Introduction

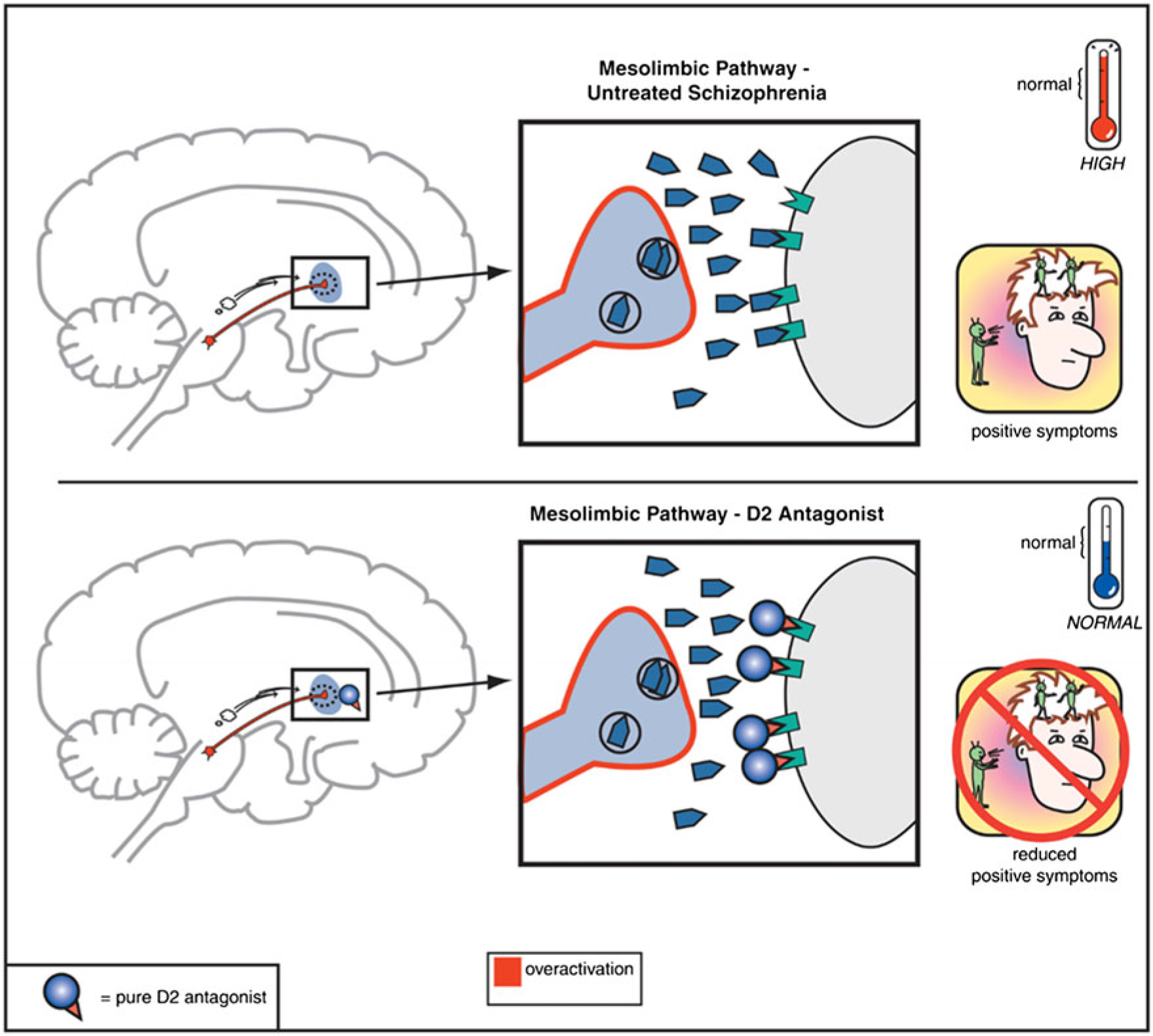

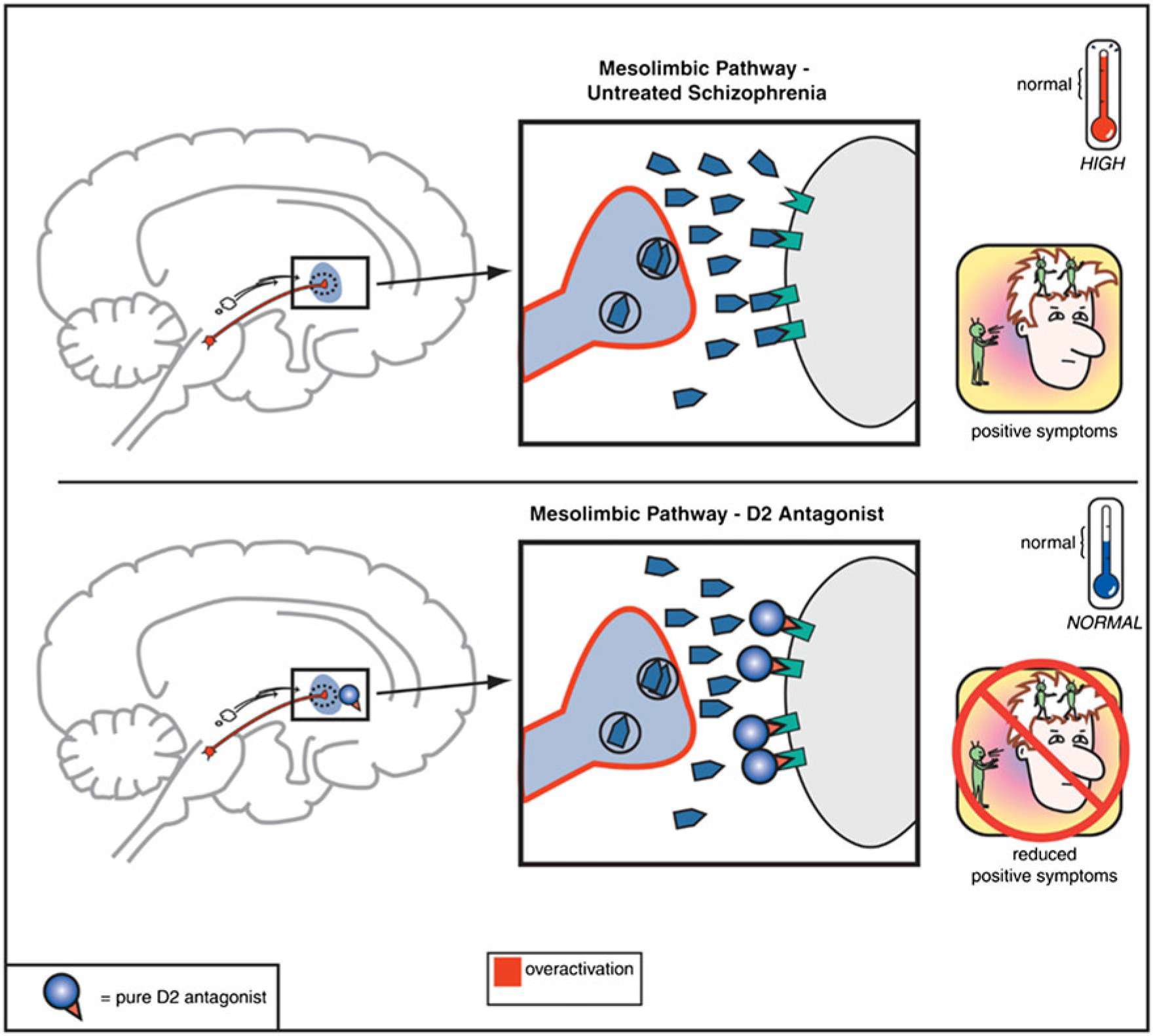

In community settings, the principle barriers to independent living, stable relationships, and gainful employment arise from the negative and cognitive symptom domains of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.Reference Grove, Tso and Chun 1 , Reference Kaneko 2 In contrast, the positive symptoms of psychosis often are the gateway (e.g., via persecutory delusion associated with anger) to arrest and criminalization for the mentally ill.Reference Ullrich, Keers and Coid 3 , Reference Fazel, Zetterqvist, Larsson, Langstrom and Lichtenstein 4 Since the clinical discovery of chlorpromazine in 1952, dopamine antagonism in the mesolimbic dopamine circuit has been central to treating the positive symptoms of psychosis.Reference Urs, Peterson and Caron 5 , Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Owen and Murray 6 The hyperactivity of the mesolimbic circuit and the normalizing effects of the dopamine antagonist antipsychotics are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Mesolimbic pathway and D2 antagonists.

