Introduction

As the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic reached Europe, pictures of people hoarding toilet paper and flour started making the rounds in the media. The pandemic, it appeared, brought to light the most basic human instinct of “me first, everyone else second”. However, as the news cycle moved on, another story emerged: one of increased solidarity, wherein neighbours, whose interactions were limited to a polite “Hello” or “Goodbye” in the hallways prior to the pandemic, now took care of each other’s groceries. Similar developments occurred among countries, where on the one hand, hygiene products were subject to export embargoes, but on the other hand, doctors were posted to the hardest hit regions in other countries, and patients in such regions were relocated to hospitals with intensive care capacities abroad.Footnote 1

In this paper, we study how individuals choose to whom to extend support in times of crisis by analysing deservingness perceptions regarding three central policy areas of this pandemic: 1) with much of the economy in suspense for months as a consequence of the social distancing measures, should self-employed individuals – who by law could not access short-time work schemes – be eligible for state support? 2) Given rising hospitalization rates, who should be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in the case of shortages? And, 3) With extensive travel restrictions and border controls in place, who should still be able to enter a given country?

To analyse how people decide on these essential distributive questions, we conducted three original conjoint survey experiments (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) administered to an incentivised online sample in Switzerland between late April and early May 2020 and again between late November and early December 2020.Footnote 2 In Switzerland, similar to other countries, extensive policies in the economic, health and mobility domain were implemented by the government to counter the negative effects of the crisis.

The results show that, overall, people’s decision-making during times of crisis follows the logic of conditional solidarity. In other words, also during the pandemic people allocate scarce resources according to the logic of conditional solidarity as we know it from other policy domains (Bowles and Gintis, Reference Bowles and Gintis1998, Reference Bowles and Gintis2000; Fong et al., Reference Fong, Bowles, Gintis, Kolm and Ythier2006; Knotz et al., Reference Knotz, Gandenberger, Fossati and Bonoli2021a; Petersen, Reference Petersen2012, Reference Petersen2015; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Sznycer, Cosmides and Tooby2012; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000; van Oorschot et al., Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). Conditional solidarity means those perceived as deserving of collective help are those who 1) have shown themselves to be faithful contributors to the common good in the past; 2) make efforts to improve their own situation or give back to the community at present or in the near future; and 3) are perceived as similar in terms of national or ethnic background. In contrast, those who have not contributed in the past, those who have acted counter to the common interest, and those who are perceived as different are less likely to be considered deserving of collective support.

Our findings are important for two reasons. For one, the COVID-19 pandemic is already now seen as a “once-in-a-century” crisis. And while this was at the time also true for the Great Recession not long ago (e.g. Pontusson and Raess, Reference Pontusson and Raess2012), the current crisis is different due to the fact that it combines a public health and an economic crisis, and, one might add, a crisis for many who rely on free cross-border mobility. Research on deservingness perceptions has developed mostly with a focus on “normal times”. Yet, solidarity is a human disposition that acquires its utmost importance in times of crisis. As a result, it is important to document for the historical record what determines solidarity also in situations that are uncommon in the extent of suffering that they generate. Second, our study contributes to a more general understanding of deservingness perceptions and their variation across policy areas and target groups. We study deservingness perceptions in policy areas that have received different amounts of scholarly attention, ranging from moderate (health care in general; e.g. Jensen and Petersen, Reference Jensen and Petersen2017; van der Aa et al., Reference van der Aa, Hiligsmann, Paulus, Evers, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017) to very little (international mobility; see e.g. De Coninck and Matthijs, Reference De Coninck and Matthijs2020). Deservingness perceptions in the case of aid to the self-employed have, to our knowledge, not been studied yet.

This article continues with a literature review of the determinants of deservingness perceptions. We then formulate expectations regarding how people are likely to attribute deservingness during the COVID-19 crisis. Next, we present our data, methodology, and the three experiments. Finally, we discuss the results and conclude by situating our findings in the larger context of deservingness research and its policy implications.

Who deserves to be helped?

The COVID-19 pandemic is a unique event in recent history. Consequently, public reactions to this novel situation are equally without a blueprint. To provide a theoretical basis for our research, we first turn to studies of deservingness to welfare state programmes. Here, we can rely on a large body of literature that has identified the factors that determine perceptions of deservingness to social benefits in “normal” times, and in particular on more recent sub-strands that focus on deservingness to health care and migration. Second, we consider studies on the impact of different types of crises on people’s inclination to help others. Within this field, we rely on the literature investigating the impact of economic crises and natural disasters. Both fields of the literature are briefly reviewed in the next sections.

