INTRODUCTION

Why do people help others in need? What factors encourage people to volunteer with charities, schools, long-term care homes, and community associations? When do highly trained professionals, such as lawyers, provide their services without billing their clients? Lending a helping hand, volunteering, and providing professional services for free are all examples of altruistic behaviors. Some may question whether the provision of free legal services (“pro bono”) by lawyers is altruistic, though such efforts make an important inroad into addressing the gap in access to justice. A rich law and society tradition suggests the efforts by lawyers to close the gap in access to justice, particularly through the giving of legal services, are of importance. This tradition concerns itself with human nature and how people respond to instances of disadvantage (Edelman Reference Edelman1977) and where lawyers’ actions shape mechanisms for addressing gaps in justice (Sarat and Scheingold Reference Sarat and Scheingold2006). Recently, this tradition has sought to encourage broader interdisciplinary reflections and cogent theory development to understand people’s interaction with the law (Savelsberg et al. Reference Savelsberg, Terence Halliday, Morrill, Seron and Silbey2016). Following this tradition, we begin this article with a discussion of altruism and its relevance for pro bono work among lawyers, which leads us to develop an integrated perspective on lawyers’ pro bono work, derived from multiple disciplines, sharpened through qualitative interviews, and then tested empirically using a large-scale survey of lawyers.

Altruistic behaviors have several key features. Most importantly, altruistic acts are motivated by concern or regard for others rather than for oneself. In his book, The Altruism Question, C. Daniel Batson (Reference Batson1991, 6) defines altruism as “a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing another’s welfare.”Footnote 1 Altruism is also voluntary and intentional (that is, meant to help someone else) and is action undertaken without expectation of external reward (Simmons Reference Simmons1991; Healy Reference Healy2004). Yet altruism is not without contention. Some scholars argue that there is no absolute altruism in which motivation for an action is completely without concern for self. A degree of selfishness is present even in the most apparently altruistic actions (D. Smith Reference Smith1981, 23). Nonetheless, the study of relative altruism remains of keen interest to scholars as evidenced by the emerging academic discipline of “altruistics” that studies all forms of altruism.Footnote 2 Altruistics (or, alternatively, “voluntaristics”), as a discipline, includes phenomena such as philanthropy, giving behavior, nonprofit organizations, volunteering, and civil society (D. Smith Reference Smith2013).

Scholars of altruistics often explore volunteering behavior (Hoogervost et al. Reference Hoogervorst, Mertz, Roza and van Baren2016; Cassidy et al. Reference Cassidy, Rose Thompson, Hickling and Priebe2019; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhang, Li and Xie2019). Volunteering can be on a formal or informal basis. Formal volunteering is typically carried out to contribute collective goods that benefit others usually through organizations (for example, volunteering to fundraise for the United Way or the Heart and Stroke Foundation). Informal volunteering tends to be assistance provided to friends and neighbors and is not organized in any formal way (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a, 700; Mitani Reference Mitani2014, 1024). Consistent with the general concept of altruism, volunteering—whether formal or informal—is not aimed directly at material gain and nor is it mandated or coerced by others (Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009, 272).Footnote 3 This is where altruism encounters some discord when applied to lawyers’ pro bono work. Is pro bono assistance freely given, or is it a form of “voluntold” whereby lawyers are required to give of their time as a condition of employment? Further, is pro bono assistance driven by economic incentives, such as reputation and client recruitment? Do the benefits of pro bono (to the lawyer or law firm) undermine an altruistic basis for action?

In fact, the benefits of pro bono work may be even more expansive. Research demonstrates that altruistic acts and volunteering, in particular, offer many benefits, including improved health (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2007; Huang Reference Huang2018; Yeung Reference Yeung2018) and life satisfaction (Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Aatsen, Slagsvold and Deindl2018). Those who volunteer their expertise as lawyers, for example, gain professional development through exposure to broader responsibilities at early career stages (Piatak Reference Piatak2016) and a sense of more meaningful work (Dwyer et al. Reference Dwyer, Bono, Snyder, Nov and Berson2013). Research reveals that law firms gain through greater retention of junior lawyers within workplaces where volunteering is encouraged (Granfield Reference Granfield2007b). These wider benefits, whether as motivators or welcome gains, do not completely dismiss an underpinning of altruism in volunteering generally (Kolm Reference Kolm2006a; Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Aartsen, Slagsvold and Deindle2018) or in the provision of free legal services specifically (Juergens and Galatowitsch Reference Juergens and Galatowitsch2016).

Despite recognition that altruism yields worthy benefits—not only to the recipients of altruistic acts but also to volunteers and to organizations that lend their employees’ services (Granfield Reference Granfield2007b; Yeung Reference Yeung2018)—there are significant gaps in our theoretical and empirical knowledge of altruism. Theoretical explanations of altruism remain fragmented across disciplinary lines, with psychologists, sociologists, and economists purporting different perspectives on the factors that prompt altruism. All three disciplines speak broadly to altruism, with many studies targeting volunteer work as a form of (relative) altruism. Psychologists examine whether people volunteer based on their personality and values (Eisenberg Reference Eisenberg1986; Mitani Reference Mitani2014). Sociologists assess the role of normative expectations of others and social resources in promoting volunteering (Clary, Snyder, and Strukas Reference Clary, Snyder and Strukas1996; Wilson Reference Wilson2000; Kelemen, Mangan, and Moffatt Reference Kelemen, Mangan and Moffat2017). Economists assume volunteering is based on rational behavior that encourages exchange and career building (Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Piatak Reference Piatak2016). However, more work is needed to bridge the disciplinary divides that produce a multidimensional framework on altruism (D. Smith Reference Smith1999; Kelemen, Mangan, and Moffatt Reference Kelemen, Mangan and Moffat2017). Such a multidimensional framework could hold particular value to our currently thin understanding of the organizational settings in which giving takes place. Interestingly, the vast amount of research on altruism, across disciplines, focuses attention on individual motives and rationales with little regard for the organizational contingencies that shape and nurture giving.

Furthermore, the empirical literature on altruism focuses heavily on volunteer work performed by individuals outside of their paid employment or occupational skills (see Wilson Reference Wilson2012; Mitani Reference Mitani2014; Aydinli et al. Reference Aydinli, Michael Bender, van De Vijver, Cemalcilar, Chong and Yue2016). This literature contrasts individuals’ acts of giving, often one-shot experiences, with the operations of voluntary and nonprofit organizations that seek to socially manage volunteerism on an ongoing basis (D. Smith Reference Smith1999; Healy Reference Healy2004). At the level of organizations, the spotlight shines on charities and associations—organizationally produced contexts for altruism—with less, though growing, attention to professional service firms, such as law firms, which may offer expertise to these associations or to individuals in need (Haivas, Hofmans, and Pepermans Reference Haivas, Hofmans and Pepermans2012), and corporate volunteering (Rodell et al. Reference Rodell, Booth, Lynch and Zipay2017). A separate body of literature examines professions, such as law, as having a duty to service (Friedson Reference Friedson1994; Cooper Reference Cooper2012a, Reference Cooper2012b) and endeavors to identify factors that promote volunteering of service (‘pro bono’) (Granfield and Veliz Reference Granfield and Veliz2009; Boutcher Reference Boutcher2010). Curiously, the rich body of research on altruism “rarely figures into discussions of lawyers’ pro bono activity” (Rhode Reference Rhode2003, 414). Yet, it seems important that we understand how bar associations and lawyers foster altruism as part of their professional mandate and how organizational environments shape the nature and extent of altruism among lawyers.

This paper strives to address these various gaps in the study of altruism through three strategies. First, we draw from the literature on altruism across psychology, sociology and economics to develop an integrated framework of altruism. Second, we juxtapose studies of altruism on the one hand, with research on lawyers’ pro bono work, on the other. The two areas of study are related, but they have generally progressed without much regard for each other. Bringing them together allows us to think about altruism in the context of professions in a new way. Most notably, the pro bono literature suggests that organizational context has a powerful impact and yet workplace influences have been largely ignored in studies of volunteering (Wilson Reference Wilson2000; Healy Reference Healy2004; Haivas, Hofmans, and Pepermans Reference Haivas, Hofmans and Pepermans2012). Third, we leverage new insights from a mixed methods approach to the study of altruism. We draw on in-depth interviews with lawyers, legal educators, and pro bono leaders to gain better traction on the motivations that drive volunteering among professionals and the organizational parameters that funnel volunteering efforts. We then assess our theoretical understanding of altruism empirically using a survey of legal professionals that incorporates innovative measures of cultural norms of altruism, community civic engagement, and political legal action. Our study contributes an improved understanding of the link between individual and organizational dimensions of altruism in the context of lawyers’ work.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Incorporating three disciplines to explore altruism may seem rather ambitious. However, Paul DiMaggio (Reference DiMaggio1995) argues that “good theory” is multidimensional and that the best theories are hybrids, the product of combining different approaches to theory. Several scholars have recognized the need for a multidisciplinary approach and moved the agenda forward toward an integrated theory of volunteerism. For example, early on, John Wilson and Marc Musick (Reference Wilson and Musick1997a) developed an integrated theory of volunteer work that drew on human, social, and cultural capitals and differentiated between formal and informal volunteering. A few years later, Louis Penner (Reference Penner2002) suggested a theoretical model that combined personal factors (socio-demography, personality, and motivations) and situational and social factors to explain volunteering. Lesley Hustinx, Ram Cnaan, and Femida Handy (Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010) included in their framework a “volunteer ecology” with different “nested systems” in an effort to explore how volunteer activities are embedded in interpersonal relationships and within programs and broader societal structures. More recently, Mihaela Kelemen, Anita Mangan, and Susan Moffatt (Reference Kelemen, Mangan and Moffat2017) have suggested a typology of four types of volunteering work: altruistic, instrumental, militant, and forced (or “voluntolding”) that are linked to multiple motivations, incorporating both individualist and collectivist agendas. We build on these initial forays into theory integration and extract elements from psychology, sociology, and economics—three disciplines that have been at the forefront of advancing research on altruism. We begin by identifying central concepts rooted in these three disciplines.

