Introduction

Nordic and German-speaking countries belong to different worlds of general welfare states. In the neglected field of housing welfare, however, in the 1990s Sweden, Denmark, and the German-speaking countries were heralded by the influential housing scholar Jim Kemeny (Reference Kemeny1995) as having the same unitary tenure regime: the European cost rental alternative to Anglophone high homeownership countries.Footnote 1 Whereas the latter were said to direct all housing subsidies toward giving more people a chance of homeownership, the European countries maintained a subsidized low-cost rental sector as a viable alternative housing tenure (ibid.). Taking a longer historical and urban perspective from the 1920s up to the current day, however, we show that the two country groups have, in fact, developed into quite divergent housing regimes, putting Nordic countries on par with the Anglophone, high-homeownership countries nowadays and leaving the German-speaking countries as the only ones left with a majority of households in tenancy. Nordic countries, but not German-speaking countries, have also been caught up in the long mortgage debt/house price spiral since the 1990s, which has not only resulted in much higher homeownership rates but also higher levels of mortgage debt per GDP. Figure 1 displays the two almost separate housing worlds countries have diverged into over time. So, what has made Nordic and German housing regimes so strikingly different over time?

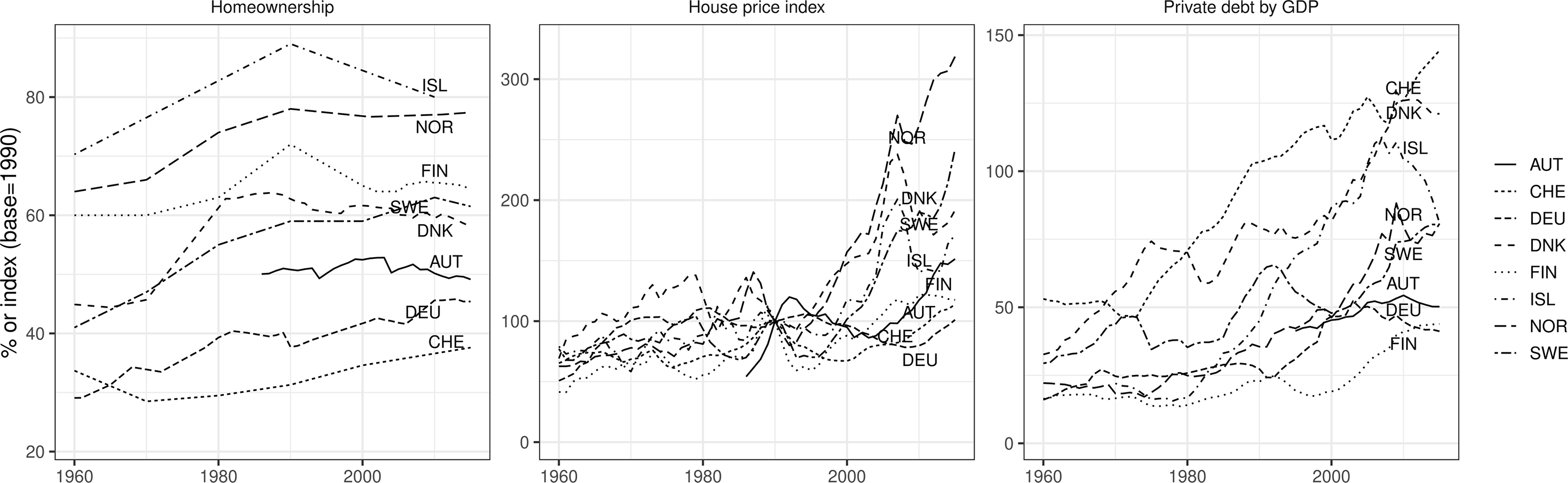

Figure 1. Homeownership rates, mortgage debt, and house prices, national trajectories.

Source: Homeownership (Kohl Reference Kohl2017); Mortgage debt and house prices (Jordà et al. Reference Jordà, Schularick and Taylor2016; Knoll et al. Reference Knoll, Moritz and Thomas2017), for ISL and AUT household debt from IMF Global Debt Database and house prices from the Bank of International Settlements.

Using Germany and Norway as historical case studies, this article suggests a yet unexplored explanation of the German–Nordic divergence, that is the different traditions of owner and tenant cooperatives with their country-specific social-democratic support. Existing explanations of country differences tend to highlight the particular rural family farm background of peripheral Nordics (Annaniassen Reference Annaniassen2006; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1999), which included fewer postwar housing shortages or a long tradition of liberal mortgage conditions (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2018). While these are all important explanatory factors, we argue that they are in themselves not sufficient because countries’ urban centers started from similar tenure conditions at the onset of the last century, as our historical collection of urban housing tenure data suggests. Starting in the interwar years, however, social democratic parties were in national and local government for the first time and thus, building on preexisting cooperative structures, were able to steer their country’s response to the postwar housing crisis. Across all the countries in these groups, social democratic parties wanted to protect workers from unregulated private rental markets, but they all had different answers to what Friedrich Engels (Reference Engels1872/3) called the “housing question.”

Our historical comparison of the German and Norwegian case illustrates how divergent social democratic ideologies reinforced the spread of tenant cooperatives (or similar types of housing tenure) in urban Germany, while owner cooperatives (or similar types of housing tenure) became the norm in urban Norway. Norwegian owner cooperatives then became the main contributor to homeownership growth and their liberalization led to mortgage and house price increases, whereas there was no comparable deregulation or sale of rental units from tenant cooperatives to sitting tenants in Germany. When liberalized, owner cooperatives morphed into a form of tenure that was analogous to ownership, whereas tenant cooperatives resisted full-blown liberalization. As a more general contribution to historical sociology, our argument highlights the civil society origins of the considerable differences observed in the usually neglected field of housing welfare. These origins preconfigured later welfare developments. Moreover, ideological differences within parties of the same political family are also relevant.

The first section introduces the comparative historical background of housing developments in the Nordic and German-speaking countries during the last century, demonstrating that there are important country differences to be studied. It also presents existing explanations and the broader welfare literature in which our historical comparison is embedded. The next section comprises in-depth case studies of Norway and Germany, which illustrate the different housing trajectories since the 1920s with particular focus on cooperatives and social democratic housing approaches. The discussion section probes a generalization of the case-study findings for other members of the two country groups and highlights the article’s general contribution to historical welfare studies.

Theoretical and Comparative Background

Comparative Background of German-Speaking and Nordic Housing

Following Kemeny’s seminal work, the housing literature has tended to group the German-speaking and the two largest Nordic countries—Sweden and Denmark—together as integrated rental markets, where a set of nonprofit housing providers and a private rental market offer an alternative to homeownership.Footnote 2 From an Anglophone point of view, this broad categorization of countries makes sense as all European countries historically lagged behind the United States, Canada, and Australia in terms of homeownership rates. However, if we take a closer look over a longer period, notable differences between the Nordic and German-speaking countries can be identified, not only regarding housing tenures but also with regard to the not unrelated development of house prices, mortgage debt, and tenancy regulation.

In terms of homeownership rates, Norway, Finland, and Iceland have long overtaken the English-speaking countries, whereas Denmark and Sweden have at least caught up over the last few decades (see figure 1). The Nordic–German homeownership gap has widened to 10 to 40 percentage points, depending on the comparative cases. This is predominantly driven by specific forms of joint ownership in the Nordic countries: cooperative housing in Sweden (bostadsrätt), Norway (borettslag), and Denmark (private andelsboliger), and housing company ownership in Finland (Asunto-osakeyhtio). These forms of indirect or joint ownership denote different bundles of ownership rights, which also underwent historical changes that saw them move in a free market direction. They are usually regarded as being equivalent to apartment ownership in other countries because residents buy their membership shares at market prices or prices approaching the going rate for owner-occupied apartments. In the housing tenure typology developed by Karlberg and Victorin for the Nordic Council of Ministers (2005), owner cooperatives in Scandinavia and housing companies in Finland are classified as indirect ownership. If these housing forms were excluded from overall ownership in 2010, then the figure for Sweden would be 22 percent lower, for Norway it would be 14 percent lower,Footnote 3 for Denmark, 7 percent lower, and for Finland as much as 31 percent lower.

