Introduction

Preservice music educators (PMEs) have reported that authentic teaching experiences in primary and secondary schools helped prepare them for a career in music education (Teachout, Reference TEACHOUT1997; Conway, Reference CONWAY2002; Kenny, Reference KENNY2018) and had lasting positive impacts on their development as teachers (Conway, Reference CONWAY2012; Bartolome, Reference BARTOLOME2017). When examining seventh-, eighth- and ninth-grade (aged 12–14 years) band students’ perceptions of an authentic teaching experience with PMEs, Kruse (Reference KRUSE2012) found that students perceived the experience as generally positive, but they also reported challenges such as ‘instructional clarity and low affect’ (p. 68). In addition, researchers have cited scheduling conflicts as one of the greatest challenges when coordinating authentic teaching experiences at primary and secondary schools – not only coordinating schedules but also that in-service school teachers are hesitant to give up rehearsal time and disrupt their routines (Brophy, Reference BROPHY2011; Parker et al., Reference PARKER, BOND and POWELL2017; Rawlings et al., Reference RAWLINGS, LARSEN and WEIMER2019). Therefore, if authentic teaching experiences are only used to improve PMEs’ teaching skills, the benefits may not outweigh the challenges for primary and secondary school students and in-service teachers.

To address challenges that primary and secondary school students may encounter, researchers have examined authentic teaching experiences designed to support all parties involved – such as community service learning, project-based learning, hands-on learning, experiential learning, artistic citizenship and service learning (Kwak et al., Reference KWAK, SHEN and KAVANAUGH2002; Elliott et al., Reference ELLIOTT, SILVERMAN and BOWMAN2016; Rawlings, Reference RAWLINGS, Conway, Pellegrino, Stanley and West2020). In the United States, service learning grew out of Dewey’s concept of lab schools (Kwak et al., Reference KWAK, SHEN and KAVANAUGH2002), and Eyler and Giles (Reference EYLER and GILES1999) defined service learning as:

a form of experiential education where learning occurs through a cycle of action and reflection as students work with others through a process of applying what they are learning to community problems and, at the same time, reflecting upon their experience as they seek to achieve real objectives for the community and deeper understanding and skills for themselves. (p. 18)

In other words, service learning is a unique fieldwork model that combines authentic teaching experiences with community service. A crucial component of service learning involves PMEs, in-service teachers, students and the school community receiving benefits. Therefore, service-learning experiences should: (a) benefit all parties involved, (b) serve as a medium to approach curricular goals, (c) address a community need and (d) engage participants in critical reflection (Bringle & Hatcher, Reference BRINGLE and HATCHER1995; Eyler & Giles, Reference EYLER and GILES1999; Kwak et al., Reference KWAK, SHEN and KAVANAUGH2002; Rawlings, Reference RAWLINGS, Conway, Pellegrino, Stanley and West2020).

In music education, researchers have found that PMEs benefited from service-learning experiences (Reynolds & Conway, Reference REYNOLDS and CONWAY2003; Burton & Reynolds, Reference BURTON and REYNOLDS2009; Bartolome, Reference BARTOLOME2013). For example, PMEs have reported that service-learning experiences improved their ability to: (a) provide student-centred instruction (Sindberg, Reference SINDBERG2020), (b) build relationships and connect with primary students aged 9–12 years (Kenny, Reference KENNY2018), and (c) identify personal biases and engage with students from cultures and demographics with which they were unfamiliar (Forrester, Reference FORRESTER2019). Therefore, service-learning experiences might foster the development of teacher/student rapport that are difficult to engender through in-class lectures or peer-teaching exercises (Forrester, Reference FORRESTER2019; Sindberg, Reference SINDBERG2020). The researchers cited above mostly focused on PMEs’ perceptions of service-learning experiences; however, aside from Sindberg (Reference SINDBERG2020), there exists scant research on primary and secondary school students’ perceptions of service-learning experiences in the music classroom.

