Introduction

The History of Korea ( J. Chōsenshi, K. Chosŏnsa 朝鮮史) has long been considered a landmark in Imperial Japan’s distortion of Korean history. Published by the Society for the Compilation of Korean History ( J. Chōsenshi henshūkai, K. Chosŏnsa p’yŏnsuhoe 朝鮮史編修會; hereafter the Society), an organization of the Japanese Government General of Korea, the massive 35 volume history aimed to counter narratives unfavourable to the colonial government and justify Japanese rule.Footnote 1 Less well known are the 21 reprints of primary sources and three collections of selected samples of materials published by the Society. The two series were titled the Korean Historical Materials Collection ( J. Chōsen shiryō sōkan, K. Chosŏn saryo ch’onggan 朝鮮史料叢刊, 1932–1938, 1944) and the Korean Historical Materials Album ( J. Chōsen shiryō shūshin, K. Chosŏn saryo chipchin 朝鮮史料集眞, 1935–1936), respectively. The subjects of reproduction were diverse in media and genre: from typographic and xylographic prints to handwritten documents and painted works, and from court compilations such as Essentials of Koryŏ History (J. Kōraishi setsuyō, K. Koryŏsa chŏryo 高麗史節要) to handwritten private diaries. Three companies participated in producing the Society’s reprints: the Korean Printing Corporation (Chōsen insatsu kabushiki kaisha 朝鮮印刷株式會社) and Chikazawa Printing (Chikazawa insatsubu 近澤印刷部) in Keijō (colonial Seoul) in Korea, and Benridō 便利堂 in Kyoto, Japan. Each utilized one or more of offset lithography, collotype, and modern lead type—technologies then of relatively recent import to East Asia—to create the Society’s reprints. The facsimile reproduction of historical materials by the Society is a fruitful site to explore the application of then-newly imported printing technologies in East Asia and the history of methods of reproduction of scholarly materials, within the context of colonial knowledge production in the Japanese empire.

In this article, I examine the facsimiles of the Society to elucidate the resonances between traditional East Asian media and its methods of production with the new photomechanical and planographic printing technologies of recent import from the West that the Society utilized to great effect in its facsimiles. In so doing, I contribute to recent scholarship on the adaption of Western printing technologies in Sinographic East Asia.Footnote 2 I argue that the reasons for utilizing offset lithography, collotype, and lead type in this project, while undoubtedly connected to the prestige of modern technology and their capacity for accurate reproduction, also stemmed from perceived practical and economic concerns, as well as their fortuitous synergy with premodern printing and binding processes, and that the products of the Society came to represent the Korean past in physical form.

The comparatively new printing technologies employed enabled new economic and editorial logics, even as they resonated with older traditions of woodblock printing. Reliant on photography, both technologies could comfortably use the page image as a unit of editing, and maintain the original mise-en-page, entailing a different form of editorial labour compared with typographic technologies. Photomechanical reproduction at the level of the page allowed the Society’s historians to produce monumental prestige facsimiles and eliminated the editorial labour of transforming the text into a modern (lead) typographic edition.

Here, the nature of a page image comes into question. For the most part, ‘pages’ from traditionally bound East Asian books were a single sheet printed on one side and folded in half, creating a leaf blank on the inside but with the printed surface facing out. This Janus-faced image provided two page images when folded (the recto and verso of the leaf), and another permutation of a page when unfolded, thereby complicating the orthodox understanding, in Western scholarship, of what constitutes a ‘page’.Footnote 3 The dual nature of the folded page also allowed the Society flexibility in which page image to replicate, and they often chose to aim the camera at the unfolded page image to create their page image. This process was very similar to the recreation of an unfolded page image on a woodblock by pasting a page on the block and recurving it, a process known as ( J. honkoku, K. pŏn’gak 飜刻 or J. fukkoku, K. pokkak 覆刻). This resonance with woodblock printing allowed for the easy utilization of classic East Asian binding methods, since the replication of an unfolded page image allowed the publishers to fold and bind the reproduction in traditional style. The Society took advantage of these affordances, and many of its facsimiles combined traditional binding with state-of-the-art printing technologies.Footnote 4

The Society’s reproduction of rare materials provides an exemplary case study in the history of the facsimile, one facet of the history of ‘media and the modes of inquiry in the domains of history, arts, and letters’.Footnote 5 Even the most devoted disciple of archival materials relies on reproductions of some materials, such as photostat or microfilm. Such technologies have deep implications for scholarship and preservation, abetting scholarly inquiry, preservation, and circulation of materials while simultaneously sometimes encouraging the destruction of the original materials deemed superfluous after the creation of their copies.Footnote 6 Many documents, rare books, and artworks circulate in new editions, reproductions, or high- (or low-) quality facsimiles. There has been some examination of the role of reproductions or facsimiles of paintings in art history.Footnote 7 Others have investigated the reproduction of rare books,Footnote 8 and in the field of literature there is some discussion of what a facsimile means for an ‘edition’ of a given work or the hermeneutic implications of the physical aspects of the reproduction.Footnote 9

Less well examined is the history and theory of the facsimile as a resource for historians, and this article provides one answer to the question of what facsimiles do as a media of inquiry in the field of history. Facsimiles, in David McKitterick’s words, ‘make similar’ in order to ‘create, by means of historical allusion, if not an illusion in the minds of their readers, then at least a reminder of the age or status of the document before them’.Footnote 10 While McKitterick was referring to typographic facsimiles, the same principle applies to any attempt to ‘make similar’. George Bornstein observes that usually facsimiles ‘reproduce as many material features of the original as possible,’ even though ‘some features will always elude it’.Footnote 11 In that case, the material features themselves, not merely the typeface or mise-en-page, attempt to create the allusion/illusion. The Society’s facsimiles demonstrate an awareness that the physical form of the cover and binding held equal importance to the page layout and letterform, and sought to closely mimic the originals’ binding, even though the facsimile differed in paper stock, feel, weight, and size. The photomechanical replication of a text’s original layout on glossy modern paper merged with the use of Eastern-style binding, with hybrid Japanese and Korean features, to produce simulacra of the rare sources.Footnote 12 This process was a form of material distressing, that is, purposely making the material appear antiquated.Footnote 13 Alluding and adhering to the page layout and physical form of their originals, and further framed with bibliographical explications in modern Japanese typography to dictate understanding, these simulacra projected the illusion of a properly curated and preserved Korean past. Simultaneously, despite a limited, scholarly audience, the newfound availability of the reproductions led to each source gaining a higher profile and greater inclusion in historical study. David Lowenthal points out that ‘reactions to antiquities are mainly predetermined by reproductions’.Footnote 14 As part of a larger imperialist agenda of controlling the narrative of Korean history in order to justify Japanese rule, the facsimiles in the Korean Historical Materials Collection provided such reproductions, flanked with bodyguards of paratext, in an attempt to condition how scholars and antiquarians might react to the Korean past.

The allusion/illusion to the original carried out by facsimiles connects with the idea of the ‘aura’ suggested by Walter Benjamin, an object’s ‘unique existence at the place where it happens to be’ that is ‘embedded in the fabric of tradition’. While photomechanical reproduction cannot reproduce the aura of the original, which according to Benjamin ‘withers in the age of mechanical reproduction’,Footnote 15 the creation of facsimiles alludes to the original. By taking on the physical trappings of the original, such as binding and physical layout, facsimiles can ‘gesture’ towards the ‘aura’ of the original.Footnote 16 Reproductions may even augment the aura of the original; one scholar has argued that the famous illuminated manuscript Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry ‘has not lost but rather gained “aura” in the age of its mechanical reproducibility’.Footnote 17 Bruno Latour and Adam Lowe suggest something similar in asking ‘if no copies of the Mona Lisa existed, would we pursue it with such energy?’ They conclude that ‘the obsession [with seeking the original work of art], paradoxically, only increases as more and better copies become available and accessible’.Footnote 18 Many and varied reproductions only add to the mystique of the original, instead of detracting from it. Facsimiles then not only provide new access to sources where there was none before but build up the profile of those sources.

By highlighting the creation of facsimiles of rare materials, this article also contributes to research on colonial knowledge production by means of publishing. The Korean Historical Materials Collection was a prominent example of the reproduction of old materials in new media during the colonial era and the accumulation of knowledge about the colony. Other examples of imperial knowledge-making include the Japanese Government General of Korea’s surveys of land and investigations into customs and archaeology.Footnote 19 The colonial government, Japanese settlers—the ‘brokers of empire’—and Korean intelligentsia also endeavoured to collect and republish old Korean works of literature or historical sources.Footnote 20 The Society, charged with the collection of historical materials and the compilation of a history of the Korean peninsula, was but one actor amongst many in the creation of the study of Korean history, literature, and classics.

