The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is the primary multilateral institution for coordinating joint responses to armed conflict. In order for the UNSC to play this function, conflicts must be placed on its formal agenda, allowing member states to deliberate and discuss what, if anything, should be done. The historical record demonstrates that this agenda-setting process is highly selective. For example, whereas conflicts in Sudan appeared on the UNSC's agenda no less than 244 times between 1989 and 2019, the civil war in Sri Lanka, equally long and equally deadly, was not discussed once. Similarly, the civil wars in Syria and Bosnia-Herzegovina have been discussed at dozens of meetings, but long-standing conflicts in the Philippines, India and Niger have not been the subject of a single meeting. More generally, of the 84 countries that experienced armed conflict between 1989 and 2019, only 43 appeared in formal UNSC deliberations. Why do some conflicts receive the UNSC's attention whereas others do not?

Understanding the factors that shape the UNSC's agenda is important for two key reasons. First, agenda setting is a necessary condition for action: unless an issue is placed on the agenda, the UNSC will not be able to discuss and formulate a coordinated response. Secondly, whether the UNSC privileges the interests of its most powerful members or responds to the collective interests of the wider membership has implications for the United Nations’ (UN's) organizational legitimacy.

Recognizing the importance of UNSC agenda setting, scholars have sought to identify its determinants. The aggregated evidence is inconclusive. Quantitative studies have found that the UNSC is responsive to collective concerns, such as civilian victimization, but other studies emphasize how the UNSC is shaped by great-power politics. While there are many reasons for why findings diverge, including methodological limitations, a central barrier has been the tendency to theorize and model the UNSC's five permanent members (the P5) as a collective, rather than as individual actors with diverging interests. To the extent that scholarship has considered individual actors, it has tended to focus on the United States, neglecting the other four members.

In this article, we seek to move beyond these limitations. Theoretically, we develop an argument centred on the role of conflict externalities, P5 interests and interest heterogeneity. In contrast to existing quantitative scholarship, we emphasize the role of individual P5 interests, which better reflects their divergent perspectives on global governance. We also depart from the convention of viewing interest heterogeneity from a transaction-cost perspective and develop an argument focused on agenda entrepreneurship. In addition, where previous studies have viewed UNSC dynamics as static, we investigate whether agenda-setting patterns correlate with over-time evolution of international norms.

Empirically, we evaluate our argument against data on the UNSC's agenda during 1989–2019. We make three main findings. First, the UNSC's attention is sensitive to conflict severity. All else equal, conflicts that generate substantial military or civilian deaths are more likely to attract the UNSC's attention. We go beyond existing findings by showing that the sensitivity to conflict severity has increased following the 2005 adoption of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P), which provides improved evidence that the UNSC is partly responsive to the public goods mandate stipulated by the UN Charter.

Secondly, the UNSC's agenda is shaped by the interests of the permanent members, though in different ways. While the UNSC's liberal democracies (the P3) are less likely to involve the UNSC when their core interests are at stake, Russia and China are more likely to seek to place such issues on the agenda. This finding, while seemingly contrasting with standard beliefs regarding the interventionist orientation of the P3, can be explained with the latter group's more expansive outside options and the greater interest alignment between China and much of the developing world, where most conflicts take place.

Thirdly, in contrast to much existing literature, we find that conflicts over which UNSC members have divergent interests are more likely to enter the agenda. This indicates that anticipation of difficulties of reaching agreement does not discourage UNSC members from deliberation and debate. Our interpretation is that diverse preferences, when combined with the UNSC's low procedural hurdles for agenda setting, facilitate agenda entrepreneurship: when interests are more diverse, it is more likely that at least one actor has interests strong enough to outweigh the political costs of placing an item on the agenda.

These findings have important implications for the literature, which are further developed in the conclusion. To begin with, they suggest that debating whether individual or collective interests are the primary movers of the UNSC's agenda – the prevailing concern in the literature – is futile. The evidence demonstrates the UNSC's sensitivity to both. Next, our study illustrates the promise of moving away from modelling the P5 as a collective and instead towards developing and refining theory and measures that capture their separate interests. The permanent members appear to be using the UNSC in different ways and for different purposes. Finally, our findings regarding interest diversity suggest that the UNSC's position as a primary venue for great-power deliberation and posturing will remain robust, even in an international context defined by accentuating political frictions.

State of the Art

The UNSC has attracted considerable scholarly attention. In recent decades, literatures have developed around both UNSC decision-making (Voeten Reference Voeten2001; Voeten Reference Voeten2005; von Einsiedel, Malone and Ugarte Reference Von Einsiedel, Malone and Ugarte2015; Vreeland and Dreher Reference Vreeland and Dreher2014) and UNSC interventions, such as peacekeeping (see, for example, Di Salvatore et al. Reference Di Salvatore2022; Fortna Reference Fortna2008; Howard Reference Howard2008), economic sanctions (see, for example, Chesterman and Pouligny Reference Chesterman and Pouligny2003) and mediation (Hansen, McLaughlin Mitchell and Nemeth Reference Hansen, McLaughlin Mitchell and Nemeth2008; Tir and Karreth Reference Tir and Karreth2018). These literatures provide important insights into the internal dynamics of the UNSC, its ability to agree on policy and its external effects on the trajectories of the issues, conflicts and crises with which it decides to engage.

Another literature emphasizes the antecedent stage of agenda setting, that is, how issues, conflicts and crises attract the UNSC's attention. This literature has generated four main reasons for why agenda setting deserves consideration, often resonating with research on domestic agenda setting (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010). First, the agenda is informative about what issues hold the UNSC's attention. Whether the UNSC includes an issue on its agenda sends a signal about its current and future political priorities (Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020). Secondly, agenda setting is a prerequisite for action. While deliberation certainly does not guarantee an effective UNSC response, it is a necessary condition for arriving at a policy decision (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995). Thirdly, what the UNSC decides to take up for deliberation, as well as leave out, has implications for perceptions about legitimacy. Insufficient or biased attention is a recurring concern in policy debates, and agenda setting is the first step in the UNSC's legitimizing function in international politics (Coleman Reference Coleman2007; Hurd Reference Hurd2008). Finally, largely flowing from the aforementioned reasons, agenda setting is frequently viewed as an exercise of power (Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962). Actors with influence over what gets attention – and what does not – by a political body have ‘gatekeeping power’ (Crombez, Groseclose and Krehbiel Reference Crombez, Groseclose and Krehbiel2006) or ‘agenda power’ (Shepsle and Weingast Reference Shepsle and Weingast1984; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2003). For these reasons, UNSC members exert considerable effort to place issues on the agenda, frequently viewing it as ‘a success in itself’ (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2013).

