The topic of this presidential address reflects the theme of this year's annual conference: Diversity and the Discipline of Political Science. I am not the first to speak to this subject. Nor, as a straight, cis, white, middle-class woman, am I perhaps the best person to address the complexity that is embedded in the concept of diversity. Nonetheless, my intention is to use this address to highlight the status of diversity within the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA). In doing so, I will draw attention to who are present and who are absent as members of our discipline, where diverse members are located in the discipline and what changes have occurred in our membership over time. Furthermore, I will address what we study in our discipline, how that focus can be exclusionary and the extent to which new areas of research have been successful in breaching the siloed boundaries of political science. This is followed by a discussion of how we study these questions and how methodological prejudices can inhibit diversity in our field. Finally, I will speak to why these questions and their answers are of importance to us as political scientists in the twenty-first century. Not surprisingly, I will argue that the discipline of political science has changed dramatically over the past few decades but we still have much work to do to meet the goals of equity, diversity, inclusion and decolonization.

The theme of the 2021 annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association was chosen for several reasons. First, events in recent years have highlighted the issues of equity, diversity, inclusion and decolonization (EDID) both within and without the academy. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, the responses to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the increase in incidents of anti-Asian racism, and the she-cession and unbalanced workloads due to the COVID-19 pandemic that have set women back decades have placed the questions of EDID at the front of the policy agenda. Other factors such as the recent 10-year anniversary of the Race, Ethnicity, Indigenous Peoples and Politics section of the CPSA, concerns about racial profiling at past congresses or the release of the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences’ Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization report (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Golfman, Battiste, Crichlow, Dolmage, Glanfield, Malacrida and Villeneuve2021) provide even more reason to reflect on where we are and where we have come from as a discipline.

Topics of equity and diversity are ones that have long interested me as a female political scientist focused on questions of participation and representation. I have always been one of those researchers seeking to understand the who, where, what, how and whys of political activity, and so I feel it is appropriate for me to ask these questions of our discipline to help us understand how we fare in terms of EDID. I recognize that many others have asked these questions over the years and that in many cases they may be better placed to address them. I am very conscious of my place of privilege in the academy and acknowledge that my own experiences in political science are very different from those of younger generations of scholars who may be queer, nonbinary, Indigenous, racialized, or who may take a more critical approach or use less quantitative methods in their research. This paper is therefore as much about challenging myself as it is challenging others in our field to be more inclusive and take diversity more seriously in our departments, in our scholarship and in our openness to the research questions and approaches of those with different backgrounds and experiences.

Diversity in Personnel

Let me begin by discussing the issue of diversity in the personnel in the discipline of political science. Standing here as the outgoing president of the Canadian Political Science Association, the second of three women in a row, would have been hard to imagine 30 years ago when I first started to attend our annual conferences. Our student body and professoriate have certainly changed since then. Yet I, my predecessor, and my successor are not that different from one another, nor are we different (other than our mother tongue) from the men who preceded or are likely to succeed us. We are different, however, from many of the students—graduate and undergraduate—in our programs today, and we are different from many of the young scholars coming onto the job market trying to fit into a discipline that is still not very welcoming.

For much of its history, diversity in the CPSA has been understood as the attention to the difference between English and French Canada (Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban2016; Rocher, Reference Rocher2007; Wilson, Reference Wilson1993). However, at points over the past 50 years, the Canadian Political Science Association has undertaken to go beyond the representation of English or French in its membership “to study biases in the Canadian society which might be reflected in the structure of the profession of political science” (Committee on the Profile of the Profession, 1973: 1). The first Bias Committee (later changed to the Study of the Profile of the Profession Committee) was led by Pauline Jewett (Carleton University) and established by the CPSA Board of Directors in 1972. Ten years later, Janine Brodie (York University) was appointed chair of a follow-up committee, along with Caroline Andrew (University of Ottawa) and David Rayside (University of Toronto). The Committee on the Profile of the Profession was specifically mandated to “review the progress of women in political science in Canada since 1973 and recommend measures for corrective action where they appear warranted” (Brodie et al., Reference Janine, Andrew and Rayside1982: 1). Using Statistics Canada data on political and social science teachers, along with survey data from 44 departments of political science, the committee concluded that while the number of women in political science had increased since the earlier report, they were still “located at the bottom of the academic ladder,” found in dead-end positions and hired in contract positions rather than tenure-track positions (Brodie et al., Reference Janine, Andrew and Rayside1982: 5).

By the early 1990s the discipline began to change, witnessing a growing number of women hired into faculty positions. Again, the CPSA struck a committee on the status of women in the discipline, this time chaired by Diane Lamoureux (Université Laval), Linda Trimble (University of Alberta) and Miriam Koene (University of Alberta) (Lamoureux et al., Reference Lamoureux, Trimble and Koene1997). In 1996 they surveyed political science departments across the country, as well as women members of the discipline (Lamoureux and Trimble, Reference Lamoureux and Trimble1997). As the departmental response rate was poor, they resurveyed departments again in 1999.

