Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the economy and societies around the world with governments implementing a vast array of emergency measures to mitigate its impact. As the pandemic lingered on, countries with well-developed private pension systems have debated whether to implement measures to allow withdrawals from pension savings (Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022). In Latin America, proposals were debated in countries like Mexico, Peru, Chile, Colombia and Bolivia (Financiero, Reference Financiero2020) but only a handful of them implemented withdrawal legislation. The reduction in pension savings (following withdrawals) raises important policy questions regarding the adequate level of future pensions (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019; Rofman & Oliveri, Reference Rofman and Oliveri2012), but also the mix between the public and private pillars of pension systems and ultimately the sustainability of the latter (Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022).

We seek to understand the variation in pension withdrawals by comparing the cases of Chile, Bolivia and Peru. From a comparative perspective, the three countries share some common characteristics. They are all in the same region, and all of them introduced a mandatory pillar of private pension accounts in the 1980s and 1990s, notwithstanding some design variations. More recently, they were all hit by the COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote 1 and have used withdrawals as part of their crisis response strategy but (again) with significant variation. While less than 1 per cent of savings were withdrawn in Bolivia, these have reached 30 per cent in the case of Chile and 67 per cent in Peru.

Emerging analyses have claimed that withdrawals may ultimately undermine the sustainability of private pillars (Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022). However, we contend that not all withdrawal measures are similar and hence we need to understand such variation to ascertain whether withdrawals may in effect put in question the survival of private pensions. We contend that variation can be understood by examining the role of policy legacies and the institutional setting. Specifically, we consider the experience with recent re-reforms (or the lack of them) and the ability of the executive to press for changes once the pandemic-induced economic crises hit these countries. We argue that where there is a legacy of blocked re-reforms and an institutional setting that makes change difficult, measures that lead to a significant amount of savings being withdrawn may be favoured by political actors to break the stalemate. By contrast, where re-reforms have been largely implemented and the political institutional setting poses few barriers to change, withdrawals may be more limited.

Our analysis contributes to the emerging literature on social policy responses to the pandemic (Béland et al., Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick and Moreira2021, Reference Béland, Dinan, Rocco and Waddan2022; Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2022) while providing useful insights for other countries in the region (and beyond) that may consider implementing pension policy changes to address financial pressures. Furthermore, it contributes to the literature on pension reforms and re-reforms (Baba, Reference Baba2015; Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019; Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017).

The next two sections discuss the different approaches to the understanding of pension policy change, introduces our theory and explains our research design. We then proceed to discuss each case to illustrate how our theoretical framework allows us to understand the different outcomes. The final section discusses and compares our findings and provides some insights to understand other cases in the region and the implications for future research.

Continuity and change in pensions policy

There is an extensive literature on the factors that explain the growing state involvement in social policy across the region since the early 2000s (Ewig, Reference Ewig2016; Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012; Niedzwiecki, Reference Niedzwiecki2018; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). In general, these contributions have considered macro-factors such as democratic development and the ideology of governments, the degree of electoral competition, the role of societal veto players or the role of political institutions and legacies.

Regarding ideology, considering that many social policy reforms at the beginning of this century took place under left governments, Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2012) argued that the irruption of the left and its commitment to social justice was central to the adoption of reforms (Madrid, Hunter, & Weyland, Reference Madrid, Hunter, Weyland, Weyland, Madrid and Hunter2010). Yet, some observers have correctly pointed out examples of reforms that took place under centre-right governments, as in Colombia, Argentina and Chile (Niedzwiecki & Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2017; Staab, Reference Staab2017). These observations have led scholars to argue that when politicians face intense competition, they have an incentive to capture more voters and embrace significant reform (Ewig, Reference Ewig2016, p. 197). Consequently, parties that face a strong opposition may have a stronger incentive for comprehensive reform (Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). This explains why even centre-right parties facing a strong opposition may push for marginally expansive social policies, as in Chile and Argentina under centre-right governments in the 2010s (Niedzwiecki & Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2017, p. 88).

Other analyses have highlighted the key role of political institutions (Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019; Niedzwiecki & Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2017; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). Borrowing from the literature focusing on reforms in the 1990s (Brooks, Reference Brooks2009; Madrid, Reference Madrid2003) it is argued that in countries with presidents with powerful institutional prerogatives (such as being the leader of her own party and not having to consult with cabinet members and whose party or coalition dominate congress) policy changes can be more radical compared to countries whose president lacks strong institutional prerogatives or does not have a majority in congress (Arza, Reference Arza2012; Castiglioni, Reference Castiglioni2010; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2014). Scholars have also highlighted the role of veto actors such as trade unions and social movements in the reform process (Castiglioni, Reference Castiglioni2018; Niedzwiecki, Reference Niedzwiecki2014; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013).

