The Lithuanian language, together with Latvian, belongs to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family and to the group of Eastern Baltic languages. The two surviving Baltic languages have many common features of phonemic inventories: opposition of long and short vowels, an abundance of diphthongs, a system of pitch accent. They have also developed substantial differences, e.g. Latvian has fixed stress and a set of palatal consonants, while Lithuanian has free (distinctive) stress and a phonological opposition between palatalized and non-palatalized consonants (Poliakovas Reference Poliakovas2008: 9, 42; Dini Reference Dini2019: 577; Jaroslavienė et al. Reference Jaroslavienė, Grigorjevs, Urbanavičienė and Indričāne2019: 263; Gelumbeckaitė & Pakerys Reference Gelumbeckaitė and Pakerys2020). In contrast to other Indo-European languages, the Baltic languages have lost j between a consonant and a front vowel, and have preserved m, rather than assimilated it, before the dental consonants d, t, which has not become n Footnote 1 (Endzelynas Reference Endzelynas1957: 8). Lithuanian has preserved the manner of articulation of Indo-European plosive consonants (Bonfante Reference Bonfante2008: 40). As a result of the continuous and long-lasting contact of Baltic with Slavic languages, these language groups also share common linguistic features (discussed later).

Today, Lithuanian is spoken by approximately three million people living for the most part in the Republic of Lithuania, located in the central part of Europe on the south-eastern coast of the Baltic Sea (see Figure 1); Lithuanian is also spoken by national minorities in Latvia, Belarus and Poland, and by respective immigrant communities in the USA, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain, South America and elsewhere. Although the number of Lithuanian speakers is not large, and their geographical distribution relatively limited, different historical, social and other factors (for example, Baltic tribal substrate, the late formation of a standard language after Lithuania regained independence in 1918, the boundaries of the old administrative units, the sedentariness of the rural population, etc., see Zinkevičius Reference Zinkevičius2006) have shaped the heterogeneity of the Lithuanian language, which is characterized by great regional variation. One of the variants – Western Aukštaitian of Kaunas – served as a basis for the Standard Lithuanian language that has the status of the official language.

Figure 1 (Colour online) Lithuania and bordering countries (Map of Lithuania 2020).

Note: More about Lithuanian regional variation, population, language norms and other related questions can be found in e.g. Mikulėnienė et al. Reference Mikulėnienė, Violeta Meiliūnaitė, Rima Bakšienė, Jurgita Jaroslavienė, Asta Leskauskaitė, Nadežda Morozova, Lilija Plygavka, Regina Rinkauskienė, Švambarytė-Valužienė, Urbanavičienė and Vaišnienė2014, Reference Mikulėnienė, Agnė Čepaitienė, Laura Geržotaitė, Leskauskaitė, Meiliūnaitė and Vyniautaitė2019; Aliūkaitė et al. Reference Aliūkaitė, Mikulėnienė, Čepaitienė and Geržotaitė2017; Miliūnaitė Reference Miliūnaitė2018, Reference Miliūnaitė2019; Lithuania 2020.

This Illustration is based on a recording made by a female 48-year-old Lithuanian native speaker whose pronunciation is representative of Standard Lithuanian. She works as a researcher and speaks the Western Aukštaitian subdialect of Kaunas, which is closest to Standard Lithuanian. The speaker grew up in a monolingual environment and studied additional foreign languages (Latvian, Russian, English and German) at school and university.

The material for this paper was recorded with the help of a Tascam DR-100MK II digital high-resolution audio recorder and an AKG C 520 head-set microphone. The signal was sampled at a rate of 44.1 kHz (16-bit quantisation). The analysis of the sounds and prosodic features was performed using the sound processing and analysis software program Praat (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2018). The data obtained were further processed using MS Excel and SPSS (IBM Corporation).

The Illustration contains examples (the transcribed words and the text of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’) presented in a simplified transcription variant: the quantitative and more important qualitative variants of phonemes are marked; however, more subtle qualitative variants that occurred due to such general laws of coarticulation as nasalization and labialization are unmarked.

Consonants

The consonant system of the Lithuanian language consists of 45 consonant phonemes (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 73; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 39; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 224; Stundžia Reference Stundžia2014b: 10). Six phonemes (/f fʲ x xʲ ɣ ɣʲ/) are peripheral: they occur only in loanwords or onomatopoeic words (see Consonant Table below).

Palatalized and non-palatalized consonants

The Lithuanian language has secondary palatalization. The existence of palatalized and non-palatalized consonants is one of the main phonological features of the Lithuanian consonant system (as in Russian, for example). This feature distinguishes Lithuanian from another Baltic language, Latvian, which has palatal and non-palatal consonants (Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 327). Secondary palatalization is characterized by the elevation of the middle part of the tongue towards the hard palate, and constitutes an additional articulatory feature of the palatalized consonants. The only palatal consonant is /j/, e.g. jáunas [1ˈjæˑʊnʌs] ‘young’, juõkas [2ˈju̟ɔkʌs] ‘laughter’. Secondary palatalization in Lithuanian is regular, unlike in Slavic languages, for example (see Yanushevskaya & Bunčić Reference Yanushevskaya and Bunčić2015: 222; Bird & Litvin Reference Bird and Litvin2021: 452–454): in Lithuanian each consonant has both palatalized and non-palatalized counterparts.

Compared to the corresponding palatalized sounds, the articulation of the non-palatalized consonants /l ʃ ₒ/ is characterized by velarization (a secondary articulation involving movement of the back of the tongue towards the velum), and Lithuanian non-palatalized postalveolar /ʃ ₒ/ are labialized.Footnote 3

