Introduction: Magic and Religion

This chapter explores the relationship between medieval magic and religion, with particular emphasis on the use of objects and material culture in rites of healing, protection and transformation. It extends the practice-based approach developed in the previous chapter (focusing on agency and embodiment) to consider ritual technologies and how they were made efficacious through the interplay of objects, materials, spaces and bodily techniques (Galliot Reference Galliot2015). The term technology is used here to refer to ‘embodied, procedural knowledge embedded in the material world’ (Mohan and Warnier Reference Mohan and Warnier2017: 372) and applied for practical purposes in the healing and protection of the Christian body. Historical and archaeological scholarship generally separates monastic from lay experience and seldom considers shared beliefs and ritual practice. Archaeological evidence reveals that the ritual technologies of monasticism overlapped with those of the laity, particularly in relation to magic and burial. The dichotomy created between the study of ‘institutional’ (orthodox) and ‘popular’ (heterodox) religion has masked common beliefs and ritual technologies, as well as concealing important connections with earlier, indigenous traditions. Medieval archaeologists have begun to challenge this opposition by shifting their attention to the study of medieval ‘folk’, ‘vernacular’ or ‘lived’ religion, in a more holistic approach which considers the material practices of medieval people alongside the formal structures of Christian theology and liturgy (e.g. Grau-Sologestoa Reference Grau-Sologestoa2018; Hukantaival Reference Hukantaival2013; Johanson and Jonuks Reference Johanson and Jonuks2015; Kapaló Reference Kapaló2013).

How was belief in magic reconciled with the spiritual values of monastic life? The boundary between religion and magic can be elusive to twenty-first-century eyes, just as it was to medieval clerics, who debated the overlapping definitions of religion, science, magic and heresy (Rider Reference Rider2012: 8). For example, charms recited over the sick made use of consecrated objects, together with herbs and animal parts, and in combination with religious language and ritual gestures, such as making the sign of the cross. If a cure was achieved, was it considered to have been brought about by miracle or magic? The key issue for theologians was in pinpointing the cause or agency of the marvel: was it effected by the intercession of saints, the occult power of nature or the intervention of demons? Causation was categorised by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century as ‘above nature’, ‘beyond nature’ and ‘against nature’ (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2008: 8). Any suspicion of demonic magic was prohibited by the church as illicit magic, while magic that drew upon the occult power of nature was accepted as licit and part of God’s creation. The term ‘occult’ in the medieval context simply meant ‘hidden from the eye’, and carried no connotations of the supernatural or the paranormal, as it does today. Historians of magic identify the thirteenth century as a transitional point when the concept of ‘natural magic’ emerged, blending classical ideas regarding the virtues of natural substances such as stones, herbs and animals, with Christian ideas about the cosmos. Writing in the 1230s, the French theologian William of Auvergne saw natural magic as non-demonic, regarding it as an innocent consequence of the divine creation of the universe (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2008: 21).

Medieval monks practised certain types of learned magic in which the potential for demonic agency was more problematic, such as divination, necromancy and image magic, rituals that were performed over an image to induce a spirit. The monastic fascination with magic increased in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries with the circulation of newly translated Greek, Arab and Hebrew texts. In monastic libraries, magic texts were grouped with astronomy, astrology, medicine and alchemy (Page Reference Page2013: 2, 5). Monasteries also collected herbal recipes (see Chapter 3), charms and lapidaries, books that explained the marvellous properties of stones. The ritual efficacy of charms relied on the power of substances, tools, sounds, smells and the procedural knowledge of the practitioner to transform their meaning. Charms consisted of powerful magic words or traditional Christian names, such as the three Magi – Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar – which were written on parchment or lead, on objects such as jewellery, spoons and bowls, or even on the body itself. Charms were used by medical and monastic practitioners but were most commonly associated with folk healers, often women (Olsan Reference Olsan2003). Their efficacy was achieved through the interplay of the body with material culture: the remedy was enacted by words ritually sung or chanted and often involving bodily gestures such as walking in a circle around an object. These rites were performed in domestic contexts, often by midwives and herbalists, but charms also played a part in mainstream medical and religious practice.

Magic and religion were brought together particularly around rites of healing, where ritual practice was intimately linked to the body, and in Christian life course rituals such as birth, marriage and death. This chapter considers the use of objects and material culture in ritual performances that may have been intended to heal, protect and transform the living and the dead. The geographical focus is on later medieval Scotland, to address one of the broader aims of this book to contribute to social approaches in the study of later medieval Scottish archaeology. It examines three specific ritual technologies: the use of amulets; the deliberate burial or deposition of objects in sacred space; and the placing of objects with the medieval dead. These practices raise a number of questions surrounding the use and meaning of objects, particularly around agency or causation (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012: 216–18). The person–object boundary is often blurred in rites of magic: wonders are worked by relics that are both persons and things, while the agency of saints can be channelled through any material substance or object that came within close proximity to their remains, such as pilgrim badges, water, or even dust from the saint’s tomb (Geary Reference Geary and Appadurai1986).

Archaeologists studying prehistoric beliefs have challenged the pervasive dichotomy between ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’ that has characterised much archaeological thinking on ritual and religion (e.g. Bradley Reference Bradley2005; Brück Reference Brück1999). Ritual is now regarded by archaeologists as an aspect of the everyday, imbuing all aspects of life (Insoll Reference Insoll2004: 159). Medieval archaeologists have begun to adopt this more holistic approach to the study of everyday belief in the medieval town and countryside (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012). For example, Mark Hall has explored objects excavated from Perth High Street to show that everyday ritual practice in a Scottish burgh blended the cult of saints with traditional apotropaic rites, in other words, those intended to guard against harm or evil. Pilgrim souvenirs of Thomas Becket and St Andrew rubbed shoulders with occult materials such as jet, old coins, Roman glass and Bronze Age flints, some of which were deliberately deposited in a medieval hall (Hall Reference Hall2011). With rare exceptions (e.g. Stocker and Everson Reference Stocker, Everson and Carver2003), this more integrated approach to everyday ritual has not been applied to medieval monastic contexts. Monastic ritual is generally equated with the formal liturgy of Christian worship, commemorative masses for the dead, and the monastic horarium, the daily timetable of religious services in the church. Archaeological evidence illuminates common technologies of magic and challenges the pervasive binary between monastic/institutional religion on the one hand, and popular/lay religion on the other.

Stones and Sacred Words: The Occult and the Divine

The intermingling of magic and religion in medieval Christianity may seem incongruous to us today; however, it was reconciled by the medieval framework of natural magic. Thomas of Chobham, a late twelfth-century English theologian, wrote ‘natural philosophers say the power of nature is concentrated above all in three things: in words and herbs and in stones’ (Rider Reference Rider2012: 40). I would like to concentrate here on the power that medieval people attributed to stones and sacred words. Lapidaries – books of stones – were widely circulated from the eleventh century onwards. The most famous was Bishop Marbode of Renne’s De Lapidus, a book of verse on the properties of sixty stones, dated c.1090 (Evans Reference Evans1922: 33). Lapidaries were popular medical texts that explained the therapeutic applications of each stone, for example whether to wear it next to the skin or to consume it powdered in a drink. They describe the natural properties of gemstones, minerals such as sulphur and lignite, animal products and fossilized materials including coral, pearl, amber and toadstone, as well as mythical stones (Harris Reference Harris, Bowers and Keyser2016: 185–7).

Belief in the power of stones drew on classical authors such as Pliny and Galen, who proposed that all materials of nature contained virtues that could be harnessed by those in possession of the correct knowledge (Kieckhefer Reference Kieckhefer2000). Some of these properties were manifest and easily observed, while others were occult, with their qualities concealed or hidden from the eye. Manifest properties could be identified based on the doctrine of signatures, which proposed that nature marked objects with signs to indicate their use. For instance, red coral was the colour of blood and therefore believed to be an effective remedy to staunch wounds and bleeding. Examples of occult materials with hidden properties are magnetic minerals with a natural polarity that attracts iron; or jet and amber, fossilized organic materials that develop a static charge and emit a smell when rubbed. Medieval writers understood these natural materials as gifts from God, created for the benefit of humankind: to make use of stones was therefore a form of ‘sacred healing’, according to Marbode (Harris Reference Harris, Bowers and Keyser2016: 195).

Medieval people believed in the efficacy of stones long before natural magic emerged as a conceptual framework in the thirteenth century. In Britain, the ‘sacred healing’ of stones pre-dated the circulation of medieval lapidaries based on classical knowledge. For example, Adomnán’s Life of Columba, written at the very end of the seventh century, describes several miracles in which Columba made use of ‘white stones’. These are indigenous quartz pebbles, rather than exotic gemstones such as rock crystal. Columba plucked a white pebble from a stream, saying ‘Mark this white stone, through which the Lord will bring about the healing of many sick people among this heathen race’. He used the stone to bargain for the liberation of a female Irish slave held by the Pictish king’s wizard, Broichan, who was perilously ill. When asked to cure him, Columba replied:

If Broichan will first promise to release the Irish girl, then and only then dip this stone in some water and let him drink it. He will be well again immediately. But if he is intransigent and refuses to release her, he will die on the spot.

According to the vita, the stone was kept in the king’s treasury to cure sundry diseases among the people (Life of St Columba Book II: 33–4; Sharpe Reference Sharpe1995: 181–2). In this example, the stone takes on curative properties by virtue of contact with the saint, in the manner of a contact-relic, and God is explicitly credited with causing the miracle.

