5.1 Introduction

The creation of the Banking Union (BU) in 2012 represented an important change in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), and in the European Union (EU) in general. Indeed, it entailed the delegation of new competences in the areas of banking supervision and bank resolution to the EU level, and it demanded the creation of unique procedures and original governance mechanisms. It has no doubt represented a big step forward in the process of European integration as it is only the second area in which full integration is realised.Footnote 1 At the same time, it has also certainly increased the existing level of complexity within the EU. This is the case among other reasons because euro area Member States are part of the BU, but membership to the BU is also open to the rest of the Member States. In fact, in 2020, Bulgaria and Croatia availed themselves of this possibility to join the BU without having adopted the common currency. By creating a third category of Member States next to the EU27 and those that belong to the euro area within the EMU, the BU added a new layer of differentiation in an already largely differentiated Union.Footnote 2

As a result of this and of the (unaltered) EU legal framework on which basis it was created, the institutional architecture in which the BU is embedded, and the procedures that underpin it, are extremely complex. This is also the case because banking matters are of concern to all EU Member States since banks operate across the Internal market and are thus governed by its rules. Moreover, non-BU EU Member States are also naturally affected by the developments that happen within the BU, not least because BU banks commonly operate in non-BU Member States.Footnote 3 To make matters worse, whilst banking supervision and resolution are now the ultimate responsibility of an EU institution and agency (the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Single Resolution Board (SRB), respectively), national institutions continue to exercise part of the competences. A division of tasks is operated between various EU authorities, on the one hand, and the national ones, on the other.Footnote 4 Also, within the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), the ECB, for instance, supervises Significant Institutions (SIs) directly, whereas National Competent Authorities (NCAs) remain in charge of the supervision of smaller credit institutions (or Less Significant Institutions, LSIs).Footnote 5

The existing literature on democratic accountability in the BU has, so far, focused on the ECB in its quality as banking supervisor (ECB-SSM), and to a lesser extent on the SRB.Footnote 6 However, a comprehensive assessment of democratic accountability standards in this area of EU public policy requires that a more holistic, all-encompassing view is taken as only such an approach allows to determine whether the four goods that accountability should provide, which are openness, non-arbitrariness, effectiveness, and publicness, can be delivered.Footnote 7 This is precisely the perspective adopted in the present chapter, which aims at going beyond the mere analysis of the accountability mechanisms applicable to these two EU instances. Although both substantive and procedural accountability are considered, this chapter arguably already adds to the existing state of the art by providing a mapping of the accountability mechanisms in place considered altogether, that is from the inception – at the EU level – of the norms that are in force within the BU to their application by national and EU authorities.

To fulfil this objective, the present chapter is divided into four sub-sections: (1) It first examines how the BU operates and disentangles the various mechanisms in place, and the role of the different EU institutions and bodies within them. (2) It then proceeds to map the existing democratic accountability mechanisms. (3) The subsequent sub-section turns to the substantive part of the analysis, that is it considers how these mechanisms operate in practice. (4). The final section concludes by offering an assessment of the democratic accountability standards as they exist following the creation of the BU. It considers in particular whether any gap exists, whether in substance or in practice.

5.2 Who Does What and How? A Mapping of the Existing Procedures

The first substantive section of this chapter will detail the characteristics of the existing mechanisms and the specific role played by the various institutions and bodies involved therein.

For the purposes of this chapter, it suffices to note that European integration in the banking domain differs from what is the norm in other areas of the EMU, for instance, because different from what is the rule in the field of monetary policy, banking supervision is an area of shared competence in which the ECB does not adopt the necessary norms itself but, instead, applies those designed by the EU legislator and by the EU regulator. It is led to apply the standards primarily prepared – for the whole of the EU – by an EU agency, the European Banking Authority (EBA), but which must be formally adopted by the European Commission to become legally binding. This notwithstanding, the ECB may itself also adopt certain norms such that the divide between supervisor and regulator is not as clear-cut as it could seem at first sight.Footnote 8

As noted above, two EU authorities are primarily in charge of banking supervision and resolution within the BU. Their status, as well as the legal bases that underpin their existence, are however radically different. Whereas the ECB is an EU institution in its own right, the SRB is an EU agency. Powers in banking supervision could be conferred upon the ECB, thanks to the existence of a ‘reserve of competence’ contained in Article 127(6) Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU). It could nevertheless only be entrusted with new competences with regard to those BU Member States that also belong to the euro area, such that specific mechanisms had to be designed to allow the participation of non-euro area Member States in the BU.Footnote 9 By contrast, the SRB was created on the basis of Article 114 TFEU, an EU-wide Internal Market legal basis, even if only BU Member States participate in the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM).Footnote 10

Considering all this, studying the democratic accountability standards of the BU requires a substantive and a procedural analysis of several accountability mechanisms in place, that is those applicable to the ECB-SSM, to the SRB but also those applicable to the EBA, to the Commission and even to the ECB in as far as the ECB’s Governing Council ultimately is the organ that formally approves the supervisory decisions prepared by the ECB’s Supervisory Board.Footnote 11

To obtain a full picture of the existing situation, a multilevel perspective that considers the national dimension, as well as multilevel (administrative) cooperation and multilevel democratic accountability mechanisms, should also be adopted. Considering the limited space available here, however, this chapter will focus on the EU level and on the existing accountability mechanisms vis-à-vis EU institutions and bodies. The national and multilevel dimensions will only be underlined and considered in as far as it is necessary to assess the EU dimension of this issue.

5.3 Accountability Mechanisms in Place

5.3.1 Accountability Mechanisms Applicable to the ECB

The question of the ECB’s accountability plays a primary role in the guarantee of high (or adequate) democratic accountability standards in the BU because, as noted, the ECB is in charge of banking supervision. Its Supervisory Board – which is an internal organ of the ECB created for the specific purpose of banking supervision by the SSM Regulation –Footnote 12 is in charge of preparing supervisory decisions, which are later adopted by the Governing Council following a non-objection procedure. Its involvement is necessary because according to the Treaties, the Supervisory Board is not a decision-making organ of the ECB. As such, both the mechanisms in place to hold the ECB-SSM and the ECB to account are of importance when considering democratic accountability of and within the BU. However, because the role of the Governing Council is secondary to that of the Supervisory Board, the mechanisms in place vis-à-vis the latter will be examined first.

The accountability of the Supervisory Board is to be ensured following procedures defined in the SSM Regulation.Footnote 13 Its Article 20 is dedicated to ‘[a]ccountability and reporting’. According to this provision, the ECB is accountable to both the Council and the European Parliament (EP) for the implementation of this Regulation. To this end, it shall submit every year a ‘report on the execution of the tasks conferred on it by this Regulation, including information on the envisaged evolution of the structure and amount of the supervisory fees’ to the EP, the Council, the European Commission and the Eurogroup. That report shall be presented by the Chair of the Supervisory Board to the EP and to the Eurogroup in presence of those Member States that participate in the BU but do not belong to the euro area (they are also involved in the procedures mentioned subsequently where reference to the Eurogroup is made). This format of the Eurogroup is known as the ‘Eurogroup in BU format’. Both the Eurogroup and the EP also have the possibility (on an individual basis and independently from each other) to invite the Chair of the Supervisory Board to appear before them (or before the responsible committee in the case of the EP) to discuss the execution of its supervisory tasks. Oral or written questions may additionally be put to the ECB (i.e., the ECB-SSM) by both the Eurogroup and the EP.Footnote 14

Next to these procedures, the possibility exists that, upon initiative of the Supervisory Board’s Chair, confidential oral discussions behind closed doors be held with the Chair and the Vice-chairs of the responsible EP Committee, that is the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON Committee), where these ‘are required for the exercise of the European Parliament’s powers under the TFEU’. The details of these arrangements are to be defined in an interinstitutional agreement between the EP and the ECB, which was adopted in 2013.Footnote 15 Finally, a duty is set on the ECB to cooperate with the EP in its conduct of investigations. To this end,

[t]he ECB and the European Parliament shall conclude appropriate arrangements on the practical modalities of the exercise of democratic accountability and oversight over the exercise of the tasks conferred on the ECB by this Regulation. Those arrangements shall cover, inter alia, access to information, cooperation in investigations and information on the selection procedure of the Chair of the Supervisory Board.

