Introduction

Dementia not only affects the person with the diagnosis but also other people in their life. While individualistic deficit-views have dominated the field of dementia research for many decades, there has been a shift towards challenging those models by emphasising the importance of a relational understanding of dementia, one that sees people in the context of their relationships to others (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997; Sheard, Reference Sheard2004). As McGovern (Reference McGovern2011) argues, viewing dementia through the lens of affected relationships encourages and supports togetherness rather than separation, and allows space to see people as active and positive contributors to relationships. This shift in understanding is reflected in a growing body of studies that explore the experiences of couples where one partner has dementia (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Bielsten and Hellström, Reference Bielsten and Hellström2019). Studies which focus on experiences of couples suggest that a better understanding of the dyadic perspective offers health and social care services and key stakeholders essential information to support positive relationships and the wellbeing of both partners (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Whitlatch and Lyons2016; Stockwell-Smith et al., Reference Stockwell-Smith, Moyle and Kellett2019). Such a dyadic perspective is missing in research for people with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia. There is currently no evidence base informing how each partner with intellectual disability may best be supported, and how relationships may be sustained.

People with intellectual disability are at increased risk of dementia. The incidence of dementia in people with intellectual disability other than Down's syndrome has been found to be up to five times higher than in the general population (Cooper, Reference Cooper1997; Strydom et al., Reference Strydom, Chan, King, Hassiotis and Livingston2013). The risk is higher for people with Down's syndrome and increases with age, with estimates that more than half of people 60 or over will have dementia (McCarron et al., Reference McCarron, McCallion, Reilly, Dunne, Carroll and Mulryan2017; Bayen et al., Reference Bayen, Possin, Chen, Cleret De Langavant and Yaffe2018). Older adults have been identified as a rapidly growing group among people with intellectual disability in many western countries (Bittles et al., Reference Bittles, Petterson, Sullivan, Hussain, Glasson and Montgomery2002; Emerson and Hatton, Reference Emerson and Hatton2008; Coppus, Reference Coppus2013; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Sandberg and Ahlström2015). Consequently, the prevalence of dementia among people with intellectual disability is also increasing and support for people to age well has been of increasing interest to researchers, practitioners and policy makers (Scottish Government, 2013; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Lacey and Jervis2018). Older people with intellectual disability may experience additional challenges due to effects of lifelong disability and more general effects of ageing, which has led to some consensus that people with intellectual disability may be ‘old’ from the age of 50 onwards (Grant, Reference Grant, Nolan, Davies and Grant2001; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, McLean, Guthrie, McConnachie, Mercer, Sullivan and Morrison2015). In people with Down's syndrome ‘old’ age may be reached even earlier in life. A baseline assessment of typical functioning from which to measure any health change, including dementia, is recommended at age 30 in the United Kingdom (UK) (Down's Syndrome Association, 2018). Indeed, almost all individuals with Down's syndrome experience frontal lobe changes by age 40, even if not all will go on to develop the symptoms of dementia (Saini et al., Reference Saini, Dell'Acqu and Strydom2022). Furthermore, people with intellectual disability face inequalities in relation to health-care access, with poorer experiences of assessment and treatment processes (Heslop et al., Reference Heslop, Blair, Fleming, Hoghton, Marriott and Russ2014; Truesdale and Brown, Reference Truesdale and Brown2017; O'Leary et al., Reference O'Leary, Cooper and Hughes-McCormack2018).

Such inequities are of concern in older age and difficulties have been highlighted for people in receiving a dementia diagnosis and appropriate post-diagnostic support (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Lacey and Jervis2018). Research about dementia in people with intellectual disability focuses largely on issues around recognition of dementia, support and training needs of staff, or highlights experiences of family members (Furniss et al., Reference Furniss, Loverseed, Lippold and Dodd2012; Perera and Standen, Reference Perera and Standen2014; Cleary and Doody, Reference Cleary and Doody2017). Few studies have explored the experiences of people with intellectual disability who have dementia (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Kalsy and Gatherer2007; Sheth, Reference Sheth2019). Additionally, there have been a limited number of studies exploring peer relationships in the context of intellectual disability and dementia (Forbat and Wilkinson, Reference Forbat and Wilkinson2008; Watchman et al., Reference Watchman, Mattheys, Doyle, Boustead and Rincones2020). Available studies highlight how dementia affects the person and impacts on relationships with others, including friends and those with whom they live (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Kalsy and Gatherer2007; Forbat and Wilkinson, Reference Forbat and Wilkinson2008; Sheth, Reference Sheth2019). While there has been recognition of the need to support peers alongside the person to help maintain positive relationships and interactions, there have been no studies to our knowledge that consider the experiences of couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia. Relationships are important for people's wellbeing and there has been a shift over past decades in policy and practice to recognise the right of people with intellectual disability to have intimate relationships (United Nations, 2007). Relationships and marriage can provide a sense of belonging, security and acceptance, and enhance the quality of life for people with intellectual disability (Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, McConkey and Taggart2013). However, there is also an awareness that people with intellectual disability continue to face barriers to forming and maintaining relationships (Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020).

Review aims

Scoping reviews are helpful to provide an overview of existing knowledge and look at intersections between concepts and themes, as well as identifying research gaps and informing future research (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O'Brien, Colquhoun, Kastner, Levac, Ng, Sharpe, Wilson, Kenny, Warren, Wilson, Stelfox and Straus2016). This review initially sought to address the gap in evidence on couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia. After determining in an initial search (1) that research has not been published on this topic, we drew on intersecting topics in order to identify key themes and areas of interest that are relevant to future studies seeking to understand the experiences of couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia. Subsequent areas of review were: (2) experiences of couples where one partner has dementia (without intellectual disability) and (3) experiences of couples with intellectual disability (without dementia).