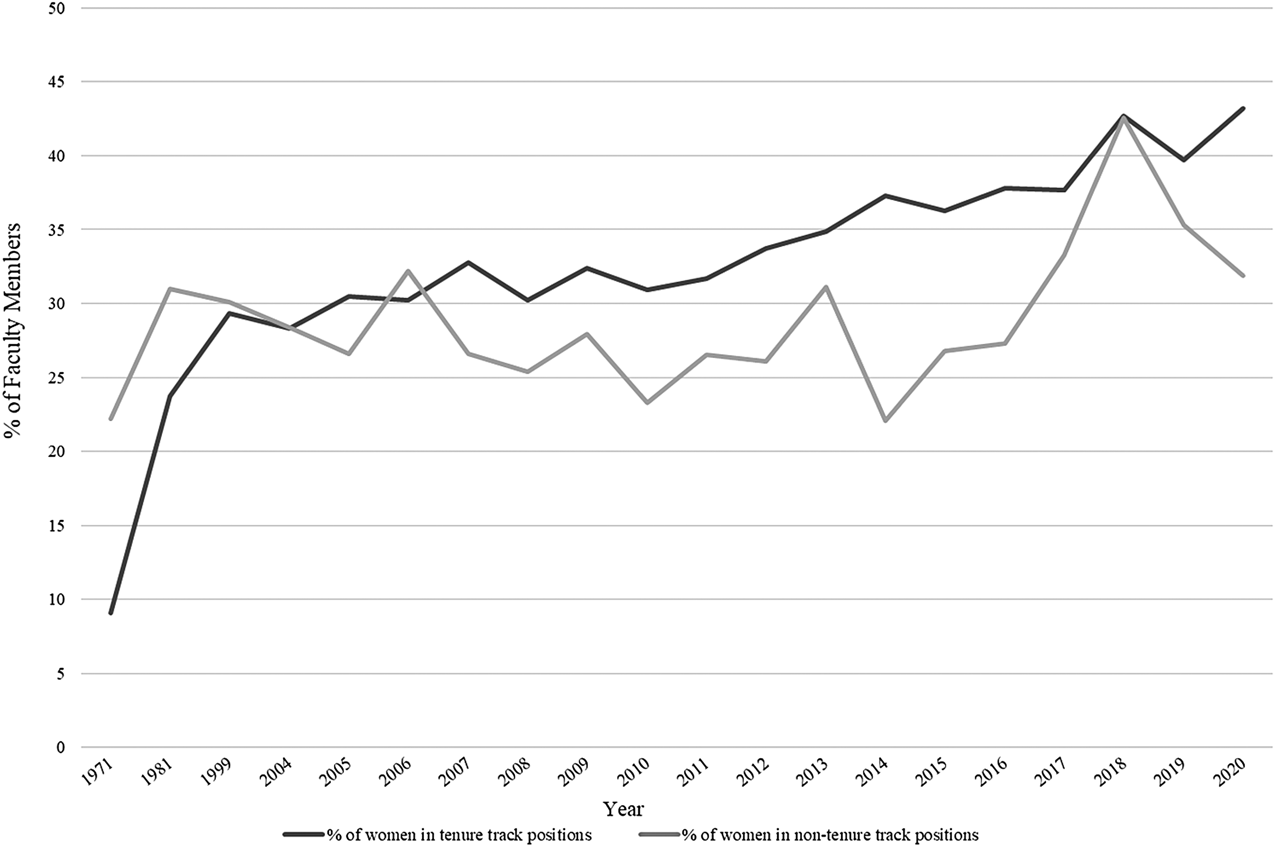

The most recent committee to be struck to examine the composition of the discipline was established in 2006-7 when Elisabeth Gidengil (McGill University) was the association's president. However, while earlier committees focused solely on the status of women in political science, this Diversity Task Force was mandated to look at a wider range of identities and their experiences within the discipline. Data from Figure 1 below come from these early CPSA committee reports, Statistics Canada data and more recent surveys of chairs of political science departments. They depict a discipline where the status of women has notably changed over the past 50 years. From a situation where women held roughly 7 per cent of the tenured or tenure-track faculty positions in 1971, we now see almost half of these positions held by women. This matches a recent analysis of the CPSA membership, which found that “in 2000, just 29 percent of Association members identified as female, whereas by 2019 the number was 42 percent” (White, Reference White2020). More importantly, women are increasingly found in stable tenured or tenure-track positions.

Figure 1 Per Cent Faculty Members Who Are Women: 1971–2020 (note: not all departments reported in each year)

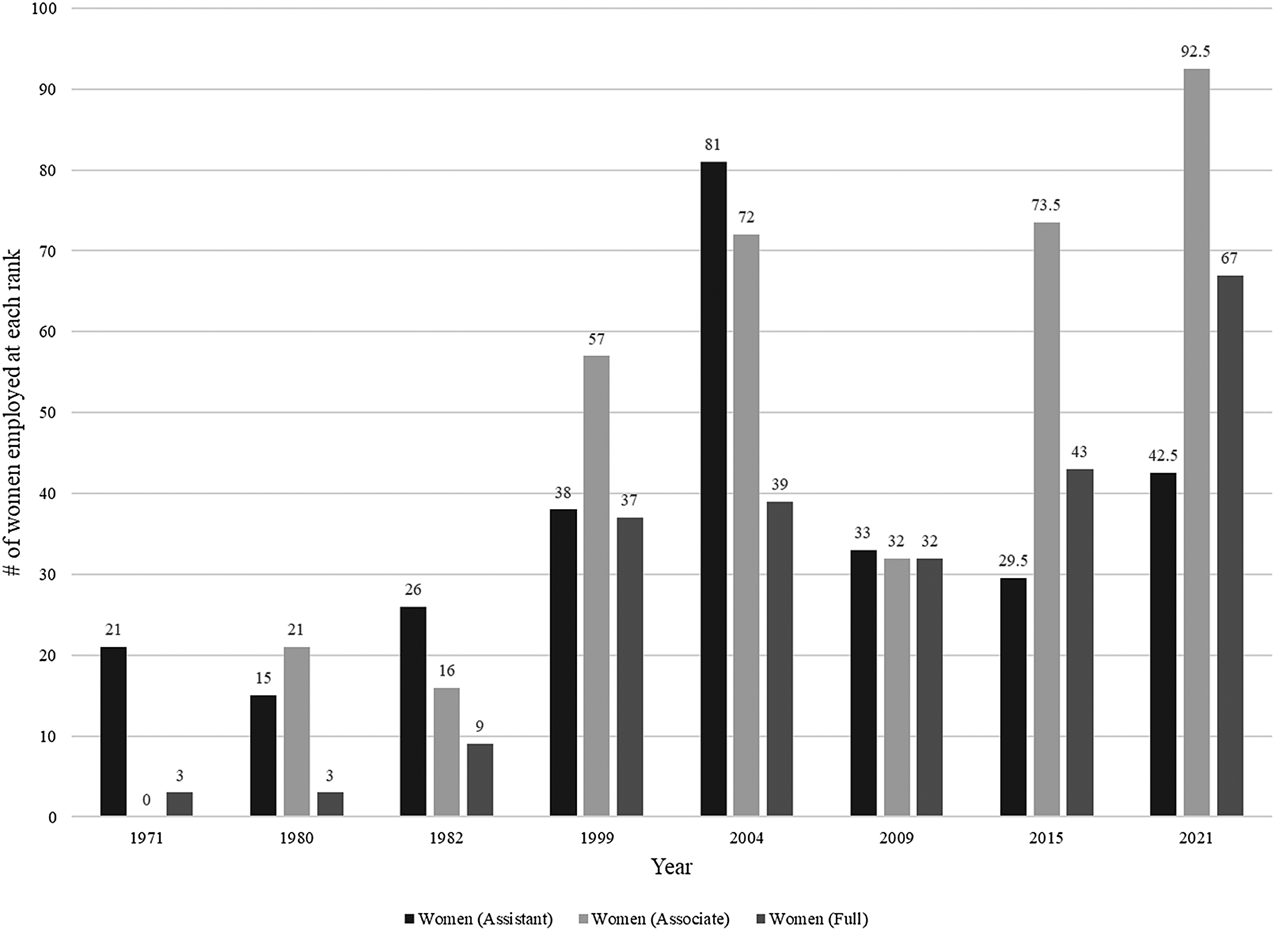

We can also find cause to celebrate if we look more closely at cross-time changes in the professional rank of these women. As more women enter the discipline, they begin in the lower ranks of assistant professor before being promoted to positions of associate or full professor. The figure below (Figure 2) shows the actual numbers (not percentages) of women at each rank, as reported in Statistics Canada data or in chair survey reports.Footnote 1 The number of women holding positions as full professors has gradually climbed, as hires made in the 1990s and 2000s have moved through the ranks. However, the clustering of women at the associate level may suggest their careers are being stalled and they are not progressing into the highest rank. Unfortunately, similar data have not been collected for men in political science, so despite anecdotal evidence, it is impossible with these data to determine if women are promoted less frequently than men.

Figure 2 Women by Rank in Tenured or Tenure-Track Faculty Positions (1971–2021)

Similar patterns are found in a recent analysis of the membership data of the CPSA. They show that in 2020 women made up 45 per cent of students and postdoctoral fellows, 52 per cent of full-time instructors/lecturers/college professors, 48 per cent of assistant professors, 40 per cent of associate professors and 40 per cent of full professors (White, Reference White2020).

