Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death globally among adolescents and young people aged 15–29 years, after road traffic accidents, tuberculosis, and interpersonal violence (World Health Organization, 2021). Although rare in childhood, suicide rates increase from puberty until early adulthood. While cross-national youth suicide mortality rates are heterogeneous, recent meta-analytic studies (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Kleiman, Kellerman, Pollak, Cha, Esposito, Porter, Wyman and Boatman2020) and reviews (Roh et al., Reference Roh, Jung and Hong2018) estimate a pooled suicide rate of approximately 3.8 per 100,000 persons for youth aged 10–19 years across all ages, sexes, and countries. As occurs in general suicide data across all age groups, the pattern in the youth population is for more suicide attempts among females (three to nine times more), whereas males show higher rates of completed suicide (three to four times higher) (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Kleiman, Kellerman, Pollak, Cha, Esposito, Porter, Wyman and Boatman2020).

The most important predictor of completed suicide in youth is a history of suicide attempts (Gvion & Apter, Reference Gvion, Apter, O’Connor and Pirkis2016). Although attempted suicide has been associated with both suicidal thoughts and non-suicidal self-harm, the majority of young people who think about suicide or who engage in non-suicidal self-harm will not attempt to take their own life. However, research suggests that the risk of a suicide attempt is higher when the two factors present in combination. Mars et al. (Reference Mars, Heron, Klonsky, Moran, O’Connor, Tilling, Wilkinson and Gunnell2019a) found that approximately one in five adolescents (21%) who reported both suicidal thoughts and non-suicidal self-harm at age 16 subsequently attempted suicide, compared with just 1% of those who did not report either of these behaviors.

Mental disorders are another important risk factor for suicide in adolescence (Gili et al., Reference Gili, Castellví, Vives, de la Torre-Luque, Almenara, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Pérez-Ara, Lagares, Parés-Badell, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Marín, Soto-Sanz, Alonso and Roca2019). However, a recent study that examined lifetime suicide attempts across a wide range of age groups found that around 20% of individuals who attempted suicide did not meet the criteria for a prior psychiatric disorder (Oquendo et al., Reference Oquendo, Wall, Wang, Olfson and Blanco2024). Therefore, suicide risk screening should not be limited to the psychiatric population. It is also important to note that although suicidal behavior is transdiagnostic (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Franklin, Kearns, Lanzillo, Nock, O’Connor and Pirkis2016), one of the most consistent predictors of attempted suicide is capability, that is, the extent to which the individual feels capable of carrying out such an act (Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, Qiu and Saffer2017). Suicide capability may be considered in terms of acquired capability (e.g., previous self-harm); genetic disposition (e.g., heightened pain tolerance); and practical knowledge of and access to lethal means.

There is also considerable evidence linking substance use with an increased risk of suicide, and for any age group, acute intoxication often precedes a suicide attempt (Frenk et al., Reference Frenk, Bursztein, Apter and Wasserman2021). In young people, the use of alcohol (including binge drinking) while sad or depressed has been found to be a marker for suicidal behavior in individuals who had not previously reported suicidal ideation, and hence who may not be identified as at risk by suicide prevention strategies (Schilling et al., Reference Schilling, Aseltine, Glanovsky, James and Jacobs2009). It is suggested that adolescents may use psychoactive substances to bolster their courage to carry out a suicide attempt, and because intoxication can lead to impaired judgment and decreased inhibition, it may facilitate the transition from suicidal thoughts to action (Frenk et al., Reference Frenk, Bursztein, Apter and Wasserman2021).

In terms of family factors, epidemiological research has demonstrated a link between youth suicide and parental loss (whether through death, divorce, or abandonment), a parental history of mental disorders or suicide attempts, family conflict, and maltreatment (including sexual abuse) within the family (Ruch & Bridge, Reference Ruch, Bridge, Ackerman and Horowitz2022). There is also evidence that in comparison with adolescents who only report suicidal ideation, those who attempt suicide are more likely to have been exposed to self-harm in family or friends (Mars et al., Reference Mars, Heron, Klonsky, Moran, O’Connor, Tilling, Wilkinson and Gunnell2019b). It should also be noted that high rates of suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-harm have been reported among adolescents in residential care, a population in which previous maltreatment and/or neglect is a common experience (Muela et al., Reference Muela, García-Ormaza and Sansinenea2024).

Academic pressures and being the victim of bullying (whether in person or in the form of cyberbullying, sexting, etc.) have also been associated with suicide risk (Ruch & Bridge, Reference Ruch, Bridge, Ackerman and Horowitz2022). Similarly, youth from sexual and gender minorities, who are more likely to experience discrimination and harassment, are at greater risk of suicide in comparison with peers (Raifman et al., Reference Raifman, Charlton, Arrington-Sanders, Chan, Rusley, Mayer, Stein, Austin and McConnell2020).

