The separation of powers (SOP)—how the different branches of government collaborate in the making and implementing of public policy—represents a vital aspect of American politics. One SOP relationship garnering substantial attention concerns the interactions between the U.S. Congress and Supreme Court. Scholars have examined the dealings between these institutions in multiple ways, including the extent to which Congress influences Supreme Court decisions (e.g., Reference ClarkClark 2011; Reference Gely and SpillerGely and Spiller 1990; Reference Hansford and DamoreHansford and Damore 2000; Reference Harvey and FriedmanHarvey and Friedman 2009; Reference OwensOwens 2010; Reference Sala and SpriggsSala and Spriggs 2004; Reference SegalSegal 1997; Reference Spiller and GelySpiller and Gely 1992), whether the Court constrains congressional decisionmaking (e.g., Reference MartinMartin 2001), and the circumstances under which Congress legislatively overrides Supreme Court decisions (e.g., Reference BlackstoneBlackstone 2013; Reference EskridgeEskridge 1991a; Reference Hausegger and BaumHausegger and Baum 1999; Reference Hettinger and ZornHettinger and Zorn 2005; Reference Ignagni and MeernikIgnagni and Meernik 1994; Reference Ignagni, Meernik and Lynn KingIgnagni, Meernik, and King 1998). Collectively, the literature uncovers a rich and complex interdependency between these two important American political institutions.

A core element of SOP studies is a spatial model of the policy process, in which political actors make decisions as a function of their preferences over the existing status quo and alternatives to it, as well as the preferences of other relevant politicians. Researchers thus assume that preferences over outcomes are a fundamental part of the policy-making process. Of particular interest to us, previous studies either (1) apply theoretical models that assume legislators respond to Court decisions based on their preferences over them (e.g., Reference Gely and SpillerGely and Spiller 1990; Reference SegalSegal 1997) or (2) explicitly hypothesize that ideological disagreement with Court decisions causes Congress to pass legislation overriding them (Reference EskridgeEskridge 1991a, Reference Eskridge1991b; Reference Hettinger and ZornHettinger and Zorn 2005; Reference Ignagni, Meernik and Lynn KingIgnagni, Meernik, and King 1998; Reference Staudt, Lindstadt and O'ConnorStaudt, Lindstadt, and O'Connor 2007). This perspective seems reasonable in light of the centrality of policy preferences in contemporary explanations of congressional decisionmaking (Reference Aldrich and RohdeAldrich and Rohde 2000; Reference Cox and McCubbinsCox and McCubbins 2005, Reference Cox and McCubbins2007; Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1991, Reference Krehbiel1998). Indeed, the congressional literature offers convincing empirical evidence that ideology plays a key role in explaining Members' votes on bills and the passage of legislation (e.g., Reference Poole and RosenthalPoole and Rosenthal 2007). Yet, the literature examining federal legislation overriding Court decisions uncovers no systematic evidence they result from Congress' preferences regarding them.

To be fair, existing studies illustrate that preferences play a role in explaining some of Congress' interactions with the Court. One area in which policy preferences matter is in sponsorship (but not passage) of court-curbing bills, or bills aimed at limiting judicial power (Reference ClarkClark 2011; Reference CurryCurry 2007). Similarly, policy preferences influence the budget allocated to the Supreme Court, with Congress using the budget to signal its approval or disapproval of the Court's decisions (Reference TomaToma 1991). Additionally, Reference MartinMartin (2001) shows that the House and Senate consider the political preferences of both the other chamber and the Supreme Court when voting on civil rights legislation. However, research has not uncovered a link between legislative preferences and the passage of court-curbing bills (Reference ChutkowChutkow 2008; Reference CurryCurry 2007). Most relevant for this study, there is only anecdotal (Reference EskridgeEskridge 1991a, Reference Eskridge1991b) and quantitative case study (Reference Clark and McGuireClark and McGuire 1996)Footnote 1 evidence that legislative preferences influence the passage of legislation that overrides specific Supreme Court decisions.

We focus our study on this latter relationship and seek to address the following empirical issue: The congressional literature shows that the passage of legislation results from legislative preferences, but there is no systematic empirical evidence that override legislation occurs when legislative actors disagree with Court decisions. Our first objective is therefore to show empirically that Congress passes override legislation based on its preferences regarding the Court's decisions.

