Whether discussing production models, textual content or methods of audience participation and consumption, the period from the late 1960s to the late 1970s was a decade of turbulent change for Japanese popular music. Folk and rock of the late 1960s emerged from subversive political movements, and their negotiation of boundaries between authenticity and commercialism led to the discovery of alternative methods for music distribution outside the established record industry (Azami Reference Azami2004, pp. 171–5). At the same time, the integration of rhythms and sounds of European and American popular music to the Japanese language signified a revolution in musical expression (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, pp. 45–71; Satō Reference Satō2019, pp. 187–226). This resulted in a considerable diversification of musical styles in mainstream pop music by the mid-1970s, when the originally subversive trends were harnessed as commodified products and their rebellious instigators became contributors to the music industry that they initially opposed as overly commercial. This development was fostered by the recognition of popular songs as ‘legitimate culture’ (Nagahara Reference Nagahara2017, pp. 214–20) when Japanese society began to lean towards conformist middle-class society with values and tastes shared across the populace in the 1970s (Tsurumi Reference Tsurumi1984, pp. 108–38). The result – a fruitful convergence of different musical styles and modes of performance – was also a triumph for the music industry, which demonstrated success in commodifying even originally subversive trends.

This is a story that has already been told many times.Footnote 1 As the account above demonstrates, its trajectory bears a striking resemblance to the changes typically described in histories of European and American popular music. It also represents an intriguing interplay between music and society as a narrative of a society becoming middle class through a process spurred by economic growth that tamed the ‘noise’ (as conceptualised by Jacques Attali) of originally subversive musical genres. However, as in historiography in general, this form of representation entails a risk of excessive focus on dominant discourses; consequently, this can result in (albeit often indirectly) defining other developments as minor or marginal (Frith Reference Frith1996, pp. 15–6). This trend is most obvious in the case of subcultures but it extends even to what Kärjä (Reference Kärjä2006) calls ‘mainstream canons’. For example, solely emphasising social and musical developments of an explicitly subversive nature means that those with more implicit undertones go easily unnoticed as potential social change.

An example worthy of attention is the rise of female singer-songwriters in the 1970s. Following the successful debut albums of Itsuwa Mayumi (b. 1951) in 1972 and Yuming (Arai/Matsutōya Yumi, b. 1954) in 1973, the 1970s saw the emergence of dozens of young women who both wrote and performed their songs, including Nakajima Miyuki (b. 1952), Takeuchi Mariya (b. 1955), Yano Akiko (b. 1955) and Yagami Junko (b. 1958).Footnote 2 To be sure, there was nothing strikingly subversive about them on the surface; they typically did not write lyrics addressing political issues, nor did they claim to construct their authenticity based on anti-commercialism. Consequently, popular music historiography tends to focus on their extraordinary position in the music market as artists who were able to bridge the gap between commercial appeal and artistic quality. While this aspect is indeed worth noticing, it is the recognition of artistic quality itself that should attract more attention. After all, music histories tend to represent a masculine story that typically allows recognition of only a few female musicians (Reitsamer Reference Reitsamer, Baker, Strong, Istvandity and Cantillon2018, p. 27; Leonard Reference Leonard2007, pp. 26–30). Japan is no exception. When examined from this viewpoint, the emergence of female singer-songwriters appears as an extraordinary phenomenon with important musical and social implications.

The aim of this essay is to recognise these implications by discerning these female singer-songwriters from a gendered point of view. Such a task could obviously be approached from a variety of perspectives but I intend to focus on their position in music production, the media and historiography from a macro-level vantage point. I readily admit that this approach has its limitations; after all, this emphasis can easily neglect the importance of textual analysis (including the use of body and voice), music's role in everyday life and the importance of aesthetic experience (DeNora Reference DeNora2004). I believe, however, that these different approaches are complementary rather than separate lines of interpretation. Therefore, I want to consider this article as the first necessary step towards understanding Japanese female singer-songwriters of the 1970s as a phenomenon – one that will facilitate more detailed analysis of other aspects in the future.

From here on, I will refer to the musicians I study as ‘female singer-songwriters’ instead of using the more exhausting term, ‘Japanese female singer-songwriters of the 1970s’, but will naturally distinguish among them when necessary. ‘Female singer-songwriters’ do not, of course, constitute a genre: ‘we can't talk about women as … a subgroup of humanity that speaks with one voice’ (Greig Reference Greig and Whiteley1997, p. 168). Discussing female musicians as a uniform group entails a risk of suggesting female otherness and can end up both implying inferiority to men's music and reifying its supposed ‘neutrality’. McClary (Reference McClary2002, p. 19), for example, remarks that many women composers ‘insist on making their gender identities a nonissue’ precisely for this reason. Nevertheless, there are contexts in which discussing female musicians as a group is reasonable. As I shall emphasise in this essay, female singer-songwriters bore significance in both musical and social spheres by constituting a category distinguishable from previous female and male musicians. Therefore, they should be discussed together (cf. Kutulas Reference Kutulas2010; Lankford Reference Lankford2010; Nagai Reference Nagai2013).

Academic study of Japanese popular music has remained relatively marginal outside Japan but there are at least three reasons why these female singer-songwriters should be of transnational interest. First, obvious parallels with such female musicians as Carole King and Joni Mitchell position Japanese singer-songwriters as a part of an international continuum. Second, they provide one angle to the question of how women have negotiated their positions as creative musicians in different socio-cultural surroundings. Third, although Japanese popular music is primarily aimed at the domestic market, some of the female singer-songwriters have also appeared in international contexts. For example, Miyazaki Hayao has used Yuming's songs in his popular animations; Takeuchi Mariya's ‘Plastic Love’ (1984) became a global hit in 2018 owing to YouTube recommendations; and Chiaki Naomi's ‘Rouge’ (1977) written by Nakajima Miyuki has been covered in several languages, including Chinese, Thai and Finnish. Furthermore, Itsuwa Mayumi and Yano Akiko recorded their debut albums in the United States and have collaborated with such influential musicians as Carole King and Lyle David Mays. Therefore, although I discuss the female singer-songwriters in a Japanese context, several aspects about them should be of wider international interest.

My argumentation is informed especially by academic accounts of female musicians and creativity, including those by Citron (Reference Citron1993), McClary (Reference McClary2002), Warwick (Reference Warwick2007) and Whiteley (Reference Whiteley2000). All of their views are naturally not applicable to Japan as such, but as Mehl (Reference Mehl2012) has demonstrated, many of the gender discriminatory practices in Western music have been rooted in Japan since the late nineteenth century. To contextualise Japan-specific practices and gender expectations, I will refer to the feminist studies on Japan by Inoue (Reference Inoue1981; Reference Inoue2009), Shigematsu (Reference Shigematsu, Molony and Uno2005; Reference Shigematsu2012) and Ueno (Reference Ueno2009). By adapting Small's (Reference Small1998) concept of ‘musicking’, I also conceptualise the positive valuation of female singer-songwriters as a musical act reflecting and constructing social values. I shall begin by situating female singer-songwriters in Japanese music production and society of the 1970s. This serves as background against which I next examine female singer-songwriters from the viewpoint of issues typically pertaining to creative female musicians. After this, I conclude by suggesting the importance of examining these matters from the viewpoint of gender equality.

Locating female singer-songwriters in Japanese popular music of the 1970s

There is not enough space to explain all the peculiarities of Japanese production models of the 1970s here. As already suggested in the introduction, however, changes in the 1960s and 1970s bear many similarities to those in Europe and America especially related to concepts such as commercialism, authorship and authenticity. My emphasis here is on recognising the discourses related to these matters rather than agreeing or disagreeing with them (cf. Moore Reference Moore2002; Negus Reference Negus2011, p. 613). Even despite individual differences between female singer-songwriters, discerning their position in different production models serves as crucial background for understanding why they can be discussed together in the first place. This pertains especially to why they were able to debut in a production system that was dominated by men (Igarashi Reference Igarashi and Kitagawa1999).