In this review, we seek to understand the roles of dopamine antagonist antipsychotics, including the use of long-acting or depot formulations and plasma concentrations, in controlling the positive symptoms of psychosis, thereby supporting decriminalization of those suffering from psychotic disorders.Reference Rotter and Carr 7

Principle Text

The French pharmaceutical firm, Rhône-Poulenc, began exploring polycyclic antihistamine compounds in 1933. This led to the approval and clinical introduction of diphenhydramine in 1946. Promethazine, a phenothiazine derivative, was approved the following year. Although this compound produced sedation, decreased motor activity, and indifference to stimulation in rats, it had much more limited effects in humans.

In 1948, a French surgeon named Pierre Huguenard began using a combination of promethazine and pethidine (a.k.a. meperidine), an opioid, as preoperative medications to calm and sedate patients. Henry Laborit, another French surgeon, subsequently proposed to Rhône-Poulenc that a more effective replacement for promethazine be sought. Consequently in December 1950, the chemist Paul Charpentier produced various compounds related to promethazine, including RP-4560 or chlorpromazine.

Chlorpromazine appeared to be the most promising compound because of its lesser peripheral effects. Chlorpromazine was distributed for testing in humans between April and August 1951. In this context, Henry Laborit tested chlorpromazine at the Val-de-Grâce Military Hospital in Paris. Dr. Laborit found the drug effective, as it produced a state akin to artificial hibernation. In fact, Dr. Laborit became such a proponent of chlorpromazine that it became colloquially known as “Laborit’s drug.”

