1. IntroductionFootnote 1

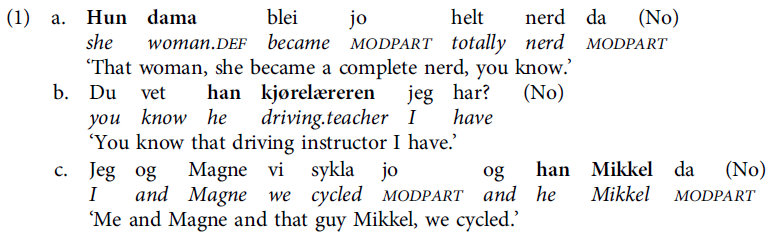

In the Scandinavian languages, third person singular pronouns (Bokmål Norwegian han/hun, Nynorsk Norwegian han/ho, Swedish han/hon ‘he/she’) can be used as demonstratives; we refer to these demonstratives as pronominal demonstratives (PDs) (see e.g. Delsing Reference Delsing1993; Julien Reference Julien2005; Johannessen Reference Johannessen, Solstad, Grønn and Haug2006, Reference Johannessen2008a, b, Reference Johannessen and Enger2012, Reference Johannessen, Næss, Margetts and Treis2020; Lie Reference Lie2008; Strahan Reference Strahan2008). Norwegian (No) examples are given in (1) (from Johannessen Reference Johannessen2008a; originally from the NoTa-Oslo corpus,Footnote 2 translations adapted).

In Norwegian, PDs typically express psychological distance. They are used in the spoken language to refer to a person that the speaker does not know personally, or has negative feelings toward, or somebody who is known to the speaker but not to the listener (Johannessen Reference Johannessen2008a). PDs are combined with a definite noun referring to a specific human individual, as in (1a) and (1b), or a proper name, as in (1c). Like other demonstratives, and unlike pronouns, they do not inflect for case (see Johannessen Reference Johannessen2008a for discussion): in Swedish and Norwegian, the subject form is invariantly used (e.g. hun dama ‘she.nom woman.def’ in (1a), see further below), whereas Danish uses the object form (the Danish equivalent of (1a) would be hende damen ‘she.acc woman.def’; see further Johannessen Reference Johannessen2008a on PDs in Danish). Note that PDs are different from preproprial articles, which are used exclusively with proper names (and a few kinship nouns) in many Norwegian dialects. Unlike preproprial articles, PDs are never obligatory, they do not inflect for case, and they have a demonstrative meaning (see Johannessen Reference Johannessen2008a).Footnote 3

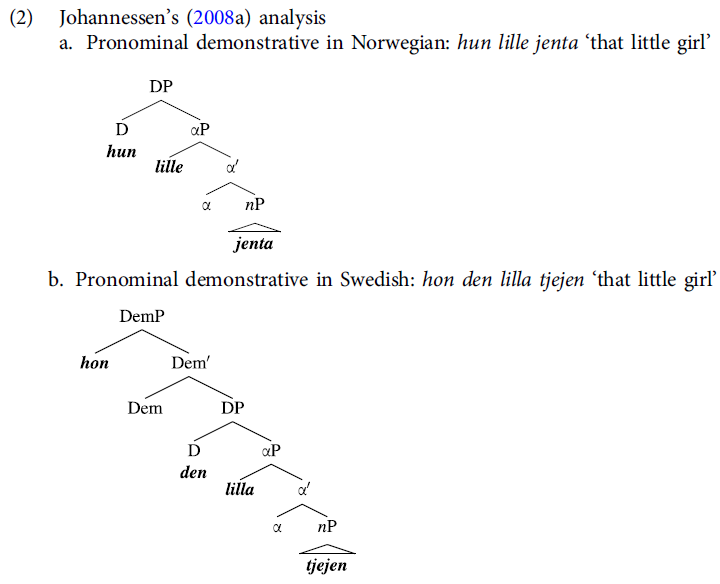

The most influential syntactic analysis of Scandinavian PDs thus far was proposed by Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a); she refers to PDs as psychologically distal demonstratives (PDDs). Based on the observation that PDs can co-occur with a prenominal definite determiner in Swedish (and Danish), but not in Norwegian, Johannessen suggests that the PD is DP-internal in Norwegian, but in a demonstrative phrase (DemP) above DP in Swedish; only in the latter case can it co-occur with a determiner in D. A simplified representation of Johannessen’s analysis is given in (2).

In this paper, we offer a new, comparative view on PDs in Scandinavian, based on data sets that were not available at the time of Johannessen’s seminal works. In the first part of the paper, we present new observations on the history of PDs in Scandinavian, differences between PDs in Norwegian and Swedish, and a revision of Johannessen’s account. We show that Swedish has a more restricted use of PDs than Norwegian, but in fact allows the PD to co-occur not only with a determiner, but also with another demonstrative. Based on these observations, we propose that Swedish han/hon in the relevant contexts are not true demonstratives (although, for simplicity, we keep referring to them as PDs). On our account, Swedish PDs are syntactically reduced pronouns, located in a high position (above demonstratives), doubling certain features that are found further down in the extended nominal projection (see Josefsson Reference Josefsson and van Riemsdijk1999, Reference Josefsson2006; van Craenenbroeck & van Koppen Reference van Craenenbroeck and van Koppen2008). We further assume that they have logophoric features (Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson2011, Reference Sigurðsson2014) that activate shared knowledge between the speaker and addressee.

In the second part of the paper, we extend our perspective to heritage varieties of Scandinavian,Footnote 4 in this case, Norwegian/Swedish spoken by the descendants of emigrants who left Scandinavia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and settled in the US and Canada (see Johannessen & Salmons Reference Johannessen and Salmons2015a for an overview). We focus mainly on American Norwegian (AmNo), which is currently the only Scandinavian heritage variety for which we have enough data to systematically investigate PDs.

The use of PDs in AmNo is uncharted territory. While previous literature on the syntax of nominals in AmNo suggests a relatively high degree of stability (Anderssen, Lundquist & Westergaard Reference Anderssen, Lundquist and Westergaard2018, van Baal Reference van Baal2020 on possessive constructions and double definiteness; Kinn Reference Kinn2020a on predicate nouns),Footnote 5 PDs are of particular interest because they are, at least on the face of it, a phenomenon at the syntax-pragmatic interface (their distribution is in part governed by pragmatic factors such as psychological distance). Previous studies have argued that interface phenomena are vulnerable in bilinguals, including heritage speakers; this view is often referred to as the Interface Hypothesis (IH; see Sorace Reference Sorace2011 for an overview). At face value, the IH would predict that PDs are a vulnerable phenomenon in AmNo. We, however, contend that there is considerable stability in this area, even with respect to the subtle features that are particular to PDs in Norwegian, as opposed to PDs in Swedish. We argue that all (apparent) interface phenomena are not the same, and that retention of PDs in AmNo is to be expected in the context of our analysis, which entails that speech act participants (speaker and hearer) are encoded in narrow syntax. We also make the case that the deictic properties of PDs may have contributed to stability (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018:63–65).

The availability of new corpus data has been a precondition the study of PDs in AmNo. The Corpus of American Nordic Speech (CANS; Johannessen Reference Johannessen2015) allows us to study how heritage speakers of AmNo use PDs in spontaneous speech. We have used version 3.1 of this corpus (released in January 2021), which, in addition to data from present-day heritage speakers, includes freshly transcribed data from the 1930s and 1940s, recorded by Einar Haugen, Ernst W. Selmer and Didrik A. Seip, and data from the 1980s and 1990s, recorded by Arnstein Hjelde. This recent addition allows us to trace the use of PDs over several generations in America in a way that has not been possible before.

