It is commonly presumed that unilateral action is easier to reverse than legislation. While it may be difficult for Congress to overturn an executive order on its own, a new president who opposes it may seem sufficient. Given this, Thrower (Reference Thrower2017) calls unilateral policies “transitory” instruments that “future regimes can easily change…, particularly presidents who can act independently from other political actors through unilateral action.” She points to Warber (Reference Warber2006), who describes the many ways that a president can nullify previous orders. Political commentators express a similar sentiment, describing executive orders as “swift, powerful, and easily reversed” (Madhani, Reference Madhani2021). Following this, Turner (Reference Turner2020) studies how lower durability of executive orders affects bureaucratic investment in policymaking. And I study a model in which unilateral policy may be undone unilaterally, but legislative policy may only be undone legislatively (Foster, Reference Foster2022).

Illustrating this phenomenon, the so-called “Mexico City policy” is a classic example of easily reversed unilateral policy. First issued by Ronald Reagan in 1985, the policy prohibits non-governmental organizations that facilitate or advocate abortion access from receiving US federal funding. Subsequently, the policy has ping-ponged back and forth in lockstep with the partisanship of the presidential administration, being rescinded under Democratic administrations and reissued under Republican administrations. Thus, in contrast with most legislation, this unilateral policy has been subject to the ever-changing whims of whomever holds office at a given moment.

But not all unilateral policies neatly follow this template. Consider the Obama Administration's policy of declining to enforce federal drug laws against states and individuals facilitating cannabis markets. Though Obama had the opportunity to use the power of the federal government to crush these nascent state-level markets, his administration issued memos specifically directing federal law enforcement not to spend resources enforcing federal law in these cases.Footnote 1 When an opposed administration took power years later, it was too late. Despite Attorney General Jeff Sessions's well-known opposition to cannabis legalization and his formal rescission of these memos in January 2018 (U.S. Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, 2018), actual DOJ enforcement against state-legalized practices had not evidently resumed under President Trump as of January 2020 (Firestone, Reference Firestone2020).Footnote 2

Why then do some unilateral policies follow the template of the Mexico City policy, while others manage to survive subsequent opposed administrations? It is first necessary to establish a theory of policy persistence that does not rely on differences in legal constraints between legislation and unilateralism, which cannot explain persistent unilateralism. In particular, I argue for a selection effect, by which the mode of policymaking employed is a function of the power of outside constituents demanding policy change. When outside interests are weak, they may first receive unilateral policy as a consolation. Then because of their initial weakness—not the fact that policy was unilateral—they may later fail to defend that policy against an opposed future president. When outside interests are strong, they can successfully pressure Congress to produce legislation. Then because of their initial strength—not the fact that policy was legislative—they are later able to use these resources to perpetuate prior policy achievements. As a consequence, there may be an association between unilateralism and policy reversal, even if legislation were to confer no inherent irreversibility.Footnote 3

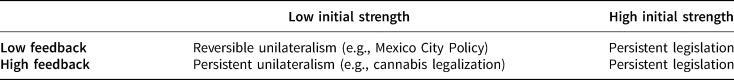

What about those cases in which unilateral action persists? Here, the lack of legal constraints on reversing unilateral policy only deepens the puzzle. Yet a president with legal power to overturn executive orders may nevertheless lack political power. In particular, I argue for the role of policy feedback effects in allowing policy-demanding groups to gain strength and fight more effectively to perpetuate even unilateral policy. Although a group may initially be weak and need to rely on unilateral policy, the fact of the policy's issuance may increase the group's power in the future, allowing it to resist reversal by a future opposed president and Congress. While policy shifts in some issues such as abortion may fail to translate into enduring realignments in group power, others such as cannabis legalization may do exactly that. This is summarized in Table 1. The case of federal cannabis policy, presented below, shows that strong policy feedback effects can make unilateral policy as resilient as legislation. This reflects the importance of interest group power in influencing whether policy persists, distinct from the formal legal authority assigned to different modes of policymaking.

Table 1. Persistence and mode of policymaking given the initial strength of the group demanding policy change and the size of policy feedback effects

This has important normative implications, as significant unilateral action has increased sharply in recent decades (Kaufman and Rogowski, Reference Kaufman and Rogowski2024b). While this provokes concerns about constitutionality and executive branch aggrandizement (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Shepsle and Wolton2023), it can be seen as responsive to voters as long as new presidents have a free hand to reverse the orders of predecessors. But when executive orders stick despite a successor's opposition, unilateralism constitutes yet another domain in which policy outcomes may be insulated from popular accountability (Lowande and Poznansky, Reference Lowande and Poznansky2024). To be sure, the normative valence of persistent unilateral action depends on the specific mechanism of policy feedback. It could be good if persistence is due to the public learning about the relationship between policy and their preferences. On the other hand, it could be concerning if persistence is due to interest groups using increased resources to manipulate or circumvent public opinion.

I proceed as follows. First, I relate my argument to the literature. Second, I formalize my argument with a model. Third, I discuss robustness. Fourth, I briefly relate the model to the empirical literature. Fifth, I present the case of cannabis policy under Presidents Obama and Trump. Finally, the paper concludes.

1. Related literature

1.1 Executive order issuance

A rich literature has examined the circumstances under which executive orders are enacted. Moe and Howell (Reference Moe and Howell1999) argue that the president takes advantage of divisions within Congress to enact policy unilaterally, forcing other actors to respond only after the fact. Establishing scope conditions on this observation, Howell (Reference Howell2003) extends the pivotal politics framework of Krehbiel (Reference Krehbiel1998) to understand how the pursuit of unilateral action is predicted by the position of the status quo, the location of gridlock players in Congress, and the level of discretion afforded to the president. Subsequently, Chiou and Rothenberg (Reference Chiou and Rothenberg2017) extend Howell's modeling framework and employ sophisticated quantitative methodologies to understand how the president anticipates the objections of pivotal members of Congress in issuing significant executive orders. The present paper differs from this work in its focus not on divisions within Congress but rather on the influence of interest groups on policy preferences and how this conditions the mode of policymaking that occurs.

Complementing Chiou and Rothenberg, Bolton and Thrower (Reference Bolton and Thrower2016) and Barber et al. (Reference Barber, Bolton and Thrower.2019) examine the role that legislative capacity plays in constraining unilateral action. They show that unilateralism is more constrained when legislatures have high capacity and many ways of sanctioning the executive. They also argue that executive order issuance decreases on average during divided government. However, other work argues that executive orders increase under divided government (Kaufman and Rogowski, Reference Kaufman and Rogowski2024a). Indeed, the president may alternatingly act as an administrator in support of Congress and an independent actor in conflict with Congress (Belco and Rottinghaus, Reference Belco and Rottinghaus2017). Even if some orders are issued to support an agreeable Congress, case evidence clearly points to specific instances in which the president used unilateral action to evade a recalcitrant Congress (Foster, Reference Foster2022). While acknowledging a diversity of motivations for executive order issuance, I extend my prior focus on evasive orders.