Conditional solidarity

Who will be helped by a community is closely linked to how deserving of help an individual is perceived to be (see e.g. Meuleman et al., Reference Meuleman, Roosma and Abts2020; Reeskens and van der Meer, Reference Reeskens and van der Meer2019; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000, Reference van Oorschot2006, Reference van Oorschot, van Oorschot, Opielka and Pfau-Effinger2008; van Oorschot et al., Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). Studying deservingness perceptions to social benefits for the unemployed, van Oorschot and colleagues identify five criteria that are relevant for the assessment of deservingness (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000, Reference van Oorschot2006; van Oorschot et al., Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017): control, attitude, reciprocity, identity, and need (CARIN). Individuals who request assistance due to bad luck and thus cannot be considered responsible for their situation (control), who are docile and thankful in their interactions with the state services (attitude), who have contributed in the past or are making efforts to do so in the present (reciprocity), who are members of the same in-group (identity) and who are under financial strain (need) are considered deserving of state help.

Research inspired by evolutionary psychology provides theoretical underpinnings for these results. From this perspective, assessments of deservingness are based on automatic and deeply rooted decision-making processes that stem from small-scale social exchanges in early human societies. Under these conditions, supporting each other and protecting the group from free riders were essential features for a group’s survival (Petersen, Reference Petersen2015; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2010). From an evolutionary psychological perspective, Petersen and colleagues (Reference Petersen2012) argue that mechanisms developed in early human societies have survived and are now visible in deservingness perceptions – for instance, regarding social benefits. A person in need activates compassion and thus increases society’s support for help if they signal the intention or (credible) effort to reciprocate in the future. Conversely, individuals activate anger and thus cause a lower inclination to help in their peers if they signal the opposite. Sharing is thus conditional on (credible) effort to reciprocate, protecting against potential cheaters who might exploit unconditional generosity within a society (Petersen, Reference Petersen2015).Footnote 3

To sum up, and building on both bodies of work, our starting assumption is that deservingness perceptions are driven by the level of the person’s need, the extent to which they are seen as having a shared social identity, their level of control over their situation, their current efforts to contribute, and their past reciprocal behaviour (see also Knotz et al., Reference Knotz, Gandenberger, Fossati and Bonoli2021a, p. 3).

Deservingness across policy areas

The underlying logic of conditional solidarity has been found to be a powerful predictor of people’s perceptions of deservingness in different policy fields also beyond unemployment benefits (see e.g. Aarøe and Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Buss, Reference Buss2019; Buss et al., Reference Buss, Ebbinghaus, Naumann, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Knotz et al., Reference Knotz, Gandenberger, Fossati and Bonoli2021a; Reeskens and van der Meer, Reference Reeskens and van der Meer2019; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot, van Oorschot, Opielka and Pfau-Effinger2008) – that is, other social benefits (see e.g. De Wilde, Reference De Wilde, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Kootstra, Reference Kootstra2016), health care (see e.g. Jensen and Petersen, Reference Jensen and Petersen2017; Van Der Aa et al., Reference van der Aa, Hiligsmann, Paulus, Evers, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017) and, recently, migration policy (De Coninck and Matthijs, Reference De Coninck and Matthijs2020). While the literature on the deservingness of the unemployed to respective benefits is rather extensive (as highlighted above), to our knowledge the deservingness to such aid specifically for the self-employed has not been studied. We therefore limit ourselves in the following to a review of deservingness in the context of health care and migration.

Research on deservingness to health care services shows that in this policy field, perceptions are very much driven by need (van Delden et al., 2004; van der Aa et al., Reference van der Aa, Hiligsmann, Paulus, Evers, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). Indeed, Jensen and Petersen (Reference Jensen and Petersen2017) argue that health care “is fundamentally special” (2017, p. 68), as deservingness heuristics automatically categorise the sick as deserving. Similarly, van der Aa and colleagues (2017), applying the CARIN criteria to health care policy in the Netherlands, find medical need to be the most important factor in the allocation of health care resources. However, control, attitude, and reciprocity also matter in this context.Footnote 4 Indeed, there are other studies on deservingness perceptions to health care that find similar patterns to those in other policy areas such as unemployment benefits. These studies find, for example, that a patient’s deservingness to medical care depends on whether their own behaviour contributed to their illness (Ubel et al., Reference Ubel, Jepson, Baron, Mohr, McMorrow and Asch2001; Wittenberg et al., Reference Wittenberg, Goldie, Fischhoff and Graham2003), but also their nationality (O’Dell et al., Reference O’Dell, McMichael, Lee, Karp, VanHorn and Karp2019), or their gender (Furnham, Reference Furnham1996). Thus, when it comes to deservingness perceptions, it is overall still an open question whether or not health care really is different.