Second, we argue that Congress rationally anticipates Supreme Court review. Members of Congress concerned with the ultimate location of policy will avoid passing override legislation if the current Court will strike it down and replace it with a policy that may make Congress worse off than the status quo. While the broader SOP literature posits that Congress engages in this strategic behavior (e.g., Reference ClarkClark 2011; Reference RogersRogers 2001; Reference Rogers and VanbergRogers and Vanberg 2002), studies of congressional overrides do not. Indeed, only a handful of studies empirically examine legislative anticipation of High Court review, and none of them focuses on congressional overrides. Reference MartinMartin (2001) shows that House and Senate roll call votes in the area of civil rights were strategic, with members anticipating possible reaction by the Supreme Court to legislation. Reference ShipanShipan (1997) provides a formal model, accompanied by an illuminating case study, demonstrating that Congress strategically timed the passage of legislation concerning broadcast regulation in anticipation of how the Court would react. Additional theory and evidence for legislatures strategically anticipating High Court review exist in Germany (Reference VanbergVanberg 2001, Reference Vanberg2005), France (Reference StoneStone 1992), and the American states (Reference Langer and BraceLanger and Brace 2005). In short, we argue that Congress behaves strategically when considering whether to override Supreme Court decisions and avoids passing override legislation when it expects the current Court to reject it.

Our third and final objective concerns Congress' approach to overriding different types of Court decisions. Most studies suggest that the SOP relationship applies only to statutory cases (e.g., Reference EskridgeEskridge 1991a; Reference HenschenHenschen 1983; Reference Hettinger and ZornHettinger and Zorn 2005; Reference SegalSegal 1997; Reference Spiller and GelySpiller and Gely 1992). They based this assumption on the Court's long-standing assertion that it, and not Congress, possesses the power to interpret the Constitution (e.g., Dickerson v. U.S. 2000). Congress, this logic goes, cannot use ordinary legislation in response to a constitutional decision but must instead generally pursue a constitutional amendment. This idea has led some to claim that the Court strategically bases decisions on constitutional interpretation to protect them from potential congressional override (Reference Epstein, Segal and VictorEpstein, Segal, and Victor 2002; Reference KingKing 2007). The literature thus generally assumes, but does not empirically establish, that Congress is less likely to override a Court opinion it dislikes if it interprets the Constitution rather than a federal statute.

We, by contrast, argue that Congress bases its decisions to override both constitutional and statutory cases on its preferences regarding them. We are not the first scholars to recognize that Congress legislatively overrides constitutional decisions (e.g., Reference BlackstoneBlackstone 2013; Reference DahlDahl 1957; Reference FisherFisher 1998; Reference Meernik and IgnagniMeernik and Ignagni 1997; Reference Segal, Westerland and LindquistSegal, Westerland, and Lindquist 2011). As Reference Epstein, Knight and MartinEpstein, Knight, and Martin (2001: 599) write: “In addition, and this is worthy of emphasis, however much the Justices have stressed in recent cases they are the final arbiters of the Constitution, Congress has attempted to respond to constitutional decisions in the form of ordinary legislation.” We are, however, the first study to argue that Congress acts on its preferences over Court decisions regardless of whether it confronts a statutory or constitutional decision.

Our paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we state our expectations for the relationship between congressional preferences and overrides of Supreme Court decisions. In the section that follows, we discuss the measurement of our variables and the methodology we use to estimate the effect of legislative preferences on congressional overrides. We then present the results of our statistical analysis before concluding with a few thoughts about the broader implications of our empirical results. Our study produces three important conclusions. First, our data show that Congress overrides Court opinions with which it disagrees on policy grounds. We offer the first large-N quantitative evidence that Congress legislatively overrides Court decisions based on its preferences. In so doing, we provide empirical support for a foundational part of the SOP literature's theoretical understanding of Congress–Court relations. Second, we conclude that Congress does not act strategically by avoiding override legislation the Court is likely to reject. This result speaks to the relative power of the two branches, at least with respect to long-term influence over policy. If Congress does not behave strategically, essentially acting on position-taking motives (see Reference ArnoldArnold 1990; Reference MartinMartin 2001; Reference MayhewMayhew 1974), but the Court is strategic, taking into account the ultimate location of policy that results from the SOP (Reference ClarkClark 2011; Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight 1998), then the Court may have an advantage when it comes to the ultimate effect each institution has on policy outcomes. Third, we show that Congress acts on its preferences regardless of whether the Court uses statutory or constitutional interpretation.

The Role of Preferences in Congressional Overrides of Supreme Court Decisions

A wealth of congressional literature contends that members of Congress are motivated by policy goals (e.g., Reference ClausenClausen 1973; Reference Cox and McCubbinsCox and McCubbins 2005, Reference Cox and McCubbins2007; Reference FennoFenno 1973; Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1991, Reference Krehbiel1998). We argue that Congress decides whether to override Supreme Court decisions based on its preferences over those decisions.Footnote 2 In conceptualizing congressional preferences, we take a pivotal politics approach (Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1998). It is well recognized that Congress functions with multiple pivotal members, each of whom can potentially constrain legislation (e.g., Reference Hettinger and ZornHettinger and Zorn 2005; Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1998; Reference SegalSegal 1997). As a result, there exists a well-defined set of decision makers' ideal points within which policy cannot be shifted without making at least one veto player worse off than the status quo. We assume that the left (LP) and right pivotal (RP) members of Congress can block legislation.Footnote 3 As a result, the relationship between the LP and RP members and the status quo position (i.e., the Court decision) determines the likelihood of an override. We refer to a configuration of decision makers' preferences and a status quo in which policy cannot be altered as the gridlock region.

