Introduction

Dementia is a serious issue in Canada, affecting nearly half a million Canadians (Bergman, Reference Bergman2019; Government of Canada, 2019) and costing the health system $15 billion a year to manage (Bray, Strachan, Tomlinson, Bienek, & Pelletier, Reference Bray, Strachan, Tomlinson, Bienek and Pelletier2014). In an effort to address this problem, the Canadian Government launched a National Dementia Strategy in 2019, which provides a central vision for the effective treatment of dementia (Government of Canada, 2019). Among the strategy’s key objectives is to “prioritize quality of life for people living with dementia and caregivers” (Government of Canada, 2019). One way to support this goal is by refocusing dementia care to take place more in community and primary care settings, which are better situated for early detection of cognitive issues and coordination of care (Bergman, Reference Bergman2019; Warrick, Prorok, & Seitz, Reference Warrick, Prorok and Seitz2018). However, the complex nature of dementia and the needs of those living with dementia and care partners make it particularly challenging for primary care providers to deliver dementia care without additional resources (Pimlott et al., Reference Pimlott, Persaud, Drummond, Cohen, Silvius and Seigel2009).

The Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI) is a not-for-profit organization funded by Health Canada to create partnerships and spread innovations supporting better health care delivery. They have sought to identify innovations to support the implementation of key pillars in the National Dementia Strategy and inform a potential program focused on strengthening community- and primary care-based dementia care, in partnership with organizations, health care providers, and people with lived experience across Canada, with a particular focus on early diagnosis of dementia, care coordination, and navigation of care for people living with dementia (PLWD) and their care partners.

In support of the CFHI’s community-based dementia care program development, we conducted an environmental scan to (1) identify primary care-based models of dementia care appearing in published literature, (2) identify dementia-related strategies and resources supporting the implementation of these models, and (3) examine models’ effectiveness in improving quality of life for PLWD and their care partners.

The results of this study are relevant not only for the CFHI’s program development, but also for those seeking to gain a comprehensive understanding of dementia care delivery and support in primary care settings across Canada.

Methods

Design

We used a multi-method approach to identify and examine models, strategies, and resources for dementia care, with a focus on those that currently exist in Canada. Our methods included (1) a scoping review of academic literature identifying primary care-based models of dementia care and their impact on quality of life, (2) a grey literature scan to identify existing provincial and territorial strategies and programs, and (3) discussions with stakeholders in our working group to identify additional resources and literature about dementia care delivery. To ensure that the results of the study would be relevant to stakeholders, particularly PLWD and their care partners, we used a co-design approach, defined as “the co-construction of research through partnerships between researchers and people affected by and/or responsible for action on the issues under study” (Jagosh et al., Reference Jagosh, Macaulay, Pluye, Salsberg, Bush and Henderson2012).

Working Group

In June of 2019, we formed a small working group consisting of one person living with early-onset dementia, four care partners to PLWD, three CFHI staff, and four researchers. The stakeholders were all based in Ontario, except for one, who was in Alberta. Several members are actively involved in national-level organizations and initiatives related to dementia care. The working group held weekly meetings between July 19, 2019 and September 27, 2019 to oversee the study design, data collection, and analysis.

Data Collection

Scoping review

Rationale

We chose to conduct a scoping review instead of a systematic review because of the paucity of literature related to primary care models of dementia care and evidence for their effectiveness in improving quality of life. Unlike a systematic review, a scoping review is guided by a requirement to identify all relevant literature regardless of study design, and often leads to the identification of gaps in knowledge that are suitable for more in-depth pursuits via other methodologies (Gerstain Science Information Centre, 2019; Munn et al., Reference Munn, Peters, Stern, Tufanaru, McArthur and Aromataris2018).

Methodological framework

For our scoping review, we followed the methodological framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley, which outlines five steps to conducting a successful scoping study: (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) modify study selection based on post-hoc familiarity with the topic; (4) chart the data; and (5) collate, summarize, and report the results (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). Step One was completed in consultation with our working group as described, and Step Five is described in the Results. The remaining steps are denoted in the Methods.

Search strategy

In consultation with a librarian at the University of Ottawa, we developed a search strategy (Step Two) to capture the key concepts pertinent to the review (dementia, model, primary care, patients, and quality of life) using subject heading terms and keywords (Appendix A). The search terms for these five concepts were combined to search the MEDLINE®, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library databases. Searches in MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO were run simultaneously in Ovid, whereas the search in CINAHL was run separately through EBSCOhost. We limited our search to publications that were in French or English and published between January 2009 and July 2019. No limitations were put on publication type. Search results were combined in Covidence, a review management software (https://www.covidence.org/), and de-duplicated.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Article inclusion and exclusion criteria were established in consultation with the librarian and working group. Articles were included if they explored a primary care-based intervention, described a model of care, applied to early and middle stages of dementia, presented outcomes related to quality of life, and originated from any of the 11 countries reported on by the Commonwealth Fund’s International Health Policy Survey of Older Adults (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States) (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2017).

Reviewers (trained researchers and CFHI staff members) determined article inclusion by examining the title, abstract, and full text. Two reviewers completed title and abstract screening in both official Canadian languages: I.M. and M.H. for English articles and T.M. and M.M. (a non-author staff member at CFHI) for French articles. Reviewers met to discuss any disagreements (Step Three). Articles deemed relevant in the title and abstract screen moved forward to the full-text review (completed by researchers I.M. and A.M.), as did any articles for which the relevance was unclear based on the information in the abstract. Citations of included articles were screened for further references to include. We did not limit publications by country at this stage.

