Over the course of evolution, lactobacilli, other lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and bifidobacteria have been abundant colonisers of the human small intestinal mucosa and coexist in mutualistic relationships with the host. Some members of these groups exert additional probiotic properties that provide health benefits to the host via the regulation of immune system and other physiological functions(Reference Konstantinov, Smidt and de Vos1, Reference MacDonald and Monteleone2).

The immune system can be divided into two systems: innate and adaptive. The adaptive immune response depends on B- and T-lymphocytes, which are specific for particular antigens. By contrast, the innate immune system responds to common structures, called pathogen-associated molecular patterns, which are shared by the vast majority of pathogens. The primary response to pathogens is triggered by the pattern recognition receptors that bind pathogen-associated molecular patterns; pattern recognition receptors comprise Toll-like receptors (TLR), nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domains, adhesion molecules and lectins(Reference McCole and Barret3).

The use of probiotics is considered to be a potentially important strategy for modulating infectious and inflammatory responses in the gastrointestinal tract of the host. The effect of these probiotics is diverse and includes the modulation of the gut immune system through the interaction with gut epithelial cells and immune cells. These interactions primarily involve gut-associated dendritic cells (DC), which have the capability to respond to microbial signals through TLR signalling(Reference Pamer4–Reference Goriely, Neurath and Goldman6).

For a micro-organism to qualify as a probiotic, it is essential to scientifically demonstrate that it is beneficial to the health of the host. Before testing probiotics in human subjects, a sine qua non condition is to conduct studies in cell and animal models. In vitro and animal studies may provide valuable information, such as the mechanism through which a probiotic acts, but these types of studies alone are not proof of the benefit of a putative probiotic to human health.

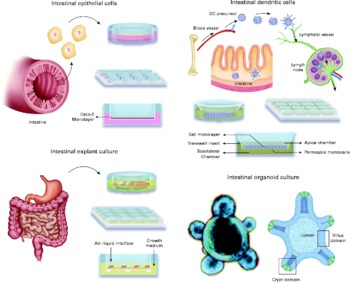

Intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) are a barrier between the intestinal lumen and host connective tissue. However, recent studies have demonstrated that IEC are involved in the immunological process of the discrimination between pathogenic and commensal bacteria. IEC also secrete a broad range of antimicrobial peptides, including defensins, cathelicidins and calprotectins. The IEC interact with subepithelial professional antigen-presenting cells that can sample antigens and micro-organisms and are mostly populations of DC and macrophage-associated lymphoid tissues. These subepithelial cells are able to polarise naıve T cells and produce an immunotolerance or an inflammatory response. The interaction of IEC, DC and macrophages with commensal or pathogenic bacteria stimulates the differential secretion of cytokines. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin and IL-10 are secreted by IEC in the presence of commensal or probiotic bacteria, whereas the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-8 and TNF-α are secreted when pathogenic bacteria are present(Reference Wallace, Bradley and Buckley7). DC can sample antigens directly from the intestinal lumen by forming tight-junction-like structures with IEC(Reference Rescigno, Urbano and Valzasina8); alternatively, DC can be stimulated by the cytokines secreted from IEC. An environment containing cytokines secreted by IEC and DC stimulates immature DC and macrophages to produce a further increase in the level of cytokines. The subepithelial naïve T cells are stimulated for immunotolerance or in response to a profile of inflammatory cytokines and promote the generation of Th1, Th2, Th17 or regulatory T cells (Treg). Because this complex net of secreted cells and cytokines is not easy to mimic in vitro, different models have been developed that principally involve IEC and DC generated from monocytes or segments of intestine (rat, human)(Reference Uematsu, Fujimoto and Jang9–Reference Smits, Engering and van der Kleij11) and T cells isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells(Reference Smits, Engering and van der Kleij11). Such models may include only one type of cell, a co-culture of various cell types or, in an effort to mimic the intestinal tissue, a culture of explants from the intestines(Reference Jarry, Bossard and Sarrabayrouse12). Often, the models determine the different cytokines secreted or distinguish between different subsets of DC or T cells using cell surface phenotypes or transcription factors that are specific for each cell type. Here, we review the cell and tissue models that are currently used or could potentially be used to ascertain the mechanism through which probiotics act (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Available in vitro models for studying host–microbe interactions and the mechanisms of action of probiotics. DC, dendritic cells.

