In 1617, the merchant, art agent, and diplomat Philipp Hainhofer wrote to his long-standing patron, Duke Philipp II of Pomerania-Stettin. He was reporting great news. The duke’s extensive and ornately furnished cabinet of curiosities was finally finished after seven years. Aside from delighting in its completion, Hainhofer now faced the unenviable task of explaining the high costs and lengthy production time. The eloquent, art-loving broker was unerring in his justification. He had succeeded in making ‘something princely and prestigious for such a discerning and art-loving prince’, to which other princely cabinets were ‘of no comparison’ (Figure 1).Footnote 1

Figure 1. Der Pommersche Kunstschrank, Gesamtansicht vor seiner Zerstörung, photo, 1939. Public Domain.

Born in 1578 to a Lutheran merchant family in bi-confessional Augsburg, Philipp Hainhofer was one of the eleven surviving children of Melchior Hainhofer II and Barbara Hörmann.Footnote 2 His family had experienced rising economic and social status amongst the mercantile elite in the preceding decades, at a time when Augsburg was reaching the height of its reputation as a centre for the international trade in luxury goods and rarities during the sixteenth century.Footnote 3 The Hainhofer firm specialized in textiles. Specifically, Hainhofer’s father Melchior and his uncle Matthaeus focused on the import of silks and velvets, alongside secondary ventures such the lucrative trade in copper between Augsburg and Italy.Footnote 4 It was into this highly specialized business that the young Hainhofer entered, writing to contacts about potential business ventures from as early as 1599, and taking on more personal responsibility following the death of his uncle in 1601.Footnote 5

Representing a new kind of socially mobile merchant, Hainhofer substantially broadened the firm’s range of merchandise to include all sorts of commodities, art objects, and rarities. This diversification was, in part, an astute business decision, mirrored by several of Hainhofer’s contemporaries, in response to frequent periods of inflation from the 1580s, leading to the economic disaster (Kipper- und Wipperzeit) which followed the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618.Footnote 6 From the early seventeenth century, Hainhofer developed an extensive ‘collection…which doubled as a commercial stock room’ in his house on Annaplatz, where he received many of his notable guests.Footnote 7 These included Duke Wilhelm V of Bavaria in 1606, several years after Hainhofer’s first visit to the Wittelsbach court in Munich. Hainhofer enthusiastically recorded the 200 florins worth of objects purchased by the duke, boasting of the duke’s ‘gracious and familiar’ manner.Footnote 8 Hainhofer’s reports provide clear insights into the experience of his esteemed guests. Hainhofer would first lead them through halls containing family portraits, then of noble and princely potentates, establishing himself as a man of high regard.Footnote 9 As with Wilhelm V, these visits culminated with the exchange of gifts. Those received by Hainhofer were incorporated into his personal chamber of art objects, from which many of his own gifts came. Collections like Hainhofer's were dynamic and fluid.Footnote 10 By the time of his first princely commission for the Lutheran Duke Philipp of Pomerania-Stettin in 1610, Hainhofer had cemented his role as a diplomat, informant, and knowledgeable merchant, valued by patrons for his powers of material and visual discernment.

Marika Keblusek has argued that diplomats serving as ‘cultural intermediaries’ were ‘the most obvious group to undertake trade in luxury items’ due to their ‘mobility, their connection to existing international trade routes, their exclusive ties and access to courts, and their personal networks’.Footnote 11 Merchants were similarly able to assume roles as ‘double agents’ as their ‘range of commercial networks’ offered ‘control over a trustworthy information circuit’.Footnote 12 As recent work by Michael Wenzel and Ulinka Rublack demonstrates, this was an age when art-lovers (Kunstliebhaber) were able to cross confessional divides in these roles as agents, cultural brokers, and diplomats.Footnote 13 Hainhofer, assuming these roles, was able to situate himself as a key intermediary, and trusted confidant.

The construction of the Pomeranian Art Cabinet, Hainhofer’s first princely commission, began as a far smaller endeavour. It formed one part of a collection of objects intended for Duke Philipp of Pomeranian-Stettin and Duchess Sophia of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg. These included a cabinet, a model farmyard (Meierhof), and a silver sewing basket (Nähkorb). The cabinet was initially intended to be a writing desk (Schreibtisch), but the commission soon expanded, diversifying the cabinet’s contents and functions. Upon completion, it contained astronomical and mathematical instruments, tableware, games, barbers’ tools, apothecary items, and more. In 1610, Duke Philipp could surely not have anticipated how extensive the project would become. Only in 1617 did Hainhofer undertake the lengthy journey to the Stettin (Szczecin) court, accompanied by the Augsburg cabinet-maker Ulrich Baumgartner. Such delays were a consequence of the extensive nature of the collection which Hainhofer repeatedly assured the duke was unparalleled. The extended time, craftsmanship, and expensive materials contributed to the high costs of the cabinet, payment for which had not been received by Hainhofer upon the piece’s delivery. Duke Philipp died in 1618 and Hainhofer’s fee was never paid in full.

During the period of the cabinet’s construction, Hainhofer worked almost exclusively on behalf of the duke, his first princely patron. Not deterred by the lack of payment, Hainhofer subsequently made several other large art cabinets, shouldering substantial financial risk. His perseverance with his cabinet projects aimed at princely patrons was, in part, due to his firmly entrenched role as a diplomat and informant. According to Michael Wenzel, Hainhofer did not attempt to emulate the nobility by acquiring land, but rather sought recognition based on his connections to rulers, pointing to the more honorific patrician system found in Augsburg.Footnote 14 In a period of religious division, Hainhofer’s ability to act as both confidant and informant across confessional divides, such as at the Catholic Bavarian court in Munich, is particularly notable.

Perhaps most strikingly, the 1610 commission from the Pomeranian duke and duchess was incredibly important for Hainhofer in necessitating their frequent correspondence which resulted in a close, personal relationship. The duke’s entry in Hainhofer’s famous Stammbuch (or ‘friendship album’) attests to this remarkable fidelity. Of the remaining entries in the Stammbuch, containing elaborate coats of arms and signatures of notable individuals, Duke Philipp’s is amongst the only entry to extend over two pages (Figures 2 and 3).Footnote 15 As was typical of Hainhofer’s elaborate entry style, the left-hand side contains Philipp’s signature, the Pomeranian coat of arms, and the duke’s motto, incorporated into an allegorical landscape painted by Johann Kager. Overleaf is a micrograph portrait of the duke, signed by Simon Tölman (1563–1630), an Augsburg councillor and lawyer, and the godfather (alongside Duke Philipp) of Hainhofer’s eldest son. Tölman’s micrograph portrait of Philipp II was a point of pride for Hainhofer, prompting him to send it to Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria in 1614, who praised it as a ‘beautiful invention’.Footnote 16 Alongside the portrait is a Latin verse stating that Duke Philipp – who, from a young age, had cultivated his persona as patron of the arts – sought ‘to polish the genius of the Muses’.Footnote 17 Hainhofer actively assisted in this mission by designing and curating the Pomeranian Cabinet, whose form and iconography resembled a temple to the Muses, topped with a Parnassus crown. It was the most significant commission of the duke’s reign, and Hainhofer’s first great cabinet work.

Figure 2. Coat of arms and signature of Duke Philipp II of Pomerania-Stettin in Philipp Hainhofer's Großes Stammbuch, fo. 36, Cod. Guelf. 355 Noviss. 8°. © Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

Figure 3. Portrait of Duke Philipp II of Pomerania-Stettin in Philipp Hainhofer's Großes Stammbuch, fo. 37, Cod. Guelf. 355 Noviss. 8°. © Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

I

Existing literature on Hainhofer and his cabinets centres the diplomatic and political networks in which Hainhofer was involved, alongside analyses of the visual schema of his cabinets.Footnote 18 Building upon this work, this article adopts a novel approach to Hainhofer and the Pomeranian Cabinet, seeking to integrate histories of science, collecting, materiality, and of the body. The history of collecting and information architecture is a field that has long engaged scholars across disciplines, and historians of early modern Europe are no exception.Footnote 19 Lorraine Daston and Katherine Park have written that the ‘history of wonders as objects of natural inquiry is…also a history of the orders of nature’.Footnote 20 Once collected, objects and information needed to be ordered. The desire to collect in ways that were ‘universal’ coincided with an engagement with the ‘curious’, which often applied to knowledge and matter that lay outside of the bounds of European tradition, reflecting ever-increasing encounters with non-European indigenous populations.

