1. Introduction

Association football, or football as it is more commonly known outside of North America, is an excellent example of an institution. Indeed, Douglas North used a metaphor derived from a sporting context when explaining institutions as ‘the rules of the game…to define the way the game is played. But the objective of the team within that set of rules is to win the game’ (North, Reference North1990: 3–5). Such a description is perfect for understanding how football is played. Hodgson's (Reference Hodgson2015: 501) definition of institutions as an ‘integrated systems of rules that structure social interactions’ is also appropriate. Football relies upon codified, formal rules that have existed since 1858, enabling interactions between teams and players. The first ‘universal’ set of rules was drafted in 1863. In 1886, the body with responsibility for developing and preserving these rules, the International Football Association Board (IFAB) was founded by the four British football associationsFootnote 1 (IFAB, 2018). These rules have evolved and have been deliberately altered in the intervening years. Today the rules are known as ‘The Laws of the Game’.

Although football is heavily dependent upon the laws maintained by IFAB, the sport (like many others) exhibits elaborate and dynamic sociological features. Symbols, synchronised displays and rituals have deep and life-long meaning to clubs (Morris, Reference Morris1981). Tangential to the laws exists a complex set of informal constraints. These are not created on-high by IFAB or the world governing body, Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), but rather established and preserved by others within the sport. One example of these informal constraints – the focus of this paper – is the traditional jersey colours worn by Football League clubs in England since the 19th century.Footnote 2 As there was little strategic advantage from adopting a set of colours in the 19th century or early 20th century,Footnote 3 the choice was based on the preference of owners. The continued use of the same colours, which in most cases in England now extends for more than 100 years, originates from custom, approved norms of behaviour and habit. From an institutional perspective, this remarkable longevity of the colours worn by these football clubs provides an excellent setting to examine the interaction of formal rules and informal constraints in English society. This is particularly interesting given the resilience of club colours to the intense commercialisation of the football industry in recent decades. Despite rapid commercial change and a noticeable increase in competition off-the-field of play, club colours have been largely unchanged. Although customs, approved norms and habit were important determinants in stabilising colour choices, these now co-exist and are reinforced by commercial motivations such as branding and goodwill, and identity.

The paper continues as follows. Section 2 explores a general literature on formal and informal constraints, and those that exist within football. Section 3 discusses the evolution of the football jersey,Footnote 4 from its roots in the middle of the 19th century, to the continued use of traditional colours in the modern game. Section 4 explores the role played by informal constraints in the stabilisation of football jersey colours, and identifies contemporary explanations to explain the continuity of these today. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Institutional theory and football

In any context, the main difference between formal and informal institutions rests upon the latter remaining in the private domain. The former relies upon design and execution from central authorities (Williamson, Reference Williamson2009). Formal institutions can be described as constraints on an agent's behaviour and are enforced by a set of rules and protected by government (Furubotn and Richter, Reference Furubotn and Richter2005; North, Reference North1990). Conversely, informal institutions are reliant upon a set of spontaneously arising norms, customs and habits, and are ultimately private constraints on behaviour (North, Reference North2005). Unlike formal institutions, these are shaped and enforced by individual behaviour and organisational structure, and are not solely reliant on over-arching legal systems to exist. Football provides a fitting context to observe both formal and informal constraints in society today, given its rule-based structure, combined with more than a century of informal interactions. Prior to exploring formal and informal constraints that exist in football, we begin with a discussion of these often-contested ideas.

2.1 Formal and informal constraints

Society and the state consist of complex institutional structures. The behaviour of agents within these structures is governed by intricate relationships between codes, conventions, customs, habits, norms, rules and traditions. Debate as to what these individually constitute persists, with different interpretations proposed to explain each.Footnote 5 However, regardless of the field of study, there is considerable association between these terms. For example, Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2006: 3) defines a rule as a ‘socially transmitted and customary normative injunction or immanently normative disposition, that in circumstances X do Y’. Rules can include ‘norms of behaviour and social conventions, as well as legal or formal rules’ (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015: 269–270). Lawson (Reference Lawson and Pratten2015) links rules with norms and argues that the former are a ‘representation of norms’ and can be codified. Aoki (Reference Aoki2010), Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Hong, Chiu and Liu2015), Farrow et al. (Reference Farrow, Grolleau and Ibamez2017) and Fleetwood (Reference Fleetwood2019a) all observe the interconnection between social norms and societal rules. The enforcement of rules however differs from that of norms (Tuomela, Reference Tuomela1995). Therefore, a distinction between these two is required. A norm requires consent whereas rules do not and therefore differ by the means in which they impose tasks on people (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2006). The basis of rules can therefore be formal and legal or natural and informal, and based on social norms of behaviour. Hodgson's definition of a rule also includes a place for customs. Custom is critical for rules to become laws. Customary rules can be the basis of moral authority (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2006). It is these that can then act to reinforce the institution they are based up. Customs exist because legal rules are never absolute and allow scope for customs to do their work (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2001).

