INTRODUCTION

Providing leadership in emergency medicine is a challenging proposition at the best of times. Under the pandemic context imposed by the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), the intensity of these roles is magnified with added responsibilities and the need for extra focus and vigilance. Taking a simplistic perspective, there are two general outcomes we can expect from emergency department (ED) pandemic leadership efforts.

At one extreme, your entire staff will feel supported, informed, and resolutely poised to manage the current and future challenges of working in an ED during a pandemic. A recent paper noted that, in a pandemic, “there is a particular demand for leaders who represent and advance the shared interests of group members and create . . . a sense that we are all in this together.”Reference Van Bavel, Boggio and Capraro1

At the other extreme, staff may feel that they are being exposed to undue risk, that messaging around pandemic operational changes is inconsistent and or unclear, and that there is a lack of trust in the leadership team's ability to see the department through this storm largely unscathed.

Good leadership can foster a more effective and consistent response to a pandemic; build confidence and courage among staff; and strengthen their resilience in the face of doubt, fear, and the inevitable bad outcomes among patients (and potentially colleagues) whom they will encounter. Poor leadership will not only reduce the effectiveness of frontline staff, but also it may weaken their ability to cope with bad outcomes and create a downward spiral of declining morale and effectiveness. Beyond the actions or pronouncements of a single individual or department chief, strong leadership should be visible and coherently expressed at all levels of an ED; this includes catalysing and encouraging good decision-making by frontline staff in the hundreds of interactions that occur in any given shift. This invited commentary will focus on key strategies that this author group believes are of primary importance in achieving a positive outcome during the COVID-19 pandemic.

ESTABLISH STAFF SAFETY AS A TOP PRIORITY

While emergency medicine leaders are being asked to fulfill myriad roles during the COVID-19 pandemic, their most important task is to fiercely protect the safety and well-being of their staff. This is true in terms of both preventing inadvertent infection and supporting their psychological well-being in a time of high anxiety and distress where frontline providers are clearly subject to increased risk.

Focusing on workplace health and safety means paying attention to personal protective equipment preservation strategies and workflow redesign to limit COVID-19 to as narrow a corridor of service as possible. This requires close collaboration with colleagues in infection prevention and control to develop nimble and safe approaches that reflect the unique features of COVID-19 in mitigating risk for physicians and nurses. This includes carefully protecting ward stock and monitoring for the inappropriate use of personal protective equipment.

