Since the 2005 election catapulted the Movement Toward Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo, or MAS) party to the presidency, Bolivian politics has changed in dramatic ways. The MAS established a political hegemony that stood in sharp contrast to the system dominated by three parties that rotated in office and promiscuously shared power, in what became known as pacted democracy and parliamentarized presidentialism.

There is a significant academic literature about the MAS: its origins and ascent to power, its internal party dynamics and links with social movements, its public policies and performance in office, its political ideology (Molina Reference Molina2007), the reasons for its electoral success (Madrid Reference Madrid2012), and its political culture and conception of power (Oporto Reference Oporto2009; Lazarte Reference Lazarte2010). However, there is a dearth of scholarly work that systematically evaluates Bolivia under the MAS as a regime type. Accurate classification is essential because it impinges on many other areas of research on Latin America, not least the assessment of the state of democracy in the region and the relationship between regime type and manifold outcomes that scholars wish to explain.

The widely acknowledged salutary developments associated with the MAS’s 14-year tenure (Anria Reference Anria2016, Reference Anria2018) transpired in tandem with a concentration and abuse of power, as well as the closing of political spaces for the opposition in various arenas of competition. While the MAS’s accession to the presidency in 2005 occurred via democratically sanctioned channels, its exercise of power was not democratic. The incumbent party steadily skewed all the relevant arenas of political competition, such that access to elected office became, in fairly short order, biased in its favor. Bolivia under the MAS has been labeled and examined as a postliberal democracy (Wolff Reference Wolff2013), a radical democracy (Postero Reference Postero2010), an intercultural democracy (Mayorga Reference Mayorga2011), an indigenous-liberationist democracy (Webber Reference Webber2011), a delegative democracy (Cameron Reference Cameron2018), a delegative democracy with elements of incorporation (Anria Reference Anria2016), a semidemocracy (Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Aníbal2015, 116), and other forms of “democracy with adjectives.”

Because most Latinamericanists continue to label Bolivia under the MAS a democracy—with adjectives or not—it is important to assess what a procedure-based evaluation of the regime yields for classificatory purposes. A minority of scholars have categorized the regime as belonging to the family of authoritarian regimes; one such is Bolivian scholar René Mayorga, who calls it a plebiscitarían dictatorship (R. Mayorga Reference Mayorga2017). Barrios (Reference Barrios2017) considers the regime to be nondemocratic after 2013. De la Torre (Reference De la Torre2017), as well as Levitsky and Loxton (Reference Levitsky, James and de la Torre2019), labels Bolivia under the MAS a competitive authoritarian regime, but these authors, pursuing other lines of inquiry, have not undertaken a systematic appraisal to justify their categorization. This article aims to provide a more systematic evaluation, putting special emphasis on features of Bolivia’s electoral playing field that previous scholarly work on Bolivia has bypassed—essential conditions for judging the freedom and fairness of elections.

The article is organized as follows. It first makes explicit the concept of competitive authoritarianism as one with a family resemblance structure. The bulk of the article documents and analyzes the purposeful MAS-directed slanting of four key arenas of political contestation—electoral, legislative, judicial, and mass media— that created substantively uneven playing fields. In a quest to fill a gap in the extant scholarly literature, somewhat more space is devoted to scrutinizing the slope of the electoral arena. Subsequently, the article leverages V-Democracy measures for the purpose of regime classification, comparing Bolivia’s V-DEM score declines across nine indicators to those of four Latin American electoral authoritarian regimes.

Competitive Authoritarianism as a Family Resemblance Concept

Competitive authoritarian regimes have been defined as those in which violations of open, free, and fair elections, as well as violations of civil liberties and political rights, are “broad and systematic enough to seriously impede democratic challenges to incumbent governments,” such that they create “an uneven playing field between the government and the opposition” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 53). Elections remain meaningful and are the key instrument via which political power is allocated, but unequal access to financial resources, mass media, the law, and the state apparatus writ large confer on the ruling party an unfair advantage at election time.

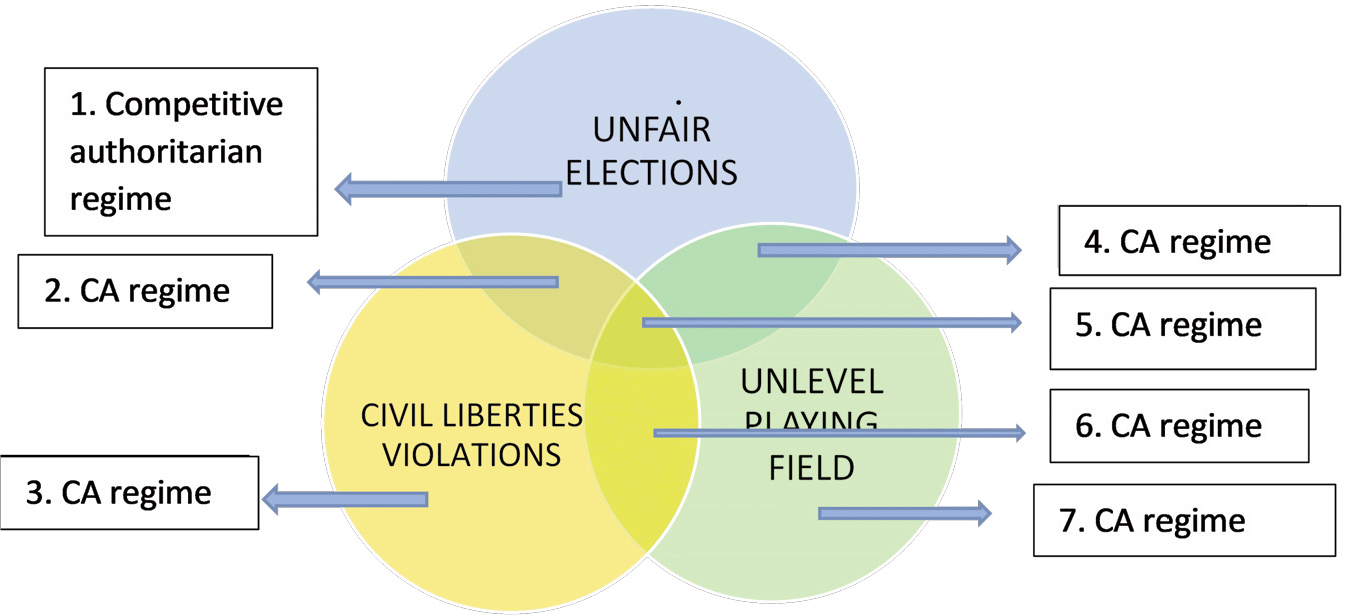

The competitive authoritarian concept, as operationalized by Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 365–68), has a family resemblance structure because any regime exhibiting at least one of the following traits belongs to the category: it holds unfair elections; it violates civil liberties; or it presents an uneven playing field in access to the state, the media, or resources. More specifically, the concept has an individually sufficient family resemblance structure (Barrenechea and Castillo Reference Barrenechea and Isabel2019, 119–22), because any of the three attributes is sufficient for membership and all attributes are substitutable. Figure 1 shows that the competitive authoritarian regime type encompasses seven different possible permutations of traits.

