Commissioning of most NHS services in England is effected by approximately 150 local primary care trusts spread over ten regional health authorities. Specialised services for rare diseases are commissioned by the National Specialist Commissioning Team (NSCT) of the Department of Health. A specialised service is defined in law as a service that covers a planning population (catchment area) of more than a million people. Each primary care trust contributes some of its budget to funding specialised services.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) 1 describe a six-stage model of stepped care, based on severity of the condition. It is recommended that adolescents and adults with the most severely impaired and resistant conditions receive either specialist out-patient or in-patient treatment, consisting of evidence-based psychological and drug treatments, delivered by experienced clinical teams. Few centres in England have expertise and experience in the intensive treatment of refractory OCD/BDD. The services available are listed in Table 1. A full description of these services can be found elsewhere. Reference Drummond, Fineberg, Heyman, Kolb, Pillay and Rani2 These specialised services developed in London and the South East due to the particular interests of a number of lead clinicians, all of whom have developed their services over more than 15 years.

Table 1 Services available for severe, enduring, complex obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)

| Type of service | Where available | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adult | ||

| Advice | All centres | Any potential referrer is welcome to contact any of the consultant psychiatrists providing these services for advice on medication and approaches to treatment. This can be via telephone or email |

| Out-patient | Hertfordshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust | |

| South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust | ||

| South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust |

||

| Home-based therapy | South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust |

Therapists will visit the patient in their own home anywhere in the UK and will work with the patient in collaboration with local services. Medication will be reviewed and a CBT programme implemented |

| Hertfordshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust | ||

| Residential treatment | South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust | This is for patients who need more intensive CBT but who cannot manage home-based therapy and do not require 24-hour nursing care |

| In-patient care | South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust |

12-bedded dedicated unit specialising in OCD/BDD for those patients who require 24-hour nursing care because of risk to self or others or due to inability to self-care |

| Hertfordshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust | Two beds on an adult psychiatry ward for patients requiring treatment under a section of the Mental Health Act 1983 or specialist psychopharmacology treatment and CBT, and who require 24-hour nursing care because of risk to self or others or due to inability to self-care |

|

| Priory Hospital, North London | Patients requiring treatment under a section of the Mental Health Act 1983 or patients with BDD |

|

| Child and adolescent | ||

| Out-patient (can be combined with home-based therapy) |

South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust | |

| In-patient care | Priory Hospital, North London | Patients requiring in-patient treatment |

CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy.

Historically, access to these services had been patchy due to the funding constraints of primary care trusts and different priorities in different geographical areas. In response, the services mentioned above decided collaboratively to invite the Department of Health to coordinate and fund a comprehensive and highly specialised service dedicated to treating those patients who are most severely disabled by these disorders. From 1 April 2007, the Department of Health, via the NSCT, agreed to commission and fund a national service for patients with the most profound OCD/BDD who have failed all previous treatments (including home-based treatments) provided by regional specialists. This agreement covers all patients in England. Separate arrangements exist for Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, whereby each referral is examined on an individual basis to ensure that local available resources are used fully. In Scotland, there is an advanced interventions service based at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, which is funded by the national services division of NHS National Services Scotland. This service offers treatment for resistant OCD as well as depression on an out-patient and in-patient basis. There is some considerable cross-referral between this service and the nationally commissioned services of England outlined in this paper. In England, to ensure that those patients who are the most severely ill were targeted for treatment, the NICE guidance level 6 severity was defined as shown in Appendix 1.