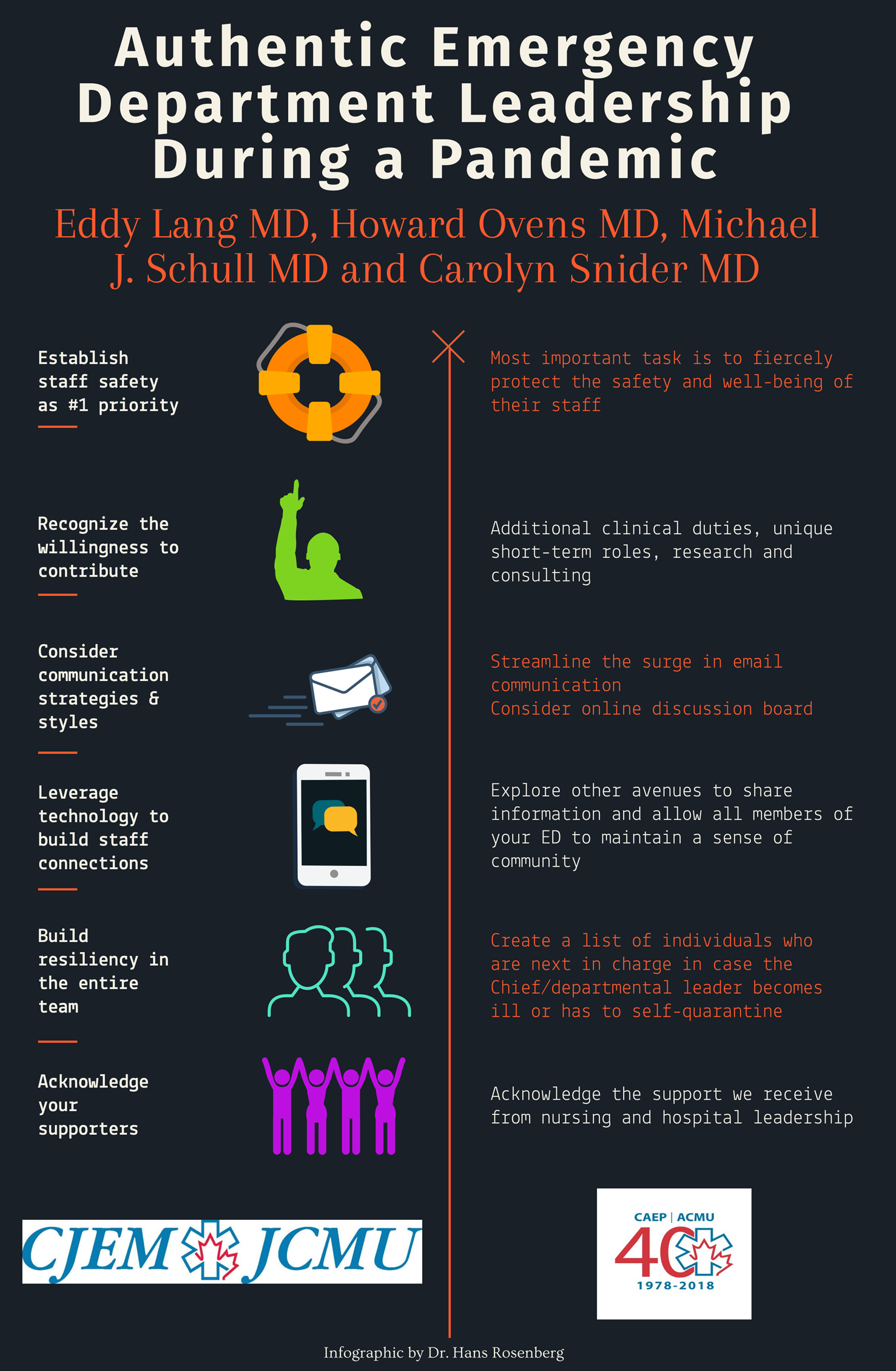

Figure 1. Authentic emergency department leadership during a pandemic.

It is important to balance the delivery of one-way communication of ever-changing, hospital-wide directives and protocols on personal protective equipment use with opportunities for staff to express their concerns and ideas about the best ways to remain safe. On-shift in situ simulations allow entire teams to build confidence in their ability to perform anticipated high-risk procedures and can be used for excellent team-building exercises. In terms of psychological well-being, physicians with either expertise in or a predilection for wellness and wellness activities need to be engaged and put to work. Support is needed for those who are unable to work due to self-isolation or illness and for those who are working but are experiencing the duress of school closures and other challenges imposed by states of emergency. Providing meals, babysitting, moral support, and connection are low-hanging fruit in this regard. When organizing regular staff meetings (using virtual means as needed), offering ample time for staff to express their ideas, discuss difficult cases, and vent can help improve communication, maintain morale, and ensure that staff are being heard.

RECOGNIZE THE WILLINGNESS TO CONTRIBUTE

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought out some of the best and worst in people in general (e.g., neighbours helping neighbours and outrageous price gouging, respectively). In the ED context, our observation is that it has largely brought out the best. In our current leadership roles, we have seen staff willing to take on additional non-clinical responsibilities when help is sought and the spontaneous offering of time and effort for whatever may be needed in terms of the COVID-19 response. With ED volumes generally reduced, this can be a key opportunity to have doctors who are not consumed with clinical duties to take on unique short-term roles.

