This article will examine Juan Cobo's copy and translation of Mingxin baojian 明心寶鑑 (Precious Mirror for Enlightening the Mind) (circa 1590).Footnote 1 This extant manuscript of this document is in the Biblioteca Nacional of Spain.Footnote 2 It is believed that Juan Cobo, a Spanish missionary who stayed in Manila between 1588 and 1592, collaborated with Chinese helpers in his parish in Parián to complete the work. Following the Sino-Iberian tradition of Sinology, the title of Cobo's manuscript will be shortened to BSPC based on the transcribed title in the Minnan 閩南 dialect, Beng Sim Po Cam, instead of Mingxin baojian in Mandarin Chinese (Figure 1).Footnote 3 This article's focus is twofold: first, it deals with the close relationship of the BSPC to Chinese print culture, particularly the Fujian book market in China; secondly, it focuses on Cobo's exercise of intercultural translation in his manuscript. To that end, we will examine his translation and comments on Buddhist practices and beliefs, such as the belief in transmigration, as well as his understanding of Chinese folklore concerning dragons.

Figure 1. The front page of Beng Sim Po Cam. Source: Juan Cobo, Libro chino intitulado Beng Sim Po Cam que quiere decir Espejo rico del claro coraçón, o Riquezas y espejo con que se enriquezca, y donde se mire el claro y limpio coraçón, MS No. 6040, Biblioteca Nacional de España.

We will examine the text presented in the BSPC manuscript, including Cobo's Spanish translation and his marginalia comments, as well as the original Chinese text. By including Cobo's marginalia comments, we provide a new perspective on the cultural implications of the BSPC, since the existing scholarship on Cobo's translation has so far shied away from this issue by simply stating that Cobo, like any other sixteenth-century Catholic missionary in America, Africa, or Asia, had some limitations when translating Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, or Chinese popular culture for the Habsburg court in Spain and the Iberian readership. A close reading of the marginalia will shed light on the complexity of the cultural exchanges between the Chinese and Spanish cultures in Manila and Chinese culture in Fujian, China.

In addition, studying the marginalia is fundamental to contextualising the BSPC's value. It is said to be the first work translated into a European language.Footnote 4 After its completion, Cobo's friend and superior, Miguel de Benavides, took it back to Spain and presented it to the crown prince and future king, Philip III (1599–1621) on 23 November 1595. Yet many facets of the manuscript indicate that the work was done in a rush and that Cobo, still learning Chinese and newly arrived in Manila, had limitations placed on his translation due to time constraints, competition with other religious orders, intellectual biases, and, of course, the insurmountable difficulties he faced in his first encounter with the Chinese cultures of both Manila and Fujian.Footnote 5

Juan Cobo's manuscript of the BSPC and the Fujian book market

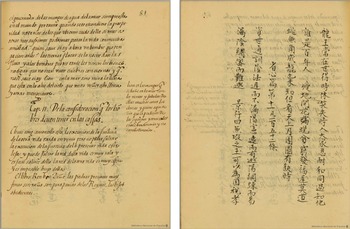

Juan Cobo was a Spanish Dominican missionary, whose work enriched early Sinology and contributed to Sino-Iberian relations at the time.Footnote 6 He travelled to Mexico in 1586 and later to Manila in 1588. It was in Manila that he gained access to a copy of the Chinese moral primer Mingxin baojian and completed his translation with the help of Chinese collaborators. Concerning Cobo's BSPC manuscript, it contains both the Spanish translation and the original Chinese text. The Spanish translation is on the recto of the folios, while the Chinese text is on the verso (Figure 2). The manuscript does identify the edition on which the translation was based, The Newly Printed Mingxin baojian with Illustrations, Corrections, and Phonetic Annotations (Xinkan tuxiang jiao'e yinshi Mingxin baojian 新刊圖相校訛音釋明心寶鑑) compiled by Fan Liben.Footnote 7 But unfortunately, this edition of the Chinese original is no longer extant, and there is no way to find out when and where it was published. Some scholars, such as Robert Ellis, speculate that it may have been one of the books brought back by the Augustinian friar Martín de Rada to Manila from Fujian, China;Footnote 8 alternatively, Cobo could have obtained it from members of the Chinese community in Parián or from his Chinese teacher or teachers.