Appendix 1 Criteria for treatment by the nationally commissioned services

Basic criteria for all services

| Criteria | Comments |

|---|---|

| YBOCS >30 (or pro-rata equivalence for BDD) | Indicates severe/profound OCD symptoms |

| Two previous unsuccessful trials of serotonin reuptake inhibitor drugs (SRIs; clomipramine and selective SRIs (SSRIs)) |

British National Formulary-approved doses for a minimum of 3 months each |

| Augmentation of SRIs with other appropriate medication (usually dopamine blockers) |

For a minimum of 3 months |

| Two previous unsuccessful treatments with cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy for OCD from an accredited cognitive-behavioural therapist |

This should include graded exposure and self-imposed response prevention and one of the trials should normally have been performed in the home environment (or wherever symptoms are maximal) |

Additional criteria for in-patient treatment

To be eligible for an in-patient bed with 24-hour nursing care, individuals will usually demonstrate one or more of the following:

danger to self: usually through self-neglect such as failure to eat or drink, rather than suicidality

danger to others: usually due to impulsivity rather than overt acts of violence

self-neglect not life-threatening but serious: for example, incontinence of urine and faeces

other factors which, in combination with a variety of factors, may mean in-patient treatment is preferable:

unable to get out of bed and dressed in less than 3 h

inability to attend any appointments in the morning

severe disruption of sleep/wake cycle

complicating comorbid diagnosis such as psychotic disorder or history of anorexia.

Since 2007, there has been considerable activity by the services to ensure equitable access to the services for all patients with the most profound, refractory OCD. This has involved a variety of oral presentations both around the UK and at national services and letters written to all psychiatrists in England and to all the commissioners. We therefore decided to audit the referrals from different geographical regions in England and to compare the rate of referral and uptake of different treatments for these patients, to determine whether and how usage of the NSCT OCD service varies according to place of residence.

Method

All referrals made to the nationally commissioned services for England were recorded during the financial year of 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012. Records were kept of the demographic data including age, gender and diagnosis as well as the geographical origin of the referral. In addition, the severity of the OCD or BDD symptoms were assessed using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) for patients with OCD Reference Goodman, Price, Rasmussen, Mazure, Delgado and Heninger3 and the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for BDD (YBOCS-BDD) for those with BDD. Reference Phillips, Hollander, Rasmussen, Aronowitz, DeCaria and Goodman4 Because the YBOCS is scored out of a maximum of 40 and the YBOCS-BDD out of a maximum of 48, patients with BDD had the YBOCS-BDD score divided by 12 and multiplied by 10 to ensure all scores of severity were equivalent. For all patients treated as out-patients or with home-based therapy, the number of hours of treatment was recorded.

All data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 14 for Windows.

Results

Referrals from different regions

From 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012, 191 patients were referred to the NSCT service for OCD and BDD. These patients comprised 89 (46.6%) females and 102 (53.4%) males, with an average age of 36.9 years (range 11-79, s.d. = 14.6) and with an average YBOCS score of 33.3 (range 28-40, s.d. = 4.3). The diagnoses of the patients treated are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Diagnoses of patients treated by national obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) services in 2011/2012

|

n (%) (n=191) |

|

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| OCD | 123 (64) |

| BDD | 9 (5) |

| OCD and BDD | 6 (3) |

| OCD and Axis I disorder | 44 (23) |

| OCD and Axis II disorderFootnote a | 7 (4) |

| Treatment | |

| Advice | 19 (10) |

| Out-patient treatment | 83 (44) |

| Home-based therapy | 18 (10) |

| Residential | 19 (10) |

| In-patient treatment | 42 (22) |

| Refer to other specialised service | 9 (5) |

a Please note that for child and adolescent services, disorder refers to learning disability/developmental disorder rather than personality disorder in adults.

