Introduction

Some political scientists have proposed that easy-to-apply cues (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Popkin, Reference Popkin1991; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Lupia, Reference Lupia1994) may allow people to compensate for their well-documented lack of political expertise (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996). However, critics have questioned the ease of cue use, arguing that the application of cues requires contextual knowledge (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Kuklinski and Quirk, Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000). There is a debate, therefore, between those who believe that the typical citizen can use cues – especially party cues – to make accurate judgments, and those who think that the use of cues may be beyond the capabilities of the average voter.

However, this debate has been intractable because there is an unresolved normative debate lurking in the background. To illustrate, consider Kuklinski and Quirk's (Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000) critique of the view that typical voters can use cues, which argued that ‘to make their case, [proponents of this view] need to show, first, that most citizens routinely use particular heuristics in particular situations and, second, that the use of those heuristics leads to good or at least reasonable decisions’ (pp. 155–156). We believe that these elements are still lacking in the heuristics literature,Footnote 1 in large part because scholars have not articulated clear normative criteria for what counts as a ‘good’ decision.

We aim to explore whether the public is capable of using party cues to make good judgments – where we use normative criteria articulated in the literature on ecological rationality to evaluate judgments. We asked a sample of the public to make judgments about U.S. Representatives’ voting behavior using a profile based on party cues as well as a randomly determined number of less diagnostic cues. We also recruited a sample of state legislators to perform the same task to explore the performance of elites and to benchmark the performance of the public. We find that even the most attentive segment of the public performs poorly. However, we note that the accuracy of even the state legislators’ judgments is somewhat sensitive to the inclusion of irrelevant cues; when more cues with lower predictive validities are included in the profile, state legislators’ judgments become less accurate. We conclude with some avenues for future work and practical recommendations for improving the public's political judgments.

Ecological rationality as a normative standard for evaluating cue use

Scholars have debated whether the average citizen can use cues to compensate for a lack of substantive political knowledge. While a complete review of the heuristics literature is beyond the scope of this paper (for reviews, see Bullock, Reference Bullock2020; Kuklinski and Quirk, Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000), we briefly outline two approaches that have been used to explore whether cues – such as party cues – serve as a substitute for other information. First, a large body of work has explored whether political sophistication moderates the impact of party cues (e.g., Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Lau and Redlawsk, Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Andersen and Redlawsk2008; Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019). One would expect that the more politically sophisticated, having a larger store of relevant information, would be less likely to rely on party labels. Research on whether sophistication moderates party cue use is mixed (for a review, see Bullock, Reference Bullock2020). However, even if it were clear that sophisticates differed in their use of party cues, it would be unclear if sophisticates made better judgments. As a critique of an earlier body of work using similar criteria argues, ‘even the relatively well informed fall short of being well informed’ (Kuklinski and Quirk, Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000: 155). That is, the quality of judgments of even political sophisticates in a sample is unclear. Moreover, political sophistication can be related to other characteristics, such as motivation to engage in biased partisan reasoning (e.g., Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006), meaning that differences in judgments due to sophistication are not solely due to differences in information.

Another body of research explores whether party cues are less likely to be used when other information is available. For example, Bullock (Reference Bullock2011) asks study participants whether they support a policy, randomly assigning them to receive party cues related to the legislation, and also randomly assigning the amount of substantive information about the policy. Bullock finds that as more information is available, people's policy judgments are less influenced by party cues. Reviewing other research that includes the manipulation of party cues alongside other information – including observational research that shows that party cues have a relatively large impact in low-information elections such as initiatives, referenda and down-ballot races (Schaffner et al., Reference Schaffner, Streb and Wright2001; Ansolabehere et al., Reference Ansolabehere, Hirano, Snyder and Ueda2006) – Bullock (Reference Bullock2011, Reference Bullock2020) find that the more information provided, the less influential party cues are in general. The results suggest that party cues can serve as an information substitute but become less important when other substantive information is available.

The question of whether party cues serve as information substitutes appears to hinge on an empirically verifiable, value-free question: when other information is available, does the impact of party cues decrease? However, similar to other work in the heuristics tradition, there are normative questions lurking that introduce ambiguity into the interpretation of these results. Did the quality of judgments improve when party cues were available? Did participants make better judgments when more substantive information was available or did the additional information merely distract from potentially very informative party cues, leading to worse judgments (a phenomenon known as the dilution effect; Nisbett et al., Reference Nisbett, Zukier and Lemley1981)? Whether people rely less on party judgments when other information is available says little about the quality of judgments made with party cues – or, for that matter, whether judgments actually improve when other information is available.