Regarding legacies, and building upon the concept of policy feedback developed by Pierson (Reference Pierson2001), scholars have argued that policies may also produce negative feedbacks that undermine them and ultimately lead to their change (Jacobs & Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Weaver, Reference Weaver2010). For example, Arza (Reference Arza2012) shows how the low levels of support for the private pension system in Argentina in the aftermath of the 2001 crisis and the low levels of coverage and savings provided support for its elimination in 2008. Similarly, Borzutzky (Reference Borzutzky2019) argues that negative policy legacies in terms of low expected future pensions played a significant role in the Chilean 2008 re-reform. Providing a broader understanding of policy legacies, Ewig and Kay (Reference Ewig and Kay2011) argue that actors generated by previous reforms play a significant role in supporting change or resisting it. Analysing the case of Chile, Borzutzky (Reference Borzutzky2019) stresses the role of the emerging No + AFP (No more AFP) movement in Chile since around 2016. Yet others have also highlighted how the powerful pension industry has been successful in outmanoeuvring and resisting re-reform attempts affecting the private pillar (Bril-Mascarenhas & Maillet, Reference Bril-Mascarenhas and Maillet2019; Ewig & Kay, Reference Ewig and Kay2011). Scholars have also highlighted the role of new social movements in advancing re-reforms that aim to increase the role of the state in pension provision. For example, in Bolivia, grassroots movements linked to the ruling Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) have contributed to the introduction of the non-contributive pension Renta Dignidad in 2007. Their role was also significant during the 2010 reform that legislated for the elimination of private pension administrators (AFPs) (Anria & Niedwiecki, Reference Anria and Niedwiecki2016).

Analyses of the 1990s pension reforms in the region stressed the role of crises (especially economic ones) as triggers for reforms given the significant weight of pension systems in public finances (Brooks, Reference Brooks2009; Madrid, Reference Madrid2003). Beyond the region, Casey (Reference Casey2014) and Wilson Sokhey (Reference Wilson Sokhey2017) highlighted that the 2008 crisis and the need for EU countries to reduce budget deficits made the elimination of the private pension palatable. Likewise, in the case of Argentina, Baba (Reference Baba2015) and Datz and Dancsi (Reference Datz and Dancsi2013) argued that the 2008 crisis and the lack of access to credit helped convince policymakers about the advantage of eliminating the private pillar. Yet, most scholars agree that while crises may help to make the need for reform evident, they are far from shaping them. More recently, Kay and Borzutzky (Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022, pp. 34–35) argued that measures introduced in Chile as a response to the pandemic should be understood within the context of the 2008 re-reform and more recent unsuccessful attempts to re-reform the system.

We argue that the insights from the policy change and pension reform literature on the role of policy legacies and institutions can be most helpful to understand variation in pension withdrawals. We contend that the pandemic has opened a window of opportunity to introduce changes in countries with fairly well-developed private pension pillars, whose savings may be used as a tool for providing financial relief during the pandemic. Yet, the variation in the measures adopted will depend on the specific combination of legacies from previous re-reforms (or the lack of them) and the institutional setting in each country. More specifically, we argue that where there is a legacy of blocked re-reforms and an institutional setting that makes change difficult, measures that lead to a significant amount of savings being withdrawn may be favoured by political actors to break the stalemate; although the legacy of the private system may play a role in limiting the scope of the withdrawal measures finally adopted. By contrast, where re-reforms have been largely implemented and the political institutional setting poses few barriers to change, then withdrawals may be more limited.

Methods and research design

We follow a comparative analysis based on the most similar system (MSS) research design (Przeworski & Teune, Reference Przeworski and Teune1970, p. 34) by selecting cases that are broadly similar in many key aspects but vary in the outcome of interest (Ragin, Reference Ragin1997, p. 12). The countries under study are in the same region, share several historical characteristics and, more importantly, developed a sizeable pillar of private pensions by 2020 following the first wave of pension reforms in the 1980s and 1990s. Notwithstanding design differences, by 2020, savings in this pillar were 32 per cent of GDP in Peru, 49 per cent in Bolivia and 67 per cent in Chile (Fiap, 2020). This is well over the average of 14 per cent across countries with mandatory private pillars (Ortiz et al., Reference Ortiz, Durán Valverde, Urban and Wodsak2018).

Our two independent variables are legacies and the institutional setting. While legacies can be broadly understood, we focus on whether previous re-reforms that sought to change the private pension pillar were adopted or not and the role of key veto players such as the pension industry and social movements. Regarding the institutional setting, we consider the power of the president in terms of whether they are the leader of their party and their support in Congress.