There is strong archaeological evidence that in Britain white stones had long been regarded as having apotropaic or healing qualities. White, beach-rolled quartz pebbles were commonly placed with early medieval burials in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and the Isle of Man; for example, they are recorded in burials from Iona (Scottish Inner Hebrides) (O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan, Broun and Clancy1999), Llandough (Glamorganshire) (Holbrook and Thomas Reference Holbrook and Thomas2005), the Isle of May (Fife) (James and Yeoman Reference James and Yeoman2008) and Whithorn (Dumfries and Galloway) (Hill Reference Hill1997). Quartz is piezoelectric: when struck or rubbed together it will produce a faint glow (known as triboluminescence). Like jet and amber, quartz would have been regarded by medieval people as possessing occult properties. White stones evidently carried spiritual connotations associated with indigenous religious traditions, stretching back to the early medieval monasticism of Columba and much earlier, to prehistoric beliefs. For example, quartz pebbles are associated with Neolithic monuments in Scotland, such as Forteviot (Brophy and Noble in prep.), as well as in Ireland (Driscoll Reference Driscoll2015) and the Isle of Man (Darvill Reference Darvill, Jones and MacGregor2002). It has been suggested that quartz carried the symbolic associations of the ocean and mountains. It may have been regarded as generative or transformative to prehistoric and medieval people, with its incorporation in mortuary and pilgrimage contexts conveying the symbolism of water and new beginnings (Fowler Reference Fowler2004: 116; Lash Reference Lash2018). Quartz pebbles were occasionally placed with burials in Britain right into the later Middle Ages and beyond (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2008).

Jet was also regarded by medieval people as a powerful occult material. The deep black substance of jet is fossilized coniferous wood, easily carved into jewellery and objects such as gaming pieces (Hall Reference Hall, Hunter and Sheridan2016b). Jet occurs principally in two locations – near Whitby in North Yorkshire and in Galicia in northern Spain – and in both regions it was used to manufacture holy objects and pilgrim souvenirs. According to Marbode’s lapidary, jet was efficacious if worn on the body, consumed as a powder, ingested through water in which the material had been steeped, or burnt to release beneficial fumes. The healing and anaesthetic properties of jet were recommended for easing conditions ranging from childbirth to toothache, and it was believed to possess powerful apotropaic value to protect from demons and malignant magic (Evans Reference Evans1922). Jet crucifixes have been found in monastic burial contexts, for example from the priories of Gisborough, Old Malton and Pontefract in Yorkshire (Pierce Reference Pierce2013), St James’s Priory, Bristol (Jackson Reference Jackson2006), and St John’s Hospital, Cambridge (Cessford Reference Cessford2015). It has been suggested that jet objects were manufactured especially for monastic use: archaeological evidence confirms that small, jet crucifix pendants were produced in workshops at Whitby Abbey. A distinctive corpus of twenty-two crucifix pendants with ring and dot motif can be dated stylistically to the twelfth century (Pierce Reference Pierce2013). In Scotland, three jet pendants have been recovered as chance finds and declared as Treasure Trove, with examples spread geographically from the Borders to the Highlands (Canmore IDs 141341 (Dairsie Mains, Fife), 7952 (Hill of Shebster, Caithness), 5584 (Trabrown, Borders)). Jet was also commonly used for paternoster beads in England, but only a few examples have been found in Scotland: at Perth Carmelite Friary (Figure 4.1), Elcho Nunnery (Perth and Kinross) and at Linlithgow Carmelite Friary (West Lothian), although the latter may be a reused Bronze Age bead (Reid and Lye Reference Reid and Lye1988: 78; Stones Reference Stones1989: microfiche 12: E10). Jet was also worn by the laity and is found in domestic contexts: for example, a jet pendant and bead were recovered from High Street, Perth (Hall Reference Hall2011).

Objects incorporating gemstones such as sapphires are occasionally found in Scotland and recorded as Treasure Trove. For example, a gold finger ring with a stirrup-shaped hoop with a sapphire cabochon, of twelfth- or thirteenth-century date, was found near Restenneth Priory (Angus: Canmore ID 89912), and another was found at Lamington (Lanarkshire: Canmore ID 339213). Sapphires were regarded as a cold stone to be used for the treatment of excessive bodily heat, ulcers and ailments. This perhaps explains the relatively common occurrence of sapphire rings in the graves of high-ranking ecclesiastics (Hinton Reference Hinton2005: 187), and it is likely that the Restenneth ring was associated with the priory. Objects incorporating blue glass have also been found, perhaps representing a proxy for sapphire, and used in combination with sacred names. A silver crucifix found at Loch Leven (Perth and Kinross) is a strong candidate for a monastic object (Figure 4.2): the front shows Christ on the cross and the reverse is decorated with a large cabochon blue glass gem and the remains of an inscription, which originally read ‘IHESUS NAZRENUS REX IOUDOREUM’ or ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’ (Treasure Trove in Scotland 2013/2014: 10). The object may have been associated with St Serf’s Priory or Scotlandwell Priory, which developed from a hospital and holy well into a Trinitarian priory in the thirteenth century. A silver fede ring from Gullane (East Lothian) (Figure 4.3) was set with a blue glass stone and engraved with the lettering ‘IESUS NAZA’, a contraction of Jesus Nazarenus (Treasure Trove in Scotland 2015/2016: 9). In both cases, two forms of magic were invoked for protection: the healing quality of sapphire (or proxy blue glass) and the holy name of Jesus.

4.3 Medieval silver finger-ring set with a blue-glass stone and inscribed ‘IESUS NAZA’, found in Gullane (East Lothian).

The use of sacred names for healing and protection is part of the popular tradition of textual amulets and charms. Textual amulets were apotropaic formulae written on parchment or other materials (such as lead), while charms included brief inscriptions on a piece of jewellery or a household object. The inscription of holy words transformed these objects of material culture into charms, which were worn on the body and kept in the home to confer protection, good fortune and healing (Skemer Reference Skemer2006: 10). The name of Christ was used for general protection, including IHS and variations on Jesus, while the formula Jesus Nazarenus Rex Judaeorum was popularly believed to protect against sudden death, as documented in ‘The Revelation of the Monk of Evesham’, written in 1196 (Evans Reference Evans1922: 128). The names of the Three Magi served as a verbal charm to protect against epilepsy, falling sickness, sudden death, and from all forms of sorcery and witchcraft (Hildburgh Reference Hildburgh1908: 85). Some medieval authors saw charms and sacred words as part of the conceptual framework of natural magic, including Thomas Chobham, quoted above. Most regarded charms as prayers – they were intended as religious invocations that were distinct from the natural world (Rider Reference Rider2012: 42).