A definition of a singer-songwriter involves several issues (Till Reference Till, Williams and Williams2016, pp. 291–5) but my viewpoint in this article intentionally remains at a general level: ‘singer-songwriter’ stands for a solo artist who (1) composes most of her music, (2) writes most of her lyrics and (3) performs (sings, in many cases self-accompanied on the piano or the guitar) these songs herself. This definition does not address other attributes often associated with singer-songwriters, such as notions of subjectivity, because such conceptualisations were not that prevalent in Japan. Above all, the female singer-songwriter is an author: someone who expresses herself through music but not necessarily in a manner that claims to reflect real experience. Drawing a line is, of course, often complicated. For example, although Ōta Hiromi (b. 1955) wrote some of her songs and often accompanied herself on the piano, she was not presented as a singer-songwriter in the media or marketed as such. In comparison, Iruka (b. 1950) did not write all of her music despite being recognised as a singer-songwriter; in fact, her most well-known song, ‘Nagoriyuki’ (Lingering Snow, 1975), is a cover. Therefore items 1 and 2 include the qualified ‘most’. For example, quite notably Iruka wrote most of her material in the 1970s, whereas Ōta did not.Footnote 3

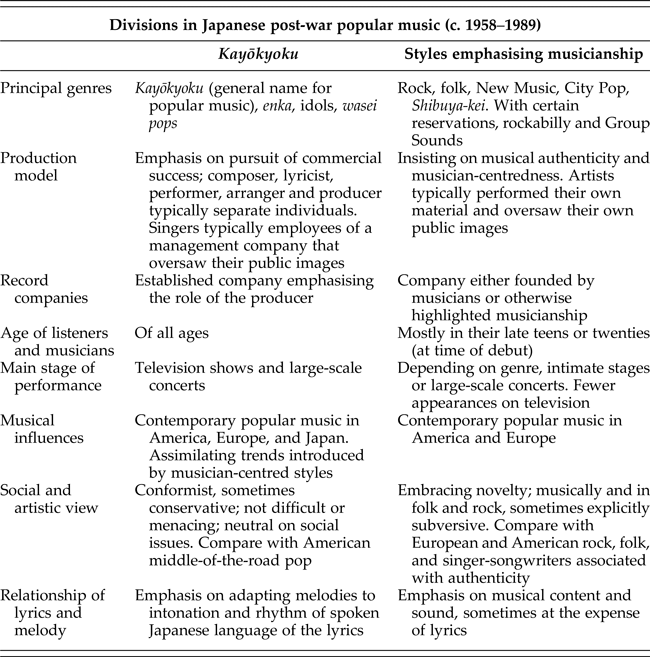

Generally, popular music production of the 1970s was characterised by a division to two different approaches: styles emphasising musicianship and authorship of one's own material, and those based on an ‘industrial’ process in which the musician had less authority in the production. The former comprised various genres by different names, whereas the latter is here called collectively kayōkyoku. Both are introduced in more detail in Table 1, which compares production models from the late 1950s when the first alternatives to older record companies emerged to the late 1980s when J-pop assimilated older genre names and production models.

Table 1 Adapted from Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2019, p. 279).

Table 1 presents the genres highlighting musicians’ authorship as a continuum rather than as separate music styles. There are musical differences between these genres (Kuji Reference Kuji1982, p. 35), but here I suggest continuity in the culture of production and discourses of musicianship. This conceptualisation is informed by the fact that many of those who debuted as folk singer-songwriters (such as Yoshida Takurō and Inoue Yōsui) were later recognised as New Music, whereas those who debuted in New Music were later labelled under City Pop. A factor enabling differences in production models is related to the record companies from which these musicians debuted. The originally underground nature of folk and rock of the 1960s spurred the foundation of musician-based companies, such as URC, Elec and later For Life Records, which offered an alternative to the established record industry (Azami Reference Azami2004, pp. 168–80). This resulted in musicians producing each other's albums and performing on them as studio musicians in a manner that prioritised the artist's wishes. The discourse of musicianship also pertained to authorship of one's material and precisely this aspect was considered as authenticity by musicians and fans alike (Bourdaghs Reference Bourdaghs2012, pp. 163–94).

In contrast with these genres is kayōkyoku. Today, the term kayōkyoku (or Shōwa kayō, ‘popular songs of the Shōwa period’ [1926–1989]) is used loosely to refer to post-war popular music before the appearance of J-pop at the end of the 1980s but in the 1970s it possessed a more specific meaning as a musical genre defined by its production model. Typically, kayōkyoku assimilated and commodified musical and sometimes habitual characteristics of styles emphasising musicianship while keeping to its production model that divided the roles of performers, songwriters, management and producers, giving the most authority to producers and management companies. Television shows formed an indispensable medium in the dissemination and standardisation of kayōkyoku (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, pp. 110–6). Although musically hybrid and flexible, kayōkyoku constituted a genre by its distinctive qualities in both production and textual content (cf. Holt Reference Holt2007). In practice, however, its boundaries with the genres emphasising musicianship were far from clear in terms of musical style and collaborators. This is because many of the artists emphasising their musicianship ended up working for the kayōkyoku industry as songwriters.

Of the genres emphasising musicianship, New Music (nyū myūjikku) is of particular interest here; so strong was the presence of female singer-songwriters in establishing the genre that discussion on it should also be understood as their origins.Footnote 4 Like kayōkyoku, New Music was a hybrid genre comprising different musical styles to the degree that it was often said to have brought down stylistic barriers (e.g. Aono Reference Aono1976, p. 125). Above all, it was distinguished by certain assertions related to production and the position of musicians as individual authors. While these assertions were grounded in earlier rock and folk, New Music differed from them in relation to its notion of commercialism. As in Europe and America, Japanese rock and folk musicians who ‘went commercial’ were originally criticised for betraying their audience. A fitting example is Yoshida Takurō, a singer-songwriter who became a teen idol marketed as ‘the prince of folk’ (fōku no purinsu), which resulted in fierce reactions from the original folk audience (Take Reference Take1999, p. 140). By the time that New Music emerged in the early 1970s, however, such criticism was no longer prevalent (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 46). An analogy with other countries perhaps helps to demonstrate its position. Whereas earlier singer-songwriters were like American folk singers or Italian ‘unprofessional’ female cantautori whose ‘“quality” and “honesty” … was untainted by commercial matters’ (Conti Reference Conti, Marc and Green2016, p. 40), those debuting in the 1970s were more like the ‘professional’ singer-songwriters openly sensitive to commercial success (Borshuk Reference Borshuk, Williams and Williams2016).

This emancipation of commercialism was inseparably intertwined with social developments. Affluence brought upon by seemingly unstoppable economic growth led to the image that Japan had become a uniform middle-class society, which calmed subversive movements and propelled the conception that all Japanese were equal in economic and cultural terms (Tsurumi Reference Tsurumi1984, pp. 108–38; Ivy Reference Ivy and Gordon1993, p. 241). This spurred a consumerist boom that was centred around commercial images of an urban, middle-class lifestyle – a phenomenon fostered by rapid urbanisation that also entailed significant changes in the lives and identities of contemporary Japanese (Okamoto Reference Okamoto, Karan and Stapleton2015; Aoyagi Reference Aoyagi2005, pp. 82–3).Footnote 5 New Music became a musical embodiment of these changes by emitting an aura of the cosmopolitan lifestyle one continuously encountered in commercial imagery aimed at the new middle-class audience. For example, Yuming (Matsutōya Reference Matsutōya1984, pp. 9–10) famously defined her music as ‘middle-class sound’ (chūsan kaikyū saundo), which was typically characterised as ‘stylish’ (oshare) and ‘urban’ (tokaiteki) (Yoshida Reference Yoshida1977; Sakai Reference Sakai2013). As a soundtrack for the urbanised lifestyle which presented consumption as a virtue, New Music did not assert its authenticity as anti-commercialism but instead distinguished itself from kayōkyoku by its celebration of individual creatorship. This carefully constructed image was aptly crystallised in a comment by a management company representative: ‘When kayōkyoku tops the charts it's thanks to the production organisation but in New Music it's all about the musician, including everything from the artist's sound and lyrics to philosophical aspects’ (Anonymous/Takeuchi Reference Anonymous/Takeuchi1981, p. 145).Footnote 6