New corpus data have been crucial not only to study if and how AmNo speakers use PDs, but also in order to establish a baseline to which the heritage variety can be compared. Ideally, the baseline should approximate the language of the first emigrants (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018:10–13); this is the best way to know whether seemingly special properties (or apparent loss of properties) in a heritage language are actually a result of changes that happened away from the homeland. Establishing this sort of baseline has been a challenge for previous studies of heritage Scandinavian (see e.g. Johannessen & Larsson Reference Johannessen and Larsson2015, Lohndal & Westergaard Reference Lohndal and Westergaard2016, and discussion in van Baal Reference van Baal2020:Chapter 3), and it has been fairly common to use present-day homeland varieties as the basis for comparison. In this study, however, we use novel data from the speech corpus LIA (established in the project Language Infrastructure made Accessible; homeland Norwegian (EurNo) dialect speakers born in the 19th/early 20th century), and also written corpus data from 19th century homeland Swedish (EurSwe). By going as far back in time as the late 19th/early 20th century, we can reveal the status of PDs at the time of mass emigration from Scandinavia to the United States. This takes us very close to the ideal baseline (and in fact, we also have data from a few individuals who left Norway and immigrated to the US themselves).

The paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we discuss PDs in homeland Scandinavian. Here, we present new observations that challenge Johannessen’s (Reference Johannessen2008a) analysis of PDs, and show that there are further differences between Norwegian and Swedish, which we take into account in a revised analysis. This section also shows that PDs were clearly present in homeland Scandinavian at the time of mass emigration. In Section 3, we discuss PDs in heritage Scandinavian, focusing on American Norwegian. We show that PDs are attested throughout the history of this heritage variety, and that they are used in a way that resembles the use in the homeland, down to the subtle details that distinguish Norwegian PDs from Swedish ones. Section 4 discusses the retention of PDs in AmNo in further detail, in the context of the IH; we also argue that the findings from AmNo can inform the discussion about the syntactic representation of speech act participants. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Revisiting pronominal demonstratives in homeland Scandinavian

In this section, we revisit PDs in homeland Scandinavian.Footnote 6 Based on new observations, particularly concerning the interaction between PDs and (other) demonstratives, we propose a revised syntactic analysis of PDs (Section 2.1). We also offer new comparative and diachronic perspectives on the use of PDs in homeland Norwegian and Swedish, based on data from the Norwegian LIA-corpus and the Swedish corpus infrastructure Korp (Section 2.2).

2.1 The syntax of PDs: A challenge and a new proposal

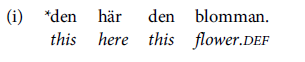

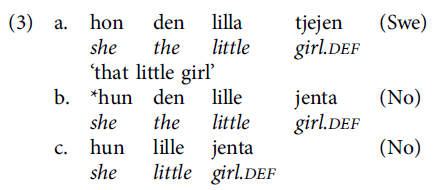

A clear difference between Norwegian and Swedish, which motivated the different syntactic structures proposed by Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a), concerns the interplay between PDs and prenominal definite determiners (see Section 1 above; the prenominal definite determiner is used when a noun is modified by an adjective). In Swedish (Swe), as opposed to Norwegian, a PD and a prenominal definite determiner can be combined, as illustrated in (3) (see also Johannessen Reference Johannessen2008a:176, 178):

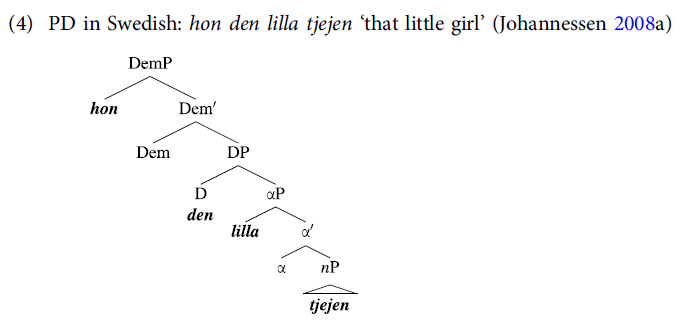

The pattern in (3a) is fully acceptable (and, we add, generally preferred) in Swedish, whereas Norwegian speakers do not accept it (see (3b)); Norwegian speakers must use the alternative in (3c).Footnote 7 The pattern in (3a) suggests that Swedish PDs are generated in a high position, and Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a) refers to them as ‘DP-external’. In her analysis, the prenominal definite determiner sits in D, and the PD in DemP above DP; the Swedish structure can thus accommodate both elements at the same time, as shown in (4) (= (2b), repeated for convenience).Footnote 8

Swedish PDs contrast with Norwegian PDs, which are analyzed as D elements; see (5) (= (2a)). Norwegian PDs are in complementary distribution with prenominal determiners (also generated in D); the two elements cannot co-occur.

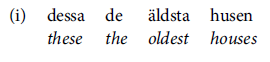

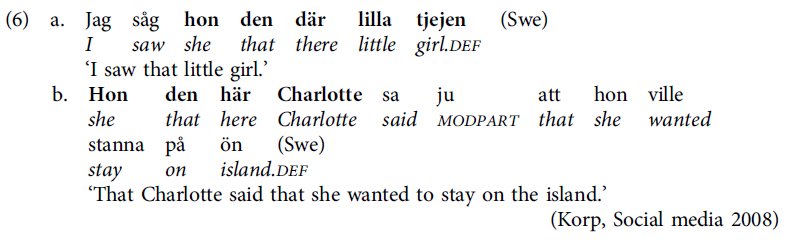

Now, a challenge for Johannessen’s analysis of Swedish consists in the fact that not only definite determiners, but also regular demonstratives, can co-occur with the PD. This is shown in (6) ((6a) is modelled on (3a) above; (6b) is from Korp; see further in Section 2.2 on this corpus infrastructure):

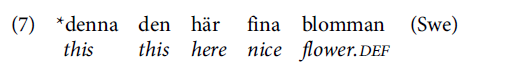

In (6), the reinforcing, deictic elements där/här ‘there/here’ make it clear that den där and den här encode more than just definiteness; they are (complex) demonstratives. Footnote 9 While there is general agreement that the prenominal definite determiner den sits in D, the most obvious assumption for den där/den där is that they are located in DemP, similar to other demonstratives. This poses the question of the status and position of the PD hon. On the face of it, it looks like a demonstrative; one reason for this is that there is no case inflection. In Swedish, pronouns, but not demonstratives, inflect for case; in (6a), the PD hon is in object position, but it does not have the object form (which would be henne). However, against a demonstrative analysis it can be objected that it is not generally possible for two demonstratives to co-occur in Swedish, as illustrated in (7):Footnote 10

Because of the general pattern illustrated in (7), it does not seem well motivated to assume an additional demonstrative position above DemP (recall that in (6a–b), DemP would be occupied by den där/den här). One could possibly imagine that hon in (6a–b) was not formally part of the same extended nominal projection as den där tjejen/den här Charlotte, but instead a very loosely connected apposition or independent, doubling pronoun (see Vangsnes Reference Vangsnes2008). However, as mentioned, hon does not have case inflection, as one would expect if it was a pronoun and syntactically independent of the following phrase. Footnote 11

