Introduction

Psychological distress is highly prevalent in cancer patients. About one-third to one-half of cancer patients experience depression and anxiety during the course of their illness (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Chan and Bhatti2011; Brandenbarg et al., Reference Brandenbarg, Maass and Geerse2019). Psychological distress influences patients’ quality of life (Fujisawa et al., Reference Fujisawa, Inoguchi and Shimoda2016), and may even affect their life prognosis (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Koopman and Cordova2003), and thus appropriate management is important (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2017).

Various types of interventions have been proven effective for psychological distress of cancer patients (Traeger et al., Reference Traeger, Greer and Fernandez-Robles2012; Faller et al., Reference Faller, Schuler and Richard2013; Kalter et al., Reference Kalter, Verdonck-de Leeuw and Sweegers2018). Among them, mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), have been establishing strong evidence in cancer care (Cillessen et al., Reference Cillessen, Johannsen and Speckens2019; Oberoi et al., Reference Oberoi, Yang and Woodgate2020). They are known to improve quality of life, fatigue, sleep, stress, depression, and anxiety of cancer patients (Shneerson et al., Reference Shneerson, Taskila and Gale2013; Gotink et al., Reference Gotink, Chu and Busschbach2015; Haller et al., Reference Haller, Winkler and Klose2017; Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Burrell and Jordan2018).

However, there are several barriers for effective delivery of MBIs for patients with cancer. Structural barriers include time constraint, financial constraint, and lack of sufficient therapist. Non-structural barriers include patients’ characteristics (such as demographic, personality, and clinical background) that impede effectiveness of MBIs (Gask, Reference Gask2005; Mohr et al., Reference Mohr, Ho and Duffecy2010, Reference Mohr, Ho and Duffecy2012). In order to efficaciously allocate limited resource to cancer patients, the identification of predictors and moderators of MBIs in cancer patients is considered useful. Past studies suggest that female patients (Nyklicek et al., Reference Nyklicek, van Son and Pop2016) and patients with higher education (Tovote et al., Reference Tovote, Schroevers and Snippe2017) are more likely to benefit from MBIs. A few personality tendencies, such as higher attachment avoidance (Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017), lower extraversion (Nyklicek et al., Reference Nyklicek, van Son and Pop2016), lower conscientious, and higher neuroticism, have been suggested as predictors of effectiveness of MBIs (Jagielski et al., Reference Jagielski, Tucker and Dalton2020). In a sample of patients with primary breast cancer, patients who are under radiation therapy experienced smaller effect of MBIs (Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017). Treatment adherence is another predictor for better treatment outcome (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Crane and Parsons2017). Also, comorbid personality disorder is associated with poor treatment adherence, which may lead to poorer treatment outcomes (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Cho and Lee2013). However, these findings derive from different patient populations and have been inconsistent.

Another direction of efficacious delivery of MBIs is to make the interventions briefer, so that larger number of patients are accessible to the intervention. In fact, several studies examined shortened versions of MBIs in cancer patients (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Sekelja and Frasca2018). Reducing the “dosage” of MBIs reduces the burden of both the cancer patients and the therapists; however, it may also reduce the effect size of the treatment. Therefore, the identification of appropriate dosage of MBIs is necessary.

Thus, the aims of the present study are (1) to identify characteristics (predictors and moderators) of patients who benefit from MBCT for psychological distress in the scope of selectively provided MBCT to patients who are most likely to benefit from the intervention and (2) to explore the treatment reaction according to the “dosage” of MBIs and to identify the minimum number of sessions that yield significant clinical effect. We hypothesized, based on the past studies (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Cho and Lee2013; Nyklicek et al., Reference Nyklicek, van Son and Pop2016; Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017; Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Crane and Parsons2017; Tovote et al., Reference Tovote, Schroevers and Snippe2017; Jagielski et al., Reference Jagielski, Tucker and Dalton2020), that patients’ age, educational history, time since cancer diagnosis, quality of life (QOL), level of psychological distress, and adherence to MBI program are significantly associated with the effectiveness of the intervention.