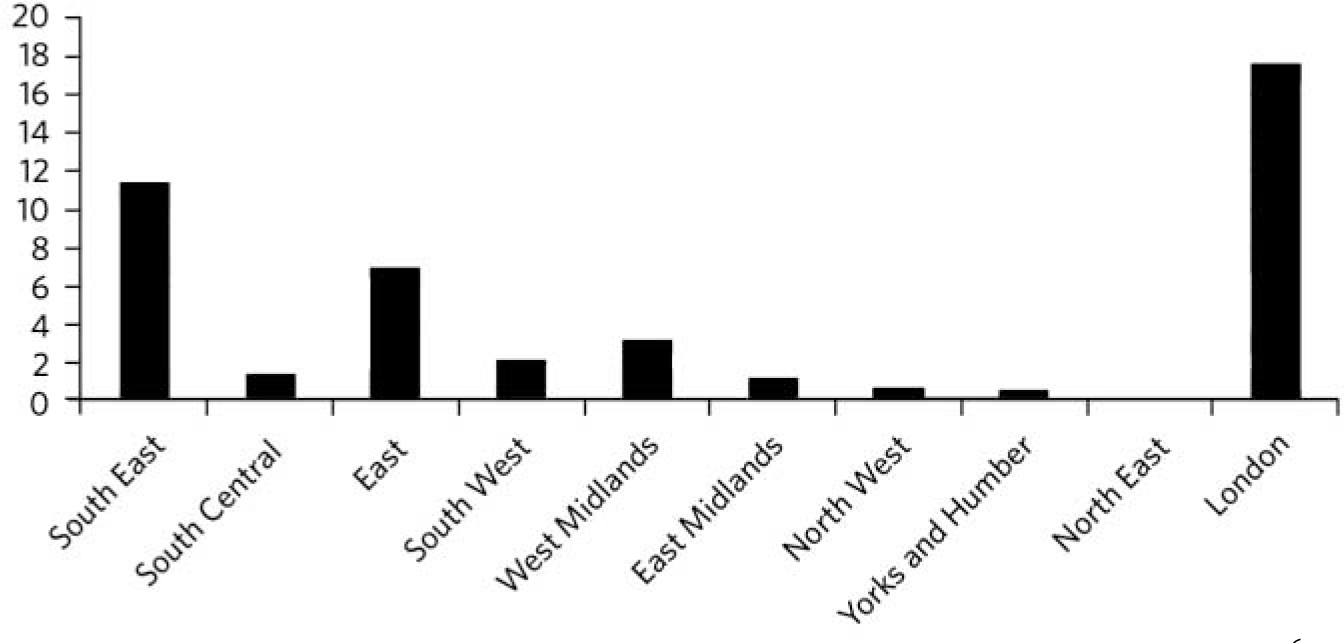

Dividing the referrals into the ten health authorities in England the overall number of referrals from each region is shown in Fig. 1. The greatest number of patients referred derive from London and the South East quadrant of the country. Patients from outside London and south-eastern regions would be expected to be less likely to attend for out-patient treatment but the rate of home-based therapy, residential treatment and in-patient treatment may be expected to be more evenly spread. The data were therefore reanalysed excluding out-patients (Fig. 2). This still shows a preponderance of patients from London and the south east of England but with a slightly greater spread of geographical referrals.

Fig 1 Overall number of referrals from each of the ten regions in 2011/2012.

Fig 2 Overall number of referrals from each of the ten regions excluding those treated as out-patients but including those treated by home-based therapy.

As there is a slight variation in the population in each of the ten regions, a more accurate picture was obtained by dividing the number of referrals from each region by the total population in the area to produce the referral rate. This was multiplied by 106 (Fig. 3).

Fig 3 Referral rate (number of referrals from each region divided by population of the region and multiplied by 106).