In the context of public attitudes on migration issues, deservingness also matters (see e.g. Monforte et al., Reference Monforte, Bassel and Khan2019; for a critical discussion see Carmel and Sojka, Reference Carmel and Sojka2021). Here too, similar criteria as above inform the attribution of what is in essence the deservingness to access, settle or naturalise. Bansak and colleagues (2016) find that humanitarian concerns have a pronounced effect on European voters’ assessments of asylum seekers. Those who face prosecution, have consistent asylum testimonies, and have a special vulnerability are “substantially more likely to be accepted” (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016, p. 221). Other important factors for the assessment were economic considerations and anti-Muslim sentiment. Similarly, Hainmueller and Hangartner (Reference Hainmueller and Hangartner2013) find that in Swiss referendums on citizenship applications of foreign residents, the country of origin was the main determinant of an application’s success. Other applicant characteristics, such as better economic credentials, being born in Switzerland or having a longer residency period, increased the chances for a naturalisation success – however, much less so than origin. A recent application of the CARIN criteria to the context of migrant settlement, based on data of the European Social Survey and a cross-national survey, also underlines the relevance of, particularly, reciprocity, attitude, and identity in this policy field (De Coninck and Matthijs, Reference De Coninck and Matthijs2020).

Solidarity in times of crisis

In the above section, we describe how people attribute deservingness in different policy areas in “normal” times – namely, based on conditional solidarity. While we are not able to directly compare attitudes before and during the pandemic, we believe it is important to consider that sudden shocks can change political attitudes – and that insights learned from pre-pandemic research might not necessarily apply during the pandemic. To look for clues as to how notions of solidarity and deservingness may look in this unprecedented context, we resort to literature developed for economic crises and natural disasters to provide relevant indications.

On the one hand, economic crises have been shown to impact people’s inclination to share. Research shows that the redistribution policy preferences of the public strongly respond to changes in the economic situation of a country (Durr, Reference Durr1993). For the United States, Durr (Reference Durr1993) finds that expectations of a strong economy lead to greater support for redistributive policies, whereas expectations of economically difficult times ahead lead to a shift towards more conservative policies. In a close examination of the political consequences of two great economic crises of the past century, the Great Depression (1929) and the Great Recession (2008), Lindvall (Reference Lindvall2014) detects similar patterns regarding citizens’ voting behaviour. In both cases, the author finds a shift towards more right-wing parties in the immediate years after the beginning of the crisis, which he attributes in part to economic voting but also to a punishment of the incumbent government.

On the other hand, studies have also found that people become more supportive of redistribution and the welfare state (Blekesaune, Reference Blekesaune2007) in times of economic downturns, and that they see the unemployed as more deserving when unemployment increases (Jeene et al., Reference Jeene, van Oorschot and Uunk2014; Uunk and van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019). Likewise, research on people’s predisposition towards sharing with those in need during natural disasters suggests that people show increased pro-social behaviour towards others directly after events such as floods or earthquakes (Cassar et al., Reference Cassar, Healy and von Kessler2017; Chantarat et al., Reference Chantarat, Oum, Samphantharak and Sann2019; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Han, Ren, Bai, Zheng, Liu, Wang, Li, Zhang and Li2011). Rao et al. (Reference Rao, Han, Ren, Bai, Zheng, Liu, Wang, Li, Zhang and Li2011) in the aftermath of the 2008 earthquake in Wenchuan, China, find, for instance, that with increasing proximity to the epicentre, people displayed more pro-social behaviour.

Expectations

Given the novelty and the uniqueness of the context we study, we decided not to develop precise hypotheses but to formulate expectations based on the literature discussed in the above sections. Additionally, as we have pointed out throughout the paper, we are unable to map any change of preferences within respondents (before/after the pandemic). Rather, we are only able to map their preferences at two points of the pandemic and thus assess their attitudes during the pandemic.

Conceivably, and as suggested by the literature on solidarity during economic crises and in natural disasters, an event like the COVID-19 pandemic could affect peoples’ support for redistribution and consequently who they perceive to be deserving of support. However, it is unclear if and how exactly this would affect the attribution mechanism behind the deservingness perceptions – namely, which criteria matter and how.

We therefore adopt a more exploratory approach regarding the differences in the relative roles of deservingness criteria during the pandemic. That said, a comparatively large effect of the level of need, in line with some of the findings on deservingness in health care, may be plausible for the attribution of ICU beds. The same would be plausible for reciprocal behaviour in the context of economic aid and identity in the context of migration. The self-employed, who as a group remain outside most contribution-based welfare state agreements (although they of course pay taxes), might incite more scepticism than “regular unemployed” and thus reciprocal behaviour may become more important. In the context of migration, the importance of origin or identity is evident.

At the same time, based on the literature on deservingness in the context of different policies, we could expect broadly similar patterns across these three areas, with past and present reciprocal behaviour and the similarity of identity playing large roles. Consequently, we could expect that regardless of the crisis situation, the criteria of reciprocity, effort, control, identity and (medical) need collectively matter for deservingness perceptions across the three policy fields also during this pandemic. Despite the differences in how scarce the “good to share” (ICU beds, state-funded aid packages, or access permissions to a given country) is, respondents are faced in essence with a redistributive question and rely on the deeply rooted heuristics for assessing potential partners in sharing agreements.

