There is an increasing need for palliative care in Canada as our health care system responds to an aging and clinically complex population. As a result, there are a growing number of older Canadians entering long-term care (LTC) homes (Statistics Canada, 2016). LTC homes provide a range of services including nursing care and assistance with activities of daily living to the adults residing in them (Service Ontario, 2017).

As per the 2011 Canadian census, 4.5 per cent of the population over the age of 65 years was living in an LTC home (Statistics Canada, 2015). Many residents will live out their last days of life in LTC homes. Therefore, there is a need to ensure that these facilities have the capability to deliver quality palliative care to residents.

The provision of palliative care in Canada is guided by policies that exist at varying levels of government and within organizations. These policies provide a framework and guidelines for the delivery of palliative care in clinical practice. However, inconsistencies among palliative care guidelines in high-level guiding documents could result in suboptimal patient care, as further inconsistencies could be created in lower level documents (Venturato, Kellett, & Windsor, Reference Venturato, Kellett and Windsor2007). Documents need to ensure consistency across levels to avoid discrepancies in care and to ensure that optimal palliative care is provided to individuals residing in LTC homes throughout Canada.

The national model for hospice palliative care proposed by the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA) (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013) can be used as a guide to evaluate both the holistic nature of documents and whether the CHPCA model domains are maintained throughout varying levels of documentation. In this model, the Square of Care is a conceptual framework proposed by the CHPCA (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013) to reinforce the process of patient and family care in several essential palliative care domains.

Little is known about the characteristics of current Canadian palliative care guiding documents and whether they support the holistic nature of palliative care. By examining the extent to which documents address palliative care domains and the type of content covered, through use of the CHPCA Square of Care model, key areas in need of further development can be identified and inconsistencies eliminated. This would help to guide future work when creating palliative care guiding documents. This would have the potential to improve palliative care for residents in LTC homes across Canada, as best practices are more likely to be clear and maintained throughout the varying levels of documentation (Venturato et al., Reference Venturato, Kellett and Windsor2007).

The purpose of this article is to provide an understanding of the current characteristics of Canadian national and provincial palliative care documents, address the provision of these documents in guiding palliative care in LTC homes, and evaluate if the domains of the conceptual Square of Care model are addressed and consistent throughout the varying levels of care guiding documentation.

Barriers to Delivering Palliative Care in LTC Settings

Literature suggests that there are several barriers that prevent LTC facilities from pursuing a palliative approach to care. For example, families of dying residents in LTC facilities have identified pain management and comfort care as the highest priority for care (Vohra, Brazil, Hanna, & Abelson, Reference Vohra, Brazil, Hanna and Abelson2004). However, many family and resident needs are not met because of a lack of training/education, poor communication among interdisciplinary team members, and inadequate assessments (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015; Huskamp, Kaufmann, & Stevenson, Reference Huskamp, Kaufmann and Stevenson2012). Lack of training, knowledge, and communication leads to poor pain and symptom management as well as late implementation of palliative care strategies (Huskamp et al., Reference Huskamp, Kaufmann and Stevenson2012).

Organizational factors within LTC facilities also have a significant and direct impact on the quality of care (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015). Factors including leadership, management, and the culture of the environment all contribute to the quality of care given to residents at the end of life (EOL) (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015). Practical barriers, such as a lack of time, funding, staff, and other resources also hinder the ability of LTC facilities to identify palliative care needs among residents early on (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015; Huskamp et al., Reference Huskamp, Kaufmann and Stevenson2012; Kayser-Jones, Schell, Lyons, Kris, Chan, & Beard, Reference Kayser-Jones, Schell, Lyons, Kris, Chan and Beard2003). Inadequate staffing and time constraints have led to poor advance care planning (ACP) among LTC residents (Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq, & Van Audenhove, Reference Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq and Van Audenhove2016, 2017; Huskamp et al., 2012). Literature suggests that health care professionals (HCP) engage in ACP discussions at the time of resident admission but fail to continue these conversations as the resident–care provider relationship progresses (Ampe et al., Reference Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq and Van Audenhove2016). In cases in which ACP is discussed, the emotional and psychological state of patients and families is often unacknowledged (Ampe et al., Reference Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq and Van Audenhove2016). A lack of clear guidelines and organizational policies, as well as the reluctance of HCPs to adhere to existing guidelines contribute to poor ACP engagement (Ampe et al., Reference Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq and Van Audenhove2016; Silvester et al., Reference Silvester, Fullam, Parslow, Lewis, Sjanta and Jackson2013). Adjusting these modifiable organizational factors through the introduction of new policies, committed to delivering a palliative approach, can have positive effects on symptom management in chronic illness and at the EOL (Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015). Therefore, it is evident that policies and procedures regarding ACP and other palliative care discussions need to be re-evaluated and standardized across sectors as well as strongly enforced by organizations to improve the quality of palliative care delivery.

