I finished up my loaf of bread at a space of three days, that is to say on Sunday so I had to wait till the next Saturday for new one. I was terribly hungry…. I was lying on Monday morning quite dejectedly in my bed and there was the half of a loaf of bread of my darling sister…. I could not resist the temptation and ate it up totally—which at present is a terrible crime—I was overcome by terrible remorse of conscience and by a still greater care for what my little one would eat for the next five days. I felt a miserably helpless criminal…. I suffer terribly by feigning that I don’t know where the bread has gone and I have to tell people that it was stolen by a supposed reckless and pitiless thief and, for keeping up appearance, I have to utter curses and condemnations on the imaginary thief: “I would hang him with my own hands had I come across him.”1

This quote is an excerpt from a diary kept by an anonymous boy in the Łódź ghetto. We do not know his ultimate fate, but we can certainly speculate: The diary ends three months later, on August 3, 1944, during the final deportations from the Łódź ghetto. Written into the margins of a French novel, François Coppée’s Les Vrais Riches (The Truly Rich), the diary records the boy’s struggle with starvation. The quote tells of an unfortunately common occurrence – the boy’s hunger thwarted his attempt to carefully ration his bread and drove him to finish his ten-day allotment in three days. During the early ghetto period, the same amount of bread was distributed for a five-day allotment, but over the course of the ghetto’s existence, its inhabitants were forced to stretch their rations further and further. Consumed by an extreme hunger that drove him to eat his bread too quickly, the boy stole and ate his sister’s bread ration. Now, neither brother nor sister had adequate food for the next five days. The sister, who tried faithfully to ration her bread, lost her supply entirely and had to suffer hunger without even that sparse amount. Despite caring about his sister, the boy resorted to a desperate survival strategy: theft. Hunger drove him to survive by any means necessary, even if it meant endangering his sister and breaking the family trust.

For the Jews incarcerated in Nazi ghettos, the lack of food subsumed all aspects of existence and transformed ghetto life and ghetto society. Hunger caused social breakdown as people tried to nourish themselves sufficiently. The Łódź, Warsaw, and Kraków ghetto populations suffered from a lack of food as a result of German racial policy, which designated Jews as “useless eaters,” undeserving of adequate food. As starvation and hunger-related diseases decimated Jewish ghetto populations across Nazi-occupied Poland, access to food became a key factor in survival. Jews had no control over Nazi race – influenced food policy, which denied sufficient food to populations throughout the Nazi occupation.2 But they could – and did – attempt to survive the deadly conditions of Nazi ghettoization through a range of coping mechanisms and survival strategies.3 This book tells their story.

Factors of Survival

The question of what factors contributed to survival during the Holocaust is a significant victim-centered question of Holocaust historiography.4 Although survival is unrepresentative of Holocaust victim experience as most Jews under Nazi occupation did not survive.5 Examining the factors that led to survival allows scholars to reveal the everyday lives of Jews during the Holocaust including victims who perished and the exceptions, those who survived. This book, an Alltagsgeschichte, or history of everyday life, focuses on one key aspect of survival – access to food – and uses this lens to explore the daily experiences and struggles of the Jews in the ghetto as they encountered food and hunger.6 The examination of internal life in Holocaust-era ghettos with questions centered on victim experience continues a tradition established by some of the earliest Holocaust scholars, many of whom were survivor historians, who sought to follow a prewar practice of examining Jewish life and history.7 Their works recorded the experiences of Jews during the war, resistance in the ghettos (spiritual, cultural, and physical), and leadership and internal governance of the ghettos.8 While these works continued to be undertaken, they were eclipsed by a shift in the field of Holocaust studies, driven by scholars primarily from Europe and North America, which emphasized the motivations and actions of perpetrators. Although historians of the Holocaust were influenced by calls for history from below, they remained focused on perpetrators and their motivations; only shifting their attention from structures of power to ordinary Germans, not to the victims of the regime. It is only in recent years that historical questions that center on victims as a historical subject were no longer eclipsed by works that concentrated on perpetrator actions and motivations. This book focuses not on the ghetto’s function within the Nazi bureaucracy and genocidal plans, rather it examines Jewish life inside ghettos to present a complex picture of varying Jewish experiences with an emphasis on victim agency.9