Psychology and the Role of Personality Traits and the Quest for Meaning

Psychological research on altruism focuses on personality traits, including self-efficacy, inner locus of control, extraversion, self-confidence, emotional stability, empathetic concern, perspective taking, strong morality, positive self-esteem, and psychological sense of community (Eisenberg Reference Eisenberg1986; Bussell and Forbes Reference Bussell and Forbes2002; Haski-Leventhal, Ben-Arieh, and Melton Reference Haski-Leventhal, Ben-Arieh and Melton2008; Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009; Bekkers Reference Bekkers2010; Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Wilson Reference Wilson2012; Kee et al. Reference Kee and Chunxiao Li2018). These personality traits are stable dispositions to act in a certain way, regardless of the situation. As René Bekkers (Reference Bekkers2004, 28) notes, “[e]ven when the choice situation involves no material or social incentives, there are still people who seem to have an eye for the ‘other(s)’ in a social dilemma.” Therefore, knowing about an individual’s personality enables us to anticipate whether he or she will be inclined to volunteer (Musick and Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2008). The most important personality trait in this respect appears to be empathy (Bekkers Reference Bekkers2005, Reference Bekkers2010; Batson Reference Batson2022; Mitani Reference Mitani2014). Empathy means “our sympathetic, compassionate, tender feelings for another, especially another in distress” (Batson and Shaw Reference Batson and Shaw1991, 114). Empathy toward others encourages one to take an impartial point of view and to place each other on an equal plain (Kolm Reference Kolm2006b). Some researchers suggest that there is a pro-social personality (Allen and Rushton Reference Allen and Rushton1983) or altruistic inclination (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhang, Li and Xie2019). For example, Penner’s (Reference Penner2002) pro-social personality model highlights the relevance of other-oriented empathy and helpfulness as precursors to volunteering. Studies consistently show that self-reported pro-social motivation is strongly related to volunteering (Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009; Aydinli et al. Reference Aydinli, Michael Bender, van De Vijver, Cemalcilar, Chong and Yue2016). In addition, psychologists observe that some people have a strong desire for meaningful work (Dwyer et al. Reference Dwyer, Bono, Snyder, Nov and Berson2013). The sense of meaningfulness derived from volunteering is an intrinsic motivation that guides subsequent behavior. Therefore, jobs that are less meaningful may stimulate employees to increase their volunteering involvements in an effort to gain a desired sense of meaning in life. In this way, volunteering compensates for a deficit in the workplace (Rodell Reference Rodell2013).

It is important to note that psychologists studying altruism acknowledge factors beyond personality traits or dispositions, including the importance of community and social conditions. For example, Seymour Sarason (Reference Sarason1974, 1) has noted that altruism may be influenced by the psychological sense of community—a “sense that one belongs in and is meaningfully a part of the larger collectivity.” An enhanced sense of community encourages trust and generates a feeling of belonging among community members (Omoto and Snyder Reference Omoto and Snyder2002; Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009). Furthermore, Bekkers (Reference Bekkers2004) notes that volunteering is clearly related to social conditions. For example, psychological differences have a major impact in “weak situations”—that is, in social contexts that do not involve clear-cut normative expectations on how to behave and when the behavior costs little time and money (Lissek, Pine, and Grillon Reference Lissek, Pine and Grillon2006). And, finally, Bronfenbrenner (Reference Bronfenbrenner1960) has lamented the “vanishing impact” of psychological variables when socioeconomic characteristics were entered into regression analyses. These studies encourage us to explore the influence of community and broader social conditions. We turn next to sociology to better understand the role of collective norms and social relationships.

Sociology and the Role of Collective Norms and Social Relationships

Sociologists explore altruism through an emphasis on one of two perspectives: culture and social norms versus structural and network dynamics. The cultural perspective emphasizes social norms rooted in groups and the internalization of values by members of the group (Durkheim [Reference Durkheim and Cosman1912] 2001; Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009). From this cultural or “normative” perspective, altruistic behavior is an “expression of the solidarity that comes from adherence to a set of corporate obligations. The obligations, or norms, are learned in the same way that other norms are learned, informally through family and friends, and formally through schools, churches, and the workplace” (Janoski and Wilson Reference Janoski and Wilson1995, 272). This learning process leads volunteers to have a distinctive ethos, manifested in the belief that people ought to give and help and in a sense of universality (Dekker and Helman Reference Dekker, Helman, Dekker and Halman2003; Reed and Selbee Reference Reed, Kevin Selbee, Dekker and Helma2003). But volunteering is also a fundamental expression of community belonging and contributes to individuals’ social integration (Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). By following these social norms, people engage in a form of “dutiful altruism” (Schokkaert Reference Schokkaert2006, 133).

Consistent with a cultural perspective, religious affiliation is related to volunteering (Toppe and Kirsch Reference Toppe and Kirsch2003). Religious affiliation increases a sense of community and a culture of benevolence, promoting people to help others (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a; Mitani Reference Mitani2014). Most religions promote the principle of helping others and teach values such as altruism and giving (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2012; Yeung Reference Yeung2018). Numerous studies have documented a positive relationship between various measures of religion as an independent variable and civic outcomes such as philanthropic giving, community group membership, and volunteering (Dekker and Helman Reference Dekker, Helman, Dekker and Halman2003; Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2004; Lam Reference Lam2006; Lim and MacGregor Reference Lim and Ann MacGregor2012). Moreover, evidence from a variety of surveys conducted in different times and places overwhelmingly suggests that religious individuals are more active volunteers and community participants than their secular counterparts (Loveland et al. Reference Loveland, David Sikkink and Radcliff2005; Lam Reference Lam2006; Taniguchi and Thomas Reference Taniguchi and Thomas2011; van Tienen et al. Reference Van Tienen, Scheepers, Reitsma and Schilderman2011).

In contrast, a structural perspective contends that whether or not people will volunteer depends on the network of social relationships in which they are embedded (Abascal Reference Abascal2015; Baldassarri Reference Baldassarri2015). This perspective sees volunteering as essentially a social phenomenon that involves patterns of social relationships and interactions among individuals, groups, and associations (Halsall, Cook, and Wankhade Reference Halsall, Cook and Wankhade2016). Social contacts encourage volunteerism by direct request or by setting an example (Wilson Reference Wilson2000). Therefore, people who are politically involved (D. Smith Reference Smith1994) and attend church and other organizations (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2004) build social ties that encourage volunteering. In short, voluntary action is contingent on the degree of social integration of the individual into society. This approach leads us to expect that employed people would be more active than unemployed, married people more active than single, parents more active than the childless individuals, and so on (Janoski and Wilson Reference Janoski and Wilson1995).

Research confirms these patterns. One’s level of education is positively related to volunteering (De León and Fuertes Reference León, Celeste Dàvila and Chacón Fuertes2007; Gil-Lacruz and Marchuello Reference Gil-Lacruz and Marcuello2013; Son and Wilson Reference Son and Wilson2017). People with higher education have a stronger sense of civic responsibility (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997a), well-developed communication skills, and the ability to empathize with people in need (Rosenthal, Feiring, and Lewis Reference Rosenthal, Feiring and Lewis1998). Also, people with greater socioeconomic resources—both income and occupational status—tend to volunteer more (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998; Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Mitani Reference Mitani2014). Married people are more likely to volunteer than single people (Wilson Reference Wilson2000). Meanwhile, the presence of children determines the type of volunteer work: having children encourages volunteer work that is helping community-oriented groups and children’s sports and activities; however, having children discourages volunteering with professional associations and unions (Janoski and Wilson Reference Janoski and Wilson1995; Wilson Reference Wilson2000).