These questions, reminiscent of Kuklinski and Quirk's (Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000) earlier critiques, are unanswerable without normative criteria to evaluate judgments, and raise the question of what criteria researchers should use when evaluating decision-making in political contexts. Recent work on political judgments (Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2021; Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021) has revived and further articulated the concept of ecological rationality (Brunswik, Reference Brunswik1952; Simon, Reference Simon1956; Gigerenzer, Reference Gigerenzer2019). Traditional expected value approaches consider optimization to be a universally rational approach, regardless of features of the particular decision environment (Hertwig et al., Reference Hertwig, Leuker, Pachur, Spiliopoulos and Pleskac2022). Ecological rationality, alternatively, uses a contingent normative standard of whether a particular decision strategy is well adapted for a given environment (Brunswik, Reference Brunswik1952; Simon, Reference Simon1956; Gigerenzer, Reference Gigerenzer2019).

According to Fortunato et al. (Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021, Supplementary Appendix), a decision strategy is ecologically rational if it is (a) cheap, making use of readily available indicators; (b) accurate, producing accurate judgments about long-run frequencies in the population and (c) simple, achieved with an easily applied rule rather than a complex synthesis of information. Using party cues appears to fulfill the first two criteria, being readily available in many political contexts and, as we demonstrate below, inferences drawn from party cues can have strong predictive validity for legislative behavior. The current work aims to assess the third criteria, exploring whether using party cues to make judgments is simple.

However, some clarification of simplicity is in order before considering this criterion in the context of party cues. In defining simplicity, Fortunato et al.'s (Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021, Supplementary Appendix) review of work on ecological rationality states that an ecologically rational heuristic ‘relates relevant cues to inferences in a simple way that the average person can accomplish easily and intuitively’. Simplicity in this formulation appears to conflate two distinct concepts: the relationship of cues to inferences, and the ability of the typical person to use the heuristic. The first concept appears to be similar to the concept of frugality as conceptualized by a different set of authors (Hafenbrädl et al., Reference Hafenbrädl, Waeger, Marewski and Gigerenzer2016). According to a recent review, ‘[t]he degree of frugality of a heuristic (for a given task) can be measured by the average number of predictors it requires’ (Hafenbrädl et al., Reference Hafenbrädl, Waeger, Marewski and Gigerenzer2016: 224). The second criteria relates to the concept of accessibility as outlined in the same review of the heuristics literature: accessible heuristics are ‘easy to understand, use, and communicate. If experts alone are able to use a proposed decision aid, it will not have an impact in domains where decisions are mainly made by laypeople with limited know-how and experience’ (Hafenbrädl et al., Reference Hafenbrädl, Waeger, Marewski and Gigerenzer2016: 222). Expert and lay heuristic use have been compared across a variety of domains (Garcia-Retamero and Dhami, Reference Garcia-Retamero and Dhami2009; Snook et al., Reference Snook, Dhami and Kavanagh2011; Pachur and Marinello, Reference Pachur and Marinello2013), with evidence suggesting that experts often make superior judgments by using fewer pieces of information – suggesting that frugality and accessibility are distinct concepts. Likewise, party cues, while frugal – requiring only a single piece of information to make accurate judgments – may not be accessible, or usable, by non-experts.

The accessibility of party cues

Political scientists have considered party cue use as a potential substitute for specific information about political figures (Downs, Reference Downs1957). For example, instead of learning about the specific details about what policies a candidate supports by consulting news reports, candidate speeches and campaign materials, voters can limit the costs of acquiring information about the candidates by using party cues. Contrasting the use of party cues to, say, infer a candidate's position on an issue to seeking and consuming individuating information about that candidate, political scientists often refer to the use of party cues as a heuristic (e.g., Rahn, Reference Rahn1993; Lau and Redlawsk, Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001). For example, a prominent critical review of research on political heuristics considers party cue use to be an example of a heuristic, stating that ‘[a]dvocates have identified many kinds of political heuristics. In elections, the classic voting cue is, of course, the political party … ’ (Kuklinski and Quirk Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000: 155).

Although political scientists have often considered the use of party cues as a heuristic judgment in contrast to more effortful strategies involving seeking out more individuating, substantive information, researchers in other fields have theorized that cue use can either be part of either a heuristic strategy or a more comprehensive strategy. In research on judgment and decision-making, for example, when provided with a set of cues, decision-makers could attempt to optimally weigh all available cues (e.g., Czerlinski et al., Reference Czerlinski, Gigerenzer, Goldstein, Gigerenzer and Todd1999). The use of cues in this fashion reflects a more complex strategy involving the synthesis of all available information when making a judgment, which is hardly a heuristic strategy. Likewise, the literature in persuasion suggests that cues can be processed peripherally – that is, as a heuristic judgment or shortcut – or can be processed systematically by more effortfully connecting cues to existing knowledge structures (e.g., Petty and Cacioppo, Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986). Using party cues to make judgments can likewise be part of either a heuristic strategy or a more effortful approach.