Data extraction

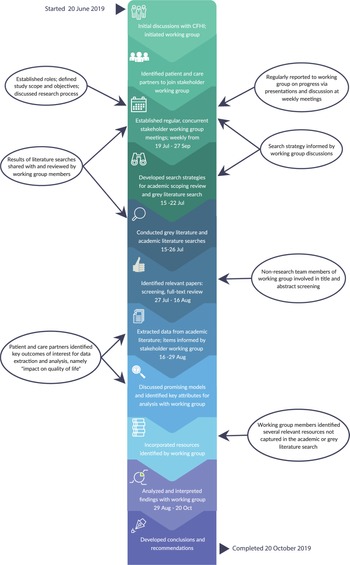

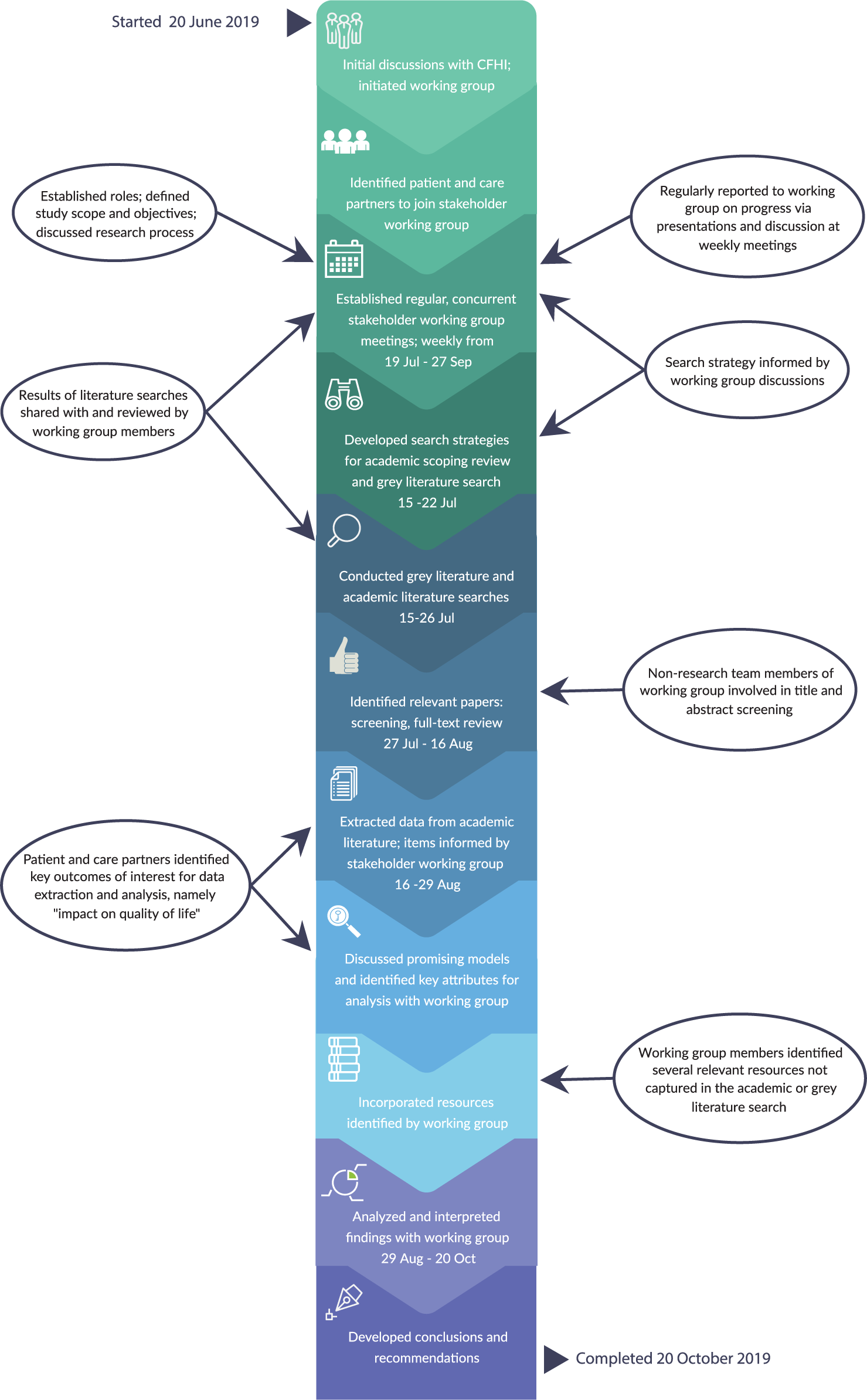

Data extraction took place between July and October 2019 (Figure 1). Three reviewers (researchers I.M., C.S., and M.H.) extracted data from eligible studies using a data extraction spreadsheet created in Microsoft Excel 2016 (Step Four). The following data elements were extracted from each article: country, study type, setting, type of intervention (e.g., screening tool, model of care), brief description, patient population (including sample size, dementia stage, and diagnostic techniques), intervention target group (e.g., patients, providers, and care partners), intervention delivery agent, key outcomes, and notes/observations.

Figure 1 Timeline of the environmental scan to identify models, strategies, and resources for dementia care in Canada

Grey literature search

We conducted a grey literature search between July 19 and 22, 2019 to identify existing dementia strategies and programs in Canadian provinces and territories. The initial search was based on Appendix B of the National Dementia Strategy, as it provided a general overview of provincial and territorial dementia-related initiatives at the time (Government of Canada, 2019). We identified provinces and territories that had released dementia strategies or frameworks. We also conducted a Google search to identify additional specific programs existing in the provinces and territories, using the following search structure: “[province/territory name] dementia program”.

Stakeholder identification of resources and literature

Concurrent with the scoping review and grey literature scan, working group members identified additional resources relevant to dementia care delivery and academic literature describing models of care. These were shared among group members via e-mail and discussed at working group meetings. All were considered within the context of the scan and included if relevant.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted with members of the stakeholder working group using a thematic analysis with constant comparison approach. Results were iteratively presented to the group and discussions were facilitated to identify key outcomes of interest, interpret the findings, and identify gaps. The perspectives of PLWD and their care partners were explicitly sought during and between meetings.

Scoping review

Characteristics of identified articles, descriptions of the models of care, and the reported outcomes were summarized and tabulated. Reported findings were categorized and are summarized in the main text. Through qualitative synthesis and categorization, we identified key and common components of each model. Descriptions are provided.

Grey literature search

Provincial and territorial strategies and programs identified in the grey literature were collated into an inventory and visualized geographically. Evaluation of the impact, effectiveness, or reach of these was outside the scope of this scan.

Stakeholder identified resources and literature

Resources and literature identified by stakeholders and not captured in the academic scoping review or grey literature search were collated into an inventory. No evaluation of the impact, effectiveness, or reach of these resources or models of care was completed as part of this environmental scan.