The interinstitutional agreement details the content of the annual report, which the ECB has to submit to the EP. It also specifies that the Chair of the Supervisory Board shall be submitted at least to two ordinary hearings, although additional ad hoc exchanges of views may be organised too. Additionally, it specifies how confidential oral discussions have to take place in practical terms. Likewise, the modalities for the submission of written questions are specified, and the aim is that the ECB answers them within five weeks (as opposed to the six-week target set for the questions put to the ECB by MEPs on monetary policy issues as per the EP’s Rules of procedure). Specific provisions furthermore detail how information on the ECB’s tasks as a supervisor is to be made available. This includes, for example, access to the record of proceedings of the Supervisory Board by the ECON Committee or non-confidential information regarding a credit institution that has been wound up. The EP is to establish sufficient safeguards for the confidentiality of the ECB documents submitted to it to remain preserved.

As noted previously, also the EU executives (e.g. Commission, Council and Eurogroup) are addressees of the ECB-SSM’s annual report. What may, however, appear as more surprising is the fact that it is with the Eurogroup and not the Council with which the true relationship of accountability is established. Indeed, the annual report shall be presented to the Eurogroup, which may invite the Chair of the Supervisory Board to appear before it and submit both written and oral questions to the ECB-SSM. This state of fact is disturbing for several reasons. As recalled by the Court of Justice on several occasions,Footnote 16 the Eurogroup is not an institution of the Union but an informal group whose raison d’être is to allow for the coordination of euro area Member States’ policies. Neither the informal nature of the Eurogroup nor the purpose of its existence squares well with the role it is called to play in guaranteeing the ECB-SSM’s democratic accountability.

Moreover, according to Article 10 TEU, democratic accountability rests upon two pillars within the EU since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty: the EP and Member States government representatives participating in the Council. Considering all this, the ECB-SSM could rather have been held accountable by the Council. This would have made all the more sense as the Council (and formally at least, not the Eurogroup) is involved in the approval of (part of) the secondary legislation the ECB has to apply in its quality as banking supervisor. Additionally, the argument can be made that developments within the BU are of interest to all of the EU Member States, as is indeed confirmed by the fact that BU matters are, at least in some instances, discussed in Eurogroup meeting in inclusive format, that is with representatives from all EU27 Member States.Footnote 17 The Lisbon Treaty already opened the door to a ‘differentiated Council’, that is one within which on some occasions only euro area representatives may cast their vote, and thus the Council could have been used as an accountability forum. Admittedly, since the possibility formally exists that non-euro area (candidate) Member States may join the BU, an accountability forum that would only bring together BU representatives had to be set up, and only the Eurogroup (and not the Council) could easily be adapted for that purpose. But it remains the case that the solution found is largely unsatisfactory for the reasons outlined previously.

Next to these relationships of accountability with EU organs, ‘relationships with national parliaments’ are also foreseen in the SSM Regulation. Although formally, and according to the ECB itself, it is ‘primarily accountable to the EP’ and not to national parliaments, and although the question as to whether these relationships between the ECB-SSM and national parliaments serve the purpose of democratic accountability has been subject to debate,Footnote 18 there is little doubt that the powers with which parliaments have been entrusted vis-à-vis the ECB (written questions, reasoned observations on the annual report and exchange of views) resemble those that commonly exist between parliaments and any institution they hold accountable.

These relationships of accountability add to those that have existed between the EP (and the Council) and the ECB since the creation of the ECB. Indeed, the ECB’s (strong) independence is to be compensated by its relationship of accountability towards the EP (primarily). It must therefore address an annual report on ‘the activities of the ESCB [European System of Central Banks] and on the monetary policy of both the previous and the current year to the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission, and also to the European Council’.Footnote 19 This report shall be presented to the Council and to the EP, which ‘may hold a general debate on that basis’. Additionally, the possibility exists for the President of the ECB or the other members of the Executive Board to be heard before the ECON Committee on their own initiative, or on that of the ECON Committee. MEPs are also entitled to submit six questions for written answers to the EP.Footnote 20 In the framework of monetary policy, although some exchanges were indeed organised in the past,Footnote 21 formally no relationship exists between the ECB and national parliaments, as may appear logical considering that monetary policy is a competence of the Union.Footnote 22

The existence of a relationship of accountability between the ECB and the Council makes sense historically as, originally, the status of ‘Member State with a derogation’, that is that of Member State outside the euro area, was meant to remain temporary for all Member States bar Denmark and the United Kingdom which had obtained a permanent opt-out. Thus, correspondence largely existed between the geographical area within which the ECB’s monetary policy would take effect (at that point in time or eventually), and the Member States represented in the Council. However, already at the time when the Lisbon Treaty was drafted, it may be argued that this had become wishful thinking. This notwithstanding, Member States did not choose to change the identity of the forum in charge of holding the ECB accountable and instead the Council kept this prerogative, despite the fact that it is precisely that Treaty (i.e. the Lisbon Treaty) which formalised the existence of the Eurogroup. The choice in favour of the Eurogroup when the SSM was established could point to the willingness to further empower the Eurogroup, a forum which had already been significantly reinforced as a result of the euro area crisis. Furthermore, to state the obvious, a choice in favour of the Eurogroup is also to the benefit of the Member States, since the accountability and transparency standards it is submitted to are much less stringent than those applicable to the Council.Footnote 23

5.3.2 Guaranteeing the SRB’s Accountability

The SRM was established a few years after the SSM, and the latter’s accountability mechanisms no doubt inspired those of the former. Indeed, the obligations set on the SRB by the SRM Regulation are similar to those set on the ECB-SSM by the SSM Regulation.Footnote 24 However, considering that the SRM is an agency and not an EU institution like the ECB, it is accountable not only to the EP and the Member States – coming together in the Council and not in the Eurogroup but also to the Commission. The annual report is submitted to the EP, the national parliaments of participating Member States, the Council, the Commission and the European Court of Auditors. As a result of this, differently from what is the case within the SSM, the Eurogroup is not supposed to be involved in any way in this instance, which could be the case because the SRB is an EU-wide agency. The report is then presented to the EP and the Council. The EP may additionally invite the Chair of the SRB to a hearing, and a minimum of one hearing per year is set by the SRM Regulation. Written and oral questions may be submitted to the SRB by the Council and the EP, and the possibility to hold confidential oral discussions is also provided. Like it is the case between the ECB-SSM and the EP, an agreement that details the modalities of these discussions shall be concluded,Footnote 25 and the SRB is set to cooperate in any investigation the EP may initiate.

Like the interinstitutional agreement between the ECB-SSM and the EP, the Agreement between the EP and the SRB details the content of the report that the SRB has to submit every year. The topics addressed in the ordinary public discussions are also defined, as is the possibility to organise ad hoc meetings and the practical modalities of the confidential oral discussions. A minimum of two ordinary hearings per year is set. The EP shall be kept duly informed as a ‘comprehensive and meaningful record of the proceedings’ of every executive or plenary meeting is to be submitted to it within the six weeks that follow said meeting. The rest of the provisions contained in the Agreement are similar to those included in the interinstitutional agreement between the ECB-SSM and the EP.