The German-speaking countries, by contrast, still have considerably lower homeownership rates than their Anglophone and Nordic counterparts.Footnote 4 These figures already include apartment ownership, which is particularly low when compared to Nordic joint ownership, but also when compared with Romanic European countries. German-speaking countries were late to reintroduce these forms of legal tenure after World War II that have grown only moderately ever since. In these countries, the joint-ownership institutions, cooperatives, and nonprofit institutions are part of the large rental market. Here, tenants are usually also members of the associations that own the units and have the corresponding voting rights, but their membership shares only amount to a minimum of about three months’ rents, not the Nordic norm of the full asking price for an apartment. At the last census in 2011, there were slightly more than two million cooperatively provided housing units in Germany, predominantly in the form of tenant ownership, with a further 300,000 units owned by similar nonprofit organizations (e.g., churches). This is equal to the number of housing units owned by private corporate landlords and by municipal housing companies or 5.9 percent of all units. As figure 2 demonstrates, cooperatives, being mainly an urban phenomenon, easily reach more than 10 percent share of the overall stock in cities at present, such as in Berlin in 2011, and even higher shares of the rental stock. Historically, in 1950, the shares amounted to almost 20 percent in cities like Frankfurt and could be even higher. Similar shares have been recorded in the Swiss housing stock and even higher shares in Austria (15 percent) (Whitehead and Scanlon Reference Whitehead and Kathleen2007).Footnote 5

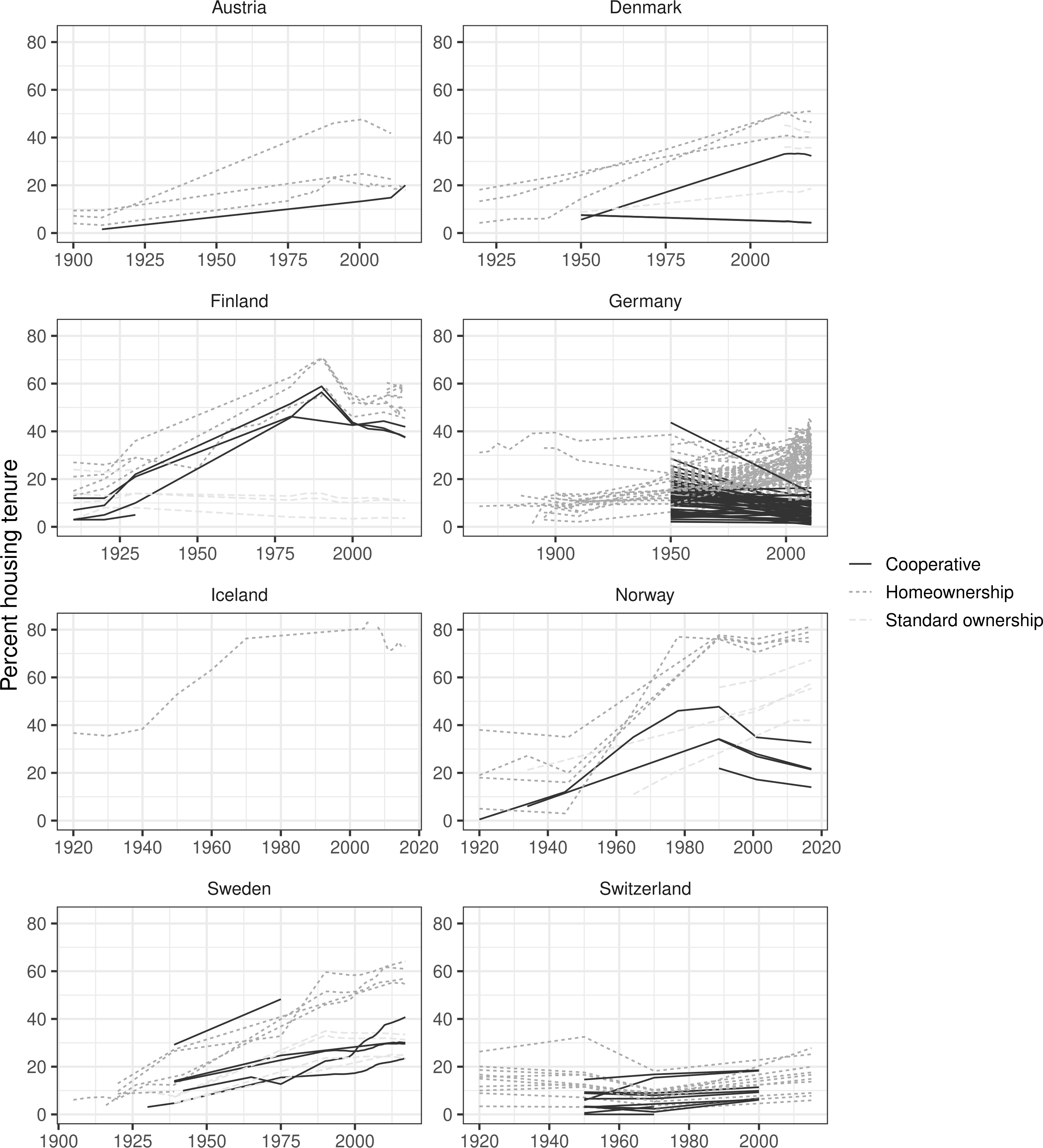

Figure 2. Cooperative and homeownership rates, major cities in all countries.

Source: City yearbooks and regional housing census (benchmarks): Austria (Volkszählung 1910); Germany (Gebäudezählung 1950, Petrowsky, Werner. Arbeiterhaushalte mit Hauseigentum. Bremen: Dissertation, 1993, Zensus 2011); Denmark: Husleje og boligforhold (various since 1920); Finland: Ruonavaara, Hannu (1993) Omat kodit ja vuokrahuoneet. Sosiologinen tutkimus asunnonhallinnan muutoksista. Suomen asutuskeskuksissa 1920–1950. Turku: Turun yliopiston julkaisusarja C 97; Island: Sveinsson, Jón Rúnar. Society, Urbanity and Housing in Iceland. Gävle: Meyers, 2000; Statistics Iceland; Norway: Bolig og Folketellingen (various years since 1920); Sweden: Allmänna bostadsräkninger (various years since 1920); Switzerland (Volkszählungen, various years). Most recent years have been added from the Eurostat Urban Audit Database.

Figure 2 traces the different tenure rates of all major cities in the respective countries, starting around World War I when cooperatives started to grow. Individual cities do generally follow a common trend, but countries also host considerable heterogeneity, with relatively stable city differences over time. In the 1920s, private rental housing initially predominated in most major cities in these countries, with ownership rates barely surpassing 10 or 20 percentage points, except for small cities in Finland, Norway, and Iceland. It is important to mention this otherwise common starting point of urban housing in different countries, as national averages at that time tend to reflect the clear differences in urbanization rates. Figure 2 confirms the same picture on the urban level: Nordic cities’ homeownership is composed of cooperative and standard private ownership. Since the interwar years, the growth in total homeownership in Nordic cities has been largely driven by the owner-cooperative component. The unweighted average of urban cooperative ownership amounts to 32.7 percent in Finland, 26.0 in Norway, and 25.2 percent in Sweden. In comparison, the tenant cooperative component in German-speaking cities is generally smaller in levels and growth. Their unweighted averages are 20.0 percent for Austrian, 10.4 for German, and 7.5 percent for Swiss cities. This descriptive account illustrates the urban significance of the different varieties of cooperative housing. If we imagine a counterfactual scenario, in which Nordic cities had developed their cooperative component as tenant cooperatives, and/or another one, in which German cooperatives had developed in pure owner-cooperative form, the German–Nordic homeownership gap would obviously look quite different. In other words, joint ownership is a crucial factor, particularly on the urban level and in historical perspective.