Improving upon Palliative Care Delivery in LTC Homes

Problematic barriers influencing the provision of palliative care in LTC can be overcome through the implementation of a structured set of policies. For example, the implementation of a gold standard framework at local or provincial levels directing the provision of palliative care, especially in the LTC setting, can improve quality of life (Badger, Clifford, Hewison, & Thomas, Reference Badger, Clifford, Hewison and Thomas2009; Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015; Kinley, Froggatt, & Bennett, Reference Kinley, Froggatt and Bennett2013). A systematic review assessed the impact of implementing a gold standard framework and integrated care pathway for documents in LTC homes in the United Kingdom (Kinley et al., Reference Kinley, Froggatt and Bennett2013). These tools were meant to guide the provision of palliative care specifically in the LTC setting. The implementation of these tools resulted in positive outcomes for HCPs and residents (Kinley et al., Reference Kinley, Froggatt and Bennett2013). The tools helped identify resident needs, encouraged discussions regarding EOL preferences and supported a multidisciplinary approach. The implementation of such policies can also potentially increase the number of in-home deaths in LTC settings, facilitate the development of ACPs and decrease unnecessary hospital admissions or deaths (Badger et al., Reference Badger, Clifford, Hewison and Thomas2009; Finucane, Stevenson, Moyes, Oxenham, & Murray, Reference Finucane, Stevenson, Moyes, Oxenham and Murray2013; Miller, Lima, & Mor, Reference Miller, Lima and Mor2014; Miller, Tyler, & Shield, Reference Miller, Tyler and Shield2015). Furthermore, increasing the quality of care in LTC facilities is a more cost-effective strategy for the health care system (Holland, Evered, & Center, Reference Holland, Evered and Center2014; Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee End-of-Life Collaborative, 2014). Overall, it is evident that the integration and development of policies specific to the provision of palliative care in LTC facilities can lead to HCPs and teams being better trained in palliative care and enhance the quality of care provided in LTC homes (Kaasalainen et al., Reference Kaasalainen, Ploeg, McAiney, Schindel Martin, Donald and Martin-Misener2013; Radwany, Albanese, Hoiles, Hudak, & McGranahan, Reference Radwany, Albanese, Hoiles, Hudak and McGranahan2013).

Although there are many advantages to developing policies, guidelines and tools to address palliative care, these endeavors will be ineffective if the gap between policy and practice is not addressed (Venturato et al., Reference Venturato, Kellett and Windsor2007). Introducing new policies into practice, without consideration for the implementation process, resources, and training for staff can be met with resistance, rendering the effort unsuccessful (Venturato et al., Reference Venturato, Kellett and Windsor2007). Therefore, it is important to consider logistical factors and come to a consensus on a shared strategy for the improvement of palliative care. In recent years, new policies have been introduced in an attempt to improve and guide palliative care. However, the extent to which these policies are consistent across sectors and support one another in their vision and strategies for improving palliative care is unknown.

Methods

A document analysis was completed to describe current characteristics of national and provincial palliative care guiding documents and to gain an understanding of what domains of the Square of Care are addressed within current palliative care guiding documents pertaining to LTC. A document analysis involves completing a systematic process of retrieving and analysing documents (Bowen, Reference Bowen2009). Document analysis designs often utilize a content analysis methodology when analysing data. Therefore, this method of analysis was used in this study (Bowen, Reference Bowen2009; Elo & Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngas2007). Content analysis is a process of data analysis, which provides a description and quantification of the data collected (Elo & Kyngas, Reference Elo and Kyngas2007).