Rudalevige (Reference Rudalevige2021) is another notable study of constraints within government, examining how divisions within the executive branch and bureaucratic disagreements with the president can hold back executive orders. The present paper abstracts away from this, focusing instead on constraints outside government. This follows a growing volume of work that has studied forces outside government as a key explanatory factor in executive order production. Notably, Reeves and Rogowski (Reference Reeves and Rogowski2016), Christenson and Kriner (Reference Christenson and Kriner2017a), Christenson and Kriner (Reference Christenson and Kriner2017b), Lowande and Gray (Reference Lowande and Gray2017), and Reeves and Rogowski (Reference Reeves and Rogowski2018) demonstrate that negative public opinion may constrain the president from issuing an order. While I focus on interest groups, one possible channel of their influence is public opinion (Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman2001; Sobbrio, Reference Sobbrio2011).

In Foster (Reference Foster2022), I also examine constraints outside government, arguing that policy disagreements within Congress cannot explain failure to legislate when that failure induces a substitute executive order; I thus look to interest groups as blocking legislation and thus inducing unilateral action. Similarly, the present paper considers their actions while additionally examining the role of policy feedback effects in influencing executive order issuance and persistence.

1.2 Executive order persistence

This paper relates closely to work on executive order persistence. Thrower (Reference Thrower2017) and Thrower (Reference Thrower2023) explore the determinants of persistence. Broadly, she shows that the issuing president's political costs, alignment of the issuing president with Congress, alignment of the issuing and current president, and strength of statutory authority are important factors in predicting executive order rescissions and alterations. The current paper complements this work, exploring how interest group politics can influence orders’ persistence. In particular, I explore how these strategic outside actors influence the mode of policymaking (unilateral or legislative) as well as its persistence. Thus, in contrast with Thrower, I explicitly consider the possibility that actors could have pursued legislation as an alternative means of achieving their policy goals.

Notably, Thrower shows that executive orders enacted under divided government are more likely to persist. She argues that the president may have moderated such orders to avoid provoking a hostile Congress at the time, ensuring less opposition and greater durability later. The present model's logic does not preclude this story, but it implies an additional explanation for this empirical pattern, which I discuss below.

Another related paper is Lowande and Poznansky (Reference Lowande and Poznansky2024). The authors study cases in which practical and physical considerations make executive order reversal difficult, such as orders that release nonrecoverable assets. By contrast, the present paper does not focus on cases of practical irreversibility but rather examines the role of positive policy feedback effects in reshaping the landscape of interest group power.

1.3 Policy feedback and persistence

A considerable literature examines positive policy feedback, by which policy gains translate to political power and reinforce or further those gains (Pierson, Reference Pierson1993, Reference Pierson1996; Soss and Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007; Mettler and SoRelle, Reference Mettler and SoRelle.2018; Larsen, Reference Larsen2019). Particularly worth discussing here is the formal theoretic literature focused on policy feedback and persistence. Coate and Morris (Reference Coate and Morris1999) argue that a firm may bribe a politician to preserve a policy benefiting its industry because it may be costly for the firm to switch industries. This could lead to policy persisting only because it is already in place, not because it is optimal for voters. Callander et al. (Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2022) show that a politician may grant regulatory protection to one firm over another in order to reap a share of the monopoly profits. Finally, Callander et al. (Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2023) study how pro-competitive policy may be reversed over time by firms bribing bureaucrats to allow anti-competitive mergers. These models and arguments provide important underpinnings for some of the ways in which policy success and market power can translate into a feedback loop of amplifying political power as well as identifying the scope conditions on this loop. In the present work, I incorporate positive policy feedback in a reduced-form manner while placing primary focus on the implications of the mode of policymaking (either legislation or unilateralism) for policy persistence.

1.4 Policy feedback and cannabis

In a closely related analysis focusing specifically on cannabis policy, Trachtman (Reference Trachtman2023) examines the role that state legalization played in shifting the behavior of members of Congress. Using a variety of quantitative methods, Trachtman argues that state legalization led its members to take more pro-cannabis stances in Congress. He presents evidence that legalization empowered pro-legalization interest groups in such states to pressure members. The present paper complements this perspective, examining the role that the president plays in facilitating (or crushing) the opportunity provided to these interest groups. Although state-level industries eventually grew and shifted members’ behavior, I note in the case study that many expected the president to enforce federal law against these state legalization efforts, well before state industries had an opportunity to become entrenched. It was only through the active choice of DOJ officials to throttle enforcement that policy feedback effects were able to realize.

2. The model

The key feature of the model is that in a first stage, a left-leaning group must rely on the president's unilateral powers when weak, while it can effectively push for legislation when strong. Whether the policy change persists later is a function of this very level of strength rather than the mode of policymaking itself, which nevertheless induces an association between legislation and policy persistence. But this association can be broken by large policy feedback effects, such that even unilateral action can prove to be persistent. This happens if the implementation of the unilateral policy itself increases the left-leaning group's resources in a second stage, making it more effective at pressuring politicians and preventing reversal.

2.1 Formal definition

Players consist of a median member of Congress C, a first-stage president P 1, a second-stage president P 2, a left-leaning interest group L, and a right-leaning interest group R. They interact to determine policy $x_t \in {\opf R}$![]() in Stage t, with t ∈ {1, 2}.

in Stage t, with t ∈ {1, 2}.

I normalize the initial status quo x 0 to zero. In Stage t, each group I's budget $B_t^I$![]() is a function of x t−1; these resources can be used to influence other players’ ideal points and induce a different policy outcome. Ultimately, the influence of L and R affects both the location of policy selected by C and P t as well as the mode used to enact it (legislation or unilateral action) in Stage 1.

is a function of x t−1; these resources can be used to influence other players’ ideal points and induce a different policy outcome. Ultimately, the influence of L and R affects both the location of policy selected by C and P t as well as the mode used to enact it (legislation or unilateral action) in Stage 1.

2.1.1 Utility functions

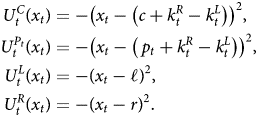

Players are assumed to be myopic. That is, they look forward to the consequences of their actions within each stage but do not consider the implications for the second stage when they are in the first. In other words, they are assumed to live for a single stage.Footnote 4 Utility in Stage t is as follows:

Here, j ∈ {c, p t, ℓ, r} is the initial ideal point of J ∈ {C, P t, L, R}, respectively, and $k_t^I \in [ 0,\; B^I_t]$![]() is resources spent by I ∈ {L, R} to influence the effective ideal points of C and P t.

is resources spent by I ∈ {L, R} to influence the effective ideal points of C and P t.

2.1.2 Sequence of moves

The sequence of moves is as follows:

Stage 1

1. The groups simultaneously choose how much influence to exert on C and P 1.

2. C decides whether to pass legislation.

3. P 1 decides whether to sign legislation.

4. If legislation failed, P 1 decides whether to take unilateral action.

5. Stage payoffs are realized.

Stage 2

6. Stage 1 repeats, with P 2 in office and the status quo inherited from the outcome of policymaking in Stage 1.

7. The game ends.

2.1.3 Assumptions

First, I assume that while legislation is unconstrained in its ability to move policy, unilateral action is constrained not to move it too far from the status quo:

Assumption 1 (Presidential discretion bound): Unilateral action can only be used to induce x t ∈ [ − d, d] for some d > 0.

That is to say, there is a discretion bound: unilateral action can only move policy so far from the initial status quo (at zero), specifically a distance d. This is a common assumption in the literature (Howell, Reference Howell2003) that is well-supported by substance; without it, legislation would never have an advantage over unilateral action in Stage 1.