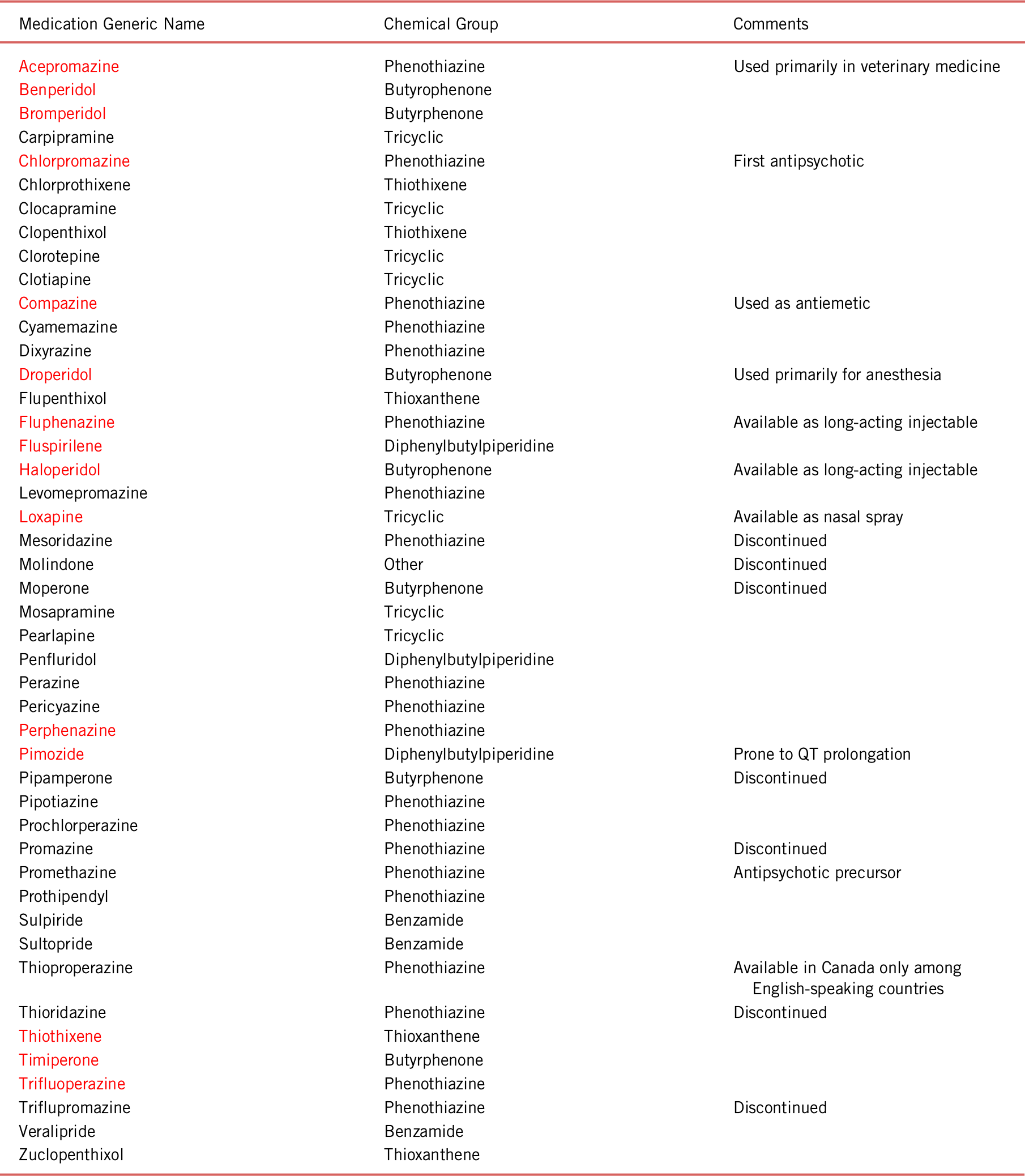

Nevertheless, chlorpromazine’s use as a preoperative drug was cut short by its propensity to induce orthostatic hypotension and syncope via antagonism at α-adrenergic receptors. Despite this failure, a French psychiatrist named Pierre Deniker had been aware of chlorpromazine and was interested in using it to calm psychotic and manic patients at St. Anne’s Hospital in Paris. Dr. Deniker’s application of chlorpromazine to psychiatric patients was supported by Professor Jean Delay, who was the superintendent of St. Anne’s during that time. Treatment with chlorpromazine proved more successful than Dr. Deniker and Dr. Delay had hoped. It reduced positive psychotic symptoms such as delusional ideation and hallucinations. Additionally, it calmed agitated and regressed behaviors while promoting emotional stability. Consequently, the success of chlorpromazine in psychiatry was likened to the discovery of antibiotics with respect to medical importance. Chlorpromazine’s achievement led to the development of first-generation antipsychotics, several of which continue to be used clinically today (see Table 1).Reference Lopez-Munoz, Alamo, Cuenca, Shen, Clervoy and Rubio 8

TABLE 1. First-generation dopamine antagonists

Notes: Derived from the U.S. and E.U. Pharmacopeias (WWW.USP.ORG and WWW.EDQM.EU)

Red indicates those medications in common use in the United States.