Likewise, the SRM Regulation establishes a direct relationship between the SRB and the national parliaments of the participating Member States. Their nature (i.e., whether they constitute a relationship of accountability) is also not specified, but as they are very similar to those established with the EP they may also be viewed as contributing to the SRB’s accountability credentials. The powers vested with national parliaments in this framework are indeed very similar to those attributed to them vis-à-vis the ECB. However, the SRB is set under stronger obligations towards them than the ECB is.Footnote 26

5.3.3 The EBA’s Accountability Credentials

Guaranteeing democratic accountability within the BU demands that also the EBA be submitted to democratic control. This is the case because it prepares technical standards that are officially adopted by the European Commission at a later stage, and because it still fosters coordination among National Competent Authorities, including but not only in areas closely linked to banking supervision.

The accountability mechanisms applicable to the EBA were significantly enhanced when the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) Regulations were amended in 2019.Footnote 27 In its original version, the ESAs Regulation only established that ‘[t]he Authorities referred to in points (a) to (d) of Article 2(2) [among which is the EBA] shall be accountable to the European Parliament and to the Council’. By contrast, it is now foreseen that the EBA be accountable to the EP and the Council but that it shall also cooperate with the EP in the event that the latter decides to conduct an investigation. Despite the EBA’s quality as an agency – and differently from the SRB – the EBA is not accountable to the Commission. Several reasons could account for this. Perhaps the most evident one is that this provision concerns not only the EBA (or the ESAs) but also the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), which is not an agency but an independent body chaired by the President of the ECB. The EBA’s prerogatives are also more circumscribed than those of the SRB. The Commission is called to formally adopt the normative acts, which the EBA prepares such that it already is in a position to exercise some form of control over its actions, although the procedures differ for non-normative acts.

The EBA’s ‘Board of Supervisors shall adopt an annual report on the activities of the Authority, including on the performance of the Chairperson’s duties, and shall, by 15 June each year, transmit that report to the European Parliament, to the Council, to the Commission, to the Court of Auditors and to the European Economic and Social Committee’. As such, the duty that is now set on the Board of Supervisors is similar to that which the ECB-SSM and especially the SRB have to fulfil. However, in this case, a precise date is set by which the EBA has to fulfil its obligation. The European Economic and Social Committee is, too, an addressee of the report.

Additionally, it is prescribed that the EBA’s Chairperson be heard by the EP – upon its request – at least once a year ‘on the performance’ of the EBA. The format of the hearing is quite precisely defined in the Regulation, as it calls for the Chairperson to make a statement and to answer the questions put to it by MEPs. The EP may ask the Chairperson to report on the activities of the EBA at least fifteen days before the hearing. Specific mention is also made to the possibility for the EP to request that the EBA reports on its participation in international forums, which is all the more welcome as those (which include, for instance, the Basel Committee on Banking SupervisionFootnote 28) have assumed an ever larger role following the outbreak of the Great Financial Crisis.

Next to these procedures, the possibility also exists for the Council or the EP to put written questions to the EBA, which it shall answer within five weeks. As with the ECB-SSM and the SRB, confidential oral discussions may be organised since the EBA Regulation was amended.

5.3.4 The Commission

One last actor that arguably plays an important role in the BU is the European Commission. This is the case for numerous reasons, chief of which are the facts that it is involved in several of the procedures that exist (for instance, in banking resolution), that it has the last word on the standards developed by the EBA, and naturally also that it proposes the norms of secondary legislation that are of application within the BU.

In consequence, upholding suitable accountability standards within the BU demands that the Commission be submitted to sufficient controls. Put differently, in seeking to evaluate whether any accountability gap exists within the BU, one should also check whether the Commission’s actions in this domain are sufficiently scrutinised by the EP.

The EP has numerous means to hold the European Commission to account. Its strongest power lies in its possibility to remove its confidence in the Commission and thus force it to resign collectively.Footnote 29 The EP and its members may also put some oral and written questions to the Commission or submit Commissioners to major interpellations,Footnote 30 organise hearings to provide the Commission an opportunity to explain its decisions,Footnote 31 and create committees of inquiry.Footnote 32

5.3.5 Conclusion

The preceding analysis has evidenced that mechanisms exist to guarantee the democratic accountability of BU institutions. An evolution towards an enhancement of these mechanisms may additionally be witnessed, both in terms of their nature and in terms of their very existence. Indeed, the accountability of the EBA was significantly reinforced following the reform performed in 2019. Also, the mechanisms in place towards both the ECB-SSM and the SRB are more stringent than those applicable to the ECB. Several reasons may account for this. First, the ECB benefits from a stronger degree of independence in the area of monetary policy than it does in the field of banking supervision.Footnote 33 Second, accountability standards have evolved significantly over the past twenty years. For example, the EP is only consulted when the President of the ECB is appointed. In contrast, its consent is necessary for the chair of the Supervisory Board to be nominated,Footnote 34 that is the EP’s role has become larger over time.

Accountability mechanisms, be they formalised or not, make it more likely that democratic accountability is upheld. However, the mere existence of those mechanisms does not suffice, as there is, for example, no guarantee that they are used by the actors to which they are available. The next sub-section therefore turns to the practice of accountability in the BU to date.

5.4 The Practice of Democratic Accountability So Far

To evaluate the practice of democratic accountability so far, two dimensions in particular will be considered: formal accountability, that is if and how the existing instruments have been used, and substantive accountability, that is what these mechanisms have been used for in terms of substance. The data examined in this sub-section covers the period between November 2014 and April 2022, that is from the start of the functioning of the SSM until the date of submission. It consists of minutes of EP debates, written questions and the responses they received, as well as the yearly reports produced severally by the institutions examined.Footnote 35 The focus is set on the ECB-SSM, the SRB and the EBA owing to the ECB and the European Commission playing a secondary role in the BU if compared to the ECB-SSM, the SRB and the EBA.

Before proceeding with the proposed analysis, it should be noted that any conclusion drawn at this stage may only be provisional since the two pillars of the BU have only been functioning for a short period of time. This notwithstanding, the proposed study is still valuable because it allows to gain some knowledge of how the existing mechanisms have been used and which shortcomings inherent to them or gaps among them may exist. The conclusion thus provides an assessment of the current situation, as well as some suggestions for improvement.

5.4.1 Practice of Accountability to Date

It must be said from the start that research reveals that the existing democratic accountability procedures have been used indeed: Parliamentary hearings and ad hoc exchanges of views have been organised, reports have been produced and parliamentary questions have been put to the ECB-SSM and to the SRB. However, differences in terms of frequency and fluctuations over time have existed. The following paragraphs first consider the ECB-SSM before turning to the SRB and to the EBA.

As regards parliamentary questions put by MEPs to the ECB-SSM, it must first be said that they were not very numerous in the first years of the functioning of the SSM, as is only logical. They peaked in 2017 and 2018 although they remained infrequent at approximately forty questions per year (by comparison, the number of questions put to the ECB as the European institution in charge of monetary policy was similar in 2017 but it rose to more than three times this amount in 2018).Footnote 36 The number of questions has since been decreasing and there was only a dozen of them in 2021. Perhaps this could be explained by the varying levels of interest among participating MEPs, with notably one of the most active of them, Sven Giegold, having ceased to be an MEP. Also, the SSM no longer is a new instrument, thus MEPs’ interest could have faded with time, in particular seeing as no new banking crisis has emerged and the ECB thus seems to be fulfilling its tasks satisfactorily. It could be expected that MEPs’ interest would rise again if the ECB-SSM were to deal more closely with controversial issues such as climate change. Despite recommendations in favour of the creation of a space dedicated to questions posed by MEPs to the ECB-SSM (and the SRB),Footnote 37 no such step has been taken by the EP to date, which is regrettable as it makes relevant information harder to find.