Next, I make the following assumption concerning the ordering of initial ideal points:

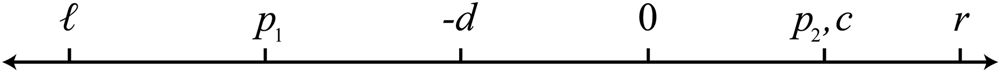

Assumption 2 (Ordering of initial ideal points and quantities): Initial ideal points and quantities are ordered as follows: ℓ < p 1 < −d < p 2 = c < r.

Essentially, in Stage 1, there is divided government. In Stage 2, there is unified government. This assumption allows us to study the central question of interest, which concerns the persistence of unilateral action. In Stage 1, the president may potentially have good reason to take unilateral action, as a misaligned Congress could refuse to help move policy any farther than what the president can achieve unilaterally. In Stage 2, any previous (necessarily leftward) policy shift, whether unilateral or legislative, faces the threat of a potentially opposed unified government on the right. Thus, in addition to the clarity granted by this assumption, we have the hardest case in which to find policy persistence, which only strengthens the results presented below.Footnote 5 Additionally, to examine L's trade-off in Stage 1, I suppose that Congress does not already prefer to pass legislation to the left of the president's discretion bound. I also require that P 1 not be able to achieve his ideal point solely through unilateral action. Finally, the groups are more extreme than other players. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. A possible ordering of initial ideal points and other quantities.

Next, I assume the following about C's behavior:

Assumption 3 (C's behavior under indifference): When indifferent, C declines to pass legislation.

In some cases, C may decline to pass legislation knowing that P t will pursue equivalent unilateral action. This corresponds to C facing an arbitrarily small but strictly positive cost from passing legislation. This can stem from signaling costs (Foster, Reference Foster2022) or simple transaction costs.

Next, the budget B shall be a function of policy in the previous stage:

Assumption 4 (Budget): In Stage t, the budget of group I ∈ {L, R} is

with α I > 0, β > 0, and F L (F R) being a strictly decreasing (increasing) function such that F L(0) = F R(0) = 0.

Here, α I can be seen as I's initial strength. Importantly, when policy moves in favor of (against) a group, its strength increases (decreases) in proportion to β, which is the strength of positive policy feedback effects. This can be interpreted either as provision of money directly from government or as facilitating conditions that allow for each group to earn profits in private markets.Footnote 6

Next, I assume that no group is so powerful that it can influence policy so much on net so as to achieve satiety in either stage. An equivalent framing is that both groups’ preferences are sufficiently extreme:

Assumption 5 (Maximum group power): We have $B_t^I( \alpha ^R - \alpha ^L) > 0$![]() for each I ∈ {L, R}. Group ideal points ℓ and r satisfy the following:

for each I ∈ {L, R}. Group ideal points ℓ and r satisfy the following:

This is another way of simplifying the analysis, allowing us to suppose that each group uses its entire budget in each stage (and doing so in Stage 1 leads to positive budgets for each group in Stage 2). We would reach the same results if we instead changed the utility functions of L and R always to prefer policy farther left and right, respectively.

Finally, I rule out the possibility that group R's budget is so large that P 1 would ever prefer policy to move rightward:

Assumption 6 (Maximum strength of group R): We have α R < α L − p 1.

This simplifies the analysis and keeps the focus on when legislation or unilateral action helping a constituent group is achieved. Without this assumption it of course could be possible that a very weak group would “get” legislation contravening its goals.

2.1.4 Equilibrium

As I examine myopic players in a sequential game of complete and perfect information, I focus on play of a subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium (SPNE) within each stage while allowing for myopia across stages. I restrict attention to pure strategies. A pure strategy for group I ∈ {L, R} in Stage t is a number $k_t^I \in [ 0,\; B_t^I]$![]() representing player I's choice of influence. A pure strategy for C in Stage t is a function ${\opf S}^C_t\, \colon \, [ 0,\; B_t^L] \times [ 0,\; B_t^R] \to \{ 0,\; 1\} \times {\opf R}$

representing player I's choice of influence. A pure strategy for C in Stage t is a function ${\opf S}^C_t\, \colon \, [ 0,\; B_t^L] \times [ 0,\; B_t^R] \to \{ 0,\; 1\} \times {\opf R}$![]() that maps influence by L and R respectively to a decision of whether to pass legislation and a specific policy. A pure strategy for P t in Stage t is a function ${\opf S}^{P_t}_t\, \colon \, [ 0,\; B_t^L] \times [ 0,\; B_t^R] \times \{ 0,\; 1\} \times {\opf R} \to \{ 0,\; 1\} \times {\opf R}$

that maps influence by L and R respectively to a decision of whether to pass legislation and a specific policy. A pure strategy for P t in Stage t is a function ${\opf S}^{P_t}_t\, \colon \, [ 0,\; B_t^L] \times [ 0,\; B_t^R] \times \{ 0,\; 1\} \times {\opf R} \to \{ 0,\; 1\} \times {\opf R}$![]() that maps influence by L and R respectively, C's decision whether to propose any legislation, and the specific policy proposed by C to a decision of whether to take unilateral action and a specific policy. An equilibrium is a strategy profile such that players’ strategies are sequentially rational within each stage.

that maps influence by L and R respectively, C's decision whether to propose any legislation, and the specific policy proposed by C to a decision of whether to take unilateral action and a specific policy. An equilibrium is a strategy profile such that players’ strategies are sequentially rational within each stage.

2.1.5 Summary

Let t ∈ {1, 2} and I ∈ {L, R}. The exogenous parameters are c, p t, ℓ, r, d, α I, and β. The endogenous choices are I's influence in each Stage ($k_t^I$![]() ), Congress's decision whether to offer legislation and choice of a specific policy, the president's decision of which legislation to sign if offered, and (given legislative failure) the president's decision whether to pursue unilateral action and choice of a specific policy. These choices determine the policy outcome x t. Players play a pure-strategy SPNE within each stage but are myopic across stages.

), Congress's decision whether to offer legislation and choice of a specific policy, the president's decision of which legislation to sign if offered, and (given legislative failure) the president's decision whether to pursue unilateral action and choice of a specific policy. These choices determine the policy outcome x t. Players play a pure-strategy SPNE within each stage but are myopic across stages.

2.2 Discussion

2.2.1 Related models

While a sizable American politics literature has considered the role of positive policy feedback (Pierson, Reference Pierson1993, Reference Pierson1996; Soss and Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007; Mettler and SoRelle, Reference Mettler and SoRelle.2018; Larsen, Reference Larsen2019), few models of politics have examined its role in policymaking. The prior focus has largely been on gridlock intervals, which are a form of negative policy feedback (Krehbiel, Reference Krehbiel1998; Howell, Reference Howell2003; Buisseret and Bernhardt, Reference Buisseret and Bernhardt2017; Dziuda and Loeper, Reference Dziuda and Loeper2018). While this may coherently explain legislative policymaking absent the possibility of unilateral action, it is inconsistent with Congress looking ahead to the possibility that the president takes unilateral action should it fail to act (Foster, Reference Foster2022). Conceptually, the present model thus builds on my earlier work by further examining the relationship between outside influences on policy and the mode used to enact it.