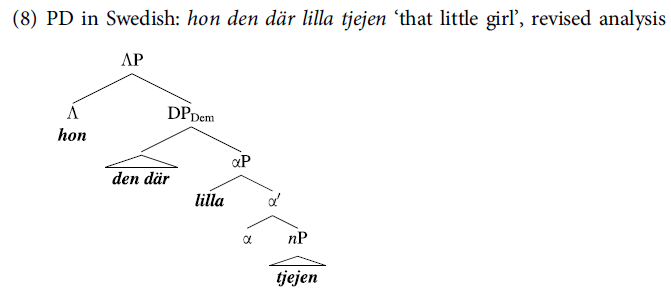

To meet the challenge of examples like those in (6), we propose an alternative account whereby Swedish PDs are neither demonstratives nor independent, phrase-external pronouns. Instead, we suggest, inspired by Josefsson (Reference Josefsson and van Riemsdijk1999, Reference Josefsson2006) and van Craenenbroeck & van Koppen (Reference van Craenenbroeck and van Koppen2008), that Swedish PDs represent a type of doubling that happens within the nominal projection. The PD doubles features that are located further down in the nominal: semantic gender (Josefsson Reference Josefsson and van Riemsdijk1999:737–741) and presumably also specificity; these features are found in nP and below (see Julien Reference Julien2005). Footnote 12 Doubling (‘double spell-out’) of features within the nominal (a ‘big DP’) has previously been proposed for a number of other languages and dialects (see van Craenenbroeck & van Koppen Reference van Craenenbroeck and van Koppen2008 and references therein for an overview).

On our account, the Swedish PD is best characterized as a pronoun rather than a demonstrative. However, we propose that it is underspecified compared to regular personal pronouns; it does not have a full set of formal features (see also Josefsson Reference Josefsson and van Riemsdijk1999, Holmberg & Nikanne Reference Holmberg and Nikanne2008) and therefore it does not inflect for case. At the same time, we propose that PDs have features that represent the speech act participants (speaker/addressee). This is in the spirit of Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2006:1358), who points out that han/hon as PDs are ‘speaker oriented’. We assume with Sigurðsson (Reference Sigurðsson2011, Reference Sigurðsson2014) that this type of feature (logophoric feature, labelled Λ in our tree diagrams) is represented at the edge of phases in the syntactic derivation. Footnote 13 We further propose that logophoric features, in the case of PDs, activate knowledge that is shared between the speaker and addressee. Han and hon in the relevant constructions thus bear some resemblance to recent uses of the determiner sånn in Norwegian and Swedish (see Johannessen Reference Johannessen and Enger2012 and Ekberg, Opsahl & Wiese Reference Ekberg, Opsahl, Wiese, Nortier and Ailin Svendsen2015). Footnote 14 A sketch of the revised analysis of Swedish PDs is given in (8):

As is evident from the structure in (8), we assume a functional projection above the demonstrative den där; the Swedish PD is located in this projection.Footnote 15 We propose that the head of this projection is a logophoric feature (Λ); for simplicity, other features, such as the doubled gender/specificity features have been left out. The crucial point is that the position is not a demonstrative position; the Swedish PD, on our analysis, is not formally a demonstrative. We assume that the distal, demonstrative meaning that is conveyed in examples like those in (6) is contributed by den där/den här and not by hon.Footnote 16

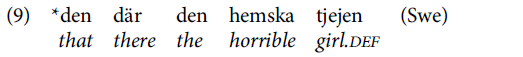

As is also evident from (8), our revised analysis differs from that of Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a) in one other respect: Instead of positing a DemP above DP, we are representing Dem and D in one functional projection, which we have labelled DPDem. The motivation for this is primarily empirical: in general, demonstratives and the prenominal definite determiner are in complementary distribution and cannot be combined. Footnote 17 This is shown in (9):

The pattern in (9) does not hold for PDs, which, as we have shown, can be combined with a definite determiner. The fact that PDs and unambiguous demonstratives such as den där behave differently in this respect is in accordance with our proposal that Swedish PDs are not proper demonstratives. With regard to the label DPDem and the distribution of features in the nominal spine, we do not go into further detail about the theoretical implications in this paper. D and Dem being represented in one head could be conceptualized as an instance of ‘clustered’ features in the sense of Giorgi & Pianesi (Reference Giorgi and Pianesi1997); alternatively, one could analyze it as ‘spanning’ (Starke Reference Starke2009).

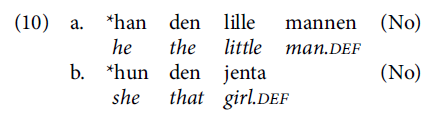

Having proposed a new analysis of PDs in Swedish, we now turn to PDs in Norwegian. Norwegian differs from Swedish in that PDs do not co-occur with the prenominal definite determiner (see 10a); they also do not co-occur with (other) demonstratives (10b):

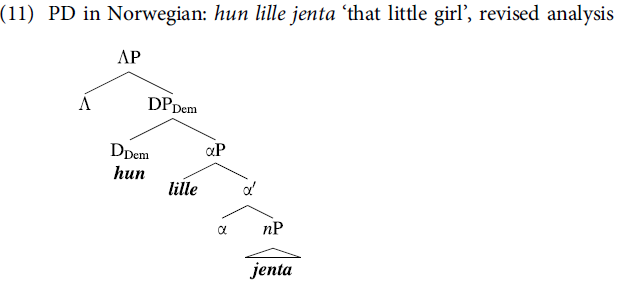

Thus, for Norwegian, unlike Swedish, there are weighty reasons to assume that PDs are proper demonstratives, i.e. that they lexicalize features conveying demonstrative and distal meaning. By and large, we maintain Johannessen’s (Reference Johannessen2008a) analysis; however, we state explicitly that D, in the case of PDs, contains a demonstrative element. We express this by using the label DDem, implying that Dem and D are represented in one head and not two, just like in our analysis of Swedish. The revised analysis of PDs in Norwegian is sketched in (11). Like other demonstratives, and unlike the Swedish PD, the Norwegian PD expresses deixis, but along a psychological dimension. As in the Swedish structure, DPDem is embedded under a functional projection that encodes logophoricity, providing the deictic center.Footnote 18, Footnote 19

To sum up, we have presented two syntactic structures, one for Swedish PDs and one for Norwegian PDs. The Norwegian structure, in which han/hun sits in DDem, clearly implies that the pronoun han/hun has taken on a function as a proper demonstrative; PDs are different from other demonstratives in that they can only be used in reference to persons and in that they convey a psychologically distal meaning, but in terms of structure, they are very similar. For Swedish, it follows from our analysis that the term ‘pronominal demonstrative’ is not entirely justified, as the pronouns han/hon are not in a demonstrative position; recall (8) above.

Having discussed the syntactic structure of PDs in homeland Scandinavian, we now turn to their distribution and use, comparatively and diachronically, based on new corpus data. As we will show, the conditions on use of PDs lend additional support to the syntactic difference between Swedish and Norwegian proposed above.

2.2 PDs in use: Comparative and diachronic perspectives

As mentioned in Section 1, we have explored the use of PDs in Norwegian and Swedish in a set of corpora that were not available when Johannessen (Reference Johannessen, Solstad, Grønn and Haug2006, Reference Johannessen2008a, b) conducted the first in-depth studies of PDs. When selecting corpus data, we gave special priority to speakers born in the (late) 19th and early 20th century, and texts from the same time period. The reason for this is twofold. Firstly, it enables us to shed new light on the history of PDs. Johannessen (Reference Johannessen, Solstad, Grønn and Haug2006:104) laments that it is difficult to establish exactly how old PDs are because of the lack of speech corpora that go further back in time than the 1970s; this has, however, changed dramatically after the appearance of the LIA corpusFootnote 20 in particular. Secondly, by going as far back in time as the late 19th/early 20th century, we can reveal the status of PDs at the time of mass emigration from Scandinavia to the United States (see Haugen Reference Haugen1953 on AmNo and Hasselmo Reference Hasselmo1974 on AmSwe). This means that we are able to establish a baseline closely approximating the language of the first emigrants (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018:10–13), to which we can compare the use (or non-use) of PDs in heritage Scandinavian (we return to this in Section 3).

