Impact statement

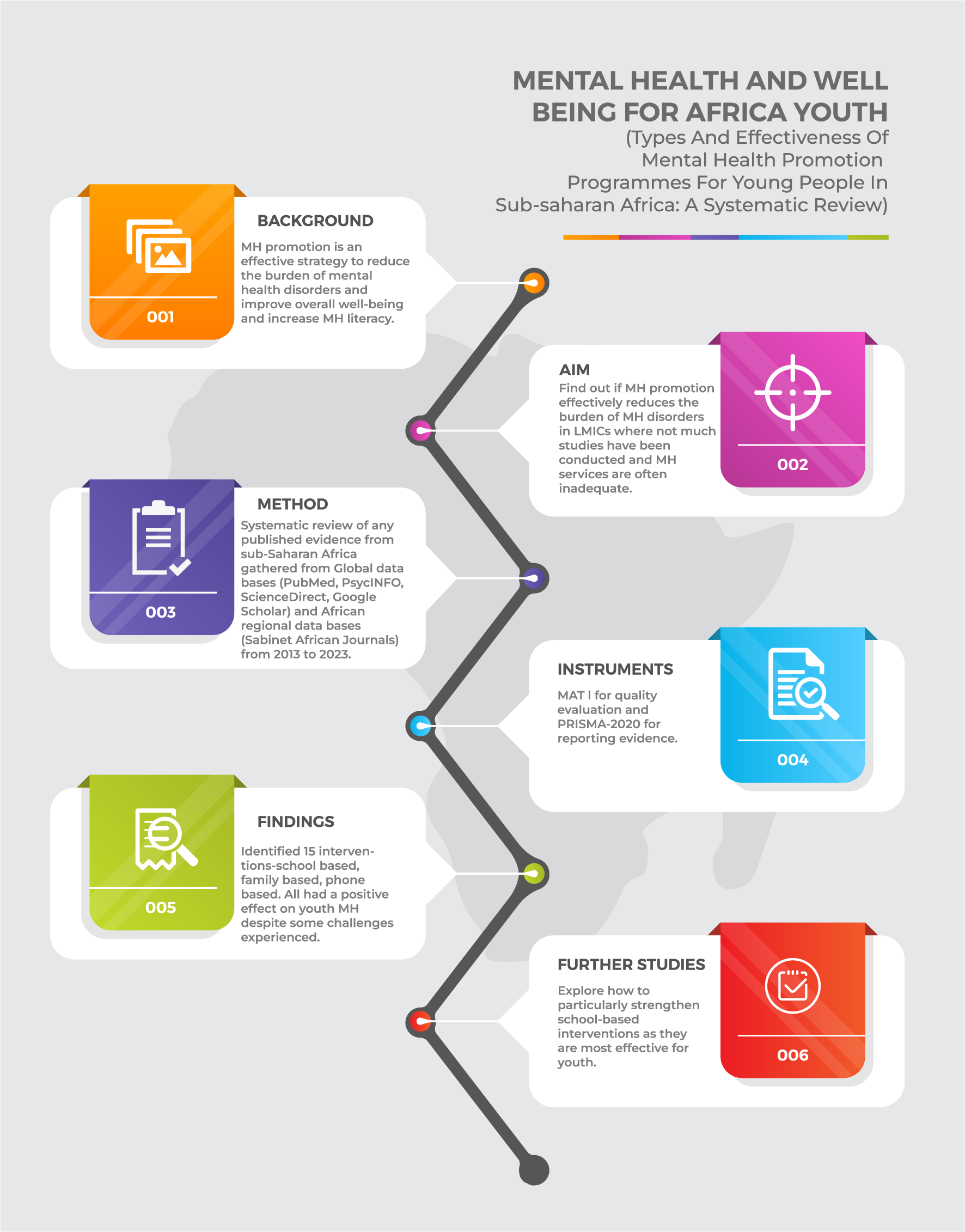

Recent studies show high levels of mental health problems among young people in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Despite the high prevalence of mental health problems and the resultant consequences for young people, the provision of mental health services in the region remains poor. Mental health promotion is an effective intervention that can help prevent the onset of serious mental problems. This systematic review synthesised the available published primary evidence from SSA on the types and effectiveness of mental health promotion programmes for young people. Our review shows that school-based interventions increased mental health literacy among young people. In addition, young people who took part in school-based intervention programmes tended to be more self-assured and confident. Our findings also point to the importance of family-based interventions as these have the potential to improve relationships between young people and their caregivers. This review highlights the need for more evidence on the effectiveness of school- and family-based intervention programmes for young people in SSA.

Background

Mental health refers to the state of well-being of individuals and encompasses an individual’s ability to cope with the diverse stressors the individual faces (Herrman and Jané-Llopis, Reference Herrman and Jané-Llopis2012). In defining mental health, Herrman and Jané-Llopis (Reference Herrman and Jané-Llopis2012) further added the concept of mental health promotion, which is a global initiative to improve and sustain mental well-being across different populations. The promotion of mental health incorporates the prevention of mental illnesses before their onset. Herrman and Jané-Llopis (Reference Herrman and Jané-Llopis2012) hold the view that mental health promotion requires an inclusive knowledge of determinants of mental health and mental problems with the sole purpose of preventing mental illnesses or promoting mental well-being for individuals.