Methods

The scoping review consisted of three independent searches. Search 1 involved a search for research on couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia, to establish if any research on this topic existed. Search 2 involved a search for research on couples where one partner has dementia and search 3 involved a search for research on couples with intellectual disability. The review followed Joanna Briggs's guidance (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares2015) to develop the review aims, inclusion criteria and search terms.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

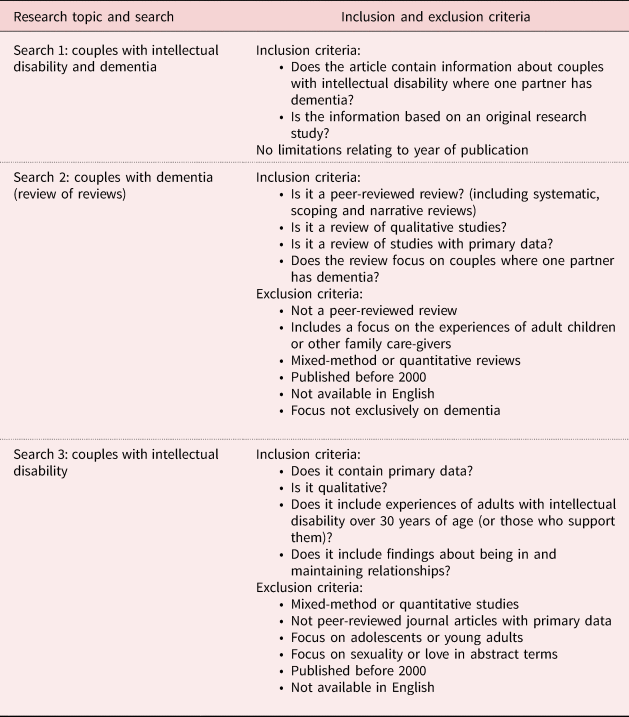

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to guide the screening process to provide transparency and establish limitations to the review. Inclusion criteria required articles to be: peer-reviewed, qualitative research, published since 2000, and relevant to current service provision, policy and practice (for searches 2 and 3 only). Topic specific criteria were also included in each search. This was an iterative process that involved initial searches to develop familiarity with the existing evidence base. For example, an initial search of PsychINFO identified four systematic reviews that synthesised findings of qualitative studies on the experiences of couples where one partner has dementia. This indicated that for search 2 there were more than 30 studies that would meet our inclusion criteria. Thus, we took the decision to perform a review of reviews for search 2 to explore experiences of couples with dementia. Conducting a review of reviews allows for findings of separate reviews to be compared and contrasted (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Devane, Begley and Clarke2011). Additionally, after an initial search for studies on the experiences of couples with intellectual disability, a decision was taken to exclude studies if the majority of participants were aged under 30 years. Our main research topic of interest lies with older couples with intellectual disability, and it became evident that their experiences differ from those of younger generations. Older adults are more likely to have experienced greater barriers to form and maintain relationships due to past societal attitudes and will also have experienced a different service provision context, with higher segregation and less community involvement in many past services (Craft and Craft, Reference Craft and Craft1981; Welshman and Walmsley, Reference Welshman and Walmsley2006). Details of our inclusion and exclusion criteria for each search are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A quality assessment is generally not performed as part of a scoping review where the objective is to focus on existing knowledge and areas of interest rather than assessing the quality of evidence as is typically seen in systematic reviews (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005; Pham et al., Reference Pham, Rajić, Greig, Sargeant, Papadopoulos and McEwen2014). The option of multiple structured searches in a scoping review rather than one in a systematic review was appealing given the focus in an area where there has not yet been published research. Limitations are also acknowledged with a lack of identifying robustness or rigour of the included studies. To mitigate this, we used the inclusion of peer-reviewed publications as a measure of quality (Pham et al., Reference Pham, Rajić, Greig, Sargeant, Papadopoulos and McEwen2014) and considered, as part of the data extraction process, how each study enabled and facilitated the involvement of people with dementia, and people with intellectual disability.

Search strategy

Search terms were developed using PCC (Population–Concept–Context) (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares2015). We drew on existing studies to identify synonyms and related concepts for the main keywords (couples, intellectual disability, learning disability, dementia and qualitative research). The sensitivity of our search was tested using a set of indicator papers already identified as relevant for searches 2 and 3. For searches 1 and 3, we combined only Population and Context or Concept search words to ensure the searches were wide enough to identify existing studies. For search 1, we included the historic term ‘mental retardation’ as this was a term that was widely used in the past and we wanted to capture older studies on this topic. Search terms were combined and used in three databases (PsychINFO, CINAHL, Social Services Abstract; abstract and title) alongside a subject heading search. Additionally, experts within the field were contacted to ask if they were aware of research that had been undertaken, or was ongoing, about couples with intellectual disability affected by dementia, a search of ProQuest Theses was conducted and an advanced Google domain search wase undertaken as part of search 1. For searches 2 and 3, reference lists of included articles were screened to identify studies that might have been missed and we used Google Scholar to identify sources that cited included articles since their publication. An overview of search terms with truncations is shown in Table 2. The process was supported by a subject expert librarian and the first search was conducted in May 2021. The search was later updated to include publications that had been added to the three databases between May and October 2021. Details of the full strategy can be obtained on request.

Table 2. Search terms

Search process

The three searches were conducted independently of each other and results were extracted into Covidence systematic review management software (Veritas Health Innovation, nd). The screening of titles and abstracts was conducted by one reviewer and all full-text records were assessed independently by two reviewers. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer, and difficult decisions were taken after discussions with the whole review team.

