You can’t be … intellectualizin’ the Black experience. Like, we’re also human beings … it’s more so a human experience that’s just particular to Black individuals, you know, because of our Blackness.

Joe Cornell (he/him) is a young Black changemaker. Like other Black young people whose stories appear throughout this book, Joe Cornell shared his human experience as a young Black person fighting for racial justice. As a 17-year-old Black boy, he was actively committed to bettering the lives of Black people and challenging racial injustices. As one of few Black students in a predominantly white school, Joe Cornell’s changemaking focused on “improvin’ the experience of Black students and POC [people of color] students and students that belong to marginalized communities – within predominantly white institutions and private institutions in particular.” He actively participated on his school’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee and led a coalition that works to hold private school administrators accountable to their espoused racial justice policies. Joe Cornell is making real change in his school, making it more welcoming, safe, and equitable for Black students and other students of color.

Changemaking is personal and deeply meaningful for Black young people. Joe Cornell shared that his Black identity makes his changemaking around racial justice policies especially powerful, saying “as a Black individual, not only am I bringing, you know, the concept … but I’m also bringing a lived experience of things they … wouldn’t necessarily know about the Black experience for obvious reasons.” The obvious reasons? Non-Black individuals are not targeted by anti-Black racism in the United States. Joe Cornell, like many other young Black changemakers, realized that he is building on a historical legacy of Black people’s fight against racism and for liberation. He put it this way: “What sort of ties us together as Black people in general is that shared history, that of not only, you know, pain and suffering, but also the resilience and the accomplishments.” As a young person, Joe Cornell recognized that he is on a journey in identifying his power and developing his abilities as a changemaker. His experiences helped him to realize that “social justice” was “where my heart was,” and to solidify his identity as a changemaker. Another signature element of young Black changemaking is looking toward the future. Joe Cornell envisions a future where Black people are in more leadership roles in the country: “I feel like it’s gonna be the responsibility of … the next generation of Black organizers and, you know, adults that are … in this world, and they’re in this country and, you know, movin’ into these leadership positions.”

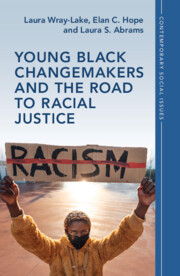

This book tells the stories of what it is like to be a young Black changemaker through the words and lived experiences of Black young people. If you conduct research related to, organize with, teach, parent, or care for Black youth in any capacity, this book is for you. We provide recommendations drawn from young Black changemakers’ own words and experiences in every chapter for educators, parents, practitioners, and scholars to better support young Black changemakers. We interviewed 43 Black young people, between the ages of 13–18 years, to learn how and why they engage in changemaking and to document their journeys to becoming changemakers. Some people already deeply understand young Black changemaking in its historical and contemporary forms, including scholars of the Black experience, civic leaders in Black communities, activists in Black-led social movements, and those who were and are young Black changemakers themselves. At the same time, many people do not understand or acknowledge young Black changemaking. Too often, people engage in negative stereotyping of Black youth, and Black youth are misunderstood, misrepresented, and mistreated. We wrote this book because we want more people to see and value Black youth for who they are and what they bring to society. Our purpose aligns with Joe Cornell’s quote that opened this chapter, as we aim to not intellectualize the Black experience, but to portray young Black changemakers’ humanity by sharing their stories in their own words.

And who are “we,” the authors? We are a multiracial and multigenerational group of scholars who came together with a shared passion for amplifying the voices of young Black changemakers. Our authorship team includes three more established scholars at the helm and eight students and new professionals, including doctoral students, master’s degree students, one undergraduate student, and a postdoctoral fellow and three doctoral students who became professors during this project. Six members of our team identify as Black, one as Latina, and four as white. Most of us are women, and we have one man among us. We share these details to clarify at the outset that we bring different perspectives and backgrounds to this book. To ensure that we interpreted Black youth’s experiences appropriately, we collaborated as a team every step of the way. We provide more detail about our methods in Appendix A, and in the final chapter, we each reflect on what we learned from our unique positions on the team.