The second and undoubtedly related dimension along which the countries developed differently is mortgage debt and house prices, as depicted in figure 1. The Nordic countries have experienced an explosion of both mortgage debt and house prices since the 1990s, which have, therefore, reached much higher levels than German-speaking countries. With the only exception of Finnish and Swiss debt levels, figure 1 reveals that the five Nordic countries clearly live in a different housing world than their three German-speaking counterparts in terms of homeownership, house-price trends, and private household debt.

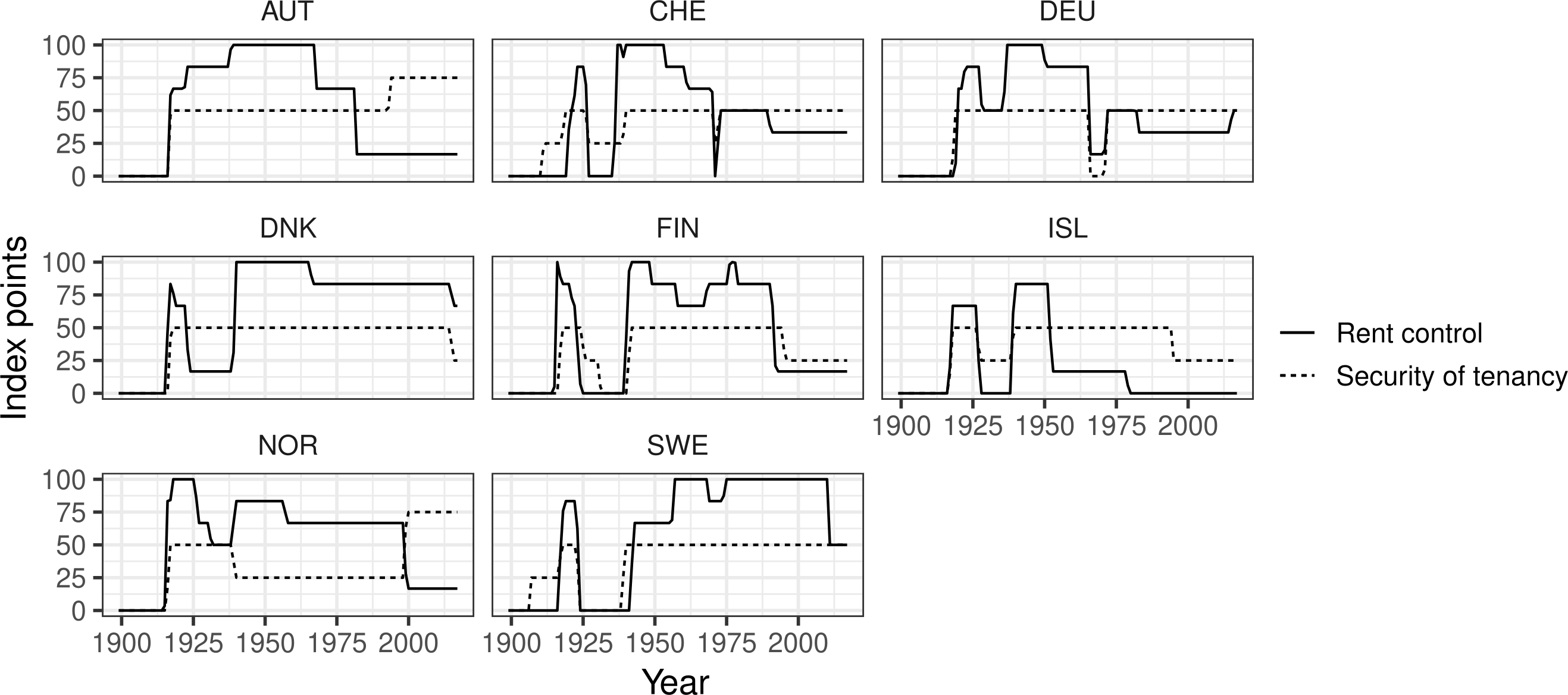

Finally, all countries display broadly comparable development of private tenancy regulation, as measured by regulation indices (from 0 to 100) based on a manual coding of tenancy legislation (Kholodilin Reference Kholodilin2020). Driven by the two world wars, security of tenancy became legally established throughout both country groups. Regarding the regulation of rent prices, however, German-speaking countries made an earlier move to more market-oriented regulation after 1945, whereas the Nordic rental market maintained stricter price regulation, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Regulation of rent prices and the security of tenancy.

Source: Kholodilin Reference Kholodilin2020, https://www.remain-data.org/

Existing Historical Explanations of Homeownership-Rate Differences

Whereas general explanations of homeownership differences between countries, regions, or individual households are abundant (cf. Megbolugbe and Linneman Reference Megbolugbe and Linneman1993), studies addressing these particular German–Nordic differences are virtually nonexistent. In the scholarly literature higher homeownership is associated with demographic factors (old age, family formation, lower population density, urban history path dependencies), economic factors (wage growth, credit access, price-to-rent ratios), and institutional factors (homeownership subsidies, rent regulation, condominium ownership) (Bourassa et al. Reference Bourassa, Haurin, Hendershott and Martin2015; Zavisca and Gerber Reference Zavisca and Gerber2016). These general insights help to understand the different trajectories of Germany in the Nordic comparison in three important ways.

First, the Nordic countries were structurally late urbanizers with widespread farm ownership. This may have contributed to high levels of rural homeownership after 1945. While we think that agrarian ownership patterns are an important, even pre-twentieth-century structural background condition, the proportion of acres in family ownership was lower in Sweden and Denmark compared to the German-speaking countries in 1908 (see Vanhanen Reference Vanhanen2007), even if this hides considerable regional heterogeneity. Of all the countries considered in this article, Norway has the strongest tradition of smallholder farmers. This is reflected in comparative statistics and certainly made homeownership the natural tenure of the countryside and small towns in the postwar era (Annaniassen Reference Annaniassen2001). However, figure 2 also shows that if we control for urban–rural differences by just comparing tenure rates of main cities, then there still is a homeownership gap between the Nordic countries, including Norway, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. This implies that it is not sufficient to invoke differences in agrarian structures when explaining the homeownership gap between Nordic and German-speaking countries.

Second, Germany faced enormous wartime destruction and an inflow of Eastern refugees that, arguably, only massive rental construction could remedy. It is true that Nordic countries also faced pent-up demand and Norway and Finland even considerable wartime destructions, but housing shortages were less severe (Wendt Reference Wendt1962). It was in these postwar years that Germany put in place or revived, for instance, subsidies in favor of rental housing and channeled the majority of reconstruction funds into the new construction of public rental units. While we again think that these historic differences are an important explanatory element, they are also not sufficient. Figure 2 reveals again that the urban tenure differences between the countries predated the post–World War II reconstruction period. A recent study also shows that the most war-affected urban areas in Germany turned out to have higher current homeownership rates, as if clearing the way for a different reconstruction (Caruana Galizia and Wolf Reference Caruana Galizia and Wolf2016). A side-effect of the war was the separation into the two Germanys: East German territories already had lower ownership rates prior to World War II and the socialist housing regime did not reverse the trend. At reunification, the Eastern homeownership rate was down to about 21 percent and current SOEP data show that it is still only at around 35 percent, that is 13 percent lower than in the West (Niehues and Voigtländer Reference Niehues and Michael2016). At the same time, the percentage of tenant cooperatives is about double the German average because the privatization of socialist cooperatives was nowhere complete (Zensus 2011). While the postwar history of the two Germanys, therefore, accounts for some percentage points of the Nordic–German homeownership gap, it does not close it completely, particularly not on the level of many cities, as displayed in figure 2.

