Article contents

Dietary vitamin A intake recommendations revisited: global confusion requires alignment of the units of conversion and expression

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Commentary

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Authors 2017

References

Table 1 Amount of dietary retinol (μg) when expressed as retinol equivalents (µg RE) or retinol activity equivalents (µg RAE)

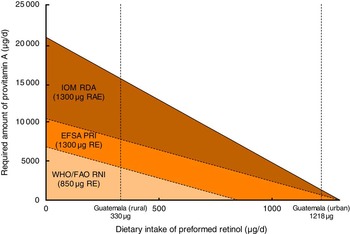

Fig. 1 Required amount of provitamin A intake for lactating women at each given preformed vitamin A intake to fulfil the recommended daily intake according to recommendations by the WHO/FAO, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM). Estimated intake of preformed vitamin A intake is 330 µg for rural Guatemalan lactating women and 1218 µg for urban Guatemalan lactating women(27). It is assumed that two-thirds of provitamin A intake comes from intrinsic β-carotene and one-third from other provitamin A carotenes in foods (RAE, retinol activity equivalents; PRI, Population Reference Intake; RE, retinol equivalents; RNI, Recommended Nutrient Intake)

Table 2 Vitamin A intake requirements and daily recommendations as advised by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the WHO/FAO and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

Table 3 Case example of estimated required provitamin A intake needed to fulfil the recommended daily intake for a lactating woman in rural Guatemala according to recommendations by WHO/FAO, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM)

- 9

- Cited by

In 1967, the FAO and the WHO proposed a unit of dietary reference values for vitamin A, retinol equivalents (RE), which designated 1 µg of preformed vitamin A in the retinoid form as 1 µg RE, and made considerations for a lower bioconversion efficiency for the provitamin A carotenoids as sources of the vitamin (Table 1)( 1 , 2 ). Based on compelling evidence that the absorption of provitamin A carotenoids, especially from dark green leafy vegetables, is much lower than previously assumed( Reference Micozzi, Brown and Edwards 3 – Reference van het Hof, Tijburg and Pietrzik 6 ), the Institute of Medicine (IOM; now called the Health and Medicine Division) concluded that higher bioconversion factors were more appropriate and formulated RDA values for vitamin A using microgram retinol activity equivalents (µg RAE) as the unit of reference in 2001( 7 ). This was later confirmed in follow-up studies( Reference Edwards, You and Swanson 8 – Reference van Loo-Bouwman, Naber and van Breemen 14 ), which largely corroborate the current IOM policy to estimate the bioconversion factors of β-carotene from an average Western diet as 12:1 and of other provitamin A carotenoids as 24:1 (Table 1). For low- and middle-income countries, West et al. (2002)( Reference West, Eilander and van Lieshout 15 ) suggested an even higher conversion factor for β-carotene, namely 21:1, based on studies conducted in Asia( Reference de Pee, West and Permaesih 16 – Reference Tang, Gu and Hu 18 ), which was later confirmed by other studies in other settings( Reference Haskell, Jamil and Hassan 19 , Reference Khan, West and de Pee 20 ). The difference in estimated conversion factors between low- and middle-income countries and Western countries can be explained by diet- and host-related factors such as food matrix, fat intake and health status( Reference West and Castenmiller 21 ).

Table 1 Amount of dietary retinol (μg) when expressed as retinol equivalents (µg RE) or retinol activity equivalents (µg RAE)

Following deliberations of micronutrient recommendations in Bangkok, Thailand in 1998, WHO/FAO published international guidelines, including those for vitamin A intake, in 2004, retaining the RE as the unit of reference( 22 ). In March 2015, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) updated the new European guidelines for vitamin A requirements and, surprisingly, opted to maintain the outdated conversion factors by keeping the RE as the unit of intake( 23 ) despite the growing evidence further supporting higher conversion factors over the last decade( Reference Haskell 24 – Reference Tang 26 ).