Mass media may also exert a powerful influence on suicidal behavior in youth. Having reviewed the findings of meta-analytic studies into the association between suicidal acts and media reports of suicide, Westerlund and Niederkrotenthaler (Reference Westerlund, Niederkrotenthaler and Wasserman2021) concluded that the number of new episodes of suicide increased in line with the amount of publicity a suicide received, and that copycat behavior of this kind (referred to as the Werther effect) was more marked among adolescents than adults. Furthermore, the risk of copycat behavior was greater if the reported suicide concerned a famous person or celebrity, and also if the person exposed to the report presented risk factors for suicide and identified with the person who had taken their own life. Westerlund and Niederkrotenthaler (Reference Westerlund, Niederkrotenthaler and Wasserman2021) also suggest that sensationalist media reporting of suicides is more likely to lead to copycat behavior than are more objective, cautious, and respectful accounts of such events. They also point out, however, that reporting that focuses on positive coping with suicidal thoughts and the overcoming of suicidal crises (referred to as the Papageno effect) may have a preventive effect in relation to suicide attempts (Westerlund & Niederkrotenthaler, Reference Westerlund, Niederkrotenthaler and Wasserman2021).

While further research is needed with regard to the impact of internet use, the systematic review by Marchant et al. (Reference Marchant, Hawton, Stewart, Montgomery, Singaravelu, Lloyd, Purdy, Daine and John2017) concluded that there was sufficient evidence of a relationship between suicidal behavior in young people and high internet use, especially when this involved websites with self-harm or suicide content. However, the authors of the review also suggested a potential role for the internet in suicide prevention, insofar as it may reduce social isolation and be a means of providing informal crisis support or access to therapy online.

Although mental or substance use disorders and exposure to physical maltreatment are risk factors for suicidal behavior common to both genders (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Marín, Roca, Soto-Sanz, Vilagut and Alonso2019), a number of differences have also been observed. Disruptive behavior, hopelessness, parental separation/divorce, suicidal behavior in a friend, and access to lethal means are male-specific risk factors for suicide attempts (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Marín, Roca, Soto-Sanz, Vilagut and Alonso2019). Female-specific risk factors for suicide attempts are eating disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, being the victim of dating violence, depressive symptoms, interpersonal problems, and previous abortion (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Marín, Roca, Soto-Sanz, Vilagut and Alonso2019). Regarding death by suicide, male-specific risk factors are substance abuse, externalizing disorders, and access to lethal means (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Marín, Roca, Soto-Sanz, Vilagut and Alonso2019). Evidence is lacking regarding female-specific risk factors for suicide death.

Clearly, then, suicidal behavior in youth is a complex and multicausal public health problem that requires early detection and effective prevention strategies. A central strategy of comprehensive suicide prevention involves suicide risk screening, the purpose of which is to identify high-risk youths so they can receive appropriate intervention or treatment (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Loh and Goans2023). Unfortunately, elevated suicide risk among adolescents often goes undetected by parents, teachers, and healthcare providers (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Cwik, Van Eck, Goldstein, Alfes, Wilson, Virden, Horowitz and Wilcox2017; Singer et al., Reference Singer, Erbacher and Rosen2019). Consequently, routine suicide risk screening in schools has been proposed as a strategy for improving the identification of at-risk adolescents (Singer et al., Reference Singer, Erbacher and Rosen2019). A number of well-established instruments for identifying adolescents with an elevated risk for suicide are now available, including the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., Reference Posner, Brown, Stanley, Brent, Yershova, Oquendo, Currier, Melvin, Greenhill, Shen and Mann2011), the Paykel Suicide Scale (PSS; Paykel et al., Reference Paykel, Myers, Lindenthal and Tanner1974), the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (Horowitz et al., Reference Horowitz, Bridge, Teach, Ballard, Klima, Rosenstein, Wharff, Ginnis, Cannon, Joshi and Pao2012), and the Suicide Risk Screen (Hallfors et al., Reference Hallfors, Brodish, Khatapoush, Sanchez, Cho and Steckler2006). A common feature of these (and other) scales is their central focus on suicidal ideation, which is assumed to be an early indicator of emerging suicidal behavior. However, multiple lines of evidence suggest that suicidal ideation is an unreliable predictor of suicidal behavior. Meta-analyses have shown, for example, that suicidal ideation is only very weakly correlated with suicidal behavior (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman, Huang, Musacchio, Jaroszewski, Chang and Nock2017). Similarly, it has been found that over half of people who attempt suicide or die by suicide deny suicidal ideation when screened (Berman, Reference Berman2018). Several studies have also drawn attention to the highly variable and dynamic nature of suicidal ideation (Gratch et al., Reference Gratch, Choo, Galfalvy, Keilp, Itzhaky, Mann, Oquendo and Stanley2019; Kleiman et al., Reference Kleiman, Turner, Fedor, Beale, Huffman and Nock2017), with different facets of suicidal ideation operating on different timescales (Butner et al., Reference Butner, Bryan, Tabares, Brown, Young-McCaughan, Hale, Mintz, Litz, Yarvis, Fina, Foa, Resick and Peterson2021; Coppersmith et al., Reference Coppersmith, Ryan, Fortgang, Millner, Kleiman and Nock2023). Emerging research further suggests that many people who attempt suicide do not experience suicidal ideation as it has traditionally been operationalized and measured (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Thomsen, Bryan, Baker, May and Allen2022b; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Whiteside, Ludman, Pabiniak, Kirlin, Hidalgo and Simon2019; Wastler et al., Reference Wastler, Bryan and Bryan2022). As noted by Rudd (Reference Rudd2023), these issues highlight the need to develop different screening and assessment tools for different settings and populations that are based on different assumptions about the nature of suicide risk. Instruments that ask directly about suicidal ideation may therefore need to be supplemented (or even replaced) with other instruments that can measure other aspects of suicide risk.