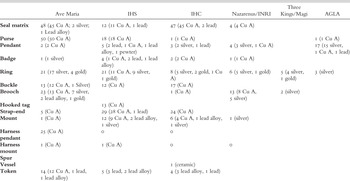

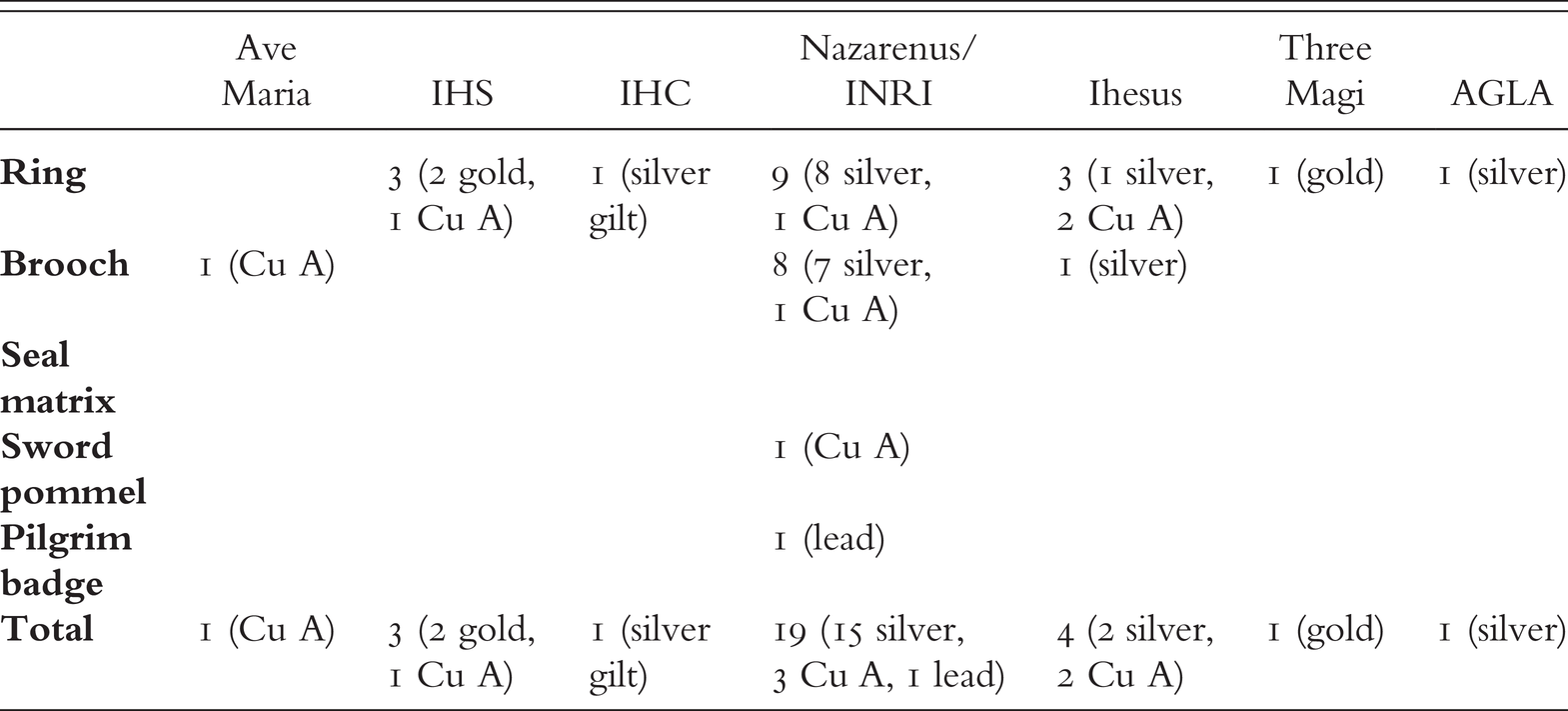

Fresh evidence for the medieval use of charms comes from the objects reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme in England and Wales and the Treasure Trove system in Scotland. The examples from England are much more numerous, reflecting differences in both access to material culture by medieval people and the intensity of metal-detecting today (Table 4.1). Metal-detecting is a less popular pastime in Scotland but it is evident that fewer metal objects circulated in medieval Scotland (Campbell Reference Campbell2013a). At the time of writing, thirty-three medieval objects with sacred names have been reported through Scottish Treasure Trove, inscribed principally on rings (N=8) and brooches (N=8) and also on a range of objects including a sword pommel, a seal matrix, a pilgrim’s badge and a crucifix (Table 4.2). The dedications are distinctive in the very strong representation of the names of Jesus, including IHS, IHC and Jesus Nazarenus inscriptions. Sacred inscriptions to Jesus account for nearly 80 per cent of examples in the Canmore database, nineteen of which are Jesus Nazarenus inscriptions (58 per cent). There is only one inscription to Ave Maria, one to the Magi, and one occurrence of the magic word AGLA (a Kabbalistic acronym for Atah Gibor Le-olam Adonai, meaning ‘You, O Lord, are mighty forever’). This is significantly different from the amuletic objects in the English and Welsh Portable Antiquities Scheme, where IHS and IHC are much more frequently represented than Jesus Nazarenus, and inscriptions to the Virgin Mary are 5.5 times more common than Jesus Nazarenus (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012: 274). The Treasure Trove objects have no archaeological context and little can be said of the circumstances or date of their loss or deposition. The majority are likely to have been possessions owned by the laity but objects with sacred inscriptions are also found at monastic sites. In addition to the Loch Leven crucifix already noted, a silver brooch with inscription is associated with Arbroath Abbey (Angus: Canmore ID 35645) and two silvered rings with inscriptions were found at Inchaffray Abbey (Perth and Kinross; Treasure Trove in Scotland 2008/2009: 16; Canmore IDs 339359 and 332582). An excavated example comes from the burial of an adolescent at the Carmelite friary at Perth, although the inscription was too worn to be legible (Stones Reference Stones1989: 12).

Table 4.1 Medieval objects with sacred inscriptions recorded in the Portable Antiquities Scheme (England and Wales) (as of 9 Jan. 2017)

| Ave Maria | IHS | IHC | Nazarenus/INRI | Three Kings/Magi | AGLA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seal matrix | 48 (45 Cu A; 2 silver; 1 Lead alloy) | 12 (11 Cu A, 1 lead) | 47 (45 Cu A, 2 lead) | 4 (4 Cu A) | ||

| Purse | 50 (50 Cu A) | 18 (18 Cu A) | 1 (1 Cu A) | 1 (1 Cu A) | ||

| Pendant | 2 (2 Cu A) | 5 (2 lead, 1 Cu A, 1 lead alloy, 1 pewter) | 3 (2 silver, 1 lead) | 4 (3 silver, 1 Cu A) | 17 (15 silver, 1 Cu A, 1 lead) | |

| Badge | 1 (1 silver) | 4 (1 Cu A, 2 lead, 1 lead alloy) | 2 (2 Cu A) | 1 (1 Cu A) | ||

| Ring | 21 (17 silver, 4 gold) | 21 (11 Cu A, 9 silver, 1 gold) | 8 (5 silver, 2 gold, 1 Cu A) | 6 (5 silver, 1 gold) | 5 (4 silver, 1 gold) | 3 (silver) |

| Buckle | 13 (12 Cu A, 1 Silver) | 12 (Cu A) | 17 (Cu A) | |||

| Brooch | 23 (13 Cu A, 7 silver, 2 lead alloy, 1 gold) | 1 (Cu A) | 13 (8 Cu A, 5 silver) | 2 (silver) | ||

| Hooked tag | 13 (Cu A) | |||||

| Strap-end | 5 (Cu A) | 29 (28 Cu A, 1 lead) | 24 (Cu A) | |||

| Mount | 1 (Cu A) | 12 (9 Cu A, 2 lead alloy, 1 silver) | 6 (4 Cu A, 1 lead alloy, 1 silver) | 1 (silver) | ||

| Harness pendant | 25 (Cu A) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Harness mount | 1 (Cu A) | 1 (Cu A) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Spur | ||||||

| Vessel | 1 (ceramic) | |||||

| Token | 14 (12 Cu A, 1 lead, 1 lead alloy) | 5 (3 lead, 2 lead alloy) | 4 (3 lead alloy, 1 lead) | |||

| Coin | 0 | 29 (17 gold, 9 silver, 3 Cu A) | 38 (35 gold, 2 silver, 1 lead alloy) | 0 | ||

| Weight | 1 (lead) | |||||

| Book fitting | 5 (Cu A) | 10 (9 Cu A, 1 silver) | ||||

| Plaque | 2 (1 Cu A, 1 lead) | |||||

| Cross | 1 (CuA) | 7 (3 Cu A, 1 gold, 1lead, 1 lead alloy, 1 silver) | 2 (silver) | |||

| Unidentified object | 1 (silver) | 1 (silver) | 1 (Cu A) | 1 (silver) | ||

| Total | 205 (140 Cu A, 29 silver, 4 lead alloy, 1 lead, 1 gold, 59 unknown) | 169 (113 Cu A, 7 lead, 4 lead alloy, 1 pewter, 19 silver, 18 gold, 5 unknown) | 164 (104 Cu A, 5 lead, 12 silver, 37 gold, 5 lead alloy, 1 ceramic) | 37 (18 Cu A, 15 silver, 2 gold, 1 lead, 1 lead alloy) | 7 (6 silver, 1 gold) | 24 (2 Cu A, 21 silver, 1 lead) |

Table 4.2 Medieval objects with sacred inscriptions recorded in Scottish Treasure Trove/Canmore (as of 25 Nov. 2016)

| Ave Maria | IHS | IHC | Nazarenus/INRI | Ihesus | Three Magi | AGLA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring | 3 (2 gold, 1 Cu A) | 1 (silver gilt) | 9 (8 silver, 1 Cu A) | 3 (1 silver, 2 Cu A) | 1 (gold) | 1 (silver) | |

| Brooch | 1 (Cu A) | 8 (7 silver, 1 Cu A) | 1 (silver) | ||||

| Seal matrix | |||||||

| Sword pommel | 1 (Cu A) | ||||||

| Pilgrim badge | 1 (lead) | ||||||

| Total | 1 (Cu A) | 3 (2 gold, 1 Cu A) | 1 (silver gilt) | 19 (15 silver, 3 Cu A, 1 lead) | 4 (2 silver, 2 Cu A) | 1 (gold) | 1 (silver) |