As part of a larger project, Strengthening a Palliative Approach in Long-Term Care (SPA-LTC), an analysis of documents pertaining to palliative care in LTC homes across five provinces in Canada (Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Quebec) and nationally was undertaken. These provinces were chosen based on their connections with the overall SPA-LTC project. Further to this, the study design and methodology for this document analysis was informed by one of the lead authors (L.V.), who has previously created a structured approach to identifying and examining varied levels of documents and policies (Venturato, Moyle, & Steel, Reference Venturato, Moyle and Steel2011).

Documentation Matrix and Analytical Framework

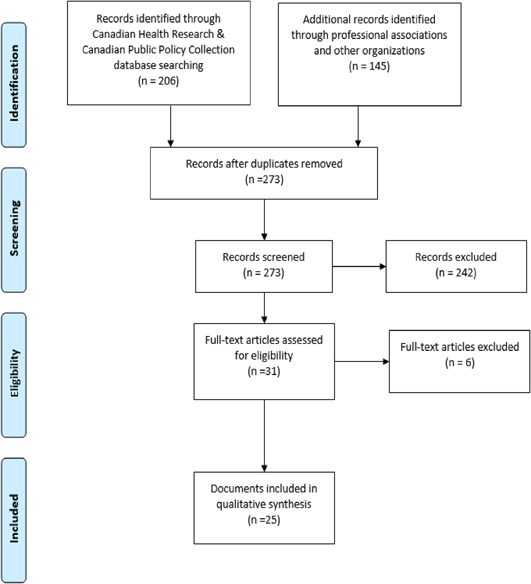

In this document analysis, high-level care guiding documents pertaining to palliative care were searched for utilizing the Documentation Matrix and Analytical Framework created by Venturato et al. (Reference Venturato, Moyle and Steel2011). This framework was modified for this document analysis and can be found in Figure 1. This study is particularly concerned with Level 1 Guiding Documents and therefore searches targeted policy documents and palliative care guiding documents. Legislative documents were not included in this document analysis, as this study focuses on policy and palliative care guidelines applicable to LTC, whereas legislative documents are focused on written laws created by the government (Government of Canada, 2006). Although legislation was not analysed, government associations were included in searches for policy and palliative care guiding documents in LTC.

Figure 1: Depiction of the documentation matrix and analytical framework that defined various documents and guided searches in across level document analysis (Venturato et al., Reference Venturato, Moyle and Steel2011)

Square of Care and Identified Palliative Topics

All documents were assessed based on their content/discussion related to eight Square of Care “common issue” domains (i.e., complications typically experienced by patients and caregivers) including disease management; physical, psychological, social, spiritual, practical, and EOL/death management; and loss/grief (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013). A summary of the definition of these common issue domains can be found in Table 1.

Table 1: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (2013) Square of Care Common Issue Domain definitions

Additional palliative care themes and topics emerged through researcher triangulation whereby three researchers completed a trial data extraction of an exemplary palliative care guiding document using Square of Care domains (Fraser, Reference Fraser2016). Emerging topics and themes agreed upon by the researchers were then included as categories on the data extraction template, supplementing the Square of Care domains. The topics that emerged from this process were assessed in the 25 documents identified in the literature search. These additional topics included policy and governance, quality management/accountability, rights/ethics (residents, families, staff), improving access and equity, developing caregiver supports, comprehensive palliative care program across sectors, and ACP. An “other” category was added to the additional palliative care topics to extract and describe content related to HCP education, policy issues, and EOL services, as these topics were addressed by multiple documents.

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

To obtain guiding documents, a systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of the McMaster University Health Sciences librarian. This strategy included searching two databases, the Canadian Health Research Collection and the Canadian Public Policy Collection. Following searches of these databases, further documents from palliative care associations, professional associations, and government organizations were accessed and screened. Professional associations pertained to social workers, registered nurses, physicians, and spiritual care practitioners. These were chosen as they are practitioners of regulated health professions most likely to be found in LTC. Searches were conducted using the same standardized search terms “palliative care”, “end of life”, and “long-term care”, and the same inclusion/exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria were developed by the research team and are listed here:

1. Created within the last 10 years (2007–17)

2. Palliative care focus

3. Applicable to LTC

4. High-level care guiding document

5. Canadian document

6. Applicable nationally or to one of the five included provinces

Documents published in the last 10 years were included because they were considered to be relevant, recent documents that were most likely to be currently in use. Documents were excluded if they did not meet inclusion criteria.