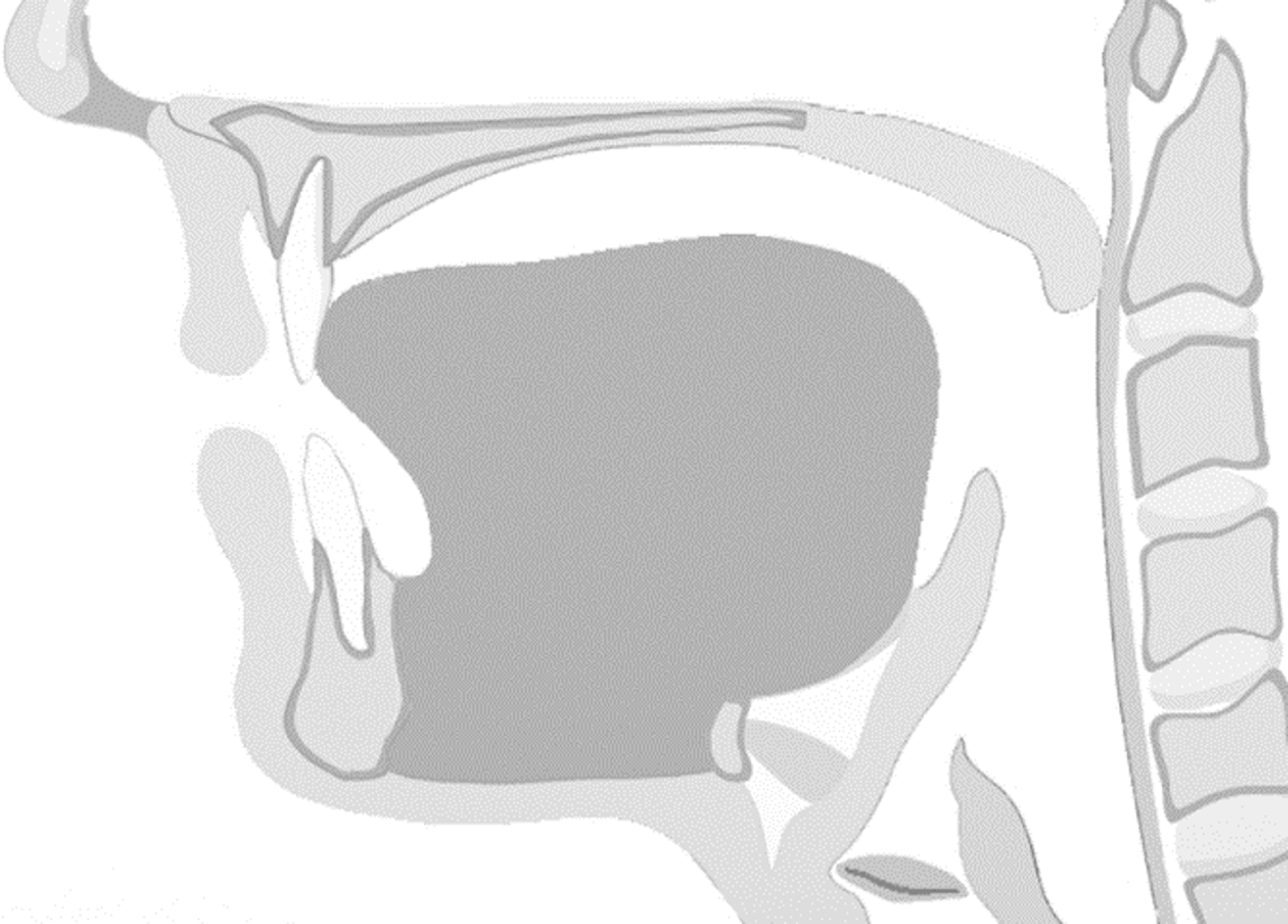

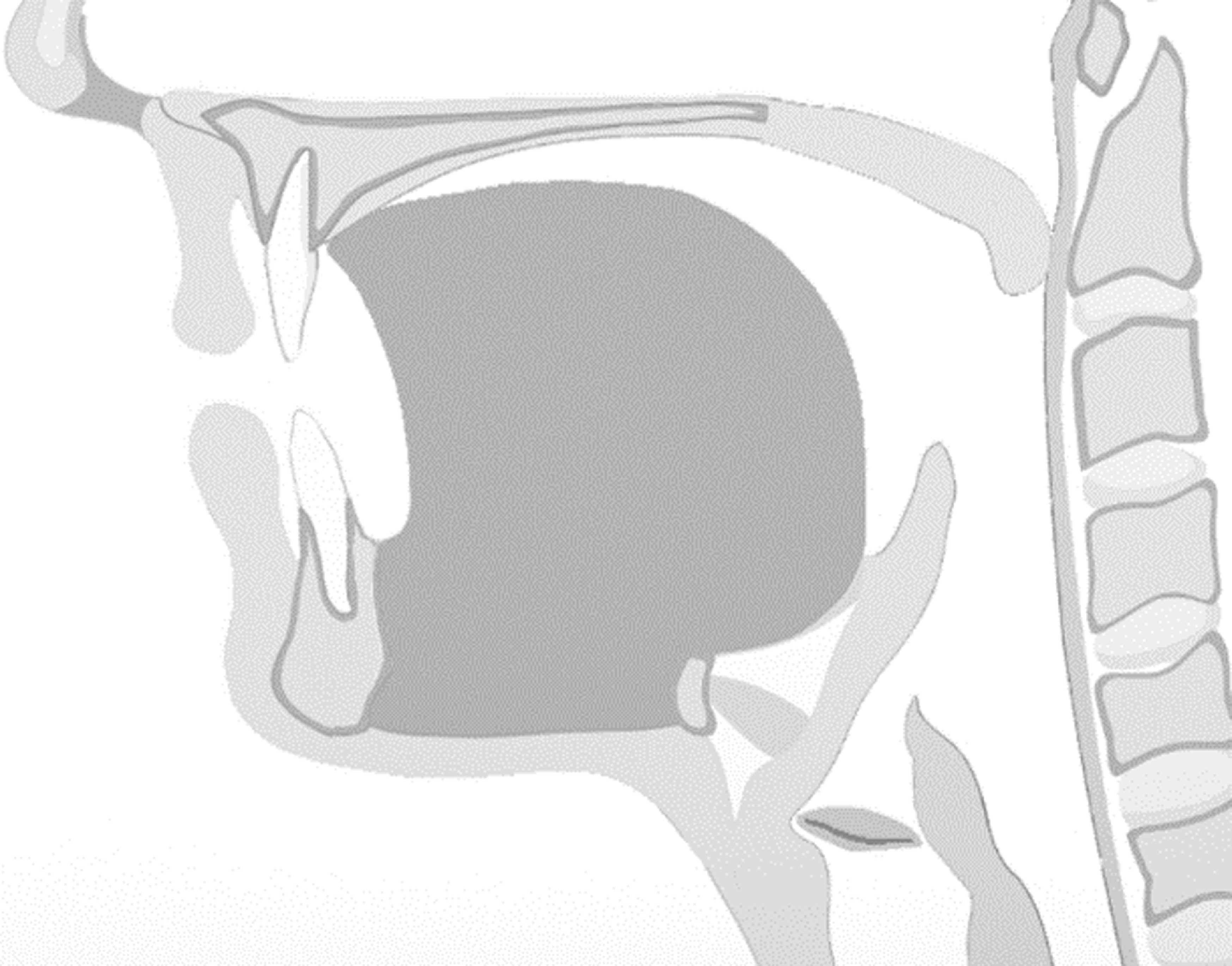

Figure 2 Speech articulators activity for pronouncing non-palatalized /l/.

Figure 3 Speech articulators activity for pronouncing palatalized /lʲ/.

Both palatalized and non-palatalized consonants occur before back vowels, e.g. sùsti [ˈsʊsʲtʲɪ] ‘grow scabby, wither’ : siùsti [ˈsʲʊ̟sʲtʲɪ]Footnote 4 ‘be in a bad temper; be angry’, gabùs [ɡʌˈbʊs] ‘talented’ : gabiùs [ɡʌˈbʲʊ̟s] ‘talented ones’ (acc.pl.m), trapùs [trʌˈpʊs] ‘fragile’ : trapiùs [trʌˈpʲʊ̟s] ‘fragile ones’ (acc.pl.m), galù [ɡʌˈlʊ] ‘end’ (instr.sg) : galiù [ɡʌˈlʲʊ̟] ‘(I) can’ (so called non-motivated palatalizationFootnote 5). Palatalized consonants are also used before front vowels (e.g. tylė́ti [tʲiː1ˈlʲeːtʲɪ] ‘be silent’, nẽšėme [2ˈnʲæːʃʲeːmʲɛ] ‘(we) carried’, kíetis [1ˈkʲiɛtʲɪs] ‘sagebrush’) and before other palatalized consonants or the palatal /j/ (so called motivated palatalization), e.g. baltì [bʌlʲˈtʲɪ] ‘white’ (nom.pl.m), balsiùs [bʌlʲˈsʲʊ̟s] ‘vowels’ (acc.pl), pjáuni [1ˈpʲjæˑʊnʲɪ] ‘(you) cut; saw; reap’ (sg). At the end of a word, the opposition between palatalized and non-palatalized consonants is neutralized to non-palatalized consonants (Balode & Holvoet Reference Balode, Holvoet, Dahl and Koptjevskaja-Tamm2001: 48), e.g. eĩti [2ˈɛɪˑtʲɪ] ‘go’ – eĩt [2ˈɛɪˑt] ‘go’, kélsiu [1ˈkʲæˑlʲsʲʊ̟] ‘(I) shall raise, lift’ – kel˜s [2ˈkʲɛlˑs] ‘(s/he, it, they) will raise, lift’.

The consonants /k ɡ/ in consonant clusters are only pronounced non-palatalized, even if there are palatalized consonants next to them (Girdenis 2001 [Reference Girdenis and Girdenis2000]: 411–413; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 37), e.g. žiñgsnis [2ˈₒʲɪŋʲˑksʲnʲɪs] ‘step’, vìrkdė [1ˈʋʲɪrʲɡdʲeː] ‘(s/he, it, they) made smb. cry’. The consonants /kʲ ɡʲ xʲ ɣʲ/ form a separate palatalized subgroup of palatalized velar consonants because they are articulated not by raising the tongue back farther towards the hard palate but by raising the tongue middle towards the hard palate (for a comparison of the acoustic features of the velar consonants /k ɡ/ and the palatalized velar consonants /kʲ ɡʲ/ see Indričāne & Urbanavičienė Reference Indričāne and Urbanavičienė2017: 33–72).

The articulation of the non-palatalized /l/ also differs sharply from that of /lʲ/, e.g. Lùkas [ˈlʊkʌs] ‘Luke’ (name) and liùkas [ˈlʲʊ̟kʌs] ‘hatch’, plãnas [2ˈplɐːnʌs] ‘plan’ and plýnas [1ˈpʲlʲiːnʌs] ‘bare; smooth; open’. The consonant /l/ can have a strongly velarized articulation and the tongue blade creates a dental contact. The palatalized /lʲ/ is articulated with the front part of the tongue touching the alveolar ridge (see Figures 2 and 3, for an animated view see TARTIS).

Figure 4 Locus equations: Lithuanian non-palatalized (![]() ) and palatalized (

) and palatalized (![]() ) consonants (male data).

) consonants (male data).

Note: The material for Figures 4–6 was read by six male speakers, aged 21–42 years. Each segment was repeated three times. There were 15 isolated prevocalic CVC sequences, i.e. about 270 tokens, for each consonant. Long CVC syllables were pronounced with a circumflex accent (because circumflex is the non-marked variant in the final syllable of words, including monosyllables).

The second formant of non-palatalized /l/ is lower than in the case of its palatalized counterpart /lʲ/, namely, in F2 stable part – male data [l] is 930 Hz, [lʲ] F2 – 1720 Hz; female data [l] F2 – 1210 Hz, [lʲ] F2 – 1860 Hz (Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 208). Acoustical investigation of the palatalization of consonants has revealed that locus equationsFootnote 6 (see Figure 4) conclusively show the difference between the palatalized and non-palatalized consonants (Ambrazevičius Reference Ambrazevičius2012: 15; Ambrazevičius & Leskauskaitė Reference Ambrazevičius and Leskauskaitė2014: 263; Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 279).

The F2 loci of palatalized consonants are compactly concentrated in the upper part of the coordinate plane, whereas the loci of non-palatalized consonants are less densely arranged in the lower part. This arrangement is determined by a general additional articulation (raising the body of the tongue towards the hard palate) characteristic of palatalized consonants, whereas non-palatalized consonants have no common articulatory component uniting them (Urbanavičienė Reference Urbanavičienė2019: 103–118). It was also noted that spectrum models of the palatalized consonants had more intensive spectral peaks or areas of energy concentration (Dereškevičiūtė Reference Dereškevičiūtė2013: 138). Palatalization also increases the relative amplitudeFootnote 7 of the palatalized obstruents (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Relative amplitude of Lithuanian fricatives and affricates: non-palatalized (![]() ) and palatalized (○) consonants (male data, 270 tokens for each consonant).

) and palatalized (○) consonants (male data, 270 tokens for each consonant).

In palatalized/non-palatalized pairs, apart from a couple of exceptions (i.e. [xʲ] and [x], [ₒʲ] and [ₒ]), the mean relative amplitude of the palatalized fricative or affricate is usually higher than that of the corresponding non-palatalized obstruent (Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 232).

Voiceless and voiced consonants

Only obstruents contrast in voicing, i.e. /p/ – /b/, /pʲ/ – /bʲ/, /t/ – /d/, /tʲ/ – /dʲ/, /k/ – /ɡ/, /kʲ/ – /ɡʲ/, /s/ – /z/, /sʲ/ – /zʲ/, /ʃ/ – /ₒ/, /ʃʲ/ – /ₒʲ/, /x/ – /ɣ/, /xʲ/ – /ɣʲ/, e.g. pùvo [ˈpʊʋoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) decayed’ : bùvo [ˈbʊʋoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) was/were’, kãras [2ˈkɐːrʌs] ‘war’ : gãras [2ˈɡɐːrʌs] ‘steam’, šìlas [ˈʃʲɪlʌs] ‘forest’ : žìlas [ˈₒʲɪlʌs] ‘grey’. The articulation of voiced and voiceless consonants is very similar (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 74): they are attributed to the same classes by both the place and the manner of articulation. Obstruents assimilate in voicing to a following obstruent and are voiceless word-finally (LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 44), e.g. nèšti [ˈnʲɛʃʲtʲɪ] ‘carry’ – nè[ž]damas [ˈnʲɛₒdʌmʌs] ‘when carrying’, skrìsti [ˈsʲkrʲɪsʲtʲɪ] ‘fly’ – skrì[z]damas [ˈsʲkrʲɪzdʌmʌs] ‘when flying’, vẽža [2ˈʋʲæːₒʌ] ‘(s/he, it, they) carries/carry’ – vè[š]ti [ˈʋʲɛʃʲtʲɪ] ‘carry’, láužia [1ˈlɐˑʊₒʲɛ] ‘(s/he, it, they) break(s)’ – láu[š]ti [1ˈlɐˑʊʃʲtʲɪ] ‘break’, daũg [2ˈdɒʊˑk] ‘many, much’ – dúok [1ˈduɔk] ‘(you) give’ (imperative, sg), lýg [1ˈlʲiːk] ‘like; as if’ – lìk [ˈlʲɪk] ‘(you) stay’ (imperative, sg). The approximants /j l lʲ m mʲ n nʲ r rʲ/ do not trigger voicing assimilation: they do not make a preceding voiceless consonant voiced and always remain voiced themselves (DLKG 2005: 33), e.g. pùslapis [ˈpʊslʌpʲɪs] ‘page’, kaitrà [kʌɪˈtrʌ] ‘heat’.

