Introduction

The site of Pauli Stincus is situated in the reclaimed Terralba wetlands on the south-eastern shores of the Gulf of Oristano in west-central Sardinia. The landscape comprises extensive sand dunes that overlie substantial clay deposits, resulting in rapidly draining soils of variable depth over a fertile substratum of fluvial origins. Before reclamation and lowering of the water table, the low-lying dune valleys became marshy during the rainy winter months (Ruiz et al. Reference Ruiz, Carmona, Gómez Bellard and van Dommelen2018). In Classical Antiquity, between the fourth century BC and the fifth century AD, the Terralba wetlands were densely settled by farming households that occupied numerous homesteads carefully positioned on dune ridges and higher ground to the east. Two of these farms were excavated in 2007 and 2010 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 General view of the modern field at Pauli Stincus, and a geomorphological overview map of the Terralba district (photograph by P. van Dommelen; geomorphological map courtesy of J. Ruiz).

Fieldwork at Pauli Stincus

The toponym Pauli Stincus (‘rush bog’) refers to the depression at the foot of a sand dune that turned waterlogged when groundwater levels rose in winter. On the top of the dune, the remains of a medium-sized Punic rural settlement were first recorded in the 1990s, and were systematically documented through surface artefact collection and geophysical survey in 2004 (van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen2006). When the site was excavated in 2010, a narrow trench was dug to explore the extent of the outer farmyard, and to examine the stratigraphic sequence of aeolian and fluvial deposits. This revealed a buried plough soil in the section (Díes Cusí et al. Reference Díes Cusí, van Dommelen and Gómez Bellard2011; Nicosia et al. Reference Nicosia, Langohr, Carmona González, Gómez Bellard, Modrall, Ruiz Pérez and van Dommelen2013; Figure 2). Augering in later years demonstrated that this buried soil horizon extended over a much larger area, at a depth of approximately 0.6m below the modern surface.