Figure 1. The Individual Sufficiency Structure of the Competitive Authoritarian Concept

Some scholars have reasoned that to apply this regime label to Bolivia is to perpetrate conceptual stretching (Wolff Reference Wolff2013; Anria Reference Anria2016; Cameron Reference Cameron2018), because the country displays a low degree of liberalism (rule of law, checks and balances) but presumably free and fair elections. To cope with the potential problem of overstretching, the standard solution to extend a concept without a serious loss of meaning is by means of either “family resemblance” or radical categories (Collier and Mahon Reference Collier and Mahon1993). Because the competitive authoritarian concept has a built-in family structure, however, scholars who argue that the application of the concept suffers from overstretching may be eliding its individually sufficient structure, thereby overestimating the actual threshold of membership into this regime type. For instance, a regime may display reasonably free and fair elections and yet qualify as competitive authoritarian, due to government-sponsored violations of civil rights or highly unequal access to the state, the law, and resources.

Certainly, a defensible critique of the concept’s structure centers on its alleged low intension (i.e., the number of necessary attributes). The concept’s operationalization has been argued to be too lax, such that an excessive number of regimes are thereby classified as nondemocratic (see Cameron Reference Cameron2018). However, inevitable tradeoffs follow from the purposeful increase of competitive authoritarianism’s intension (via a change in concept structure); chiefly, the conceptual dilution of democracy qua regime type. From the viewpoint of descriptive inference, the individually sufficient family structure does endow the concept of competitive authoritarianism with a lower degree of internal differentiation (how much we can learn about a case by the fact that it is an instance of the concept), but it provides for greater differentiation of the negative pole of the concept; namely, democracy as a regime type.

Therefore, the conceptual structure of competitive authoritarianism forces researchers to uphold a demanding procedural definition of democracy, such that all its key hallmarks are included. Therein lies another key virtue of the competitive authoritarian concept’s demarcation: it underscores how democracy constitutes a complex system of interlocking and interdependent sub-regimes, such that large democratic transgressions in one (say, a slanted playing field in the judiciary or mass media) inexorably have important implications for the health and operating dynamics of others (say, free and fair elections). This interdependence of sub-regimes makes the concept’s individually sufficient family resemblance structure quite suitable.

Slanting Key Arenas of Political Competittion: Electoral Arena

The MAS severely undermined the integrity of the electoral playing field in a panoply of ways, all of which created unfair competition. Four of them are highlighted in this section: uneven access to campaign resources, the partisan capture of the national electoral management body, artificial truncation of the electoral supply, and repeated violations of the democratic principle of the irreversibility of elections.

Access to Resources

A skewed playing field in the realm of campaign resources can seriously hamper the opposition’s ability to compete. Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 10–11) identify several methods by which incumbents can use and abuse the state to create large resource disparities compared to the opposition. The MAS made recourse to the most prominent methods.

First, the ruling party made direct partisan use of state resources, dramatically increasing public resources spent on publicity. Data from the national budget show that the Ministry of Communication and public broadcast channel 7, both nonstop sources of government propaganda, spent 2,197 million bolivianos (about US$300 million) from 2006 to 2016 (Ayo Reference Ayo2018, 28). Other government mass media outlets and state-owned entities with their own propaganda budgets, such as Entel, ABC, Satelite Tupac Katari, and YPFB, added to the sum total. The estimated MAS propaganda budget was unprecedented in size, hovering between US$100 and $150 million per year (Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014).

Fueled with ample monetary resources, the MAS ushered in the politics of permanent campaigning in Bolivia. Opposition parties were in no position to come close to matching those quantities and lacked the resources or instruments to engage in permanent campaigning. For reference, the spokesman for the main opposition party in the 2019 elections unwittingly created a scandal when he revealed Comunidad Ciudadana’s campaign budget to be US$10 million (Página Siete 2019), a high amount by Bolivian historical standards—but barely a fraction of the MAS’s war chest.

Second, the MAS used the state to monopolize access to private sector finance. The MAS padded its party coffers via the discretionary use of government licenses and by state contracts to corner access to private sector finance. During its tenure, noncompetitive bidding for state contracts benefited international companies (over national ones) in quid pro quo arrangements pervaded with corruption, highly inflated prices, and other irregular practices. These arrangements provided ample finance for the governing party. The most public cases were those involving the Chinese firm CAMCE, the consortium Hidroeléctrico Misicuni (Ayo Reference Ayo2018, 41–51), and the Brazilian construction giant OAS, among many others. The patrimonialization of public resources increased drastically under the MAS government. Whereas in 2004, 76 percent of public investment was adjudicated via public tender, by 2010 the figure had declined to 41.6 percent, and by 2014 it had been reduced to a negligible 1.3 percent (El Día 2016).

The MAS also moved to deprive the opposition of public resources. The MAS-led legislature eliminated public financing for parties via the 2009 Transitory Electoral Law, dealing a blow to the party-building efforts of the opposition (Romero Ballivián 2011). The measure contributed to “the weakening of party structures” and left the “opposition [with] limited sources of finance [for the 2009 campaign]” (Romero Ballivián 2011, 218). The same scenario obtained in electoral campaigns throughout the 2010s, for this pro-incumbent legislation remained enshrined in the electoral law. The absence of public finance became particularly damaging to opposition parties because of the MAS’s effective courting of economic groups of the eastern Media Luna provinces, creating a schism between the political and the economic elites in the main bastion of government opposition (Eaton Reference Eaton, Levitsky, Loxton, Van Dyck and Jorge2016, 394–97).

In sum, the resource asymmetry between the MAS and its opponents was of several orders of magnitude, seriously skewing the electoral playing field.

Capture of the Electoral Management Body

Early in Morales’s first administration, the executive branch put incessant pressure on some members of the Corte Nacional Electoral (National Electoral Court, CNE) to resign. Several MAS representatives, including President Morales, unleashed a battery of accusations to discredit the Electoral Court leadership in order to shape public opinion and pave the way for wholesale changes in its top personnel. The accusations included charges that the CNE had fraudulently purged MAS voters from the official voter rolls. One avenue by which the government effectively purged the electoral management body was a drastic salary reduction for its appointees. This maneuver led to the resignation of CNE president Óscar Hassenteufel, who privately voiced his concerns about a coordinated governmental effort to get control of the institution (Wikileaks 2006).

The MAS’s appointments to the electoral agency reversed the post-1991 trend whereby only individuals of “proven professional trajectory, moral solvency and partisan independence” were named (Romero Ballivián Reference Romero Ballivián2009, 87). The electoral management body consists of seven members, six named by Parliament and the head named by the nation’s executive branch. Its seat supermajorities in Parliament readily enabled the ruling party to co-opt the arbiter of the electoral game. The naming of José Luis Exeni to head the (newly labeled) Tribunal Supremo Electoral (TSE) was interpreted in many circles as “a threat to the independence of the electoral agency” (Romero Ballivian Reference Romero Ballivián2009, 91).Footnote 1 Exeni resigned amid widespread opposition pressure, concerned about his nontransparent management of the national electoral roster (La Nación 2009).