Methods

Study design

This study is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of MBCT for breast cancer patients. The details of the original study are described elsewhere (Park et al., Reference Park, Sato and Takita2020). In short, 74 patients were randomized in 1:1 ratio to either eight-week MBCT or the wait-list control. The participants’ eligibility for the RCT was the following: (1) clinical diagnosis of Stage 0–III breast cancer, (2) aged between 20–74, (3) the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) total score of five or over at recruitment, (4) the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, (5) estimated prognosis of survival of 1 year or over, (6) ability to communicate in Japanese, and (7) submission of written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were the patients with (1) past experience of MBCT or MBSR, and (2) severe physical, psychiatric, or cognitive symptoms that hamper program participation. The study procedures complied with the institutional review board of Keio University School of Medicine, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Guideline for Clinical Studies of 2009 implemented by the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. The study was registered in the Japanese Clinical Trial Registry (registry ID: UMIN-CTR 000016142). The results of the original study were that the MBCT group experienced significantly greater improvement at the eighth week in their psychological distress, compared with the control group (the mean difference in the HADS total score of 7.82, with 95% CI of 11.28–6.35; p < 0.001), with an effect size of Cohen's d = 1.17. The difference remained significant at 12 weeks.

MBCT program

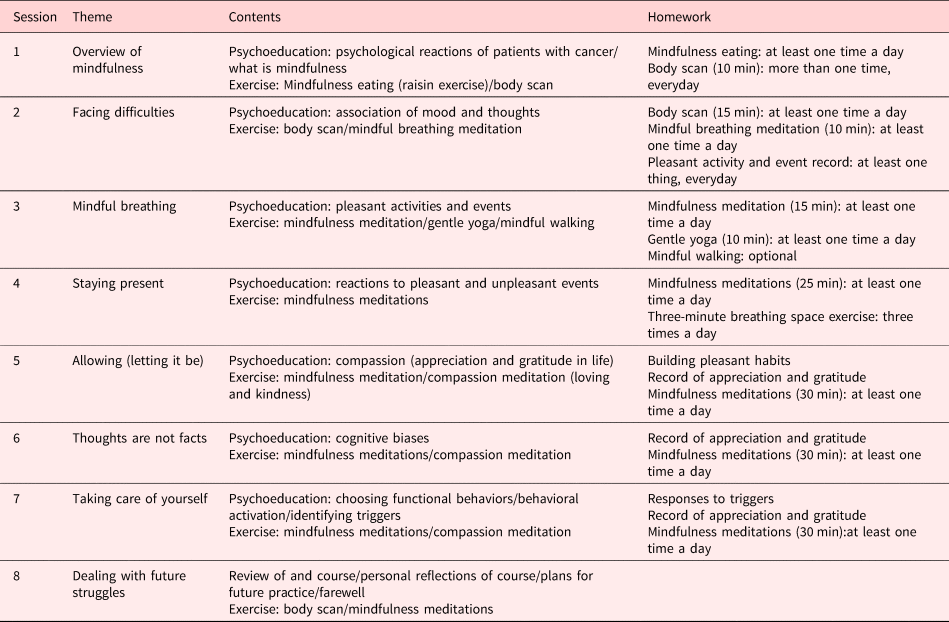

Our MBCT program consisted of eight 2-h sessions based on the MBCT manual by Segal et al. (Reference Segal, Williams and Teasdale2002). The program was delivered weekly in a group format with four to nine participants per group. A follow-up session was held four weeks later. The program included psychoeducation, formal and informal meditation practices, group discussion among participants, and homework that corresponded to the contents of each session. The details of the program are shown in Table 1. Based on the results of the feasibility study (Park et al., Reference Park, Sado and Fujisawa2018), some of the content was modified to fit Japanese cancer patients (Park et al., Reference Park, Sato and Takita2020). For example, brief psychoeducation was added to the first session, and the exercise of “finding difficulties” was changed to mindfulness meditation in the fifth session. An audio CD with meditation instruction and homework checklists were handed to the participants.