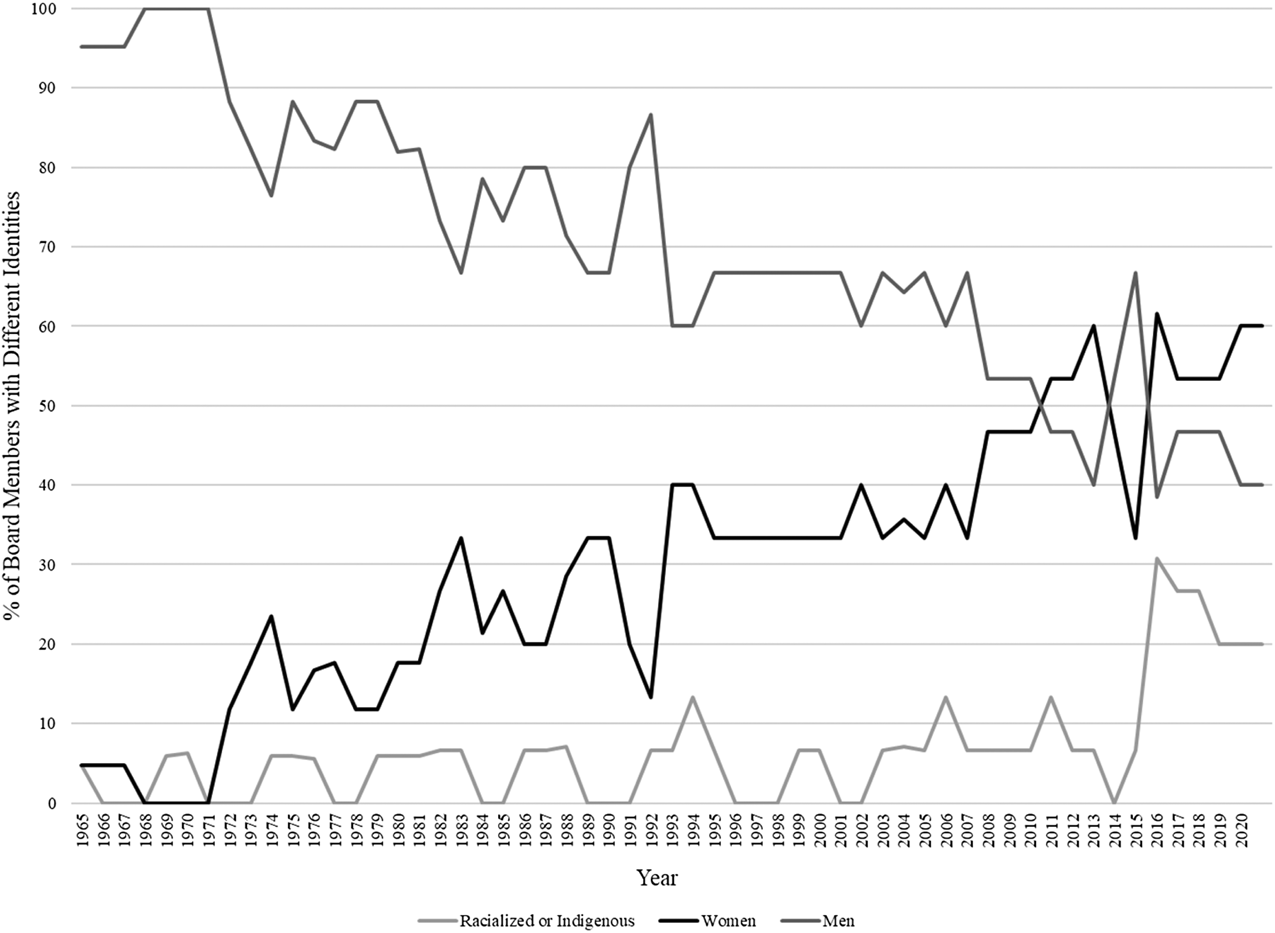

I would also point to a couple of other markers of the improved status of women within our discipline. This comes from changes that have occurred in the number of women holding positions of influence, including those of chairs of departments, conference program chairs, CPSA board members or CPSA presidents. When I attended chairs of political science meetings in the early 2000s, only a handful of women held the position as chair of their department. In 2020–21, 21 of the 60 or so department chairs were women. Other indicators of change include the fact that more than half of the past 10 annual conference program chairs have been women. As indicated in Figure 3, women's participation as members of the CPSA Board of Directors has also increased over time, such that since 2015, a majority of the positions on the board have been held by women. Furthermore, of the 14 women who have held the position of president of the CPSA, 7 have done so in the last 10 years.

Figure 3 CPSA Board Membership (1964–2020)

While these data demonstrate the change that has occurred in the status of women in the discipline, until now we do not know much about how other social groups have progressed. The experience of someone like me is very different from that of racialized, Indigenous, disabled or queer members of our discipline, something that many of the early CPSA studies neglected to address. As Malinda Smith (Reference Smith, Frances Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017) so rightly notes in her recent examination of the political science discipline, “the exclusive focus on women, as well as the absence of intersectional analysis, weakened these self studies’ ability to provide benchmarks for ‘other’ diversities, such as race and Indigeneity, but also broader notions of ‘gender’ and politics, including, for example, sexual minorities.”

Part of the reason for this lack of attention is that it is difficult to study what you cannot see. For much of its history, the discipline has been small, growing from only about 30 full-time political scientists in a handful of departments in 1959 to around 775 full-time faculty members in about 45 departments by 1980 (Trent and Stein, Reference Trent, Stein, Easton, Graziano and Gunnell1990). Women have been part of the Canadian Political Science Association since its founding in 1913 (Newton, Reference Newton2017), but it was not until their numbers began to increase in the late 1960s and early 1970s that their underrepresentation was studied. Early women faculty members—such as Mary Bliss (University of Toronto, University of Saskatchewan) (Cameron, Reference Cameron1999) or Mabel Timlin (University of Saskatchewan 1941), the first female president of the CPSA in 1959–60—were hired in departments of political economy. They were more economists than political scientists by training. From what I can ascertain, it was likely Elisabeth Wallace, who joined the University of Toronto as an assistant professor in 1955 (after having taught 10 years as a lecturer), who should be identified as the first woman political scientist (“Current Topics,” 1946). Pauline Jewett, another early woman in the field was appointed at Carleton University as a lecture that same year and subsequently hired as an assistant professor in 1956. Even then, numbers remained small, and it was not until the late 1960s that change began to take place. My data suggest that there were approximately 36 women teaching in political science in 1971 and that numbers really did not begin to climb until the 1990s.