The second head of the agency the MAS appointed was Wilfredo Ovando, a member of the Bloque Simón Bolívar, which is a Cochabamba organization of lawyers loyal to the MAS. Ovando’s TSE presided over several decisions that evinced partiality toward the ruling party. One example was the suspension of the Unión Democrática opposition party during the 2015 regional elections in the department of Beni, “on grounds that it disseminated an unauthorized poll” (El País 2015). The suspension resulted in the disqualification of its 228 candidates from the ballot, including Ernesto Suárez, the main opponent of the MAS candidate for governor. MAS candidates accused of similar deeds were not punished by the TSE (Alberti Reference Alberti2016, 35). The embarrassing public uncovering of Supreme Electoral Tribunal magistrates’ intimate links to the MAS forced the resignation of six out of its seven members in the wake of the 2015 regional elections (Freedom House 2016). The respected former CNE magistrate and scholar Jorge Lazarte urged a comprehensive Organization of American States audit of the TSE in its technical, operative, administrative, and judicial dimensions, a sign of the institution’s growing disrepute (see Lazarte Reference Lazarte2016).

The consequences stemming from the MAS’s capture of the TSE were numerous, contributing to the tilting of the electoral playing field. The electoral agency allowed President Morales free rein to engage in political proselytizing with the use of public resources and permitted MAS regional and local candidates to accompany Morales in the inauguration of many public works (Los Tiempos 2015), in violation of the extant electoral code. In the March 2015 elections, both President Morales and Vice President García Linera engaged in electoral coercion—an infraction that is severely punished in the Electoral Code—when they separately issued a public threat to voters. Constituencies where local MAS candidates lost would not receive any central government funding from the Evo Cumple public works program and would be denied other public investments (Correo del Sur 2015; Ayo Reference Ayo2018).Footnote 2

The TSE remained silent when it faced this unambiguous violation of the Electoral Code. This permissive attitude on the part of the TSE stood in sharp contrast to the drastic measures the electoral institution took against opposition politicians who were accused of infringing small norms in the code, including the disqualification of some. The TSE thus evinced clear manifestations of the discriminatory legalism for which hybrid regimes are known.

A new nadir in the public’s faith in the TSE’s institutional independence occurred when the organ officially gave the green light to the constitutionally illegal candidacy of the Morales-Linera electoral ticket in late 2018. That controversy forced the resignation of the sitting president of the TSE, Kathia Uriona. But the organ’s disrepute only deepened under the presidency of María Eugenia Choque, widely considered partial to the MAS. Under her command, the electoral body became ever more politicized, via the indiscriminate firing of technical personnel. Against this backdrop, a poll taken before the October 2019 presidential elections showed that 60 percent of Bolivians believed that the elections would be fraudulent (El País 2019). The ensuing electoral process validated those fears.

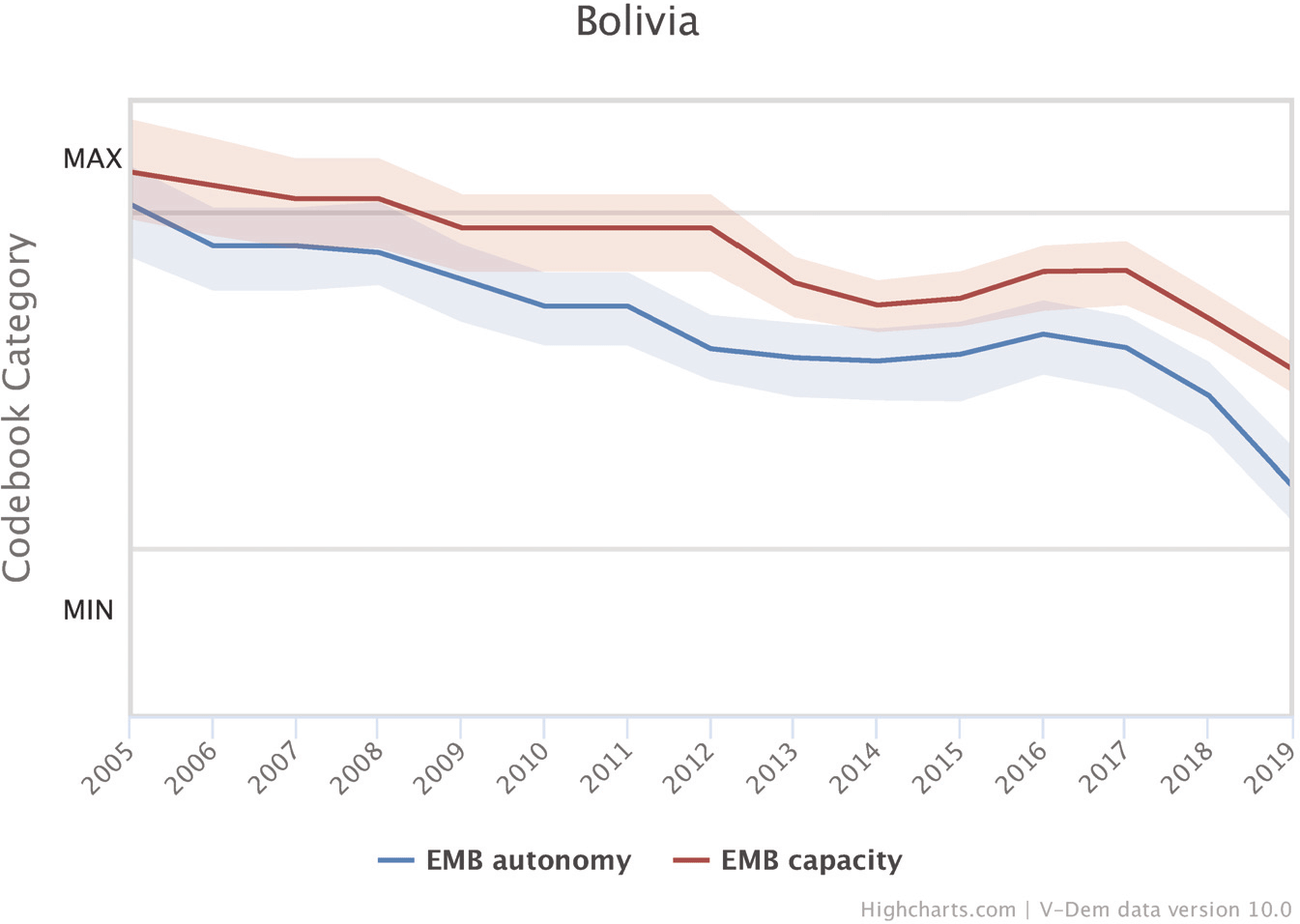

The team of 30 experts sent by the Organization of American States certified that the electoral process was marred by “obvious irregularities” and urged the government to renovate the electoral management body in its entirety. The OAS audit found falsified signatures and manifold alterations of data in 23 percent of the ballots examined, electoral information directed to two hidden external servers, prefilled and modified tally sheets, serious deficiencies in the chain of custody, and a “highly improbable” change in the voting tendency reported for the last 5 percent of the data computed, among many other irregularities (OEA 2019). The OAS report concluded that it “could not validate the results” and thus recommended “the undertaking of another electoral process,” in alignment with diplomatic language for declaring electoral fraud (2019, 13). What made possible both abundant discriminatory legalism and the concoction of the 2019 fraud was the MAS’s capture and deprofessionalization of the arbiter of the electoral game. A massive 72 percent V-DEM score decline in the institutional autonomy of the Bolivian electoral management body was accompanied by a sizable decline of 40 percent in its institutional capacity from 2005 to 2018 (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Electoral Management Body Autonomy and Capacity, 2005–2018 (V-DEM scores)

Limits on Electoral Supply

Governments can compromise the freedom of electoral processes by engineering a truncated supply of candidates (Reference SchedlerSchedler 2002). Deploying diverse tactics, the MAS truncated the electoral supply offered to voters in national, departmental, and local contests. The Morales government used the electoral management body, subservient judges, and servile district attorneys in a quest to keep many of its most relevant political opponents out of electoral contests. The MAS’s persecution of opposition political heavyweights touched all living former presidents of the republic except one, along with presidential candidates, governors, and important city mayors. Only two months after the MAS had taken the reins of the national government, former presidents Jorge Quiroga (2001–2), Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada (2002–3), Carlos Mesa (2003–5), Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé (2005–6), and former vice president Victor Hugo Cárdenas (1993–97) found themselves at the receiving end of retroactive legislation approved by the MAS-controlled Plurinational Legislative Assembly.