In this regard, one instrument that has demonstrated considerable promise is the Suicide Cognitions Scale (SCS; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014), a self-report questionnaire designed to measure a range of beliefs and perceptions that increase vulnerability to suicidal behaviors. Several shorter variants of the SCS have since been developed and tested in a variety of clinical settings and populations: the 16-item SCS-Revised (SCS-R; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a), the 9-item SCS-Short Form (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Kanzler, Grieser, Martinez, Allison and McGeary2017), and the 6-item Brief SCS (Rudd & Bryan, Reference Rudd and Bryan2021). Across studies, higher scores on these scales discriminate patients who have previously attempted suicide from those who only have suicidal ideation (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014; Moscardini et al., Reference Moscardini, Pardue-Bourgeois, Oakey-Frost, Powers, Bryan and Tucker2023) or those with a history of non-suicidal self-injury (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014, Reference Bryan, Kanzler, Grieser, Martinez, Allison and McGeary2017), and they also prospectively predict future suicide attempts even among respondents who deny suicidal ideation (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014; Reference Bryan, Rozek and Khazem2020, Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a, Reference Bryan, Thomsen, Bryan, Baker, May and Allen2022b; Rudd & Bryan, Reference Rudd and Bryan2021). The SCS (or one of its variants) has been translated into multiple languages and validated in several international samples (Arafat et al., Reference Arafat, Saleem, Edwards, Ali and Khan2022; Gupta & Pandey, Reference Gupta and Pandey2015; Spangenberg et al., Reference Spangenberg, Glaesmer, Hallensleben, Schönfelder, Rath, Forkmann and Teismann2019), supporting its utility as a cross-cultural measure of suicide risk.

From a psychometric point of view, different factor structures have been tested for the SCS, providing support for unidimensional (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014, Reference Bryan, Thomsen, Bryan, Baker, May and Allen2022b), bidimensional (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014; Gupta & Pandey, Reference Gupta and Pandey2015), and tridimensional models (Ellis & Rufino, Reference Ellis and Rufino2015; Spangenberg et al., Reference Spangenberg, Glaesmer, Hallensleben, Schönfelder, Rath, Forkmann and Teismann2019). More recently, multiple analyses testing a bifactor solution, which allows items to load on a general factor as well as a specific factor, indicate that SCS items primarily measure an underlying latent variable (termed the suicidal belief system) but also measure more specific cognitive styles such as unbearability and hopelessness (Bryan & Harris, Reference Bryan and Harris2019; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a; Moscardini et al., Reference Moscardini, Pardue-Bourgeois, Oakey-Frost, Powers, Bryan and Tucker2023; Spangenberg et al., Reference Spangenberg, Glaesmer, Hallensleben, Schönfelder, Rath, Forkmann and Teismann2019). These analyses suggest that the SCS is best scored and interpreted as a unidimensional measure.

Despite the accumulating evidence supporting the SCS and its variants, no version of the scale has so far been validated among adolescents. Furthermore, no version of the instrument has been translated into Spanish, the second most spoken first language in the world, with an estimated 475 million native speakers and another 74 million non-native speakers (Ethnologue, 2023).

A further and related issue to consider is that adolescents and youth in residential care have multiple risk factors for suicidal behavior, including childhood trauma, early signs of psychopathology or poor social adjustment, insecure attachment style, low self-esteem, poor social skills, risk behaviors, low social connectedness, and poor school integration (Muela et al., Reference Muela, Balluerka, Amiano, Caldentey and Aliri2017, Reference Muela, García-Ormaza and Sansinenea2024). In a comparison of young people in care and non-care populations, Evans et al. (Reference Evans, White, Turley, Slater, Morgan, Strange and Scourfield2017) found in the former a higher prevalence of both suicidal ideation (24.7% vs. 11.4%) and suicide attempts (3.6% vs. 0.8%). An earlier study by Pilowsky and Wu (Reference Pilowsky and Wu2006) similarly observed higher rates of attempted suicide (four times higher) among young people with a lifetime history of foster care. As regards completed suicide, research has found that the rate of death by suicide is between two and six times higher among young people with a history of care (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Au, Singal, Brownell, Roos, Martens, Chateau, Enns, Kozyrskyj and Sareen2011; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Boyle, Bethell, Wekerle, Goodman, Tonmyr, Leslie, Lam and Manion2012). These findings underline the need for reliable screening instruments for suicidal behavior.

