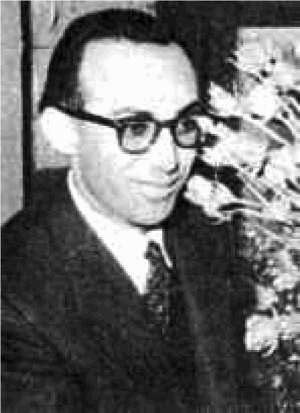

Fereydun Adamiyat, a prominent Iranian historian, died on 29 March 2008 in Tehran. He was born in Tehran on 23 August 1920 into a family that gained some prominence during the waning decades of the Qajar dynasty, which had ruled Iran since 1786. His father, Abbas-Qoli Khan Qazvini (d. 1939), who remained a source of inspiration for his son, was a civil servant and political activist. He had in the 1880s founded an influential political society, comprised of leading political figures, which sought to promote liberal ideas.

Adamiyat received his BA in 1942 from the School of Law and Political Science, Tehran University. His undergraduate thesis—reflecting, albeit implicitly, the imprint of the Allied occupation—would become the basis of his first, and perhaps most famous book, on the mid-nineteenth century reformist chief minister, Mirza Taqi Khan Amir Kabir. Adamiyat had joined the Iranian Foreign Ministry in 1940 while still an undergraduate, and was working as a secretary at the Iranian embassy in London when, in 1946, he enrolled at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He completed his doctorate in 1949.

At the LSE Adamiyat pursued his interest in political history and the history of ideas while concentrating on the study of diplomatic history. Under the supervision of Sir Charles Webster, he wrote a thesis on Persia's diplomatic relations with Britain, Turkey and Russia from 1815 to 1830. This research remained unpublished but his other work in English, a book entitled Bahrein Islands: A Legal and Diplomatic Study of the British–Iranian Controversy, was published in 1955. The intellectual milieu of the LSE, and more broadly the Labour-dominated Britain of the post-war years, left a deep mark on him. He was influenced most notably by two distinguished LSE socialists: the historian and reformist social critic R. H. Tawney, and Harold Laski, then a towering figure at the School.

During his diplomatic career, Adamiyat held a variety of important positions, including an eight year attachment to the Iranian delegation at the UN. From 1961 to 1965 he served as an ambassador, first to the Netherlands and then to India. Soon after, his disapproval of the direction of Iranian foreign policy precipitated his early retirement from the foreign ministry to devote himself entirely to historical scholarship.

An innovative historian, Adamiyat conceived of and promoted history as a specialized and analytical discipline. He made extensive use of Iranian and foreign archival sources, emphasized the need for searching out and relying on primary sources, classified them in order of significance, and revealed a remarkable command of them. His personal standing and public presence as a prominent intellectual, together with his characteristically self-assured and succinct prose style, ensured his work considerable attention. He came to be widely regarded as representing, if not pioneering, serious historical inquiry in Iran.

In over a dozen important works he trenchantly dealt with the modes of thinking, careers, aims, and achievements of the exponents of modern reformist thought and institutions in the Qajar era. With intellectual history emerging as his chief preoccupation, he sought to trace the pedigree of the broad seminal ideas that had influenced the modern urban literati. His focus on notions such as liberty also drew attention to their occlusion during the greater part of the Pahlavi era (1926–79). Adamiyat did not neglect movements of protest, and sympathetically studied Iranian social democratic trends, but as a cultural elitist he generally revealed little interest in the lower classes. For him, the Iranian constitutional revolution of 1906 was ideologically nourished by the intelligentsia, who advocated democratic governance and national sovereignty. By stressing the salience of modern secular thought in the revolutionary process, he intended to rebut a trend which emphasized the role of the clerics and the religious discourse, or sought to rehabilitate counter-secular ideas.

Although personally a man of impeccable manners, Adamiyat's impatience with the intellectual naiveté and simplistic generalizations of some contemporary attitudes to the past often made him a pugnacious writer. In his abhorrence of the degeneration of decorum into feigned humility, which he regarded as a barrier to rigor, courage and conviction, he showed little hesitation in bluntly denouncing what he perceived as fallacious or distorted. He was embittered by the persistence of authoritarian rule, the docility of the complicit elite, the fragmentation of the secular opposition, and the tenacity of the clerics’ ideological power. He rebuked those intellectuals who, ill-informed about the history of the quest for freedom in Iran, cast aspersions on it or opportunistically sided with anti-democratic forces.

Adamiyat was a staunch admirer of Enlightenment modernity and a nationalist fiercely critical of both Western imperial hegemony and Orientalism. A civic-nationalist in the Mosaddeqist tradition, he was politically and intellectually close to Gholam-Hosein Sadiqi—an eminent historical sociologist and minister in Mosaddeq's cabinet in the early 1950s—and briefly taught at Tehran University on Sadiqi's invitation. When, in the months preceding the fall of the monarchy, Mohammad Reza Shah unsuccessfully sought to persuade Sadiqi to accept the premiership, the latter had considered selecting Adamiyat as a cabinet colleague.

Through various activities, including a period of membership of the Iranian Writers’ Association—which had resumed its activities in 1977—Adamiyat sought to support the cause of democracy, but with the consolidation of clerical rule which followed the revolution of 1979, he led a reclusive life of unease. Ongoing intimidation and harassment forced him to leave the country in October 1991 to reside initially in Paris and soon thereafter in Oxford and London, but his aversion to a life of exile led to his return to Iran in May 1993. Resumed harassment and pressure met with his unremitting resistance and ended only with intervention by a senior government official. Although suffering from ill-health during the last decade of his life, his intellectual capacities remained undiminished. A tall, elegant and poised figure, Adamiyat combined the urbane deportment of a seasoned diplomat with the fastidiousness of an empirically-minded historian. Temperamentally reserved, he shunned publicity, loquacity, and excessive sociability. He was widely admired not only for his innovative and bold contributions to the study of modernity and constitutionalism in Iran, but also for his unwavering dedication to secular social-democratic ideals and his standing as a civically engaged public intellectual. He was respected by both friends and foes as a leading historian, and a dignified man of principle.

He is survived by his wife, Shahin-Dokht Enayat-Pour, whom he married in 1971; they had no children.