Other demographic variables are also noteworthy. Women are slightly more likely to volunteer than males (Wilson Reference Wilson2000), though fully employed women spend less time volunteering because of the conflict between work, household, and family responsibilities (Fyall and Gazley Reference Fyall and Gazley2015). Volunteering rises in middle age (Wilson Reference Wilson2000). White people volunteer more often than African Americans (Bryant et al. Reference Bryant, Kang and Tax2003). Human capital theory explains this racial difference by pointing to lower levels of education, income, and occupational status among African Americans. Consistent with this explanation, racial differences in volunteering disappear after taking into account education, income, and occupational status (Rooney et al. Reference Rooney, Mesch, Chin and Steinberg2005).Footnote 4 In this way, sociological explanations of the relationship between socio-demographics and volunteering hint at the importance of economic factors such as human capital and rational choice. We examine economic perspectives on altruism and volunteering in the following section.

Economics and the Role of Exchange, Reciprocity, and Skill Acquisition

Economists examine altruism through the lens of rational choice and exchange theories. The decision to volunteer is based on a rational weighing of its costs and benefits (Wilson Reference Wilson2000; Kolm Reference Kolm2006a, 2006b; Mantell Reference Mantell2018). This leads to two different predictions. Some rational choice theorists assume that volunteer hours are inversely related to wages because opportunity costs rise as pay rises (Prouteau and Wolff Reference Prouteau and Wolff2004). But others predict that voluntary action is driven, or made possible, by socioeconomic interests and resources. People in higher status occupations and with higher incomes are more active in voluntary associations (Pearce Reference Pearce1993; Janoski and Wilson Reference Janoski and Wilson1995). Their socioeconomic conditions enable them to volunteer (Musick and Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2008; Mitani Reference Mitani2014). Although these hypotheses, rooted in opportunity costs and resources, are opposing, a key element is the notion of exchange (Piatak Reference Piatak2016). The underlying assumption is that actors will not contribute goods and services to others unless they profit from the exchange (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1999; Wilson Reference Wilson2000). Fundamentally, altruism is motivated by reciprocity (Schokkaert Reference Schokkaert2006, 132); by improving the condition of someone else, it also enhances the utility of the one who acts (Mantell Reference Mantell2018).

What is the nature of exchange or reciprocity when it comes to volunteering? Volunteers profit from their participation when they receive training and acquire skills that enhance their human capital (Walsh and Borkowski Reference Walsh and Borkowski2006; Haivas, Hofmans, and Pepermans Reference Haivas, Hofmans and Pepermans2012; Dwyer et al. Reference Dwyer, Bono, Snyder, Nov and Berson2013). Volunteering also affords networking opportunities, access to industry information (Dalton and Dignam Reference Dalton and Digman2007; Piatak Reference Piatak2016), status, marketing contacts, and representation (Binder and Freytag Reference Binder and Freytag2013; Fyall and Gazley Reference Fyall and Gazley2015). From a social exchange point of view (Vantilborgh et al. Reference Vantilborgh, Jemima Bidee, Willems, Huybrechts and Jegers2012), social connections acquired during volunteering compensate for the lack of financial rewards by providing an alternative return on investment for the volunteer (Clary, Snyder, and Strukas Reference Clary, Snyder and Strukas1996). Secondary benefits include access to mentors and role models (Dansky Reference Dansky1996) and opportunities to take on leadership in the association, cultivating skills that will advance one’s career (Fyall and Gazley Reference Fyall and Gazley2015). Volunteering may even serve as “bridge positions” to paid employment (V. Smith Reference Smith2010, 292). For example, Christopher Spera and colleagues (Reference Spera, Ghertner, Nerino and DiThommasso2013) find people are more likely to secure employment the year after starting to volunteer.

Volunteers also receive personal benefits (Snyder and Omoto Reference Snyder and Omoto2008; Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). For example, helping others provides rewards such as increased prestige, favorable reputation, and positive attitude from significant others (Andreoni Reference Andreoni1995). A “consumption” or “private benefits” model emphasizes personal benefits such as the joy or “warm glow” that volunteers receive from volunteering (Clary et al. Reference Clary, Mark Snyder, Ridge, Stukas, Haugen and Miene1998; Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). In addition, altruistic acts such as volunteering may be meaningful (Healy Reference Healy2004) and produce mental and physical health, life satisfaction, self-efficacy, social support, and trust (Musick and Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2003; Lum and Lightfoot Reference Lum and Lightfoot2005; Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009; Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). So, while economic approaches emphasize exchange, economists acknowledge that reciprocity is not necessary: giving can aim to show or prove commitment or enjoyment at the very process of giving (Kolm Reference Kolm2006b, 382).

Thus far, we have traced contrasting disciplinary approaches to the study of altruism with reference to volunteering. Yet volunteering time and energy with a charity association (for example, United Way, World Vision) or a local organization (for example, the Young Men’s Christian Association, shelters for homeless) may be different than volunteering services in the context of one’s occupation or profession. We turn next to explore volunteering (for example, public service) that occurs in the course of doing professional work, with the example of lawyers.

LAWYERS’ PRO BONO

A central feature of the professions is public service (Friedson Reference Friedson1994). For lawyers, public service takes the form of “pro bono”, meaning “for the public good” (Erichson Reference Erichson2004, 2109). This term describes professional work undertaken voluntarily to provide free services to persons of limited means or to clients seeking to advance the public interest (Cummings and Sandefur Reference Cummings and Sandefur2013, 87; McColl-Kennedy et al. Reference McColl-Kennedy, Patterson, Brady, Cheung and Nguyen2015, 429). A range of legal services are provided pro bono, including legal advice to those of limited means, court representation, legal assistance to nonprofit organizations, community legal education, efforts to improve the legal system, and other legal work, such as the drafting of contracts (Rix Reference Rix2003; Downey Reference Downey2010). Although Canadian law societies and the American Bar Association have rejected the notion of mandatory pro bono (Woolley Reference Woolley2008), accreditation standards require that law schools encourage students and faculty to participate in pro bono work (Wizner and Aiken Reference Wizner and Aiken2004). This encouragement may be seeded in mandatory professional responsibility courses and the requirement of supervised pro bono (Granfield Reference Granfield2007a; Colbert Reference Colbert2011). Law school pro bono programs aim to cultivate commitment among law graduates to continue pro bono as an integral aspect of their practice (Hoffman Reference Hoffman2007), though we know less about these programs’ long-term impact (Granfield and Veliz Reference Granfield and Veliz2009; Dignan, Grimes and Parker Reference Dignan, Grimes and Parker2017).

Overall, the literature on lawyers’ pro bono work closely parallels the broader social science research on altruism. Consistent with psychological studies of altruism and pro-social behavior, studies of pro bono work emphasize the role of personality traits (Bartlett and Taylor Reference Bartlett and Taylor2016; Rhode Reference Rhode2004a) and individual lawyers’ quest for meaningful work (Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer and Garth2009; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2009) as motivators for participation. Parallel to sociological research on altruism, studies of pro bono work observe the influence of community and social relationships (for example, bar associations and law schools) in cultivating commitment to pro bono service (Rhode Reference Rhode2003, Reference Rhode2004b; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2004; Heinz et al. Reference Heinz, Nelson, Sandefur and Laumann2005; Granfield Reference Granfield2007b). Finally, in tandem with economic research on altruism, studies of pro bono highlight benefits to lawyers in terms of professional boundary maintenance (Sandefur Reference Sandefur2007; Rhode Reference Rhode2009; Juergens and Galatowitsch Reference Juergens and Galatowitsch2016), skill acquisition and client contact (Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels and Martin2009; Granfield and Veliz Reference Granfield and Veliz2009; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2009; Traum Reference Traum2014; McColl-Kennedy et al. Reference McColl-Kennedy, Patterson, Brady, Cheung and Nguyen2015), and law firm gains of recruitment, training, and retention of legal talent (Bartlett and Taylor Reference Bartlett and Taylor2016; Boutcher Reference Boutcher, Estreicher and Radice2016).

Yet, studies of pro bono work diverge from the broader research on altruism in one key respect: their close attention to the role of organizational settings. Studies of volunteering tend to highlight the organizational efforts of charities and community organizations in asking for help—that is, soliciting for donations or volunteers (Healy Reference Healy2004; Lacetera, Macis, and Slonim Reference Lacetera, Macis and Slonim2014). However, organizations matter in a different way for the provision of professional services. The pro bono literature focuses squarely on the work environments of lawyers that shape opportunities for, and barriers to, pro bono service (Granfield and Veliz Reference Granfield and Veliz2009; Boutcher Reference Boutcher2010; Kay and Granfield Reference Kay and Granfield2022). We direct our attention next to identify core organizational dimensions that nurture altruistic behavior.

Organizations

The organizational contexts in which lawyers work are central factors shaping the meaning and action of pro bono behavior (Granfield Reference Granfield2007b; Cummings and Sandefur Reference Cummings and Sandefur2013). For example, in-house counsel lawyers define the role of pro bono in their lives in ways that diverge significantly from other lawyers (Hackett Reference Hackett2002; Granfield Reference Granfield2007b). As Robert Granfield (Reference Granfield2007b, 140) notes, “[c]orporate counsel lawyers often use nonlegal volunteer opportunities as a way to further strengthen their relationships with their clients by offering volunteer services that reflect very publicly and positively on the image of the company as a good citizen.” For lawyers working in small firms and solo practice, pro bono work is both routine (Anderson and Renouf Reference Anderson and Renouf2003) and a strategy in recruiting clients (Mather, McEwen, and Maiman Reference Mather, McEwen and Maiman2001). In these contexts, legal work can be deliberately undertaken as pro bono from the start or as hours deemed pro bono when clients prove unable to pay (Levin Reference Levin2009).