In research on UNSC agenda setting, two broad perspectives have emerged, representing contrasting assumptions about the UNSC's role and purpose in international politics. According to the ‘governance perspective’, the UNSC is the steward of an organizational mission to promote peace and prevent humanitarian suffering, if necessary, via corrective interventions (Beardsley and Schmidt Reference Beardsley and Schmidt2012; Bosco Reference Bosco2009). In contrast, the ‘concert perspective’ views the UNSC as a mechanism to safeguard the interests of the P5 and escape great-power war (Bosco Reference Bosco2009). Other researchers have expressed this distinction in different terms (Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020; Cockayne, Mikulaschek and Perry Reference Cockayne, Mikulaschek and Perry2010), while agreeing that the fundamental debate pertains to whether the UNSC's agenda reflects a concern for broad, public interests or is primarily driven by great-power politics.

The observable implications flowing from these two perspectives have been subject to empirical evaluation in both quantitative and qualitative studies. Cockayne, Mikulaschek and Perry (Reference Cockayne, Mikulaschek and Perry2010) find that the UNSC's attention has varied across time, geography and conflict characteristics, but they could not determine whether public or parochial interests dominated. Examining 40 armed conflicts between 2002 and 2013, Frederking and Patane (Reference Frederking and Patane2017) find that conflicts generating more deaths and refugees are more likely to receive the UNSC's attention, while indicators of P5 interests matter less. Also favouring the governance perspective, a study of civil wars between 1990 and 2009 by Benson and Gizelis (Reference Benson and Gizelis2020) finds that the UNSC agenda is responsive to sexual violence. In contrast, Allen and Yuen (Reference Allen and Yuen2020, Reference Allen and Yuen2022) identify P5 interests as a key determinant of the UNSC's meeting agenda, while Binder and Golub (Reference Binder and Golub2020) find that the UNSC primarily reacts to conflict severity but that P5 interests have some predictive power.

Qualitative studies have been more conclusively supportive of the concert perspective. Boulden (Reference Boulden2006: 409) concludes that agenda setting is largely driven by P5 interests: it is the ‘P-5 who control both what gets on the Security Council agenda and, importantly, what does not’. Voeten (Reference Voeten2005) points to peacekeeping-financing arrears as an example of how the P5 act in a manner inconsistent with a perspective focused on public goods provision. Rather, Voeten submits, the UNSC is best understood as an ‘elite pact’, where decisions – and, implicitly, agenda setting – reflect the members’ interest in burden-sharing and legitimization.

The accumulated evidence is inconclusive. The quantitative evidence has been largely supportive of the governance perspective, while failing to generate firm conclusions regarding the concert perspective, which is favoured by qualitative studies. There are many explanations for this inability to firmly establish a set of correlations, including disparities in sampling, divergent definitions of what constitutes a conflict, panel data with short time frames and different modelling techniques. A primary reason for the divergent findings, however, is the tendency in quantitative studies to model and measure the P5 as a collective (see, for example, Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2020; Benson and Gizelis Reference Benson and Gizelis2020; Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020; Frederking and Patane Reference Frederking and Patane2017).Footnote 1 In light of historical evidence that emphasizes P5 tensions as a defining characteristic of the UNSC (see, for example, Malone and Malone Reference Malone and Malone2004; von Einsiedel, Malone and Ugarte Reference Von Einsiedel, Malone and Ugarte2015) and new data sources allowing for fine-grained disaggregation, modelling P5 preferences as collective averages appears unwarranted and unnecessary. Homogenizing the P5 obscures central dimensions of variation that can help us understand UNSC dynamics and in what specific ways P5 interests balance against the UN's organizational mission. To evaluate if and how the interests of the P5 affect the UNSC's agenda, we need to disaggregate the P5 and include measures of their individual preferences and relationships.

Another barrier has been the reliance on transaction-cost logics in theorizing about the impact of preference diversity. While we find the standard argument – more diverse preferences make decisions more difficult – plausible, the historical record suggests that the P5 has met to deliberate and debate even when their viewpoints have been conflictual. This suggests that we may need to pay greater attention to explanations pertaining to agenda entrepreneurship and the role of multilateral venues in the handling of disagreements.

Furthermore, most existing studies overlook temporal variation, either by design or because they are based on short time series unsuitable for identifying temporal shifts. As longer time series become available relating to both conflicts and the activities of the UNSC, there emerge opportunities to assess whether the patterns discussed in the literature, such as increasing tensions between the Western powers and both Russia and China, or the emergence of such norms as the ‘Responsibility to Protect’, affect agenda setting in the UNSC.

Theory

In studies of political attention, agenda setting is conventionally viewed as a pre-decision stage characterized by prioritization. In Kingdon's (Reference Kingdon1995, 3) definition, ‘the agenda-setting process narrows down [a] set of conceivable subjects to the set that actually becomes the focus of attention’. Consequently, the agenda can be understood as the ‘the list of subjects or problems to which [a political body is] paying some serious attention at any given time’ (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1995: 3). The view of agenda setting as an exercise in prioritization reflects the fundamental insight that attention is a scarce resource, requiring political bodies to economize its allocation across issues (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010).

At the UNSC, this agenda-setting process is shaped by both formal rules and political considerations. The relevant legal framework is laid down in the UN Charter and the Provisional Rules of Procedure. Pursuant to Article 35 of the Charter, any UN member may bring any dispute or situation to the attention of the UNSC. For example, when Russia committed its invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Ukraine submitted a letter to the UNSC invoking Articles 34 and 35, triggering a debate and vote on Russia's conduct (UNSC Meeting S/PV.8979). Article 27 of the Charter provides the rules for adopting decisions on both procedural and substantive matters. Decisions on the content of the agenda tend to be considered as a procedural matter, which is relevant because Article 27(2) imposes a more lenient threshold for procedural matters, requiring only an affirmative vote of nine members. In contrast, Article 27(3) provides that decisions on all other matters shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members, including the concurring votes of permanent members (that is, the veto power). Earlier, agenda setting was governed by the so-called double veto, whereby a permanent member could first use its veto to make the matter substantive and thus prevent it from entering the agenda. Due to an informal agreement between the P5, the double veto has not been used since 1959 (Bailey and Daws Reference Bailey and Daws1998).