Results

Objective 1: Identify Published Primary Care Models of Dementia Care

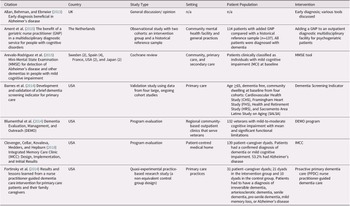

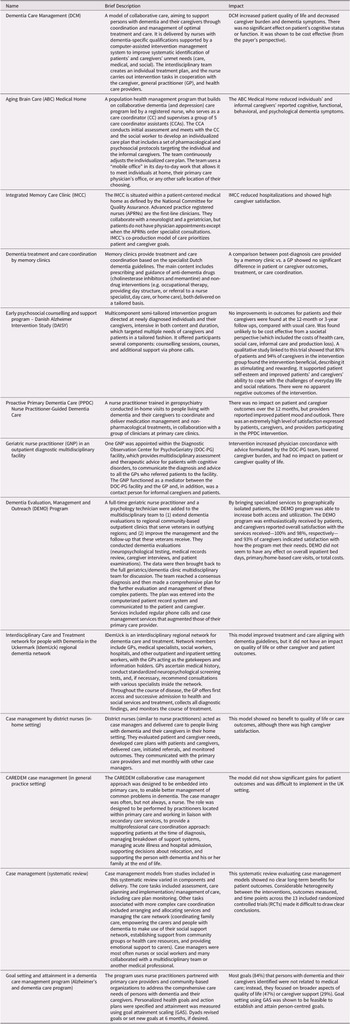

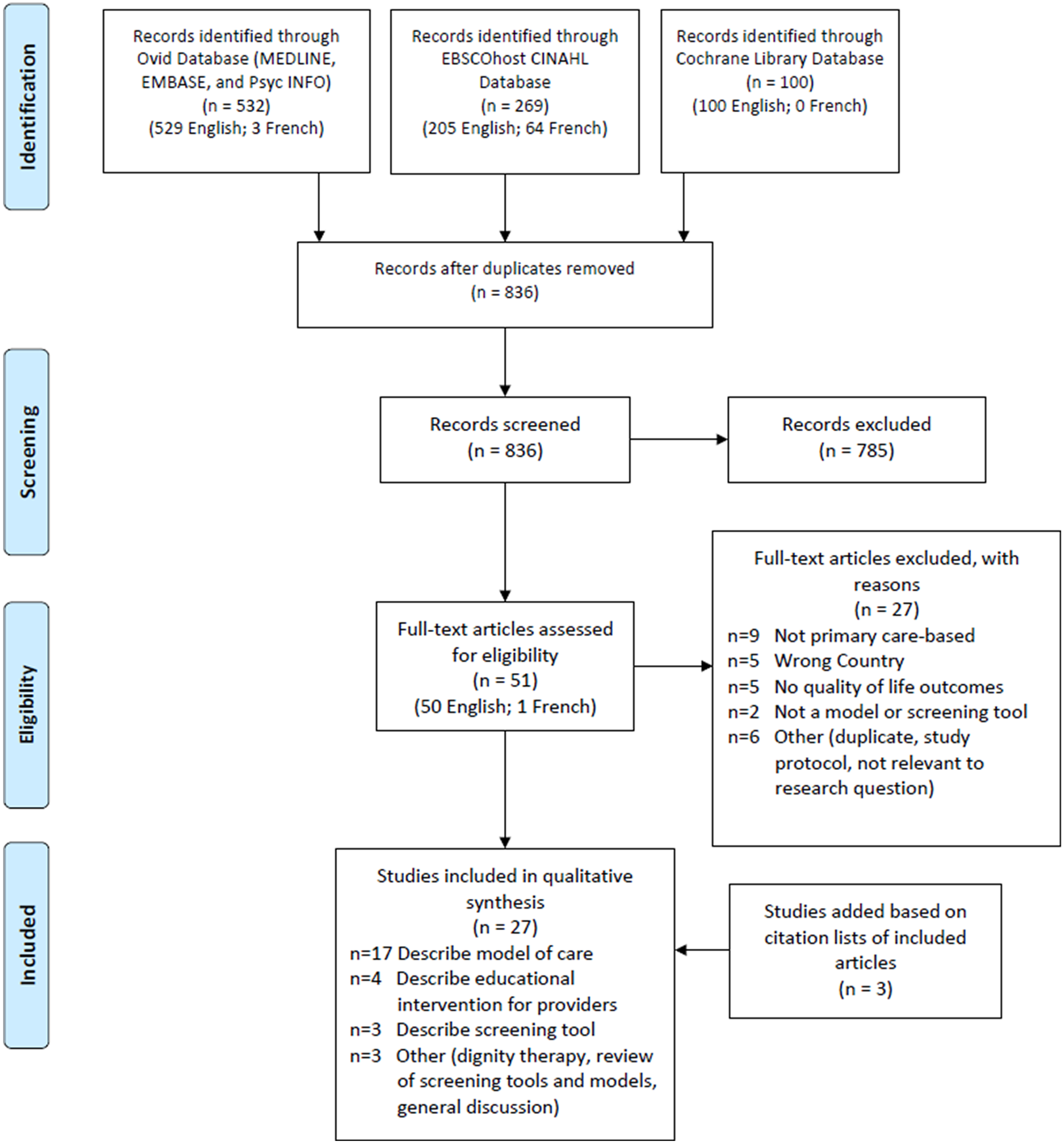

The scoping review retrieved a total of 901 articles, of which 27 met inclusion criteria (Figure 2). Among the 27 studies, 17 described 13 different primary care-based models of dementia care for people in the early and middle stages of dementia (Ament et al., Reference Ament, Wolfs, Kempen, Ambergen, Verhey and De Vugt2015; Blumenthal et al., Reference Blumenthal, Cai, May, Brandt, Gernat and Mordecai2014; Clevenger, Cellar, Kovaleva, Medders, & Hepburn, Reference Clevenger, Cellar, Kovaleva, Medders and Hepburn2018; Fortinsky et al., Reference Fortinsky, Delaney, Harel, Pasquale, Schjavland and Lynch2014; Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Waugh, Poole, Bamford, Brittain and Chew-Graham2014; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, van Hout, Nijpels, Rijmen, Droes and Pot2011; Jennings, Ramirez, Hays, Wenger, & Reuben, Reference Jennings, Ramirez, Hays, Wenger and Reuben2018; Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Meinke-Franze, Hein, Fendrich, Heymann and Thyrian2014; LaMantia et al., Reference LaMantia, Alder, Callahan, Gao, French and Austrom2015; Meeuwsen et al., Reference Meeuwsen, Melis, Van Der Aa, Golüke-Willemse, De Leest and Van Raak2012; Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019; Phung et al., Reference Phung, Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Keiding and Rishoj2013; Reilly et al., Reference Reilly, Miranda-Castillo, Malouf, Hoe, Toot and Challis2015; Sogaard et al., Reference Sogaard, Sorensen, Waldorff, Eckermann, Buss and Phung2014; Sørensen, Waldorff, & Waldemar, Reference Sørensen, Waldorff and Waldemar2008; Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017; Waldorff et al., Reference Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Rasmussen, Keiding and Rishøj2012), four described educational interventions for providers (Menn et al., Reference Menn, Holle, Kunz, Donath, Lauterberg and Leidl2012; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Drašíkovic, Lucassen, Vernooij-Dassen, van Achterberg and Rikkert2011; Pond et al., Reference Pond, Mate, Stocks, Gunn, Disler and Magin2018; van den Dungen et al., Reference van den Dungen, Moll van Charante, can de Ven, van Marwijk, van der Horst and van Hout2016), three presented screening tools (Arevalo-Rodriguez et al., Reference Arevalo-Rodriguez, Smailagic, Figuls, Ciapponi, Sanchez-Perez and Giannakou2015; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Beiser, Lee, Langa, Koyama and Preis2014; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Koekkoek, van Charante, Kappelle, Biessels and Rutten2017), one discussed dignity therapy (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Lawton, McCaw, Law, Murray and Gibb2016), one reviewed various screening tools and models (Geldmacher & Kerwin, Reference Geldmacher and Kerwin2013), and one presented a general discussion on the benefits of early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (Allan et al., Reference Allan, Behrman and Ebmeier2013). Details of included studies are available in Table 1, while descriptions of the models of care identified in the studies can be found in Table 2.