By examining the socioeconomic and geographic factors that enabled individuals, households, and communities to obtain food in the ghetto, one is able to see how these factors affected or facilitated overall survival during the Holocaust. On the individual and household level, prewar socioeconomic position often played an important role in food access, although one’s condition rarely remained static during the war period. Not only social standing, actual resources, and social network played a role in one’s standing; intersecting factors such as gender and religion affected food access. At the communal level, there were different means of accessing food and coping with its absence. These included food distribution strategies, trading of assets, repurposing of food waste, and other means. Many factors including the location of a city within the overlaid German administrative apparatus, the city’s prewar economic position, and local resources also played a role in food access.

The Atrocity of Hunger

In a world in which we have the technological ability to transport food to anywhere that needs it, modern famines are always human engineered. That is to say, there is always the option to provide food to an area unless someone actively blocks food from reaching individuals. The ghettos in Łódź, Warsaw, and Kraków, to varying degrees, served as impediments to the free movement of food. In addition to the physical barriers created by the ghettos, limitations were deliberately placed on Jews’ access to food. Non-German civilian populations, particularly Jews, were entitled to less food than Germans within the German food access hierarchy. This racial worldview vis-à-vis food access ultimately allowed the Germans to deny populations throughout Nazi-occupied Europe sufficient food for survival.10 Like many other groups subjected to famine conditions during the course of the modern period, the Jews of the ghetto turned to coping mechanisms commonly used in food crisis situations. Famine studies offer theoretical frameworks for analyzing and understanding the mass starvation of the Jews of the ghettos.

The concept that starvation in the modern world is intentional comes from famine theorists. Amartya Sen, the Nobel prize – winning economist behind the economic theory of entitlements, dispelled the notion that famines were caused by crop failures or other natural disasters.11 Famine scholars Jenny Edkins and Alex de Waal have further argued that famine in the modern era must be understood within the context of violence and mass atrocity.12 Starting in roughly the early 2000s, we see the development of scholarship on genocidal famine or “genocide by attrition.”13

Many historians examining famine during World War II focus on causes of starvation, particularly as it relates to Nazi policy.14 Although this book takes a historical approach, unlike other works that have dealt with hunger in ghettos or during the Holocaust, it does not focus on the reasons for Nazi hunger policy or on perpetrator motivations. Rather, it examines the impact of that starvation on the Jews in the ghetto within the context of genocide, with a recognition that hunger in the ghettos must be framed within the context of genocide and the intentionality of contemporary famine.

This work examines a society in extremis, one suffering from what I term the atrocity of hunger. Although famine situations can result in high mortality, this is not the only impact of mass hunger.15 The atrocity of hunger results from the intentional starvation of a group through the denial of access to food, and it includes more than just the embodied experience of starvation: The physical and mental suffering that humans undergo due to the physiological effects of starvation, as well as the transformation and breakdown of families, communities, and individuals whose lives and core beliefs are shaped by starvation. It is also the process experienced by individuals, households, and communities as they move from food insecurity to a state of starvation. The atrocity of hunger takes place during genocidal famine.

This book provides important insight into the individual, familial, and internal societal transformations that take place during a famine, particularly a genocidal famine. As Peter Walker notes, “there are few descriptions of famine or writings about famine by its victims. It is the most vulnerable and least powerful who suffer: a group which has little access to the written word and its dissemination.”16 In the case of the Łódź, Warsaw, and Kraków ghettos, however, the Jewish residents left behind a plethora of records both during and after the events, allowing us to view a community and its transformation during a period of mass starvation.

The famine in the ghettos offers a few unique aspects for the study that distinguish amongst those famine genocides in which we see the atrocity of hunger. One is the long duration of forced famine conditions. Many famines come in waves or last for a shorter period of time, during which the most vulnerable die and the least vulnerable employ coping mechanisms until recovery is possible. However, in the ghettos, there was no recovery period. In the Nazi ghettos under consideration, a cascade effect was in place: As the marginal groups were decimated, individuals and families from other social strata became vulnerable and descended to the point of being unable to obtain adequate food resources. The forced starvation continued for years, and those who did not perish from the hunger and associated hunger diseases were largely killed by other violent means.