According to the procedural rules, the provisional agenda is prepared by the secretary-general and approved by the UNSC president. Only items that have been brought to the attention of UNSC representatives, items from previous meetings or deferred matters may be included in the provisional agenda (Rule 7). All items on the agenda are contained in the summary statement of matters of which the UNSC is seized, and items remain on that list until they have been dealt with or removed.

These rules provide the procedural, formal context of the UNSC's response to international issues, but they stipulate no substantive guidance, nor do they set limits on the number of issues the UNSC can deal with. It is therefore up to the UNSC to decide what it wants to take up for deliberation.

In seeking to understand which factors shape the allocation of attention in the UNSC, we develop a theoretical argument that highlights three categories of explanations: conflict severity and externalities; member interests; and interest diversity. Under each of the three categories, we discuss specific factors that shape actors' weighing of the net benefits that accrue from multilateral consideration in the UNSC against those expected from non-consideration or from consideration in alternative forums. While our argument develops broad propositions that allows us to test relationships at the heart of current debates, it also identifies novel propositions relating to three features: the role of individual state interests; agenda entrepreneurship as a function of preference heterogeneity; and temporal shifts in the normative context.

Conflict Severity and Externalities

As set out in the Charter, the purpose of the UN is to prevent war and promote the pacific settlement of disputes. This organizational mission is formulated with little substantive qualification. As Bosco (Reference Bosco2014: 546) explains: ‘[t]he Charter makes no geographic or qualitative distinction between potential disruptions to the peace and makes clear that the Council can investigate any dispute it deems dangerous to peace and security’. If the UNSC is responsive to its mandate of preventing armed violence, it should direct its attention to conflicts that are severe, prioritizing those that generate significant deaths, security risks and humanitarian suffering.

This proposition is underpinned by both normative and practical logics. The normative logic largely corresponds to the ‘governance model’ discussed in the literature. It assumes that actors can serve as agenda entrepreneurs, highlighting situations that fall within the confines of the UNSC's Charter responsibilities and raising expectations that it will devote attention to them. For example, the United States and Germany were leading agents in getting the UNSC to deliberate and act on the conflict in Darfur (Power Reference Power2019). Next to member states, the secretary-general can also bring matters to the UNSC's attention, a prerogative laid down in Article 99 of the UN Charter. For example, during the 1960 Congo crisis, Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold played an instrumental role in keeping the issue on the UNSC's agenda and the discussion focused on the UN's core mission.

Besides generating normative pressures to act, severe conflicts are also likely to be a concern for the UNSC for self-interested, practical reasons. Severe conflicts are more likely to be destabilizing, spread beyond their origins and threaten international commerce (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003) and long-term development (Collier Reference Collier2003). They are also likely to trigger dislocation and external refugee streams, which can lead to political unrest and increased interstate tensions, sometimes precipitating armed interventions (Salehyan and Gleditsch Reference Salehyan and Gleditsch2006). In response to such negative externalities, the UNSC is likely to turn its attention to the sources that generate them.

Regardless of whether the normative and self-interested mechanisms operate individually or in mutual reinforcement, they support the expectation that severe conflicts accompanied by deaths and displacement are likely to be treated as a priority by the UNSC:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): More severe conflicts are more likely to receive the attention of the UNSC.

This hypothesis reflects a general expectation, which is consistent with both the ‘governance’ and ‘concert’ models, depending on the mechanism that connects severity with attention. However, we also suspect that the UNSC's agenda has become more sensitive to conflict severity over time. Since the 1990s, a broad normative shift, privileging individual rights over those of states and collectives, has been under way, shaping global governance institutions. The UN has moved towards a human-centred security paradigm, as reflected in the 2005 adoption of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ and an increasing focus on civilian protection in UN peacekeeping (Hultman, Kathman and Shannon Reference Hultman, Kathman and Shannon2013; Oksamytna and Lundgren Reference Oksamytna and Lundgren2021; Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg2020). While these shifts have been lined with contestation and continue to generate debate, such as during the UNSC's deliberations over Syria in the 2010s, they are likely to have made the UNSC more sensitive to conflicts that pose grave risk for civilians. This logic is compounded by the globalization of information, which has gathered speed in the post-Cold War period, increasing the probability that widespread violation of human rights and violence against civilians will be brought to more general attention. Consequently, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The UNSC was more attentive to severe conflicts in the 2000s than in earlier decades.

State Interests

The traditional realist view is that IOs are epiphenomenal – mere tools in the hands of the great powers (Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer1994) – and that the UNSC's P5, empowered by their veto prerogatives and greater resources, dominate proceedings and decision making (Voeten Reference Voeten2001; Vreeland and Dreher Reference Vreeland and Dreher2014). This would suggest that what enters the UNSC's agenda is shaped by the interests of the members and, owing to their veto and expansive resources, the permanent members in particular.

The agenda-setting influence of the permanent members does not, however, have a determinate impact: it can be used to place an issue on the agenda, but it can also be used to keep it off. Previous research (Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2003) has distinguished between agenda inclusion, that is, the introduction of issues on to the agenda, and agenda exclusion, that is, the keeping of issues off the agenda. Applying that distinction to the UNSC, one can identify arguments favouring both expectations. It is reasonable, first, to expect that strong P5 interests are associated with agenda inclusion. If members use the UN instrumentally, either to share the burdens of action across a wider coalition (Voeten Reference Voeten2001) or to legitimize an intervention (Hurd Reference Hurd2008; Voeten Reference Voeten2005), they will need to place their concerns on the agenda. US attempts to cultivate the UNSC's support for military campaigns against Iraq in the 1990s and early 2000s serve as an example for this dynamic.

It is also reasonable to expect, however, that the P5 engage in agenda exclusion, seeking to manage high-stakes issues without the added complication of collective decision making. Boulden (Reference Boulden2006: 413) argues that in situations where ‘one or more of the permanent members have a strong or vital interest … [t]he most likely [outcome] is that the issue does not make it onto the agenda at all’. If the UNSC operates more akin to a concert mechanism that functions to harmonize the interests of the great powers and protect their spheres of interest, it would lead them to keep core issues off the table, letting such issues be dealt with independently or via IOs over which they have greater control (such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO]).

To investigate which direction of effects dominates, we formulate two rival hypotheses regarding the influence of P5 interests:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): Conflicts in locations where P5 members have strong shared interests are more likely to receive the attention of the UNSC.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Conflicts in locations where P5 members have strong shared interests are less likely to receive the attention of the UNSC.