For example, physician volunteers could undertake research on personal protective equipment preservation strategies. ED physicians may be uniquely poised to fill consulting roles with local clinics that serve vulnerable populations to help them develop their COVID-19 plans. The primary barrier to recruiting volunteers is often a reluctance to ask people to contribute. Emergency care providers are inherently generous and resourceful, and if a task is required to facilitate your department's COVID-19 response, you need only ask, and someone will come forth in these challenging times.

Better decisions can be made by rapidly crowd-sourcing ideas from staff. But the flip side is equally important; once a decision is made, all members of the team need to accept it and help implement it, even if they initially did not support it. There can be minimal tolerance for steadfast beliefs in physician autonomy at a time when staff and patient safety rely on everyone playing by the same rules.

CONSIDER COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES AND STYLES

As ED leaders, we must be aware that everyone is watching us to gauge our reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is critically important to monitor tone, attitude, and what information is communicated while remaining authentic. A good leader should never lie and should be as transparent as possible, but that does not mean always telling everyone everything. It is a time for optimism. Let your team know about all the good work that's being done to protect the ED and control the pandemic. In many jurisdictions, the establishment of off-site COVID-19 assessment and testing centres, as well as greatly ramped up nurse-managed health information telephone lines have helped minimize what certainly would have been a flood of low-acuity suspected COVID-19 infected patients in the ED.

We also recommend streamlining the surge in email-based information that can come at your team during these trying times. These threads that often lack context can be overwhelming and lead to out-of-control anxiety. Consider using an online discussion board (e.g., Slack) with various topics to foster conversation. Additionally, a daily virtual check-in will provide opportunities for the more nuanced conversations that email cannot accommodate. While “truth” can be elusive amid the fog of a pandemic, having a single and consistent source of accurate local information in the rapidly changing landscape of policies and procedures, developed specifically for the COVID-19 response, is essential.

LEVERAGE TECHNOLOGY TO BUILD STAFF CONNECTIONS

Physical distancing measures can detract from an ED's sense of community. With departmental rounds and meetings cancelled or severely curtailed as a result of COVID-19, explore other avenues to share information and allow the members of your ED, including nurses, to maintain a sense of community and understand where the leadership team is at in their appraisal of and planning for the COVID-19 response. Online platforms can readily replace academic half days or ED grand rounds, or they can be used to host special COVID-19-oriented town halls. Panelists and presenters can cover key topics, such as airway management and the donning/doffing of personal protective equipment, through live and archived videos. These sessions can generate a great deal of positive feedback from physicians and nurses and contribute to feelings of reassurance.

BUILD RESILIENCY IN THE ENTIRE TEAM

Distributed leadership is an important part of resiliency. This is demonstrated throughout a department at every level, ranging from sensible, evidence-informed, and well-considered policies that are established (and revised as circumstances change) to decisions that staff make on the fly about resource distribution during a tough shift.

Redundancy is another key aspect of resiliency. Create a list of individuals who are next in charge in case the Chief or another departmental leader becomes ill or has to self-quarantine. Ensure that those people know they are next on the list and are reasonably briefed and ready to take over should the need arise. Enable interactions across departments that are working closely with the ED in the pandemic response, such as admitting teams, intensive care, anesthesia, and medical imaging among others, because the decisions of one department will likely affect others’.

It is also crucial that leaders take care of themselves; many have noted that this pandemic is a marathon, not a sprint. To lead well consistently we must tend to our own needs for rest, exercise, and nutrition and maintain family and social connections, even if done collectively (such as a social media post or an email update to a group of people who are likely worried about you). Collaborate and share experiences and feelings with trusted peers. To stay positive and engaged, we need a deep sense of purpose and to find meaning in our roles and pride in our response.Reference Brooks2

Dr. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and Holocaust survivor, wrote in his memoir, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of human freedoms — to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way.”Reference Frankl3 How we carry ourselves as leaders during this crisis is one thing within our control.

ACKNOWLEDGE YOUR SUPPORTERS

The response to COVID-19 would not be possible without the countless hours of intense dedication from our leadership teams. It is essential that we acknowledge the support we receive from nursing and hospital leadership and the tremendous sacrifices involved.