We limit our attention to certain aspects of the distribution of PDs, particularly in the early sources, and differences between Norwegian and Swedish (for a more detailed account, we refer to Kinn & Larsson Reference Kinn and Larsson2020). In Section 2.2.1, we describe the corpus searches and give an overview of the results. Section 2.2.2 discusses differences between Norwegian and Swedish (further to the differences that were demonstrated in Section 2.1).

2.2.1 Queries in LIA and Korp and diachronic results

The LIA corpus contains old dialect recordings from all of Norway. We queried a subset of the corpus, based on criteria relating to age and geography: To reach as far back in time as possible, we included all speakers born before 1880; this amounts to 29 individuals who, altogether, produce approximately 105,000 word tokens. In terms of geography, we limited our search to the (former) counties Oppland, Hedmark, Telemark and Buskerud. These counties are located in the interior of South-East Norway, a part of the country from which many people emigrated, and whose regional linguistic features have been influential in shaping the AmNo language spoken in the American Midwest today (Johannessen & Laake Reference Johannessen and Laake2012; Hjelde Reference Hjelde2012, Reference Hjelde2015). We included all speakers from these counties, a total of 165 individuals, who, altogether, produce approximately 384,000 word tokens. Our total subcorpus, including both the speakers born before 1880 and the speakers from inner South-East Norway, amounts to 478,000 word tokens, produced by 192 speakers. Footnote 21

To find pronominal demonstratives, we queried for the pronominal forms han ‘he’ and ho ‘she’ followed by a definite noun.Footnote 22 The query does not include proper names, as these are not tagged as definite. Although PDs are often used with proper names (see e.g. example (1c) in Section 1), there are some advantages to excluding them from the query: in this way, we avoid any ambiguous examples in which han/ho could potentially be interpreted as either a PD or a preproprial article (see Section 1). We included examples containing der ‘there’ as a reinforcing element in addition to han/ho (Leu Reference Leu2015:18; Vindenes Reference Vindenes2017, Reference Vindenes2018). All hits were manually checked in their surrounding context to exclude mistagged or irrelevant examples.

In the LIA subcorpus, we found 58 examples that we analyze as PDs; 39 were produced by speakers from inner South-East Norway, and 19 produced by speakers born before 1880. The number of individual speakers producing PDs was 38; 30 of them are speakers from inner South-East Norway and eight are speakers born before 1880. In other words, only a small portion (38 out of 192) of the speakers in our subcorpus produce PDs. Moreover, the examples are not evenly spread across the speakers that use them. In the subcorpus of speakers born before 1880, two individuals from Målselv in Northern Norway are responsible for 10 out of the 19 PDs.Footnote 23

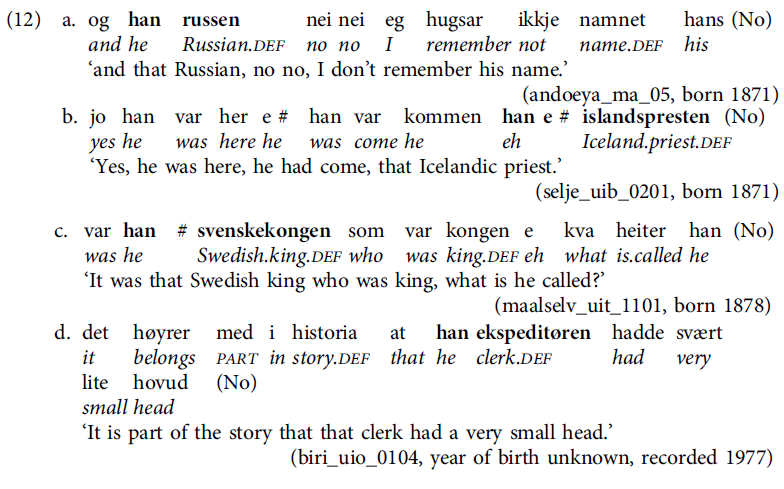

Some examples of PDs are given in (12) (the symbol # in these and other examples marks a pause):

In all the examples in (12), it is clear from the context that the PD is used to refer to someone that the speaker does not know personally. In (12a) and (12c), this is highlighted by the fact that the speaker is struggling to remember the name of this person. The use of PDs in these older data resembles the use in present-day Norwegian, as described by e.g. Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a), and this can be taken to suggest that PDs were established in the language around the time when the ancestors of today’s heritage speakers emigrated.

For Swedish, speech corpora like LIA are not available.Footnote 24 Therefore, we have drawn written language data from the corpus infrastructure Korp (Borin, Forsberg & Roxendal Reference Borin, Forsberg and Roxendal2012). We have used the corpora Svensk prosafiktion 1800–1900 (Spf: ‘Swedish prose fiction’), comprising of 16.27 million word tokens from the 19th and 20th centuries, and Äldre svenska romaner (‘Older Swedish novels’), comprising of 56 novels from the period 1830–1940, amounting to 4.35 million word tokens. These corpora contain passages that approximate the spoken language, e.g. dialogue, and they do not include poetry. As present-day Swedish is less studied than present-day Norwegian with respect to PDs, we included a present-day corpus in addition to those from the 19th and 20th century. The present-day corpus contains social media texts (more than 10 billion word tokens); these texts often have features in common with informal speech. For the earlier Swedish period, we manually checked the relevant hits in their surrounding context.

To extract PDs, we searched for han/hon ‘he/she’ in the sentence-initial position, directly followed by a noun.Footnote 25 We also searched for han/hon directly followed by a proper name (irrespective of position in the sentence). As mentioned in Section 2.1, examples with proper names were excluded from the investigation of Norwegian, in part to avoid potential ambiguity between PDs and preproprial articles, which are common in many present-day Norwegian dialects. In written Swedish, on the other hand, preproprial articles would be unexpected; thus, there is no strong motivation to categorically exclude proper names from this part of the study.Footnote 26

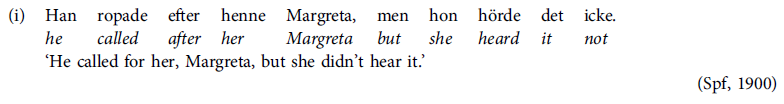

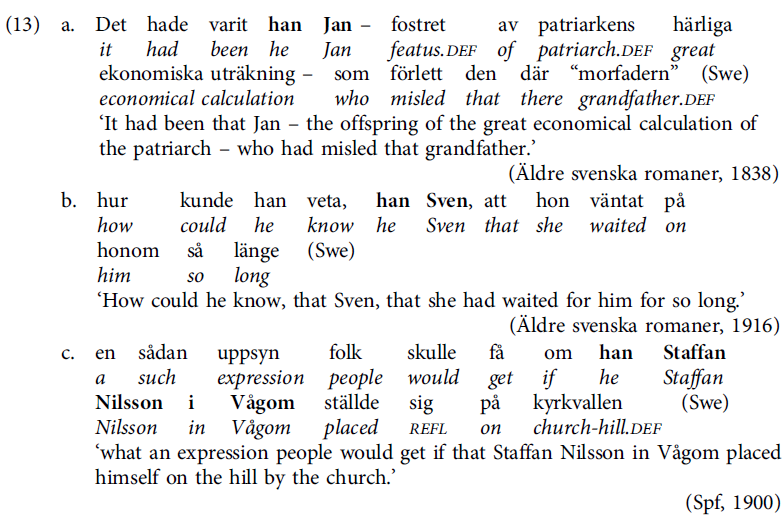

We found examples of PDs in all of the Swedish text collections. For the purposes of this paper, we focus on the earlier Swedish period. In this period, PDs are clearly attested, although they are very uncommon (less than 20 relevant hits in a corpus of approximately 20 million words); keep in mind, however, that the corpus consists of written texts and that PDs are only expected to occur in contexts where the authors approximate the spoken language.Footnote 27 Our earliest attestation is from 1838 (a novel by Almquist); apart from that, most occurrences are from the beginning of the 20th century. Some examples are given in (13):

The examples in (13a) and (13c) have a psychologically distal meaning, and (13a) clearly conveys a negative attitude; this is what we expect from what we know about PDs in present-day Scandinavian. We return to example (13b) below, in Section 2.2.2.

