1 Introduction

The study behind donors’ reluctance to cover running costs with their donation money – known as overhead aversion – is well-documented in the literature, (Reference BowmanBowman, 2006; Meer, 2014; Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al., 2014; Reference Gneezy, Keenan and GneezyGneezy et al., 2014; Reference Portillo and StinnPortillo & Stinn, 2018; Behavioural Insights Team, 2019; Reference Baron, Szymanska, Oppenheiemer and OlivolaBaron & Szymanska, 2011; Reference MacAskillMacAskill, 2016; Reference Caviola, Schubert and GreeneCaviola et al., 2021). However, this narrative might fuel the perception of overheads as “wasteful spending”. Ultimately, charities need to spend on overheads to hire skilled staff and have good infrastructure to fulfil their mission (Reference Caviola, Schubert, Teperman, Moss, Greenberg and FaberCaviola et al., 2020). Thus, to drive effective giving, donors should direct their attention towards cost-effectiveness rather than levels of overhead (Reference SingerSinger, 2015; Reference Caviola, Schubert, Teperman, Moss, Greenberg and FaberCaviola et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, donors often base their allocation decisions on easy-to-evaluate information about operating costs (Reference Bazerman, Loewenstein and WhiteBazerman et al., 1992; Reference Baron, Szymanska, Oppenheiemer and OlivolaBaron & Szymanska, 2011). Building on Hsee’s (1996) evaluability hypothesis, Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014) call this phenomenon the evaluability bias and define it as “the tendency to weight the importance of an attribute in proportion to its ease of evaluation, rather than based on criteria that are deemed as more relevant after reflection” (p. 304). In the context of altruistic decision-making, Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014) did four studies to test for evidence of the evaluability bias. In one of them, they asked their recruited participants from MTurk how much they would be willing to donate to two hypothetical charities that saved humans. The charities were presented with information on administration expenses and cost-effectiveness. Participants were shown either Charity A with high overhead and high effectiveness (separate evaluation), Charity B with low overhead and low effectiveness (separate evaluation), or both (joint-evaluation). When presented in isolation, donations were higher to Charity B. In contrast, joint-evaluation contributions were higher to the more effective Charity A. Thus, the authors provide evidence that when people are given a reference point (presenting both charities side by side), they become more concerned with effectiveness and hence become de-biased.

The present article replicates Study 1 by Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014), and extends the original design by including charities that save animals. This extension comes as a result of the perception that animals suffer less, have lower cognitive capacity than humans, and are valued less than humans (Reference Caviola, Schubert, Teperman, Moss, Greenberg and FaberCaviola et al., 2020, 2019; Reference Liebe and JahnkeLiebe & Jahnke, 2017; Reference Johansson-StenmanJohansson-Stenman, 2018). Thus, are donors less sensitive to overhead in the case of animals?

I expected that, even in the case of animal charities, the overhead ratio is an easier attribute to evaluate than cost-effectiveness. When evaluated jointly, cost-effectiveness is an easier attribute to evaluate than the overhead ratio.

2 Data and Method

2.1 Subjects

250 UK subjects with a mean age of 32 years (SD=11.68) were recruited through Prolific (Reference Palan and SchitterPalan & Schitter, 2018; Reference Chandler, Paolacci, Peer, Mueller and RatliffChandler et al., 2015) against a remuneration of £7.50/hr in return for their participation. In the pre-registration stage, I planned to exclude participants based on two attention checks and incompletion.Footnote 1

2.2 Research Design

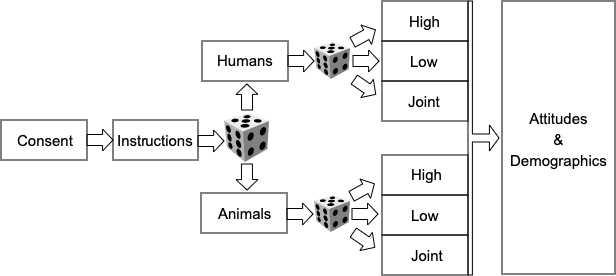

I used a between-subjects design similar to Hsee (1996), Erlandsson (2021), and Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014) over an online survey in Qualtrics (see Appendix 5.3.1). Upon entry, subjects were first presented with an information sheet and asked for consent. Following this, subjects were randomly allocated into one of two studies: Humans or Animals, and one of three treatments in equal numbers (see Figure 1).Footnote 2 The charities across both studies were perfectly identical, the only difference being that those in the Humans study dealt with saving human lives, whereas those in Animals saved animal lives.Footnote 3 Participants’ donation decisions were hypothetical, but part of their amounts would be transferred to real charities.