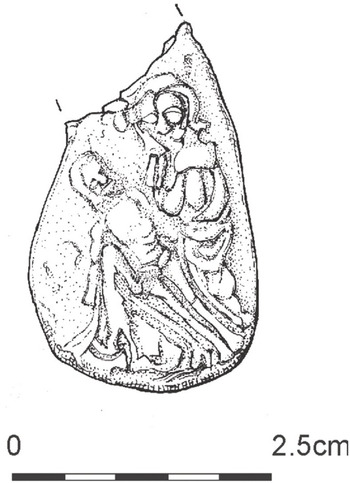

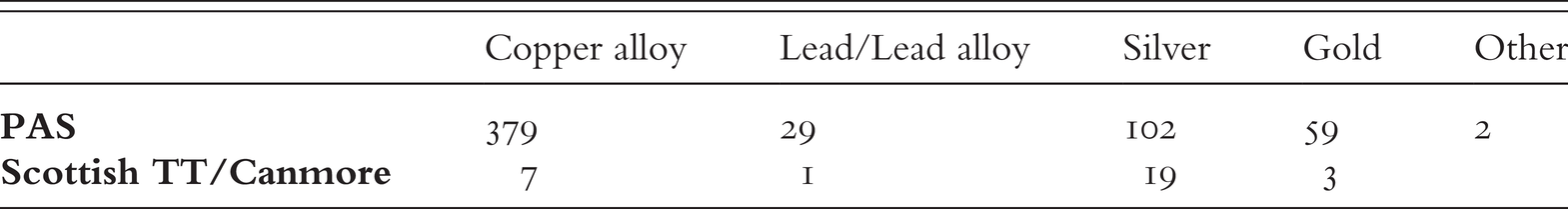

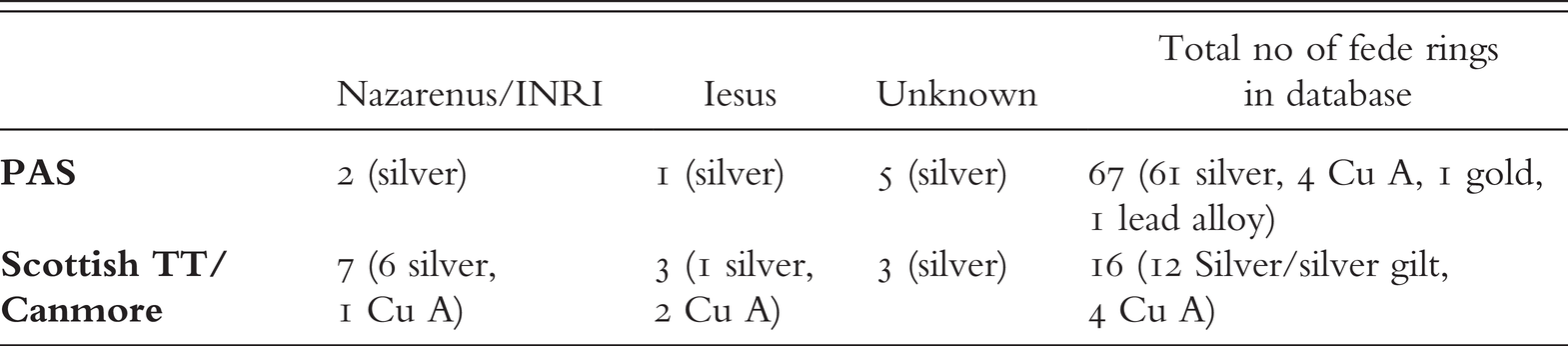

Also distinctive in Scotland is the high proportion of amuletic jewellery in precious metals such as silver or gold, in contrast with the more common base metal objects found in England (Table 4.3). Of the thirty metal objects with sacred inscriptions that have been reported as Treasure Trove, nineteen are silver, three are gold and eight are base metals. For example, two heart-shaped silver brooches (dated c.1300) from Kirkcaldy (Fife) and Dalswinton (Dumfries and Galloway) (Figure 4.4) have the inscription IHESUS NAZARENUS (Treasure Trove in Scotland 2012/2013: 8). The heart shape may denote a romantic gift but the form and material may also be apotropaic. Silver was regarded in Scotland as powerful protection for newborns and heart-shaped pins were attached to children’s clothing to guard against evil (Maxwell-Stuart Reference Maxwell-Stuart2001: 16; Miller Reference Miller2004: 28). Sacred inscriptions occur on other types of silver jewellery with romantic connotations, such as fede rings, showing two clasped hands. A silver gilt example found within the scheduled area of Inchaffray Abbey has an inscription abbreviating Jesus Nazarenus (Treasure Trove in Scotland 2002/2009: 16). Fede rings with sacred inscriptions seem particularly well represented among the Scottish material, with nine in silver and three in copper alloy out of a total of sixteen recorded as Treasure Trove (75 per cent). Comparison with the English material emphasises the significance of this pattern (Table 4.4). Of sixty-seven medieval fede rings found in England and registered with the Portable Antiquities Scheme, only eight bear sacred inscriptions (all silver) (12 per cent). Fede rings (meaning faith) originated with the ancient Roman and Byzantine tradition for marriage rings that show a pair of clasped hands, perhaps referencing the Roman custom of concluding the marriage contract with a handshake (Hindman et al. Reference Hindman, Fatone and Laurent-di Mantova2007: 136).

Table 4.4 Fede rings with sacred inscriptions (as of 9 Jan. 2017)

| Nazarenus/INRI | Iesus | Unknown | Total no of fede rings in database | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAS | 2 (silver) | 1 (silver) | 5 (silver) | 67 (61 silver, 4 Cu A, 1 gold, 1 lead alloy) |

| Scottish TT/Canmore | 7 (6 silver, 1 Cu A) | 3 (1 silver, 2 Cu A) | 3 (silver) | 16 (12 Silver/silver gilt, 4 Cu A) |

‘Placed Deposits’: The Incorporation of Objects

Prehistorians generally agree that people in the past deliberately ‘deposited’ objects in acts of ritual practice that were integrated with aspects of everyday life, such as the burial of selected materials at critical points in settlements, at boundaries, entrances or the corners of houses (Brück Reference Brück1999; Garrow Reference Garrow2012; see Chapter 1). Medieval archaeologists are becoming increasingly alert to ritual deposits made in secular contexts – for example, the Bronze Age flints deposited in the medieval hall excavated at High Street, Perth (noted above; Hall Reference Hall2011). But we have been slow to recognise deliberately ‘placed’ deposits made in medieval religious contexts, including parish and monastic churches.

An excellent example is the church at Barhobble, Mochrum (Dumfries and Galloway), where excavations uncovered a lost church built in the twelfth century on the site of an earlier church and cemetery, possibly monastic in origin (Cormack Reference Cormack1995) (Figure 4.5). The church went out of use after the thirteenth century; despite problems with dating, the placed deposits can be dated to the twelfth or thirteenth centuries. Several objects were recorded in association with the altar: an iron bell, a stone cross fragment, a kaolinite (lithomarge) disc and an iron padlock. Further objects were found in the area of the rood screen that separated the nave and chancel: a handful of sea shells, two further stone cross fragments and three coins. Two coins were also found together in a void against the south wall, and a lump of jasper and a copper alloy bolt for a padlock were found under the baked clay floor in the southwest corner. A western compartment, interpreted as possible priests’ quarters, yielded further finds: a fragment of stone cross and a haematite burnisher. Of particular interest is a lump of decorated iron mail and mineralised textile, found deposited against the north wall of the structure near the northwest corner, within a V-shaped stone setting sunk into the clay floor. The textile was interpreted as a coif or headpiece with a linen cap, placed inside a grass bag.

4.5 Location of ‘placed deposits’ inside Barhobble Church (Dumfries and Galloway).

The Barhobble deposits can be compared with those found in a number of early medieval churches where excavations have identified special objects associated with altars and screens. At Whithorn (Dumfries and Galloway), the church of the Northumbrian minster was ‘deconsecrated’ in the ninth century (c.835 CE). It was stripped of its ecclesiastical fittings and briefly used for secular purposes before it was destroyed by fire. A group of distinctive objects was found in association with the demolished altar at the eastern end of the chancel (Figure 4.6), including a sherd of Gaulish Samian pottery, a rock crystal and a Roman coin dating to the fourth century. Possible ecclesiastical artefacts were found at the eastern end of the nave, near the location of the chancel screen: a copper fragment with a cross motif and silver inlay and the possible handle of a spoon. Several flints were also recovered from the floor of the church (Hill Reference Hill1997: 162–4). The Whithorn evidence may be compared to the Anglo-Saxon church at Raunds Furnells (Northamptonshire), where a Roman coin and prehistoric lithics were deposited in the chancel that was added to the church in the mid-tenth century (Boddington Reference Boddington1996).

4.6 Location of ‘placed deposits’ inside the 9th-century church (c.835) at Whithorn (Dumfries and Galloway).

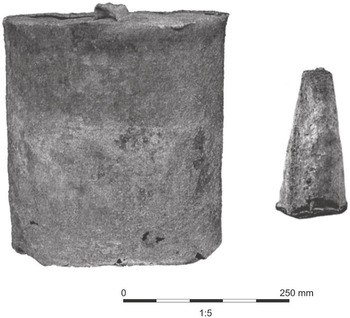

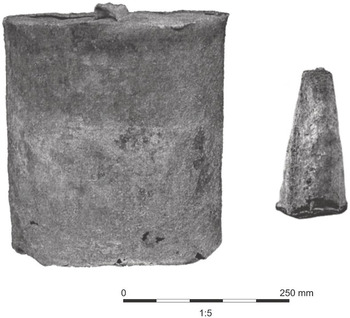

At Glasgow Cathedral, two bronze mortars and an iron pestle were buried in the northwest corner of the Lady Chapel crypt, just east of the shrine of St Mungo, below the cathedral choir (Figures 4.7 and 4.8). The mortars were dated respectively to the late thirteenth/early fourteenth century and to the late fourteenth/early fifteenth century, while the pestle was later, dated to the sixteenth century (Driscoll Reference Driscoll2002: 60). The mortars were placed on their sides in a pit, which appears to have been dug and filled in a single event, suggesting that it was dug specifically to contain the mortars. The mortars were well worn and several hundred years old when they were buried, explained by the excavator as a possible act of ritual concealment at the Reformation, located in the most sacred space of the cathedral (Driscoll Reference Driscoll2002: 118). Similar cases have come to light at Cistercian abbeys in England, where the deliberate burial of religious sculptures has been interpreted as acts of concealment prior to the Dissolution (Carter Reference Carter2015a).

4.7 Medieval bronze mortars and iron pestle found buried in Glasgow Cathedral.

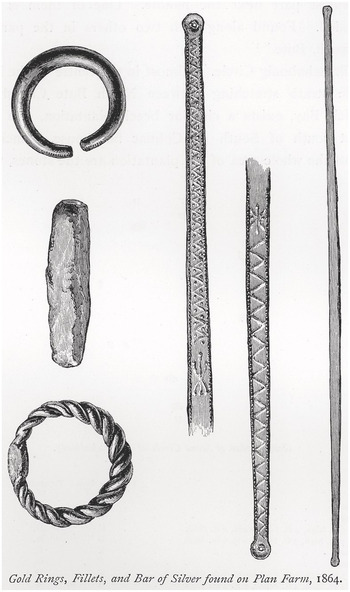

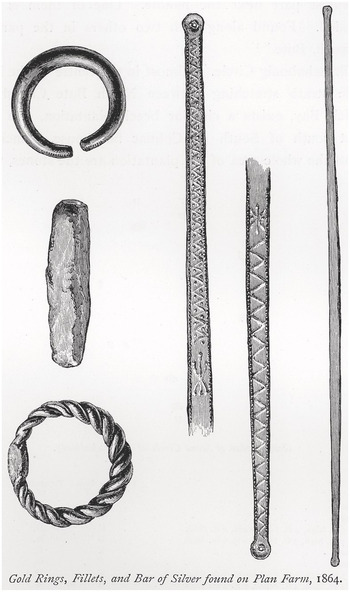

In the nunnery church at Iona, a group of four silver spoons and a gold fillet from a headdress were found in 1923, wrapped in linen and placed beneath a stone at the base of the chancel arch (Curle Reference Curle1924) (Figure 4.9). Stylistically the spoons are dated c.1150 and the hair-fillet is thirteenth-century (Zarnecki Reference Zarnecki1984: 280). The date of the deposit is unknown: the nunnery was founded in 1203, half a century after the spoons were made. A second deposit was buried in the chapel of St Ronan nearby, comprising a gold finger-ring and another gold fillet, with the fillet tightly folded up within the circumference of the ring and kept in position by a fragment of wire (Curle Reference Curle1924) (Figure 4.9). When they were found, the examples from Iona were described as hoards, or perhaps as a thief’s booty concealed for later retrieval. The Iona deposits can be compared with hoards from the site of St Blane’s church on Bute (Argyll and Bute), found by workmen in 1863 (Figure 4.10). The deposit comprised two gold rings, three gold fillets and a small bar of silver, as well as twenty-seven coins associated with the Scottish kings David I and Malcolm IV, and the English kings Henry I and Stephen (Thompson Reference Thompson1956: 21). The date of deposit is unknown: the coin dates suggest some time after c.1150. The church of St Blane retains architectural evidence dating from the twelfth century onwards, but there are associated monastic remains possibly dating from the sixth or seventh centuries (Radford Reference Radford and Ashe1968). Part of the cemetery at St Blane’s is known locally as having served as a women’s burial ground (Canmore ID 40292), comparable to the nunnery at Iona. Although rings and fillets were found together at both sites, the Blane deposit is more obviously a hoard. It includes a silver ingot and a large number of coins and it was buried extramurally, in contrast with the Iona deposits, which were deposited within the sacred space of consecrated buildings.