The Backdrops for This Book

This study of young Black changemakers took place in Los Angeles, California between February and August 2020. What an important time and place that was for capturing Black youth’s experiences! The COVID-19 pandemic altered life as we knew it beginning in mid-March, 2020. We interviewed most of the youth during the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic at a time of unprecedented lockdown – when school was held virtually and face-to-face contact with people outside of one’s household was limited or non-existent. Despite these unusual circumstances, the COVID-19 pandemic was not a major theme in young Black changemakers’ stories. Our interviews had a broader focus on youth’s changemaking over time, and the study was conducted in the early months of COVID-19, when the longer-term nature and impacts were still unknown. We did not ask much about COVID-19, and some young people definitely mentioned it, but most did not discuss their pandemic-related experiences in detail. The same could not be said for the other major historical event that occurred during our study. The murder of George Floyd by police on the public streets of Minneapolis, Minnesota occurred on May 25, 2020, which ignited uprisings against racial injustice and police violence that continued and amplified the ongoing movement for Black lives. We added interview questions to give youth space to talk about this event, which had a major impact on their lives, as we detail in Chapter 8. These youth were living through major social and historical events and witnessing a large-scale movement in their own neighborhoods and on a national and global scale. Although the pandemic may not have played a central role in the interviews, the global movement against anti-Black racism certainly did.

With nearly 10 million residents and over 4,000 square miles, Los Angeles is the most populous county in the United States, and the major city within it is the second largest in the United States. While considered by many to be socially and politically progressive, Los Angeles also has a long history of anti-Black racism and was an epicenter of racial protest in summer 2020. The city has a history of stark residential segregation, mass incarceration, and racialized poverty (Hernández, Reference Hernández2017). The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) is notorious for racialized violence and a lack of accountability for use of force against Black and Brown residents (Felker-Kantor, Reference Felker-Kantor2018). The Watts Uprising in 1965 and the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising following the innocent verdict for officers who brutally beat Rodney King, an unarmed Black man, situate Los Angeles as a city with a history of protest against racism and police violence. In summer 2020, Los Angeles was home to large-scale protests around police brutality; the protests pointed to a groundswell of momentum for the Black Lives Matter Movement. The 2020 protests sparked more police violence against protesters, and according to the New York Times, a Los Angeles City Council commissioned report concluded that the LAPD had “severely mishandled protests, illegally detaining protesters, issuing conflicting orders to its rank-and-file officers and striking people who had committed no crimes with rubber bullets, bean bags and batons” (Bogel-Burroughs et al., Reference Bogel-Burroughs, Eligon and Wright2021, par 1). Even after this widely supported protest movement and widespread calls to defund the police, in 2021 the LAPD shot 38 people, killing 18 of them (J. Ray, Reference Ray2021). Individuals shot by police in Los Angeles are disproportionately Black and Hispanic or Latino/a/x/e. Bunn (Reference Bunn2022) analyzed national fatal police shooting data collected by the Washington Post and found that Black people are twice as likely as white people to be shot and killed by a police officer.

Some progressive change was achieved in the wake of the summer 2020 protests. Los Angeles County includes 88 cities, and change was enacted through local elections, ballot measures, and direct advocacy to policymakers. Black youth were on the front lines of many of these change efforts. For example, in February 2021, the Los Angeles Unified School District’s Board of Directors voted to cut one-third of the school district’s police force, a $25 million funding cut, ban the use of pepper spray by officers in schools, and redirect funds to promote Black student achievement (Gomez, Reference Gomez2021). This achievement was the result of a yearlong campaign led by students, some of whom participated in our research study. Additionally, Culver City passed a resolution acknowledging a history of racism, police violence, and exclusion (City Council of the City Culver City, 2021). In Manhattan Beach, the deed to a beachfront property that was unjustly taken from its Black owners was returned to the family’s heiress, a model upheld as a form of meaningful reparations (Ross, Reference Ross2022). On November 3, 2020, Los Angeles County voters passed Measure J, allocating 10% of the county’s general fund to “address the disproportionate impact of racial injustice through community investments such as youth development, job training, small business development, supportive housing services and alternatives to incarceration” (County of Los Angeles, n.d. par 1). Thus, Los Angeles was an ideal place to learn from Black youth who were actively involved in changemaking.