Since the late 1960s, male singer-songwriters had constructed this distinction by avoiding appearances in contexts associated with kayōkyoku singers, especially in music shows on television. Female singer-songwriters inherited this strategy in their negotiation of their public images. For example, Yagami Junko described her position in the following terms: ‘So, I don't want to appear on television shows. If I was to appear with the kinds of celebrities that get applauded by screaming fans, my image will also be received that way. That would be inexcusable to long-time fans, wouldn't it?’ (in Anonymous/Yagami Reference Anonymous/Yagami1978, p. 172). Whereas Yagami speaks of ‘celebrities’ (tarento), Yuming negotiated her position even more clearly by referring to ‘singers’ (kashu): ‘You see, I'm not a singer. If I was a singer, there would be no meaning if I was not applauded by screaming fans, right?’ (Matsutōya Reference Matsutōya1984, pp. 31–2). In other words, both Yuming and Yagami portrayed themselves as authors rather than ‘mere performers’ who were more likely to be applauded as celebrities, not as musicians. As Stevens (Reference Stevens2008, pp. 49–50) has crystallised, the perceived difference between singer-songwriters and more visually presented kayōkyoku singers was that singer-songwriters spent more time in the studio and in concert halls than on television programmes. This even led to a momentary crisis of the ‘top 10’ music shows, as they could not claim to present the most popular Japanese singers anymore (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 114).

However, this romanticised notion of disinterest in the mass media is deceiving. While singer-songwriters certainly avoided appearing on kayōkyoku shows, their songs were constantly utilised in television dramas and commercials, both of which had an immense impact on record sales (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 71). Using again Yuming and Yagami as examples, Yuming's ‘Ano hi ni kaeritai’ (I Want to Return to that Day, 1975) became the best-selling single of 1975 as the theme song of the television drama Katei no himitsu (Family Secrets); similarly, Yagami's ‘Omoide wa utsukushisugite’ (Memories Are Too Beautiful, 1978) became a sales hit after having been used as the opening song for the music programme Cocky Pop, which sought to bridge the gap between kayōkyoku and New Music. Female singer-songwriters also wrote songs for kayōkyoku singers; in fact, the subsequent rise of ‘idols’ (aidoru) – young kayōkyoku singers ‘manufactured’ by their management companies to the minutest detail (Inamasu Reference Inamasu1989; Aoyagi Reference Aoyagi2005) – has even been attributed to the song-writing skills of female singer-songwriters such as Yuming, Takeuchi and Ozaki Amii (b. 1957) (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 155; Nagai Reference Nagai2013, p. 141). Furthermore, their interviews were typically published in such celebrity and fashion magazines as Myōjō, Heibon and Seventeen, which equally discussed kayōkyoku singers and other media personalities. Nevertheless, female singer-songwriters’ status on television was different from kayōkyoku singers and their interviews typically put a notable emphasis on music. From this position, they securely maintained their identities and images as creative musicians while also topping the sales charts as mainstream pop.

Of course, not everyone was identical in this respect. For example, although certainly keeping her distance to kayōkyoku production as a musician, Nakajima Miyuki emphasised feeling affinity with kayōkyoku itself: ‘I like kayōkyoku; I also often watch the television shows. I'm called a “singer-songwriter” but I don't own any folk or rock records. And I've never listened to Yuming’ (Anonymous/Nakajima Reference Anonymous/Nakajima1976, p. 174). Whereas Nakajima also stated that she did not regard her songs written for kayōkyoku singers as that different from her own songs (Anonymous/Nakajima Reference Anonymous/Nakajima1978, p. 120), Yuming even used the penname Kureta Karuho when writing kayōkyoku to distance herself from its productional context.Footnote 7 It may well be that Nakajima deliberately constructed her image as somewhat different from that of others (especially Yuming, who was often labelled her ‘rival’) but more importantly, her comments demonstrate that the recognition of kayōkyoku did not necessarily negatively affect one's position as an author.

This tendency became even more prevalent towards the end of the 1970s, when kayōkyoku production increasingly commodified the female singer-songwriter as a marketable concept. Those singer-songwriters who debuted as kayōkyoku artists did retain their authorship as songwriters but their management companies began to have increasingly more authority on their work. For example, it was not atypical that earlier singer-songwriters clung to their own vision as musicians even when arrangers tried to make their music more commercially attractive (Hagita Reference Hagita2018, p. 46), whereas in kayōkyoku the producer held the most power. This applied also to the constructions of public figures; singer-songwriter Kubota Saki (b. 1958), for example, was to be presented as a big star from the beginning (Hagita Reference Hagita2018, p. 53). Kayōkyoku singer-songwriters also began to appear on television shows, which meant increasing emphasis on the visual aspects of performance.

This was a natural development considering how kayōkyoku had successfully assimilated and commodified subversive trends before (Minamida Reference Minamida and Mitsui2014, p. 136). However, adhering to kayōkyoku practices had its downsides for many women. For example, although Takeuchi Mariya wished to perform as a singer-songwriter, the media was more concerned with her visual appearance and often presented her in a manner similar to kayōkyoku idols. Eventually, Takeuchi felt such a huge gap between her aspirations and media representations that she refrained from public performances and focused on writing songs for other singers for some time (Anonymous/Takeuchi Reference Anonymous/Takeuchi1981, p. 145; Take Reference Take1999, p. 180). Similar issues escalated in the 1980s. Okamura Takako (b. 1962) and Nakamura Ayumi (b. 1966), among others, had to find a balance between their own desires as musicians and those of their management, typically emphasising visual aspects (Take Reference Take1999, p. 250; Lehtonen Reference Lehtonen2019, pp. 460–3). Singer-songwriters becoming increasingly involved in kayōkyoku production raised doubts about their artistic integrity (Anonymous Reference Anonymous1978) and eventually marked the end of the authenticity associated with New Music in the early 1980s (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 155).

New Music, feminism and social subversion

As the discussion above demonstrates, female singer-songwriters did typically not write music addressing political issues nor were they considered as feminists. In the rare cases that subversion has been suggested in New Music, it has been located in a musical rather than societal context. In this, the image of female singer-songwriters resonates with Lankford's (Reference Lankford2010, p. 8) discussion of their foreign counterparts as introspective rather than political, thus perceived as safely conformist and non-subversive. However, concentrating solely on fixed definitions of subversion such as anti-commercialism or explicit commentary of societal issues leaves much unseen. As Kutulas (Reference Kutulas2010) and Shumway (Reference Shumway2014, pp. 148–74) demonstrate, there are several attributes that render American female singer-songwriters of the 1970s feministic, albeit not necessarily overtly so. This resonates strongly with their Japanese counterparts. After all, ‘music and its procedures operate as part of the political arena – not simply one of its more trivial reflections’ (McClary Reference McClary2002, p. 27). In other words, music always asserts something. This is typically recognised only when music explicitly breaks a taboo but there are also more subtle forms of subversion.

For example, a certain mode of subversion was inscribed to New Music itself. By originally declining appearances on kayōkyoku shows, singer-songwriters were, by extension, rebellious against the Japanese post-war paradigm of national homogeneity that was considered to penetrate all layers of Japanese society (Befu Reference Befu2001). In his discussion on the media representations of this paradigm, Tsurumi (Reference Tsurumi1984, pp. 121–3) notes that established television programmes at that time – especially the New Year's national music show Kōhaku utagassen (Red-White Song Contest) – substituted nationalistic symbols of the war era and contributed to the construction of new discourses of nationality by functioning as a musical representation of the homogeneity discourse. In other words, by boycotting music programmes on television, New Music also indirectly rebelled against the paradigm of national homogeneity.Footnote 8 This is especially apparent in the way New Music was originally seen as the opposite of enka – the genre that most explicitly asserted national homogeneity by its articulations of ‘Japaneseness’ (Yano Reference Yano2002; Wajima Reference Wajima2010).