In search 1, combining couples with intellectual disability and dementia yielded few results across the three databases, as expected. Titles and abstracts of 57 records were screened against the inclusion criteria, and 51 were identified as not relevant as they related largely to genetic research and animal studies. Six full texts were retrieved but none met our inclusion criteria; two included information on couples with intellectual disability but without the presence of dementia, one was a duplicate, and three were not original research studies – including a practice case study from a nursing perspective and a personal account of a man with intellectual disability about living with his wife who had Alzheimer's disease.

Search 2 yielded 556 records. After screening title and abstract, 56 articles were retrieved and assessed for full-text eligibility with eight reviews meeting the inclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion at full text were reviews that included discussions of the experiences of other family members such as experiences of adult children or siblings. Quantitative and mixed-method reviews were excluded, but after discussions within the team it was decided to include the review by Holdsworth and McCabe (Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a), which includes two quantitative studies. It was unclear how the quantitative data were used by the authors in this review, with the findings section providing only a synthesis of the qualitative findings. Additionally, reviews which compared experiences of dementia with other health conditions such as depression were excluded.

In search 3, titles and abstracts were screened from 1,604 records, with 1,521 not meeting the inclusion criteria. Eighty-three records were retrieved and assessed for full-text eligibility with ten studies meeting the inclusion criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion at full text related to studies that focused on sexuality and on barriers for people to form relationships, without including data on people being in or maintaining relationships. Fifteen studies were excluded because they focused on the experiences of young adults with intellectual disability. We also excluded one study that focused on parents with intellectual disability.

No additional studies were identified through the screening of reference lists. An overview of all screening processes can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowcharts for searches 1–3.

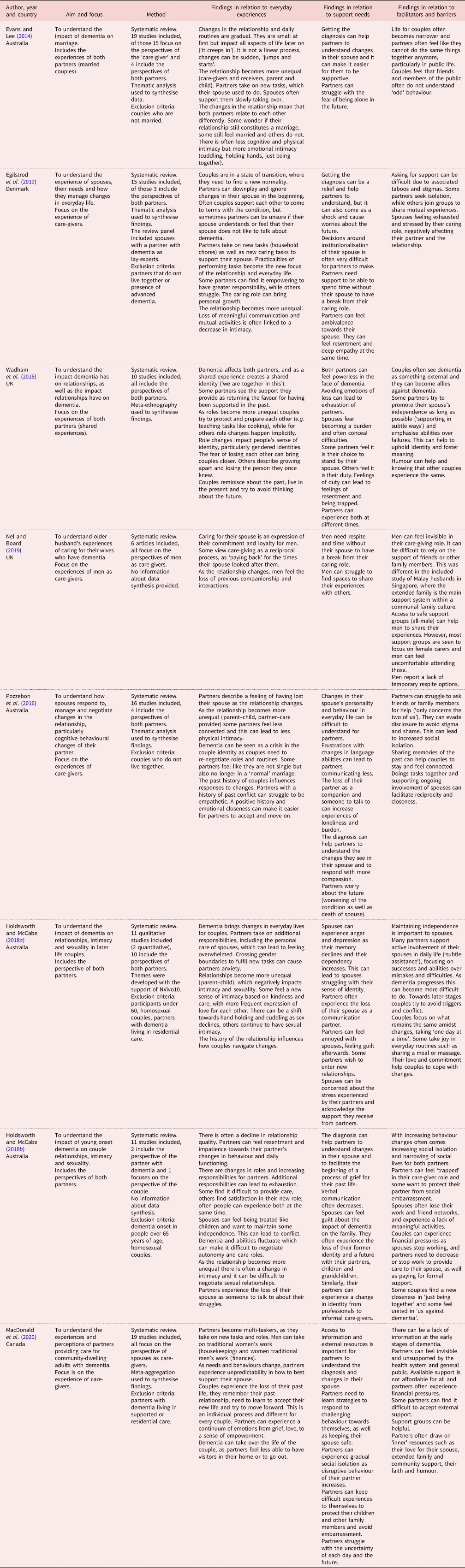

Table 3. Overview of included reviews search 2

Note: UK: United Kingdom.

Data extraction and analysis

Firstly, we collected information about the characteristics of included studies (year of publication, author names, country), followed by looking at how research was conducted, and whose perspectives were included (methodological findings). This first step of the data extraction process helped us to provide an overview of the included articles.

Secondly, we combined inductive and deductive approaches during the analysis and coding of articles, addressing predefined areas of interest while remaining receptive to unforeseen concepts and themes of relevance. The intention was to identify key themes related to each search rather than to synthesise across both (Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Davies, Peters, Tricco, Alexander, McInerney, Godfrey, Khalil and Munn2021). We started by coding articles line by line in relation to everyday experiences, support needs, and barriers and facilitators to support and maintain relationships and summarised those for each article (Tables 3 and 4). We developed new codes for content that did not fit our existing coding framework. New codes were re-read and connections were established leading to the identification of additional key-processes that were of relevance to our research question. Thus, during the coding process we began to extend our predefined areas of interest to think more closely about different approaches to care and support in relationships that were evident in searches 2 and 3 and sought to capture how the context in which relationships happen is different for couples with intellectual disability compared to couples affected by dementia in the general population. As a last step, we summarised differences in the context of people's lives, barriers and facilitators, and key-processes for each search. The first author led the analysis with each step discussed with the research team to ensure that no information or nuances had been missed or misrepresented.