Given these two key research gaps, the aim of this study was to develop a Spanish version of the 16-item SCS-R and to examine its psychometric properties in a sample of adolescents in residential care.

Method

Translation Procedures

Two independent translations of the SCS-R (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a) from English to Spanish were first carried out by two experienced bilingual clinical psychologists. After comparing the two translations, a first Spanish version of the scale was produced and submitted to a native English translator for back translation. Preliminary evidence of validity based on response processes was obtained using the cognitive interview method (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Chepp, Willson and Padilla2014) in a sample of 10 adolescents. While completing the questionnaire, participants were asked to verbalize their thoughts. Then, through a semi-structured interview, we gathered verbal information relating to the answers given during the completion of the questionnaire. By assessing the quality of responses in this way, it was possible to determine whether the items were measuring what they were intended to measure. Based on these results, adjustments to item wording were implemented, and a final version of the Spanish SCS-R was created (see Supplementary file).

Participants

The sample for analysis comprised 172 adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years (M = 15.32, SD = 1.57; 57% female, 41.8% male, 1.2% nonbinary) who were currently placed in residential care units in the Basque Country (northern Spain). The sampling procedure was incidental. Regarding nationality, 66.9% were Spanish. Of the 33.1% who were foreign nationals, 41.8% were originally from North Africa, 21.8% from South America, 7.3% from sub-Saharan Africa, 5.4% from Central America, and the remainder from countries in eastern and south-eastern Europe, the Caribbean, and Asia. For the total sample of adolescents, 40.1% were receiving psychiatric and pharmacological treatment for a diagnosed mental health problem.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the adolescents who took part in the study.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents (n = 172)

Instruments

Suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and non-suicidal self-injury

Lifetime suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and non-suicidal self-injury were assessed with the Adolescent Suicidal Behavior Assessment Scale (SENTIA; Díez-Gómez et al., Reference Díez-Gómez, Pérez-Albéniz, Ortuño-Sierra and Fonseca-Pedrero2020), a validated self-report tool that measures a range of suicide-related thoughts and behaviors in various timeframes. For the present study, we used three SENTIA items designed to assess lifetime experiences of suicidal ideation (“Have you ever had ideas about taking your life?”), suicide attempts (“Have you tried to take your own life?”), and non-suicidal self-injury (“Have you harmed yourself [self-injury: cuts, punctures, etc.] without intent to die?”). The SENTIA uses a dichotomous (yes/no) response format. Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) for scores on these items in the present sample was .95.

Suicide cognitions

The SCS-R (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a) is a 16-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure a range of beliefs, attitudes, expectations, and perceptions associated with the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (e.g., “Nothing can help solve my problems”). Respondents indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale the degree to which they agree or disagree with each item statement (range 0, strongly disagree to 4, strongly agree). Item responses are summed to provide an overall metric of the suicidal belief system, with higher scores indicating increased vulnerability to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Reliability of the SCS-R in the current sample is discussed in the Results section.

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Strine, Spitzer, Williams, Berry and Mokdad2009) consists of eight items (e.g., “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”) that assess the presence of depressed mood, anhedonia, sleep problems, fatigue, changes in appetite or weight, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, difficulty concentrating, and feelings of laziness or worry during the past two weeks. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (never) to 3 (almost every day). A score of 10 or above is frequently used as a cut-off point to identify patients with major depression. We purposely opted to use the PHQ-8 rather than the PHQ-9 as the ninth item in the latter assesses thoughts of death and self-harm, which might potentially have confounded the results. Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) of scores in the present sample was .84.

Mental pain

The Psychache Scale (PS; Holden et al., Reference Holden, Mehta, Cunningham and McLeod2001) consists of 13 items that assess mental pain and anguish (e.g., “I can’t take my pain any more”). Items 1–9 direct respondents to indicate how often they experience mental pain (e.g., “I feel psychological pain”) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), while their task on items 10–13 is to indicate how much they disagree or agree with statements reflecting mental pain (e.g., “I can’t take my pain any more”), using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Item scores are summed, with higher scores indicating more intense and frequent (i.e., less bearable) mental pain. Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) of scores in the present sample was .94.