Also, some questions have been put by national members of parliaments, most often from the German Bundestag. It is perhaps unsurprising that the members of the Bundestag are those who have used this mechanism most, considering the fact that the creation of the BU had raised concerns that democratic accountability standards would be lowered as a consequence thereof. Indeed, the German NCA, the BaFin, is functionally placed below the responsibility of the ministry of finance, which may be held accountable for the actions of the NCA.Footnote 38 More generally, and perhaps most importantly, a tradition exists for German MPs to ask written questions. In terms of their content, some of the questions are very specific and regard a specific credit institution, whilst others are much more general and address, for instance, non-performing loans, the implementation of the Basel standards or supervision in general. Such a mixed set of macro- and micro-topics seems to be healthy for the whole system of supervision.

Parliamentary hearings and ad hoc exchanges of views, as well as hearings before the Eurogroup, have taken place on a regular basis, and the annual reports were duly presented. Though some fluctuations over time may be observed in this regard as well – perhaps also due to the pandemic and the widespread ‘Zoom-fatigue’, it may generally be said that exchanges with MEPs have been more frequent than the minimum set by the SSM Regulation as they have often included a couple of ad hoc exchanges of views in addition to the standard bi-annual hearings.Footnote 39 The topics covered during these exchanges were varied as they ranged, for example, from the consequences of the pandemic to climate risks and the finalisation of Basel III.

Confidential oral discussions have taken place before hearings of the Chair of the Supervisory Board by the ECON Committee, and they have been ‘reported to be much more confrontational than public hearings, with “tough” language that is often absent in public interactions between the two institutions’.Footnote 40

Finally, the Chair of the Supervisory Board has regularly appeared before the Eurogroup, and these meetings have commonly been organised together with the Chair of the SRB (this is examined more in depth below). Fluctuations in their frequency have existed as well, with notably 2017 standing out as a year of particularly close exchanges, but this was also the year when the first resolution ever took place such that this is perhaps rather unsurprising. As these exchanges are not public, they are harder to assess. Nonetheless, the ECB had noted in the past that ‘[t]he topics of interest to the finance ministers overlapped to a large extent with those discussed in the European Parliament’Footnote 41 and the overall issues discussed may be found in the account of the main results of Eurogroup meetings since they exist. The topics covered have included, for example, broader issues such as non-performing loans and anti-money laundering.

If one considers the SRB, one may first regret that the part devoted to accountability in its annual reports remains particularly succinct. Also, it appears that its exchanges with the EP have been less frequent than those organised between the ECB-SSM and the EP as they have generally been limited to two exchanges per year in addition to the presentation of the annual reports. This could be explained by the fact that the SRM has only been activated on one occasion during the period considered here. On the other hand, the fact remains that the setting up of the SRM has raised questions indeed, in terms of its functioning and its financing but also in relation to questions related to the overall architecture of the BU and notably its missing pilar, the European Deposit Insurance Scheme, and the role the SRB could play therein. Therefore, more interest on the side of MEPs could have been reasonably expected.

MEPs have likewise devoted much less attention in their questions to the SRB than they have to the ECB-SSM. To date, they have addressed fifteen questions in total, of which seven were addressed by the same MEP (Sven Giegold).Footnote 42 These questions have sometimes consisted in requests for access to documents, or more general questions such as the architecture of the SRM in general, as well as questions on the Banco Popular case, for example.

Like was the case with the ECB-SSM as well, questions from national parliaments have not been numerous (ten in total) and only German MPs have asked questions to date. The identity of these MPs largely corresponds to those who raised questions to the ECB-SSM. Interestingly, although the answers to these questions are available on the SRB’s website, they are not translated into English but are, instead, only available in German. Whilst this is understandable as translation is demanding on resources, one may wonder whether this does not, in fact, diminish the SRB’s accountability potential vis-à-vis the larger public. Considering how few these questions are, it would be advisable for the SRB to make a courtesy translation available to all. As concerns the topics touched upon by these letters, they have regarded very factual issues, including the number of credit institutions whose resolution planning the SRB oversees, as well as questions related to specific credit institutions or related to findings of the European Court of Auditors.

The relationship between the SRB and the Eurogroup follows a similar pattern as the one between the ECB-SSM and the Eurogroup, not least because the Chair of the Supervisory Board and the Chair of the SRB commonly appear together before the Eurogroup. Issues addressed with the Chair of the SRB have included resolution planning, the built-up of the Single Resolution Fund or resolvability (continuity seems to exist in the topics discussed, which is only logical as the SRB’s main task in normal times is to prepare for potential resolution cases such that the issues that need addressing are rather recurrent as opposed to being individual events). It must be noted that although this practice of joint hearings with the Chair of the Supervisory Board and the Chair of the SRB makes perfect sense as they allow for a more comprehensive control by the EP of what is going on in the BU, it remains that it contradicts the content of the SRM Regulation, which foresees that the SRB – an EU-wide agency – be held to account by the Council. As noted above, it probably would have been best to entrust the Council with the task of controlling both the ECB-SSM and the SRB in the first place, also to guarantee higher transparency and thus higher accountability standards.

The relationship between the SRB and the Commission seems to unfold on a smooth basis, as the SRB noted, for instance, in its annual report for the year 2020 that it ‘continued to maintain its close cooperation with the relevant directorates-general of the Commission, in particular with the Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union (DG FISMA) and the Directorate-General for Competition (DG COMP) at all levels on various aspects, which are relevant to the SRB’s work and functions, and participated actively in the meetings of the Expert Group on Banking Payments and Insurance (EGBPI)’.Footnote 43 Further details are not available.

Finally, one may regret that the information regarding the EBA’s accountability is not much detailed; its annual reports and its website indeed only contain scarce information on this topic, and it is not easy to find. The EBA fulfils its duty to present its annual report to the EP, and it entertains relationships with other EU institutions.Footnote 44 Most of the correspondence publicly available is addressed to the European Commission, and it covers issues that go beyond banking supervision owing to the EBA’s broad mandate. This notwithstanding, some of the letters are indeed addressed to MEPs, but they remain scarce.Footnote 45

5.4.2 Conclusion

The preceding analysis of the use of the existing accountability mechanisms to date reveals first that information on this issue is scattered around the various websites and uneasy to find. This is regrettable, and efforts should be made to improve this situation, as already proposed by René Smits.Footnote 46

Second, it appears that, at the EU level, the existing procedures are being used indeed, as hearings and exchanges of views are organised, questions are posed, and reports are produced. The EP additionally produces annual reports on BU.Footnote 47 Parliamentary questions are, though rather infrequent, and fluctuations have existed over time in the frequency of the oral exchanges held. It is interesting to note that despite its duty to hold the EBA accountable too, the EP only keeps regular records of practice of accountability towards the ECB-SSM and the SRB but not towards the EBA (or any of the European Supervisory Agencies).Footnote 48 This is regrettable as the EBA and these agencies in general play an increasingly important role in financial supervision within the EU, and as the acts of soft law they adopt produce significant effects for banks and have been the object of litigation before the Court of Justice.Footnote 49

In any event, shortcomings exist in the practice of accountability: despite the fact that external experts are regularly invited to produce briefings, the questions put by MEPs are not always sufficiently to the point.Footnote 50 Most importantly, the same questions are not consistently picked up during debates.Footnote 51 Also, MEPs are not always clear about the appropriate forum or addressee for a specific issue. For instance, some of the questions put to the ECB were not addressed to it in the right setup, that is MEPs mixed up the setup designed for dialogue on monetary policy issues with the one reserved to banking supervision. Although this confusion could have been due to the very numerous forums in which MEPs have the opportunity to debate with the ECB, it could also be the case that they deliberately chose not to care for political reasons and simply use any channel they had at their disposal.