Next to the P5's collective interest, agenda setting is also likely to be shaped by their individual interests. At the end of the day, the P5 are not uniform members of some low-stakes committee seeking compromise at all cost; rather, they are great powers with diverging interests and oftentimes conflictual perspectives on the UN's role. For that reason, when faced with a given conflict, each member will view it differently, considering how their particular geopolitical, economic and diplomatic interests are advanced or impeded by potential UNSC action.

First, the P5 differ regarding their economic and military resources, awarding them different strategic flexibility. While most of the P5 have some options for action outside the UNSC, the United States, privileged by its unique military capability and wide alliance networks, has particularly expansive outside options (Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2022; Voeten Reference Voeten2001). Secondly, for any conflict country, the P5 have varying economic interests. Permanent members with extensive trade with a conflict country will likely take a different view on the benefits of UNSC action than a member with less or no trade. Thirdly, the permanent members are subject to different expectations, both from home and abroad, regarding their international action. Governments of the three liberal-democratic members of the UNSC (the P3) are more likely to be domestically penalized should they refrain from responding to situations that involve serious human rights violations (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Fourthly, the P5 hold diverging views on the normative direction of global governance and make different interpretations of international law. Russia and China are profoundly sceptical of the interventionist turn in global governance and have sought to prevent it, for example, by blocking action in Syria and elsewhere.

Due to these differences, we expect that some states will seek to bring to the UNSC issues where their interests are strong, while others will prefer to involve the UNSC only in situations when their core interests are not at stake. Recognizing that the permanent members will view the role of the UNSC differently, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): The impact of interests on agenda setting will vary across the permanent members.

This hypothesis leads us to expect that measures of P5 members' interests will have varying impacts on the UNSC's attention when evaluated statistically. To be clear, our belief in H4 will strengthen if we observe that measures of some P5 member interests are statistically different from those of other P5 members.

Interest Heterogeneity

A third factor likely to shape agenda setting is the distribution of interests. The conventional view is that greater preference diversity increases transaction costs, leading to a lower likelihood of agreement (Axelrod and Keohane Reference Axelrod and Keohane1985; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002). This argument has been presented in the context of individual organizations, including the European Union (EU) (Golub Reference Golub2007) and the UN (Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2020; Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2022; Beardsley and Schmidt Reference Beardsley and Schmidt2012). With regard to agenda setting, this logic can be extended to support a conjecture of anticipation effects: when facing a situation where UNSC members hold divergent preferences, an individual member will rationally expect that agreement is less likely and will refrain from expending political resources to place it on the agenda.

However, if actors attain significant benefits from placing something on the agenda in and of itself, we may rather expect that greater interest heterogeneity is associated with a higher likelihood of agenda setting. In any given situation, the more preferences diverge, the more likely that there is at least one member whose cost–benefit calculation motivates the effort to place it on the agenda.Footnote 2 The historical record suggests that UNSC members do not shy away from placing issues on the agenda, even when they anticipate defeat. For example, in the 2010s and early 2020s, the P3 repeatedly sought to table resolutions on Syria, despite knowing full well that these deliberations would end in Russian and Chinese vetoes. In light of increasing mediatization and symbolic politics, it is likely that agenda pay-offs – being able to claim that one publicly defended a principle or ‘made something part of the conversation’ – has become more pronounced, further offsetting the anticipating effect. Since we want to test which of these logics dominate, we formulate two hypotheses with opposing expectations:

Hypothesis 5a (H5a): Conflicts in locations where UNSC members have highly divergent interests are more likely to generate the attention of the UNSC.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b): Conflicts in locations where UNSC members have highly divergent interests are less likely to generate the attention of the UNSC.

Data

Our theoretical expectations relate to the drivers of the UNSC's attention. We want to understand the factors that govern the selection from the set of all active conflicts of a smaller set for inclusion on the UNSC's formal agenda. To model this selection process empirically, we first construct a time-series cross-sectional dataset with yearly observations on all states experiencing intrastate armed conflict in the 1989–2019 period. We then combine it with data on formal meetings of the UNSC, which allows us to identify which conflicts were selected for attention in a given year. To test our explanations, we construct multiple indicators of conflict severity, interests and interest diversity. Finally, to allow us to adjust for confounding factors, we include a series of control variables. The following describes these steps in greater detail.

Data on Conflicts and UNSC Meetings

We use Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) data and follow their definition of armed conflict as a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year (Petterson and Öberg Reference Pettersson and Öberg2020). Conflict dyads are aggregated to the country level. We include internationalized intrastate conflicts but exclude the few observations that pertain to interstate conflicts. In total, these data cover 905 conflict-country-years (represented by squares in Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Count of UNSC meetings by conflict-year, 1989–2019.

Notes: Active armed conflicts marked with boxes. Number of UNSC meetings marked in shades of grey. Countries without armed conflicts not shown.

To identify the conflicts that enter the UNSC's agenda, we use Frederking and Patane's (Reference Frederking and Patane2017) Collective Security Dataset, which covers 5,830 formal meetings between 1989 and 2019. For each meeting, we extract the agenda item, which provides information on the conflict country discussed. We follow Frederking and Patane's modification of the original UN coding and disaggregate such agenda topics as ‘The Situation in the Middle East’ into the countries actually discussed (in this case, Syria, Lebanon or Israel).

Dependent Variable: Agenda

Based on these data, we construct two measures of UNSC attention, coded at the conflict-country-year level. The dichotomous variable Agenda is coded 1 if a conflict country was included among the agenda items discussed by the UNSC in the observed year and as 0 otherwise. A dichotomous measure is suitable to reflect the core selection dynamic that distinguishes between conflict countries that enter the agenda from those that do not. Similar approaches have been used by Benson and Gizelis (Reference Benson and Gizelis2020) and, from a survival perspective, Binder and Golub (Reference Binder and Golub2020). To capture variation in attention, we also construct the variable Agenda count, which records the number of meetings on a given conflict country in the year of observation.

Figure 1 provides an overview of these data, showing the count of meetings held for each conflict-country year in our sample. We observe three key patterns. First, there is considerable country-level variation. In any given year, attention is focused on a smaller subset of conflicts, whereas the majority stay outside the UNSC's agenda. This reinforces our suspicion that the UNSC is economizing its attention and that conflict- and country-related characteristics can explain variation in agenda setting.

Secondly, while the country-level variation is a dominant pattern, we also note that there is variation across regions of the world. Conflicts in Latin America, South-East Asia and South Asia are considerably less likely to end up on the UNSC's agenda than conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Europe and Central Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. These patterns suggest that UNSC dynamics are partly shaped by spheres of geopolitical interest. For example, Latin America has long been considered a strategic ‘backyard’ of the United States, and it appears that this has gone hand in hand with agenda exclusion, leading to very little UNSC deliberation on conflicts in this region.