In larger law firms, pro bono activity has shifted from a personal responsibility of individual lawyers to the collective responsibility of the firm (Cummings Reference Cummings2004; Epstein Reference Epstein2009; Boutcher Reference Boutcher2013). This is reflected in the fact that, increasingly, pro bono is managed through policies that advance the firm’s interests (Granfield and Mather Reference Granfield and Mather2009b). Pro bono is celebrated by law firm leaders as an important mechanism to train and diversify the skills of young associates (Epstein Reference Epstein2002) and to improve the retention of new recruits (Lardent Reference Lardent2000; Granfield Reference Granfield2007a). Many large firms now hire coordinators to oversee their firm-wide pro bono practices (Boutcher Reference Boutcher2010; Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010; Juergens and Galatovisch Reference Juergens and Galatowitsch2016) and give associates credit toward their billable hours for any pro bono work done during the year (Boutcher Reference Boutcher2010; Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010; Cummings and Sandefur Reference Cummings and Sandefur2013; Maguire, Shearer, and Field Reference Maguire, Shearer and Field2014). Some firms appoint dedicated pro bono lawyers and use the secondment of staff to select causes or organizations (Maguire, Shearer, and Field Reference Maguire, Shearer and Field2014). As a result, large law firms have a “community of pro bono practice where they share ideas and definitions, structural approaches and resources. … Conversely, small firm and sole practitioners do not have the time or access to the same community of practice nor the same resources or incentives to undertake it” (Bartlett and Taylor Reference Bartlett and Taylor2016, 279).

Empirical research studies demonstrate the importance of these organizational features in promoting pro bono work within firms (Boutcher Reference Boutcher2017). For example, Deborah Rhode’s (Reference Rhode2005) survey of American lawyers highlights the importance of employer practices in promoting or restricting pro bono. Steven Boutcher’s (Reference Boutcher2010) analysis of a later American Bar Association survey of American lawyers echoes these results. He finds that significant motivational factors are cultural: satisfaction/duty (70 percent) or the needs of the poor (43 percent). Discouraging factors are structural: time (69 percent), billable hours (15 percent), or lack of experience (15 percent) (145). In an analysis of large law firms in the United States, Boutcher (Reference Boutcher, Estreicher and Radice2016) finds that pro bono policies, such as the presence of a coordinator and having a formal written policy, positively affect how much time a firm commits to pro bono. Thus, pro bono does not emerge wholly from individual personality traits. Rather, the workplace environment sets the conditions that make volunteer work feasible (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1998; Granfield Reference Granfield2007b). This organizational framing builds on the prior disciplinary perspectives by drawing our attention to incentives for altruism nested in the workplace (Dur and Tichem Reference Dur and Tichem2015). We incorporate these organizational dimensions into our theoretical approach.

METHODS

The Canadian Context

Our study is set in the province of Ontario, Canada. Most research on pro bono legal work has been conducted in the United States (Rhode Reference Rhode2003; Cummings Reference Cummings2004; Granfield Reference Granfield2007a; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2007; Epstein Reference Epstein2009; Rhode and Cummings Reference Rhode and Cummings2017; Leal, Paik, and Boutcher Reference Leal, Paik and Boutcher2019), Australia (Parker Reference Parker2001; Mcleay Reference Mcleay2008; Maguire, Shearer, and Field Reference Maguire, Shearer and Field2014), and England (Boone and Whyte Reference Boon and Whyte2015). Yet Canada offers an intriguing setting within which to examine lawyers’ pro bono work. Similar to the United States, Canada faces a gap in access to justice, though the context is different. In an effort to address unmet legal needs, Canada has Legal Aid, a government program that helps people of low income to receive legal representation and advice. Although publicly funded by both provincial and federal levels of government, Legal Aid Ontario is an independent, nonprofit corporation that provides legal aid services in Ontario.Footnote 5 Legal aid is most often available for more serious criminal matters as well as for charges laid under the Youth Criminal Justice Act.Footnote 6 Financial eligibility requirements for legal aid remain set at extremely low levels, and the range of services that are prioritized, owing to large caseloads, exclude many areas of the civil justice system (Trebilcock, Duggan, and Sossin Reference Trebilcock, Duggan, Sossin, Trebilcock, Duggan and Sossin2018). Various efforts have been made to attempt to reform Legal Aid Ontario (Zemans and Monahan Reference Zemans and Monahan1997; Mossman Reference Mossman1998), however, an acute lack of access to civil justice for lower- and middle-income earners persists (Trebilcock, Duggan, and Sossin Reference Trebilcock, Duggan, Sossin, Trebilcock, Duggan and Sossin2018). In recent years, the system has faced significant funding cuts, further straining the system (Churchman and Stein Reference Churchman and Stein2019; Neve Reference Neve2019).

Other methods of obtaining legal services have been advanced. For example, the Ontario government introduced a paralegal regulation in 2007 with the promise that this regulation would increase access to justice by ensuring paralegal competence, including the choice of qualified legal service providers and making legal services more affordable.Footnote 7 The Law Society of Ontario is now responsible for the licensing and regulation of over fifty-five thousand lawyers and nine thousand paralegals.Footnote 8 Pro bono work by lawyers offers a further path toward filling the justice gap. Organizations beyond private law firms serve to promote and coordinate pro bono efforts by lawyers. For example, Pro Bono Law Ontario (PBLO) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) that works to bridge the gap between lawyers willing to donate their services and low-income people whose legal problems are not covered by Legal Aid. PBLO connects volunteer lawyers to pro bono projects across Ontario.Footnote 9 Also, for over twenty years, Pro Bono Students Canada has offered law students community placement projects where law students provide free legal services to local organizations.Footnote 10

Thus, the Canadian case shares with the United States a gap in justice, with a dire lack of access to civil justice for lower- and even middle-income earners. A staggering number of individuals must navigate a complex civil justice system without legal assistance. For both nations, there are rising feelings of alienation from the justice system (Albiston, Li, and Nielsen Reference Albiston, Li and Beth Nielsen2017; Trebilcock, Duggan, and Sossin Reference Trebilcock, Duggan, Sossin, Trebilcock, Duggan and Sossin2018). Ontario diverges from the United States in its approach to the justice gap through Legal Aid, licensed paralegals, and pro bono work that is promoted and coordinated both within private law firms and by NGOs.

Beyond efforts to address the gap in access to justice, other differences are noteworthy between the two countries. First, the market for pro bono service is vastly larger in the United States (with a population that is 8.8 times that of Canada). Demand may be greater in the United States where various measures of litigation rates appear higher (Ramseyer and Rasmusen Reference Mark and Rasmusen2010) and a sizeable gap in the provision of legal services has been well documented (Sandefur Reference Sandefur2009; Hadfield Reference Hadfield2010). Canada’s social welfare programs—including, for example, social assistance, Medicare, employment insurance, and the guaranteed income supplement—may offer a stronger buffer against extreme poverty, and this may narrow the justice gap and lessen demand for pro bono work in Canada. The two countries may also differ culturally with reference to volunteerism. One could argue that a distinct ethos surrounding voluntarism exists in Canada that potentially shapes lawyers’ proclivity toward pro bono service. For example, in 2018, 41 percent of adult Canadians volunteered for charities, nonprofits, and community organizations compared with 30 percent of adult Americans. In addition, in the same year, 73 percent of adult Canadians volunteered informally (to help friends, neighbors, and relatives) compared with 51 percent of adult Americans (Corporation for National and Community Service 2018; Hahmann, Du Plessis, and Fournier-Savard Reference Hahmann, Du Plessis and Fournier-Savard2020). However, reports that examine charitable donations rank Americans ahead of Canadians (Charities Aid Foundation 2019). In the final analysis, much is to be gleaned from a study of pro bono in the Canadian context, both for the challenges shared by US and Canadian justice systems as well as for the differences in terms of institutional-run legal services (that is, law societies, NGOs, legal aid clinics), government social assistance, and cultures of volunteering.