Overrides do not occur when policies are within the gridlock region. Any status quo between the LP legislative decision maker and the RP lies in the gridlock region and is invulnerable to congressional override. In Figure 1, SQ1 is within the gridlock region. Any movement of the status quo makes either the left or right pivot better off while making the other worse off. As a result, we do not anticipate congressional action in response to SQ1 since the legislative actor represented by the pivot that is made worse off by the shift in the status quo will block legislation.

Figure 1. Spatial Model of Congressional Overrides of Supreme Court Decisions.

For decisions outside the gridlock interval, we expect that the likelihood they are overridden is increasing in the ideological distance between them and the closest legislative actor comprising the gridlock region. While a pure spatial theory suggests that every Court decision outside the gridlock interval should be overridden—and the probability of override is constant outside of the gridlock interval—this assumes that overrides are costless. We assume that legislative overrides of Court decisions are not costless. To the extent that there are any costs (opportunity costs, if nothing else) to Congress associated with passing override legislation, the probability of the benefit of an override exceeding this unknown cost increases with the distance between the Supreme Court's decision and the closest pivotal legislative actor (conditional on the decision being outside the gridlock region).Footnote 4 Put differently, given the finite nature of the congressional agenda, we assume that Congress prioritizes the overriding of more “distant” (i.e., ideologically objectionable) precedents.Footnote 5 This suggests that the probability of an override is increasing in the ideological distance between the Court decision and the closest pivotal member.Footnote 6

In Figure 1, consider the two Court decisions represented by SQ2 and SQ3, each of which is outside the gridlock region. Both pivotal legislative actors agree that they want to pass legislation and change the status quo by moving policy within the gridlock interval. Based on the spatial proximity model (and assuming costs to passing overrides), it follows that the ideological distance between the closest pivot (in this case, RP) and the Court decision's location (status quo) affects the likelihood of override. In the particular instance shown in Figure 1, we expect that Congress is more likely to override the Court decision represented by SQ3 than the decision represented by SQ2 because the former is further away from RP, the closest pivotal member in Congress.

Hypothesis 1: When a Court decision (SQ) is outside the gridlock interval, Congress becomes more likely to override it as the ideological distance between SQ and the most proximate legislative decision maker defining the gridlock region increases.

Assuming Congress cares about the ultimate effect of public policy, it should avoid passing legislation when the Court is likely to strike it down. Congress acts strategically in this way because such Court action can produce policy that makes Congress worse off than the status quo (Reference Langer and BraceLanger and Brace 2005; Reference MartinMartin 2001; Reference Rogers and VanbergRogers and Vanberg 2002; Reference ShipanShipan 1997). Figure 2 shows the circumstances under which a Congress concerned about the ultimate content of policy can be constrained by the current Supreme Court. In what we label the Constrained Regime, the pivotal legislative decision makers want to change the status quo but the Court does not. In Figure 2, SQ is outside the gridlock interval and both pivotal legislative actors wish to override the Court decision. If the current Court is at or to the right of the midpoint (M) between the closest pivotal player and the status quo (the bolded region in Figure 2), it prefers the status quo to a congressional response to it (which would be located at RP). As a result, if Congress were to override the Supreme Court decision that constitutes the status quo location and set policy at RP, the Court could review the override legislation and set policy at its own ideal point. If Congress acts strategically and considers the ultimate policy effect of its actions, in the face of constraint, it will take the potential Court response to a legislative override into consideration and be less likely to act on its preferences.Footnote 7 Specifically, under the Constrained Regime, if Congress bases its override decisions on downstream policy concerns, and rationally anticipates Supreme Court review of legislation, there will be a dampening in the effect of ideological distance on overrides.

Hypothesis 2: If Congress acts strategically, then the ideological distance between the closest pivotal legislative actor and SQ will not influence the probability of a congressional override when Congress encounters a Constrained Regime.

Figure 2. Spatial Model of Congressional Overrides that Takes Account of Strategic Anticipation of Court Review.

To examine this hypothesis, we must consider the null hypothesis—that Congress is motivated by short-term, position-taking goals and does not consider the possibility of being struck down by the current Court (see Reference MartinMartin 2001). We differentiate between the strategic and null hypotheses by comparing congressional decisionmaking in the Constrained Regime with the Unconstrained Regime. In the Unconstrained Regime, both the pivotal legislative actors and the Court dislike the status quo and want to alter it. Consequently, Congress can override the Court decision free of concern that the Court will retaliate by overturning the law in a subsequent Court case. This scenario exists, in Figure 2, for any Court located to the left of M (the midpoint between RP and SQ), which is denoted by the dashed region in the figure. Congress is unconstrained in this situation because the Court prefers the policy that would result from the legislative override to the status quo. Our results would be consistent with the null hypothesis—that Congress does not act strategically-if the likelihood of an override is increasing in the ideological distance between pivotal legislative actors and the Court decision in both the Constrained and the Unconstrained Regimes (and the effect of Ideological Distance does not differ across the two regimes).