A third important difference is mortgage debt. Not only are Nordic countries habitually grouped into the much more “permissive” regulatory mortgage regimes in the current day (Anderson and Kurzer Reference Anderson and Kurzer2020), they also have had a history of much higher mortgage debt levels, as figure 1 reveals, with a large market for mortgage bonds, democratic mortgage access, and very long repayment periods (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2018). Governments stepped in by founding mortgage banks, such as the State Housing Bank in Norway, or controlling interest rates to make credit for new owner-occupied homes widely accessible. In postwar Norway, the political goal of supplying cheap mortgages for homeowners was almost a national “fixation” (Lie and Thomassen Reference Lie and Eivind2016). This contrasts with the traditionally conservative mortgage lending in Germany with high deposit requirements (Kofner Reference Kofner2014). The tradition of cheap money and liberal lending practices may have aided the expansion of owner cooperatives in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, for instance when it enabled tenants to buy their own flats and establish cooperative associations. However, liberalized cooperative housing sectors, as found in Norway and Sweden of the 1980s, also provided a new market for mortgage institutions (Turner Reference Turner1997). In short, the growth of owner cooperatives also lit the flame of financialization and household debt—not just the other way around.

A final explanatory candidate are welfare theories of housing, that is theories explaining housing regime differences with welfare regime theories. The theory that establishes the most direct theoretical link between the two is the trade-off theory, according to which there is a negative association between the degree of welfare provision, particularly pension, in a country and its homeownership rate or mortgage debt levels (Kemeny Reference Kemeny2005). The causal link can be in both directions: high initial homeownership in settler societies impedes generous pension systems from developing (Castles Reference Castles1998) or post-1970 welfare state retrenchment requires more private homeownership provision (Doling and Ronald Reference Doling and Richard2010). The problem with this welfare explanation of the German–Nordic differences is clear: the Nordic countries have better welfare provision than the conservative welfare states, but they also have higher homeownership and mortgage levels.

Theoretical Accounts of Housing Welfare Differences

While these four explanatory approaches all shed some light on the German–Nordic differences, they all have certain limitations. Particularly, the simple fact that different types of cooperatives drive an urban-homeownership wedge between the countries has gone unnoticed. Theoretically, rather than simply trying to shed light on housing differences by looking at general welfare, we draw on two approaches that offer explanations for welfare variation and treat them as a combined reason for housing differences as well: preempting (cooperative) structures and party ideology. Both approaches are influenced by Stein Rokkan’s groundbreaking comparison of the Nordic countries with other countries in continental Europe. A central insight of his work is that antecedent economic, religious, and state structures shaped political party systems and further welfare development (Rokkan Reference Rokkan1999). Rokkan’s work particularly emphasizes that the different conflicts in Nordic and German state formation—anteceding welfare state formation—were important preempting conditions for later welfare state development. The Nordic countries were thus peripheral and more rural, but also became nation-states at an earlier stage, with a rural–urban cleavage line rather than a religious one. This was particularly reflected in the creation of a schooling system without state-church controversy. Germany, by contrast, was part of the more urbanized center and was characterized by belated state formation and a religious cleavage line that led to a cultural struggle between western Catholics and eastern Protestants, particularly around the schooling system.

The religious divide also overshadowed the party systems and party ideology (Manow and van Kersbergen Reference Manow and Kees2009). In Germany, Christian parties were the dominant center-right parties, whereas there was no distinct farmers’ party, with the farming lobby being dominated by the big landlords and not the mass of small-holding peasants (Puhle Reference Puhle1975). In Norway, by contrast, not only was there a strong farmers’ party with mass affiliation but the belated industrial development also resulted in a pronounced shift of the Norwegian Labour Party toward the radical left and only a small communist party. In Norway, the emerging universal welfare state was therefore shaped by the coalition of farmer’s and labor parties (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990), whereas the German welfare state was formed under Christian and other center-right governments, with less active participation of the social democrats (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1990).

One of the more frequent criticisms of Rokkan is that he neglects the agency, intentions, and worldviews of individual and collective actors in history. Rokkan certainly recognized the role played by social groups and other actors in history, but they were arguably given a preordained function or a priori task to perform in his political cleavage and nation-building models (Berntzen and Selle Reference Berntzen and Per1990; Mjøset Reference Mjøset2000; Seip Reference Seip1975). In the view of Berntzen and Selle, Rokkan was preoccupied with the construction of theories explaining structural historical variation between European polities, and never strived to study or make sense of the beliefs, strategies, and power of political actors. It, arguably, follows that Rokkan succeeded in identifying highly relevant contextual factors influencing action, but failed or had little interest in comprehending the subjective motivations of the movers and shakers of history. He may, therefore, be accused of taking actors for granted and thus being “unable to distinguish between why an action is possible and why it has been executed” (Berntzen and Selle Reference Berntzen and Per1990: 140).

In accordance with this reasonable criticism of Rokkan’s work, we acknowledge that the ideologies and strategies of collective actors—such as the labor movement and the cooperative movement—are worthwhile objects of empirical analysis and potentially help explain intracase development and historical variation between units of analysis. However, Rokkan’s “hunger for data” (Mjøset Reference Mjøset2000: 384) and focus on uncovering the key variables driving intercountry differences have inspired our comparative study.

In addition to Rokkan’s work, other welfare studies have pointed to “preemptive conditions” for welfare state formation. First, there are studies pointing to the importance of different religions and particularly the different ethics they preached for how welfare states should deal with nonworking welfare recipients (Kahl Reference Kahl2005). A second group of studies demonstrates the importance of antecedent welfare institutions that either preempted or at least shaped later welfare state interventions. Some examples of this are the influence of US group life insurances in shaping the social security system (Klein Reference Klein2010), the importance of friendly societies and professional health funds for later health insurance development (De Swaan Reference De Swaan1988), and the importance of fire insurance principles for later social insurance principles (Zwierlein Reference Zwierlein2011). The comparative study of cooperatives as important precursors and providers of welfare by other means, however, is still in its infancy (Battilani and Schröter Reference Battilani and Schröter2012). With its focus on housing cooperatives, our article aims to help bridge this gap.

Finally, in terms of party ideology, although there has been substantial comparative work on social democracies, Rokkan’s approach tends to suggest that party positions were structurally predetermined and his works show how political ideology and party strategy created cross-country differences within social democracies. Studies inspired by Rokkan particularly seek to explain differences between countries’ social democracies in terms of their transition from Marxism to economic pragmatism (often Keynesianism), from labor parties to people’s parties, from pragmatism to neoliberalism, and ultimately from mass parties to “clientele parties.” The differences are often dependent on particular periods and are in the timing and degree of each transition. Footnote 6 Berman (Reference Berman1998), for instance, shows how social democracies differed in the timing of their rejection of Marxist orthodoxy, decision to become a people’s party, and shift toward Keynesianism. Andersson (Reference Andersson2010) illustrates how the transition to the knowledge economy was interpreted differently by the Swedish and British Labour Parties. Rueda (Reference Rueda2007) shows how social democracies of the post-1970s differ in their policies, tending either to protect labor market insiders or outsiders. In this literature, German social democracy is usually portrayed as a theoretical precursor for the rejection of orthodoxy, but as a latecomer to the people’s party movement and nonadopter of Keynesianism. The Nordic social democracies, however, are generally depicted as being the opposite (Bergh Reference Bergh1991; Sassoon Reference Sassoon2013). The ideological differences in European social democracy regarding homeownership and housing have not played a role in this comparative literature and, again, our article seeks to fill this gap.

Historical Origins of Housing Regimes: Cooperatives and Social Democracy

We argue that beyond urbanization, reconstruction, mortgage, and welfare history as explanatory factors of German–Nordic differences, the differential development of cooperative housing with its differential social democratic ideological support ever since the interwar years is, as of yet, an overlooked ingredient in a fuller explanation. Housing cooperatives of both the owner and tenant forms predate the interwar years, but it was only the subsequent political support, particularly from the social democratic parties, that contributed to the diverging growth across the different countries and led to their takeoff after World War II. In the following, we illustrate the different historical paths of social democracy and cooperative housing in Northern Europe by way of an in-depth analysis of the German and Norwegian cases.