The interplay between habit and custom can underpin these informal constraints. A habit is the propensity to replicate the same action under similar material circumstances (James, Reference James1892). Veblen (Reference Veblen1899) and the early institutional tradition that has followed, have argued that laws governing social interactions work because they are rooted within a common set of behaviours and habits (Thomas and Znaniecki, Reference Thomas and Znaniecki1920). Fleetwood (Reference Fleetwood2019b) points out that the research of habit psychology is beset by contradictions. Competing terminology persists, with no agreed definition of what defines a habit. However, Fleetwood (Reference Fleetwood2019b: 7) argues that ‘habits are cognitive representations’ and ‘are located in agents’ cognitive systems broadly conceived, more specifically, in procedural memory’ and should not be mistakenly defined as actions.

Habit formation requires repeat behaviour and the passage of time and is a central tenet of the early behaviourist traditions in economics and social psychology (Verplanken and Aarts, Reference Verplanken and Aarts1999). Importantly for what will follow, Rebar et al. (Reference Rebar, Gardner, Rhodes, Verplanken and Verplanken2018: 17) argue that ‘habit is the process that determines behaviour, and habitual behaviour is the output of that process’. The prevailing rule structure in society often helps to create and reinforce habits among the population, and channels behaviour in such a manner that repeat behaviour becomes omnipresent (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2006). Habit and custom should be interpreted not simply as behaviours but rather as dispositions. As Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2004: 656) points out ‘our habits help to make up our preferences and dispositions. When new habits are acquired or existing habits change, then our preferences alter’.

Davis (Reference Davis2003), Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2010) and Spong (Reference Spong2019) each shed light on the emergence of habit and emphasise the role of the broader institutional structure in fostering habitual behaviour. Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2010) explains how habit formation is an incremental process, the result of repeated behaviour. As individual behaviour is replicated, and positive outcomes are experienced, this behaviour is again repeated in order to achieve the same outcome (Spong, Reference Spong2019; Wood and Rünger, Reference Wood and Rünger2016). Again, it is important to emphasise the role of institutional structures in habit development. Although formal and informal constraints circumscribe individual behaviour, the habits that develop are congruent with the social institutions from which they emerge (Spong, Reference Spong2019). They are not however part of these institutions and remain the property of the agent. Habit should not be conflated with formal rules that act as the catalyst for their emergence (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2006).

2.2 Formal and informal constraints of the ‘beautiful game’

Football, like all sports, is dependent upon a set of rules in order to function effectively. Individual clubs are required to coordinate their resources based on the rules which are codified, administered and enforced. Potts and Thomas (Reference Potts and Thomas2018) argue that under these conditions sports are closer to a commons, as outlined by Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990) and Hess and Ostrom (Reference Hess and Ostrom2007). The structures in place to manage the sport and the overarching rules are shared by all agents. Football clubs work under comparable parameters. This results in a unique set of circumstances where both competition (on-the-field of play) and collusion (off-the-field of play) are required to deliver the product to market.

The Laws of the Game are the only set of formal rules endorsed by FIFA. The terms ‘laws’ and ‘rules’ can be used interchangeably in this context. The laws set out by IFAB, although sometimes open to alternative interpretations, cannot be systemically ignored when playing football and therefore assume ‘rule’ status. Enforcement of these laws is customary and has acquired normative status. All stakeholders in football are aware of the explicit set of rules that are enforceable. As a consequence, the game is played within this set of laws. As Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2006) convincingly argues, codified rules are crucial for defining a community of people that share these. Understanding and recognising these laws allows for rule-breakers to be readily identified. Failure to comply with formal rules leads to punishment within the laws of the game.

The role of custom has been crucial for these rules to become laws of the game. In 1848, students studying at Cambridge University agreed upon a list of 11 rules for football, formalising the game for the first time (Cambridge Rules, 1848, 2020). However, Moor (Reference Moor2009a) points out that these Cambridge Rules failed to become commonly accepted beyond English public schools or universities. The rules never became customary and hence failed to become the laws of the game. This honour would instead fall to the Sheffield Rules, first codified in 1858, which would become the norm in the Midlands and north of England. This set of rules formed the basis of the first universal Football Association rules from 1863.

Many informal constraints also exist in football. These are private constraints which flow naturally from emerging customs and norms of behaviour (North, Reference North2005). These consist of resilient systems and entrenched social rules which form the basis for many interactions, allowing participants to effortlessly engage in the sport. The sport therefore relies on both formal and informal institutions simultaneously. Enforcement of formal rules, which players are expected to follow, differs from informal constraints that exist within the sport today.Footnote 6 For example, Law 3.1 of the most recent set of IFAB rules state that ‘A match is played by two teams, each with a maximum of eleven players; one must be the goalkeeper’ (IFAB, 2018: 47). The statement is not open to interpretation. Should a team fail to field a goalkeeper, a game cannot commence because of this formal constraint. Similarly, Law 3.3 states that ‘The names of the substitutes must be given to the referee before the start of the match. Any substitute not named by this time may not take part in the match’ (IFAB, 2018: 47). Again, this formal rule does not require approval or disapproval by players.