Although findings are mixed, researchers have found that secondary students, aged 14–18 years, who took private lessons tended to perform at a higher level than those without private lesson experience, as measured by audition scores (Rohwer & Rohwer, Reference ROHWER and ROHWER2006). Researchers also reported that monetary barriers limited access to private lessons for some students (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference FITZPATRICK, HENNINGER and TAYLOR2014). In addition, choral or band teachers may lack the time and resources to provide students with one-on-one instruction (Scheib, Reference SCHEIB2003; Reference SCHEIB2006). Therefore, the purpose of this service-learning action research study was to develop and investigate after-school individualised vocal lessons for secondary students (aged 14–18 years) taught by PMEs. The research questions were as follows: (a) What were the secondary students’ perceptions of their vocal skills during and after the four private lessons? (b) What were the PMEs’ perceptions of their teaching dispositions, teaching skills, and pedagogical content knowledge during and after the four private lessons? (c) How did the PMEs and secondary students describe the benefits and challenges of the service-learning experience? Including the secondary students’ and PMEs’ perceptions of the service-learning experience was crucial to our action research design.

Methodology

We applied an action research design to our study, which involved solving problems through a cycle of reflecting, evaluating, planning and implementing (Cain, Reference CAIN2008; Reference CAIN2012; Patton, Reference PATTON2015). Action research was an appropriate method because our study was theoretically oriented, served a professional purpose, fostered practical skills and solutions, and involved continuous collaborative reflection (Rearick & Feldman, Reference REARICK and FELDMAN1999; Reason & Bradbury, Reference REASON and BRADBURY2001; Cain, Reference CAIN2008; Ward, Reference WARD2009). Specifically, our intentions were to: (a) improve secondary vocal student preparedness for solo experiences and performances, (b) provide an authentic teaching experience to improve preservice teacher instruction specific to vocal pedagogy, and (c) develop a mutually beneficial and collaborative service-learning experience. In this study, the researchers and participants all actively contributed and learned through the process.

Research site, researchers and participants

The research site was an urban public high school in the Western United States with an enrollment of around 1700 students aged 14–18 years. The ethnic distribution was approximately 49% Caucasian, 20% Hispanic, 19% who identify as other, 5% Pacific Islander, 4% African American, 3% Asian and 1% American Indian. These distributions were similar to the demographics of the surrounding city. Approximately 45% of students were eligible for free and reduced-price lunch at the school based on the income of the student’s family. We received Institutional Review Board approval and collected participant consent and parent/guardian permission forms.

Participants and researchers in the study (N = 30) consisted of PMEs (n = 12), secondary students aged 14–18 years (n = 15) and researchers (n = 3). The researchers are choral music educators who had previously established professional relationships and worked together as equals (Conway & Borst, Reference CONWAY2002). At the time of data collection, Author 1 was in her second year as a university professor with 9 years of experience teaching choir in the public schools; Author 2 was a second-year doctoral student in music education with 11 years of experience teaching choir in the public schools; and Author 3, with 11 years of teaching experience, was in her ninth-year teaching choir at the school where the service-learning experience occurred. We all wanted to improve our practices – Author 1 and Author 2 intended to help the PMEs enrolled in their choral methods course at the time of this study develop teaching skills specific to adolescent vocal pedagogy. Author 3 aimed to help the students enrolled in her choir class who might not have access to private music lessons receive individual vocal training. Therefore, we designed a mutually beneficial service-learning experience for secondary students and PMEs.