Therefore, the use of a cue does not imply a heuristic judgment, as some political science research has suggested. Relatedly, our interests concern whether party cues are accessible to – or able to be used by – laypeople (Hafenbrädl et al., Reference Hafenbrädl, Waeger, Marewski and Gigerenzer2016). The literature in judgment and decision-making has suggested that using cues to make accurate judgments may require considerable subject knowledge (Garcia-Retamero and Dhami, Reference Garcia-Retamero and Dhami2009; Snook et al., Reference Snook, Dhami and Kavanagh2011; Pachur and Marinello, Reference Pachur and Marinello2013). Partisan cues may likewise increase the accuracy of political judgments, although how much knowledge is required to apply partisan cues has been debated. While apparently straightforward, applying partisan cues to make judgments about policymakers’ positions requires knowing both a figure's party affiliation as well as which party supports the bill. The latter may be inferred from other knowledge (Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019), although making such an inference requires some contextual knowledge and the ability to link cues to that knowledge.

Prior work nonetheless suggests that people can use party cues as part of an ecologically rational decision-making strategy. Fortunato and Stevenson (Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2021) and Fortunato et al. (Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021) find, consistent with the ecological rationality of cue use, that the use of party cues depends on the broader political context. People are more likely to apply party cues to make judgments about the positions of loyal partisans than to ‘mavericks’ who do not consistently vote with their party (Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019) and are more likely to be aware of party positions (and less about individual policymakers) when the parties are homogeneous and distinct (Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2021). The results suggest that the public's use of partisan cues is ecologically rational, adapting cue use to features of the environment that make party cues either more or less valid in judging policymaker positions. Research on whether cue use is accessible for the general public is therefore somewhat ambiguous, with some research suggesting that cue use requires considerable contextual knowledge, and other results suggesting that people's use of cues adapts to the broader environment.

The current study aims to decrease the ambiguity concerning the accessibility of party cues and to evaluate judgments made with the use of cues and other information. Our work builds on prior work in a number of ways. First, instead of asking respondents to make judgments about named political figures (Ansolabehere and Jones, Reference Ansolabehere and Jones2010; Dancey and Sheagley, Reference Dancey and Sheagley2013; Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2021), raising the possibility that party cue use is confounded by likeability of a political figure (Sniderman, et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991) or projection (Wilson and Gronke, Reference Wilson and Gronke2000; Ansolabehere and Jones, Reference Ansolabehere and Jones2010), we remove specific characteristics of policymakers in order to isolate the influence of party labels on judgments (however, see Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019). Second, we ask respondents to make judgments about a random sample of Representatives, allowing us to evaluate the validity of cues included in the profiles by comparing the long-run empirical relationship between cues and policy positions for the population of all Representatives. Moreover, informing respondents that the target Representatives are a random sample of the population limits strategic behavior on the part of respondents, who might otherwise assume that target Representatives are selected based on other criteria, such as selecting non-stereotypical Representatives in order to create a challenging task (see Gigerenzer et al., Reference Gigerenzer, Hoffrage and Kleinbölting1991). Finally, to provide greater context for the public's use of cues, we compare the use of the cues by the general public to expert cue use, evaluating judgments made by a sample of state legislators. In comparing elite and public samples, our study is similar to other work evaluating citizen competence (Jennings, Reference Jennings1992; Granberg and Holmberg, Reference Granberg and Holmberg1996; Lupton et al., Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015). As mentioned above, prior critiques of evaluations of cue use have argued that using judgments of the most well-informed members of a sample as a normative standard of the rationality of cue use is flawed (Kuklinski and Quirk, Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000: 155). We agree with this critique, using alternative normative standards in estimating the objective validities of party cues. However, including a sample of presumably highly informed people – state legislators – could serve to demonstrate whether it is feasible to expect people to be able to apply party cues to make judgments. If state legislators were unable to use party cues to make reasonable judgments, it would suggest that our expectations about the application of party cues are unrealistic, thereby casting doubt on the validity of our task in evaluating judgments.