Colonial extraction of knowledge

The Japanese empire’s creation of a protectorate over Korea in 1905 and its annexation of the peninsula in 1910 accompanied large scale surveys of the peninsula by the colonial government and its agents. The Government General of Korea carried out numerous surveys of archaeological or historical sites to gather information about the newly annexed Korean peninsula. In 1916, under Terauchi Masatake 寺內正毅 (1852–1919; Governor General 1910–1916), the Government General created the Committee on the Investigation of Korean Antiquities (Chōsen koseki chōsa iinkai 朝鮮古蹟調査委員會). Amongst other things, this committee took charge of the investigation and preservation of historical remains. In 1933, the Government General further set up the Committee for the Preservation of Korean Treasures, Ancient Remains, Famous Places, and Natural Monuments (Chōsen sōtokufu hōmotsu koseki meishō tennen kinenbutsu hozon kai 朝鮮総督府寶物古蹟名勝天然記念物保存會).Footnote 21 It also continued to carry out the Chōsen Old Customs and Systems Surveys (Chōsen kyūkan seido chōsa 朝鮮舊慣制度調査), which began in 1906 and ended in 1937.Footnote 22 The Old Customs Surveys covered a range of topics, from law and politics to real estate, land ownership, and customary practices. These surveys, which further noted the collection, itemization, and even publication of books, law codes, gazetteers, epitaphs, and geographies, were intimately tied up in Japanese production of historical knowledge of the peninsula.Footnote 23

The Government General had allies in knowledge production: Japanese settlers. The Korean Research Association (Chōsen kenkyūkai 朝鮮研究會), an organization founded by Japanese settlers in 1908, was dedicated to the study of Korea for the purpose of bringing it under enlightened rule. Under the leadership of Aoyagi Tsunatarō 青柳綱太郎 (1877–1932), the association focused on translating and publishing old Korean books, and undertook the collection, editing, and publication of ‘extant historical documents, novels, antique manuscripts, and other statecraft literature’ from the Korean past, producing over 65,000 publications.Footnote 24 Shakuo Shunjō 釋尾春芿 (1895–?), another member of this association, founded the Society for the Publication of Korean Antique Books (Chōsen kosho kankō kai 朝鮮古書刊行會) in 1909, and went on to publish, using modern movable type, the Compendium of Various Korean Writings (Chōsen gunsho taikei 朝鮮群書大系). At 80 volumes, this series of reprinted old Korean books was the largest in the colonial period.Footnote 25 A similar series, the Korean Research Association Publications of Rare Books (Chōsen kenyūkai kosho chinsho kankō 朝鮮研究會古書珍書刊行), included the original texts of literary Sinitic works alongside Japanese translations.Footnote 26

The attempt to compile and publish the History of Korea was part of this large-scale surveying and production of knowledge. In 1915, the Government General moved the investigation bureau for the Chōsen Old Customs and Systems Surveys to the Advisory Council (Chūsūin 中樞院), a consulting body of the Government General. At the same time, it set up a division for compilation (Hensanka 編纂課) in the Advisory Council, and the creation of a ‘History of the Korean Peninsula’ (Chōsen hantōshi 朝鮮半島史) began. While the council managed to choose a structure for the text and set to work on a chronology, the compilation process lagged behind due to the constant discovery of new materials. Delays worsened with the transfer of some personnel and the deaths of others, compounding difficulties for their successors. Moreover, there was concern over the continued loss of historical materials in the chaos after annexation.Footnote 27 Recognizing these problems, the Government General halted the peninsular history project and set up a Committee for Korean History Compilation (Chōsenshi hensan iinkai 朝鮮史編纂委員會) in 1922. This committee, which included scholars such as Kuroita Katsumi, met several times from January 1923 onward to discuss the compilation of Korean history and the collection of materials. In 1925, the Government General established the Society for the Compilation of Korean History which subsequently gathered sources to use in compiling and publishing the History of Korea, with its attendant facsimiles.Footnote 28

As part of its mission, the Society carried out a massive survey to collect historical materials and documents from across the peninsula. Its purview included materials from the provinces and from the capital, and its efforts brought to light forgotten or non-circulating sources, such as the Essentials of Koryŏ History.Footnote 29 By 1938, the Society’s members charged with scouting out materials had spent some 2,800 days in the field, and collected 4,950 items.Footnote 30 Where possible, the Society made copies of the material, ultimately creating some 1,623 volumes of duplicates.Footnote 31 Photography played an important role in preserving and reproducing materials, as seen from the Society’s production of 4,511 photographs.Footnote 32 The War Diary of Admiral Yi Sunsin and Draft of the Imjin War Reports ( J. Ranchō nikki sō: Jinshin jō sō, K. Nanjung ilgi ch’o: Imjin chang ch’o 亂中日記草.壬辰狀草), though later recreated with movable type, was the first source text to be captured on camera in 1926.Footnote 33 The Society also produced a number of bibliographies and book lists about the sources it had accessed.Footnote 34

The motive for the project stemmed in part from the Government General’s need for knowledge about its newly annexed territory, for which it claimed there was no ‘accurately and clearly recorded history’.Footnote 35 But the need to establish an authoritative history of the Korean peninsula to emphasize the legitimacy and desirability of Japanese rule and to counter the influence of historical narratives subversive to its control provided a key motive. While the Government General’s position was that extant histories of the peninsula were outdated works published prior to Korea’s colonization that might inspire dreams of independence, or polemics that distorted the past. One work in the latter category drew particular attention: An Agonizing History of Korea (Han’guk t’ongsa 韓國痛史), by Pak Ŭnsik 朴殷植 (1859–1925), published in Shanghai in 1915.Footnote 36 Pak’s nationalist work, which described modern Korean history from the beginning of King Kojong’s reign until 1911, portrayed Japan unfavourably by focusing on the events that led to its annexation of Korea. Despite harsh press censorship, the Government General did not solely rely on the suppression of such works, opting instead to print its own histories of Korea to dominate the historical narrative and control nationalist sentiment by fighting books with books. By providing state-sanctioned histories, the Government General hoped to stabilize its narrative of events, and to dissuade Koreans from reading historical texts it deemed irrelevant and outmoded, or which described Korea’s annexation in negative terms.Footnote 37 The starting point for the compilation of the History of Korea was thus explicitly political, and intimately bound to the politics of Japanese control over the peninsula.Footnote 38

Through the writing of new histories, but particularly through the production of its facsimile series, the Society played a similar role in the reproduction of old texts as the Korean Research Association or the Society for the Publication of Korean Antique Books. Yet Japanese officials and settlers were not the only ones engaging in the reproduction of old texts, as Koreans competed with Japanese to produce knowledge about the nation.Footnote 39 For instance, Ch’oe Namsŏn’s 崔南善 (1890–1957) Society for Illuminating Korean Culture (Chosŏn kwangmunhoe 朝鮮光文會) also reprinted old books similar to the target sources of the Society’s facsimiles.Footnote 40 Yet many of the reprints done by the Japanese settlers or by Korean nationals were not done as facsimiles but were printed using movable type. In contrast, the Society utilized not only movable type, but the cutting-edge technologies of offset printing and collotype, which were of relatively recent import to East Asia.

Photomechanical technologies

The publications of the Society were the products of modern, global printing technologies. The main body of the History of Korea was printed with movable type (although each volume included several plates printed with collotype) and two titles in the Korean Historical Materials Collection are typographic reprints (also with the occasional plate), not facsimiles.Footnote 41 However, most of the titles in the series were reproduced photomechanically. The Society’s documents note that the majority of the facsimiles were produced using a technique called purosesu han プロセス版 (‘process plate’)Footnote 42—photolithography—noted elsewhere as ofusetto insatsu オフセット印刷, or offset printing.Footnote 43 From the time of its invention in France, lithography had supplied one method of making images and was frequently utilized in reprinting older works, ranging from manuscripts to books on handwriting to previously printed texts.Footnote 44 However, prior to the invention of photography, one had to either painstakingly copy out by hand, in reverse, the text directed onto the stone, or to use tracing paper. Once photography arrived on the scene, photolithography was soon deployed in Britain to make facsimiles of works ranging from the Domesday Book to Shakespeare’s first folio.Footnote 45 Offset printing utilizes photolithography but does not print directly onto the page. Instead, it first transfers the inked image from the plate to a rubber blanket, from which the final image is printed.Footnote 46 Like stone and plate lithography, the ‘image area’ of the plate is receptive to ink, while the ‘non-image area’ is receptive to water.Footnote 47