In vitro models

Although human clinical trials are the definitive tool for establishing probiotic functionality, the use of in vitro models is necessary to select the most promising strains for these trials. Several in vitro studies evaluate the adhesion ability of potential probiotic bacteria and their interactions with pathogens at the intestinal epithelial interface(Reference Sanz, Nadal and Sánchez13–Reference Sánchez, Nadal and Donat15). The main goals of these studies are to understand the immunomodulatory effects of different bacterial strains on in vitro cell models and to evaluate whether the strain-dependent characteristics of commensal bacteria make them appropriate strains for the prevention and treatment of diseases.

A wide variety of cells are used as in vitro models for probiotic evaluation. Available models include both normal and carcinogenic cells of different origins (intestine and blood), species (human, rat, pig, calf, goat, sheep and chicken) and types (epithelial and monocyte/macrophage).

Intestinal epithelial cells

Three of the most widely used commercially available human cell lines are Caco-2, T84 and HT-29(Reference Fogh, Trempe and Fogh16, Reference Fogh, Fogh and Orfeo17), all of which were isolated from colon adenocarcinomas, express the features of enterocytes and are useful for attachment and mechanistic studies. In the differentiated state, these cell lines mimic the typical characteristics of the human small intestinal epithelium, including a well-developed brush border with such associated enzymes as alkaline phosphatase and sucrose isomaltase(Reference Lenaerts, Bouwman and Lamers18). The HT29-MTX is a cell line obtained from HT29 cells adapted to methotrexate(Reference Lesuffleur, Barbat and Dussaulx19), which differentiate into goblet cells and secrete mucin, although of gastric immunoreactivity(Reference Lesuffleur, Porchet and Aubert20, Reference Leteurtre, Gouyer and Rousseau21). Nevertheless, these three cell models are different from the small intestine in several aspects, and their phenotypes are dependent on the duration of the culture period(Reference Engle, Goetz and Alpers22, Reference Mehran, Levy and Bendayan23). Enterocytes and goblet cells represent the two major cell phenotypes in the intestinal epithelium, and IEC-6 and IEC-18 are the most widely used among the rodent cell lines(Reference Quaroni, Isselbacher and Ruoslahti24, Reference Quaroni and Isselbacher25). Both are commercially available and are derived from normal (non-carcinogenic) rat small intestine. Other available cell lines have been extensively reviewed by Cencič & Langerholc(Reference Cencič and Langerholc26).

The models of IEC are focused on studying the receptors of the innate immune system (TLR and nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)) and the pathways that result in the secretion of cytokines. Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Forsythe and Bienenstock27) showed that live Lactobacillus reuteri cells were able to reduce TNF-α-induced IL (IL-8) levels in Caco-2 cells. In addition, Vizoso Pinto et al. (Reference Vizoso Pinto, Rodriguez Gómez and Seifert28) showed that TLR9 and TLR2 were up-regulated when HT29 cells were incubated with lactobacilli but not when incubated only with Salmonella typhimurium. Using polarised HT29 and T84 cell monolayers, Ghadimi et al. (Reference Ghadimi, De Vrese and Heller29) demonstrated that apically applied DNA from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (a human commensal and probiotic bacteria) attenuated TNF-α-enhanced NF-κB activity by reducing the degradation of the inhibitor subunit α of NF-κB (IκBα) and p38 subunit mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation. In vitro studies have suggested that through the secretion of such immunoregulatory molecules as IL-8, TNF-α, TSLP, transforming growth factor-β and PGE2, IEC limit pro-inflammatory cytokine production in DC. Thus, the secretion of immunoregulatory molecules by IEC is important for the maintenance of intestinal immune homeostasis(Reference Wang and Xing30, Reference Dignass and Podolsky31).