Table 1. MBCT program components

Assessment

The following self-report questionnaires were administered by the participants.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): The HADS is a 14-item self-administered questionnaire that measures severity of psychological distress (anxiety and depression) by seven items each (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983). Scores for each sub-scale range from 0 (no anxiety and/or depression) to 21 (maximum anxiety and/or depression). The higher score indicates more severe level of psychological distress.

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G): The FACT-G was used to evaluate the participants’ QOL (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Cella and Mo1997). This widely used questionnaire consists of 27 items, comprising four subscales: physical (score range 0–28), social/family (0–28), emotional (0–24), and functional well-being (0–28). The higher score indicates better QOL.

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp): The FACIT-Sp is a 12-item self-administered instrument to assess spiritual well-being. The instrument comprises two subscales — one measuring a sense of meaning and peace and the other assessing the role of faith in illness (Peterman et al., Reference Peterman, Fitchett and Brady2002). The higher score indicates better spiritual well-being.

The Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI): The BFI evaluates the participants’ fatigue (Okuyama et al., Reference Okuyama, Akechi and Kugaya2000). The BFI is a validated measure that consists of 10 items. The higher scores indicate more intense fatigue.

The Concerns about Recurrence Scale (CARS): The CARS evaluates the participants’ fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) (Momino et al., Reference Momino, Akechi and Yamashita2014). The CARS has been validated in measuring FCR in patients with breast cancer. In our original study, the subscale of overall FCR (four items) was used to lessen the burden of the participants to administer. Higher scores indicate a greater level of FCR.

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ): The FFMQ is a 39-item self-administered questionnaire that measures five domains of mindfulness skills — observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reacting with inner experience (Baer et al., Reference Baer, Smith and Lykins2008). The higher score indicates a greater level of mindfulness tendency. This scale was used as a process measure of the intervention — to measure whether the participants has taken up mindfulness skills.

The primary outcome was the HADS and was administered at baseline (pretreatment), after the intervention (eighth week), and at the end of each session. Other questionnaires were administered at baseline and after the intervention (eighth week).

The participants also reported time spent on the homework during the previous week of the session. Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected from the electronic health record.

Definition of remitter and responder

We divided the participants into remitters and non-remitters, and responders and non-responders. The definition of the remitters was the participants whose HADS total score after the intervention (eighth week) was 10 or lower. This is based on the past study that demonstrated that the HADS total score of 10/11 was an optimal cutoff score for screening cancer patients with high psychological distress (adjustment disorder or major depressive disorder) (Akizuki et al., Reference Akizuki, Akechi and Nakanishi2003). The definition of the responder was the participants whose HADS total score reduced by 50% or more at the eighth session from the baseline. We adopted the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) method if participants were absent from the eighth-week assessment.

Statistical analysis

To examine the factors associated with treatment response and remission, we conducted bivariate analysis using the chi-square test for categorical variables, t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables with skewed distribution. Then, we entered the following variables into logistic regression analysis: age, history of education, time since diagnosis, QOL, HADS total score at baseline, and treatment adherence. These variables were selected based on the past studies that demonstrated their possible association with treatment response (Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017; Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Crane and Parsons2017; Tovote et al., Reference Tovote, Schroevers and Snippe2017), and based on our hypotheses that patients who are at medically stable conditions (with longer time since diagnosis and better QOL) are more likely to benefit from MBIs. Considering high collinearity (r=0.691, p<0.001), we chose the number of class attendance instead of minutes spent for homework for logistic regression analysis to represent treatment adherence.