In addition, we submit that the influence of congressional preferences on overrides applies to all Court decisions, regardless of their legal basis. The bulk of the literature on Congress–Court relations assumes that congressional overrides are exclusive to statutory interpretation cases. The rationale is that Congress does not possess the power to legislate on the meaning of the Constitution; if Congress wants to challenge a constitutional decision, it must, they suggest, resort to a constitutional amendment. While the Court has declared it, and not Congress, has legal authority to interpret the Constitution, there are several reasons to expect the SOP to apply to constitutional cases. First, legislative challenges to the Court's constitutional decisions can harm the Court's institutional legitimacy, and thus, the Court has an incentive to strategically anticipate congressional responses to constitutional decisions (Reference Epstein, Knight and MartinEpstein, Knight, and Martin 2001; Reference Segal, Westerland and LindquistSegal, Westerland, and Lindquist 2011). This notion explains why the Court is less likely to strike federal legislation when it is ideologically distant from Congress (Reference Segal, Westerland and LindquistSegal, Westerland, and Lindquist 2011) or when Congress proposes more court-curbing bills (Reference ClarkClark 2011). It follows that Congress has an incentive to statutorily alter constitutional decisions that it dislikes. Second, a legislative override may not directly challenge the legal policy in a decision—the Court's interpretation of the Constitution—but rather statutorily alter the public policy that was challenged in the case (e.g., Reference BlackstoneBlackstone 2013; Reference PickerillPickerill 2004; Reference Sala and SpriggsSala and Spriggs 2004). Congress has clear authority to pass legislative overrides of the latter variety, even given the Court's assertion that it is the final arbiter of the Constitution. Finally, previous research shows that Congress does legislatively override constitutional decisions (Reference BlackstoneBlackstone 2013; Reference DahlDahl 1957; Reference FisherFisher 1998; Reference Ignagni and MeernikIgnagni and Meernik 1994; Reference Meernik and IgnagniMeernik and Ignagni 1995, Reference Meernik and Ignagni1997).Footnote 8 Our data reveal that constitutional cases account for roughly 16 percent of the legislative overrides of Supreme Court decisions from 1946 to 1990. We identify 197 overrides of Supreme Court cases. Of these overridden cases, 31 were decided based on the Constitution.

In short, we posit that Congress decides whether to legislatively override a Court decision based on policy motivations, regardless of whether the decision is based on the Constitution.Footnote 9

Hypothesis 3: The influence of the ideological distance between the closest pivotal legislative actor and SQ will not differ (i.e. will not be larger) in statutory cases than constitutional or common law ones.

Data and Methods

We seek to determine whether (1) federal laws that override Supreme Court decisions result because pivotal legislative actors dislike the judicial policies created by them, (2) Congress is strategic and is less likely to override Court decisions it dislikes when the current Court is likely to reject the legislation, and (3) legislative preferences matter regardless of the legal basis of a Court decision. To do so, we first identify the universe of Supreme Court decisions between 1946 and 1990 (N = 5484) using Reference SpaethSpaeth et al. (2012). Second, we use the United States Code Congressional and Administrative News (USCCAN), which provides legislative histories for federal laws, to determine whether a law dealt with a Supreme Court decision. If the legislative history in USCCAN indicates a law addressed a Supreme Court opinion, we then ascertain whether it explicitly ignored, overturned, modified, altered, undid, or corrected the Court decision, or limited or reversed the effects of the Court case, all of which we code as a legislative override. Since the Supreme Court Database begins in 1946 and USCCAN stops systematically reporting legislative histories by 1990, our empirical analysis examines congressional responses to the 5484 Supreme Court opinions released in this time frame. We code Congressional Override as one in the year Congress passes legislation that overrides a Court decision, else we code it zero. There are 197 instances of congressional overrides of these decisions.

Our unit of analysis is the Court decision-year, and our data include an observation for each Court decision in each year, starting in the year it was decided and ending in 1990. Our dataset includes 115,033 observations for these 5484 cases. Using these data, we estimate the probability of a congressional override of a Court decision in each year as a function of the ideological distance between the pivotal elected politicians and the Court decision.