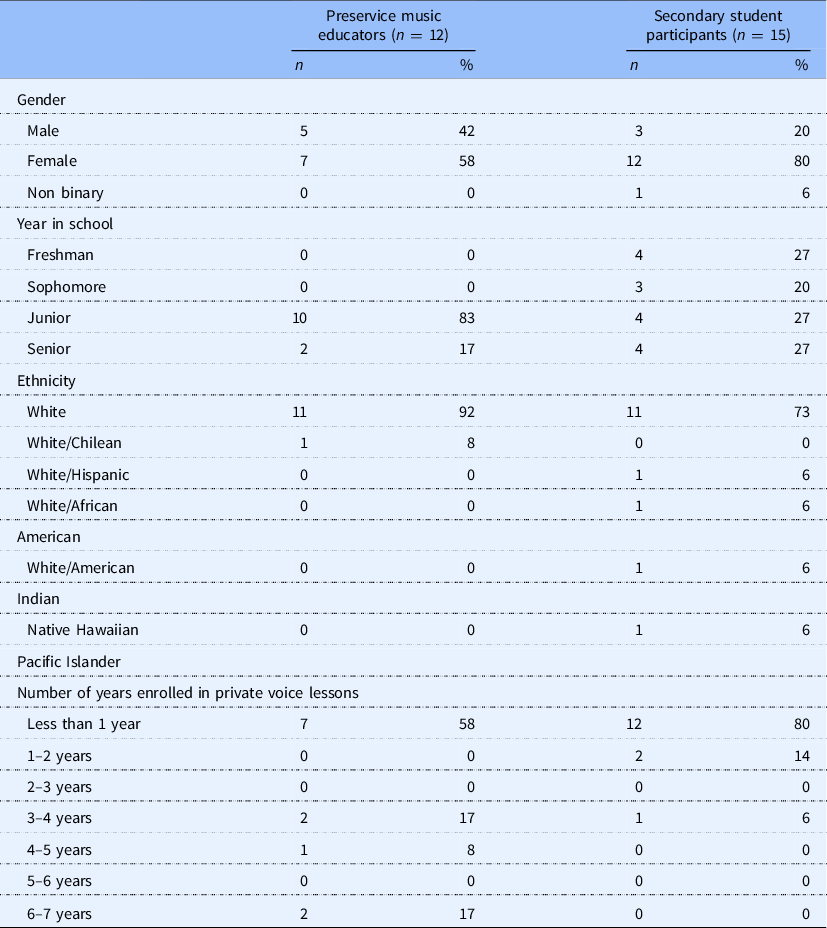

We viewed the PMEs as action researchers – supported by the associated reflective pedagogy of the research team and feedback from the secondary students. The PMEs taught lessons in pairs – each pair consisted of one choral PME and one instrumental PME. The PMEs who volunteered were enrolled in an undergraduate choral music methods course at the time of the study (see Table 1 for demographic information). Instrumental and choral PMEs took the course together to develop vocal teaching skills. For the instrumental PMEs in the programme, this course and a course on vocal techniques for instrumentalists are the primary courses that prepare them to teach a vocal ensemble. Choral PMEs take additional coursework in choral and vocal skills. The grouping of choral and instrumental PMEs together was purposeful so that the choral PMEs could act as subject-matter mentors to the instrumental PMEs.

Table 1. Demographics of participants

We invited all students enrolled in the school choral programme to participate in our study. Fifteen secondary students signed up to participate (see Table 1 for demographic information). Before the first lesson, they had the opportunity to communicate their voice part, repertoire preferences and any upcoming performance opportunities – such as the regional solo festival, university auditions and in-class performance assignments. Therefore, in consultation with the researchers, the PMEs selected three to four solo voice pieces for the secondary students to choose from during their first lesson. The selected repertoire included art songs such as Early One Morning arranged by Jean Shackleton, arias such as Nel Cor Più Non Mi Sento by Giovanni Paisiello, musical theatre songs such as How Could I Ever Know? by Lucy Simon and Marsha Norman and popular music such as Moving On by Paramore.

Before the study began, we collected schedules from the PMEs and secondary students. There were four Friday afternoons with the least number of conflicts. Therefore, across three months during the fall of 2019, the secondary students received up to four 30-min voice lessons from the PMEs. The number of lessons each PME taught varied based on the attendance of the secondary students. When accounting for secondary student absences, the service-learning experience resulted in 54 voice lessons. The choral PMEs led the first and second lessons, and the instrumental PMEs led the third and fourth lessons. They supported each other in the private voice lessons – accompanying on piano as needed, answering questions and engaging in dialogue as appropriate. In addition, the researchers served as active participants and rotated through the lessons and assisted as needed.

Data collection

Data collection included written reflections, focus groups, video recordings of each lesson, PMEs’ lesson plans, and our observations and feedback to the PMEs. Two weeks before the voice lessons began, we collected demographics, musical experience, and music learning/teaching goals of the PMEs and secondary students via Qualtrics software, version 9.19. Immediately after every voice lesson, the secondary students received a QR code via Qualtrics to a list of reflection questions (see Appendix A).

We used a plan–act–evaluate–reflect cycle after each service-learning experience to inform subsequent lessons (Cain, Reference CAIN2008). Service learning should ‘infuse analytic reflection into all stages’ (Kwak et al., Reference KWAK, SHEN and KAVANAUGH2002, p. 190), and because our PMEs also acted as action researchers, they took part in a similar plan-act-evaluate-reflect cycle. For example, both the researchers and PMEs watched the teaching videos and met to discuss and revise lesson plans before the next set of voice lessons. In addition, the PMEs completed written reflections based on Rolfe et al.’s (Reference ROLFE, FRESHWATER and JASPER2001) What? So What? Now What? framework for reflective writing with specific questions for the music classroom adapted from Rawlings et al. (Reference RAWLINGS, LARSEN and WEIMER2019). See Appendix B for the complete list of questions.