Another related literature concerns the effects of shifts in power on bargaining, demonstrating a wide range of conditions under which these shifts lead to inefficient conflict (see, e.g., Fearon, Reference Fearon1996; Powell, Reference Powell1996). Differing from these works, I do not seek to explain bargaining or the failure thereof, but rather the relationship between levels of and shifts in group power and the means by which policy is produced.

2.2.2 Substantive justification of assumptions

I now discuss some of the model's assumptions. First, consistent with Howell (Reference Howell2003), the president is seen as having ideological motivations. As discussed above, ideological disagreement with Congress is the interesting case in Stage 1. Then straightforwardly, only the left-leaning group has an opportunity to shift the status quo, as the president would veto any attempt to move policy rightward.Footnote 7 On the other hand, the left-leaning group has two different avenues of policy change available: rely on the left-leaning president to pursue an executive order, or pressure the right-leaning Congress sufficiently to enable cooperation with the president on legislation.

Next, I abstract away from heterogeneity within Congress. This follows Foster (Reference Foster2022), in which I demonstrate that when Congress can anticipate that the president takes unilateral action should Congress fail to act, gridlock intervals cannot explain legislative failure. I argue instead that signaling costs may explain Congress's failure to act, which justifies Assumption 3. Consistent with this, the focus of this paper is on those executive orders whose purpose is to substitute for would-be legislation that congressional inaction foreclosed, so for simplicity I allow the president to move after Congress.Footnote 8 In principle, it is possible to add additional congressional veto players to the model, though this would add complication while leaving the substantive conclusions unchanged. Indeed, the present substantive focus is on those executive orders that legally should have been able to be reversed by the president alone but for which this proves politically impossible. Adding additional veto points in Congress leaves conclusions about that case unchanged.

Next, groups L and R exert influence on C and P t. This is a reduced-form representation of many different possible channels of influence, including lobbying (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; Austen-Smith, Reference Austen-Smith1996), campaign contributions (Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman1994; Austen-Smith, Reference Austen-Smith1995), and public opinion (Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman2001, 319–45; Sobbrio, Reference Sobbrio2011). To ease the analysis, their influence is assumed to be transmitted to C and P t at equal rates. As I discuss in the “Robustness” section below, this is ultimately unnecessary for the core substantive results presented: allowing L and R to target C and P t separately, and letting there be different marginal costs of influencing each one, adds significant complication while leading us to the same broad conclusions.

For simplicity, players are assumed to live for a single stage, but this is also not needed to reach the same substantive results. Since interest groups in the model have fixed budgets that they fully exhaust, making them forward-looking changes nothing. And allowing C and P 1 to look forward to future policy consequences leaves substantive results largely unchanged. See Online Appendix B for full details.

Next, the expression for the budget $B_t^I$![]() captures aspects of how that relative power might be determined. First, I's initial budget, α I, can represent having a large donor base, a wealthy and powerful constituency, or extensive connections in Washington, DC. Second, β represents the magnitude of policy feedback effects. When policy moves in I's preferred direction from its initial position of zero, policy itself may affect I's ability to influence policy in the future. An extensive literature explores this idea (e.g., Pierson, Reference Pierson1993; Coate and Morris, Reference Coate and Morris1999; Callander et al., Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2022, Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2023). There may be different reasons to expect this effect. For example, policy can directly transfer resources to groups, induce firms’ unrecoverable investments in specific modes of operation, or allow the public to learn about the effectiveness of the policy. The literal implementation in the model is that of policy transferring resources to groups, either directly or through enacting rules that facilitate making profits. However, other forms of policy feedback should be seen as broadly compatible with the predictions of the model.

captures aspects of how that relative power might be determined. First, I's initial budget, α I, can represent having a large donor base, a wealthy and powerful constituency, or extensive connections in Washington, DC. Second, β represents the magnitude of policy feedback effects. When policy moves in I's preferred direction from its initial position of zero, policy itself may affect I's ability to influence policy in the future. An extensive literature explores this idea (e.g., Pierson, Reference Pierson1993; Coate and Morris, Reference Coate and Morris1999; Callander et al., Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2022, Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2023). There may be different reasons to expect this effect. For example, policy can directly transfer resources to groups, induce firms’ unrecoverable investments in specific modes of operation, or allow the public to learn about the effectiveness of the policy. The literal implementation in the model is that of policy transferring resources to groups, either directly or through enacting rules that facilitate making profits. However, other forms of policy feedback should be seen as broadly compatible with the predictions of the model.

2.3 Analysis

I first analyze when Stage 1 policy is produced either through legislation or unilateral action. Next, under each of these two outcomes, I ask when policy persists. That is, Stage 2 policy is farther left than Stage 1 policy. A key insight is that L's initial strength (α L) is associated both with legislation and with policy persistence. In fact, the fact that legislation has occurred means that α L is large enough such that policy always persists. On the other hand, unilateral action is imposed from outside and does not reflect a group's strength. In fact, it reflects the opposite: its necessity implies that L must have been too weak to secure legislation. But precisely when policy feedback effects (β) are large, the unilateral policy itself can increase L's strength in the future, such that L later achieves further policy gains.

2.3.1 Policymaking in Stage 1

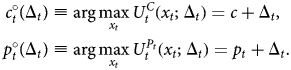

Because players are myopic, I start with Stage 1. It is convenient at this point to define the effective ideal points for C and P t, which I label $c_t^\circ$![]() and $p_t^\circ$

and $p_t^\circ$![]() , respectively. Defining $\Delta _t( k_t^L,\; k_t^R) \equiv k_t^R - k_t^L$

, respectively. Defining $\Delta _t( k_t^L,\; k_t^R) \equiv k_t^R - k_t^L$![]() and denoting this as net (rightward) influence, we have the following:

and denoting this as net (rightward) influence, we have the following:

Observe of course that c t°(0) = c and p t°(0) = p t. But when Δt is positive or negative, P t and C behave as if their ideal points have shifted right or left, respectively.

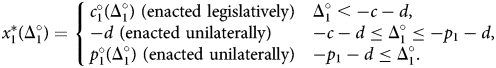

Now notice that L and R have no use for their budgets except to influence C and P 1, so they exhaust them and equilibrium net influence (denoted Δ1°) equals α R − α L.Footnote 9 If Δ1° is sufficiently large (i.e., p 1° moves sufficiently rightward), then P may actually moderate and enact unilateral action at p 1°. If Δ1° is intermediate, then p 1° does not move to the right of −d, but neither does c 1° move to the left of −d, so P enacts unilateral action at −d. Finally, if Δ1° is negative enough, c 1° moves to the left of −d, and c 1° is enacted legislatively. The policy outcome is summarized as follows (all proofs are in Online Appendix A):

Proposition 1 (Policy outcome and mode in Stage 1): The policy outcome in Stage 1 is

See Figure 2. Importantly, because Δ1° = α R − α L, the condition for legislation to occur slackens as α L increases and α R decreases. That is to say, when L is initially strong, it achieves legislation, whereas when L is initially weak, it must rely on unilateral action. This has important implications for policy persistence.

Figure 2. An illustration of Proposition 1.