Our outcome of interest is pension withdrawals, as measured by the amount of savings withdrawn as a percentage of total savings. We considered other possibilities such as the number of legislative withdrawal measures; however, we think it has significant limitations. Specifically, a higher number of measures may not necessarily lead to a high amount of savings withdrawn. While it is true that Bolivia passed one measure that led to less than 1 per cent of savings being withdrawn, Peru has passed two laws leading to 67 per cent being withdrawn. Meanwhile, Chile has passed three, but as a result, 30 per cent of savings were withdrawn. An alternative would have been to construct an index measure of the “withdrawal generosity” of each law. However, producing such an index would require us to weight different aspects embedded in each law (eg. age limits, taxation and maximum amount allowed to withdraw) increasing the risk of inadvertently introducing some bias. By contrast, our measure is a widely available one that can be used to compare across the analysed countries.

Pension responses to COVID-19

Chile

Chile was at the forefront of pension privatisation introducing in 1981 a mandatory pillar of private pension accounts managed by private administrators (Administradores de Fondos de Pension – AFP). Thanks in part to Chile’s economic growth, the system had accumulated savings of around 70 per cent of GDP before the 2008 global financial crisis. However, since the early 2000s, many experts highlighted that future pensions would be inadequate for workers with low and middle incomes due to the lack of contributions because of periods of unemployment or working in the informal economy (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019).

In 2006, the newly elected President Bachelet set up a Pensions Commission (Marcel Commission) that proposed the most significant changes to the system since the 1981 reform. Yet, the legacy of a strong pension industry (given the high levels of savings) allowed it to outmanoeuvre the government and succeed in leaving the private pension pillar virtually untouched (Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019; Bril-Mascarenhas & Maillet, Reference Bril-Mascarenhas and Maillet2019). In fact, the most significant aspect of the 2008 re-reform was the replacement of the Minimum Income Guarantee with the more generous Pension Básica Solidaria – PBS, granted to those aged 65 and over not eligible for any other pension, and the introduction of an additional pension (Aporte Previsional Solidario – APS), a tapered benefit designed to supplement private pension income (Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019).

Yet, dissatisfaction with the private system regarding the low level of future private pensions continued. In this process, a new social movement emerged, the No+AFP (No more AFP) that has campaigned strongly since 2015 for the outright elimination of the private pillar and for switching all members to a new public pillar (Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019, p. 12). President Bachelet in her second term set up a new Pensions Commission (Comisión Bravo) to recommend changes to the system. Yet, as the Commission was not able to agree on a single option, it proposed instead three alternatives (Comisión Bravo, 2015). The President introduced a reform bill in Congress based on the option of maintaining the private pillar and introducing a new employer contribution of 5 per cent to fund a second pillar run by the state. Lacking enough support, the bill was not treated in that term.

The new administration of President Piñera introduced in October 2018 a bill that proposed a new employer contribution of 4 per cent, which would go to the private pillar. It also proposed a new public-run pillar to complement retirement income for middle-class earners and women, financed out of general revenues (Macías, Reference Macías2019). On both occasions (second Bachelet and the first Piñera proposals) the strong legacy of the private pillar played a key role in ensuring that the private pillar would be left virtually untouched, while the No+AFP movement disregarded the proposals as not going far enough (La Izquierda Diario, 2017). Also on both occasions, the government lacked enough support in Congress to pass the proposals, given the particularity of the Chilean Constitution that requires special majorities to pass laws related to social security, called leyes de quórum especial (Cifuentes & Williams, Reference Cifuentes and Williams2019). The social protests triggered at the end of 2019, meant that the bill did not make progress in Congress. The weakened administration of Piñera was not able to make progress on a new re-reform bill introduced in January 2020.

COVID-19 hit the country in early March, with cases and deaths increasing rapidly in the following months.Footnote 2 The issue of allowing withdrawals from private accounts gathered pace while the government was seen as ineffective in dealing with the pandemic (Jornada, 2020). The opposition in the Chamber of Deputies seized the opportunity and proposed a bill allowing withdrawals of up to 10 per cent of the accumulated fund. The bill was passed in June 2020 and sent to the Senate where the debate was intense, given the need to achieve the special majority required by the constitution. It was key for the opposition to garner the support of senators from the centre-right government coalition, which has traditionally defended the role of the private system (Borzutzky, Reference Borzutzky2019). Thus, the opportunity provided by the pandemic to introduce a change to the private pillar was balanced against the weight of the private pension industry and the institutional setting, which makes changes difficult (Bárcenas Vidal, Reference Bárcenas Vidal2021, pp. 109–110). This “opportunity” combined with the weakness of the President, hit already by the 2019 protests and now the pandemic, and the view that “something needed to be done.” This view was even shared by some members of the President’s coalition even if they had traditionally supported the private pillar. As a senator from the centre-right UDI put it clearly “this is a bad idea and I will always be a member of the UDI, but I’ve always said that I would support it if there was no other alternative” (Senado, 2020).