To estimate optimal dosage of MBCT, we performed generalized estimating equations (GEE) using a model with logit link and binominal distribution to examine when patients start to respond or reach remission over time. The working correlation matrix was specified to be compound symmetry. The significance levels for all the tests were two-sided at 5%. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0.0.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

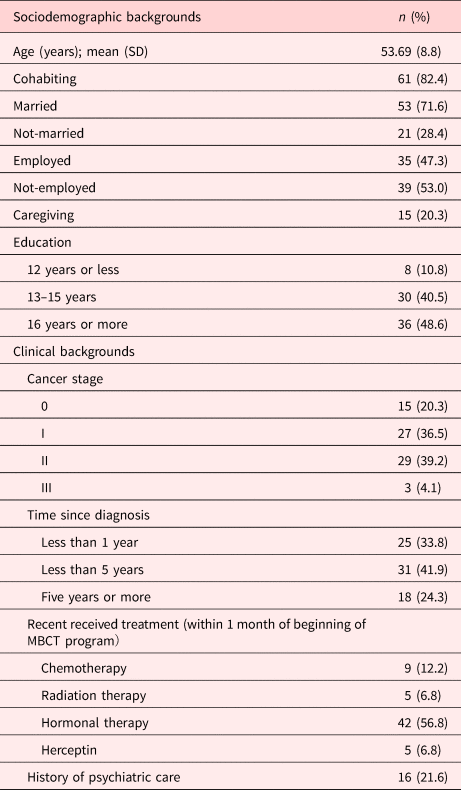

The participants’ characteristics are shown in Table 2. The mean age of the participants was 53.69 (SD = 8.79). All of them were female. Approximately one third of them were within 1 year since diagnosis, and one fourth were over 5 years. The participants who received chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal-therapy within 1 month before the program began were 12.2% (n = 9), 6.8% (n = 5), and 43.2% (n = 32), respectively.

Table 2. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants

Data are presented as n (%) unless indicated otherwise.

MBCT, mindful-based cognitive therapy; SD, standard deviation.