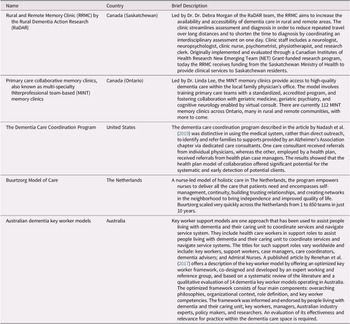

Table 1: Characteristics of studies included in scoping review

Table 2: Models of dementia care identified through the scoping review

Figure 2. Flow diagram demonstrating inclusion and exclusion of articles during scoping review

Of the 17 articles that described primary care-based models of dementia care for people with early- and middle-stage dementia, 8 were randomized controlled trials, 2 were reviews, and 7 used other research designs. Most articles featured multi-component, collaborative models of care. These models often utilized other service providers (e.g., specialized nurses or other allied health professionals) to coordinate and deliver medical and non-medical care to PLWD and care partners. Several common core components characterized the models: (1) a team-based approach involving collaboration among primary care physicians, specialists, care/case managers, and care partners; (2) a care/case manager responsible for care coordination and integration across a broader provider network and community resources; (3) development of an individualized care/treatment plan that is regularly monitored and adaptable to changing needs; (4) a stepped-care approach, with targeted specialty consultation available for more complex cases as needed, and (5) consideration of the care partner’s needs along with those of the PLWD.