Data and method

In our empirical analysis, we focus on three important policy problems that became topical during the health crisis and imply deservingness assessments: 1) providing financial help to self-employed people who could not work because of the lockdown; 2) prioritising access to ICU beds in the case of insufficient supply; and 3) determining who could access the country despite travel restrictions. To investigate people’s assessments of deservingness in these three situations, we conducted three original survey experiments in Switzerland. The analysis relies on data collected from late April to early May and between late November and mid December 2020 by means of an incentivised online panel provided by an international market research firm. To ensure that the sample is as representative of the Swiss population as possible, we introduce quotas for age (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, over 75), gender, education (low, middle, high) and region (French or German speaking). Our data comprise 1535 respondents who rated a total of 3,070 vignettes for three separate experiments in wave I and 1498 respondents who rated 2996 vignettes in wave II.Footnote 5

Switzerland is a representative case to study deservingness perceptions because the per capita COVID-19 infection rate was broadly comparable to that of other countries, but not so high that the health care system could no longer cope with the number of infected residents. Moreover, at least during the first wave of the pandemic, policy reactions were similar to those adopted in many other countries: a partial lockdown was adopted, and public life slowed conspicuously, although the measures were less drastic than those introduced in extreme cases such as Italy, Spain, or France. Finally, Switzerland is ideal to study the perception of travel restrictions in the population given its large number of migrant workers and cross-border commuters and the high salience of the migration issue, as the history of popular votes on the topic of (im)migration has shown.

We use survey experiments, as they allow testing causal relationships while minimising social desirability bias (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015), since assessing the deservingness of individuals to government help, to an admission to the ICU and to entering Switzerland is likely to be subject to social desirability. This assessment can be achieved by randomly varying specific traits in schematic descriptions that respondents are asked to evaluate, which in turn makes it harder for survey participants to identify the manipulated dimensions, thereby minimising social desirability bias. Especially when studying sensitive topics, this is a very important precondition to gather valid measurements. Furthermore, this approach allows us to study multiple theoretical mechanisms simultaneously while gathering respondent-level information to test for subgroup heterogeneity. Of course, this way we are only able to capture an intent and not actual behaviour. However, studies that do compare stated and real behaviour show a high degree of correspondence between the two (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015).

For each experiment, respondents were presented two fictitious individuals and were asked to indicate on a scale from 0 to 10 (“lowest priority” to “highest priority”) the priority with which these individuals should 1) receive financial aid if self-employed and unable to work because of the pandemic; 2) have priority access to an ICU bed; and 3) be granted entry into Switzerland.Footnote 6 Based on the respondents’ rating we created a continuous dependent variable on deservingness, with higher values indicating higher deservingness of the vignette person. The levels of each attribute in an experiment and the order in which the experiments were presented to the respondents were randomised. The experimental section was followed by several questions relating to the respondent’s personal situation and political opinions.

We presented the descriptions in bullet points, including several attributes at once, to reduce the cognitive effort for respondents. While order effects of the attributes cannot be excluded, as we did not randomise the order of attributes, flow vignette texts are a common choice in factorial survey experiments (Auspurg and Hinz, Reference Auspurg and Hinz2015), and ratings do not differ depending on whether vignettes are presented as running texts or tables (Sauer et al., Reference Sauer, Auspurg and Hinz2020). Finally, we exclude implausible combinations of attributes in each experiment to ensure that the scenarios appear as realistic as possible. Indeed, as the robustness checks show, the scenarios are assessed to be (very) realistic by respondents overall.Footnote 7

We estimate the average marginal component effects (AMCE), as presented in Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), for each experiment separately. The AMCE represents the marginal effect of an attribute (dimension) averaged over the joint distribution of the remaining attributes (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014, p. 10). This approach allows for the estimation of causal effects of each attribute in the experiments. We conducted the analyses using the cjoint R package created by Barari and collaborators (2018) specifically for the estimation of such effects.

We run a number of tests to ensure the assumptions necessary to run the AMCE are met (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).Footnote 8 For wave I, the tests for experiments I and II indicate that there are indeed carry-over effects between the first and second evaluation of vignettes present in our data. We therefore follow the recommendation by Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) and use only the data of the first evaluation task for those experiments. For wave II, we find no carry-over effects and therefore use both evaluation tasks of all three experiments. Finally, we drop observations where respondents performed the experiments either implausibly quickly (<5 seconds) or very slowly (>180 seconds). This leaves us with the following number of evaluations for wave I and II, respectively: 1461 and 2016 evaluations for experiment I; 1457 and 2014 evaluations for experiment II; and 2978 and 2032 for experiment III.