In the evaluation of adequacy of dietary vitamin A intake, two factors are important: (i) the absolute difference in recommended values between institutes; and (ii) the difference in units of expression. For lactating women, WHO recommends a daily intake of 850 μg RE, whereas IOM recommends 1300 µg RAE and EFSA recommends 1300 µg RE (Table 2). Although the latter two recommendations will be similar when all vitamin A from the diet is derived as the preformed vitamin, these will diverge greatly when a substantial part is derived from provitamin A sources. For example, we recently compared dietary vitamin A intake of Guatemalan urban- and rural-living pregnant and lactating women with their status-specific requirements( Reference Bielderman, Vossenaar and Melse-Boonstra 27 ). The mean intake of preformed vitamin A in the diet of lactating women from rural Guatemala was 330 µg, which was mostly derived from fortified sugar. Assuming that two-thirds of provitamin A intake from plant-based sources is in the form of all-trans β-carotene and one-third as other provitamin A carotenoids, these women ought to take in 4160 µg of provitamin A according to the WHO/FAO Recommended Nutrient Intake recommendation (850 µg RE), 7760 µg according to the EFSA Population Reference Intake recommendation (1300 µg RE) and 15 520 µg according to the IOM RDA recommendation (1300 µg RAE; Table 3). The lower the dietary intake of preformed vitamin A, the wider the gap between the specific recommendations series becomes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Required amount of provitamin A intake for lactating women at each given preformed vitamin A intake to fulfil the recommended daily intake according to recommendations by the WHO/FAO, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM). Estimated intake of preformed vitamin A intake is 330 µg for rural Guatemalan lactating women and 1218 µg for urban Guatemalan lactating women( Reference Bielderman, Vossenaar and Melse-Boonstra 27 ). It is assumed that two-thirds of provitamin A intake comes from intrinsic β-carotene and one-third from other provitamin A carotenes in foods (RAE, retinol activity equivalents; PRI, Population Reference Intake; RE, retinol equivalents; RNI, Recommended Nutrient Intake)

Table 2 Vitamin A intake requirements and daily recommendations as advised by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the WHO/FAO and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)

EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; RAE, retinol activity equivalents; MR, Mean Requirement; RE, retinol equivalents; RNI, Recommended Nutrient Intake; AR, Average Requirement; PRI, Population Reference Intake.

Table 3 Case example of estimated required provitamin A intake needed to fulfil the recommended daily intake for a lactating woman in rural Guatemala according to recommendations by WHO/FAO, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM)

RNI, Recommended Nutrient Intake; RE, retinol equivalents; PRI, Population Reference Intake; RAE, retinol activity equivalents.

Stipulated is that the daily intake of preformed vitamin A is 330 µg( Reference Bielderman, Vossenaar and Melse-Boonstra 27 ), that two-thirds of provitamin A intake comes from intrinsic β-carotene and that one-third comes from other provitamin A carotenes in foods.

Beyond these divergent recommendations, food composition tables also express total vitamin A and provitamin A content of foods as either µg RE or µg RAE. The US Department of Agriculture tables present both the preformed and provitamin A content of foods in RAE units( 28 ). Although devised for North America and expressed in the homologous vitamin A unit, the US Department of Agriculture tables are also used extensively in low- and middle-income countries where food composition tables are often lacking; these same countries, however, may be applying WHO requirement recommendations in RE units to assess adequacy. The same is true for European countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden, that have a food composition table based on RAE but are now confronted with EFSA recommendations expressed as RE. This mismatch in the units of comparison between ingested and required vitamin A intakes makes the assessment of adequacy of vitamin A intake complex, confusing and difficult to communicate.

We therefore urgently ask that an expert consultation be convened by WHO and FAO to review the evidence on bioefficacy of provitamin A carotenoids and implications for conversion factors from dietary carotenoids to retinol equivalents in order to re-establish: (i) units of measurement (expressed as retinol equivalent or retinol activity equivalent); (ii) mean requirements; (iii) Recommended Nutrient Intakes for preformed and provitamin A, based on differences in dietary pattern between populations; and (iv) food composition units of expression for preformed and provitamin A content. Revised conversion factors and intake recommendations could then be promoted for worldwide adoption, which would promote accuracy in assessment, a more uniform understanding and clarity in guiding populations globally towards a diet adequate in this essential nutrient.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None of the authors have a conflict of interest. Authorship: A.M.-B. wrote the initial draft; M.V. and N.W.S. provided the data for the calculations of the Guatemalan case study; all authors have contributed to follow-up versions and have approved the final content. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.