The pieces of legislation drafted and then used to persecute these former heads of state were the Ley de Responsabilidades (Law of Accountability) and the Ley de Lucha contra la Corrupción (Anticorruption Law). The second law introduced new (and amplified the range of existing) transgressions into Bolivia’s legal code, including the untoward use of public goods and services and illicit enrichment, while offenses that “harm the patrimony of the state and cause grave economic loss” were never to lapse legally. The MAS justified these new laws as part of an initiative to usher in a “moral revolution” to combat present, past, and future corruption in Bolivia (Malamud Reference Malamud2010).

In March 2011, the MAS brought ex-presidents Quiroga and Mesa before a congressional commission to respond to accusations that 107 petroleum contracts signed between 2001 and 2005 had “caused great economic harm to the state.” Many legal proceedings were preceded by warnings and threats emanating from the executive branch. For example, with weeks to go before the 2009 general election, President Morales publicly declared that he would send his main electoral rival, Cochabamba governor Manfred Reyes Villa, to jail; shortly after the election, Governor Reyes went into exile in the United States.

Limits to electoral supply have not been confined to the early years of MAS’s tenure in office. In 2015 the Supreme Electoral Tribunal announced that it was disqualifying 43 percent of the 15,819 candidates competing in the March regional and local elections for failing to meet registration requirements. The TSE decision affected mainly the opposition to the ruling party, particularly dissident groups that had broken with the MAS. The highest-profile MAS dissidents affected included Rebeca Delgado, candidate for mayor of Cochabamba; Ever Moya, who aspired to become mayor of Oruro; Eduardo Maldonado, a candidate for the mayoralty of Potosí; and Edwin Tupa, who ran for the mayoralty of Montero in Santa Cruz. Unidad Nacional candidates for the La Paz governorship (Elizabeth Reyes) and mayoralty were also disqualified (Latin American Newsletter 2015).

The process by which the regime criminalized political pluralism followed a fairly consistent pattern: public accusations by President Morales or his close collaborators in government; the unleashing of a concerted propaganda campaign, via mass media outlets controlled by the MAS, to discredit and taint the image of the accused; and finally, the application of criminal laws (not infrequently, tailor-made to target opponents) by pliant judges and magistrates, often retroactively. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (ACNUR) revealed that as of early 2013, the Morales regime had spawned 774 political exiles in countries such as Argentina, Paraguay, Peru, Brazil, and the United States. By 2016, the number was computed by ACNUR to have climbed to 1,232 political exiles (Diario las Américas Footnote 2016). The group comprised an assortment of business leaders, judges, human rights activists, politicians, journalists, and public servants, who left Bolivia because of political persecution (El Día 2013). The UN agency also computed the existence of 50 political prisoners. The number of high-profile opposition politicians in that group further eroded the freedom of supply in electoral contests, a basic component of free elections (Elklit and Svensson Reference Elklit and Palle1997).

Reversible Elections

Successful MAS-directed efforts to unseat elected officials undermined one of the normative premises of democratic choice: for elections to qualify as democratic, they must have consequences (Schedler Reference Schedler2002). The main avenue by which the MAS violated the principle of irreversibility was to prevent elected officers from concluding their constitutional terms. Once the MAS attained a supermajority in both chambers of the legislature, it drafted and passed the Andrés Ibáñez Autonomy and Decentralization Framework Law. Articles 144 through 147 of the Framework Law contained aspects of authoritarian legalism, defined as “the use of the law in the service of the executive branch” (Corrales Reference Corrales2015, 38).

The new law required elected authorities formally accused of a crime to leave office even without a conviction and before any evidence was presented in court, contravening the basic democratic principle of due process. Armed with this new legal instrument, courts partial to the MAS removed from their elected offices more than one hundred governors, mayors, and regional council members, including Mario Cossío, opposition governor of Tarija, and Beni governor Ernesto Suárez, who were charged with corruption. Cossío’s removal triggered a snap election in early 2011, which a MAS candidate won. Like many other removed officeholders, ex-governor Cossío went into exile—he was granted political asylum in Paraguay (Los Tiempos 2011). The MAS focused intensely on reversing electoral outcomes in opposition strongholds in the Media Luna, the eastern lowlands of Bolivia, where the greatest popular resistance to the MAS was concentrated.

In response to an unconstitutionality lawsuit brought forward by opposition lawmaker Germán Antelo, the Constitutional Tribunal ruled four articles of the Decentralization Framework law unconstitutional. However, the ruling did not have retroactive application, and the restitution of deposed officeholders was left to the discretion of regional judicial authorities and governments, many under MAS party control (La Razón 2013).

A Weaponized Legislature

Legislative dynamics in Bolivia during the MAS reign can be divided into two phases: the 2006–9 legislative term and the hegemonic decade of 2010–19. While the MAS enjoyed a majority in the Chamber of Deputies (72 seats out of 130) during the 2006–9 legislative term, it counted only a minority of 12 representatives in the Senate (out of 36 total). This reality entailed a divided government, allowing the party opposition to shape governmental decisionmaking in issue areas such as mining laws and oil contracts, among others. But the MAS’s early actions showcased a marked decay of “mutual toleration” in its treatment of the opposition. Via a panoply of tactics, including the threat to make use of executive decrees, the executive branch sought to put pressure on the Senate to comply with the MAS initiatives. Most significantly, the MAS engaged in praetorian methods: it mobilized its base and allied sectors in the streets to intimidate opposition legislators into submitting to the ruling party’s legislative agenda (Laserna Reference Laserna2010; Mayorga Reference Mayorga2011).

Contemporary competitive authoritarian regimes in Latin America (Venezuela under Hugo Chávez and Ecuador under Rafael Correa) were able to generate important asymmetries of power in relation to the political opposition by dint of constituent assemblies, which enshrined meta-rules that expanded presidential powers. This was not the case in the constitutional rewrite in Bolivia. Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution, spearheaded by the MAS, produced negligible change in presidential powers relative to the previous constitution (Negretto Reference Negretto2013), a result of the opposition’s ample nonpartisan power resources, both economic and demographic (Corrales Reference Corrales2018, chap. 6). However, the absence of a constitutionally empowered executive proved no impediment for the ensuing process of MAS-led autocratization, facilitated by the ruling party’s hegemonic position in the legislature.