Experiments

In all experiments, we seek to describe a realistic individual and hold the basic demographic information constant: gender (male, female), age (25, 40, 55, or 70 years old), and nationality (Swiss, German/French, Turkish or Nigerian).Footnote 9 For the first experiment on state help for the self-employed, we present respondents with fictitious profiles of self-employed individuals and ask them to indicate the respective priority with which each described person should receive economic support by the state. The profiles vary on ten dimensions with the intention to capture past and current behaviour. In addition to the basic information, the vignette includes information on: the employment situation of the person’s partner (employed, self-employed or unemployed) and their financial responsibilities towards others (no responsibilities, two children, sister in Switzerland or sister abroad); the activity they exercise (hairdresser, Uber driver, undeclared household help or dentist) and how long they have been exercising this activity (just started, 5 or 10 years); whether they sought to find other sources of revenue (yes or no); and, finally, whether they had been engaging in any volunteering activities (none, cleaning in hospital or buying groceries for elderly neighbours). Footnote 10 Figure 1 below provides an examplary illustration of the vignettes in this experiment.

Figure 1. Example of the online implementation of vignettes from experiment 1 on government support for the self-employed, German language version.

In the second experiment, we present profiles of fictitious patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and seeking admission to the ICU of the local hospital (also discussed in Knotz et al., Reference Knotz, Gandenberger, Fossati and Bonoli2021b). Notably, as we also underlined for our respondents, we are concerned with access to the unit overall and not to ventilators specifically. Respondents are asked to indicate the respective priority by which they would attribute ICU access to each described patient. Aside from the basic dimensions, the patient’s characteristics vary on five dimensions: the severity of the disease (light, moderate, severe breathing difficulties) and the prognosed chances of recovery (good, unclear, no chance); their behaviour prior to the diagnosis (complying or not with social distancing guidelines, volunteering as in experiment I); and their behaviour since their diagnosis (complying exactly or only partially with doctor’s recommendations).Footnote 11 These characteristics provide information about past behaviour, but also about medically relevant criteria that would inform a medical professional’s decision making.

For the final experiment, we choose a simplified setup of a person seeking to enter Switzerland as it may occur in everyday life. The basic dimensions are the same as previously. Additionally, we vary legal status over four levels (Swiss citizenship (dual for those with other nationalities), permanent residency permit, a simple work and stay permit or visa) and the reason for seeking to cross the border over six levels: three of these are work-related (work in health sector, as farm help, or in a supermarket) and three are more personal (visit a doctor, family, or friends). Respondents are asked to indicate the respective priority to cross the border they attribute to each fictional vignette person.Footnote 12

Results

While the results initially appear to paint a diverse picture of solidarity, a common story emerges in all three experiments and across both waves: respondents are willing to share on the basis of the past and current behaviour of the person in need and their characteristics. In other words, people follow the logic of conditional solidarity also during the pandemic.