On the contrary, it is customary or the accepted norm for a player to kick the ball from the field of play, when an opponent requires medical assistance, as a result of an injury sustained during play. No law currently exists instructing players to do this, yet this informal constraint is commonplace within the sport. On occasion a team may score a goal that is within the rules of the game but not within the spirit of the game. This can elicit responses that are tantamount to acknowledging the breach of an approved norm and are aimed at correcting any wrongdoing.Footnote 7 Other customs extend to fandom and exist across diverse fan cultures. For example, regardless of allegiances, supporters often applaud seriously injured players as they leave the pitch. It is also widely expected that fans obey the custom of silently observing opponents' anthems during international matches. When norms such as these are not adopted, they are generally met with visible disapproval by opponents and spectators.Footnote 8

3. The evolution of the football jersey

Prior to the codification of the first set of rules in 1863, distinguishing colours were worn by competing teams in English public school games. Marples (Reference Marples1954: 84–85) states that records from a pre-1840 football match at Winchester College report that ‘The commoners have red and the college boys’ blue jerseys’. The original 1858 Sheffield Rules referred to the need for distinguishing colours and stated that ‘Each player must provide himself with a red and dark blue flannel cap, one colour to be worn by each side’ (Dunning and Curry, Reference Dunning and Curry2015: 90). As the game became increasingly popular within England various clubs began to emerge. A natural step in this evolution therefore was the foundation of the Football Association (FA) in 1863. From the 1890s, standardised football jerseys started to become commonplace throughout England and have evolved through five distinct phases. These phases are identified from data collected via historicalkits.co.uk.

3.1 Phase one – the early years: 1863 to 1890

Many of the colours used by club teams today in the Football League are motivated by the Victorian public schools or sporting organisations from which the players had received their education (Moor, Reference Moor2009a). For example, Lancashire club Blackburn Rovers were founded in 1875 and since 1878 have opted to wear halved jerseys of white and blue. This unusual jersey design was accompanied by a Maltese cross on the left breast. This colour choice is linked to player affiliations to both Oxford and Cambridge universities; the club crest was an acknowledgement of the Shrewsbury and Malvern school teams from where several of their founders and players received their education (Historical Kits, 2020a). It became the norm for many newly founded clubs to adopt this custom. Although Blackburn Rovers would dispose of the Maltese cross by 1881, the jersey has changed more than 70 times without ever altering from blue and white halves.

The oldest club in existence today in the Football League is Stoke City. According to Leatherdale (Reference Leatherdale1996) the origins of the Staffordshire club go back to 1863. Similar to most clubs at the time, the jersey colour would change sporadically between matches and from season to season, given the absence of any formal rule relating to jersey selection. For example, from 1878 Manchester United wore white and blue, green and yellow, red and white halves, green and all-white, before settling on their red, white and black colours in 1902 (Historical Kits, 2018). Tottenham Hotspur played in navy, sky blue and white, navy and white stripes, all-red and black and amber in the first 15 years of their existence, before settling on their now all-white jerseys. Liverpool originally wore blue and white, Manchester City black and Chelsea green. The black and white stripes of Newcastle United appeared after the club had worn red and black, claret and blue, navy, red and white, navy and orange and sky blue for the first 13 years of existence.

There are some notable exceptions. Nottingham Forest offer an excellent illustration. The Midlands club have played in red from as early as 1868 and have the longest tradition of wearing the same colour in England. The first recorded match the club played was against local rivals Notts County on the 22nd of March 1866. As formal rules regarding colours had yet to be drawn up, both teams took to the field of play wear all-white. All-white strips were used as many of the players also played cricket for the local team (Historical Kits, 2020b). To distinguish between players, Forest wore red caps and County wore blue. According to Nottingham Forest Football Club (2020) at a players meetingFootnote 9 at the Clinton Arms on Shakespeare Street in the city of Nottingham in 1865

‘it was agreed the team would purchase a dozen tasselled caps in the colour of ‘Garibaldi Red’ – named after the leader of the Italian ‘Redshirts’ freedom fighters [Giuseppe Garibaldi], who were popular in England at the time. The club's official colours were established’.

Three years later, the club would wear an all-red jersey and have remained wearing all-red ever since. Thus, the customary wearing of red can be traced to the decision by the first group of players, who were inspired by Giuseppe Garibaldi.Footnote 10 To change from this accepted norm today would be met with disapproval by many stakeholders in the club, especially the supporters. The Laws of the Game do not instruct the club to wear red, nor prevent them from changing. Custom and approved norms of behaviour preclude those associated with Nottingham Forrest – from owners to supporters – from doing so.

3.2 Phase two – rules and customs: 1891 to 1945

Following the foundation of the Football League in 1888, the need for adherence to formal rules – particularly those governing team jerseys – became universal once the league commenced. A consistent fixture list of matches, all of which were interdependent, became the mainstay of the football calendar. The 1891 Football League Annual General Meeting (AGM) proved to be a pivotal moment and saw the introduction of a rule decreeing that no two member teams could register similar colours, to avoid colour clashes, thus imposing a formal constraint on clubs that had not existed previously. Referencing an extract from the Burnley Express in 1891, Moor (Reference Moor2009b) demonstrates how flexible team colours were, with only limited evidence of the formation of custom or norms of behaviour developing. According to the paper:

‘…there are a few alterations, which are as follows: – Everton ruby with blue trimming; Bolton, blue; West Bromwich, navy and white stripe; and Wolverhampton, blue and orange. Notts were thinking of changing their colour, and Burnley made an application to be allowed to use it, but the former upon re-consideration decided to stick with the old flag. West Bromwich have always used the navy and white, and have had it registered as being the senior wearers. Stoke and Darwen are waiting to see what colours Burnley will choose’.