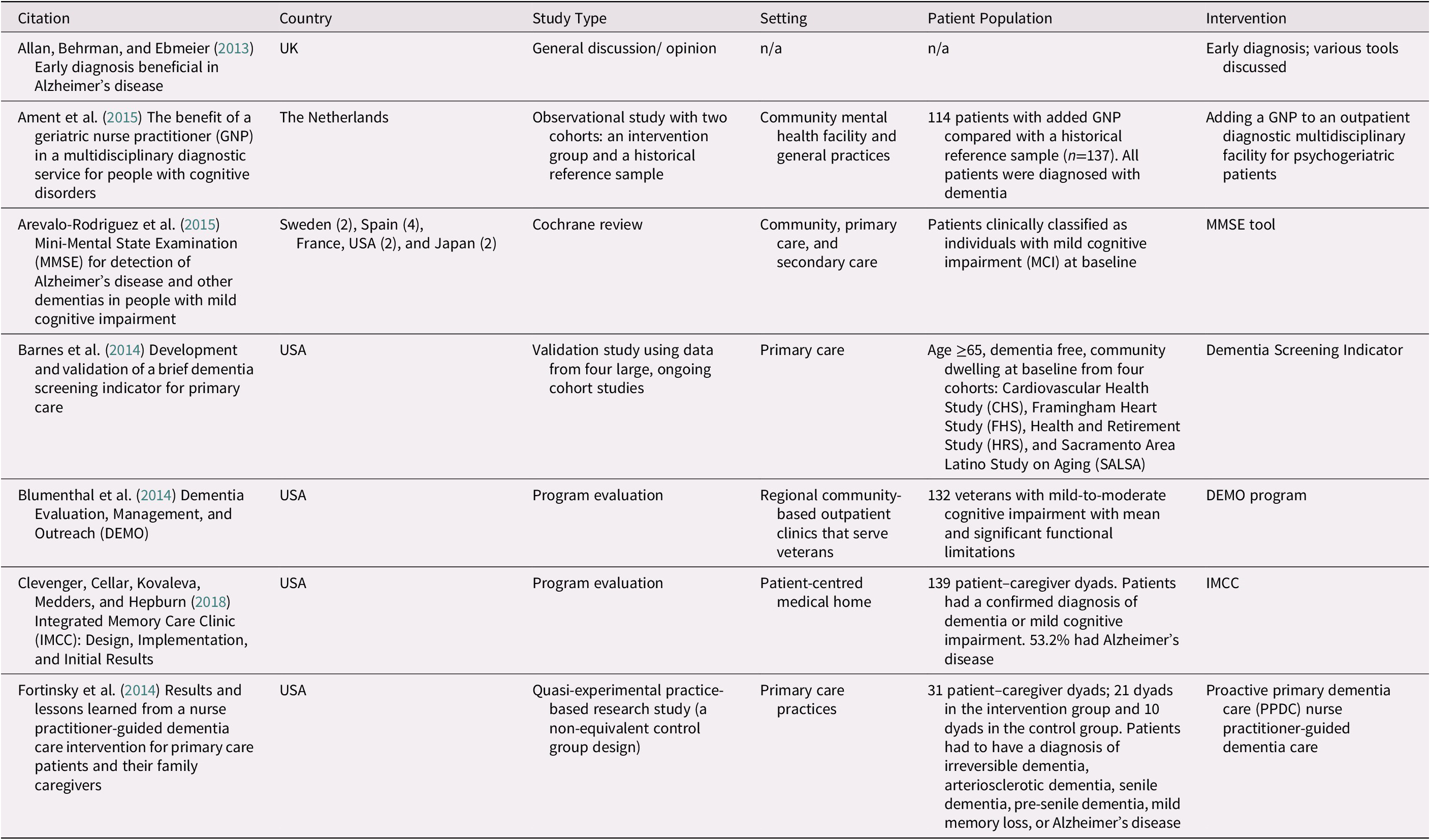

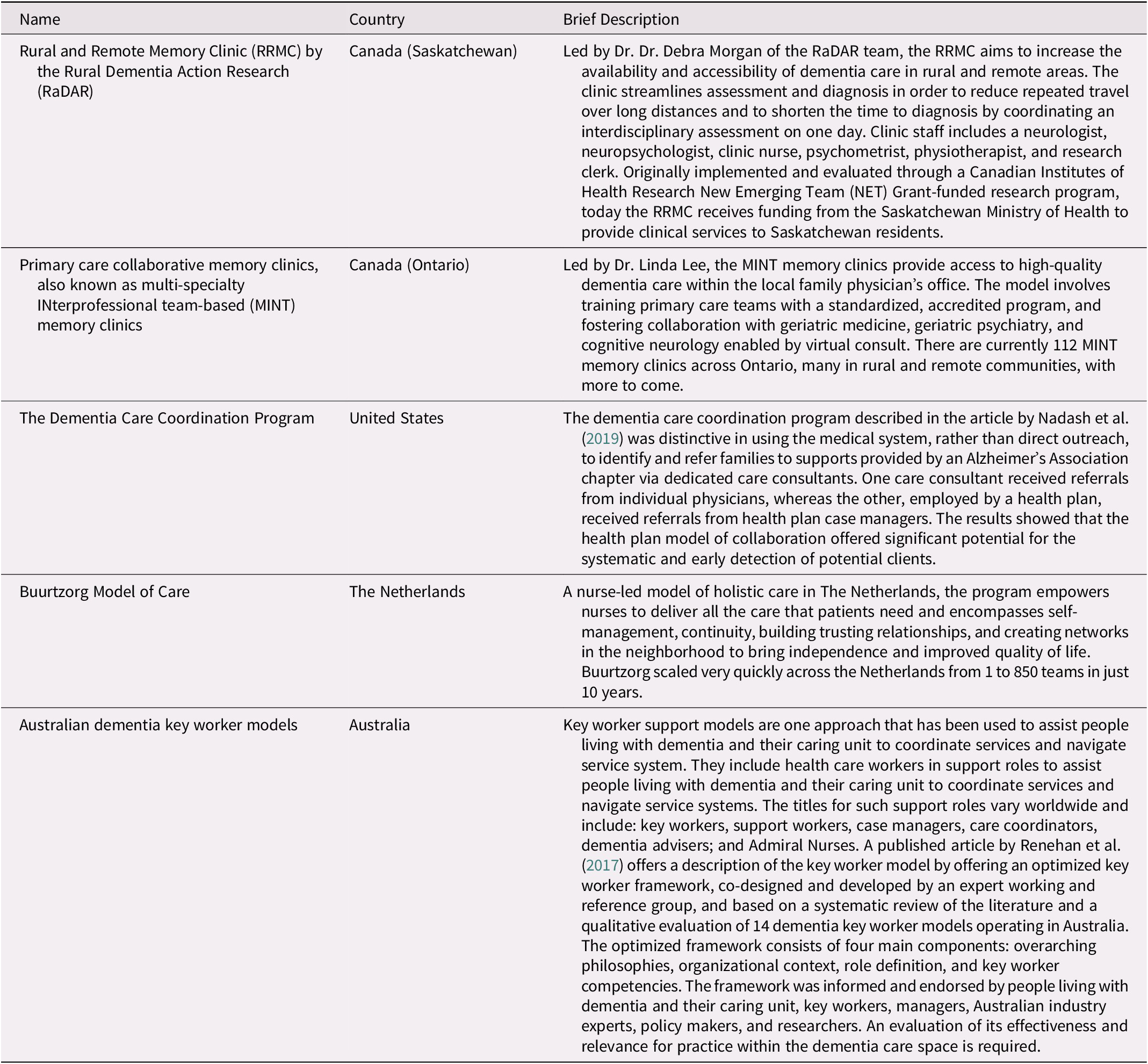

In addition to the models of care identified through the scoping review, the PLWD, their care partners, and CFHI staff members in the working group identified five distinct models of dementia care published in the literature, two based in Canada (Health Innovations Group, 2019; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Hillier, Stolee, Heckman, Gagnon and McAiney2010, Reference Lee, Hillier, McKinnon Wilson, Gregg, Fathi and Sturdy Smith2018; Lee, Hillier, Locklin, Lumley-Leger, & Molnar, Reference Lee, Hillier, Locklin, Lumley-Leger and Molnar2019; Rural Dementia Action Research, 2019) and three that were international (Buurtzorg, 2019; Nadash, Silverstein, & Porell, Reference Nadash, Silverstein and Porell2019; Renehan, Goeman, & Koch, Reference Renehan, Goeman and Koch2017) (Table 3). All models featured elements of collaborative care, and included memory clinics and variations of care/case management. None of the models included any evaluation of impact on quality of life. However, the Multispecialty INterprofessional Team-based (MINT) Memory Clinics led in Ontario, which address the issue of access to dementia care in primary care by coordinating and streamlining an interdisciplinary assessment, have recently undergone evaluation and shown positive outcomes. These include high levels of patient and care partner satisfaction with the clinics and strong satisfaction with the training and support provided by physicians and allied health professionals (Health Innovations Group, 2019). Challenges identified included sustainability at both a stewardship and an operational level, in addition to different resource models and levels of integration between primary care and specialist physician care across the province (Health Innovations Group, 2019).

Table 3: Models of dementia care identified by working group

The working group also identified three other pieces of literature relevant to this summary of dementia care models: a strategic framework for a regional model of dementia care (Champlain Dementia Network, 2013), a systematic review of case manager collaboration models (Khanassov & Vedel, Reference Khanassov and Vedel2016), and a review of caregiver- and patient-directed interventions (Health Quality Ontario, 2008).