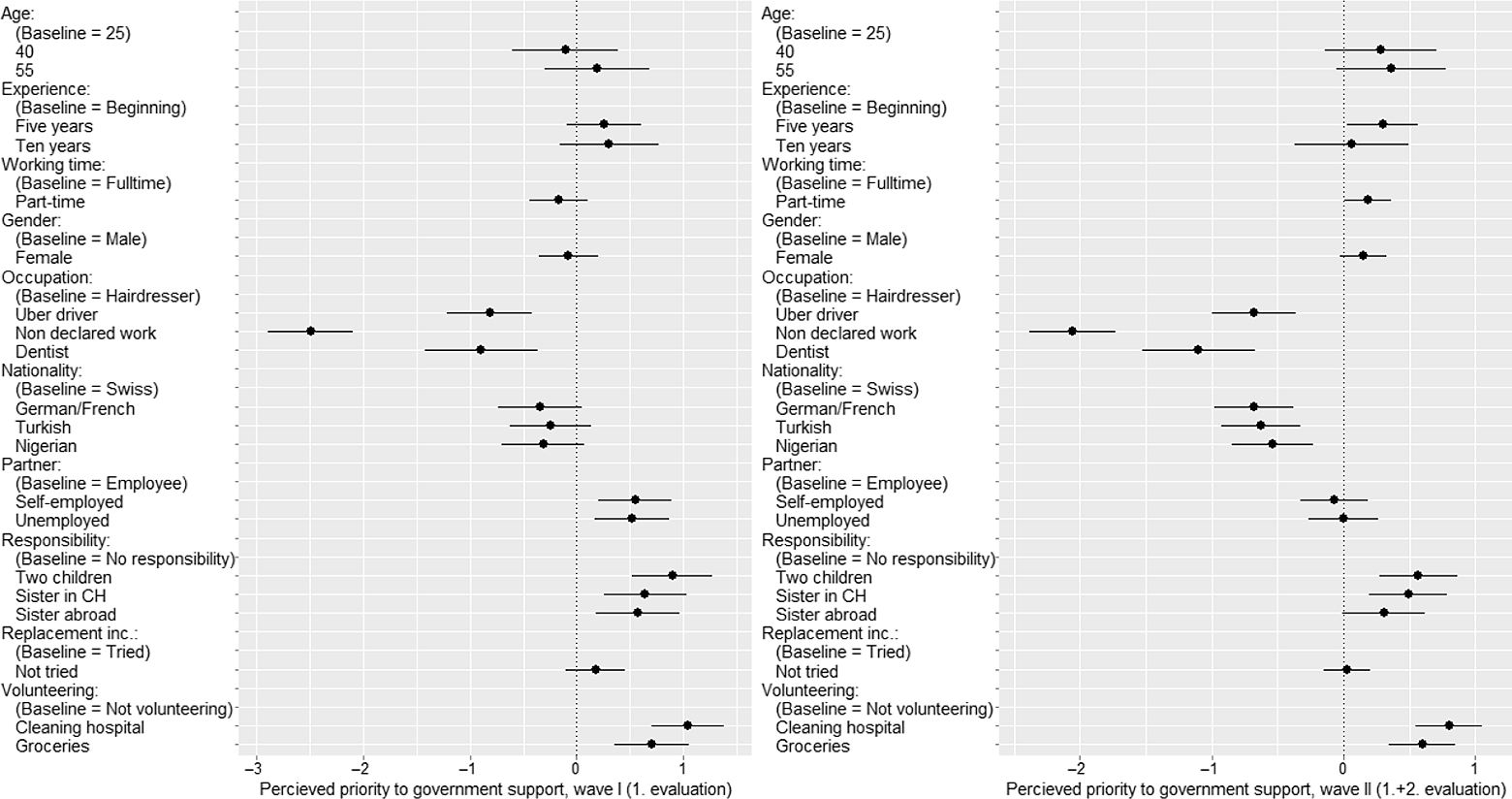

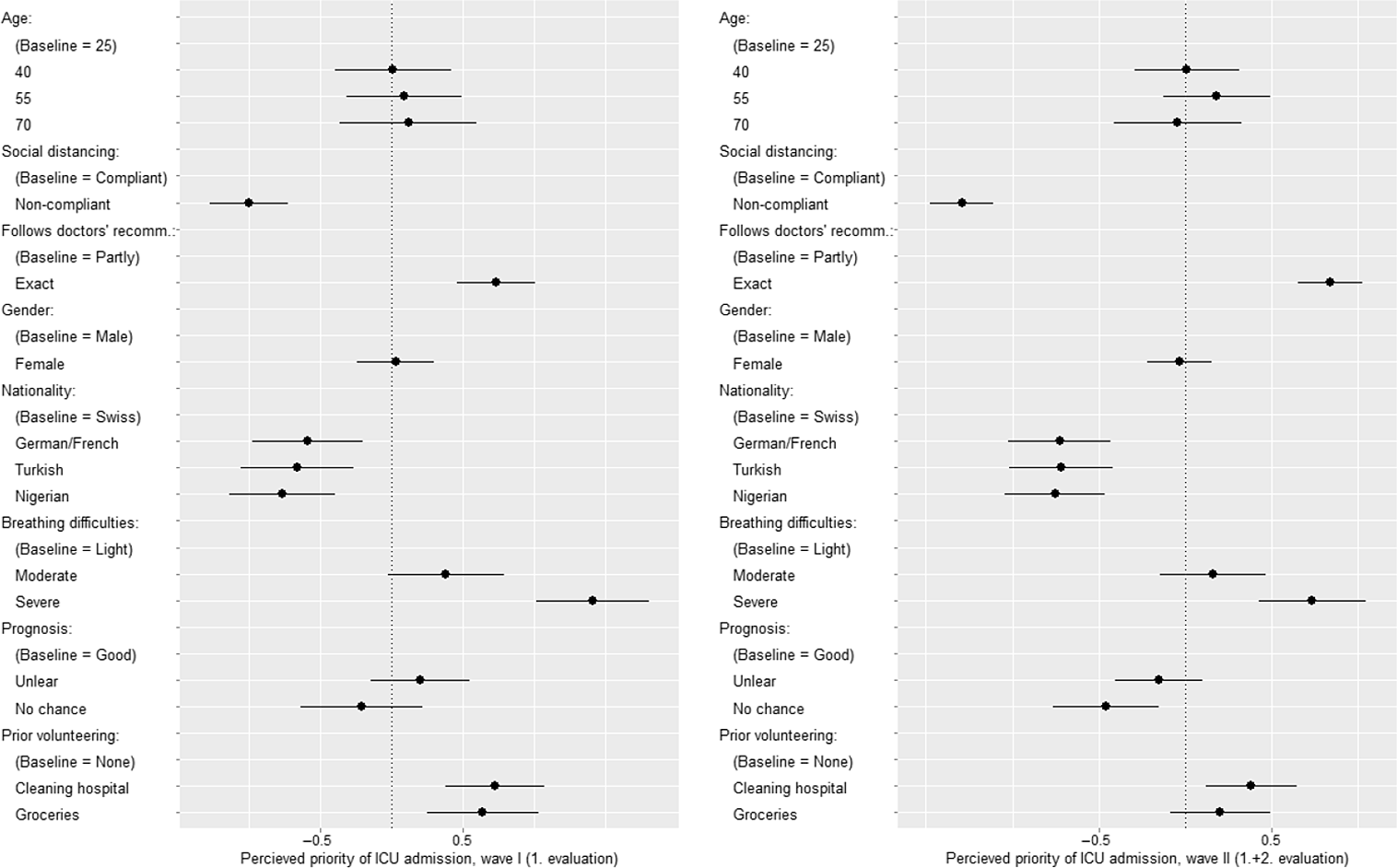

In all experiments, reciprocity in the form of contributing to the community, be it through past actions and contributions or current efforts, plays a crucial role in determining an individual’s deservingness. For the self-employed, the results for both wave I and II are summarised in Figure 2, there is a clear distinction between declared and undeclared workers concerning their perceived deservingness of state help. Individuals who remain outside of sharing arrangements (by failing to declare their incomes) are attributed a very low priority for receiving financial help. This negative effect of non-compliance is the strongest in the experiment, even though household help or gardening are typically low-skilled, low-paid jobs and probably characterised by a high incidence of undeclared work. Similarly, individuals not following the social distancing recommendations in the ICU experiment (results summarised in Figure 3), are severely punished by being attributed the lowest deservingness, while those complying conscientiously with their doctor’s recommendations are perceived as more deserving than those who do not comply. Finally, efforts to contribute to society through volunteering are rewarded in both experiments.

Figure 2. Average Marginal Component Effects of self-employed attributes on perceived priority for government support. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Wave I: N = 1464, first evaluation task only; wave II: N = 2016, both evaluation tasks.

Figure 3. Average Marginal Component Effects of patient attributes on perceived priority of ICU admission. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Wave I: N = 1457, first evaluation task only; wave II: N = 2014, both evaluation tasks.

This distinction between those who will contribute or are committed to Switzerland and the well-being of its citizens and those who will or are not (or at least are perceived that way) is also apparent in the experiment on access to Switzerland during the lockdown (results summarised in Figure 4). Those wishing to cross the border to work in Switzerland are clearly more deserving than those who wish to see family or friends. Among workers, those in the health sector are most deserving. Here, however, it is possible that expectations around reciprocity are mixed with collective selfishness, as health care workers are in high demand during a pandemic. However, in the same experiment, no difference is made between Swiss (dual) citizens and those with a residence permit (and work/stay permit in wave II), indicating that long-term ties to the community favour the deservingness of help of the individual. Moreover, those with less stable permits (visas) are considered less deserving than citizens.