HypothesesFootnote 2

The current study concerns the ecological rationality of party cue use among the public and political experts. While some work has suggested that cue use can lead to valid judgments even given low levels of substantive political knowledge (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Popkin, Reference Popkin1991; Sniderman et al., 1993; Lupia, Reference Lupia1994), other scholars have argued that cue use requires contextual knowledge (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996). Work in both political (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991; Lau and Redlawsk, Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001; Lau et al., 2008; Fortunato and Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019) and non-political (Garcia-Retamero and Dhami, Reference Garcia-Retamero and Dhami2009; Snook et al., Reference Snook, Dhami and Kavanagh2011; Pachur and Marinello, Reference Pachur and Marinello2013) contexts suggests that experts are better at applying heuristics than the general public. We, therefore, propose the following as a research question:

RQ1: How will accuracy scores differ between the general public respondents and state legislators?

The following set of hypotheses concerns the effect of the number of cues available on accuracy judgments. As we will show below, the design of the decision-making environment is such that party cues are the only diagnostic cue available. The remaining cues are non-diagnostic. Therefore, the accuracy of judgments should be lower with the addition of irrelevant cues.

Using one valid cue performs better than complex decision-making strategies (such as an optimally weighting all available cues) when the cues are non-compensatory – that is, when cues are ordered according to predictive validity, the predictive validity of each cue is greater than the sum of the predictive validity of all subsequent cues (Martignon and Hoffrage, Reference Martignon and Hoffrage2002). The set of partisan bills presented in the current design, as explained below, involves non-compensatory cues, with one highly valid cue (party) and a variety of non-valid cues.

The availability of non-valid cues may detract from accurate judgments. First, non-diagnostic cues may simply distract from party cues, leading to less accurate judgments (Nisbett et al., Reference Nisbett, Zukier and Lemley1981). If this occurs, substantive knowledge may aid respondents in distinguishing diagnostic and non-diagnostic cues, and state legislators would therefore be more adept than the public at distinguishing valid from invalid cues and would be less likely to be influenced by irrelevant cues. Alternatively, respondents – rather than simply relying only on diagnostic cues – may use a slightly more complex decision-making strategy, such as a tallying rule, making a decision consistent with the balance of equally weighted cues. This tallying strategy has been shown to be ecologically rational in some contexts (Dawes, Reference Dawes1979). If state legislators are more likely than the public to apply an ecologically rational tallying strategy, they may be more likely to be led astray by irrelevant cues. Therefore, we state the hypotheses separately for each sample:

H1a: Accuracy scores for the general public will decrease as the number of cues increases.

H1b: Accuracy scores for state legislators will decrease as the number of cues increases.

Method

To test these predictions, we used an online survey experiment in which the number of cues was randomly assigned. We collected data from two samples, an expert sample (state legislators serving in the United States) and a public sample (an online sample collected from Amazon's MTurk platform). The survey explained that respondents would be asked to predict voting positions on five prominent bills from 2019 to 2020 for a random sample of six U.S. Representatives using only a set of cues. The bills were selected from a list of the most viewed bills for the 116th Congress (Congress.gov, n.d.) to represent a diverse set of highly salient issues. We selected four bills on which the parties were divided and one with broad bipartisan support. The votes selected involved only final passage on bills, and bills were selected to avoid technical issues. More specifically, we selected bills that would be easy to understand with a brief description to avoid assuming prior familiarity with each of the bills.Footnote 3 The strategy of selecting salient, party-line or unanimous votes was meant to facilitate the application of heuristics to judgments about Representatives’ positions.Footnote 4

