to see an early modern collection as it once appeared. Upon entering the gates of the lower court, one turns left to purchase tickets and then proceeds through several halls of armory to reach the gallery of rare wonders, filled with portraits of monstrous creatures, stuffed sharks, masterpieces of ivory turning, rhinoceros horns, and bronze statuettes of horses. The collection is located almost at the same site as four hundred years ago, in one of the buildings of the lower court and not in the main castle. It is still adjacent to the Rüstkammer (armory), whose collections of armor, shields, helmets, and barding for horses take up much more square footage than the curiosities. But no illusion can be perfect. Unlike four hundred years ago, the building complex of the lower court no longer houses a stable with living horses. Would it have made a difference to visitors four hundred years ago that instead of a ticket office and gift shop, their visit to the Kunstkammer was framed by the experience of seeing and smelling large numbers of elegant horses? It is this question that this article aims to answer.

Although it is now largely forgotten, stables were an important site of collecting in the early modern period, especially in Central Europe, where many princely Kunstkammern, Rüstkammern, painting galleries, or libraries were located on the upper stories of active stables. This article argues that the architectural characteristics of stables conditioned how such collectibles and horses were presented, treated, and viewed. It offers an exercise in spatial thinking, exploring how aristocratic collectors amassed and exhibited an impressive amount of rarities in a gallery space in the vicinity of the stables, where a large number of horses was showcased in a similar manner. Much of the recent literature on the architecture of cabinets of curiosities has tended to focus on the intimate and private collections of early modern naturalists such as Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), Olaeus Worm, or Ferrante Imperato.Footnote 2 This article instead explores collections that were much larger. The outsized dimensions of stables offered a very different viewing experience from the better-studied, small-scale setting of the naturalist's cabinet.Footnote 3

The past thirty years have seen a veritable outpouring of books on early modern cabinets of curiosities.Footnote 4 In all probability, more pages have been written on early modern collecting since 1985 than during the centuries between 1500 and 1700. Most twenty-first-century specialists may know much more about curiosities than the average visitor to a collection during the Renaissance. Consequently, there may be a risk for historians to overinterpret how much early modern curiosi cared about particular objects. Ever since Walter Benjamin, art historians have often focused on the aura of a singular painting or work of art, studying how viewers reacted to its particular details.Footnote 5 Similarly, historians of science have tended to examine the preternatural qualities of the peculiar objects of curiosity culture.Footnote 6 Scholars working in this paradigm have often associated the things found in a cabinet of curiosity, or in any other early modern collection, with a special type of response from viewers, whose admiration was inspired by focused and prolonged attention to the unique characteristics of these marvels. This article offers a less studied, alternative way of seeing curiosities and works of art. It proposes that curiosities above stables, as well as the horses in the stables, could also evoke wonder in viewers by their large quantity and the overall impression they projected. Kunstkammern in stables did not necessarily encourage viewers to engage closely with the strange features of a select number of objects.Footnote 7

This article does not present a single case study but rather sketches out its argument by considering several stables across a time period that ranges from the mid-sixteenth to the early eighteenth century. My aim is to prove that elegant horses and luxurious curiosities were often showcased in the same buildings throughout Central Europe, even if this wide geographic coverage results in the inevitable, occasional loss of particular details. I reconstruct early modern ways of seeing from the brief remarks collectors and viewers left about objects that they did not study with devoted attention. Consequently, I cannot rely on a single, rich source that offers the opportunity for sustained, micro-historical analysis. To ensure cohesion, the article looks at German-speaking courts, with a special focus on Munich, Dresden, Wolfenbüttel, Vienna, and Innsbruck, which were closely connected to each other throughout the period.Footnote 8 Sovereigns in these towns frequently relied on the same suppliers to acquire their exotic curiosities and horses, and stable masters moved freely between these courts. The world of princely Kunstkammern relied on a small, tight-knit network of people, which ensured that developments in one town strongly influenced the collecting practices in others.

The term curiosity is notoriously vague. This article will further stretch the term's semantic field by arguing that it could also encompass elegant horses. Since the rest of the article makes an argument to reformulate this concept, I will define curiosity here broadly as any type of collectible that served as a status symbol and could evoke admiration in viewers. Such a parsimonious definition is powerful enough to explain many features of early modern curiosity culture and does not exclude books, paintings, or living animals. Most of my examples scrutinize the experiences of high-ranking aristocrats who were intimately familiar with the world of collecting and horse riding, ranging from the ennobled merchant family of the Fuggers to the Habsburg emperors. As I show, members of the nobility had a reasonably common understanding of how to exhibit and appreciate the curiosities and horses under the roof of a stable.

The first section provides the evidence that many early modern Kunstkammern were actually located above stables. The second section shows that early modern curiosi often relied on similar terms to describe horses and curiosities and acquired both through the same agents, implying that these two categories overlapped to a significant degree both in discourse and practice. The third section turns toward examining the architecture of stables, and offers a hypothesis that stables conditioned how curiosities could be displayed and how visitors viewed them in the period. I argue that many curiosi visited stables and Kunstkammern to admire an assemblage of objects, and did not necessarily engage in detail with the curious features of particular objects. It is the nature of this attention that comes under further scrutiny in the fourth section, where I examine how collectors and travelers looked at large numbers of horses, and perceived them as representatives of a breed or a race.

CURIOSITIES, ARMOR, BOOKS, AND PAINTINGS

Throughout the early modern period, horses and collections were the representational tools of princes who wanted to project valor. Horses were the most conspicuous element of the festive display of power at every European court throughout the period, and every member of the nobility was expected to undergo a thorough training in the art of riding. A large number of elegant, perfectly shaped, and fast horses, wearing stunning armor and fashionable saddles, could impress aristocratic viewers like few other things.Footnote 9 Such horses performed in ballets, ran races, and rode in triumphant entries, but they spent most of their days in a stable where visitors could see them off duty.Footnote 10 Yet while historians have produced excellent studies on paradise birds or armadillos, only a few studies by Pia Cuneo and others have explored how noble horses, the most prized animal in the period, were treated as marvelous creatures, not unlike ostrich eggs, the paintings of Van Dyck, or a finely carved spoon bedecked with gems.Footnote 11 In princely stables, horses became objectified under the gaze of viewers and lost their status as sentient individuals, becoming status symbols instead.Footnote 12

It is not a coincidence that the earliest Kunstkammern were often located in the stables where the sovereign's priceless horses were kept. In Munich, the Kunstkammer of Duke Albrecht V (1528–79), arguably the earliest such collection north of the Alps, was established on the third floor of the newly built royal stables in the 1560s, a stone's throw from what would become the Residenz, the main palatial complex. The Kunstkammer was a major element of Albrecht V's project of turning Munich into a site of courtly display, part of a larger campaign of centralizing power in Bavaria, a country until then riven by aristocratic factions.Footnote 13 This was not Albrecht's only attempt at using collections and festivities for these purposes. His establishment of the Antiquarium, a large hall filled with sculpture, within the Residenz also served the purpose of projecting power, and so did his decision to have the whole of Bavaria mapped.Footnote 14

The horses at the bottom of the Kunstkammer were also an essential component of the courtly festivities that celebrated the ruler. They signaled status, wealth, and a discerning mind, not unlike curiosities.Footnote 15 When the ennobled curiosity merchant Philip Hainhofer (1578–1647) visited Munich in 1611, he noted that the then reigning Duke Maximilian's “greatest recreation and expenses are a beautiful horse and the beautiful stud, falconry, trinkets and gems, art and painting, and the art of turning,” including horses and other objects of wonder in the same sentence. Hainhofer was not the only person to mention horses, artwork, and curiosities as evidence for the refined passions of a prince. The Munich-based Samuel Quiccheberg, author of the first treatise of museology, explained in his Inscriptiones (Inscriptions) that horse-related paraphernalia (e.g., armor, caparisons, or saddles) were highly relevant objects if one wanted to start a new collection, and he promised to write a separate volume on Rüstkammern, which he never completed.Footnote 16