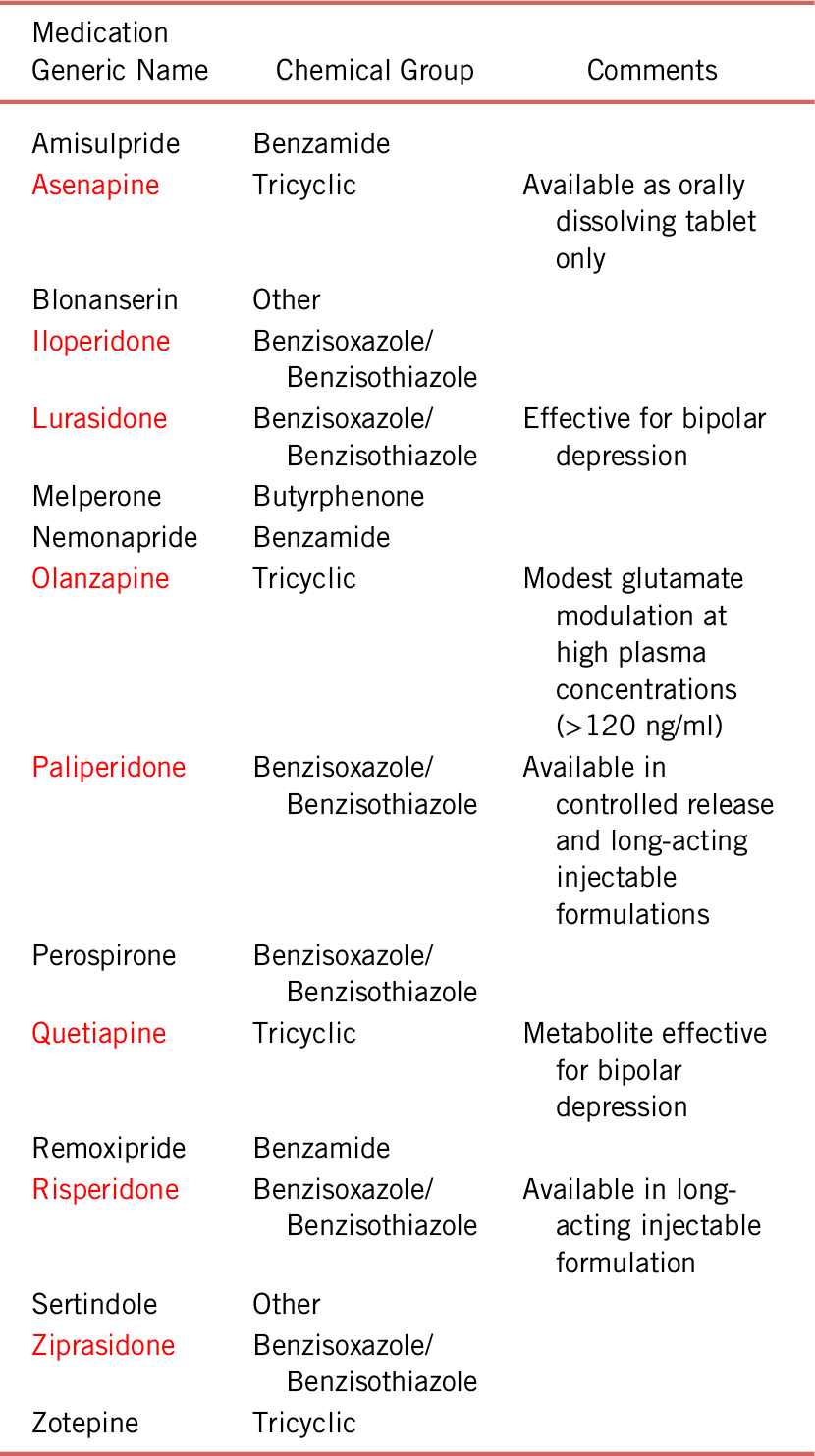

Clozapine, the first second-generation antipsychotic, was synthesized by Schmuts and Eichenberger in 1958. It has since become the gold standard for the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia and pointed to pathological mechanisms in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders beyond dysregulation of dopamine (i.e., glutamate hypoactivity and, perhaps, muscarinic hypoactivity).Reference Melkersson, Lewitt and Hall 9 The success of clozapine and its difficult adverse effect profile ignited substantial research in pursuit of antipsychotics that would be as effective as clozapine but with an improved safety profile.Reference Crilly 10 This plethora of research resulted in the synthesis and approval of several second-generation dopamine antagonists (see Table 2).Reference Shen 11

TABLE 2. Second-generation dopamine antagonists

Notes: Derived from the U.S. and E.U. Pharmacopeias (WWW.USP.ORG and WWW.EDQM.EU)

Red indicates commonly in use in the U.S.

Mechanisms

Despite various chemical subtypes, a wide range of potencies at dopamine D2 receptors and important differences in side-effect profiles based on affinities for and actions at other receptors (i.e., adrenergic, histamine, acetylcholine, serotonin receptors, etc.), all of the dopamine antagonist antipsychotics share a principle mechanism for exerting their antipsychotic effects, namely, induction of depolarization blockade at the dopamine neurons that give rise to the mesolimbic dopamine pathway.Reference Grace 12 For the first-generation antipsychotics, this depolarization blockade accounted for circa 92% to 93% of antipsychotic efficacy for these drugs.Reference Miyamoto, Duncan, Marx and Lieberman 13 Among the second-generation antipsychotics, dopamine antagonism and depolarization blockade remains the likely principle mechanism of action, although some (e.g., olanzapine) may exert modest antipsychotic effects via the modulation of glutamate signal transduction.Reference Howes, McCutcheon and Stone 14 In this context, clozapine is unique in that it likely provides little, if any, of its antipsychotic efficacy via direct effects on dopamine signaling, instead more likely acting via robust modulation of glutamate.Reference Veerman, Schulte and de Haan 15 Thus, the first step in treating positive psychotic symptoms is to provide the patient with an adequate exposure to the initial chosen dopamine antagonist antipsychotic for an adequate amount of time.

Antipsychotic Trials

A recent consensus paper identified the parameters of an adequate antipsychotic trial as a trial of at least 6 weeks duration and a dose of at least 600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents. A duration of 4 months was given for long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Because medication adherence is often poor, this paper held a single antipsychotic plasma concentration measurement to be a minimal standard, while a more optimal standard was held to be two plasma concentration measurements separated by at least 2 weeks without prior notification of the patient. A further important principle of adequate antipsychotic trials is pursuit of the trial until one of three endpoints is achieved: improvement of psychotic signs and symptoms; emergence of intolerable adverse effects that cannot be managed via reasonable interventions; or, a point of futility is reached, for example, saturation of D2 dopamine receptors or flattening of the drug’s receptor occupancy curve.Reference Howes, McCutcheon and Agid 16