The principles of offset lithography were well known by the nineteenth century, but until the early twentieth century offset lithography was merely used to print on tin, metal foils, celluloid, and fabrics.Footnote 48 Printing on paper using offset lithography began with Ira Washington Rubel (1860–1908) in 1903–4, who worked on a rotary press.Footnote 49 Rubel tried his hand at business with a partner, Alexander Sherwood (?–?), collaborating with the Potter Printing Press Company of New Jersey to produce offset presses for distribution. In the end, the syndicate collapsed and the design of the offset presses went to the Potter Printing Press Company.Footnote 50 Around the same time, Alfred F. Harris and Charles C. Harris produced the first offset presses built for general commercial use.Footnote 51 Shortly afterward, Japanese printers were successfully experimenting with imported offset presses. In 1914, the Offset Printing Unlimited Company was founded in Japan, utilizing Harris offset presses, and it imported the Potter offset press the following year.Footnote 52 Soon Hamada Hatsutarō 濱田初太郎 (?–?) produced his own offset press, modelled on the Potter offset press.Footnote 53 In Japan-controlled Korea, it was mainly Japanese users who imported the latest technologies.Footnote 54 The first offset press—a Hamada machine—was introduced on the Korean peninsula in 1915 at the Chōsen Industrial Exhibition.Footnote 55 As described below, the Korean Printing Corporation was one of the first to import offset presses on the Korean peninsula.Footnote 56

The next most used printing technology was collotype (korotaipu han コロタイプ版). Collotype is ‘a screenless photomechanical process that allows high-quality prints from continuous-tone photographic negatives’, which utilizes thin plates with gelatin. When the gelatin plate is exposed to ultraviolet light under a photographic negative, it ‘becomes more hydrophobic under light areas and remains more hydrophilic under dark areas of the negative’. Just as with lithography, water and oil do not mix, and areas more exposed to light hold more ink than those less exposed, which hold more water. The plate can then be inked and printed.Footnote 57

Collotype was invented in 1855 by Alphonse-Louis Poitevin of France (1819–1882). In 1865, C. M. Tessie du Motay and C. R. Marechal used copper plate as the substrate for a gelatin collotype matrix, a process which only allowed up to 100 prints. Joseph Albert of Germany later refined the method to enable production runs of up to 1000 prints, and introduced the three-colour collotype process using continuous separation in 1874.Footnote 58 Following these innovations, collotype went on to become a major method of printing photographs and producing facsimiles of artwork, despite its high cost. In Japan, the first known instance of printing with collotype came in 1880, when the Japanese Government’s Cabinet Printing Office (Naikaku insatsukyoku 内閣印刷局) successfully used it to print an old painting.Footnote 59 Outside the Japanese government, Ogawa Kazumasa 小川一眞 (1860–1929) was a pioneer of commercializing the process, having studied the collotype process in Boston.Footnote 60 After returning to Japan, Ogawa set up his own collotype company in 1888.Footnote 61 One year previously, Hoshino Shaku 星野錫 (1855–1938), another early popularizer of collotype in Japan, travelled to New York to study artotype—an alternative name for collotype.Footnote 62 Over the next few decades, an increasing number of companies and individuals took up the collotype process in cities across Japan, including the printing company Benridō in Kyoto.Footnote 63 Collotype seems to have arrived on the Korean peninsula at the very beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 64 It was certainly used during the colonial period, since at the very least, the Korean Printing Corporation was able to print in collotype.Footnote 65

Finding facsimile-makers

Although most printing companies had stock of modern metal movable type, few on the peninsula had the requisite technologies to produce the facsimiles. The Society originally intended to print the History of Korea in Tokyo, making use of the Government General’s extensive commercial and bureaucratic networks across the peninsula and the home islands. The colonial state often employed printing companies based in Keijō, especially the Korean Book Printing Corporation (Chōsen shoseki insatsu kabushiki kaisha 朝鮮書籍印刷株式會社), which enjoyed a virtual monopoly on government publications such as textbooks.Footnote 66 For many other publications, the Government General commissioned a variety of printing companies throughout the empire, especially those in Tokyo. One Japanese entrepreneur even aimed to set up a collotype shop on the archipelago with the specific aim of catering to Government General demand.Footnote 67 The initial decision to print in Tokyo might have been based on the larger selection of companies with the requisite technology available there, or on the connections of major Japanese historians such as Kuroita Katsumi, who were charged with finding suitable printing firms in the metropole. In the end, however, the Society decided against printing the History of Korea in Tokyo as it would complicate the editing process by requiring the overseas dispatch of editors to proof the drafts, and further render comparisons with the original drafts and sources difficult.Footnote 68 Instead, the Society had the majority of its publications printed in Keijō.

Three Keijō-based companies bid (kyōsō nyūsatsu 競争入札) on the project: Chikazawa Printing, the Korean Printing Corporation, and the Korean Book Printing Corporation. Despite being the largest publishing company and the go-to printer of the Government general, the Korean Book Printing Corporation did not house the desired typeface. It thus withdrew from the competition, leaving only Chikazawa and Korean Printing to bid for the contract. In the end, the Korean Printing Corporation won the right to print the History of Korea.Footnote 69 The Korean Printing Corporation claimed the lion’s share of the Korean Historical Materials Collection and the Korean Historical Materials Album, while Chikazawa Printing only obtained one project. Some of the facsimiles of the Collection were printed by the Kyoto-based Benridō due to difficulties in borrowing sources, perhaps because institutions in Japan were reluctant to send their holdings to Korea, or because of inadequate facilities at the Korean firms.Footnote 70 Ultimately, the production of the Korean Historical Materials Collection was divided over Chikazawa Printing, the Korean Printing Corporation, and Benridō.

Each company differed in its printing technology. It is unclear whether Chikazawa Printing had the capacity to produce facsimiles, as it only printed one project using movable type (the War Diary of Admiral Yi Sunsin and Draft of the Imjin War Reports).Footnote 71 On the other hand, the Korean Printing Corporation and Benridō both engaged in offset lithography, collotype printing, and movable type printing. While the overlap was not perfect, Benridō took more of the collotype printing, while the Korean Printing Corporation oversaw most of the photolithography.

Both companies were large operations with extensive experience in facsimile reproduction. The Korean Printing Corporation was a major colonial-era printer, overshadowed only by the Korean Book Printing Corporation. Originally established in 1905 as the Japan–Korea Book Printing Corporation (Nikkan tosho insatsu kabushiki kaisha 日韓圖書印刷株式會社), it aimed to publish textbooks for ordinary schools (pot’ong hakkyo 普通學校).Footnote 72 After the annexation of Korea, the company limited its management positions to Japanese (naichijin 內地人) staff. In May 1919, following several more name changes and reorganizations, the rights to the company and its machines all went to Kosugi Kinhachi 小杉謹八 (d.u.). Over the next few years, Kosugi invested heavily in his company and in 1921, the Korean Printing Corporation imported the latest automatic offset presses from Germany.Footnote 73 While a fire reduced the factory to ash in April 1924,Footnote 74 Kosugi swiftly rebuilt, bringing in even more efficient equipment.Footnote 75 A contemporary article called the corporation the ‘pioneer of the printing and publication world in Chōsen’.Footnote 76 Possessing facilities for photolithography, collotype, gravure, and monotype,Footnote 77 it had the reputation of being the first on the peninsula to employ these technologies.Footnote 78 In 1939, the company had 45 different printing machines (including ten of the so-called hwalp’an chŏnji inswaegi 活版全紙인쇄기—full sheet typographic printers), could print up to 300 reams of paper per day, and employed some 500 people.Footnote 79 The Korean Printing Corporation’s business included movable type, lithography, all kinds of printed materials, bookbinding, and type casting.Footnote 80 It also sold Japanese and Western paper, published books, and handled related business.Footnote 81 Beyond the works commissioned by the Society, on commission by the Government General, the company also produced facsimiles of important historical sources, such as the Veritable Records (Sillok 實錄), Songs of Dragons Flying to Heaven (Yongbi ŏch’ŏn’ga 龍飛御天歌), and the Overview of the Ten Thousand Tools (Man’gi yoram 萬機要覽).Footnote 82 The Korean Printing Corporation was thus a large, capital-rich company with the appropriate technologies for facsimile making.