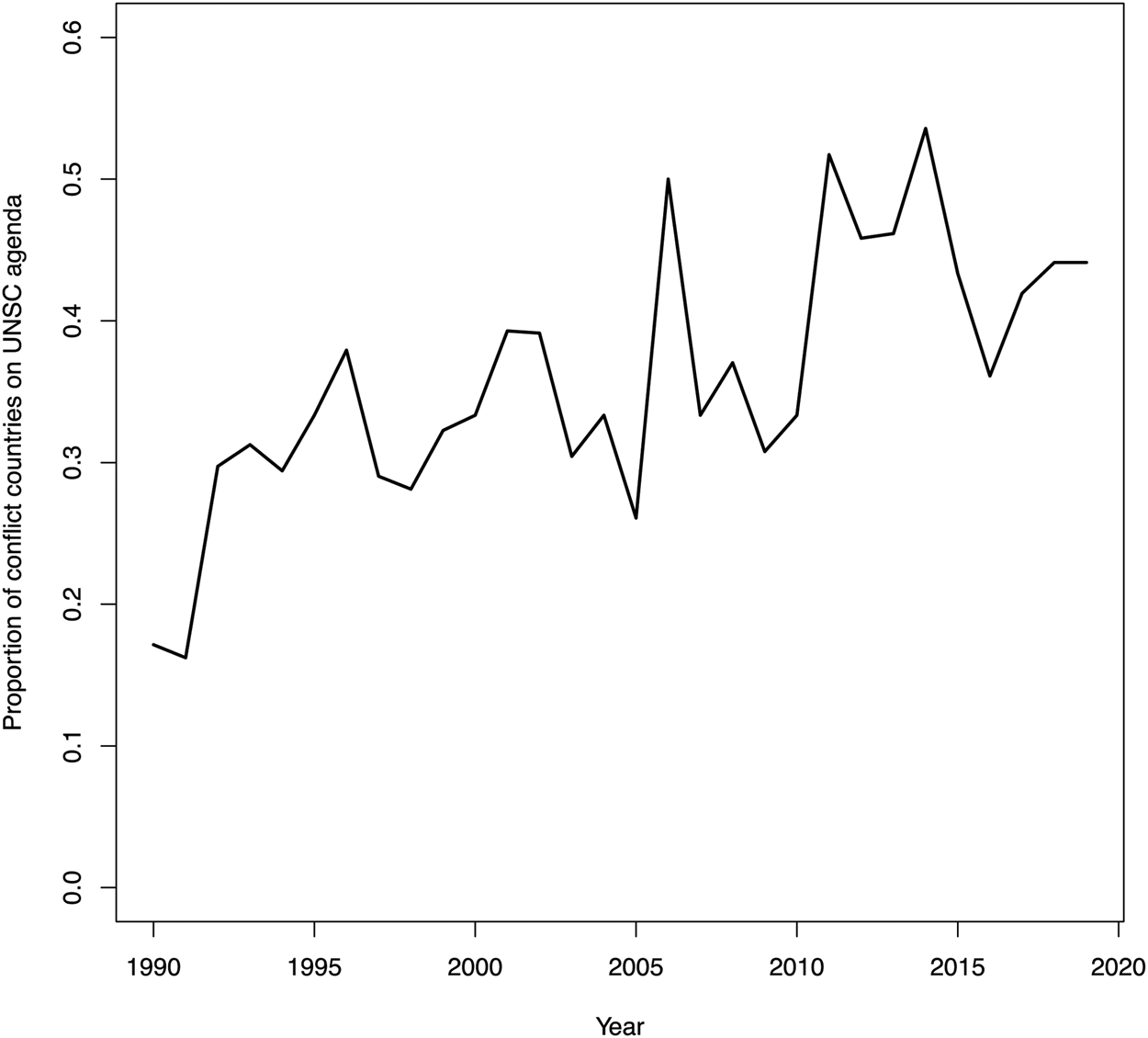

Thirdly, the UNSC is becoming more attentive. In 1989, when the UNSC was still shaped by Cold War antagonisms, a mere 17 per cent of conflicts ended up on the UNSC's agenda. In 2011, this had risen to 51 per cent, and it stayed at over 40 per cent for most years in the 2010s. Figure 2 illustrates this pattern, plotting the proportion of conflict countries that are included on the agenda over time.

Fig. 2. Proportion of conflict countries addressed in meetings of the UNSC, 1989–2019.

Taken together, these descriptive patterns reinforce the conclusion that the UNSC's attention is selective, varying both across locations and over time. To investigate this variation, we collect information on characteristics that correspond to our three main factors of theoretical interest: conflict severity, interests and interest heterogeneity. We also measure several control variables. Summary statistics of all variables are presented in the Online Appendix.

Independent Variables: Conflict Severity, Interests and Interest Heterogeneity

To capture variation in conflict severity, we include a measure of Battle deaths, operationalized as the yearly count of ‘deaths caused by the warring parties that can be directly related to combat’ in the conflict country (Pettersson and Öberg Reference Pettersson and Öberg2020). To represent the humanitarian impact, we include a measure of the yearly count of Civilian fatalities in one-sided violence, drawing again on UCDP data (Eck and Hultman Reference Eck and Hultman2007; Pettersson and Öberg Reference Pettersson and Öberg2020), as well as the variable Refugees, operationalized as the count of worldwide refugees and internally displaced persons originating in the conflict country (calculated using United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR] data).

We represent interests with four measures that proxy the political, military, economic and geographic linkages between conflict countries and the P5. These four interest variables are measured both as P5 averages and as individual measures varying across the P5. The former is the conventional approach in the literature (Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2020; Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2022; Beardsley and Schmidt Reference Beardsley and Schmidt2012; Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020), whereas the latter represents our ambition to break with this approach and investigate interests in a disaggregated manner.

We follow Signorino and Ritter (Reference Signorino and Ritter1999) and represent political interest based on the similarity of foreign policy and alliance portfolios. The variable P5 mean s-score is the mean dyadic affinity score (s-score) of the P5 and the conflict country, whereas the individual-level variables are measured for each permanent member. The variables capture the extent to which the P5 have shared or opposing interests with the conflict country, with higher values representing greater interest affinity. To reflect the varying capabilities of the P5, we use capability-weighted s-scores, while introducing alternative formulations in our robustness tests.