As we mentioned, COVID-19 is not a major theme in this book. Still, the early days of the pandemic exposed our society’s pre-existing racial inequalities. Black and Latino/a/x/e communities were at higher risk of COVID-19 exposure and death from the disease (Reitsma et al., Reference Reitsma, Claypool, Vargo, Shete, McCorvie, Wheeler, Rocha, Myers, Muray, Bregman, Dominguez, Nguyen, Porse, Fritz, Jain, Watt, Salomon and Goldhaber-Fiebert2021). Lee (age 18, he/him), a young Black changemaker in our study, described the COVID-19 pandemic as an additional burden that Black people must face, remarking, “we already got a lot of stuff to be scared of and now we are scared of the ‘Rona too.” Police violence and COVID-19 became dual pandemics. As Dr. Janine Jones (Reference Jones2021, p. 427) stated, “The COVID-19 pandemic shined a magnifying glass on racially based structural inequities in a manner that was impossible to unsee or to look away.” Young Black changemakers in our study were actively addressing socioeconomic and racial inequalities – including homelessness, gentrification, everyday racism, and school and health inequities – in their Los Angeles neighborhoods well before the pandemic. They were and are leading our nation on the road to racial justice, through everyday acts of helping as well as through social movement participation and leadership.

These were the contexts in which we found the young Black changemakers; these are the backdrops for their changemaking journeys. In the next section, we provide background on what it means to be a “young Black changemaker.”

What It Means to Be a Young Black Changemaker

The concept of changemaking is known by many other names, and broadly falls under the umbrella of civic engagement. So, what is civic engagement? This term has not completely taken hold in the public vernacular, and academics have put forward various definitions. Put most simply, the American Psychological Association (2009, par 2) defines civic engagement as “individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern.” This definition emphasizes civic actions, but civic engagement more broadly includes values, attitudes, knowledge, and skills (Wray-Lake et al., Reference Wray-Lake, Metzger and Syvertsen2017). Public conversation about civic engagement tends to focus on specific forms of civic action, such as voting, protesting, political campaigning, volunteering, or community service. There is not “one way” to be civically active – individuals engage in many different forms of civic actions. What we consider actions to address issues of public concern, or as others have put it, actions that contribute to community or society (Wray-Lake et al., Reference Wray-Lake, Metzger and Syvertsen2017), can vary depending on an individual or community’s culture, norms, and values and the larger political context of a region or country (Wray-Lake et al., Reference Wray-Lake, Gneiwosz, Benavides, Wilf, Kostic and Chadee2021). This book shares what civic engagement looks like for Black youth in Los Angeles. In the chapters to follow, Black youth tell us how they are civically engaged and why. Their perspectives and experiences are shaped by their contexts, and their civic actions may look similar to or different from civic actions of youth in other communities and contexts.

So, this book is about Black youth’s civic actions, but that is not all. Changemaking is not simply synonymous with civic actions. We use the term “changemaking” to capture civic actions that are connected to a higher purpose. Individuals can engage in civic actions for a host of different reasons (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Malin, Porter, Colby and Damon2015), and civic actions are not always aligned with a larger vision or goal for better communities or a better future. For Black youth in our study, civic actions are purposeful and intentionally aimed at positive change for their community and for Black people in the United States. These Black youth are changemakers, taking part in and leading many efforts to ensure that the world is a better place in general, and for Black people in particular. These youth are envisioning a future without racism and without economic inequalities, and they are working now to make real changes toward this future. To use a phrase coined by Dr. Robin D. G. Kelley (Reference Kelley2002), these Black youth are “freedom dreaming,” meaning that they are imagining a future that guides their struggle and their quest for justice. Black people have long had to struggle against racial oppression, and Black youth’s civic actions are a response to that struggle. Black youth also have big dreams for a better future – a future where there is equality and freedom from suffering. We share the stories of young changemakers, so that they can help us all imagine a better future. As Kelley (Reference Kelley2002, p. 10) wrote in Freedom Dreams:

In the poetics of struggle and lived experience, in the utterances of ordinary folk, in the cultural products of social movements, in the reflections of activists, we discover the many different cognitive maps of the future, of the world not yet born.

In our book, young Black changemakers poetically share their struggles and lived experiences as well as their reflections and visions for the future. It is important for the world to listen to young Black changemakers – to hear and reflect on their journey, experiences, and struggles – and let them inspire us to work toward a world where everyone is free from oppression. In this book, we will say much more about young Black changemaking, positioning Black youth as experts on their own experiences who are agents of change in their communities and society.

We have good reasons for focusing on young Black changemakers, meaning those who are in their adolescent years. Adolescence is considered a unique age period where young people experience many different developmental changes simultaneously (although this period may look different across different contexts and cultures). Adolescents experience dramatic physical growth during puberty and beyond, which coincides with rapid brain development, sexual development, and social and identity development (Crockett et al., Reference Crockett, Carlo and Schulenberg2023). Adolescence is a time when youth are actively figuring out who they are, who they want to be, and what they stand for, at the same time as they are developing the cognitive abilities to understand society’s problems on a deeper level (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2013). They often bring energy, passion, and new ideas to address social issues. Sociologist Karl Mannheim (Reference Mannheim and Mannheim1952) called youth’s interface with society and culture “fresh contact” and argued that young people’s fresh, new perspectives on long-standing societal issues are essential for making social change. We agree. Because young people are less entrenched in “the way things are” in society, young people can better envision new futures that break old cycles.

Black youth may be among the most active freedom dreamers. Black young people, and young people in general, continually reimagine what it looks like to be civically engaged. For today’s youth, social media is part of the civic commons, or public spaces in which they gather and act to challenge oppressions and create change (Wilf & Wray-Lake, Reference Wilf and Wray-Lake2021). Young people are creatively reimagining how to engage in online civic actions so rapidly that research struggles to keep pace. Young people find new and creative ways to act civically across many different settings, and some youth act civically amid substantial barriers to civic participation. Adolescents are legally excluded from some types of civic action such as voting and are often systematically excluded from many other spaces where decisions are made including political parties, local councils, and school boards. Young changemakers are determining ways they can make change in the contexts they are in and with the resources they have. When looking at the experiences of young Black changemakers, it is especially important to broaden our perspectives beyond traditional ideas of civic engagement, because Black youth may turn to creative strategies for civic action, informal modes of participation, and other ways of building individual and collective power to resist systemic racism (Watts & Flanagan, Reference Watts and Flanagan2007).

Young Black Changemaking in the Context of Racism

In the United States, Black changemaking takes place in the context of systemic anti-Black racism. Given the realities of anti-Black racism, Black youth’s changemaking is often aimed at eradicating racial oppression. Joe Cornell’s work to stop racism and strive toward racial equity in his predominantly white school exemplifies young Black changemaking and illustrates how Black youth resist racism and freedom dream for a better future without racial oppression.