The other major producer of facsimiles was Benridō, founded in 1887. It originally engaged in book lending alongside publishing.Footnote 83 In 1905, the company invested in facilities for collotype printing,Footnote 84 and around the same time set up a photography studio as well, beginning its transformation into the specialized company that continues to operate in Kyoto today.Footnote 85 Starting with the production of picture postcards, Benridō began to print art photography as well, including an illustrated book of ancient art, in 1926, for what is now the National Museum of Tokyo.Footnote 86 The company scored a coup in the same year when it reproduced in collotype facsimile the Chronicles of Japan (Nihon shoki 日本書紀) on behalf of the Ministry of the Imperial Household (Kunaishō 宮内省; now the Imperial Household Agency, Kunaichō 宮内庁).Footnote 87 Benridō received another high-profile project on the preservation of cultural assets in 1935, when it was commissioned to photograph the Kondō wall paintings in Hōryūji (Hōryūji kondō hekiga 法隆寺金堂壁画), the famous Buddhist temple in Nara. The company captured the mural on glass plates, eventually finishing a full-scale replica by collotype in 1937.Footnote 88 Although a fire in 1949 destroyed the original mural, Benridō was able to recreate collotype plates using its gelatin glass plates as negatives.Footnote 89 After the Second World War, Benridō continued to play a large role in the world of facsimiles and art photography, producing numerous copies of historical and artistic works.Footnote 90

While based in Japan, Benridō also had ample experience with projects involving Korean history. In 1929, it produced the Photo Album of Holdings of the Yi Royal Family Museum (Ri Ōke Hakubutsukan shozōhin shashinchō 李王家博物館所藏品寫真帖).Footnote 91 In 1934—the same year it published the fourth instalment of the Korean Historical Materials Collection for the Society—Benridō published Tomb of the Painted Basket (Rakurō saikyōzuka 樂浪彩篋冢), and in the following year it added the Plates of Old Rooftiles of Lelang and Koguryŏ (Rakurō oyobi Kōkuri Kogawara zufu 楽浪及高句麗古瓦圖譜) to its output.Footnote 92 In 1937, it printed An Investigation into the Carving of the Supplement to the Koryŏ Buddhist Canon and Research on Ŭich’ŏn’s Philosophy and Compilation Work (Kōrai zokuzō chōzō kō narabi ni Giten no shisō oyobi hensan jigyō ni kansuru kenkyū, 高麗續藏雕造攷並に義天の思想及び編纂事業に關する硏究).Footnote 93 Benridō, like the Korean Printing Corporation, had the requisite technologies, experience, and connections to produce facsimiles for the sake of the Society.

Reproducing the Janus-faced page image

While the images in the Korean Historical Materials Album were all reproduced using collotype, the 21 facsimiles of the Korean Historical Materials Collection were printed using offset photolithography, collotype, and movable type. The subjects of the Society’s facsimiles were products of three traditional technologies of the word: woodblock, (Chosŏn-era) movable type, and manuscript. A fortuitous affinity that played a role in effective reproduction may be discerned in the choice of new technologies in reproducing old books or materials. Christopher Reed observes resonances between woodblock printing and lithography, noting that of all the Western printing technologies adopted by Chinese printers, lithography first found favour due to the low capital investment it required, the ‘aesthetic appeal’ of the printed product, and the ‘limited changes in publishing outlook, particularly with regard to industrialization and textual aesthetics’ it permitted. Lithography allowed publishers to cater to the high demand for reprints of works needed by candidates taking the civil service examination, and ‘preserve[d] the calligraphic component of original texts’ in a manner akin to woodblock printing.Footnote 94 This last observation applies equally well to collotype or offset lithography and deserves elaboration.

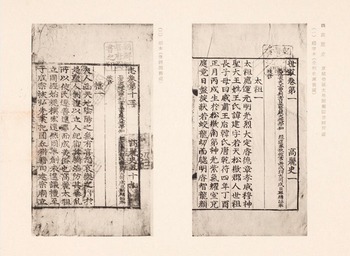

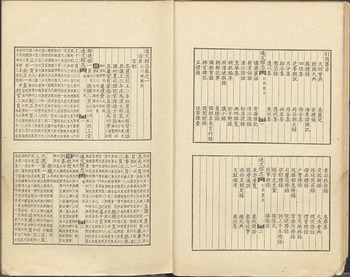

Woodblocks enabled the easy reproduction of handwriting. One could simply take a handwritten document, book, or piece of calligraphy, paste it in reverse on the block, and carve it out.Footnote 95 Alternately, one could also unbind a book, and paste its pages on woodblocks to be carved into a new set of blocks for its reproduction creating a recarved edition. Even if the original pages are destroyed, the new blocks can reprint the book many times over. As it created a reproduction at the level of the page image, a recarved edition captured the mise-en-page of its model text. For instance, the 1613 edition of the History of Koryŏ (Koryŏsa 高麗史) is a recarved edition of the fifteenth century edition, and mirrored the nine-line, 17-character layout of the original. The page images of each edition of the History of Koryŏ are included in the Korean Historical Materials Album, as shown in Figure 1. Recarvings could even capture the idiosyncrasies of their source. For instance, a woodblock of the Royal Record of Gifts (Ŏjŏng insŏ rok 御定人瑞錄) held by Kyujanggak Library at Seoul National University, South Korea, includes on its surface the shape of a seal stamped on after the original edition’s publication.Footnote 96 However, since minor changes occur in the process of carving, recarvings are not carbon copies of their originals.Footnote 97

Figure 1. The History of Koryŏ from the Korean Historical Materials Album. On the right is the movable type edition of the fifteenth century. On the left is a print of the seventeenth century woodblock edition. The pages are drawn from different volumes of different editions of the History of Koryŏ, however note the shared nine-line, 17-character layout.

Lithography, offset or otherwise, and collotype display similar features. At its most basic, one can directly write or draw on a lithographic stone to create the image or text to be printed, and the medium allows for great flexibility in visual style. This includes the reproduction of page images, and printers used lithography to reprint old books from the craft’s earliest days.Footnote 98 In an echo of recarved editions, this use of lithography occasionally extended to the point of destroying or damaging books to create the facsimiles. For instance, the original document might be ‘damped with gum water and then charged with lithographic printing ink so that the image could be transferred to stone or a metal plate’.Footnote 99 The wet-transfer method, where wet paper or fabric was pressed against the original, created the mirror image used with the engraving plate for the facsimile.Footnote 100 Exposure to moisture inevitably damaged the original, although the wet-transfer method was less destructive than sacrificing the entire page for recarving.

In another affinity between woodblocks and lithographs, the recarved woodblock edition’s unit of reproduction was the page image, where one face of the block most often corresponds to a printed face of an unfolded folio. Likewise, the wet-transfer process also takes the page image as its unit of editing. The page image as a unit of reproduction further resonates with photomechanical means of production. Photography, in its interactions with printed and printing media, allows for a similar form of reproduction also focused on the page or folio. Taking photographs creates plates, either dry plates or film negatives, from which images can be reproduced. When the camera is focused on a single page or folio, the resultant film negative or dry plate is similar to a woodblock or a lithographic stone. Without substantial alteration, the reproduction process maintains the layout of the original and any subsequent markings on the reproductive medium. However, instead of carving or drawing, the images are reproduced by the interaction of chemicals and light, preventing the resultant negatives from being used to print directly. To be reproduced en masse, these images must interface with other media, such as woodblock, lithography, or collotype.Footnote 101 Photography thus provides an alternate method of transferring information from one medium to another.

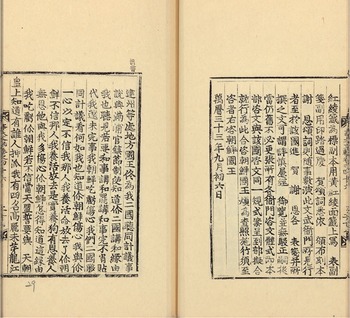

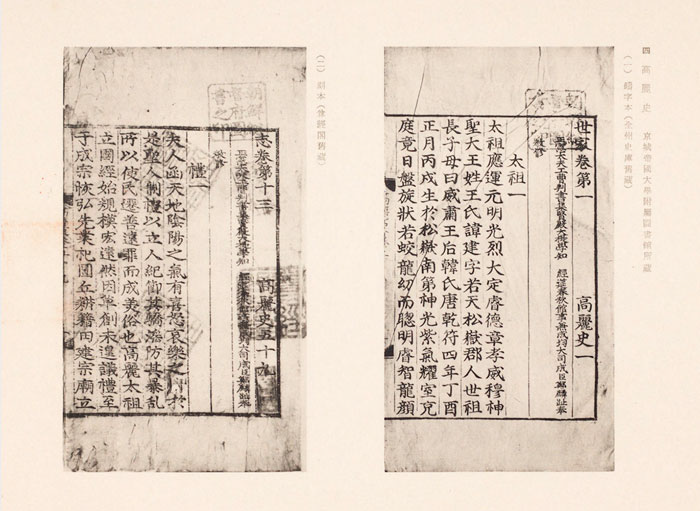

The case of East Asia complicates our conception of the page image. With Eastern-style binding, a folio or a leaf is a single sheet of paper, printed on one side and folded in half so the text remains on the outside. The folded pages are then bound at the open edge, so the open edges become the spine (and are closed by the binding) and the folded edges of the pages become the fore edge. When the book is bound and its leaves folded, the page image is equivalent to the first half of the unfolded page (see Figure 2). When viewed unbound and unfolded, the page image is a full leaf, containing double the amount of content as a single page (see Figure 3).

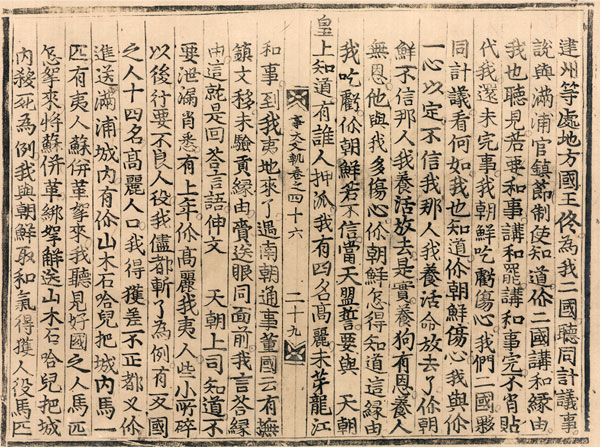

Figure 2. Folded page image of the Document Trail of Serving the Great (K. Sadae mun’gwe, J. Jidai bunki 事大文軌).