We have singled out these two countries for closer scrutiny because they align closely with ideal type descriptions of social democratic parties as supportive of tenant cooperatives (Germany) and owner cooperatives (Norway). Moreover, Germany is the country where tenant cooperatives were historically most pronounced and Norway, together with Sweden, had historically developed among the highest owner cooperative shares. Finally, we were able to draw on a wide range of original research on social democracy and housing cooperatives in both cases. This has made it possible to conduct a symmetrical historical comparison, meaning that a similar amount of time and effort has been spent analyzing the particular features and differences of the two country cases in question. The symmetrical design of our study differs from “asymmetrical historical comparison” (Kocka Reference Kocka1999), where one shadow case is superficially researched to provide a comparative contrast to the main unit of analysis.

Germany’s Tenant Cooperatives

Compared to consumer, producer, or farmer cooperatives, housing cooperatives were latecomers and always required help from above. The first generation of German nonprofit housing associations goes back to the nineteenth century when a broad variety of housing reformers, philanthropists, and foundations succeeded in building up to 10 percent of newly constructed housing. The Rhineland, Frankfurt, and Berlin were important regional precursors here (Bernet Reference Bernet2008). While the pioneering foundations taking a top-down approach go back to 1848, nonprofits and bottom-up cooperatives largely took off with Bismarck’s 1889 invalidity and pension insurance law for workers, which, being partly capital-funded, made it compulsory to invest funds in nonprofit undertakings for workers; the 1911 extension of the pension law to white-collar employees even led to the establishment of one of the largest cooperative housing associations (Wilke Reference Wilke2020). Before 1914, workers’ pension assets amounted to nearly 3 billion RM—about half the amount of total assets held by the big life insurance industry—of which up to a quarter were invested in mortgages, up to 5 percent in real estate outright (Kaiserliches-Statistisches-Amt). The preference was to put these funds into housing cooperatives with their capital needs and nonprofit status as opposed to giving out single mortgage to individual builders. Without this support from above, housing cooperatives—which are much more capital-intensive than consumer and other cooperatives—would have been barely more than a niche phenomenon. This way they contributed on average an estimated annual 7 percent to new construction in major cities between 1895 and 1913 (Wischermann Reference Wischermann1997). Moreover, in 1889, the new cooperative law also limited the liability of individual members to their member shares. Cooperatives existed in both owner and tenant cooperative form and, from 1897 to 1917, there was even a temporary split along this line in the national association of cooperatives (Jenkis Reference Jenkis1973). Tenant cooperatives, however, started to prevail with more construction being carried out in urban areas and in the multifamily unit form, whereas owner cooperatives were tied to a single-family house ideal, which was difficult to implement in urbanizing Germany. From an ideological perspective, owner cooperatives were preferred by reformers, but, in practice, more difficult to establish because they made workers immobile and required much more equity from them.

The Weimar Republic saw the second, much more politicized generation of cooperatives and other non-profit associations, this time founded by professional tenant or veteran organizations (Heimstätten), churches, or unions with the objective of creating their respective residential utopias and of simply coping with housing and capital market shortages. Cooperatives were said to be “born out of necessity.” The prewar division between more family home–oriented suburban settlements of traditional style supported by the church, Christian unions, and the Catholic Center Party, on the one hand, and those comprising of tenant cooperatives in multiunit buildings of modern style supported by center-left parties, on the other hand, persisted, even if the correlation between urban morphology and political orientation was not particularly clear cut (Novy Reference Novy1983). In addition to cooperatives, housing associations also took on the form of limited corporations or nonprofit stock companies and all these different nonprofit entities became members of a national nonprofit association in 1934 and then a second similar new association created in 1949 (Tiemann Reference Tiemann1967). The pension funds of workers and employees grew again to about 5 billion RM each—together approximatively matching the total assets of life insurers (Borscheid and Drees Reference Borscheid and Anette1988)—invested at 41 and 46 percent in housing in peak years (Kaiserliches-Statistisches-Amt).

Even though municipalities also undertook housing construction, a German “Red Vienna” was not feasible due to less stable left-wing governments (vgl. Ruck Reference Ruck1987) and German cities having more limited tax autonomy compared to Vienna, which had both city and province status. Vienna’s high share of municipal construction—even here, 11 percent of municipal construction had cooperative roots—thus remained a singular case among German-speaking cities (cf. figure 2). Even in a city state like Hamburg, municipal housing construction only amounted to 3 percent of new construction units on average during 1935–37, where 19 percent were built by the nonprofits and cooperatives with their long tradition (Spörhase Reference Spörhase1940), the remainder being private (Statistisches-Amt 1939). However, German city governments discovered the potential of nonprofits as an instrument for new housing construction and recipient of the rental tax levied on all mortgages outstanding in 1923. The preferential subsidy treatment of nonprofits in times of posthyperinflation and capital market breakdown established cooperatives as an important form of tenure. The prevalence of tenant cooperatives, particularly after World War II, is connected with the simple fact that owner cooperatives usually fulfilled their primary purpose when all units were completed. Cooperativists warned against making members owners of their units as they would subsequently privatize (Tiemann Reference Tiemann1967). In tenant cooperatives, tenants also felt less and less as the de jure owners of their cooperative (Komossa Reference Komossa1976). From the perspective of housing policy makers, owner cooperatives are unreliable. Once subsidies are paid back and without further restrictions, owner cooperative units often become indistinguishable from other ownership units (Novy Reference Novy1986). In Switzerland, for instance, members of owner cooperatives were free to take over their respective housing units after 15 years and sell them at speculative prices (Ruf Reference Ruf1930). This even occurred in the very first continental owner cooperative of this type, the Cité ouvrière in Mulhouse, which was heralded across World Exhibitions in the nineteenth century as the bourgeois solution to the housing problem (Bullock and Read Reference Bullock and James1985). In contrast to owner cooperatives, tenant cooperatives can go on building and receiving subsidies even beyond the initial construction project. The German nonprofit law even prescribed that nonprofits had to build and invest all surplus funds into new construction. The cooperative principle of exclusively serving members was even lifted as tenant cooperatives also acted as builders for non-cooperative housing. The principle is also easier to achieve for tenant cooperatives because members only need small sums of money to buy their shares, whereas ownership cooperatives often require a share corresponding to the use (or market) value of one housing unit. The relatively good accessibility for members and the construction work they carried out for others were thus two ways in which tenant cooperatives could go beyond the restrictive member principle. Catering to customers beyond committed members was one of the successful survival strategies of cooperatives (Novy and Prinz Reference Novy and Michael1985).

Cooperatives would have remained a marginal phenomenon without housing subsidies. Political support was an important factor in the rise of cooperatives, which persisted in a rather owner-occupied family-house form of conservative political denomination and the stronger multifamily-house-centered tenant cooperatives supported by social democrats. The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) became the principal proponent of tenant cooperatives over time. A look at party manifestos reveals that conservative parties in both Germany and Norway had a clear homeownership preference and that it is among left-wing parties that one finds cross-country variation (Kohl Reference Kohl2018). Initially though, following Engels’s Housing Question of the 1870s, the SPD abstained from any concrete housing policy plan other than the intention of eventually nationalizing the housing stock and construction sector. Engels also warned socialists not to follow the bourgeois homeownership ideology. Under Bernstein’s reformism, the municipal socialists, particularly Kampffmeyer (Reference Kampffmeyer1900), started to shift this revolutionary stance toward pragmatic support of cooperatives in the early twentieth century. More pragmatic municipal reformers opposed the social democrats’ inactivity on national housing policy. This shift became apparent at the party’s national assembly in 1901 where it announced its opposition to “support of homeownership for the workingmen on the grounds that workers can only sell their houses at good prices if they have their full mobility and that this mobility is restrained by these very houses which is why industrial and agrarian entrepreneurs, with their corrupt gifts, want to put workers in shackles” (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands Reference Sørvoll and Bo1901).Footnote 7 During the same assembly the municipal reformer, Südekum, therefore proposed entrusting tenant cooperatives with housing construction. He was not in favor of the state or municipalities being given responsibility for housing construction and certainly not the “owner cooperatives, these speculative cooperatives, which put the petty ‘small, but mine’ center stage. By their very nature, they are only for the worker aristocracy, the masters and the kind. But the harm caused by capitalism won’t be removed by creating even more usury. We only want cooperatives in joint ownership and joint administration of buildings” (ibid., 300).