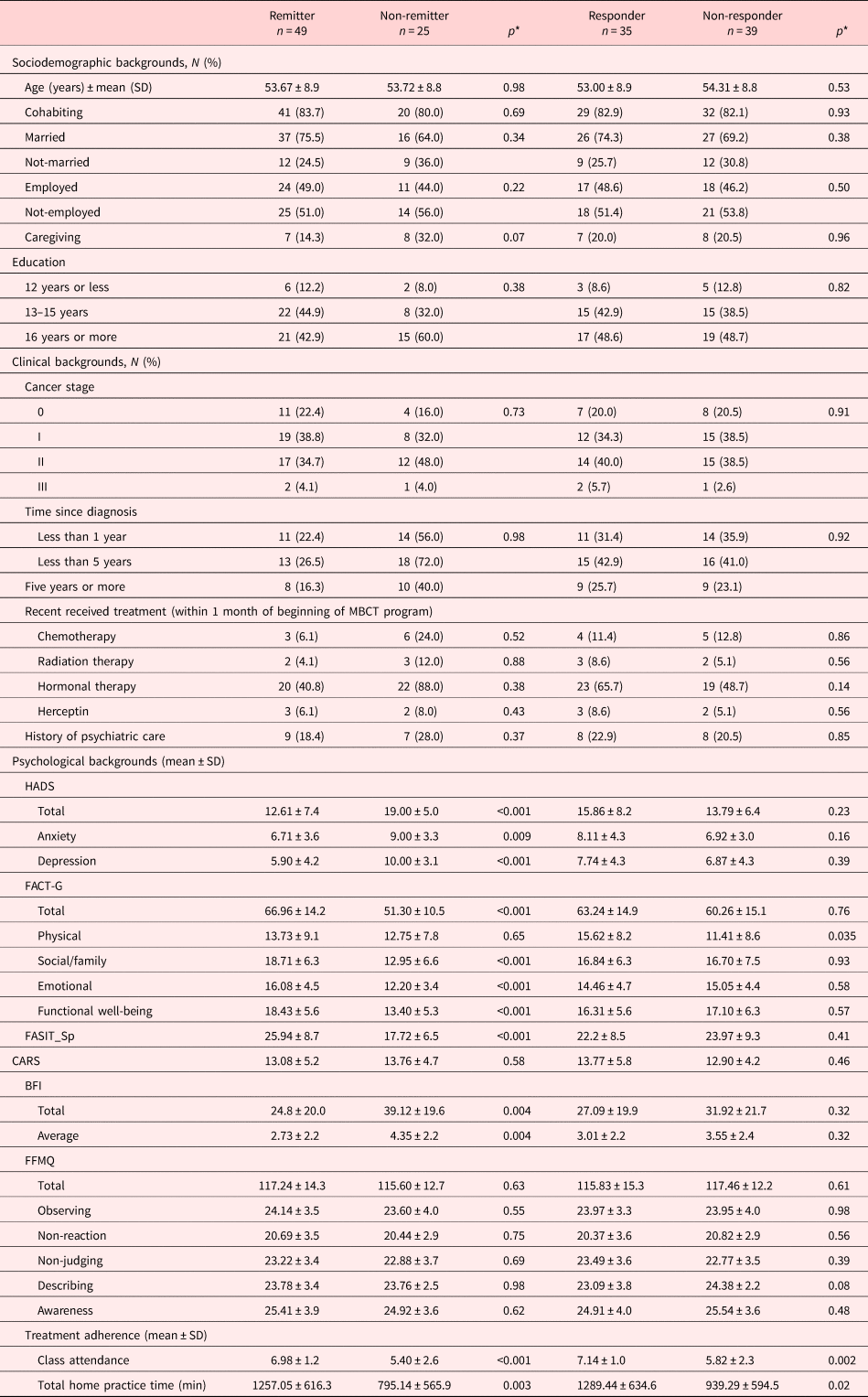

Bivariate analyses

The results of the bivariate analyses are shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in any of the sociodemographic and clinical variables. Patients who reached remission had lower levels of anxiety, depression, recurrent anxiety, sense of fatigue, and better QOL at baseline. Patients who responded to MBCT had better QOL compared with non-responder at baseline. Mindfulness tendency (the total score of FFMQ) was not significant. The participants who attended the program more frequently and who did their homework more intensely were more likely to experience remission and better treatment response.

Table 3. Results of the bivariate analyses

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; FACIT-Sp, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual; CARS, Concerns about Recurrence Change; BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; FFMQ, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.

* p: significance level. 95% confidence interval, both side.

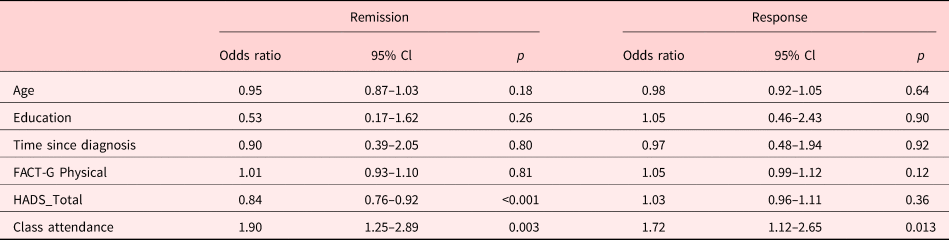

Multivariate analysis

The results of multivariate analyses are shown in Table 4. The HADS total score at baseline and class attendance were significant predictor for remission (HADS total score; odds ratio (OR) = 0.84, p < 0.01 [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 0.76–0.92], and class attendance; OR = 1.91, p < 0.01 [95% CI, 1.26–2.89]). Only the class attendance remained significant as a predictor for treatment response (OR = 1.71, p < 0.05 [95% CI, 1.12–2.63]).