To measure Ideological Distance, we need measures for three elements of the spatial model as depicted in Figures 1 and 2. First, we need a measure for the ideological location of the Court decision (SQ), for which we use the Judicial Common Space (JCS) score (Reference EpsteinEpstein et al. 2007) of the median Justice in the majority coalition that decided the case.Footnote 10 Second, we need measures for the LP and RP players in the legislative process. The JCS scores are designed to be on the same scale as NOMINATE Common Space scores, the latter of which represents the ideological locations of members of Congress and the president (Reference PoolePoole 1989; Reference Poole and RosenthalPoole and Rosenthal 2007). We therefore use first-dimension NOMINATE Common Space scores for our measure of the locations of members of Congress and the president.Footnote 11

The congressional decision-making literature agrees that legislative outcomes are strongly influenced by the preferences of elected politicians. They disagree, however, on precisely which decision makers are pivotal for the passage of legislation. There are three main alternatives. First, the chamber median model (Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1991, Reference Krehbiel1998) contends that the medians of the respective chambers determine the LP and RP actors. Second, the party gatekeeping model (Reference Aldrich and RohdeAldrich and Rohde 2000; Reference Cox and McCubbinsCox and McCubbins 2005, Reference Cox and McCubbins2007) argues that the pivotal actors are the left-most and right-most players among the majority party medians, chamber medians, and the president. As with the party gatekeeping model, the veto filibuster model emphasizes the importance of political parties; and in contrast to the former model, it takes into recognition the possibility of a Senate filibuster and a possible override of a president's veto. For Democratic presidents, the left pivot is the most liberal of the 146th representative and the 34th senator; and the right pivot is the 60th Senator (Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1998).Footnote 12 For a Republican president, the left pivot is the 40th Senator; and the right pivot is the most conservative between the 290th representative and the 67th Senator.

We use the veto filibuster model to identify which legislative actors comprise the gridlock interval. There is considerable evidence in the congressional politics literature that partisanship (as conceptualized in either the party gatekeeping model or the veto filibuster model) is important, and partisan models thus do a better job of explaining legislative outcomes than the chamber median model (see, e.g., Reference Johnson and RobertsJohnson and Roberts 2005; Reference KrehbielKrehbiel 1998; Reference Lawrence, Maltzman and SmithLawrence, Maltzman, and Smith 2006). We prefer the veto filibuster model to the party gatekeeping one because it incorporates the role of the president. We also find this arrangement of preferences to be the most compelling because it takes into consideration the most extreme actors who could block legislation. As a result, the gridlock interval will be largest in this model, meaning that fewer overrides would be expected in it. Because of the rare nature of congressional overrides of Supreme Court opinions, we view the veto filibuster model as the most appropriate for yielding the realized override decisions. However, regardless of which congressional model we use, our results are reasonably consistent.Footnote 13

Our measure of Ideological Distance equals zero if the Court decision (SQ) lies within the gridlock interval (inside the LP and RP legislative decision makers' preferences). If the Court decision lies outside that interval, then Ideological Distance equals the absolute value of the difference between the location of the Court decision and the closest pivotal legislator. Larger values indicate that the judicial status quo is further removed from the preferences of the pivotal legislative decision makers. Ideological Distance varies from 0 to 0.525, with a mean of 0.059, a standard deviation of 0.085, and an interquartile range of 0 and 0.106.

To test Hypothesis 1, which argues that overrides are more likely to occur when the judicial status quo is further removed from pivotal legislative actors, we estimate Model 1, which regresses Congressional Override on Ideological Distance (and additional control variables as described below). For this analysis, we include all Supreme Court decisions (regardless of whether the Court decision is constitutional, statutory, or common law), and we do not distinguish between whether Congress is in the Constrained Regime or Unconstrained Regime. Our expectation is that congressional overrides are increasing in Ideological Distance.

Hypothesis 2 argues that Congress rationally anticipates potential Court rejection of a legislative override. Specifically, if Congress is in the Constrained Regime—meaning Congress wishes to override but the current Court ideologically prefers the status quo to the new legislation—then the effect of Ideological Distance should be dampened. The null hypothesis is that Congress does not consider the current Court's preferences when deciding to override and there should be no difference in the effect of Ideological Distance between the Unconstrained Regime and Constrained Regime.

To test for this form of strategic behavior, we identify when the current Court could constrain Congress by considering the configuration of preferences and status quo points for the Unconstrained Regime and Constrained Regime as depicted in Figure 2. We measure the current Court's ideological position as the JCS score for the median Justice on the Court in a given year. We code Constrained Regime as one if the pivotal legislative actors want to override the Court decision, but the current Court prefers its decision to the potential outcome of the legislative bargaining game (the bold region in Figure 2). A Congress considers a Court decision when facing a Constrained Regime in 2.5 percent of the observations in our data. Unconstrained Regime equals one if the pivotal legislative actors and the Court ideologically prefer to alter the status quo; this is depicted in the dashed region in Figure 2, for situations when the current Court is located at or to the right of M. Congress faces an unconstrained situation in 47.2 percent of our data.Footnote 14

Based on a switching regime approach, we utilize two ideological distance measures in Model 2. The first, Ideological Distance-Unconstrained Regime, equals the value of Ideological Distance for any observation for which Unconstrained Regime equals one. For any observation for which Unconstrained Regime equals zero, the value of Ideological Distance-Unconstrained Regime equals zero. The second variable, Ideological Distance-Constrained Regime, equals the value of Ideological Distance for any observation for which Constrained Regime equals one. When Constrained Regime equals zero, Ideological Distance-Constrained Regime equals zero.Footnote 15 In so doing, we can estimate the effect of Ideological Distance separately for each of the two regimes. If Congress is strategic, then the coefficient on Ideological Distance-Constrained Regime should be statistically indistinguishable from zero and it should also be smaller than the coefficient on Ideological Distance-Unconstrained Regime. By contrast, if Congress is not strategic, then the coefficient on both Ideological Distance-Unconstrained Regime and Ideological Distance-Constrained Regime should be positive and statistically significant and there should be no statistically significant difference between the two.