By the turn of the seventeenth century, collection and display in Europe had assumed a particular form of expression in the Kunst- or Wunderkammer: a room (or rooms) which sought to collect and represent the world’s curiosities. These rooms often housed individual Kunstschränke (art cabinets). The organizing principles of the individual Kunstschränke were far removed from the Linnean systems of taxonomy that were to follow in the eighteenth century, intermingling natural rarities and artificial objects. Jeffrey Chipps-Smith’s recent publication on the Kunstkammer of the Holy Roman Empire discusses two diverse contemporary tracts on collecting by Samuel Quiccheburg and Gabriel Kaltemarckt, published in 1565 and 1587 respectively.Footnote 21 After discussing the clear differences in these texts’ prioritization of the artforms to be contained within princely collections, Chipps-Smith observes that, fundamentally, ‘both shared an underlying belief that a well-formed collection expressed the magnificence of the ruler’.Footnote 22

While intended to reflect the splendour of its patron, Hainhofer’s Pomeranian Cabinet closely tied together his ambitions with those of Duke Philipp II. Hainhofer’s hand can be seen in almost every stage of the construction of the Pomeranian Cabinet: reporting on the frequent visits he made to oversee the progress of the artisans he employed; selecting objects he believed worthy of inclusion; and firmly steering the duke towards his desired iconographic programme. As such, it was a piece which connected and represented geographically and socially stratified individuals.

This article contends that by bringing the history of the Kunstschrank into conversation with histories of health, corporeality, and sensation, new information can be gauged about both the physical space of the cabinet and the networks engaged in its creation. The history of the body is far-reaching, with recent scholarship centring the relationship between body, object, and affect.Footnote 23 The bodies engaged in the Kunstschrank were plural – of dukes and duchesses, merchants, and artisans – spanning social and confessional divides. By adopting a ‘body-centred approach’, I direct attention towards the ways in which material and object lives are subject to dynamic forces involving flows of matter, affect, and knowledge.Footnote 24 By foregrounding processes of managing health, this article demands that we rethink the Kunstschrank as a space wherein material and medical histories are inextricably connected in ways that are essential for recovering how these objects were made, interpreted, and used by period actors.Footnote 25

This article will first examine the body of the merchant, Philipp Hainhofer, who suffered with bouts of ill health and personal loss during the construction and delivery of the Pomeranian Cabinet. This section discusses the methods employed by Hainhofer to navigate his afflictions. It considers Hainhofer’s health-management strategies, paying particular attention to the prevalence of balms and perfumes. The following section considers the body of the duke. It discusses the ways in which Hainhofer communicated the affective properties of objects, and how this impacted their perceived value. Furthermore, I argue that objects within the cabinet demanded direct bodily engagement from Duke Philipp, intentionally designed to evoke a range of sensory experiences. It then turns to the body of the duchess, where I consider how Hainhofer and Duchess Sophia’s relationship was managed through the exchange of therapeutic materials. Finally, I discuss fluid bodies. This section demonstrates how artisanal bodies were tied into the same cosmology as Duke Philipp and Hainhofer: they were fluid, leaky, and humoral. It explores how they were affected by their craft, in turn influencing the production of the cabinet. It also examines Hainhofer’s relationship to the alcohol-based sociability of the workshop and the court, considering how this impacted his relationships.

Despite the destruction of the body of the Pomeranian Cabinet in 1945, there are a wealth of sources available: the contents of the cabinet remain preserved at the Museum of Decorative Arts, Berlin, as well as substantial extant manuscript material including Hainhofer’s extensive travelogues and correspondence. In particular, this article draws upon Hainhofer’s travel account (Reisebericht) from his visit to Stettin in 1617 to deliver the Pomeranian Cabinet. I have consulted the edition of the Reisebericht at the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, which is believed to have been Hainhofer’s personal copy.Footnote 26 I also draw upon the extensive correspondence between Hainhofer and Duke Philipp II, much of which was transcribed by Oscar Doering.Footnote 27

The correspondence is particularly instructive. As Vera Keller expresses, early modernity witnessed a cultural movement ‘of people eager to explore secrets of all kinds – secrets of art, secrets of the state, and secrets of nature’, with curiosity cabinets full of objects which ‘suggested how many more secrets remained to be explored’.Footnote 28 When writing to Duke Philipp, Hainhofer seldom revealed details about his plans regarding the intricacies of the cabinet, maintaining a level of secrecy that he saw as essential to its purpose.Footnote 29 This paucity of details regarding the cabinet’s internal organization prior to 1617 is contrasted by extensive details on materials, objects, and payments. The sources chart the rocky road trod by the merchant, requesting payments from as early as 1610 and discussing his thrifty negotiations with artists in 1611.Footnote 30 Above all, they reveal the intimacy between Hainhofer and Duke Philipp. Hainhofer’s frequent references to the value of materials, and centring of embodied experience, corporality, and health created a levelled relationship of refined interests and emotional affinity through which Hainhofer was able to strengthen their art-loving bonds. This began with Hainhofer’s ability to implicate his own corporeal experiences in the production of the Pomeranian cabinet.

II

Hainhofer’s body was deeply entangled in the early life of the Pomeranian Cabinet. Suffering from extreme vertigo, he often experienced spells of dizziness and sickness. Accounts of these episodes appear frequently in his extensive account of his 1617 journey. It was twenty days after his departure when Hainhofer and his retinue had arrived at the Stettin court, on 24 August. Yet only two days later, Hainhofer’s joyous arrival was marred by illness, and the merchant was visited by the court physician Dr Desiderius Constantin Oeßler, who would continue to care for Hainhofer during his time at the Stettin court. It was 7 o’clock on 26 August when Dr Oeßler visited Hainhofer for the first time, clearly making an impression on the merchant: Hainhofer describing Oeßler as a ‘learned, valiant and noble man’. Following their introduction, the physician visited Hainhofer ‘almost daily’, imparting ‘much sound advice’.Footnote 31 On this occasion, however, the advice of Dr Oeßler did not protect Hainhofer from being ‘tormented by dizziness and headaches’ later that same day. In a subsequent attempt to alleviate his condition, the dowager Duchess Sophia Hedwig of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1561–1631) had a medicinal water and powder prepared and sent to Hainhofer by her distiller.Footnote 32 On 7 September, Hainhofer was part of a party sailing a mile and a half down the river Oder, to visit Duchess Sophia Hedwig’s arable lands and court near to Kabelwicz. Hainhofer recorded that the duchess’s subjects were very taken with her ‘good nature and deeds’, describing her as intelligent, attentive, kind, and beautiful, displaying great care towards ‘the officers and servants, and towards the poor citizens’ by providing alms and materia medica from her court apothecary.Footnote 33 Sophia Hedwig was reputed for taking care of the sick and needy poor; her provision of therapeutic materials connects her with the tradition of noblewomen's healing and pharmaceutical activities in early modern Germany, recently investigated by Alisha Rankin.Footnote 34 Nevertheless, by 26 August, Sophia’s remedies had still not alleviated Hainhofer’s illness, with the merchant noting later that he was consuming only broth, due to his turbulent state.Footnote 35