Figure 2. Prologue to Mingxin baojian, written by Fan Liben and copied by one of Cobo's Chinese collaborators. Source: Cobo, BSPC (f. 4r/v). Our notes in red refer to the content in Table 1.

Considering that at this point there is no certainty about how Cobo obtained a copy of the Mingxin baojian, we seek to provide some information on the version of the Chinese book that Cobo could have used for his translation. Based on our close examination and comparison between the manuscript and a Jiajing edition (1553) of Mingxin baojian in China,Footnote 9 we found that the Chinese text in Cobo's manuscript was shorter and had some textual corruptions or variants. For example, the first chapter of the Mingxin baojian, ‘Jishan pian’ 繼善篇 (On Continuity of Kindness), has fewer entries in Cobo's manuscript than that in the Jiajing edition. While in the Jiajing edition there are 47 entries of aphorisms or moral sayings, in Cobo's BSPC there were said to be only 44 entries. However, this information is not totally accurate: after a careful comparison, in Cobo's manuscript we only found two missing entries not three, which were skipped on f. 14v of the BSPC. The first is 太公曰: ‘懦必壽昌,勇必夭亡’, the second《書》云: ‘為善不同,同歸於理。為政不同,同歸於治。惡必須遠,善必須近’. As we will see later, this method of shortening the length of a book was a common practice among the printers in Jianyang 建陽, Fujian. But there is one further aspect that connects the copy used by Cobo to the printing practices in the south of China.

As reproduced in Figure 2 and Table 1, the manuscript has a couple of textual variations on the first page of the copied Chinese text regarding Fan Liben's preface. In Table 1, we expound more about the nature of these two variations, but they are by no means the only ones in the whole manuscript.

Table 1. Two examples of textual variants between the Jiajing edition and Juan Cobo's BSPC.

These differences between the Chinese text in Cobo's BSPC and the Jiajing edition can be understood in the context of print culture in Fujian in the late Ming. Fujian had been a centre for Chinese printing since the Song dynasty (960–1279), known especially for the books printed in Jianyang, a district in Minbei, north of Fujian. By the late sixteenth century, the book market in Fujian had an abundance of printed books on various topics, but their quality had deteriorated. Due to the greed of commercial publishers, to lower the cost of printing, many crude copies of books were printed. Lucille Chia, in her analysis of the Jianyang book trade, explains that commercial publishers employed editors, collators, block-carvers, printers, and bookbinders to produce different imprints of a book so they could maximise their profits.Footnote 10 While in Fujian, even Martín de Rada was baffled by the inconsistency and inaccuracy of the information contained in various imprints of Chinese books.Footnote 11 For a popular book such as Mingxin baojian, there would have been several editions on the Fujian market before the 1590s.Footnote 12 It is very plausible that Cobo's translation was based on such a crude edition of the book printed between the years 1393 and 1588, and brought by Chinese immigrants from Fujian to the Philippines, or by the Spanish expedition to Fujian. In fact, by the time Cobo arrived in Manila, the volume of commercial traffic with Fujian was impressive. As Pierre Chaunu indicates, in the years 1588, 1591, and 1596 the vast majority of boats that arrived in Manila were from China, amounting to 48 in 1588, 21 in 1591, and 40 in 1596.Footnote 13

According to Fidel Villarroel, the early Chinese immigrants included seamen and traders, but there were also some educated people among them, even literati: ‘There was a high rate of literacy among them, more than what Cobo thought at first sight.’Footnote 14 But this high literacy rate might have been a pretence on the part of the Chinese. In his letter, Cobo detailed the conditions of the Chinese whom he saw and noted their possession of Chinese books they had brought with them from China to Manila.Footnote 15 It is likely that while most of the Chinese settlers in the Philippines were not well educated, they were highly trained in various forms of craftmanship. The Chinese woodblock printing method spread beyond the borders of China, arriving in the Philippines with the Chinese immigrants, who ended up being designated by the Spaniards as ‘Sangleys’, instead of the previous name of ‘chins’, ‘chinas’, or ‘indios’. The number of Chinese residents and temporary traders in Manila grew enormously due to the annual trade between China and Manila.Footnote 16 It was this group of Sangleys who collaborated with Cobo in his translation, and also in his writing of Shilu, a book that we will discuss later in this article. Among this group of Sangleys who were involved with the early Philippines incunabula was Keng Yong, who was especially noted for his contribution to the printing of Doctrina Christiana, another book commissioned by Dominican missionaries.Footnote 17