2.3.2 Policymaking in Stage 2

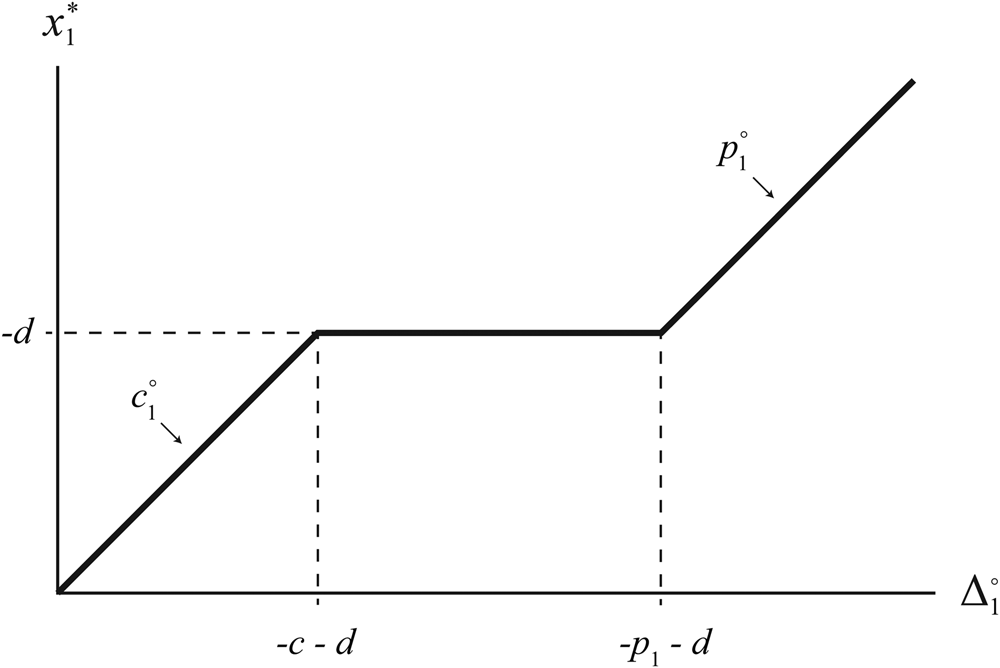

Straightforwardly, L and R exhaust their budgets to influence C and P 2, with the latter two achieving their shared effective ideal point in Stage 2. Then define

The equilibrium policy outcome as a function of x 1, denoted x 2°, is

Recall that Δ1° is equilibrium net influence from Stage 1, while the third term is the change in net influence induced by the Stage 1 policy. If x 1 > 0 and policy had previously moved rightward, the third term is positive. If x 1 < 0 and policy had previously moved leftward, the third term is negative.

2.3.3 Policy persistence

Defining $x_2^\ast \equiv x_2^{\circ }( x_1^\ast )$![]() , let us say that policy persists when $x_2^\ast < x_1^\ast$

, let us say that policy persists when $x_2^\ast < x_1^\ast$![]() . That is, L is able to parlay policymaking in Stage 1 into a greater leftward shift in Stage 2. The following result concerns legislation's persistence:

. That is, L is able to parlay policymaking in Stage 1 into a greater leftward shift in Stage 2. The following result concerns legislation's persistence:

Proposition 2 (Persistent legislation): If legislation is an equilibrium outcome in Stage 1, it always persists.

Intuitively, the fact that legislation occurred in the first place means that L's initial strength was high, even before feedback effects from Stage 1 legislation potentially make it even stronger. More specifically, Assumptions 2 and 4 are important for driving this result. The fact of divided government in Stage 1 (due to Assumption 2) makes passing legislation more difficult. Then if legislation succeeds even despite this, it must reflect L having high initial strength relative to R to overcome this difficulty. Next, positive policy feedback effects only strengthen L in Stage 2 relative to its initial capacity (due to Assumption 4). Consequently, (left-leaning) legislation survives the right-leaning unified government that is assumed to follow. This is a hard case for persistence: the fact that it survives anyway implies that it would have persisted just as well under a divided or left-leaning unified government in Stage 2.Footnote 10

This highlights the fact that unilateral action that is reversed in Stage 2 may do so because its associated client group was too weak in Stage 1 to spend enough to achieve legislation. Then in Stage 2, that group may continue to be too weak to stave off reversal. However, if a group is strong enough to achieve legislation in Stage 1, its ability to influence C can only continue into Stage 2. This suggests that unilateral action's tendency to be reversed may reflect a selection effect: the mode of policymaking may be associated with the strength of the coalition demanding policy, such that there need not be any difference in the inherent (e.g., legal) persistence of legislation versus unilateral action to observe a difference.

When can unilateral action defy expectations and persist? Achieving legislation means that L must have started off strong. But in this setting, unilateral action is a fallback, used only when legislation fails. In that case, unilateral action must mean that L started off weak. Because of this, L may have trouble defending its policy gains against subsequent reversal in Stage 2. The exception to this is when policy feedback effects are strong. If unilateral action itself increases L's future strength, L may manage to preserve its gains. Temporarily relaxing the assumption that β > 0 to allow β = 0 as well, I reach the following result:

Proposition 3 (Persistent unilateral action): When β = 0, unilateral action does not persist. There exists a sufficiently large value of β such that unilateral action persists.

Unilateral action is able to persist when policy feedback effects are large. Group L may be initially weak (with α L small) and thus unable to exert sufficient pressure to achieve legislation in Stage 1. While it must settle for unilateral action, if β is large, this shift in policy itself allows the group to increase its resources in Stage 2. These resources may then be directed to preserving its policy gains. Thus, while legislation is typically seen as persistent and unilateral action as transient, here the latter crucially initiates a positive feedback loop that results in an enduring policy shift.Footnote 11

2.3.4 Summary

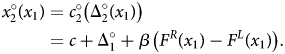

When L's initial strength (α L) is high, legislation occurs, and it always persists. When L's initial strength is low, unilateral action occurs. If policy feedback effects (β) are small, unilateral action does not persist, and an association between unilateral action and policy reversal is induced. However, if policy feedback effects are large, unilateral policy allows L to break free of its initially low strength and build on its gains in the future. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. A parametric illustration of Propositions 1 through 3 in which F L(x t−1) = −x t−1 and F R(x t−1) = x t−1. In Region I, unilateral action occurs and it does not persist. In Region II, unilateral action occurs and it persists. In Region III, legislation occurs and it persists. (The white region in the upper right does not satisfy Assumption 5). In this example, c = 1, $d = \frac{1}{2}$![]() , p 1 = −1, and α R = 2.

, p 1 = −1, and α R = 2.

3. Robustness

In this section, I discuss possible extensions to and variations on the model, including forward-looking players, other successions of governments, generalized (either positive or negative) policy feedback effects, the president moving first, and groups being able to target each politician separately.

3.1 Forward-looking players

I allow P 1, C, L, and R to look forward to Stage 2 as of Stage 1. In particular, they evaluate potential future policy outcomes in light of their current preferences (with those of L and R unchanging of course). As long as analogous assumptions continue to hold for L and R, especially a version of Assumption 5, they continue to exhaust their budgets in each stage as before. Next, I let F L(x t−1) = −x t−1 and F R(x t−1) = x t−1 for tractability. I find that an analog to Proposition 1 holds with different thresholds. Next, Proposition 2 continues to hold, taking into account C's new optimum. Finally, parts of Proposition 3 continue to hold. If any unilateral action is persistent, it must be that β is strictly positive. See Online Appendix B for full details.