Another significant difference between this famine and others that have been studied in the contemporary era is the demographic makeup of those in the ghettos. Many studies of hunger during war focus on home fronts, which are largely absent of men of military age, their populations composed mostly of women and girls, along with a smaller male segment of young boys and elderly men. The hunger situation on the home front, then, gets painted as a feminine issue or associated with women.17 This was true, for example, in World War II – era Leningrad, where men were more absent due to their service as soldiers.18 Women were then associated with numerous coping mechanisms. This feminization of famine situations is not limited to urban contexts. In many agrarian famines, men leave the area in search of work as a coping mechanism, leaving women behind.19 In contrast, in the case of the ghettos, people of all ages including working-age men were present. Many tasks that are viewed as specifically feminine in famine scholarship were performed by men and women in the ghettos. This study, therefore, allows for a more nuanced view of gender and famine.

Inside a Famine: Coping Mechanisms

Famine scholars from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds have explored famines in which individuals and societies were transformed by the lack of food. Many of those who study famines do so to assist in identifying emerging famines before they become widely life threatening; their scholarly purpose is prevention, the development of a warning system based on identifiable stages. This book relies on a great deal of this prevention research to identify the common traits of famine including economic and political factors as well as familial and societal transformations.20 What many scholars view as stages or attributes of famine, however, this book recognizes as human coping methods deployed to combat hunger.

The ghetto inhabitants attempted to address starvation at the communal level, household level, and individual level through a variety of coping mechanisms. Techniques for survival in famines include asset liquidation, innovative deployment of labor, reliance on social networks, the consumption of less preferred or less nutritional foods, the sacrifice of some individuals for the benefit of other individuals, and illicit acquisition of food.21 The communities, families, and individuals of the ghettos employed all of these methods.

Entitlement theory, Sen’s food-access theory, posits that individuals obtain food by trading bundles of valuables for it. Those bundles can consist of labor or goods.22 Jews in the ghetto were able to obtain food by trading their labor or their valuables for food. But the ghetto conditions affected Jewish food access beyond simple economics, as scholarly interventions pointing to forced starvation as a form of violence help us understand.23 Due to the ghetto’s walls, the ability of Jews to purchase food was not based on an open economy. Jewish purchasing power was diminished in a number of ways. Prices were higher for them due to the artificial limits placed on the food available to them. The Germans made forced labor of the Jews compulsory and often mandated them to work without compensation or at very low levels of compensation, thus artificially diminishing the value of their labor. Further, the German seizure of Jewish assets and the trade of assets on the black market devalued the buying power of Jewish property.

Despite this devaluation of Jewish labor and goods, families and individuals in the ghettos sold or traded items of value to buy resources for survival, a pattern of behavior that is consistent with other famines. More notable is that the ghettos provide an example of a community attempting to trade assets and labor for food in a famine situation. At the community level, Judenräte (Nazi-mandated Jewish Councils) sought to sell off community assets or gain access to communal bank accounts to pay for basic needs. Similarly, Jewish communal leadership, adhering to Nazi demands, provided labor for the Germans. In some cases, the labor was compensated with resources to help purchase food items for the ghetto. Jewish communities also employed individuals in the creation of foodstuffs for ghetto residents. In many famine situations, individuals and households put all available household members to work to acquire food. In the ghettos this pursuit took the form of working a job, standing in food lines, begging, searching through garbage, digging for food, or other targeted activities. Writing about the Blockade in Leningrad, Jeffrey Hass has given the gender-neutral term “bread seekers” to the individuals who undertake these tasks, but he identifies them as predominantly women.24 In the ghettos, in contrast, men, women, and children were all seekers of scarce resources or “bread seekers.” At the individual and household level, people reached out to their extended family and friend networks for meals, job opportunities, or funds to purchase food, and food was stretched as the definition of what counted as food broadened. Even so, individual families had to make difficult choices about food distribution to their members. At the communal level, social networks, including for instance, the American Joint Distribution Committee, were leveraged to supplement food supply for the ghettos, and types of foods that were not typically eaten before the war were processed for distribution to the community at large. This was similar to communal coping methods employed in the siege of Leningrad, where “the city’s food industry implemented the use of surrogates in the production of bread, meat, milk, confections, and canning products.”25 At all levels, Jewish individuals were allotted less food than Germans, Poles, or other groups in occupied Poland, which resulted in fatal starvation or deportation for some members. Both communal leadership and individuals employed a range of strategies to acquire food illicitly. Criminal behavior such as theft became common and even at times a requirement to survive. It is not a simple situation, however, as many individuals in famine situations become “both the victims and perpetrators of food theft.”26 This complexity highlights one of the other aspects of the atrocity of hunger: the challenge that hunger and starvation pose to core values.