Though partaking in many dining events, hunting trips, and tours of the duke’s Kunstkammer, Hainhofer’s months spent at the Stettin court were continually disrupted by illness. While visiting the court’s vineyards, situated one mile away from the castle, Hainhofer noted the dizziness he felt during the evening meal. It was at the beginning of the meal that the merchant recorded he was ‘severely afflicted by this dizziness, which made [him] feel like everything was falling’. Hainhofer was comforted by the presence of physicians at the table, as ‘counsellors and advisors of the soul and body’. After drinking a glass of Mumme – a dark beer brewed in Braunschweig – and a glass of wine, Hainhofer’s condition was much improved.Footnote 36 Yet the vertigo-like illness returned on 8 September, prior to a courtly hunting trip. The morning of the hunt, Hainhofer reported that he ‘was so dizzy [he] was not able to attend the midday meal’, choosing instead to sit alone.Footnote 37 The vertigo lasted for the following two days, allowing Hainhofer to leave the hunt early. He tried various remedies, including bathing in ‘Emperor Charles’s water for the head’. ‘God knows’, Hainhofer lamented, ‘this dizziness is an arduous and dangerous affair’.Footnote 38

Hainhofer sought help from a range of physicians during his 1617 journey, often noting down his observations regarding their efficacy. Having left Stettin in early September, on the 10th of October Hainhofer arrived in Cölln.Footnote 39 While visiting the Brandenburg court, Hainhofer was suddenly ‘struck by dizziness [while] in the front courtyard’, which was so severe that ‘had the doctor and servants not been there, would have caused me to fall’. Luckily for Hainhofer, the physician, Dr Magnus, assisted in taking Hainhofer by the arms and leading him to the court apothecary. Here, Hainhofer was given various efficacious powders and waters and fifteen minutes later, the merchant felt well again. This allowed him to marvel at the apothecary, which contained ‘all kinds of exquisite things, arranged in proper order’, installed by the former electress Catherine of Brandenburg-Küstrin (1549–1602), who ensured that all were able to obtain medicines ‘free of charge’.Footnote 40

Alongside a range of distilled waters and powders, Hainhofer frequently relied upon the application of rose-scented balms and perfumes to maintain corporeal balance. As will be explored further in part IV, rose-scented balms and perfumes assumed a central role within the pharmacy of the Pomeranian Cabinet, and provided a vector for diplomatic relationship-building. Rose scents (rose petal, attar, oils, and waters) were commonly employed in seventeenth-century German-language remedies, appearing in vernacular printed remedy books as well as court apothecary inventories.Footnote 41 For instance, at the Wolfenbüttel court (with which Hainhofer was later to become closely associated through his relationship with August II of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel), rose products were recorded in the court pharmacy invoices 766 times from 1610 to 1617.Footnote 42 The various waters, sugars, honeys, balms, oils, juices, and electuaries were intended for a wide range of recipients: from dukes and duchesses, to organ-makers, chambermaids, cooks, and journeymen.Footnote 43 Although rose was a widely used and incredibly popular apothecaries’ ingredient, Hainhofer appears to have distinguished his personal scent. In 1611, Hainhofer’s brother, Christoph, wrote to Hainhofer about ‘his’ (Hainhofer’s) specific scent, in relation to a request from the Archduchess Maria Magdalena of Tuscany for some of Hainhofer’s signature rose perfume.Footnote 44 I will return to Hainhofer’s use of his trademark rose scent, and its importance for his marketing strategy in part III, but here it is important to observe how Hainhofer paid close attention to the presentation and management of his body.

The interplay of matter, sensation, and corporeal health dominated Hainhofer’s life not only in terms of his personal health, but that of his family. His Pomeranian travel account begins with the untimely death of Hainhofer’s ‘oldest [and] dearest little son’, who was ‘taken away from’ Hainhofer in the early hours of the morning. Little Philipp, the namesake and godson of the duke, was almost six years old when he died.Footnote 45 The death accounts for Hainhofer’s inclusion of several morbid prints in the pages that follow. First is an Allegory of death by Jacob van der Heyden (Figure 4), in which a skeleton is scaling the walls of a turret. The anthropomorphized building takes the form of a head: the skeleton is entering through its eye.Footnote 46 The image is surrounded by a biblical verse (Jeremiah 9:21): ‘Death has climbed in through our windows and has entered our fortresses.’ In the book of Jeremiah, this verse continues, ‘it has removed the children from the streets’, a clear reference to Hainhofer’s loss. The piece combines the embodied experience of grief with his Lutheran beliefs and tangible, anthropomorphic matter. Overleaf is another image from van der Heyden, of Death, wearing a crown of roses (Figure 5). Death is pointing the arrow of ‘Today’ at the viewer; the arrow of ‘Tomorrow’ awaits in Death’s sheath, while the arrow of ‘Yesterday’ lies broken on the floor. An hourglass is resting by Death’s feet, encompassed by the phrase: ‘Consider death and judgement and you will do no evil.’Footnote 47 Mourning the loss of his child, Hainhofer reveals himself to be deeply conscious of corporeal fragility, and of the importance of managing the spirited, tangible body.

Figure 4. Jacob van der Heyden, Allegory of death, in P. Hainhofer, Relatio vber Ph. Hainhofers Rayse nacher Pommern. 1617, fo. 4r, Cod. Guelf. 23.2 Aug. 2°. © Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

Figure 5. Jacob van der Heyden, Fleuch wa du wilt…, in P. Hainhofer, Relatio vber Ph. Hainhofers Rayse nacher Pommern. 1617, fo. 4r, Cod. Guelf. 23.2 Aug. 2°. © Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

Hainhofer’s expressions of suffering at the death of his child were consistent with Lutheran practices surrounding grief and consolation. The practice of writing about one’s suffering was intended as a restorative practice, providing both spiritual and ‘physical remedial’ healing: ‘Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh, I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church’ (Colossians 1:24). To some extent, Hainhofer’s approach to suffering embodied this scriptural proverb. Though often suffering physically, he found solace in nurturing his spiritual body: ‘I have often found that the Almighty is strong through [our] weaknesses.’Footnote 48 Life, however, was not without pain and tragedy for Hainhofer, and his writings express his frustrations at his own frailty. This was in keeping with Lutheran practices, deploying rhetorical devices as a form of consolation, rather than seeking to ‘repress or control feelings’.Footnote 49

Hainhofer’s faith, and its relation to both material objects and his corporeal body, was a central part of the Pomeranian Cabinet project. Included in the ‘writing desk’ portion of the Pomeranian Cabinet was a ‘beautifully bound’ edition of the Lutheran theologian Philipp Kegel’s Twelve devotions (1613).Footnote 50 This prayer book, written in both Latin and the vernacular, ‘devoted much attention to repentance, meditated on the sufferings of Christ, and suggested prayers for use by the sick and dying’.Footnote 51 In his description of the cabinet, Hainhofer lists the devotional book as kept in a drawer next to an hourglass; a clear reference to the temporal, fragile human body, just as in van der Heyden’s image. Hainhofer’s personal experience of the body, both corporeal and spiritual, found expression in the material forms of the Pomeranian Cabinet. As Barbara Mundt observes, the book was an unusual inclusion for an art cabinet, given collectors often established libraries alongside their Kunstkammer collections. The Pomeranian Cabinet contained three books, two of which were manuals included in the drawers of scientific instruments. Kegel’s prayer book was ‘surely [intended] to please the pious duke, a work not of the earthly search for knowledge, but of faith’.Footnote 52