Figure 4. Average Marginal Component Effects of individual attributes on perceived priority for access to Switzerland. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Wave I: N = 2978, both evaluation tasks; wave II: N = 2032, both evaluation tasks.

Another rather stable and consistent effect across all three experiments is that of identity, which we operationalised with nationality, age, and gender, as well as legal status in the third experiment. In all three experiments we find no significant effect of gender and no significant effect of age – the latter is somewhat encouragingly surprising in the context of the ICU experiment, as age was such a prevalent point of public debate surrounding possible shortages.Footnote 13 Nationality is significantly linked to solidarity in all experiments: there is a distinction in deservingness between Swiss and non-Swiss individuals, supporting the theories on in- and out-group formation. Even if the effect is not significant in wave I for the self-employed experiment and in the third experiment, the distinction is made between Swiss and German/French individuals on the one hand and Turkish and Nigerian individuals on the other.

Finally, the effect of need on deservingness varies across the three experiments. In the experiment concerning state help for the self-employed, the negative effect of non-compliance is actually stronger than the positive effect of need. Nevertheless, a higher priority for such help is attributed to individuals with financial responsibilities for more than just themselves – namely, partners who are self-employed or unemployed (in wave I only), children, or other family members. For the ICU experiment, individuals with severe breathing difficulties are most deserving of a bed in the unit. This is unsurprising since, as discussed in the theory section, research on deservingness to health care services highlights the overwhelming importance of need in this context. However, this is only true for individuals with severe breathing difficulties, not those with moderate breathing difficulties. In the third experiment, we find that those wishing to see a doctor are less deserving than those who seek entry to work. Thus, it appears, at least in the case of who should be allowed to enter Switzerland, that economic considerations outweigh the need of the individual wishing to cross the border, a fact that others have also noted in the evaluation of asylum seekers (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016).