We measure economic interests with the variable Trade, operationalized as the amount of the P5 countries' trade with the conflict country as a proportion of all their trade. We calculate this from Correlates of War dyadic trade data (Barbieri, Keshk and Pollins Reference Barbieri, Keshk and Pollins2009). If the conflict country represents a significant trading partner, indicating that the P5 may suffer more from extended conflict, this will be reflected in higher values on this variable. Again, individual variables are analogously constructed.

We measure military interests based on Arms exports, operationalized as the amount of the P5 countries' arms exports that are directed to the conflict country as a proportion of all their arms exports. We use data from the 2021 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Arms Transfer Database. For countries with significant military interests, as proxied by arms exports, this variable takes a higher value.

We proxy geopolitical spheres of interest with the dichotomous variable Contiguity, coded as 1 for conflict countries that are directly contiguous to a P5 country, either via a shared land border or separated by less than 400 miles of water. We use information from the Correlates of War direct contiguity data (Stinnett et al. Reference Stinnett2002). Our focus on disaggregated interest leads us to focus on the P5, for which consistent time-series are available, but in our robustness tests, we also include measures of the collective interest of the UNSC's ten elected members (E10).

To evaluate our hypotheses relating to interest heterogeneity, we calculate diversity measures of interest based on s-scores. We calculate the standard deviation of P5 interests in relation to a conflict country in the year of observation. Higher values indicate that the P5 have more diverse interests, whereas lower scores indicate greater interest homogeneity. For natural reasons, this variable has no individual-level measurements. All severity variables are measured in the year of observation and remaining variables in the year prior to observation.

Control Variables

We adjust for potential confounders. First, we control for Conflict incompatibility, distinguishing conflicts fought over territory from those fought over government (Gleditsch et al. Reference Gleditsch2002). Incompatibility type may correlate with several of our main independent variables and the urgency with which the UNSC views a particular conflict. For example, the UNSC may view territorial conflicts as a threat to foundational norms (territorial integrity), leading it to treat such situations with greater urgency.

We also control for the presence of UN Peacekeeping operations. Once such operations have been established, they tend to generate long series of meetings and resolutions, as the UNSC conventionally extends mandates in six-monthly or yearly instalments. Recognizing the impact of institutional stickiness on the UNSC's agenda, we expect that peacekeeping operations are associated with a greater number of meetings.

Finally, we control for three foundational time-varying country characteristics that may feasibly be correlated with both our independent and dependent variables. We measure country Population in millions using World Bank data. To measure a country's development level, we include the variable GDP [gross domestic product] per capita, again using World Bank data. We proxy regime type with the variable Liberal democracy index, sourced from the Varieties of Democracy dataset (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2020). Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table A1 in the Online Appendix.

Results

We report our results in Figures 3–8. We present coefficient plots and quantities of interest. Full regression tables, including robustness checks, are available in the online Appendix (see Tables A2–A19). Given the binary dependent variable and the panel structure of the data, we employ a logit estimator and include a cubic time polynomial (Beck, Katz and Tucker Reference Beck, Katz and Tucker1998). To control for unobserved cross-sectional heterogeneity, we include random effects for conflict countries. To facilitate interpretation and comparison, all coefficients are standardized.

Conflict Severity

Our first hypothesis was that conflicts that generate a higher number of battle deaths, civilian fatalities and refugees would be more likely to enter the UNSC's agenda. We find some support for this conjecture. In the full sample (1989–2019), battle deaths are positively correlated with the probability of UNSC attention, though we cannot reject the null of no association between attention and civilian fatalities and refugees (see Figure 3).Footnote 3

Fig. 3. Conflict severity, P5 interests and interest heterogeneity as predictors of UNSC attention.

Notes: Displayed are logit coefficients with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All continuous predictors are mean-centred and scaled by 1 standard deviation. Random effects not shown.

Figure 4 exhibits predicted probabilities. Like the other measure of conflict severity, battle deaths are right-skewed, reflecting the fact that many conflicts are of low intensity, but shifts in severity are associated with substantial changes in UNSC attention. For example, the probability that a conflict with twenty-five deaths (the minimum to be classified as an armed conflict) enters the UNSC agenda is about 35 per cent, whereas it is more around 60 per cent for an otherwise identical conflict with 25,000 battle deaths.

Fig. 4. Predicted probabilities of UNSC attention as a function of battle deaths.

Note: Average predictive margins with 95 per cent confidence intervals (Model 1).

The longitudinal association between increases in conflict severity and the UNSC's attention is exemplified in Figure 5, exhibiting the count of annual battle deaths in Yemen next to the count of UNSC meetings that related to this country. Reflecting the wider pattern of an association between the two variables, the curves fit each other snugly, rising and falling together. We note, first, that Yemen experienced a bout of violence in 1994, as clashes between forces of the pro-union north and the separatist south led to an estimated 1,489 battle deaths, triggering a contemporaneous increase in the number of UNSC meetings. Next, following the swift defeat of separatist forces in southern Yemen, violence subsided from 1995, as did the UNSC's attention. Finally, we note that from 2009 onwards, violence again escalated in Yemen, reaching more than 6,000 battle-related deaths in 2015. As reflected in the black line, this escalation maps well onto the number of Yemen-related meetings held in the UNSC, which increased from zero in 2007 to fourteen, or more than one per month on average, in 2019.

Fig. 5. Battle deaths in Yemen and related UNSC meetings, 1989–2019.

Our findings regarding conflict severity replicate and extend findings in previous studies (for example, Benson and Gizelis Reference Benson and Gizelis2020). These results do not necessarily help us distinguish the precise nature of the underlying mechanism. It may be that the UNSC reacts to these situations because it seeks to promote its Charter responsibilities, but it may also be that it does so because severe conflicts generate negative externalities that threaten the interests of UNSC members. One way to start disaggregating the two is to examine variation over time. Since we know that the normative context has changed over time, there exists an opportunity to tease out evidence that can be informative about the underlying mechanism.

This brings us to our second hypothesis, which submitted that normative shifts, in particular, the increasing view that state sovereignty is conditioned on adequate protection of human rights, have made the UNSC more attentive to conflict severity over time. In Figure 6, we plot the coefficients for models estimated on two temporal subsets of the data, using the 2005 adoption of R2P as the break point. We observe that battle deaths are not a statistically significant predictor in the 1989–2004 data, but significant in the period from 2005, suggesting that the UNSC has become more sensitive to conflict severity over time. For civilian victimization and refugees, the point estimate suggests the possibility of a similar shift, but the estimates are too noisy to determine whether this represents a systematic effect. Overall, we view these data as an indication that the UNSC has become more attentive to civil conflict overall but not necessarily more attentive to the core concern of human rights violations, as far as these are captured by our proxies of civilian fatalities and refugees. Fitting time-varying coefficients models, an approach with increasing application in international relations (IR) (see, for example, Anderson, Mitchell and Schilling Reference Anderson, Mitchell and Schilling2016), corroborates these patterns: Figure A4 in the Online Appendix shows that the association between battle deaths and attention as gradually increasing and is statistically significant from around 2005.