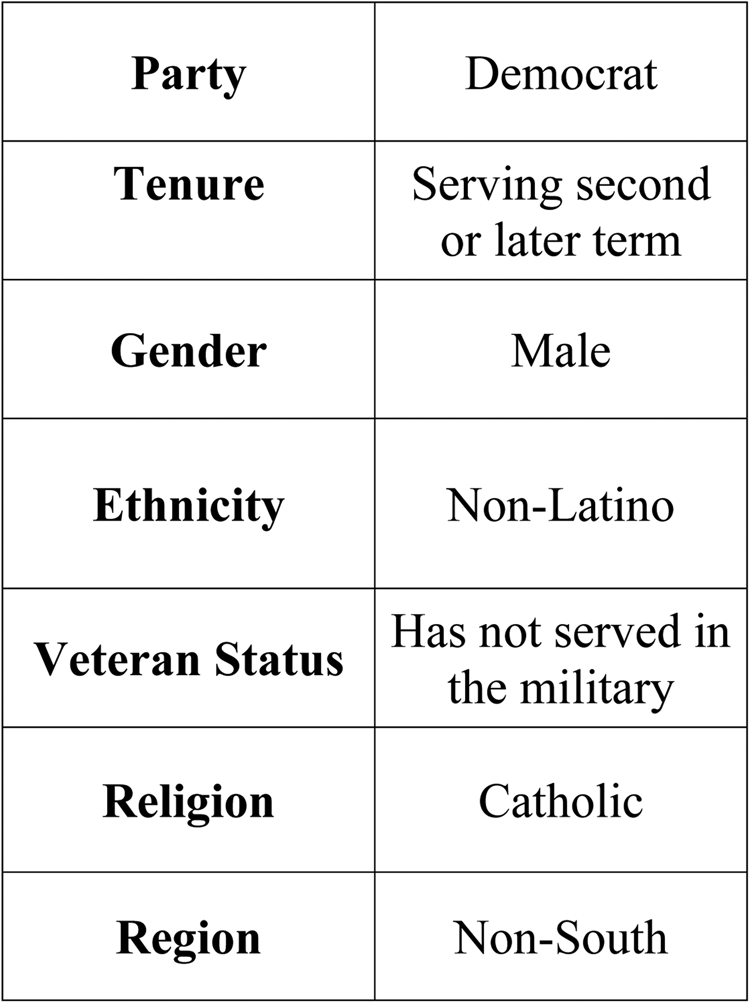

To randomly select six Representatives for stimulus materials for the two studies, we stratified on party, gender and region, randomly selecting six U.S. Representatives from among those who voted on all five bills selected in the 116th Congress.Footnote 5 Respondents were asked to make a judgment about each Representative's position on the set of five bills and were encouraged to guess even if they were not certain, for a total of 30 judgments (6 Representatives * 5 bills). The full set of cues included the Representative's party affiliation (Democrat/Republican), gender (male/female), ethnicity (Latino/a, non-Latino/a), veteran status (served in military/did not serve), religious affiliation (Catholic/non-Catholic), region (South, non-South) and tenure (serving first term/second term or higher). All cues are binary to facilitate comparisons of predictive validity between cues.Footnote 6

After rating each of the six Representatives, respondents then rated the usefulness of all seven cues on a five-point scale (not at all useful, slightly useful, somewhat useful, very useful, extremely useful) and responded to a variety of demographic and political (attention to politics, party and ideology) questions, followed by an open-ended request for feedback on the study.Footnote 7

Expert (state legislator) sample

A list of state legislators with email addresses was obtained from Open States (https://openstates.org/data/legislator-csv/). State legislators were invited via email in January 2022 to participate in the study. The invitation explained that the survey concerned expert decision-making and that the survey was brief.Footnote 8 Two follow-up emails were sent to recruit additional respondents. Out of 7,114 state legislators with valid email addresses, 72 participated.Footnote 9

Public (MTurk) sample

MTurk respondents (N = 408) with a HIT approval rate of greater than or equal to 99% and at least 100 completed HITsFootnote 10 (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Larsen, Caulfield, Elder, Jordan and Capron2020) were offered an incentive of $0.50 to complete a survey about ‘current events’. Both the public and state legislator samples are limited to respondents that completed at least one of the 30 judgments about Representatives, described below. Descriptive statistics for both samples are presented in the Supplementary Appendix.

Stimulus

For each of the six target Representatives, respondents were randomly assigned to receive one, three or seven cues. The party-only condition included only the party cue; the few cues condition included three cues, including party, tenure and gender; and the many cues condition included the three cues in the few cues condition as well as region, religion, ethnicity and veteran status. The order of cues was randomly assigned, with party appearing either first or last; the same order was maintained for all six Representatives for each respondent. To avoid the confounding influence of other factors, there was no other identifying information in each profile. An example stimulus is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Sample stimulus profile.

Predictive validity of party cues

Before proceeding to the results, we assess the predictive validity of the binary cues for the full population of U.S. Representatives for the set bills selected. We regressed votes for each of the five bills on all binary cues included in the study.Footnote 11 The coefficients for the seven cues from the ordinary least squares regressions (estimated with clustered standard errors) are presented in Figure 2. The figure shows that among the cues listed, party labels have by far the highest predictive validity. None of the other binary cues has a sizeable impact on voting behavior after controlling for party. The CARES Act, which received support from a large percentage of Representatives of both parties, provides an exception to this pattern, as none of the cues is particularly diagnostic.

Figure 2. Predictive validity of binary cues.