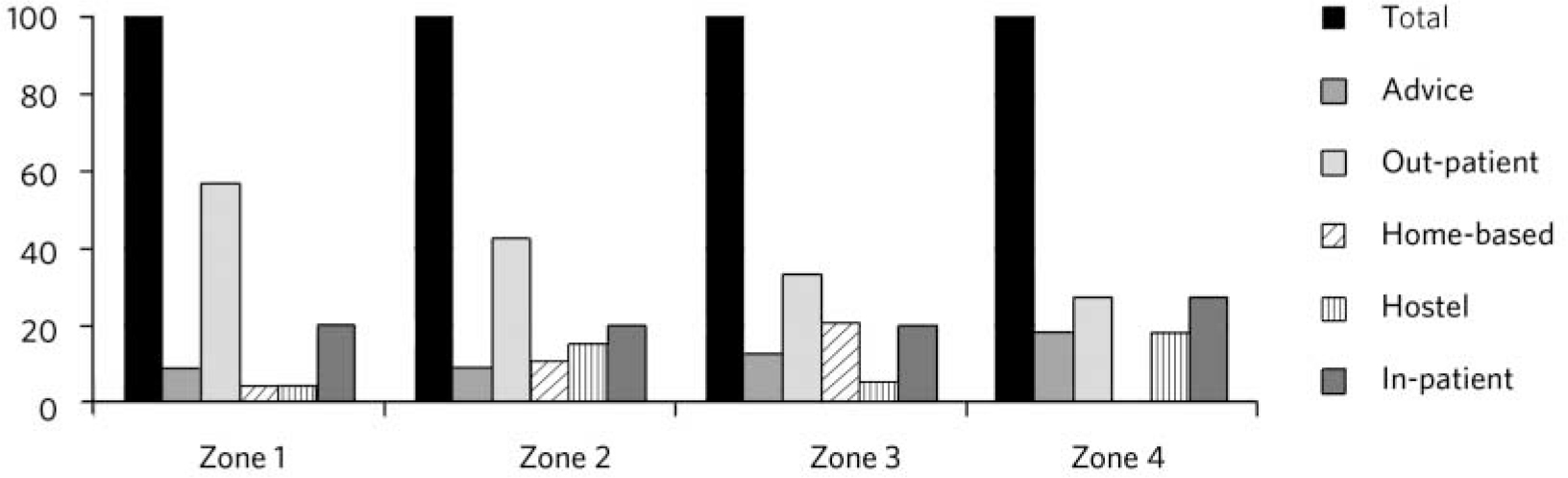

It can be seen that London and the South East still refer more patients than other areas, with the North West, North East and Yorkshire/Humber having the lowest rate of referrals per head of population. The ten referring authorities were divided into four zones depending on the distance from London (Appendix 2). The number of patients as a percentage of referrals from that zone treated in each way is shown in Fig. 4. Owing to the smaller number of patients treated from Zones 3 and 4 this is shown as a percentage of total referrals.

Fig 4 Percentage of patients from four geographical zones and type of treatment delivered.

Appendix 2 The four zones

| Zone | Distance from London, miles |

|---|---|

| Zone 1 (Greater London) | - |

| Zone 2 (South east coast; East of England and South Central) | Up to 150 |

| Zone 3 (South West; West and East midlands) | 150-250 |

| Zone 4 (North West; Yorks and Humber and North East) | 250 |

Types of treatment offered to patients from different regions

Figure 4 shows that patients from London and the South East are more likely to be offered out-patient treatment; home-based treatment was most likely to be offered to patients living in Zone 3 (150-250 miles away; South West, West Midlands and East Midlands). In-patient treatment remained fairly constant across all areas (presumably due to the severity of the condition requiring 24 h care). Residential treatment (without 24 h nursing cover) was less likely to be offered to patients from London and the South East.

Analysis comparing patients treated with out-patient compared with in-patient treatment demonstrated that those with a higher YBOCS score were more likely to be offered more intensive treatments. The average YBOCS score for out-patients was 31.7 (range 30-38, s.d. = 4.9); home-based treatment was 34.4 (range 30-38, s.d. = 2.81); residential hostel treatment was 33.8 (range 30-38, s.d. = 2.3) and for in-patients was 35.3 (range 30-40, s.d. = 3.3). The difference in severity between those treated as out-patients and in-patients was found to be significant (t-test, P<0.009).

Examining those treated with out-patient or home-based therapy, it was found that out-patient treatment was more likely to be offered to patients nearer to London (chi-squared test, P<0.0009). Home-based therapy is not related to distance from London (chi-squared test, P = 0.3220), although there remains an overall lack of referrals from the North of England. For all patients treated by the service as out-patients or by home-based treatment, the average number of hours (excluding assessment) is 17.7 h per patient (range 1-55, s.d. = 11). When number of out-patient and home-based treatment hours was compared for geographical distance from London, it was found that patients further from London were likely to receive as many hours of treatment as patients from nearer to London (chi-squared test, not significant).