The PMEs and secondary students took part in one focus group within 3–10 days after the final voice lesson. To allow for informative dialogue during the focus groups (Kozol, Reference KOZOL1985), we divided the secondary students into two groups (one with six participants that lasted 58 min and one with eight participants that lasted 61 min) and two PME groups (one with four participants that lasted 53 min and one with seven participants that lasted 58 min). One secondary student and one PME were unable to take part in the focus groups. We served as active observers in these groups and asked open-ended questions designed to reconstruct important experiences (Eros, Reference EROS and Conway2014; Spradley, Reference SPRADLEY2016). Sample questions included, ‘Explain your thought process when you planned out your lessons’, and ‘Describe how this experience benefited and/or challenged your development as a vocal student/music educator’. Following the focus groups, we provided a QR code to an open-ended Qualtrics survey that allowed the PMEs and secondary students to provide additional perspectives anonymously. The total data consisted of approximately 1350 min of video footage and 270 pages of typed single-spaced data (including focus group transcripts, reflections, lesson plans, and the researchers’ observations and feedback).

Analysis

We completed the first cycle of coding as we collected the data – which included the video footage, reflections and lesson plans. We used Atlas.ti, version 8.4.4 to manually code the data. First, we used evaluative coding to examine the usefulness of the learning experiences (Saldaña, Reference SALDAÑA2016). Then, we coded the typed data in two additional cycles – tertiary elaboration coding ‘to develop, test, modify, and extend’ our understanding of the participants’ perceptions of their teaching and learning as it related to our purpose and method (Layder, Reference LAYDER1998, p. 124) and focused coding to categorise the most significant and relevant themes (Saldaña, Reference SALDAÑA2016). We examined the perspectives of the secondary students and PMEs through multiple modes of data collection, engaged their perspectives to inform subsequent cycles and participated in member checks after each action–research cycle (Creswell & Poth, Reference CRESWELL and POTH2018). In the findings, we have worked to create an honest description, not to generalise the experience, but to create relatability for the reader and inform practice.

Findings

Within our findings, we reviewed two sets of voices – the PMEs and the secondary students – and added our own observations as part of the evidence base. We viewed the PMEs as researchers; therefore, we highlighted their voices at the beginning of each theme. Then, within each theme, we indicated when data from the secondary students contextualised, supported, challenged and disagreed with the PMEs’ perceptions. In addition, there were notable differences between the choral PMEs’ and the instrumental PMEs’ perceptions, which we presented within the themes.

Teaching dispositions

PMEs’ perceptions of teaching dispositions

During the first week of lessons, several PMEs described a lack of interpersonal skills when teaching, especially when they encountered a particularly reserved secondary student. For example, after the first lesson, one instrumental PME wrote in his reflection, ‘She was so nervous…I didn’t know what to do in that situation’. After the PMEs examined the secondary students’ reflections, and we discussed the lesson, the PMEs planned time for casual conversation during subsequent lessons. In the focus group, one PME shared how she altered her behaviour to help the secondary student feel comfortable, ‘I was trying to sing it with her…dancing…showing her that we’re comfortable with it, made her more comfortable with it’. By the third lesson, the PMEs described how they improved interpersonal interactions with the secondary students. For example, one choral PME wrote,

Now that I’ve gotten comfortable around these students, and I’ve established a vibe with them, I feel like I can be more comfortable around them, and worry about the knowledge they’re receiving, rather than if I will do a good job.

The PMEs found that they could connect with the secondary students through casual conversations, which they perceived improved their overall teaching disposition.

Some PMEs perceived our feedback on their teaching dispositions as too critical and negative. One choral PME stated in the focus group, ‘There was a lot of things that we were supposed to fix…I felt like I was always on guard…the feedback was hard for me’. In contrast, one instrumental PME perceived that the feedback contributed to their development as a music educator. In the focus group he stated, ‘I was like…how could I take that to make me better in the long run…it was constructive feedback and I liked it’. Similarly, another instrumental PME stated, ‘It’s just the nature of what we’re going into…you take it in stride…that might have been something I didn’t wanna hear, but…I need to hear that information’. The choral PMEs displayed more sensitivity towards our critical feedback than the instrumental PMEs.