Fig. 6. Temporal shifts in determinants of UNSC attention.

Notes: Displayed are logit coefficients with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All continuous predictors are mean-centred and scaled by 1 standard deviation. Random effects and not shown. Due to collinearity, the Peacekeeping variable is excluded from the 2005–19 model.

Interests

Turning to our third hypothesis – that the interests of the P5 shape the UNSC's attention – we find mixed support in favour of what we called ‘agenda exclusion’ (see Figure 3). The negative coefficient on the s-score variable indicates that, all else equal, conflict countries with which the P5 are politically aligned are less likely to enter the UNSC's agenda. Trade, Arms exports and Contiguity are not statistically significant in the complete sample. However, the data suggest that there have been shifts in the impact of these variables over time (see Figure 4). The s-score variable is significantly more negative during 2005–19, suggesting that agenda exclusion has become more dominant from 2005 and onwards, possibly in reflection of the greater tensions in the UNSC (see von Einsiedel, Malone and Ugarte Reference Von Einsiedel, Malone and Ugarte2015). We also note that the Trade variable was predicted negatively in the 1989–2004 period, indicating that conflicts in important trading partners were disproportionately kept off the UNSC's agenda during this time.

However, for reasons explained earlier, we interpret results based on collective s-scores very cautiously and place greater emphasis on our disaggregated measures. It should be recalled that our fourth hypothesis was that the interests of the P5 will have divergent effects on agenda setting in the UNSC. Figure 7 exhibits the result of models using disaggregated measures of P5 interests (Table A4 in the Online Appendix provides full results). We immediately note possible differences across the P5.Footnote 4 The general tendency is that the proxies for the interests of the United States are associated with agenda exclusion, whereas those of Russia are associated with agenda inclusion. There is a considerable amount of uncertainty overall.

Fig. 7. Individual P5 interests as predictors of UNSC attention.

Notes: Logit coefficients with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All continuous predictors are mean-centred and scaled by 1 standard deviation. Random effects and controls are not reported. France's s-score variable and contiguity variable for the United States, UK and France are removed due to collinearity. There are no colonial links variables for the United States and China, and no ODA data for Russia and China.

For the United States, the clearest finding is the negative association between trade interests and attention by the UNSC. This partly reflects the fact that several large trading partners of the United States, including Israel, the UK and Mexico, appear in the data, but the relationship holds even if we subset the data only to Sub-Saharan Africa (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix), suggesting that the data are consistent with an agenda-exclusion interpretation.

For China, the trade variable predicts positively, which is not only partly a reflection of China's increasing economic activity in the developing world, but also driven by the fact that several of China's significant trading partners, including Iraq, Sudan and the Philippines, have featured frequently on the UNSC's agenda. For France and the UK, we observe no significant relationships, indicating that they are less successful in influencing the agenda of the UNSC in favour of their interests. While both countries view the UNSC as a key instrument of their foreign policies, these results are consistent with the view that the UNSC is primarily shaped by its most populous and militarily more resourced members (see, for example, Voeten Reference Voeten2001).

For Russia, three out of five estimates are positive. The s-score coefficient is positive and statistically significant, indicating that conflicts in countries politically aligned with Russia are more likely to receive the UNSC's attention. Especially during the 1990s, the UNSC turned its attention to conflicts in the post-Soviet space, where countries typically have a UN voting record similar to Russia's. The positive coefficient for geographic contiguity and colonial links (which, in this case, equals the post-Soviet domain) reinforce the interpretation that Russia seeks to ensure the UNSC's involvement in conflicts in its near abroad.

Based on the collected data, we cannot be certain whether the observed results are due to conscious, strategic action by the observed P5 member. An alternative interpretation, which is still consistent with our hypothesis, is that observed correlations may be due to the manoeuvring by other actors. For example, if we take the example of Russia's near abroad, it cannot be ruled out that the observed pattern is due to other UNSC members seeking to place these issues on the UNSC's agenda to hurt Russia, rather than to Russia's own actions.Footnote 5

It is also worth noting that the estimated effects are additive. For example, consider the effect of trade, which predicts negatively for the United States but positively for China. This implies that conflicts in countries with strong trade ties to China but weak ties to the United States are considerably more likely to receive the UNSC's attention than conflicts in countries with strong trade ties to the United States and weak ties to China (for a hypothetical example, see Table A19 in the Online Appendix).

Taken together, these results suggest that there is a dividing line in how these members employ the UNSC to promote their interests. The most likely explanation is that some members have more expansive outside options – both with regard to institutional forums for deliberation and the resources and alliances that facilitate peace interventions – allowing them a greater freedom to choose alternative response mechanisms when their core interests are at stake. The historical record shows that the United States, in particular, though also the UK and France, have frequently opted to respond to armed conflicts via such military alliances as NATO or such regional organizations as the EU. Compared with the UN, these organizations offer greater operational and ideational alignment, benefits that may be particularly important when key interests are at stake. In comparison, Russia has fewer such organizational alternatives, leading it to seek to tackle situations of concern via the UNSC.

Interest Heterogeneity

Finally, we examine the evidence pertaining to H5a and H5b, that is, our expectation that the diversity of P5 interests shapes UNSC attention, either negatively or positively. Our results clearly favour the latter expectation. Estimated on the general sample (see Figure 3), the coefficient on preference diversity is positive and statistically significant, indicating that a greater diversity of interests makes it more likely that the UNSC will deliberate on a situation. This is what we would expect to observe if the ‘agenda entrepreneurship’ mechanism dominates over the ‘anticipation effect’, which has so far been at the centre of theorizing in the literature (Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2020; Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020; but see Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2022). As Figure 8 shows, the substantive effect is non-trivial. A shift from the first quartile of preference diversity (0.18) to the third quartile (0.27) is associated with a 4 percentage-point increase in the probability that a conflict country enters the agenda of the UNSC.

Fig. 8. Predicted probabilities of UNSC attention as a function of P5 interest heterogeneity.