Tolerance for mental pain

The Tolerance for Mental Pain Scale (TMPS; Orbach et al., Reference Orbach, Gilboa-Schechtman, Johan and Mikulincer2004) consists of 10 items that assess negative and positive perspectives of mental pain: feeling unable to manage one’s mental pain (e.g., “I cannot get the pain out of my mind”) and perceiving that one’s pain will not endure (e.g., “I believe that my pain will go away”). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 5 (very true). Higher scores on the manage subscale indicate reduced tolerance for mental pain, whereas higher scores on the endure subscale indicate stronger expectations that mental pain will resolve. Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) of scores in the present sample was .85.

Hopelessness

The Beck Hopelessness Scale–Short Form (BHS-SF; Yip & Cheung, Reference Yip and Cheung2006) consists of four items that measure the sensation of hopelessness during the last week (e.g., “My future looks dark to me”) using a true/false response option. Item scores are summed, with higher scores representing more severe hopelessness. Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) of scores in the present sample was .82.

Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belonging

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, Bender and Joiner2008) consists of 12 items that measure perceived burdensomeness (8 items; e.g., “These days, I feel like a burden on the people in my life”) and thwarted belonging (4 items; e.g., “These days, I feel disconnected from other people”), each rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not true for me at all) to 7 (very true for me). Item scores on each subscale are summed, with higher scores indicating more severe perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belonging. Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) of scores in the present sample was .85 for perceived burdensomeness and .74 for thwarted belonging.

Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Remor, Reference Remor2006) consists of 14 items that measure generalized distress during the past month (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”) using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Internal consistency (McDonald’s ω) of scores in the present sample was .83.

Procedure

We first contacted the regional child protection services to explain the purpose of the research, request their collaboration, and obtain approval to enroll adolescents in the study. After obtaining permission from the corresponding child protection services to carry out the study, as well as the consent of adolescents, we gathered sociodemographic data from the potential participants. Adolescents who met the inclusion criterion (aged 12–18 years) and agreed to participate completed a self-report survey packet in a private room within the care unit where they were residing. Data were collected individually via computer using a web-based survey. This approach was chosen for two reasons: first, because previous research indicates that online data collection is as reliable as face-to-face methods (Chandler & Shapiro, Reference Chandler and Shapiro2016), and second, it can be useful for assessing stigmatized behaviors such as suicide and self-harm, insofar as it minimizes the social desirability that can bias the results obtained through face-to-face and/or group test administrations (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Huang, Guzmán, Funsch, Cha, Ribeiro and Franklin2020). Although recent research suggests that asking young people about suicide does not increase their risk of suicide (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Huang, Guzmán, Funsch, Cha, Ribeiro and Franklin2020), we nevertheless took steps to ensure their emotional well-being. Specifically, a member of the care unit staff was available both during and after completion of the survey to offer emotional support as necessary. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 97/18) of the [masked for review].

Data Analysis

Multiple factor analyses were conducted to evaluate and compare the factor structure of the Spanish SCS-R, namely a unidimensional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), a two-factor CFA, and a bifactor model. All analyses were performed using Mplus 8.0 with the robust maximum likelihood estimator (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998). Because bifactor models tend to overestimate goodness of fit (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Hodge, Wells and Watkins2015), the following auxiliary measures were used to examine dimensionality and reliability: explained common variance (ECV), item-level ECV (I-ECV), proportion of uncontaminated correlations for a bifactor model (PUC), and average relative parameter bias. We also computed values of hierarchical omega (ωH), factor determinacy (FD), and construct replicability (H) for our bifactor models. Bifactor analyses were performed using the Bifactor Indices Calculator 0.2.2 package (Dueber, Reference Dueber2020) in R 4.3.1. Differential item functioning was analyzed using IRTPRO 6.0 (Thissen et al., Reference Thissen, Toit, Toit and Cai2023).

Concurrent validity was evaluated by calculating the correlation between SCS-R scores and scores on the PHQ-8, PS, TMPS, BHS-SF, INQ, and PSS-10. Construct validity was assessed via two Poisson regression models, comparing mean SCS-R scores across the following sample subgroups, created based on participants’ responses to the three SENTIA items (see Instruments): (1) participants with a history of suicide attempts, a history of suicidal ideation only, or neither; and (2) participants with a history of suicide attempts, a history of non-suicidal self-injury only, or neither. Validity analyses were conducted using SPSS 28.

Results

Item means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations are reported in Table 2. Overall, participants reported a moderate level of psychopathology, with 41.9% (female = 55.1%; male = 23.6%; nonbinary = 50%) reporting prior suicidal ideation; 56.4% (female = 71.4%; male = 34.7%; nonbinary = 100%) reporting prior non-suicidal self-injury; and 32% (female = 43.9%; male = 15.3%; nonbinary = 50%) reporting a prior suicide attempt. SCS-R scores did not correlate with age (r = 0.05, p = .571), but girls (M = 20.0, SD = 18.2) scored significantly higher than boys (M = 1.6, SD = 14.0; Wald χ2(1) = 167.3, p < .001; M diff = 8.3, 95% CI [7.1, 9.6], p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.53). Because only two participants identified as nonbinary, we were unable to conduct mean comparisons with this subgroup.