From 2009 to 2019, the ruling party enjoyed more than two-thirds of the seats in the new Plurinational Legislative Assembly, enabling it to introduce self-serving constitutional reforms unilaterally. The MAS-commandeered legislature gave the green light to seminal ruptures with constitutional governance that prolonged Morales’s tenure to 14 years—and aimed at a longer period. First, the legislature endorsed the dubious legal reinterpretation (Ley de Aplicación Normativa, Law No. 381, promulgated in May 2013) that opened the door for Morales to run for a third term in 2014 (Mendoza-Botelho Reference Mendoza-Botelho2013, 51)—a piece of legislative sleight of hand similar to Alberto Fujimori’s Law of Authentic Interpretation in Peru. Second, the legislature ratified the transgressive judicial ruling that allowed President Morales to run for office for a fourth term in the 2019 elections. When the MAS’s popularity had eroded enough to (narrowly) doom Morales’s binding 2016 re-election referendum, the party’s legislative hegemony proved essential for finding a way to circumvent popular sentiment (against re-election) via a legally dubious route.

During the first half of 2010, the MAS set in place the legal basis for all-encompassing institutional capture. It ushered in the passage of crucial organic laws, in a “decisional process [that] depended on one sole political actor” (F. Mayorga Reference Mayorga2017, 46). These essential laws included the Ley de Regimen Electoral (electoral law), the Ley de Órgano Judicial (law governing the creation of the high courts), Ley del Órgano Electoral (electoral management body), and the legislation that created a new Constitutional Tribunal (TC). As detailed in this article, these institutions were packed with ruling party acolytes, their check-and-balance function neutralized and repurposed (“weaponized”) to suppress and hamper political opponents.

In line with what is observed in competitive authoritarian regimes, the post-2009 legislature during the MAS’s reign was repurposed to dispense authoritarian legalism, in the process tilting various fields of competition. The MAS legislative caucus passed laws tailor-made to colonize the judiciary and dominate the mass media ecosystem to build on incumbent advantage at election time, to target independent civil society organizations, or to directly empower the executive more generally. Let us provide examples of the latter three objectives. Not long after the MAS’s early stratagems to control the judiciary spawned a number of resignations in the national high courts, the legislature passed a tailor-made law (Ley Corta) granting the executive branch the prerogative to make direct appointments to judicial and other check-and-balance institutions where posts were vacant (Mayorga Reference Mayorga2011, 50). In 2010, the executive made use of the Ley Corta to appoint five Supreme Court justices, ten Constitutional Tribunal judges, and three members of the Judicial Council, a very consequential first maneuver in the executive branch’s enveloping capture of the judicial system.

The MAS-dominated legislature also issued legislation to control and repress civil society, effectively limiting societal accountability. In March 2013, it passed Law no. 351 (Ley de Ortogación de Personalidades Jurídicas) to grant legal status to civil society organizations, later regulated via a presidential decree. Prominent international human rights organizations condemned the law because it gave authorities overly broad powers to regulate civil society groups’ activities, “undermining the right to free association and the ability of human rights defenders to work independently” (Human Rights Watch 2014, 2). The new legal framework resulted in a “silent suicide,” as civil society organizations received countless inspections by state agencies, on which many of them “decided to either close their doors or change their goals and lower their profiles … [such that] civil society lost strength and independence” (CIVICUS 2017; see also Human Rights Watch 2017).

The MAS also designed legislation intended to hamper the electoral performance of the opposition. In late 2018, the legislature rushed through a modification to the Law of Party Organizations, which obliged all parties to conduct primaries to select the presidential and vice presidential candidates for the October 2019 general election by January 27, 2019 and prohibited contenders from renouncing their candidacy in order to support or ally with another candidate. The changed legislation contravened established legal principles, such as the ability of each political party to decide its own mechanisms of candidate selection (Zegada Reference Zegada2019, 158). The new law was intended to “wrong-foot” opposition political parties by drastically shortening their preparation time frame (only the MAS fulfilled all the new legal criteria), and crucially, to legally foreclose their ability to forge interparty alliances to compete against the MAS (Zegada Reference Zegada2019, 159).

The very few MAS lawmakers who voiced dissent with the party line or sought to introduce debate were promptly marginalized, a fate that befell the likes of Román Loayza (leader of the Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia, or CSUTCB) or Filemón Escóbar (a party founder and mentor of Evo Morales), among others (Página Siete 2017). The legislative opposition’s role in checking the power of, and scrutinizing the bills emanating from, the incumbent party was testimonial (Zegada and Komadina Reference Zegada and Jorge2014, 163–70); however, parties such as the leftist Movimiento Sin Miedo (during 2009–14) or the rightist Unidad Nacional alliance (during 2014–19) did use the platform that the Plurinational Assembly afforded, as well as the mass media, to shine light on cases of large-scale corruption (Ayo Reference Ayo2016, Reference Ayo2018) and authoritarian behavior on the part of the MAS, abetting the latter’s erosion of legitimacy.

Judicial Arena: Capture of the High Courts

The Bolivian case fully comports with the dominant scholarly paradigm in judicial politics; namely, political fragmentation yields stronger courts both through constitutional design (or judicial reform) and courts’ day-to-day operation once created, whereas dominance by one party yields the opposite outcome (Finkel Reference Finkel2008; Chávez Reference Chávez2004). In Bolivia, the MAS’s control of the legislature, unprecedented in the country’s democratic era, was vital in enabling the capture of the high courts, but the methods employed to that end were multifaceted.

Capturing the Supreme Court

The legal machinations the MAS government employed to neutralize political opponents and independents alike began almost immediately on taking office. The road to institutional capture of the high courts began when the MAS attorney general brought formal charges against the sitting chief justice of the Supreme Court (Corte Suprema de Justicia, CSJ) and current caretaker president, Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé, for his alleged role in decommissioning obsolete portable missiles belonging to the Bolivian army and sending them to the United States to destroy (Carey Reference Carey2009). For this he faced a penalty of up to 30 years in jail. The MAS government placed Rodríguez Veltzé in legal limbo and prevented his return to the Supreme Court, thereby enabling the MAS to eventually swap a chief justice widely perceived to be honest, independent, and professional for a pliable government loyalist.

In March 2006, Chief Justice Armando Villafuerte left the Supreme Court amid obscure circumstances, and a month later, Justice Carlos Rocha Orozco resigned when the salaries of justices were reduced a drastic 32 percent. Justice Alberto Ruiz Pérez quit his post, claiming health problems. At this early stage, the MAS’s relentless pressure had already provoked the opening of five seats on the Supreme Court. A year later, Justice Juan Jose González Osio resigned in reaction to political harassment stemming from the executive (Notiamérica 2007). President Morales and members of his government made frequent public denunciations against the judiciary, labeling it “the most corrupt sector of the country” (La Nación 2007a), resulting in enormous tension between the two branches of government (La Nación 2007b).

This executive branch-directed condemnation of the high courts aimed to discredit them to pave the way for the courts’ partisan capture. Using praetorian tactics that had served the party well while it was in the opposition, the MAS mobilized supporters in the streets to demand the resignation of members of the Constitutional Tribunal and the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court president, Héctor Sandoval, described the siege environment that contributed to the resignation of key members of the institution: “our dignity has never been offended in this way by a President of the Republic. We believe that with these actions [the executive] seeks to decapitate the judicial branch” (Cooperativa 2007).