Featuring among the approximants are /ʋ ʋʲ/, which formally have voiceless fricative equivalents /f fʲ/; however, they do not form real functional pairs (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 74). At the end of a word, /ʋ ʋʲ/, similar to the approximant /j/, loses frication, becomes even more voiced and turns into the non-syllabic [ʊ̯], [ɪ̯], forming secondary diphthongs with the preceding vowels, e.g. sudiẽu [sʊ2ˈdʲiɛʊ̯] ‘good-bye’, jū́roj [1ˈju̟ːrɔɪ̯] ‘in the sea’, kėdėബj [kʲeː2ˈdʲeːɪ̯] ‘on a chair’ (for the breakup of diphthongs into a vowel and /j/ or /ʋ/ before the vowels, see section ‘Diphthongs’ below). On the one hand, phonologically /j ʋ ʋʲ/ do pattern with sonorants in permitting a preceding voiceless obstruent, but on the other hand, with fricatives in a stricture between the speech organs (see TARTIS). In earlier grammars (e.g. Vaitkevičiūtė 1965: 70), the consonants /ʋ ʋʲ j/ were regarded as intermediate between fricative consonants and approximants. The current studies on the phonetics of Lithuanian treat them in two ways: either as fricative consonants /v vʲ/ (e.g. Balode & Holvoet Reference Balode, Holvoet, Dahl and Koptjevskaja-Tamm2001: 48; Ambrazevičius & Leskauskaitė Reference Ambrazevičius and Leskauskaitė2014: 167; Pakerys Reference Pakerys2014: 91) or as approximants /ʋ ʋʲ/ that undergo full (or partial) vocalization (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 75; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 46; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 224; Kazlauskienė Reference Kazlauskienė2018: 50) and are generalized as phonemes. This Illustration presents the classical phonological classification of Lithuanian consonants, which assigns /ʋ ʋʲ/ to approximants. It should be noted that the contrast between approximants and voiced fricatives is also not sharply defined in other languages (e.g. Russian – Yanushevskaya & Bunčić Reference Yanushevskaya and Bunčić2015: 223; see also Johnson Reference Johnson2011: 122).

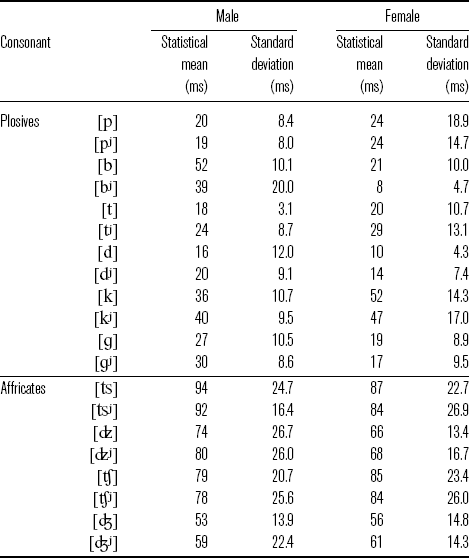

The voicing of obstruent consonants is evidenced by the duration of the release burstFootnote 8 – voiced stops have lower average statistical values compared to their voiceless counterparts with the same manner and place of the articulation (except for [b], [bʲ] and [p], [pʲ] in pronunciation of male, see Table 1). The duration of the release burst of voiceless plosives in Lithuanian is 26 ms (male), 33 ms (female) and that of voiced plosives is 23 ms (male; except for [b], [bʲ]), 15 ms (female); the duration of the release burst of voiceless affricates is 86 ms (male), 85 ms (female), voiced affricates – 67 ms (male), 60 ms (female).

Table 1 Duration of the release burst of Lithuanian plosives and affricates (540 tokens for each consonant) (according to Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 155).

Note: The material for Table 1 was read by six male and six female speakers, aged 21–42 years. There were 15 isolated prevocalic CVC sequences for each consonant. Each segment was repeated three times. There were 270 tokens by male and 270 tokens by female speakers.

The data for relative amplitude show (see Figure 5) that voiced fricatives and affricates typically have higher average statistical values compared to their voiceless counterparts: the relative amplitude of voiceless consonants is 0.620–0.790 dB; that of voiced consonants is 0.720–0.820 dB (Urbanavičienė & Indričāne Reference Urbanavičienė and Indričāne2016: 171; Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 283–284).

The differences in the voicing of plosive consonants do not affect the energy distribution across the spectrum, meaning the allocation of the consonant to a particular model of the FFT spectrum – diffuse flat/falling spectrum vs. compact spectrum. Nor is the contrast in the consonants being voiced/voiceless evident in the frequency of the spectral peak of obstruent consonants, as the differences in the values of voiced obstruent consonants and their voiceless counterparts are rather variable (Urbanavičienė et al. Reference Urbanavičienė, Indričāne, Jaroslavienė and Grigorjevs2019: 278–279).

Affricates

Lithuanian affricates are closer in duration to fricatives than to plosives – compare the duration of the release burst: [t] – 18 ms, [ʦ] – 94 ms; [d] – 16 ms, [ʣ] – 74 ms (see Table 1). The statistical mean and standard deviation of the frequencies of the spectral peak of affricates and the corresponding fricatives [s], [z], [ʃ], [ₒ] are also higher than those of the plosives [t], [d] (see Figure 6).

Figure 6 Spectral peaks of Lithuanian affricates, fricatives [s], [z], [₃], [ʒ] and plosives [t], [d]: voiceless (![]() ) and voiced (

) and voiced (![]() ) consonants (male data;

) consonants (male data; ![]() ,

, ![]() in the center indicates statistical mean;

in the center indicates statistical mean; ![]() ,

, ![]() on the left – statistical mean – standard deviation;

on the left – statistical mean – standard deviation; ![]() ,

, ![]() on the right – statistical mean + standard deviation).

on the right – statistical mean + standard deviation).

The main language-specific patterns of assimilation

In the Lithuanian language, there is regressive (A←B) and progressive (A→B), as well as close (contact) and remote (distant), partial and total assimilation (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 178). Regressive close assimilation is most common. Cases of progressive and distant assimilation are found in dialects as well as in diachronic phonetic processes. Lithuanian (as well as e.g. North Slavic languages) is characterized by a particular sensitivity to the context of vowel realization, i.e. by accommodative pronunciation, where the realizations of sounds in adjacent positions overlap (Sawicka Reference Sawicka2007: 83).

Adjacent sounds in Lithuanian assimilate as follows:

-

1. According to voicing, e.g. võgti [2ˈʋoːktʲɪ] ‘steal’, grį̃žk [2ˈɡrʲiːʃk] ‘(you) come back’ (imperative, sg), nèšdavo [ˈnʲɛₒdʌʋoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) used to carry’, vìrkdė [1ˈʋʲɪrʲɡdʲeː] ‘(s/he, it, they) made smb. cry’, išgir˜do [iₒʲ2ˈɡʲɪrˑdoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) heard’. The sonorants do not participate in this assimilation (see section ‘Voiceless and voiced consonants’ above). Assimilation according to activity of vocal cords is partial because consonants still differ in other features, i.e. no two identical consonants are obtained.

-

2. According to the place of articulation. This type of assimilation can be partial (e.g. vabzdžių̃ [ʋʌbʲₒʲ2ˈʒʲu̟ː] ‘insects’ (gen.pl)) or total (e.g. pùsšimtis [ˈpʊʃʲɪmʲtʲɪs] ‘fifty’, ùžzvimbė [ˈʊzʲʋʲɪmʲbʲeː] ‘(s/he, it, they) hummed’). In the case of total assimilation, when two identical consonants are obtained, additionally degemination takes place, i.e. one of two consonants is omitted. Fricative compounds (S–S type, two (post)alveolar fricatives) are not the same duration as in a similar word with a singleton, e.g. a morphological boundary (pus- + -šimtis) increases the duration of the compound by a factor of approximately 1.06, and can be interpreted as an open juncture (Strimaitienė & Girdenis Reference Strimaitienė and Girdenis1978: 64).

-

3. According to palatalization, e.g. viščiùkas [ʋʲɪʃʲˈʧʲʊ̟kʌs] ‘chicken’, verĩsti [2ˈʋʲɛrʲˑsʲtʲɪ] ‘turn, overthrow, force’, spjáuti [1ˈsʲpʲjæˑʊtʲɪ] ‘spit’. This assimilation is partial because consonants are adjusted only by palatalization.

Consonants can be combined according to several features at the same time, i.e. according to voicing and the place of articulation (e.g. užsãkymas [ʊ2ˈsɐːkʲiːmʌs] ‘order’, pùsžalis [ˈpʊₒʌlʲɪs] ‘half-baked, half-raw’), according to the place of articulation and palatalization (e.g. anksčiaũ [ʌŋʲkʃʲ2ˈʧʲɛʊˑ] ‘earlier’, pãvyzdžio [2ˈpɐːʋʲiːₒʲʒʲoː] ‘example’ (gen.sg)), and according to the activity of the vocal cords and the place of articulation and palatalization (e.g. mègzčiau [ˈmʲɛkʃʲʧʲɛʊ] ‘(I) would knit’, pùsžiemis [ˈpʊₒʲiɛmʲɪs] ‘semi-winter’, ùžsienis [ˈʊsʲiɛnʲɪs] ‘foreign countries’).