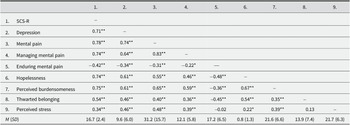

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of study variables

Note. **p < .01, ***p < .001.

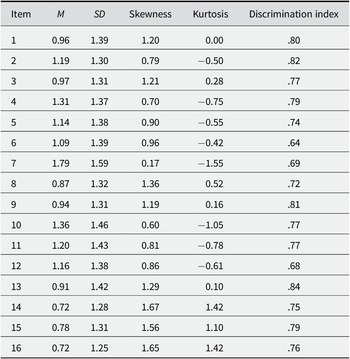

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics for SCS-R items in the total sample.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for SCS-R items

Factor Structure

Fit statistics for each factor analytic model are summarized in Table 4. The one- and two-factor CFA and the bifactor ESEM models did not achieve adequate fit. However, the confirmatory bifactor model with two specific factors showed a good fit, χ2(87) = 94.278, p > .05, TLI = .992, CFI = .994, RMSEA = .022, SRMR = .028, as did the exploratory bifactor model with two specific factors, χ2(75) = 77.551, p > .05, TLI = .997, CFI = .998, RMSEA = .014, SRMR = .021. The confirmatory and exploratory bifactor models did not differ meaningfully with respect to their fit indices, and most of the factor loadings for the specific factors in both bifactor models were low (i.e., < .30). Therefore, we used the confirmatory bifactor model with two specific factors for our subsequent analyses.

Table 4. Overall fit statistics for measurement models of the SCS-R

Note. SCS-R = Suicide Cognitions Scale–Revised; df = degrees of freedom; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis Index; SRMR = standardized root mean residual; RMSEA = root mean square error approximation; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; ESEM = exploratory structural equation modeling.

* p < .05.

Table 5 summarizes the ECV estimates for the SCS-R. The ECV was high (0.79), indicating that the common variance of the factors can be interpreted as unidimensional, as the general factor explained 79% of the variance in item responses. In addition, the values of ECVSpecific1 and ECVSpecific2 were 0.11 and 0.10, respectively, indicating that each specific factor explained only 11% and 10% of the common variance. The PUC value was low (.50) but the ωH value was high (.89), which indicates that the main source of variance is the common factor rather than the specific factors. According to Reise et al. (Reference Reise, Scheines, Widaman and Haviland2013), the combination of PUC values below .80, general ECV values above 0.60, and OmegaH above .70 suggest the presence of some multidimensionality, although it is not severe enough to disqualify interpreting the instrument as primarily unidimensional. The average relative bias across items was .095%, indicating that the item loadings of the bifactor model’s general factor and the item loadings of a unidimensional model differed by only 9.5%, which is within the acceptable range. Many of the items had I-ECV values above 0.80, indicating that they were predominantly influenced by the general factor. However, the items “No puedo soportar más este dolor” (“I can’t stand this pain any more”) and “No merezco vivir otro momento más” (“I don’t deserve to live another moment”) had lower I-ECV values, indicating they are good candidates for removal if greater unidimensionality is desired.

Table 5. Explained common variance (ECV), internal consistency (ω), construct replicability (H), and factor determinacy (FD) estimates for the SCS-R

Analysis of Differential Item Functioning

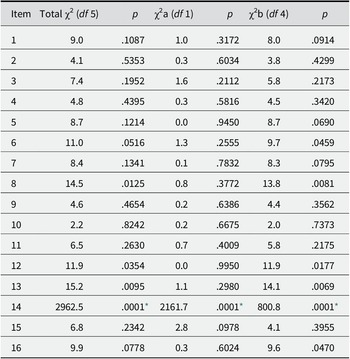

Table 6 shows the results obtained after exploring the presence of DIF for each item using the remaining items as anchors. The analyses suggested that item 14, “No merezco vivir otro momento más” (“I don’t deserve to live another moment”), was likely to present gender-based DIF. Specifically, the DIF analysis indicated that girls were more likely to score high (M = 0.82; SD = 1.32) on this item than were boys (M = 0.50; SD = 1.10), potentially confounding the interpretation of the scores obtained (Hidalgo et al., Reference Hidalgo, Galindo-Garre and Gómez- Benito2015). However, the DIF may reflect real gender differences in psychological factors related to this item (e.g., the perception of being a burden, hopelessness, feelings of guilt or blame, etc.). If so, it would indicate the presence of a factor of relevance to the suicidal belief system (the underlying construct), rather than a source of bias (Zumbo, Reference Zumbo2007). In this regard, it is important to note that eliminating item 14 did not alter the internal consistency of the scale (ω = .958), nor the significant difference between boys and girls in the SCS-R total score, t = 3.57; p < .001; neither did it significantly alter the magnitude of the effect size associated with the difference in means (change from d = 0.53 to d = 0.54: males, M = 11.3, SD = 13.1; females, M = 19.6, SD = 17.3). This suggests that any differences between boys and girls in scores on the SCS-R reflect genuine differences in their suicidal belief system, rather than bias related to item 14.