Due to the non-compensatory nature of the structure of cues for four out of five bills selected (Martignon and Hoffrage, Reference Martignon and Hoffrage2002; Hogarth and Karelaia, Reference Hogarth and Karelaia2006), the optimal strategy for respondents would be to use only party affiliation and ignore the rest of the cues.Footnote 12 For the remaining bill, the CARES Act, a reasonable heuristic, would be to assume that all Representatives support the bill. In fact, using these heuristics would lead respondents to guess correctly in all judgments for the sample selected. An alternative analysis confirmed that heuristic use – using party identification for the partisan bills and assuming all Representatives support the CARES Act – would lead to very accurate judgments on average. Estimating the mean number of votes compatible with these heuristics using 10,000 bootstrap samples of size N = 6 from the complete list of Representatives with non-missing voting data on all five bills predicts that a mean of 29.5 (bootstrap SE = 0.99) votes out of 30 were compatible with these two heuristics; 95% bootstrap CI = (26, 30), percentile method. The results show that regardless of the specific sample selected, heuristic use leads to accurate judgments.

Results

The first research question concerns the relative performance of the expert and public samples. The average percentage correct out of all responses provided is displayed in Figure 3. The top panel shows the results for state legislators overall and by treatment condition. State legislators were correct in 86 percent of judgments. The percent correct varied by treatment condition: nearly all state legislators – 95 percent – provided correct judgments in the party-only condition, vs 91 percent in the few cues condition and 80 percent in the many cues condition. The differences between conditions are statistically significant (two-tailed paired t-test: party vs few: p = 0.03; party vs many: p < 0.001; few vs many: p = 0.03). The second panel shows the results for the MTurk sample. This sample performed less impressively: across all treatment conditions, 60 percent of all judgments were correct. The percentage did not vary across treatment conditions, with only slightly higher accuracy in the party-only condition (62%) relative to the few cues condition (59%) and the many cues condition (60%). The differences between treatment conditions are not statistically significant (two-tailed paired t-test, p > 0.05).

Figure 3. Percent correct by condition.

The bottom panel limits the MTurk sample to those who scored at the 90th percentile or higher on the standardized score of attention to politics.Footnote 13 These respondents fared similarly to the overall MTurk sample, with only 62 percent of all judgments correct. Unlike the state legislator sample, these respondents performed better when provided with few (60%) or many (64%) cues than receiving only the party cue (53%), although these differences were again not statistically significant (two-tailed paired t-test, p > 0.05). Overall, the results show that state legislators performed much better than even the most attentive respondents in the MTurk sample, and respondents in the state legislator sample – but not the public sample – were responsive to the number of cues available, performing worse when more invalid cues were available. The results provide support for H1b but not H1a.

While not a formal hypothesis or research question, we also explored differences in accuracy scores across the five bills (see Figure 4). Recall that party was highly diagnostic for all of the bills except for the CARES Act, which received bipartisan support. The results show that state legislators scored much higher on the four partisan bills than the bipartisan CARES Act. However, about three quarters of judgments about the CARES Act were correct – still higher than the percentages for any of the bills for the MTurk sample.

Figure 4. Percent correct by bill.

The results for the public sample are explored further with a regression model. Small sample size precludes this approach for the state legislator sample, who are not included in the analysis. A multilevel model including random intercepts for respondent and Representative predicts accuracy scores for each Representative (out of a possible five) with indicators of treatment category (indicators for three cues or seven cues; baseline = party cue only).Footnote 14 The models were estimated without and with the full set of controls. Results are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Predicting number of judgments (out of 5) consistent with party cue use (MTurk sample)

Notes: Random intercepts for respondent and Representative included.

+p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, two-tailed.

In both Models 1 and 2, the coefficients for few cues are small and not statistically significant, although both coefficients are negative, as predicted. The coefficient for many cues is negative and, in Model 2, statistically significant, suggesting that those exposed to more non-party cues performed worse than those exposed to party cues alone. The results, unlike the comparison of percentages across treatments with no controls, provide some support for support H1a: a longer list of non-party cues decreases the accuracy of judgments.

Considering the coefficients for the control variables, attention to politics is positively related to accuracy. The coefficient for attention to politics in Model 2 is positive and statistically significant, although the magnitude is modest: a one standard deviation increase in attention to politics leads to an increase of 0.19 out of five judgments. The results suggest, similar to the results displayed in Figure 3, that accuracy increases with attention, but that these effects are not large, and that even respondents with the highest levels of attention to politics in the sample are not predicted to approach the accuracy of state legislators.

Regarding the other coefficients, both ideological extremism and party strength are negative and statistically significant, an unexpected finding given that both of these variables would appear to contribute to using party cues. Education is also negative and statistically significant, another puzzling result, given that one would expect those with higher levels of education to recognize the value of party cues in the current environment, although we note that these effects are estimated controlling for attention to politics.