The proposal was finally passed by 29 to 13 votes thanks to the support of several members of the centre-right coalition government (Senado, 2020). As a result, the law allowed for a withdrawal of up to 10 per cent of the fund. The maximum amount allowed to be withdrawn was 150 UFFootnote 3 (approx. 5,500 USD) and the minimum 35UF (around 130 USD). Members with savings below 35UF could withdraw all the savings (Ministerio de Trabajo y Prevision Social, 2020a).

In the following months, the debate around pension reform continued as the government and the opposition maintained conversations, but no further progress was made. Negotiations with the government stalled and opposition parties presented a bill allowing for a second withdrawal of up to 10 per cent that was passed by the Chamber of Deputies in October 2020. Against this background and worried about being outmanoeuvred by the opposition, the government presented its own proposal to allow a second withdrawal (El Mostrador, 2020a). The move took the opposition by surprise, and while the private pension industry criticised it (El Mostrador, 2020b), the strong legacy of the private system was still relevant as the proposal put significant limits to withdrawals and allowed for the payments to be made in two instalments. The bill also established a threshold above which the amount withdrawn would be taxed (Ministerio de Trabajo y Prevision Social, 2020b). Finally, both Chambers passed the government proposal in early December.

As the pandemic’s second wave hit the country in March 2021, members from the opposition and the governing coalition presented new withdrawals proposals on the back of criticisms to the government for its handling of the pandemic (As Chile, 2021). The President tried to counter the proposals by presenting new measures of financial aid for families (La Tercera, 2021a). In the end, the Senate passed the proposal in April, which was fairly similar to the first one: it allowed to withdraw up to 10 per cent of the fund within the same limits set in the first withdrawal (Ministerio de Trabajo y Prevision Social, 2021). As with the first withdrawal, members of the government coalition supported the proposal claiming that something had to be done. In the words of Francisco Chahuán, member of the right-wing Renovacion Nacional the feeling was that “the executive is not reacting and that there is no other alternative to support the families facing a difficult situation” (Torres, Reference Torres2021). The government presented a motion before the Constitutional Tribunal to block the proposal which was subsequently dismissed and the proposal was passed by the Chamber of Deputies (La Tercera, 2021b). The proposal was led by the Deputy Pamela Jiles from the Humanist Party, whose leaders also feature prominently within the No+AFP movement. Deputy Jiles presented a new proposal for a fourth withdrawal, which failed to pass (La Tercera, 2021c).

As a result of the three withdrawals, 50bn USD in savings were withdrawn, representing 30 per cent of savings held in the system in July 2020. Studies have warned about the effect of withdrawals on the adequacy of future pensions (FIAP, 2021). This echoes concerns from some scholars about the possible undermining of the private system (Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022).

Peru

Peru reformed its pension system in 1993. Unlike Chile, the reform did not close the public pillar, but introduced a new private one (Madrid, Reference Madrid2003). The policy makers expected that the two systems -the old Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) financed public pillar Sistema Nacional de Pensiones (SNP) and the private pillar Sistema Privado de Pensiones (SPP)- by operating in parallel, would compete for members. At the time of the reform, recognition bonds were issued to finance the future pensions of members of the public pillar that decided to switch to the private one. This unique characteristic of the system in having the public and the private pillar competing for members has been widely criticised as not being effective in ensuring that each pillar addresses specific risks and in diversifying risk (BID, 2019, p. 19).

As in other Latin American countries, labour market informality led to poor contribution records. Furthermore, the commission charged by the private pension administrators Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones (AFP) was around 2.78 per cent of contribution until the early 2010s, the highest in the region after Colombia (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2016). Labour market informality has been decreasing in recent years, yet it is still one of the highest in Latin America, as around 74 per cent of the workforce in 2018 was in the informal sector (BID, 2019). As a result, the coverage of the private system has remained relatively low, at around 27 per cent, measured by the number of contributors as a percentage of the active workers (Arenas de Mesa, Reference Arenas de Mesa2019, p. 145). Some estimate this figure to be much lower (12 per cent) if considering those making active contributions each month (Cordero Rosado, Reference Cordero Rosado2019, p. 26), raising concerns about the adequacy of future pensions from the private pillar. Yet, the introduction of the system in the early 1990s and the economic growth that Peru has achieved since the early 2000s (only recently interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic) allowed the private pension industry to become a key player in the public scene. The system is concentrated in four AFPs, which, in total, had assets of around 24 per cent of GDP, in 2019, the second highest in the region, yet much lower than Chile, which reached 70 per cent of GDP (FIAP, 2020).