Concerning the presentation of the Chinese text in Cobo's translation, several observations are worthy of further attention. The Chinese text, transcribed on the reverse side of the Spanish translation (Figures 2 and 4), was written by different hands, most likely by several Chinese whose literacy levels varied a great deal. Compared to the beautifully executed, artistic handwriting in Spanish, the Chinese characters show inconsistency and non-uniformity, both in style or in alignment. The quality of the Chinese calligraphy throughout the BSPC is uneven. In some chapters the characters were highly stylised in the kaishu 楷書 calligraphic style as if they were written by a learned scholar, such as in the first chapter; the characters in later chapters, such as those in Chapter 11, were poorly executed. Sometimes it seems that each chapter was written by a different hand, but such a statement should not be made hastily and more research should be done on the calligraphic variations, since Borao argues that some of the calligraphic variations are related to the subdivisions of the booklet.Footnote 18

As for the accuracy and content of the copied Chinese text, there are mistakes. As indicated earlier regarding Fan Liben's preface (Figure 2 and Table 1), these mistakes may have resulted from a faulty copy of the book available in the Philippines that was used to build Cobo's BSPC, or from the haste and negligent work of a copyist. One can stipulate that the different styles of calligraphy seem to indicate that Cobo and his co-religionists had a medieval monastic system of book-copying—a scriptorium—in Parián. For now, in that scriptorium of sorts, the number of Fujianese or Sangley artisans who were involved in copying the Chinese text Mingxin baojian into the BSPC is not yet certain, and their names might never be known. The Chinese text was written to correspond to the Spanish text, and one wonders if the inclusion of the Chinese text was not an afterthought by the translator in order to give the content an exotic and authentic flavour, which might impress the Habsburg prince back in Spain and compete with other translations, such as Ruggieri's.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, the infelicities in the text may indicate that the copying of the Chinese text was done in a hurry in order to complete the manuscript before it was sent to Spain.

The manuscript has a profound relation with Chinese printed books, especially with the Shilu that Cobo himself made possible. The connection between Cobo's manuscript and Chinese printed books can be proven further by the letter of his superior Friar Miguel de Benavides, when presenting Cobo's translation to the Spanish court. Benavides states how books were valued by the Chinese and thus, to access the Chinese people, one must be familiar with their books:

The Chinese judge their great and true riches to be not gold, nor silver, nor silks, but books, and wisdom, and the virtues and just government of their republic: this they esteem, this they elevate, this they glorify, and it is what well-composed people speak of in conversations (of which there are many). (Our translation from Spanish into English)

Juzgan los chinos por sus grandes y verdaderas riquezas, no el oro, ni la plata, ni las sedas, sino los libros, y la sabiduría, y las virtudes y el gobierno justo de su república: esto estiman, esto engrandecen, de esto se glorian y de esto tratan en sus conversaciones la gente bien compuesta (que es mucha).Footnote 20

Because of their admiration for Chinese printed books, Chinese book markets, and the education level of some Chinese, the early Spanish missionaries in Manila busily collected information and wrote about Chinese life, which started a tradition of Spanish writing on China ‘that preceded northern European sinology and profoundly influenced the West's understanding of East Asia’.Footnote 21 Juan Cobo appears to be, at least, connected with two remarkable events: first, he translated Mingxin baojian. Secondly, he contributed to the Chinese-Filipino incunabula by imitating and participating in Chinese book printing.Footnote 22 Cobo wrote a theological and scientific text Bian zhengjiao zhenchuan shilu 辯正教真傳實錄 (Testimony of the True Religion) which, using the Chinese woodblock printing technology available in Parián in Manila, was published posthumously in 1593 (hereafter this book is referred to as Shilu). Shilu was one of the first books to be written in the classical Chinese style and printed in the Philippines.Footnote 23 Philip Clart sees Cobo's effort in translating Mingxin baojian as preparation for his writing of Shilu for a Chinese audience.Footnote 24