Systemic racism refers to “forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in and throughout systems, laws, written or unwritten policies, entrenched practices, and established beliefs and attitudes that produce, condone, and perpetuate widespread unfair treatment of people of color” (Braveman et al., Reference Braveman, Arkin, Proctor, Kauh and Holm2022, p. 171). Anti-Black racism is systemic racism that is directed specifically toward Black people. Anti-Black racism is a form of oppression: Oppression includes prejudices and institutional power that create systems that benefit dominant groups and discriminate against others – whether by race, gender, social class, immigration, language, sexuality, or other factors (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Fernández, Gordon, Masud, Hilson, Tang, Thomas, Clark, Guzman, Bernal, Jason, Glantsman, O’Brien and Ramian2019). Oppressions co-exist in different ways for different people. Scholars call this intersectionality, a term coined by Black legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1991) to describe inequalities faced by Black women due to sexism and racism and embodied in the work of The Combahee River Collective (1977), an organization that advocated for Black queer women whose rights were not fully represented by the civil rights or women’s movements.

In understanding Black young people’s experiences of anti-Black racism, it is important to recognize that anti-Black racism occurs at interpersonal, cultural, and institutional levels (Jones, Reference Jones1997). Interpersonal racism is the most studied and understood form of racism, consisting of direct interactions with people who enact bigotry, prejudice, microaggressions, and other unfair treatment. Research conducted by Dr. Anna Ortega-Williams and colleagues (Reference Ortega-Williams, Booth, Fussell-Ware, Lawrence, Pearl, Chapman, Allen, Reid-Moore and Overby2022) pinpointed everyday spaces such as schools, buses, and streets where Black youth experience interpersonal anti-Black racism. Dr. Devin English and colleagues (Reference English, Lambert, Tynes, Bowleg, Zea and Howard2020) asked Black youth about their daily lives for two weeks and found that they experience racism online and in person on an average of five times every day.

Racism is also embedded in our institutions and culture. Institutional anti-Black racism consists of policies and practices within institutions such as schools, the justice system, or health care that systematically disadvantage Black people. Cultural racism is the predominance of a majority racial group over other racial groups. Cultural anti-Black racism includes the negative stereotypes about Black youth that pervade media and everyday narratives. Dr. Elan Hope and colleagues (Reference Hope, Brinkman, Hoggard, Stokes, Hatton, Volpe and Elliot2021) found that 72% of Black adolescents experienced institutional racism and 93% experienced cultural racism in their lifetime. The harms of racism for Black youth are indisputable: Many studies have documented the tolls racism takes on Black youth’s physical and mental health (Trent et al., Reference Trent, Dooley, Dougé, Cavanaugh, Lacroix, Fanburg, Rahmandar, Hornberger, Schneider, Yen, Chilton, Green, Dilley, Gutierrez, Duffee, Keane and Wallace2019; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Lawrence and Davis2019).

For as long as racism has existed, there has also been active resistance to this oppression. From the rebellions of enslaved Africans in the Americas to the Civil Rights Movement to the Black Lives Matter Movement and so much in between, Black resistance against racism through civic action has a long, rich history (Frey, Reference Frey2020; Taylor, Reference Taylor2016; Webster, Reference Webster2021). Resistance is a response to systems of oppression that are marginalizing and harmful and can be broadly defined as actions undertaken to undermine power and domination (Johansson & Vinthagen, Reference Johansson and Vinthagen2020). Resistance may be more or less explicitly aimed at restructuring power in ways that reduce oppressions, but it is almost always about reclaiming humanity and exercising control in the face of discrimination, disregard, mistreatment, or dehumanization (Tuck & Yang, Reference Tuck and Yang2014; Wray-Lake et al., Reference Wray-Lake, Halgunseth and Witherspoon2022). For example, during the period of chattel slavery in America, enslaved Africans engaged in collective rebellion to fight for freedom, and through everyday actions, resisted systems of oppression in many ways such as slowing down work, feigning illness, and sabotaging equipment or goods (Frey, Reference Frey2020).

Although protesting may be the most visible and recognizable way of challenging racism, today’s Black youth engage in many different forms of resistance. For example, some Black youth challenge anti-Black stereotypes by achieving excellence and giving back to their communities (Carter, Reference Carter2008). Black changemaking is often a response to oppression, but Black civic life is about much more than a struggle against racism; it is also rooted in rich cultural strengths, traditions, and Afrocentric values such as helping and uplifting family and community (Boykin, Reference Boykin and Neisser1986). Black civic life also encompasses spirituality and joy.