At morpheme boundaries the consonants are also assimilated. There are productive alternations that exist for all types of assimilation: one morphologically related form shows the alternation and the other does not, e.g. assimilation of voicing (sė́sti [1ˈsʲeːsʲtʲɪ] ‘to sit’– sė́[z]davo [1ˈsʲeːzdʌʋoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) used to sit’, dè[k]ti [ˈdʲɛktʲɪ] ‘burn’ – dẽga [2ˈdʲæːɡʌ] ‘it burns’); assimilation of palatalization (laisviaũ [lʌɪ2ˈsʲʋʲɛʊˑ] ‘more freely’ – laisvaĩ [lʌɪ2ˈsʋʌɪˑ] ‘freely’, geriaũ [ɡʲɛ2ˈrʲɛʊˑ] ‘better’ – geraĩ [ɡʲɛ2ˈrʌɪˑ] ‘good’).

Due to the interaction with the adjacent velar and palatalized velar consonants /k kʲ ɡ ɡʲ/, the nasal sonorants /n nʲ/ become velar; velar allophones [ŋ ŋʲ] are articulated, e.g. sniñga [2ˈsʲnʲɪŋˑɡʌ] ‘it snows’, añka [2ˈʌŋˑkʌ] ‘(s/he, it, they) goes/go blind’ (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 86–87; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 4–45; Kazlauskienė Reference Kazlauskienė2018: 58–61).

Geminates arising across morpheme or word boundaries degeminate in Lithuanian, e.g. pùsseserė (< pus- + seserė) [ˈpʊsʲɛsʲɛrʲeː] ‘cousin’ (f), iššóko (< iš- + šoko) [ɪ1ˈʃoːkoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) jumped out’, užsùko (< už- + suko) [ʊˈsʊkoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) twisted; turned; turned off; screwed up’. Degemination occurs at the junction of the prefix and the root or two stems; also, by adding a clitic to an independent word. At the junction of two independent words, both single consonant (if the words are closely related) or two consonants (in one or more features) can be pronounced (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 175).

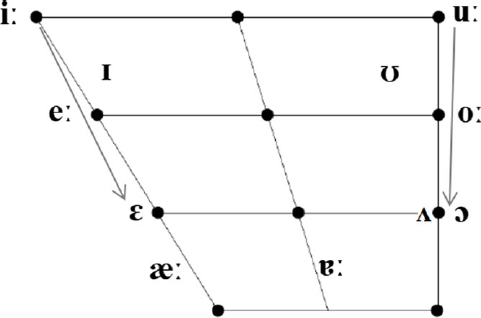

Vowels

The latest linguistic studies on Lithuanian (LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 28; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2009: 213–242; Reference Girdenis2014: 113, 201–214; Kazlauskienė Reference Kazlauskienė2018: 40) suggest that the vowel system of Standard Lithuanian consists of the following vowel phonemes of uniform (or non-gliding) and gliding (non-uniform) articulation: the short monophthongs /ɪ ɛ ʌ ɔ ʊ/, the long monophthongs /iː eː æː ɐː oː uː/ and the gliding diphthongs /iɛ uɔ/Footnote 9 which are characterized by the closeness of the articulation of the components and thus differ from other Lithuanian diphthongs /ʌɪ ɒʊ ɛɪ ʊɪ ɛʊ ɔɪ ɔʊ/ (see the vowel chart above, where arrows indicate variable articulation of /iɛ uɔ/). In the phonological system of Standard Lithuanian, the /iɛ uɔ/ function as independent long vowels consisting of stable sounds, i.e. the vowel and a glide component, which is pronounced differently depending on the prosodic features and co-articulation with the first component and the adjacent consonant. The diphthongs /iɛ uɔ/ glide in the direction of increasing back and open articulation, but it is complicated to divide it into two separate components, therefore the entire diphthong is considered to be the syllable center. This is one of many reasons to regard /iɛ uɔ/ as members of the phonological system of vowels rather than diphthongs. Additionally, similar to long vowels, /iɛ uɔ/ participate in the same morpho-phonological alternations and before vowels they are not broken up into two syllables as diphthongs are (see Tables 2 and 3).

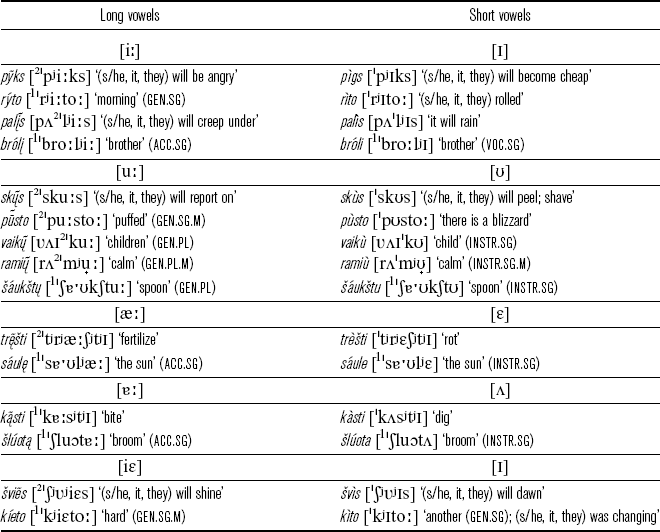

Table 2 Quantitative oppositions of the Lithuanian vowels.

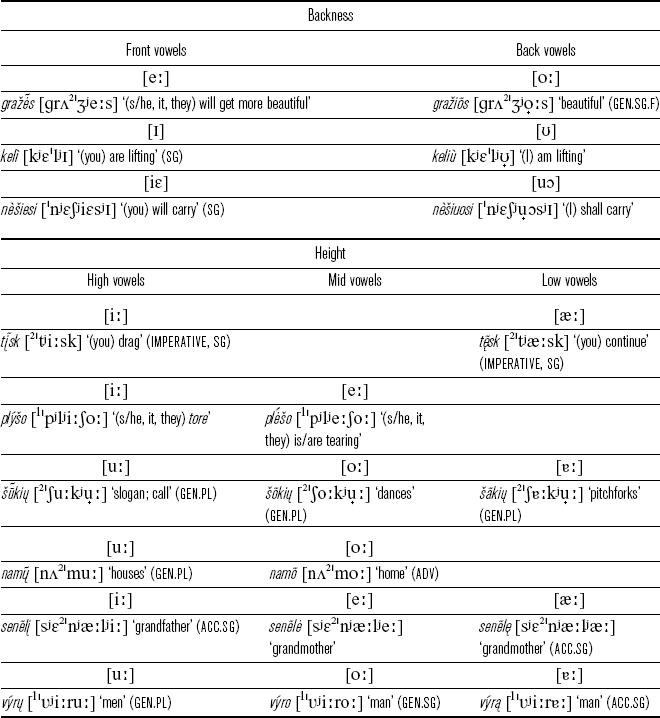

Table 3 Qualitative oppositions of the Lithuanian vowels.

The Lithuanian short phoneme /ɔ/ is to be regarded as marginal because [ɔ] is mainly used in words of foreign origin and some proper nouns. The short optional phoneme /e/ is also to be regarded as marginal. Instead of the optional close mid-high vowel [e] used only in borrowed words, usually the simple short [ɛ] is articulated. Moreover, speakers of Standard Lithuanian cannot pronounce the short /e/ as a separate sound in isolation (Jaroslavienė Reference Jaroslavienė2015; Jaroslavienė et al. Reference Jaroslavienė, Grigorjevs, Urbanavičienė and Indričāne2019). In Aleksas Girdenis’ opinion, the short sound [e] ‘should not be considered a true (even if marginal) phoneme since its purpose is not distinctive. Nor do its optional usage and special expressive nuance allow us to treat it as a normal phoneme. In the best case, it is only a phoneme of certain urban sociolects’ (Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 202). However, the sounds [e] and [ɛ] are not functionally identical; the accented vowel in borrowed words does not become longer, whereas the accented Lithuanian one does (see examples under the vowel chart).

Quantitative and qualitative oppositions testify to the independent phonemic status of vowel quality and quantity, although quantitative oppositions are also accompanied by qualitative differences; the meaning of a word depends on the quantity (duration) and the quality of vowels (see Tables 2 and 3). Quantitative oppositions are preserved in both accented and unaccented positions of a word.

The length of Lithuanian vowels can be positional (when vowels become longer under stress, e.g. rẽtas [2ˈrʲæːtʌs] ‘rare’ : retàs [rʲɛˈtʌs] ‘rare’ (acc.pl.f), rãktas [2ˈrɐːktʌs] ‘key’ : raktù [rʌkˈtʊ] ‘key’ (instr.sg), or inherited or historical (when vowels are long in both the accented and unaccented positions), e.g. gėlėബ [ɡʲeː2ˈlʲeː] ‘flower’, gė́ lė [1ˈɡʲeːlʲeː] ‘(s/he, it, they) ached; stung’, ródo [1ˈroːdoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) show(s)’, namõ [nʌ2ˈmoː] ‘home’ (adv); drį̃sti (< Proto-Lith.Footnote 10 *drinsti) [2ˈdʲrʲiːsʲtʲɪ] ‘dare’, drąĩsą (< Proto-Lith. *dransan) [2ˈdrɐːsɐː] ‘courage’ (acc.sg), lū́pu (< Proto-Lith. * lūpun) [1ˈluːpuː] ‘lips’ (gen.pl), skų́sti (< Proto-Lith. *skunsti) [1ˈskuːsʲtʲɪ] ‘report on’, skę˜sta (< Proto-Lith. *skensta) [2ˈsʲkʲæːstʌ] ‘(s/he, it, they) sink(s)’ (see e.g. Kazlauskienė Reference Kazlauskienė2018: 40–41). The origins of the inherited and historical lengths of vowels differ; the former are inherited as long, and are most often denoted by long vowels, whereas the latter arose from nasal vowels and are denoted in the orthography by nasal letters, although it can be said that today no nasality is preserved.