However, the number of racialized, Indigenous or LGBTQ political scientists remained small until even later.Footnote 2 Consulting with senior colleagues and examining the Current Topics section of the Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, which reported on the university appointments, promotions and resignations in departments across the country, it becomes clear that the first racialized political scientist was probably Khalid Bin Sayeed, initially hired at the University of New Brunswick in 1959 and then at Queens University in 1961. He was later followed by individuals like Saleem Qureshi (University of Saskatchewan 1962 / Alberta 1963), Kyung-Won Kim (York 1963), Baldev Raj Nayar (McGill 1964), Pradip Sarbadhikari (Lakehead 1964), Jayant Lele (Queens 1965), A. H. Somjee (Simon Fraser University 1965), L. P. Singh (Concordia 1967), O. P. Dwivedi (Guelph 1967), Akira Ichikawa (Lethbridge 1968), Akira Kubota (University of Windsor 1970), A. Jeyaratnam Wilson (UNB 1970) and Nguyen Chi (Carleton 1971). From what I can discover, it was not until Michel Saint-Louis was hired at Université de Moncton and V. Seymour Wilson at Carleton in 1971,Footnote 3 followed by Richard Phidd (Guelph 1973), that Black political scientists were employed in tenure-track positions. Racialized women entered the discipline in much smaller numbers and often taught as stipendiary instructors or in short-term contracts. It is likely that Nadia Khalaf, hired to teach political theory at Queens in 1967, was the first tenure-stream woman of colour, with others, such as Geeta Somjee (SFU), teaching on contracts. Between 1959 and 1975, it would appear that racialized political scientists were less than 20 of the approximately 500 political scientists employed in Canada. Given these small numbers, it is no wonder that early examinations of the discipline did not address experiences of racial or ethnic discrimination, leaving this to future studies (Committee on the Profile of the Profession, 1973: 7–8).

In terms of sexual minorities, I am sure many members of our discipline over the years were in the closet to all but the most trusted friends and family members. However, it was not until the rise of the gay liberation movement of the 1970s and 1980s that well-established political scientists like Joseph Wearing (Trent 1981) or David Rayside (Toronto 1983) came out to their colleagues. Stan Persky, hired in 1983 at Capilano College was probably the first out political scientist to be hired in a tenure-track position. Even as late as the mid-1990s, most colleagues were waiting until they had tenure or had been promoted to full professor before coming out to those beyond a close social circle. Indigenous scholars began to appear even later. Joyce Green started teaching as a sessional lecturer in political science at the University of Lethbridge in 1988 with just an MA, before completing her PhD at the University of Alberta in 1997. She was hired there as a sessional lecturer in 1996 and as an assistant professor in 1997, moving to take a tenure-track job at the University of Regina in 1998. However, I believe that it was Taiaiake Alfred, who joined Concordia University as an assistant professor in 1993, who was the first Indigenous scholar hired in a tenure-track position in our discipline.

Between the early 1970s and the turn of the twenty-first century, Canada witnessed dramatic changes in immigration patterns, the widening of access to post-secondary education and a high birth rate among Canada's Indigenous population. Today 22 per cent of our population could be classified as Black, Indigenous or other people of colour (Statistics Canada, Reference Canada2017). In his 1993 presidential address to this association, V. Seymour Wilson predicted that “Canada now has an impending rendezvous with its polyethnic nature—the extent to which the extraordinary ethnic variety of recent flows of immigration, has altered, and will continue to alter, the old playing field on which the comfortable conceptions of the two ‘founding groups’ could play itself out, and indeed complacently overlook the real founding peoples conveniently sidelined on reserves” (Wilson, Reference Wilson1993: 649). I think we can all agree that this rendezvous has come and gone and the result has been an exponential growth in the racialized undergraduate student population, especially in large urban centres.

As might be expected this also meant that more racialized and Indigenous scholars were pursuing graduate education. By the time of the 2006 CPSA annual meeting, a growing disconnect was noticeable between the identities of the students in our classrooms and the faculty who were standing before them. This led to a motion from the Women's Caucus that eventually led to the Diversity Task Force noted earlier.

I was the original chair of this new Diversity Task Force but turned the role over to Yasmeen Abu-Laban (University of Alberta) when I became dean of my faculty in 2008. Other members of this committee included David Rayside (University of Toronto), Joyce Green (University of Regina) (who was later replaced by Martin Papillion [Université de Montréal]) and Richard Johnston (UBC). The committee issued three reports. The first was a report to the chairs at their 2007 chairs’ meeting (Everitt, Reference Everitt2007). The second was based on a new survey of chairs of departments (Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston and Rayside2010) that has been conducted in every year since. The third was based on a survey of members of the association (Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston, Papillon and Rayside2012). Using the categories included in the federal government's Employment Equity legislation, these studies broaden the focus from just women in the discipline to examine the status of Aboriginal people, visible minorities and persons with disabilities (Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban2016). Although the federal government does not require universities to collect data on LGBTQ individuals, the task force chose to focus on this identity as well.Footnote 4 At the same time, it attempted to account for factors such as language, religion, age, and research focus.