4.9 Objects buried in two separate deposits in the church and chapel of Iona Nunnery (Scottish Inner Hebrides), including silver spoons and two gold fillets.

Objects deliberately buried in sacred contexts are often explained as hoards or precious artefacts concealed for protection at times of peril; such threats ranged from local military raids to the massive upheaval of the Reformation. At Glasgow and Iona, the objects deposited were of considerable age at the time of burial, echoing the use of Roman and prehistoric artefacts in early medieval churches such as Whithorn and Raunds. These objects were placed at important liturgical points and they were items that possessed ritual associations. The bronze mortars from Glasgow are likely to have been liturgical objects, used for preparing incense burnt during the celebration of the Eucharist and other sacraments; mortars were also used for mixing medical or magical recipes and for alchemical experiments. The objects from Iona resonate with Christian life course rituals: the headdress fillets are the type worn by brides; spoons were given for marriage and baptism gifts; and the gold ring may be a wedding band (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012: 94–5, 125–6). The Iona deposits may have been connected with individual life histories, perhaps even family heirlooms buried by a nun or widow entering the convent. The placed deposits at Barhobble combine liturgical objects such as the bell and stone crosses, with traditional amulets such as coins and seashells, while the chain mail coif may suggest the commemoration of a warrior. These examples confirm that special deposits were placed in Scottish churches dating from the ninth century right up to the Reformation.

Intentional deposits made in sacred contexts may be regarded as ritual performances: these material practices involved objects that held particular relevance to the collective life of the religious community, or perhaps to individual life histories. Some of the artefacts that were deliberately placed would have been highly revered spiritual objects. The spectacular Pictish shrine chest known as the St Andrews Sarcophagus is believed to have been deliberately buried to the southeast of St Andrews Cathedral (Fife), where its fragments were discovered in the nineteenth century (Figure 4.11). It has been suggested that its burial may have taken place prior to the twelfth century, perhaps when the eighth-century container was deemed redundant and the relics were transferred to a new receptacle (Foster Reference Foster and Foster1998: 46). There are similarities with the recently discovered bas-relief panel of an angel in Lichfield Cathedral (Staffordshire). This is dated c.800 and interpreted as part of the shrine chest of St Chad, believed to have been broken and buried in or before the tenth century (Rodwell et al. Reference Rodwell, Hawkes, Howe and Cramp2008: 58–60). After prolonged physical contact with the relics of a saint, shrine chests would have been regarded as sacred objects, quasi-relics in their own right. There is some evidence that medieval monasteries may have extended this ritual treatment to sculptures that were particularly valued by the community. At the Benedictine Abbey of St Mary’s, York, a set of life-size column-figures dating to the late twelfth century were discovered in 1829 in the nave of the former abbey church, carefully laid in a row with their faces down. The statues are likely to have come from a western portal of the Romanesque church and were carefully dismantled and interred during works to extend the Gothic church (Norton Reference Norton1994: 275–8).

If a decision was made to replace a shrine or reliquary, care was needed in the disposal of the redundant object. A useful comparison can be made with disposal practices associated with materials that had become consecrated through their use in the sacraments. Strict rules governed the disposal of consecrated materials, ranging from the Eucharistic wafer and wine, to mass vessels and vestments, and the chrism cloth worn by baptised infants (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2012: 180–1). The careful disposal of disused medieval fonts illuminates this process, discussed by David Stocker (Stocker Reference Stocker1997). Fonts were not consecrated per se, but through prolonged physical contact with hallowed water, they acquired the status of sacred objects. It seems to have been common medieval practice to bury an old font beneath or near its successor in the nave of the church, with forty examples documented in England. Similar practices are observed in Scotland: nine examples of buried fonts include part of the rim of a decorated stone basin found under the ruins of the east end of the chapel at Loch Finlaggan (Islay – Argyll and Bute) in 1830 (Canmore ID 76281). Three disused fonts were deposited in watery locations (Canmore IDs 1765, 64298, 239026); four were reused in boundary walls (Canmore IDs 12254, 26165, 60040 and 97573); two were found in burial grounds (Camore IDs 4056 and 67206); and one was found deposited inside a cairn said to mark the site where St Kessog was martyred in Luss (Argyll and Bute, Canmore ID 42548). In common with vessels and textiles that had been used in the sacraments, it was essential to dispose of fonts in a way which prevented their reuse for profane purposes, for instance in illicit magic. The burial of shrine fragments at Lichfield and St Andrews may have been based on similar principles – the desire to remove sacred objects from circulation for safe-keeping, while at the same time reincorporating them within the religious community. This act can be likened to human rites of passage, classically framed by the anthropologist Arnold van Gennep as a three-fold process involving separation, transition and reincorporation (van Gennep Reference van Gennep, Vizedom and Caffee1960 [1909]). Seen in this context, the deliberate burial of objects in churches is consistent with Christian cosmology and ideas about sacred space, as well as the ritual treatment of both consecrated materials and the remains of the Christian dead.

Parallels can also be drawn between the burial of objects and people in sacred space and the incorporation of human remains within church fabric. For example, the church excavated at Barhobble had human bones incorporated into the altar built against the east wall, contained within the clay bonding of the structure of split stone slabs. The human remains comprised fifty fragments including the cranium, femur and tibia. It was originally proposed by the excavator that these were the relics of the sixth-century St Finian of Movilla (Cormack Reference Cormack1995: 15) but radiocarbon dating subsequently confirmed that the bones date to the mid-thirteenth century (Oram Reference Oram2009). Incised stones were also incorporated in the fabric of the church at Barhobble: a small cross slab was built into the south doorway; a worn stone with possible graffito served as the doorstep. A paving slab incised with the gaming board for merrils was found in the balk between the two doorways and may have been built into the south wall. At Finlaggan on Islay, a bent coin of David II/Robert III was incorporated in the mortar of the southeast corner of the chapel (Hall Reference Hall, Haselgrove and Krmnicek2016a: 149). Similar practices are seen in monastic contexts. At the nunnery of Elcho, one section of walling of the church reused a slab with cup and ring marks on its upper surface, likely dating to the Bronze Age; and human remains were deposited within a hollowed-out cavity in the wall (Reid and Lye Reference Reid and Lye1988: 54–5). Insertion into church fabric was one method of reincorporating the bones of saints or earlier monastics within the community; this practice can be viewed as part of the cult of relics, and is also consistent with longstanding traditions of ritual deposition.

Fragments of disarticulated human bone were also buried in caskets and canisters, particularly where burials had been ‘translated’, in other words, moved from another site or deliberately disturbed and reinterred when churches were rebuilt (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 197–9). This practice is well-documented at Melrose Abbey (Scottish Borders), where three lead canisters containing body parts were recovered from the area of the east range (Ewart et al. Reference Ewart, Gallagher and Sherman2009) (Figure 4.12). Two were excavated in the chapter house, which was the favoured place of burial for abbots (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 59). The Melrose chapter house also featured a pit near the abbot’s seat, lined with a bed of charcoal; the pit was empty when excavated, but it has been suggested that it originally held translated human remains. These are likely to have been the bones of abbots buried in the chapter house and disturbed when it was extended in the thirteenth century. These mortuary practices belong to the mainstream repertoire of monastic death rituals and are also consistent with the tradition of placed deposits. Translated burials underwent an explicit sequence of separation, transition and reincorporation.

Coins were also employed as placed deposits in churches, either singly or in hoards, such as a deposit in the crossing of Glasgow Cathedral of fifty-eight half-crowns and sixty-two crowns (Hall Reference Hall2012: 79). While coins are generally perceived as markers of financial transactions, they were also used for ritual purposes. Mark Hall has called for their study in terms of amuletic and ‘prayerful’ uses in spiritual transactions, while Lucia Travaini emphasises their significance for marking personal memory and recording chronology (Hall Reference Hall2012, Reference Hall, Haselgrove and Krmnicek2016a; Travaini Reference Travaini, Giles, Gaspar and Gullbekk2015). Hall argues that coins were widely regarded as amulets connected to the cult of the Rood, based on the pervasive imagery of the cross or crucifix on the reverse of medieval coins. Throughout Europe, coin deposits occur in monastic churches, domestic and industrial buildings, and burials. The use of coins in foundation deposits in French and Italian churches (Travaini Reference Travaini, Giles, Gaspar and Gullbekk2015: 218–20) can be compared with practices in Scotland. For example, a small vessel recovered from the foundations of the west front at Melrose Abbey contained a fifteenth-century denier of Charles VIII of France (14830–95) (Cruden Reference Cruden1952).