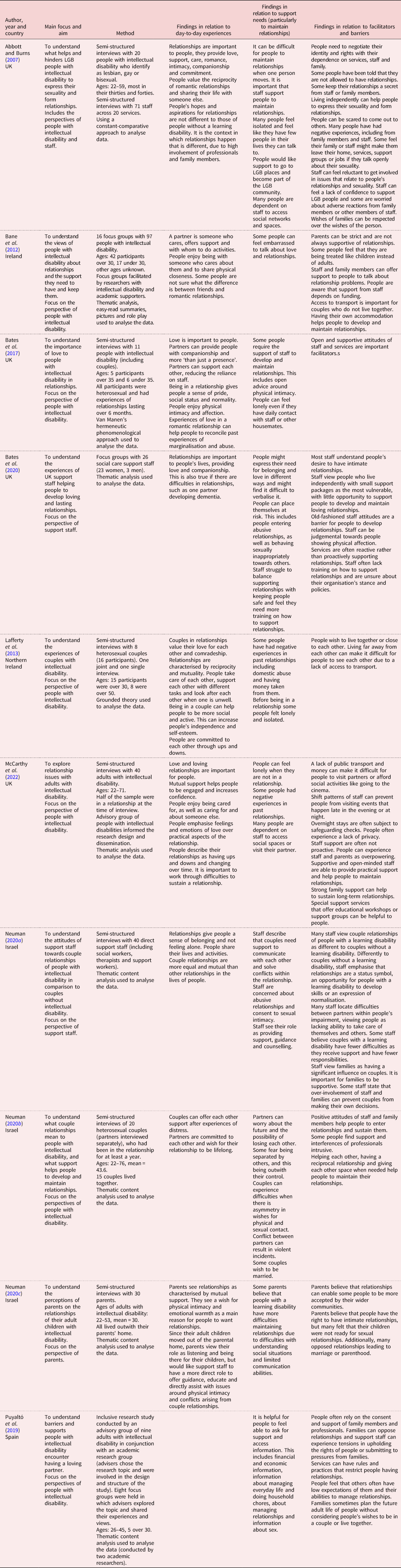

Table 4. Overview of included studies search 3

Note: UK: United Kingdom.

Overview of included articles

Search 1: couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia

Search 1 of our scoping review established that there has, to date, been no research on the experiences of couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia. In the following section we will provide an overview of findings from searches 2 and 3, before discussing differences in the context of people's lives and drawing out approaches to care and support and facilitators and barriers that were identified in each search.

Search 2: couples (non-intellectual disability) where one partner has dementia

Of the eight included reviews, four were conducted in Australia, two in the UK, one in Denmark and one in Canada. Seventy-three primary qualitative studies were included across the eight reviews (including six dissertations and theses), and correspondingly to where the review teams were located, 34 studies were conducted in North America, 33 in Europe, 11 in Scandinavia and 17 in the UK. Thus, findings related predominantly to experiences of western populations with two reviews highlighting that experiences in other cultures will be different (Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Nel and Board (Reference Nel and Board2019) also highlighted the role of extended family support in their study of Malay husbands in Singapore. Three reviews highlighted that most of their included studies related to people in the early stages of dementia (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019) and four had excluded studies in which partners were no longer living together (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Additionally, four reviews excluded the experiences of LGBT couples from their review (Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018b; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019; Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019), and one reflected that, although they would have included LGBT couples, all included primary studies had been based on interviews with heterosexual couples (MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Fifty-three studies focused on the perspective of partners without dementia, 18 included the perspectives of both partners and one focused only on the experience of the person with dementia (Harris, Reference Harris2004). Additionally, one study included separate sections on the experiences of partners without dementia and, from different couples, the experiences of people with dementia (Harris and Keady, Reference Harris and Keady2009). There was little information or reflections in primary studies and reviews about difficulties or successes in involving people with dementia in interviews or if additional methods had been used to facilitate their inclusion. Notable exceptions included the use of observations alongside interviews (Boyle, Reference Boyle2013), photo and video elicitation to capture everyday life experiences (Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Dahlke and Purves2013) and ethical considerations of consent issues (Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nolan and Lundh2007).

All reviews offered insight into the everyday experiences of couples and how they navigated changes and complexities in their relationship. There was less information about facilitators and barriers to support and it was evident across all reviews that the experiences of couples were largely presented without making references to wider support systems, policies and the service provision context. The limited mention of formal support in the lives of couples in search 2 may be indicative of studies being conducted with couples at early or mid-stages of dementia when informal care may be the main source of support (Kerpershoek et al., Reference Kerpershoek, Wolfs, Verhey, Jelley, Woods, Bieber, Bartoszek, Stephan, Selbaek, Eriksen, Sjölund, Hopper, Irving, Marques, Gonçalves-Pereira, Portolani, Zanetti and Vugt2019). Thus, narratives of care and support needs remained firmly located within the private lives of the couple. There were few reflections on the quality of care and support that couples received from professionals or services. Reviews highlighted the need for emotional support after the dementia diagnosis to help couples process information about the progression of dementia (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018b; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019). The need to strengthen support towards more advanced stages of dementia was evident in three reviews, detailing that partners without dementia need help to plan their spouse's care and manage complex emotions about a possible move into a care setting and the anticipated death of the person with dementia (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Additionally, a lack of formal support was indirectly implied by emphasis on stress and care burden of partners without dementia, and how this negatively impacted on the relationship (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019). Partners without dementia were described as becoming informal carers, next to being partners, and regular respite from their caring role was identified as a facilitator to maintain positive relationships by two reviews (Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019; Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019). Furthermore, MacDonald et al. (Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020) described how couples often experience financial pressures and the authors made links between inequalities in access to support and financial resources available to couples.

There were differences identified depending on whose perspectives were included. Studies that excluded the perspective of the partner with dementia emphasised experiences of care burden and stress of the partner without dementia (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Reviews that included studies on the experiences of partners with dementia described occurrences of reciprocity and included more positive descriptions of love and affection between partners, with a greater recognition of the needs and experiences of both partners (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a).

An overview of the eight reviews and findings in relation to everyday experiences, support needs, and facilitators and barriers can be found in Table 3. To avoid referring to one partner as ‘the partner with dementia’ throughout, the term spouse is used when referring to the individual with dementia, and the term partner to refer to the person without dementia.