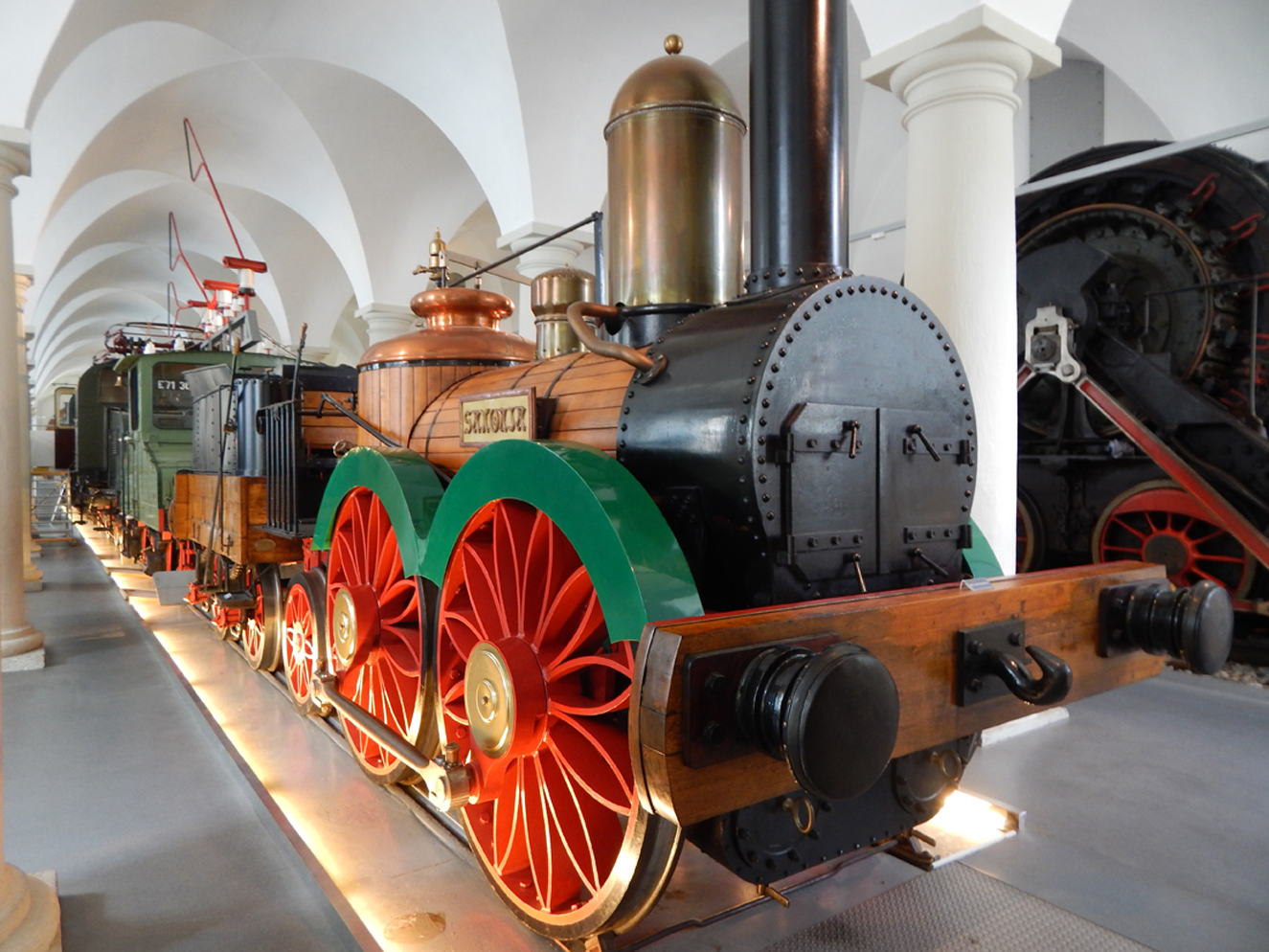

In Dresden, the rise of stables and collections occurred in the same time period. Finished in 1587, the majestic courtly stables at the Neumarkt doubled as a multipurpose Rüstkammer, becoming a major nonreligious sight for travelers for centuries. In Martin Zeiler's (1589–1661) Itinerarium Germaniae (Itinerary of Germany, 1632), a seventeenth-century travel guide that relied heavily on earlier sources, the Marstall (princely stable) was the first secular building to receive mention in the entry on the city. Zeiler claimed that it was a “stately and very spacious building,” a must-see because of the horses and curious works of craftsmanship inside. Downstairs, the stalls were decorated with “metallic lionheads with a spigot, from which water spouted out,” and numerous “Spanish, Neapolitan, Hungarian, Pomeranian, Frisian, Danish, and Turkish horses, and, to sum up, each landrace was standing by its own race, and each breed [razza] next to the other.”Footnote 17 Zeiler also explained in detail that the upper stories held arms, armor, saddles, and sledges from various countries, as well as ceremonial decorations and exotica from Turkish and Indian lands that could be used in tournaments and ballets (fig. 1).Footnote 18 As in Munich, the Dresden stables served as one of the main sites for the exhibition of courtly might, located near, but not inside, the main palace, with a long, exquisitely painted arcade connecting the two. There was also a separate Kunstkammer, established in 1560 and located inside the palace, but it served primarily the private interests of Elector August (1526–86).Footnote 19 Its holdings were mostly scientific instruments and tools, the personal pastime of the elector.Footnote 20 It was only in the seventeenth century that this Kunstkammer developed into a more universal and representational collection of curiosities that was available for public viewing. By this point, many of the Kunstkammer's holdings came to bear strong similarities to the naturalia and artificialia exhibited above the horses in the stables.Footnote 21

Figure 1. The former Dresden royal stables, nowadays the Dresden Transport Museum. Photo: Dániel Margócsy.

Libraries were another major site of collecting in the early modern period, and they could serve to enhance the reputation of local rulers. Consequently, books were stored in buildings that served as stables for keeping elegant and noble horses. Consider Wolfenbüttel, whose heyday was during the reign of Duke August the Younger (1579–1666). Duke August visited the sights of Munich and the Rüstkammer and stables of Dresden during his youth; after the end of the Thirty Years’ War, he decided to build a Marstall that housed his renowned collection of books, globes, and mathematical instruments, the foundational collection of the Herzog August Bibliothek today, together with his horses.Footnote 22 This building was not inside the duke's palace but located right next to it. The stables were downstairs and the library upstairs for roughly half a century, with a Rüstkammer added up in the attic. As the local poet Sigmund von Birken noted in praise of the Marstall,

Books, horses, and armor celebrated in unison the duke, who united the heroic qualities of Bellerophon and Apollo in one person, as Birken's poem also claimed.

Paintings were another type of curiosity. Vienna saw a similar growth of interest in horses and other collectibles in the very same decade when the rulers in Munich and Dresden became seriously invested in them. Erected around 1560, the Viennese Stallburg originally housed the royal stables downstairs and a Rüstkammer on its upper floors, a pattern familiar from Dresden. As Renate Holzschuh-Hofer has emphasized, the stables, with their expensive and luxurious imported Spanish horses, were no less of a Kunstkammer than the armory above them.Footnote 24 A century later, however, as fashions in collecting changed, the Stallburg's upper floors underwent a transformation. They came to accommodate the art collection formerly in possession of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm (1614–62), which contained many paintings, sculptures, and exotica.Footnote 25 This gallery remained in the Stallburg until the 1770s, when the paintings were moved into the Belvedere. The Spanish riding school's horses are still in the same building today. And if paintings were housed where the horses slept, the Habsburg emperors’ books were stored where the animals exercised. The building of the Hofbibliothek, the court library, had a riding house and riding school on its ground floor, with the books one flight up.Footnote 26

The list of stables that also housed collections could go on. From the 1590s onward, the Kassel stables housed the exquisite collection of famous astronomical and mathematical instruments of William IV of Hesse-Kassel; the Stuttgart Marstall, built around the same time, had a Rüstkammer above.Footnote 27 Outside Germany, the Grande Galerie of the old Louvre also held the renowned riding academy of Antoine de Pluvinel.Footnote 28 Even at the dawn of the eighteenth century, when the Renaissance unity of natural curiosities, artificialia, paintings, and scientific instruments began to break down and give way to specialization, the architectural spaces of stables sometimes managed to keep these various objects and activities together. In Berlin, the fashionable old electoral stables on the Breite Straße held a Rüstkammer upstairs with a variety of rarities on view.Footnote 29 Visitors flocked to see it. As the Hungarian traveler Count Mihály Bethlen wrote in 1692, he was particularly impressed by the “sixteen wooden horses, uniformly decorated,” which served as props for the spectacular bards that the horses downstairs would wear on special occasions.Footnote 30 When Johann Theodor Jablonski began planning the new Berlin Academy of Sciences in the early spring of 1700, he immediately thought that the best location for this institution would be the elector's new stables on the Dorotheenstraße.Footnote 31 The stables also came to house an astronomical observatory, an anatomical theater, a coin cabinet, a library, and the Akademie der Künste, with its collections, which all fell victim to a fire that broke out downstairs among the horses in 1743.Footnote 32 As royal stables went out of fashion with the coming of motorized vehicles in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, these buildings would ironically become converted into art galleries, again. In 1885, for example, the Reithaus of Marburg University, built originally in the 1730s by Charles Louis du Ry, was converted into a museum of plaster casts. Even these days, the former Quirinale stables of Rome house major temporary exhibitions.Footnote 33 It is no accident that twentieth- and twenty-first-century curators find converted stables so congenial as exhibition spaces. The modern concept of the museum inherits many features from the Renaissance stable.

THE CURIOUS HORSE

Plagiarized from the German philosopher Christian Wolff's (1679–1754) influential Vollstaendiges Mathematisches Lexicon (Complete mathematical dictionary, 1734), the entry on the Marstall in Zedler's Universal-Lexicon (Universal dictionary, 1732–50) attests that, by the early eighteenth century, it was generally accepted that stables held collections upstairs: “A courtly stable (lat. equile principis) is a splendid building at royal and princely courts. . . . On the upper floor, one will have a gallery or different halls next to each other where one can safely keep many precious textiles, valuable platters, and many other things necessary for solemn occasions.”Footnote 34 And if stables housed a variety of luxurious items from armory to books and paintings upstairs, the horses downstairs could also be considered similar curiosities. For many collectors and travelers, the building of the stable formed a unit where the horses and the exhibits upstairs were equally worthy of attention. As the scholarship on pageants and courtly life has acknowledged, the language of curiosity culture infused the discourse on horses to a considerable degree.Footnote 35 Zedler himself used a strikingly similar conceptual framework for discussing cabinets and stables: to judge a collection of curiosities, one needed to contemplate “1) the rarity and expense, 2) the number, 3) the order or arrangement of the objects,” while the function of the Marstall was to display one or more “rows of expensive horses, placed together.”Footnote 36 In both cases, the emphasis was on the expense, the quantity, and the pleasant spatial ordering of the objects. Throughout his entry on stables, Zedler pointed out how stables across Germanic lands made conscious efforts to display a large number of costly horses in the most magnificent manner. Writing about the stables of the Counts Wallenstein in Prague, for instance, Zedler recounted that each horse was made to stand by a marble pillar to create a pleasing effect. The stalls were made of polished marble, with “life-size paintings of wonderfully beautiful horses hanging above.”Footnote 37 What mattered was the overall impression of the assemblage of stone, living animals, and painted artwork. Zedler's entry did not waste a single word on the qualities of an individual horse in the stables.