In recent years, concerns about the future adequacy of pensions have been prominent in the public policy arena. During the 2011 presidential campaign, the centre-left presidential candidate Ollanta Humala expressed the need for a significant reform in which the private pillar would be voluntary and the first public pillar would have a non-contributory and a contributory tier covering all workers. The elected President acted on his promise and in 2012 presented a reform proposal aimed to address issues such as the low coverage levels and the high fees of AFPs (Cordero Rosado, Reference Cordero Rosado2019). Yet, President Humala had a minority support in Congress, with only 47 out of 130 seats in the hands of Gana Peru, his party. Furthermore, during the debate on the reform, the AFPs had significant influence during the process actively participating in the working group that designed the reform proposal. This meant that many of the changes discussed during the presidential campaign such as moving towards a true multi-pillar system never made it to the proposal finally presented in Congress (Durand, Reference Durand2016, p. 49). Ultimately, the 2012 reform was limited and focused on reducing the commission charged by AFPs. A further reform proposal in 2014 to force self-employed to contribute to either of the two pillars was significantly resisted by self-organised groups (America TV, 2014). The lack of progress in pursuing further changes was fuelled by the fact that President Humala lost the support of some members of his party towards 2015 (Sosa, Reference Sosa2015).

The reform of the pension system remained high in the public policy agenda. In 2016, the newly elected President Kuczynski announced he would send a bill for a major reform of the system, even though the AFPs would be maintained (Gestion, 2016). This did not materialise given the small support of the president’s party in Congress (only 18 Deputies for Peruanos for el Kambio) and the scandal that followed the pardon of former President Fujimori and Kuczynski’s consequential resignation in March 2018. President Martín Vizcarra took power in a similar weak position and in September 2019 dissolved Congress. The elections in January 2020 did not resolve the president’s weak position as his party Somos Peru obtained only 11 seats.

As COVID-19 significantly hit the economy in April 2020, members of Congress started to debate the possibility of allowing withdrawals from pension pots to provide some financial help to members. The AFP association was vocal about the long-term impact of such move, and the fact that it would benefit mainly those who had savings and thus were not vulnerable (IPE, 2020). However, the weak situation of President Vizcarra meant that Congress rejected his proposal for a more complex and significant reform and rushed to approve a law in April 2020 allowing members to withdraw up to 25 per cent of their pots, with a maximum of 12,900 soles (US$3.573) (El Universo, 2020). The bill had been previously vetoed by the president, but Congress insisted and passed the bill into law (El Peruano, 2020a).

As the country continued to suffer the impact of COVID-19, members of Congress focused on allowing a second withdrawal. In the words of some of its proponents, now the goal was to reach 100 per cent of the fund: deputy from Podemos Peru José Luna Morales stated that “the goal still remained to reach consensus to allow withdrawals of 100 per cent, in specific circumstances” (El Comercio, 2020a). After lengthy negotiations among the different parties in Congress, a law was finally passed in November allowing members who did not make contributions in the last 12 months to withdraw up to 17,200 soles (US$4.765) (El Peruano, 2020b). Discussions about a new withdrawal for up to 100 per cent of the fund are still ongoing.

We contend that the rather moderate legacy of the private system, given the moderate level of savings, has combined with a highly fragmented institutional setting that is not prone to reach consensus on major re-reforms. The pandemic opened a window for change and all this has led actors to push for more generous withdrawals than in Chile. As a result, Peruvians have withdrawn 44bnUSD, representing 67 per cent of total savings held in April 2020. As in Chile, observers have pointed out that these withdrawals question the future viability of the private system (Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022, p. 41). Furthermore, as withdrawals have not been complemented by the creation of a new non-contributory pension, this will lead to significant income adequacy problems in the future (El Comercio, 2020b), as also highlighted in Chile (FIAP, 2021).

Bolivia

Bolivia implemented a significant reform in 1997 by replacing the old PAYG public pillar with one of individual pension accounts (Mesa Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2002). The system quickly consolidated around two private pension administrators (Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones – AFPs) and given its mandatory feature, managed to accumulate a moderate level of savings of over 22 per cent of GDP by 2010 (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2014, p. 10). The reformed pension system also included a non-contributory scheme (Bonosol), which provided a low benefit of about 248USD (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2014). Yet, a significant problem for the new private system was the adequacy of future pensions, given the large informal sector of independent workers, which stayed at around 58 per cent of the economic active population in the early 2000s.