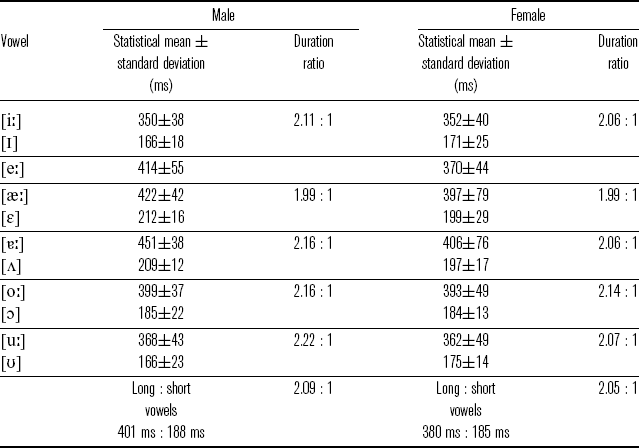

Long vowels are more peripheral in the vowel space. The latest instrumental investigations show (e.g. Grigorjevs & Jaroslavienė Reference Grigorjevs and Jaroslavienė2015b: 79; Jaroslavienė et al. Reference Jaroslavienė, Grigorjevs, Urbanavičienė and Indričāne2019) that [ɛ ʌ] of Standard Lithuanian are the longest of the short vowels, whereas [æː ɐː] are the longest of the long vowels; the short [ɪ ʊ] are the shortest of the short vowels, and [iː uː] are the shortest of the long vowels. In terms of duration, other vowels ([ɔ] of the short vowels and [eː oː] of the long vowels) occupy the intermediate position: they are shorter than the corresponding short and long low vowels but longer than the corresponding high vowels. The duration ratio of short and long vowels pronounced in isolation is about two to one (see Table 4). Such regularities essentially conform to tendencies established by earlier researchers (see Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 43–48).

Table 4 Duration of the Lithuanian long and short vowels in CVC sequences (according to Jaroslavienė et al. Reference Jaroslavienė, Grigorjevs, Urbanavičienė and Indričāne2019: 142).

Note: The material for Table 4 was read by six male and six female speakers, aged 21–42 years. There were 23 isolated CVC sequences for each vowel, which was repeated three times. There were 414 tokens by male and 414 tokens by female speakers. Mean value was calculated as the average of all realizations of the sound.

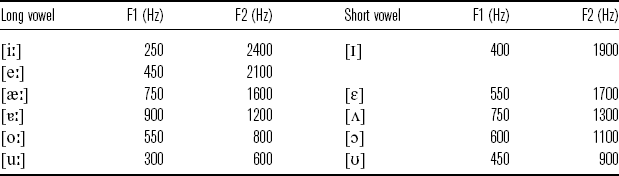

Lithuanian long and short vowels differ greatly in their quality (see LG Reference Ambrazas2006, Grigorjevs & Jaroslavienė Reference Grigorjevs and Jaroslavienė2015a, Jaroslavienė Reference Jaroslavienė2017, Jaroslavienė et al. Reference Jaroslavienė, Grigorjevs, Urbanavičienė and Indričāne2019). Qualitative variations of vowels depend on the adjacent sounds and other factors (see Ledichova Reference Ledichova2020; also variation of sounds in Lithuanian dialects in Bakšienė & Čepaitienė Reference Bakšienė and Čepaitienė2017).

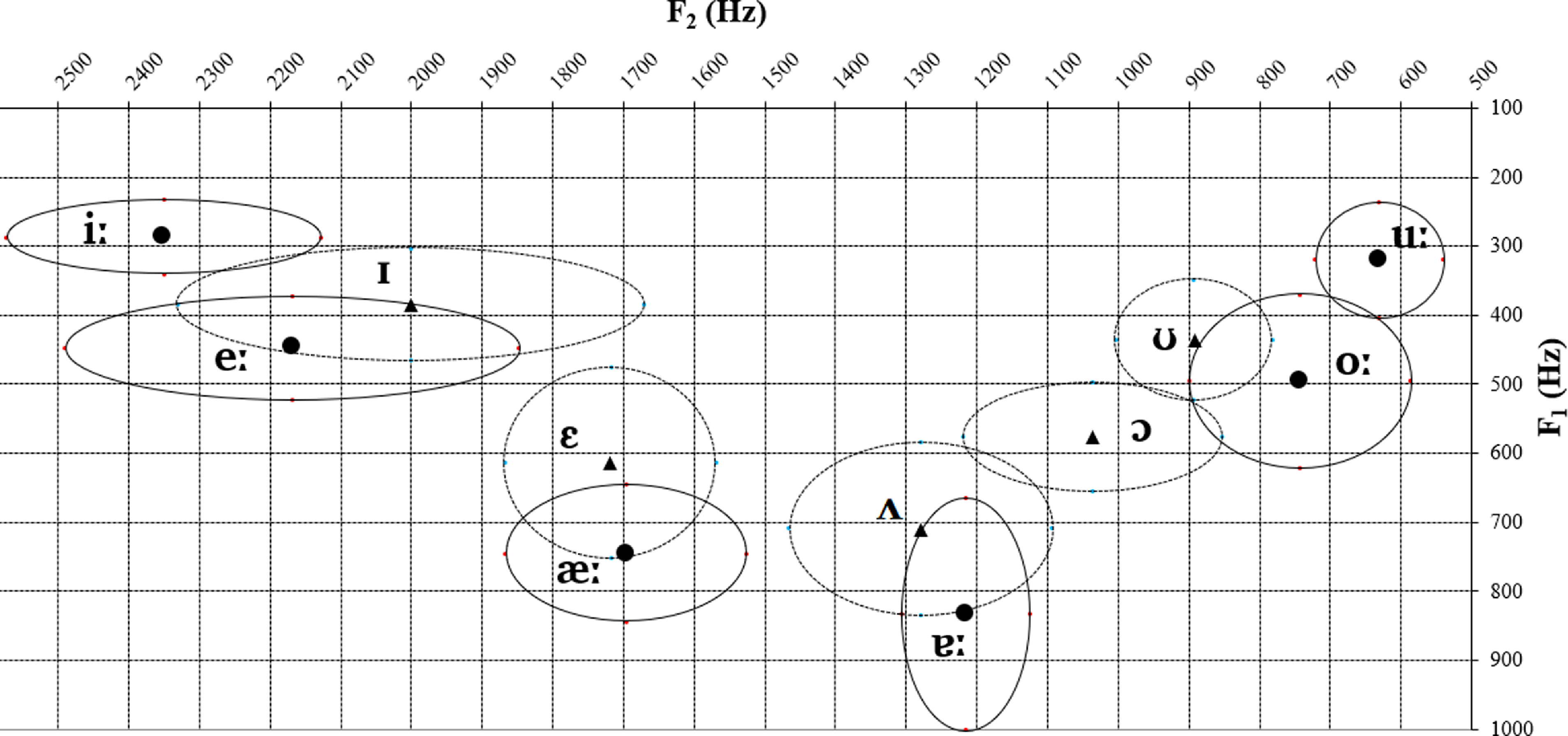

Classification and spectral characteristics of vowels

According to the backness of articulation (see Figure 7), front vowels (long phonemes /iː iɛeː æː/ and short phonemes /ɪ ɛ/) and back (long phonemes /uː uɔoː ɐː/ and short phonemes /ʊ ɔ ʌ/) are distinguished in Lithuanian linguistics. According to the formant data, the Lithuanian short [ʌ], especially when pronounced by females, seems to be close to the schwa-like vowel, as its F2 exceeds the threshold of 1500 Hz; however, the calculated data for the male voice (see Table 5 and Figure 7) show a much lower F2 for [ʌ], closer to the back vowels; moreover, this vowel has highly variable F2 values (the male voice is approximately 1100 Hz to 1450 Hz, see Figure 7). In Lithuanian linguistics, it is customary to consider the vowel [ʌ] as a back vowel, taking into account phonological criteria: short /ʌ/ functions as a back vowel – non-palatalized consonants are used before it as before other back vowels. The latest textbooks on the phonetics and phonology of the Standard Language treat the short /ʌ/ as a back vowel (see Kazlauskienė Reference Kazlauskienė2018: 34–35; see also Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003, Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014, Grigorjevs & Jaroslavienė Reference Grigorjevs and Jaroslavienė2015b, Jaroslavienė Reference Jaroslavienė2017). In the Lithuanian language, the back vowels [uː uɔoː ʊɔ] that follow palatalized consonants become slightly advancedFootnote 11 (e.g. gerù [ɡʲɛˈrʊ] ‘good’ (instr.sg.m) : geriù [ɡʲɛˈrʲʊ̟] ‘(I) am drinking’), and [ɐː ʌ] become completely front (e.g. galià [ɡʌˈlʲɛ] ‘power’ : galè [ɡʌˈlʲɛ] ‘at the end’, žãlią [2ˈₒɐːlʲæː] ‘green’ (acc.sg) : žõlę [2ˈₒoːlʲæː] ‘grass’ (acc.sg)) and therefore are transcribed as corresponding front vowels [æː ɛ] (see e.g. Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014, Kazlauskienė Reference Kazlauskienė2018).

According to the distance between the tongue and the palate, the following vowels are distinguished in Lithuanian linguistics as high (i.e. close long /iː uː/ and short /ɪ ʊ/), mid (long /eː oː/ and short /ɔ/) and low (open long /ɐː æː/ and short /ʌ ɛ/) vowels (see Figure 7 and the vowel chart). As mentioned, /iɛ uɔ/ are regarded as vowels of gliding articulation.

The results of the present paper confirm the general tendency that the qualitative characteristics of the Lithuanian long and corresponding short vowels differ to a great extent (see Figure 7). According to the movement of the lips, Lithuanian vowels are divided into rounded or labial (/uː oː ʊ ɔ/) and unrounded or non-labial (/iː eː æː ɐː ɪ ɛ ʌ/).

Table 5 Values of F1 and F2 for Standard Lithuanian long and short vowels (male data; according to Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 238).

Note: The values of F1 have been rounded to the nearest 50 Hz and the values of F2 have been rounded to the nearest 100 Hz.

Figure 7 Mean values of the Lithuanian vowels in the acoustic F2/F1 (Hz) plane. The ellipses explain 99.72% of the data according to the calculated standard deviation (male data, 33 tokens for each vowel; circles represent long vowels, triangles represent short vowels).