Search 3: couples with intellectual disability

Of the ten included studies, five were conducted in the UK, three in Israel, one in Ireland and one in Spain. All three articles from Israel were conducted by the same researcher and explored couple relationships from the perspectives of people with intellectual disability, family members or professionals (Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a, Reference Neuman2020c, Reference Neuman2020b). Likewise, three of the UK publications included the same researchers, with two focusing on the perspectives of people with intellectual disability (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022) and one on the views of support staff (Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020). Overall, six articles explored the topic from the perspective of people with intellectual disability (Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, McConkey and Taggart2013; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017; Puyaltó et al., Reference Puyaltó, Pallisera, Fullana and Díaz-Garolera2019; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020b; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022), one article included the perspectives of both people with intellectual disability and staff (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007), two utilised the perspective of professionals only (Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a) and one article focused on the experiences of parents (Neuman, Reference Neuman2020c). Eight studies included data on experiences of heterosexual relationships, with only Abbott and Burns (Reference Abbott and Burns2007) including experiences of LGB people with intellectual disability, and the study by McCarthy et al. (Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022) including two participants attracted to the same sex. Three studies had inclusive research teams with people with intellectual disability acting as co-researchers and advisers (Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Puyaltó et al., Reference Puyaltó, Pallisera, Fullana and Díaz-Garolera2019; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022). All three were the only studies in this search that referred to using alternative data collection methods alongside interviews to explore the topic with participants with intellectual disability. This included using easy-read material, visual methods, case-stories and role-play.

The included studies provided evidence of barriers to people forming relationships, ranging from lack of staff training, attitudes of staff, cultural views of people with intellectual disability as vulnerable and different, to environmental barriers such as lack of access to private living spaces and own accommodation (Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, McConkey and Taggart2013; Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022). Additionally, our findings suggest that moves to new services and couples not living together can be particular barriers for couples with intellectual disability to maintain relationships due to a lack of access to transport and dependence on staff to support visits (Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, McConkey and Taggart2013; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022). However, information about everyday experiences of couples remained somewhat superficial. Findings highlighted the value of love, companionship and mutual support for people, but there was little exploration of emotional complexities and how couples navigate changes in their relationship (Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, McConkey and Taggart2013; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020c; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022). This may be explained by a stronger focus on experiences of and attitudes towards people forming intimate relationships, rather than exploring experiences of actually being in a relationship. Three of the ten included studies contained minimal information on people's experiences of being part of and maintaining relationships (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Puyaltó et al., Reference Puyaltó, Pallisera, Fullana and Díaz-Garolera2019).

An overview of the ten studies is given in Table 4.

Findings

Context: private and public lives

Both searches 2 and 3 highlighted that being a partner, husband or wife is an important part of people's identity and that love and support from the relationship helps couples to manage challenges and overcome adversities (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017, Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020; Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019). It was the context in which people's lives took place and relationships happened that was different across the two searches. While search 2 focused primarily on the care-dyad involving both partners, studies in search 3 described the lives of couples with intellectual disability happening within a web of relationships with professionals and family members. This demonstrated a care-triad that was impacted upon by service provision, as well as cultural attitudes, resources and policies.

Findings from search 3 showed that most couples with intellectual disability have support structures in place before the diagnosis of dementia. Yet, all studies in search 3 described how support could at times act as a barrier to people's relationships. For example, both searches 2 and 3 discussed issues of consent in relation to sexuality and physical intimacy. This is a new area of complexity for couples without intellectual disability where one partner has dementia, and one that seemed to remain largely private (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018b). For people with intellectual disability, their wishes to have physically intimate relationships was often public, with staff or family members functioning as gatekeepers (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a, Reference Neuman2020c; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Bates, Elson, Hunt, Milne-Skillman and Forrester–Jones2022). There was evidence in both searches that people, including professionals, can feel uncomfortable talking about sexuality and that it is still a neglected area of support for people with dementia (without intellectual disability) and people with intellectual disability (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018b; Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020c). Thus, although the intimate lives of people with intellectual disability were often managed and governed by others, they were simultaneously also disregarded and hidden.

Overall, the private lives of couples in search 2 stand in contrast to a focus on societal barriers in search 3. All studies in search 3 on the experiences of couples with intellectual disability had a strong focus on context and made close links to the influence of societal attitudes, service provision and available resources. However, a detailed understanding of how couples with intellectual disability navigate complexities and how relationships can change over time was lacking from search 3.

Search 2: exploring emotional complexities over time

In search 2, included reviews explored emotional complexities and identified gradually changing relationships. An altered sense of identity and routines were explored as happening over time, with partners referring to the unpredictability of dementia. Dementia was described as involving a steady decline, individual to each person, but not always linear. Abilities of people could change from day to day, at times fluctuating quickly and sometimes with a marked decline (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Couples reported difficulties in planning for and thinking about the future which was linked to a sense of taking one day at a time and living in the present (Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a). Additionally, reviews highlighted the importance of understanding the history of couples to make sense of their experiences (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). It was evident that dementia is a shared experience and affects both partners, provoking complex emotions of love, empathy, loss, resentment, anger, ambivalence and guilt. Several reviews highlighted that differences in emotional responses could be partly explained by past dynamics and ways of relating (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). However, a lack of situating these experiences into the wider context of available formal support was problematic as difficulties and problems were at times seemingly linked to the behaviour and support needs of the person with dementia, instead of emphasising a wider lack of support for couples.