Divergent Paths: Kraków, Warsaw, and Łódź

This book argues that the individual communities in which Jews were ghettoized – including the wartime Nazi administrative districts in which cities fell as well as prewar communal attributes – affected food access and survival. Ghettos were residential areas, often with some sort of enclosure and restricted entry, set up by the Nazi regime in occupied Poland to segregate Jews from the non-Jewish population. Recent scholarship on ghettos has documented multiple types of ghettos with varying degrees of openness; the level of openness of World War II – era ghettos also shaped food access.27 To demonstrate this, this book compares the ghettos in three major cities: Kraków, Warsaw, and Łódź. While these three cities share the attributes of all being major Polish cities with large Jewish populations, they diverge in a number of ways, including crossing between two wartime Nazi administrative districts, level of openness, prewar economic structures and political leanings, and provide the opportunity to look at both large ghettos as well as a smaller ghetto (though still large enough to have its own internal food distribution system).

The Łódź ghetto, located in the Warthegau region, was the most sealed of the three ghettos under consideration, with the most limited food resources outside those allocated by the Germans. The Warsaw ghetto, located in the General Government (Generalgouvernement), was considered a sealed ghetto, but a significant number of individuals were permitted to pass in and out of the ghetto on a daily basis, creating opportunities for food and additional people to pass through. The Kraków ghetto was the most open of the three ghettos, remaining relatively open to Jews passing between the ghetto and the city, either individually or in groups, until almost the end of the ghetto’s existence. As a result, this ghetto experienced the least starvation.

In addition to their differing degrees of openness, communal differences were apparent in the Jewish leadership of the three ghettos. During World War II, the Germans established the Judenrat, an official Jewish communal leadership that became responsible for many aspects of local governance once the Jewish community was confined to ghettos. Different communal Judenräte, influenced by the prewar character and political leanings of the kehillah (Jewish community), adopted varying methods of internal ghetto food distribution to combat hunger inside the ghettos. The Jewish communal leadership, for at least a portion of the ghetto period, controlled certain aspects of the distribution of the food Nazis allocated to the ghetto.

Before the war, the Jewish populations of Łódź, Warsaw, and Kraków differed in political orientation, economic resources, and acculturation. Their diverse political inclinations manifested themselves in the different methods employed by the Judenräte in these cities to address the poverty of the Jewish populations that came under their purview. Łódź, a socialist-leaning city with many Yiddish speakers, contained a large poor and working-class population. In Łódź, the ghetto leader Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, although not a socialist before the war, attempted to feed the population as a whole from collective community resources. He tended to battle attempts to create free markets in the ghetto. By contrast, Kraków’s acculturated and cosmopolitan if also traditionally inclined Jewish population functioned largely on a capitalist model, whereby individuals supported their own families and charitable giving was the major vehicle to support the vulnerable. Meanwhile, Warsaw’s prewar Jewish population embodied a tension between an array of socialist-leaning organizations and a middle class with conservative leanings. There, the official Judenrat leadership leaned toward capitalist models to support the population, with charitable giving and some welfare-state features. Various organizations attempted to meet the needs of the impoverished. The way that prewar political leanings were reflected and perpetuated in Jewish communal responses to food scarcity significantly affected food access in individual ghettos.