Similarly, the concept of the female singer-songwriter itself and its assertions of authorship, creativity, and professionalism embodied political implications from a gender point of view (cf. Reitsamer Reference Reitsamer, Baker, Strong, Istvandity and Cantillon2018; Citron Reference Citron1993). These implications appear especially fascinating when examined in a broader socio-cultural context. The early 1970s saw the rise of a radical women's liberation movement (ūman ribu) and, in its wake, the emergence of more moderate discourses on improving women's social agency.Footnote 9 The subversive and action-oriented women's liberation movement was disillusioned by the male-centred and fundamentally patriarchal assertions of the social movements of the 1960s and formulated radical feminist theories to introduce a gendered viewpoint to global social inequality. It was also highly anti-establishment and sought to liberate women by fundamentally restructuring society rather than endorsing female participation in already existing social structures (Shigematsu Reference Shigematsu2012).

Although the more radical approaches of the women's liberation movement were even ridiculed in the media (Shigematsu Reference Shigematsu2012, p. 79), it nevertheless paved the way for the rise of more moderate organisations pursuing women's emancipation in the framework of existing social structures in such fields as workplace, media and education. The issues raised by these organisations had become prominent in the wake of economic growth and rapid urbanisation, both of which marked changes for the social position of women. Owing to urbanisation, the nuclear family gradually replaced the older tradition of three generations under one roof, which resulted in a considerable rise in the number of women in the workforce, yet their position remained weak compared with that of their male counterparts (Ochiai Reference Ochiai1996). This was due to the dominant paradigm that associated women's social duties with the private space (home) and men's duties with the public space (workplace) (Ueno Reference Ueno2009; Edwards Reference Edwards and Martinez2014). Since family was commonly regarded as the most important social unit, the expectation that women would be responsible for the domestic sphere was associated with national order under the ideal of ‘good wife, wise mother’ (ryōsai kenbo; Uno Reference Uno and Gordon1993). Consequently, women were strongly expected to leave their careers upon marriage or, at the latest, upon pregnancy, to be able to fulfil their social duties (e.g. Shiota Reference Shiota2000; Ochiai Reference Ochiai1996). This expectation resulted in discriminatory practices in work and education and was also apparent in the typical media representation of women primarily as mothers and (house)wives (Inoue Reference Inoue2009; Reference Inoue1981).

To tackle these issues, many feminist groups aimed to subvert the dominant paradigm by endorsing women's emancipation in the framework of existing structures. They were eventually successful in drawing attention to their goals: especially after the United Nations launched its Decade of Women in 1975, improving women's societal position became a largely recognised and debated issue in Japan (Mackie Reference Mackie2003, pp. 174–201). Consequently, feminism gained ascendancy in public discussion (Ehara Reference Ehara1993). For example, ‘soaring women’ (tonderu onna) was a slogan referring to women with a high level of social agency and freedom in a positive manner and became a buzzword of the 1970s. The positive image of female emancipation eventually fostered concrete social changes, such as the enaction of anti-discrimination laws.Footnote 10

After feminism had become a mainstream discourse, images of female emancipation were also adopted for commercial purposes. This development was, again, intertwined with urbanisation and economic growth. As both required women to adjust to new ideals of middle-class lifestyle in cities (Ueno Reference Ueno2009), the consumerist boom and its cultural products became instrumental in providing women with tools to manage this transition (Inoue Reference Inoue2009; Aoyagi Reference Aoyagi2005, pp. 82–3). With the rise of feminism, the commercial mass media began to present images of an urban and cosmopolitan lifestyle that associated women's social independence with the freedom of individual consumption (Shigematsu Reference Shigematsu, Molony and Uno2005, p. 564). Putting aside the fact that this trend quite notably compromised the anti-capitalist and anti-establishment assertions of the early women's liberation movement, the new image of women as individuals was nevertheless significant for women's emancipation at large in that it dissolved earlier media representations that had focused on women solely as mothers and housewives (Inoue Reference Inoue2009, p. 5).

This development directly relates to the discussion on New Music and female singer-songwriters. As they represented a commercial mode of production and did not explicitly address feminist issues in their songs, they certainly cannot be considered a musical embodiment of the radical women's liberation movement. However, female singer-songwriters do closely relate to the more moderate feminist discourses and their commercial representation as a concrete manifestation of ‘soaring women’. Since music forms an important arena for constructing, reflecting and negotiating gender roles (McClary Reference McClary2002), female singer-songwriters’ activities provided a concrete exemplar of women's social agency for the wider social sphere. This is also reflected in Yuming's later statement that she possibly represented ‘backstage women's liberation’ (misshitsu no ūman ribu) – a rare example of associating female singer-songwriters with women's movements (in Chikushi Reference Chikushi1984, p. 54). By thus closely linking with the social developments at large, female singer-songwriters’ emergence suggests much more than only the musical change with which they are more commonly associated.

Female singer-songwriters as ‘backstage women's liberation’

I shall next elaborate on the social significance of female singer-songwriters through the following five points:

(1) female agency in music production;

(2) successful negotiation of social expectations;

(3) positive valuation of female genius;

(4) social context of emergence; and

(5) position in historiography.

The nexus of these points best discloses why the emergence of female singer-songwriters should be considered a significant phenomenon in both musical and social spheres.

Female agency in music production

Prior to the 1970s, women's roles in popular music production were very limited. Exceedingly rare exceptions of successful female lyricists were Iwatani Tokiko (1916–2003) and Arima Mieko (1935–2019). Some songs composed by women do exist mostly just before the 1970s but these are notably few. Limited possibilities for female participation were related not only to song-writing but were also obvious in production and management (Igarashi Reference Igarashi and Kitagawa1999, pp. 84–5). One of the very few exceptions was producer Watanabe Misa (b. 1928), who co-founded the influential management company Watanabe Productions in 1959. However, Watanabe's position did not provide a general exemplar for promotion of female participation; it was only in the 1980s that women began to have a firmer foothold in production positions (Igarashi Reference Igarashi and Kitagawa1999).

In this context, it is remarkable that the emergence of female singer-songwriters also marked the large-scale introduction of female songwriters to Japanese popular music. By suggesting that this was significant, I do not want to reify the romantic notion of the ultimate authorship of a song belonging to its composer and lyricist (cf. Bentley Reference Bentley, Scotto, Smith and Brackett2018). Popular songs arise from a collaborative process (Frith Reference Frith1996, p. 240) and distinguishing their ‘author’ entails several complexities (Negus Reference Negus2011, pp. 608–9). For example, singers can possess an elevated level of perceived authorship even in cases where they have not participated in writing their songs (Negus Reference Negus2011, p. 619). In Japan, such examples of successful women would be Misora Hibari (1937–1989) and Fuji Keiko (1951–2013), both highly acclaimed enka singers with images strongly informed by their personal backgrounds. It does not matter that these images were at least partly constructed by their (male) producers, as was later revealed; their position was different from that of songwriters but can certainly be acknowledged as authorship (Tong Reference Tong2015).