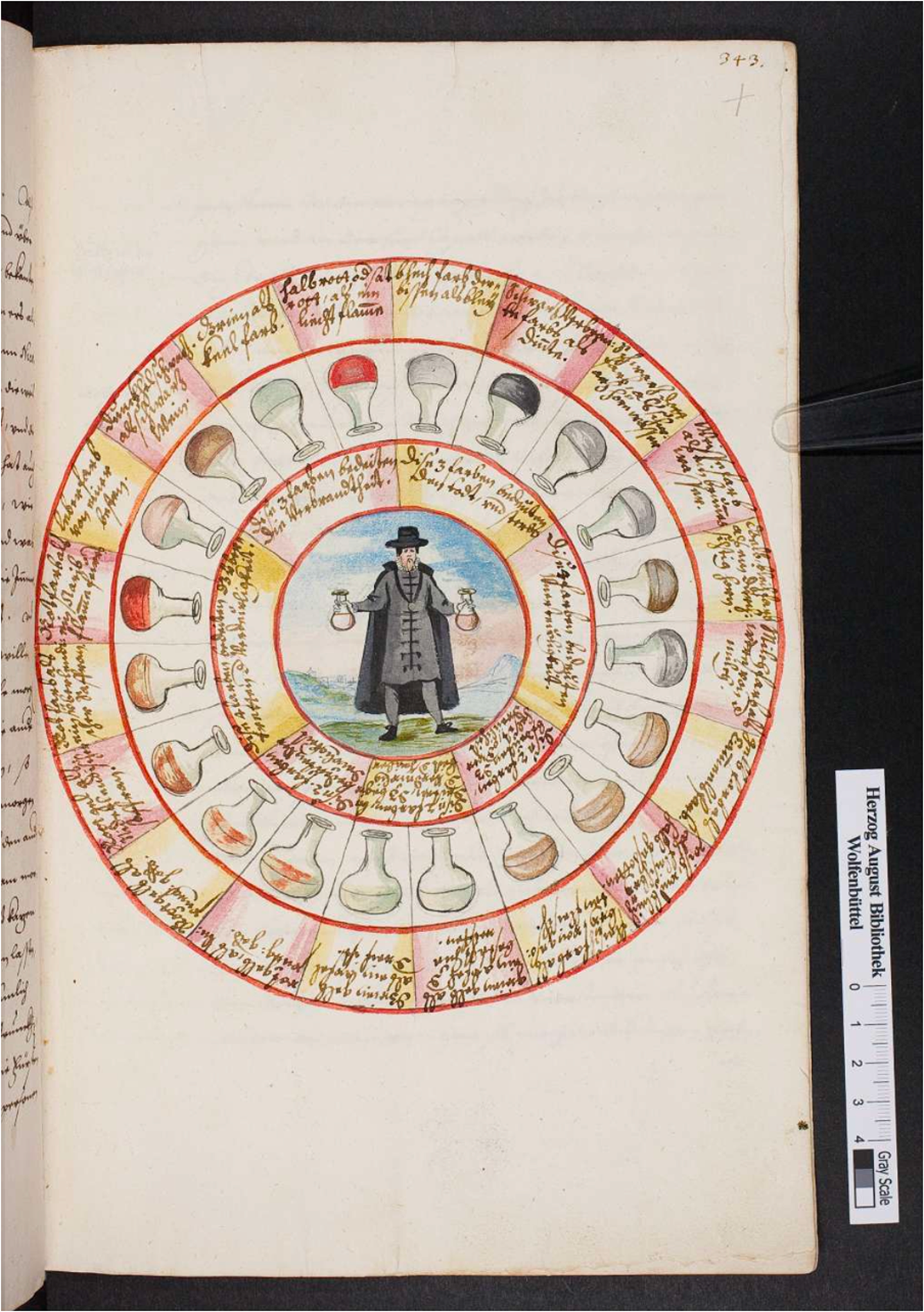

Hainhofer’s interest in medicine further permeates the Pomeranian travelogue through his inclusion of a urine chart (Figure 6), noting in the opposite folio that ‘there has been much discourse regarding urines, and what colours they are’.Footnote 53 Drawn directly onto the folio, with clear underdrawings to position the different vials neatly, the image shows twenty vials of urine, each a slightly different colour. Each vial has accompanying text describing the colour. The section follows Hainhofer’s short discussion of his visit to the Dresden court, where he was shown around the court by the Swiss sculptor and architect Giovanni Maria Nosseni (1544–1620). In particular, it follows Hainhofer’s description of a mealtime discussion on the illness and death of Elector Christian I of Saxony (1560–91), who was cared for by several of Hainhofer’s fellow diners. Hainhofer briefly discusses the different approaches to treatment taken by the physicians, before discussing the art of urine charts.Footnote 54 Hainhofer’s interest in treatments is evident in his travelogue – a document intended to market himself to potential clientele.

Figure 6. Urine Chart in P. Hainhofer, Relatio vber Ph. Hainhofers Rayse nacher Pommern. 1617, fo. 343r, Cod. Guelf. 23.2 Aug. 2°. © Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

In exchanging information about his health and therapeutic practices, Hainhofer was actively invoking the body as a means of forming intimate networks. Crucially, Hainhofer’s ability to do this centred around the care, attention, and understanding he demonstrated regarding his own health practices. In doing so, he positioned himself as deeply attentive to the experiential knowledge (kennen as opposed to wissen) which historians such as Pamela Smith and Harold Cook have demonstrated was fundamentally important to merchants, diplomats, art-lovers, and artisans in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe. Hainhofer not only affirmed his own corporeality in the process of constructing the Pomeranian Cabinet but employed ‘health’ as a key vector for relationship-building with his eminent patrons, connecting their disparate corpora to his.

III

Over the course of the construction of the Pomeranian Cabinet, Hainhofer and Duke Philipp were engaged in extensive correspondence. These letters reveal not only the extent of their relationship, but also the ways in which they related to and contemplated the objects and materials constituting the cabinet. Throughout the course of Hainhofer and Duke Philipp’s relationship, the duke experienced a worsening physical condition. As Barbara Mundt notes, the duke’s leg infection in 1612, which caused him to seek out treatments from a healing well in Lüneburg, was ultimately secondary to Duke Philipp’s long-term illness that likely caused his death.Footnote 55 While Hainhofer does not elaborate on the nature of this illness, he demonstrates keen awareness of the duke’s fragile health, even if he later reported being taken aback by the severity of Duke Philipp’s condition when he was informed of it during his return trip to Augsburg.Footnote 56

Hainhofer repeatedly communicated a deep awareness of natural materials that could heal and protect the body of his patron. In 1611, he detailed a variety of precious stones he had sent to Duke Philipp for the cabinet. This shipment included jasper, agate, carnelian, and malachite. These stones, Hainhofer noted, were ‘considered strange’ and could be ‘used for [both] good and evil’.Footnote 57 Hainhofer also sent Duke Philipp two green jasper stones incised with scorpions. These stones were not only decorative but were intended to be used to stop bleeding.Footnote 58 That Hainhofer emphasized the functional aspects of these stones carries twofold meaning. Firstly, that the affective properties of materials increased their desirability. Secondly, though these natural materials possessed great affective power, the power of natural materials was unstable and could be manipulated to different ends. As such, Hainhofer’s letter to the duke served as a warning, a display of his known knowledge, and as a sales pitch.