Search 3: different approaches to support and care

Ways of supporting and caring were framed differently and could shift within presented narratives across the articles in search 3. This included thinking about support as unidirectional and being provided by one person to enable the independence and autonomy of another. This concept of support was most prominent in the narratives of staff in search 3. Here barriers to relationships were linked to people with intellectual disability lacking skills and knowledge to have safe relationships (Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020), relationships were seen as a learning process enabling people with intellectual disability to improve their social skills (Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a) and, on another level, staff themselves felt they lacked skills and needed training to provide people with relationship support (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007). Thus, support was seen as teaching people skills and educating them to develop ability and capacity to be in relationships with arguments of incapacity, risk and vulnerability used to explain why relationships might be discouraged. However, staff narratives across the three studies interestingly also included ways to think about support in more relational ways. Here risks and vulnerability were linked to social isolation (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020). Staff stressed the importance of being there for people as an attentive and supportive presence (Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a: 720) with barriers to form and maintain relationships explained by an absence of continuity in close support networks for people with intellectual disability. Similarly, staff also talked about their own support needs in relational ways, talking about feeling left alone and often unsupported, and staff in two of the studies critiqued an organisational culture that responds to incidents or brings in external professionals to provide isolated interventions rather than building internal capacities and networks of support for people (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Bates et al., Reference Bates, McCarthy, Milne Skillman, Elson, Forrester-Jones and Hunt2020).

Searches 2 and 3: relational care, belonging and reciprocity

Relational ways of thinking about support were characteristic of the narratives provided by couples with intellectual disability and couples with dementia. People with intellectual disability stated that they needed the support of others to maintain relationships (Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017; Puyaltó et al., Reference Puyaltó, Pallisera, Fullana and Díaz-Garolera2019; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020b). Thus, people challenged an individualistic view of choice and ability by highlighting the need for interdependence, stressing the need for the support of others to realise their choices and wishes. When the support they received focused on an assumed lack of abilities or was based on views that people with intellectual disability are different and that intimate relationships are inappropriate, then support of others became oppressive and disempowering (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020b). Thus, the experiences of people with intellectual disability highlighted that relational support did not mean having many people in one's life. Bates et al. described that experiences of isolation and loneliness

did not appear to be influenced by the number of people participants came into contact with as their living situations typically included numerous staff and housemates. This suggested the significance of their relationship with their partner who provided more than just a ‘presence’. (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017: 70)

Similarly, couples in search 2 described feelings of isolation and loneliness. Couples described feeling that others did not understand their experiences and that there was little acceptance or inclusive spaces for people with dementia in public (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Many couples experienced a narrowing of their lives, and the relationship could be one of the only places where partners with dementia continued to experience belonging (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018b).

It was evident across searches 2 and 3 that couples and people with intellectual disability linked inclusion and involvement with a sense of belonging, rather than learning or retaining skills. Belonging was defined by people as feeling valued and accepted, and seemed to be the main objective of providing relational support. Partners without dementia supported their spouse in subtle ways (Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a), stressing the importance of doing things together and keeping each other company (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016) over agency or the efficient completion of a task (Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016: 7). In this context, when talking about care and support, many couples talked about reciprocity. In search 2, reciprocity, seeing the value and contribution of both partners to the relationship, seemed to help partners without dementia to re-frame their care-role in a positive light as giving back (Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019). Furthermore, partners with dementia saw themselves as giving and supporting within the relationship and this helped them to uphold identity and foster meaning. At the same time, all reviews included narratives that described the increasing unequal relationship between partners and four drew comparisons to parent–child relationships (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Holdsworth and McCabe, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018a, Reference Holdsworth and McCabe2018b). Advanced stages of dementia were linked with the inability of partners with dementia to contribute to the relationship. The possibility of reciprocity was questioned in relationships where one partner needed to care physically for the other, dressing or bathing them, or where the person with dementia was seen as no longer able to engage verbally or cognitively (Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019). Other studies continued to see people with dementia as active participants within their relationships by emphasising people's care and love for their partner without dementia, expressed through concerns about their wellbeing, holding hands, cuddling and just being together (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Braithwaite, Golish and Olson2002; Hellström et al., Reference Hellström, Nolan and Lundh2007; Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Wadham et al., Reference Wadham, Simpson, Rust and Murray2016).

Reciprocity was also used to describe experiences of couples with intellectual disability (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, McConkey and Taggart2013; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Terry and Popple2017). The relationship to a partner was important to people because it provided them with a sense of belonging, facilitating independence and social participation through interdependence. Studies described levels of reciprocal care and mutuality between partners, where partners helped each other with everyday tasks and health-care needs, increasing possibilities for participation and independence. This experience was contrasted to experiences of being treated as a child in other relationships in their lives (Bane et al., Reference Bane, Deely, Donohoe, Dooher, Flaherty, Iriarte, Hopkins, Mahon, Minogue, Donagh, Doherty, Curry, Shannon, Tierney and Wolfe2012; Puyaltó et al., Reference Puyaltó, Pallisera, Fullana and Díaz-Garolera2019; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020b). Thus, in contrast to search 2, experiences of inequality for people with intellectual disability related to their relationships to staff and family. People with intellectual disability felt that they were often viewed as care recipients, with staff and family members in the role of care-givers.

Discussion

We identified processes that were associated with facilitating positive interactions in relationships, helping couples to maintain relationships and increasing social inclusion. This included relational care, belonging and reciprocity; concepts that are discussed below drawing on wider literature about people with intellectual disability and dementia. Additionally, it was evident that care and support are complex processes that take place across different spheres, which may help to understand how care and support can be both empowering and oppressive.