Secondary students’ contextualisation of teaching dispositions

Data from the secondary students supported our finding that the first lesson resulted in some awkward interactions. For example, one secondary student wrote in her first reflection that she felt ‘embarrassed’ because the PMEs abruptly introduced vocal warm-ups without asking about her day. Then, by the final focus group she stated, ‘my teachers were really nice…like I wanna be their friends…as well as them being [my] vocal teachers’. The secondary students appreciated that the PMEs were ‘kind and patient’, ‘had good energy’, ‘were pretty funny’ and helped them ‘feel less nervous’. In contrast, one secondary student stated in the focus group, ‘They’d normally be like – how are you doing? I’d be like – I’m good…I like wouldn’t want to get into detail…we didn’t do very much to like try and build a relationship’. Although the majority of secondary students enjoyed when the PMEs took the time to ask questions about their day and experiences, this secondary student described unsuccessful social interactions between himself and the PMEs.

Teaching skills

PMEs’ perceptions of teaching skills

Some PMEs described their responsive teaching skills during the service-learning experience. For example, in their second reflection, one choral PME wrote, ‘You have to listen to them and think…It requires a lot of focus…It’s challenging’. While observing the first lesson, we noticed that the PMEs focused more on how they delivered content rather than responding to the secondary students’ vocal needs. As the lessons progressed and they received feedback, some PMEs incorporated questioning techniques to engage the secondary students in the learning process. For example, in the focus group, one instrumental PME shared, ‘Just having a conversation about it, and then, being able to hear what they heard and having them talk about it…I think that really helps…That way, outside of this, they can, you know, keep going’. After engaging in the feedback cycle, some PMEs cited improved teaching skills, and specifically, their ability to engage the secondary students as critical thinkers.

Although some of the PMEs saw this as a valuable experience, the process also overwhelmed others, especially the instrumental PMEs. For example, in the focus group, an instrumental PME stated, ‘I teach beginning trumpet lessons…so that part wasn’t the scary part, it was more…Just teaching vocal lessons…Like, that’s not – not my forte…you know, I’ve climbed many mountains before, but not – not that kind of mountain’. Although instrumental PMEs reported some apprehension before teaching the voice lessons, they also conveyed some appreciation for real-world teaching experience in a vocal setting.

Some instrumental PMEs reported that engaging with choral PMEs provided a sense of support. For example, during the focus group, one instrumental PME stated, ‘It’s good to, like, have somebody that you can, like, really have a conversation with and, like, trust and say, hey, this isn’t, like, the best idea, or, like…this is a great idea. Good work’. In the focus group, one PME discussed the process of observing other voice lessons and stated, ‘That was really helpful, to kinda get my brain going, thinking about ways to listen and scaffold everything. It was cool watching him work’. However, some PMEs described negative interactions between teaching partners. For example, in the focus group, one instrumental PME stated, ‘It was hard to know how to get control of the lesson back’. Although tensions emerged among PMEs, some instrumental PMEs explained that they developed their teaching skills when working alongside their choral PMEs with vocal expertise.

Secondary students’ contextualisation of teaching skills

Data from the secondary students regarding teaching skills helped to contextualise the finding that the PMEs focused more on their development as teachers than the secondary students’ development as vocalists during the first two lessons. For example, one secondary student wrote that the first lesson ‘felt kinda awkward’ when the PMEs ran through warm-ups and repertoire without providing any specific feedback. As the lessons progressed, the secondary students noticed when the PMEs engaged them as critical thinkers. For example, in the focus group, one secondary student stated, ‘They’d be like – okay, now what did you do differently on that one? I’d be like – well, I felt it, and then I’d do it again, and it would feel better’. During each feedback cycle, some secondary students noticed when the PMEs engaged them as critical thinkers and adapted to their vocal needs.

Some secondary students shared that they enjoyed engaging with multiple teachers. In the focus group, one secondary stated, ‘You’re able to have like multiple opinions…different experiences’. However, one secondary student picked up on uncomfortable interactions among two PMEs. In the focus group she stated, ‘One of my teachers would say something and the other one would like contradict…And I’d be like – oh, what do I sing?’ Similarly, another secondary student stated,

It was hard to have both of them…both talking to me…it’s like I don’t know who I’m supposed to be listening to right now. Both of you are trying to give me advice, and it’s good advice. It just was not helpful coming at the same time.

