The Amak'hee 4 site was recorded during fieldwork in June 2018, along with 52 other previously undocumented rockshelters containing rock art. The site is located in the Swaga Swaga Game Reserve, in the Dodoma area of central Tanzania (Figure 1). Most of the paintings (97) from this site were made with a reddish dye; there are also five white images (Figure 2). Most are in good condition, mainly due to a rock overhang that protects them from flowing water and exposure to excessive sunlight. As there is currently no absolute dating of rock art from central Tanzania, it is difficult to specify the approximate age of the Amak'hee 4 paintings. Due to degradation of the dye and a lack of, for example, motifs depicting domesticated cattle, it can, however, be assumed that they belong to the hunter-gatherer period, so they are at least several hundred years old.

Figure 1. Map showing the locations of Amak'hee 4 and Kolo B1 and B2 rock art sites (map credit: ESRI Topo Word/QGIS).

Figure 2. General view of the paintings at Amak'hee 4 (photograph by M. Grzelczyk).

Approximately 50m from Amak'hee 4 is another shelter featuring white paintings (Amak'hee 3). This functioned as a family residence around 30–40 years ago, before the area was made into a game reserve. Along with the white paintings, Amak'hee 3 also contains modern drawings, probably made by children (these include a plane, a ball and an image of a politician). More than 30km north of Swaga Swaga is an area that was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2006 due to the presence of numerous rockshelters containing rock art. Their exact number is undocumented, but it is estimated at 300–400 (Bwasiri & Smith Reference Bwasiri and Smith2015: 441).