The following year in 1892, the rules on colour registration were altered to allow teams to register the same colours, but with the stipulation that all clubs must have a second set of all-white jerseys available in the event of a clash (Moor; Reference Moor2009b).Footnote 11

The original laissez-faire approach to jersey selection had worked until September 1890 when Wolverhampton Wanderers travelled to Sunderland with a set of red and white striped jerseys, only to find the home team wore the same coloured jersey. This colour clash also resulted in Wolverhampton Wanderers dropping the red and white stripes they had worn for the past 8 years. Instead, management of the club registered ‘old-gold-and-black shirts, quartered and black knickers’ (Historical Kits, 2021). These colours were supposedly inspired by the municipal colours of Wolverhampton and are a manifestation of the West Midlands city's motto ‘Out of Darkness Cometh Light’ (Historical Kits, 2021).

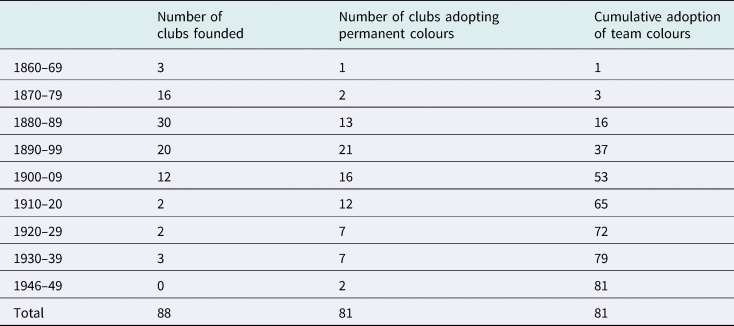

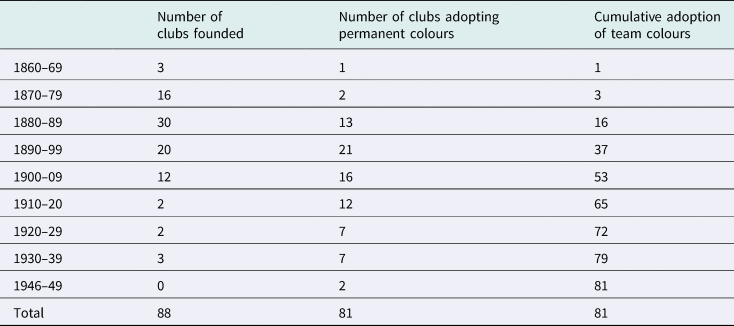

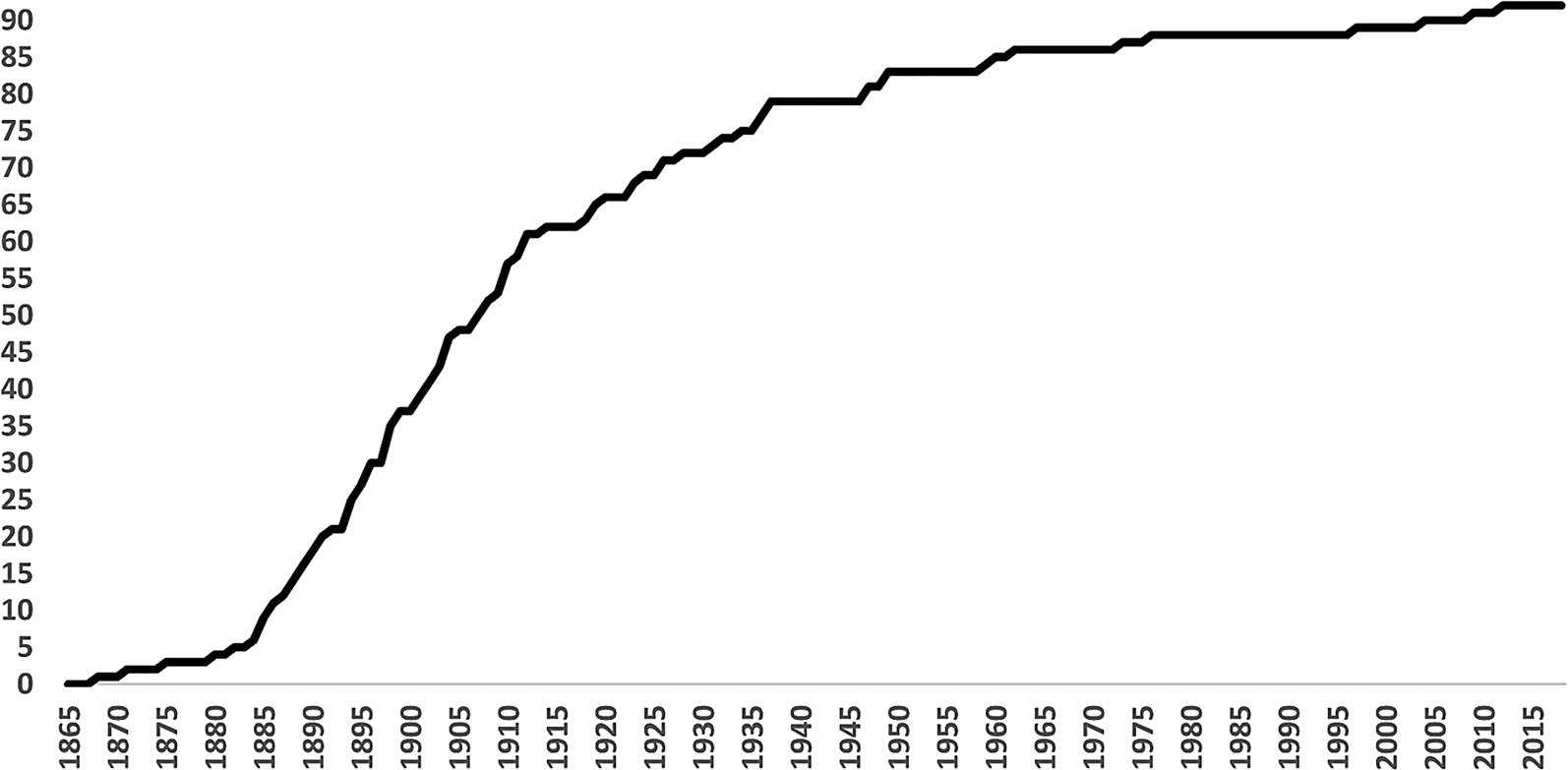

The formal constraint proved highly effective. The cumulative adoption of permanent colours is presented in Figure 1 and illustrates the impact of the instruction to register club colours at the start of the 1891/92 season. Over the next decade, one-fifth of all clubs (19 of the 92) in the Football League would choose, what would become, permanent colours. A record five clubs made this decision in 1898 (Historical Kits, 2018). Not only were clubs not changing colours from this point, but jerseys themselves were altered infrequently. A club could sometimes play for up to 10 seasons without issuing a change of jersey.

Figure 1. Cumulative adoption of permanent colours – 2018/19 Football League clubs. Source: Historical Kits (2018).

Figure 1 illustrates the sharp rise in the number of clubs selecting permanent colours from the 1891 rule. Of the 92 clubs that competed in the Football League during the 2018/19 season, almost 90 per cent had been founded by 1920. 24 of these clubs have only ever worn a single colour. A further 22 settled on a colour less than 10 years after formation. By the outbreak of World War I, 62 clubs wore permanent colours. This would rise to 79 by the start of World War II. Table 1 presents data for permanent colour selection for the 88 clubs in the Football League during the 2018/19 season, founded before the start of World War II.Footnote 12

Between 1890 and 1910, 53 clubs selected colours that remain in use today. Almost 82 per cent of the clubs have worn the same primary colours since 1929. This increases to 90 per cent by the start of World War II.

3.3 Phase three – resilience: 1946 to 1975