Although the secondary students reported perceived benefits and challenges when engaging with multiple teachers, some of the cited challenges led to heightened moments of confusion and frustration.

Pedagogical content knowledge

PMEs’ perceptions of pedagogical content knowledge

During the first lesson, the PMEs commented more on musical errors – such as notes and dynamics, rather than pedagogical issues – such as breath support and vowel placement. For example, in her first reflection, one choral PME wrote, ‘I never told them what their soft palate was. I could have done better’. After the second lesson, another choral PME described that when her secondary student evaluated ‘tongue position and tension…she actually started to make the sound’. As the lessons progressed, the PMEs focused less on notes and rhythms, and more on teaching a healthy vocal technique.

The instrumental PMEs observed the choral PMEs during the first two lessons, which allowed them ‘a chance to actually start to hear these problems and how to fix them’. In the focus group, one instrumental PME stated, ‘My experience has taught me that there is a lot I still need to learn about the voice…I have learned I need to be prepared and that every voice is different and has different needs’. During the third and fourth lessons, the instrumental PMEs hesitated to provide a vocal model for the secondary students. Therefore, during one feedback cycle, we encouraged them to transfer skills they learned as instrumentalists to the voice lessons, such as breathing. In addition, we worked on vocal techniques with the entire group of PMEs, and a graduate teaching assistant provided extra voice lessons to the instrumental PMEs who requested more support. One instrumental PME reflected on the coaching from the graduate student and wrote, ‘Knowing how to sing with better technique is going to be healthier for me and easier for me to teach students in a healthier way’. Then, during the last lesson, this instrumental PME provided a vocal model for the secondary student. In his reflection, he described that the secondary student’s voice ‘was coming through his nose instead of through his mouth…I knew, like, oh, it sounds like you’re doing this. Try this instead. And, it was successful’. Some instrumental PMEs perceived successful experiences when they described or modelled a healthy vocal tone for the secondary students.

Secondary students’ contextualisation of pedagogical content knowledge

Data from the secondary students regarding the PME’s pedagogical content knowledge confirmed that the instrumental PME’s deficiency in this area led to perceived frustrations. For example, in the focus group, one secondary student shared how she felt when a PME critiqued her tone without explaining what she did wrong,

They got frustrated with me because I would like breathe somewhere…that was really frustrating… it challenged my patience…it was hard because I was doing like my very best to sing what I was supposed to, and I couldn’t. And they’re like – that’s wrong.

In our written comments to the PMEs, we asked them to provide specific feedback. In the focus group, one secondary student stated, ‘[They] helped me do like breath control…knowing when to like use all that breath…and they helped me…access that voice that I didn’t know I had’. In their final reflection, one secondary student wrote, ‘I feel really good! I’m learning so much…from relaxing and not using tension while singing to breathing and posture and testing my range’. Another secondary student shared, ‘I don’t normally have the resources to get myself personalised voice lessons or voice lessons at all besides school choir. So, it was really exciting to get to work with someone who could help me with my individual voice’. Although secondary students and PMEs cited specific challenges, they also perceived beneficial individual learning outcomes specific to their development as teachers and vocalists.

Discussion

We viewed this action research project as a process of continual feedback, reflection and action for all parties involved – each group learning from the other (Cain, Reference CAIN2012). For example, the PMEs served as researchers and participants, the secondary students contextualised the PMEs’ perceptions of the experience, and our own observations served as data and contributed to the feedback loop. In the findings section, we presented the PMEs’ perceptions of their teaching disposition, teaching skills and pedagogical content knowledge. Within each section, the secondary students’ perspectives contextualised the data from the PMEs. In this discussion, we will unpack these themes alongside related research.