To sum up the diachronic results based on new corpora, we found that Swedish, like Norwegian, has had PDs as an established part of the grammar for at least a century. Although we do not have the same type of data available for both languages in all time periods, we can say that, in general, the way that PDs are used in the earlier sources for each language resembles the way they are used in more recent sources (see further Kinn & Larsson Reference Kinn and Larsson2020). There are, however, differences between the two languages.

2.2.2 Differences between Norwegian and Swedish

In Section 2.1, we demonstrated that there are differences in the way that PDs interact with (other) demonstratives and definite determiners in EurNo and EurSwe. In this section, we show some further differences between the two languages; we argue that these differences, too, are consistent with to the underlying syntactic structures that we have proposed.

Firstly, considering cognitive status (Gundel, Hedberg & Zacharski Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1988, Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993), demonstratives are typically used about referents that are part of the background knowledge (i.e. familiar), but which are not activated or in focus in the context. In EurNo, PDs can be used with referents that are previously mentioned in the discourse, as in the example in (14) (see also Johannessen Reference Johannessen, Næss, Margetts and Treis2020 for more examples and elaboration).

In (14), the PD functions as a reminder that the referent is part of the background knowledge. The errand boy is mentioned earlier in the discourse, but he is not in focus (and he is not personally known by the speaker and listener). When the speaker returns to the boy (to say something negative about him), a PD is used.

In EurSwe, it is difficult to verify this type of use: PDs are rarely used with referents that have been mentioned previously in the discourse (see also Teleman, Hellberg & Andersson Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999/Vol.2:274 for a similar observation). Examples can be found (such as (13b) above), but they are few and far between in our corpora (and as we will see below, they do not necessarily have a distal meaning, as they would in Norwegian). While it might be possible that this difference between EurNo and EurSwe is partly due to the different type of data (spoken – written) available for the two languages, that is hardly the full explanation. In the Swedish part of the Nordic dialect corpus (where a single EurSwe example of a PD can be attested, see note 24), we find contexts similar to that in (14) above; see (15). Notably, EurSwe has an ordinary demonstrative (den där ‘that’) here.

Thus, in contexts such as (14) and (15), the use of PDs appears to be more restricted in EurSwe than in EurNo. We contend that this follows from the underlying structure proposed in Section 2.1: as Swedish PDs are doubling, syntactically reduced pronouns, and not true demonstratives, Swedish resorts to a regular demonstrative (den där) in (15). In Norwegian, on the other hand, the PD can straightforwardly be used, as it lexicalizes demonstrative features with deictic power.

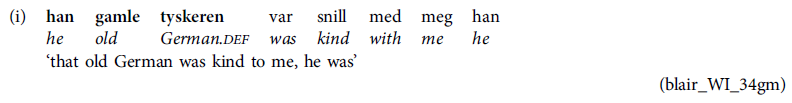

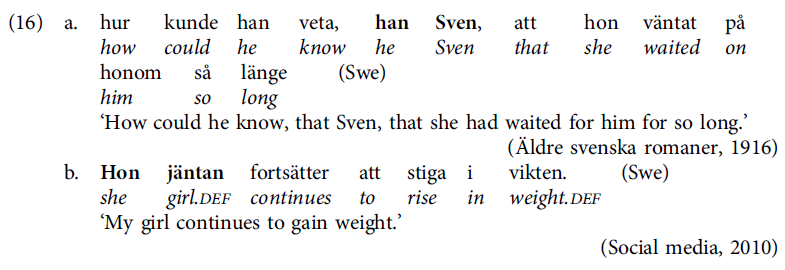

While the use of Swedish PDs seems more restricted in contexts like (14) and (15), there is a different sense in which Swedish PDs have a wider distribution. In Norwegian, PDs are used with psychologically distanced referents that might be part of the background. In Swedish, they can also be used with referents that are already in focus (in the sense of Gundel et al. Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993, i.e. they have the highest possible level of accessibility), and in those cases, they are compatible with a proximal meaning, implying solidarity. Consider the examples in (16):

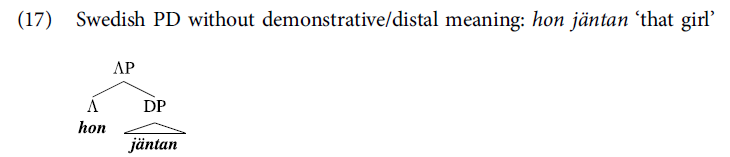

The early 20th century Swedish example in (16a) (= (13b) above) is used by a woman to refer to a loved one, who has just left her after an intimate conversation between the two. The example in (16b), from present-day Swedish, is used by a mother; it refers to her baby girl. Examples like (16b) appear to be typical in social media texts written by parents discussing their very young children; they seem to imply proximity/solidarity, and the child is clearly in focus. We do not find examples like these in our EurNo data.Footnote 28 With their lack of demonstrative/distal meaning, the existence of PDs such as those in (16) corroborate our conclusion that Swedish PDs are not proper demonstratives. We propose that cases such as (16) are structurally similar to the regular Swedish PDs in the sense that han/hon is a doubling, reduced pronoun. The difference between examples like (6a) above (hon den där lilla tjejen) (with the structure in (8)), and cases such as (16), is that in (16), there is no other demonstrative element present. An illustration of the structure of (16) is given in (17):

In (17), there is a simple DP instead of DPDem. This is in the spirit of Julien’s (Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005) framework, in which DemP is only present when it contains lexical material with a demonstrative meaning. On our analysis, the structure in (17) is syntactically underspecified for psychological distance. This means that it can be used even with referents that are psychologically close to the speaker.Footnote 29

To sum up Section 2, PDs seem to behave more like demonstratives in EurNo than in EurSwe, both with respect to (in-)compatibility with other demonstrative forms (Section 2.1), and discourse distribution/semantics (Section 2.2). There is some (possibly inter-individual) variation that blurs the picture somewhat (certain Swedish speakers seem to have access to a ‘Norwegian-like’ structure and vice versa; see Kinn & Larsson Reference Kinn and Larsson2020 for discussion), but the overall picture is rather clear: PDs in EurNo and EurSwe have partly different syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, even beyond what was demonstrated by Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a). We have also shown that PDs have been established in both languages for at least a century; they are attested in the speech of individuals born in the late 19th/early 20th century and in texts from the same period. With this in mind, we now turn to heritage Scandinavian, with AmNo as our primary focus.