Despite a 7-year break from September 1939 to August 1946 of all matches in the Football League, the stability in colours worn by the 88 clubs following the resumption of football after World War II demonstrates the resilience of approved norms and the customary use of colour to an exogenous shock. The capacity to absorb this was complemented by institutional structures and incentives. Despite this continuity however, the wide-spread decision to persist with the approved norm remains relevant – there appeared little appetite for change across almost all clubs. Only two of the current 92 clubs in the Football League changed colour following the resumption of football in England post World War II.Footnote 13

This is demonstrated by Oldham Athletic. The club changed from their traditional blue, first worn in 1910, and took to the field of play in red and white hoops in 1946. This jersey had been borrowed from the neighbouring rugby league club as the traditional blue shirts were unavailable following the war (Moor, Reference Moor2009c). The club returned to blue at the start of the 1948/49 season, when the colour became available to wear again. The decision to return to the traditional blue is unclear but was presumably made by the club's administrators at the time. Oldham Athletic would engage in short-lived colour change again when businessman Ken Bates became chairman of the club in the mid-1960s. Bates introduced an orange jersey which lasted from 1966 until 1971. However, just as had happened with the introduction of the red and white hooped jersey in 1946, orange too was dropped, and the club returned to all-blue from August 1971.

Sporadic change of club colours has occurred since the 1950s, but examples of this are limited. There are just five instances of significant colour change between 1946 and 2012 that have not been reversed. These changes were motivated by issues such as management change (Crystal Palace, Leeds United and Tranmere Rovers), identity (Watford) and professionalism (Oxford United). All five of the clubs have remained in their new colour since the decision to change was made.

3.4 Phase four – early commercialisation: 1976 to 1991

The fourth phase is similar to the first, with regards to the pace of change, but with different causal reasons. Although we do not focus on this, it is important to note that a rapid commercialisation of the sport started apace from the late 1970s. The jersey began to change more frequently. This did not involve changes in colour, as was the case in the first phase in the late 19th century, but rather minor adjustments to the design. A decisive moment arrived on the 24th of January 1976 when non-league Kettering Town took to the field of play with the words ‘Kettering Tyres’ on their traditional red jerseys (Moor, Reference Moor2009b). The FA immediately instructed the club to remove the name or face a £1,000 fine. The club followed this instruction. However, the following season Kettering Town, and several other clubs, proposed rule changes permitting sponsorship on jerseys. These proposals were accepted by the FA in June 1977 (Moor, Reference Moor2009b). This decision was to have a profound impact upon the jerseys of clubs. Between 1977 and the commencement of the EPL in 1992, every Football League club opted to place a sponsor on their jersey.