The left-leaning and movement-led administration of Evo Morales (2006–2020) implemented a series of reforms to the system broadly shaped by the legacy of a system with low coverage but moderate savings and a political institutional setting in which the government had to negotiate reforms with social movements (Carrera & Angelaki, Reference Carrera and Angelaki2021, p. 32). The result of these reforms, most notably the 2010 reform, was the maintenance of the system of private accounts, now under the management of a public administrator (Gestora Pública de la Seguridad Social). However, given the weight of the private pension industry, the government quickly discarded the option of buying AFPs assets, concerned that the new public administrator would inherit judicial claims for unpaid contributions that had to be recovered (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago, Ortiz, Valverde, Urban and Wodsak2018, p. 11). The result has been a long process of negotiation for the orderly exit of the AFPs. While the Gestora was initially scheduled to start operating in 2011, this was postponed to 2017, and it was then announced that the start of operations would not take place before the third quarter of 2021 (Correo del Sur, 2019).

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country, arguments were put forward about the possibility of using the funds held in private pension accounts to alleviate the situation of workers who had savings in the private pillar but were now unemployed. In a society where grassroots movements had actively participated in previous reforms (Anria & Niedwiecki, Reference Anria and Niedwiecki2016), it was no surprise that a movement supporting the withdrawal of funds quickly set up: the Movimiento de Emergencia Nacional para la devolución de los aportes de las AFP (MEN). This led to a bill introduced in the finance Commission of the Chamber of Deputies in October 2020 that proposed the withdrawal of up to 10 per cent for those with savings of between 3,000 and 100,000 Bs, and of 100 per cent for those with savings of 3,000 or less (La Razon, 2020).

At the same time, the candidate of the MAS Luis Arce openly supported the idea of an emergency withdrawal and sent a proposal to the Commission of the Chamber of Deputies for a withdrawal of up to 10 per cent for those with savings of more than 100,000 Bs (Calderon Garcia, Reference Calderon Garcia2020). Once Arce won the October 2020 elections, the MEN members started to press the newly elected President to introduce a new bill to Congress by the end of the year (Filomeno, Reference Filomeno2020). Yet, the government in the words of the Finance Minister Marcelo Montenegro, argued that it was necessary to “carefully think this move given the consequences it could have on the savings of the AFPs and on the members” (Filomeno, Reference Filomeno2020).

Finally, the government sent a bill to Congress in January 2021 allowing for the withdrawal of up to 15 per cent of the fund for those with savings of 100,000Bs or more and of 100 per cent for those with savings of up to 10,000Bs. However, the bill stipulated specific exclusions, most notably that those claiming the withdrawal must be unemployed. The MEN initially rejected the proposal arguing that for many people the amount withdrawn would not be enough to, for example, start a new business (Filomeno, Reference Filomeno2021).

The government started a “socialisation” process of the bill, aiming to get consensus around the proposal. A key concern was to address the criticism that the measure would affect the sustainability of the system of private accounts. In May 2021, the Economy Ministry argued that the measure would not affect the sustainability of the system as it had savings of 21Bn USD. Furthermore, it was argued that this measure would be mostly financed with current contributions, rather than AFPs needing to sell the stocks in which funds were invested (Correo del Sur, 2021). Yet government officials still argued that the decision as to whether to request a withdrawal would need to be considered carefully and that it may not be in the interest of every person.

Against this background, the MEN continued to organise demonstrations throughout the country, while the government continued to explain the bill as part of the “socialisation” process. Thus, during the first half of 2021, the bill did not make progress in the Chamber of Deputies while the government tried to garner consensus, most notably with the mobilised members of the MEN. Finally, in early August it was agreed with the MEN to include a provision allowing those with savings over 100,000Bs to withdraw up to 15,000Bs, notwithstanding the age or the level of savings (Correo del Sur, 2021).

With the agreement of the mobilised sectors secured, the government passed the bill in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate in August 2021, where it holds a majority. As agreed, the law stipulates that those with savings up to 10,000 Bs and over the age of 50 will be able to withdraw 100 per cent; those with more than 10,000Bs and up to 100,000Bs will be able to withdraw up to 15 per cent and those with more than 100,000Bs up to 15,000Bs. In all cases, applicants must be unemployed (Gaceta Oficial de Bolivia, 2021). While signing the Act, the President and the Economy minister highlighted that the decision to withdraw must be carefully thought, commenting that “these funds are most needed when a person can no longer work” (La Razon, 2021).