Professional associations, palliative associations, and government organizations were also contacted via e-mail to provide suggestions for possible high-level palliative care guiding documents. Those that were accessible via external Web sites and met the inclusion criteria were included. Palliative care experts were also approached for recommendations on high-level care guiding documents when documents could not be uncovered via the professional organization searches. Finally, associations and organizations for which documents were found that could not be accessed were e-mailed directly for assistance in accessing these identified documents.

Documents were initially collected and double-screened for inclusion criteria by two reviewers to ensure inter-rater reliability. A kappa calculated between the two reviewers based on the 206 documents demonstrated high consistency (κ = .869) in screening articles for inclusion. Reviewers then went on to screen additional documents independently. Any disagreements about documents to be included were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data Extraction and Directed-Content Analysis

Data were extracted and analysed from documents using a predetermined coding template for directed-content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). Three research team members (C. H, S. K., P. D.) collaborated to create the template using categories from the CHPCA Square of Care Model to Guide Palliative Care (2013) as codes. The “common issues” section of the Square of Care was focused on because it highlights experiences that are typically experienced by patients and their families. Researchers trialed the template by coding an exemplary palliative care document by Fraser (Reference Fraser2016) and added additional categories to fit the data (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). A pre-extraction phase was completed with two researchers coding the same 10 documents using the template to ensure agreement (κ = .872). Researchers then went on to code and extract data independently using the template. New codes were created to accommodate additional themes or categories as they emerged (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Patton, Reference Patton2015).

Documents were coded “present” or “not present” and quotes from the documents were extracted as proof of this. Results were analysed utilizing a content analysis approach in which code frequency is calculated and patterns or themes are explored across documents (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Patton, Reference Patton2015). Through researcher triangulation, team members further discussed and confirmed the emerging findings and their implications (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005; Patton, Reference Patton2015).