Beyond all this, it has been found that, in effect, MEPs only have had limited influence on the ECB-SSM’s policy, although this is because MEPs only rarely require such changes but rather use their interaction with the ECB to request information on policy views.Footnote 52 This could point to a usage of public hearings and questions primarily for communication purposes, as opposed to their being used for accountability purposes.Footnote 53 Confidentiality in banking supervision is a further hindrance in MEPs’ quest for accountability,Footnote 54 and reform proposals have been made to improve this situation.Footnote 55

Finally, and although this issue is only subsidiary to the analysis conducted here, one may observe that very limited use has been made by national parliaments of the possibility they now have to directly interact with the ECB-SSM and the SRB. To assess whether this results in an accountability gap, research should determine whether this is compensated by adequate mechanisms of accountability towards NCAs and the use thereof by parliaments at the national level.

5.5 Conclusion: Is There a Gap and If So, How to Bridge It

This chapter intended to adopt a holistic view of democratic accountability in the BU with a view to determining whether any gap exists. Some gaps appear to exist indeed, and they derive from (a) the EU’s constitutional framework, (b) the BU’s architecture and its characteristics, and (c) from practice, that is how the existing accountability mechanisms are used.

5.5.1 The EU’s Constitutional Framework Has Become Unfit for Purpose

The existing flaws are generally related to both the EU’s architecture and functioning, and specific to EMU. The shortcomings inherent to the EU’s architecture are twofold, and are caused by, on the one hand, the trend of agencification within the EU,Footnote 56 and relatedly to the absence of specific and precise legal basis for EU agencies, which would allow a much necessary update and adjustment of the Meroni doctrine. On the other hand, they derive from the gap that has grown between the existing legal framework, and the degree and the variety of differentiation within today’s EU (where differentiated integration is understood in the largest possible sense). As noted above, the co-existence of the BU, the euro area and the EU27 and the corresponding institutional variations of the meetings of national ministers at the EU level certainly blur the boundaries between the various groups of Member States, and thus the accountability channels applicable to the various procedures. This then must bring back to a reflection on the question of (internal and external) differentiation and membership within the EU more generally.

Some of the existing shortcomings are, though, specific to the EMU and its sub-area the BU. Whereas differentiation is a feature commonly observed within the EU and not specific to the EMU, the EMU is arguably the most extreme example of differentiation in terms of its breadth and reach with, among others, the ECB conducting the euro area’s monetary policy, or the existence of an intergovernmental European Stability Mechanism as an emergency safety net reserved to euro area Member States but one that also serves as a backstop to the (EU) BU. Differentiation within the EMU is then also visible in terms of its institutional embedding with the Eurogroup as a quasi institution, the existence of Euro Summit, of specific voting rules in the Council, and the recurrent proposals in favour of a euro area parliament or at least a euro area sub-committee to the ECON Committee,Footnote 57 to the point that the principle of institutional unity that used to be a requirement to any initiative of enhanced cooperation under Amsterdam could come under threat.Footnote 58 As has been evidenced in this chapter, the mechanisms formally in place within the BU are oftentimes pragmatic solutions to the lack of suitability of the existing legal framework as is illustrated by the Eurogroup’s role in guaranteeing the ECB-SSM’s accountability. Practice shows a further adaptation of the established mechanisms as in the case of the Eurogroup, which also serves as accountability forum for the SRB. Both of these phenomena nonetheless only illustrate that the existing institutional framework is unfit for purpose, because it has not been adapted to match the evolutions that have happened in the breadth of the policies conducted at the EU level and to the form that these take, even if it must be admitted that the framework currently in place has proven to be sufficiently flexible for informal arrangements to be developed.

5.5.2 Flaws Inherent to the BU

Next to these shortcomings related to the EU’s institutional framework, there are also shortcomings that are specific to the BU, although they partially derive from the problems that exist within the EU’s constitutional structure generally.

The BU is in-between the EU27 and the euro area, and relies on both structures. From this derives inherent complexity that in turn makes guaranteeing democratic accountability particularly challenging. Accordingly, democratic accountability standards within the BU may not be assessed by only looking at the ECB-SSM and the SRB. As this chapter has posited, other actors including the Commission and the EBA play an important role as well, and their accountability credentials must, too, be taken into consideration.

Mark Bovens has defined accountability as ‘a relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgment, and the actor may face consequences’.Footnote 59 When the last step is taken within the framework of the BU, that is when the forum that holds the agent to account is to take actions based on its assessment of how the principle has performed, it must hold not only the ECB-SSM or the SRB to account but also the Commission and the EBA because of their role as regulator. The ECB’s nature as an independent EU institution and as a central bank also acting as banking supervisor complicates matters further, as does the EBA’s and the SRB’s nature as independent agencies. As a result of the ECB’s numerous functions, accountability becomes more difficult to ensure because the same group of MEPs are called to regularly interact with the ECB in different capacities, thus demanding from them that they first identify in which forum they must ask which kinds of questions. In any event, however, as recently noted by the former Governor of England Paul Tucker, ‘[t]he European Parliament’s Econ committee is too big to conduct effective oversight of the ECB’s stewardship of the monetary regime’.Footnote 60 The same could be said of the ECON Committee when it is called to hold the ECB-SSM to account although in that context, the possibility for smaller meetings to be organised in the form of confidential oral discussions may partially contribute to solve this problem. Be this as it may, even if Paul Tucker is certainly right in considering the EP ECON Committee to be too large an accountability forum, it is difficult to imagine which other format would have sufficient legitimacy based on its representativeness of the (large) euro area to play such a role. Furthermore, other practical problems outlined below may in fact be a bigger hindrance to effective accountability than the ECON Committee’s large size.

Beyond all this, because the EU does not have exclusive competence in the field of banking supervision and bank resolution, national authorities continue to play a large role. Additionally, harmonisation is only partial such that the applicable rules vary across the BU. EU organs, and primarily the ECB, have to apply national norms upon whose content and legality they have no control.Footnote 61

Finally, democratic accountability within the BU does not solely rest on EU institutions and bodies; national institutions, too, play a large role. This is the case because they approve national legislation as noted previously, because they remain competent in areas that are closely linked to BU matters (for instance: anti-money laundering) and because they are closely involved in the functioning and the operation of both the SSM and the SRM.

5.5.3 How to Bridge the Existing Gaps?

If all were best in the best of possible worlds, differentiation within the EU would vanish, that is the three currently co-existing categories of Member States, which the EU27, the euro area and the BU form would disappear. Thus, some of the regulatory gaps and of the institutional complexity would cease to exist.

Likewise, if Treaty change were a realistic option, a better design for EU agencies could be introduced, a proper legal basis for the BU could be created, including the formal acknowledgement of a third category of Member States next to the euro area and the EU27, that is that of BU Member States. A true discussion on whether the ECB should be the BU’s supervisor could be had, and the Chinese wall that separates its monetary policy from its banking supervision functions better designed.

However, unfortunately, none of these options seem to be realistic at this stage of European integration. Even the Conference on the future of Europe is unlikely to lead to the full opening of Pandora’s box, as it might do so but only in specific areas with a specific objective.Footnote 62 It is true that following Brexit the most adamant advocate of the interests of non-euro area Member States is gone, and no non-euro area Member State has as large a financial market as the UK used to have. Consequently, none of them has the UK’s leverage in EU27-negotiations. But a discussion on Treaty change would likely regard many areas other than the BU, and taking account of all the challenges they are already facing internally, including the economic recovery post-COVID, the threats to the rule of law and to EU values, or the ecological and digital transition, EU Member States may not want to take this path at this point in time. Neither would they realistically be in a position to find a compromise solution at this stage if one considers how long they have been unable to come to a compromise solution on the completion of the BU, for instance.