Interviews

Our study uses a sequential mixed methods approach (Tashakkori and Teddlie Reference Tashakkori and Teddlie2010). We conducted interviews in the first stage to delve into the motives for pro bono legal work and to better understand the role of organizational conditions in shaping pro bono involvement. Specifically, our interview data lend greater precision to the nature of collective norms (suggested by sociology), investments and returns (suggested by economics), and workplace policies and structures (suggested by the pro bono literature) that seed and cultivate volunteering among legal professionals. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with lawyers in Ontario (primarily in Toronto and Ottawa) as well as with lawyers located in other Canadian provinces with ties to Toronto-based law firms. These interviews were conducted between September and December 2010. A total of thirty in-depth interviews were conducted. Lawyers participating in these interviews were selected on a purposive sampling basis in relation to the respondent’s involvement in pro bono. Several lawyers were identified through a list of attorneys maintained by a pro bono legal assistance center located in Ottawa. Several other lawyers were identified through law firm pro bono programs. Other lawyers associated with Pro Bono Law Ontario, a NGO that connects lawyers to pro bono projects across Ontario, were also interviewed. Finally, staff members of the Canadian Bar Association as well as law faculty in Toronto and Ottawa offering pro bono services were interviewed. Interviews ranged from sixty to ninety minutes in length and explored numerous aspects of lawyers’ pro bono practice, including motivations for participating, types of pro bono practice, personal and organizational benefits associated with pro bono, and limitations placed on their pro bono practice. In the second stage, we drew on the qualitative results to develop questionnaire items that tap core theoretical concepts in a survey of over eight hundred lawyers. In the following discussion, we highlight four qualitative themes, each drawing attention to the importance of organizational context. These themes refine our understanding of the impetus for volunteering and guide our subsequent quantitative analysis.

The first theme is the role that normative expectations—cultivated within organizational settings such as law firms—play in motivating pro bono work. It appears that, in the context of lawyering, the collective norm associated with pro bono often translates into a norm of giving back to society. As one lawyer from a law firm in Ottawa remarked, “pro bono is probably the best way for lawyers to give back to society. Lawyers are generally paid quite well and we have an obligation to give back. We need to give back to society because society gives us so much power and possibilities. We have to see who we can help because we have so many privileges.” A politically active lawyer in Toronto who had worked several years in a large law firm commented on how her social activist orientation motivated her to do pro bono: “A lot of pro bono work is done as part of and/or in participation with a social movement or a movement for change. That was my approach. I did a lot of that work at (law firm) and I have done a lot of that work since. I was involved in the work on establishing the guarantees in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Other work I did was for one of the premier women’s rights litigation groups in the country.”Footnote 11 For another lawyer, pro bono was an expression of her broader collectivist commitment to social change and social justice. She summed up her view of pro bono in this way: “For me, I really think pro bono is associated with social justice, it does provide some access to justice. For instance, I’ve been involved recently in a pro bono file with another lawyer around issues of prostitution. I find these cases because I’m involved in my community as a social movement activist.”

A second theme to emerge was the role that law firms, especially large law firms, play through the provision of firm minimal expectations for pro bono service. Yet we also discovered that it is possible that lawyers who experience time constraints in small- to medium-size firms without minimal pro bono hour expectations find different pro bono opportunities that do not demand considerable time commitments. A partner at a medium-size Toronto law firm that is actively involved in international work related to food insecurity commented:

Our firm is committed to international support work and efforts to “feed hungry people.” The Feed the Hungry program is for local people who have no shelter or food and they serve the homeless. We just served Thanksgiving dinner to homeless population here in Toronto through this initiative in fact I’m going over tonight to do some serving. Forty people come in and it was lovely. All my associates came over with me, and those are really the two programs that we focus on. The other aspect of this is it’s too young—it has its origins ten years ago, and our associates are all young lawyers. There are ten of us now; six of them under thirty-five. I want to instill upon them an early age that they give back. I tend to prefer not to do legal work pro bono. I do enough legal work—sixty hours a week. … I am fairly focused on something very particular. This is not really direct service in the strict pro bono sense. In fact, I think pro bono in the traditional sense is fairly limited. We’re also a small shop, and we can’t have people taking on time-consuming litigation cases. I did a pro bono case in my second year of law practice several years ago that went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. It was a big constitutional case—a very difficult piece of litigation—that took several years. It’s a very difficult thing to take the traditional pro bono case in a small firm like ours. It costs a lot of money. The pro bono work that we do is more pure because we are not doing it to receive anything in return. So, the work that we do I think is pro bono. I would define as pro bono, but it’s meant to be the purest form of pro bono.

A third theme that surfaced was that economic, training, and client development benefits associated with pro bono are especially salient to work in large urban law firms. One senior partner of a Toronto-based firm explained the value of pro bono in the following way:

As a big law firm most of our cases are very big, most lawyers only see a piece of the file especially the young lawyers. They might do a task being delegated by the lawyers and sometimes it’s hard to see what the impact is been of what you are doing. We hear this a lot. However, with pro bono you can give a young lawyer a case where they get experience, and I can handle it from the beginning to the end and see some impact. Pro bono gives a lot of client contact and helps a young lawyer manage the relationship with the client. This will help develop the skills of how to manage cases with any business client. Skills like listening, understanding, understanding the business of your client, following your client. Sometimes this is hard because many pro bono clients have a humanitarian or social mission, and when you’re practicing law in a big skyscraper, we’re sort of removed. So, it gives our lawyers another perspective, and I often tell them at the first meeting just go meet them to see how it’s being managed, who is the client, who are the people that they’re helping, and I should spend a half a day there where they’ll learn more about the client then in a dozen meetings. Developing a trustful relationship with the client with some people is easy, for others it’s harder. All this is important because what they learned doing pro bono though they bring into their relationships with paying clients.

Furthermore, the business motive in large corporate law firms for doing pro bono is directly tied to client development. A Toronto lawyer illustrated how pro bono can be used to generate business:

We also now have to bid for a lot of our work, and there are questions about the firm’s social responsibility commitments that we have to respond to. Pro bono is part of this. We need to have real experiences and accomplishments to demonstrate our corporate social responsibility. We need to have answers to those questions. This is one of the reasons why we can justify doing pro bono and keep increasing it. Our firm’s commitment to corporate social responsibility is one of the questions we are now receiving from our clients. Pro bono is a way to engage in business development and generate clients.

Another lawyer in a large Toronto law firm was especially pointed in his description of the financial and client development purposes rooted in pro bono: “Let’s face it; it’s not only because pro bono is the right thing to do. The marketing benefits of pro bono advertising to your paying clients and to making yourself part of their community for the purpose of client recruitment.”

Finally, a fourth theme expressed by lawyers in our interviews, across organizational settings, was a genuine concern for the current crisis in terms of poor people’s access to justice. The pro bono movement in Canada has long been tied to the issue of access to justice (Granfield and Kay Reference Granfield, Kay, Scott and Trubek2022). As one attorney who is associated with a pro bono NGO commented, “there’s a crisis in access to justice in Canada, so at least in our minds, in my mind, pro bono is a partial answer to that problem. And, in effect if the crisis were to cease, there’d be no need for pro bono. I’m sure that lawyers would do things on a free basis for people that need them, but pro bono wouldn’t be necessary. The real focus for us is addressing the crisis of access to justice, not access to justice.” Even attorneys employed at large law firms reported engaging in pro bono activities to assist the poor. One attorney from a large law firm described his firm’s view of the anti-poverty pro bono work he performs: “At (large Toronto law firm), we don’t have a strong pro bono policy. We never have, and the justification behind that is that we don’t need it because we have a pro bono tradition. I do a lot of anti-poverty work, and it’s not like the firm has ever objected.”

These four themes inform our quantitative analysis of a large-scale survey of lawyers that follows. In this second stage of analysis, we focus attention on the design of innovative survey measures that capture collectivist norms—specifically, community-civil engagement and political-legal action—that lawyers discussed at length during interviews. These new measures extend sociological knowledge of cultural norms of giving. In addition, we consider several organizational factors, including pro bono minimums, caps, and managers, in our statistical analysis to examine how law firms concretely shape opportunities for pro bono. The economic incentives and clientele recruitment dimensions that surfaced in the interviews are also incorporated into our statistical models. Here, our qualitative inquiry advances economic research into the forms of reciprocity and returns of giving that are specific to professional work. Finally, our interviews with lawyers led us to consider the consequences of pro bono work for agencies and people in need of cost-free legal services, particularly economically disadvantaged people seeking access to justice.

Social Survey Data

In the second stage of our study, we analyze data from a large-scale survey of lawyers in Ontario, Canada. Ontario is an ideal setting in which to study pro bono service because the province is home to the largest proportion of lawyers in the nation (37 percent) (Federation of Law Societies of Canada 2019). Located in Ontario are Toronto and Ottawa—two cities of importance for the practice of law. The headquarters of the country’s largest corporate law firms are based in Toronto, the financial nexus and largest city in Canada. Meanwhile, government lawyers are concentrated in Ottawa, the nation’s capital. There is also considerable diversity of law practice settings scattered in smaller cities and towns across the province. The survey consisted of a stratified simple random sample of lawyers from the membership records of the Law Society of Ontario. We stratified the sample by gender to include equal numbers of men and women called to the Ontario bar between 1990 and 2009. We selected this near twenty-year span to pay close attention to formative career years. These are years where one might expect to see considerable pro bono engagement fostered by law school clinics (Cooper Reference Cooper2012a; Traum Reference Traum2014; Juergens and Galatowitsch Reference Juergens and Galatowitsch2016) and by law firms’ pro bono programs aimed at providing junior lawyers with skill development and client contact (Parker Reference Parker2001; Epstein Reference Epstein2002; Rhode Reference Rhode2005; Mcleay Reference Mcleay2008; Downey Reference Downey2010).