Diphthongs

The Lithuanian language has a rich inventory of diphthongal sounds: diphthongs and VR-type (vowel + sonorant) diphthongoid sequences (see the diphthongs chart above, where arrows indicate variable articulation of diphthongs and dashed arrows indicate marginal diphthongs). Diphthongs are considered to be /ʌɪ ɒʊ ɛɪ ʊɪ/ and the marginal /ɛʊ ɔɪ ɔʊ/;Footnote 12 VR-type diphthongoid sequences are the following: /ʌl ɛl ɪl ʊl ʌm ɛm ɪm ʊm ʌn ɛn ɪn ʊn ʌr ɛr ɪr ʊr/, e.g. vaĩkas [2ˈʋʌɪˑkʌs] ‘child’, vaikaĩ [ʋʌɪ2ˈkʌɪˑ] ‘children’, láuk [1ˈlɐˑʊk] ‘(you) wait’ (imperative, sg), laũk [2ˈlɒʊˑk]Footnote 13 ‘get away!; out’ (adv), laukè [lɒʊˈkʲɛ] ‘outside’, reĩkia [2ˈrʲɛɪˑkʲɛ] ‘it is necessary’, muĩlas [2ˈmʊɪˑlʌs] ‘soap’, terapeũtas [tʲɛrʌ2ˈpʲɛʊˑtʌs] ‘therapist’, boikòtas [bɔɪˈkɔtʌs] ‘boycott’, klòunas [1ˈklɔʊnʌs] ‘clown’, káltas [1ˈkɐˑltʌs] ‘chisel’, kal˜tas [2ˈkʌlˑtʌs] ‘guilty’, kaltàs [kʌlˈtʌs] ‘guilty’ (acc.pl.f), délnas [1ˈdʲæˑlnʌs] ‘palm’, peñktas [2ˈpʲɛŋˑktʌs] ‘the fifth’, ker˜pa [2ˈkʲɛrˑpʌ] ‘(s/he, it, they) cut(s)’, gìnti [1ˈɡʲɪnʲtʲɪ] ‘defend’, pìrmas [1ˈpʲɪrmʌs] ‘the first’, kùrmis [1ˈkʊrʲmʲɪs] ‘mole’, vìrti [1ˈʋʲɪrʲtʲɪ] ‘boil’, etc. Two adjacent sounds are united into a diphthong by the fact that they form the base of a long syllable and have a common accent as well as form the basis for the distinction in syllable tonemes (LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 25; see also next section, ‘Prosodic system’). Diphthongs and VR-type diphthongoid sequences occur only before consonants and a juncture, whereas before vowels they are broken up into two syllables or a vowel and /j/ or /ʋ/, e.g. kìlti [1ˈkʲɪlʲtʲɪ] ‘rise’ : kìlo [ˈkʲɪloː] ‘(s/he, it, they) rose’, kùrti [1ˈkʊrʲtʲɪ] ‘create’ : kùria [ˈkʊrʲɛ] ‘(s/he, it, they) create(s)’, gìnti [1ˈɡʲɪnʲtʲɪ] ‘defend, drive’ : ginù [ɡʲɪˈnʊ] ‘(I) defend, drive’, gùiti [1ˈɡʊɪtʲɪ] ‘drive; scold’ : gujù [ɡʊˈjʊ] ‘(I) am driving, scolding’. Both elements of diphthongs and VR-type diphthongoid sequences can be interchanged: laũkas [2ˈlɒʊˑkʌs] ‘field’: laĩkas [2ˈlʌɪˑkʌs] ‘time’ : lañkas [2ˈlʌŋˑkʌs] ‘bow’, kaĩsti [2ˈkʌɪˑsʲtʲɪ] ‘become heated’: kuĩsti [2ˈkʊɪˑsʲtʲɪ] ‘rummage’ : keĩsti [2ˈkʲɛɪˑsʲtʲɪ] ‘change’, veĩsti [2ˈʋʲɛɪˑsʲtʲɪ] ‘breed’ : ver˜sti [2ˈʋʲɛrʲˑsʲtʲɪ] ‘turn over; force’, etc.

Vowel elements of unaccented diphthongs are short. Qualitative features of elements that were lengthened due to the accent become more pronounced; these accented elements qualitatively can also be close to the long vowels (see section ‘Prosodic system’ below).

Long vowels or diphthongs followed by a tautosyllabic sonorant consonant are limited to word-final position or the first element in a compound, i.e. morphologically complex forms, e.g. vėബl [2ˈʋʲeːl] ‘again’, kõrtos [2ˈkoːrtoːs] ‘cards’, žemỹn [ₒʲɛ2ˈmʲiːn] ‘downwards’, sū́rmaišis [1ˈsuːrmʌɪʃʲɪs] ‘cheese-bag’, laũmžirgis [2ˈlɒʊˑmʲₒʲɪrʲɡʲɪs] ‘dragon-fly’, rainmar˜gis [rʌɪn2ˈmʌrʲˑɡʲɪs] ‘variegated in streaks’.

Prosodic system

Stress

Stress in the Lithuanian language is free, i.e. it can occur on any syllable of a word: the ultimate, the penultimate, the first and any other. Alongside its universal culminative function, which is fulfilled by stresses of all types, this type of stress primarily performs a distinctive function because the place of a word stress can distinguish lexical and grammatical meanings of words, as seen in the minimal pairs kìlimas [ˈkʲɪlʲɪmʌs] ‘carpet’ : kilìmas [kʲɪˈlʲɪmʌs] ‘rise’ (noun), gìria [ˈɡʲɪrʲɛ] ‘(s/he, it, they) praise(s)’ : girià [ɡʲɪˈrʲɛ] ‘forest’, kìtas [ˈkʲɪtɐs] ‘another’ : kitàs [kʲɪˈtʌs] ‘others’ (acc.pl.f), nèši [ˈnʲɛʃʲɪ] ‘(you) will carry’ (sg) : nešì [nʲɛˈʃʲɪ] ‘(you) are carrying’ (sg), etc. (Balode & Holvoet Reference Balode, Holvoet, Dahl and Koptjevskaja-Tamm2001: 49; Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 217–218; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 53–54; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 272–273; Stundžia Reference Stundžia2014b: 12).

In longer words with at least three syllables, alongside the primary stress, one or several secondary stresses can be optionally realized, e.g. mókytojo [1ˈmoːkʲiːˌtoːjoː] ‘teacher’s’, pùskepalis [ˈpʊsʲkʲɛˌpʌlʲɪs] ‘half a loaf’, pasidarýdavo [pʌˌsʲɪdʌ1ˈrʲiːdʌˌʋoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) used to make something for oneself, used to become’. Secondary stresses are most often found in long words of foreign origin made of several clearly perceived components, e.g. aerohidroterãpija [ˌʌɛrɔˌɣʲɪdrɔtʲɛ2ˈrɐːpʲɪjɛ] ‘airhydrotherapy’ (Pakerys Reference Pakerys2003: 218; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 54; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 280–282).

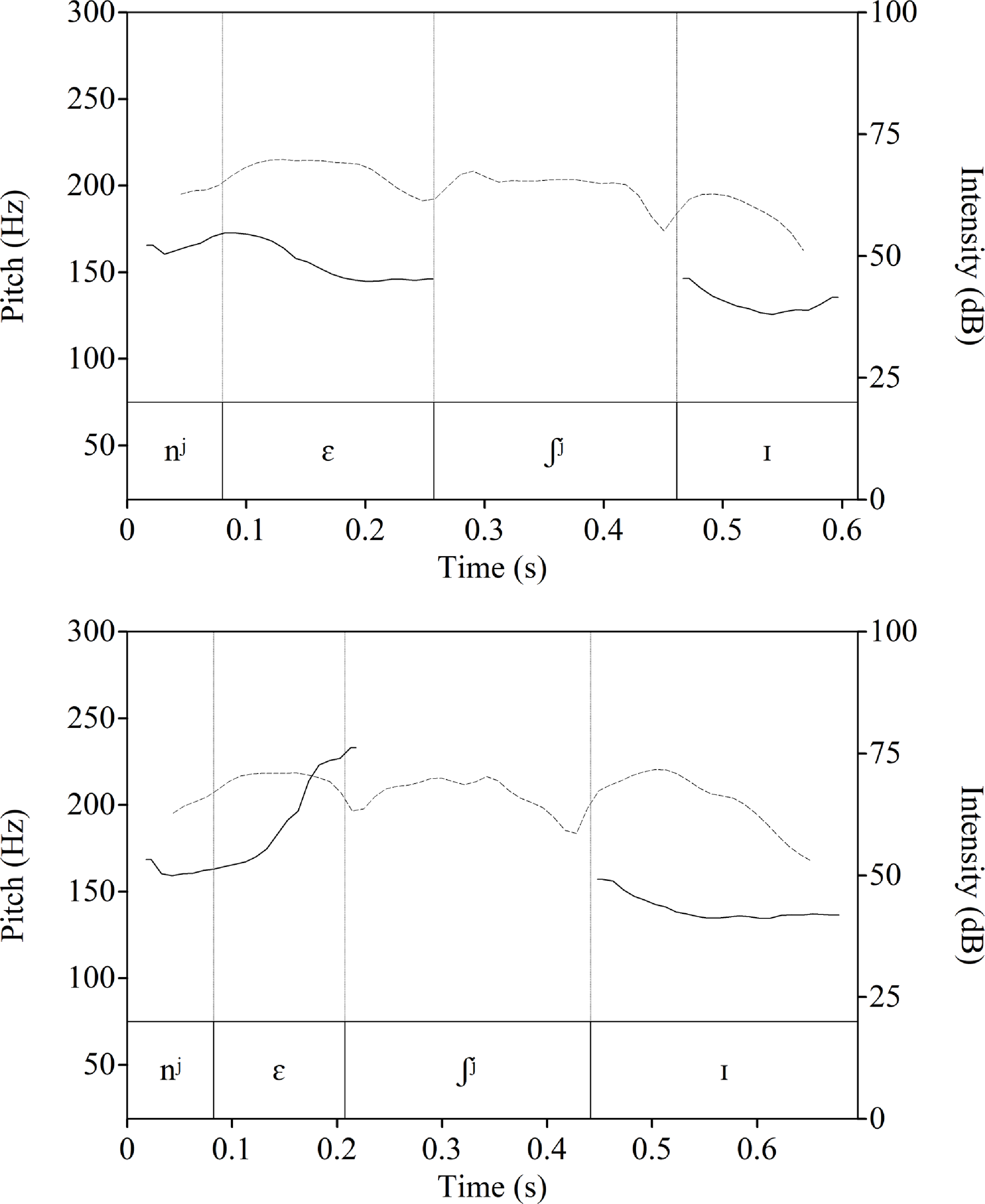

The Lithuanian syllable nucleus, which can consist of vowels, diphthongs and VR-type diphthongoid sequences, can be accentuated with respect to other syllables by a complex of several prosodic features. The most prominent and stable feature of stressed syllables is the longer duration of the center of the syllable, while accented vowels also have more prominent qualitative features. The features of f0 and intensity may vary depending on the intonation of the phrase. The unaccented syllables are always less distinctly articulated quantitatively and qualitatively (see Figures 8 and 9, and Table 6).Footnote 14

Figure 8 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of stressed and unstressed short vowels in Lithuanian [ˈkʲɪt₌s] (top panel) vs. [kʲɪˈt₌s] (bottom panel) (female data).