Figure 3. Document Trail of Serving the Great. Unfolded page image. This image is of kwŏn 46, p. 29ab, and corresponds to the left page of Figure 2.

What exactly might be considered a proper page image thus depends on the folding and unfolding of paper.Footnote 102 Folded, a sheet takes one form of a page image, and transforms into another when unfolded, becoming a ‘page’ image with no obvious analogue in the Western tradition. When collecting materials, the Society frequently aimed its cameras at the folded page image, or the open book, and kept the binding intact. However, when using photography to reproduce books, it took the unfolded page image as the unit of editorial reproduction, rather than the folded page image, just as if it was producing a recarved edition. In turn, this allowed its members to easily rebind the books in traditional style. Printing an unfolded page and then refolding it to bind it in traditional style continued to tap the synergy between premodern and modern media.

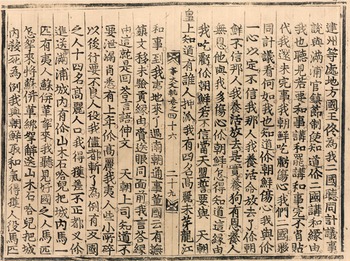

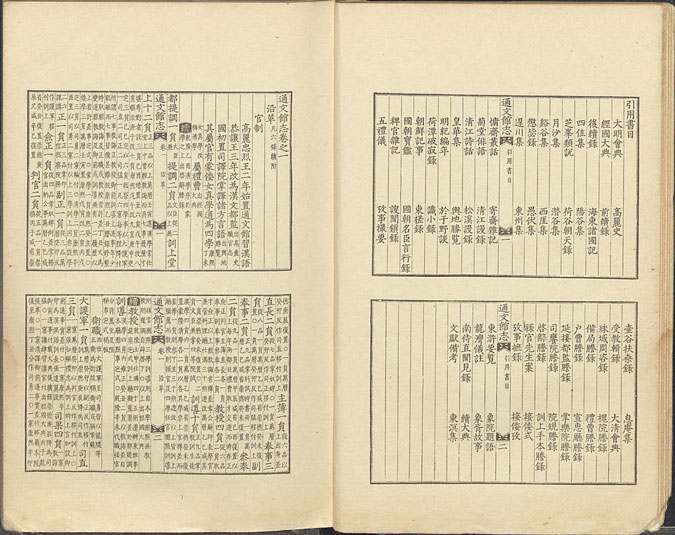

Yet to bind in the traditional style was a deliberate choice. Sometimes the unfolded page image was reproduced only to remain unfolded in its new medium. For instance, in the twenty-first title in the series, the 1944 reproduction of the Compendium of the Interpreter’s Bureau ( J. Tsūbunkan shi, K. T’ongmun’gwan chi 通文館志), the Society printed two unfolded folios on a single page (see Figure 4), using shrunken unfolded page images to save space. This was and is a common method of ‘facsimile’ making in modern China, Japan, and Korea, and the two unfolded pages on a single page is now a ubiquitous East Asian facsimile aesthetic that dominates much scholarly reproduction.

Figure 4. Compendium of the Interpreter’s Bureau. Unfolded page images on a single page.

The least utilized technology was movable type. However, the Society permitted the typographic reproduction of the War Diary of Admiral Yi Sunsin and Draft of the Imjin War Reports and the The Handwritten Diary of Yu Hŭich’un ( J. Bigan nikki sō, K. Miam ilgi ch’o 眉巖日記草), both handwritten sources. Why were these two sources reprinted using typography, when all the other sources—including other manuscripts such as Yu Sŏngnyong’s 柳成龍 (1542–1607) A Draft of the Book of Corrections (J. Sōhon chōhiroku, K. Ch’obon chingbirok 草本懲毖錄) and Miscellaneous Records from After the War ( J. Rango zatsuroku, K. Nanhu chamnok 亂後雜錄)—were recreated by photomechanical means? While it was entirely possible to create a photofacsimile of either manuscript, the Society opted not to. Perhaps facsimile technologies might have been unsuitable for the scribbled handwriting of the texts.Footnote 103 Yet technological limitations do not seem to have played any role, as the Society photographed both sources, which provided sufficient clarity in either case.Footnote 104 Both even included some high-quality plates inserted within each work.Footnote 105 One possibility is that the Society elected to print using movable type because only those highly proficient in reading calligraphy would be equipped to use a facsimile of the manuscript, whereas a printed version could reach a broader range of readers. However, the Society reproduced other calligraphic works, so it is more likely that the reason was due to the unpolished handwriting and page layout in these two works—both were diaries, not letters or manuscript editions.

Editing and unediting

Despite such resonances between traditional printing and binding methods and their modern counterparts, I do not argue that the Society’s members selected printing technologies such as photolithography because of some innate cultural tendency towards woodblock. While the interface between the affordances of different technologies and binding strategies played a role in replication, there is no evidence that the Society consciously drew parallels between woodblock and photolithography when it promoted the use of collotype or offset lithography. Instead, two benefits that photomechanical reproduction offered were the reduction of editorial labour and the maintenance of the original mise-en-page.

Nakamura Hidetaka 中村榮孝 (1902–1984), who worked on the compilation of the History of Korea as a member of the Society, wrote that the reason for publishing using photomechanical processes was to minimize the amount of effort required for compiling and editing.Footnote 106 Nakamura also praised historians Sin Sŏkho 申奭鎬 (1904–1981) for editing the War Diary of Admiral Yi Sunsin and Draft of the Imjin War Reports, and Kuroda Shōzō 黑田省三 for overseeing the Handwritten Diary of Yu Hŭich’un.Footnote 107 Both works were produced with movable type, implying a considerable degree of effort involved. Although the cost of photomechanical printing may have equalled or even exceeded that of printing with movable type, its ability to copy pages in their entirety required less editorial exertion. Photofacsimiles could be a labour-saving technology that removed the task of editing a work character by character, as well as the need to make and double-check drafts to be sent to a printing company.

Randall McLeod proposes a similar idea in discussing facsimiles of Shakespeare’s first folio. Suggesting that ‘editing is consonant with the means of physical reproduction, and may be influenced by it’, he argues that a particular editorial style grew up around movable type, which was the dominant mode of printing in early modern Europe. According to McLeod, ‘textual transmission … involved an approximately linear processing of the text’, and ‘editors themselves saw transmission as an occasion for re-composition’.Footnote 108 Yet, while movable type as a technology enabled and even encouraged the re-creation of a text, McLeod points out that photofacsimiles of Shakespeare bypassed the work of composition and editing; photography enabled direct reproduction and eliminated the need for copying by movable type. In his words, this served ‘to unedit Shakespeare’, by cutting out the compositorial and editorial middlemen in the process of facsimile production.Footnote 109

There is a clear parallel between McLeod’s argument about ‘unediting’ Shakespeare and Nakamura’s claim that the Society used photofacsimiles to reduce editorial labour. McLeod is referring to an editorial ecosystem where a substantial tradition had been built up around a particular text, and which contained a certain amount of orthographic slippage, or what he terms ‘irrelevant improvements’. The advent of photofacsimiles sidelined this tradition.Footnote 110 In the case of the Society’s facsimiles, their sources were often rare or unique documents with no built-up traditions of reproduction to unedit. Works such as the Draft of the Book of Corrections did have different versions in circulation, and the publication of these facsimiles would have allowed scholars to access original drafts for comparison with variant printed editions. While cases like these tentatively offer a version of ‘unediting’, texts such as the Essentials of Koryŏ History had been out of circulation for centuries and possessed no editorial tradition to undo. Nonetheless, McLeod and Nakamura both seem to suggest that photography allowed the circumvention of editing, or at least a kind thereof.

Even though photofacsimiles streamlined the linear process of letter-by-letter editing and composition, they demanded a different kind of editing in turn, requiring the selection of factors including the camera distance and angle, colour, and the size of the reproduced page. They also needed another unit of editing. Different photofacsimile editions of Shakespeare took either the page or the line as their unit of editing, selecting the most desired passage or page and creating composite facsimiles.Footnote 111 This resulted in a layering of editorial practices, with a newer edit of the facsimile overlaid on an earlier edit of the original text.Footnote 112 Given the rarity of the works chosen for reproduction, the Society often lacked the luxury of selecting lines or pages to create an ideal text. However, in the case of the Korean Historical Materials Collection, entire volumes were sometimes culled from a different edition, as is the case with the Essentials of Koryŏ History.