If the same terms were employed in the conversation about stables and cabinets, the same name would be used to describe admirers of horses and curiosities. Early modern horse aficionados called themselves Liebhaber in German, the equivalent of the English term curioso.Footnote 38 In the late sixteenth century, the Bavarian aristocrat and humanist merchant Marx Fugger (1529–97) addressed his Von der Gestüterey (On studs, 1584) to “all lovers of riding” (“Allen Liebhabern der Reutterey”).Footnote 39 Similarly, when the Wolfenbüttel stable master Georg Engelhard Löhneysen (1552–1622) published his monumental Della cavalleria (On cavalry, 1609) on breeding and riding horses, he specified in the title that his book was aimed at “all lovers of these arts” (“Liebhabern solcher Künste”), implying that hippology was an art.Footnote 40

Half a century later, the wandering stable master and renowned author Georg Simon Winter von Adlersflügel (1634–1701) celebrated Emperor Leopold I, whose reign saw the installation of the painting gallery over the Stallburg, as “one of the most powerful protectors and noblest lover of all arts, especially of cavalry.”Footnote 41 If the lovers of all matters equestrian were Liebhaber, the horses themselves had to be rare and curious wonders. Consider, for instance, the stallion so renowned for its “extraordinary jumps” at the Viennese Stallburg in the years around 1720 that it was portrayed by the horse painter Johann Georg de Hamilton (1672–1737).Footnote 42 He bore the name Curioso. Curioso was not unique in being a curiosity: the category extended to all noble and exceptional horses, though some breeds were more curious than others. When the English hippological expert William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle (1593–1676), decided to praise Spanish horses, he wrote that “there is no Horse so curiously shaped, all over from Head to Croup: He is the most beautiful that can be.”Footnote 43 Curious horses were necessarily wonderful, too. When comparing the horse to other animals, for instance, Löhneysen pronounced in favor of the horse because of this quality, asking rhetorically if “one can find an animal that is more wonderful . . . than the horse.”Footnote 44 Such amazing horses were of course a rarity. As Aldrovandi claimed, “A horse can be called the most perfect of all if it has all the signs of probity, yet one can never find one like that, or only on the rarest occasions.”Footnote 45 As in the case of curiosities, the choicest horse was also the rarest.

It was not only in printed discourse that horses and curiosities were treated in a similar manner. The surviving, rather limited, evidence on the management of stables and the horse trade also reveals clear parallels in how horses and curiosities were handled in practice. As precious commodities, horses could be inventoried together with the other curiosities in the same building. In Dresden, the collections’ official inventories usually carefully separated the various objects that were held at different locations. Yet, when the new stable master Hanns Georg von Ponickau (1540–1613) took charge of the stables in 1595, the inventory of new and missing items listed together “the bay Liechteinstein horse, still good,” the “book bound in red silk satin, with gold coverings, about horse medicine,” “the gilt marble drinking vessel,” and “two small rapiers.”Footnote 46 Even more importantly, curious horses originated in the same lands where curiosities abounded. As Aldrovandi emphasized, prized horses were rare and those rarities tended to come from those faraway lands that also provided other exotica. At Central European courts, Arabian, Turkish, and Barb horses were held in the highest regard, together with Spanish and Italian breeds, the two lands that also served as ports for commodities arriving from afar.Footnote 47 The preference for such horses was partly based on the widespread Hippocratic idea that horses from warm and dry climates were better and faster because the environment shaped their temperament, and partly because they were a rare sight that looked markedly different from the common stock of Germanic lands. In Vienna, the Spanish riding school was called “Spanish” because its horses came from there, and the famous Lipizzaner breed originated from these imported animals.Footnote 48

Rarity and exoticism were the reasons why the Habsburgs collected all sorts of objects from the New World, such as the famous headdress of Montezuma that was exhibited in Schloss Ambras in the sixteenth century right next to a good number of rare Spanish horses.Footnote 49 This is why the logistics of the curiosity trade overlapped with the business of animals. Throughout this period, the same people were responsible for importing horses and other types of exotica to Central European lands: aristocratic ambassadors and merchants of the highest rank who had the status connections and ample funds to acquire luxurious rarities. When it came to the Habsburg emperor, the main supplier of both horses and curiosities was the ambassador to Spain.Footnote 50 In the 1560s, this role was occupied by Count Adam von Dietrichstein (1527–90), and then, from the 1570s to the early 1600s, by Hans Khevenhüller (1538–1606).Footnote 51 Upon his arrival in Spain, Dietrichstein immediately attempted to start sending regular shipments of horses back to Austria, together with various assortments of curiosities.Footnote 52 Archduke Ferdinand II (1529–95), owner of Ambras, expected to receive eight to ten horses every two years.Footnote 53

Khevenhüller had a similar, shared interest in horses and curiosities. Throughout his decades in Spain he spared no cost or effort to acquire bezoars, wild turkeys, lions, jewelry, and horses for the Austrian Habsburgs.Footnote 54 Khevenhüller's interest in horses predated his arrival in the Iberian Peninsula. When he traveled to Augsburg for the Reichstag, he reveled in the sight of the eight hundred horses of August, elector of Saxony, a number that certainly impressed.Footnote 55 Once in Madrid, the ambassador quickly struck up warm relations with Don Juan d'Austria (1545–78), whose renowned stables were immortalized in Jan van der Straet's (1523–1605) print series of the Equile Ioannis Austriaci (The stables of Don Juan d'Austria); he also began to acquire horses in large numbers. In 1575, he sent seventeen Spanish horses to Vienna through Cartageña.Footnote 56 In 1579, he acquired an especially impressive white horse, valued at eight hundred ducatons, which he immediately sent back home to the emperor in the company of another horse. To get these animals to Vienna, Khevenhüller relied on his stable masters Garcia Ferre and Petro Fuerte, who also took care of the transportation of parrots and other exotic animals across Europe. In 1580, the ambassador sent horses to Vienna and Munich, fourteen in all.Footnote 57 Throughout the next two decades, he never stopped his shipments of horses and other animals and rarities, which cost him and the Austrian Habsburgs a fortune.

In the seventeenth century, the trade in curiosities and horses continued to be handled by the same figures. During the first decades of the century, the greatest German merchant of curiosities was Hainhofer, who is best known nowadays for the sumptuous cabinets that he assembled for aristocrats and sovereigns. Yet Hainhofer was equally interested in equine culture and served as an agent for procuring exotic horses.Footnote 58 When he decided to personally deliver the Pommersche Kunstschrank, the exquisite collector's cabinet, to Duke Philipp II (1573–1618) in Stettin, Hainhofer made several touristic visits to towns along the way. Dresden was a must, of course, and Hainhofer visited the stables right after his arrival in the city. His account of the stables presaged Zedler's focus from the following century on the number and rarity of horses, also paying attention to the spatial arrangement of the horses by race. As he wrote, the stable was “beautiful, large, clean, orderly and with high arches,” with an assortment of “Spanish, Neapolitan, Hungarian, Pomeranian, Frisian, Danish and Turkish horses, and, to sum up, each landrace stands by its own race, and each breed [razza] next to the other.”Footnote 59 While in the stables, he also had the opportunity to listen to a groom who explained the sixteen virtues that an ideal horse needed to have (e.g., “a small head, short ears and long tail, [like in] a fox”), which may well have instructed the viewers on how to judge the various body parts of the horses on exhibit.Footnote 60

Hainhofer was equally impressed with the arcade that featured the portraits of the Saxon electors, and then went on to praise the curious Handsteine, cuirasses, and armory for the horses in the Rüstkammer above. When he came back to Dresden in 1629, he again visited all these sites, using the same pared-down and telegraphic vocabulary to offer brief comments on naturalia, books, paintings, and horses. For Hainhofer, everything had to be “beautiful”; the two other things that mattered about the exhibits were their quantity and size: “The stable is arched, beautiful and built with large pillars, like a church, and has around 128 stalls next to each other at the three sides of a square, all full of horses, ordered according to their landrace, including a really large horse, as well as some smaller horses, and one dwarf for the young lord . . . next to either horse is a life-size portrait of a beautiful horse.”Footnote 61 Size, quantity, and beauty also mattered for the Kunstkammer. In the fourth room of the Kunstkammer, for instance, Hainhofer noted that he saw “all sorts of beautiful, large and small wax portraits, histories, counterfeits, animals in large number, in many beautiful and lively colors,” offering no further comments on these curious objects.Footnote 62 For Hainhofer, even books could be singled out for their beauty and not for their content, especially when they related to topics dear to a horse-riding nobleman's heart. In the ducal library, he singled out “two books of fights and tournaments, decorated with beautifully painted and illuminated images.”Footnote 63

Horses did not steal the show only in Dresden. In Cölln, by Berlin, during the trip of 1617, Hainhofer visited “the stables in the new building in which many beautiful horses stand,” and even “went inside a stall to [see] one horse,” which pushed him against the wall and tried to bite him.Footnote 64 Shaken by the experience, he went upstairs to the Rüstkammer, where he saw numerous saddles, bits, and swords, as well as books and featherwork. Finally, in Stettin, the conversations between Duke Philipp II and Hainhofer were split between horses and other curiosities. On one day, they looked at a hand-colored copy of Basilius Besler's (1561–1629) Hortus Eystettensis (The garden of Eichstätt, 1613); on another, they went to the stables to see the duke's numerous horses, all covered in colorful clothing and all bred at the local Pomeranian stud. As Hainhofer explained, Philipp II was the ideal prince because he was equally talented in courtly jousting and in scholarly learning. Like Duke August in von Birken's telling, the Pomeranian prince was “a beautiful, strong, heroic and courteous lord, skilled and experienced in tournaments, in the manege of the horse and in other exercises, well studied, learned in foreign tongues, and widely traveled, including Spain.”Footnote 65

A curious prince trained the body with horses and the mind with exotica. And if Hainhofer used his travels as a training opportunity for learning more about horses and art, he also relied on these skills in his mercantile exchanges with sovereigns. What he learned in Dresden and in Berlin served him well when serving Duke August the Younger in Wolfenbüttel.Footnote 66 Throughout the decades, Hainhofer was a constant supplier of curiosities, books, horses, and books about horses to the duke, whose interest in these topics was insatiable. Hainhofer ordered him Spanish horses from his Italian suppliers and books on horses from all over Europe.Footnote 67 Like Khevenhüller or Dietrichstein, Hainhofer was an aristocratic diplomatic agent who provided Central European sovereigns with rare horses and other kinds of exotica primarily from Southern European or Iberian lands.