Figure 9 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of stressed and unstressed short vowels in Lithuanian [ˈnʲ┋₃ʲɪ] (top panel) vs. [nʲ┋ˈ₃ʲɪ] (bottom panel) (female data).

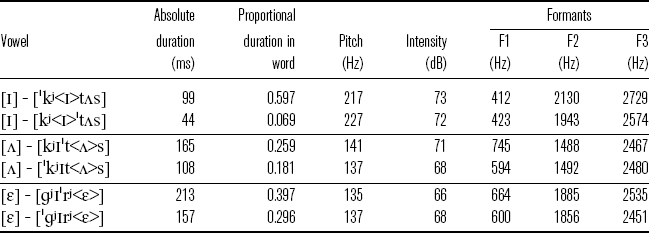

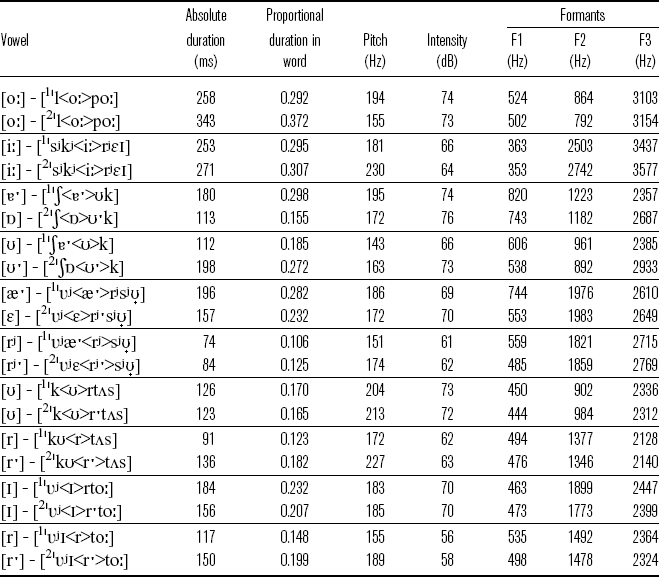

Table 6 Prosodic features of stressed and unstressed Lithuanian short vowels (female data). The investigated vowel is given in angle brackets < >.

Note: Proportional duration is calculated by dividing the vowel duration of the subject by the total word duration. The values of pitch, intensity and formants of the vowels were calculated by averaging all the values of the middle part of the sound (three tokens).

The prosody of Standard Lithuanian was systematically studied by experimental methods at the end of the 20th century (Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982).Footnote 15 Based on the data from this study, it can be stated that the short stressed vowels are about 1.16 times longer, slightly higher in pitch and by 1.8 dB more intense than the corresponding unstressed vowels in analogical positions. The nuclei of the long syllables are even longer, higher and more intense in a stressed position (Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 111–133, 193–196).

Pitch accent (toneme)

In Standard Lithuanian, stressed long syllables consisting of the same phonemes are pronounced differently; they are distinguished by a prosodic element of a syllable. The pitch accent, often referred to as toneme, is defined as a certain modulation of the long stressed syllable, particularly its pitch, intensity and quantity (and in some cases quality as well), performing a distinctive function (Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 147; Reference Pakerys2003: 219, 222; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 55; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 287–291, 298; Stundžia Reference Stundžia2014a: 24–27; Rinkevičius Reference Rinkevičius2015: 18–19, 21–23; Bakšienė Reference Bakšienė2016: 44–45).

Since one of the most significant elements in the realization of Lithuanian pitch accents is pitch modulation, in some literature this prosodic element is simply called tone and Lithuanian is attributed to the group of tonal languages (see e.g. Martinet Reference Martinet1970: 364, 378; Fromkin, Rodman & Hyams Reference Fromkin, Rodman and Hyams2007: 243; Radford et al. Reference Radford, Martin Atkinson, Clahsen and Spencer2009: 43–44; Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 291; Rinkevičius Reference Rinkevičius2015: 17–18; Švageris Reference Švageris2015: 10; Kardelis Reference Kardelis2017: 6–8). However, it should be emphasized that Lithuanian pitch accents are differentiated by a whole complex of prosodic features (see further); neither the pitch parameters nor changes in the features of a syllable pitch perform any independent distinctive function as they do in real tonal languages. Therefore, in the Lithuanian phonological tradition, which follows the tradition of the Prague Phonological School, Lithuanian is not typically considered a tonal language; instead, it is identified as a pitch accent language. In Lithuanian, like in Latvian, Norwegian, Swedish, Slovenian, and Serbo-Croatian, pitch features are associated with accentuation – only the pitch accents, or tonemes, of stressed long syllables essentially contrast (Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 307; Bakšienė Reference Bakšienė2016: 41–44; see also Jakobson Reference Jakobson1962: 122).

Two phonological pitch accents exist in Standard Lithuanian and all its dialects, namely the acute accent (labelled here with a superscript 1) and the circumflex accent (labelled with superscript 2), which contrast in stressed long syllables, those containing long vowels, diphthongs and VR-type diphthongoid sequences, e.g. kóšė [1ˈkoːʃʲeː] ‘(s/he, it, they) strained’ : kõšė [2ˈkoːʃʲeː] ‘porridge’, káltas [1ˈkɐˑltʌs] ‘chisel’ : kal˜tas [2ˈkʌlˑtʌs] ‘guilty’, kùrpė [1ˈkʊrʲpʲeː] ‘sabot’ : kur˜pė [2ˈkʊrʲˑpʲeː] ‘(s/he, it, they) mended smth. poorly’.

The problem of marking Lithuanian pitch accents with IPA symbols should be discussed separately. In Lithuanian, it is common to show the accentuation of a vowel with the acute accent symbol (′) and the circumflex accent (ബ), e.g. výras ‘man’, kãla ‘(s/he, it, they) hammer(s)’, sáulė ‘the sun’, vaĩkas ‘child’, gérti ‘drink’, kar˜tas ‘time’, etc. (Stundžia Reference Stundžia2014b: 9). However, the first diacritic represents high tone in the IPA system, and the second diacritic indicates a nasalized sound (see IPA 2015). The rise of the pitch contour in the IPA system is marked with the diacritic [̌], and its fall is signalled by [^]. The same symbols could be suggested for marking the Lithuanian accents having written the diacritic of the main stress before the stressed syllable, e.g. výras [ˈʋʲÌːrʌs], kãla [ˈkɐ̌ːlʌ], sáulė [ˈsɐˑʊlʲeː], vaĩkas [ˈʋʌɪ̌ˑkʌs], gérti [ˈɡʲæˑrʲtʲɪ], kar˜tas [ˈkʌřˑtʌs]. However, pitch features are not the only ones in which Lithuanian accents differ. Moreover, the acute accent is not always used to note the falling pitch contour, and the circumflex accent is not always used to note the rising pitch contour; contours of both accents can be very different (for more about this see Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 163–173). In languages such as Norwegian with prosodic units similar to those of Lithuanian, tonemes are marked by numbers placed before a stressed syllable and what those numbers symbolize is explained separately (Kristoffersen Reference Kristoffersen2007: 11). Asta Kazlauskienė (Reference Kazlauskienė2018: 8, 19) also suggests marking the accents of the Lithuanian language in the same way as in Norwegian. It has been decided to apply an analogous system in this Illustration: the raised number 1 signals the acute accent before a stressed syllable, the raised number 2 marks the circumflex accent (see their prosodic features below), e.g. výras [1ˈʋʲiːrʌs], kãla [2ˈkɐːlʌ], sáulė [1ˈsɐˑʊlʲeː], vaĩkas [2ˈʋʌɪˑkʌs], gérti [1ˈɡʲæˑrʲtʲɪ], kar˜tas [2ˈkʌrˑtʌs].

In Lithuanian, an accent opposition does not exist in unstressed syllables or in stressed syllables containing a short vowel in an open syllable or a short vowel with obstruent coda (Balode & Holvoet Reference Balode, Holvoet, Dahl and Koptjevskaja-Tamm2001: 50–51; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 57–58; Petit Reference Petit2010: 53–55, 60–63; Stundžia Reference Stundžia2014b: 12). Such a pattern of pitch accent distribution is typical of many world languages that have lexical tone oppositions (Gordon Reference Gordon2002: 9–22). At the beginning of the 21st century, Lithuanian linguistics is of the opinion that in the Standard language, a systematic contrast of pitch accents exists only in the syllables containing a diphthong or sonorant coda, while in the monophthongal syllables the contrast of pitch accents is not systemic, the opposition of the pitch accents is often levelled. The signs of levelling of pitch accents are most pronounced in the speech of speakers of major cities, including Vilnius (for a review of the discussion, see Bakšienė Reference Bakšienė2016: 46–50).

The functional features of accents are very important in Lithuanian. At the morphological level, the accent is defined as a stable characteristic of a morpheme (Girdenis Reference Girdenis2014: 298; see also Hjelmslev Reference Hjelmslev1936–37: 8; Kuryłowicz Reference Jerzy1987: 71; van der Hulst 2010: 451). Each morpheme that can receive a stress and which contains a long rime, i.e. contains a long vowel or a diphthong or a coda sonorant, is acute or circumflex by nature. Accentual features of morphemes, including accents, as well as their combinations, determined the formation of the complicated Lithuanian accentuation system (Petit Reference Petit2010: 64–70; Stundžia Reference Stundžia2014b: 12–16; Rinkevičius Reference Rinkevičius2015: 79–83; see also Saussure 2012a [Reference Saussure, Umberto Dini and Stundžia1922]: 47–72, Reference Saussure, Umberto Dini and Stundžia2012b [1922]: 73–87).

The prosodic features of the pitch accent are concentrated in the sonorant portion of the syllable rime, i.e. the vowel, diphthong or VR-type diphthongoid sequence, if present. Experimental research has established that Lithuanian accents are differentiated by a whole complex of prosodic features – the features of pitch, intensity, duration and quality, and the significance of their combinations depends to a great extent on the structure of the stressed long syllable. Hence, Lithuanian pitch accents have several allotones.