However, I maintain that two aspects did significantly change with the emergence of female songwriters. The first one is textual: that women's own voices became widely heard in popular music. The second one is productional: that women became actively involved in music production. These two are intertwined in several ways and extend to the larger social sphere as a concrete promotion of female agency. It is in this context that the idea of the perceived author as composer-lyricist becomes relevant. Although Hoke (Reference Hoke and Pendle1991, pp. 258–9) justly draws attention to the fact that women have always excelled as singers, McClary (Reference McClary2002, p. 151) notes that while opera, for example, allows women to be presented as stars on the stage, the gendered discourses reinforced and constructed in libretti and music by men have resulted in offering up ‘the female as spectacle while guaranteeing that she will not step out of line’. Whether in opera or on a pop record, female performers are often presented as musicians who sing in the voice of a male-dominated production rather than their own (Warwick Reference Warwick2007, pp. 94–5).

For example, the history of kayōkyoku is full of examples of women singing about female emotions and desires that strongly suggest ideal ways of being a woman. However, these idealisations were virtually always written by male lyricists and typically represented a biased view of femininity. Although there were naturally exceptions to this rule, the quintessential portrayal focused on female characters devoting themselves completely to the men they love, thinking only about them, and crying over them (Zettsu Reference Zettsu2002 and Reference Zettsu2005; Take Reference Take1999, p. 168–9). By thus articulating the common view that women and men were incomplete without each other and, by extension, a family (Edwards Reference Edwards and Martinez2014), these portrayals effectively perpetuated the paradigm that confined women to the private space (Inoue Reference Inoue1981, pp. 110–21). It is easy to recognise that in its diminishing of female participation and agency, popular music reflected and reified general tendencies of Japanese society.

Thus, the involvement of female songwriters in music production represented concrete female agency previously unheard of in Japanese popular music. Although I here emphasise this as concrete social participation, several reasons speak for a more detailed textual analysis. Lyrics especially enable subtle articulations of both women's identity and agency in contexts previously dominated by men (Greig Reference Greig and Whiteley1997, p. 169; Warwick Reference Warwick2007, p. 112; Kutulas Reference Kutulas2010). Previous studies suggest that the side of female identification was especially important for listeners in the works of Yuming and Nakajima, who presented different aspects of womanhood: Yuming was described as ‘light and sophisticated’, while Nakajima was depicted as ‘dark and moody’ (Stevens Reference Stevens2008, p. 47; Kikuchi Reference Kikuchi2008, p. 248).

Although much more detailed analysis than can be presented here would be necessary to distinguish differences among different portrayals of women by female and male lyricists, previous writers have suggested such differences. Essayist Sakai Junko, for example, has elaborated on how remarkable it was for female listeners that Yuming diversified the portrayal of women in popular music by writing about women's experiences from a woman's point of view. In such songs as ‘Umi wo miteita gogo’ (The Afternoon I Watched the Sea, 1974), Yuming presented an image of a woman who refused to cry over her boyfriend even when facing a break-up with him. Sakai (Reference Sakai2013 pp. 26–9) interprets this as a statement articulating that women's happiness did not rely only on men or marriage and that it should be acceptable for women to think so. Another fitting example is ‘14banme no tsuki’ (Moon on the Fourteenth, 1976), in which the heroine anticipates what will happen after she has confessed her feelings to the person she secretly loves. Sakai (Reference Sakai2013, pp. 43–55) views this as a subtle negotiation of female agency, as it depicts a woman acting on her own will in a situation that was commonly thought of as calling for a man's initiative, showing boldness that is further emphasised by the energetic music. Hence, by contradicting the stereotypical portrayals of women, these songs also represented an alternative to common narratives about gender roles.

Furthermore, countless lyrics by female singer-songwriters include no reference to romance at all. For example, Itsuwa Mayumi's ‘Shōjo’ (Girl, 1972), Taniyama Hiroko's (b. 1956) ‘Gingakei wa yappari mawatteru’ (The Milky Way Keeps on Rotating, 1972) and Nakajima Miyuki's ‘Jidai’ (Era, 1975) depict women contemplating life and the flow of time, which again represents a very different portrayal of women from typical kayōkyoku lyrics (Shimazaki Reference Shimazaki2006; cf. Ochiai Reference Ochiai1996, p. 116). This is not to say that lyrics by female singer-songwriters would not occasionally have portrayed women in a manner similar to kayōkyoku representations but as Sakai (Reference Sakai2013, pp. 53–4) notes, even in these cases it was significant that the lyrics were written by women themselves as this rendered the adherence to social expectations a matter of women's own choice. Above all, by presenting women as desiring subjects rather than desired objects, female singer-songwriters provided their listeners with exemplars of womanhood previously unavailable in Japanese popular music and represented what Japanese feminist scholars dub as ‘women's culture’: culture made for women, typically by women (Inoue Reference Inoue2009, pp. 2–3; Shigematsu Reference Shigematsu, Molony and Uno2005, pp. 556–7).

Of course, understanding female listeners’ process of identification with female singer-songwriters would require more careful observance of fan experiences. Other equally important aspects to address would be differences in the use of voice and body between singer-songwriters and kayōkyoku singers. Naturally, the same also pertains to the act of composing; much more detailed analysis would be required to point out differences in musical portrayals of women by female and male composers or arrangers. Based on previous analyses, however, it seems that female singer-songwriters did exhibit musical versatility that was possibly gendered due to certain social expectations. Kikuchi (Reference Kikuchi2008, p. 248) notes that female singer-songwriters were typically not as insistent about clinging to a certain musical style as were male musicians before New Music. For example, Itsuwa Mayumi and Takeuchi Mariya declared genre definitions altogether needless (Anonymous/Itsuwa Reference Anonymous/Itsuwa1972, p. 189; Anonymous/Takeuchi Reference Anonymous/Takeuchi1978, p. 53). In this, women's music-making demonstrated flexibility that was possibly not available for male musicians. This tendency was also apparent outside Japan (Warwick Reference Warwick2007, p. 134; Kutulas Reference Kutulas2010, p. 696). It may well be that this hybridity was originally an expression of female identity; nevertheless, New Music eventually established a framework of flexibility also for male musicians, which is a concrete example of female singer-songwriters having an impact on Japanese popular music at large.

This impact became even more apparent when many women were requested to participate in writing songs for the kayōkyoku industry. In fact, the popularity of many idol singers produced by the kayōkyoku industry has been attributed to the song-writing skills of women in both academic and popular contexts precisely because of a perceived feminine aspect that they were able to introduce to kayōkyoku (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 155; Nagai Reference Nagai2013, p. 141). As the kayōkyoku industry had typically been conservative in its representation of women and its diminishing of female agency in music production, this change was especially important from a social viewpoint as it recognised women's creative skills. After singer-songwriters had demonstrated that music written by women could be commercially successful, the kayōkyoku industry soon began to commission songs from female composers and lyricists who were not originally performing musicians themselves. Eventually, their agency also extended to other aspects of production. For example, Yoshida Minako began producing the albums by younger female singer-songwriters and the first notably popular all-female groups, such as Princess Princess, Shonen Knife and Sugar, debuted in the early 1980s. Thus, by providing an exemplar of female agency, the appearance of female singer-songwriters initiated a momentous change in Japanese popular music (cf. Stanlaw Reference Stanlaw and Craig2000).

Successful negotiation of gendered social expectations and public recognition

‘Public recognition’ here refers to the volume of sales and media coverage; recognition as explicit positive valuation will be addressed below. Frith (Reference Frith1996, pp. 15–6) notes that the excessive emphasis on sales figures to define popularity easily leads to biased views of musical or social significance based solely on consumption. Nevertheless, sales figures can be important in that they embed societal implications. This is best explained with Small's (Reference Small1998) concept of musicking and the idea that music is an act that reflects, constructs and reaffirms social and cultural values. If we next adopt Sewell's (Reference Sewell, Bonnell, Hunt and Biernacki1999) conceptualisation of culture as a dialectic between system and practice, sales figures and wide media coverage (practice) demonstrate recognition of women as professional, creative individuals, which is reflective of social values (system).