At times, Hainhofer more precisely described the affective properties of materials. On receiving a shipment from Portugal, sent from the Florentine jeweller Vincenzo Dinello, Hainhofer commented on two dishes made of rhinoceros horn, confirming to the duke that the material was ‘very good against poison’.Footnote 59 The horn’s use as dinnerware highlights the relationship between food, ingestion, and the threat of toxic matter. According to Alisha Rankin, the period witnessed the very real ‘threat of attempted poisoning’, ‘used as a tactic in political manoeuvring’. Such a threat ‘diminished the power of the prince’ with ‘the search for antidotes…therefore tied up in an age-old effort to maintain both the prince’s health and his air of invincibility’.Footnote 60 This is something of which Hainhofer was cognizant: during a 1603 visit to the Munich court, he recorded the story of Duke Maximillian I’s chief equerry, Astor Leoncelli, who was executed in the same year. Leoncelli was imprisoned alongside Maximilian’s stable hand, who had been interred for an attempted poisoning of the duke.Footnote 61

The well-being of the duke was most explicitly addressed in the cabinet’s pharmacy, the first part of the cabinet to be constructed.Footnote 62 The pharmacy of the Pomeranian Cabinet was substantial, with Hainhofer’s written account of its contents and iconography spanning fourteen folios of the Pomeranian travelogue. This cabinet was unique in holding such a considerable pharmaceutical section; it was more typical to include small, hand-held ‘pharmacy’ units in cabinets, as opposed to entire drawers. Hainhofer’s lengthy description of the Pomeranian pharmacy comprised part of a manual that was subsequently included as an item within the cabinet, instructing the reader how to navigate the cabinet’s intricate drawers and mechanisms, as well as detailing its contents and iconography. In the first instance, the pharmacy could be identified by the lock and key resembling ‘a mortar with its pestle, signifying the apothecary’.Footnote 63

While the pharmacy could be reached with the Parnassus crown of the cabinet and the drawer of barber’s items still in place, it would be ‘advisable, better, and easier to lift, when they are removed and placed underneath’.Footnote 64 Hainhofer’s advice to Duke Philipp on how to properly access the materials of the pharmacy continues in his directions on how to ‘discover a hidden section’ containing a small pharmaceutical container, by ‘lifting a velvet-covered panel’.Footnote 65 Significantly, etched onto this chest are various coats of arms: on one side, the two princely coats of arms of Duke Philipp; on the other, the coat of arms of the City of Augsburg, bearing the inscription ‘Philipp Hainhofer…1616, by whom this writing desk was made and was given’.Footnote 66 Here, the duke, Hainhofer, and the master artisans of Augsburg were connected through the iconography of the pharmacy. If Hainhofer wanted to use the Pomeranian Cabinet to bring the duke closer to Augsburg's achievements in the arts and sciences, ‘hardly anything could be more suitable’ than the pharmacy.Footnote 67 According to Hainhofer, this section was so hidden that those who did not know of it would ruin the cabinet before they were able to find it.Footnote 68 That access to the pharmacy was neither easy nor evident without instruction speaks to the particularly privileged, ingenious, and playful knowledge Hainhofer made available to his patron.

Not only was it crucial that the duke was able to easily access the contents of these drawers, but it was also clear that the items were intended to be removed in order to be used. In his instruction booklet, Hainhofer first described two spherical devices for heating and cooling the body. The first, made of silver, had a section that unscrewed to reveal a steel pin. The pin was to be taken out and heated over embers, before being placed back into the ball, conductively heating the device. This was to ‘be used to warm your hands in the winter’. The neighbouring device was made of crystal, whose cool surface was intended to ‘cool your hands down in the summer and freshen around the eyes’.Footnote 69 Further into the booklet, Hainhofer described an iron press, used to make juices out of various herbs (Hainhofer recommended ‘currants’, a common medicinal ingredient, or ‘anything else you may want to strain’). After explaining the screw-tightening mechanism to press juices, Hainhofer then described how to remove the press to clean it, noting that once removed, it could also be used in letter writing, to stamp seals.Footnote 70 Clearly, the reader – Duke Philipp – was not going to observe these items, but actively engage with them.

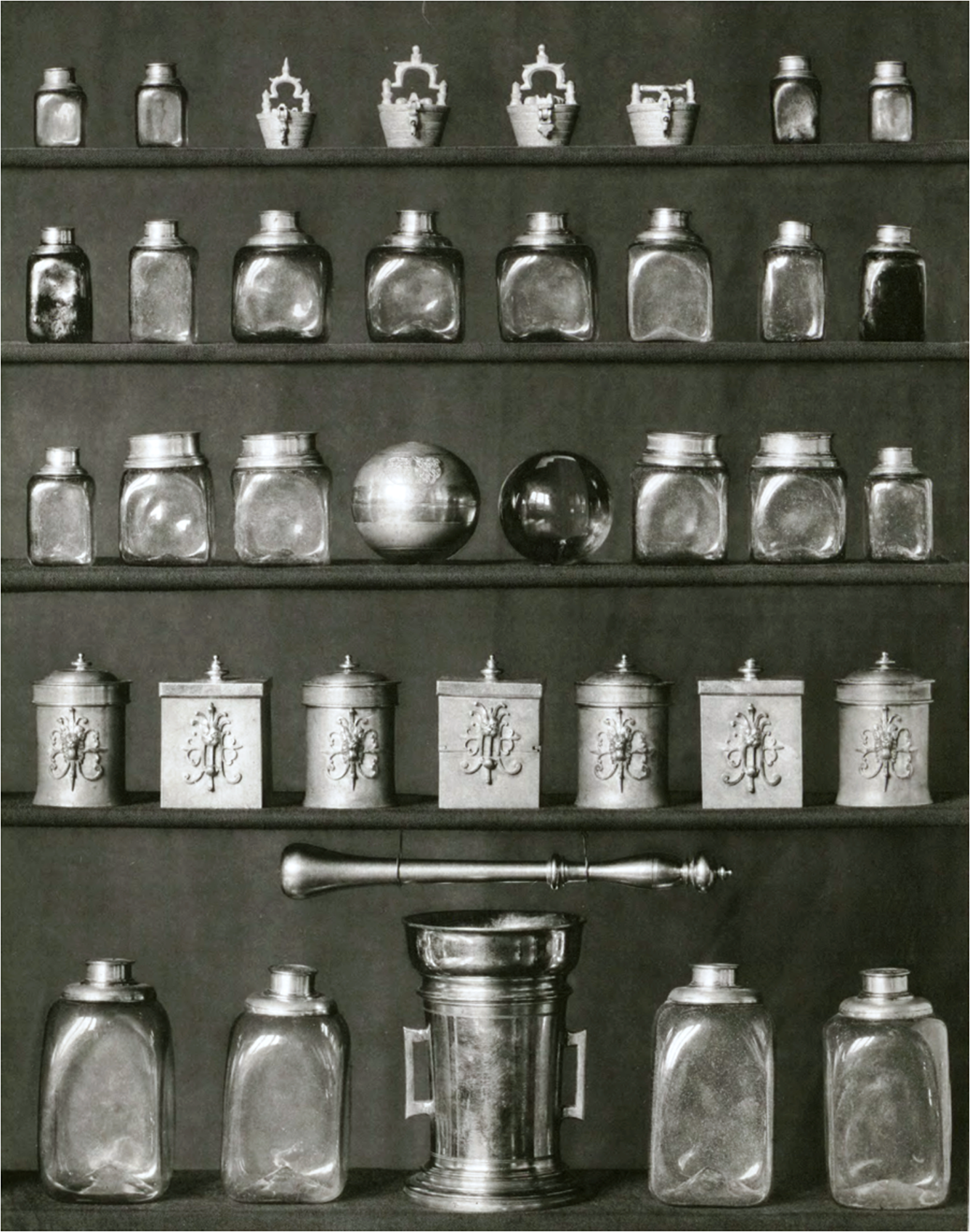

While the Pomeranian Cabinet contained ‘only a small number of pharmaceuticals’ – with many of the thirty-two jars left empty for the ducal couple to fill from their own court apothecary – Hainhofer did include a range of scented balms and perfumes.Footnote 71 They are among the first items one encountered upon opening the lid to the pharmacy: firstly, ‘four round and five square silver boxes, for conserves, sugars, oils, creams and such like’ (Figure 7).Footnote 72 As one delved further into the various compartments and drawers, there were an additional three rows to the rear with ‘six large glasses of oil, water, sugar, all with silver engraving, and in the forward most row, two flasks filled with oriental and occidental balms’.Footnote 73 Olfactory materials proliferated: ‘When one takes out these inserts, in a drawer made of cypress wood, are three apples of musk, to smoke. In a glass jar, there is a balm made from mace’, an ingredient known as ‘a panacea for fainting, palpitations, stomach ailments [and] vomiting fits’.Footnote 74 Lastly, one came to a ‘balm-box’ filled with various herbs, and ‘a sectioned box of rose balm and whipped balm’.Footnote 75 Clearly, the perishable ingredients contained within the pharmaceutical section of the cabinet were intended for use.