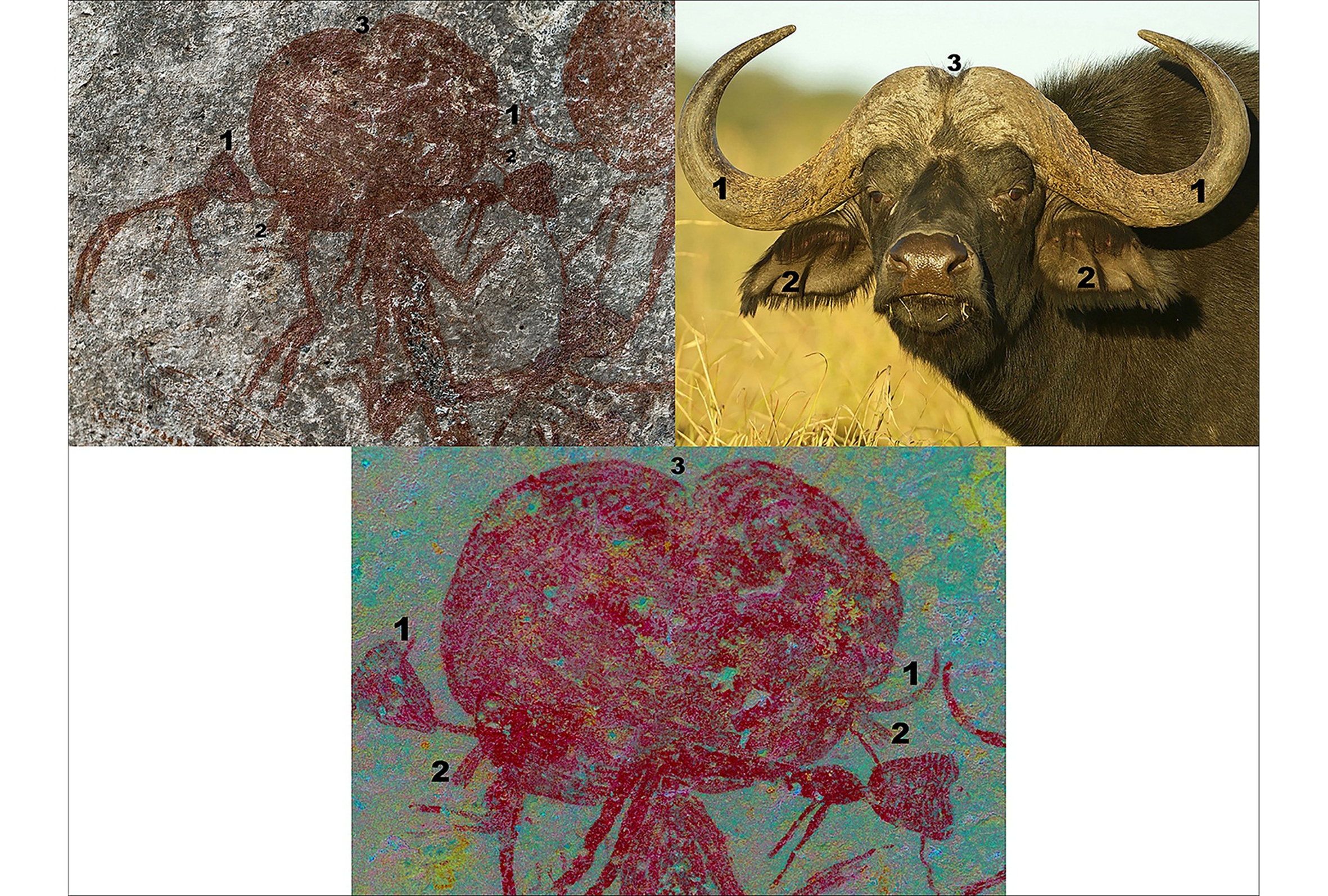

Particularly noteworthy among the Amak'hee 4 paintings is a scene that centres around three images (059, 066 and 080) (Figure 3). In this trio, the figures seem to feature stylised buffalo heads. These shapes recall the central dip in the profile of the buffalo head from where the two horns rise and then curve outward away from the head, as well as the downturned ears (Figure 4). Even though in the present religion of the Sandawe people—who are descendants of those who created the paintings—we find no elements of anthropomorphisation of buffaloes, nor belief in the possibility of transformation of people into these animals, there are some ritual aspects that offer parallels. The Sandawe still practise the simbó ritual, the main element of which is entering trance states; Lewis-Williams (Reference Lewis-Williams1987: 101) saw transformation into a lion as a possible motivation of the participants. One aspect of this ritual is the hitting of buffalo horns by women, while participants look for stones called kisango during the trance, the finding of which is a signal to complete the ritual. The kisango are then placed inside the horns “because they are such strong anti-witchcraft medicine” (Ten Raa Reference Ten Raa1967: 362). In the phek'umo ritual, related to fertility, women raise their hands in such a way that they symbolise “horns of the moon” and “horns of game animals” (Ten Raa Reference Ten Raa1967: 418).

Figure 3. Digital tracing of the Amak'hee 4 paintings (figure by M. Grzelczyk).

Figure 4. Comparison of the head of figure 059 (top left) and African buffalo (top right) and close-up of the digitally enhanced photograph (using DStrech) showing finer detail and superimposed layers (photographs by M. Grzelczyk and PAP/DPA).

The figures 059, 066 and 080 (Figure 3) form part of a coherent scene that includes smaller figures. The head of one of the smaller figures (057) appears to be speared by the horn of figure 059. Figure 059 also seems to be crushing figure 061 in its mouth (Figure 4). Based on the superimposition (Figure 5), it can be determined that the scene that includes the Amak'hee 4 trio was created from right to left. A notable aspect of the creation of this image is that while painting figure 059, the painter seems to have intentionally respected an existing figure (054) by not superimposing the new image onto it, thereby incorporating the existing image (054) into the new scene. The same technique can be seen in the buffalo painting (027), where the tail of the buffalo was interrupted in such a way that it would not superimpose on the leg of figure 054. On close inspection, figure 059 has pigment deficiencies in the middle of the torso, which were probably caused by someone deliberately scratching the pigment out.

Figure 5. Harris matrix showing correlations between the paintings of Amak'hee 4 (figure by M. Grzelczyk).

The motif of a trio of images is characteristic of other regional paintings, and is also observed in many depictions from the UNESCO Kondoa-Irangi sites (e.g. Kwa Mtea 1; see Leakey Reference Leakey1983a: 45). The closest parallels for Amak'hee 4, however, are images at the sites of Kolo B2 and B1, which were documented and described by Mary Leakey (Leakey Reference Leakey1983a & Reference Leakeyb). Paintings from Kolo B2 and B1 also have scenes that centre around three figures as the leading motif (Figure 6). The similarities between the scene from Amak'hee 4 and Kolo B1 & B2 do not derive from the drawing styles, but can be found in the arrangement of the figures’ hands, the positions of their bodies and the characteristic composition of the image with the figures in a line (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Comparison of the Amak'hee 4 (A), Kolo B2 (B) and Kolo B1 (C) trios (photographs by M. Grzelczyk).

While the paintings from Kolo B2 are presented in a vertical position, in the similar motif at Kolo B1, the figures are depicted horizontally. Leakey interpreted this to mean that “the [latter] trio must have been either captured or killed by enemies” (Leakey Reference Leakey1983b: 95). It is worth noting that some of the images from Amak'hee 4 were also painted horizontally and appear to be falling to the ground (063 and 066). This ‘falling’ movement can be seen at many rock art sites in Tanzania. The figures from Amak'hee 4 are noticeably bigger than those at Kolo, and make this main motif a central focal point around which the rest of the narrative seems to take place. In contrast, the images at Kolo are isolated depictions, with no clear connection to the rest of the paintings. The line running across the figures at Kolo is also reflected in the Amak'hee 4 rockshelter; it runs from the figure on the right and goes all the way across to the figure who seems to be leaning as if about to fall (066). One particularly notable feature of the images from Amak'hee 4 (059, 066 and 080) that is paralleled at Kolo is the arrangement and direction of the hands of the figures in the trio (Figure 6). It should be observed that other images from Amak'hee 4 also have a similar hand arrangement (e.g. 088 and 093).

Analogies also exist between the remaining paintings from Amak'hee 4 and those from other sites in central Tanzania. The giraffe's head and neck (001), for example, find similarities with an image at the Wakomaa site, while figures 012, 050 and 065 at Amak'hee 4 exhibit close similarities in terms of style to a figure from Cheke 3 (see Leakey Reference Leakey1983a: 84–85).

The paintings at the Amak'hee 4 rockshelter provide one example of the many rock art sites in the Swaga Swaga area that are locally known but unpublished. Further fieldwork surveys in this area will be carried out to add to the growing body of published data recording rock art sites in this region.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Emmanuel Bwasiri, the employees of the Swaga Swaga Game Reserve, the Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology (permit 2018-235-NA-2017-207) and the Antiquity Department (licence 08/2017/2018).

Funding statement

The research was funded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant 0123/DIA/2014/43).