This is especially notable in that the singer-songwriters’ audience was not biased in terms of gender; based on contemporary media coverage, their fans included women and men alike. Rather than by gender, the audience was divided by age but precisely the fact that young listeners supported female singer-songwriters reflected a shift in social values (Take Reference Take1999, p. 170; Yoshida Reference Yoshida1977). This is because public recognition, defined in these terms, entails the acknowledgement of female professionalism. The concept of ‘professionalism’ typically embeds several issues for female musicians because of social expectations that discourage women's creativity (Citron Reference Citron1993, pp. 84–7; Whiteley Reference Whiteley2000; Warwick Reference Warwick2007). However, with women singer-songwriters, the stigmas of female professionalism became almost a non-issue. This was demonstrated not only in their successful careers but also in boastful statements such as Yuming proclaiming herself a genius (Matsutōya Reference Matsutōya1984, p. 7) or Yano Akiko stating that she hates those who do not buy her records or come to her concerts (Anonymous/Yano Reference Anonymous/Yano1977, p. 51). Both are notably strong statements in a culture that regards modesty as a virtue, especially for women, and demonstrate success in negotiating gendered social expectations.

It should be noted here that female singer-songwriters were still subject to certain expectations and constraints specific to women. For example, their outward appearances were frequently commented upon in the media – even in articles that otherwise celebrated their creativity. One article about Yagami Junko praised her musical skill but also compared her looks with those of a ‘yam’ (Anonymous/Yagami Reference Anonymous/Yagami1978, p. 172). Bourdaghs (Reference Bourdaghs2012, p. 185) describes how he was repeatedly told that Yuming is popular ‘despite not being beautiful’. Another expectation specific to women is related to marriage and motherhood. This is a universal expectation (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997, p. 48), but as discussed above, it was a particularly strong one in contemporary Japan and was clearly recognised by female singer-songwriters. For example, Yuming initially declared her musical career over and focused on being a housewife after getting married in 1976 (Matsutōya Reference Matsutōya1984, pp. 121–2) and Yagami stated that she would get married at 25 and then make music only as a hobby as she ‘would not be able to manage both’ (in Anonymous/Yagami Reference Anonymous/Yagami1979, p. 88). As in the history of creative female musicians in general (Citron Reference Citron1993, p. 84–5), social expectations clearly also posed a contradiction to female professionalism in Japan of the 1970s.

Nevertheless, female singer-songwriters ultimately managed to negotiate a position different from most female kayōkyoku singers, who more typically adhered to social expectations related to motherhood and career.Footnote 11 First, this is apparent in the construction of their authenticity by declining to be presented as visual objects in kayōkyoku programmes. Of course, live performances did present them on the stage visually but also in this context, singer-songwriters were able to articulate their contempt if valuated as something else than musicians. For example, Yagami Junko emphasised how she wished the audience to concentrate on listening to her music rather than screaming her name in awe (in Anonymous/Yagami Reference Anonymous/Yagami1979, p. 88). Furthermore, the visual presentation of kayōkyoku singers entailed regulated bodily movements dictated by male producers (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 130–3). Declining from such fixed modes of visual presentation, authorship in New Music also entailed the female singer-songwriter's agency over her body – and by extension, the bodies of the women who listened to her (cf. Warwick Reference Warwick2007, pp. 56–64). Second, singer-songwriters were eventually able to defy the expectation of women to leave their careers upon marriage and childbearing. For example, Yuming became tired of being a housewife and soon returned to recording and performing to even much more success than before; in contrast, Takeuchi Mariya focused on writing songs for kayōkyoku singers while staying at home taking care of her child (Kamidate Reference Kamidate2019, pp. 112–3). There are countless examples of female singer-songwriters who have successfully continued their careers despite social expectations. Many of them are active and highly popular musicians today, having celebrated their fortieth anniversary as singer-songwriters in the 2010s.Footnote 12

Important here is not only the fact that this kind of negotiation took place, but also that the continuing popularity of these female musicians even after marriage and childbearing demonstrates acceptance of their roles as both professional female individuals and mothers/wives. In other words, public recognition shows that their negotiation succeeded. This made female singer-songwriters a concrete manifestation of the change that movements seeking female emancipation in Japan strived for.

Positive valuation of female genius

Naturally, one can still argue that the type of public recognition witnessed in popularity does not necessarily equal the celebration of women's creative skill. As popular music is typically known through performers rather than songwriters, it is hypothetically possible to ignore the ‘songwriter’ and focus solely on the ‘singer’, in which case singer-songwriters would not appear as that different from kayōkyoku singers. However, the focus solely on performance is easily countered with the fact that the song-writing skills of female singer-songwriters were specifically celebrated for their novelty: their creativity was not only acknowledged but also evaluated positively. Although this concerned many female singer-songwriters, it is best exemplified by discussing Yuming.Footnote 13 This is because she is commonly considered a pioneer who established the category of female singer-songwriter in Japan. Various influential figures, ranging from folk singer-songwriter Yoshida Takurō to classical composer and popular essayist Dan Ikuma, praised her work as something entirely different from anything that had been done before (see Take Reference Take1999, p. 171). Dan even located Yuming's work in a tradition of modern Japanese vocal music that was constructed by and centred around male composers by noting that her songs ‘contained a leap from older, overly sentimental songs – one that past Japanese composers … were unable to achieve’ (Dan Reference Dan1977, p. 4).

This kind of praise is significant in the context of gender, as especially young women have typically not been expected to partake in ‘serious’ music, which has been presented exclusively as a domain of male artists (Reitsamer Reference Reitsamer, Baker, Strong, Istvandity and Cantillon2018, p. 217; Warwick Reference Warwick2007, pp. 2–7). Consequently, the emphasis on masculinity as ‘serious’ has encouraged women to try to be like men as ‘honorary males’ rather than negotiate their identities as creative female individuals (Whiteley Reference Whiteley2000, p. 76; cf. Ochiai Reference Ochiai1996, p. 89). The valuation of masculine over feminine is apparent also in discussion on musical style and sound. Although it would be essentialist to claim any music as ‘feminine’ based on its composer's gender, musical style and sound are perceived and evaluated in gendered terms (Thompson Reference Thompson and Bull2019; Leonard Reference Leonard2007, pp. 96–8). One is typically able to intuitively distinguish between ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ styles of music; for example, soft and high sounds are characterised as ‘feminine’ as opposed to powerful and aggressive ‘masculine’ idioms (Warwick Reference Warwick2007, p. 6).

In this context, it is significant that Japanese female singer-songwriters were recognised as both feminine and artistically serious (compare with Carole King's brand of soft rock; Hoke Reference Hoke and Pendle1991, p. 269). The origins of New Music are often attributed to Yuming because her musical style was recognised as novel (Ogawa Reference Ogawa1988, p. 51). I want to argue that this perceived novelty was, in fact, related to gender. Consider, for example, ‘Hikōkigumo’ (Vapor Trail, 1973) from Yuming's debut album of the same name – a song which is familiar to many for its use in Miyazaki Hayao's animation The Wind Rises (2013). Instead of the masculine electric guitar, the music emphasises the piano and keyboard and Yuming's clear singing voice. However, by drawing from both Procol Harum's ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ and J.S. Bach's Aria from the third orchestral suite in D major (BWV 1068) and by applying unconventional chord progressions in the chorus, the song created an aura of artistic ambition. This kind of seriousness was previously associated virtually solely with male rock and appealed to contemporary audiences and critics alike (Take Reference Take1999, p. 171; Bourdaghs Reference Bourdaghs2012, p. 182; Yanagisawa Reference Yanagisawa2011, p. 200). The image of artistic ambition was further enhanced by the lyrics. Instead of describing romance, which had been the most common theme for women singers, ‘Hikōkigumo’ was a song about death, possibly suicide (Matsutoya 1984, pp. 81–3). However, unlike the relatively straightforward depictions of social issues by male singer-songwriters, Yuming's version was more sophisticated: the lyrics describe a young person climbing up a white slope all the way up to the sky, where her life becomes a ‘vapor trail’. In addition, the calm and reassuring atmosphere of the music seems to conflict with the conspicuously serious theme, creating an intriguing contrast open to interpretation (Bourdaghs Reference Bourdaghs2012, pp. 181–2).