Dendritic cells

DC comprise a complex, heterogeneous group of multifunctional antigen-presenting cells that comprise a critical arm of the immune system(Reference Steinman and Banchereau32–Reference Banchereau and Steinman35). DC differentiate into at least four lines: Langerhans cells, myeloid DC (MDC), lymphoid DC and plasmacytoid DC(Reference Wu and Liu36). These cells play critical roles in the orchestration of the adaptive immune response by inducing both tolerance and immunity(Reference Cools, Ponsaerts and Van Tendeloo37–Reference Steinman, Hawiger and Nussenzweig39). The present paradigm is that this dual role results from the division of the total DC population into a network of DC subsets having distinct functions(Reference Wu and Liu36, Reference Shortman and Naik40).

Immature DC reside in peripheral tissues, such as the gut mucosa, where they sense the microenvironment via pattern recognition receptors, including TLR and C-type lectin receptors, which recognise pathogen-associated molecular patterns(Reference Sabatté, Maggini and Nahmod41). Immature DC also release chemokines and cytokines to amplify the immune response(Reference Banchereau and Steinman35). Therefore, the regulatory role of DC is of particular importance at such mucosal surfaces as the intestine, where the immune system exists in intimate association with commensal bacteria, including LAB(Reference Stagg, Hart and Knight42). Probiotics exert differential stimulatory effects on DC in vitro, giving rise to varying production levels of different cytokines and, accordingly, different effector functions(Reference Christensen, Frøkiær and Pestka43–Reference Fink, Zeuthen and Ferlazzo45).

The response of the immune system to probiotics remains controversial. Some strains modulate the cytokine production by DC in vitro and induce a regulatory response, whereas others induce a pro-inflammatory response(Reference Evrard, Coudeyras and Dosgilbert46). These strain-dependent effects are thought to be linked to specific interactions between bacteria and pattern recognition receptors.

Braat et al. (Reference Braat, van den Brande and van Tol47) proposes that L. rhamnosus modulates DC function to induce a novel form of T-cell hyporesponsiveness, a mechanism that might be an explanation for the observed beneficial effects of probiotic treatment in clinical diseases.

The analysis of immature bone marrow-derived DC showed that all strains up-regulated the surface expression of B7-2 (CD86), which is indicative of DC maturation. However, the different strains up-regulated CD86 with varying intensities. No strain induced appreciable levels of IL-10 or IL-12 in immature bone marrow-derived DC, whereas TNF-α expression was elicited by Lactobacillus paracasei and Lactobacillus fermentum (Reference D'Arienzo, Maurano and Lavermicocca48) in particular.

Although efficiently taken up by DC in vitro, selected LAB strains induced only a partial maturation of DC(Reference Christensen, Frøkiær and Pestka43, Reference Foligne, Zoumpopoulou and Dewulf49). The transfer of probiotic-treated DC conferred protection against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid solution-induced colitis, and the preventive effect required Myeloid differentiation primary (MyD88)-, TLR2- and NOD2-dependent signalling and also the induction of CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells in an IL-10-independent pathway(Reference Foligne, Zoumpopoulou and Dewulf49).

Mohamadzadeh et al. (Reference Mohamadzadeh, Olson and Kalina50) investigated three species of Lactobacillus and found that they modulated the phenotype and function of human MDC. Lactobacillus-exposed MDC up-regulated human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR), CD83, CD40, CD80 and CD86 and secreted high levels of IL-12 and IL-18 but not IL-10. IL-12 was sustained in the MDC exposed to all three of the Lactobacillus species in the presence of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli, whereas lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-10 was greatly inhibited. The MDC activated with lactobacilli clearly skewed the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to T helper (Th) 1 and T cell 1 (Tc1) polarisation, as evidenced by the secretion of interferon (IFN)-γ but not IL-4 or IL-13.