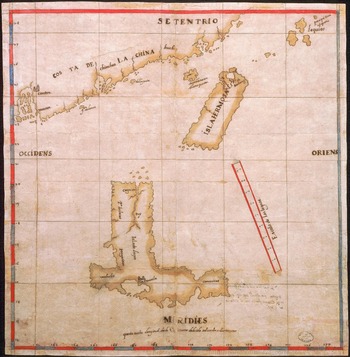

As we will see in the textual analysis below, the two works are complementary. Cobo's manuscript translation of the BSPC and his printed Shilu are connected, and valuable for the purpose of examining his understanding of Chinese culture and classics, as well as how well he incorporated his learning of Chinese into preaching Western religion and knowledge among the Chinese settlers in Parián. In addition, as physical artefacts, both his translation in manuscript form and Shilu in print offer valuable information on the global reach of Chinese printing in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, indicating that there was a real cultural exchange in the backwaters of mainland China and, more specifically in the context of this article, in the ‘barbarian little kingdom of Luzon’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Luzon in the lower part, Formosa in the middle, and the Fujian coastal line in the upper part of this map. Source: ‘Discrepción [sic] de la Isla Hermosa dirigida por Hernando de los Ríos Coronel al Rey con carta fecha en Manila a 27 de junio de 1597’. ES.41091.AGI//MP-FILIPINAS, 6. Archivo General de Indias.

The marginalia in Cobo's BSPC manuscript

Along with the translation, Cobo added his commentary, though on limited occasions, in the side margins of the pages (Figure 4). This can be considered as a sign of his efforts to produce a faithful translation, albeit that the comments filtered through his cultured lenses are not completely aseptic. There are altogether 26 commentary notes throughout the 153 folios of the translation. Not all of Cobo's commentaries are fully readable due to the manuscript's binding. In Carlos Sanz's 1959 copy of the manuscript, Cobo's marginalia were transcribed, but the transcriptions cannot be fully trusted since Sanz did not indicate when some words were incomplete or missing. When the commentary could not be read, he simply filled in the blanks according to his own understanding. The more recent edition by Liu Li-Mei (2005) indicates faithfully what can and what cannot be read in those margins. In our study, we consulted the digital copy of the original manuscript kept in the Biblioteca Nacional de España, as well as the modern editions by Sanz, Ollé, and Liu.

Figure 4. Cobo's commentary on ‘Dragon King’ in the right margin of his translation. Source: Cobo, BSPC (f. 81r).

Most of Cobo's comments explain important Chinese figures, concepts, and ideas that would be difficult for a sixteenth-century Westerner to understand, such as the metaphorical use of dragons in Chinese poetry and common sayings.Footnote 25 Considering the readership of the manuscript, Cobo's translation and commentary relied heavily on cultural knowledge that would have been familiar to his fellow countrymen. Yet, at times, he was reluctant to draw a comparative view between the Chinese and European cultures, or he failed to recognise the similarity in the two cultures concerning a certain concept. This gives the impression that some Iberian ethnocentrism is at play in the cultural exchanges in his translation.Footnote 26 Here we are going to focus on three instances in the BSPC manuscript: his commentary notes on Chinese monks, dragons, and reincarnation. We will also bring Shilu into the discussion because his understanding of certain Chinese concepts is largely consistent in both works.

Concerning Buddhist monks, in a couple of places in the BSPC, Juan Cobo translated the term heshang 和尚 into ‘sacerdote’ (a Catholic priest) and ‘religioso’ (man of the cloth or clergyman).Footnote 27 In Shilu, he rendered the Catholic bishop in Manila into heshang wang 和尚王 (lit. the king of Buddhist monks). And he himself was called Gao Muxian sengshi 高母羨僧師 (Catholic priest Gao Muxian). Gao Muxian was the Chinese name Cobo adopted and seng 僧 is another Chinese term for Buddhist monks. These several instances of cross-cultural translation might indicate deeper issues such as the complex negotiations that were taking place between Asian cultures and the recently arrived ‘barbarians’ to the kingdom of Luzon. Cobo's adoption of the Buddhist terms ‘heshang’ and ‘seng’ for religious practitioner can be interpreted from the point of view of his missionising efforts to draw a certain affinity between the beliefs in Buddhism and Christianity among the Chinese settlers in Manila.