The appetite for sponsors to align with clubs and jerseys was influenced by the arrival of regular live football on terrestrial television in 1983, following an agreement by British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Independent Television (ITV) and the Football League. At the start of the 1983/84 season, BBC and ITV agreed to broadcast 10 live games for the following 2 years (Butler and Massey, Reference Butler and Massey2019). This was the first-time live English football was scheduled to regularly reach a mass audience. This was to impact upon all elements of the game, particularly the jersey. Stride et al. (Reference Stride, Williams, Moor and Catley2015: 157) point out that ‘…from the mid-1970s the football shirt assumed two further commercial functions, each with multiple stakeholders: a canvas for sponsorship, and as replica merchandise’. Once terrestrial broadcasters lifted a television ban on clubs advertising on their jerseys, the revenue accrued from this income stream began to climb even more rapidly. Stride et al. (Reference Stride, Williams, Moor and Catley2015) demonstrate the rapid rise in jersey sponsorship, which grew from zero at the start of 1978/79 season to benefit almost all Football League clubs by the 1983/84 season.Footnote 14

3.5 Phase five – the Premier League era: 1992 to present

The commencement of the EPL in August 1992 significantly increased the revenues of once local businesses and served to turn provincial English towns and cities into world famous locations (Robinson and Clegg, Reference Robinson and Clegg2018). By June 2020, the BBC (2020) reported that the Premier League generated £5.2 billion in revenue, and together with the other 72 professional clubs in the Football League, paid the HMRC £2.3 billion in taxes. The lower leagues have also benefited from the success of the EPL, witnessing large increases in revenues. The sale of replica jerseys is part of this collective revenue. During the 2017–18 season, the combined value of shirt sponsorship deals was estimated at remarkable £281.8 million (BBC, 2018). This was an increase of more than £55 million on the 2016/17 season. Jersey sales have continued to help revenues climb due to increasing prices and frequent adjustments to the traditional strip. Robinson and Clegg (Reference Robinson and Clegg2018: 196) capture this by saying:

‘It has become an occupational hazard for Premier League fans that when they bought a shirt with a player's name on the back the £70 garment they just splashed out for now had a shorter shelf life than the latest iPhone…the kit designs change every year in a perpetual, ever-so-slightly rebranding of the same basic colour scheme and format’.

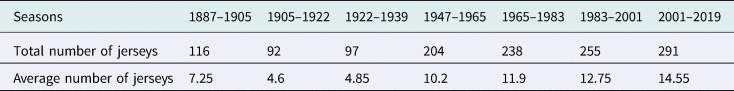

Between 2001 and 2019, the 81 clubs that had rested upon colours by 1949 produced an average of 14.55 home jerseys. This compares to just 4.6 from 1905-1922, 4.85 from 1922 to 1939 and 10.2 between 1947 and 1965. Table 2 demonstrates this further.

Table 2. Total and average number of jerseys worn by 2018/19 EPL clubs

Source: Historical Kits (2018).

Note: The rate of the change during the later phases is significantly greater for clubs that have never been crowned champions of the top tier of English football, rather than those clubs that have a longer history of success. This finding challenges the conventional wisdom that the traditionally stronger and more successful clubs were the catalyst for regular jersey changes. One reason for this difference is due to the changing of sponsors. Three of the most successful clubs - Manchester United, Liverpool and Arsenal - have held longstanding sponsorship arrangements with international brands resulting in less frequent change. At present, the two longest standing sponsorship agreements in the EPL belong to Arsenal (Fly Emirates since 2006) and Manchester City (Etihad Airways since 2008).

This acceleration in jersey change is underlined by all 20 clubs playing in the EPL during the 2019/20 season introducing a new home jersey. This was also the case during the 2018/19 season. Jersey change has effectively reached saturation point. Again, these changes are relatively minor and according to Stride et al. (Reference Stride, Williams, Moor and Catley2015: 176) focus on ‘minor rearrangements of collar and cuff trim, collar and neck styles, and small flashes or piping’. Other aspects that can change from season-to-season include minor alterations to the club crest, the main sponsor or the jersey manufacturer. This is not to say that the jersey will not change but rather the rate of change has become constant. Although informal constraints ensure that the colour will remain the same indefinitely for most clubs, no such institutions govern the changing of sponsors or modification of club crests. However, a relationship does now exist between this social norm and the commercial interests of each club.

4. Colour, branding and identity

The increased rate of change of the football jersey during some 150 years of existence follows an interesting cyclical pattern. Rather than colour changes, clubs today update jerseys from season to season for commercial reasons. The resilience of club' colours can be broadly explained in the context of three important features: informal constraints, identity and branding. Although this paper attempts to illuminate the importance of the first – which we believe acted as the catalyst for what we see today – other casual factors are important to consider. As we detailed, football clubs frequently changed their colours from season to season upon the formal organisation of the sport. This could result in entirely different colours being worn or significant design changes, or both. However, the fixed colour choice of football clubs today illustrates an informal constraint. These traditional colours took time to take root. As Hodgson (Reference Hodgson2003: 164) asserts, such habits act as marks of our ‘own unique history’.