Figure 1: Procedure Diagram.

In accordance with ethical guidelines, participants were presented with information text on the study and asked for their consent. If subjects did not consent to participation, then they were redirected to Prolific; if they consented, they were taken to the instruction block. Here, participants were reminded that their hypothetical donation amounts would translate into real-world impact as 5% of all responses were donated to the Malaria Consortium and Animal Charity Evaluators.Footnote 4 The instructions included the following statements: “You will now be asked to think about a hypothetical scenario in the charitable giving domain. You will be asked to allocate donation amounts. Your donation amounts will have a real-world impact as a portion of your donations will be donated to charity.” Next, participants were asked to write that they have read the instructions, acting as a prime (Reference Dolan, Hallsworth, Halpern, King, Metcalfe and VlaevDolan et al., 2012), and serving as the first attention check of the study. Subsequently, subjects were taken to the main experimental manipulation which followed that of Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014) and Hsee (1996). 125 UK subjects were assigned to Humans with a mean age of 32 years (SD=12.13). Of these, 2 failed at least one attention check. A further 125 UK subjects were assigned to Animals with a mean age of 33 years (SD=11.16). One participant was excluded because they failed one attention check.

Subjects were randomly assigned to an experimental group and prompted to allocate an amount between £0 and £100 to each charity (similar to Reference Caviola, Everett and FaberCaviola et al., 2019). In the first two treatment groups High and Low, participants were shown either one of the two charities in isolation, with their respective attributes: cost-effectiveness and administrative expenses (see Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al., 2014).Footnote 5 The questions were presented as follows:

High overhead/High effectiveness “Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £60 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £40, 5 human [animal] lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 5 human [animal] lives with an overhead ratio of 60%. How much would you be willing to donate to this charity?”

Low overhead/Low effectiveness “Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £5 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £95, 2 human [animal] lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 2 human [animal] lives with an overhead ratio of 5%. How much would you be willing to donate to this charity?”

Joint Evaluation “Charity A: Out of a donation of £100, the charity spends £60 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £40, 5 human [animal] lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 5 human [animal] lives with an overhead ratio of 60%. Charity B: Out of a donation of £100, the charity spends £5 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £95, 2 human [animal] lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 2 human [animal] lives with an overhead ratio of 5%. How much would you be willing to donate to each charity?"

After being presented with information about administrative expenses, effectiveness, and overhead ratios, subjects were asked to indicate their hypothetical donation amounts restricted with an endowment of £100.Footnote 6 Similar studies on the evaluability hypothesis (such as Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al., 2014; Reference HseeHsee, 1996) used ranges from $10 to $50 or $100 to $500, implying that my range (£0 to £100) is broadly comparable.Footnote 7 Information presented was adjusted accordingly for consistency. Finally, participants were presented with a seriousness check (Reference Aust, Diedenhofen, Ullrich and MuschAust et al., 2013), and general demographic questions to gauge sample representativeness.