Importantly, failure to achieve a 20% to 30% reduction in psychotic symptoms in response to two or more adequate dopamine antagonist trials indicates that the patient is treatment-resistant; that is, the patient exhibits a pharmacodynamic failure in response to adequate dopamine antagonism. Additionally, such treatment resistance portends a poor probability of response to most antipsychotic agents. Most first- and second-generation antipsychotic medications show a response rate of 0% to 5% among such patients, while high plasma concentration olanzapine (120–200 ng/ml) produces a response rate of about 7%.Reference Stroup, Gerhard, Crystal, Huang and Olfson 17 Moreover, data suggest for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients that responsiveness to even clozapine begins to decline at about 2.8 years of treatment-resistant status.Reference Yoshimura, Yada, So, Takaki and Yamada 18 The low probability of response to antipsychotics other than clozapine combined with data indicating a response-decay curve to even clozapine after 2.8 years among treatment-resistant schizophrenia-spectrum disordered patients argues strongly in favor of clozapine treatment as soon as strictly defined treatment resistance is identified. That is, further time should not be wasted in pursuing treatments with a low probability of success, thereby diminishing even the superior efficacy of clozapine in patients who are pharmacodynamic failures with respect to dopamine antagonism.Reference Kerwin 19 , Reference Doyle, Behan and O’Keeffe 20

In the context of treatment-resistant schizophrenia, it is also worth noting that although there are a number of augmentation strategies ranging from antipsychotic polypharmacy to addition of medications from additional classes, the effect sizes of these strategies have been described as small or modest.Reference Galling, Roldan and Hagi 21 Exceptions to this analysis include augmentation with mood stabilizers in schizophrenic patients exhibiting early acute psychomotor agitation or in patients exhibiting a mood component or bipolar diathesis.Reference Stahl, Morrissette and Cummings 22 – Reference Garriga, Pacchiarotti and Kasper 24 It is also worth noting that dopamine partial agonist antipsychotics may be more effective for the negative and cognitive symptom domains of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders than the positive symptom domain.Reference Mossaheb and Kaufmann 25 – Reference Stahl 27

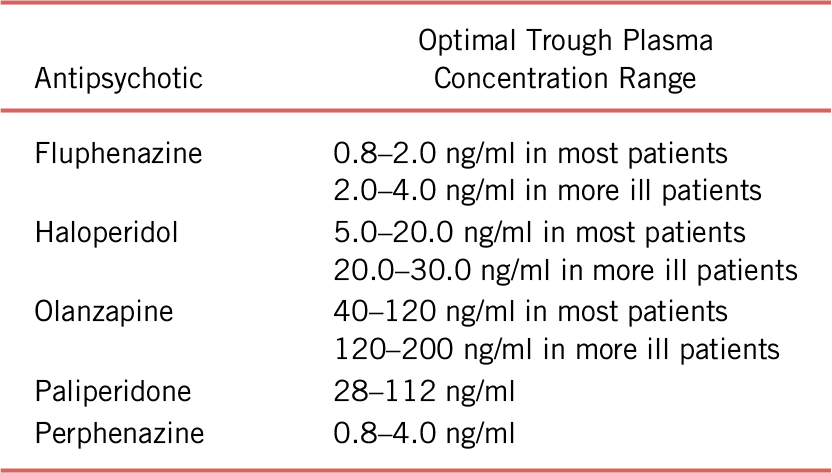

The second route to treatment failure for the dopamine antagonists is pharmacokinetic. In general, data have suggested that for the dopamine antagonists, optimal antipsychotic response occurs when dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancies are roughly in the 60% to 80% range.Reference Wulff, Pinborg and Svarer 28 This is why assuring adequate receptor occupancy for an adequate period of time is critical to providing an adequate dopamine antagonist trial.Reference Howes, McCutcheon and Stone 14 In this context, it is worth noting that plasma concentrations of the antipsychotics correlate much more tightly with relevant receptor occupancies than the prescribed dose.Reference Urban and Cubala 29 Numerous factors can affect the relationship between dose and plasma concentration, including adherence, absorption, distribution, catabolism, and elimination.Reference Fan and de Lannoy 30 Hence, measuring antipsychotic plasma concentrations provides a much more precise and accurate means to assuring adequate receptor occupancy. (Please see the companion article in this issue entitled, “Monitoring and Improving Antipsychotic Adherence in Outpatient Forensic Diversion Programs,” by Meyer, J.M.)