A few days after the signing of the law, the government issued a decree stipulating that the transition from the AFPs to the new Gestora Publica de la Seguridad Social will start in May 2023. Whether this happens will depend on the migration of pension account records to the Gestora (Belmonte, Reference Belmonte2021). This is the sixth time since 2011 that the start of the Gestora has been delayed.

Overall, the legacy of re-reforms that have maintained private pension accounts (even with a long transition towards the public administrator) and a political institutional setting that is prone to change given the government majority in both Chambers has led to a withdrawal legislation with specific limits on amounts and eligibility criteria (most notably being unemployed). As a result, the total amount withdrawn reached 155 million USD, which represents 0.6 per cent of assets held in the system. This is significantly below the levels withdrawn in Chile and Peru.

Discussion and conclusions

We theorised that legacies from previous re-reforms and the political institutional setting are key to understand recent changes brought upon during the pandemic. Our analysis has shown that, in the context of the COVID-19 emergency, where re-reforms to the private pension system have been blocked, actors favoured provisions that led to significant amount of savings being withdrawn. By contrast, where re-reforms to the private system have been largely implemented, actors have favoured measures that have led to a much lower amount of withdrawals. Furthermore, the institutional setting has been central in understanding the type of changes introduced.

In Chile, political actors saw the withdrawal legislation as an alternative to a more significant revision of the system that has been blocked since at least 2016. Given the institutional design that prevents significant change and requires special majorities for pension-related changes, the opposition had to convince centre-right legislators by reference to the pandemic and the need to act. While some centre-right legislators supported the withdrawal measures, the President referred the third withdrawal to a revision by the Constitutional Tribunal, one of the many “authoritarian enclaves” of the 1980 Constitution currently in force (Garretón, Reference Garretón2003), although this did not work. Nonetheless, the strong legacy of the private pillar meant that there were some limits to the amounts allowed to be withdrawn in the three instances. In this context, Chileans withdrew around 30 per cent of savings.

The analysis of Peru also shows that actors favoured withdrawal measures as an alternative to a more significant reform of the system that has been blocked since 2012. In a highly fragmented political setting with weak presidents, successive withdrawals have been the only avenue to introduce changes to the system in response to the pandemic. Adding the limited role of the private pension industry, this has resulted in a legislation that is more generous than in Chile and has led to 67 per cent of savings being withdrawn. Yet, as warned by observers (Instituto Peruano de Economía – IPE, 2020) this may be a temporary solution and a more significant reform of the system will be necessary to address the sustainability and adequacy issues of the entire system; which looks hard to achieve giving the weak fragmented institutional setting.