Results

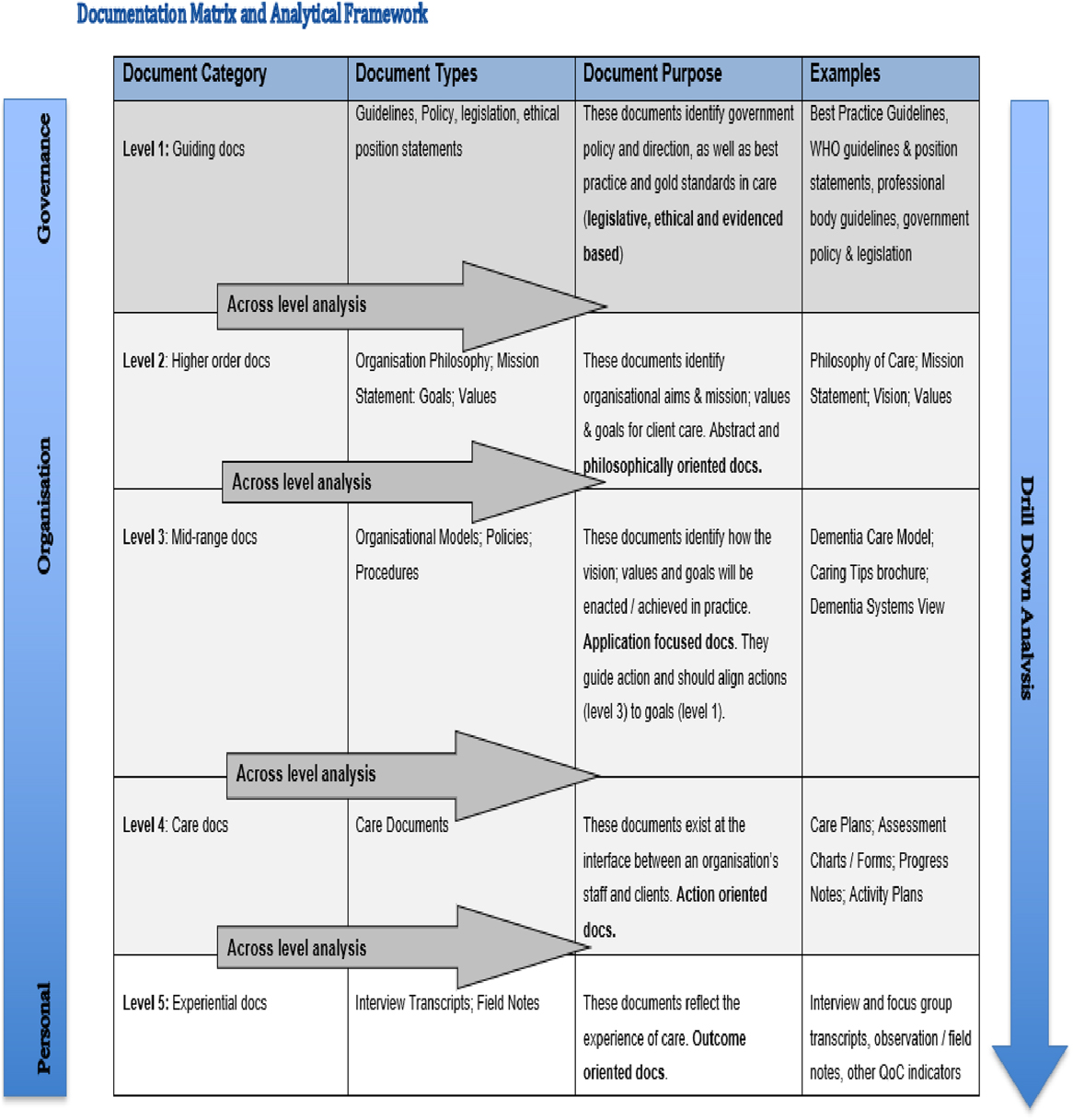

The literature search of the Canadian Health Research & Canadian Public Policy Collection databases resulted in 206 documents. Additionally, the literature search of the professional, palliative, and government organizations resulted in 145 documents. Following removal of duplicates, 273 records were initially screened for inclusion utilizing the identified inclusion criteria, and 33 documents were found to be eligible for inclusion. Documents were excluded when they did not fit inclusion criteria. A final total of 25 high-level palliative care guiding documents were included. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart can be found in Figure 2 (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Figure 2: PRISMA flow chart depicting systematic search and selected documents (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009)

Characteristics of Documents

The 25 documents have varying characteristics based on origin, reason for creation, and whether the developer was a provincial or national association. The characteristics of these documents are outlined in Table 2. Eight of the 25 documents were created by government organizations, whereas 9 of these documents were created by professional organizations. Seven documents were created by palliative care associations and one document was attributed to the “other” category; this document was created by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (2007) and focused on EOL care in Western Canada.

Table 2: Palliative care guiding documents characteristics

Note. Reasons for document creation exceed a summative total of 100 per cent, as some documents were created for multiple reasons.

Approximately half of the documents (n = 12) stem from national organizations. The remaining 13 documents were created provincially. Table 2 depicts descriptions of documents among the five provinces, with Ontario having the highest number of documents (n = 7). Fewer documents were found in Alberta (n = 3), Quebec (n = 2), and Manitoba (n = 1). No high-level palliative care guiding documents were found in Saskatchewan that fit the inclusion criteria for this study, despite the comprehensive search and outreach to associations/organizations within the province.

Reasons for document creation varied among three predefined categories stemming from literature, including the need to address clinical issues arising in care (n = 7), new evidence (n = 4) and “other” reasons (n = 19). During analysis, these “other” reasons emerged and were found to consist of palliative care policy/guideline development (n = 6) and health care system issues (n = 11). Two documents were categorized as “other” and were created for such reasons as needing a framework to outline the steps needed to reach a palliative care vision and for quality improvement through health care professional education (Canadian Medical Association, 2014; Quality Hospice Palliative Care Coalition of Ontario, 2011). Further to this, in some cases documents were created for more than one reason.

Clinical issues that stimulated the development of new guiding documents included, for example, patients’ and families’ delayed access to palliative care until late in the illness trajectory, ineffective pain management, and the need for palliative education for HCPs (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2010; Carstairs, Reference Carstairs2010; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Barnes, Horst and Sinclair2013). Documents were created in response to new evidence and trends surrounding hospital and pharmacy services during Canadians’ last year of life, place of death, and evolving best practice guidelines (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2007; Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee End-of-Life Collaborative, 2014; Registered Nurses Association of Ontario, 2011).