In the years around 1700, the emerging genres of the museological treatise and the travel guide started to treat stables and museums together. In the early eighteenth century, for instance, Kaspar Friedrich Jencquel's Museographia provided an impressively comprehensive overview of cabinets of curiosities across Europe, and had no compunction about including the Berlin and Dresden stables or the London armories.Footnote 68 In his Die geöffnete Raritäten- und Naturalien-kammer (The open chamber of rarities and naturalia, 1704), Paul Jakob Marperger (1656–1730) mentioned the Dresden stables in one breath with the Kunstkammer, and proposed that exotic living animals could be kept in stables.Footnote 69 Nicolaas ten Hoorn's travel guide to Europe offered similar advice about horses and curiosities as essential sights for a traveler. If tourists followed ten Hoorn's guidance, they went to Kassel to see the castle, the stables, the gardens, and the library, as there were only a few other buildings of interest there: “The castle, the stable for horses and the garden, as well as the Dom and the parish church, with the princely graves, the elector's library, the college of the elector, the court of Nassau, the arsenal and the town hall, and Weissenstein, a retreat an hour away from town, are all worth seeing with attention.”Footnote 70

In his entry on Wolfenbüttel, ten Hoorn emphasized the fame of the riding school and the library in the same sentence, writing that “the specialties of this town are the excellent riding school and library, where an unusually large globe can be seen, the Kunst- and Rariteit-Kammer, and diverse beautiful churches.”Footnote 71 Dresden, in turn, offered visitors the opportunity to see “the palace of the Elector, his house for wild beasts, his stable and armory, in the Elector's palace there is a very spacious room painted ingeniously with towns, giants and the clothes of diverse nations,” together with the “Kunstkammer or collection of rarities,” which was filled with various instruments and tools.Footnote 72 Such pieces of advice remained the staple of travel guides for a long time. For instance, when it came to discussing the Hradčany Castle in Prague, Gottlob Krebel's late eighteenth-century Die vornehmsten Europäischen Reisen (The most distinguished European travels, 1783) mentioned the Spanish rooms, the “Kunst-, Naturalien- und Schatz-Cammer, the royal riding house, the royal pheasant and pleasure garden and the royal mathematical house” in the same breath, treating them as equally interesting sights for the visitors.Footnote 73

THE SPACES OF STABLES

The previous two sections made the argument that horses and other curiosities tended to be kept in the same building in early modern Germanic courts, and that there were strong parallels as to how experts described them, how curators inventoried them, how agents dealt with them, and how tourists visited them. In the absence of strong evidence, this section will not offer a causal explanation of why living animals and curious exotica were stored in the same building. Instead, I will argue that the architectural characteristics of stables were responsible for placing strong constraints on how both horses and curiosities were exhibited and viewed.Footnote 74 Horses were large animals, and princely competition required that each stable should house ever increasing numbers.Footnote 75 As a result, stables were big and the Kunstkammern in them were also remarkably large. While the previous two sections of this article aimed at broadening the concept of curiosity by including living horses in it, the remaining two sections will emphasize what made stables specific and how tours of their floors differed from the experience of visiting smaller cabinets.

How big was a stable? Zedler's Universal-Lexicon provided some explicit and prescriptive details on what an actual stable had to look like. Most stables were built up from rectangular building blocks that held two rows of stalls with a walkway in between. Zedler specified that the length of each stall had to be eight feet to give enough space for a horse, while its width varied from three and a half feet for riding horses to four feet for coach horses. Together with the walkway in the middle, the building's width was therefore fixed at an impressive twenty-two feet, while the length varied depending on the number of horses one needed to house. Given that the most important stables of Europe, such as Dresden, frequently housed over a hundred horses, an elegant stable's length could easily exceed five hundred feet.

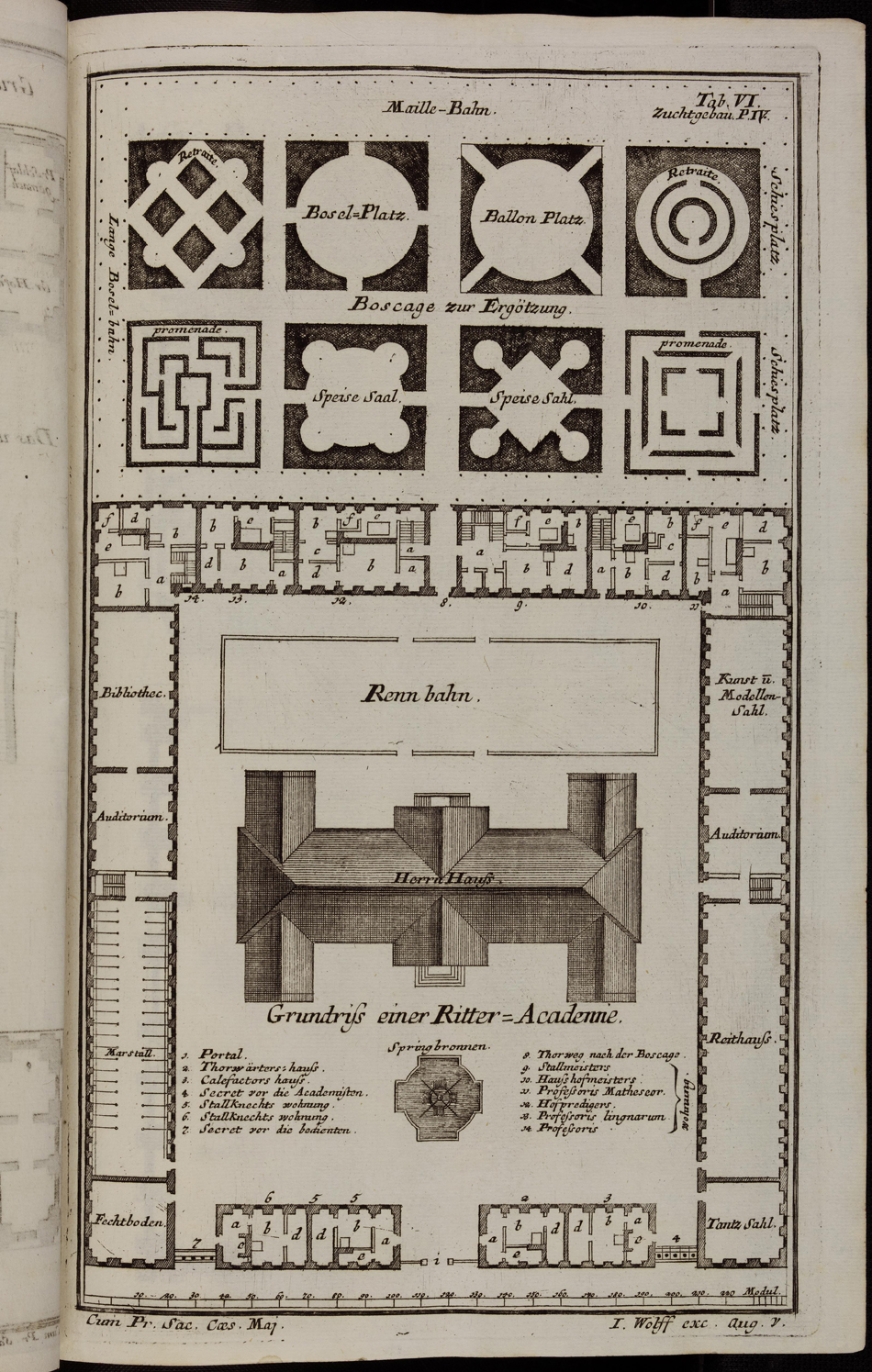

The idea to provide exact measurements for stables was not Zedler's invention. From the sixteenth century onward, architects and hippological experts claimed again and again that stables needed to be large and based on the size of horses, with each author proposing a somewhat different solution. Importantly, these authors were closely connected to the very courts that promoted the use of the stable as a Kunstkammer, especially Munich and Wolfenbüttel. As Zedler claimed, the direct inspiration for his designs was the mathematician Leonhard Christoph Sturm (1669–1719), a professor at the Wolfenbüttel riding academy.Footnote 76 Sturm was intimately familiar with the close connections between horses, curiosities, and the world of learning. In his ground plan for an ideal riding academy, for instance, he provided a blueprint for an educational building complex that could accommodate a cabinet of curiosity, a library, and a good number of horses, using the same elements of architecture (fig. 2).Footnote 77 When it came to describing stables, Sturm provided precise numbers about their ideal size. Unlike Zedler, however, Sturm preferred even wider and more spacious stalls for the horses. He argued that for costly horses a stall had to be five and a half or six feet wide and nine to ten feet long. The ideal stable was thirty, and not twenty-two, feet wide, with a varying length; consequently, the adjacent Kunstkammer had to have the same dimensions as well.

Figure 2. Leonhard Christoph Sturm. Anweisung allerhand oeffentliche Zucht- und Liebes-Gebäude (Augsburg, Reference Sturm1720), table 6, the plan of a riding academy. Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, T 2131 RES:1, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.18801.