3.2 Other successions of governments

To relax Assumption 2, consider other successions of governments across Stages 1 and 2. As noted above, any other Stage 2 government would still allow legislative policy to persist at all times. It may allow unilateral policy to persist when it would otherwise be reversed above, though not always. Meanwhile, if allowing for a unified government in Stage 1, Congress's choice not to pass legislation when indifferent (given Assumption 3) is key. Unilateral policy would still be associated with a small shift (and thus a weak constituent group) while legislative policy would still be associated with a large shift (and thus a strong constituent group). In any of these variations, the groups would continue to exhaust their budgets in each stage and would do so even if they were not myopic.

3.3 Positive or negative policy feedback effects

To relax Assumption 4, we can consider arbitrary forms of policy feedback (positive or negative β). One might imagine that negative feedback could occur if policy shifts motivate subsequent backlash. With myopic groups, Stage 1 play is the same: group L gets legislation when strong and unilateral action when weak. In Stage 2, legislation persists as long as policy feedback is strictly greater than zero, whereas unilateral action only persists when policy feedback is greater than some strictly positive threshold. Here though the myopia assumption becomes more consequential, as a group looking ahead to backlash may instead choose not to take advantage of their policy opportunities in Stage 1; for further analysis of this phenomenon, see Buisseret and Bernhardt (Reference Buisseret and Bernhardt2017).

3.4 President moves first

We can consider how the results would change if the president moved first. In a model such as that of Howell (Reference Howell2003), the choice of policymaking mode is not a central question. Congress is assumed only to react against unilateral presidential policymaking, with the possibility of freestanding legislation not considered. Thus, adapting this sort of setup to the present purpose would require a number of alterations. One might presently allow the president to move first as well as adding an option to take no action, with policy considered legislative whenever Congress takes any subsequent action (which then requires presidential approval). Just as is demonstrated in the “Analysis” section above, the president would prefer to take unilateral action whenever what was possible to achieve (given the discretion bound) would sit closer to the president's effective ideal point compared to what Congress would be anticipated to do. And should Congress's effective ideal point be pushed extreme to the discretion bound, the president may decline to take unilateral action because subsequent legislation would achieve better policy. Thus, results would remain unchanged.

3.5 Separate targeting of each politician

We can allow the groups to target each politician separately. This leads to the same substantive conclusions. Recall that in the first stage, P 1 is far to the left, so in the original model, the fact that P 1 shifts along with C in Stage 1 was inconsequential. Then in this modified setup, spending would be entirely focused on shifting C. As before, if R had a relatively large budget, unilateralism would occur, whereas if L had a relatively large budget, group spending would on net push C to the left of the unilateralism discretion threshold.

Next, in Stage 2, further complications arise, but the results imply the same broad interpretation. The key observation to make is that P 2 continues to hold the option to pursue unilateralism without the approval of C, but this is constrained. Net of R's countervailing influence, L would first prioritize influencing P 2 up to the point that P 2's discretion limit binds. At that point, if L had additional funds to spend, it could then focus on influencing C to achieve further legislative gains. This is true even if the marginal cost of influencing P 2 differs from that of influencing C. As before, if L had a large budget relative to R, it would achieve more leftward policy. And the same pathways to a large budget in Stage 2 exist as before: Stage 1 unilateralism and high policy feedback effects, or a large initial budget in Stage 1 (implying that legislation happened in Stage 1). Then the overall conclusions remain unchanged.

4. Relating the model to empirical work

I informally discuss the relationship between the model's logic and empirical work on executive order persistence. Most notably, Thrower (Reference Thrower2017) and Thrower (Reference Thrower2023) show that executive orders issued under divided government are less likely to be rescinded than those issued under unified government. Thrower argues that this is due to ideological compromise: facing an opposed Congress, the president might forestall retaliation by issuing orders that are more moderate, making them less attractive targets for subsequent administrations. Broadly, the ideas underlying the present model and its extensions do not contradict this story, but they suggest an additional explanation for this empirical pattern.

While I presently model what happens once a policy area arises, the president might first need to choose a policy on which to focus, given limited capacity. This would imply important strategic differences between unified and divided government. Under unified government, issuing executive orders intended to substitute for legislation may not be as necessary, because Congress is aligned. The president might instead focus on issuing orders that implement this legislation, potentially presenting ripe targets for future opposed presidents. On the other hand, under divided government, more policies desired by the president can only happen unilaterally. A forward-looking president might strategically select those policies that are most likely to exhibit positive feedback effects, because they provide the greatest long-term return. This could help contribute to a lower rate of executive order rescission for those issued under divided government.

5. Case study: cannabis legalization

5.0.1 Moderate increase in left-leaning group's initial strength

Not long ago, making any progress on cannabis legalization was unlikely, given Congress's decades-long history of supporting cannabis criminalization and the weak position of pro-legalization activists. At that point, pro-legalization interests’ initial strength (α L) was so negligible such that even policy feedback effects could not allow attempts at liberalization to persist, corresponding to Region I of Figure 3. Yet by 2008, activists’ efforts made the political landscape somewhat more amenable to future policy change, cracking open the door with the success of medical programs at the state level. It was not obvious though that this pro-legalization trend would continue. Although weakened, the position of anti-drug activists in both parties still remained too strong to allow a serious effort to undermine drug prohibition at the national level, corresponding to a moderate increase in α L.Footnote 12 Thus, while pro-legalization activists increased their strength enough to reach Region II of Figure 3, they failed to reach Region III.

5.0.2 Unilateral policy unlocked policy feedback effects

As the model predicts, a small value of α L prevented Congress from passing legalization legislation. It was left to President Obama's Department of Justice to ease the federal prohibition of cannabis. In 2009, the DOJ issued the Ogden Memorandum, which declared that it would not prioritize targeting individuals involved in the sale and use of cannabis for medical purposes (Schroyer, Reference Schroyer2016). Just three years later, Colorado and Washington State voted to legalize cannabis for recreational purposes within regimes of taxation and regulation. Yet at the time it seemed likely that the DOJ would undo these efforts either by asking federal courts to strike down the new state laws as preempted by the Controlled Substances Act or by deploying federal drug enforcement agents. Former Drug Enforcement Agency head Asa Hutchinson stated, “The stage is set for a confrontation of massive proportions” (Tau, Reference Tau2012).

Instead of pursuing either of these options, though, the DOJ issued the Cole Memorandum, declaring that while the Controlled Substances Act remained in force, the DOJ would defer to local and state authorities in most circumstances (Daum, Reference Daum2018).Footnote 13 This key directive cemented a self-reinforcing cycle moving in the direction of full legalization. With Colorado's legal cannabis industry free from federal interference, at least at that moment, the industry's existence created jobs, generated hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue, and shifted public opinion favorably (Daum, Reference Daum2018), corresponding to strongly positive policy feedback effects (large β). In time, a number of other states moved in the direction of legalization, going from prohibition to a medical use regime or from medical to recreational.