3 Results

3.1 Humans

3.1.1 Is the overhead ratio easier to evaluate than cost-effectiveness in human charities? (H1)

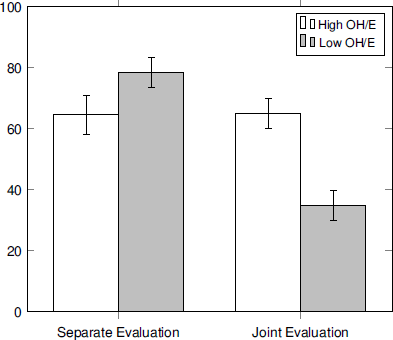

Concerning the question of whether donors to human charities tend to weigh the importance of an attribute in proportion to its ease of evaluation, Figure 2 shows their average donations. Donations in the separate evaluation condition are shown in the left-hand panel. When evaluated separately, independent sample t-tests revealed that subjects donated significantly more to the Low overhead/effectiveness charity (M=78.6, SD=32.5) than they did to the High overhead/effectiveness charity (M=64.6, SD=41.4; t(83)=–1.72, p=.045). To test whether this held when both charities were presented jointly, I report donations in joint-evaluation on the right-hand panel in Figure 2. In this case, subjects donated significantly more to the High overhead/effectiveness charity (M=65.1, SD=30.9) than they did to the Low overhead/effectiveness charity (M=34.9, SD=30.9; paird t-test [t(39)=3.10, p=.002). Thus, donors showed a preference for the Low overhead/effectiveness charity when presented in isolation, whereas when evaluated jointly, donors donated more to the High overhead/effectiveness charity. This observation supports Hsee’s (1996) preference reversal (t(120)=4.53, p=.001), i.e., preferences change when given a reference point (Reference HseeHsee, 1998; Reference Hsee, Loewenstein, Blount and BazermanHsee et al., 1999).Footnote 8. Furthermore, the results lend support for the hypothesis that donors find overhead to be an easier attribute to evaluate than effectiveness, confirming the existence of the evaluability bias observed by Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014).

Figure 2: Average Donations (£) in separate evaluation versus joint evaluation where OH/E denotes overhead/effectiveness. Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

3.2 Animals

3.2.1 Is the overhead ratio easier to evaluate than cost-effectiveness in animal charities? (H2)

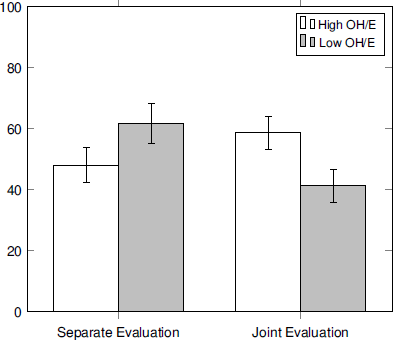

In Animals, I attempt to answer the same question as in Humans to probe the question of whether the evaluability bias holds in the context of animal charities. Figure 3 shows average donation amounts across separate evaluation and joint-evaluation conditions. A priori, I suspected that donors in the Animals study would be equally sensitive to overhead ratios as donors in the Humans study. In fact, I find support for the hypothesis that donors to animal charities find the overhead ratio to be more evaluable than effectiveness, albeit at a weaker level of significance. In separate evaluation, an independent sample t-test revealed that donors donated more to the Low overhead/effectiveness charity (M=61.6, SD=41.7) than they did to the High overhead/effectiveness (M=48.0, SD=36.9; t(83)=–1.4, p=.078 two tailed). Once again, donors exhibited unstable preferences when the evaluation mode was changed, demonstrating preference reversal (t(119)=3.04, p=.003). A paired sample t-test for the joint-evaluation condition revealed that donors donated more to the High overhead/effectiveness charity (M=58.7, SD=34.7) than to the Low overhead/effectiveness charity (M=41.3, SD=34.7; t(40)=1.61, p=.058).

Figure 3: Average Donations (£) in separate evaluation versus joint evaluation where OH/E denotes overhead/effectiveness. Error bars represent standard errors of the means.

4 Discussion

The present article carried out a replication of one of the four studies by Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014). It tested for evidence of the evaluability bias when giving to human charities, and extended it by investigating whether the same effect can be applied to animal charitable giving. This was carried out by using the same scenario as in Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014), and eliciting hypothetical donation amounts from participants. By way of recap, analysis of means finds that (i) the overhead ratio is an easier attribute to evaluate than cost-effectiveness in human charities, and (ii) when evaluated jointly, cost-effectiveness is more accessible than the overhead ratio. In the case of animal charities, the same effect was observed but at marginal significance.

In the first study dealing with saving human life, the results indicate that contrary to much of the literature, donors are not preoccupied with overhead per se (Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al., 2014). Instead, donors find the overhead ratio easier to evaluate than cost-effectiveness when they do not have a reference point. When judging their options in isolation, donors donated more money to the low overhead charity, but donors’ preferences reversed when the two charities were presented jointly (Reference HseeHsee, 1996; Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al., 2014; Reference ErlandssonErlandsson, 2021; Reference Hsee and ZhangHsee, 2010). In joint-evaluation, donors donated more money to the more cost-effective charity, despite the higher overhead. The most likely explanation behind this is that donors are given a reference point to compare with and are effectively de-biased against overhead (Reference Berman, Barasch, Levine and SmallBerman et al., 2018). In the second study, the picture is less clear. When dealing with animal lives, results indicate weak evidence in favour of the evaluability bias. Similar to the first study, donors donated more money to the charity with low overhead when evaluated in isolation. Then, when evaluated jointly, donors’ preferences shifted towards the more effective charity. However, the results were only marginally significant. The likely reason behind the weaker effect is that cost-effectiveness information was given in terms of animal lives saved in general. In other words, the experiment employed a generic animal category, therefore donors’ attitudes towards animal life might have varied based on their imagined animal category.