Optimal plasma concentration ranges for selected dopamine antagonist antipsychotics are shown in Table 3.Reference Meyer, Cummings, Proctor and Stahl 31 , Reference Stahl, Morrissette and Cummings 22

TABLE 3. Optimal plasma concentration ranges for selected dopamine antagonist antipsychotics

Note: Derived from the California Department of State Hospitals Psychotropic Medication Policy, Chapter 41, Appendix – Therapeutic Plasma Concentrations for Antipsychotics and Mood Stabilizers (2019).

Measuring plasma antipsychotic concentrations can be useful in various clinical circumstances ranging from benchmarking an optimal clinical response to assessing poor or extensive metabolism or investigating the clinical decompensation of a previously stable patient.Reference Dahl 32

While patient factors such as drug absorption, distribution, catabolism, and elimination play important roles in determining antipsychotic efficacy, they often pale in importance when compared with medication adherence.Reference Tharani, Farooq, Saleem and Naveed 33 This is especially true in forensic settings, where medication diversion often becomes an added challenge.Reference Pilkinton and Pilkinton 34 The use of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics provides the most reliable means to address issues of non-adherence or diversion.Reference Marcus, Zummo, Pettit, Stoddard and Doshi 35 Because decriminalizing a portion of the arrested mentally ill population would involve release to community settings, assurance of continued treatment becomes a critical requirement for the success of any such program.Reference McGuire and Bond 36 Additionally, it is worth noting that LAI antipsychotics have been associated with decreased rates of violence and criminality when compared with their oral counterparts.Reference Mohr, Knytl, Vorackova, Bravermanova and Melicher 37 In fact, the benefits of LAI antipsychotics are such that they produce an approximately 30% reduction in mortality risk when compared with the same antipsychotics prescribed in oral formulations in schizophrenia-spectrum disordered patients.Reference Taipale, Mittendorfer-Rutz and Alexanderson 38