Belonging and reciprocity

Belonging and reciprocity have been highlighted as key components of social inclusion, both in relation to people with intellectual disability (Fulton et al., Reference Fulton, Kinnear and Jahoda2021) and people with dementia (Gove et al., Reference Gove, Small, Downs and Vernooij-Dassen2017). Furthermore, Sheth's (Reference Sheth2019) study on barriers and facilitators to participation in daily life for people with intellectual disability and dementia highlights that reciprocity and helping others is important for people with intellectual disability and dementia, and creates meaning and purpose. Yet, search 2 also highlighted the complexity of what reciprocity means in an increasingly unequal relationship. Articles in our review included narratives that depicted partners with dementia as unable to reciprocate as their verbal and cognitive abilities were declining. This view has been challenged by researchers who stress that reciprocity in relationships can be richer and more complex than thinking about it as giving and taking in equal measures, and that it is important not to overlook subtle ways of reciprocity by people with dementia, such as a smile or reaching out (Ericsson et al., Reference Ericsson, Kjellström and Hellström2013; Gove et al., Reference Gove, Small, Downs and Vernooij-Dassen2017; Driessen, Reference Driessen2018). In her ethnographic study of Dutch residential services for people with dementia, Driessen (Reference Driessen2018) explores how moments of pleasure are experienced relationally and require the engagement of the person with dementia and those supporting him or her. She argues that moments of pleasure and joy, such as dancing together, having a meal or listening to music, is shared and experienced by both people in the care relationship, blurring lines between care-givers and receivers. Similarly, Fulton et al. (Reference Fulton, Kinnear and Jahoda2021), in their recent systematic review on belonging and reciprocity among people with intellectual disability, stress that reciprocity is not contingent upon equal exchange. Thus, as people's abilities change, they might need others to take the initiative in creating possibilities for inclusion and participation, but the experience of those moments and interactions is a shared one to which both partners contribute (Ericsson et al., Reference Ericsson, Kjellström and Hellström2013).

Relational care and support

Within the field of disability studies, care and support are often seen as somewhat opposite concepts. The term care has been critiqued as reinforcing views of people with intellectual disability as passive recipients of care and associated with a past of institutionalisation and experiences of oppression and powerlessness (Schormans, Reference Schormans, Barnes and Brannelly2015). It is a term that is at times avoided when writing about the lives of people with intellectual disability. Instead, the term support is commonly used to emphasise agency, choice and independence, which is reflected in policies that promote self-directed services (Glendinning, Reference Glendinning2008; Jingree, Reference Jingree2015; Lakhani et al., Reference Lakhani, McDonald and Zeeman2018). As our findings showed, an individualistic view of support can also be problematic because it can negate needs associated with vulnerability (Barnes, Reference Barnes, Barnes, Brannelly, Ward and Ward2015) and can suggest that skills and abilities are intrinsic properties that can be learned or retained. Subsequently, people's abilities to make choices and participate in decision-making processes can be denied (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Quayle, Wilkinson and MacMahon2021). Similarly, Jingree (Reference Jingree2015), in her discourse analysis of staff arguments about facilitating choice for people with intellectual disability, demonstrates how emphasising incapacity as an intrinsic property is frequently used by staff to deny people involvement and choice. Our review shows that a relational perspective may offer greater possibilities for social inclusion. A relational perspective asserts that being a person is not defined by being rational and autonomous, but by having the capacity to be in relationships with others and add value to their lives (Kittay, Reference Kittay2001). Correspondingly, people with intellectual disability and partners with dementia stressed the importance of a sense of belonging and reciprocity over independence and being able to do things alone. They emphasised how belonging was connected to feeling valued and accepted, and how reciprocity enabled a view of both people within a relationship as giving and receiving. Vulnerabilities could be acknowledged alongside people's rights to participation, as inclusion and involvement were not dependent on internal properties and skills but seen as taking place in and through relationships in everyday life (Ursin and Lotherington, Reference Ursin and Lotherington2018).

Different spheres of care and caring

As Morris (Reference Morris1991) previously argued, there appears to be value in expanding our definitions of support and care from a narrow focus on physical tasks and experiences of care-givers and care-receivers separately, towards shared experiences of caring. Alongside physical and practical ways of providing support, our findings highlight the importance of emotional support. Considering identified support needs across the two searches, there appears to be value in paying closer attention to the emotional realm of caring. In search 3 people with intellectual disability stressed the need to have people in their lives they could talk to about difficulties in their relationships, while studies also highlighted that staff and parents can feel uncomfortable or lack confidence to support couples to manage conflicts (Abbott and Burns, Reference Abbott and Burns2007; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020a, Reference Neuman2020c). In search 2, two reviews described how after the dementia diagnosis couples can feel left alone with the fears it evokes, with little ongoing emotional support (Nel and Board, Reference Nel and Board2019; Macdonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). The need for emotional support after a dementia diagnosis has also been highlighted by social care staff and family members of people with intellectual disability and dementia (Carling-Jenkins et al., Reference Carling-Jenkins, Torr, Iacono and Bigby2012; Iacono et al., Reference Iacono, Bigby, Carling-Jenkins and Torr2014). Furthermore, it was evident from search 2 that couples needed support to make sense of changes in their relationship over time and manage emotional complexities that occur. For example, while couples felt commitment and empathy, they could also experience moments where they blamed their partner and resented them. This was linked to people feeling exhausted and struggling to respond to distressed behaviour in empathetic ways. This is important to keep in mind when considering the experiences of couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia as evidence does not tell us how couples with intellectual disability navigate this complex process. We know from search 2 that dementia affects both partners and provokes complex emotions of love, empathy, guilt, ambivalence and loss. This may be similar for partners with intellectual disability, and it is important to explore how people navigate this emotional complexity and identify support needs.

Emotional responses and dynamics between partners do not take place in isolation but are influenced by the wider support systems that are available to couples. Rogers (Reference Rogers2016) outlines three spheres of caring: the emotional caring sphere, the practical caring sphere and the socio-political caring sphere. She stresses the importance of exploring interactions between people's emotional responses to care and caring, practices of care within people's microsystems, and the wider socio-economic context in which care and caring take place.