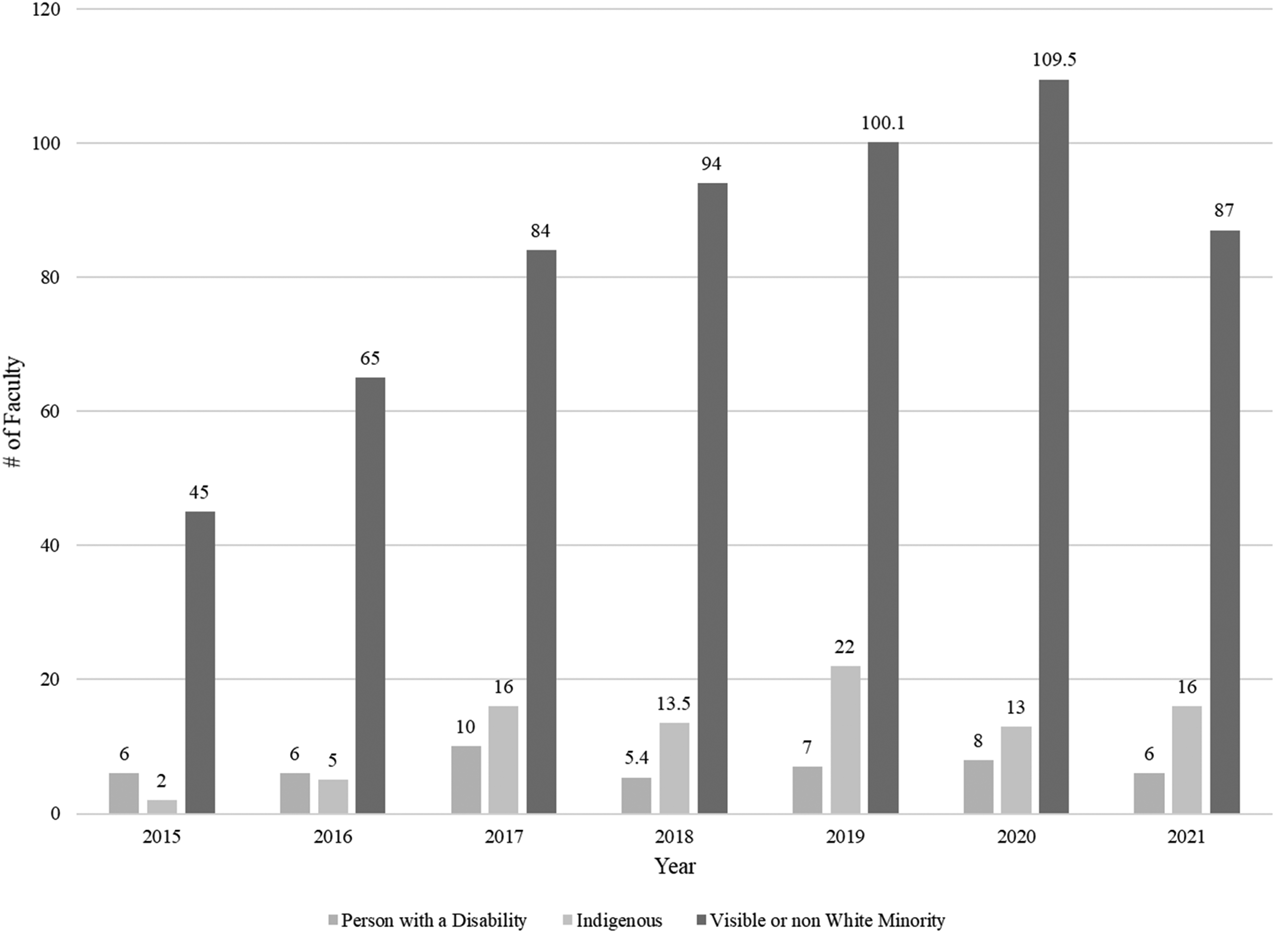

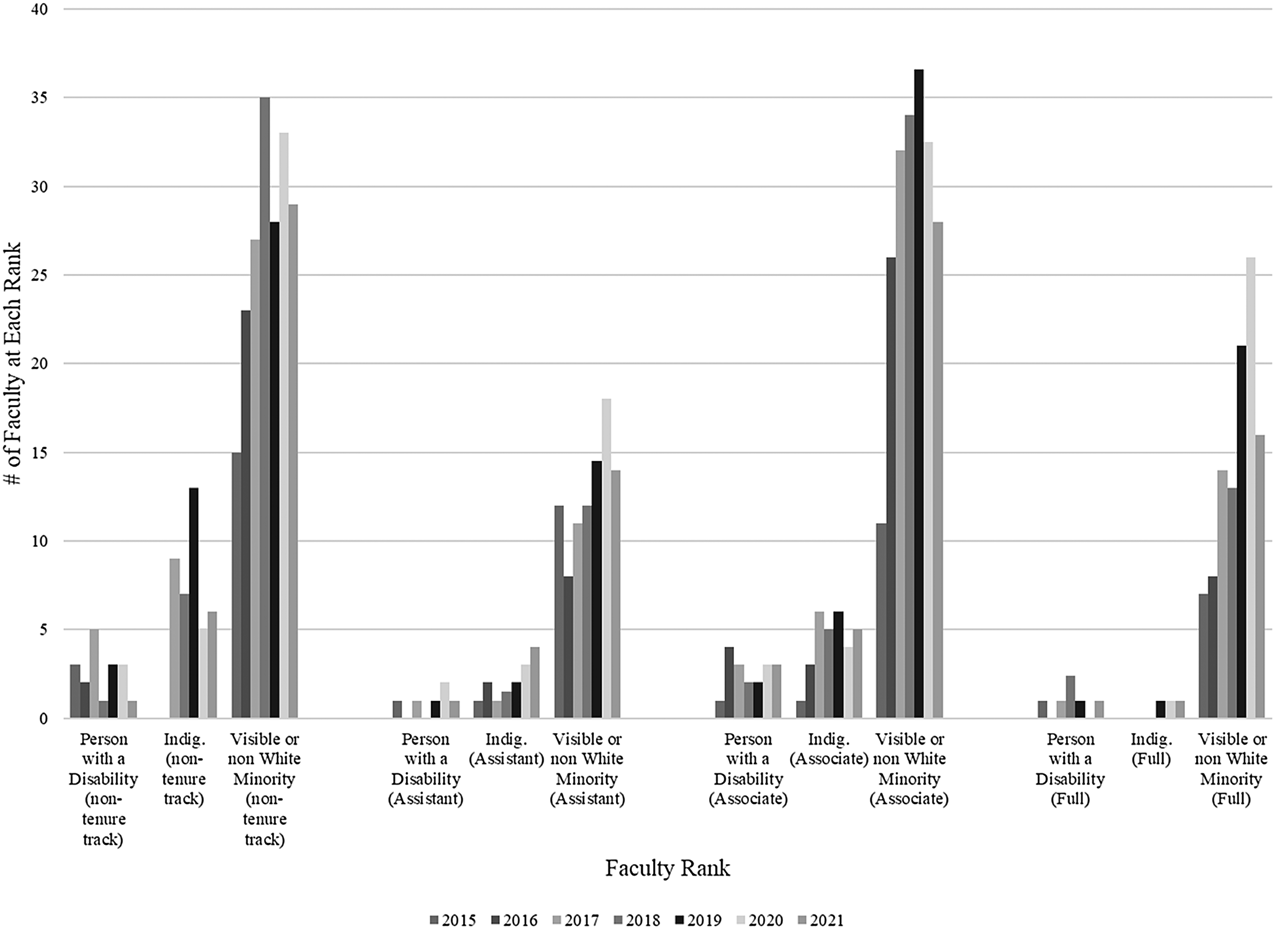

Departmental participation in the 2009 chairs’ survey was poor (only 15 departments responded), and as a result, I have not included the data from it in Figures 4 and 5. These figures depict the number of faculty in political science who fall under the federal government's Employment Equity legislation as identified in the past six years of chairs’ surveys.Footnote 5 I would caution that these data present patterns in the inclusion of members of equity-seeking groups and not the full story, due to the inconsistent responses of departments across the country. Nonetheless, they demonstrate that over the last half decade, change has been occurring in our faculty complement, albeit slowly.

Figure 4 Number of Faculty Who Are Indigenous, Racialized or with a Disability in Political Science

Figure 5 Number of Faculty Who Are Indigenous, Racialized or with a Disability, by Rank

These data support Malinda Smith's (Reference Smith, Frances Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017) diversity audit of 13 western Canadian political science departments, in which she found that some inroads had been made by Indigenous and racialized scholars. Moreover, because she used visual aids to conduct an intersectional analysis to assess each faculty member’s identity, she was able to conclude that although women in these departments are still significantly underrepresented, as a group they tended to be more diverse than men. This is in stark contrast to the situation decades earlier when almost all of the racialized political scientists listed above were men.

Despite their failings, the chairs’ surveys also help to give us an idea of where these diverse faculty are located in terms of stage of career within the discipline. As with the case of women in past decades, many find themselves in precarious and short-term teaching situations. While this varies from year to year, just over 30 per cent of racialized faculty members find themselves in non-tenure-track positions, while this is closer to 45 per cent of Indigenous scholars. No data is available on LGBTQ scholars and their locations within the discipline. While these numbers are still substantial, among those who have managed to secure a tenure-track job, an obvious progression from assistant to associate to full professor can be seen even over this short time span. More accurate tracking by departments and a longer period of analysis is obviously required before we can trust that these are true trends and not just anomalies in the data resulting from inconsistent submissions of chairs’ surveys.