Table 4. Results of multivariate analysis

FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Initial treatment reaction

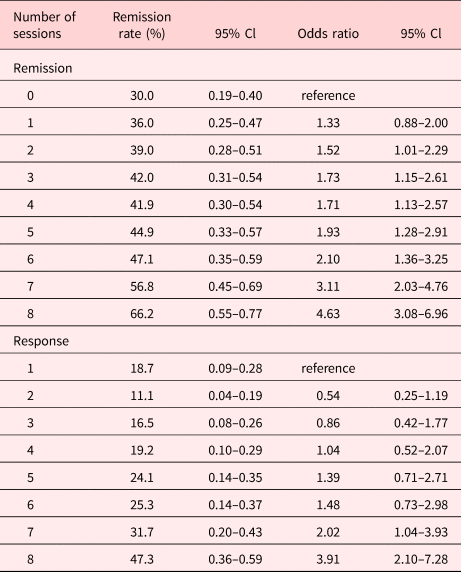

Proportions of patients who reached remission and response at each session are shown in Table 5. More than 50% of patients remitted at the seventh session. The significant difference in the treatment response was observed at the seventh session.

Table 5. Results of initial treatment reaction

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the characteristics of patients who benefit from MBCT and explore the initial treatment reactions to see the optimal number of sessions that produce significant effects.

There was no significant difference in the sociodemographic and clinical backgrounds between the patients who did and did not experience either remission or response. The patients with lower level of psychological distress at the baseline were more likely to experience remission. The better program adherence had a positive influence on both remission and response. Concerning the initial treatment reaction, 50% of the participants reached remission at the seventh session and there was significant difference in treatment response at the seventh session.

Past studies on MBIs have identified no definite sociodemopraphic predictors for treatment outcomes of MBIs, except that female gender is a predictor for better treatment outcome (Nyklicek et al., Reference Nyklicek, van Son and Pop2016). In a comparative study of MBCT and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes, patients with higher educational history were more likely to benefit from MBCT compared with CBT. However, influence of educational history was not significant in a within-group analysis of MBCT (Nyklicek et al., Reference Nyklicek, van Son and Pop2016). The current study yielded similar findings that educational history did not influence theeffectiveness of MBCT.

In the current study, lower levels of psychological distress at baseline served as a predictor for remission but not for treatment response. While some of the past studies indicated that lower levels of psychological distress at baseline predicted better treatment response (Trompetter et al., Reference Trompetter, Bohlmeijer and Lamers2016), the majority of the past studies denied significant association between the levels of psychological distress at baseline and treatment response (Gilpin et al., Reference Gilpin, Keyes and Stahl2017; Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017; Tovote et al., Reference Tovote, Schroevers and Snippe2017).

In contrast, a systematic review on the association of patients’ mindfulness practice and treatment outcome demonstrated that better adherence to the treatment, which is represented as time spent on homework, consistently predicts better treatment outcome (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Crane and Parsons2017). The current study was consistent with those results. Homework is an important component of psychotherapy that brings its effect to the real world (Addis and Jacobson, Reference Addis and Jacobson2000). Those who do their homework properly have been shown to gain better effect in treatment than otherwise (Burns and Spangler, Reference Burns and Spangler2000; Kazantzis et al., Reference Kazantzis, Deane and Ronan2000, Reference Kazantzis, Ronan and Deane2001; Kazantzis and Lampropoulos, Reference Kazantzis and Lampropoulos2002). In MBIs, the past studies showed that time spent on meditation affects brain changes (Ricard et al., Reference Ricard, Lutz and Davidson2014; Kral et al., Reference Kral, Schuyler and Mumford2018). It has also been suggested that meditating more time was associated with improved meditation quality and that improved meditation quality functioned as a mechanism linking meditation practice time and psychological outcomes (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Knoeppel and Davidson2020).