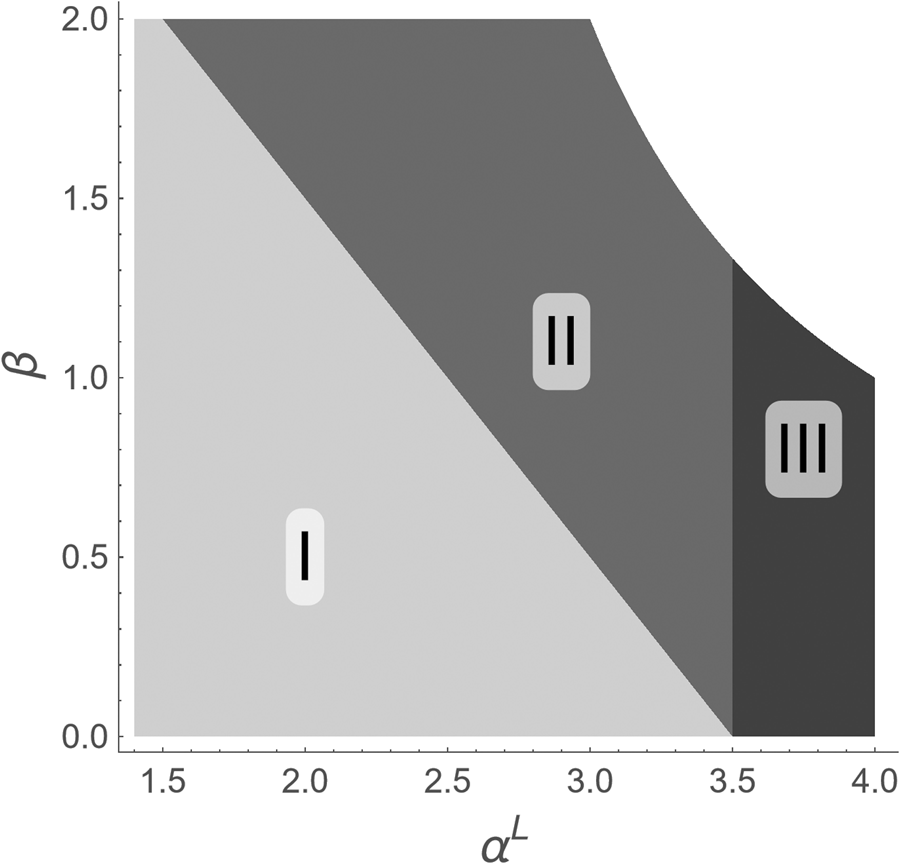

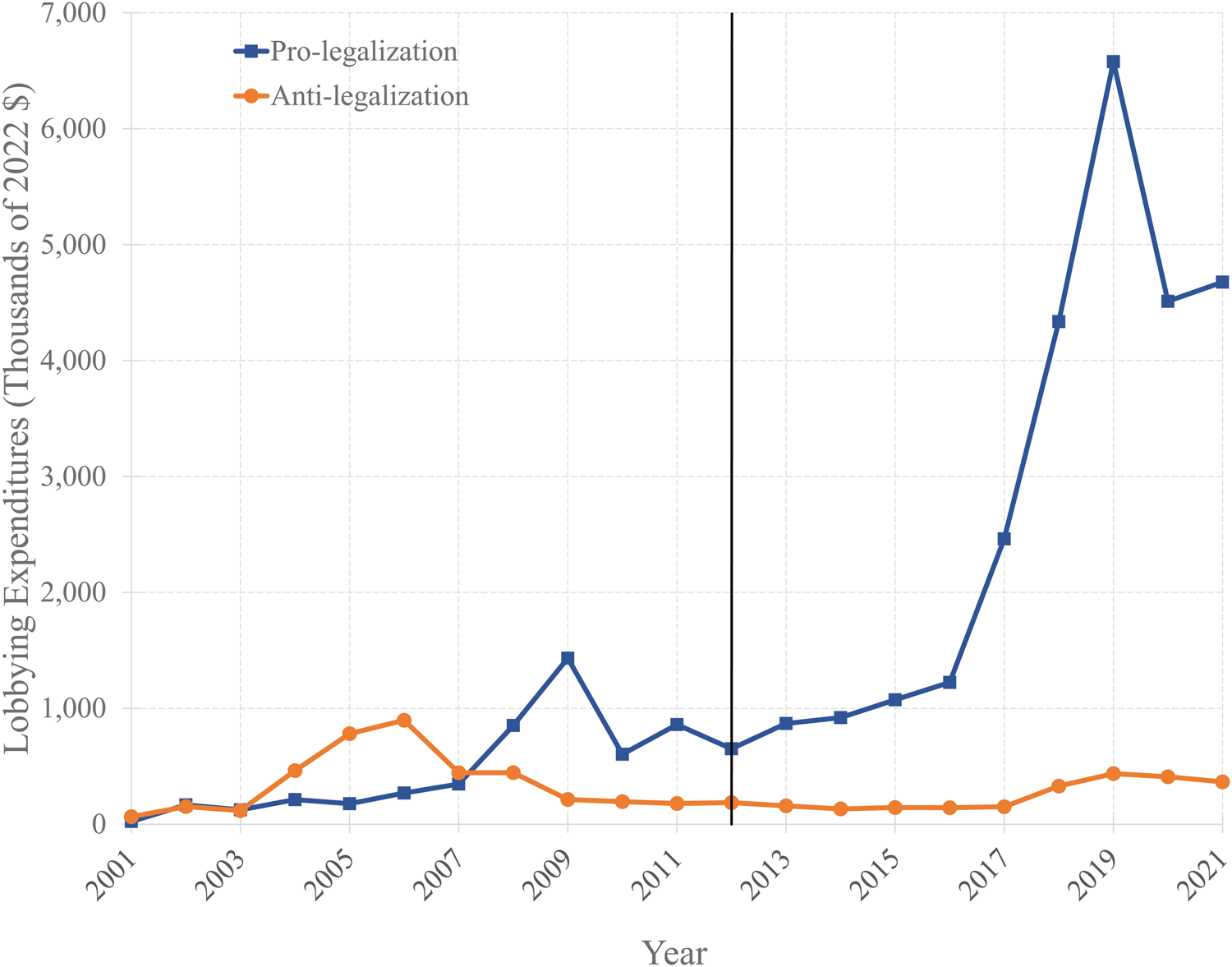

By 2016, traditional big business started moving in to take advantage of new opportunities for profit, further evincing a large value of β. For example, Microsoft began offering software to state governments to help track cannabis sales (Weyl and Nussbaum, Reference Weyl and Nussbaum2016). This paralleled a number of small but noticeable steps that Congress began taking to ease its stance on cannabis. As Weyl and Nussbaum noted, “Bills funding the Veterans Affairs Department have a line that lifts a prohibition on medical marijuana. The Senate Appropriations Committee has adopted provisions barring the federal government from interfering on pot enforcement where medical marijuana is already legal. And there's movement in both chambers to make sure banks don't get penalized for handling money from legal pot businesses.” It was no coincidence that pro-legalization groups’ lobbying expenditures had spiked compared to those of opponents (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Pro-legalization groups’ lobbying expenditures have spiked while those of anti-legalization groups have remained low following the Cole Memorandum in 2012. See Online Appendix C for a description of how the figure was generated, including a list of groups. Sources: Center for Responsive Politics (2022) and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2024).