Sturm may have been one of the earliest architects to write about building designs for stables, but hippological experts had been actively debating these issues well before him. For example, these issues were already scrutinized by Marx Fugger in the late sixteenth century. In the Von der Gestüterey, Fugger discussed carefully the perfect location for a stable, which had to be well protected from the wind, cold, snow, and rain. He also specified the width and length of each stall (six feet wide and nine feet long), which could then be used to determine the size of the stable. Fugger also provided details on the height of the stables and the positioning of the windows to provide adequate light for the animals.Footnote 78 A few decades later, the topic was taken up again by Löhneysen in Wolfenbüttel, who spent many pages on the considerations that one needed to keep in mind when establishing stables. He first discussed the perfect location of stables and analyzed what internal height was best to ensure that the stalls did not have too much draft yet were also free from stench; he argued that the ideal stall was five feet wide and nine feet long, and he then offered a list of the duties of the stable master, who also had to take care of the Rüstkammer on site.Footnote 79 It was this hippological tradition, developed at German Renaissance courts, that Sturm and Zedler relied on when writing their encyclopedic works. They may have disagreed on details, but the large size and rectangular shape of the courtly stable was fixed throughout the period.

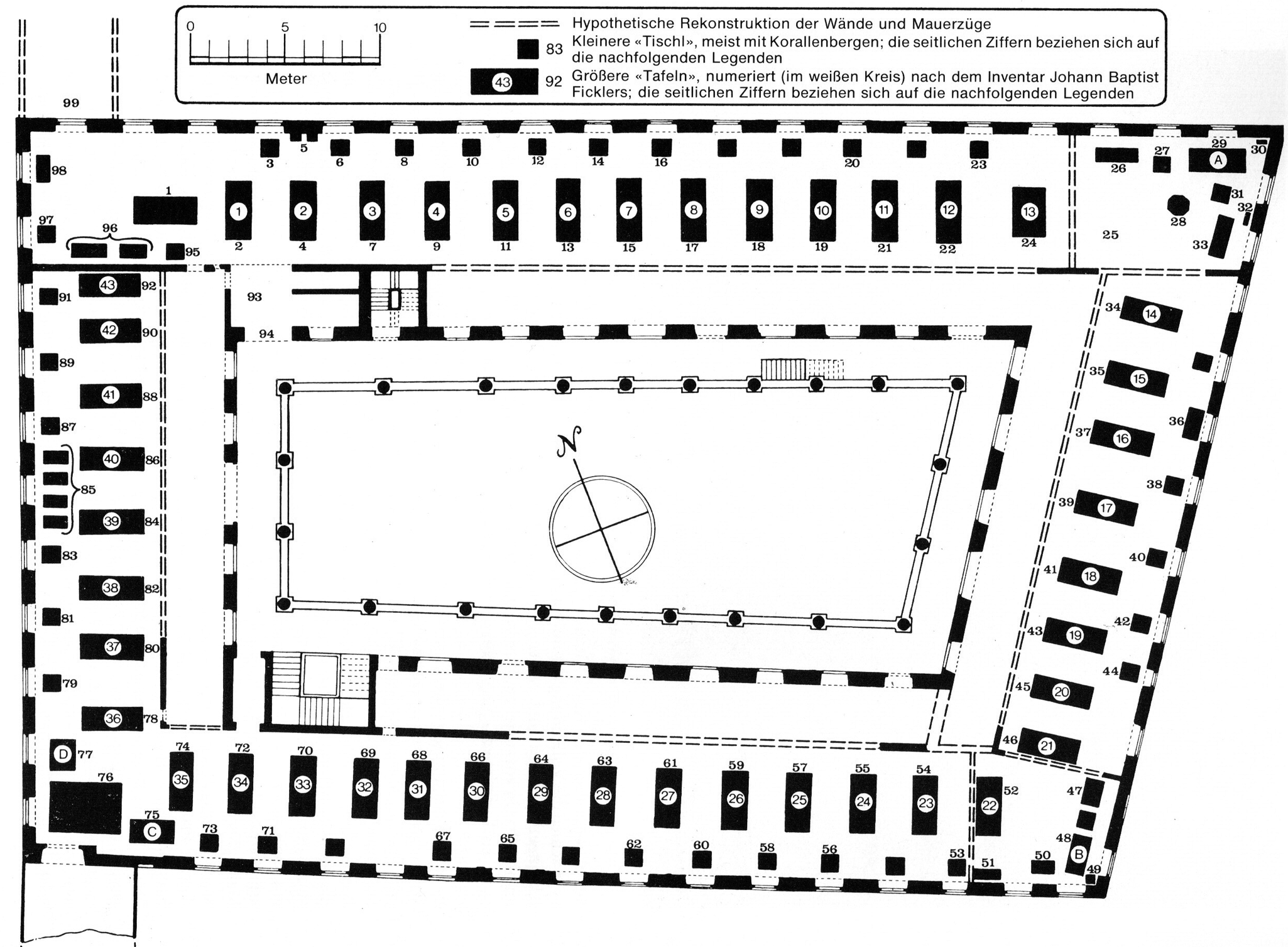

The architectural specifications of the stables played an important role in determining how curiosities could be showcased in such building complexes. Like the stables downstairs, these exhibition halls upstairs took the shape of elongated galleries that one could walk through at a leisurely pace while examining the curiosities from a moderate distance. Since the width of these buildings was predetermined, these Kunstkammern were by definition large and nowhere near as intimate as the private study of a prince. In Munich, for instance, the four galleries of the Kunstkammer offered a stunning viewing space where one could see innumerable curiosities on large tables in the middle of the gallery, while some smaller tables were placed on the side by the window, mostly decorated with mounts of corals in repetition (fig. 3).Footnote 80 The north gallery was 23-feet wide and 150 feet long, and the other three wings were not much smaller. As one passed through these halls they could examine and engage from close up with only a limited number of the over six thousand exhibits.Footnote 81 Yet even the large spaces of the stable could not keep up with the proliferation of curiosities in Munich. A few years after the establishment of the Kunstkammer, Duke Albrecht V was forced to build the Antiquarium, an even larger rectangular gallery that served to house the impressive sculpture collection that he had purchased from the Venetian collector Andrea Loredan. These busts and statues just did not fit. Even larger than the galleries of the Kunstkammer, the Antiquarium ended up more than forty feet wide and over two hundred feet long. It was a majestic hall with the sculptures lined up at the side to impress viewers who could not study them up close.Footnote 82 Many of the exhibits are still placed high up on the walls where one cannot see them in detail.

Figure 3. Reconstruction of the Munich Kunstkammer by Lorenz Seelig. With the author's kind permission.

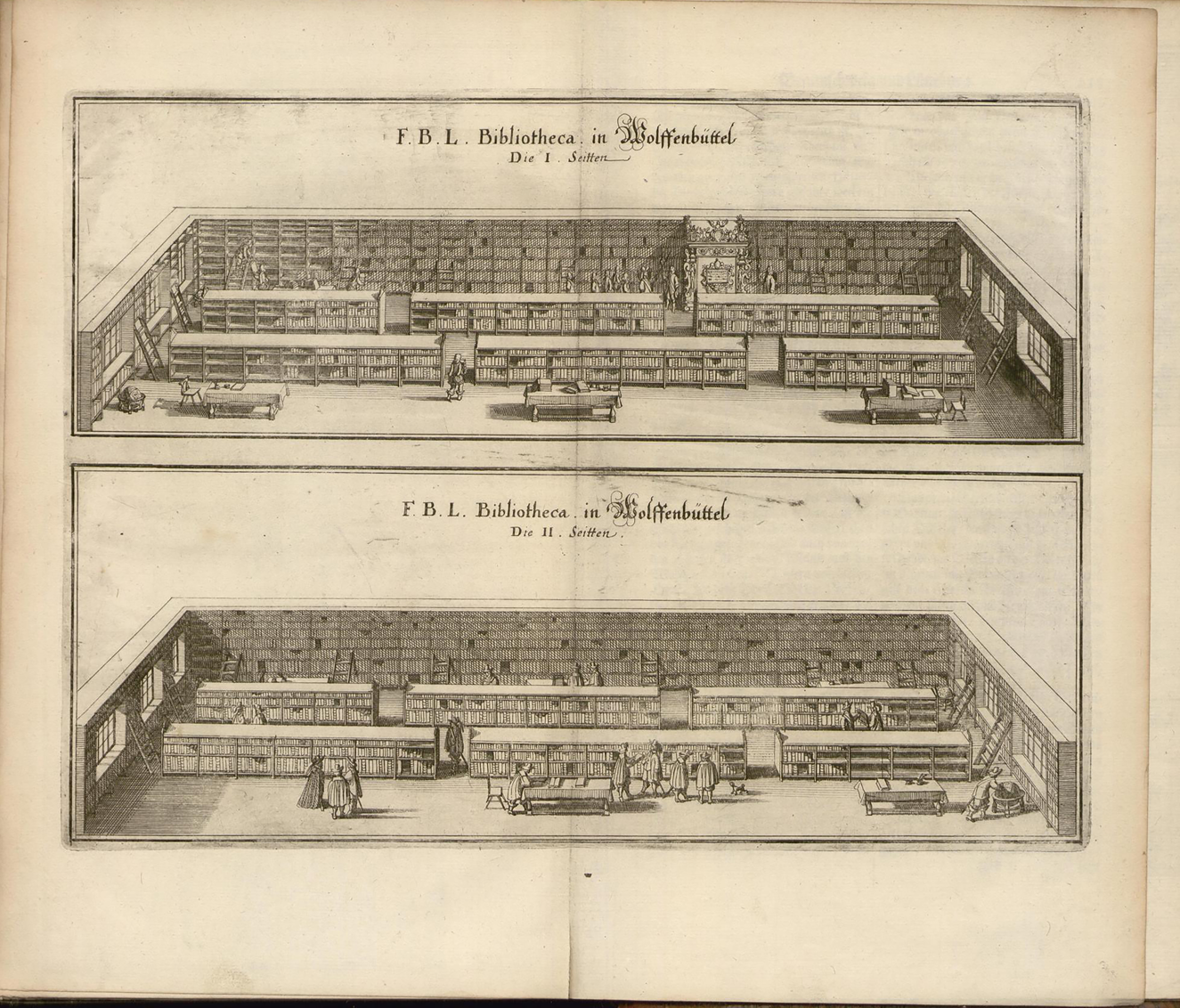

The requirements of the stable also influenced the size of the Wolfenbüttel library in the middle of the seventeenth century. As the Merian family's Topographia (Topography) from the 1650s explained, the stables of Wolfenbüttel once held a Rüstkammer upstairs, “where one could find many rarities,” but these upper stories now served as a storage space for over 64,000 volumes, as the Topographia specified.Footnote 83 The structure of the library mirrored that of the stables downstairs (fig. 4). As shown by Merian, the rectangular hall of the library was divided into three rows by the bookshelves, accentuated by three windows at each end, just as the stables were divided into two rows of stalls and a walkway in between. Apart from the large globe that ten Hoorn would also mention, the print shows rows and rows of volumes, with no visual clue offered to distinguish the books from each other. However promising stables may have looked as storage and exhibition spaces for a large number of collectibles, Wolfenbüttel ran out of space in a few decades. It was probably the limited size of the Marstall that necessitated the erection of a new building fifty years later.