Systematic reviews demonstrated that shortened MBI programs yields smaller effect size than standard MBIs (Creswell, Reference Creswell2017; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Sekelja and Frasca2018; Cillessen et al., Reference Cillessen, Johannsen and Speckens2019). In the current study, it was not until seventh session that statistically significant improvement in the patients’ psychological distress was observed. Also, it was not until seventh session that more than half of the participants achieved remission. The standard dosage of MBCT (eighth sessions) seems desirable to attain clinically significant effect.

The current study indicated that simply making the MBCT shorter would not yield clinically significant effects on patients with cancer. The number of class attendance was also a significant factor in remission and treatment response. Since MBIs include meditation and various other elements (Britton et al., Reference Britton, Davis and Loucks2018), dismantling studies to examine active ingredients may be meaningful in the field of oncology.

There was some anecdotal evidence that doing homework and class attendance contributed to the improvement in the participants’ wellbeing. The following are some excerpts from the participants’ comments at the end of the program: “I was able to understand it little by little because of the homework.”, “At first, the homework was a real hassle. But I managed to do it because I felt good when I did it.”, “Meditations helped relaxing my mind and body. As I continued to meditate, I felt more comfortable.”, “I could feel my own mind changing with each session.”.

Clinical implications

In our study sample, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics did not significantly influence the treatment outcomes, while homework minutes and class attendance had significant effects on treatment outcomes. This implies that MBCT is recommended to any cancer patient, if he/she is motivated to the program, regardless of their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Patients are encouraged to attend a standard MBCT program and do the assigned homework as intensely as possible.

Since it was not until seventh session that more than half of the participants achieved remission. The standard dosage of MBCT (eight sessions) seems desirable to attain clinically significant effect.

Limitations

The current study has some limitations. First, the study was a single-center study with relatively small number of participants. The patients with advanced cancer were excluded. Thus, its generalizability is limited. Also, due to small sample size, we were not able to examine the influence of patients’ clinical background and the severity of psychological distress on the number of sessions that are needed to attain remission. Second, all the assessments were self-reported, thus lacks objectivity. Third, substantial proportion of the participants corresponded to remitters, since we defined remission with the HADS score of 10/11, while we screened potential participants with the HADS score of 5/6. Fourth, we did not examine personality characteristics, although they have been identified as predictors in two studies that addressed cancer patients (Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017; Jagielski et al., Reference Jagielski, Tucker and Dalton2020). This is because our study had been conducted before these findings came out. Fifth, we were not able to examine the influence of radiation therapy, which had been shown to associate with patients’ adherence to MBCT (Johannsen et al., Reference Johannsen, O'Toole and O'Connor2017), due to small number of participants. Finally, since our study employed wait-list control and did not adopt psychological placebo, we cannot exclude the influence of nonspecific effect of group psychotherapy.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides some suggestions on implication of MBCT for patients with cancer. Furthermore, multi-center study with larger study sample and objective measurement is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Teppei Kosugi, Dr Atsuo Nakagawa, Dr Maiko Takahashi, and Dr Tetsu Hayashida for their support to the implementation of the study.

Author contributions

D.F. conceived and designed the study. S.P. and N.T. collected the data. Y.S. and N.T. analyzed the data. N.T., S.P., and D.F. have full access to all of the data, and N.T. and D.F. take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. N.T. drafted the manuscript. M.S., A.N., D.F., and S.P. drafted the grant proposal. Y.S., Y.T., M.M., and all other authors critically reviewed the manuscript for content and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research; Grant Nos JP15K09875 and JP18K07476), Keio Gijyuku Academic Development Funds, and AMED under Grant No. JP20Ik0310059.

Conflict of interest

All authors except M.M. have no conflicts of interest. M.M. has received grants and/or speaker's honoraria from Asahi Kasei Pharma, Astellas Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Fuji Film RI Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kracie, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novartis Pharma, Ono Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Takeda Yakuhin, Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharma, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin within the past 3 years. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.