If Treaty change is not an option, what is, then? In addition to the solutions already included in the main sections of this chapter, one could consider additional avenues to improve the existing situation.

First, institutional engineering, that is the improvement of existing practice through the actions of the institutions involved themselves should continue to be exploited. Institutional engineering commonly takes the form of arrangements put in place by institutions on an informal basis or their promoting regulatory change. In a nutshell, it means that institutions use their margin of discretion and action to the largest extent possible. One form this could take would consist in the creation of a dedicated BU sub-committee of the ECON Committee, a possibility that was already considered for the euro area in 2013–2014.Footnote 63 This would allow for some of the MEPs to become more specialised in BU matters, and they would not necessarily all have to stem from BU Member States.

Changes in secondary legislation (and in primary law where this is easily feasible) should also be considered with a view to upgrading the mechanisms in place, and to simplifying the existing architecture where possible.

Further harmonisation at the EU level should be pursued too, not only in terms of the norms applicable but also perhaps in terms of the minimum requirements set with respect to the features of the national institutions involved. At present, NCAs and NRAs are hosted by very different institutions that correspond to different national traditions and rules. Arguably, if for instance the applicable standards of independence were more strongly defined at the EU level, it would be easier to guarantee democratic accountability in this area, as the institutional setups would be less complex.Footnote 64 It may thus only be hoped that the Court of Justice will be called to continue to perform its duty of clarification and definition of the tasks and responsibilities of the different institutions involved within the BU.

Lastly, it may also only be hoped for that MEPs and MPs will improve the use they make of the existing mechanisms. This would include, as mentioned, asking more informed questions, making more demands for policy changes where necessary, and ensuring better synergies between the mechanisms that exist in parallel. To this end, interparliamentary cooperation should also be fostered, for instance, the Interparliamentary Conference on Stability, Coordination and Governance could be better exploited: to date, it has only rarely addressed BU-related matters. But other mechanisms should be established too, in the form of interparliamentary committee meetings hosted by the EP, and on the initiative of the Presidency parliament and with the involvement of national parliaments only.

As reforms to improve and complete the BU are high on the EU’s agenda again,Footnote 65 it is urgent that they be also accompanied by matching improvements of the democratic accountability mechanisms in place in the whole of the BU.

6.1 Introduction

In perhaps one of the most memorable quotes from the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) literature, Paul Craig once commented, ‘The Eurogroup can lay good claim to being the EU body that is least understood’.Footnote 1 This does not mean that it has not played a central role in decision-making in this area since its very inception.Footnote 2 On the contrary, it is, as recognized by the Euro-area leaders, ‘at the core of the daily management of the euro area’.Footnote 3 The Eurogroup partakes in deciding ‘who gets what, when, how’, which is rightly regarded as a key feature of EMU as a policy area.Footnote 4 Accordingly, this lays bare the necessity of controls over its activities in the EMU.Footnote 5

This chapter looks at the political and legal accountability of the Eurogroup. The discussion begins with the foundations and tasks of the Eurogroup (Section 6.2). The focus then shifts to the political accountability of the Eurogroup (Section 6.3), the emphasis being on its relationship with the European Council and the Economic Dialogues with the European Parliament (Section 6.3.1). The chapter further looks at its legal accountability, in light of the relevant case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) (Section 6.3.2). The penultimate section of the chapter provides an assessment of the Eurogroup’s accountability in light of the framework laid down in the introductory chapter to this volume, namely in terms of procedural and substantive ways of delivering the normative goods of accountability (Section 6.4). Section 6.5 concludes by outlining the key features of the accountability arrangements and practices pertaining to the Eurogroup.

6.2 Foundations and Tasks

The Eurogroup is recognized in Article 137 TFEU, according to which ‘Arrangements for meetings between ministers of those Member States whose currency is the euro are laid down by the Protocol on the Euro Group’. In turn, the preamble to Protocol (No 14) on the Euro Group mentions the High Contracting Parties’ desire ‘to promote conditions for stronger economic growth in the European Union and, to that end, to develop ever-closer coordination of economic policies within the euro area’. As such, it lays down ‘special provisions for enhanced dialogue between the Member States whose currency is the euro, pending the euro becoming the currency of all Member States of the Union’.

Article 1 of the Protocol sets out the composition of the Eurogroup and the purpose of its meetings. It provides that the finance ministers of the Euro-area Member States shall meet informally, when necessary, to discuss questions related to the specific responsibilities they share with regard to the single currency.Footnote 6 The Commission shall take part in the meetings, whereas the European Central Bank (ECB) shall be invited to take part in such meetings.Footnote 7 The meetings shall be prepared by the representatives of the finance ministers of the Euro-area Member States and of the Commission. Further, Article 2 of the Protocol provides that the finance ministers of the Euro-area Member States shall elect a President for two and a half years, by a majority of those States. The post is currently held by Paschal Donohoe, who is also the finance minister of Ireland.

The real-world picture is conveyed more accurately by the Eurogroup’s webpage: the agenda and discussions for each Eurogroup meeting are prepared by its President, with the assistance of the Eurogroup Working Group (EWG),Footnote 8 the latter being composed of representatives of the Euro-area Member States of the Economic and Financial Committee (EFC), the European Commission and the ECB.Footnote 9 The EWG members elect a President for a period of two years, which may be extended. The post is currently held by Tuomas Saarenheimo, who is also Chairman of the EFC. The office of the EWG President is at the General Secretariat of the Council of the EU in Brussels. ‘The secretariat tasks in relation to the Euro Group are divided between the General Secretariat of the Council (which is in charge, beyond the assistance to the President, of logistics) and the EFC Secretariat (which is responsible for the substance).’Footnote 10

According to its webpage, ‘The Eurogroup’s discussions … cover specific euro-related matters as well as broader issues that have an impact on the fiscal, monetary and structural policies of the euro area member states. It aims to identify common challenges and find common approaches to them.’Footnote 11 Craig comments that the Eurogroup is ‘central to all major initiatives relating to the euro area, broadly conceived’ and that its role is central to EU macroeconomic planning.Footnote 12 More specifically, ‘it brokers the agreements necessary for policy to become reality; it fosters implementation through close oversight; it plays a role in ensuring that EU legislation in the financial sector is properly implemented; and it is part of the accountability mechanism in the banking union.’Footnote 13 The activities of the Eurogroup may also have an impact on internal market issues more generally, which are not straightforwardly related to the single currency.Footnote 14

Apart from the primary EU law provisions that were set out above, there are various other provisions that confer tasks on the Eurogroup which are scattered throughout secondary EU law and even intergovernmental agreements. Space precludes a detailed exegesis of those legal provisions, such that we will only refer selectively to perhaps the most important of them. The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (also known as the Fiscal Compact, from its most impactful part) provides that the Eurogroup is charged with the preparation of and follow-up to the Euro Summit meetings.Footnote 15 It will be recalled that the Euro Summit brings together the Heads of State or Government of Euro-area Member States, as well as the President of the Commission and the President of the ECB, ‘to discuss questions relating to the specific responsibilities which the Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro share with regard to the single currency, other issues concerning the governance of the euro area and the rules that apply to it, and strategic orientations for the conduct of economic policies to increase convergence in the euro area’.Footnote 16 Moreover, according to ‘two-pack’ legislation, the Euro-area Member States shall submit annually a draft budgetary plan for the forthcoming year to the Commission and to the Eurogroup.Footnote 17 The Eurogroup shall discuss opinions of the Commission on the draft budgetary plans and the budgetary situation and prospects in the Euro-area as a whole on the basis of the overall assessment made by the Commission.Footnote 18 The Euro-area Member States shall further report ex ante on their public debt issuance plans to the Eurogroup and the Commission.Footnote 19