Table 6. Analysis of differential item functioning by gender. Wald test

Note. Total χ2 refers to the omnibus test for DIF, χ2a refers to the test for nonuniform DIF, and χ2b refers to the test for uniform DIF.

* p < .001.

A further issue to consider here is that DIF studies usually require large samples (i.e., more than 500 participants) to ensure precise estimates of DIF (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Alqassab, Bulut and Xiao2020). Given the relatively small size of the present sample, as well as the different numbers of boys and girls (72 vs. 98, respectively), we believe that the DIF results should be interpreted with caution. Consequently, and until further studies with larger samples can be conducted, we prefer to adopt a conservative stance and retain all 16 items in the Spanish version of the SCS-R.

Item Calibration

The graded response model was used to calibrate the items (GRM; Samejima, Reference Samejima1969). Item threshold parameters were distributed across a relatively broad range for the latent trait, from −0.43 (b 1 item 7) to 1.54 (b 4 item 12). The data in Table 7 indicate low levels of the trait in b 1s, medium levels in b 2s, high levels in b 3s, and even higher levels in b3s.

Table 7. GRM-estimated parameters for SCS-R items

Note. a refers to the slope parameter; b 1, b 2, and b 3 refer to the threshold parameters; and s.e. refers to the standard error.

As for the discrimination parameters (a), these presented values between 2.33 and 6.04. This indicates that the response categories are powerful in distinguishing between participants with different levels of suicidal beliefs, with their capacity to discriminate being very high across all items (Baker & Kim, Reference Baker and Kim2017).

Reliability Estimation of Scores

Table 5 also reports internal consistency, construct replicability, and FD estimates. Internal consistency was high for all SCS-R factors (ω > .92). The construct replicability value for the general factor was high (H = .96), indicating a well-defined latent factor, but was lower for each of the specific factors (H = .65 and .60), indicating they were not well-defined. Factor determinacy estimates were high for the general factor (FD = .97) and marginal for the two specific factors (FD = .90 and .86). This suggests that only the general factor should be scored, because it is recommended to only use factor score estimates when FD > .90. All the discrimination indexes were over .60 (see Table 3).

We also examined the accuracy of scores from an item response theory perspective. Table 7 shows specific values of the item and test information functions for certain levels of suicidal beliefs distributed along the trait continuum. Most of the items, as well as the whole test, show a higher level of information for medium and high levels of suicidal beliefs, while in turn the standard error decreases.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Scores on the SCS-R correlated with scores on other psychological variables in theory-consistent ways. Specifically, SCS-R scores showed 1) strong positive correlations (r values from .54 to .78) with scores on depression, mental pain, perceived inability to manage mental pain, hopelessness, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belonging; 2) a moderate positive correlation (r = .34) with perceived stress; and 3) a moderate negative correlation (r = –.42) with the perception that mental pain would end (Table 2).

Construct Validity

Scores on the SCS-R significantly differentiated between participants with a history of suicide attempts, of suicidal ideation only, and neither (Wald χ2(2) = 960.2, p < .001). Participants with a history of suicide attempts (M = 30.2, SD = 17.3) scored significantly higher than did participants with a history of suicidal ideation only (M = 26.1, SD = 18.8; M diff = 4.2, 95% CI [1.4, 6.9], p = .003; d = 0.24) and controls (M = 7.7, SD = 9.6; M diff = 22.5, 95% CI [20.9, 24.1], p < .001; d = 1.77). Participants with a history of suicidal ideation only also scored significantly higher than did controls (M diff = 18.3, 95% CI [16.0, 20.7], p < .001; d = 1.46).

Results also showed that SCS-R scores significantly differentiated between participants with a history of suicide attempts, of non-suicidal self-injury only, and neither (Wald χ2 (2) = 848.0, p < .001). Participants with a history of suicide attempts scored significantly higher than did participants with a history of non-suicidal self-injury only (M =16.9, SD = 16.3; M diff = 13.4, 95% CI [11.5, 15.3], p < .001; d = 0.80) and controls (M = 6.6, SD = 9.1; M diff = 23.7, 95% CI [22.0, 25.3], p < .001; d = 1.81). Participants with a history of non-suicidal self-injury only also scored significantly higher than did controls (M diff = 10.3, 95% CI [9.0, 11.6], p < .001; d = 0.83).