When attempts to socialize housing along with the rest of the economy failed in 1919, trade unions—particularly following their annual congress in 1922—also actively supported the cooperative alternative by setting up production cooperatives for the construction of cooperative housing units. Housing became subject to the more general idea of a “social economy,” which stood for the nonrevolutionary path of public nonprofit organizations in domains like banking, insurance, and the utility sector (Novy and Prinz Reference Novy and Michael1985). With the end of the property census in local elections in 1918, the social democrats conquered city councils in major cities and found old and new cooperatives with similar ideologies to be convenient recipients of land and other supply-side subsidies. Even though the SPD only participated in two of Weimar’s central governments, it was thus able to start a legacy of local cooperative housing, particularly in cities like Berlin, Hamburg, and Frankfurt (May Reference May1928). Cities did not have the tax autonomy of the Viennese to become large-scale constructors in their own right, even if they also started some municipal housing, particularly where the cooperative movement was weaker. Instead, they were able to rely on the newly established tax on rent payments levied on the existing mortgages from 1923, the Hauszinssteuer (Bangert Reference Bangert1937; Mullin Reference Mullin1977). This public capital replaced the absent private means after hyperinflation and was levied on the grounds that inflation had freed landlords from all mortgage debt. With public capital being diverted for general welfare during the Great Depression, this alternative construction system gradually disappeared again. Under Nazi leadership, housing associations were ideologically converted and geographically concentrated with a view to making them construct new cities in conquered territory. Ultimately, however, they only provided shelter housing in destroyed Germany (Harlander Reference Harlander1995). Ironically, the Nazi intervention left an apparatus to the Federal Republic that was organizationally more efficient, one in which old ties between municipalities and cooperative housing associations could be revived to rebuild German cities.Footnote 8

The West German SPD had moved even further to the center in the 1950s by also accepting homeownership, though certainly not actively promoting it. On the central level, in the struggle over the housing laws in 1950 and the 1953 amendment, it was particularly the SPD influence, despite being in opposition, that prevented a strong conservative preference for small-scale mass homeownership from prevailing (Schulz Reference Schulz1991). It was the Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU) influence, by contrast, that disconnected the automatic link between social-housing subsidies and nonprofits and cooperatives as sole recipients of them (Schulz 1994). Otherwise their frequency would have been even higher. A look at the SPD’s party manifestos since 1945 does not suggest a strong homeownership ideology (Kohl 2018). Instead, the successful alternative housing system of socially rented and cooperative units and ongoing protection for the remaining private tenants became the SPD’s core position. Even though conservative governments prevailed in the early Federal German Republic, the SPD was able to shape housing realities in the broad coalition for reconstruction, through the federal system and particularly through its dominance in the governance of large cities. Through the federal system, SPD governed Länder were able to channel subsidies in much higher quotas to the social rental sector than the central CDU had intended (Jaedicke and Wollmann Reference Jaedicke and Hellmut1983). In large cities, the social democrats regained their strongholds: “The social democrats had made the nonprofit associations their preferred partner and voted unreservedly for subsidizing them from the Heidelberg manifesto of 1925 onwards. Thus, the housing tax era had created strong organizational, financial and personal ties between numerous city administrations, the social democratic party, the independent unions and the newly founded housing associations” (Schulz Reference Schulz1994: 105). Not surprisingly, almost the great majority of postwar social housing estates, in many cases erected by the union-controlled housing association Neue Heimat, were located in cities where the SPD governed, often with absolute majority (Schöller Reference Schöller2005).

Norway’s Owner Cooperatives

During the late nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century, Norway conducted several cooperative housing experiments, as did several other European countries at the time. As in Germany, these experiments relied on aid from above, either from wealthy benefactors or local governments. Factory owners and other bourgeois philanthropists were instrumental in the earliest attempts at building homes for workers that had cooperative characteristics. In 1896, the local government in Oslo gave financial support to its first cooperative building project. By the 1920s, owner cooperatives had been established in several Norwegian cities. However, these cooperatives were only a limited success (Annaniassen Reference Annaniassen1991; Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1980). It proved hard to organize mass construction of owner cooperatives without the help of the national government or professional nonprofit construction companies. The cooperative housing movement did not make any real headway until it acquired the full support of the social democratic labor movement, first in Oslo from the 1930s and then in the rest of the country after 1945.

Contrary to its German counterparts, the Norwegian Labour Party (DNA) developed a much more pronounced pro-ownership housing ideology. Prior to World War II, several solutions to the housing question were still voiced within the labor movement. These alternative strategies included cooperative housing, small owner-occupied homes, municipal rented housing, and the socialization of all private landlord-owned housing (Maurseth Reference Maurseth1987). In the postwar era, however, the Norwegian social democrats mostly rallied around owner cooperatives and owner-occupied housing, a position they proclaim in virtually every election manifesto. As the party of government for much of the period between 1945 and 1981, the DNA was also able to establish a “socialized homeownership regime” (Norris Reference Norris2016). In Norway, this regime was characterized by general subsidies for housing construction, low and politically controlled interest rates (Lie and Thomassen Reference Lie and Eivind2016), nonprofit distribution of building plots, and a tax system biased toward the interests of homeowners (Bengtsson et al. Reference Bengtsson, Ruonavaara, Sørvoll, Ronald and Dewilde2017).

During and after World War I, the DNA entered a radical phase, siding with the Bolsheviks and joining the Comintern in the process. By the mid-1930s, however, a reformist DNA had become the party of government and lost its revolutionary zeal (Redvaldsen Reference Redvaldsen2011). As part of the reformist turn of the early 1930s, a party that had hitherto championed the industrial working class tried to broaden its appeal to reach the entire population, not least smallholders (Kjeldstadli Reference Kjeldstadli1978). The DNA’s active support of homeownership in the countryside after 1945 can be read as a continuation of its increasing respect for the property rights of farmers during the 1930s. Supporting smallholding homeowners with subsidies provided through state banks made sense in a rural country dominated by family farms. This contrasts strongly with the almost complete absence of organized small farmers in Germany and the SPD’s opposition to small property holders in general and farmers in particular (Lösche and Walter Reference Lösche and Franz1992). The SPD constituency was clearly urban tenants until the party moved in the direction of a people’s party in the 1950s.

In the largest towns, from the 1930s onward, the Norwegian Labour Party was primarily a party of owner cooperatives. The main exception was Bergen, where municipal construction of rented housing continued until the mid-1950s (Nagel Reference Nagel1992). OBOS, a social democratic cooperative building company, was a major force in the transformation of the housing tenure structure in Oslo. In 1920, 95 percent of the population in the Norwegian capital were tenants. Although cooperative housing construction gathered pace in the 1930s, Oslo was characterized by a very high share of tenants until the 1950s (cf. figure 2). Between 1950 and 1980 this “tenant town” was transformed into a city of owner-occupied housing and cooperative ownership with the share of cooperative housing peaking at 46 percent in the late 1970s (Sørvoll Reference Sørvoll2014). At the national level, the share of owner-occupied housing remained almost the same in the first postwar decades, whereas between 1950 and 1980, the share of owner cooperatives increased by approximately 13 percentage points, at the expense of private rented housing (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1980). In Germany, the union-based building cooperatives functioned in a similar way to OBOS, albeit focusing on other forms of housing. They were the largest builders of tenant cooperatives and even other rental units and thus made an important contribution to the housing tenure structure in twentieth-century Germany (Kramper Reference Kramper2008).