Figure 4. Matthäus Merian. Topographia, the library in Wolfenbüttel, after page 210. SLUB Dresden, Hist. Sax. inf. 4, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-db-id4043508870.

The architecture of stables did not necessarily restrict the shape of the exhibition spaces to elongated galleries. These large halls could also be divided into smaller rooms by the installation of semi-permanent dividing walls. This was the strategy that was followed in the case of the Viennese Stallburg, when the Gemäldegalerie was installed upstairs in the 1660s. Built as a square around an inner courtyard, both the ground-level stables and the upper-floor Gemäldegalerie had spacious arcades overlooking the court. The horses’ need for regular light provided ideal viewing conditions for the art. Behind the arcades, the upstairs section of the building contained a series of rooms that opened from one to another, with plenty of windows that allowed enough light in to see the paintings.Footnote 84 The same architectural blueprint could be used to exhibit prize pictures and animals (figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Nikolaus Franz Leonhard von Pacassi. The Stallburg's ground floor. Albertina Museum, Vienna, AZ6383.

Figure 6. Nikolaus Franz Leonhard von Pacassi. The Stallburg's second floor. Albertina Museum, Vienna, AZ6384.

The restricted size of the Stallburg's rooms may have allowed viewers to have a reasonably close encounter with paintings, but there were just way too many to engage with all. In the 1720s, the director of imperial buildings, Ludwig Gundacker, Count of Althann (1665–1747), ordered the painter Ferdinand Storffer (1693–1771) to paint a paper version of the complete museum: Storffer provided a separate image of practically every wall in each room, with exquisite miniatures replicating each exhibited object, shown in their frames and with the wallpaper. As a result, historians have a good understanding of how visits to the Stallburg must have proceeded. After entering the museum, viewers wandered through the arcades before walking through a large number of connected rooms. Throughout, the walls were densely bedecked with paintings and curiosities, offering an impressive assortment of art objects arranged thematically and by genre. The gallery's exhibition space became a Gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art) that was clearly designed to impress as much through its overall effect as through the individual value of each particular object. Consider, for instance, just one wall in the galleries of the Stallburg where twenty-three floral still lifes were hanging next to each other (fig. 7). For viewers, this room's value may not have depended on the individual qualities of each painting. Stacked next to each other, the twenty-three paintings gave one a good impression about the strengths and weaknesses of the genre but did not exactly encourage close engagement with each work of art. The textual descriptions of Storffer's Bildinventar show that the collections’ managers rejoiced more in listing and inventorying a large quantity of paintings than in studying each painting in detail. Instead of providing lavish commentaries to match the sumptuous visual presentation, the inventory described the paintings in the plainest terms, as if they were interchangeable with each other, describing the paintings as “a man's head” or “an older man's head” without any further information. On occasion, the artist was mentioned, as in “a piece with flowers and fruits by Rachel Ruysch,” but this was as far as the descriptions went.Footnote 85 The genre and the name of the author were sufficient to describe a work of art.

Figure 7. Ferdinand Storffer. Neu eingerichtes Inventarium der Kayl: Bilder Gallerie in der Stallburg (1720–32). Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG Storffer Bd. II. Photo: KHM-Museumsverband.

Praise of the overall impression of the Stallburg coupled with brief and casual remarks on the individual paintings also sufficed for travel writers. As Antonio Bormastino's (d. 1729) travel guide to Vienna specified, one could simply not “enumerate all the objects, especially because there are eleven rooms both large and medium-sized, all filled with paintings.”Footnote 86 This was not just hyperbole. When it came to discussing the paintings of Italians, Bormastino noted that it would be “too long to name” all of them. And while some paintings were singled out for their rarity, such as Pieter Bruegel's (1525–69) Tower of Babel, most artworks could be dispensed with in a short phrase. When it came to the room of flower still lifes, Bormastino wrote only that “one needs to be skillful to picture from the life the fruits, flowers, and other similar things,” reducing the whole genre into one pithy comment.Footnote 87 As Bormastino suggested, visitors to the Stallburg were best off when they admired the exhibited works as a group.

Stables shaped viewers’ experiences of Kunstkammern not only through their architecture but also because their location made them accessible to relatively larger, though still mostly aristocratic, publics. As shown in the case of Ambras, Munich, Dresden, Vienna, and Wolfenbüttel, princely horses were usually kept near the sovereign's residence, but not directly inside it. As Löhneysen advised, “it would also be good if the stables were not in the house, but rather outside it, and also away from the privies and the pigs.”Footnote 88 The liminal location of stables enabled the creation of distance between the sovereign and the animals and exhibits that projected the sovereign's power. The cabinet of a sovereign could only be visited in circumstances strictly determined by the prince, usually in the private setting of an audience where a few selected curiosities provided the opportunity for engaged conversation.Footnote 89 In contrast, the stables were semi-public spaces that traveling aristocrats could visit without an announcement, as Count Bethlen did in Berlin. Travelers had the opportunity to view the objects on their own or with the help of a guide. In the case of Munich, for instance, Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cities of the world, 1572–1617) openly announced that curious people were always allowed in the Kunstkammer and, as mentioned earlier, Hainhofer was able to see the Dresden stables guided by a simple groom.Footnote 90 Hainhofer did not have to listen to and accept the owner's interpretation of the significance of each particular object—he could admire the sights but did not have to linger long.

Two paintings of the same collection provide a poignant illustration of this contrast. In the early 1650s, David Teniers the Younger (1610–90) completed several paintings of Archduke Leopold William's private gallery in Brussels. One version from 1651 reveals an irregularly shaped, cramped room, the spatial structure of which bears no resemblance to that of a stable (fig. 8). Even though Teniers's painting is a somewhat idealized representation of the collection, he was right in placing the artworks in a palatial setting.Footnote 91 The archduke himself is present at the center of the painting, stepping from one painting to another while guiding the other viewers’ attention. The assorted paintings on the floor and the few curiosities on the table give the impression that the archduke had ordered a select number of works to be brought out and had them unveiled for the sake of his visitors. Once Leopold Wilhelm's collection arrived in Vienna, and was securely installed in the Stallburg, the archduke's intimate manner of directing the viewers’ attention disappeared together with the sovereign. In 1728, when the inventory of the Stallburg's collections was completed, Count Althann commissioned Francesco Solimena (1657–1747) to commemorate this event in a painting (fig. 9). This image, which was exhibited at the Stallburg, did not picture Emperor Karl VI (1685–1740) within the gallery. The emperor was standing in full armor out in open air, with Count Althann delivering only the inventory of the museum. The emperor maintained ownership of the paintings by having lists drawn up by the personnel but, unlike Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, he projected his power from a distance. Viewers could come and explore the paintings on their own terms. As in Munich or in Wolfenbüttel, the Stallburg's visitors could engage with a large number of exhibits that were not always directly connected to the sovereign's personal interests.

Figure 8. David Teniers the Younger. Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in His Picture Gallery in Brussels, ca. 1651. Oil on copper. Museo Nacional de Prado, Madrid.

Figure 9. Francesco Solimena. Emperor Charles VI and Gundacker, Count Althann, 1728. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, GG 1601. Note the inventory in Count Althann's hands. Picture Credit: KHM-Museumsverband.

It is time to return to Schloss Ambras once more to see how such a visit played out in detail. On the afternoon of 27 April 1628, during a longer stay in Innsbruck, Hainhofer was sent off by Archduke Leopold V (1586–1632) to see Ambras on the outskirts of the city. The archduke did not join Hainhofer on this outing; his guide was the concierge and treasurer Kaspar Griessauer. This afternoon half-day trip was crammed with sights. Hainhofer first saw the main castle of Ambras, and then he split his time at the lower court between the armors and bards in the Rüstkammer and the curiosities in the Kunstkammer. Inside the Kunstkammer, Hainhofer was mostly interested in the curious interior architecture of “a long room that has a window on both sides and in the middle there are twenty cupboards reaching from the ground to the ceiling that one can go around and open toward the windows.”Footnote 92 Apart from noting the unusual arrangement of the cupboards, Hainhofer noted the large number of paintings that bedecked the walls, including portraits of “beautiful, large horses,” and four stone tables standing symmetrically in the room's four corners.Footnote 93 Not having much time, Hainhofer quickly went through the contents of each cupboard, noticing that the main organizational pattern was to put things made of the same material in the same cupboard, but not paying much attention to individual items: “1. All things from alabaster, turned, cut and carved, such as paintings, cabinets, platters, beakers, decanters . . . 2. The other cupboard is filled with small and large glasses, cut and uncut. 3. The third cupboard is filled with coralls, crucifix, a mountain with pictures and animals.”Footnote 94

Hainhofer's account of the Kunstkammer contained roughly two sentences about each cupboard. He then spent the rest of the day in the library before hurrying off to dinner with Griessauer, noting with sadness that “in these twenty cupboards there are so many beautiful, expensive and wonderful objects, that one would need many months to see and contemplate them properly.”Footnote 95 Hainhofer's ideal may have been the extended contemplation of each individual object. Yet, when pressed for time in a sizable Kunstkammer, his attention shifted toward the overall impression the interior conveyed, and brief notes on the general types of the objects that he saw in large quantities. An expert in curiosities knew how to see things quickly.