4.1 Limitations

In such experimental methods, a fundamental shortcoming is the issue of external validity. There may be little connection between responses here and those in real life. Subjects’ responses were hypothetical and might differ from real world behaviour. To partly mitigate this, participants were told that their donations had a real impact as I donated a portion of their responses to real charities.

There are also issues endemic to my experiments. First, the presentation of cost-effectiveness and overhead likely increased the salience and relative evaluability of both attributes. In the field, donors are presented with particular characteristics and a vast array of stimuli that might drive their donations (Reference Berman, Barasch, Levine and SmallBerman et al., 2018). A second issue is that the Animals study did not refer to a particular kind of animal species. In the experiment, a generic animal category was used, possibly accounting for the diminished evaluability bias. A third issue is that despite being sufficiently-powered, the sample sizes are quite small. Fourth, when evaluating charities jointly, participants could have been motivated by fairness concerns in their donation allocations (Reference Li and HseeLi & Hsee, 2019; Reference Erlandsson, Lindkvist, Lundqvist, Andersson, Dickert, Slovic and VästfjällErlandsson et al. 2020; Reference Hsee, Rottenstreich and XiaoHsee et al., 2005).

4.2 Future Research

There is merit in extending the research agenda to explore whether the evaluability bias continues to hold in different contexts for different causes. More practically, research has thus far operated in a hypothetical setting and possibly real world behaviour might differ, especially when donors have more than two options to choose from. In light of this, future research would benefit from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the field where donors are observed in a real-world environment. Secondly, there is a demonstrable relationship between levels of overhead, effectiveness and donations. However, research is less clear about the extent to which donors would be willing to trade-off overhead for effectiveness (Mott et al., 2020; Reference Johansson-StenmanJohansson-Stenman, 2018; Reference Benjamin, Heffetz, Kimball and Rees-JonesBenjamin et al., 2014). Third, future research can look at the animals question using specific animal species, and employing larger sample sizes.

5 Conclusion

In this study, I empirically investigated the evaluability bias in charitable animal giving. Based on previous research by Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and KahaneCaviola et al. (2014), I hypothesised that the evaluability bias would be replicated in a UK sample recruited via Prolific. Secondly, I extended this claim by hypothesising that the evaluability bias will be as strong for animal charities as for human charities. Results showed that the evaluability bias indeed affects decisions about human charitable giving. However, in the case of charitable animal giving, the effect was marginal.

Appendix

5.1 Full Experimental Materials

The following is a transcription of the Qualtrics survey sent out to participants.

5.1.1 Introduction & Consent

Dear Participant,

This study is about charitable giving.

Before you decide to participate, please read the following instructions to confirm that you agree to take part. This is a requirement by the University.

Your participation will consist of a simple electronic questionnaire and will take approximately 5 minutes of your time. This project has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the London School of Economics and Political Science. There are no risks associated with this study. If you have any questions, you may contact the Research Ethics Manager via research.ethics@lse.ac.uk.

Do not hesitate to ask any questions or forward your concerns about the study either before, during or after your participation by contacting me on [ ]. Please note that your responses are treated anonymously and will be used for research purposes only. You will be paid upon completion of the survey. If you wish to withdraw your consent at any point, you may do so without giving any reason and without any consequences.

Please indicate below whether you would like to participate in this study.

-

Yes, I have read and understood the consent above and would like to participate in this study.

-

No, I do not wish to participate in this study.

End of Block: Consent Block

5.1.2 Preamble

Thank you for agreeing to participate in this study.

You will now be asked to think about a hypothetical scenario in the charitable giving domain. You will be asked to allocate donation amounts.

Your donation amounts will have a real-world impact as a portion of your donations will be donated to charity

In the text box below, kindly write "I read the instructions":

End of Block: Preamble

5.1.3 Study 1 - Humans

Treatment 1 - Charity A

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £60 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £40, 5 human lives are saved.

In other words, the charity saves 5 human lives with an overhead ratio of 60%.

You may choose to donate any amount between £0 and £100. Your donation amount cannot exceed £100.

How much would you be willing to donate to this charity?