3. Pronominal demonstratives in American Norwegian

The fact that PDs are attested in homeland Scandinavian speakers born as early as the late 19th and early 20th century, i.e. the time of mass emigration from Scandinavia to the United States (see Haugen Reference Haugen1953 on AmNo and Hasselmo Reference Hasselmo1974 on AmSwe), makes it relevant to ask whether PDs are still found in the heritage varieties AmNo and AmSwe. PDs constitute a particularly interesting phenomenon in the context of heritage languages: as their distribution depends on both syntactic and pragmatic factors, they can, at least apparently, be characterized as a phenomenon at the syntax-pragmatic interface. Interface phenomena have been shown to be vulnerable in heritage languages (see e.g. Sorace Reference Sorace2011 and further discussion in Section 4). Thus, one might expect to see changes in the use of PDs, although previous studies suggest a relatively high degree of stability in the structure of heritage Scandinavian nominals (see Anderssen et al. Reference Anderssen, Lundquist and Westergaard2018, Kinn Reference Kinn2020a, van Baal Reference van Baal2020).

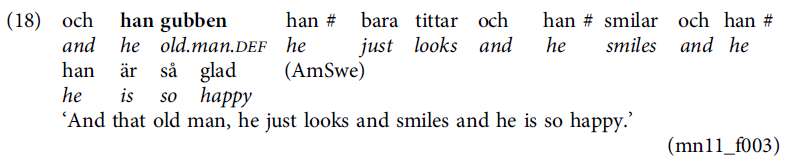

For AmSwe, the amount of available speech data that can shed light on the status of PDs is, unfortunately, quite small; CANS includes 22 Swedish speakers, producing 45,000 word tokens. As expected in a sample of this size, there are not many PDs to be found. We note that PDs are attested in AmSwe with one example, uttered by a third-generation heritage speaker, shown in (18):Footnote 30

We refrain from drawing any firm conclusions about PDs in AmSw because of the small sample size; further investigations are left for the future. For AmNo, on the other hand, CANS offers a more substantial amount of data both from present-day speakers and from previous generations of immigrants and heritage speakers. In the remainder of this section, we explore PDs in AmNo. We present our corpus (CANS) and queries in Section 3.1; the results are presented in Section 3.2. Our main finding is that PDs seem to be licensed in a way very similar to the baseline of (older) Norwegian dialect recordings from the LIA corpus.

3.1 Queries in CANS

The Norwegian part of CANS (version 3.1) contains transcribed and tagged recordings of 246 speakers of Norwegian heritage, producing approximately 729,000 word tokens. When querying the corpus, we used the same search criteria that we used for the Norwegian part of LIA (see Section 2.1 above for details); in other words, we searched for the relevant pronominal forms (han/hun) followed by a definite noun, excluding proper names. Footnote 31 Most of the CANS data was recorded from 2010 onward by Janne Bondi Johannessen and colleagues (152 speakers producing 615,000 word tokens); in addition, there are also a number of recordings made in the 1980s and 1990s (by Arnstein Hjelde; six speakers producing 36,000 word tokens)Footnote 32 and in the 1930s/1940s (by Einar Haugen, Didrik Arup Seip and Ernst Selmer; 88 speakers producing 78,000 word tokens). This enables us to trace the use of PDs in AmNo over time, across generations of heritage speakers.

3.2 Results

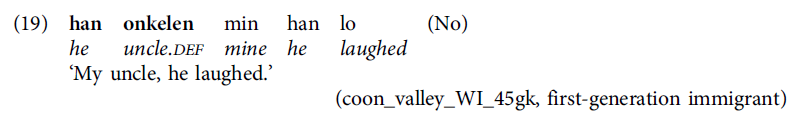

Our queries in the Norwegian part of CANS yielded 22 hits that we analyze as PDs. PDs are attested both in the earliest recordings from the 1940s and in the more recent data (10 examples from the 1940s, one example from the 1990s and 11 examples from 2010 onward). Two of the examples from the 1940s were uttered by speakers who were born in Norway and thus do not count as heritage speakers; one of these examples is given in (19) (the speaker introduces her uncle, who is not mentioned in the previous discourse).

We exclude speakers who were born in Norway from our further discussion of AmNo; note, however, that the examples of PDs produced by these speakers align with the findings from the LIA corpus (Section 2) and provide unambiguous support to the notion that PDs were a part of the language that the first emigrants brought from the homeland. The remaining 20 examples were uttered by heritage speakers (altogether 19 individuals); most are second- or third-generation immigrants.

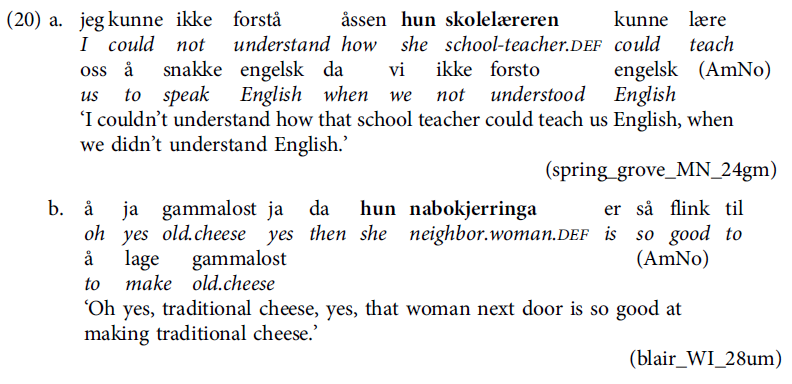

We note that the number of occurrences of PDs in AmNo is lower than what we found in EurNo (20 hits in a 712,000 word corpus for AmNo (first-generation immigrants excluded) in comparison to 60 hits in a 478,000 word corpus for EurNo). We also note that the number of PDs is higher in the sample from the 1930s/1940s than in the later periods (the absolute number of PDs is fairly similar in the 1940s and the 2010s, but the sample from the 2010s is bigger, see Section 3.1).Footnote 33 However, we remain cautious with regard to which conclusions can be drawn about the grammar of AmNo based on this. PDs are a low-frequency phenomenon in Norwegian generally, which means that quantitative results based on spontaneous speech are highly sensitive to factors such as individual variation and discourse situation. As mentioned above, two individuals are responsible for 10 out of the 19 PDs in the LIA subcorpus of speakers born before 1880. Collection methods can also influence the PD data, as PDs are more likely to occur in long narratives and anecdotes, which appear to be common in the LIA recordings and Haugen’s data. The sociolinguistic context also matters; while previous generations of AmNo speakers often lived in Norwegian-speaking societies of a substantial size (Hjelde Reference Hjelde2015), where everyone presumably did not know each other personally, today’s speakers do not necessarily have this frame of reference when discussing matters relating to their Norwegian heritage (as they typically do in the CANS interviews). In other words, there are several possible explanations for the differences in frequencies of PDs that do not involve grammatical change. For the moment, we focus on the fact that PDs are attested in AmNo throughout the investigated period at rates that are too high to be dismissed as random errors or idiosyncrasies. In the remainder of the section, we illustrate how PDs are used, starting with some examples recorded in the 1940s, in (20):

In (20a), the speaker seems to be distancing himself psychologically from the mentioned teacher (the speaker is talking about a challenging phase in his childhood, starting school without any prior knowledge of English). In (20b), a woman next door is introduced; she is never mentioned by name and is not familiar to the listener. In both (20a) and (20b), the use of PDs is very similar to what we find in the homeland baseline.

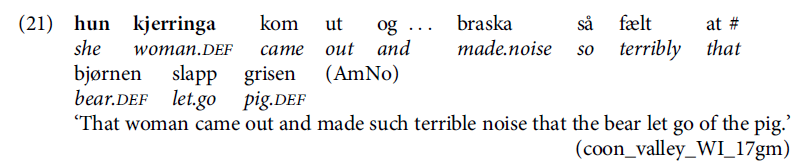

Example (21) was recorded in the 1990s:

The woman in the story in (21) is not mentioned by name and is clearly not known personally by either the speaker or the listener. Again, this is the same type of use that we find in the homeland baseline.