Figure 7. Pommerscher Kunstschrank – Ausstattung Apotheke, in Julius Lessing and Adolf Brüning, Der Pommersche Kunstschrank, Königl. Kunstgewerbemuseum (Berlin, 1905). Public Domain.

Nearing the end of his stay at the Stettin court, Hainhofer summarized his last dinner with the ducal couple, which was followed by a lyric verse, in which the corporeal, spiritual relationship between Hainhofer and Duke Philipp was clarified, playfully drawing on their shared names: ‘The united minds of the Philipps were separated, the Pomeranian leader to the new Stettin, Hainhofer to [Duke] August…because of the distance of these places from one another, and the weakness of both Philipps, our parting on both sides, especially with me, is hard on my heart.’Footnote 76

In many ways, Hainhofer embodied a contradiction. He was both a man of action and a man of fragility. As I return to in part VI, Hainhofer encapsulated Todd Reeser’s notion of ‘moderation’ as the defining feature of early modern masculinity, partially manifested in his careful moderation of the body.Footnote 77 Duke Philipp also embodied this tension between sensitivity and virility, seeking to expand his status as patron of the arts beyond the Pomeranian territory while battling ill health. The duke’s health and well-being lay at the centre of the cabinet, and Hainhofer’s inclusion of such a significant sized pharmacy spoke to the importance he placed on this. This served as a vector through which Hainhofer nurtured their relationship.

IV

The materia medica with which Hainhofer dealt were not exclusively for the benefit of the duke. In June 1611, Hainhofer enclosed a letter to the duke and duchess ‘from Florence from the princess, the grand duchess in Tuscany’: Archduchess Maria Magdalena of Tuscany (1589–1631). The letter requested that Hainhofer ensure that the accompanying case of ‘twenty-four costly balms and powders’ be delivered to the duke and duchess. Hainhofer added that the case had been forwarded to Stettin without having been opened, and that ‘your grace shall receive it soon, [and] without doubt your highness and the princess will love this stately gift and find it pleasing, and it will begin the cultivation of diplomatic gifts in the Kunstkammer’.Footnote 78 The valuable gift – which signified the development of the duke’s Kunstkammer and his position as an art-loving prince – was intended for the enjoyment of the ducal couple.

As with the contents of the Pomeranian Cabinet, balms and perfumes formed an integral part of Hainhofer’s commission for the ducal couple. A silver sewing basket, proposed by Hainhofer alongside the cabinet in 1610, was initially intended as a New Year’s gift from the duke to his wife, but did not arrive until 1612. The delay was justified by Hainhofer, who praised the careful work of the eminent Augsburg artisans employed, including the automaton-maker Achilles Langenbucher and goldsmith David Altenstetter.Footnote 79 When the basket was eventually received by Duchess Sophia, it contained perfume which ‘serve[d] to strengthen the head’.Footnote 80 Hainhofer was clear on the value and quality of the therapeutic items in Duchess Sophia’s sewing box. He wrote that they were filled by ‘the most famous apothecary in Germany’, Augsburg’s Hans Georg Sighart, who ensured that they were ‘made with great diligence’.Footnote 81 Once more, Hainhofer combined therapeutic efficacy and master craftmanship in marketing his wares.

Duchess Sophia’s interest in Hainhofer’s balms was not surprising. Hainhofer appears to have relied upon these olfactory-therapeutic materials to develop his relationships with (predominantly) female patrons across confessional divides. In this regard, Hainhofer did not appear to discriminate. At the same time as he was curating perfumes and balms for Sophia, Hainhofer was procuring perfumed goods for Maria Magdalena.Footnote 82 In 1611, Archduchess Maria – corresponding with Hainhofer through the intermediary of his brother Christoph in Florence – wrote specifically asking for some of Hainhofer’s signature scent. In this letter, Maria labelled these rose-scented items both ‘delectable’ (köstlich) and ‘good’ (guet),Footnote 83 assigning a moral, humoral quality to the substance. As with the properties of tangible matter, the effectiveness of ephemeral materials like scents were not fixed: that certain scents were specifically designated as ‘good’ reveals the possibility of ambivalent affect.

Two years later, Hainhofer again turned to scented balms as suitable gifts for his most eminent patrons. On 14 July 1613, Duke August of Brunswick-Lüneburg received a letter from Hainhofer stating that ‘I will send the promised case of balm for the most serene and most sweet, your lady, with the next standard.'Footnote 84 Though writing to the duke, it is clear that the scented items were intended for his first wife, Clara Maria of Pomerania-Barth. Seven days later, Duke August replied: ‘the sending of the balm boxes would be unnecessary, but because it pleases you so much, my wife will be careful of ways and means to compensate you for such a thing’.Footnote 85 The gift was evidently not commissioned by the couple, evidencing a degree of agency from Hainhofer, influencing the materials sent to patrons.

Hainhofer’s material investment in his relationship with the Duchess Sophia appears to have been rewarded. Both the Duke Philipp and Duchess Sophia expressed clear fondness for Hainhofer upon his visit to the Pomeranian court. In the Pomeranian travelogue, Hainhofer records how the duke and duchess prepared a room for his arrival. Seemingly aware of Hainhofer’s bouts of ill health, the duke and duchess showed great ‘consideration of their guest’, ensuring that a floral and herbal wreath had been moved from the rooms of the ladies-in-waiting to the guest quarters.Footnote 86 In early September, as Hainhofer was preparing to leave the Stettin court, gifts were presented to him by members of the ducal family. Duke Ulrich, Duke Philipp’s brother, gave Hainhofer preparation made from antler, which ‘in strength and virtue is almost equal to the unicorn’ and could ‘strengthen [one] in weakness and drive fear from the heart, just as it did so effectively for the princess’.Footnote 87 Here, Hainhofer referred to Duchess Sophia’s illness of 1615, described in a conversation between Hainhofer and Duke Philipp elsewhere in the travelogue.Footnote 88 Like Duke Ulrich, Duchess Sophia also gifted Hainhofer a chest of the efficacious fired antler.Footnote 89 Both gifts were entered into Hainhofer’s personal store of goods, and later included in one of Hainhofer’s ‘artful, exquisite and useful’ cabinet creations. In a letter to Duke August which included a detailed description of the cabinet and its contents, Hainhofer identified a hidden drawer which contained the ‘fired antler [that is] snow-white’ from ‘Duchess Sophia in Pomerania’, as well as an ‘antler prepared by Elector Johann Sigismund of Brandenburg’s own hand, without the use of fire’.Footnote 90

Not all of Sophia’s gifts had therapeutic inflections; she gave Hainhofer a diamond and ruby ring, inscribed with an ‘S’, for his wife Regina. Nonetheless, the exchange of therapeutic materials between Hainhofer and Sophia – alongside Hainhofer’s emphasis that these same ingredients were part of their own health regimen – demonstrates the central role of medicine and the body in consolidating the relationship between patron and merchant. Philipp and Sophia were concerned with Hainhofer’s health during his visit and were well aware of techniques of health management. Here, the idea that scents could ‘strengthen the head’ was repeated, in relation to Hainhofer’s own body, drawing parallels between the ways in which scented objects could affect both merchant and female patron, thus constructing the body of the art-lover as sensitive, ambivalent, and unisex.