How to explain the differences in performance across state legislators and even the most attentive members of the public? Figure 5 provides some clues, displaying ratings on a five-point scale of the usefulness of each of the seven cues for the state legislator and MTurk samples. The results show that average ratings for usefulness of party cues are relatively high for both members of the public (M = 4.1, SD = 0.92) and for state legislators (M = 4.4, SD = 0.93), although state legislators rated party cues as slightly more useful. Perhaps more important for explaining the results are the stark difference in ratings of the non-party cues between the two samples. Respondents in the MTurk sample rated the other cues as lower, on average, than party cues, although all the cues were rated slightly above the midpoint of the scale. State legislators rated the non-party cues much lower, close to the bottom of the scale. The results suggest that state legislators performed much better on the task by placing less weight on invalid cues. However, this result should be somewhat tempered by the finding that state legislators performed worse when more irrelevant cues were available, suggesting that state legislators did not completely ignore non-diagnostic information.

Figure 5. Ratings of cue validity.

Discussion

Some work suggests that party cues – or other valid cues – have the potential to compensate for the public's lack of political knowledge, as party cues are less influential when substantive information is available. However, this prior work does not use clear normative criteria to evaluate the quality of judgments. The results presented here, drawing on normative criteria from the literature on ecological rationality, suggest that people lack the ability to use party cues to make accurate judgments. In our study, the accuracy of the public's judgments was not much better than what we would expect had they made their judgments using coin flips. Although there is some evidence that judgments improve with attention to politics, these gains are small, and even the most attentive members of the public do not approach the accuracy rates of state legislators.

State legislators, on the other hand, are especially adept at using cues to make valid judgments. State legislators correctly recognized that party cues were highly diagnostic for voting behavior for most of the bills, and, perhaps even more important, recognized that the remaining cues were not especially useful in making accurate judgments (although we note that state legislators’ performance was less accurate when non-diagnostic cues were included in the profiles, a point we discuss in greater detail below). The fact that state legislators’ performance differs dramatically from even the most attentive members of the public demonstrates the high threshold of contextual knowledge required to effectively use party cues to make judgments. Party cues may be frugal, requiring only a single piece of information to make accurate judgments in some contexts – but this does not mean that they are accessible, usable by the typical voter.

The failure of the public to make accurate judgments is compatible with prior work on citizen competence (Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964; Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996). For example, Freeder et al. (Reference Freeder, Lenz and Turney2019) find that fewer than 20 percent of the public can consistently estimate party and candidate positions. A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center (2012) finds, similarly, that people are not aware of major party positions on a number of salient issues. Guntermann and Lenz (Reference Guntermann and Lenz2021) find that the public does not appear to be aware of candidates’ stances on measures related to COVID – a pandemic that dominated news coverage for months and on which major party figures were visibly at odds.

An implication of the current work is that the information environment may contribute to the accurate application of heuristics. One finding was that the number of non-diagnostic cues decreases accuracy, especially among state legislators. Without a clear normative benchmark to evaluate this result, this finding would have appeared to support the notion that people are using party cues as a substitute for other information: when other cues are available, people are less likely to rely on party cues. However, our results show that judgments are in fact less accurate in the presence of more, non-diagnostic information. Lower reliance on party cues when other information does not necessarily imply a reasonable judgment strategy. In other words, clear normative criteria are critical in interpreting the results.

The influence of non-diagnostic cues may speak to the potential of distracting information to diminish accuracy even for those with high levels of expertise, providing evidence that information overload (e.g., Pothos et al., Reference Pothos, Lewandowsky, Basieva, Barque-Duran, Tapper and Khrennikov2021) is potentially detrimental to accurate decision-making. An alternative explanation is that state legislators may be more likely to use a strategy to combine available cues. For example, a tallying strategy (Dawes, Reference Dawes1979), involving summing the signs of all cues with unit weights to make a judgment, has been shown to be ecologically rational in some contexts. A practical implication of this finding is that communicators seeking to inform or persuade should be aware that irrelevant cues could lead even seasoned political audiences astray.

The normative perspective of the heuristics and biases literature has played an important role in the field of behavioral public policy, identifying potential biases that can arise from boundedly rational decision-making (e.g., Pronin and Schmidt, Reference Pronin, Schmidt and Shafir2013). However, arguments about the benefits of cue use – such as the idea that simple applications of cues can be a ‘fast and frugal’ strategy leading to accurate judgments (Gigerenzer and Todd, Reference Gigerenzer, Todd, Gigerenzer and Todd1999) – turn some common normative claims about judgments on their heads. Prior work correctly emphasizes the dangers of overreliance on cues, for example, in stereotyping (Pronin and Schmidt, Reference Pronin, Schmidt and Shafir2013). But can cues also be under-used? We find that members of the public would make more accurate judgments in evaluating the policy decisions of legislators if they relied more on party cues, contributing a novel perspective to discussions of citizen competence.