Furthermore, the Eurogroup forms part of the accountability mechanisms in the Banking Union.Footnote 20 More specifically, the Eurogroup receives a report from the ECB on the execution of its tasks in the Single Supervisory Mechanism, which shall also be presented to it by the Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB.Footnote 21 Moreover, the Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB may, at the request of the Eurogroup, be heard on the execution of its supervisory tasks, and the ECB shall reply orally or in writing to questions put to it by the Eurogroup.Footnote 22

6.3 Accountability Arrangements and Practice

6.3.1 Political Accountability

The political accountability of the Eurogroup is described as ‘thin’.Footnote 23 Craig comments that:

Its principal political accountability runs to the European Council, as attested to by its role in preparing Euro Area Summits and having the responsibility for ensuring that the recommendations from such meetings are followed up. The reality is, however, … that the Eurogroup has considerable power in shaping macroeconomic policy broadly conceived for euro‐area states. The recommendations that emanate from the European Council will often be at a relatively abstract level, and it will be the Eurogroup that imbues them with greater policy specificity.Footnote 24

The latter case is exemplified by the Eurogroup’s actions during and in response to the COVID-19 crisis.Footnote 25 Overall, ‘[t]here is little by way of formal accountability for the Eurogroup’s input into the Euro Summits, and equally little by way of accountability check as to how it implements Euro Summit policy, more especially when the conclusions from such Summits require interpretation and choice in the implementation.’Footnote 26 This does not, however, preclude the possibility that the Eurogroup may be ‘held to account in the European Council for the more detailed policy initiatives that the Eurogroup embraces when fulfilling European Council policy recommendations’.Footnote 27

This answers the question of whom account is to be (primarily) rendered to, but does not speak of the standards against which its performance is to be assessed. After all, the Protocol on the Eurogroup merely provides that its main task is to ensure close coordination of economic policies among the Euro-area Member States, in order to promote conditions for stronger economic growth.Footnote 28 It is rightly argued that a meaningful accountability relationship

is more difficult to achieve where the criteria against which the Eurogroup is being judged are relatively abstract recommendations from the European Council; where it is intended that these should be fleshed out by the Eurogroup; where all institutional players are mindful of the difficult political and economic determinations that have to be made; and where evaluation of success or failure may be difficult, and may not be apparent for some considerable time.Footnote 29

The Eurogroup’s role during the Euro-crisis, notably with regard to financial assistance programmes, provides a good illustration of this.Footnote 30 ‘The [Eurogroup] was the body coordinating and, de facto, deciding whether financial assistance would be granted, and under which conditions, to a requesting Euro Area Member State. It is again gaining specific relevance in the context of the Recovery and Resilience Facility.’Footnote 31 The Eurogroup assesses the national implementation of the Euro-area recommendation through national recovery and resilience plans.Footnote 32 It is also evolved in coordinating the implementation of these plans.Footnote 33

The ‘six-pack’ and ‘two-pack’ of EU legislation further make provision for Economic Dialogues.Footnote 34 Economic Dialogues are held in order to enhance the dialogue between the EU institutions on the application of economic governance rules and with Member States, if appropriate, and to ensure greater transparency and accountability. The competent committee of the European Parliament, that is, the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON), may invite representatives of Member States, the European Commission, the President of the Council, the President of the European Council and the President of the Eurogroup, to discuss economic and policy issues.Footnote 35 According to the relevant EU rules, the competent committee of the European Parliament may invite the President of the Eurogroup for an Economic Dialogue during certain stages of the implementation of the European Semester for economic policy coordination and in the context of macroeconomic adjustment programmes, including the post-programme surveillance phase.Footnote 36 It should be stressed that, under the existing rules, the European Parliament has no powers to ‘sanction’ the Eurogroup for its performance or to amend any of the decisions taken. The relevant provisions instead focus on the information and debate stages of accountability.Footnote 37 There is further the expectation that finance ministers participating in the Eurogroup will be held separately to account by their respective national parliaments, in accordance with national constitutional requirements.

The Eurogroup President takes part in an Economic Dialogue twice a year (in spring and in autumn) and, if needed, on an ad hoc basis. This practice was agreed during the 7th legislative term through an exchange of letters between the competent Committee and the Eurogroup President.Footnote 38 Nine dialogues were held with the President of the Eurogroup in the ECON Committee during the 8th legislative term (autumn 2014 to spring 2019). Furthermore, the President of the Eurogroup occasionally participated in an exchange of views in plenary as well as in interparliamentary meetings relating to economic governance.Footnote 39 The Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) of the European Parliament provided members of the ECON a briefing in advance of these dialogues, as well as papers written by external experts.Footnote 40 This is important from the perspective of substantive accountability, because it helps address any information asymmetries between the European Parliament and the Eurogroup.Footnote 41 Five economic dialogues with the President of the Eurogroup have taken place thus far during the current (9th) legislative term.Footnote 42 In contrast to previous practice where only web streaming was available, a transcript of the dialogues is now made available to the public.Footnote 43

In line with agreed practices, the following procedure is applied for the exchanges of views with the Eurogroup President. First, there are introductory remarks by the Eurogroup President for about ten minutes. These are followed by five-minute question-and-answer slots, with the possibility of a follow-up question, time permitting, within the same slot. Two minutes maximum are allocated for the question, and then three minutes maximum for the answer. In the first round of questions, each political group has one slot. Thereafter, the d’Hondt system is applied, which determines the order of questions by political groups. Any time for additional slots is allocated on a catch-the-eye basis.

Overall, the MEPs ask well-informed questions. In terms of the topics discussed, these are very much the issues of the day (whether it is, for example, financial assistance programmes back in the day or, nowadays, the assessment of recovery and resilience plans or the future of the EU fiscal rules). The MEPs also address structural issues pertaining to the EMU architecture, such as the completion of the Banking Union. Obviously, these two sets of issues sometimes intersect (as was the case, for example, with questions regarding the postponement of the work plan for the Banking Union). Further, there are questions about the Capital Markets Union, the digital euro, the enlargement of the Euro-area, as well as plenty of other issues. Whenever questions are not (adequately) answered by the Eurogroup President, it is common for the MEPs to return to the point made by their colleagues previously.Footnote 44 It is clear that the questions asked focus not only on the procedure by means of which a particular decision or policy choice was made but also on the substantive worth of the policy decision itself.Footnote 45

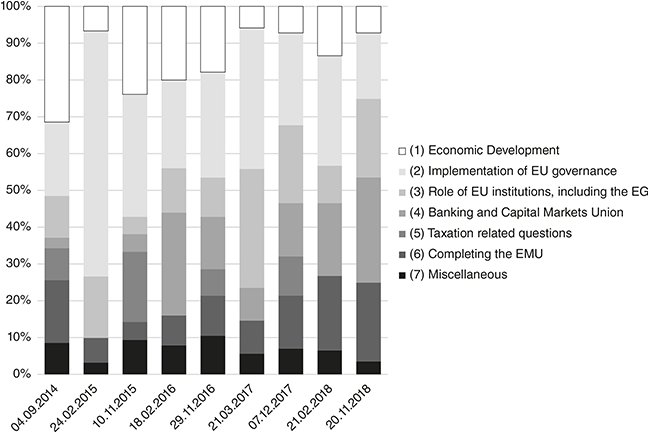

The Economic Governance Support Unit has conducted an extensive analysis of the Economic Dialogues with the President of the Eurogroup during the 8th legislative term (autumn 2014 to spring 2019). Nine dialogues were held in ECON during the said period. ‘As a general conclusion, one can say that issues raised during the dialogues reflected on-going policy work by the Eurogroup and other topical issues related to the well-functioning of the euro area, including the public attention given to a specific policy issue at the time of the dialogue.’Footnote 46 The following figure provides an overview of the topics discussed during the 8th legislative term.