Drawing on Nodding's (Reference Noddings2002) work on ethics of care, Rogers (Reference Rogers2016) differentiates between care in relation to practical activities, the realm of caring for and the emotional realm of caring about someone, feeling responsibility, commitment, love and empathy. She explains that a better understanding of different spheres can help us to understand how care and support can be both empowering and oppressive. People can provide practical care and support for someone while feeling resentment towards them or viewing them as lacking abilities. An acknowledgement of different spheres can also help to understand how individuals can care about each other and provide important experiences of love and belonging but might be unable to provide practical support and care in equal measures. Additionally, Rogers (Reference Rogers2016) stresses the importance of understanding that care takes place and is dependent on wider systems of support. She argues for the importance of lifting care out of the private realm, to examine critically how it is valued and how far those within care relationships are supported by society. Thus, care becomes both a private matter and a public concern (Schormans, Reference Schormans, Barnes and Brannelly2015).

Implications for future research with couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia

Findings highlight the need to investigate further the emotional realm of care and support, as well as the importance of situating people's experiences within the wider socio-political context, noting the influence of available resources, networks of formal support and societal attitudes. Given the lack of existing evidence, it will be important to explore if people with intellectual disability are given the option to care for their partner in the context of dementia, if caring roles are overlooked, and how both partners are and can be supported, including how couples manage emotional complexities. It is apparent from research on adults with intellectual disability living with older parents that people's contributions to care relationships are often not noticed, and are seldomly reflected on (Walmsley, Reference Walmsley1993; Knox and Bigby, Reference Knox and Bigby2007; Truesdale et al., Reference Truesdale, Taggart, Ryan and McConkey2021). In relation to couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia, this might translate into a risk that the partner without dementia is not recognised and supported in their caring role. In her research on people with intellectual disability in caring roles, Walmsley (Reference Walmsley1993) describes how providing care for someone else can be an opportunity for people to experience social value and acceptance but can also result in experiences of exploitation if people's caring role is not formally recognised.

Fears about the future in relation to dementia advancing, the possibility that people with dementia might need to leave their home and the death of the person with dementia were prominent for couples in search 2 (Evans and Lee, Reference Evans and Lee2014; Pozzebon et al., Reference Pozzebon, Douglas and Ames2016; Egilstrod et al., Reference Egilstrod, Ravn and Petersen2019; MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Martin-Misener, Weeks, Helwig, Moody and Maclean2020). Fears about the future might be further exacerbated for people with intellectual disability who often experience that decisions about their life are made beyond their control. Staff may avoid talking to people with intellectual disability about life-limiting conditions and death as they are concerned that it will upset the person (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Reference Tuffrey-Wijne, Giatras, Butler, Cresswell, Manners and Bernal2013; Tuffrey-Wijne and Rose, Reference Tuffrey-Wijne and Rose2017). People with intellectual disability are not always told about their dementia diagnoses (Watchman, Reference Watchman2016; Sheth, Reference Sheth2019) and are not routinely involved in Advanced Care Planning (Heslop et al., Reference Heslop, Blair, Fleming, Hoghton, Marriott and Russ2014; Wiese et al., Reference Wiese, Stancliffe, Dew, Balandin and Howarth2014; Noorlandt et al., Reference Noorlandt, Echteld, Tuffrey-Wijne, Festen, Vrijmoeth, van der Heide and Korfage2020). It will be important for future studies to explore how far the person with intellectual disability and dementia and their partner are involved in planning future care and support. This should also involve an exploration of dementia disclosure and if, how and when information about the progression of dementia is communicated to both partners. Qualitative research on the experiences of people with intellectual disability who have life-limiting conditions, predominantly cancer, have shown the importance of taking a person-centred approach, sensitively disclosing information and having conversations as people's needs and circumstances are changing. This includes continuously assessing people's understanding of their illness and of abstract concepts such as time, in addition to exploring their preferences for disclosure to facilitate involvement in care planning (Tuffrey-Wijne, Reference Tuffrey-Wijne2013; McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, Mirfin-Veitch, Conder and Brandford2017).

Finally, it was notable across both searches 2 and 3 that there is often little consideration or reflection on the process of including people with intellectual disability or dementia as research participants in accessible ways. Using inclusive approaches will be important in future studies, as previous researchers have highlighted challenges of meaningfully including people with intellectual disability and dementia using traditional interview methods (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Kalsy and Gatherer2007; Forbat and Wilkinson, Reference Forbat and Wilkinson2008; Sheth, Reference Sheth2019). Using alternative approaches might help researchers to explore the journey of the couple over time to capture changes in their relationship and facilitate an understanding of the complex concepts of past, present and future. Additionally, alongside recognition that care and support take place within extended support networks, it can be valuable to explore the topic from different perspectives, including staff and family members, as well as both partners.

Conclusion

Exploring relationships in the context of older couples with intellectual disability and couples affected by dementia allowed us to identify areas of interest and key processes that will be relevant for future research with couples with intellectual disability where one partner has dementia. Search 2 highlighted how couples affected by dementia can be supported to maintain positive interactions. This included the need for emotional support for both partners, emphasising interdependence over independence, and recognising that partners with dementia continue to show love and affection while the relationship becomes more unequal in other areas. Search 3 emphasised that the starting point for most couples with intellectual disability will be different to that of couples in the population generally. While formal support is likely to be in place for couples with intellectual disability, it can act as a facilitator as well as barrier to the relationship. People with intellectual disability are often referred to in terms of vulnerability and difference, not involved in key decisions that affect their lives, and are dependent on staff, organisational processes and available resources.

As studies were not available about the experiences of couples with intellectual disability living with dementia, implications for future research can only be tentative until more robust evidence is generated. Future studies about this topic have the potential to emphasise the importance of intimate relationships in the lives of people with intellectual disability throughout the lifespan and may challenge the invisibility of people with intellectual disability in caring roles.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Dunhill Medical Trust. No role was played by the funder in the development of this review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This review uses secondary data and ethical approval was not required. The study from which this review derives was awarded ethical approval by the NHS Health Research Authority Social Care Research Ethics Committee (ID 289105).