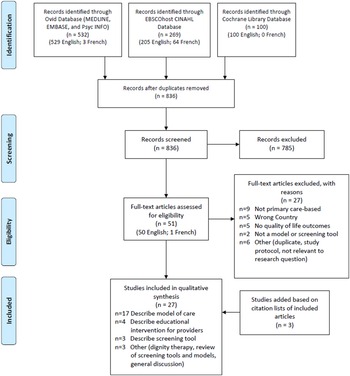

Objective 2: Identify Strategies and Resources Supporting Dementia Care

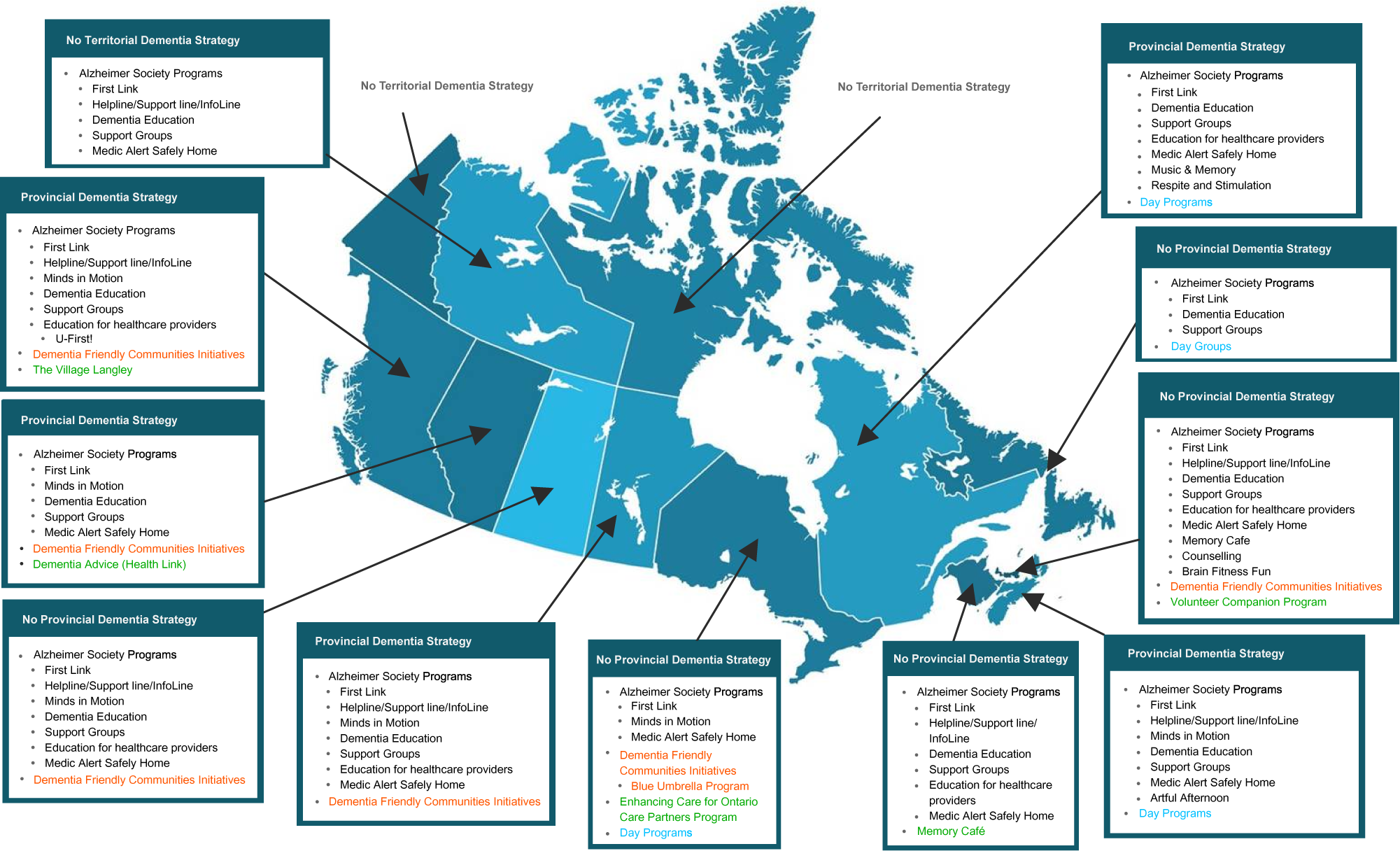

Through our grey literature search, we identified only five provinces that had released a dementia strategy: British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec, and Nova Scotia (Alberta Government, 2017; Bergman, Reference Bergman2009; British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2016; Manitoba, 2014; Province of Nova Scotia, 2015) (Figure 3). However, programs supporting PLWD existed in every province and territory except the Yukon and Nunavut. The Alzheimer Society operated in all these jurisdictions (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2019a), where it often provided such programs as First Link® (a referral program for people recently diagnosed with dementia) (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2019b) and Minds in Motion® (an exercise regimen supporting physical and mental stimulation) (Alzheimer Society of B.C., 2019), as well as a helpline and general dementia education services. Programs unique to certain provinces included Music&Memory® in Quebec (Société Alzheimer de l’Estrie, 2019), Memory Café in New Brunswick (Alzheimer Society of New Brunswick, 2019), Brain Fitness Fun in Prince Edward Island (Alzheimer Society of PEI, 2019), and the Village Langley in British Columbia (Village Langley, 2019).

Figure 3. Map of provincial and territorial strategies and programs for people living with dementia in Canada

In addition to the strategies and programs uncovered by the grey literature search, the working group identified 11 additional resources supporting dementia care in Canada. Through iterative discussion with our working group, we divided these resources into three categories: research networks, programs, and recommendations.

Research networks

Participants identified five research networks focusing on issues relevant to dementia (Table 4). Four of the identified networks operated in Canada (two of which were multinational) (Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging, 2019; International Indigenous Dementia Research Network, 2019; Island Health, 2019; Rural Dementia Action Research, 2019), whereas the fifth was situated in Australia (Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, 2019).

Table 4: Research networks identified by the working group

Programs for PLWD and their care partners

Participants identified three programs based in Canada for PLWD and their care partners, in addition to those found through the grey literature search (Alberta Health Services, 2011; Living the Dementia Journey, 2019; YouQuest, 2019). These included Memory P.L.U.S. (Practice, Laughter, Useful Strategies), a community-based education program that supports people with mild dementia and their care partners; the YouQuest therapeutic recreation program; and Living the Dementia Journey, an evidence-informed training program for those who support PLWD.

Recommendations related to dementia care

Participants identified three organizations that provided specific recommendations pertaining to dementia care. The Canadian Nurses Association published a report containing five proposals in support of improved dementia care, which included developing a national dementia strategy, shifting PWLD to community care, and supporting dementia-based education for nurses and other health care professionals (Canadian Nurses Association, 2016). Health Quality Ontario issued a quality standard for treatment of PLWD in the community, including guidelines for primary care, specialist care, hospital outpatient services, home care, and community support services (Health Quality Ontario, 2019). It also provided guidance on support for care partners of PLWD, and proposed measures of success at a provincial and local level. The American Academy of Neurology issued a press release encouraging annual cognitive screenings for people 65 years of age and older (American Academy of Neurology, 2019).