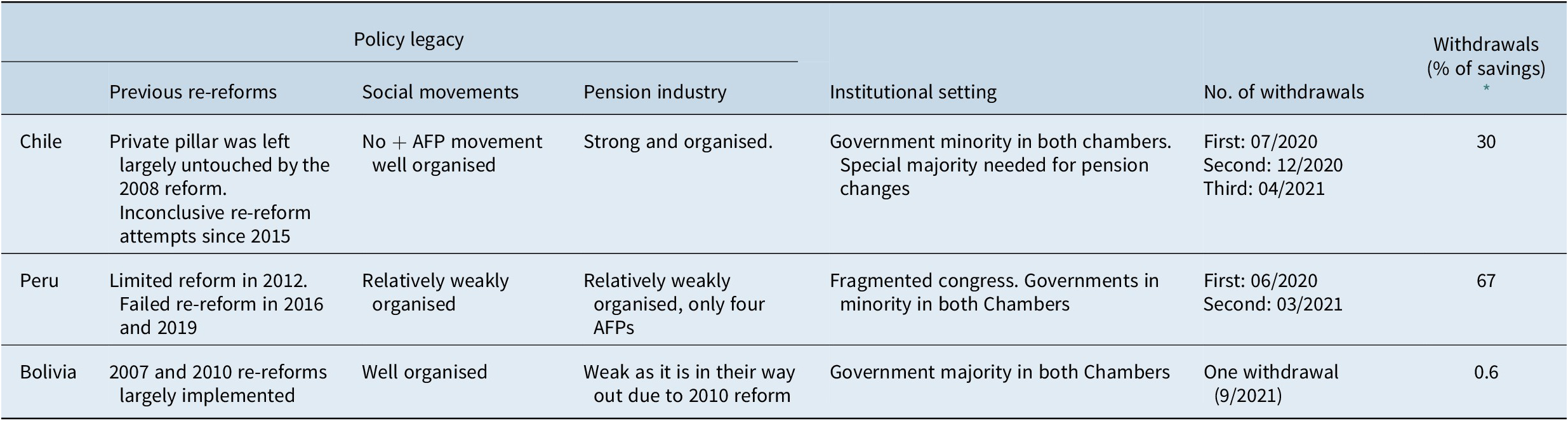

By contrast, in Bolivia, the legacy of re-reforms that maintained private pension accounts, coupled with a political institutional setting in which the President has significant support in Congress, meant that actors favoured withdrawal legislation that set out significant limits, especially around the fact that only the unemployed could withdraw savings. Yet, legacies from previous reforms still played a role as the Government had to agree a consensual approach with mobilised grassroots organisations as had been the case in the 2007 and 2010 re-reforms. In this context, Bolivians have withdrawn only 0.6 per cent percent of savings. Table 1 provides key indicators that illustrate our comparative findings.

Table 1. Key variables and outcome.

By showing the effect of policy legacies and institutions on pension withdrawal outcomes, our analysis has demonstrated that alternative approaches traditionally suggested by the literature on social policy change are less useful to explain such variation. For example, regarding the role of ideology (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012; Madrid, Hunter, & Weyland, Reference Madrid, Hunter, Weyland, Weyland, Madrid and Hunter2010), the expectation would be that centre-right parties oppose measures that affect the private pillar, while centre-left parties would support them. Yet, in Chile, the centre-right coalition of parties supported some of the withdrawals, while in Bolivia the centre-left government highlighted the need for a one-off limited withdrawal. Likewise, the argument around political competition and that governments facing a strong unified opposition would support more far-reaching changes to “tip the balance in its favour” (Ewig, Reference Ewig2016, p. 197) is not supported by our analysis, as Peru experienced the most significant change in terms of withdrawals, yet these have been passed in a context of weak governments facing a fragmented congress.

Previous analyses have also claimed that richer countries will favour measures that support private savings (Béland, Reference Béland2019). Yet, while Bolivia is the poorest of the countries under study, total withdrawals have entailed less than 1 per cent of savings. Meanwhile, while Chile is the richest, withdrawals have reached over 30 per cent. More recent analyses have suggested the capacity of withdrawals to undermine the private pillar (Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022) but we have shown that not all withdrawals are similar and that whether they ultimately have that capacity will depend on the combination of policy legacies and institutions.

Furthermore, by higlighting how institutions and policy legacies combined in different ways in the context of the pandemic, leading to different pension withdrawal outcomes, we stress that pension policy changes are complex processes where a variety of factors combine in different ways. Thus, further research that employs methods that can take account of such complexity, such as qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), should be considered in explaining possible future paths to social and pension reforms, following withdrawals (Carrera & Angelaki, Reference Carrera and Angelaki2020; Niedzwiecki & Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2022).

We focused on one policy area (pension policy) and in a limited number of countries in a specific region, which may pose some limits to the extent to which the results of the study can be generalised. However, we contend that our analysis provides further evidence to emerging questions related to the future adequacy of pensions (especially for women) and to the inability of private systems to minimise political risk. These questions have been raised by the emerging literature on the social policy responses to Covid-19 (see Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2022, pp. 2–3). Similar questions have already attracted the attention of scholars (within and beyond the region) concerned about the viability of private pension pillars and their ability to provide adequate future pensions following reversals or (more recently) withdrawals (Bocanegra, Reference Bocanegra2022; Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2022; Kay & Borzutzky, Reference Kay and Borzutzky2022; Simonovits, Reference Simonovits2011; Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017). This also points to the need to examine more carefully how policy design affects inequalities both during the pandemic, but also in its aftermath (Béland et al., Reference Béland, Cantillon, Hick and Moreira2021; Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2022).

As we slowly move into the post-pandemic era, discussions are likely to emerge in the region and the broader Global South on the content of future social policies as a consequence of the short-term emergency measures implemented during the pandemic (Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2022, p. 8). In such context, recent developments such as changes to the law-making process, as in Chile following the proposed new Constitution or the persistent political fragmentation, as in Chile and Peru, and the legacy of the private system and its capacity to provide adequate benefits may impact on the design of future pension policy. This shows the necessity of further research on the role of institutions and policy legacies in shaping policy continuity and change.

Disclosure

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed by the authors.

Notes on Contributors

Leandro N Carrera is a research associate at the Public Policy Group, London School of Economics and Political Science, London UK, and a Principal at the UK Pensions Regulator. His research focuses on the politics of pension and public policy reform in Latin America and Europe, pension systems design and public sector productivity. Marina Angelaki is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Social and Educational Policy, University of Peloponnese, Corinth, Greece. Her research focuses on gender and the politics of social policy reform in Europe and Latin America.