This book gives an extensive history of the ghettos of Kraków, Łódź, and Warsaw, but it is not meant to be exhaustive. Many works have provided both detail and overview of the history and internal bureaucratic structures of Łódź and Warsaw.28 The material presented here aims to provide salient context for the arguments raised by this book. For example, the Warsaw ghetto uprising was a significant event in the life of the ghetto but does not feature prominently in this work, and the resistance efforts of the Kraków ghetto fighters outside the ghetto are not featured at all. These were exceptional events, whereas I am interested in the everyday albeit during an extraordinary period. The Warsaw ghetto uprising, then, is only discussed in the context of hoarding and food shortages during the turmoil. The book goes further in its presentation of new material on the Kraków ghetto, including on its Judenrat and internal structure during the ghetto period. That is because for the Kraków ghetto, unlike the other two discussed here, its definitive history has not yet been written.29

At the outbreak of World War II, Poland, with 3.3 million Jews, was home to the largest Jewish population in Europe. The three cities under consideration in this volume were all major population centers in the Polish state that was created in the aftermath of World War I; thus, the Jews in these cities found themselves newly enfranchised as citizens of Poland. The three cities were affected by the Great Depression and were likewise affected by a turning point in the Polish treatment of Jews, when Polish leader Józef Piłsudski died on May 12, 1935. After this point, numerous pieces of discriminatory legislation were passed against the Jews of Poland, and violence against Jews in Poland increased. Despite their similarities as Polish cities, these three cities had divergent paths of historical development, which resulted in linguistically and socioeconomically distinct Jewish populations and affected their fates during the war.

Kraków

Kraków served as the historical capital of Poland until the end of the sixteenth century, after which it remained an important cultural capital. It had been under Austrian rule before the First World War and had a significant number of highly assimilated Jews in its populace. After World War I, Kraków was incorporated into the newly constituted Second Polish Republic. At that time, approximately 25 percent of Kraków’s population were Jews.30 By 1931, Kraków’s Jewish population had risen to 56,515 out of a total Polish population of just over 250,000.31 Kraków was the fifth-largest city in interwar Poland, with a large, diverse Jewish population that comprised Orthodox Jews, Hasidic Jews, Progressive (Reform) Jews, assimilated Jews, and Jews of various political leanings, including Zionists, Bundists, socialists, and other political groups. The Jews of Kraków were more acculturated than those of Łódź or Warsaw, with a large portion of the population speaking Polish as their native language.

In the interwar period, the Kraków Jewish communal organization, or kehillah, was led by the progressive assimilationist Rafal Landau. The progressive assimilationists led the kehillah in partnership with the Orthodox Jews. This coalition was important for maintaining control of the board because, by 1929, Zionists had begun to make some headway, gaining nine out of the twenty-five seats on the kehillah’s governing board.32 In 1938, the Jewish community was forced to contend with a sudden influx of Polish-born Jews who had been residing in Germany but were forced over the Polish border by the Nazi regime. When many of the refugees were resettled in Kraków, the Jewish community collected clothes and money for them.33 The kehillah also set up facilities to feed the refugees, including community kitchens at Skawińska Street 2, Józefińska Street 3, Dajwór Street 3, Estera, and Miodowa Streets. There were also places for refugees to live situated on Skawińska Street 10, at the school on Podbrzezie Street, at the synagogue Znekro in Podgórze, at Thilim on Bożego Ciałastr Street, on Bocheńska Street, and on Agnieszki Street. Additional refugees were lodged in private apartments by the Jewish Housing Department.34 Holocaust survivor Ben Friedman recounted his family taking in a couple of the Jewish refugees expelled by the Germans, even though they were a family of four with only two bedrooms.35

This influx of refugees accounts for some uncertainty about the number of Jews living in Kraków on the eve of the Second World War. Various figures are given, ranging from a little under 65,000 to approximately 68,000.36 The very large number of German Jewish refugees, including their precarious situation, would play a role during the German occupation.

Warsaw

Warsaw, the capital of Poland since the end of the sixteenth century, was the most populous city in Poland and had the largest Jewish population in Europe. It, along with Łódź, had been under Russian control prior to the First World War and had both a large upper- and middle-class Jewish population along with working-class and poor Jews.