L. reuteri and Lactobacillus casei, but not Lactobacillus plantarum, prime monocyte-derived DC to drive the development of Treg cells. The Treg cells then produce increased levels of IL-10 and are capable of inhibiting the proliferation of bystander T cells in an IL-10-dependent fashion. Strikingly, both L. reuteri and L. casei, but not L. plantarum, bind the C-type lectin DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin (DCSIGN). Blocking antibodies against DCSIGN inhibited the induction of the Treg cells by these probiotic bacteria, stressing that binding of DCSIGN can actively prime DC to induce Treg cells(Reference Smits, Engering and van der Kleij11).

All bifidobacteria and certain lactobacilli strains are low IL-12 and TNF-α inducers, and the IL-10 and IL-6 levels showed less variation than and no correlation with IL-12 and TNF-α. The DC matured by strong IL-12-inducing strains also produced high levels of IFN-β. When combining two strains, the low IL-12 inducers inhibited both this IFN-β production and the IL-12 and Th1-skewing chemokines. Weiss et al. (Reference Weiss, Christensen and Zeuthen51) demonstrate that lactobacilli can be divided into two groups of bacteria that have contrasting effects; conversely, all bifidobacteria exhibit uniform effects.

In conclusion, LAB potently initiate ‘interactions’ via DC maturation. Hence, these LAB strains may represent useful tools for modulating the cytokine balance and promoting potent type-1 immune responses or preventing the immune deregulation associated with specific T-cell polarisation(Reference Fink, Zeuthen and Ferlazzo45).

Macrophages

Lactobacilli have been shown to activate monocytes and macrophages, which play pivotal roles in antigen processing and presentation, the activation of antigen-specific immunity and the stimulation of IgA immunity. In particular, these cells are essential in the deviation of the immune response to the so-called type 1 response with cytotoxic effector cells or towards the type 2 response that is characterised by antibody production. The type 2 response is related to the secretion of IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13, which promote the induction of IgE and allergic responses. By incubating bacterial suspensions with THP-1 macrophage-like cells, Drago et al. (Reference Drago, Nicola and Iemoli52) analysed four strains of Lactobacillus salivarius for their ability to modulate the release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. LDR0723 and CRL1528 led to a sustained increase in the production of IL-12 and IFN-γ and a decrease in the release of IL-4 and IL-5; by contrast, BNL1059 and RGS1746 favoured a Th2 response, leading to a decrease in the Th1:Th2 ratio with respect to unstimulated cells.

Ivec et al. (Reference Ivec, Botić and Koren53) showed that probiotic bacteria, either from Lactobacillus sp. or bifidobacteria, have the ability to decrease viral infection by establishing the antiviral state in macrophages through the production of NO and inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IFN-γ.

Three-dimensional cell models and probiotics

Much of the present knowledge about how microbial pathogens cause infection is based on studying experimental infections of standard cell monolayers grown as flat two-dimensional cultures on impermeable glass or plastic surfaces. Whereas these models continue to contribute to the present understanding of infectious diseases, they are greatly limited because they are unable to model the complexity of intact three-dimensional (3D) tissue(Reference Abbott54, Reference Schemeichel and Bissell55). In addition, cells grown as standard two-dimensional monolayers are also unable to respond to chemical and molecular gradients in three dimensions (at the apical, basal and lateral cell surfaces), resulting in many departures from the in vivo behaviour(Reference Zhang56).

There are a variety of methods that have been used to enhance the differentiation of cultured cells, including permeable inserts, transplanted human cells grown as xenografts in animals and explanted human biopsies(Reference Nickerson, Richter and Ott57). Together, with animal experiments, organotypical cell cultures are important models for analysing the cellular interactions of the mucosal epithelium and pathogenic mechanisms in the gastrointestinal tract(Reference Bareiss, Metzger and Sohn58). Although these advanced in vitro models have provided important insights into microbial pathogenesis, they suffer from several limitations, including short lifetimes, labour-intensive design, experimental variability, availability and limited numbers of cells(Reference Nickerson, Richter and Ott57, Reference Höner zu Bentrup, Ramamurthy and Ott59).