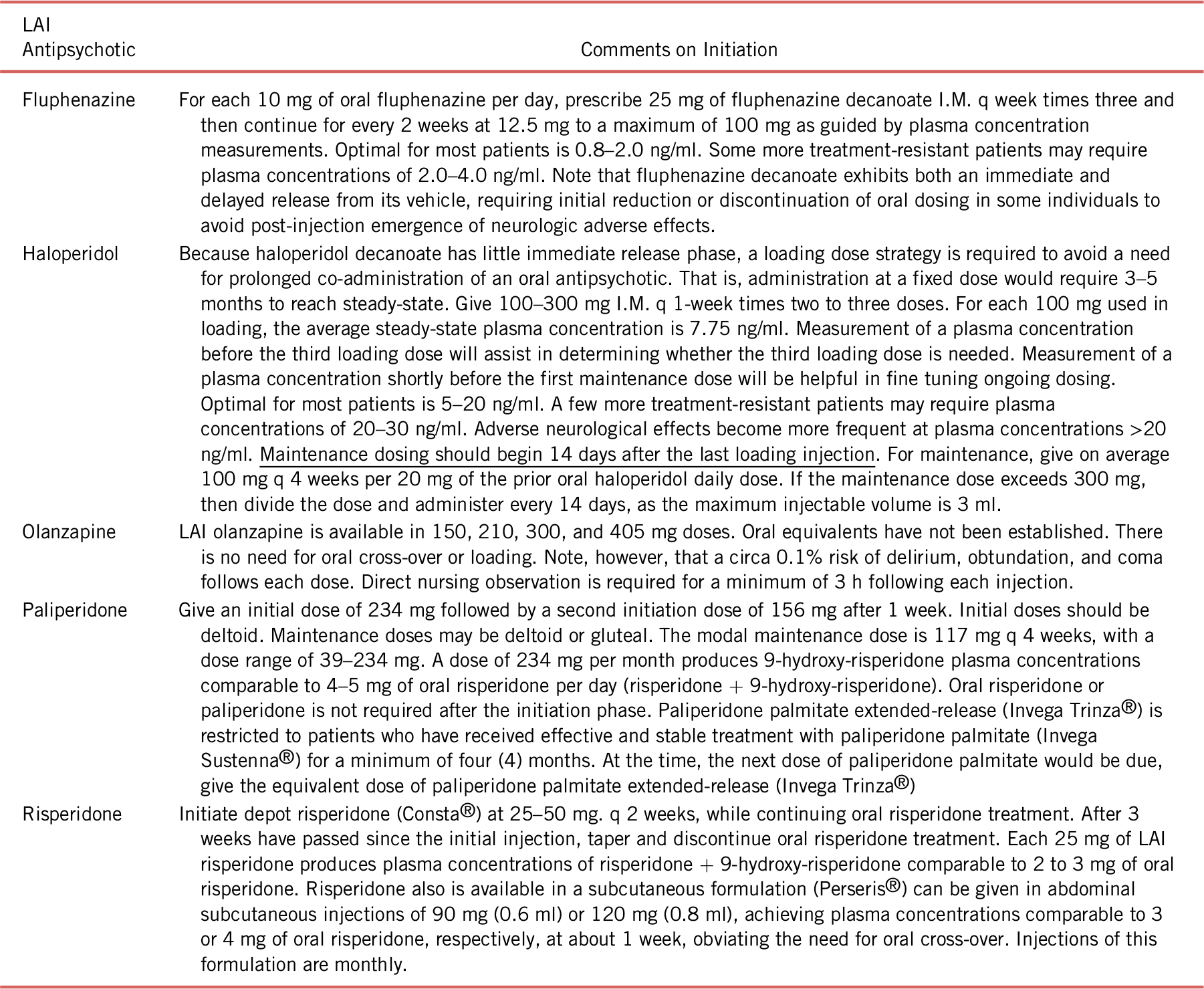

Unfortunately, LAI antipsychotics are infrequently used and thus are less familiar.Reference Iyer, Banks and Roy 39 In particular, clinicians may be unfamiliar with strategies for initiating LAI antipsychotic treatment or transitioning from oral to depot formulations of dopamine antagonist antipsychotics.Reference Siragusa and Saadabadi 40 – Reference Citrome 43 Initiation/transition strategies are summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4. LAI dopamine antagonist antipsychotic initiation

Notes: Derived from the California Department of State Hospitals Psychotropic Medication Policy, Chapter 09, Depot Antipsychotics (2019).

Also derived from package inserts for olanzapine (Zyprexa Relprevv®), paliperidone (Invega Sustenna® and Invega Trinza®), and risperidone (Risperdal Consta®), as well as references 40, 41, 42, and 43. Web sites: WWW.DrugInserts.COM/lib/rx/meds/Zyprexa-Relprevv-1; WWW.InvegaSustenna.COM; WWW.InvegaTrinza.COM; and, WWW.DrugInserts.COM/lib/rx/meds/Risperdal-Consta-1.

Conclusions

While negative and cognitive psychotic symptoms are major barriers to successful social functioning and employment in the community at large, it is more often positive psychotic symptoms that result in behaviors that lead to arrest and criminalization. Dopamine antagonist antipsychotics provide the cornerstone of treatment for positive psychotic symptoms and may provide an effective means to divert the mentally ill from the path of criminalization and incarceration. Critical to their success, however, are antipsychotic trials of therapeutic dose/plasma concentration for an adequate period of time. Moreover, such medication trials should be pursued to one of three endpoints: (1) successful improvement of psychotic signs and symptoms; (2) emergence of intolerable adverse effects that do not respond to reasonable interventions; or (3) arrival at a point of futility (e.g., saturation of D2 dopamine receptors or flattening of the medication’s receptor occupancy curve).

In those patients who have pharmacodynamic failures of two adequate trials of first- or second-generation dopamine antagonist antipsychotics, a trial of clozapine should be pursued vigorously. This is true because other antipsychotics, with or without augmentation, are unlikely to produce an adequate response in patients with strictly defined treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Moreover, some data indicate that even clozapine’s efficacy in this context begins to fade after treatment resistance has been present for 2.8 years. Thus, our treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients would be better served if we clinicians do not waste time pursuing multiple antipsychotic trials or seemingly endless augmentation trials which are not likely to be successful.

With respect to pharmacokinetic failures, it should be emphasized that plasma concentrations are a much better means to assess antipsychotic trial adequacy than medication dose. In this context, it must be acknowledged that the failure of medication adherence is a major cause of pharmacokinetic failure. In short, if the medication does not make it into the patient, then there is no hope for an adequate antipsychotic response. Moreover, the issue of adherence is especially important to decriminalization of the mentally ill, as such individuals would return to the community as an inherent goal of decriminalization. To date, the only formulations of the antipsychotics that we clinicians can be certain are reliably making it into the patient on an ongoing basis are the long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In fact, data indicate that these formulations produce superior antipsychotic responses and even reduce mortality when compared with their oral counterparts. They are nevertheless underutilized, often being thought of as medications “of last resort”. Instead, the available data support that the long-acting injectable antipsychotics should be one of our most frequently used tools, especially in forensic populations.

Disclosure

Dr. Cummings, Dr. Proctor, and Dr. Arias declare that they have nothing to disclose.