Teaching dispositions

When examining perceptions of PME traits, Kelly (Reference KELLY2008) found that secondary students perceived rapport and relatability as important attributes for PMEs to possess. In addition, Hourigan and Scheib (Reference HOURIGAN and SCHEIB2009) found that PMEs valued opportunities to learn interpersonal skills, and researchers have suggested that music education curriculum integrate early authentic teaching experiences to help PMEs develop these skills (Cassidy, Reference CASSIDY1990; Conway, Reference CONWAY2002; Bartolome, Reference BARTOLOME2013; Johnson; Reference JOHNSON2014; Parker et al., Reference PARKER, BOND and POWELL2017). For example, Kruse (Reference KRUSE2012) found that secondary students observed when PMEs were uneasy in the classroom and treated the secondary students as young children rather than young adults. In this study, the secondary students did not perceive they were treated as children, but there existed stilted and awkward initial interactions among the secondary students and PMEs. In previous coursework, the PMEs had practised their interpersonal skills in front of peers and professors. These skills, however, did not necessarily transfer to this service-learning experience, possibly due to the age gap and small group teaching environment. During the first two lessons in this study, some PMEs cited inadequate interpersonal skills. As their teacher/student relationships developed during subsequent lessons, some PMEs and secondary students cited comfortable and natural interactions with one another.

Although researchers have found that PMEs appreciated quality feedback (Byo & Cassidy, Reference BYO and CASSIDY2005), the PMEs in our study expressed mixed feelings about receiving feedback on their teaching. For example, all of the instrumental PMEs shared that they appreciated critical and specific feedback, but three of the choral PMEs did not. This finding contradicts Finkelstein and Fishbach (Reference FINKELSTEIN and FISHBACH2012) who found a positive correlation between expertise and negative feedback – advanced individuals tended to seek out more critical feedback than beginners. Perhaps this unique finding is attributed to the leadership role the choral PMEs embodied during this experience – they supported the instrumental PMEs and maybe our critical feedback made them feel less effective as mentors.

Teaching skills

Researchers have found that engaging in self-reflection and consistent practice in primary and secondary settings can improve PMEs’ skills specific to content delivery and student-centred instruction (Cassidy, Reference CASSIDY1990; Reynolds & Conway, Reference REYNOLDS and CONWAY2003; Bartolome, Reference BARTOLOME2013; Forrester, Reference FORRESTER2019; VanDeusen, Reference VANDEUSEN2019). Initially, the PMEs focused on how they could improve their own teaching skills rather than respond to the secondary students’ musical needs, which Fuller (Reference FULLER1969) defined as ‘concern with self’, which presents in the early stages of teacher education verses ‘concern with pupils’ (p. 212), which presents as teachers gain experience (Miksza & Berg, Reference MIKSZA and BERG2013; Powell, Reference POWELL2016). Researchers have found that secondary students in music appreciated when PMEs offered suggestions for improvement (Kelly, Reference KELLY2008; Kruse, Reference KRUSE2012), and the secondary students in this study expressed frustration when they received critical feedback without specific recommendations from the PMEs. These challenges can conflict with the goal of service learning, which is to provide mutually beneficial experiences for all parties involved (Burton & Reynolds, Reference BURTON and REYNOLDS2009). In this study, the secondary students’ reflections allowed the PMEs to evaluate their teaching skills. By the final lessons, some secondary students reported that PMEs provided appropriate feedback and that they developed their vocal abilities as a result of the service-learning experience.

Pedagogical content knowledge

Early-career music educators have suggested that obtaining and applying pedagogical content knowledge in real-world teaching settings are essential when preparing for a career in music education (Ballantyne, Reference BALLANTYNE2006; Grieser & Hendricks, Reference GRIESER and HENDRICKS2018). In addition, music teacher educators have reported that mastering instrument-specific musical and pedagogical skills are crucial elements for successful music teaching and learning (Juntunen, Reference JUNTUNEN2014). The instrumental PMEs in this study cited a perceived lack of pedagogical content knowledge, specifically, knowledge of vocal anatomy and physiology needed to teach voice lessons to secondary students. Upon graduation, the PMEs in this study received a licence to teach music education in primary and secondary schools, and therefore, the programme requirements included instrumental and vocal pedagogy coursework for all music education students. The breadth of pedagogy studied can make mastery of the content difficult to achieve before graduation.

Researchers have also found that although PMEs might identify a lack of pedagogical content knowledge, they cannot always pinpoint specific issues (Madsen et al., Reference MADSEN, STANDLEY, BYO and CASSIDY1992). In this study, the PMEs could hear issues such as intonation, vowel placement, and a breathy tone quality, but they struggled to apply specific solutions to those problems and deferred to fixing musical errors. The PMEs improved when we encouraged a student-centred approach – such as asking the secondary students to describe what they were feeling and compare tone qualities when experimenting with vowel placement. In this action research study, a cycle of continuous and collaborative feedback may have contributed to the PMEs perceived development of their pedagogical content knowledge.