5.0.3 Policy feedback effects thwarted Trump Administration efforts

In the 2016 election, legalization advocates won yet another victory with passage of recreational legalization in California. Yet they feared the possibility that a Trump DOJ might undo the progress that had been made so far. Formally, Trump's Attorney General had the power to revoke the Ogden and Cole Memoranda and crack down on what had effectively become a legal industry up to that point. Despite assurances from Attorney General Jeff Sessions in March 2017 that such a crackdown was not imminent (Everett, Reference Everett2017), in January 2018 he rescinded the memoranda (Gerstein and Lima, Reference Gerstein and Lima2018). Senator Cory Gardner (R-CO) immediately announced that he would place a hold on all nominees for the Department of Justice until the Attorney General backed off his threats to resume enforcement (Paul and Murray, Reference Paul and Murray2018). Although Gardner had not favored legalization in 2012, by 2018 he was strongly committed to defending the Colorado law, forcing the Trump Administration through three months of holds on 20 different nominations (Welch, Reference Welch2018). In April, Gardner lifted his holds after receiving a promise that the DOJ would not interfere with Colorado's legal cannabis industry, vowing to reinstate the holds if this ever changed (Everett, Reference Everett2018). The DOJ kept its promise: as of January 2020, it had not evidently resumed enforcement against state-legalized activities that had previously been protected by the Ogden and Cole Memoranda (Firestone, Reference Firestone2020).

5.0.4 Future prospects for legalization

Following Cory Gardner's defense of the legal cannabis industry, it continued to amass political influence and powerful friends. In April 2018, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell expressed support for legalizing hemp, a non-psychoactive cannabis derivative (Grant, Reference Grant2018). And John Boehner, a former Republican speaker of the House, joined the board of cannabis company Acreage Holdings (Grant, Reference Grant2018). That June, President Trump expressed support for a bipartisan bill from Senators Gardner and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) to allow states to determine their approach to cannabis (Lima, Reference Lima2018). Enticed by the prospect of new business, banking trade groups echoed Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell in pushing Congress to change banking laws to ensure that cannabis businesses can access banking (Warmbrodt, Reference Warmbrodt2018). Although members of Congress regularly used to return contributions from the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (Levinthal and Parti, Reference Levinthal and Parti2013), that year “Democrats [rushed] to support this issue in congressional races across the country” (Higdon, Reference Higdon2018a; see also Higdon, Reference Higdon2018b, Reference Higdon2018c). In December 2022, President Biden signed a bill to expand medical cannabis research after it passed the House and Senate by unanimous consent (Sabaghi, Reference Sabaghi2022), in March 2023, Senators Jon Tester (D-MT) and Mike Braun (R-IN) introduced a bipartisan bill to ease requirements on industrial hemp farmers (Lippman and Otterbein, Reference Lippman and Otterbein2023), and that August, President Biden's Department of Health and Human Services formally recommended that the Drug Enforcement Agency move cannabis from Schedule I to the less-stringent Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act (Fertig and Demko, Reference Fertig and Demko2023).

The increasing connection between cannabis and business power suggests that more politicians will soon follow the path of Cory Gardner and others in moving toward support for legalized cannabis. Keegan Peterson, the CEO of a workforce management company serving cannabis businesses, captured the new zeitgeist clearly when he said, “This is a bipartisan issue. It's small business supporting small business” (Grant, Reference Grant2018). With many political observers’ attention focused on polarization, this case thus also demonstrates that groups can sometimes de-polarize issues. What allowed for these dramatic shifts was Washington's and Colorado's 2012 legalizations of recreational use and the Obama Administration's refusal to crush the nascent industry, along with the high potential for policy feedback inherent in the issue. Given the shifting landscape of group power, future play of the game may occur in Region III of Figure 3, which is consistent with continued leftward policy shifts through legislation.

5.0.5 Other policy areas

The mechanisms at play here arguably also apply to other policy areas. Broadly, this includes any issue for which a policy constituency demanding change is initially weak but whose demands would set off policy feedback effects. A case that fits a broad interpretation of the model is that of the Obama Administration's Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which President Obama pursued after the failure of comprehensive immigration reform in order to prevent the deportation of undocumented migrants brought to the US as children. While it was the Supreme Court that later stopped the Trump Administration from rescinding DACA, the present theoretical framework can be seen to fit for two reasons. First, many argue that the Supreme Court itself should be seen as a political actor, with its decisions influenced by partisan, ideological, and economic considerations (Epps and Sitaraman, Reference Epps and Sitaraman2019; Tribe, Reference Tribe2022). Second, Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the majority, invoked respondents’ explicit arguments about policy feedback mechanisms in his justification for preserving the DACA program:

[Respondents] stress that, since 2012, DACA recipients have “enrolled in degree programs, embarked on careers, started businesses, purchased homes, and even married and had children, all in reliance” on the DACA program. The consequences of the rescission, respondents emphasize, would “radiate outward” to DACA recipients’ families, including their 200,000 U.S.-citizen children, to the schools where DACA recipients study and teach, and to the employers who have invested time and money in training them. In addition, excluding DACA recipients from the lawful labor force may, they tell us, result in the loss of $215 billion in economic activity and an associated $60 billion in federal tax revenue over the next ten years. Meanwhile, States and local governments could lose $1.25 billion in tax revenue each year…. [The Department of Homeland Security] may determine, in the particular context before it, that other interests and policy concerns outweigh any reliance interests. Making that difficult decision was the agency's job, but the agency failed to do it. (Department of Homeland Security et al. v. Regents of the University of California et al., 2020, 24–5)

Thus, at a minimum, these feedback mechanisms created an additional burden on the bureaucracy to justify the termination of a program created unilaterally under a previous administration. And beyond a sincere interpretation of the Court's justification, the Court may have deferred to newly vested interests in stopping the Trump Administration from undoing their benefits.Footnote 14

6. Conclusion

This paper has presented a novel argument to explain the often supposed and sometimes observed persistence of legislation compared to unilateral action. Presenting a formal model, I demonstrated that this may occur because groups that are initially well-resourced enough to induce legislation may retain this capacity in the future. Groups that start out weak may instead need to rely on unilateral action to achieve policy change, such that the policy has a weak supporting coalition when it comes time to defend it against possible reversal in the future. But strong policy feedback effects break the association between unilateral action and policy reversal. The model's results imply that, contrary to common expectations, unilateral policy can persist even through opposed administrations. The key explanatory factors are where relative group power starts and how it shifts as a function of policy.

The case of cannabis policy under Presidents Obama and Trump illustrated these implications of the model. Before the actions of President Obama's DOJ, cannabis legalization advocates arguably held little power to influence national politicians. This prevented Congress from offering legislation to legalize recreational use of cannabis at the federal level. Once the DOJ declined to intervene in Colorado and Washington, though, legal cannabis growers were able to accumulate wealth and influence such that today, the political climate is more favorable for them than ever. This is a real-world example in which rather than being easily reversed, unilateral policy proved enduringly consequential. And a shift in group power, brought about by the policy itself, was crucial to preserving these policy gains. Future work on unilateralism should continue to look beyond formal institutions by investigating the role of interest groups, the public, and other actors. This is crucial to understanding the normative implications of unilateral action for democratic accountability.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2024.37. To obtain replication material for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/P7ABK3.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments, I thank Dan Alexander, Todd Belt, Nate Birkhead, Alex Bolton, Felix Dwinger, Victoria Farrar-Myers, Sean Gailmard, Michael Grillo, Rafael Hortala-Vallve, Myunghoon Kang, David Karol, Kenny Lowande, Yu Ouyang, Eric Schickler, Sharece Thrower, Robert P. Van Houweling, Joseph Warren, Stephane Wolton, numerous seminar audiences, and two anonymous reviewers.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.