To test Hypothesis 3, which argues that Congress overrides statutory, common law, and constitutional decisions based on its preferences, we code the legal basis of each case as constitutional interpretation, statutory interpretation, or common law interpretation/review of administrative action using Reference SpaethSpaeth et al. (2012). In Model 3, we include two dummy variables, Constitutional Decision and Common Law Decision, and code each as one if the case is based on that type of legal interpretation; else we code the variable as zero. We interact Constitutional Decision with Ideological Distance and also interact Common Law Decision with Ideological Distance to test whether the coefficient on Ideological Distance differs for constitutional or common law cases. The coefficient for the “main” effect of Ideological Distance indicates the effect of legislative preferences for statutory decisions; and the interaction terms indicate whether the effect of Ideological Distance differs for constitutional or common law decisions. Our expectation is that there will be no statistical difference in the effect of Ideological Distance between statutory and other decisions.

We use a random effects logit model (with a random constant for each Court decision) to estimate the probability of a congressional override in each year.Footnote 16 This type of approach is the equivalent of a discrete time duration model (Reference Box-Steffensmeier and JonesBox-Steffensmeier and Jones 2004), which is appropriate given the nature of both our dependent variable and key independent variable.Footnote 17 Because of the panel nature of our data, there is the potential for error correlation within a Court decision over time, and this estimation strategy helps ameliorate that issue.

We also include several control variables potentially correlated with both Ideological Distance and our dependent variable. Inclusion of these variables helps to ensure that the coefficient on Ideological Distance is not picking up variation due to one or more of them. The first control variable is a count of the number of times in a given year Supreme Court opinions are mentioned, but not overridden, in the legislative histories in USCCAN. In addition to coding all overrides of Supreme Court decisions, we coded each mention of a Supreme Court case in the legislative histories. To control for unmeasured factors that might influence the overall tendency of Congress to react to Court decisions and that might be correlated with Ideological Distance, we count every legislative response other than an override in each year. We label this variable, Total Congressional Responses in Year. The second control variable is the age of a Court decision. To allow a nonlinear relationship between age and Congressional Override, we parameterized it as a quadratic using two variables—the age of a case (Age of Decision) and its square (Age of Decision-Squared). Previous literature shows that the probability of override decreases as the age of the case increases (Reference Hettinger and ZornHettinger and Zorn 2005). Third, we include Total Judicial Cites to Decision, which is a count of the total number of times Shepard's Citations indicates federal courts (district, courts of appeals, and Supreme Court) cited a Court decision in years prior to the one under consideration, as drawn from Reference Black and SpriggsBlack and Spriggs (2013) and Reference FowlerFowler et al. (2007). By including this variable, we can ensure that any factors that contribute to overrides of cases that have been cited more frequently by federal courts that are also correlated with Ideological Distance are not biasing our result for Ideological Distance. Finally, we control for congressional attention to the issue in a case in the year under consideration by counting the number of congressional hearing days devoted to that issue using data from Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones (2013).Footnote 18 We use hearing days to measure congressional attention because we expect the issues that Congress addresses for ideological reasons to dominate much of the agenda, and as a result, should dominate most of the congressional hearings in a year. We also examine other possible controls and show our results are robust to including them.Footnote 19

Results

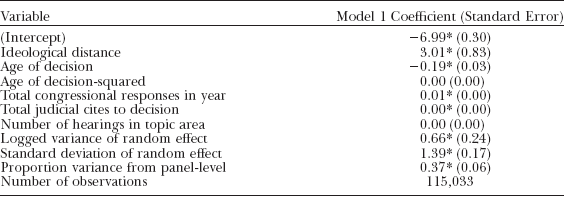

We report the results of our empirical analyses in Tables 1–3. The positive coefficient for Ideological Distance in Model 1 in Table 1 provides evidence in support of Hypothesis 1—Congress is more likely to override a Supreme Court decision when it is outside the gridlock interval and further ideologically from pivotal legislative actors. Congressional overrides occur infrequently—of the 5484 cases in our analysis, congressional overrides occurred for a total of 197 times. Our statistical model predicts that, in any given year, the average decision has a 0.022 percent chance of experiencing a congressional override.Footnote 20 Admittedly, this is a miniscule chance a particular case will be overturned in a year. As the ideological distance between Congress and a Court decision widens, the occurrence of overrides increases. As seen in Figure 3, when Ideological Distance is at its minimum value (approximately one standard deviation below the mean), there is a 0.018 percent chance of an override, and this percentage increases to 0.028 percent and 0.036 percent when Ideological Distance is, respectively, one and two standard deviations above the mean. While the likelihood of an override remains small in absolute terms, there is a reasonably large percentage increase in the probability of an override as a function of a change in Congress' ideological distance from a Court decision. A one standard deviation movement around the mean of Ideological Distance results in a 29.1 percent increase in the probability of an override, and a two standard deviation shift leads to a 66.4 percent increase in the frequency of Congress overriding a Court decision. This observed relationship is important because it substantiates one of the bedrock assumptions of SOP models by showing Congress passes override legislation based on its preferences.