Although it is clear that Indigenous and racialized scholars are more present in political science than in the past, their numbers remain relatively small, despite the fact that larger cohorts of racialized graduate students have been filling our classrooms for the past few decades. The austerity politics conducted by provincial governments in recent years has resulted in budget cuts to universities. Thus, hiring freezes may be partly to blame for this discrepancy, as they have limited the jobs for new graduates and consequently reduced the opportunities for young Black, Indigenous or other racialized scholars to be hired. Added to this is the concerning fact that in 2010, the Diversity Task Force membership survey found that equity-group respondents (including LGBTQ scholars) were more likely than others to indicate considering leaving the discipline (Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston, Papillon and Rayside2012). This suggests the pipeline may be continuing to leak, accentuating traditional departmental hierarchies and making it difficult for these scholars to move into more senior roles within the discipline or academy (Johnson and Howsam, Reference Johnson and Howsam2020; Smith, Reference Smith2019).

This is even more evident in more senior roles within the discipline. In 2020–2021, of the 60 or so political science departments across the country, only 2 are headed up by a racialized political scientist. While 7 of the 20 members of the programming committee for this conference are racialized, we have only had two racialized program chairs over our history. Furthermore, while Figure 3 indicates that since 2015, three to four of the positions on the CPSA Board of Directors in any given year have been filled by members who are Indigenous or people of colour, only four past CPSA presidents are of non-European heritage. It is clear that the CPSA still has some distance to go in addressing the issue of EDID.

While the growth (albeit slow) in the number of racialized or Indigenous faculty is encouraging, it is also important to acknowledge the significant amount of invisible labour that falls on these scholars. As with previous generations of women academics who were tasked to be the women's voice on departmental, faculty or university committees, or who were sought out as mentors to younger cohorts of scholars, our queer, Black, Indigenous and other racialized colleagues face heavier workloads than others for the same reasons (Dhamoon, Reference Dhamoon2020).

Diversity in What We Study

The issue of who holds membership in our association and our faculties has clear implications for what we choose to focus on in our discipline. As the discipline has diversified, research has shifted from looking at questions of nationalism, language and religion closely linked to the founding narratives that understand Canada as polity based on two peoples (English and French) to broader questions of representation of other identities, of patterns of exclusion and inclusion and means of dominance and resistance. As Nath (Reference Nath2011) has argued, the “inclusion of subjects, processes and discourses that have been hitherto ignored can substantively change our analytic perceptions of the power and influence of critical institutions as well as alter our conceptions of what triggers political change” (182). Thus, we might expect that a change in the personnel in the discipline will be linked to a change in the research produced by Canadian political scientists. To some extent, this has indeed been the case.

While not all women political scientists are feminists, nor do all women focus on questions of gender in their research, many do. Feminist scholars were early to challenge a discipline that studied the “universal experience” and, in the process, rendered a focus on identities based on sex, gender, sexual orientation, race or disability irrelevant to the understanding of politics and government (Vickers, Reference Vickers1997: 11). Furthermore, a focus on the public sphere meant that those who were excluded from many of the institutions and practices of big “P” politics, including women and racialized citizens, were often ignored.

It was women in the discipline who offered the first courses on women and politics, who presented papers on these topics and then published them in the Canadian Journal of Political Science—or, more often, in interdisciplinary women studies’ journals. Likewise, racialized and Indigenous scholars, whose research challenged mainstream political science, were also more likely to address questions of systemic racism and colonialism.

As more women—and later, Black, Indigenous and other racialized scholars—attained academic positions in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, new cohorts of students were attracted to the discipline and given the freedom to study or research questions related to gender, race and Indigenous politics.

In fact, by the mid-1990s, Lamoureux and her colleagues (1997: 5) reported to the CPSA that 22 per cent of those women surveyed, including PhD students, gave “women and politics” as their primary research field, while 18 per cent identified it as their second, and 10 per cent as their third fields. By 1999, only three departments of political science reported not having at least one undergraduate course on women and politics, with about a third indicating they offered two or more. Fewer graduate courses were available, and at that time, only York and the University of Alberta offered gender and politics as a PhD field (Trimble, Reference Trimble2000: 21).

By 2012, the Diversity Task Force report indicated that of the 150 respondents who had taken a course on women or gender issues, 130 had taken them in the period between the 1980s and 2000s, while only 20 had been able to take such a course prior to this. The report went on to note that “thesis research in this area of study expanded appreciably somewhat later, in the 1990s and 2000s, with 18 theses from those cohorts compared to only two from earlier cohorts” (Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston, Papillon and Rayside2012).

This growth in the number of people studying these topics is reflected in the papers presented at the CPSA annual conference. As Tolley (Reference Tolley2017) notes in her review of 50 years of CPSA conferences, little work on women or gender issues was presented prior to the mid-1980s. Much of this early work focused on women's political participation, candidate recruitment and engagement in party politics. As time passed, the focus broadened to incorporate feminist challenges to political theory, equality rights and gendered critiques to other political science subfields (Tolley, Reference Tolley2017). The first paper that examined gay and lesbian politics, entitled “The Liberalization of Gay Politics: North American and European Comparisons,” was presented by David Rayside at the 1984 CPSA conference. By the mid-1990s gender-related papers began to focus on intersectionality and citizenship, while work on gender and colonialism in Canada began to appear in the 2000s. The establishment of a separate section for Women and Politics scholarship in 2000 provided a home for work focusing on women and ensured an interested and engaged audience for this work. Since then, between 10 and 15 per cent of the papers presented at the CPSA annual conference have addressed a gender-related issue (Tolley, Reference Tolley2017). These conference papers have led to more articles and books by women scholars and more resources for the growing number of courses being offered on women or gender and politics. However, just having an increase in the number of women political scientists does not necessarily translate into a greater focus on women or women's experience in the political realm. While Vickers (Reference Vickers2015) found that women were publishing a larger proportion of the articles in the Canadian Journal of Political Science (an increase from about 17 per cent in 1984 to around 30 per cent by 2015), she noted that just 8 per cent of the CJPS articles examined in the last decade of her study had gender content (Vickers, Reference Vickers2015: 759–60). This fits with Nath and her colleagues’ (2018) study of the gender and diversity articles in the CJPS between 1969 and 2017. They found that 109 articles were published in this period, but that if the journal had not published a special issue on “Finding Feminisms” in 2017, there would have been fewer articles on this topic since 2010 than in the 2000s. Furthermore, while separate courses on gender and politics are more common than in the past, many of the other courses offered at the undergraduate and graduate levels do not include any significant gender content.

This trend has led Vickers to argue that “more women professors, robust politics and gender fields and feminist subfields haven't resulted in transformative change in how conventional political scientists think” (Vickers, Reference Vickers2015: 749; see also Nath et al., Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018). To a large part, this is because the discipline remains siloed and the gender-related work is not routinely read by male political scientists (Vickers, Reference Vickers2015: 750). As Tolley (Reference Tolley2017) noted, when conference papers have gender content, they are often grouped with other similar papers on gender panels rather than being included on panels dealing with policy, parliament or political theory. The result is that “women, gender and politics scholars are communicating their research results to other women, gender and politics scholars, and gender-related research tends not to appear on panels where the focus is more ‘mainstream’” (155).