Treatment 2 - Charity B

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £5 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £95, 2 human lives are saved.

In other words, the charity saves 2 human lives with an overhead ratio of 5%.

You may choose to donate any amount between £0 and £100. Your donation amount cannot exceed £100.

How much would you be willing to donate to this charity?

Treatment 3 - Joint Evaluation

Imagine that you want to donate to charity and you are presented with the following two charitable organisations.

Charity A

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £60 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £40, 5 human lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 5 human lives with an overhead ratio of 60%.

Charity B

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £5 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £95, 2 human lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 2 human lives with an overhead ratio of 5%.

You may choose to donate any amount between £0 and £100. Your donation amount cannot exceed £100.

How much would you be willing to donate to each charity?

End of Block: Study 1 - Humans

5.1.4 Study 2 - Animals

Treatment 1 - Charity A

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £60 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £40, 5 animal lives are saved.

In other words, the charity saves 5 animal lives with an overhead ratio of 60%.

You may choose to donate any amount between £0 and £100. Your donation amount cannot exceed £100.

How much would you be willing to donate to this charity?

Treatment 2 - Charity B

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £5 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £95, 2 animal lives are saved.

In other words, the charity saves 2 animal lives with an overhead ratio of 5%.

You may choose to donate any amount between £0 and £100. Your donation amount cannot exceed £100.

How much would you be willing to donate to this charity?

Treatment 3 - Joint Evaluation

Imagine that you want to donate to charity and you are presented with the following two charitable organisations.

Charity A

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £60 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £40, 5 animal lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 5 animal lives with an overhead ratio of 60%.

Charity B

Out of a donation of £100, a charity spends £5 on administrative expenses. With the remaining £95, 2 animal lives are saved. In other words, the charity saves 2 animal lives with an overhead ratio of 5%.

You may choose to donate any amount between £0 and £100. Your donation amount cannot exceed £100.

How much would you be willing to donate to each charity?

End of Block: Study 2 - Animals

5.1.5 Speciesism Scale

Below are a series of statements with which you may either agree or disagree. For each statement, please indicate the degree of your agreement/disagreement. Remember that your first responses are usually the most accurate.

[Answers were on a 7-point scale: Strongly agree; Agree; Somewhat agree; Neither agree nor disagree; Somewhat disagree; Disagree; Strongly disagree.]

-

Please click scale point 1 to confirm that you are paying attention.

-

Morally, animals always count for less than humans.

-

Humans have the right to use animals however they want to.

-

It is morally acceptable to keep animals in circuses for human entertainment.

-

It is morally acceptable to trade animals like possessions.

-

Chimpanzees should have basic legal rights such as a right to life or a prohibition of torture.

-

It is morally acceptable to perform medical experiments on animals that we would not perform on any human.

End of Block: Speciesism Scale

5.1.6 Demographic Questions

You have now reached the final part of the study. The following questions are required for further data analysis. Kindly answer as accurately as possible

What is your sex?

-

Male

-

Female

-

Other

What is your age?

____________________________________________________________________

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

-

Primary School

-

Secondary School

-

Sixth Form

-

Diploma

-

Bachelor’s Degree

-

Master’s Degree

-

Doctorate

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

-

England

-

Wales

-

Scotland

-

Northern Ireland

-

Other

What was your religion at birth?

-

No religion

-

Christian

-

Buddhist

-

Hindu

-

Jewish

-

Muslim

-

Sikh

-

Any other religion

End of Block: Demographic Questions

5.1.7 Religiosity and Political Beliefs Scales

How religious do you consider yourself to be?

-

• 1 Not at all religious

-

• 2

-

• 3

-

• 4 Moderately Religious

-

• 5

-

• 6

-

• 7 Extremely Religious

Please answer the following questions about your political beliefs.

[Answers were on a 7-point scale: Very Liberal; Liberal; Somewhat Liberal; Moderate; Somewhat Conservative; Conservative; Very Conservative.]

-

How economically liberal or conservative are you?

-

Please click scale point 1 to confirm that you are paying attention.

-

How socially liberal or conservative are you?

-

End of Block: Religiosity and Political Beliefs Scales

5.1.8 Seriousness Check

It would be very helpful if you could indicate whether you have taken part seriously, so that your answers can be used for scientific analysis, or whether you were just clicking through the survey

-

I have taken part seriously.

-

I was just clicking through, please throw my data away.

End of Block: Seriousness Check