The Society’s 1932 edition of the Essentials, printed by the Korean Printing Corporation was a facsimile of the 23-volume, sixteenth-century Ŭrhae type (ŭrhae cha 乙亥字) edition presently housed at the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies.Footnote 113 At the time, this was the most complete copy known. However, fascicles five, six, and 18 were missing, and some of its volumes had suffered fire damage, which obscured or eliminated entire lines of text in places. In addition, fascicle 19 came from the 1453 Kabin type (kabin cha 甲寅字) edition, making it a composite set comprising two editions. After the publication of this set, researchers discovered a complete 1453 kabin type edition at the Hōsa Bunko in Nagoya.Footnote 114 Instead of reprinting it in its entirety, the Society instead opted to supplement its original publication by having Benridō reproduce the three missing fascicles and the prefaces, table of contents, list of compilers, and postface from the newly discovered copy in 1938. Combined, the 1932 and 1938 publications together make a composite copy of the Essentials that is almost complete, excepting the few passages destroyed by fire. But by drawing on volumes from both the 1453 and 1542 editions, this composite copy—printed by two different companies—exemplifies the kind of editing that goes into photomechanical reproduction.

At the same time, even if photofacsimiles enabled one to ‘unedit’, or reduced editorial labour by allowing for the wholesale ‘editing’ by the page image or the entire volume, they did not entail a total lack of scholarly effort. The facsimiles of the Society came with ‘a whole rash of new material not part of the original’.Footnote 115 This ranged from basic elements such as the editor’s name, or qualifying statements about the work being a reproduction, to prefaces and afterwords. In other words, editing created paratexts in lieu of re-creating the text.Footnote 116 The Society’s facsimiles were no exception, bringing with them colophons, explanatory notes, and notes on the original’s size.Footnote 117 Some cases further included typographically printed transcriptions of difficult to read calligraphy.Footnote 118 Given the creation of additional materials and that the text was sometimes transcribed into movable type print, it is an open question as to how much labour was in fact saved.

It seems likely that in addition to a perceived reduction in editorial labour, a second concern that affected the Society’s choice of reproduction media was linked to the rarity of the works selected for copying and a focus on maintaining the original mise-en-page. The Society took preservation of historical materials as one of its objectives and used different methods to achieve this aim: transcribing on special ten-line 20-character paper ( J. tōsha, K. tŭngsa 謄寫); tracing ( J. eisha, K. yŏngsa 影寫); photographing ( J. satsuei, K. ch’waryŏng 撮影); rubbing ( J. takuei, K. t’agyŏng 拓影); and copying ( J. mosha, K. mosa 模寫).Footnote 119 Of the various methods discussed above, transcription alone did not replicate the original mise-en-page; tracing, copying, rubbing, and photography could all capture the page layout of the target source. The Society’s choice of photomechanical techniques suggests it was concerned with preserving the format of the original materials. Photomechanical media gave a better representation of the source text’s physical features, and only in cases where the reproduction of the page image was too messy or incoherent did the Society resort to movable type.

Allusion for illusion

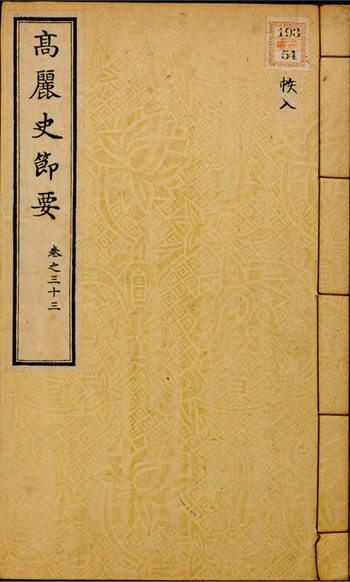

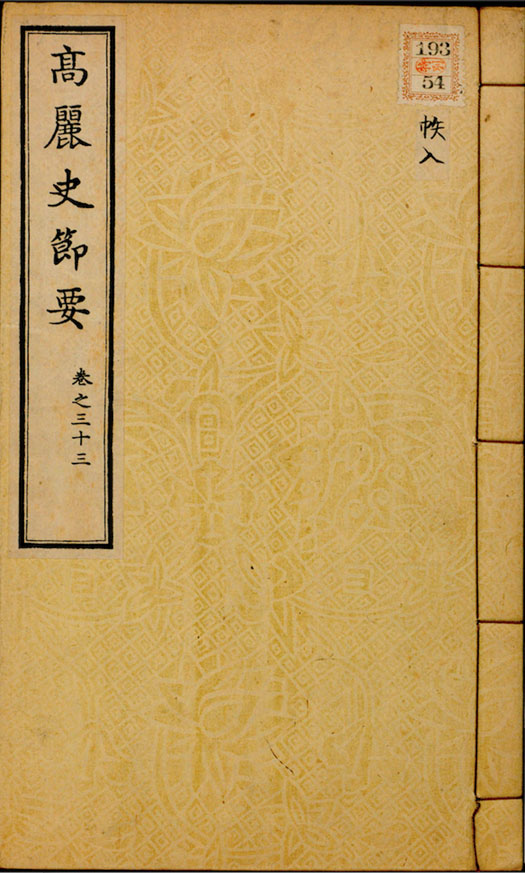

Beyond producing facsimiles at the level of the page image, on many occasions the Society also paid homage to the binding and covers of the originals, utilizing faux-traditional covers and traditional binding to create, in McKitterick’s words, an historical allusion for the sake of producing an illusion in the minds of readers. Taking the example of the Essentials of Koryŏ History again, the facsimile edition was bound in the traditional style (each page folded in half with the text on the outside and bound at the open edge). Five holes for the thread allowed five-hole binding, a common, although not universal, technique in Korea (in Japan and China, four holes were more frequent). The pages are protected by a thick cream-coloured cover with flower-pattern embossing, another feature common to premodern Korean editions.Footnote 120 The external appearance of the work greatly resembles an old edition from the former dynasty (Figure 5). The employment of traditional binding and flower-pattern covers serves the same function as maintaining the traditional mise-en-page via photomechanical means: to conjure up an illusion or a reminder of the original source’s provenance. In some sense, this phenomenon is akin to the concept of ‘distressed genre’,Footnote 121 but rather than a literary or discursive form it is a bibliographic one, where the physical form of the book is rendered antiquated to mimic the style of an older layout and binding. Modern photomechanical processes, which replicated the original layout of the Essentials, combined with Eastern-style binding with both Japanese and Korean techniques, to produce a simulacrum that alluded to the original.

Figure 5. The cover of the facsimile of the Essentials of Koryŏ History. Contrast has been increased from the original to highlight the pattern.

Yet as with all facsimiles, those commissioned by the Society fall short of being perfect reproductions.Footnote 122 The binding thread of the facsimile Essentials is very thin and fine, suggesting its modern manufacture. Inside the cover, the thin paper pages are smooth and glossy, quite different from the original, thicker, paper; this type of paper was probably needed for offset printing. Moreover, the page and layout sizes have been scaled down in comparison to the original. The facsimile’s size is 28.3 by 17 centimetres, compared with the Essentials’ original size of about 33.5 by 21 centimetres. The outer square of the printed area (kwanggwak 匡郭) on the original is 24.7 by 16.4 centimetres (or 25.5 by 17.5, according to the information in the Society’s edition). In contrast, the facsimile photographs’ printed area measures 17.5 by 11.5 centimetres. Colour also varies, with seals of ownership, for instance, transformed to a uniform black from their original red. Finally, at the corners of the spine, called the headcap and tail, there are small reinforcements with a kind of cloth, as shown in Figure 6. Known as kadogire 角裂, these reinforcements are more common in Japanese bookbinding than in Korean. The Society’s facsimiles are hybrid, not just because they are produced by globally circulating technologies backed by Japanese capital, but because they bring together elements of traditional Korean and Japanese binding and use photography to replicate the traditional layout.

Figure 6. Kadogire on Chosŏn Rhapsody.