Even then, many scholars, myself included, continue to examine the same types of questions that preoccupy our male colleagues, but with a gender twist (Nath et al., Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018). Thus, by continuing to privilege research on political elites and institutions like parliament, parties, and the courts, even feminist scholars like myself could be accused of reproducing systems of power within the discipline rather than truly unsettling them (Nath et al., Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018). These are legitimate arguments, and they are ones that relate to scholarship not just on women but also for work on other marginalized groups including LGBTQ+, Indigenous and racialized individuals. These arguments are also increasingly being addressed by the more intersectional and critical approaches adopted by younger generations of scholars concerned with exploring the “informal” political realms and the overlapping experiences of marginalization that stem from sex, race, class and colonial experiences.

As with feminist scholarship, which was originally driven by scholars in sociology, history and gender studies, much of the early cutting-edge work on race and politics was conducted in other disciplines (Smith, Reference Smith, Brodie and Trimble2003: 110). However, the establishment of the CPSA's section on Race, Ethnicity, Indigenous Peoples and Politics in 2009 has provided a disciplinary focus for this work. Arguing for this section, its promoters pointed to an increase in the number of academics working in this field, a growing body of publications, as well as SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) and MCRI (Major Collaborative Research Initiatives) grants devoted to these themes, and an increase in the number of graduate students in political science departments across the country working in these areas.Footnote 6

Smith has argued that there is a “relationship between the existence of diverse faculty and the number of diverse course offerings” (Smith, Reference Smith2019). This suggests that the slow growth in the number of racialized faculty documented in the early section of this paper can be linked to the increase in the number of Black, Indigenous and other racialized graduate students and subsequently faculty working in this field. This trend is reflected in the results of the Diversity Task Force membership survey, which found that dissertations on the topics of race and ethnicity or Indigenous politics were more likely to be completed by racialized or Indigenous graduate students than those who were not. The task force also found that enrolments in political science courses on race and ethnicity had increased from 27 per cent in the cohorts of scholars who completed their graduate work before the 1970s to 42 per cent in those who had attended graduate schools in 2000s (Abu-Laban et al., Reference Abu-Laban, Everitt, Johnston, Papillon and Rayside2012). Those who were graduate students at the time of the survey (28 per cent) were also more likely than students in earlier cohorts (12 per cent) to indicate that they had taken at least one course that dealt with Indigenous issues. Furthermore, the number of dissertations on Indigenous topics was higher among these students (16 per cent) than those in previous cohorts (8 per cent), and all five of the Indigenous respondents were writing or had written their theses on Indigenous issues.Footnote 7

As with the situation of gender scholarship, these changes suggest that by the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, studies of race and Indigenous politics have become normalized within the discipline. Yet, as Thompson has claimed, “while the mainstream may not necessarily be opposed to the study of race and racial consequences in politics, the fact remains that this subject is understudied in English Canadian political science” (Thompson, Reference Thompson2008: 530). Ladner has argued that “because of the roots of the discipline, political scientists have largely ignored Indigenous political traditions and have largely studied contemporary Indigenous politics from the vantage point of the Western-Eurocentric tradition” (Ladner, Reference Ladner2017: 164). This is ironic, as Indigeneity, by definition, occurs in the context of the power imbalance and struggle for territory and political rights within a system of colonialism and thus is something that should fit well within a discipline preoccupied with power. Even more critical is Smith, who has written that race and Indigeneity have been “rendered invisible in the production of a disciplinary canon and archive” (Smith, Reference Smith, Frances Henry, Dua, James, Kobayashi, Li, Ramos and Smith2017: 243). This is supported by Tolley's (Reference Tolley2020) analysis of Canadian politics textbooks, in which she finds that content dealing with immigrants and minorities is siloed in the textbooks’ chapters on “diversity,” and these individuals rarely appear as key political actors in their own right. In other words, like feminist political science, research on race and Indigenous politics has also been siloed in subfields which are perceived to be of little relevance to the “core” of the discipline (Nath et al., Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018).

Thus, while the change in the disciplinary composition has resulted in a wealth of new knowledge and approaches to understanding the political world and its impact on women, sexual minorities, and racialized and Indigenous individuals, it has not yet notably changed the mainstream of what is considered to be political science. As a result, it remains absent from much of what gets taught in our classrooms, published in our journals and referenced in our own work (Vickers, Reference Vickers2015; Thompson, Reference Thompson2008; Ladner, Reference Ladner2017; Nath et al., Reference Nath, Tungohan and Gaucher2018).

I would be remiss, however, if I did not note the challenge that many male, white or straight members of our discipline face if they do attempt to engage with this scholarship. This includes factors such as the strange feeling of otherness as the only man in a gender and politics class or the only white person in a class focusing on race or Indigenous politics. Of greater concern might be the fear of the appropriation of voice that comes when researching or teaching about an identity that one does not share. More practically, we should not forget the challenges young scholars might face in getting hired if their research expertise is focused on an identity that is not their own. Finally, a desire to avoid the minefields we might unwittingly step on makes it appealing to completely avoid these topics and leave it to those more sensitive and conversant with the literature.

While these excuses have some legitimacy, they are still excuses, and I would argue that even among those with the best intentions, by avoiding these literatures we are reinforcing past sexist, heteronormative, racist and colonialist barriers within our discipline. Doing so will only widen the distance between us and our students, who are often more attuned than we are to social or racial injustices.

There are, however, encouraging signs of change in the discipline. The recent special edition of the CJPS on feminist political science gives space to this work and helps to broaden the scope of disciplinary boundaries. Similar increases in the number of articles published on sexuality, race or Indigenous politics are promising. And while one volume of a journal or a handful of articles is unlikely to fully reflect the range of theoretical approaches or subjects now considered in these fields, they help to not only “engage with core dimensions of the discipline but also push the boundaries of traditional political science research” (Dobrowolsky et al., Reference Dobrowolsky, MacDonald, Raney, Collier and Dufour2017: 408). Furthermore, the Indigenous content syllabus materials identified by the Reconciliation committee and a growing number of textbooks looking at subfields in our discipline through the lenses of gender, sexuality, race or Indigeneity make it easier for us to include this content in our classes (see, for example, Brodie and Trimble, Reference Brodie and Trimble2003; Tremblay and Everitt, Reference Tremblay and Everitt2020). Now we just need to do so. There is also a growing body of work being undertaken by allies that needs to be acknowledged. This comes in the form of making space for this research in special issues of journals and collected editions or in the actual conduct of research on these topics by those less vulnerable because of their seniority or reputations in the discipline. I would point to Graham White's leadership as editor of the CJPS at the time the special issue on Feminism in the Discipline was produced as an example of the former, and my own work on LGBTQ politics in Canada as an example of the later (Everitt, Reference Everitt2015; Everitt and Camp, Reference Everitt, Camp and Bashevkin2009a, Reference Everitt and Camp2009b, Reference Everitt and Camp2014; Everitt and Lewis, Reference Everitt, Lewis, Tremblay and Everitt2020; Everitt and Horvath, Reference Everitt and Horvath2021; Everitt and Raney, Reference Everitt, Raney and Tremblay2019; Everitt and Tremblay, Reference Everitt and Tremblay2020; Everitt et al., Reference Everitt, Tremblay, Wagner and Tremblay2019; Tremblay and Everitt, Reference Tremblay and Everitt2020).