We conducted our survey in September 2009. We mailed questionnaires directly to respondents’ places of employment. The survey, with two reminders, received a 47 percent response rate (N = 1,270), which was a favorable rate of response, consistent with recent surveys of lawyers in North America (Dinovitzer and Hagan Reference Dinovitzer and Hagan2014; Dinovitzer Reference Dinovitzer2015; Wilkins, Fong, and Dinovitzer Reference Wilkins, Fong and Dinovitzer2015).Footnote 12 In addition, the demographic characteristics of the sample and the distribution across sectors of practice and firm size were consistent with the population data (Law Society of Upper Canada 2009). In our sample, 61 percent of lawyers work in private law practice. Private practitioners are more likely to do pro bono work (63 percent) compared with non-private practice lawyers (that is, lawyers working in government, business, and education) (24 percent) (χ2 = 152.55; p < 0.001). We restrict our sample to lawyers working in private practice where the greatest share of pro bono work takes place (N = 845).

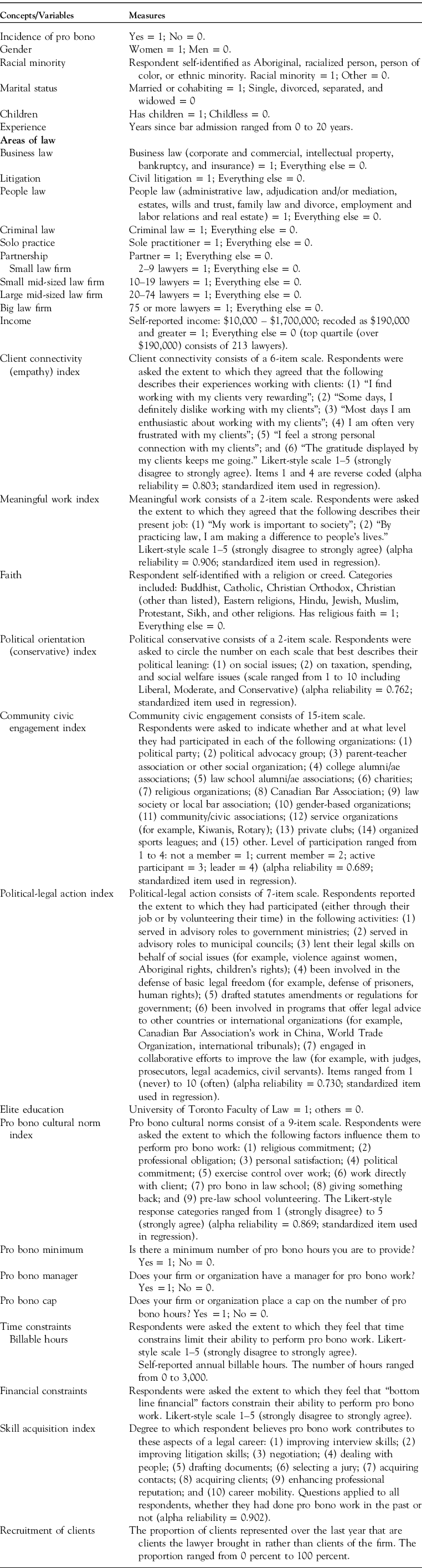

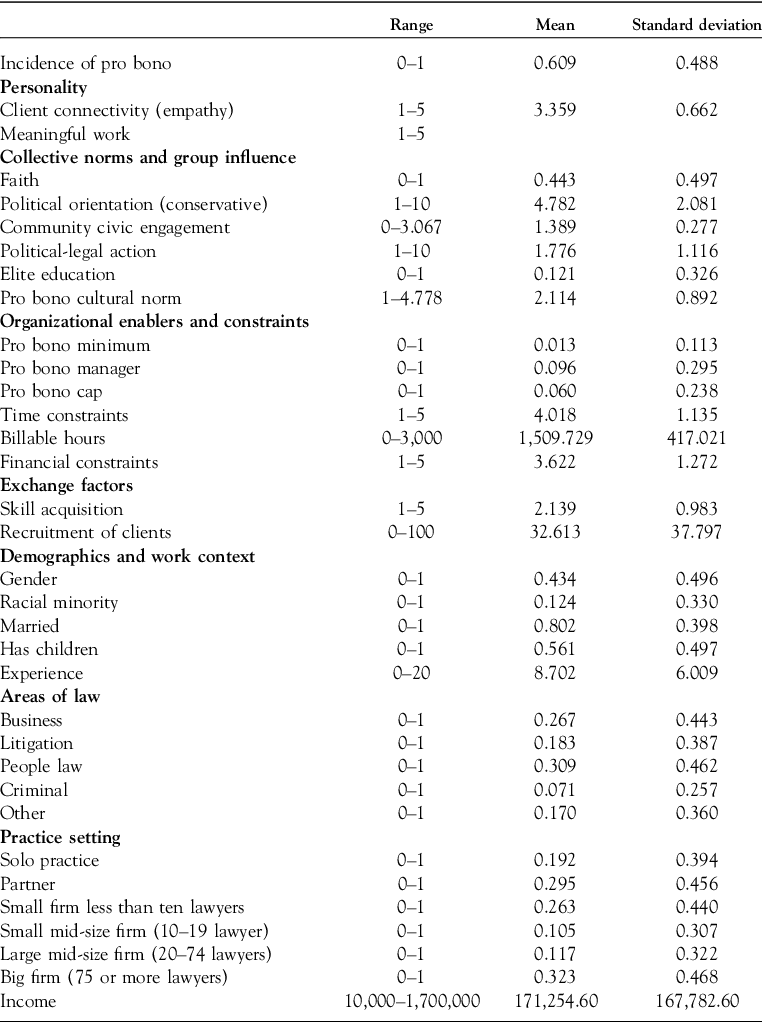

Table 1 provides an overview of the measurement of variables used in our analysis, and Table 2 displays descriptive statistics for these variables. Our dependent variable was the incidence of pro bono work performed in the prior year (that is, whether or not a lawyer engaged in pro bono work during the last twelve months). Pro bono is defined in the survey as “activities undertaken without expectation of fees consisting of the delivery of legal services to persons of limited means or to charitable, religious, civic, community, governmental, and educational organizations.” In our sample of private practitioners, 61 percent reported doing pro bono work during the last year. Our independent variables drew from our interdisciplinary framework, building from internal motivators (personality traits from psychology) to external pressures (collective norms from sociology) and incorporating organizational-level enablers and the constraints of pro bono work (from the pro bono literature) and, finally, exchange factors (from economics). In the section highlighting our results, we highlight several key independent variables.

TABLE 1. Operationalization and measurement of study variables

TABLE 2. Descriptive statistics of study variables, N = 845

Note: Unstandardized scales reported. Standardized scales used in regression analysis.

To assess personality and the quest for meaning, we employed two indices: empathy and meaningful work. We drew on the psychological measures of empathy and benevolence (Haski-Leventhal Reference Haski-Leventhal2009; Fechter Reference Fechter2012) to develop a measure of lawyers’ empathy in terms of their attitude toward clients. To the degree that lawyers feel a strong connection, an appreciation for, and inspiration from their clients, they are more likely to be motivated to provide pro bono time. Our client connectivity index consists of six items that ask lawyers about the extent to which these statements describe their personal connection and enjoyment of working with clients (α = 0.803). We also constructed a meaningful work index based on two items: (1) “my work is important to society” and (2) “by practicing law, I am making a difference to people’s lives” (α = 0.906), adapting measures of meaningful work from a study by Frank Martela and colleagues (Reference Martela, Marcos Gómez, Araya, Bravo and Espejo2021).