This pattern holds true for the majority of the other facsimiles, although the exact characteristics of each vary and there is some difference between offset lithography and collotype productions. Most of the Society’s facsimiles printed with offset lithography followed a similar pattern to the Essentials, with some divergence depending on the work: four-hole binding instead of five, unadorned lighter paper for the cover, and so on. Some do not exhibit kadokire. Of the 15 items produced with photolithography, a number match the format of the Essentials and its supplement: the Records of Countries across the Sea to the East ( J. Kaitō shokokuki, K. Haedong chegukki 海東諸國紀), Records of the Military ( J. Gunmon tōroku, K. Kunmun tŭngnok 軍門謄錄), Miscellaneous Records from After the War, Remaining Volumes of the Military Organization at Garrison-command ( J. Chinkan kanpei hengo satsu zankan, K. Chin’gwan gwanbyŏng p’yŏno ch’aek chan’gwŏn 鎭管官兵編伍冊殘卷), and Records of Sosu Sŏwon ( J. Shōshū shoin tōroku, K. Sosu sŏwŏn tŭngnok 紹修書院謄錄) are all bound using five holes and a thick, patterned cover with the protective kadogire. The facsimiles of Victory Strategy ( J. Seishō hōryaku, K. Chesŭng pangnyak 制勝方略) and Chosŏn Rhapsody ( J. Chōsen fu, K. Chosŏn pu 朝鮮賦) have the same thick cover and kadogire, but only four holes. The Document Trail of Serving the Great ( J. Jidai bunki, K. Sadae mun’gwe 事大文軌), Collected Works of Kwŏn Kŭn ( J. Yōson shū, K. Yangch’on chip 陽村集), the Collected Works of Sin Sukchu ( J. Hokansai shū, K. Pohanchae chip 保閑齋集), and the Continued Precious Mirror of Military Pacification ( J. Zoku butei hōkan, K. Sok mujŏng pogam 續武定寶鑑) all use lighter, thinner paper for the binding and four holes for the thread, without kadogire. The Compendium of the Interpreter’s Bureau mentioned above also follows this binding style but is printed two unfolded folios to the page. Finally, the Sō Family Documents on Deployment to Chosŏn ( J. Sō-ke Chōsenjin monjo, K. Chongga chosŏn chin munsŏ 宗家朝鮮陣文書) is a scroll rather than a codex and stored in a box. With the exception of the Sō Family Documents, for the most part offset productions adhere to a more standard book format with slight variations in cover, binding technique, and the use of protective kadogire.

Collotype productions show more variation. Four titles in the Korean Historical Materials Collection—the Album of Letters of Chinese Generals, Album of Poetry of Chinese Generals ( J. Tōshō shochō, Tōshō shigachō, K. Tangjang sŏch’ŏp, Tangjang sihwach’ŏp 唐將書帖, 唐將詩畵帖), Edicts of the Royal Secretariat (J. Seiin dengyō, K. Chŏngwŏn chŏn’gyo 政院傳敎), A Draft of The Book of Corrections, and Painting of the 1711 Korean Embassy Entering the City ( J. Shōtoku Chōsen shinshi tojō gyōretsuzu, K. Chŏngdŏk chosŏn shinsa tŭngsŏng haengnyŏlto 正德朝鮮信使登城行列圖)—were printed with collotype. The facsimile of Yu Sŏngnyong’s A Draft of The Book of Corrections is bound in Eastern style with five hole binding, but the cover is dark, thin paper, rather than the thicker, cream-coloured cover used for many of the other facsimiles. Edicts of the Royal Secretariat and the Album of Letters of Chinese Generals, Album of Poetry of Chinese Generals both use double leaves as a medium, but with the exception of the poetry collection, which is sewn together, the pages are bound with some form of adhesive rather than thread. The Painting of the 1711 Korean Embassy Entering the City is a boxed scroll. Additionally, all three collections of looseleaf plates of the Korean Historical Materials Album are collotype productions, as are the plates included in the main volumes of the History of Korea. Perhaps because the subject matter was art, letters, decrees, or drafts of a work and the synergy between modern and premodern printing and binding methods was less formative, although the printers did endeavour to reflect to some degree the original source.

Two of the Korean Historical Materials Collection were typographic. The War Diary of Admiral Yi Sunsin and Draft of the Imjin War Reports, The Handwritten Diary of Yu Hŭich’un were printed with movable type and were bound in Western-style binding. They are thus not facsimiles as there is no semblance of the original and the binding is modern; the only reference to the sources is textual, with the exception of occasional inserted plates. One cannot even say that it is a type-facsimile or period printing—a reprint with binding, format, and typeface similar to the original—as the modern fonts bear no resemblance to either the calligraphy of the original, or to any premodern font.Footnote 123 The typographic reprints, and the main body of the History of Korea itself, generate allusions that differ from the ‘distressed’ facsimiles. The History of Korea, printed in Japanese with movable type and bound in quires with Western-style leather binding sporting gilded edges on top, has a very different feel from the facsimiles produced in mock traditional style. In this, the binding format is no less important than the use of modern type.Footnote 124 As a new production, it has no original to reference, yet its physical format still has allusions to particular traditions. Here the binding and the printing alludes to modern conventions of scholarship, while drawing on traditions of history writing and modern historiography rather than invoking a traditional or Orientalized past.

The Society’s facsimiles, when viewed against the backdrop of their modern typographic paratexts and the History of Korea as a whole, create the image of a properly curated and preserved past. The contrast between the typographic, modern-bound main volumes of the History of Korea and the photomechanical yet (mostly) traditionally bound Korean Historical Materials Collection further emphasizes the historical, antiquated feel of the facsimile series. Similarly, all prefaces or explanations ( J. kaisetsu, K. haesŏl 解說) to the Korean Historical Materials Collection were printed in Japanese typography, also reinforcing this juxtaposition of modern and ancient. Paratext, typography, and binding all frame how a reader should approach each source; the reproductions predetermine the reactions of readers. Given the rarity of the originals, these facsimiles were in many cases the first artefacts representing the sources that scholars would have encountered, and in all their mediated glory conditioned how those same scholars would see the Korean past.

Expanding the potential audience

By increasing the number of copies in circulation, the Essentials and the other facsimiles published by the Society saw a dramatic increase in their profile, a process similar to the gain of an ‘aura’ for their original due to the creation of copies discussed in the introduction. The Society appears to have produced 300 copies per title, based on the stamp in red ink on the page of the publisher’s colophon of many facsimiles.Footnote 125 Three hundred copies revitalized the circulation of many sources and others on the map in numbers not seen before. A good number of the sources were unique, either manuscript diaries or ledgers, letters, or works of art, and a print run of 300 was unprecedented. Even in the case of printed works, it is unlikely that their Chosŏn-era circulation reached 300 at any one point. For instance, in the case of the Essentials of Koryŏ History, the work was only printed twice in the early Chosŏn and no complete extant copy remained on the peninsula in the early twentieth century. Three hundred copies of the most complete copy of the Essentials, followed by 300 copies of the remaining volumes, ensured that the Society’s composite facsimile of the Essentials was the only edition accessible to scholars who could not make the journey to the original’s holding institution. Beyond expanding the circulation of the titles in question, the facsimiles also were the only editions produced until the creation of new facsimiles after liberation.

Increasing the prominence of these sources in and of itself can be seen as constructing a new narrative of Korean history, one that gravitated towards Japan. The selection of the sources for facsimile reproduction reflected to some extent the preoccupations of their Japanese compilers, with about two-thirds connected directly or indirectly to Korea’s relations with Japan or Korea’s foreign relations at large. Eight (38 per cent) of the sources concerned the late sixteenth century Japanese invasions of the Korean peninsula, or figures who played a prominent role in that war, such as chief state councillor Yu Sŏngnyong and admiral Yi Sunsin 李舜臣 (1545–1598): Records of the Military, Album of Letters of Chinese Generals and Album of Poetry of Chinese Generals, Edicts of the Royal Secretariat, War Diary of Admiral Yi Sunsin and Draft of the Imjin War Reports, Miscellaneous Records from After the War, Remaining Volumes of the Military Organization at Garrison-command, A Draft of The Book of Corrections, Sō Family Documents on Deployment to Chosŏn. Six (29 per cent) were related more broadly to Korean diplomatic history: Document Trail of Serving the Great, Victory Strategy, Chosŏn Rhapsody, Continued Precious Mirror of Military Pacification, Painting of the 1711 Korean Embassy Entering the City, and Compendium of the Interpreter’s Bureau. By singling out these sources for special treatment, the Society emphasized its vision of history; the publication of books itself reified a particular version of the past.

Jun Uchida observes of state-sponsored Japanese settler publications of old Korean books that ‘the goal was nothing less than engineering collective amnesia’.Footnote 126 It is tempting to conclude that the production of the History of Korea and its facsimiles by the Society’s colonial bureaucrat-historians had the same objective. However, bringing into prominence selected texts may have supported a particular narrative but rather than engendering amnesia, it encouraged selective historical memory; as a colonial project the aim was not to forget, but to remember for the sake of the empire. This became a double-edged sword, as controlling the past through historical compilation meant emphasizing the past, and controlling Korean history meant emphasizing Korean history, in however distorted a fashion. The Society’s endeavour thus revealed a contradiction in the colonizer’s compilation of official history, as one of the project’s former participants later noted: while the compilation was an attempt at control, it had the opposite effect of resurrecting and increasing awareness of Korean history.Footnote 127 If the History of Korea elevated the status of Korean history, then the new abundance of facsimiles also elevated the status of selected sources.