Table 3 depicts the number of documents addressing each Square of Care domain and the additional palliative care topics, as well as contrasting areas of focus among documents, based on their origin. Social issues were addressed in 19 (76%) of the documents, making this the most commonly discussed domain. The psychological and loss/grief domains closely followed and were touched on by 16 (64%) of the documents. The domains that were least addressed by these guiding documents were disease management and EOL/death management.

Table 3: Square of Care and additional palliative topics: Professional, palliative, and government documents n = 25

The additional palliative care topic of quality management and accountability was addressed most frequently in 21 (84%) documents. Examples of quality management and accountability topics are HCP knowledge and skills, setting provincial quality standards, and ensuring that quality palliative care is available to all Canadians (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2010; Carstairs, Reference Carstairs2010; Quality Hospice Palliative Care Coalition of Ontario, 2010). Supporting public education was the least frequently addressed additional palliative care topic with 10 (40%) documents touching on this topic. The ten documents that discussed supporting public education on palliative care proposed numerous strategies such as national public awareness campaigns and improving public awareness of ACP (Canadian Medical Association, 2014; Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care, 2011).

Table 3 also depicts differences in document content found among the three analysed categories of associations: (1) palliative, (2) professional, and (3) government. Although these organizations all have different purposes, they all develop documents to guide care. Examples of these associations include, respectively, the CHPCA, Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO), and Alberta Health Services. Overall, the palliative association documents addressed the additional palliative topics the most (75%), in comparison with the professional or government documents. Seven (100%) of the palliative association documents addressed the topics of quality management/accountability, improving access and equity, and comprehensive palliative care programs across sectors. Further to this, improving access and equity was also a focus in professional association documents, addressed by eight (88%) documents. Square of Care domains were addressed the least frequently (32%) by palliative associations, with disease management and EOL/death management only touched upon by one document each.

Professional associations focused on the Square of Care domains, addressing 63% of domains. In particular, eight (88%) of the professional association documents concentrated on social issues, and seven (77%) addressed the physical and psychological domains. Supporting public education and the practical domain were the least addressed topics by the professional associations. Overall, the government organizations’ focus appeared to be on the additional palliative topics, addressing 72% of these areas. In particular, government organizations addressed the social domain and quality management/accountability in all eight (100%) documents. The least addressed topic by government organizations was EOL/death management, with one document addressing this domain of the Square of Care.

Included Documents and LTC

All 25 documents were assessed as to whether LTC was addressed specifically, and with what frequency the term “long-term care” was mentioned. Table 4 provides a summary of the number of times LTC is mentioned in each document as well as the target audience, the purpose of the document, and, when substantive content was available, an example of the topics discussed related to LTC was provided. Twenty-three (92%) documents were found to mention LTC in the documents and the number of times LTC was mentioned varied significantly among documents. For example, five documents were found to only cite this term once (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013; Canadian Nurses Association, 2015; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Barnes, Horst and Sinclair2013; Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux, 2016; Ontario Medical Association, 2014). Four documents were found to cite LTC, 41, 45, 48, and 117 times (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association , 2014; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2007; Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care, 2011; Quality Hospice Palliative Care Coalition of Ontario, 2010). Although LTC was mentioned in most documents, its role in palliative care was discussed minimally. A typical citing is represented by the following quote. “At present, there is strong support for the development and implementation of an integrated palliative approach to care. Integration effectively occurs: throughout the disease trajectory; across care settings (primary care, acute care, long-term and complex continuing care, residential hospices, shelters, home); across professions/disciplines and specialties; between the health care system and communities; and with changing needs from primary palliative care through to specialist palliative care teams” (Canadian Medical Association, 2016, p. 4).

Table 4: Target audience, purpose, and number of times LTC was cited n = 25

Documents that cited LTC at a higher frequency (i.e., 41, 45, 48, and 117 times) discussed in more detail the role of palliative care in LTC (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2014; Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2007; Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care, 2011; Quality Hospice Palliative Care Coalition of Ontario, 2010). One of these higher frequency documents, known as the “The Way Forward” document, outlined several key aspects to improving palliative care in LTC homes specifically, such as building connections with palliative care programs and changing staffing ratios when an individual is at the EOL (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2014). Overall, very few documents specifically discussed in detail the role of palliative care in LTC.