Yet, Cobo's attitude towards the followers of the Buddha was nevertheless disparaging. In his commentary note on Rulai yizang 如來一藏 (sutras of Tathāgata, a doctrine indicating the potential of all sentient beings to become Buddha), Cobo explains, ‘these are the books of Sequia because it is him who the sorcerers of China follow’.Footnote 28 While ‘Sequia’ is Cobo's transliteration for the two syllables ‘shakya’ in the name of Buddha Shakyamuni 釋迦摩尼, ‘sorcerers’ is his rendition of Buddhist monks.Footnote 29 The connotation of the word ‘sorcerer’, someone who is seemingly related to witches and witchcraft, devalues the soundness of the foundation of Buddhist doctrines and belittles the leading figure of the Buddhist pantheon. Disparaging religious elites of India, China, and Japan is quite common in the missionary writings of the time. For instance, Francis Xavier did the same with the brahmins in India, saying that ‘they are the most perverse people in the world’ in his letter dated 15 January 1544 to his co-religionists in Rome.Footnote 30 Five years later, in his letter composed on 5 November 1549, Xavier did not portray the Buddhist monks of Japan in a much better light, referring to their public inclination to pederasty with the young boys that they taught how to read and write; he also commented on monks and nuns living together and the ensuing pregnancies and abortions.Footnote 31 The religious elites of Asia were quite often described as devils, sorcerers, and paedophiles. In this regard, Juan Cobo reflects the values and motifs of his times.

Moving from humans to myths, Cobo also had difficulties in translating the term long 龍 for ‘dragon’, a fundamental mythical animal that symbolises imperial power in Chinese culture. In the BSPC, he translated the Chinese term long into ‘dragon’ more than once, but he danced around the idea of using different transliterations for the term. Thus, we find lion, lon, and cau to phonetically designate ‘dragon’ and ‘flood dragon’ in the BSPC. Not by coincidence, the word ‘dragon’ was never used in the Boxer Codex either, even though the manuscript contains a remarkable number of dragon iconographies. How are we to understand the resistance of early Western writers on China to using their knowledge of classical Greek and Roman mythology to compare the Chinese dragon king to Poseidon or other deities, or of the Christian saint tradition to invoke the figure of Saint George, the dragon slayer? Cobo's translation of a poem entitled ‘Jiezi shi’ 誡子詩 (‘Admonition to My Sons’) in Mingxin baojian can shed some light on this issue.

‘Jiezi shi’ was composed by Pang Shangchang 龐尚長 (Style name Denggong德公, ?–third century ad).Footnote 32 The poem warns about the danger of gambling and urges its readers to understand that changes in one's fortune are constant, drawing an analogy with the waxing and waning of the moon, and twice invoking the image of a dragon to emphasise the dichotomy between the Chinese concept of ‘gaining the opportunity’ (deshi 得時) and ‘losing the opportunity’ (shishi 失時) in terms of achieving prosperity in life. In Cobo's BSPC, part of the poem reads as follows:

The Dragon King of the Eastern Sea remains in the world constantly. When you are at your fortunate moments do not laugh at those who are at their unfortunate moments. People endure and live together in harmony. No one can predict who can live to one-hundred-year-old. Flowers blossom late on barren land, and those who are poor achieve prosperity late in life. Don't say a snake has no horns, you don't know [one day] it might transform into a dragon. Just look at the moon in the sky, after it is fully waxed, it starts waning again. (Our translation from the Chinese in the BSPC)

東海龍王長在世,得時休笑失時人。大家忍耐和同過,知他誰是百年人。瘦地開花晚,貧窮發福遲。莫道蛇無角,成龍也未知。但看天上月,團圓有缺時.Footnote 33

And here is Cobo's translation of this part of the poem:

The governor of waterspouts is always in the world. Therefore, when prosperity would hide from you do not laugh at those who fell from favor. If we can endure each other, we will live in great concord [lit. friendship]. Who knows is now there is a centenarian? Megger lands at night give flowers, poor men late receive their goods. Do not say that you have never seen snakes with horns, and that it is not known if there is lion in the sea; on the contrary look at the moon in the sky which sometimes is full and other times is waning. (Our translation from the Spanish text in the BSPC)