The Economic Dialogues with the Eurogroup President are rife with comments on accountability.Footnote 47 It is clear that the European Parliament, and the ECON Committee in specific, wants more on part of the Eurogroup in terms of accountability and transparency. Moreover, it is clear that the MEPs take issue with the frequency of those meetings with the Eurogroup President.Footnote 48 The Chair of the ECON Committee, Irene Tinagli, has opened the first two Dialogues with Eurogroup President Paschal Donohoe with an, to all intents and purposes, identical remark:

President Donohoe, we were very pleased to read in your motivation letter as candidate for the Eurogroup President that, and I quote you: ‘effectively communicating to our citizens and to the European Parliament the steps we are taking in the euro area will be a priority of my term’. So I would like to take this opportunity to reiterate ECON’s request for enhanced cooperation with yourself and with the Eurogroup, and invite you to put forward how you would like to follow up on these. Due to the key role of the Eurogroup in steering the policy work of the euro area as a whole, we would like to stress the importance of a well-established cooperation practice with the European Parliament, notably our Committee. One way would be to go in the direction of the practice that we have for the monetary dialogue with the ECB President, which has been working very nicely in enhancing our cooperation. In these very challenging times, the Eurogroup is indeed at a key position. Therefore I think that the need for transparency and accountability is particularly important for us.Footnote 49

The Eurogroup President replied, on the second occasion that this comment was made, thus: ‘I’ll certainly reflect on what the Chair just said there regarding how we can structure our dialogue in the future.’ Overall, strengthening the (political) accountability of the Eurogroup remains work in progress. This places added emphasis on its legal accountability, which, as seen in the following section, is – at best – scant and indirect.Footnote 50

6.3.2 Legal Accountability

The legal accountability of the Eurogroup has been the subject of lengthy litigation before the EU courts and remained ill-defined for a number of years. The leading authorities are Mallis and Chrysostomides. In very simple terms, it was held in Mallis that litigants cannot admissibly bring actions for annulment under Article 263 TFEU against the acts of the Eurogroup.Footnote 51 The Court noted that the term ‘informally’ is used in Protocol (No 14) on the Euro Group and that the Eurogroup is not a configuration of the Council pursuant to the latter’s Rules of Procedure. Accordingly, it could not be equated with a configuration of the Council or be classified as a body, office or agency of the EU within the meaning of Article 263 TFEU.Footnote 52

In Chrysostomides, the Court held that the Eurogroup is not an ‘institution’ within the meaning of the second paragraph of Article 340 TFEU, such that its actions cannot trigger the non-contractual liability of the Union.Footnote 53 What renders this judgment uniquely important for the accountability of the Eurogroup is the reasoning provided by the Court for its judgment denying that the Eurogroup is an EU entity established by the Treaties. The Court held that ‘the Euro Group was created as an intergovernmental body – outside the institutional framework of the European Union’ and that ‘Article 137 TFEU and Protocol No 14 … did not alter its intergovernmental nature in the slightest’.Footnote 54 The Court further held that ‘the Euro Group is characterized by its informality, which … can be explained by the purpose pursued by its creation of endowing economic and monetary union with an instrument of intergovernmental coordination but without affecting the role of the Council – which is the fulcrum of the European Union’s decision-making process in economic matters – or the independence of the ECB’.Footnote 55 It also held that

the Euro Group does not have any competence of its own in the EU legal order, as Article 1 of Protocol No 14 merely states that its meetings are to take place, when necessary, to discuss questions related to the specific responsibilities that the ministers of the [Member States whose currency is the euro] share with regard to the single currency – responsibilities which they owe solely on account of their competence at national level.Footnote 56

As argued extensively elsewhere, the Court’s reasoning in Chrysostomides is unconvincing.Footnote 57 First, it is not adequately explained in the judgment why Article 137 TFEU and Protocol No 14 did not alter the Eurogroup’s intergovernmental nature in the slightest. Insofar as the Court refers selectively to arguments provided by the Advocate General, notably his literal and teleological interpretation, this interpretation of the provisions of the Protocol is not straightforward in textual terms, and that whatever the origins of the Eurogroup and its functions prior to the Treaty of Lisbon may have been, they do not seem to warrant the conclusion that, following the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, the Eurogroup remains an entity situated outside the EU legal and institutional framework. Second, it is not clear from the judgment why the informal nature of the Eurogroup means that it is not an EU entity established by the Treaties for the purposes of non-contractual liability. In reality, formally recognizing the Eurogroup by means of primary law provisions would not affect the role of the Council, insofar as those Treaty provisions which confer powers on the Council remained unchanged. It is perfectly possible to recognize the existence of an entity within the EU institutional framework which would not encroach on the powers of the Council. It is also unclear why the informal nature of the Eurogroup is necessary to preserve the ECB’s independence. Third, contrary to what the Court stated, we have seen that various EU law provisions confer powers on the Eurogroup. This also prompts the question of whether secondary EU law may confer powers or tasks on informal, non-EU bodies, especially to the point of involving them in the accountability mechanisms for a formal EU institution, the ECB.

According to the Court in Chrysostomides, individuals may bring before the EU courts an action to establish non-contractual liability of the EU against the Council, the Commission and the ECB in respect of the acts or conduct that those EU institutions adopt following the political agreements concluded within the Eurogroup.Footnote 58 Moreover, the principle established in Ledra Advertising applies,Footnote 59 meaning that an action for damages is admissible insofar as it is directed against the Commission and the ECB on account of their alleged unlawful conduct at the time of the negotiation and signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).Footnote 60 Furthermore, the Court extended the Ledra principle to the participation of the Commission in the activities of the Eurogroup. It held that

the Commission … retains, in the context of its participation in the activities of the Euro Group, its role of guardian of the Treaties. It follows that any failure on its part to check that the political agreements concluded within the Euro Group are in conformity with EU law is liable to result in non-contractual liability of the European Union being invoked under the second paragraph of Article 340 TFEU.Footnote 61

The Court is effectively arguing that there is a complete system of remedies and procedures, such that litigants in this area are ensured effective judicial protection. Unfortunately, this is most certainly not the case when the agreements reached in the Eurogroup are implemented by non-EU bodies, such as is the case when the MoU with the ESM gives concrete expression to a macroeconomic adjustment programme. The ESM Treaty, as it currently stands, gives jurisdiction to the CJEU only when an ESM Member contests the internal resolution of disputes (with another ESM Member or the ESM itself) on the interpretation and application of the ESM Treaty or the compatibility of ESM decisions with the ESM Treaty.Footnote 62 Private litigants have no standing to challenge the decisions of the ESM organs. What is more, as explained extensively elsewhere, there may be no measures adopted by formal EU institutions incorporating the specific harmful measures that litigants wish to challenge.Footnote 63 The relevant Council Decision, whether adopted on the basis of Articles 136(1) and 126(6) TFEU as was the case in Chrysostomides or – nowadays – on the basis of ‘two-pack’ legislation,Footnote 64 may not include all the terms from the Eurogroup statement and/or the MoU with the ESM. Chrysostomides is a case in point here, as only some of the harmful measures were mentioned in the impugned Council Decision. EU courts may or may not be able to read any terms that are not (fully) replicated into the relevant Council Decision.Footnote 65