In the stories within this book, being an adolescent, being Black, and being highly civically engaged are merged in youth’s lived experiences. Black youth are navigating multiple layers of racism and experiences with other marginalizing systems as they engage in changemaking. This book tells the stories of how Black youth are navigating these contexts and doing this work, where anti-Black racism is a backdrop and Black culture and community are sources of support. No single story can encapsulate young Black changemaking, as Black youth have very different backgrounds, experiences, and journeys into changemaking. Yet, at the same time, some consistent influences show up in their stories, such as experiencing racism and drawing strength from identity, family, and community organizations.

Sociopolitical Development Theory

To situate Black youth’s civic engagement in prior research, we turn to sociopolitical development theory, which is a model to understand how Black youth become changemakers. Developed by Black community psychologist Dr. Roderick Watts, sociopolitical development is “a process of growth in a person’s knowledge, analytic skills, emotional faculties, and capacity for action in political and social systems” (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Williams and Jagers2003, p. 185). Watts developed this model from community-based programming with Black boys and young men, and also drew from the work of other Black scholars and activists as well as Paulo Freire’s (Reference Freire1970) closely related concept of critical consciousness (Watts & Halkovic, Reference Watts and Halkovic2022).Footnote 1

Civic action, critical reflection, and agency are three main components of sociopolitical development. Sociopolitical development encompasses many civic actions, and what binds them together is an emphasis on challenging oppression. The way we define changemaking – as actions with a higher purpose for creating social change – aligns with sociopolitical development theory and helps clarify the civic actions most relevant to the pursuit of racial justice for Black youth. Critical reflection and agency are essential ingredients of sociopolitical development that inform and are informed by civic action. Critical reflection is defined as awareness and analysis of inequities in society, such as racism and other systems of oppression. For example, when Joe Cornell conveyed his understanding of how racism is perpetuated in predominantly white institutions, his deep awareness and critical thinking illustrated critical reflection about inequities. Civic agency, which we simply call agency, involves perceived capacity and motivation to challenge oppression and create positive change in communities and society. When Joe Cornell described a “power moment” in recognizing his capacity to have his views reflected in school policy, this was an excellent example of a young person naming their agency. Sociopolitical development theory originally posited that critical reflection and agency lead to action, and studies have found evidence for this idea among Black youth (Hope, Smith et al., Reference Smith and Hope2020) and youth more broadly (e.g., Bañales, Mathews et al., Reference Bañales, Hoffman, Rivas-Drake and Jagers2020; Diemer & Rapa, Reference Diemer and Rapa2016; Plummer et al., Reference Plummer, Wray-Lake, Alvis, Metzger and Syvertsen2022). However, this process is not a one-way street; civic action can also inform agency and reflection (Heberle et al., Reference Heberle, Rapa and Farago2020). Throughout the book, we illustrate how Black youth are developing agency and critically reflecting on injustices as they engage in changemaking.

Sociopolitical development theory and evidence points to four main influences on Black youth’s civic actions, critical reflection, and agency to challenge oppressive systems. These four influences are: experiences of racism, social identity, early influences, and opportunity structures (Anyiwo et al., Reference Anyiwo, Bañales, Rowley, Watkins and Richards-Schuster2018; Watts & Halkovic, Reference Watts and Halkovic2022), and we introduce them briefly here because they are central topics in the stories to come of young Black changemakers.

First, Black youth who experience interpersonal, cultural, or institutional racism may use civic action to actively cope with the trauma of racism and feel compelled to change the unjust conditions that harm them and others. In a review of 26 studies, Dr. Elan Hope and colleagues (Reference Hope, Mathews, Briggs, Alexander, Godfrey and Rapa2023) documented considerable evidence that experiencing racism at any level (whether it be institutional, cultural, or interpersonal) is related to more civic action to challenge these injustices among Black youth and other youth of color.