By May 2007, the CSJ counted only 7 (out of 12) judges. Four new judges were appointed by Congress, but the MAS government had not yet configured a fully compliant court. In a quest to capture this important institution, the government jump-started impeachment processes against specific members of the Supreme Court in retaliation for a ruling unfavorable to the MAS. The Chamber of Deputies impeached Justices Rosario Canedo and Beatriz Sandoval. Canedo was reinstated after offering a public apology for her decision. Sandoval was absolved only by the Senate, where the MAS was in the minority. Chief Justice Eddy Fernández faced impeachment proceedings in 2009, charged with delaying the trial of former president Sánchez de Lozada. Then, Acting Chief Justice Rosario Canedo was impeached once again, accused of deliberate neglect of duty in the bankruptcy case of Banco Sur in 1994. Her removal left the CSJ without a quorum (only 6 principal justices remained). Justice Fernández resigned in early 2010. As a result of such purposeful and systematic agency, the ruling party gained de facto control of the Supreme Court from February 2010 on.

Dismantling the Constitutional Tribunal

After being catapulted to the presidency, the MAS adopted a deliberate strategy of dismantling the Constitutional Tribunal (Castagnola and Pérez-Liñán Reference Castagnola, Aníbal, Helmke and Ríos-Figueroa2011), relentlessly provoking the exit of sitting justices to neutralize this essential institution of horizontal accountability. The biggest clash arose when President Morales took advantage of a congressional recess to sign a decree (Decree 28993) to fill the four standing vacancies on the Supreme Court with interim members. The political opposition challenged this maneuver by bringing it to the attention of the TC, which ruled (in a four out of five decision) that such appointments were constitutional, but only for the duration of the recess (90 days), after which the prerogative to name replacements to the court reverted to the legislature. In response, President Morales asked Congress, where the MAS held a simple majority of seats, to initiate impeachment proceedings against the four magistrates who had made the ruling (La Nación 2007a).

Although the opposition-majority Senate acquitted the magistrates in October 2007, the MAS government issued new accusations. The last two principal justices remaining on the TC (Elizabeth Iñíguez and Martha Rojas) resigned, whereupon they denounced political persecution and public defamation. Another justice, Walter Arana, resigned after receiving physical threats. In consequence, the TC lost its quorum (requiring five justices) at the very same time that the MAS-initiated process of constitutional reform was underway, thus depriving the country of the only institution that could control the legality of such a transcendent process.

The MAS’s revealed preference was to neuter a sticky veto point in the political system by way of rendering the TC inoperative, due to the lack of the necessary quorum. Only two alternate justices and no principals remained by the end of 2007. One of them, Artemio Arias Romano, resigned shortly thereafter—at which time he publicly revealed undue pressures from the government, in line with previous resignations.

The dismantling of the Constitutional Tribunal occurred in a context of weak public support for defending its autonomy. The MAS did not utilize the typical instruments of political bargaining or collateral payoffs to neutralize this check-and- balance institution; instead, it resorted to relentless public defamation, pressure, and coercion. In a highly polarized climate, there was little political cost to pay domestically for deploying these informal tactics aimed at eroding horizontal accountability (see Svolik Reference Svolik2019).

Judicial Elections: Different Method, Enhanced Control

The publicly stated intention for instituting popular elections (in 2011 and 2017) to fill top judicial offices, as stipulated in the 2009 Constitution, was to enhance the independence and efficiency of the courts and to “democratize the judiciary.” The modality of preselection of candidates required a two-thirds majority of the legislature, a supermajority the MAS enjoyed from 2009 on. This allowed the MAS to control the process and politicize it. In practice, the preselection process was marred by a large divergence between the formal prerequisites for candidate preselection and the partisan-minded fashion in which they were chosen (Pásara Reference Pásara2015).

In privileging loyalty to the party over meritocracy, the MAS ensured that the high courts would be composed of ruling party sycophants. The MAS leadership provided its deputies and senators with a “politically cooked” list to vote as a bloc to ensure the requisite two-thirds approval (Yaksic Reference Yaksic2012, 6–7). It is symptomatic of the self-dealing character of this reform that notwithstanding its avowed objective, the six-point agenda recommendations of the National Association of Bolivian Lawyers, as well as the judicial branch’s own recommendations to prioritize judicial independence and pluralism, were brazenly ignored (Zola Reference Zola2016). In both the 2011 and 2017 judicial elections, the comprehensive and politicized truncation of candidate supply made these exercises a superfluous affair in terms of offering voters substantive choices.

All in all, the processes violated most of the best-practice norms laid out by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for candidate selection to guarantee the impartiality of a judicial system (Pásara Reference Pásara2014). Heeding the public call from the opposition, voters spoiled their ballots in record numbers, with 65 percent of votes null or blank in the December 2017 elections. The end result of this “judicial adventure,” as shown by the most comprehensive analyses of the judicial elections (Pásara Reference Pásara2014, Reference Pásara2015; Driscoll and Nelson Reference Driscoll and Nelson2015), was a captured and enormously incompetent judiciary.

Consequences: Enabling Repeated Presidential Re-election

The most important consequence emanating from the MAS’s de facto capture of the TC was the approval of President Morales’s ambition to run for a third term in office. The Masista-inspired 2009 Bolivian Constitution enshrined (in article 168) a two- term limit for the presidency, a stipulation that had explicit retroactive character; that is, it applied to terms held before the promulgation of the new constitution. Indeed, this stipulation constituted the main concession the political opposition wrestled from the MAS as a quid pro quo for acquiescing to approve the new constitution.

The MAS-controlled Constitutional Tribunal ruled that what justified a second re-election opportunity was the fact that the retroactive clause was general (i.e., applicable to all elected authorities) and “subject to being further developed by parliamentary deliberation,” as TC president Ruddy José Flores explained (El País 2013). In consequence, according to this line of argument, the national legislature enjoyed the prerogative to decide how to apply the retroactive clause. The MAS-drafted Ley de Aplicación Normativa, approved in 2013, stipulated that Bolivia had been newly founded at the time of the 2009 Constitution, which ushered in a Plurinational State to substitute for the old republic, and consequently Morales’s first term did not count.Footnote 3

The Bolivian Constitutional Tribunal’s ruling buttressed the contorted rationale enshrined in the Ley de Aplicación Normativa, thereby giving the green light to Morales’s unconstitutional third term in office (Cortez Salinas 2014). This goes along with what Landau (Reference Landau2013) labels “abusive constitutionalism,” the use of mechanisms of constitutional change by incumbents who want to stay in power, subverting the democratic order. The ruling party’s loss of a February 2016 referendum to lift the constitutional restrictions on presidential re-election showcased in stark fashion the limitations of the MAS’s plebiscitarían strategy for power accretion (Welp and Lissidini 2016)—in the context of lower popularity levels after a decade in office.

Amid receding social hegemony (popularity), competitive authoritarian regimes come to rely more for their political survival on the institutional hegemony they have carefully constructed. With polls throughout 2017 showing that 60 percent of Bolivians deemed Morales’ re-election illegal and 75 percent opposed his unlimited re-election (Centellas Reference Centellas2018, 163), the MAS studiously avoided placing the decision in voters’ hands and instead rerouted the matter to the same high courts it had successfully captured. In November 2017, the Constitutional Tribunal made another momentous decision when it suspended the articles of the constitution that prohibited two consecutive re-elections and granted Evo Morales the right to run in the 2019 presidential contest (El País 2017). In justifying its verdict, the court revealingly mimicked the reasoning of the ruling party—namely, that the constitutional clauses that limited the re-election of authorities infringed on the political rights of both officials and voters (EIU 2017). It was the MAS’s continued control of the Constitutional Tribunal that enabled the chief executive’s second flagrant rupture of the constitutional order (after the one effected in 2013).