To understand collective norms, we drew on a slate of six variables. Faith is a dummy variable measuring whether the respondent self-identified with a religion (thirteen religions were listed, including “other religion not listed”) (see Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2012). Political orientation is a two-item scale that builds on existing measures (Laustsen Reference Laustsen2017). Respondents were asked to circle the number on the scale that best describes their political leaning on (1) social issues and (2) taxation, spending, and social welfare issues (the scale is one to ten, ranging from liberal to conservative) (α = 0.762). Community civic engagement is a scale developed using items derived from a network-based study of social capital and civic engagement conducted by Joonmo Son and Nan Lin (Reference Son and Lin2008). Respondents were asked to indicate whether and at what level they had participated in each of the fifteen organizations. Levels of participation ranged from one to four (1 = not a member; 2 = current member; 3 = active participant; and 4 = leader) (α = 0.689). Political-legal action is a seven-item scale that we designed specifically for this study. Respondents reported the extent to which they had participated (either through their job or by volunteering their time) in the following activities: (1) served in advisory roles to government ministries; (2) served in advisory roles to municipal councils; (3) lent their legal skills on behalf of social issues (for example, violence against women, Aboriginal rights, children’s rights); (4) been involved in the defense of basic legal freedom (for example, the defense of prisoners, human rights); (5) drafted statutes amendments or regulations for government; (6) been involved in programs that offer legal advice to other countries or international organizations (for example, Canadian Bar Association’s work in China, World Trade Organization, international tribunals); (7) engaged in collaborative efforts to improve the law (for example, with judges, prosecutors, legal academics, civil servants). Items were scored from one (never) to ten (often) (α = 0.730).Footnote 13

Elite education is coded as a dummy variable based on the Maclean’s (2013) law school rankings (see also Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer and Garth2009). The ranking employs a combined score of graduate quality (based on elite firm hiring, national reach, Supreme Court clerkships, and faculty hiring) and faculty quality (based on faculty journal citations). This ranking identifies the University of Toronto as elite and provides a scoring of all (common law) law schools in Ontario (coded as University of Toronto = 1, everywhere else = 0).Footnote 14 The University of Toronto law school is also widely regarded among applicants as having the most demanding entry criteria, with the most expensive tuition (double that of several Ontario law schools) and with a reputation as a “feeder school” to the big law firms of Bay Street. Pro bono cultural norm is an index composed of nine items adapted from work by Granfield (Reference Granfield2007a). Respondents were asked to identify the extent to which various factors influence them to do pro bono work. Lawyers did not need to be doing any pro bono to answer the question. The Likert-style response categories ranged from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) (α = 0.869).

Our review or the pro bono literature drew our attention to organizational features that act to enable and/or constrain pro bono involvement. A set minimum of pro bono hours and the provision of a pro bono manager were enablers (Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010), while a pro bono cap (limit) and the lawyer’s claim of time and financial constraints against pro bono participation were constraints (Sandefur Reference Sandefur2007). The first three variables were dummy variables (1 = yes), while the last two variables—time and financial constraints—were composed of Likert-style scales ranging from one to five (strongly disagree to strongly agree). An additional behavioral measure of time constraints—annual billable hours—was included.

We examined economic exchange factors through two variables: skill acquisition and recruitment of clients. Skill acquisition was adapted from an index by Granfield and Philip Veliz (Reference Granfield and Veliz2009) that taps the degree to which the respondent believes pro bono work contributes to: (1) improving interview skills; (2) improving litigation skills; (3) negotiation; (4) dealing with people; (5) drafting documents; (6) selecting a jury; (7) acquiring contacts; (8) acquiring clients; (9) enhancing professional reputation; and (10) career mobility (α = 0.902). The recruitment of clients consists of the proportion of clients represented over the last year that are clients that the lawyer brought in rather than clients of the firm (Kay and Hagan Reference Kay and Hagan2003).

Finally, we incorporated a set of control variables, which included socio-demographic variables: gender, racial minority, marital status, children, and years of experience. Additional controls included work-setting variables: areas of law (business, litigation, people law, and criminal law), practice setting (solo practice and firm size), professional rank (partner status), and income.

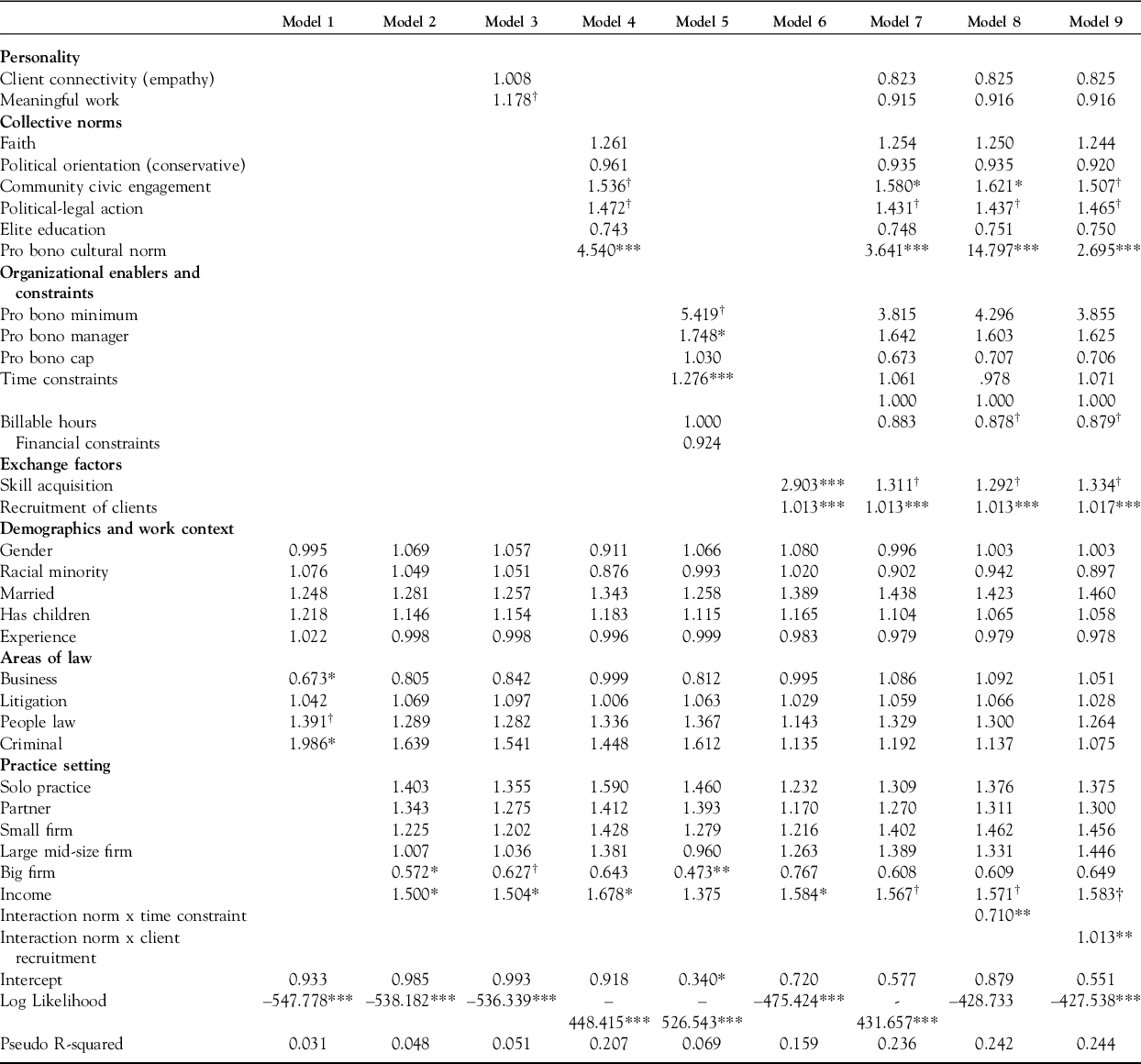

Our integrated framework builds in a series of steps. Using logistic regression, we examine the incidence of pro bono participation. We begin with a baseline model that includes demographics and areas of law. We add to this model practice settings, status, and earning variables. We then layer onto these control variables: personality (Model 3), collective norms (Model 4), organizational enablers and constraints (Model 5), and exchange factors (Model 6). We present a fully integrated model (Model 7), incorporating our full set of variables, and explore conditioning effects (Models 8 and 9).

RESULTS

Our baseline model shows that areas of law are more important than demographic background in explaining lawyers’ likelihood of doing pro bono work (see Model 1; Table 3). Lawyers practicing in the area of business law (that is, corporate commercial, intellectual property, bankruptcy, and insurance) are 33 percent less likely to do pro bono than lawyers working in other areas of law (odds ratio = 0.673, p < 0.05). Meanwhile lawyers practicing criminal law are 99 percent more likely than lawyers in other areas to perform pro bono (odds ratio =1.986; p < 0.05). Lawyers working in the area of people law (that is, family law and divorce, employment, and labor relations) are 39 percent more likely than lawyers working in other areas to take on pro bono work, though the effect is at borderline significance (odds ratio =1.391; p < 0.10). In Model 2, we see that the effects of areas of law fall from statistical significance when we take into account organizational context and income. Lawyers working in big firms (seventy-five or more lawyers) are 43 percent less likely to do pro bono than lawyers working in smaller mid-size firms of ten to nineteen lawyers (odds ratio = 0.572; p < 0.05). Consistent with research on volunteering generally (Hustinx, Cnaan, and Handy Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010), lawyers in the top earnings quartile, are 50 percent more likely to take on pro bono work (odds ratio = 1.500; p < 0.05).

TABLE 3. Logistic regression of personality, collective norms, and organizational and exchange factors on incidence of pro bono (odds ratios displayed) (n = 845)

Notes: † p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 (two-tailed test).

Personality and quest for meaningful work are introduced in Model 3. Interestingly, client connectivity (that is, empathy) has no significant effect on the probability of doing pro bono, but a desire for meaningful work plays a role. Lawyers seeking meaningful work are 18 percent more likely to engage in pro bono service than those without this aspiration, though the effect is marginally significant (odds ratio = 1.178; p < 0.10).