CURIOUS BREEDS

If the architectural constraints of stables meant that princely Kunstkammern were too large to contemplate in detail, how did the same setting affect the presentation and observation of horses in the same building? If the exhibition of innumerable flower paintings made Bormastino produce brief and unoriginal reflections on the genre of still life, how did viewers organize their thoughts upon seeing over a hundred horses in less than ideal viewing conditions? Stables held large numbers of horses for the purposes of theatrical performance, courtly tournaments, and simple travel, and visitors only caught a glimpse of living horses’ many qualities when locked up in rows of stalls. Their brief and imperfect impressions tended to focus on the horses’ quantity and on one, intangible quality that was abstracted from the shape and color of the individual animals: their racial genealogy. If one horse was an individual, a hundred horses were a breed.

In An Anthropology of Images, Hans Belting made a powerful contrast and comparison between the coat of arms and the portrait panel as two different ways of representation in courtly society. A Renaissance aristocrat could be pictured as an individual with particular qualities, or as a token member of a long genealogical line. Indeed, as Belting emphasized, when the first portrait panels of the aristocracy were created, “entire series of portraits had to be commissioned so as to reproduce the genealogical chain.”Footnote 96 The genealogical attitude reached its zenith in the Germanic courts considered here. In Dresden, the arcades connecting the stables to the court featured portraits of the electoral family to emphasize the continuity of their rule. Schloss Ambras also contained a gallery of Habsburg genealogical portraits that Hainhofer did not fail to note. In parallel, the noble horses in stables could also be considered as members of a genealogical chain. They were not a curiosity because they were one-off, particular, strange things; they were wonders because they served as embodiments of the problematic abstraction of razza, a word that meant race, breed, and stud at the same time.Footnote 97

Consider the highly popular Equile of Van der Straet. It is the only known early modern print series that explicitly claimed to portray a stable, that of Khevenhüller's friend, and it pictured it as a collection of breeds.Footnote 98 The forty engravings of the Equile presented racial and ethnic types as opposed to particular individuals from the stable (fig. 10). Each print prominently featured the name of the race (Armenian, Barb, or Thessalian), and each horse was placed in front of a nondescript landscape. A brief inscription explained the characteristics of the race: for example, claiming that the Calaber was “a valiant and wise horse that originated from the mighty Calabrian shores, whose head and belly are short, but his rear is large.”Footnote 99 Straet's decision to employ a place-based, racialized interpretation of Don Juan d'Austria's stables proved determinant for the success of his print series, which directly influenced seventeenth-century natural history. In this period, authors across a variety of disciplines agreed that the qualities of a horse depended on its place of origin and the local temperature, humidity, and quality of pasture there.Footnote 100 It was for this reason that the chief encyclopedias of zoology in the seventeenth century by Aldrovandi and Jan Jonston (1603–75) devoted much of their attention to the racial diversity of horses.Footnote 101 As Jonston wrote, the “differences, or kinds of Horses are manifold; the cheefe are borrowed from places, parts and certain accidents.”Footnote 102 Similarly, Aldrovandi devoted a separate chapter to the geographic diversity of this celebrated animal. Repeating stereotypes that were commonplace throughout the period, Aldrovandi claimed that African and Arabian horses were really fast, and then continued his discussion of horses from Babylon, Bisnagar, Britain, and Burgundy, before going on to discuss Calabria and the rest of the alphabet. Significantly, both Aldrovandi and Jonston relied on the inscriptions of Straet's Equile to provide descriptions of some particular and lesser known breeds, such as the Albanus, the Barbarus, and the Maurus.Footnote 103 Engravings of horses in a particular aristocratic stable could double as general descriptors of a breed.

Figure 10. Philips Galle, after Jan van der Straet. Thessalus from the Equile Ioannis Austriaci (ca. 1578). Engraving. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1889-A-14392.

The German hippological tradition put an equally strong emphasis on developing an abstract typology of horses. For these authors, however, the concept of the breed relied only partly on the Hippocratic, climatic understanding of race. While Marx Fugger's Von der Gestüterey acknowledged the importance of place of origin from the beginning, it also praised the ability of breeders to mate horses from different lands to develop new and ever more beautiful types of horses.Footnote 104 Fugger explained that, in Italian studs, races could be molded in the expert hands of breeders.Footnote 105 In the studs of Mantova, the Gonzagas had mated numerous stallions and mares from Turkey, Barbary, and Spain so that the resulting offspring became uniformly beautiful and generally praised, though not as strong as the Neapolitan. This was also the reason why the common horses of Bohemia were so different from those reared in the studs of noblemen in the same land. Because horsemasters relied not only on local horses, and were able to provide different feed, the horses of Czech aristocratic studs did not fully conform to the general horses of the region. This was equally true for Spain, where, as Fugger remarked, the only horses of note were those that were bred in Andalusia's studs. For Fugger, the qualities of a particular stud were the unit of admiration, and particular horses came to the fore only in as much as they represented the ideal established for a breed. When he discussed Bucephalos (Ox Head), the renowned stallion of Alexander the Great, Fugger rejected the claim that the animal got his name because it was a strange monster. It was, rather, that it was branded with the mark of an ox head at the stud of Philonicus in Thessalia, where it was born.Footnote 106 The best-known horse of history was not a monstrous curiosity but the representative of a breed.

Seventeenth-century treatises continued to emphasize the importance of having a well-organized stud in a well-chosen region for the production of uniformly high-quality horses. In Wolfenbüttel, Löhneysen's Della cavalleria dealt extensively with the issue of breeding beautiful horses for aristocrats and gentlemen. Like Fugger, Löhneysen began his discussion with the general, Hippocratic explanation of the relationship between complexion, humoral theory, and the environment, but then strongly stressed the role of studs in standardizing a breed, focusing on the Habsburg imperial studs. As he noted, these studs produced beautiful and good horses not just because of their location, but because they were able to blend the qualities of the best Neapolitan, Spanish, and Hungarian stallions and mares through well-designed breeding. Even when it came to the Neapolitan horse, moreover, Löhneysen did not consider it a simple landrace whose qualities were determined exclusively by the local climate. Instead, he pointed out that there were several different types of Neapolitan breeds, depending on the stud where they were produced. The famous coursers, for instance, did not simply benefit from the balmy weather of Southern Italy. Without exception, they all came from the same royal studs where they were improved upon by expert stable masters. The Della cavalleria's interest in the role of studs in producing uniformly high-quality horses reached its culmination in its chapter about branding, where the author discussed the important and commendable practice of marking colts and fillies with a special burnt mark.Footnote 107 The horses of a stud were not unlike the masterpiece of an artisan, which served as a guarantee for consistently high quality. They bore a visible brand that guaranteed that they could live up to a high standard.Footnote 108

Throughout the seventeenth century, branding made heredity visible, collapsing individual horses into the category of the breed or the race. In the last third of the 1600s, the most important hippological author in Germanic lands was Winter von Adlersflügel, whose stupendous Tractatio Nova (New treatise, 1672), a four-language folio treatise with double-folio engravings, provided a graphic depiction and description of the practice of breeding horses.Footnote 109 Winter went further than others in stressing the importance of breeding over simply admiring horses because of their origins. As he argued, the new commercial society made it impossible to trust what horse dealers claimed about their wares. While place of origin may have mattered in earlier eras, it could not serve as a marker of quality when there was no guarantee that a putatively Turkish horse actually came from Turkey. Conscientious aristocrats, therefore, needed to establish their own studs to maintain the high quality of their stock. To do this, their stable masters had to pay some attention to the environment where horses were bred, but it was even more important to consider the qualities of the parents, and especially hereditary diseases. A horse could inherit from its parents too big a head, too long an ear, too small a nostril, and too tight a mouth, as well as blindness, a choleric temperament, or gallstones.Footnote 110 To avoid these diseases, breeders needed to procure a beautiful, perfectly proportionate stallion and a mare of similar qualities in order to produce a new razza, Winter claimed.Footnote 111

As in an aristocratic family, heredity and the careful coupling of noble blood ensured the passing of ideal perfection from generation to generation. Brands on horses served as visible markers of their lineage, as Winter's illustrations to his books made clear (fig. 11). In these images, genealogy triumphed over the individuality of the horse. As Winter explained in a corresponding chapter, horses did not necessarily need a name. They just had to have a branded number corresponding to the stud register. Such brands also provided information on the horse's parentage and year of birth. In figure 11, for instance, the mark “N 63” on the stallion's neck meant that the horse came from the nation of Neapolitan horses and was born in 1663, while the mark “SN 64” on the neck of the mare meant that her father was a Spanish horse, her mother was a Neapolitan, and she was born in 1664. Winter put this system of branding into practice in the studs of Ansbach, where visitors to the stables could look at a particular horse and immediately place it in a genealogical chain.Footnote 112 Heredity was burned into the skin of a horse, making it impossible for viewers to miss.

Figure 11. The mating of two horses. Georg Simon Winter. Tractatio Nova de Re Equaria (Reference Winter1672), after page 80. CC-BY-NC-SA4.0 Universitätsbibliothek der Humbolt-Universität zu Berlin, https://www.digi-hub.de/viewer/resolver?urn=urn:nbn:de:kobv:11-d-4742291.