Discussion

Overall we demonstrated that there was a significant geographical variation in patients referred to a specialised OCD/BDD service for those individuals with severe, treatment-refractory OCD and BDD. This could either be because of there being fewer patients requiring this level of intervention outside the South East of England or due to lack of knowledge of the services or an unwillingness to refer patients far from home. It would seem unlikely that there are fewer patients outside the South East of England requiring such specialised intervention.

It is also notable that some areas seem to send more referrals than others. This variation in referral rates may reflect variation in the distribution of interested clinicians and/or low referral rates could represent the availability of high-quality local services that compete with NSCT referral. Alternatively, low referral rates may represent failure to recognise and refer patients with severe OCD to appropriate resources. Our data did not allow us to analyse this at the current time. It is, however, likely that there are a large number of people with the most profoundly disabling OCD and BDD who are not receiving treatment. Most surveys of specialised services for OCD and BDD seem to suggest that most patients wait almost 20 years from first diagnosis to receiving highly specialised treatment. Reference Drummond5-Reference Boschen, Drummond, Pillay and Morton8

Treatment, even with this most difficult and treatment-refractory group of patients, is however remarkably successful, demonstrating average improvements in YBOCS and other measures of OCD symptomatology of approximately a third Reference Drummond5-Reference Boschen, Drummond, Pillay and Morton8 and with these changes remaining after treatment termination. Reference Drummond5 It thus seems unlikely that referrers are unwilling to refer elsewhere and seems more likely that the problem lies with their knowledge of the availability of the service. It would seem logical that this is due to the specialist clinics all being in the South East of England.

The low rate of referral from outside London and the South East could be tackled in the following ways.

-

• Ensuring referrers are aware of the availability of specialised treatment for this chronically ill and highly disabled patient group by direct letter to each potential referrer. Letters were sent individually addressed to all psychiatrists included in the Medical Directory in 2009. This had little, if any, appreciable effect. Letters have also been sent to all commissioners informing them of the availability of services.

-

• Talks at national conferences attended by potential referrers. Talks have been given at the annual conference of the Royal College of Psychiatrists describing the services in 2008 and 2011.

-

• Involvement of the media to raise awareness. The nationally commissioned services have been involved in encouraging the media to promote the treatment of OCD and BDD. In the past this has included multiple magazine and newspaper articles, radio and television appearances. Evening television seems to produce the most response, with a recent television programme featuring one of the services resulting in a spate of enquiries from healthcare professionals the next day. The effect of these events tend, however, to be short-lived, with enquiries reducing over a few days.

-

• Involvement in patient groups. All of the clinical directors of the services have been involved in meetings for the three main patient groups: Triumph over Phobia, UK (TOP UK), OCD Action and OCD-UK. Many patients and relatives find out information about services in this way and subsequently urge their mental health teams to refer them to a specialist service.

-

• Papers describing the availability of the service in publications read by potential referrers. Several papers about the service have appeared in academic, peer-reviewed publications, including The Psychiatrist, and more generally read publications.

-

• Setting up satellite clinics for patients in various parts of the UK. Although therapists have travelled throughout the UK in order to work with local community mental health teams and in-patient units for joint working with individual patients, there have not been any satellite clinics operating to date. This would seem to be the next logical step and would have the advantage that local clinicians may become interested in the work while involved in such a venture, which could ensure a wider geographical spread of expertise in the future. Indeed, other nationally commissioned services such as treatment for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome operate in this way, with clinics in both North West London and Manchester.

There is little or no systematic research on how to improve referrals to specialist mental health services. The general concepts that have been deployed in other areas of medicine are largely educational, for example working with general practitioners and other referrers, and providing information via service-user/voluntary sector groups. The national specialist OCD services collaborate closely with the national OCD charities mentioned earlier, OCD Action (www.ocdaction.org.uk), OCD-UK (www.ocduk.org) and TOP UK (www.topuk.org), all of whom have several projects aimed at informing health professionals and providing advocacy for patients.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.