Three-dimensional cell cultures and probiotics

Epithelial cells cultured in a 3D matrix self-assemble into polarised monolayers that separate central apical lumens from a basal environment containing extracellular matrix; therefore, these 3D epithelial culture systems allow key events in the life cycle of IEC, such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and migration, to be controlled in concert by organising principles that are determined by the spatial context of the cells. 3D culture systems mimic essential aspects of the in vivo organisation of epithelial cells of various origins. Compared with cell monolayers, the 3D culture of human intestinal cell lines (small intestine and colon) enhanced many characteristics associated with fully differentiated functional intestinal epithelia in vivo, including a distinct apical and basolateral polarity, the increased expression and better organisation of the tight junctions, extracellular matrix and brush border proteins and the highly localised expression of mucins. All of these important physiological features of in vivo intestinal epithelium were either absent or not expressed or distributed at physiologically relevant levels in monolayer cultures of the same cells(Reference Juuti-Uusitalo, Klunder and Sjollema60).

Recently, Mappley et al. (Reference Mappley, Tchórzewska and Cooley61) reported a study using a 3D culture model and probiotics. In in vitro adherence and invasion assays using HT29-16E 3D cells, the adherence and invasion of Brachyspira pilosicoli B2904 into epithelial cells were significantly reduced by the presence of the cell-free supernatants of two Lactobacillus strains, L. reuteri LM1 and L. salivarius LM2.

Tissue explants and probiotics

A limited number of studies used explants and probiotics, and all of these studies focused on intestinal diseases, particularly Crohn's disease.

Using an organ-culture model with intestinal mucosa explants and selected bacterial strains, Carol et al. (Reference Carol, Borruel and Antolin62) reported a decrease of activated T lymphocytes and TNF-α secretion by the inflamed mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. By favouring the apoptosis of T lymphocytes, L. casei may restore immune homeostasis in the inflamed ileal mucosa of these patients. In addition, Carol et al. (Reference Carol, Borruel and Antolin62) also demonstrated that some lactobacilli, such as L. casei DN-11 401 and L. bulgaricus LB10, may down-regulate inflammatory responses when exposed to inflamed mucosa in organ culture(Reference Borruel, Carol and Casellas63, Reference Borruel, Casellas and Antolín64). These authors conclude that probiotics interact with immunocompetent cells through the mucosal interface and locally modulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is important to note that, although this model is useful for studying whole tissue responses in Crohn's disease, it does not permit the investigation of signals between mucosal cells because mucosa explants include a great variety of cells in their natural disposition for cell-to-cell communication.

More recently, Mencarelli et al. (Reference Mencarelli, Distrutti and Renga65) cultured abdominal fat explants from five Crohn's disease patients and five patients with colon cancer (as controls) using VSL#3 (VSL Pharmaceuticals, Fort Lauderdale FL) medium and found that the exposure of these tissues to the VSL#3 conditioned medium abrogates leptin release. Thus, probiotics seem to correct inflammation-driven metabolic dysfunction.

Lastly, another group treated mouse colon epithelial cells and cultured colon explants with purified L. rhamnosus GG proteins in the absence or presence of TNF-α. Two novel purified proteins p75 and p40 activated protein kinase B (Akt), inhibited cytokine-induced epithelial cell apoptosis and promoted cell growth in human and mouse colon epithelial cells and cultured mouse colon explants. Furthermore, TNF-induced colon epithelial damage was significantly reduced. These findings suggest that probiotic bacterial components may be useful for preventing cytokine-mediated gastrointestinal diseases(Reference Yan, Cao and Cover66).