Fugger, Löhneysen, and Winter were not theoreticians writing in an ivory tower. Fugger owned studs in Hungary and in Allgäu, and Löhneysen was a stable master in Wolfenbüttel. As a result, their theoretical claims about issues of race, breeding, and heredity became directly relevant when owners and visitors to stables attempted to make sense of the large numbers of horses contained therein. If viewers looked at these animals, they saw the products of a stud, the members of a breed or race. This is not meant to argue that horses could not be appreciated as individuals. Owners and riders of horses often developed close, personal relationships with a particular horse. Prince Maurits of Orange, for instance, was so impressed by his white Spanish stallion that he had it portrayed by Jacques de Gheyn II; the dukes of Mantova had some of their favorites painted in the Palazzo Te.Footnote 113 In Dresden, when August the Strong's (1670–1733) favorite horse, called the Merseburger, died around 1700, his skin was prepared and exhibited in the Rüstkammer.Footnote 114 Yet there is also ample documentation that, for many people who interacted with horses, the individual qualities of the horse became secondary to its group characteristics.

I will now turn my focus back to the horses in the Stallburg, which came from the renowned studs of Lipizza, Kladrub, and Halbthurn in the late seventeenth century.Footnote 115 During these years, Pietro Francesco Rainier, the stable master of Lipizza, sent regular updates about the studs to his boss, Count Ferdinand Bonaventura I von Harrach (1636–1706), in Vienna. Rainier's task was to maintain a continuous, high-quality stock of horses from which he could supply the Stallburg on a yearly basis. His favorite mode of writing about horses was the genealogical inventory, based on the concept of razza that Winter also employed.Footnote 116 In May 1679, for instance, his letter to Harrach reported that nineteen colts and eleven fillies had already been born that year, and in August he compiled a table of all the horses born in what he called the razza of Lipizza.Footnote 117 For each animal, he listed its color, whether it had a white star on its head or a spot on its feet, and, most importantly, its parentage.Footnote 118 That was all the information that he needed to provide for the Stallburg, which placed an emphasis on having a large supply and not just individual wonders. Every year, when Rainier sent his horses up to Vienna, he supplied them with a similarly organized inventory that used the same descriptors as his birth records. In April 1679, nine colts went up to the Stallburg; the same number was brought up in 1688 (fig. 12).Footnote 119 During his twenty-year career in Lipizza, Rainier rarely, if ever, singled out a horse as an individual worthy of attention.Footnote 120

Figure 12. Rainier's inventory of horses. Austrian State Archives, Vienna, AT-OeStA/AVA FA Harrach Fam. in spec 330.

Once at the Stallburg, the horses were presented as links in a genealogical chain. In the 1720s, when Storffer was busy preparing his visual inventory of the gallery, a similar project, by Johann Georg de Hamilton, under the oversight of Count Althann, was also undertaken downstairs. Taken together as a group, these paintings offered a unified perspective on what was considered a beautiful horse in this period, allowing viewers to engage in generalizations that are not unlike Bormastino's comments on the genre of flower paintings. Working in a bureaucratic mode, Hamilton painted his portraits on copper sheets of the standard size of 49 by 64 cm, which were inventoried and marked on the back by number at the Oberstallmeisteramt (Office of the Master of the Horse) upon receipt. In all of the paintings, the horses were pictured against a similar nondescript landscape background.Footnote 121 Each horse may have displayed a different color and pattern of spots, as the Viennese had not yet adopted their preference for uniform whiteness, but otherwise the shape of their bodies and heads reflected widely accepted ideals of the period.

Importantly, the main function of these paintings was to promote the breeding potential of Habsburg stables, and they made explicit the importance of race and genealogy, even for lay viewers. Hamilton's portrait of the horse Gentilo, for instance, featured the inscription “Gentilo, an original Spanish, was sent to the stables from Halbthurn under the instructions of His Excellency, the stable master Count of Althann in 1722.”Footnote 122 Even in his portrait, Gentilo was marked as the representative of the Spanish race and as the product of the renowned Halbthurn studs, which first adopted the use of stud books in the very same years when the portraits were commissioned.Footnote 123 While the horses were being painted in Vienna, the stable masters of Halbthurn were busily recording how the very same animals sired new generations of horses that kept the ancient blood and the stud's excellence alive.Footnote 124 Like Winter's Tractatio Nova, moreover, Hamilton's paintings also prominently displayed the brands of the horses to advertise that these were standardized products of a place. For instance, the portrait of Masgalan featured a crowned C on his haunch, the brand of the imperial studs, as well as an L on his head, the marker of Lipizza, where he was bred (fig. 13). The most important project to immortalize the Stallburg's horses reduced these animals to tokens of a brand. Breeders and painters both worked on turning horses into embodiments of the abstract concept of the breed.

Figure 13. Johann Georg Hamilton. Masgalan, ca. 1720. Schönbrunn, Vienna. © Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. / Fotograf: Alexander Eugen Koller / Sammlung Bundesmobilienverwaltung.

Guided by these stable masters and court painters, visiting travelers to the Stallburg and other stables would often pay attention only to the general characteristics of horses. Some only cared about the quantity and general excellence of horses, like John Burbury, who visited the Stallburg in 1671 and noted that there were “many brave and goodly horses, to the number of one hundred and twelve.”Footnote 125 Similarly, when the learned French traveler Balthasar de Monconys (1611–65) visited Dresden, he cared only about the number of the horses. After describing the architecture of the stables in great detail, Monconys mentioned that almost 150 horses could be housed there, and that the stables were practically full. He did not write a single word about any particular horse. Done with the stables, Monconys then climbed upstairs to admire the twenty-four beautiful sleds that were artfully decorated, and provided a long list of the arms, dresses, harnesses, and other curious objects preserved there.Footnote 126 Yet others were more forthcoming about the possibility of discerning the beauty of a particular breed, or race, when viewing horses in a group. As mentioned earlier, when Hainhofer visited the Dresden stables, he only noted the architecture of the stable, the total number of the horses, and that they were “Spanish, Neapolitan, Hungarian, Pomeranian, Frisian, Danish and Turkish” and arranged in groups according to landrace. And when he visited Stettin, Hainhofer emphasized that all the horses were from the local Pomeranian stud.

One did not have to be a refined expert to turn one's attention to breeds. When in Dresden, the English gentleman traveler Fynes Moryson (1566–1630) noted that the stables contained “some 136 choise and rare Horses” and that race played a role in the arrangement of the animals, as those in the main stables were “all of forraine Countries, for there is another stable for Dutch horses.”Footnote 127 Breed did not only matter to visitors to Dresden. When Duke Ferdinand Albrecht of Brunswick-Lüneburg, son of the library founder Duke August in Wolfenbüttel, visited Innsbruck in the second half of the seventeenth century, his reflections were similarly restricted to the fact that there were “Florentine, Neapolitan and all other types of horses” there, before proceeding to the Rüstkammer and the Kunstkammer in Schloss Ambras, where he was most impressed by a genealogical volume of all the Roman emperors from Julius Caesar to Rudolf II, “on large pages, artfully portrayed on horses.”Footnote 128 When traveling, it was horses, breeds, and genealogy that aristocrats wanted to see.

CONCLUSION: THE CURIOSITY AS EXHIBIT

This article has shown that many early modern collections were housed above stables, in the same buildings where courtly horses lived. It mobilized evidence for this claim from several courts in early modern German-speaking lands, and argued that there were strong interactions between the different stories of these buildings. Collectors and travelers came to talk about horses as one more type of curiosity. The same agents were responsible for sourcing Spanish horses, exotic parrots, or birds of paradise, and when early modern travelers visited stables they admired the horses just as much as the other exhibits on the upper stories.

I have argued that the architectural constraints of stables provided strong limitations on how the horses and the collections could be exhibited and, ultimately, on how these animals and the curiosities could be viewed. Stables were large buildings that could house numerous works of art. Unlike the private and intimate studio, or studiolo, the galleries of stables were sizable, semi-public spaces that allowed the semi-autonomous circulation of visitors among an impressive number of exhibited objects. In Wolfenbüttel, the long rows of books created as much an impression in travelers as the particular volumes they may have consulted during a brief visit. In Munich, the repetitive patterns of coral tree decorations in front of each window emphasized quantity and curatorial design over the particular characteristics of each curiosity. As I've suggested, the interest in exhibits as representations of a type was equally strong downstairs in the stables. The numerous elegant horses standing there were valued for being part of a breed or a race. Horses were marked with a brand, one that could signal their land of origin and the stud where they were bred. Like a modern Louis Vuitton bag, they could be admired as wonderful objects of luxury even if they were produced or reproduced in large numbers.

This article's argument has provided an alternative to the current historiography that emphasizes the focus on the singular in the early modern culture of collecting. This is not to deny that early modern curiosi could be fascinated by the individual details of the many artworks they encountered during their travels. Arguably, early modern viewers of curiosities engaged in two alternative manners of seeing. They closely engaged with a few objects that caught their attention, and then briefly looked through other groups of objects that impressed as much by their quantity as their quality. As Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) noted with a critical eye when visiting the Kunstkammer in Vienna (a stone's throw from the Stallburg), the Habsburgs “were more diligent in amassing a great quantity of things, than in the choice of them. I spent above five hours there, and yet there were very few things that stopped me long to consider them.”Footnote 129 Five hours is a considerable amount of time, and Montagu was clearly not a member of the Instagram generation. Yet maybe one could write a history of leisurely attention that seamlessly passes from one curiosity to another, without pausing to examine either for a long time.Footnote 130 Surely, visitors paused to scrutinize some artworks in great detail. But they also glanced over many in a quick succession to form a general impression of the genre of flower paintings, or of the breed of Lipizzaners. The education of the senses and the development of connoisseurship probably happened through the constant interplay of these two different ways of seeing. And even today, how often do we stop to admire in a gallery the infinite charm of a Vermeer, and how often do we simply note that there are four or five portraits by Frans Hals in the same room, all of them looking more or less the same? And how often do we end up with potentially useful generalizations about genre or artistic style as a result, and how often do we end up with pernicious, racialized stereotypes instead?