‘Hikōkigumo’ was a significant song in defining Yuming's signature style and setting the standards of women's New Music as a genre that negotiated the boundaries between commercialism and artistic integrity while representing a recognisably feminine idiom. This came to characterise female singer-songwriters in general. Not only the higher singing voices but also the emphasis on the piano, keyboards and acoustic rather than electric guitar differs from more masculine idioms. This concerns also the emphasis on melody and sensitive lyrics. In other words, the valuation of their music bore social significance by acknowledging the genius of female musicians. By establishing their own musical idiom, Yuming and other female singer-songwriters succeeded in articulating that women's music was indeed artistic and serious.

Social context of emergence

Considering the magnitude of the shift described in the previous three items, it was a notably sudden one. The almost simultaneous appearance of dozens of female singer-songwriters during the early 1970s suggests that it cannot be explained as a mere coincidence or attributed solely to the recognition of the skills of certain talented individuals who happened to debut approximately at the same time. Rather, it implies wider social changes.

Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu and Johnson1993) has famously described the ‘field’ (champ) of cultural production in terms that put more emphasis on recognising the rise of a genius in social structures that enable their appearance rather than adhering to objective aesthetic quality embodied in a genius's work. Equally famously, Bourdieu (and other sociologists) has been criticised for being excessively fixed on structures and not considering aesthetic valuation and pleasure related to music (DeNora Reference DeNora2004). Like many others, I advocate recognising both aspects but will in this section focus on the structural ones. As already noted, female singer-songwriters were able to draw a response from a wide audience but that they were able to debut in the first place naturally required structures supportive of their artistry. In Japan of the 1970s, we can distinguish two as especially prominent: those taking place in music production and those taking place on a wider societal level.

Let us first approach the matter from the viewpoint of production. In the history of Western popular music, possibilities have been open to creative women especially in contexts actively supporting women's emancipation (Hoke Reference Hoke and Pendle1991, pp. 278–9; Bayton Reference Bayton1998, p. 190). The concept of female singer-songwriter eventually provided such a context in Japan, especially from the mid-1970s onwards. Before that, however, the production model emphasising musicianship – or in Bordieuan terms, authorship as cultural capital – was a focal factor. More precisely, this pertained to the discourse of authenticity, which formulated with the emergence of political male singer-songwriters of the late 1960s (Azami Reference Azami2004, pp. 167–9). Although mainstream folk eventually turned openly commercial and arguably conformist, the difference remaining with kayōkyoku was that it still celebrated the creative authorship of the musician (Bourdaghs Reference Bourdaghs2012, pp. 163–94). This paradigm enabled the type of subtly implied subversion embedded in New Music, but even more importantly, the founding of new record companies by male singer-songwriters resulted in the formation of a field in which the celebration of authorship was more relevant than the author's gender. In other words, the rise of New Music was, by extension, enabled by the politically radical movements of the late 1960s. This is highly ironic considering that the subversive movements fiercely opposed any notions of commercialism only a few years before Yuming's debut but it also contextualises New Music and female singer-songwriters in a politically engaged continuum.

Another important structure was formed by music competitions promoting musicianship, of which particularly the Yamaha Popular Song Contest or ‘Popcon’ is worth mentioning for its national prominence. Popcon, which was organised from 1969 to 1986, presented mostly young amateur performers pursuing a musical career. The winner received a recording contract and was able to enter as Japan's representative in the international World Popular Song Festival (also organised by Yamaha). Thus, Popcon provided a site on which to express one's creativity presumably detached from ideals of female performers imposed by older production models. The significance of the competition for female musicians is reflected in the large number of female singer-songwriters who made their debut in the competition.Footnote 14

However, the existence of structures supportive of musicianship does not necessarily mean equal support to women and men. After all, female creativity has constantly been downplayed based on claims of ‘objective musical quality’ defined in male-dominated contexts (Reitsamer Reference Reitsamer, Baker, Strong, Istvandity and Cantillon2018; Citron Reference Citron1993). Considering that music does not merely passively reflect society but also ‘serves as a public forum within which various models of gender organisation … are asserted, adopted, contested, and negotiated’ (McClary Reference McClary2002, p. 7), it seems particularly intriguing that the female singer-songwriters’ debuts coincided with the rise of discourses pursuing female emancipation. This social context also forms an apparent parallel with similar developments in other parts of the world: several studies suggest that an interplay between music and women's movements fostered the emergence of influential female singer-songwriters in America and Europe in the 1970s.Footnote 15 A development of this kind is naturally always a complex amalgam of various layers of social, aesthetic, cultural and productional factors. As such, it is best conceptualised as a reciprocal process based on Small's (Reference Small1998) and McClary's (Reference McClary2002) theories. When music is examined as an act that both constructs and reflects social values, the previous items suggest that the rise of female singer-songwriters embodied women's emancipation in a dynamic interplay with the wider social sphere in Japan.

An interesting question here is the extent to which foreign exemplars informed the images and possibilities for musical activities for Japanese singer-songwriters. After all, it is usually important to female musicians (whether composers or performers) to have an example with whom to identify (Citron Reference Citron1993, pp. 54–79; Whiteley Reference Whiteley2000, p. 9). Since the histories of popular music represent a masculine story, however, such examples are notably few. In Japan, the first female singer-songwriters naturally constructed a framework on which later female musicians were able to build their careers (Nagai Reference Nagai2013, pp. 5–42). This concerned especially Yuming, whose recognition was apparent in that promising younger female singer-songwriters were typically referred to as ‘the second Yuming’ or otherwise compared with her. Nevertheless, the question arises: did the first singer-songwriters have an example with which they could identify or did they really ‘start from nothing’, as popular music histories tend to claim (Take Reference Take1999, p. 169)?

Generally, it would be a simplification to view Japanese female singer-songwriters as only emulating their foreign counterparts. Popular music in Asia has its own practices and discourses (Weintraub & Barendregt Reference Weintraub and Barendregt2017) and the process of assimilating and rejecting foreign influences, negotiating identities and constructing new meaning in a local context was much more complex than simply adhering to a one-sided stream of direct influences. To examine this matter, let us first consider the views of the singer-songwriters themselves. Many of them have reported that rather than searching for models among female singer-songwriters, they found their inspiration originated from male musicians in Europe and America (e.g. Itsuwa Reference Itsuwa1978, p. 29; Anonymous/Takeuchi Reference Anonymous, Takeuchi1979, p. 49; Matsutōya Reference Matsutōya1984, p. 91). Takeuchi Mariya even wrote the song ‘Mājii biito de utawasete’ (Make Me Sing in the Mersey Beat, 1984) about her love of the Beatles, whereas Itsuwa Mayumi (Reference Itsuwa1978, p. 47) later reminisced that she did not originally wish for Carole King to perform on her debut album as she felt that King's music was so different from hers. Furthermore, Itsuwa stated her dislike of her record being marketed with King's name (in Anonymous/Itsuwa Reference Anonymous/Itsuwa1979, p. 214).

Of course, it is perfectly possible that these statements were simply a strategy of insisting on artistic originality – an aspect that, after all, legitimated the very existence of the singer-songwriter. At the same time, however, these comments also demonstrate the female singer-songwriters’ wish to negotiate their position as musicians who sought to create something novel and recognisably feminine inspired by foreign (male) musicians. After all, the type of female identification that has been suggested in the lyrics of Yuming and Nakajima (Kikuchi Reference Kikuchi2008, p. 248; Shimazaki Reference Shimazaki2006) was unavoidably different from their foreign counterparts: it took place in the context of Japanese discourses of women and femininity and in the Japanese language. In this respect, female singer-songwriters were successful in constructing their images differently from previous female and male musicians, whether Japanese or foreign.