The literature on fast and frugal heuristics is both descriptive and prescriptive (Hafenbrädl et al., Reference Hafenbrädl, Waeger, Marewski and Gigerenzer2016), empirically testing and characterizing actual decision-making as well as providing tools that people could use to improve decision-making. Descriptively, we show that members of the public do not rely on party cues when making judgments. We believe that this observation has been missed by prior work that has categorized party cues as a ‘simple’ heuristic without elaborating on the meaning of this concept. Party cues, although frugal – involving only a single piece of information – are not necessarily accessible to non-experts. We also note that party cues are a valid predictor of voting on highly controversial bills, and that experts tend to use party labels when making inferences about voting behavior. Prescriptively, the results suggest that people could improve their judgments by better making use of party cues. Future work could more deeply explore why people are incapable of applying party cues, and consider how people could be taught to more effectively use party cues to make inferences as a part of civic education, broadly conceived (e.g., Lupia, Reference Lupia2016).

Conclusion

In applying normative criteria of ecological rationality to the influence of party cues, we respond to Kuklinski and Quirk's (Reference Kuklinski and Quirk2000) critique that those who argue about the efficacy of party cues need to articulate what counts as a ‘good or at least reasonable’ judgment (pp. 155–156). When applying our normative criteria, we find that the public, contrary to interpretations in some prior work, is incapable of effectively using party cues to make accurate judgments. Our results suggest that prior work claiming that party cues act as an information substitute needs to be re-evaluated, as people do not make accurate judgments when party cues are available, and the influence of other available information can in fact lead to worse judgments – even for experts. Despite the decrease in accuracy in the presence of non-diagnostic cues, we propose that political experts are generally more likely to make accurate judgments in part because they place much less weight on irrelevant information when making judgments.

There are some limitations to the current study. First, the samples may preclude generalization to broader populations. While the state legislative sample frame included contacts for a large proportion of state legislators, some emails were missing from the initial list. In addition, the response rate was lower than prior studies, which may be due to the length and timing of the survey. The public sample relied on an online sample using Amazon's MTurk, and while some studies have provided evidence for the validity of these studies (Berinsky et al., Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015), future work could explore the results with representative samples of both public and elite respondents.

Second, we included a mix of bills in our study, and while party cues were applicable to four of the five bills, a unanimity heuristic (such as ‘all Representatives are likely to support this type of bill’) would lead to accurate judgments on the fifth. An unanswered question is how expert respondents know to what extent to rely on party cues vs unanimity heuristics – or whether to apply some other strategy. Being able to better specify under which conditions decision-makers apply party cues and other information could lead to deeper insights about political decision-making and could lead to practical applications, such as developing materials to help people better use political cues and other decision strategies.

A related limitation is that the sample of bills selected for the study may limit generalizability to other issues. Specifically, the bills selected for the study were highly salient, and easily understandable with a brief description, and are therefore not necessarily representative of the larger population of all bills. Yet, a representative sample of bills is not necessarily desirable for studying the accuracy of cues given that the vast majority of bills deal with trivial or highly technical issues (e.g., Cameron, Reference Cameron2000). Both elected officials and the public would presumably perform less well in making judgments of more typical bills due to less media coverage, less visible elite position-taking or simply because the application of party cues or unanimity heuristics are either unclear or irrelevant. Future studies should explore how to better define the population of non-trivial bills to better explore the ecological rationality of party cue use.

A vast body of research documents the lack of substantive knowledge about politics among the public (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996). Remedies for this lack of substantive knowledge are in short supply given the ambiguous roles of typical sources of political information. For example, there is mixed evidence about the influence of traditional civic education on levels of political knowledge (Galston, Reference Galston2001) and for some segments of the public, low levels of political knowledge have in fact been exacerbated with the growth of online media sources (Prior, Reference Prior2005). The resiliency of the public's lack of substantive knowledge leaves cue use – relying on simple rules to apply readily available information – as a potential hope for improving citizen competence. Our work suggests that are unable to apply party cues to make good judgments. However, applying party cues is a skill that some experts have, raising the possibility that it could be acquired with training and feedback – as has been demonstrated with other ‘fast and frugal’ cues in other domains (Gigerenzer et al., Reference Gigerenzer and Todd1999; Hafenbrädl et al., Reference Hafenbrädl, Waeger, Marewski and Gigerenzer2016). Future work could explore this possibility, considering whether people can be trained to better use party cues as a part of civic education, broadly conceived (Lupia, Reference Lupia2016).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2023.28.