Many clubs are often referred to colloquially by the primary colours they wear, (i.e. ‘blues’ or ‘reds’). As Graybiel (Reference Graybiel2008) points out, habitual behaviour occurs continually, in some cases over years, and therefore can become extraordinarily fixed. This is because Law 4.3 governs the wearing of colours and says, ‘teams must wear colours that distinguish them from each other and the match officials’ (IFAB, 2018: 56). Law 4.3 is a formal constraint, acting as a catalyst for the emergence of custom and approved norms. These formed the basis for the habitual behaviour of agents that would follow. Although the formal rule shapes this habitual behaviour, the habit itself is solely the property of the agent (Fleetwood, Reference Fleetwood2008). It is important not to confuse this decision of the agent, and the habit that results, with the formal requirement of the rules to wear designated colours (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2004; Spong, Reference Spong2019).

Fleetwood (Reference Fleetwood2019b) employs a cinema–popcorn example to demonstrate habit and cue-action behaviour. The use of traditional colours in football jerseys is comparable. In Fleetwood's example a cinema-goer regularly visits the movies and buys popcorn, as she likes the taste. Her first number of visits to the cinema results in the non-automatic or conscious decision to purchase popcorn. After further visits, popcorn is automatically bought. Therefore, the habit of buying popcorn has been acquired. Going to the cinema is the cue and the consumption of popcorn has become the response or action. Fleetwood (Reference Fleetwood2019b: 15) continues:

‘Virtually every time she experienced the cue [going to the cinema], she engaged in the action [buying popcorn]. Anna had gradually, and automatically, built up a cognitive representation of the associations between the experience of the cue and the action…The more she repeated the process of experiencing the cue, along with engaging in the action, the more this cognitive representation strengthened – up to a point’.

As most English Football League clubs changed jerseys many times prior to settling on their colours, the decision to wear these now traditional colours in the first season was not automatic, but rather deliberate. The decision was directly linked to the formal rule changes in 1891 and 1892 regarding the registration of colours. These formal rules, and the approved norms that consequently emerged, resulted in habit formation among agents in each club. As time passed, every time a game was played (cue) the colours were worn (action). The players, management and owners gradually and automatically built a cognitive association between their experience of playing a game and the wearing of these colours. The outcome of the games, or indeed the season, did not seem to matter. Almost all club colours became remarkably resilient, despite seasons ending in failure of some description for the majority of clubs (finishing runner-up, not winning a trophy or relegation). Just as the buying of popcorn was not driven by the sweet taste, clubs did not choose colours because they were winning. If either were the case, the cue–action relationship would not be fully automatic and would rather be goal dependent (Fleetwood, Reference Fleetwood2019b).

These norms, emerging through more than a century of interaction between agents, now work together with identity and commercial interests. Commercial dynamics in football have allowed the proliferation of replica merchandise to generate significant revenue streams for clubs over the past three decades. The interaction between informal constraints and marketability has created a combination of stability (by means of colour) and ongoing variation (through composition changes for commercial benefits). The habitual mindset of the supporters and agents within each club is cradled within a modern commercial industry, both reliant on one another.

4.1 Branding, goodwill and reputation

Seminal research by Klein and Leffler (Reference Klein and Leffler1981) argues that generations of economists, from Alfred Marshall to Friedrich Hayek, identified the importance of branding and reputation. Both are used as quality signals to assure performance and imply the likely fulfilment of contracts when third-party enforcement is absent. Repeat sales only occur if customers are satisfied. The effect of repeat sales and the building of a customer base led to the creation of the brand. It is also well-established that brands are valuable assets to firms and contribute to abnormal levels of economic profit (Bronnenberg et al., Reference Bronnenberg, Dubé and Moorthy2019).

Branding and the associated reputation effects create goodwill between the supplier and consumer. The consequence of this for the consumer can be inertia, loyalty and increased switching costs. These switching costs can be financial, temporal or psychological. Bronnenberg et al. (Reference Bronnenberg, Dubé and Moorthy2019: 311) argue that psychological costs include ‘the cognitive hassle of changing one's habit’. The relationship between brand choice and habit formation is further explored by Pollak (Reference Pollak1970), Becker and Murphy (Reference Becker and Murphy1988), Bronnenberg et al. (Reference Bronnenberg, Dubé and Gentzkow2012) and Atkin (Reference Atkin2013). These empirical studies document evidence of persistence in brand preferences and choices. The findings largely support the important role of informal constraints in the success of branded goods and subsequent buying patterns (Bronnenberg et al., Reference Bronnenberg, Dubé and Moorthy2019).