Some present-day AmNo examples of PDs are given in (22); all of these examples were recorded in 2010 or later:

In (22a)–(22c), the PD is used with a definite noun to refer to somebody that neither the speaker nor the listener knows personally. In the context leading up to (22a), a couple of boys are introduced for the first time (and without names). In (22b), the man is introduced for the first time, and clearly with psychological distance; the man hired the speaker (as a boy) to do a hard job that the speaker was really too young to do. In (22c), the PD signals psychological distance to the wife of an acquaintance (later in the conversation it turns out that the wife has left him). The example in (22d) refers to a priest from Norway that the listener does not know; the PD seems to be used to reinforce how unusual the man is (speaking both English and Norwegian). The example in (22e) is slightly different, as the speaker clearly knows his own brother personally. The use is, however, still distal; the brother is unfamiliar to the listener and has not been mentioned explicitly previously in the discourse.

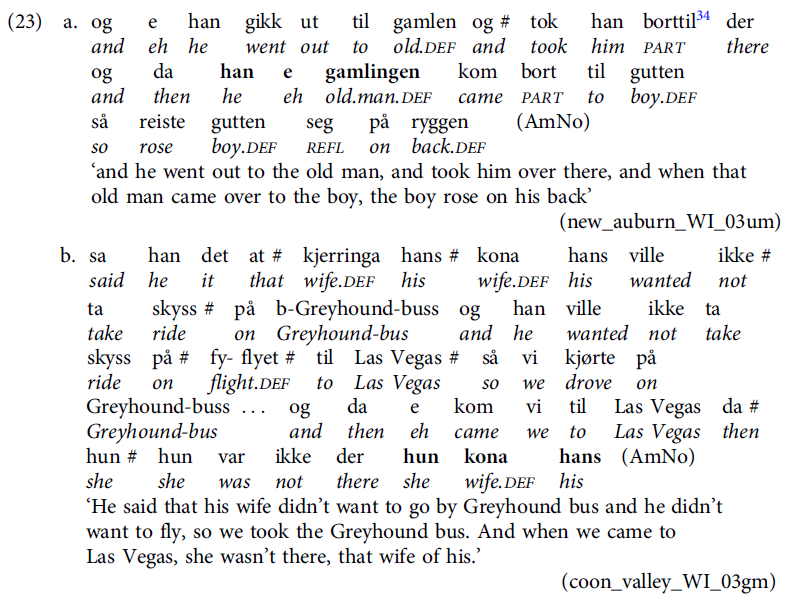

As shown in Section 2, PDs in EurNo are not only used to introduce referents, but also with referents that have been mentioned previously in the discourse (see Johannessen Reference Johannessen, Næss, Margetts and Treis2020; recall that this is less common in Swedish). This use is found in AmNo, too; two examples, one from the 1940s and one from the 2010s, are given in (23) ((23b) = (22c)):

In (23a), recorded in 1942, the speaker is talking about a father and a son that were well known in the local community, but that he does not seem to be personally close to. The psychological distance is emphasized by the fact that he refers to the father as gamlen and gamlingen ‘the old man’; this comes across as mildly derogatory. The father has already been introduced into the story when the PD is used to re-activate him as a referent. In (23b), a PD is again used with a referent that is not personally known by the speaker or listener (and who is never mentioned by name). The PD reminds the reader that the referent is previously mentioned and part of the background.

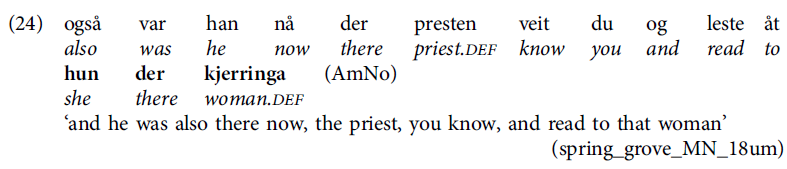

There are no examples of PDs with definite noun phrases with adjectival modification in our heritage language data.Footnote 35 Since we do not have access to acceptability judgments for AmNo, we cannot know for certain that PDs in AmNo are incompatible with a prenominal determiner or demonstrative, as they are in EurNo (see Section 2.1).Footnote 36 However, given that the usage in AmNo looks very much like EurNo, rather than EurSwe, we expect AmNo PDs to have the same syntax as PDs in EurNo; nothing suggests grammatical change with respect to PDs. Notably, the fact that AmNo PDs can be reinforced with a locative der ‘there’ as in (24) also corroborates the analysis of the PDs as proper demonstratives; the example in (24) was recorded in the 1940s.

Overall, the conditions on the use of PDs in the AmNo data are very similar to what we find in homeland Norwegian. Thus, the picture that emerges from the Norwegian CANS data is one of continuity. PDs clearly exist in present-day AmNo, and they are used in the same way as in the EurNo baseline. Moreover, we can trace the use of PDs among heritage speakers several generations back; they are attested both in the 1990s and in the 1940s. In formal syntactic terms, there is no reason to posit any special structures for AmNo. This is in line with previous studies which suggest a relatively high degree of stability in the structure of AmNo nominals (see Anderssen et al. Reference Anderssen, Lundquist and Westergaard2018, Kinn Reference Kinn2020a, van Baal Reference van Baal2020).

4. Heritage language perspectives

In this section, we consider some of the results of our study from a heritage language perspective. In Section 4.1, we discuss the transmission of PDs over generations in a heritage language context, in light of the Interface Hypothesis (IH). In Section 4.2, we argue that the findings from AmNo can shed light on the division of labor between syntax and pragmatics, and the syntactic representation of speech act participants.

4.1 Transmission of PDs across generations and the Interface Hypothesis

In Section 3 above, we showed that PDs are attested in present-day AmNo; we argued that they have been present throughout the history of this heritage variety, and that they have the same syntax and use as in EurNo. This implies that PDs have been transmitted across generations. We noted some quantitative differences between the samples (the samples from LIA and early AmNo have a higher proportion of PDs than present-day AmNo); however, as PDs are a low-frequency phenomenon in all of the samples, and as there are a number of factors that could potentially influence the quantitative comparison between these data sets (see Section 3.2), we cannot draw any firm conclusions about the status of PDs in the grammar of AmNo based on this. Instead, we contend that the stability that we can observe in terms of the way PDs are used, down to the more subtle details that are particular to Norwegian PDs, is remarkable.