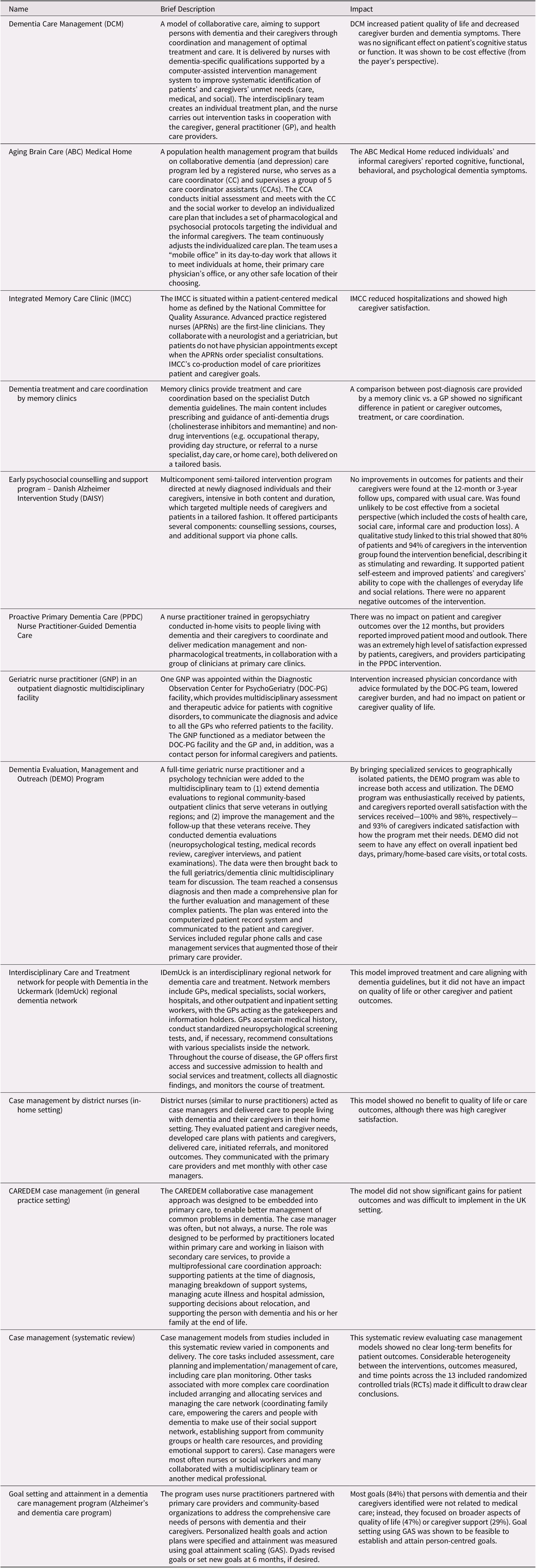

Objective 3: Examine Effectiveness of Models in Improving Quality of Life

The studies included in the scoping review used a variety of outcome measures and indicators to evaluate the models of care. However, only one model reported a positive impact on quality of life for PLWD (Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019; Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017). This study assessed the Dementia Care Management (DCM) model, a computer-supported, collaborative care model-based intervention, characterized by a high intensity of care management and level of integration across health care and social services. Although designed to target cost effectiveness, the study by Michalowsky et al. used the 12-item Short-Form Health Questionnaire (SF-12) to assess health-related quality of life and calculate patients’ Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). They found an increase in QALYs over the study period (Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019). A randomized clinical trial of DCM also found a significant increase in quality of life among PLWD who did not live alone, although this did not extend to the overall sample (Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017). In this study, the Quality of Life in Alzheimer Disease instrument (QOL-AD) (Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, Reference Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry and Teri2002) was used.

Another model that was thought to be promising was evaluated in the Danish Alzheimer Intervention Study (DAISY). The DAISY intervention is a psychosocial counselling and support program directed at newly diagnosed individuals and care partners, and it was the subject of a randomized controlled trial (Waldorff et al., Reference Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Rasmussen, Keiding and Rishøj2012). Although a qualitative study showed benefits for PLWD and their care partners (Sørensen et al., Reference Sørensen, Waldorff and Waldemar2008), it resulted in no statistically significant improvements in outcomes for PLWD and their care partners, including quality of life measurements, after 12 months (Waldorff et al., Reference Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Rasmussen, Keiding and Rishøj2012) or at the 3-year follow up (Phung et al., Reference Phung, Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Keiding and Rishoj2013), compared with usual care.

Other outcomes that were reported about the models of care were reduced care partner burden (Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019; Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017), increased patient/care partner satisfaction (Blumenthal et al., Reference Blumenthal, Cai, May, Brandt, Gernat and Mordecai2014; Clevenger et al., Reference Clevenger, Cellar, Kovaleva, Medders and Hepburn2018; Fortinsky et al., Reference Fortinsky, Delaney, Harel, Pasquale, Schjavland and Lynch2014; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, van Hout, Nijpels, Rijmen, Droes and Pot2011; Sørensen et al., Reference Sørensen, Waldorff and Waldemar2008), increased provider satisfaction (Fortinsky et al., Reference Fortinsky, Delaney, Harel, Pasquale, Schjavland and Lynch2014), improved compliance to/alignment with dementia care recommendations/guidelines (Ament et al., Reference Ament, Wolfs, Kempen, Ambergen, Verhey and De Vugt2015; Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Meinke-Franze, Hein, Fendrich, Heymann and Thyrian2014), reduction in hospitalizations (Clevenger et al., Reference Clevenger, Cellar, Kovaleva, Medders and Hepburn2018), decreased dementia symptoms (LaMantia et al., Reference LaMantia, Alder, Callahan, Gao, French and Austrom2015; Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019; Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017), and cost effectiveness (Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019).

Discussion

Our environmental scan identified a total of 18 models supporting dementia in primary care—13 through the scoping review and 5 through working group discussions—alongside strategies and resources supporting the implementation of these models. Services supporting PLWD exist in nearly all provinces and territories, but published and adopted provincial strategies for dementia care were only identified for five provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec, and Nova Scotia).

Our scan identified several positive outcomes associated with primary care models for dementia, including improvements in PLWD, care partner and provider satisfaction, reduced hospitalizations, and improved compliance aligning with dementia care recommendations/ guidelines. However, out of all the models reviewed, only one demonstrated an ability to improve quality of life for PLWD: the DCM model (Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019; Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017). DCM is a highly flexible model that used a computer-based intervention management system to connect PLWD with a multi-professional team to support their care. Care is often delivered at home by nurses specializing in dementia care (Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017). A randomized clinical trial of the model demonstrated a significant increase in quality of life among PLWD not living alone, in addition to a decrease in behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (Thyrian et al., Reference Thyrian, Hertel, Wucherer, Eichler, Michalowsky and Dreier-Wolfgramm2017), while a subsequent study examining cost effectiveness demonstrated an increase in QALYs among individuals receiving DCM-based treatment (Michalowsky et al., Reference Michalowsky, Xie, Eichler, Hertel, Kaczynski and Kilimann2019). It should be noted that there are differences in the applicability and validity of the tools used to measure quality of life in this patient population, the SF-12 and QOL-AD (Geschke, Fellgiebel, Laux, Schermuly, & Scheurich, Reference Geschke, Fellgiebel, Laux, Schermuly and Scheurich2013). Despite this, DCM demonstrated substantial promise and should receive greater examination.