Table 1. Test of Hypotheses 1: Congressional Overrides as a Function of the Ideological Distance between Pivotal Legislative Actors and Supreme Court Decisions

Note: We obtained the estimates in this table through estimation of a random effects logit model. Asterisk indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at a .05 confidence level (one-tailed test for theoretical variable of interest and two-tailed test for controls).

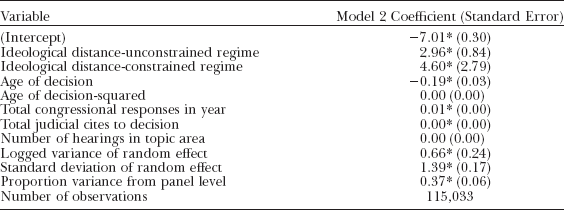

Table 2. Test of Hypothesis 2: Congress' Rational Anticipation of Supreme Court Reversals of Congressional Overrides

Note: We obtained the estimates in this table through estimation of a random effects logit model. Asterisk indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at a .05 confidence level (one-tailed test for theoretical variables of interest and two-tailed test for controls).

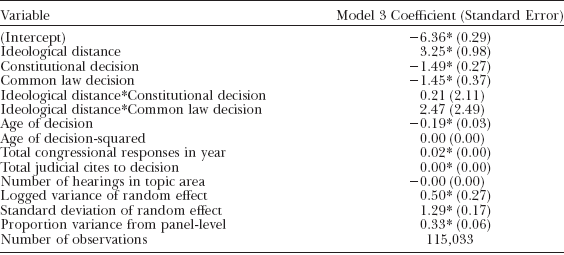

Table 3. Test of Hypothesis 3: Congressional Overrides of Supreme Court Decisions as a Function of Ideological Distance and the Legal Basis of a Case

Note: We obtained the estimates in this table through estimation of a random effects logit model. Asterisk indicates that the coefficient is statistically significant at a .05 confidence level (one-tailed test for theoretical variables of interest and two-tailed test for controls).

Figure 3. Substantive Effect of Ideological Distance on Congressional Overrides of Court Decisions.

In Hypothesis 2, we argue that a strategic Congress will be reluctant to override a decision the current Court ideologically prefers to the possible legislative response. We therefore separately estimate the effect of Ideological Distance for situations in which the Court and Congress both prefer to alter the status quo (Unconstrained Regime) to those in which Congress wishes to override the Court decision but the Court prefers the status quo (Constrained Regime). The results in Table 2 indicate that Congress does not act strategically when facing a Constrained Regime. We observe that Ideological Distance-Unconstrained Regime is positively signed and statistically significant, meaning when Congress is unconstrained (both the pivotal legislative actors and the Court prefer a legislative change to the status quo), the likelihood of an override is increasing in the distance between the status quo and the closest pivotal legislative actor. If Congress acts strategically, then the coefficient for Ideological Distance-Constrained Regime should be indistinguishable from zero and smaller than the coefficient for Ideological Distance-Unconstrained Regime. The coefficient on Ideological Distance does not statistically differ across the two regimes, and the coefficient on Ideological Distance is positive when Congress is constrained. Both results indicate that Congress does not act strategically, meaning it does not avoid a legislative override when the Court is likely to reject it. This suggests that Congress is motivated by position-taking goals rather than the policy effects of its override decisions.

Finally, we hypothesize that Congress acts on its preferences regardless of the legal basis on which the Court decides a case. Some scholars hypothesize that the Court uses constitutional interpretation when it fears possible congressional retaliation for a decision. The assumption they make, and that we question, is that Congress is less likely to act on its preferences in response to a constitutional decision. The results in Table 3 support our expectation, showing that there is no statistically distinguishable difference in the effect of Ideological Distance between statutory-based decisions and other cases. The positive and statistically significant coefficient on Ideological Distance indicates that Congress is more likely to override statutory decisions the further ideologically removed it is from the judicial status quo. The interaction terms show that the effect of Ideological Distance does not differ for either constitutional or common law decisions. What is more, the coefficient for Ideological Distance for constitutional and common law decisions is, respectively, 3.47 and 5.73 (and each is statistically significant). The Court may, as some suggest (e.g., Reference KingKing 2007), attempt to insulate its decisions by using constitutional review, but our data show that this tactic is not successful—if Congress ideologically disagrees with a Court decision, it is more likely to override it irrespective of whether it is a statutory or constitutional decision. Thus, regardless of the legal basis of a case, Congress is more likely to override a decision the further removed it is from the preferences of pivotal legislative decision makers.Footnote 21