INTRODUCTION

Providing leadership in emergency medicine is a challenging proposition at the best of times. Under the pandemic context imposed by the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), the intensity of these roles is magnified with added responsibilities and the need for extra focus and vigilance. Taking a simplistic perspective, there are two general outcomes we can expect from emergency department (ED) pandemic leadership efforts.

At one extreme, your entire staff will feel supported, informed, and resolutely poised to manage the current and future challenges of working in an ED during a pandemic. A recent paper noted that, in a pandemic, “there is a particular demand for leaders who represent and advance the shared interests of group members and create . . . a sense that we are all in this together.”Reference Van Bavel, Boggio and Capraro1

At the other extreme, staff may feel that they are being exposed to undue risk, that messaging around pandemic operational changes is inconsistent and or unclear, and that there is a lack of trust in the leadership team's ability to see the department through this storm largely unscathed.

Good leadership can foster a more effective and consistent response to a pandemic; build confidence and courage among staff; and strengthen their resilience in the face of doubt, fear, and the inevitable bad outcomes among patients (and potentially colleagues) whom they will encounter. Poor leadership will not only reduce the effectiveness of frontline staff, but also it may weaken their ability to cope with bad outcomes and create a downward spiral of declining morale and effectiveness. Beyond the actions or pronouncements of a single individual or department chief, strong leadership should be visible and coherently expressed at all levels of an ED; this includes catalysing and encouraging good decision-making by frontline staff in the hundreds of interactions that occur in any given shift. This invited commentary will focus on key strategies that this author group believes are of primary importance in achieving a positive outcome during the COVID-19 pandemic.

ESTABLISH STAFF SAFETY AS A TOP PRIORITY

While emergency medicine leaders are being asked to fulfill myriad roles during the COVID-19 pandemic, their most important task is to fiercely protect the safety and well-being of their staff. This is true in terms of both preventing inadvertent infection and supporting their psychological well-being in a time of high anxiety and distress where frontline providers are clearly subject to increased risk.

Focusing on workplace health and safety means paying attention to personal protective equipment preservation strategies and workflow redesign to limit COVID-19 to as narrow a corridor of service as possible. This requires close collaboration with colleagues in infection prevention and control to develop nimble and safe approaches that reflect the unique features of COVID-19 in mitigating risk for physicians and nurses. This includes carefully protecting ward stock and monitoring for the inappropriate use of personal protective equipment.

Figure 1. Authentic emergency department leadership during a pandemic.

It is important to balance the delivery of one-way communication of ever-changing, hospital-wide directives and protocols on personal protective equipment use with opportunities for staff to express their concerns and ideas about the best ways to remain safe. On-shift in situ simulations allow entire teams to build confidence in their ability to perform anticipated high-risk procedures and can be used for excellent team-building exercises. In terms of psychological well-being, physicians with either expertise in or a predilection for wellness and wellness activities need to be engaged and put to work. Support is needed for those who are unable to work due to self-isolation or illness and for those who are working but are experiencing the duress of school closures and other challenges imposed by states of emergency. Providing meals, babysitting, moral support, and connection are low-hanging fruit in this regard. When organizing regular staff meetings (using virtual means as needed), offering ample time for staff to express their ideas, discuss difficult cases, and vent can help improve communication, maintain morale, and ensure that staff are being heard.

RECOGNIZE THE WILLINGNESS TO CONTRIBUTE

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought out some of the best and worst in people in general (e.g., neighbours helping neighbours and outrageous price gouging, respectively). In the ED context, our observation is that it has largely brought out the best. In our current leadership roles, we have seen staff willing to take on additional non-clinical responsibilities when help is sought and the spontaneous offering of time and effort for whatever may be needed in terms of the COVID-19 response. With ED volumes generally reduced, this can be a key opportunity to have doctors who are not consumed with clinical duties to take on unique short-term roles.