Discussion

In this study, we developed a Spanish version of the SCS-R and examined its psychometric properties in a sample of adolescents in residential care. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the SCS-R in adolescents. In the present sample, girls scored significantly higher than boys on the SCS-R, a finding that aligns with epidemiological data indicating that adolescent girls are more likely than their male peers to attempt suicide, with suicide attempt rates peaking in mid-adolescence for girls versus in early adulthood for boys (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., Reference Miranda-Mendizabal, Castellví, Parés-Badell, Alayo, Almenara, Alonso, Blasco, Cebrià, Gabilondo, Gili, Lagares, Piqueras, Rodríguez-Jiménez, Rodríguez-Marín, Roca, Soto-Sanz, Vilagut and Alonso2019). Regarding the psychometric properties of the SCS-R, factor analysis supported a bifactor structure, indicating that SCS-R items were primarily measuring a common underlying latent variable. Although some evidence for multidimensionality was observed, follow-up analyses indicated that when used with adolescents the SCS-R should be scored and interpreted as a unidimensional scale, rather than as a multidimensional scale. This mirrors previous findings in adults (Bryan & Harris, Reference Bryan and Harris2019; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a; Moscardini et al., Reference Moscardini, Pardue-Bourgeois, Oakey-Frost, Powers, Bryan and Tucker2023), suggesting that the SCS-R can be scored in the same way for both adolescents and adults.

The present results also reflect previous findings in several other ways. First, SCS-R scores were positively correlated with multiple indicators of psychopathology and other suicide risk factors (e.g., depression, hopelessness) but negatively correlated with protective factors (e.g., believing that one’s mental pain will eventually end). Second, these correlations with risk and protective factors for suicide were comparable in magnitude to those previously observed in adult samples (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014; Ellis & Rufino, Reference Ellis and Rufino2015). This suggests that the SCS-R is measuring a construct that is related to, but distinct from, other suicide risk factors. Third, SCS-R scores differentiated adolescents in residential care who had previously attempted suicide from those who had only thought about suicide. Scores also differentiated adolescents who had previously attempted suicide from those who had previously only engaged in non-suicidal self-injury. These results provide further evidence that the SCS-R measures a construct that distinguishes suicidal thought from action and is specific to suicidal forms of self-harm (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014, Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a; Bryan & Rudd, Reference Rudd2023). Taken together, these findings suggest that the SCS-R functions similarly among adolescents and adults. Additional research is warranted, however, to further evaluate the SCS-R among adolescents. In particular, studies employing longitudinal designs are needed to evaluate the scale’s prospective validity as an indicator of emerging suicidal behavior, especially as compared with commonly used methods for suicide risk screening, above all those that ask about suicidal ideation. Previous research has repeatedly found that the SCS-R is a better predictor of future suicidal behaviors than of suicidal ideation among adults (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Etienne, Ray-Sannerud, Morrow, Peterson and Young-McCaughon2014, Reference Bryan and Harris2019, Reference Bryan, May, Thomsen, Allen, Cunningham, Wine, Taylor, Baker, Bryan, Harris and Russell2022a; Bryan & Rudd, Reference Rudd2023). These results suggest the need for additional research focused on the scale’s prospective validity among adolescents. This research could advance the development and refinement of the SCS-R and other novel suicide risk screening and assessment methods that address the limitations of existing scales that rely on the self-disclosure of suicidal ideation.

Several limitations of the present study warrant discussion. First, our sample consisted solely of adolescents living in residential care units in northern Spain, and hence the results may not generalize to the broader population of adolescents. Second, the relatively small sample size limits statistical power and the possibility of generalizing the results obtained. A larger sample would also be necessary to confirm the results of the DIF analysis, which suggested that girls were more likely than boys to score high on item 14, “No merezco vivir otro momento más” (“I don’t deserve to live another moment”). Although girls’ total scores on the SCS-R remained significantly higher even after eliminating this item, the results should nonetheless be interpreted with caution pending further research. Third, although our methods in translating the SCS-R were rigorous, the existence of multiple dialects of Spanish across Spanish-speaking nations in North and South America could impact how respondents living in different parts of the world interpret and respond to the scale’s items. Additional research in different Spanish-speaking nations and cultures is therefore indicated. Finally, the use of a cross-sectional design limits our ability to determine if SCS-R scores prospectively differentiate adolescents who will eventually attempt suicide during various timeframes.

In conclusion, the Spanish SCS-R displayed strong psychometric properties as an indicator of suicide risk, supporting its potential utility as a way of identifying adolescents at risk of attempting suicide. It may also be a valuable tool for advancing suicide prevention research and prevention efforts among adolescents in residential care and in Spanish-speaking nations and cultures.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2024.30.

Data availability statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Author contribution

A. M.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. C. B.: Methodology, formal analysis, writing—review, and editing. J. G.-O.: Conceptualization, data curation, writing—review, and editing. K. S.: Resources, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing, and editing.

Funding statement

This research was funded by a grant from the Eusko Jaurlaritza (IT1450-22).

Competing interest

No conflict of interest to declare.