Mass Media Outlets: MAS Control and Repression

As in Ecuador and Venezuela, the crisis of representative institutions in Bolivia was “paralleled by a crisis in media credibility” (Kitzberger Reference Kitzberger2012). This facilitating condition paved the way for, and lowered the political cost of, the Morales government’s campaign of delegitimation directed against private mass media from the very early days of its tenure. Verbal attacks on journalists and media outlets by President Morales and high-ranking government officials became frequent. The MAS utilized three strategies to establish a hegemonic position in the mass media ecosystem: a campaign to gain the editorial content of outlets critical of the government, changes in the legal system to stifle critical reporting, and the use and abuse of state agencies to repress independent outlets and journalists.

The less visible mechanism the ruling party employed to skew the mass media playing field was a silent campaign for editorial control of key mass media outlets (Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014). Several TV stations and newspapers turned into progovernment outlets after being acquired by business leaders with ties to the ruling party. Vice President García Linera became a key driving force behind the conversion of several major media outlets into MAS allies (CPJ 2014b), naming the directors of such outlets and controlling their content. The MAS government constructed a network of parastatal outlets (i.e., functioning for the state without being part of the public administration) that included the television channels ATB, PAT, Full TV, and Abya Yala TV, as well as the newspapers Extra and La Razón. With the exception of Abya Yala TV, all were bought via MAS-friendly business leaders, who then ceded informational and editorial content of such outlets to the government, as renowned investigative journalist Raul Peñaranda has documented with inside sources in his monograph Control Remoto (2014, chap. 1), These outlets received large advertising financing from the government (Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014, chap. 2). La Razón and Extra were the best-selling newspapers in La Paz, while ATB was the TV station with the highest ratings. The critical reporting about the Morales administration on display before the takeovers became progovernment coverage thereafter (see Molina Reference Molina2015; Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014). Examples from three key outlets follow.

La Razón, the largest daily newspaper in La Paz, was highly critical of the government throughout much of the first Morales term. After a series of labor inspections and tax audits, the daily was sold in 2008 to Carlos Gill, a Venezuelan businessman friendly with President Hugo Chávez. Thereafter, content analysis reveals that 56 percent of La Razón’s articles were laudatory of the government and only 3 percent critical (CPJ 2014a). A study of the channels ATB and PAT after their takeover shows that they halved the coverage devoted to economic and political information of national relevance while doubling the coverage of nonpolitical information (Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014, 72–73). The information these channels provided using government sources stood at 80 percent for ATB and 87 percent for PAT, while news sourced from the opposition constituted merely 13 and 19 percent, respectively (Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014, 77–78).

The change in their ownership and editorial content thus significantly reduced the projection of independent and opposition voices in the mass media ecosystem. The daily Página Siete, created with the intention of filling the resulting dearth of high-quality independent journalism (Peñaranda Reference Peñaranda2014, chap. 5), soon incurred the MAS’s wrath after publishing exposés on government corruption. Advertising from state-run entities dried up, and the government filed a criminal complaint against Página Siete for inciting racism, prompting the resignation of the newspaper’s editor (CPJ 2013).

A second weapon utilized by the ruling party was the enactment of legislation deliberately aimed at limiting journalistic freedom. Early in its tenure, the MAS government dusted off archaic Bolivian legislation that restricted freedom of speech. The Ley de Desacato, or Defamation Law (article 16 of the Penal Code), issued penalties of one month to two years in jail to anyone who defamed a public official in the exercise of his or her duties, with heavier penalties if the injured party was the president, a lawmaker, or the magistrate of a high court. The law can be traced to 1972, while Bolivia was under the military rule of Hugo Banzer, but no democratic government had made use of it.

Between 2006 and 2012, the interlude during which the government rendered the law operative, members of the MAS brought forward charges of defamation against 21 opposition politicians and citizens, each of whom faced from 1 to 20 charges. They included Santa Cruz governor Ruben Costas, Unidad Nacional leader Samuel Doria Medina, La Paz mayor Luis Revilla, and senator Roger Pinto (La Razón 2012).

The Constitutional Tribunal ruled defamation charges unconstitutional in 2012. The high level of controversy the defamation law generated, coupled with pressure from international organizations for its annulment, put enough pressure on the TC to eventually rescind it. Changes in the legal code restricting a free press came not only from the MAS-controlled legislature but also from the executive branch. For example, under Supreme Decree 181 (issued in 2009), journalists perceived to “lie,” “play party politics,” or “insult” the government were denied income from state advertising, creating “financial pressure on many outlets,” according to Reporters Without Borders (2016)—a verdict aligned with that of other international NGOs that monitor freedom.

Another legal initiative that limited freedom of expression was the MAS-sponsored Antiracism Law, passed in 2010. The law punishes racist or discriminatory statements with fines, the loss of broadcast licenses, and prison sentences of up to five years. While generally not enforced by the judicial system, this law (along with the Defamation Law) “contributed to a climate of self-censorship,” according to Freedom House (2015). The climate for freedom of the press and freedom of expression continued to worsen throughout the MAS’s tenure. By the year 2019, Reporters Without Borders placed Bolivia 113th in the world (out of 180 countries) in press freedom, a ranking congruent with that of electoral authoritarian regimes—such as Nicaragua (114), Gabon (115), and Ethiopia (110).

The third strategy the MAS government used assiduously was to repurpose state institutions for the task of media repression. Regulatory agencies charged independent mass media outlets with infractions, such as tax evasion, labor code violations, or airing prohibited content. Public officials from the Internal Revenue Service were “systematically deployed” to solicit documentation whenever an outlet reported information that was “disagreeable to the government,” according to the Inter-American Press Society (Sociedad Interamericana de Prensa, SIP 2015). The misuse of the security apparatus for partisan purposes to cripple the opposition and stifle dissent is a common modus operandi of competitive authoritarian regimes. The MAS government partook of these tactics: the police department’s intelligence services were found to spy on targeted television network directors and politicians (CPJ 2010).

The first reported victim was Juan José Espana, news director of the private TV channel Unitel. Reporters Without Borders (2008) made news in Bolivia when it reported that at least 18 opposition politicians, including Jorge Quiroga, four governors, two MAS parliamentarians, and Senate speaker Oscar Ortiz, were being spied on. The MAS government also deployed the police to attack and assault reporters, including those from TV channel Red PAT and Unitel (Boas Reference Boas, Jorge and Shifter2013, 61). These actions, coupled with the aforementioned legislation, had a chilling effect on Bolivian journalism. A 2011 poll revealed that 92 percent of journalists from La Paz, Cochabamba, and Santa Cruz believed that freedom of expression was under threat in Bolivia (Página Siete 2011).