Future models

3D culture advanced in vitro models have provided important insights into microbial pathogenesis. However, they have several limitations, including short lifetimes, labour-intensive design, experimental variability, availability and limited numbers of cells. The development of novel relevant in vitro models of human intestinal epithelium, such as bioreactors and organoids, provides a viable starting point for future efforts aimed at bioengineering human intestine. 3D culture in bioreactors represents an easy, reproducible and high-throughput platform that provides a large number of differentiated cells. Another promising line is human pluripotent stem cells (PSC) that offer a unique and promising means to generate intestinal tissue, resulting in 3D intestinal ‘organoids’ formed villus-like structures and crypt-like proliferative zones. This intestinal tissue is functional, as it can secrete mucins into luminal structures.

Bioreactors

Tissue engineering represents a biology-driven approach by which bioartificial tissues are engineered through the combination of material technology and biotechnology. Bioreactors constitute and maintain physiological tissue conditions at desired levels, enhance mass transport rates and expose cultured cells to specific stimuli. It has been shown that bioreactor technologies providing appropriate biochemical and physiological regulatory signals guide cell and tissue differentiation and influence the tissue-specific function of bioartificial 3D tissues.

BioVaSc

BioVaSc is generated from a decellularised porcine small bowel segment with preserved tubular structures of the capillary network within the collagen matrix. BioVaSc is a prerequisite technique for the generation of bioartificial tissues endowed with a functional artificial vascular network. The technology has been performed in artificial human liver, intestine, trachea and skin models. These various human tissue models are a new technology that is an alternative to animal experiments for pharmacokinetic (drug penetration, distribution and metabolisation) and pharmacodynamic studies(Reference Schanz, Pusch and Hansmann67), and also to study probiotic interactions with the host.

Rotating-wall vessel bioreactor

Another alternative model utilises rotating-wall vessel technology to engineer biologically meaningful 3D models of human large intestinal epithelia and can be used in conjunction with the established models. Many reports have described the fact that cells cultured in an rotating-wall vessel bioreactor can assume physiologically relevant phenotypes that have not been possible with other models. In addition, 3D culture in rotating-wall vessel bioreactors represents an easy, reproducible and high-throughput platform that provides a large number of differentiated cells.

Optimally, the design of cell culture models should mimic both the 3D organisation and differentiated function of an organ, while allowing for experimental analysis in a high-throughput platform. Originally designed by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) engineers, the rotating-wall vessel technology is an optimised suspension culture design for growing 3D cells that maintain many of the specialised features of in vivo tissues(Reference Unsworth and Lelkes68, Reference Nickerson, Ott and Wilson69).

To date, several works have shown the use of 3D cell culture systems in infection studies with the following pathogens: S. typhimurium (small intestine and colon models)(Reference Höner zu Bentrup, Ramamurthy and Ott59, Reference Nickerson, Goodwin and Terlonge70), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (lung model)(Reference Carterson, Höner zu Bentrup and Ott71, Reference Crabbé, Sarker and Van Houdt72), human cytomegalovirus (placental model)(Reference LaMarca, Ott and Höner Zu Bentrup73) and Hepatitis C virus (hepatocyte model)(Reference Sainz, TenCate and Uprichard74). Additional studies with other 3D models and infectious agents are ongoing and include bacteria, viruses and parasites that are difficult or impossible to culture using conventional methods.

Organoids

Intestinal resection and malformations in adult and paediatric patients result in devastating consequences. Unfortunately, allogeneic transplantation of intestinal tissue into patients has not been met with the same measure of success as the transplantation of other organs. Attempts to engineer intestinal tissue in vitro include the disaggregation of adult rat intestine into subunits called organoids, harvesting native adult stem cells from mouse intestine and spontaneous generation of intestinal tissue from embryoid bodies(Reference Howell and Wells75). Recently, by utilising principles gained from the study of developmental biology, human PSC have been demonstrated to be capable of directed differentiation into intestinal tissue in vitro (Reference Spence, Mayhew and Rankin76).