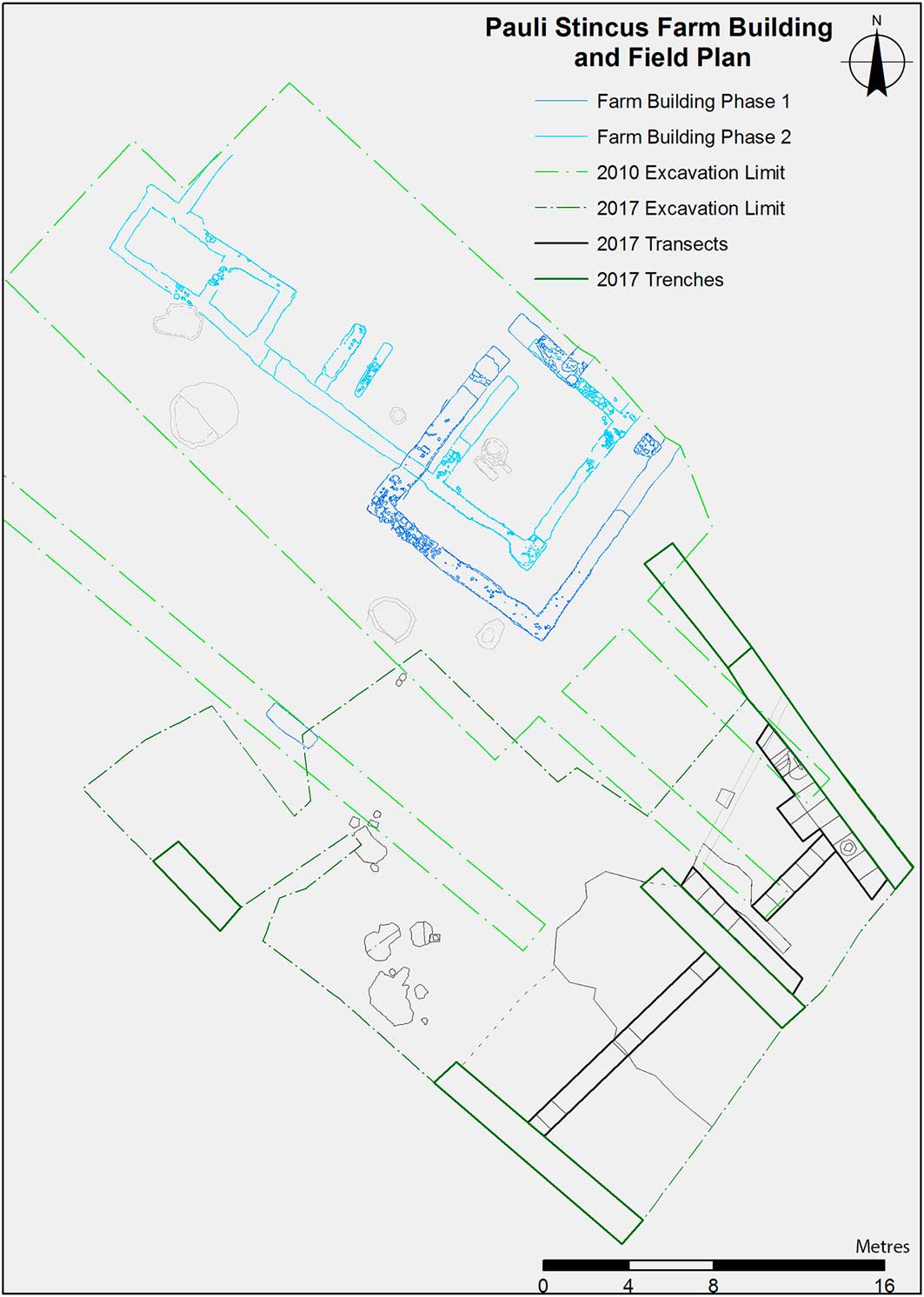

Figure 2 Combined plan of the excavated farmstead (2010) and the agricultural field (2017) at Pauli Stincus (figure by E. Díes Cusí & M. Naglak).

The buried plough soil at Pauli Stincus offered a rare opportunity to investigate a Mediterranean agricultural field, very few of which have been excavated extensively (Vera Rodríguez & Echevarría Sánchez Reference Vera Rodríguez and Echevarría Sánchez2013; Arnoldussen & van der Linden Reference Arnoldussen and van der Linden2017). Furthermore, the direct association with an excavated homestead promised the even more unusual opportunity to contextualise the field in its cultural setting (Figure 2).

We excavated one large (modern) field in October 2017. We began by defining an approximately 250m2 area that included where augering had shown the ancient plough soil to be present (Figure 2), but that did not substantially overlap with the 2010 excavation. As the depth of the buried soil horizon was already known (Nicosia et al. Reference Nicosia, Langohr, Carmona González, Gómez Bellard, Modrall, Ruiz Pérez and van Dommelen2013), the overlying deposits were removed mechanically. Three 1m-wide south-east- to north-west-running trenches (A-B-C) were mechanically excavated through the ancient plough soil to expose it in section (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Views of the buried plough soil as documented in 2010 (top), and of the 2017 north-east section of the excavated area (bottom). As highlighted, the plough soil is clearly visible at the base of the sections (photographs by C. Nicosia & P. van Dommelen).

Excavating the ancient plough soil

As the trench sections showed the extent of the ancient plough soil, an area of 20×10m was carefully excavated by hand to expose its surface. Although it proved impossible to distinguish a field boundary to the south-west, the general impression was that nevertheless, around trench B, the plough soil was much diminished, perhaps merging with a natural soil horizon. On the western side, the ploughed field was clearly demarcated by a linear greyish-black fill—possibly a backfilled ditch (labelled 2008 in Figure 4). From the sections, it was clear that the ancient field continued beyond the excavation area to the north-east and south-east (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Plan of the 2017 excavated area, including the mechanically excavated trenches (A-B-C) and the transects of hand-excavated squares (1-2-3-4) (figure by M. Naglak).

Having thus delimited the ancient agricultural field to an approximately 8×9m rectangle in the north-west corner of the excavation area, we excavated the plough soil itself by hand in adjoining 1×1m squares that lined up in four transects (Figure 4: transects 1–4). We plotted every find, recorded all features, dry-sieved all sediments and wet-sieved 20l samples. Transects 1 and 2 yielded many finds and features, the latter comprising mostly regularly shaped pits. It was also evident that virtually all finds were clustered in the area identified as the agricultural field; our initial interpretation was therefore corroborated (Figure 5). In addition to the flotation samples, five large soil columns were retrieved from the north-eastern and south-western sections for thin-section, granulometric and geochemical analyses.

Figure 5 Plan of the 2017 excavated area, showing the distribution of all finds (figure by M. Naglak).

Finds

In total, 412 ceramic—including 34 diagnostics—and 13 obsidian fragments were recovered, weighing 7.63kg in total (Figure 6). The obsidian mostly consists of small flakes. The bulk of the pottery comprises coarse wall fragments, but there are also nine fine ware sherds (Campanian Black Gloss). The fragments suggest a chronology spanning from the third to second centuries BC, which coincides with the mid fourth- to late second-century BC occupation of the farmstead. The majority of ceramic finds are in a coarse fabric known as ‘Riu Mannu A’, which was produced locally between the fifth and first centuries BC (van Dommelen & Trapichler Reference van Dommelen and Trapichler2011). The abraded nature of the sherds suggests that they may be regarded as ‘off-site’ pottery that was spread over the field during manuring. Sherd density may indicate the intensity of use of the field. The various pits imply that the field was in use over a prolonged period.

Figure 6 Ceramic finds drying in the field (photograph by P. van Dommelen).

Conclusions

While forthcoming analytical results will expand and refine our understanding of this site and Punic agricultural practices, we can already confidently confirm that we have revealed approximately 100m2 of an ancient, ploughed agricultural field, which was cultivated intensively in the third and second centuries BC.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Massimo Casagrande, Massimiliano Pilloni and Sandro Perra, without whom the excavation would never have happened. We also thank the regional Soprintendenza and the Italian Ministry of Heritage and Culture for granting permission to excavate. Fieldwork and laboratory analyses are supported by Brown University (IBES—Institute at Brown for Environment and Society) and the Spanish Ministerio de Cultura (grant BBAA2017-2).