Much can be gauged from Hainhofer’s emphasis on scents and perfumes, especially with regard to his relationship with aristocratic women. The distribution of scents and balms – objects which explicitly aimed to restore and balance the humoral body – held both corporeal and diplomatic significance. As Jemma Field writes, ‘the early modern body was not a neutral or natural being, but a socio-political entity constructed through the considered use of apparel, accessories, and movement’.Footnote 91 This argument can be extended beyond visual display, to consider the politics of sensory experience. Just as ‘specific sartorial and jewellery choices…could legitimize a position, visualize political ambition, or show allegiance, favour, or dynastic membership’, so could scents.Footnote 92 Often selected as items to show diplomatic favour, these balms and perfumes demonstrated the sender’s awareness of, and care for, the bodies of the patron.

Beyond this, they attested to notions of physical proximity and familiarity. To know the scent of another was to know their physical presence, demonstrating a closeness of bodily relationship that transcended the written word. This recalls and develops Alfred Gell’s anthropological concept of ‘distributed personhood’, whereby not only are ‘things’ active agents which can extend past the bounds of the body but can themselves possess what Gell calls the ‘primordial inside–outside relation’.Footnote 93 Hainhofer’s use of scents evokes the question of how individuals distribute themselves through ‘things’, and what behaviour this elicits in others. This was not uncommon for the merchant. When on a trip to Munich in 1611, Hainhofer recorded his use of the scent while in conversation with Ferdinand of Bavaria, elector of Cologne.

Before I left, your Highness asked me, how is it that I always smell like roses? [And] whether I have rose water in my pouch, on my neck, or in the cross. Then I showed your Highness that I had nothing on my neck other than a chain, and in a health-cross [pendant], a yellow amber heart, with a portrait of the Pomeranian [duke] in it, [then] your Highness said: You two Philipps [Hainhofer and Duke Philipp of Pomerania Stettin] must love each other very much, then what on you smells of roses? Then I applied the balm that I had in my small box, sometimes in front of my hat, to my hands, just as I had done in the chapel, so that the princesses looked around, not knowing where the lovely smell came from.Footnote 94

This passage was followed with a note from Hainhofer saying that such a scent instilled a prevailing feeling of calm, though he did not allude to whether this was in regard to himself or others in the room. The attention paid to his balms and perfumes by his patrons demonstrates the mutuality of the art-loving, sensitive body, and a shared participation in this material community: it reveals an attention paid to Hainhofer’s own body (which he intentionally cultivated), and how both the duke and duchess – and others involved in Hainhofer’s network – actively participated in the strengthening of this sense-scape.

V

Just as the Pomeranian Cabinet reflected the intertwined corporeal and therapeutic experiences of the ducal couple and Hainhofer, it was equally shaped by the bodies of artisans, the majority of whom resided in Hainhofer’s hometown of Augsburg. In the instruction booklet of the cabinet, Hainhofer described an embedded panel, painted by Anton Mozart, depicting the most eminent artisans, with each figure carefully labelled on the panel’s reverse (Figure 8). A total of twenty-five artisans are depicted, among figures such as Duke Philipp, Duchess Sophia, Hainhofer, and his son Philipp (the painting was created prior to young Philipp’s death).

Figure 8. Anton Mozart, Die Übergabe des Pommerschen Kunstschranks, 1614–15, Augsburg, oil on wood, 45.4 x 39.5 cm, © bpk – Bildagentur / Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz / Karen Bartsch.

Hainhofer paid close attention to the bodies of his artisans. Indeed, he found it practical to do so. When writing to Duke Philipp attempting to justify delays in production by explaining the practical and physical difficulties involved in crafting such a complex commission, such as ‘inventions with hidden components’; intricate mechanisms and concealed drawers that made the cabinet a magnificent, complex, and deeply intimate object. In completing such skilful and artistic pieces, artisans’ bodies often suffered the ravages of craft practice. Later that year, while discussing the creation of a pair of ornately decorated serviettes, Hainhofer explained that the artisanal process ‘requires great effort, lots of time and terribly damages the fingers, removing his [the artisan's] skin’.Footnote 95

The bodies of Hainhofer’s artisans were not only influenced by their work on the cabinet, but their bodies in turn influenced its production. Though delays in the cabinet’s completion were often justified by recourse to complex designs and the physicality of labour, Hainhofer also frequently bemoaned the drinking habits of his artisans, specifically those he referred to as ‘wet brothers’ (nassen Brüder).Footnote 96 Having already complained about the drinking habits of his favoured artist, Johann Rottenhammer, Hainhofer wrote to Duke Philipp that the painter ‘Achilles [Langenbucher] does the same thing; [one] can’t get anything from him, but [he] waits to drink from morning to evening…otherwise he makes excellently beautiful landscapes’.Footnote 97 Hainhofer went on to conclude that, despite Achilles’s talent, he would only commission him to create one further piece for the cabinet, as he ‘doesn’t have any work left in him’.Footnote 98

Although the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw novel contributions to medical knowledge, Phil Withington convincingly argues that there was no paradigm shift. ‘Medical knowledge’, he writes, ‘whether herbal, astrological, classical, or chemical, all directed at restoring and maintaining humoral equilibrium, and rather differed in the medicines they selected to do so.’Footnote 99 Drunkenness had clear consequences for the humoral body. As something which ‘softened boundaries between the personal and the social’, it also acted not only as a social lubricant, but something which disturbed the boundaries of the fluid body, threatening spillage.Footnote 100 Entrenched in the humoral system, alcohols had varying effects on individuals depending on their temperament and constitution.Footnote 101 They were typically identified with characteristics that followed the binary pairs of hot/cold and wet/dry. For example, while beer was believed to be cold and wet, wine was generally hotter and drier. As artists and artisans were amongst those commonly associated with the cold, dry, melancholic temperament, experiencing an excess of the humoral fluid of ‘black bile’, the ingestion of a primarily ‘cold’ drink such as beer threatened the careful balance of humours.Footnote 102

In contrast, despite its general association with heat, good wine was understood to embody ‘positive properties of all four humours, [and] many physicians understood it as a general remedy for nearly any kind of humoral imbalance’.Footnote 103 Wines frequently featured in early modern recipe books, incorporated into medical recipes as a curative for a range of maladies. In the general medical remedy book of Johannes Wittich (1612), white wine was humorally cooler than red or brandy wines.Footnote 104 Red or ‘warm’ wines were most frequently suggested, especially for treating menstruation and childbirth, with Ann Tlusty observing that the warm qualities of wines ‘were considered beneficial for counteracting the natural coolness of the female temperament’,Footnote 105 or, indeed, the melancholic. Meanwhile, white wine was used in Wittich’s remedies for cooling angry rashes.Footnote 106 Different alcohols had vastly different corporeal affects depending not only on the nature of the alcohol consumed, but the nature of the individual consuming it.

Hainhofer displayed a willingness to drink ‘whenever this seemed professionally, politically, or socially necessary’,Footnote 107 including with his artisans. It is wine which Hainhofer most frequently recorded himself drinking in his Pomeranian travel account and correspondence, such as the several glasses of wine he drank with his favoured artist Johann Rottenhammer.Footnote 108 As such, though bemoaning the habits of his artisans, Hainhofer did not repudiate alcohol outright. Occasionally, he deemed it appropriate for times of merriment, jest, and dining. In a 1611 visit to the Munich court and Kunstkammer as an official guest of Duke Wilhelm V, Hainhofer described how he witnessed ‘His Serene Highness Duke Maximilian with his wife, his brother Duke Albrecht, and his little sister, Duchess Magdalena’ dining with the court fool.Footnote 109 Hainhofer reported upon the jovial comments of fool: ‘when he sees someone with a red face, he says to him, “You’re just as drunk as I am, when I look at you I’m thirsty!”’Footnote 110 While Hainhofer appears to have enjoyed the jester’s alcohol-induced antics, he follows this with a print copy of a moralizing poem ‘written to three doctors and personal physicians, for those suffering from wine and drunkenness’, in which the complainant begs the doctors to alleviate the consequences of his ‘disobedient stomach’.Footnote 111