Second, Black youth’s racial identity – or how being Black matters to who they are as a person – is increasingly recognized as central to changemaking (Anyiwo et al., Reference Anyiwo, Bañales, Rowley, Watkins and Richards-Schuster2018; Mathews et al., Reference Mathews, Durkee and Hope2022; Watts & Halkovic, Reference Watts and Halkovic2022). Dr. Channing Mathews and colleagues (Reference Mathews, Medina, Bañales, Pinetta, Marchand, Agi, Miller, Hoffman, Diemer and Rivas-Drake2020) laid out processes by which youth’s exploration of racial and ethnic identity overlaps with their development of critical reflection and action. Yet, much more remains to be learned about racial identity and changemaking, including the role of collective identity (feelings of solidarity and belonging to a social identity group; Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, Reference Watts and Hipolito-Delgado2015) and intersectional identities (Godfrey & Burson, Reference Godfrey and Burson2018; Santos, Reference Santos2020).

Third, early life experiences, including family upbringing and other influential relationships and cultural experiences, shape Black youth’s change-making. Research shows how Black families’ conversations about race and racism inform Black youth’s civic engagement (Bañales, Hope et al., Reference Bañales, Aldana, Richards-Schuster, Flanagan, Diemer and Rowley2021; Christophe et al., Reference Christophe, Martin Romero, Hope and Stein2022), and that Black music, Black joy and community, and Black history shape Black youth’s sociopolitical development (Anyiwo et al., Reference Anyiwo, Watkins and Rowley2022; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Marchand, Moore, Greene and Colby2021). Early influences on changemaking that go beyond family influences have not been comprehensively examined for Black youth.

Fourth, opportunity structures – including schools, organizations, and programs – provide access and opportunity for Black youth to develop critical reflection, agency, and civic action (Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, Reference Watts and Hipolito-Delgado2015). Research has emphasized how community-based organizations, such as community organizing groups, support sociopolitical development (Fernández & Watts, Reference Fernández and Watts2022; Ginwright, Reference Ginwright2010a; Terriquez, Reference Terriquez2015). Research has also shown that school curricular and extracurricular activities that spark critical reflection and prioritize youth voice and agency offer valuable opportunities for youth to grow as changemakers (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Littenberg-Tobias, Ridley-Kerr, Pope, Stolte and Wong2018; Hipolito-Delgado et al., Reference Hipolito-Delgado, Stickney, Zion and Kirshner2022; Seider & Graves, Reference Seider and Graves2020).

Sociopolitical development theory and related research have yielded valuable insights about Black youth’s experiences of changemaking that inform and help to structure the work presented in this book. Our work builds on this theoretical tradition, and we point out ways that our work supports and extends this theory throughout the book.

The Main Ideas Found in This Book

In the next eight chapters, we bring to life the stories of 43 young Black changemakers living in Los Angeles, California in 2020, in the context of major social upheaval and the possibility for change. Youth chose their own pseudonyms for the book, and we report their age and preferred pronouns when we quote them. To help readers get to know these young people further, we provide a profile of each young person in Appendix C. We also invited Black youth in our study and in organizations around Los Angeles to submit art to be featured in the book. We selected five outstanding pieces from two young Black artists – Zoie Brogdon and Meazi Light-Orr. Four drawings and a poem are interspersed between the chapters. Featuring this art was another way for us to uplift Black youth’s voices and showcase their talents.

As a preview of what is to come, we share 10 main ideas that emerged from these youth’s stories. These ideas cut across the book chapters and form the core of this book’s contributions to theory, research, applied work with Black youth, and public discourse about Black youth.

(1) Young Black changemakers are fighting for racial justice in different ways. Black youth engage in many different civic actions and envision different types of change (Chapter 2). They passionately and purposefully pursue racial justice through civic action for their own safety and survival (Chapter 3), for their families (Chapter 6), and for other Black people (Chapter 8).