For example, physician volunteers could undertake research on personal protective equipment preservation strategies. ED physicians may be uniquely poised to fill consulting roles with local clinics that serve vulnerable populations to help them develop their COVID-19 plans. The primary barrier to recruiting volunteers is often a reluctance to ask people to contribute. Emergency care providers are inherently generous and resourceful, and if a task is required to facilitate your department's COVID-19 response, you need only ask, and someone will come forth in these challenging times.

Better decisions can be made by rapidly crowd-sourcing ideas from staff. But the flip side is equally important; once a decision is made, all members of the team need to accept it and help implement it, even if they initially did not support it. There can be minimal tolerance for steadfast beliefs in physician autonomy at a time when staff and patient safety rely on everyone playing by the same rules.

CONSIDER COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES AND STYLES

As ED leaders, we must be aware that everyone is watching us to gauge our reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is critically important to monitor tone, attitude, and what information is communicated while remaining authentic. A good leader should never lie and should be as transparent as possible, but that does not mean always telling everyone everything. It is a time for optimism. Let your team know about all the good work that's being done to protect the ED and control the pandemic. In many jurisdictions, the establishment of off-site COVID-19 assessment and testing centres, as well as greatly ramped up nurse-managed health information telephone lines have helped minimize what certainly would have been a flood of low-acuity suspected COVID-19 infected patients in the ED.

We also recommend streamlining the surge in email-based information that can come at your team during these trying times. These threads that often lack context can be overwhelming and lead to out-of-control anxiety. Consider using an online discussion board (e.g., Slack) with various topics to foster conversation. Additionally, a daily virtual check-in will provide opportunities for the more nuanced conversations that email cannot accommodate. While “truth” can be elusive amid the fog of a pandemic, having a single and consistent source of accurate local information in the rapidly changing landscape of policies and procedures, developed specifically for the COVID-19 response, is essential.

LEVERAGE TECHNOLOGY TO BUILD STAFF CONNECTIONS

Physical distancing measures can detract from an ED's sense of community. With departmental rounds and meetings cancelled or severely curtailed as a result of COVID-19, explore other avenues to share information and allow the members of your ED, including nurses, to maintain a sense of community and understand where the leadership team is at in their appraisal of and planning for the COVID-19 response. Online platforms can readily replace academic half days or ED grand rounds, or they can be used to host special COVID-19-oriented town halls. Panelists and presenters can cover key topics, such as airway management and the donning/doffing of personal protective equipment, through live and archived videos. These sessions can generate a great deal of positive feedback from physicians and nurses and contribute to feelings of reassurance.

BUILD RESILIENCY IN THE ENTIRE TEAM

Distributed leadership is an important part of resiliency. This is demonstrated throughout a department at every level, ranging from sensible, evidence-informed, and well-considered policies that are established (and revised as circumstances change) to decisions that staff make on the fly about resource distribution during a tough shift.

Redundancy is another key aspect of resiliency. Create a list of individuals who are next in charge in case the Chief or another departmental leader becomes ill or has to self-quarantine. Ensure that those people know they are next on the list and are reasonably briefed and ready to take over should the need arise. Enable interactions across departments that are working closely with the ED in the pandemic response, such as admitting teams, intensive care, anesthesia, and medical imaging among others, because the decisions of one department will likely affect others’.

It is also crucial that leaders take care of themselves; many have noted that this pandemic is a marathon, not a sprint. To lead well consistently we must tend to our own needs for rest, exercise, and nutrition and maintain family and social connections, even if done collectively (such as a social media post or an email update to a group of people who are likely worried about you). Collaborate and share experiences and feelings with trusted peers. To stay positive and engaged, we need a deep sense of purpose and to find meaning in our roles and pride in our response.Reference Brooks2

Dr. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and Holocaust survivor, wrote in his memoir, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of human freedoms — to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way.”Reference Frankl3 How we carry ourselves as leaders during this crisis is one thing within our control.

ACKNOWLEDGE YOUR SUPPORTERS

The response to COVID-19 would not be possible without the countless hours of intense dedication from our leadership teams. It is essential that we acknowledge the support we receive from nursing and hospital leadership and the tremendous sacrifices involved.

Competing interests

None declared.