Discussion

The purpose of this document analysis was to complete an across-level analysis of policy guiding documents pertaining to palliative care in LTC, nationally and across five provinces in Canada. In this analysis, documents were analysed for their characteristics, provision to guide palliative care in LTC, and ability to satisfy the “common issues” domains of the Square of Care, as well as commonly addressed palliative care topics (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013). Care guiding documents should be addressing the Square of Care domains, in particular, as these issues are typically experienced by residents and families. Furthermore, these documents aim to guide HCPs in providing high- quality care (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013).

Twenty-five documents that were palliative care guidelines and policy statements, from five provinces, were included in this review. This small number of guiding documents is of concern, as it indicates the lack of policy documents that exist across Canada on palliative care. Not only is there a low number of documents overall in Canada to guide palliative care in LTC, but this number also varies significantly depending on the province being analysed, as one province was found to have no guiding documents. This lack of policy documents in some provinces may be the result of there being fewer resources available. For example, some provinces appear to have fewer province-specific palliative associations when compared with Ontario (which had the highest number of documents provincially). Further to this, palliative care is a growing field in Canada that has often been set to the side in the health care system, which may be the cause of the lack of development of province-specific documentation (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Crooks, Whitfield, Kelley, Richards and DeMiglio2010). A final characteristic of these documents that stood out was the reason for the documents’ creation. Eleven (44%) of these 25 documents were created for the development of policies to address health care system issues. When guiding documents are created in response to issues, they are reactive and not proactive in guiding the development of palliative care in LTC. Although these documents appear to be created with a reactive intent, it is important that they are developed, as these health policies and guidelines are needed as a structure to accelerate palliative care development in Canada (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Crooks, Whitfield, Kelley, Richards and DeMiglio2010). The development of these few found documents to address these care issues is a step towards improving patient- and family-centred palliative care in Canada.

With regard to the Square of Care “common issues” domains, the documents were found to satisfy some aspects of these domains, but failed to address others. For example, the guiding documents addressed the social, physical, loss/grief, and psychological aspects of Square of Care in more than 50 per cent of all documents. However, disease management and EOL/death management were addressed the least. These findings are congruent with a similar study by Durepos et al. (Reference Durepos, Wickson-Griffiths, Hazzan, Kaasalainen, Vastis and Battistella2017) that explored the palliative content in dementia care guidelines utilizing the Square of Care model (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013). For example, Durepos et al. (Reference Durepos, Wickson-Griffiths, Hazzan, Kaasalainen, Vastis and Battistella2017) found that the physical, psychological, and social care domains of care were addressed often whereas EOL/death management and disease management were addressed the least (Durepos et al., Reference Durepos, Wickson-Griffiths, Hazzan, Kaasalainen, Vastis and Battistella2017). Where our findings contrast with those of Durepos et al. (Reference Durepos, Wickson-Griffiths, Hazzan, Kaasalainen, Vastis and Battistella2017) is in the loss/grief and disease management domains. Durepos et al. (Reference Durepos, Wickson-Griffiths, Hazzan, Kaasalainen, Vastis and Battistella2017) found that the least-cited domain in the analysed guidelines was loss/grief, whereas the maximum available content on disease management appeared there. It is possible that disease management was addressed least in the high-level documents analysed for our study because they aim for broad applicability to multiple disease states, in contrast to Durepos’ sample of documents, which focused entirely on dementia. Furthermore, it is possible that issues of disease management are more likely to be discussed in lower-level or organizational policies than in higher-level guiding documents.

Although the four domains of psychological, physical, social, and loss/grief were addressed more than 50 percent of the time in high-level care guiding documents, the four other common issue domains of spiritual, practical, EOL/death management, and disease management fell short. The Square of Care model is a nationally proposed strategy to address issues and provide high-quality palliative care (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013). Further to this, the Square of Care is built on national principles and practice standards, which should be addressed in order to ensure consistent and quality palliative care for residents (Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013). The lack of attention to the four other domains of spiritual, practical, EOL/death management, and disease management could lead to inconsistencies in care, as lower levels of care guiding documentation will be inconsistent, resulting in unclear best practices (Venturato et al., Reference Venturato, Kellett and Windsor2007). It is necessary for future guiding documents to satisfy these domains so that no discrepancies arise, and consistency is maintained when developing more specific care guidelines and procedures at lower levels of documentation.