During the latter part of the nineteenth century and through the early twentieth century, the Jewish population of Warsaw grew considerably, both in number and as a percentage of the total population. The tremendous growth was in part a result of Jews fleeing Russian pogroms at the end of the nineteenth century.37 This period coincided with the growth of Jewish institutions and places of worship. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Jews accounted for 35.8 percent of the population of Warsaw. There were a diversity of Jews in the city: secular Jews, who aligned with a variety of politically leftist organizations, ranging from communist to Bundist, and religious Jews, who banded together politically under the organization Agudat Israel, a political party that staunchly protected Orthodox Judaism.

By World War I, the number of Jews in Warsaw had grown to 337,000 people, accounting for 38 percent of the city’s population.38 During the war, the Jewish population of Warsaw swelled significantly due to refugees coming in from the provinces. This number declined after the war, as people returned to their homes.39

After the First World War, Warsaw became the capital of the newly created state of Poland. The new state provided Jews with full civic rights. The last census conducted before the outbreak of World War II was in 1931, and Warsaw at that time had a Jewish population of 352,000, or 30.1 percent of the overall population of 1,171,898.40 The Municipal Board of Warsaw estimated that in August 1939, there were 380,567 Jews, making up 29.1 percent of the population of Warsaw.

Łódź

Łódź, a highly multiethnic city with significant Jewish, German, and Polish populations, was a center for industrial textile production and had a large labor movement. It had a small upper-class Jewish population and a large number of Jewish working poor.

Like all Polish lands, Łódź came under a number of rulers as a result of the partitions of Poland. It was under Russian rule that Łódź developed from a village to a city, the growth spurt commencing when it was designated in 1820 as an industrial center. The transformation of the city initiated by its turn toward manufacture included a vast population increase, rapid urbanization, territorial expansion, and industrialization.41 As the city expanded, so did the Jewish population. By 1897, there were 98,677 Jews in Łódź.42

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, there was tremendous political unrest in the Russian Empire. The tsarist government stirred up anti-Jewish sentiment and allowed violent outbursts against the Jews of the Russian Empire as a means of distracting from agitation for political change. These pogroms against the Jews resulted in mass death and destruction. This same period of repression saw the emergence of important Jewish political organizations in Łódź. In the face of political inequality and physical persecution, Jewish political organizations – which were illegal, like all political organizations at that time in tsarist Russia – sought remedies for the political inequalities of the Russian Empire. Jewish socialism, which sought a broad change to create a more equal society, had its largest manifestation in the form of the Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia, otherwise known as the “Bund.” The Bund was the largest and most powerful Jewish labor organization in Poland. It called for a culturally autonomous Jewish people living in a socialist state. The Bundist movement in Łódź started quite early, in 1897, with agitation beginning among Jewish weavers, but attempts to organize workers met with police resistance, and so the early efforts were primarily limited to the distribution of illegal literature.43 By the beginning of the twentieth century, however, the Bund was successfully organizing workers for protests. Jewish workers were at the forefront of strikes and other activities in Łódź, and they played an active role in the 1905 Russian Revolution.

The strong Jewish presence in labor movements reflected the reality that most Jews were engaged in wage labor; in Łódź, this meant employment in the textile industry. The majority of Jewish labor in the industry was skilled, and heavily concentrated in small companies or private, home-housed textile workshops. On the eve of World War II, approximately 70 percent of the Jews of Łódź lived in poverty, with over 40 percent reliant on welfare. They were particularly vulnerable to economic downturns like the Great Depression. This is evidenced by the fact that in 1937, 41 percent of Łódź Jews applied for relief, consisting of matzah and clothing during Passover.44

By the beginning of the twentieth century, other Jewish political organizations began to emerge, with many socialist-leaning Jewish organizations as well as Zionist, assimilationist, and religious parties. There was tremendous division and tension among the various Jewish political groups in Łódź. In the early interwar period, Zionists and religious parties were strong, but toward the end of the interwar period, socialist parties rose appreciably in voter popularity. As an industrial center, Łódź had an active worker and leftist political apparatus. The Łódź Jewish community was considered to be a socialist and Bundist stronghold just before the beginning of the war.45