Comparison of the primary care models identified was challenging, because of the heterogeneity of the interventions, outcome measures, and time points examined, as previously reported in the literature (Backhouse et al., Reference Backhouse, Ukoumunne, Richards, McCabe, Watkins and Dickens2017; Reilly et al., Reference Reilly, Miranda-Castillo, Malouf, Hoe, Toot and Challis2015). However, in our review, several key components emerged that were consistent across programs. These precepts offer a strong template for effective service delivery, and bear keeping in mind for those looking to create or implement models of dementia care in primary care settings. First, models adopted a team-based approach, with clear guidelines to inform how primary care providers can offer dementia care in collaboration with other providers, family members, and the PLWD themselves. In every case but one, this was accomplished by retaining a central role for persons’ existing primary care providers in the diagnosis and management of dementia (Clevenger et al., Reference Clevenger, Cellar, Kovaleva, Medders and Hepburn2018). Second, models enlisted case managers responsible for coordination of medical, allied health, and community services. Third, models supported the development of individual treatment plans that were continually monitored and updated as necessary to reflect the PLWD’s changing needs. Fourth, models used a stepped-care approach, providing links to specialty care and community resources. Lastly, models emphasized the importance of incorporating the care partner’s needs along with those of the PLWD. It is worth further noting that these needs extend beyond medical services. An important finding of Jennings et al. (Reference Jennings, Ramirez, Hays, Wenger and Reuben2018) was that most needs and corresponding goals (84%) that PLWD and care partners identified were not related to medical care, but instead focused on broader aspects of quality of life or care partner support. Likewise, our synthesis of existing literature revealed that there is a lack of evaluation and evidence regarding the impact of primary care-based dementia models on quality of life of PLWD and care partners, and that there is a need to improve the delivery of dementia care and support in primary care settings by focusing on quality of life as an essential outcome.

Our grey literature search identified publicly available dementia-related strategies in fewer than half of Canadian provinces and territories. This finding highlights significant equity issues regarding access to services for people affected by dementia. Provinces and territories that have not adopted guidelines should consider doing so, to ensure that PLWD and care partners in these jurisdictions are not overlooked. The strategic themes identified by Edick, Holland, Ashbourne, Elliott, and Stolee (Reference Edick, Holland, Ashbourne, Elliott and Stolee2017) from international literature provide a starting framework for these jurisdictions. Encouragingly, all jurisdictions except for two territories had some manner of program to support dementia care. Further, our scan included discussions with members of our own working group who had lived experience with dementia, in order to identify additional resources that the search may have missed. Through these discussions, we identified five models of dementia care and 11 resources. Some of these models featured elements of collaborative care similar to those identified in the scoping review, such as care/case management (Nadash et al., Reference Nadash, Silverstein and Porell2019; Renehan et al., Reference Renehan, Goeman and Koch2017). Several resources featured interesting community-based programs identified for PLWD and/or care partners (e.g., Memory P.L.U.S. [Alberta], YouQuest therapeutic recreation model [Alberta], and Living the Dementia Journey [Ontario]). However, our study’s scope did not include evaluation of these programs, necessitating further exploration of their impact on outcomes for PLWD.

Our co-design approach influenced the study’s design, results, analysis, and interpretation. There is evidence that co-design has a favorable impact on health research by improving quality, acceptability, rigor, and relevance; building capacity; creating sustainability; and generating new insights and activities (Jagosh et al., Reference Jagosh, Macaulay, Pluye, Salsberg, Bush and Henderson2012). In our own experience, our co-design approach was instrumental in shaping the study to best match PLWD and care partner perspectives and priorities. For example, our partners with lived experience emphasized that “impact on quality of life” was the outcome of most importance to them. This input guided our search strategy, data extraction, and analysis. These team members also described the gaps in care and supports that PLWD and their care partners experience, which informed interpretation. Given our experience and the supporting literature (Bergman, Reference Bergman2019; Jagosh et al., Reference Jagosh, Macaulay, Pluye, Salsberg, Bush and Henderson2012), we recommend maintaining a co-design approach throughout program/service development and implementation, to ensure that such programs and services meet the needs of all stakeholders, particularly PLWD and their care partners. Key impact outcomes, such as quality of life, should be defined at program onset.

This environmental scan was conducted with a rigorous methodology and transparent process to present an accurate picture of existing dementia care models within primary care. However, several limitations must be noted. During our scoping review, we limited our search to articles discussing impact on quality of life; we sought literature from only 11 Commonwealth countries; and, although French language articles were included, our search was limited to English databases. Finally, our grey literature search was not exhaustive, as we conducted a simple keyword search in the Google search engine only. Therefore, we must acknowledge that it is likely that we did not capture all existing models and resources. Review of literature from other countries, including non-Commonwealth countries, may identify other promising models of care and assessments of impact on quality of life for PLWD and their care partners. The models of care identified by the working group and the identified provincial and territorial strategies and programs were not evaluated for impact on quality of life or other outcomes. A more in-depth investigation into the reach, quality, equity, accessibility, and effectiveness of these models, strategies, and programs was beyond the scope of this review but is recognized as the necessary next step. In some provinces, such as Quebec, evaluation of such outcomes is underway; implementation of the Quebec Alzheimer Plan shows promise, with positive impact on detection and management of neurocognitive disorders (Godard-Sebillotte, Vedel, & Bergman, Reference Godard-Sebillotte, Vedel and Bergman2016; Vedel, Sourial, Arsenault-Lapierre, Godard-Sebillotte, & Bergman, Reference Vedel, Sourial, Arsenault-Lapierre, Godard-Sebillotte and Bergman2019). A more fulsome analysis of the grey literature could also be done to identify unpublished or emerging innovations in dementia care. Additionally, follow-up interviews with the authors of the articles identified during the scoping review are recommended to assess the sustainability of the models/programs and other information pertinent to national spread.

Conclusion

Many models supporting primary care-based dementia care exist in the literature. Resources supporting PLWD and their care partners are available across most of Canada, although overarching strategies were found to be in place in only five provinces, suggesting a need for greater coordination. The models identified in our study are supported by evidence of positive outcomes, although evidence of their impact on quality of life for PLWD and their care partners was limited to a single study. Although these findings are encouraging, further research is needed to identify primary care models for dementia care that demonstrably improve quality of life. Given that primary care practices are complex adaptive systems, no single model fits the context of every practice. The evidence recommends that the core components identified be adapted to local needs, complexities, and resource constraints.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Justin Joschko for his assistance in editing the manuscript and preparing it for publication.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000635.