The incorporation of coins in building fabric is also common in Scotland. At Jedburgh Abbey (Scottish Borders), an Anglo-Saxon coin was found associated with a late medieval building (Lewis and Ewart Reference Lewis and Ewart1995), and at the Carmelite friary at Perth, a mid-thirteenth-century coin of Henry III was associated with the foundation of a building dated to the thirteenth–fourteenth century (Stones Reference Stones1989). At Blackfriars in Perth, jetons and a coin were placed in the construction trench of a cellar and boundary ditch (Hall Reference Hall2012). Two separate deposits were identified at Linlithgow Carmelite Friary: a groat of Robert II (1371–90) was found in the foundation trench of a building erected by 1430; and four coins were recovered from the chapter house (Stones Reference Stones1989). At Whithorn, a group of four coins of Edward I was deposited in an oven in the southern section of the outer zone of the cathedral priory. The latest coin is the most worn, indicating that the deposit was made in the early to mid-fourteenth century (Hill Reference Hill1997). Placed deposits in secular contexts have also been recorded in association with hearths and ovens, for example at High Street Perth, a Thomas Becket ampulla and scallop shell were associated with an oven (Hall Reference Hall2011: 95).

One aspect in which monastic and lay practices seem to have differed is in the deliberate deposition of pilgrim badges and ampullae. These were usually cheap, mass-produced objects in lead or tin alloy, sold at saints’ shrines. They are referred to in the archaeological literature as ‘pilgrim souvenirs’, perhaps conveying inappropriate parallels with modern tourism. The historian James Bugslag has recently suggested that they should instead be termed ‘pilgrim blessings’ (Bugslag Reference Bugslag, Bowers and Keyser2016: 261). Badges and other small metal objects were blessed at the saint’s shrine and acquired the status of quasi-relics or consecrated objects (Skemer Reference Skemer2006: 68). These objects were believed to trap the thaumaturgical (miraculous) power of the saint and their resting place, allowing the pilgrim to carry the healing essence of the saint away from the shrine. Ampullae were tiny containers that held water, oil or dust from shrines or holy wells, the most famous being ampullae from Canterbury associated with Thomas Becket, martyred in 1170. The monks of Canterbury Cathedral mixed Thomas’s blood with water and it was widely believed that local water held the saint’s healing power (Koopmans Reference Koopmans2016). Ampullae from Canterbury were inscribed ‘Thomas is the best doctor of the worthy sick’ (Spencer Reference Spencer1998: 38).

Pilgrim badges were worn as amulets on the body and used in the home, fixed to doors and bedposts or fastened to textual amulets and books of hours. Archaeological evidence confirms that they were also employed in largely undocumented rites of deliberate deposition in the landscape. Pilgrim badges have been found in large quantities in rivers in England, France and the Netherlands, with particular concentrations recovered at the locations of bridges and river crossings (Spencer Reference Spencer1998). New evidence from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) provides evidence for badges from rural contexts, which serves to complement the urban evidence derived from archaeological excavations. Well over 300 examples are reported in the PAS, 250 of which can be attributed to particular saints or shrines. The geographical distribution of these badges indicates that the majority are found close to the shrine where they originated (Lewis Reference Lewis, Bowers and Keyser2016: 277). This pattern suggests that acts of deposition may have been an integral part of the pilgrimage rite itself, possibly completed on the pilgrim’s return journey home. Some badges were purposefully destroyed and deposited in the landscape, perhaps as a thanks-offering to a saint for a cure or miracle, or as part of the performance of a charm.

In contrast, the distribution of ampullae recorded in the PAS suggests a very different pattern, based on over 600 recorded examples. It seems that these containers of holy water were sometimes taken home by the pilgrim and reserved for future ritual use. William Anderson has identified a pattern in which English ampullae dating to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were deliberately damaged before being discarded in cultivated fields (Anderson Reference Anderson2010). They were damaged by crimping or even biting, presumably to open the seal in order to pour the contents on the fields before discarding the vessel. Folded coins are also found especially in plough-soil, suggesting the possibility of a deliberate act of discard as an offering to protect or enhance the fertility of fields (Kelleher Reference Kelleher2012). Ceremonies for blessing the fields are recorded in which parish priests sprinkled holy water and recited the biblical passage of Genesis 1:28: ‘Then God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth”’ (Kieckhefer Reference Kieckhefer2000: 58).

The performance of magic frequently involved the modification or deliberate mutilation of objects, for example the bending of coins and pilgrim badges and the crimping of ampullae. This practice can be likened to the folding of charms written on parchment or lead: the act of folding increased the efficacy of the charm by preserving its secrecy and containing its magic (Olsan Reference Olsan2003: 62). The folding and discard of pilgrim souvenirs can also be compared with the deliberate destruction of magico-medical amulets, such as fever amulets thrown into the fire after the afflicted person had recovered (Skemer Reference Skemer2006: 188). The destruction of the amulet guaranteed that it was specific to the individual and could not be reused, while the act of folding or mutilation was also integral to the performance of magic. This premise is documented in relation to the practice of bending coins: miracles recorded at saints’ shrines refer to the custom of bending the coin in the name of the saint invoked to heal the sick person (Finucane Reference Finucane1977: 44–6). In a study of folded coins from archaeological contexts, Richard Kelleher noted their occurrence in both religious and secular contexts, ranging from urban and rural settlements to castles and monasteries. However, folded coins occur most commonly at religious sites, including the chapel at Finlaggan, Glastonbury Tor (Somerset) and the monasteries of Jarrow (Tyne and Wear), Battle Abbey (Sussex), St James’s Priory, Bristol, Whithorn and St Giles’s Cathedral Edinburgh (Kelleher Reference Kelleher, Burström and Ingvardson2018: 73).

In contrast, the deliberate deposition of pilgrim badges and ampullae seems to be a ritual practice associated exclusively with the laity. Very few pilgrim signs are found in monastic contexts, with rare examples reported from burials in monastic and hospital cemeteries, for example at Cistercian Hulton Abbey (Staffordshire) and the hospital of St Giles by Brompton Bridge in Yorkshire (Klemperer and Boothroyd Reference Klemperer and Boothroyd2004: 133; Cardwell Reference Cardwell1995; Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 96–8). There are also significant regional differences, with very few pilgrim badges and ampullae reported in Scotland (Shiels and Campbell Reference Shiels, Campbell, Cowan and Henderson2011: 84) or Wales (Locker and Lewis Reference Locker and Lewis2015: 60). Pilgrim souvenirs are completely undocumented for some major cult sites such as St Winefride of Holywell (Flintshire) and Glastonbury Abbey. It has been suggested that natural souvenirs may have been preferred over manufactured souvenirs at some cult centres, for example organic objects such as stones, shells and flowers (Locker and Lewis Reference Locker and Lewis2015: 59).

It is clear from archaeological evidence that pilgrim signs manufactured in metal were less common in Scotland. However, badges of St Andrew were made and circulated, confirmed by a stone mould for two St Andrew badges found in the churchyard of St Andrew’s at North Berwick, on the pilgrim route to St Andrews (Hall Reference Hall and Blick2007: 84–5). There are only eight examples of pilgrim signs reported as Treasure Trove on the Canmore database, in contrast with nearly 350 in the English PAS (Lewis Reference Lewis, Bowers and Keyser2016). This includes a rare example from Crail (Fife) of a lead pilgrim badge of St Andrew (Treasure Trove in Scotland 2008/2009: 15). Fewer than a dozen badges of this type are known, with the majority coming from the Thames foreshore in London. The evidence from Perth High Street demonstrates that pilgrim badges were used as placed deposits in secular contexts (Hall Reference Hall2011). The assemblage includes a badge of St Andrew and two Becket ampullae, both of which had been crumpled, as well as scallop shells, a common pilgrim sign of St James of Santiago de Compostela.

Personal objects of jewellery inscribed with sacred names may also have been selected for deliberate deposition. Eleanor Standley has drawn attention to two possible cases from northern England. Two silver brooches were discovered near the foundations of a bridge at the Premonstratensian abbey of Alnwick (Northumberland), both with Jesus Nazarenus inscriptions. At the village of West Hartburn (co Durham), a silver brooch inscribed with a Jesus Nazarenus inscription was recovered near a circular hearth within a structure (Standley Reference Standley2013: 82–3). This deposit combines several elements of meaningful ritual practice – deliberate burial, an amulet in precious metal with the Jesus Nazarenus inscription, and the selection of the hearth as a critical point for protection. The deliberate burial of amulets with sacred names raises the question of whether some of the apparently stray finds recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme and Scottish Treasure Trove may in fact be ritual deposits deliberately incorporated in the medieval landscape.

Burial: The Transformation of the Dead

Medieval burials were sometimes accompanied by the same objects and materials that were used as amulets and placed as ritual deposits. Both monastic and lay funerary rituals employed objects associated with healing and protective magic; however, some significant differences are apparent between the two traditions. What was the purpose of magic for the dead: who placed these objects with the corpse and for what reasons? To understand the possible meanings behind these rites, we must appreciate the importance that medieval Christians placed on the material continuity of the body for its resurrection at Judgement Day. In 1215, the doctrine of literal resurrection was confirmed by the 4th Lateran Council: ‘all rise again with their own individual bodies, that is, the bodies which they now wear’ (Bynum Reference Bynum and Bynum1991: 240). In confronting death, medieval people were highly anxious about the body and theologians debated the relationship between the corpse and the resurrected person. How was the soul in purgatory affected by the state of the corpse in the grave? Was individual identity retained, when dry bones had been reconstituted and resurrected as whole bodies at Judgement Day (Bynum Reference Bynum and Bynum1991: 254)?

Monastic burial rites emphasised the religious identity of the deceased: clothing and grave goods were used to denote the consecrated status of their bodies and to distinguish them from those of the laity – in life, death and resurrection. Bishops, abbots and abbesses were buried with their croziers, the pastoral staves that were symbolic of their office. Priests were interred with signs of their clerical office: metal, ceramic or wax copies of the chalice and paten, the vessels used to celebrate the mass; while nuns went to the grave in their headdresses, signifying their role as brides of Christ (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 81–3, 160–5, 225). It was common to dress religious corpses in their monastic habits and possibly their robes of religious consecration: this clothing did not merely represent the status of the deceased, it was intended to protect the physical body of the corpse on its journey through purgatory (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist, Prusac and Brandt2015).