With close to a quarter-million Jews before the German invasion, Łódź had the second-largest Jewish population in Poland and Europe (with Warsaw having the largest).46 In 1931, Łódź Jewry had totaled 202,497 persons, 96,658 or 47.7 percent of whom were male, and 105,839, or 52.3 percent, of whom were female. In 1939, the Jewish community of Łódź was estimated at 222,000, making it approximately 34.5 percent of the total population of 665,000.47

Members of the Łódź Jewish community were mostly religiously observant and lived more separately from their Christian neighbors than did Jews in more cosmopolitan places like Warsaw and Kraków. As a result of the Nazi invasion, these economically, linguistically, politically, socially, and even religiously diverse Jews were wrenched from their varied places in Łódź society and thrown together within the confines of the Łódź ghetto. The diversity of identities of these individuals, all thrown together into a common space, played a role in how this mixed group coped with their common fate.

Sources

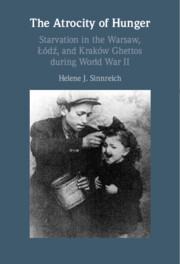

The sources for this book encompass documents, materials, and testimonies produced by German government offices, individual Germans, members of the official Jewish leadership, non-Jewish Poles, and individual Jews. Some materials were created by people while the ghetto was in existence, while others were created at various stages, ranging from immediately after the ghetto experience to decades after the war. The documents and artifacts consulted include government documents, Jewish communal leadership documentation, legal and illegal newspapers, and artistic creations made in official, semi-official, personal, and illicit capacities: photographs, picture albums, songs, and drawings. Among the photographs examined as sources for this book were those created by perpetrators. I struggled with whether to include these, particularly images taken to emphasize the inferiority of the Jewish subjects, but I ultimately decided to reproduce some of these photographs that told an important story.48

Maps, buildings, and objects were also examined, as were personal sources such as oral testimonies, memoirs, diaries, and poems. I have applied a variety of critical lenses to these source materials. Some of these techniques come from Holocaust studies, encompassing, for example, the examination of Holocaust testimonies, while other techniques come from fields that examine people who, due to powerlessness, illiteracy, or the destruction of archival materials, need to be observed through unconventional or atypical methods.49

While I utilize source material from a wide range of viewpoints, I have not privileged perpetrator sources in the construction of this book. The story I wish to emphasize is that of Jewish victims’ survival strategies. This monograph privileges those perspectives because by focusing on them, we can reinscribe Jewish ways of knowing as essential to understanding ghettos.

One difficulty in researching ghettos, however, is that much of our source material on them comes from elite sources: those in charge, those in high-ranking positions, and those fortunate enough to survive and relay their stories. We have some diaries and records from the poor who died off early from starvation, but in many cases, we rely on more elite voices to bring us the story of the ghettos’ poorest. Another difficulty is that the three ghettos studied vary in surviving material. Łódź was the most-documented ghetto. Thousands of pages of documents survived, including diaries, official Judenrat documentation, German materials, and postwar testimonies by a large group of survivors. Warsaw similarly had a large group of survivors as well as surviving documentation, most notably the Ringelblum Archive, a collection of diaries, writings, and other materials saved from the ghetto’s destruction by a group of journalists, historians, and other activists. By contrast, only scant documentation survived the Kraków ghetto. There are few wartime diaries, only a small amount of official ghetto documentation, and very little German documentation from those with direct oversight of the ghetto. That said, we have material that predates the closing of the ghetto such as the registration forms of those applying successfully and unsuccessfully to gain admittance to the Kraków ghetto as well as the oral and written postwar testimonies of Kraków ghetto survivors.

The sources for this book came from the archives at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMMA), Yad Vashem in Israel, Bundesarchiv in Germany, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, Archiwum Panstwowe w Łódźi (Łódź State Archive), Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (Jewish Historical Institute, ŻIH) in Warsaw, Beit Lohamei Ha-Getaot (Ghetto Fighters House Archive) in Israel, and Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive at the University of Southern California.