PSC offer a unique and promising means to generate intestinal tissue for the purposes of modelling intestinal disease, understanding embryonic development and providing a source of material for therapeutic transplantation(Reference Howell and Wells75). For example, human PSC have been differentiated into monolayer cultures of liver hepatocytes and pancreatic endocrine cells(Reference Cai, Zhao and Liu77–Reference Zhang, Jiang and Liu80) that have therapeutic efficacy in animal models of liver disease(Reference Zhang, Jiang and Liu80–Reference Touboul, Hannan and Corbineau82) and diabetes(Reference Kroon, Martinson and Kadoya83), respectively.

Several authors have differentiated PSC from mice and human subjects into intestinal tissue. The resulting 3D intestinal ‘organoids’ consisted of a polarised, columnar epithelia that were patterned into villus-like structures and crypt-like proliferative zones that expressed intestinal stem cell markers. The epithelia contained the normal number of Lgr5-positive stem cells, Paneth cells and transit-amplifying cells in the crypt domain and the three differentiated cell lineages (enterocytes, goblet and enteroendocrine cells) of the villus domain(Reference Koo, Stange and Sato84). This intestinal tissue is functional, as it can secrete mucins into luminal structures(Reference Spence, Mayhew and Rankin76, Reference McCracken, Howell and Wells85). Furthermore, as based on defined growth factors and Matrigel, this well-established culture system retains critical in vivo characteristics, such as lineage composition and self-renewal kinetics(Reference Sato, Stange and Ferrante86).

However, despite offering such great potential, this system is not without its limitations. For example, the intestinal organoids lack several components of the intestine in vivo, such as the enteric nervous system and the vascular, lymphatic and immune systems. Additionally, whereas all of the major epithelial cell types are generated in proportions similar to those found in vivo, and there is evidence of crypt-like domains housing stem cells, the 3D architecture is not as regular as that seen in vivo, and the villus-like structures are variable from one organoid to the next(Reference McCracken, Howell and Wells85). Regardless of these drawbacks, this system has extraordinary experimental utility for understanding and modelling human intestinal development, homeostasis and disease. Moreover, this system provides a viable starting point for future efforts aimed at bioengineering human intestine.

Finally, Sato et al. (Reference Sato, Stange and Ferrante86) developed a technology that can be used to study infected, inflammatory or neoplastic tissues from the human gastrointestinal tract. Encouraged by the establishment of murine small intestinal cultures, these researchers adapted that culture condition to mouse and human colonic epithelia. However, long-term adult human IEC culture has remained difficult. Although there have been some long-term culture models, these techniques and cell lines have not gained wide acceptance, possibly as a result of the inherent technical difficulties in extracting and maintaining viable cells. These tools might have applications in regenerative biology through ex vivo expansion of the intestinal epithelia.

Conclusions

In most in vitro experimental models, epithelial cells are cultivated as monolayers, in which the establishment of functional epithelial features is not achieved. Compared with cell monolayers, the 3D culture of human intestinal cell lines enhanced many characteristics associated with fully differentiated functional intestinal epithelia in vivo. However, despite providing important insights, a number of limitations have to be taken into account, including short lifetimes, labour-intensive design, experimental variability, availability and limited numbers of cells.

Considerable effort has been invested in the development of new tools to study host–microbe interactions. Recent studies based on the ability to generate human intestinal tissues may help in understanding the molecular mechanisms of host–microbe interactions. Bioreactors and organoids provide a viable starting point for future efforts aimed at bioengineering human intestine. However, to date, these new approaches have also limitations that must be considered. For example, in organoids, the 3D architecture is not as regular as that seen in vivo and the villus-like structures are variable from one organoid to the next.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Part of the research currently in progress in our laboratory is funded by the company Hero España, S.A. through the grants no. 3143 and 3545 managed by the Fundación General Empresa-Universidad de Granada. The author contributions were as follows: L. F. and M. B.-B. wrote the abstract; J. P.-D., S. M.-Q. and L. F. wrote the introduction and the section ‘In vitro models’. M. B.-B. and A. G. wrote the sections ‘Three dimensional models and probiotics’, ‘Future models’ and ‘Conclusions’. J. P.-D. and S. M.-Q. made the figure.