El gobernador de las mangas de agua de la mar siempre está en el mundo, por tanto, cuando se te escondiere la prosperidad, no te rías de los que hubieren caído de ella. Si unos a otros nos sufrimos podremos pasar la vida con mucha amistad. ¿Quién sabe si hay ahora un hombre que tenga cien años? Las tierras flacas de la noche dan las flores y a los hombres pobres tarde les vienen los bienes. No digas que no se han visto culebras con cuernos y que no se sabe si hay lion en la mar, si no mira la luna que está en lo alto del cielo que unas veces está llena y otras menguante.Footnote 34

It is evident that Cobo failed to understand the dichotomy between ‘gaining the opportunity’ and ‘losing the opportunity’. Furthermore, he made a commentary on ‘lion’, a transliteration for Amoy vernacular long, to dismiss Chinese people's claims that the storms on the sea are caused by the ‘flood dragon’.

‘Dragon waterspouts’ (longjuan feng 龍捲風) are made by the wind on the sea, about which Chinese people fantasise many things. Here it means that the downfall of the gamblers is nothing extraordinary, but quite ordinary. (Our translation from the Spanish text in the BSPC)

lion es las mangas que se hace en la mar con los vientos, y fabulan de ellas muchas cosas los chinas[sic]; y quiere aquí decir que la perdición de los jugadores y otros tales es cosa ordinaria y no extraordinaria.Footnote 35

To Cobo, storms at sea are caused by wind (‘los vientos’), not by a mythical dragon (longjuan feng 龍捲風), and the downfall of gamblers is self-inflicted because of their greed, thus harking back to the beginning of Pang Degong's poem where he warns his sons of the danger of losing one's fortune due to gambling.Footnote 36 The Chinese belief in dragons that can cause the rise and fall of waterspouts in the sea, and the belief that the dragon is the omnipotent power behind all unpredictable changes in one's fortune, are nothing but ridiculous fabulations—using his own words ‘son dos animales marinos de que fabulan ridículamente’.Footnote 37 In Shilu, when it comes to explaining the mysterious force behind one's various misfortunes, Cobo offers further insights from a biblical point of view to assert that we will receive God's punishment if we rebel against God's will, even though, at times, dragons and other reptiles were seemingly the ones to cause harm.

God transformed Heaven and Earth. His idea of creating the ten myriad things was to foster those who cultivate and capsize those who topple. That with which he tenderly cares for the sentient humans and animals holds no partiality among them. Since the human ancestors rebelled against God, this meant that humans did not obey God. Thus, animals also did not obey humans. Therefore, those among the birds and animals such as tigers, leopards, snakes, and scorpions hidden in the mountain; dragons and crocodiles hidden under the water sometimes cause harm and spread disasters in the world. This is God's punishment and admonishment, revealing his mighty power to us in order to make us respectful and diligent to take good care of things and not dare to act rashly and blindly.

天主化天化地、生成萬物之意:栽者培之;傾者覆之。其所以厚生民物者,何私德於其間哉?自因人祖造誡天主,是人之不順於天主者,物亦不順於世人。故禽獸之害人者有:虎豹蛇蝎之隱於山者;有蛟龍鱷魚之藏於水者,或貽害流禍於斯世者,此誠夫主寓懲戒之,明威示吾人,尊勤勉之善事,使其無敢輕舉而妄動.Footnote 38

Cobo adopted a similar strategy—resorting to the doctrines of Christianity—when he approached the translation of the Buddhist concept of transmigration. In translating the popular saying:

When one listens to kind words, one will not fall into the three evils;

When one has kind desires, Heaven must follow them.