Taken together, these results show that assessments concerning an individual’s deservingness indeed follow a logic of conditional solidarity (Bowles & Gintis, Reference Bowles and Gintis1998, Reference Bowles and Gintis2000; Fong et al., Reference Fong, Bowles, Gintis, Kolm and Ythier2006; Petersen, Reference Petersen2015; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000). Giving back to the community, through both past contributions and forward-looking actions, is important across scenarios, as is the respect for norms and responsible behaviour and the person’s identity. Thus, the criteria of reciprocity, effort, identity, and need are relevant for deservingness assessments, irrespective of the context. Our experiments were not suitable to investigate the relevance of another important determinant of deservingness perception: control. The situations we asked respondents to assess were the result of the pandemic, and the vignette-persons had very little control over the situation of need they found themselves in. The only exemption is non-compliance with social distancing rules in the ICU experiment, where we see that control matters significantly.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a unique opportunity to analyse deservingness assessments in a crisis context: specifically, the provision of government aid to the self-employed; the rationing of ICU care; and the restriction of cross-border movement. Based on three survey experiments at two points during the pandemic, we demonstrate that in times of crisis, solidarity with the needy follows the logic of conditional solidarity, with the well-known deservingness criteria playing a very important role: reciprocity, effort, identity, (medical) need and control (Bowles and Gintis, Reference Bowles and Gintis2000; Petersen, Reference Petersen2015; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Sznycer, Cosmides and Tooby2012; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000, Reference van Oorschot2006; van Oorschot et al., Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017).

However, as the differentiated impact of the different criteria across policy fields indicates, the importance of a given criterion may depend on the specific context or situation in which the deservingness of a given individual is assessed. In the context of relief for Hurricane Katrina victims, for example, Fong and Luttmer (Reference Fong and Luttmer2009) find strong evidence of subjective ethnic or racial group loyalty, which proves to be a powerful predictor for giving to members of that same group. This predictor of racial bias is even stronger than the objective race of the respondent (Fong and Luttmer, Reference Fong and Luttmer2009, p. 85). It could very well be that in a context such as the United States, where race and racially based discrimination are such salient issues, questions of identity may outweigh or dominate other deservingness criteria, such as control, even in the aftermath of a natural disaster (Henkel et al., Reference Henkel, Dovidio and Gaertner2006; Reid, Reference Reid2013).

With this study, we contribute to the literature on deservingness perceptions by showing that, first, even in times of a global pandemic, traditional models of conditional solidarity apply. These results are stable across the first two waves of the pandemic (i.e. April and October 2020). Additionally, we innovate by demonstrating that beyond traditional applications of deservingness theory, the criteria of conditional solidarity apply to other policy areas, including economic support for the self-employed and cross-border mobility. Third, our study shows that identity also matters in relation to deservingness to health care, confirming recent findings within the literature on deservingness perceptions (Larsen and Schaeffer, Reference Larsen and Schaeffer2021).

We also contribute to a growing literature on deservingness in times of crisis (Larsen and Schaeffer, Reference Larsen and Schaeffer2021; Reeskens et al., Reference Reeskens, Roosma and Wanders2021). True, ideally, in order to assess the impact of the pandemic on deservingness perceptions, we would have fielded a first wave of the experiment prior to the pandemic. However, we still believe that it is worthwhile to map which attitudes people display in such an unprecedented time. Clearly, future research would also need to validate whether our findings indeed translate to other (crisis) settings. Here, it would be of interest to understand which circumstances trigger the relative importance of each of the criteria in a given crisis situation or policy field.

Our research has policy implications as well. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that solidarity is crucial in times of crisis. Despite certain groups being at a greater risk of experiencing more severe (and in some cases deadly) courses of the disease, everyone is more or less equally susceptible to contracting or spreading it. Many of the measures to curb the spread of the virus, such as physical distancing and wearing a mask, rely on everyone accepting small limitations on the part of the individual for the common good. While the great majority of people do follow these official guidelines, at the time of writing they have been called into question by some parts of the population.Footnote 14 To successfully maintain the support of the various health safety measures and the support packages for those suffering economically as a consequence of the de facto halt of public life in the first half of 2020, understanding the mechanisms that underlie people’s solidarity with those in need is crucial for political authorities to successfully appeal to said solidarity.Footnote 15 It is also important to accessibly communicate to the public the reasoning behind a given decision making, e.g. of the ethical rationale behind triage guidelines to the public (Knotz et al., Reference Knotz, Gandenberger, Fossati and Bonoli2021b).

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the University of Lausanne LAGAPE seminar, a NCCR on the move Research Day, the Public Policy Studies Association Japan (PPSAJ) 2021 Online Conference, the 27th International Conference of Europeanists, 18th IMISCOE Annual Conference, 2021 – SASE Conference, and the ECPR General Conference. We thank Ayako Nakamura, Anita Manatschal, Rinus Penninx, Philipp Trein and Philippe Wanner and the participants of the different panels for their helpful comments. We gratefully acknowledge having received support for this research from the National Centre of Competence in Research on Migration and Mobility (‘NCCR – on the move’), which is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF; Grant No. 51NF40-182897).

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279421001070