PDs convey meaning related to speaker-perspective and attitudes; thus, their distribution is governed by factors that can be thought of as pragmatic, in addition to syntactic conditions. Previous studies have argued that phenomena at the interface between syntax and other cognitive domains are vulnerable in bilingual speakers (see Sorace Reference Sorace2011 for an overview and also Benmamoun, Montrul & Polinsky Reference Elabbas, Montrul and Polinsky2013:161–166 and references therein).Footnote 37 Interface phenomena, for example the choice between overt and null subjects in a null-subject language like Italian, which relies on pragmatic/information-structural notions such as topicality, are less likely to become fully acquired by L2 speakers (e.g. Sorace & Filiaci Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006), and more likely to undergo attrition in L1 speakers; Tsimpli et al. (Reference Tsimpli, Sorace, Heycock and Filiaci2004) found that L1 Italian speakers who had near-native competence in English, and a minimum of six years of residence in Britain, would overextend the use of overt subjects in Italian. The view that interface phenomena are vulnerable is referred to as the Interface Hypothesis (IH) (the term was first coined by Sorace & Filiaci Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006). On the face of it, retention of PDs, with their subtle conditions for use, would seem like a counterargument to the IH. However, we suggest that this is not necessarily the case, and that the stability of PDs in AmNo does not need to be at odds with the predictions of the IH. Instead, it can contribute some refinement in terms of distinguishing between different pragmatics-related phenomena.Footnote 38

We take the stance that not all pragmatics-related phenomena are equally vulnerable, and we propose that the stability of PDs in heritage Norwegian can be understood in the context of a different aspect of their meaning, namely deixis. Johannessen (Reference Johannessen2008a) describes PDs as demonstratives that, similar to other demonstratives, encode distance from the speaker, i.e. a deictic perspective. What distinguishes PDs from other distal demonstratives is the dimension along which distance is encoded; this dimension is psychological rather than spatial, but that does not alter the deictic nature of these demonstratives.Footnote 39 While phenomena at the syntax-pragmatics interface are generally considered to be vulnerable in heritage languages, expressions of deictic relations have been shown to be robust (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018:63–65). Polinsky (Reference Polinsky2018) relates this to saliency and illustrates the point with examples from heritage English and other heritage languages, in which demonstratives, and also inherently indexical grammatical categories such as tense and person (in particular the persons relating to speech participants), are stable, while, for example, aspect, voice and number are more vulnerable. The argument can be generalized to Norwegian PDs, whose demonstrative nature is very clear. It is possible that the deictic properties of these PDs have contributed to their retention.

The stability of PDs in AmNo can also be interpreted in a more general context, which has more fundamental theoretical implications: if one considers notions such as speaker perspective to have a structural representation in syntax, then the stability in the way PDs are used comes across as less surprising than if they are treated as more or less purely pragmatic phenomena. This is the topic of the next section.

4.2 PDs in AmNo and the representation of speech act participants

The behavior of PDs in AmNo, and in particular the stability of the conditions on their use across generations, can potentially inform the discussion about the division of labor between syntax and pragmatics. As noted in Section 4.1, retention of PDs, with the same, subtle properties as in EurNo, is perhaps not what one would expect, given the IH and the observation from other studies that pragmatics-related phenomena are vulnerable in heritage languages. However, a recent line of research within generative grammar, revisiting and revising Ross’s (1970) Performative Hypothesis, argues that the Speech Act, and its participants (Speaker, Hearer), traditionally thought of as pragmatic notions rather than narrow syntax, are structurally encoded in the syntactic spine; on the clausal spine, see e.g. Tenny & Speas (Reference Tenny, Speas and Maria Di Sciullo2003), Giorgi (Reference Giorgi2010), Hill (Reference Hill2014) and Wiltschko & Heim (Reference Wiltschko, Heim, Kaltenböck, Keizer and Lohmann2016); on the nominal spine, see e.g. Ritter & Wiltschko (Reference Ritter, Wiltschko and Dmyterko2018, Reference Ritter and Wiltschko2019). Sigurðsson’s (Reference Sigurðsson2011, Reference Sigurðsson2014) model relates the representation of speech act participants (logophoric features) to phasehood, and it can thus be applied to both the clausal and the nominal domain. Our formal analysis (Section 2.1) draws on some of the ideas in this framework (in particular, Sigurðsson’s logophoric features). For the purposes of this article, we do not go into any further detail about the various technical implementations that have been proposed. Instead, the point we would like to make is the following: If one accepts the idea that pragmatics-related phenomena are vulnerable in heritage languages while core syntax is generally more stable, then the stability of PDs could be taken to corroborate the notion that PDs, with their speaker and hearer-related interpretive effects, are encoded in syntax. More research is required to establish this connection, but regardless of the outcome, this shows that heritage language data can generate hypotheses and shed new light on fundamental questions in theoretical syntax and linguistics more generally.

5. Conclusion and outlook

In this paper, we have argued that although PDs in Norwegian and Swedish look superficially similar, they differ both with respect to syntax and usage. Building on Johannessen’s (Reference Johannessen2008a) seminal work, we have proposed a modified analysis, whereby PDs in Swedish are in fact not proper demonstratives, as they are in Norwegian. Importantly, in Swedish, the PD can combine with an ordinary demonstrative; this is not possible in Norwegian. Moreover, unlike Norwegian PDs, Swedish PDs do not seem to have all the pragmatic functions of a demonstrative and do not necessarily have a distal interpretation. We have therefore suggested that the Swedish PD is best characterized as a pronoun rather than a demonstrative, but without the full set of formal features of pronouns (see Josefsson Reference Josefsson and van Riemsdijk1999, Holmberg & Nikanne Reference Holmberg and Nikanne2008). In addition, we propose that it has logophoric features that activate knowledge that is shared between the speaker and addressee. For Norwegian, we have maintained the main features of Johannessen’s (Reference Johannessen2008a) analysis, and treat PDs as true demonstratives. Our corpus studies show that PDs can be attested in both Norwegian and Swedish as far back in time as the late 19th/early 20th century, i.e. at the time of mass emigration from Scandinavia to the United States, with the same properties as in the present-day languages.

Previous work on heritage Norwegian has shown a high degree of stability in the nominal domain (see Anderssen et al. Reference Anderssen, Lundquist and Westergaard2018, Kinn Reference Kinn2020a, van Baal Reference van Baal2020), and this is also what we find with respect to PDs. American Norwegian has retained PDs across several generations; PDs can be attested both in older and recent recordings, and they are used in the same way as in the homeland baseline, down to the subtle details that distinguish Norwegian PDs from Swedish PDs. On the face of it, this seems to go against the Interface Hypothesis (IH) (e.g. Sorace & Filiaci Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006, Sorace Reference Sorace2011), which predicts that phenomena at the syntax-pragmatics interface are vulnerable. We do not, however, suggest that IH should be discarded; instead, we argue for a distinction between different (apparent) interface phenomena, and we suggest that PDs have some special properties that contribute to stability. One such property is deixis, which has been shown to be stable in heritage languages (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018:63–65). Moreover, our syntactic analysis draws on the idea that speech act participants (Speaker and Hearer) are encoded in narrow syntax as logophoric features (Sigurðsson Reference Sigurðsson2011, Reference Sigurðsson2014). In the context of this assumption, it is not surprising to see transmission of PDs over generations of heritage speakers. In fact, given the IH, the retention of PDs over generations in AmNo can be seen as an argument in favor of the structural representation of speech act participants in syntax, and our study serves as an example of how heritage language data can feed into more general areas of research, beyond Heritage Linguistics.

Several questions remain, also more specifically with regard to Scandinavian PDs. While we have observed some evidence for PDs in American Swedish, the available data is too scarce to draw any conclusions. With respect to European Swedish, there is also a lack of spoken language corpora that are large enough. Another issue is the interaction between PDs and other available demonstratives in the different varieties of Scandinavian. For instance, Swedish appears to have a general preference for den här/där ‘this/that’, while the use of the Norwegian equivalents (with human referents) seems more restricted; it seems likely that the use of PDs depends in part on this. We have, however, not systematically investigated the use of all demonstratives with human referents. This remains to be studied in further detail; such investigations may provide a more complete picture of PDs and nominal determination in general in both homeland and heritage Scandinavian.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank three anonymous reviewers, the NJL guest editors, Janne Bondi Johannessen and the audiences at WILA 11 (University of North Carolina-Asheville) and SyntaxLab (University of Cambridge). Any remaining errors are our own. Kari Kinn’s work was funded by the Research Council of Norway, project 301114 ‘Norwegian across the Americas’.