耳聽善言,不墜三惡,人有善願,天必從之.Footnote 39

Cobo's commentary note on san'e 三惡 (the three evils) reads: ‘the three evils are theft, adultery, and lying’. This is either misleading or an intentional appropriation of the belief of transmigration after death into the core beliefs of Christianity. According to Buddhist beliefs, san'e refers to the three unfavourable paths of transmigration after a person's death.Footnote 40 Those who did not accumulate good karma during their lives will fall to the three lowest realms of rebirth and existence: animals, hungry ghosts, or hell. However, Cobo distances himself from the orthodox Buddhist notion of san'e and frames his explanation within the catechism of Christianity, particularly, three of the Ten Commandments:

Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Thou shalt not steal.

Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.

As a Counter-Reformation missionary, Cobo's comment on the notion of san'e debunks Chinese people's religious belief in Buddhism. This was not the only time when Cobo dealt with the transmigration of the soul. In Shilu, he further disputes the belief in transmigration:

I have heard about a heresy that says, ‘the soul of men, once men die, may enter the bodies of animals, and then be reborn into the human world’. This is really a ridiculous statement of falsehood, and it cannot be believed. Our soul is united to our own body. How can our souls be united to the bodies of animals? If that is the case, then the animal species would be the same as the human species, and the animals’ nature would be the same as the nature of our human beings. The nature being the same, the species would be also the same, thus men and the myriad of things would be confused.

吾有聞異端之說曰:人之魂靈既死,或進於禽獸之身,而回生世間。誠乃荒誕之詞也,不可信也。夫吾人自己之魂合乎自己之身,安有吾人之魂而合乎禽獸之身哉?若以為然,則禽獸之異類乃吾身之同類也;禽獸之異性則吾人之同性也。性同類亦同,人物亂矣.Footnote 41

Cobo deemed the Chinese belief in transmigration to be heresy, and his longing to Christianise Chinese beliefs is evident. As we know from Jose Antonio Cervera's analysis, Cobo's use of Chinese philosophical concepts weakened the ideological apparatus of Shilu. Cervera discusses Cobo's use of some concepts, such as wuji 無極 (primordial universe) and taiji 太極 (Supreme Ultimate), among others, and claims that the misuse of Chinese concepts might have been the reason for the book's poor reception.Footnote 42 Generally, missionaries were involved in dispelling what they considered to be false beliefs about the human soul, spirits, reincarnation, and so on. The categories used by Cobo to explain Chinese religions are a transposition of a religious debate between Buddhism, popular beliefs, and Christianity. Some famous examples were set by Francis Xavier, who described in 1549 how his conversations with ‘bozos’ in Japan revealed that they were not certain about the immortality of the soul,Footnote 43 and by Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault, who indicated between 1580 and 1610 that the Chinese Buddhists—the ‘sciequia ou omitofo’—had appropriated the Pythagorean notion of transmigration of the soul and added some other ‘lies’ to it.Footnote 44

Conclusion

To conclude, Cobo's BSPC is a remarkable work and worthy of study for several reasons. It contains a Chinese version of the Mingxin baojian that is a reflection of a ‘crude’ edition of the book printed in Fujian China. It was made available to Juan Cobo in Manila thanks either to Rada's mission to Fujian or the Chinese immigrants who settled in Manila. Compared to a 1553 Jiajing edition, Cobo's copy of the Chinese text has textual variants, as demonstrated by the examples found in Fan Liben's preface and the first chapter. Cobo's manuscript contains the calligraphic work of a host of Chinese or Sangleys. The marginalia in the Spanish translation is a source of important transcultural information. Specifically, the terms heshang, seng, long, and san'e can be grouped together as words that designate living entities at different levels: monks, dragons, and reincarnation. These terms reveal transcultural, ideological, and conceptual issues, and situate Cobo ideologically on a par with other Spanish missionaries. There are also instances of polysemy, such as the term heshang or seng for Buddhist monks and Catholic priests; there are inconsistencies in the phonetic transcription, such as the use of lion, lon, cau, and lion for ‘dragon’. Ultimately, there is a noticeable unwillingness on Cobo's part to make comparative explanations, for example, in avoiding drawing comparisons between the dragon in Chinese culture and that in European culture. The motivation behind this could be a combination of ideological discordance, linguistic misunderstanding, purposeful or accidental cultural ignorance, and a keen awareness and desire to please the ultimate audience for his writings—the Crown. On that note, a complete analysis of all of Cobo's comments deserves a study in its own right, and this will be our focus in our future research.

Conflicts of interest

None.