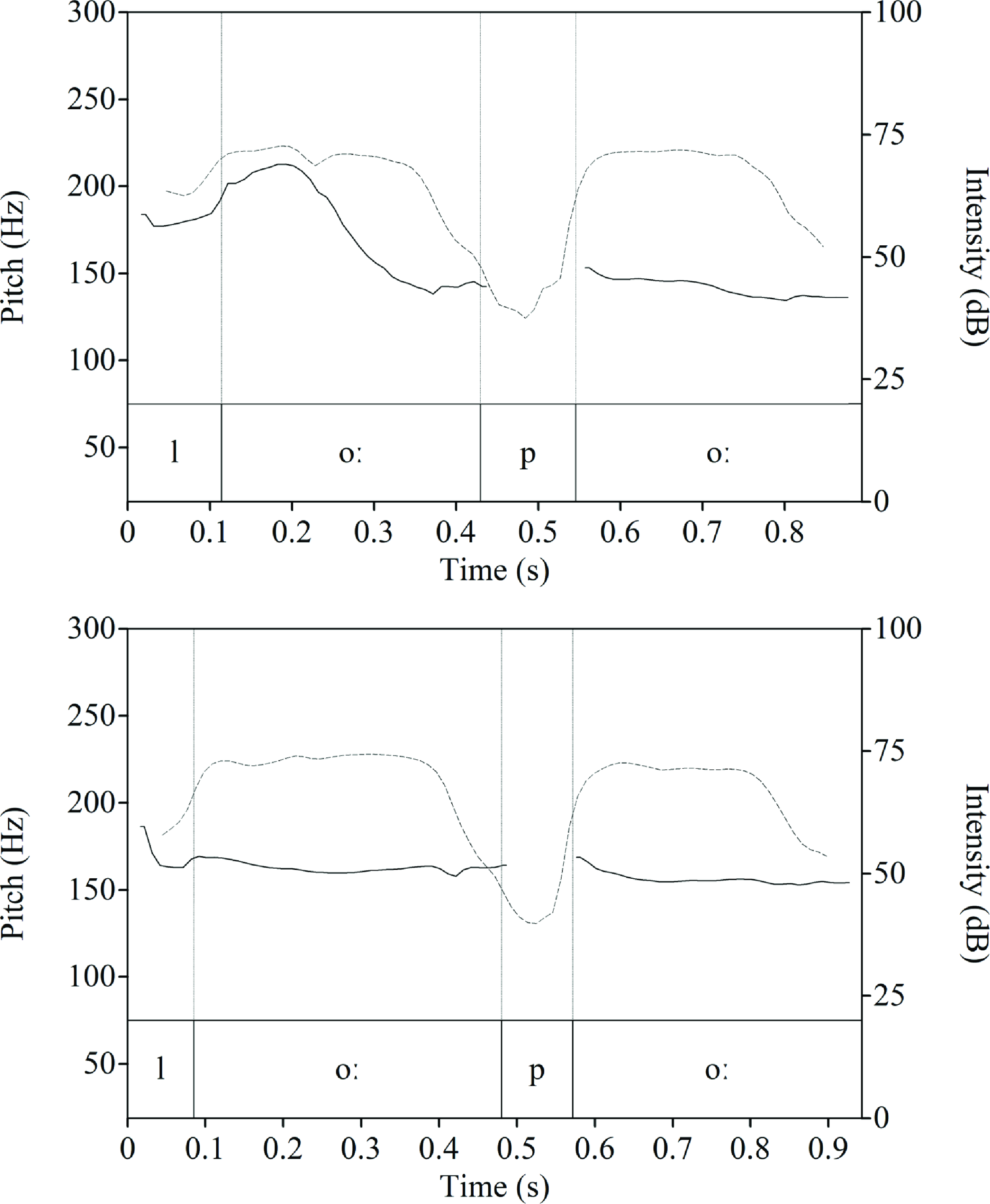

Accents of syllables whose nucleus consists of long non-gliding (uniform) and gliding (non-uniform) vowels differ in terms of f0 characteristics and duration, and characteristics of intensity and vowel quality are less significant (see Figures 10 and 11, and Table 7), e.g. lópo [1ˈloːpoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) patch(es)’ : lõpo [2ˈloːpoː] ‘patch’ (gen.sg), skýrei [1ˈsʲkʲiːrʲɛɪ] ‘(you) devoted’ (sg) : skỹriai [2ˈsʲkʲiːrʲɛɪ] ‘chapters; sections’, palíesiu [pʌ1ˈlʲiɛsʲʊ̟] ‘(I) shall spill’ : paliẽsiu [pʌ2ˈlʲiɛsʲʊ̟] ‘(I) shall touch’.

Figure 10 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of acute and circumflex long monophthongs in Lithuanian [1ˈloːpoː] (top panel) vs. [2ˈloːpoː] (bottom panel) (female data).

Figure 11 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of acute and circumflex long monophthongs in Lithuanian [1ˈsʲkʲiːrʲ┋ɪ] (top panel) vs. [2ˈsʲkʲiːrʲ┋ɪ] (bottom panel) (female data).

Table 7 Prosodic features of Lithuanian acute and circumflex vowels, diphthongs and VR-type diphthongoid sequences (female data).

According to earlier research, the vowels in circumflex syllables of Standard Lithuanian are longer than the acute ones by a ratio of approximately 1.12 : 1. The average f0 level of the circumflex syllables is slightly higher than that of the acute ones; the difference in peak f0 is not significant. The intensity indices are even less reliable in differentiating the pitch accents; circumflex vowels are usually several tenths of a decibel more intense than acute ones (Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 157, 175, 178).

In syllables containing diphthongs and VR-type diphthongoid sequences with the first elements [ɐˑ/ʌæˑ/ɛ], accents are most clearly differentiated by the quantitative (when accentuated, they are prolonged to half-long ones) and qualitative features of the elements (the first components of acute diphthongs are much more compact); however, the f0 is also a significant feature (see Figures 12 and 13, and Table 7), e.g. šáuk [1ˈʃɐˑʊk] ‘(you) shoot’ (imperative, sg) : šaũk [2ˈʃɒʊˑk] ‘(you) shout’ (imperative, sg), láido [1ˈlɐˑɪdoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) is/are hurling; flinging’ : laĩdo [2ˈlʌɪˑdoː] ‘wire’ (gen.sg), kártas [1ˈkɐˑrtʌs] ‘hung’ : kar˜tas [2ˈkʌrˑtʌs] ‘time’, vérsiu [1ˈʋʲæˑrʲsʲʊ̟] ‘(I) shall put through; string’ : ver˜siu [2ˈʋʲɛrʲˑsʲʊ̟] ‘(I) shall throw down; turn over; make; translate’.

Figure 12 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of acute and circumflex diphthongs with [ɐˑ/ɒ] in Lithuanian [1ˈ₃ɐˑʊk] (top panel) vs. [2ˈ₃ɒʊˑk] (bottom panel) (female data).

Figure 13 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of acute and circumflex VR-type diphthongoid sequences with [æˑ/┋] in Lithuanian [1ˈʋʲæˑrʲsʲʊ̟] (top panel) vs. [2ˈʋʲ┋rʲˑsʲʊ̟] (bottom panel) (female data).

According to previous studies, the first components [ɐˑ/ʌ æˑ/ɛ] of the acute diphthongs are on average 1.52 times longer than the corresponding circumflex diphthongs and 1.35 times longer than the corresponding short stressed vowels, but significantly shorter than the corresponding acute long vowels; therefore, they are to be considered half-long ones. The second components of the circumflex diphthongs are on average 1.39 times longer than the corresponding components of acute diphthongs, so they lengthen slightly less due to the effect of the pich accent. Qualitative features of the components are also important. It was established that the components [ɐˑ/ʌæˑ/ɛ] of acute diphthongs are more compact and more peripheral in the vowel space than the circumflex; the spectral structure of the corresponding sonorants is also unequal. The parameters of the f0 and intensity are to be considered only as ancillary features in the differentiation of pitch acents (Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 160, 181).

In those syllables where the nucleus consists of VR-type diphthongoid sequences with the components [ɪ ʊ], accents are differentiated by means of pitch features. Their first components, even if emphasized, do not become half-long but remain short (see Figures 14 and 15, and Table 7), e.g. kùrtas [1ˈkʊrtʌs] ‘created’ : kur˜tas [2ˈkʊrˑtʌs] ‘deaf’, vìrto [1ˈʋʲɪrtoː] ‘boiled’ (past part.gen.sg.m) : vir˜to [2ˈʋʲɪrˑtoː] ‘(s/he, it, they) turned into’ (for more about it see Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 156–182; Reference Pakerys2003: 220–221; LG Reference Ambrazas2006: 56; Bakšienė Reference Bakšienė2016: 46–50).

Figure 14 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of acute and circumflex VR-type diphthongoid sequences with [ɪ] in Lithuanian [1ˈʋʲɪrtoː] (top panel) vs. [2ˈʋʲɪrˑtoː] (bottom panel) (female data).

Figure 15 Pitch (solid line) and intensity (dashed line) traces of acute and circumflex VR-type diphthongoid sequences with [ʊ] in Lithuanian [1ˈkʊrtʌs] (top panel) vs. [2ˈkʊrˑtʌs] (bottom panel) (female data).

According to previous studies, the components [ɪ ʊ] for acute diphthongs are only 1.06 times longer than the corresponding short vowels. The ratio of the respective acute and circumflex components [ɪ ʊ] is 1.16 : 1; therefore, the lengthening of the acute components [ɪ ʊ] is insignificant. The lengthening of the circumflex diphthongs’ second components in this group is similar to those discussed previously – they are approximately 1.3 times longer than the corresponding acute diphthongs’ second components. The pitch and intensity parameters of the acute diphthongs are usually lower than those of the corresponding circumflexes (Pakerys Reference Pakerys1982: 160, 175, 178).

Transcription of the recorded passage

Orthographic version

Vieną dieną, Šiaurės vėjui ir Saulei besiginčijant, kuris iš jų stipresnis, pasirodė keliautojas, vilkintis apsiaustu. Šiaurys ir Saulė susitarė, kad stipresniu bus laikomas tas, kuris privers keliautoją nusimesti apsiaustą. Šiaurys pūtė taip stipriai, kaip tik pajėgė. Bet kuo stipriau jisai pūtė, tuo tvirčiau keliautojas gaubdavosi apsiaustą. Galiausiai Šiaurys pasidavė. Tada Saulė pradėjo kaitinti, ir keliautojas tuoj pat nusivilko apsiaustą. Tad Šiaurys turėjo pripažinti, kad Saulė stipresnė už jį.

Acknowledgements

We thank for Maria Tabain, Matthew Gordon and anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and insights.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100323000105.