Equally, when Hainhofer visited the Stettin court, he appeared willing to engage in alcohol-based sociability when absolutely necessary. As I have shown in part I, there was occasion when Hainhofer believed alcohol consumption – fundamental to the fabric of court life – was not detrimental to his condition: ‘as I was drinking a mug of Braunschweig Mumme and a glass of Spanish wine, [my dizziness] got better, praise God’.Footnote 112 On a later occasion, during his return travels from the Stettin court, Hainhofer recalled how a dinner at the house of physician Dr Hans Georg Magnus ended with drinking late into the evening (until midnight), where guests ‘drank heartily to the health of the lord prince’. Yet, such consumption was only beneficial in moderation, or when the alcohol was diluted. Only a few days later, during a visit to Dresden, Hainhofer recalled his party’s visit to a reputed wine merchant ‘who gave us a good glass of wine, which, when mixed together with herbs, should not be harmful to drink’. Though this wine was safe to consume, there was an implicit understanding that this was not always the case.Footnote 113

Overwhelmingly, Hainhofer abstained from drinking alcohol in the stronger forms of wine and spirits, on the grounds of his health. On one occasion, when dining with Duke Philipp’s brother, Duke Ulrich, Hainhofer bemoaned drinking ‘a large amount of French wine (which was probably half brandy), [as] it burned my throat and caused me such pain that the following day, I had to engage a physician and barber-surgeon to ward off the heat’.Footnote 114 Hainhofer not only appeared to regret instances of drinking, but often actively refused to partake. His abstinence was supported by the ducal couple, who were well aware of the dizziness and vertigo Hainhofer experienced. On a visit to the court’s winery, the merchant wrote that the duke and duchess ‘shielded me from excessive drinking the entire time I was in Pomerania, [as] they well understood that it was not suitable for my troublesome guest, the vertigo’. Hainhofer continued, noting that the Stettin court was ‘very temperate’, with no ‘excesses in abundant or disorderly drinking’ observed.Footnote 115 In positioning the Stettin court as one not centred around alcohol consumption but rather around engagement with art and nature, Hainhofer actively constituted the duke and duchess of Pomerania’s reputation as moderate, art-loving rulers.

This attitude towards alcohol, heavily contingent on the nature of consumption, was reflected in the Pomeranian Cabinet itself. Alcohol’s link to joviality and pastimes was evident. When discussing the various board and card games included in the cabinet, Hainhofer discussed a drinking game, involving an ebony board with a range of dice. On one of these dice, letters signified different ‘moves’ for the players to follow, including L. S.: leave standing (lass stehen); N. H.: take half (nimm halb); and T. A.: drink up (trink aus).Footnote 116 Hainhofer also alluded to the medicinal properties alcohol could have, by including ‘two silver and two glass flasks’ to be filled with wine in the pharmacy. Significantly, wine is specified as humourally amenable to the artist and art-lover. Yet again, such consumption required qualification. The flasks were engraved with the Pomeranian and Dutch coats of arms, and, importantly, the figure of ‘Temperance’.Footnote 117 As with his artisans, and the Munich court jester, moderation was essential.

Alcohol consumption, and its bodily and social consequences, played an important role in shaping the course of both the cabinet’s construction and reception. Ultimately, Hainhofer’s attitude to the embodied impact of excessive alcohol consumption related to the ability of his artisans to work effectively, as well as his anxieties about managing the fluid body. That Hainhofer was willing to drink in these contexts – despite his complaints about the impact of drunkenness on production and his own physical health – indicates that he saw alcohol as a substance with social benefits, in so far as it helped shape the conditions for productive relationships. It both distinguished between and connected bodies.

VI

Hainhofer’s extensive correspondence and his detailed travel account from his visit to the Pomeranian court reveal much about the relationships between materials, senses, and the body; for the ducal couple, for the makers of the cabinet, and for Hainhofer himself. The story of the Pomeranian Cabinet lies at the intersection between body and object, a once-tangible representation of how Hainhofer expertly negotiated his relationships with those who could impact his career. The materials and objects included in the Pomeranian Cabinet tell a story of corporeal wellness, anxieties, and the material parity between the body and the natural world. Affective materials, such as rhinoceros horn, held twofold significance: they demonstrated Hainhofer’s unique access to cross-cultural networks of patronage, and the importance he placed on physical well-being. Especially revealing are the contents of the cabinet’s pharmacy, carefully curated to ameliorate and sustain the health of Hainhofer’s eminent patrons. Though the materials and objects incorporated into the cabinet possessed therapeutic properties, and their affective properties were sometimes ambiguous and ambivalent. The materials of the pharmacy had clearly defined roles. The wide range of perfumes, balms, oils, and waters included in the pharmacy are particularly revealing. Hainhofer’s written instructions reveal a high level of agency and engagement for the user to whom this restricted knowledge had been revealed; able to remove, apply, and refill the various jars of perishable contents.

That specific requests were made for Hainhofer’s signature rose scent reiterates the performative power of olfactory materials: to know Hainhofer’s scent implied physical proximity. Experiences of his own body indelibly shaped Hainhofer’s relationship to the Pomeranian Cabinet, and to its eventual owners. His frequent and liberal application of rose scent not only established his physical presence within a space. It also signified to those around him that he was experiencing bouts of dizziness and sickness. This became a fundamental basis for Hainhofer’s relationship to the ducal couple. He expressed this through the inclusion of olfactory matter in the pharmacy, and Philipp and Sophia in turn adjusted for Hainhofer during his visit to their court.

It was not only the bodies of patrons and merchant inextricably tied up in the production of the Pomeranian Cabinet within a nexus of persistent and percolating medical cosmologies and materialities. The bodies of the artisans working on the cabinet were physically marked by their craft, in turn extending the production timeframe of the piece. Their drinking habits compounded these delays and were a source of frustration for Hainhofer. Nevertheless, in line with humoral understanding, Hainhofer did not completely rebuke alcohol consumption. Rather, it depended on the nature of alcohol, the temperament of the drinker, and the context within which one drank.

Corporeal health fundamentally shaped the Pomeranian Cabinet in terms of its construction, contents, and delivery. The bodies of geographically, socially, and confessionally diverse individuals were intertwined in its early life, tied together by humorally centred cosmological understandings. By directing our attention towards health, sensation, and medicine, the material basis of the Pomeranian Cabinet is brought into sharp relief. What this article ultimately demonstrates is the process through which the body of the art-lover was constructed, convening with those engaged in a shared material community through the lens of health and bodily entanglements. Hainhofer was a merchant and secret agent, occupying a dubious position. Through the staging of the shared, art-loving body, he was able to create and sustain friendships, while simultaneously raising the status of the merchant through identification with such practices. There is considerable scope for further research to be done on how these material communities formed and operated; what social worlds were involved in the creation of early modern matter. However, this article offers an insight into how a ‘body-centred approach’ illuminates previously unconsidered modes of network-building and shaped the production of objects,Footnote 118 while contributing to the emergent scholarly discussion about the position of the art-lover within European culture.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of The Historical Journal for their instructive comments and support. I am particularly grateful to Ulinka Rublack and Frederick Crofts, for their endless support of me and of this research, and for willingly reading many drafts. Many thanks also go to those who have heard this research presented in various forms, for their engaged and helpful responses: those at the German History Society Annual Conference 2023, the DAAD Cambridge–Tübingen Religion and Society in the Early Modern World Workshop, Cabinet of Natural History Seminar (Cambridge), and those at Embodied Faith: Spirituality and Corporeality in Early Modern Christianity (Warwick). Lastly, I am grateful to those who have given up time to discuss these ideas with me, for their encouragement and insights: Jill Bepler, Michael Wenzel, Marika Keblusek, Elizabeth Harding, and Ulrike Gleixner. This research would not have been possible without the generous support of the Harding Distinguished Postgraduate Scholars Programme and the Herzog August Bibliothek’s Rolf und Ursula Schneider-Stiftung.