Within the three different types of associations analysed (palliative, professional, and government) inconsistencies in documents among associations were identified. For example, reviewed documents from professional associations (social work, nursing, physicians, spiritual care) were found to meet the Square of Care domains more often than the additional palliative care topics when compared with the palliative and government association documents. These professional association documents addressed more clinical care issues (more documents addressed disease management, EOL/death management and physical domains of Square of Care) when compared with the reviewed documents created by government and palliative associations. Future research is necessary to explore the differences that may exist among high-level guiding documents within professions.

The palliative and government associations had a similar number of documents addressing additional palliative care topics of support for public education, policy and governance, quality management/accountability, rights/ethics, improving access and equity, and creating comprehensive palliative care programs across sectors. However, when examining the Square of Care domains, there is a difference in the number of documents that address these domains between palliative and government organizations. For example, government organizations have more documents addressing the disease management, physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and practical domains of the Square of Care than do palliative associations. These differences among the three different associations highlight inconsistencies existing across these high-level documents, which could greatly augment variations in future documents in lower levels of care guiding documentation. Consequently, this could affect HCPs’ delivery of care, as there appear to be differences among palliative, professional, and government associations and their positions on what Square of Care domains are important when creating guiding palliative care documents for LTC (Venturato et al., Reference Venturato, Moyle and Steel2011).

Finally, there was a significant lack of content found in reviewed documents addressing palliative care within the LTC setting. Although LTC was cited in nearly all documents, documents were found to be lacking in specific suggestions about how palliative care should be guided within LTC. Once again, this lack of content specific to LTC, similar to the domains that were addressed the least in the Square of Care, can open the door to inconsistencies in care as documents move from general policy to more specific procedural documents. Guiding documents include setting guidelines and policy pertaining to palliative care. If these documents are not suggesting gold standards of care for LTC residents (i.e., from the CHCPA Square of Care), it may result in sub-optimal care, as these gold standard frameworks and guidelines have been found to improve quality of life (Badger et al., Reference Badger, Clifford, Hewison and Thomas2009; Estabrooks et al., Reference Estabrooks, Hoben, Poss, Chamberlain, Thompson and Silvius2015; Kinley et al., Reference Kinley, Froggatt and Bennett2013).

Strengths/Limitations

The strengths of this study included a systematic search strategy for both English and French documents, which was adherent to defined a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. Further to this, when documents were unattainable, associations were contacted directly for access to documents or suggestions of available guiding documents. An additional strength of this study was that a kappa was completed during the screening and data extraction phases of the study to ensure inter-rater reliability.

Although there were many positive aspects of this study, there were some limitations as well. In this study, documents were only assessed at the higher guiding document level (excluding legislative documents) and more specific facility organizational and procedural documents were not assessed. Future research will be necessary to analyse inconsistencies with different types of legislative, organizational, and procedural documents. Finally, this study only looked at national documents and those within Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, limiting the generalizability of the results to other Canadian provinces. Future research should be conducted for the purposes of evaluating palliative care documentation pertaining to LTC homes within the provinces and territories not included in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this document analysis has identified new information pertaining to LTC and palliative care guiding documents. Information related to the characteristics of these documents has been outlined, and it has been identified that more province-specific palliative care documents are needed within Alberta, Saskatchewan, Quebec, and Manitoba, with Saskatchewan and Manitoba being in particular need of documents guiding palliative care. Creation of these documents is necessary in order to address province-specific palliative care issues and to ensure high quality palliative care for LTC residents.

A lack of consistency and structure was found among palliative, professional, and government organizations, resulting in inconsistencies among documents. This leaves room for misinterpretation of palliative principles and guidelines, as documents are created at lower levels of documentation, including procedural documents. Associations are challenged to improve this structure among each other, and to provide more consistent documentation, in order to avoid discrepancies in care.

The domains of EOL/death, practical, spiritual, and disease management were found to be addressed the least. Also, it was found that LTC- specific documents are lacking across all provinces and nationally. It is necessary for organizations to address these lacking domains and to create specific LTC guiding documents to ensure consistency and help guide HCPs in the delivery of care to LTC residents. By ensuring consistent standards of practice through utilizing the Square of Care within policy documents, discrepancies in care should be reduced as more specific LTC home and practice documents are created, thus improving quality of life and care for residents receiving palliative care across Canada.