Organization of Book and Summary of Chapters

This book is organized to open with the start of the war and set the stage of hunger in the ghettos by examining the Jewish experience with hunger and violence before ghettoization. It closes with the end of the ghettos and the deportations out of the ghetto but also examines how deportations impacted food access. Between these chapters are three sections. The first portion consisting of Chapters 2 and 3 examines communal food access. The next section, Chapters 4, 5, and 6, explores the crux of the atrocity of hunger – physical and social breakdown. It explores the impact of hunger on the vast majority of the ghetto populations with discussion of how differing positionality mitigates or increases the impact of hunger. The last section of the book, Chapters 7, 8, and 9, explores mechanisms through which food entitlement could be augmented. The book traces hunger encountered by the Jewish population of the three ghettos from the beginning of the war to their departure from the ghettos and how they sought to cope at the individual, household, and communal levels.

Chapter 1 begins with the German invasion into the three cities and examines how early violence perpetrated against the Jewish populations, mass migrations during the early war period, and the forced pauperization of numerous Jews affected their ability to protect themselves against hunger. It depicts the hunger experienced by many before the creation of the ghettos and highlights how geographic location before and during the ghetto period affected food access.

Chapter 2 examines the Jewish leaders in each ghetto who were responsible for communal decisions about food distribution. It examines the flight of much of the prewar leadership and the violence experienced by the Jewish leadership that remained. It also outlines the physical location and attributes of each of the ghettos, the creation of each ghetto, and the ways ghettoization restricted Jewish life.

The supply and distribution of food to the three ghettos is addressed in Chapter 3. It looks at how the individual ghettos, based on their prewar attributes, changing German policies, and worsening situations, distributed food to residents. The chapter also examines communal strategies for increasing food supply through agricultural enterprises, and the processing of food waste and low-quality food into edible food.

Chapter 4 examines hunger’s impact on the physical body, on the mental state of its victims, and on social dynamics, as well as death, the final result of starvation. It explores ways in which the Jews of the ghetto experienced and coped with these physical and physiological transformations.

Chapter 5 examines the everydayness of hunger in the ghetto including individual and household coping strategies. It looks at the leveraging of relationships for food access, as well as the ways in which individuals and households traded assets for food including foods that were not typically consumed prior to the war.

Chapter 6 explores how socioeconomic status mediated by gender and religion played a role in food access. Those who were poor before the war were most vulnerable to starvation in the early period of the ghetto. These individuals were criminalized and then subjected to the earliest deportations to forced labor and extermination camps. In turn, those who had been food secure during the early period of the war or ghetto were impoverished over the course of the ghettos’ existence and ultimately, in many cases, joined the ranks of the poor. Only the ghetto elites, who dined in fine restaurants and had access to sufficient and even luxury food items, were spared extreme deprivations.

Chapter 7 looks at charity and social help in the ghettos. It examines ways in which organizations, the Judenrat, and individuals distributed and were recipients of charity. This chapter explores the strategies of some ghettos in creating welfare structures such as free or low-cost ration cards as well as others where charity was predominately done through private initiatives, ranging from private organizations establishing soup kitchens to individuals giving to beggars. Most tragically, it examines the plight of those in communal care including refugees.

Chapter 8 examines how individuals resorted to illicit means to obtain more food. Smuggling, theft, and black marketeering all supplemented the foodstuffs of Jews in the three ghettos. This chapter also looks at how war and ghetto events affected black market prices and how illicit activities shaped family relations.

Chapter 9 looks at work strategies for acquiring food. It examines how individuals strategically sought employment to meet their needs, how the Judenrat struggled to provide the labor demanded by the Germans and feed the ghetto inhabitants, and how the Germans ultimately took control of food out of the hands of the communal leadership in order to prioritize labor.

The last chapter examines deportations into and out of the ghetto. It explores how the arrival of deportees affected ghetto food supplies, how being a displaced deportee shaped individuals’ ability to obtain resources in the ghetto, and what experiences were unique to Jews from Western Europe in the Polish ghettos. It also considers the deportation of Jews out of the ghettos and the use of food to lure hungry Jews to deportation as well as the chapter in which the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and food issues related to it are discussed.