Inertia towards a brand – which includes a symbol, mark, design or colour – has been explored for decades within the context of repeat purchase decisions (Mittelstaedt, Reference Mittelstaedt1969). It is plausible that branding for the majority of football clubs in the post-war period has remained unchanged due to the marketability of the brand, rather than adherence to the custom that saw the colours emerge. The colour of the jersey also generates a form of goodwill, which would become an important aspect of marketing these clubs. Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Glazer and Nakamoto1994) demonstrate how unimportant attributes, unrelated to the quality of a good or service, are persuasive and generate goodwill and loyalty. Goodwill builds through time and acts to increases buyer utility (Bagwell, Reference Bagwell2007; Bronnenberg et al., Reference Bronnenberg, Dubé and Moorthy2019). It is hard to argue that persistent colours worn by clubs acted as anything but a symbol of the ‘brand’ and generated goodwill amongst players, staff, management and supporters. This ironically probably resulted in goodwill spill-overs to rival clubs which became associated with different colours (Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2018).

4.2 Identity

Identity is also owed due consideration when explaining the increasing stability of club colours. Akerlof and Kranton (Reference Akerlof and Kranton2000: 717) maintain the importance of identity to behaviour. Identification within a social group, where one knows few other members, is entirely possible and is the scenario facing the vast majority of football supporters (Hogg et al., Reference Hogg, Terry and White1995). This form of identification requires membership of a large, impersonal group where one forms a collective identity or attempts to fit in, in this instance through wearing recognised colours (Brewer and Gardner, Reference Brewer and Gardner1996; Thoits and Virshup, Reference Thoits, Virshup, Ashmore and Jussim1997).

Although it was not an important financial decision when picking traditional colours, the choice is very important today. Trademark laws in Britain have existed since the 1862 Merchandise Mark Act, and were further developed in 1875 and 1938. These enabled clubs to establish property rights associated with their colours. Today, large sums of revenue are generated annually from the sale of replicate merchandise. Although the original selection of club colours offered no strategic advantage, this is not the case today. Large economic gains are possible from colour identity through the sale of replicate merchandise, particularly football jerseys. This is one of the prevailing reasons why changing club colours is almost never considered by owners. A 2012 colour change (to red) by Cardiff City, motivated by commercial goals, was met with fierce opposition from supporters and resulted in a return to the traditional blue colours.Footnote 15 This one case offers a powerful illustration of how informal constraints such as custom and accepted norms, rooted in over a century of tradition, can elicit emotional reactions when threatened. The commercial decisions of management breached an approved norm of club supporters – typical norm breaches expectedly result in disutility (Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2010).

As the owners of Cardiff City learned, identification through the wearing of the colour blue, which the Welsh club had done uninterrupted from 1908, is crucial to the internalisation process of supporters. Akerlof and Kranton (Reference Akerlof and Kranton2000) argue this point and demonstrate that such a process allows for the development of a set of actions that conform to the group and contrast with those of rival groups. These differences are met with ‘scorn and ostracism’ by competing groups and only seek to affirm the self-image of each group. Cardiff City's blue contrasts with the white of rivals Swansea City and the red of Bristol City. Wearing red from 2012 was not only an afront to Cardiff City's identity but was the same colour as rivals Bristol City. Identification as a Cardiff City supporter is as much about not being red as it is being blue. Individual behaviour can be characterised this way. Not only can one gain individual utility by identifying within the group but can also experience further satisfaction by differentiating from others (Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2010; Davis, Reference Davis2015).

Identity effects also find support in the work of Bénabou and Tirole (Reference Bénabou and Tiróle2011) who argue, despite lacking knowledge, people ‘care about who they are’. Their identity is then created by making decisions that act as signals to themselves and others (Kranton, Reference Kranton2016). These actions – which may be in the form of a colour worn – then create a sense of self-esteem and peer-esteem, much sought after by the individual (Akerlof, Reference Akerlof2017). To break with this can provoke a negative reaction by individuals and the group as it can undermine the sense of one's own self. The creation of identity and the emergence of norms of behaviour are therefore intertwined. Understanding the micro-foundations of identity can provide the platform to understanding norms through actions (Kranton, Reference Kranton2016). The social context – in this case the wearing of a coloured jersey to identity oneself – indicates the form the norm takes, and can provide individuals with feelings of self-esteem, acceptance or self-consistency (Kranton, Reference Kranton2016).

5. Conclusion

This paper explores informal constraints and the evolution of the football jersey over more than a century of football. We draw on institutional interpretations of human behaviour to explain this development and introduce new data to consider the process of change. We identify a rule change in 1891 as a critical juncture in the development of the football jersey and isolate five distinct phases of the evolution. These can be broadly described as frequent and major changes in the late 19th century before a period of stability commences. During this phase, informal constraints become important and clubs start to identify with a preferred colour or combination of colours. These colours have proved remarkably resilient to the changing football environment and commercialisation of the sport. We argue that customs, approved norms and the habits of agents are all crucial to understand why traditional colours have emerged, and largely remained constant. Branding, goodwill and identity further contribute to maintaining the status quo today. Although the modern jersey has essentially gone ‘full circle’, with the current frequency of change akin to that witnessed during the late 19th century, there is one key difference – the colour does not change. Therefore, although we conjecture that the pace of change will not increase, and the colour will almost never change again, loyal supporters need to accept that the home jersey now has a shelf life of about 10 months. At least however it will be the ‘right’ colour.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions made to this paper by organisers and attendees of the 1st Reading Football Economics Workshop, held in September 2019 at the University of Reading, and three anonymous reviewers.