Although Japanese female singer-songwriters possibly did not recognise (or, at least, admit) influence from their foreign counterparts, their production most certainly did. An important exemplar here is, perhaps unsurprisingly, Carole King. For instance, Yuming's producer Murai Kunihiko visited the United States in the early 1970s, witnessed the popularity of female singer-songwriters in America and attended King's studio sessions (Matsuki Reference Matsuki2016, pp. 104–6). After this, he wanted to make Yuming the ‘Japanese Carole King’ and produced her debut album (see Chikushi Reference Chikushi1984, p. 202). Furthermore, Itsuwa's debut album Shōjo was recorded in the United States, where King, who had been impressed by Itsuwa's demo tape, participated in the recording. That a young Japanese woman had such an influential American musician playing on her debut album was unheard of in Japan and attracted notable media attention (Anonymous/Itsuwa Reference Anonymous/Itsuwa1979, p. 214), which naturally also contributed to the recognition of the female singer-songwriter as a category.

Thus, it is likely that especially American exemplars did facilitate the recognition of female singer-songwriters in Japan. There was nothing new in such a process; Japan has deliberately consulted other cultures for new cultural capital throughout its history and since the mid-nineteenth century, examples have been sought especially in Europe and the United States (a process described in Starrs Reference Starrs2011). The practices of popular music were largely built on Anglo-American examples; for example, the discourse of singer-songwriters’ authenticity and authorship was adopted from America (cf. Bentley Reference Bentley, Scotto, Smith and Brackett2018). Similarly, the initiative to employ more women in management positions in the Japanese music industry came from foreign record companies in the late 1980s (Igarashi Reference Igarashi and Kitagawa1999, p. 88). There is also a tendency for Japanese artists to become nationally recognised only after international validation. For example, art music composer Takemitsu Tōru (1930–1996) was famously belittled by older composers and music critics in Japan until Stravinsky praised his work. Therefore, it is only natural that Itsuwa and later Yano received notable media attention and recognition for having recorded their debut albums in America with well-known musicians such as Carole King, David Campbell and Chris Darrow (Itsuwa's album Shōjo), and members of Little Feat (Yano's album JAPANESE GIRL).

With these remarks, I do not intend to undermine the role of the first female singer-songwriters as pioneering figures, nor do I seek to deny the originality of their work. Rather, in my opinion, these observations present an intriguing transnational aspect to the exchange of influences between the Japan and other countries. This may be conceptualised as a process of cultural vernacularisation, or the ‘extraction of ideas and practices from the universal sphere … and their translation into ideas and practices that resonate with the values and ways of doing things in local contexts’ (Merry & Levitt Reference Merry, Levitt and Hopgood2017, p. 213). By writing new songs specifically aimed at a Japanese audience, female singer-songwriters maintained a level of distance from their foreign counterparts while still representing the same, internationally recognised category. In other words, regardless of possible exemplars, they were successful in establishing a new tradition of female musicians in Japanese popular music: it was one that bore specific social and musical meaning in its own social context. Through this process, female singer-songwriters in Japan provided an exemplar not only for individual musicians but also for the music industry and society at large.

Position in historiography

I wish to emphasise again that it is crucial to understand the nexus of the four items presented above as a whole. They are interrelated in demonstrating the social implications embedded in the concept of female singer-songwriters during the 1970s. While the discussion above emphasises their positive valuation in the 1970s, however, this kind of valuation does not necessarily extend to subsequent views. Finally, I would briefly like to address their position in music history from the viewpoint of canonisation.

Canonisation has been assessed in relation not only to Western art music but also to other types of music that have their established ways of emphasising influential works and individuals. Regardless of musical style, the categories that make up canons tend to exclude women (e.g. Schmutz Reference Schmutz, Baker, Strong, Istvandity and Cantillon2018; Leonard Reference Leonard2007, pp. 26–30; Citron Reference Citron1993). Bayton (Reference Bayton1998, p. 23), for example, notes how relatively few performers are female. Even these few have often been excluded from music histories, unless they have become recognised as stars. Social structures have typically discouraged women's participation in public music production but as even highly creative women have tended to be excluded from music histories, it is not an adequate explanation of the issue.

This also concerns Japanese music. Star performers, composers, lyricists and producers have been discussed above in relation to authorship and agency in popular music but the same issue concerns other types of musics as well. Female musicians have always existed in Japan, and in certain contexts, they have even had an influential role in music history despite social restrictions yet these roles are typically downplayed in historiography (Coaldrake Reference Coaldrake1997; Mehl Reference Mehl2012). To overcome the issue, Marcia J. Citron introduces two approaches to canonising women's music. The first, ‘mainstreaming’, suggests introducing more women to an already existing (male-dominated) canon, whereas the second, ‘separatism’, favours constructing an altogether new canon that does not support patriarchal modes of thought embedded in existing ones. The two approaches are not necessarily exclusive but can be thought of as a continuum (Citron Reference Citron1993, pp. 219–20).

Whichever viewpoint we adopt, examination of Japanese popular music histories demonstrates that female singer-songwriters are largely canonised music history. While there are also examples of accounts that only mention a few individuals of a star status, a considerable number of histories recognise female singer-songwriters as a distinct group of performers who have significantly impacted Japanese popular music history.Footnote 16 This demonstrates that their negotiation of female agency eventually succeeded in a manner that surpassed their own temporal and musical context.

Conclusion: female singer-songwriters, popular music and gender equality

The three main points of this essay may be summarised as follows. First, the rise of the female singer-songwriters in the 1970s marked the first time in Japanese popular music that female musicians were widely recognised and valued as creative artists. Both their concrete agency in music production and the positive reception of their work imply a change in value systems concerning gender roles. Second, by initiating a new era in which women's own voices were being heard in Japanese popular music, female singer-songwriters also embodied the wider pursuit for female emancipation at that time. Third, their emergence was indirectly enabled by subversive movements of the previous decade, and later spurred by the consumerist boom and the ideals of a middle-class society in the 1970s, making them a part of a larger continuum of social and musical change. Therefore, although the genre name ‘New Music’ was coined to refer to the work of singer-songwriters who introduced a new, stylish sound to Japanese popular music and embraced commercialism while not compromising artistic originality, I want to argue that the effective ‘new-ness’ of the genre was ultimately about social change in Japan. As female singer-songwriters conspicuously differed from the previous dominant image of the serious author as a male, the ‘new’ in New Music may also be conceptualised as the emancipation of women musicians in Japanese popular music. And, as we have seen, this aspect of its newness eventually inspired the audiences, music industry and other musicians alike in a manner that goes well beyond the contexts of authorship and originality in popular music.

As stated in the introduction, however, these observations are above all important for forming an understanding of the macro-level significance of the female singer-songwriters. To point out more detailed aspects of the complex and dynamic interplay between their activities and social developments, these observations call for further analyses of their music, audiences and the extent of women's identification with their work. This also concerns the possible limitations to their impact. Although this essay has focused solely on the social progress that the emergence of female singer-songwriters embodied in the 1970s and demonstrated that they became canonised music history, it is equally important to address the subsequent developments of women's agency in Japanese popular music and society. Despite the popularity of feminism in the 1970s, Japan has later gained adverse attention for gender equality issues. For example, the country scored as the lowest industrial nation in the Global Gender Gap Report of the World Economic Forum for several consecutive years in the 2010s.Footnote 17 At the same time, gender equality in Japan is again becoming an increasingly debated topic.

In the context of promoting female agency today, it is crucial to understand in which kinds of circumstances female agency has thrived before and which kinds it has been diminished. As suggested in this article, the rise of the female singer-songwriters required certain social and musical conditions as well as external influence, the convergence of which not only led to music that inspired audiences but also provided exemplars for other female musicians and, by extension, for the Japanese society at large. Understanding the magnitude of the change, as well as its catalysts and subsequent shortcomings, contributes not only to a more profound understanding of music history but also to social change.