Note: Average predictive margins with 95 per cent confidence interval.

Controls

We focus our discussion here on the main results, but our control variables (see Figure 3; see also Table A2 in the Online Appendix) deserve a few words. We find that peacekeeping operations are strongly predictive of UNSC attention. Since the UNSC regularly renews the peacekeeping mandates, this association is not surprising, but reinforces the conclusion that there exist significant path dependencies in the UNSC. We also find that civil conflicts over government are more likely to become agenda items in the UNSC than are conflicts over territory. This requires further examination but appears to suggest that the UNSC considers secessionism as an issue that states are better suited to deal with themselves. We find no significant results for democracy or GDP per capita.

Robustness

To ensure that our results are not driven by particularities of estimation, specification or operationalization, we carry out additional tests. First, we test whether our results are sensitive to alternative estimators and specifications. We estimate a negative binomial model, using the count of annual meetings on a given conflict country as the dependent variable. The results (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix) indicate that all main results are robust to this alternation in the econometric approach, which also suggests that the same variables explain the extent of UNSC attention. Our key results are also robust to the inclusion of region fixed effects, which provide us with an opportunity to estimate regional base probabilities of UNSC attention (see Figure A3 in the Online Appendix). Excluding control variables (see Tables A6 and A7 in the Online Appendix) reduces the precision of the estimate for mean P5 s-scores but does not change the key results, including for the disaggregated measures. We estimate linear probability models (see Tables A8 and A9 in the Online Appendix) and find that, with the exception of the disaggregated measure for Chinese trade importance (which is positive but no longer statistically significant), all key coefficients retain their sign and statistical significance. Table A10 in the Online Appendix shows that the UNSC's attention is sensitive to civilian fatalities and refugees if these variables are lagged by one year.

Secondly, we estimate a series of models using alternative operationalizations of interests. Table A11 in the Online Appendix presents the results of two models that substitute the standard weighed s-score measure with the unweighted s-score and Häge's (Reference Häge2011) chance-corrected kappa scores. Our key results for conflict severity and preference diversity are robust to these alternatives, but the coefficient for the mean P5 preference weakens.

Thirdly, while we have consciously focused on the UNSC's P5, we recognize that the interests of the E10 may also play a role (see, for example, Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020). Including measures to represent mean E10 interests and E10 preference diversity does not alter our key results (see Table A12 in the Online Appendix). Adding a variable that records the difference between the P5's and the E10's mean preferences similarly leaves our key results unchanged, while suggesting that such differences do not provide a systematic predictor of the UNSC's attentions.

Conclusion

We advanced and tested a theoretical argument regarding the attention of the UNSC. Based on panel data covering 905 conflict-country-years and 5,830 meetings of the UNSC, we made three main findings. First, the severity of a conflict influences whether the UNSC will place it on its agenda. Conflicts generating significant battle deaths are more likely than other similar conflicts to receive the UNSC's attention, a pattern that has strengthened since 2005. Secondly, as indicated by disaggregated measures of interests, the P5 use the UNSC in different ways, likely reflecting their varying capability to resort to alternative venues and solutions. Thirdly, in contrast to conventional wisdom, we find that conflicts where the UNSC P5 have divergent interests are more likely to receive the UNSC's attention than are similar conflicts where their interests are aligned.

Each of the findings raises implications for how we should understand the UNSC and its role in world affairs. To begin with, they suggest that a leading debate in the literature about the UNSC – that is, whether it mainly is governed by an organizational mission to promote peace and protect human rights, or mainly constitutes an institutional mechanism to negotiate tensions between great powers – is misguided. The available evidence cannot lead us to reject either. Rather, both perspectives seem to carry value in interpreting the data. On the one hand, the UNSC is broadly responsive to armed violence, even in parts of the world where the P5 lack salient interests. On the other hand, the evidence suggests that the P5 shape the UNSC's agenda to protect their interests. Going forward, researchers should abandon the ambition to resolve the debate between the sweeping claims implicit in the ‘governance’ and ‘concert’ perspectives. The focus should rather lie on developing conditional theories of the precise factors and mechanisms that influence how UNSC members balance their parochial interests against the broader goals laid down in the UN Charter.

Next, our findings reinforce the relevance of efforts to develop theoretical frameworks that can capture both individual state preferences and the strategic context that emerges from the collective distribution of preferences in the UNSC. Multilateral bargaining theory has already shown promise in research on the UNSC (see, for example, Allen and Yuen Reference Allen and Yuen2022), and the integration of theoretical applications developed at the domestic level or for other international organizations (see, for example, Thomson et al. Reference Thomson2006) can advance this body of research even further. A related priority is to develop better empirical measures of interests, where the workhorses of the discipline (such as measures based on voting in the UN General Assembly) remain unsatisfactory in many ways. This study has taken some steps, testing indicators for a range of political and economic interests, but alternative measures – for example, by researching the historical and diplomatic linkages between the P5 and conflict countries – could provide additional nuance.

Finally, this study suggests some limitations to rationalist-institutionalist approaches focused on transaction costs or expected utilities flowing from agreement. Our finding that greater interest heterogeneity – which essentially reflects disagreement – is correlated with a greater probability of the UNSC meeting challenges the notion that agenda gatekeepers would prefer to hold meetings only under conditions that are likely to lead to a policy decision. It rather suggests that the threshold for holding a meeting is relatively low and more easily cleared when member preferences diverge. Under such circumstances, it is more likely that at least one member has an interest in placing the issue on the agenda, regardless of the outcome. While states searching for efficacy will forum-shop – witness the turn to the General Assembly and its ‘Uniting for Peace’ mechanism as a possible response to Russia's war in Ukraine – there is little in our data that suggests that increasing tensions between the P5 will significantly reduce their willingness to bring issues to the UNSC. The implication is that researchers should investigate the UNSC not only as a mechanism to bargain over collaborative solutions, which is likely to suffer from stronger P5 tensions, but also as a venue for contestation and posturing, with advocacy and communication at its centre, which is likely to endure.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000461

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in the Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WEHJBP

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the Midwest Political Science Association (MPSA) Annual Conference, in April 2021, and at the Global and Regional Governance Workshop, Stockholm University, in April 2021. We are grateful for the insightful comments offered by Kseniya Oksamytna, Karin Sundström, Per Ahlin, Michael Broache, Hyunki Kim, Faradj Koliev, Will Underwood, Carl Vikberg, Ludvig Norman, Jonas Tallberg and Lisa Dellmuth.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (Grant Number 2017-00781).

Competing Interests

None.