Compared to the German SPD, the DNA showed limited interest in regulating the private rental market as a strategy for working-class liberation and security in the sphere of housing. Leading Norwegian social democrats sometimes linked their defense of cooperative housing to a hostility toward private rental landlords. Trygve Bratteli, the deputy leader of the DNA, expressed such antilandlord attitudes in 1951:

In modern society, there are certain fields where private business is conducted and other fields where private business is no longer conducted, or where it is being phased out, and I for one do not accept owning other people’s homes as a field for private business. … Private business should operate in spheres that infringe less on people’s personal, private and family life. (Stortingsforhandlinger 1951: 455)

For much of the postwar decade, the DNA followed the lead of Bratteli and gradually worked toward reducing the size and profitability of the landlord-owned private rented housing sector. In urban areas, wartime rent regulation was extended until 1982 (Oust Reference Oust2018), and, even then, only slowly phased out over a period of almost 30 years. Comparative research suggests that rent regulation crowds out rental units and indirectly boosts homeownership rates (Kholodilin and Kohl Reference Kholodilin and Kohl2021). In the case of Norway, strict rent regulation may have contributed to the widespread sale of rental properties from landlords to tenants as owner cooperatives or owner-occupied flats. The latter form of ownership expanded in the country’s three largest cities from the 1970s (Wessel Reference Wessel1996). Even though rent control was significantly relaxed after 1982, the Norwegian tax system is still less friendly toward landlords than in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands (Crook and Kemp Reference Crook, Kemp, Crook and Kemp2014; Kofner Reference Kofner2014). In brief, the tax system—that was particularly skewed in favor of homeowners in the 1970s and 1980s—has arguably boosted homeownership rates by pushing investors and middle-class consumers out of the rental sector. In general, private renting has not been considered a long-term alternative for either of these groups (Sandlie and Sørvoll Reference Sandlie and Jardar2017).

Why did the DNA reject or fail to consider the tenant cooperative path taken by the SPD? Some historians suggest that owner cooperatives were a natural form of state-supported housing in a country with a strong historical tradition of free and smallholding peasants. Their analysis implies that the agrarian structure rubbed off on the housing institutions in urban areas post-1945 (Annaniassen Reference Annaniassen2001; Sejersted and Adams Reference Sejersted and Adams2011). However, we disagree with this emphasis on the cultural effects of the agrarian structure for two main reasons. First, because the largest Norwegian cities started from a similarly high level of rental tenancy and the German southwest also had smallholding peasants, but no comparable development of owner cooperatives. Second, the key municipal and state documents indicate that homeownership promotion was not at the forefront in the minds of the politicians who shaped the trajectory of postwar housing policy. That cooperative housing provided a path to homeownership for the urban population was admittedly acknowledged in political debates in the 1940s and 1950s. Most famously, the deputy leader of the DNA called for expanding the “joys of homeownership”—hitherto mainly experienced in the smaller towns and countryside (Annaniassen Reference Annaniassen2013)—to the cities, in a polemic speech berating the private landlords and the Conservative Party (Stortingsforhandlinger 1951: 455). Nonetheless, the practical concerns of housing construction, market regulations, housing finance, and the organization of social housing directed at ordinary wage earners dominates the policy documents and political discussions on housing policy after 1945 (Reiersen et al. Reference Reiersen, Thue and Jensen1996).Footnote 9 The cooperative housing companies and the owner-cooperative institution were arguably not chosen as instruments of social housing construction primarily because they provided homeownership to the masses, but largely because they represented an efficient and practical solution to the challenges of municipal housing policy and were in line with the nonprofit ideals of the ruling Labour Party.Footnote 10

Thus, in light of the content of key policy debates, we argue that the cultural effects of the agrarian structure and the desire to mimic the ownership ideals of the countryside were not decisive for the Norwegian social democrats’ promotion of owner cooperatives. Other factors were at play. In the 1920s, the social democrats supported the construction of public rented housing in Oslo and Bergen, and it was arguably the many burdens of this aspect of municipal socialism that primarily attracted the DNA to owner cooperatives. The tenant ownership model developed by HSB—the main cooperative building company in Stockholm—in the 1920s represented an opportunity for the ruling Norwegian social democrats to free themselves from the burden of direct economic and political responsibility for the construction, maintenance, and management of housing (Annaniassen Reference Annaniassen1991; Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1980; Nagel Reference Nagel1992).

The social democratic HSB model was also attractive for the DNA because it promised to solve one of the eternal challenges of owner cooperative housing. The attempts at cooperative building in the early twentieth century had faltered after the first or second building project, a phenomenon often ascribed to the limited willingness of existing cooperative homeowners to take the risk of financing new construction. HSB solved this problem by establishing two organizational levels: the residents lived in cooperative associations that were daughter companies of a large company devoted to continuous housing construction (Wallander Reference Wallander1968; Wyller Reference Wyller2014). Further, HSB was organizationally connected to the tenants’ movement, something that ensured that the interests of cooperative homeowners were balanced by activists calling for increased housing construction. In post-1945 Norway, the cooperative housing companies followed the organizational and ideological example of HSB, albeit with some Norwegian particularities. Most importantly, the tenants’ movement in Norway was much weaker than in Germany and Sweden and, somewhat ironically, supported the social democratic goal of converting private rented housing into owner cooperatives (Sørvoll Reference Sørvoll2014). Despite the lack of a strong tenants’ movement, the cooperative housing companies in Norway functioned as effective partners of the state in the mass construction of housing post-1945. The state, in turn, provided the cooperative housing sector with the capital necessary to build affordable housing that was accessible to large sections of the population. Thus, as in Germany, the civil society providers of cooperative housing in Norway relied on help from above to succeed, but their organizational form differed from their German counterparts. In countries in which the state has provided no or limited support, it has proven harder to establish the cooperative alternative as a substantial housing market segment (Ganapati Reference Ganapati2010).

In short, the combination of pragmatic concerns related to municipal housing, hostility to private landlords, and the attraction of the HSB model seems to have been decisive for the DNA’s urban housing strategy from the 1930s. The preference for owner cooperatives was not a concession to free market ideas or individual economic freedom. Social democratic concepts of owner cooperatives emphasized collective responsibility for buildings and outdoor areas, as well as solidarity between cooperative homeowners, tenants, and the homeless. For instance, cooperative owners were expected to show solidarity with other consumers and the goals of national housing policy by selling their shares and user rights to apartments at way below market rates (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1980; Sørvoll and Bengtsson Reference Sørvoll and Bo2018). Moreover, the initial difference between German tenant cooperatives and Norwegian owner cooperatives should not be overstated. In the first postwar decades, they represented different solutions to the urban housing questions raised by industrialization and mass migration. Both owner and tenant cooperatives were meant to provide affordable and secure housing options for workers and other consumers with limited capital. Over time, however, German tenant cooperatives and Norwegian owner cooperatives diverged considerably. After the deregulation of the 1980s, Norwegian owner cooperatives became functional equivalents of market price owner-occupied apartments and contributed to subsequent house price and mortgage debt increases in general and the housing market crash and banking crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s in particular (Aaamo Reference Aaamo2019; Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1989; Tranøy Reference Tranøy2000). Norwegian housing cooperatives solved many of the problems associated with tenant cooperatives in the German-speaking world during the first postwar decades, including the challenges of affordability, privatization, and new construction. In the long run, however, German tenant cooperatives proved more resilient. In the 1970s and 1980s, many owner cooperatives in Oslo and elsewhere privatized by converting into owner-occupied apartments (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1983).

Discussion and Conclusion

We started out by observing that the German-speaking and Nordic countries are no longer very similar in terms of their housing regimes as traditionally assumed. By contrasting the Norwegian with the German case, we suggested that a central element behind the diverging trajectories has been whether social democracy has supported tenant or owner cooperatives since the interwar period. By highlighting differences in cooperative traditions, we enrich existing explanations that have explained Germany’s comparatively low homeownership rate by its urbanization history, conservative mortgage institutions, and postwar reconstruction history. Can this two-country account travel to other countries of the German-speaking and Nordic world? The generalization works better in some than in other cases.