(2) Young Black changemakers are future-oriented. Black youth are taking actions now (Chapter 2) and envisioning bold changes (Chapter 9) to create a better world for their own family members and future generations of Black people. This future orientation toward racial justice embodies Black youth’s freedom dreaming and continues a legacy of changemaking from their families, communities, and Black resistance that goes back generations (Chapter 4).

(3) Experiencing anti-Black racism is a catalyst for changemaking. Black youth face interpersonal and institutional racism in non-Black school spaces (Chapter 3) and contend with many forms of racism in everyday life, including cultural racism (Chapter 4) and police violence (Chapter 8). Even while facing the harms and substantial emotional burdens of anti-Blackness, young Black changemakers resist multiple forms of racism through civic action.

(4) Black racial identity motivates Black youth’s changemaking and offers tools to cope with and resist racism through changemaking. Understanding oneself as a Black young person, and the history of being Black in the United States, is informed by changemaking and shapes future changemaking (Chapters 4 & 8). Black youth’s personal and collective identities, as well as intersecting identities related to gender and social class, shape changemaking (Chapter 4).

(5) Black families encourage changemaking in multiple ways. Black youth’s families, and especially mothers, connect youth to changemaking opportunities and communicate values that support changemaking, and Black youth seek to honor and protect their families through their changemaking (Chapter 6).

(6) Black community spaces are safe havens for Black youth and incubators for their changemaking. Black spaces in schools offer safety from racism (Chapter 3). Black civic organizations offer critical education about Black history (Chapter 7). Black youth need community support, given that changemaking to resist anti-Black racism comes with substantial emotional burdens (Chapter 3). Black community members inspire Black youth to launch into changemaking (Chapter 5). Black communities offer spaces where Black youth can feel like they belong, experience joy and pride, and build solidarity for collective action (Chapters 3, 4, 5, 8).

(7) Access to civic opportunities enables Black youth to begin and sustain their changemaking. Black youth benefit from family members and other adults who connect them to opportunities and encourage them to participate (Chapters 5 & 6). Fun experiences and community building opportunities also draw Black youth to civic actions (Chapter 5). Community-based organizations offer opportunities for Black youth to see impact from their civic actions, take ownership of their civic work, gain critical knowledge, feel encouraged by adults, and be in community with other Black people. These experiences build agency, increasing youth’s skills and power to sustain their changemaking over time (Chapter 7).

(8) Black youth exert agency to forge their own paths toward impactful changemaking. Agency is a launching point for young Black changemaking, as Black youth seek ways to pursue their passion for racial justice (Chapter 5). Black youth show agency to help and protect their families through changemaking (Chapter 6). Youth develop agency over time through civic opportunities and support from others (Chapter 7), which is further activated by racial justice movements (Chapter 8).

(9) The racial justice movement of summer 2020 activated young Black changemakers. Summer 2020 was a pivotal moment when Black youth recognized their role in the larger social movement, drew from past legacies of Black changemaking, and deepened their agency, reflection, and action, all while continuing to grapple with systemic racism and its emotional toll (Chapter 8).

(10) Young Black changemakers give us hope for a better world, and we must follow their lead. We hope this book offers a sense of hope from the ways that Black youth are working to create change locally and nationally. In Chapter 9, we look to the future, sharing how these young Black changemakers describe the better world they envision. Youth’s messages are calls to action for those committed to working with and supporting Black youth in their quests for justice.

Up Next

In Chapter 2, we document the range of civic actions that Black youth take and the purpose they are aiming for through these actions. This alignment between young people’s civic actions and purpose is the epitome of changemaking. Our emphasis on changemaking recognizes that why young people are engaging in civic actions is as important or more important than the specific actions they take. We present a contemporary portrait of today’s young Black changemakers. As young people continually update their ways of being civically engaged, including using social media alongside in-person actions for change, and respond to momentous times in history like the racial reckoning of summer 2020, it is important, as Joe Cornell expressed, to keep knowledge of young Black changemaking current and centered on human experiences.

Untitled by Meazi Light-Orr