However, this elevation was limited in its audience. Despite the Society’s official declaration to fight history with history, neither the History of Korea nor the facsimiles were aimed a general Korean readership. Contemporary newspapers occasionally mention the Society and its project. The Daily News (Maeil sinbo), the mouthpiece of the Government General, noted the beginning of the publication of the first of the facsimiles with a short article, pointing to the significance of having printed the Essentials of Koryŏ History and hailing the benefits to academia and researchers working on Korean history.Footnote 128 The Daily News also celebrated the completion of the Society’s project as an ‘inextinguishable golden tower’, and emphasized contributions to global scholarship and research on Korea made by the History of Korea, the Korean Historical Materials Collection, and the Korean Historical Materials Album, something the Korea Daily (Chosŏn ilbo) agreed with.Footnote 129 Only after that did the Daily News emphasize the importance for correcting false views of the nation and historical truth.Footnote 130 While the political dimensions of the project still remained, the assumption was a scholarly audience with knowledge of Japanese, not a popular one, and the publications ended up in universities, libraries, and the homes of specialist scholars. While a full investigation into the reception of the facsimile reproductions of the Society, their impact on later scholarship, and the creation of subsequent reproductions awaits further research, the readership of the history and the facsimile series was thus not the wider public, although the books were likely more accessible than the facsimiles of the Veritable Records, of which only 30 copies were printed.Footnote 131

Conclusion

In the 1930s, the Society for the Compilation of Korean History desired to supplement its politically motivated History of Korea by reprinting historical materials that had gone out of circulation. To that end, it selected xylographic, typographic, and chirographic products of the defunct Chosŏn dynasty’s book ecology and directed several printing companies to produce facsimiles using offset lithography and collotype. These relatively new photomechanical technologies boasted a fortuitous resonance with the traditional methods of recarving woodblocks, enabling an editorial logic where the unit of reproduction was the page image rather than the text itself, although the page image itself was divergent, as pages from traditionally bound books provided one image when unfolded, and another when unfolded, in contrast to pages in books with Western-style binding. The fact that the editorial unit, as the unit of reproduction, frequently was the page image of the unfolded folio, meant that the newly printed duplicate page could easily be folded and bound with traditional East Asian side-stitched binding. Replicating not only a source’s layout but also its binding methods was crucial to producing an allusion to tradition and the illusion of a facsimile’s verisimilitude.

The full effect of using traditional binding with a photofacsimile’s pages created simulacra of the original works and resulted in reproductions dedicated to matching the formats of their originals. Different combinations of printing methods and binding methods brought about very different products, depending on whether the process mixed Western binding with photomechanical or typographic technologies, or traditional binding with modern lead type or planographic printing. It was primarily the offset lithography facsimiles that ended up in Eastern-style binding. The offset lithography facsimiles were most often of printed or written books from the Chosŏn dynasty, while collotype facsimiles usually focused on painting, calligraphy, and handwriting, with the latter’s original media not always bound in the Eastern style. The collotype reproductions especially vary, taking a loose-leaf Western style, or Eastern style but the spine is pasted together with no thread. Movable type reprints are bound in Western binding, and allude to modern, objective scholarship, rather than the premodern past.

These simulacra were deployed to buttress the Government General’s narrative of Korea’s past. Created at the intersection of technologies both old and new, commercial and academic enterprise, as well as historiography and politics, the facsimile series served as physical symbols of the Government General’s technological and intellectual prowess, along with the legitimacy of its colonizing mission. At the same time, the choice of titles was influenced by the interests of the Society and reflected a focus on Korea’s diplomacy and the Japanese invasions of the late sixteenth century. The facsimiles further represented a large shift in the availability of selected sources, as some 20 works, art pieces, and archival materials that had seen no circulation or limited circulation suddenly appeared on library shelves. This increase in availability correspondingly increased the potential access and use of these sources, at least for those in the broader scholarly community. The facsimiles, as part of a prestigious politico-historical project, further began to accumulate cultural status and readership, changing the parameters of what constituted the appropriate source base for the investigation of Korean history.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sun Joo Kim, Ann Blair, Si Nae Park, and Yuting Dong for their comments on different versions of this article. Sungik Yang has my immense gratitude for examining some copies of the facsimiles during the final revisions process when I could not. I am also indebted to the insightful critiques of the anonymous reviewers; their aid has immensely improved this article. An early version of this research appeared at the conference ‘Before and Beyond Typography’, organized by Andrew Amstutz and Thomas Mullaney, and hosted virtually by the Stanford Humanities Center over the course of summer 2020. This research was supported by the Korea Foundation, the Korea Institute of Harvard University, and the Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

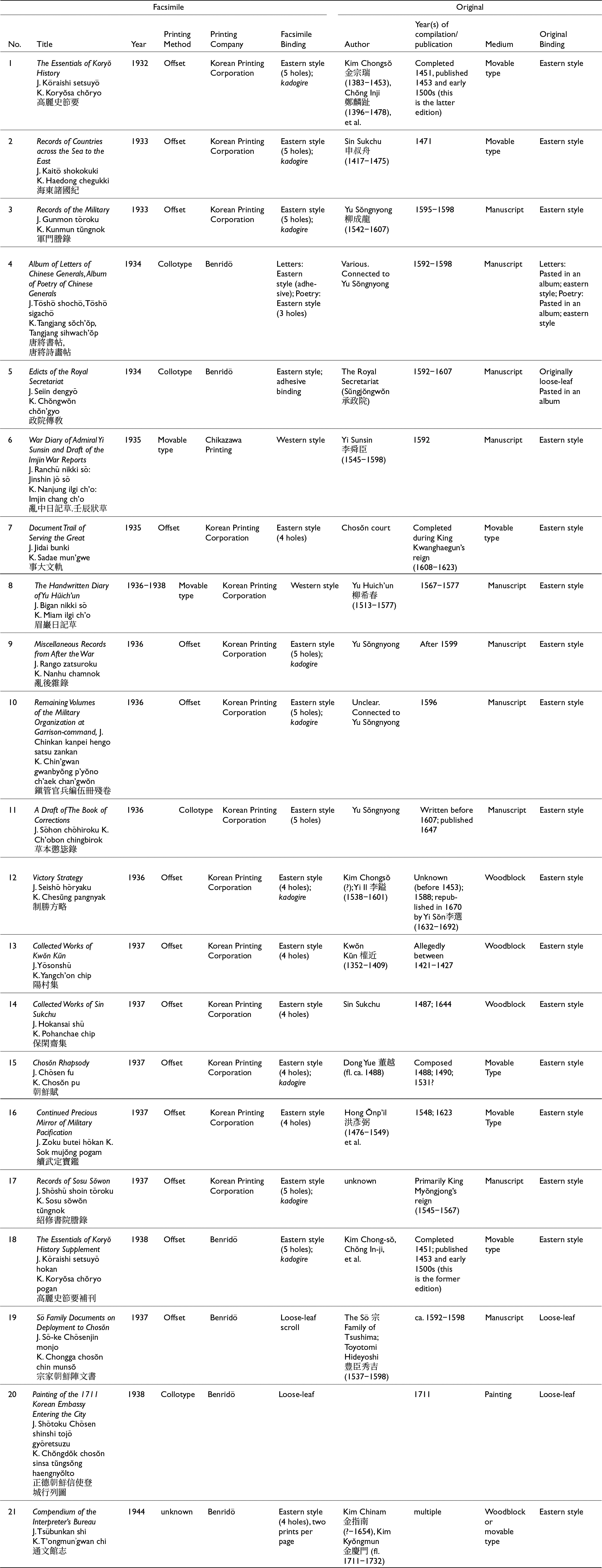

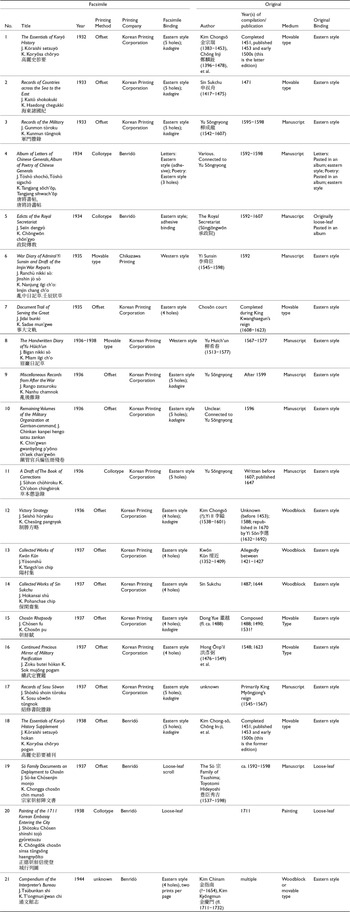

Appendix

Table 1: The Korean Historical Materials Collection ( J. Chōsen shiryō sōkan, K. Chosŏnsa saryo ch’onggan 朝鮮史料叢刊) and the Korean Historical Materials Album ( J. Chōsen shiryō shushin, K. Chosŏn saryo chipchin 朝鮮史料集眞). As the majority of facsimiles are Korean works reproduced by the Japanese Government General of Korea, the title includes both Japanese and Korean romanization.