A high proportion of the textiles and objects placed with the medieval dead have perished in the soil. Occasionally, however, ecclesiastical tombs illustrate the richness of medieval funerary rites. For example, excavations by Roy Ritchie at Whithorn in the 1950s and 1960s uncovered a group of ecclesiastical burials near the high altar of the cathedral priory (see Figures 6.1 and 6.2). Their re-examination and publication in 2009 included radiocarbon dating and scientific analysis of skeletons and artefacts (Lowe Reference Lowe2009). It was concluded that the burials dated principally to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and represented a group of three bishops, five to six priests and four to five lay benefactors, including two possible husband and wife pairs (Lowe Reference Lowe2009: 172). The grave goods from six burials contained textiles and ecclesiastical metalwork of outstanding importance, including the exceptional Whithorn Crozier, a copper-alloy, champlevé enamel crozier crafted in the second half of the twelfth century. The Whithorn grave goods included silver and silver-gilt sets of chalices and patens, as well as pewter examples, and gold and silver finger rings with gems of sapphire, amethyst, emerald and ruby, all highly valued for their occult properties. According to medieval lapidaries, the blue sapphire soothed fevers and pains; the purple amethyst supported wisdom and guarded against evil; the green emerald increased wealth; and the red ruby promoted health and protected against poisons (Evans Reference Evans1922). Textile remains from Whithorn included gold braid, which was combined with spangles and glass beads in highly decorative liturgical vestments. Dress accessories included ring buckles, confirming that some burials were fully clothed. The clothed burials were interred in three stone cists, while the burials in wooden coffins had grave goods but no dress accessories, indicating their interment in shrouds (Lowe Reference Lowe2009: 105).

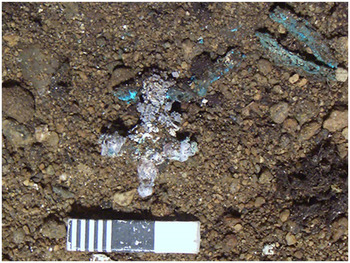

The majority of graves in medieval monastic and parish cemeteries would have been simple shroud burials, unaccompanied by objects. However, recent excavations have revealed new evidence for the use of clothing and grave goods in medieval Scottish burials (Figures 4.13 and 4.14). Many of these inclusions were organic and would typically fail to survive in the soil, while others may be overlooked by archaeologists as natural materials or residual objects in grave soils. Some of the most recently excavated sites have yet to be analysed fully, including nearly 500 medieval burials from the East Kirk of St Nicholas Aberdeen, dating from the eleventh to fifteenth centuries, and Perth Carmelite Friary, where excavations by Derek Hall recorded nearly 300 new burials, dating from the thirteenth century up to and beyond the Reformation (Cameron and Stones Reference Cameron, Stones and Geddes2016; Derek Hall pers. comm.). Lay cemeteries excavated at Barhobble, The Hirsel (Coldstream) and Auldhame (East Lothian) provide useful comparisons. The proprietary church at The Hirsel developed from around the tenth century, with the cemetery established from the twelfth century (Cramp Reference Cramp2014). Auldhame has been interpreted as a monastic settlement occupied from the seventh to ninth centuries, with the site later serving intermittently as a parish church and graveyard until at least the sixteenth century (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016).

Lay burials at the East Kirk of St Nicholas Aberdeen included clothing or textiles associated with burials dating to the eleventh or twelfth century, including possible hair cloth, as well as grave goods such as coins and a lead alloy cross on a chain (Cameron and Stones Reference Cameron, Stones and Geddes2016: 87) (Figure 4.14). At Auldhame, a grave contained a buckle with textile still adhering to it, suggesting that the corpse was interred fully clothed (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016: 73). Clothed burials at the Carmelite friary at Perth were evidenced by the survival of leather shoes, while possible wax objects may represent skeumorphs of croziers or similar religious symbols (Figure 4.13). Graves excavated in the chapter house at Jedburgh Abbey confirm that a group of canons was given elaborate burial in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, including clothing represented by buckles and fragments of embroidered silk, as well as leather shoes (Lewis and Ewart Reference Lewis and Ewart1995: 121, 124). St Nicholas Aberdeen and the Perth Carmelites also produced evidence for the placement of wooden staffs, rods or twigs next to the body, a funerary rite well known in England, Scandinavia, France and Germany.

More than twenty examples of wooden rods have been recorded at Carmelite Perth (Derek Hall, pers. comm.) (Figure 4.15). This rite was practised in Britain from the eleventh century up to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in both monastic and parish cemeteries; the largest comparable groups include eighteen staffs or rods from Glastonbury Abbey, twelve from Hull Augustinian Friary (East Yorkshire) and nine from Hulton Abbey (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 126, 171–4). The rods were usually made from coppiced hazel, ash or willow; the lack of wear and their insubstantial nature suggest that they were items made especially for burial. It has often been suggested that they represent a link with pilgrimage or journeying, or that the quick-growing coppices used for the poles symbolised the Resurrection and eternal life. Alternatively, they may have been objects used in Christian charms (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2008). In Scandinavia, the placement of burial rods in graves also develops from the eleventh century onwards and the rite has been interpreted as amuletic. Kristina Jonsson argues that the rods were used to measure corpses for magical purposes, perhaps connected with healing charms (Jonsson Reference Jonsson2009: 115).

Coins were placed with the dead at both the East Kirk of St Nicholas Aberdeen and Perth Carmelite Friary. Coins are perhaps the most common amulet placed with the monastic dead in Scotland and numerous examples are also recorded from English monastic cemeteries (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 100). They were present in later medieval burials at Whithorn Cathedral Priory, St Giles’s Cathedral Edinburgh, Jedburgh Abbey, Holyrood Abbey Edinburgh, Perth Dominican Friary, Perth Carmelite Friary and Elcho Nunnery (Lowe Reference Lowe2009; Collard et al. Reference Collard, Lawson and Holmes2006; Lewis and Ewart Reference Lewis and Ewart1995; Bain Reference Bain1998; Hall Reference Hall2012; Hall Reference Hall, Haselgrove and Krmnicek2016a). There is also evidence for the use of occult materials as grave goods in Scottish monastic cemeteries: a female at Perth Carmelite Friary was buried with a necklace of jet and glass beads (Derek Hall, pers. comm.) (Figure 4.1) . The tradition of placing quartz pebbles in graves was maintained in some later medieval cemeteries in Scotland. At Inchmarnock (Argyll and Bute), ten graves with quartz pebbles were excavated, eight of which are considered to date after the twelfth century (Lowe Reference Lowe2008: 268). At Barhobble, graves dating to the eleventh and twelfth centuries contained quartz pebbles, with individual graves containing between one and twenty pebbles (Cormack Reference Cormack1995: 35). Quartz pebbles were observed in the majority of grave fills at Auldhame and a cist burial near the chapel contained quartz pebbles, shells and a possible gaming piece; the adult skeleton was radiocarbon dated to the eleventh or twelfth centuries (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016: 21, 24, 91). Four graves at The Hirsel were associated with quartz pebbles: one located to the southwest of the church contained five quartz pebbles and a coin. This female burial had a folded coin placed in the mouth or near the chin: the coin was of William I (the Lion, 1165–1214) and stratigraphically the grave is consistent with a late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century date (Cramp Reference Cramp2014: 90). Another quartz pebble was found with a child’s burial to the north of the church, which also contained an animal tooth, and was covered by large stones and an upright grave-marker (Cramp Reference Cramp2014: 93). Quartz pebbles placed in combination with a folded coin or animal tooth strongly suggest an apotropaic rite. Other types of pebble were also used as grave goods in nine cases at The Hirsel (Cramp Reference Cramp2014: 300), and at the Dominican Friary at Aberdeen, two older males were buried with large stones inserted in their mouths (Cameron Reference Cameron2016).

A number of graves from Barhobble included antique or exotic objects placed with the dead. For example, a child’s grave had a piece of green porphyry placed at the head, a highly decorative, igneous rock that would have come from Greece. Another grave contained a fragment of Romano-British glass bangle (Cormack Reference Cormack1995: 36). Roman objects have been found in a number of later medieval graves in England, including a glass bangle from the parish church of Wharram Percy (North Yorkshire), a shale bracelet from St James’s Priory, Bristol, and a copper-alloy bracelet from St Oswald’s Priory, Gloucester (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2008; Heighway and Bryant Reference Heighway and Bryant1999; Jackson Reference Jackson2006). The later medieval burial of a female at Perth Carmelite Friary contained a fragment of Samian pottery (Stones Reference Stones1989) and Samian sherds were also deposited in medieval graves at Whithorn (Hill Reference Hill1997: 296). The practice of placing ‘old objects’ in graves is part of an ancient tradition of using ‘found objects’ (objets trouvés) for healing and protection. Audrey Meaney first identified the magical use of Roman and prehistoric objects in Anglo-Saxon graves (Meaney Reference Meaney1981). This practice continued into the later medieval period, with Roman tiles, pottery, coins and bracelets occasionally buried with the medieval dead (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2008; Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005).