Likewise, the theme of the 2021 CPSA annual meeting has resulted in several panels, workshops and plenary addresses focusing on diversifying, queering and decolonizing the discipline of political science. Although it may still be possible to avoid these topics, the abundance of them makes it more difficult than in the past. Similarly, several of the recent meetings of the chairs of political science departments have had targeted sessions on decolonizing our curriculum and improving diversity within the departments, challenging the institutional leadership of our discipline to reflect on how well we are helping students understand the diverse world in which they live.

Nonetheless, the relative silence on topics of diversity, particularly when countered with the growing racial diversity of the Canadian population itself, has implications for our curriculum, our understanding of our discipline as an intellectual field of inquiry, how we train our graduate students and how we value and reward scholars working in this field. This lacuna translates into the dangerous disciplinary lag predicted by Wilson decades ago (Wilson, Reference Wilson1993: 650).

Diversity in Methodologies

This leads to my last point about diversity. One of the greatest challenges facing scholars working in this field is the question of how we study diverse groups of individuals. In my own case, the fact that I employ surveys, content analysis and experimental designs has probably made it easier for me than it might be for others doing more qualitative, observational, ethnographic, narrative or critical analyses. However, as a feminist scholar, I can acknowledge the value that context and lived experience brings to our understanding of our political world. I also recognize the questions that researchers interested in women, sexual minorities, racialized or Indigenous individuals ask are seldom suited for the positivist approaches grounded in the unachievable values of universalism, objectivity and neutrality too often valued by political science.

For years I had students in my research methods classes read sections of Jill Vickers’ (Reference Vickers1997) Reinventing Political Science: A Feminist Approach to challenge them to think not just about how we study our research subjects but also what “counts” as “reliable knowledge.” Her critique of the methodological approaches we commonly teach our students highlights how the practice of “context-stripping” that occurs so often with quantitative methods makes it difficult to understand how people with different identities may be affected by political decisions or limited in their political opportunities. Unfortunately, as Vickers notes, the “scientific turn” taken by many in [conventional political science] exacerbated the methodological incompatibility and increased its intolerance for pluralism in approaches and methods” (Vickers, Reference Vickers2015: 753).

This same argument has been deployed by scholars of race, ethnicity and Indigeneity to account for why mainstream political science has been suspicious or inhospitable to their work (Nath, Reference Nath2011; Ladner, Reference Ladner2017; Thompson, Reference Thompson2008). Understanding the experiences of those regularly confronted with systemic racism, who have had to deal with the impact of policies that were created without thought to the differential effect on various groups of Canadians, or whose conceptions of community are not premised on neoliberal ideologies requires more than a survey, an experiment or a simple counting of who sits in political institutions and who does not. It requires valuing shared historical experiences, understanding the impact of intersectionality and the effect of multiple and overlapping oppressions and looking beyond the categories and tools that have dominated political science in the past. Furthermore, it requires recognizing that racism is a framework that perpetuates relationships of dominance and subordination and its eradication requires more than simply hiring a more diverse range of faculty members.

As a result, if we, as a discipline, are to remain relevant and provide our students with the tools and skills to enable them to study a world that is increasingly diverse, globalized and highly integrated, we need to broaden our understanding of who and what is political and where and how this political activity takes place. We must also become more accepting of epistemological and methodological diversity. While evidence suggests that political scientists in Canada have not been overwhelmed by the behavioural revolution (Abu-Laban, Reference Abu-Laban2017) and are more willing to employ and publish research based on more diverse methodologies than our neighbours to the south (Héroux-Legault, Reference Héroux-Legault2017), disciplinary siloes and methodological prejudices remain. These continue to make it difficult for scholars who employ non-positivistic approaches to get published in our journals, included in our curriculum and referenced in our own work.

This methodological intolerance is particularly challenging for Indigenous scholars, who often build their arguments on “conversational and storytelling approaches,” personal experience or one-on-one interactions, rather than methodologies deemed by political scientists to be more empirical, objective and impartial (Dion et al., Reference Dion, Ríos, Leonard and Gabel2020; Gabel and Goodman, Reference Gabel and Goodman2021). Like the approach taken by many feminist scholars, Indigenous scholars understand “knowledge as relational, as between peoples or between people and the natural world” (Dion et al., Reference Dion, Ríos, Leonard and Gabel2020: 128). This disconnect is perpetuated by the view of many of these scholars that Indigenous communities are not just “research subjects” to be studied at arm's length (Ladner, Reference Ladner2017). Rather, they are more likely to engage in emancipatory or participatory research based on the principles of respect, relevance, reciprocity and responsibility (Kirkness and Barnhardt, Reference Kirkness and Barnhardt1991).

Many Indigenous, feminist or scholars of race and ethnicity in Canadian political scientists employ these community-engaged research methodologies, as can be seen from their inclusion in a recent special issue on socially engaged research and teaching in Politics, Groups and Identities co-edited by Tungohan et al. (Reference Tungohan, Levac and Price2020). It should be noted, though, that these community-based approaches are more time-consuming and require more efforts to justify their value to reviewers, grant assessors, and hiring and promotion committees than more traditional research methodologies. All of this presents additional hurdles and forms of discrimination to colleagues who are already made vulnerable by their siloed research fields or numeric minority in our discipline.

Conclusions

The past year has emphasized how important the issue of diversity has become and the need for us as political scientists to take it more seriously in our research, in our teaching, and in the way we create, sustain and replicate our academic institutions. Events such as the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer and the ensuing Black Lives Matter demonstrations, the continued police oppression of Canada's Black and Indigenous peoples, the anti-Asian racism that has come to the surface following the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on racialized Canadians and Indigenous communities or on women, and more recently the discovery of a grave containing 215 children at a BC residential school have only highlighted the continued exclusion, systemic racism, colonialism and the political underrepresentation faced by large swaths of our population. These all point to the need for analyses of political events and public responses that take into account gender, sexuality, class, race, ethnicity and Indigeneity. To ignore the importance of these factors would be bad political science. As Thompson argued in her critique of our discipline, “The lack of research on race is not simply an issue of identified gaps in political research but rather speaks to a fundamental disconnect between an academic discipline and the ‘on-the-ground’ experiences of the society it purports to analyze and explore” (Thompson, Reference Thompson2008: 541).

So while someone like me might find the discipline has become more welcoming and inclusive than it was when I was a graduate student, it is clear we still have some ways to go to make our membership more reflective of the demographic make-up of our classrooms or our wider society. While there is a growing body of scholarship examining political experiences or phenomena with a focus on gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity or Indigenous politics, more efforts need to be made on the part of those who work in conventional political science to push beyond the canon to incorporate this work exploring these underrepresented voices and perspectives. While Canadian political science has not experienced the hegemonic dominance of quantitative methodologies that strip context and nuance from the things we study, we can do more to be open to different points of view, to acknowledge alternative theoretical approaches and to give credence to diverse forms of evidence or methods in our discipline's scholarship. It is only by welcoming this diversity in our discipline that we will be able to train the next generation of scholars capable of addressing the issues facing the increasingly complex and diverse world in which we live.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank colleagues Louise Carbert, Joyce Green, J. P. Lewis, Shaun Narine, Neil Thomlinson, Ethel Tungohan and Angelia Wagner for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.