Developments in urban Switzerland and Austria are broadly comparable with developments in Germany in terms of size, organizational types, and historical development (Lawson Reference Lawson2010). In Austria, cooperatives account for about half of all nonprofit housing associations and are concentrated in urban areas (Kuhnert and Leps Reference Kuhnert and Olof2017). Although “Red Vienna” is the Austrian model that is more well-known internationally, housing cooperatives in Vienna and beyond also play a significant role in the housing market. The social democrats have historically supported the cooperatives and, in fact, the topic of homeownership is virtually absent in their party manifestos over the years. Similar developments can also be observed in German-speaking Switzerland, particularly Zurich (but much less so in French-speaking regions), where cooperatives were often founded before World War I but started to grow during the post–World War I and post–World War II periods with support from the city, the railroad company, and cantonal governments (Schmid Reference Schmid2005). The majority of cooperatives are tenant cooperatives (ibid.). Similar to the German case, the Swiss social democrats—as seen in their party manifestos—hardly ever mentioned homeownership as a policy issue and made the defense of tenants and support of cooperative housing provision the crux of their housing policy. Due to the federal system and strong private interests, however, a national housing policy in their support was not established after 1950 (Müller Reference Müller2021).

As to the Nordic countries, a recent volume of comparative housing history strongly emphasizes the differences between the trajectories of the different housing regimes after 1945 (Bengtsson et al. Reference Bengtsson, Annaniassen, Jensen, Ruonavaara and Sveinsson2013). When we compare these regimes with German-speaking countries, however, there are also similarities that become apparent. These include the expansion of owner cooperatives or similar joint-ownership forms. Sweden is the closest parallel to the Norwegian case. Even though public rented housing was the preferred tenure for the powerful Swedish social democratic party, owner cooperatives expanded rapidly in the postwar years thanks to labor movement patronage, government subsidies, and market-based popularity (Bengtsson Reference Bengtsson1992; Strömberg Reference Strömberg1992). Due to the lack of significant competition from other urban homeownership forms, cooperative housing has had a long-standing appeal to consumers interested in converting their rented flats to profitable investment objects (USK 2005). A large share of the rental units in the central parts of Stockholm were converted into owner cooperatives between the mid-1970s and the present decade (Andersson and Turner Reference Andersson and Lena Magnusson2014; Holmqvist Reference Holmqvist2009).

In Denmark, the social democrats were quite skeptical of owner cooperatives in the first decades after 1945. They regarded it as a potentially speculative form of housing and wanted to safeguard government subsidies to companies providing nonprofit rental housing. Thus, the expansion of owner cooperatives in the wider Copenhagen area from the mid-1970s was not driven by the support of the Danish labor movement but rather by the political forces of the center and center right. However, as owner cooperatives became more widespread, currently accounting for more than two-thirds of housing in Copenhagen, the social democrats came to accept and sometimes even embrace this form of tenure (Sørvoll Reference Sørvoll2014, Sørvoll and Bengtsson Reference Sørvoll and Bo2020). Over the last decade, the prices of Danish cooperative housing shares have increasingly converged on market rates, even though the formal price regulation—removed in Sweden in 1968 and Norway in the 1980s—is still in place (Bruun Reference Bruun2018). In Finland, owner cooperatives have so far never had more than a marginal presence on the housing market. Nonetheless, the Finnish case is the best Nordic example of homeownership expansion through growth of joint or indirect ownership. The Finnish housing companies share many similarities with the owner cooperatives in the other Nordic countries, as they consist of shares in collectively owned entities. This form of urban joint ownership grew from 3 to 32 percent of the housing stock on the back of state support between 1950 and 1990 (Ruonavaara Reference Ruonavaara2005), with the Finnish social democrats making homeownership their preferred tenure for all (Ruonavaara Reference Ruonavaara1999). In Iceland, finally, owner cooperatives had developed since 1932, contributing 5–10 percent to construction, though as pure building cooperatives that dissolved once the goal of construction was achieved, not leaving even a statistical trace thereafter (Sveinsson Reference Sveinsson2000). Only since 1983 did owner cooperatives start to develop along Swedish lines, with social democrats—generally very supportive of homeownership for all—politically supporting it after initial hesitations. In Reykjavik, this form of tenure still only amounts to a single-figure percentage number (ibid.).

In a broader perspective, housing cooperatives of whatever sort have not played a comparable role in the other (housing) welfare regimes, that is Anglophone or Southern European countries. In both groups of countries, the limited support of the state for this type of rental housing is probably responsible for this outcome, but the roots could equally lie in the weak historical cooperative movement. Particularly in Anglophone countries, building societies or saving and loan associations for the financing of individual houses were much more widespread than housing cooperative associations (Kohl Reference Kohl2015). Building societies also successfully overcame the cooperative member-only principle, but then developed into housing finance institutions, not direct housing providers. When state intervention in the housing sector became necessary in the 1930s, American reformers lamented the absence of a bottom-up housing movement that they could have supported (Bauer Reference Bauer1974). In the absence of preexisting civil society alternatives, governments had to establish a system of providing nonmarket housing, such as the council houses in Great Britain or the local housing authorities in the United States. Singular cases of cooperatives founded by Scandinavian immigrants and condolike legal arrangements excepted, the United States did not go down this housing path (Karin Reference Karin1947).

Our historical explanation provides a new element in the picture of why general ownership rates are currently higher in the Nordic countries. The Nordic–German homeownership gap can largely be traced back to the disproportionately high growth of owner cooperatives or similar housing forms in Norway and Finland and, to a lesser degree, in Sweden and Denmark. Not only did this growth not take place in the German-speaking countries but also the difference increased over the course of the twentieth century because the German cooperative alternative developed as a form of rental tenure. We suggested that these differences in tenure development are connected to variations in the regulation of private tenancy: stricter regulation in the Nordic countries has probably contributed to a decreasing supply of private rental units and boosted ownership rates (Kholodilin and Kohl Reference Kholodilin and Kohl2021). In German-speaking countries, the persistence of a larger rental sector might have disciplined house price development in the owner-occupied sector to a higher degree (Rünstler Reference Rünstler2016). Potential buyers in Germany then tend to become tenants, and landlords will not bid up apartment prices if they are unable to get a decent rent return on their investment. Nonprofit rents are more rigid and the competition with private rents and house prices also make the latter more rigid (Kemeny et al. Reference Kemeny, Kersloot and Thalmann2005; Weber Reference Weber2017).

In the Nordic countries, by contrast, there is evidence that the liberalization of cooperative share prices and conversions of rental to cooperative units has not only contributed to a rise in mortgage indebtedness but has also fueled house price bubbles. Here it was the members of owner cooperatives who got a taste for the capital gains of higher house prices, something in which members of tenant cooperatives, by definition, were not interested. For instance, the prices in the cooperative sector in Copenhagen virtually exploded after 2005 when it became easier to use co-op shares as collateral for bank loans (Mortensen and Seabrooke Reference Mortensen and Leonard2008). In Oslo and Stockholm, there was a cooperative housing boom in the 1980s in the wake of financial and housing market deregulation (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1989; Turner Reference Turner1997). According to Turner (Reference Turner1997), prices on cooperative housing in Sweden increased by 180 percent in nominal terms between 1983 and 1990. During this period, recent movers increasingly bought co-op shares with credit obtained from financial institutions and loan-to-value ratios grew rapidly in the Swedish owner cooperative sector.

On a more general level, this article connects the neglected field of housing welfare to the broader welfare state literature in which German–Nordic comparisons are largely underrepresented. In welfare studies, the importance of the cooperative movement, and housing cooperatives in particular, have not been a key element of the research agenda, even though they predated modern welfare states and arguably preconfigured them (Murray Reference Murray2007). The cross-country differences in cooperativism and its incorporation into the welfare structure are an even less studied phenomenon. The varieties of social democratic ideology are also underexplored in welfare studies. Party preferences generally seem to be structurally determined by the class position of parties, their coalitional restraints, or the structural conditions of the country. But, as this article argues, differences in party ideology can create differential structures of political support that have the potential to transform initially small differences into large-scale divergences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hannu Ruonavaara and Jón Rúnar Sveinsson for their valuable input.