Lay burials at Barhobble and The Hirsel also included iron objects in graves, a traditional rite which is not seen in later medieval monastic cemeteries in Scotland. At The Hirsel, an iron object was placed between the teeth of an individual buried to the north of the church (Cramp Reference Cramp2014: 103). At Barhobble, there were at least five examples of iron objects included with burials of children and adults. One of these was a knife, an object that was also associated with burials at Whithorn and Auldhame, noteworthy because knives and tools in general are rarely found as grave goods with medieval burials (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016: 82). A remarkable case is an adult female in the nave of the church at Barhobble, located close to the entrance to the chancel, in a grave carefully constructed with side slabs and a cover stone. A pair of iron shears was placed over the woman’s feet and she was surrounded by the graves of infants. The orientation of this group of burials is consistent with the twelfth-century phase of the church (Cormack Reference Cormack1995: 38). Scottish folklore suggests that iron objects were considered to provide protection from malevolent forces (Houlbrook Reference Houlbrook, Houlbrook and Armitage2015: 132), but these sources date considerably later than the funerary rites discussed here. Shears were the most common female symbol in the Middle Ages, believed to represent the woman’s role as keeper of the house. They were used as a standard emblem to represent women on cross slab monuments dating from the twelfth century onwards (McClain Reference McClain, Badham and Oosterwijk2010: 46). Domestic shears were used for textile working but could have many other uses, perhaps even medical applications. Midwives used knives, scissors or small shears to cut the umbilical cord and these tools were sometimes used in medieval art to symbolise the midwife (Greilsammer Reference Greilsammer1991: 290–1). The context of the grave at Barhobble may suggest the burial of a midwife or female healer, placed in a strategic position in the church, perhaps to provide protection to the infant graves with which it was associated.

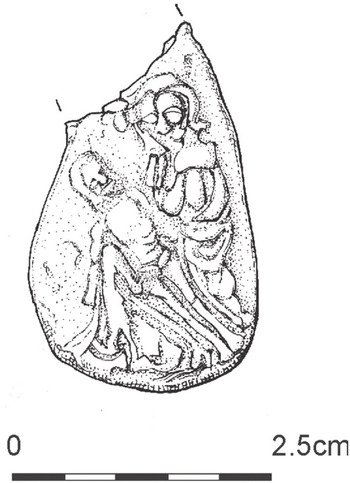

Another gendered artefact was placed with a late medieval female buried in the cemetery at Coldingham (Scottish Borders) (Stronach Reference Stronach2005). This grave contained a lead spindle whorl decorated with a star motif. Spindle whorls were associated with textile working, which in rural, domestic contexts was a craft generally associated with women. Spindle whorls were occasionally placed in the graves of medieval men, women and children in England, Ireland and Scandinavia. Eleanor Standley argues that decorated lead spindle whorls such as the one from Coldingham were symbolic of the Virgin Mary and her association with spinning the thread of the life of Christ. In a burial context, the spindle whorl holds many potential symbolic meanings: a devotional object, a gendered artefact and a symbol of the thread of life being cut short (Standley Reference Standley2016). A grave at Aberdeen contained an explicit Marian object: an elderly woman was buried in the fifteenth century with a badge depicting the Pietà, the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ (Figure 4.16).

A number of medieval Scottish graves contained scallop shells, a popular organic pilgrim souvenir. The most dramatic is from the Isle of May: a young male in his 20s was buried near the high altar in the church, between the late thirteenth and mid-fifteenth century. Shortly after death, his mouth was wedged open with a sheep scapula and a scallop shell was placed in the palate (James and Yeoman Reference James and Yeoman2008) (Figure 4.17). A perforated scallop shell was found near the head of a male burial at The Hirsel, aged 35–45 years old, and radiocarbon dated to cal AD 1260–1455 with peak in the fourteenth century (Cramp Reference Cramp2014: 106). Two burials from the East Kirk of St Nicholas Aberdeen included scallop shells: one had two scallop shells placed near the head; the other had a scallop shell placed on the thigh (Cameron and Stones Reference Cameron, Stones and Geddes2016: 87) (Figure 4.18). The shells may have been pinned to a pilgrim’s hat and pouch, which no longer survive. The scallop shell is a pilgrim sign symbolic of St James of Santiago de Compostela but is also found at early medieval Celtic shrine sites such as Illaunloughan Island (co Kerry) (White Marshall and Walsh Reference White Marshall and Walsh2005). Scallop shell badges may have been made in Scotland: an iron mould in the form of a scallop shell was found at Roseisle (Moray) and a scallop shell badge was found at Crail by metal-detectorists (Canmore IDs 33911, 215285). There was a strong later medieval connection between St James and the Scottish royal family: James was patron saint of five successive kings between 1394 and 1542 (Glenn Reference Glenn2003: 87). However, the scallop shell seems to have had more enduring significance as a pilgrim sign in Scotland: rather than expressing a specific connection to St James it may have carried resonances of earlier Celtic beliefs, comparable to quartz pebbles.

4.18 Skeleton buried with a scallop shell beside the left leg from East Kirk of St Nicholas, Aberdeen.

Many of these objects were placed in intimate contact with the corpse – on the body or even in the mouth. They must have been placed within the shroud when the body was washed and prepared before burial. In the case of a monastic burial, such preparations would have been completed by the monastic infirmarer; in a lay context, women of the family or perhaps a midwife would have carried them out, as depicted in contemporary Books of Hours (Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 23). Why were certain individuals marked out for special rites at death? In some of the cases discussed here, palaeopathological evidence suggests that the individuals experienced impeded mobility. The woman buried with the Pietà badge at Aberdeen suffered from severe osteomalacia (adult rickets) (Cameron and Stones Reference Cameron, Stones and Geddes2016), and the woman from Coldingham buried with a spindle whorl had bowed legs and signs of deterioration in her cervical vertebrae (Stronach Reference Stronach2005). The man buried with a scallop shell at The Hirsel had a bony tumour in his lower leg (osteochondroma of proximal tibio-fibular joint) (Cramp Reference Cramp2014).

Infants and children were also singled out for special treatment, both through the use of amulets and in the siting of graves. For example, at St Ninian’s Isle (Shetland) in the tenth century, infants were buried in a series of stone compartments created by upright stones and then filled with stones and quartz pebbles. One of these infants was buried with a small water-worn, quartz beach pebble placed in its mouth (Barrowman Reference Barrowman2011). At Auldhame, the burials of infants and neonates were clustered along the south walls of the building complex, with continuity demonstrated from the mid-seventh century up to the mid-twelfth century. Juveniles at Auldhame were buried at the western extreme of the site, with regularity in layout and orientation across 400 years (Crone et al. Reference Crone, Hindmarch and Woolf2016: 31). At the East Kirk of St Nicholas Aberdeen, child burials were placed in a radiating arrangement around the exterior of the apse in the eleventh or twelfth century (Cameron and Stones Reference Cameron, Stones and Geddes2016: 82). Children’s burials had amulets placed with them at Barhobble and The Hirsel, including quartz pebbles, an animal tooth and a fragment of exotic porphyry. Children were also given special treatment in monastic cemeteries: at Linlithgow Carmelite Friary, only ten burials contained objects out of 207 excavated, and nine of these belonged to children or young adults. The objects included lace ends, wire twists, a copper-alloy ring and a strap end associated with a belt (Standley Reference Standley2013: 105; Stones Reference Stones1989). At St Giles’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, a juvenile was buried in the fifteenth century with a folded coin and a pendant (Collard et al. Reference Collard, Lawson and Holmes2006).

The placement of amulets with the dead may have been intended to guard or protect loved ones from the perils of purgatory, serving as the material equivalent of prayers and masses to protect their souls. It was noted in the previous chapter that therapeutic devices were occasionally placed in the grave, ranging from healing plates to support joint injuries, to hernia trusses (see Chapter 3; Gilchrist and Sloane Reference Gilchrist and Sloane2005: 103–4). The presence of these therapeutic items in the grave strengthens the argument that the intention was to heal the corpse, just as the bodies of saints were known to heal in the tomb (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist2008). Amulets were placed with men, women and children, a small number of whom showed skeletal evidence of impaired mobility. Is it possible that mourners placed healing and apotropaic objects with the dead to provide both spiritual protection and physical assistance during the arduous journey through purgatory?

Silent Witnesses: Magic, Agency and the Life Course

Both monastic and lay communities in medieval Scotland engaged in the ritual technologies explored in this chapter, confirming that some elements of ‘folk religion’ spanned the boundary that is often perceived between ‘institutional’ (orthodox) and ‘popular’ (heterodox) religion. All three rites involved deliberate acts of the body that followed established norms, ranging from the use of amulets, to the deliberate burial or deposition of objects in sacred space, and the placing of objects with the medieval dead. Their perceived efficacy relied on the interaction between objects, materials, spaces and bodily techniques. While monastic and lay communities drew upon a common repertoire of ritual acts, some significant differences can also be discerned, such as the greater range of objects placed with lay burials, the special treatment of children in lay cemeteries and the possible ritual deposition of pilgrim souvenirs by the laity.

Chronological patterns are also evident, with greater diversity in burial practices in the earlier part of the period discussed here, the eleventh to twelfth centuries. This coincides with a time of massive political and religious change in Scotland, including the introduction of reformed monasticism and the formalisation of local churches into parishes (see Chapter 2). During this period of major social change, hybrid practices flourished, with older traditions of folk religion reinterpreted and persisting alongside orthodox rites. Placed deposits are evident in monastic and parish churches in Scotland ranging chronologically from the ninth to the sixteenth centuries, including personal possessions and liturgical items, as well as continuing the indigenous tradition of depositing prehistoric lithics, Roman artefacts and quartz pebbles. A number of regional patterns are apparent in the use of amulets when comparison is made with England. For example, the association of sacred inscriptions with precious metals seems to be a distinctively Scottish regional pattern, together with the strong preference for Jesus Nazarenus inscriptions over dedications to the Virgin Mary. The frequency of the romantic fede symbol, in combination with Jesus Nazarenus inscriptions, may denote a Scottish betrothal or marriage custom, to protect the union by continually invoking the sacred name. Pilgrim signs are less common in Scotland, but badges of St Andrew were manufactured and scallop shells appear to have been widely adopted as a symbol of St James, or perhaps as an enduring symbol of Celtic pilgrimage traditions.