Implications and conclusion

Applying an action research methodology to service-learning experiences may allow researchers to examine how PMEs and secondary students perceive mutually beneficial learning experiences. Further, service-learning experiences can serve as ‘a catalyst for broader and deeper engagement with community partners’ (Rawlings, Reference RAWLINGS, Conway, Pellegrino, Stanley and West2020, p. 644). These shared experiences may develop solutions to problems within unique and context-specific learning environments.

In musical service-learning experiences, all parties have value and opportunities to learn. In this study, collaboration and feedback may have contributed to how the PMEs and secondary students perceived teaching/learning experiences. Although the PMEs valued positive and specific feedback, the dual roles of teacher/learner may have caused the choral PMEs to struggle with receiving critical feedback. Therefore, feedback should be nuanced and structured to support PMEs during service-learning experiences. For example, we suggest that feedback should be provided after PMEs participate in video reflection and should build off of their perceptions of the experience.

The transition from student to teacher can be difficult for undergraduate students to navigate, and researchers have reported that service-learning experiences may help develop undergraduate student teacher identities (Bartolome, Reference BARTOLOME2017; Forrester, Reference FORRESTER2019; Sindberg, Reference SINDBERG2020). In this study, the PMEs were not burdened with issues typically present in large ensemble classrooms, such as management and isolating musical and pedagogical errors within a group. The individual voice lessons also provided a unique experience for PMEs and secondary students to focus on their musical and interpersonal skills – providing opportunities for social and musical growth in a safe and small group environment.

Service-learning projects can create meaningful experiences to better prepare PMEs for careers in music education and create beneficial learning experiences for secondary students. We suggest that future researchers replicate this study with individual instrumental lessons taught by choral and instrumental PMEs to gather further evidence. To account for differences in prior music education coursework, as the choral PMEs in this study offered mentorship and content knowledge to the instrumental PMEs, instrumentalists could act as content area mentors for their choral peers. In addition, parent and administrator perceptions could uncover other aspects of service-learning experiences not yet known. Researchers could also conduct longitudinal studies to determine whether service-learning experiences influence secondary students’ decisions to study music education. We suggest that researchers interested in service learning also consider an action research methodology so that all parties can invest in student learning and in turn, their own development through a rigorous action research feedback loop (Cain, Reference CAIN2008). Examining service-learning experiences might allow for nuanced understandings into the multifaceted areas of student development and may provide opportunities for social and musical growth in primary, secondary and university classrooms.

Appendix A. Secondary student reflection questions

-

(1) Please describe any aspects from today’s lesson that you enjoyed.

-

(2) Please describe any aspects of today’s lesson that you did not enjoy.

-

(3) How did you feel about this lesson compared to your previous lesson?

-

(4) Please list any additional information you would like us to know.

Appendix B. Guided-written teaching reflection

Based on Rolfe et al.’s (Reference ROLFE, FRESHWATER and JASPER2001) What? So What? Now What? Framework for reflective writing, specific questions for the music classroom adapted from Rawlings et al. (Reference RAWLINGS, LARSEN and WEIMER2019).

Section 1: What?

Describe your teaching demonstration in terms of the following questions:

-

(1) How did the selected materials support the development of students’ understanding of the concept(s)?

-

(2) In what ways did the materials and/or activities account for students’ pre-existing knowledge? Age appropriate?

-

(3) In what ways and to what level of effectiveness were students musically and/or verbally engaged?

-

(4) What instructional strategies were used to improve the sound?

-

(5) Describe the nature and effectiveness of questioning techniques used in your lesson. Student-centred? Teacher-centred?

-

(6) Describe the ratio between student engagement and teacher delivery (student doing vs. teacher talking).

-

(7) Describe how you communicated with students including eye contact, vocal inflection and clarity of instructions.

-

(8) Describe your overall disposition such as energy, facial expression and interactions with students.

-

(9) Describe your feedback to students such as critical, positive, and specific.

Section Two: So What?

Address the following question:

-

(1) Why is what you wrote about teacher knowledge, skill and disposition important as you plan for future teaching presentations?

Section Three: Now What?

Address the following questions:

-

(1) How will what you learned from this teaching experience help you to plan and prepare for your next teaching experience?

-

(2) Which areas of teaching will you target (e.g., preparation, environment and instruction)? Why?

-

(3) How will you reach your goal?