Leveraging V-DEM Indicators for Regime Classification

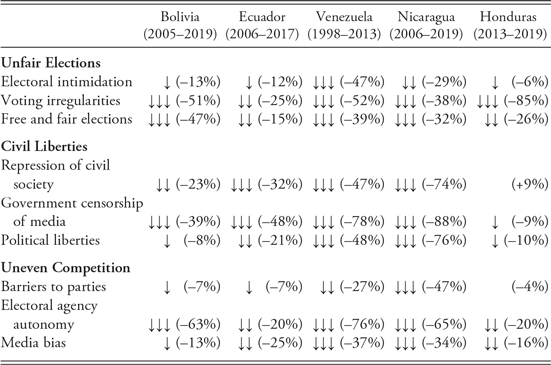

The indicators of the Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) project can be fruitfully used to situate and compare countries across a democracy to autocracy continuum. Three key indicators gauging each of the three criteria (free and fair elections, civil rights, slope of the playing field) laid out by Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010) are used here. In selecting these indicators from a plethora of V-DEM options, we strictly follow Handlin’s content validation advice (Reference Handlin2017, 55)—employing the proposed markers and thereby avoiding arbitrary self-selection in the choice of indicators. To evaluate the degree to which elections are unfair, we use the V-DEM indicators Electoral Government Intimidation, Voting Irregularities, and Free and Fair Elections. To gauge the extent to which civil liberties are violated, we make recourse to the indicators Political Liberties (freedom of expression and freedom of association), Repression of Civil Society, and Government Censorship of Media. In seeking to assess the degree to which the opposition faces an uneven playing field of competition, we rely on the variables Barriers to Parties, Electoral Management Body Autonomy, and Media Bias.

In table 1, scores for Bolivia across all nine indicators are compared with those of four electoral authoritarian regimes in Latin America, the classification of which commands widespread scholarly agreement: Ecuador under Correa, Nicaragua under Daniel Ortega, Venezuela under Chávez, and Honduras under Orlando Hernández. Following Levitsky and Loxton’s measurement criteria (Reference Levitsky, James and de la Torre2019, 345) while introducing more fine-grained distinctions (three levels of decay rather than two), we operationalize deteriorations in civil liberties, electoral fairness, and an even playing field as follows: large (↓↓↓) for those greater than 30 percent, medium (↓↓) if they register between 15 and 30 percent, small (↓) if they register between 5 and 15 percent, and no meaningful change if they register below 5 percent. A regime is deemed to violate a dimension if at least one of its three indicators displays a large decline, an operationalization in line with that of Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2010) in assessing civil and political rights, elections, and the fairness of the playing field.

Table 1. Declines in Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) Scores

The deterioration across all nine indicators in Venezuela under Chávez and Nicaragua under Ortega (2007–19) is drastic. The democratic erosion in these two polities—which have transited into forms of hegemonic authoritarianism—is of an order of magnitude greater than what the scores show for the regimes of Morales, Correa, and Hernández. Overall, the declines in the V-DEM indicators in Ecuador and Bolivia are of the same order of magnitude: Ecuador shows a higher media bias and repression of civil society, while Bolivia shows a much more pronounced decline in the autonomy of the electoral agency.

Bolivia’s V-DEM score declines place it in the vicinity of Honduras as well; however, serious democratic infringements are observed across more indicators in Bolivia than in Honduras. Morales’s regime shows declines across all nine indicators, displaying large deteriorations in free and fair elections (47 percent), government censorship of mass media (39 percent), the autonomy of the electoral agency (63 percent), and voting irregularities (51 percent). It displays a medium-scale decline in repression of civil society (23 percent). Thus, Bolivia displays all three of the individually sufficient traits observed in competitive authoritarian regimes: unfree and unfair elections, regime-sponsored violations of civil rights, and an uneven playing field of competition.

The deterioration in Bolivia’s V-DEM “free and fair” score was drastic in 2019, but the accumulated decline was modest up to 2018 (8 percent). However, four essential observations are in order, one for each of the four important violations of democratic elections in Bolivia highlighted in this article. The first element in violation of free and fair elections was a highly progovernment electoral management body (as corroborated by V-DEM scores), while the other three dimensions are not independently measured by the V-DEM project: disparities in access to resources, free electoral supply, and irreversibility of electoral contests. (V-DEM does measure access to public finance, showing it to be negligible after 2008 and virtually zero from 2013 on, which hampered the opposition). A full accounting of the fairness and freedom of elections that takes into consideration the nature of the playing field—access to the law and the state, to resources, and to media—reveals substantial pro-incumbent biases in the electoral field, as documented here. Thus, on the basis of Levitsky and Way’s more demanding and wide-ranging operationalization (Reference Levitsky and Way2010, 366–68), Bolivia under Morales certainly did not pass the test of free and fair elections before 2019.

Conclusions

This work has delineated the legal as well as informal maneuvers the MAS utilized to slant the playing field in four fields of contestation, rendering political competition fundamentally unfair. The fairness and freedom of elections was violated by purging and refashioning an electoral management body to make it subservient to the MAS, while the freedom of electoral processes was compromised by the repeated truncation of the supply of electoral candidates, at all levels of government, including presidential contests. The MAS also engineered enormous disparities in access to resources compared with the opposition via the extensive patrimonialization of the state. In addition, elected authorities from the opposition were removed from power after coming to office, violating the irreversibility of elections.

The ruling party’s de facto circumvention of the binding 2016 nationwide referendum on re-election constituted the most egregious and politically consequential violation of the principle of irreversibility. These undemocratic maneuvers were carried out via courts armed with newly approved legislation that constituted autocratic legalism (see Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018), crafted for the purpose of hampering the opposition. The MAS also weaponized the legislature, utilizing the supermajority it enjoyed in both chambers after 2009 to churn out legislation that helped it repress civil society, the media, and the political opposition. The MAS neutralized the judiciary as an institution of horizontal accountability by dismantling the Constitutional Tribunal and capturing the Supreme Court, thus enabling the onset of abusive constitutionalism, as well as the repeated circumvention of presidential term limits. Furthermore, the MAS overhauled the mass media ecosystem through a panoply of actions, including the forced sale of some privately owned outlets, the use of politicized tax audits, the investigation of media owners, and the crafting of legislation constraining freedom of speech.

The ouster of the MAS government in December 2019 constituted a coup d’état. Evo Morales resigned under public pressure from General Williams Kaliman, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, to “stand down,” amid a rising social and political crisis manifested in widespread nationwide protests in the wake of the fraudulent 2019 general elections. The MAS’s competitive authoritarian regime counted with a strong ruling party, but it was otherwise built on weak structural foundations (economic resource dependence, a weak state, feeble institutions, etc.). The end of the commodities boom, coupled with growing ruling party authoritarianism and increasing public evidence of government corruption, lost the Morales regime a large segment of the middle class, and with it, majority support. The ruling party’s overt and growing abuse of power raised the political stakes for all contending political actors, lowering the opposition’s incentives to play by (subverted) democratic rules.

This background, and the trigger of misguided political agency (a falsified election), paved the way for the damaging civilian recourse to the military as an arbiter of last resort. The praetorian means via which the Morales government was ousted, coupled with authoritarian behaviors on the part of the interim Jeanine Añez government (which included certified human rights violations and a revanchist judicial persecution and public demonization of the MAS), subsumed Bolivia’s polity in yet another round of sociopolitical polarization and instability. Alongside other contemporary hybrid regimes, the Bolivian MAS government offers comparativists an important research agenda; namely, the relationship between electoral authoritarian rule, radicalization-cum-polarization, and the role of militaries in adjudicating high-stakes political disputes.