Collective norms, introduced in Model 4, play a powerful role in encouraging pro bono work. Mostly importantly, lawyers who have internalized a strong cultural norm supporting pro bono work are over three times more likely to do pro bono than others (odds ratio = 4.540; p < 0.001). Also, lawyers who are active participants and leaders through community civic engagement are 54 percent more likely to do pro bono (odds ratio = 1.536; p < 0.10). Similarly, lawyers who score high on our political-legal action index are 47 percent more likely to provide pro bono service (odds ratio = 1.472; p < 0.10). The latter two effects are at borderline significance, while a cultural norm encouraging pro bono is a powerful campaigner of pro bono service.

Organizational constraints and enabling factors are introduced in Model 5. Lawyers working in law firms with minimal hours (that is, targets) set for pro bono work are more inclined to do pro bono, though the effect is at borderline significance (odds ratio = 5.419; p < 0.10). Lawyers working in firms that have a pro bono manager are 75 percent more likely to do pro bono work than lawyers without these managers (odds ratio = 1.748; p < 0.05). Interestingly, lawyers who report time constraints that limit their ability to do pro bono work are 28 percent more likely to do pro bono than their colleagues who do not report these time constraints (odds ratio = 1.276; p < 0.001). Keeping in mind that our model predicts probability of engaging in pro bono work, perhaps these lawyers are expressing frustration at not being able to devote greater hours to pro bono (rather than time constraints preventing them from doing any pro bono at all). It also is possible that lawyers who experience time constraints in firms without minimal pro bono hour expectations find different “pro bono” opportunities that do not demand considerable time commitments. We also included billable hours as a behavioral measure of lawyers’ time constraints. However, the number of billable hours has no statistically significant impact on whether lawyers do pro bono work.

In Model 6, we introduced economic exchange factors, while controlling for work context and demographic background. Lawyers who strongly believe pro bono work contributes to building legal skills are 190 percent more likely to do pro bono service than those who do not think pro bono yields these skills (odds ratio = 2.903; p < 0.001). Lawyers who are successful at recruiting new clients are also more likely to do pro bono work (odds ratio = 1.013; p < 0.001). The economic, training, and client development benefits associated with pro bono may be especially salient within larger law firms where junior lawyers may be assigned limited roles and routine work and may seek opportunities for meaningful work (Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer and Garth2009).

Model 7 includes the full set of covariates. Most impressively, a strong pro bono cultural norm stirs lawyers to do pro bono service. Lawyers committed to this cultural norm are 264 percent more likely to do pro bono work than lawyers without this commitment, controlling for all other variables in our model (demographics, personality, organizational context, and economic incentives) (odds ratio = 3.641; p < 0.001). Lawyers with strong community civil engagement also have higher odds of doing pro bono service: these lawyers are 58 percent more likely to do pro bono work than those without this sort of community engagement (odds ratio = 1.580; p < 0.05). Lawyers who are involved in political-legal action are also more likely to do pro bono work, though this effect is at borderline significance (odds ratio = 1.431; p < 0.10). Meanwhile, economic factors surface as important drivers of pro bono work. For example, lawyers who are successful “rainmakers”—those engaged in actively recruiting new clients—have higher odds of doing pro bono than lawyers who serve mostly existing clients of their firms (odds ratio = 1.013; p < 0.001). Further, lawyers who view pro bono as offering opportunities for valuable skill acquisition are 31 percent more likely to engage in pro bono work than lawyers who do not share this view, though this effect is at borderline significance (odds ratio = 1.311; p < 0.10). Our full model reveals the importance of collective norms and economic exchange factors as stimulants of pro bono service. Notably, the strength of these effects appears to reduce the impact of personality and organizational factors below statistical significance.

Thus far, we have considered the main effects without exploring how factors may interact to generate pro bono involvement. Our analysis reveals that a strong pro bono cultural norm is highly impactful on the incidence of pro bono (see Model 4), but perhaps this collective norm is conditioned by other factors. Among the organizational enablers and constraints, time constraints surfaced as an important factor (see Model 5), though perhaps not as expected. Faced with demanding schedules and limited time, lawyers do not appear to see their enthusiasm for pro bono dampened. However, Model 8 demonstrates that, when lawyers embrace a cultural norm that supports pro bono but confront pressing time constraints, their likelihood of performing pro bono is reduced (odds ratio = 0.710; p < 0.01). Thus, while cultural norms promote pro bono work, organizational time pressures can operate to inhibit norms favoring pro bono work. In our analysis of exchange factors, we saw that client recruitment is strongly related to the incidence of pro bono (see Model 6). Is it possible that success at client recruitment conditions cultural norms regarding pro bono and consequent pro bono engagement? In Model 9, we observe a significant interaction effect between cultural norms of pro bono and client recruitment: when lawyers embrace cultural norms favoring pro bono and are successful “rainmakers,” they are more likely to take on pro bono work (odds ratio = 1.013; p < 0.01).

Across our models, collective norms offer the strongest explanatory power for lawyers offering pro bono service (coefficient of determination [R2]= 0.207), well above personality (R2 = 0.051), economic factors (R2 = 0.159), and organizational context (R2 = 0.069). Incorporating the full set of dimensions yields further gains in explanatory power (R2 = 0.236) and signals the value of an integrated theoretical model. However, the model is best understood as being comprised not only of additive effects but also of notable interaction effects. Cultural norms favoring pro bono may be applauded for their voracity, but their impact is significantly dampened when lawyers face pressing time constraints in the workplace. Conversely, a strong commitment to pro bono cultural norms in combination with success at recruiting new clients can entice lawyers to venture forth and extend pro bono service. Thus, the impact of collective norms motivating lawyers to engage with pro bono work may be fueled by business opportunities for client recruitment but tempered by organizational time constraints.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Research in the law and society tradition is concerned with human nature—for example, how people experience and respond to disadvantage (Edelman Reference Edelman1977)—and this tradition contends that law serves as a useful terrain for understanding human nature and for observing law practitioners’ role in shaping mechanisms of justice (Galanter Reference Galanter1974; Sarat and Scheingold Reference Sarat and Scheingold2006). In this tradition, we set out to explore why lawyers engage in altruistic behavior by offering their expert services without charge to clients in need. Contemporary paths in the law and society tradition further contend that broader interdisciplinary reflections should be central to social inquiry and that sound theory is vital to understand people’s access to, and interaction with, the law (Savelsberg et al. Reference Savelsberg, Terence Halliday, Morrill, Seron and Silbey2016). Thus, we proposed an integrated framework, drawing on perspectives on altruism rooted in the disciplines of psychology, sociology, and economics and incorporating an emphasis on organizational context drawn from the pro bono law literature. Our qualitative thematic analysis of interview data refined the conceptual foundation of our integrated approach. This analysis led us to develop measures of collectivist norms, client connectivity, skill acquisition incentives, and key organizational factors. Our quantitative analysis of survey data revealed additive and interactive effects of several dimensions derived from the integrated framework. We recap these dimensions below.

Psychological factors play an important role in rousing interest to contribute pro bono service, though not in the way one might anticipate. The psychological literature suggests empathy and a pro-social personality encourage volunteerism (Penner Reference Penner2002; Kee et al. Reference Kee and Chunxiao Li2018; Batson Reference Batson2022). In contrast, we found that a lawyer’s level of empathy, or client connectivity, appears largely unrelated to pro bono service. Yet, a sense of meaningful work in one’s law practice appears to prompt lawyers to venture into pro bono work. However, the causal direction may be reversed here. Our measure of meaningful work perhaps better reflects the fact that pro bono work proffers meaningful experiences rather than the claim that some lawyers hold a predisposition toward, or a desire for, meaningful work. Thus, lawyers’ expression of meaningful legal work is a product, rather than a driver, of pro bono service. From this angle, pro bono work is effective in bringing meaning to lawyers’ daily experiences of practicing law. It may also be, as some suggest, that junior lawyers in large firms pursue pro bono to compensate for work that lacks fulfillment (Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer and Garth2009; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2009).

Collective norms are also a powerful driver of pro bono service. Lawyers who have internalized a strong cultural norm in support of pro bono work are far more inclined to embark on pro bono service. This finding is consistent with research that shows that a sense of duty is a stronger motivator for lawyers than economic ability or time availability (Rhode Reference Rhode2003). Collective norms are not only signaled by shared attitudes but are also embodied in behavioral habits. For example, lawyers who actively engage in community civic organizations are more inclined to do pro bono. This parallels with prior work that shows multiple organizational memberships and prior volunteer experience increase the chances of volunteering (Wilson and Musick Reference Wilson and Musick1997b; Wilson Reference Wilson2000). We also found that lawyers who are heavily involved in political and legal causes are more likely to engage in pro bono service, which is consistent with prior work that suggests that volunteering is related to political involvement (D. Smith Reference Smith1994).