Conclusion

Congress and the Supreme Court interact in a SOP framework as each attempts to shape policy. While the broader congressional politics literature provides convincing empirical evidence that legislative preferences have a significant effect on members' votes and the passage of legislation (e.g., Reference Poole and RosenthalPoole and Rosenthal 2007), no systematic evidence demonstrates that legislative overrides of Supreme Court opinions result from congressional preferences. This lack of empirical support exists despite the widespread application of a spatial modeling approach to understand Congress–Court relations, which assumes that overrides occur when Court decisions are ideologically distant from Congress. Our first goal was to show, consistent with existing spatial models in the literature, that Congress is more likely to pass laws overriding Supreme Court decisions the further ideologically removed a decision is from the legislative gridlock interval.

Our statistical results, for the first time, demonstrate that Congress overrides Court decisions the further ideologically removed a decision is from them. A two standard deviation shift around the mean of the ideological distance of Congress from a Court decision increases the likelihood of an override by 66.4 percent. This result indicates that Congress takes notice of the policy import of a Court decision and is more likely to reject those it dislikes on ideological grounds. We therefore provide evidence in support of a core part of SOP models, showing Congress does indeed respond to Court decisions based on its preferences. This result is important because it confirms a fundamental component of nearly all SOP explanations of the relationship between Congress and the Court. Future studies can now be confident that their assertion that legislative preferences influence overrides is on a strong empirical footing.

We further demonstrate that Congress does not act strategically by avoiding legislative overrides when the Court is likely to reject them. The implication is that Congress is motivated by position-taking goals rather than the ultimate effect of its policy actions and the SOP. That is, our data suggest that Congress cares more about the short-term gains from overriding legislation (e.g., passing the legislation for electoral purposes) than the ultimate shape of the policies it chooses to override. This result suggests that the Court may, at least when it concerns the ultimate effect of override legislation, have greater influence on the ultimate location of public policy. Of course, this conclusion is tempered by the fact that Congress and the Court rarely disagree about whether the status quo should be altered; Congress wishes to override a Court decision preferred by the Court only 2.5 percent of the time in our data. As Reference DahlDahl (1957) famously declared, the Court is not often out-of-step with the elected branches, and as a result, Congress and the Court tend to agree on the desirability of previously decided Court cases.

Finally, we show that the effect of ideological distance matters for all types of Court decisions, including constitutional ones. Thus, while the Court may, as some suggest (e.g., Reference KingKing 2007), attempt to insulate its decisions from congressional override by using constitutional interpretation, it appears that this tactic does not work. When Congress is ideologically distant from a Court decision, regardless of whether the decision is based on constitutional, statutory, or common law interpretation, it is more likely to override it. This result is new to the literature, and it means subsequent studies cannot exclusively focus on statutory cases.

What is the respective role of Congress and Supreme Court in the American political system? Our study, while focusing on one aspect of the SOP relationship between these two American political institutions, provides evidence regarding this important question. First, and consistent with studies going back to Reference DahlDahl (1957), we show that the pivotal decision makers in Congress generally share the ideological viewpoint of the Court. Consequently, these two decision-making bodies rarely disagree about the outcomes of previously decided Court cases. The implication is that one should be careful not to overstate the potential conflict between them, as they often agree on policy.

Second, while Congress has a number of institutional advantages when it comes to the SOP game, our results suggest that one of the advantages the Court has flows from Congress' tendency to favor position-taking goals over long-term policy goals when deciding whether to override the Court. Since Congress does not rationally anticipate the Court—it does not avoid legislative overrides that the Court is likely to strike down—the Court has a possible advantage in the SOP relationship. Most often, Congress' position-taking focus results because of electoral reasons. That is, Congress overrides Court decisions with which it disagrees because doing so gives current legislators an electoral advantage. An example of such position taking occurred in 1989 with the passage of legislation to override Texas v. Johnson (1989). In this decision, the Court ruled that flag burning was a protected form of expression under the First Amendment. Congress quickly passed override legislation—making it a crime to destroy an American flag—even knowing that the legislation was likely to be struck down by the Court. In U.S. v. Eichman (1990), the Court held that the override legislation was unconstitutional because it violated the Free Expression Clause of the First Amendment. In short, Congress was likely more concerned with the electoral benefits from the passage of override legislation than the ultimate policy outcome resulting from the interplay between the two branches of government. Put another way, studies of Congress–Court relations must keep in mind that Congress does not have the last move, and given electoral motivations, it may, under some conditions, not care if the Court strikes down legislation. This may, at times, give the Court a previously unrecognized advantage in the setting of policy.