According to a report by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022), mental health problems have been on the increase largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has created a crisis for mental health globally. This report further estimates that there was a sharp rise in anxiety and depression by more than 25% during the first year of the pandemic. Earlier in 2019, the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) showed that mental health problems remained among the top 10 leading contributors to the burden of disease globally, with anxiety and depressive disorders emerging as some of the most prevalent conditions (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic estimated the global prevalence of mental health problems as follows: depression (28.0%), anxiety (26.9%), post-traumatic stress symptoms (24.1%), stress (36.5%), psychological distress (50.0%) and sleep problems (27.6%; Nochaiwong et al., Reference Nochaiwong, Ruengorn, Thavorn and Wongpakaran2021). Although mental health problems are prevalent globally for the general population, the situation is especially concerning for children and young people who are more vulnerable to developing these conditions (Mabrouk et al., Reference Mabrouk, Mbithi, Chongwo and Abubakar2022; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Araya, Chowdhary and Weiss2008a; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Flisher, Nikapota and Malhotra2008b).

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where more than 70% of the population is comprised of children and young people (Awad, Reference Awad2019), the outlook is even more dire. For instance, a recent systematic review by Jörns-Presentati et al. (Reference Jörns-Presentati, Napp, Dessauvagie and Suliman2021) found significantly high levels of mental health problems among adolescents with anxiety disorders estimated at 40.8% followed by depression at 29.8%, and emotional and behavioural problems at 21.5%. This high level of mental health problems among young people in SSA is further exacerbated by numerous psychosocial stressors, such as chronic poverty, prolonged exposure to war and violence and the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the region (Jörns-Presentati et al., Reference Jörns-Presentati, Napp, Dessauvagie and Suliman2021).

Despite the higher prevalence of mental health problems and the resultant consequences for young people, their families and the community, mental health services in SSA remain poor (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Araya, Chowdhary and Weiss2008a; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Flisher, Nikapota and Malhotra2008b; WHO, 2020). Many countries in this region have poor mental health infrastructure (WHO, 2020), with deficient or non-existent mental health policies to address the mental health challenges faced by the communities (Sodi et al., Reference Sodi, Modipane, Oppong Asante and Khombo2021). The scarcity of mental health services (WHO, 2020) and the relatively high burden of disease (Jörns-Presentati et al., Reference Jörns-Presentati, Napp, Dessauvagie and Suliman2021) call for the implementation of innovative, evidence-based and culturally relevant interventions to promote mental health among young people in the region.

Growing evidence shows that mental health promotion, which includes mental illness prevention interventions, is an effective strategy that can reduce the burden of mental disorders and improve overall well-being in both children and adults (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013; Castillo et al., Reference Castillo, Ijadi-Maghsoodi, Shadravan and Halpin2020; Mabrouk et al., Reference Mabrouk, Mbithi, Chongwo and Abubakar2022; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Zaki, Farid and Kaur2022; Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Ferré-Grau, Canut and Costa2022). Mental health promotion is an area of public health practice that seeks to empower people to achieve positive mental health by encouraging healthy behaviours and addressing the needs of those susceptible to experiencing mental health problems (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013). Based on the same concept of health promotion as articulated in the Ottawa Charter, mental health promotion advocates a population-based approach that seeks to build capacity in individuals and communities for well-being instead of focusing on ill health and the associated risks (WHO, 1986). In other words, such interventions tend to shift the focus from an individual to the broader community and the wider social determinants of mental health. Mental health promotion interventions, therefore, encourage broad public participation since they can be delivered in different settings, such as schools, the workplace and recreational centres (WHO, 2009). For instance, Santre (Reference Santre2022) pointed out that school-based mental health promotion programmes, such as social and emotional learning (SEL), mindfulness and positive psychology interventions, improve mental health, well-being and educational outcomes. A recent systematic review that sought to gather evidence on the cost-effectiveness of mental health promotion and prevention found that these interventions demonstrate good value for money when targeting children, adolescents and adults (i.e. Le et al., Reference Le, Esturas, Mihalopoulos and Engel2021). Apart from promoting high levels of mental well-being and preventing the onset of mental health conditions, mental health promotion also helps to increase levels of mental health literacy in society (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Ito-Jaeger, Perez Vallejos and Crawford2023; WHO, 2009; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang and Rhodes2021, Reference Zhang, Sunindijo, Frimpong and Su2023).

“Although there is evidence showing the effectiveness of mental health promotion, much of what is known about this field is informed by studies conducted in high-income countries” (Erskine et al., Reference Erskine, Baxter, Patton and Scott2017). A systematic review conducted more than a decade ago by Barry et al. (Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013) synthesised findings on the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people (aged 6–18 years) in school- and community-based settings in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Given the availability of more recent data, there is a need for current evidence about the effectiveness of such interventions in LMICs, particularly the sub-Saharan region where mental health services are often inadequate (WHO, 2020). In SSA, such efforts should prioritise young people who constitute a great majority of the population (Awad, Reference Awad2019).

Aim

The aim of this study was to synthesise the available published primary evidence from SSA on the types and effectiveness of mental health promotion programmes for young people.

Main questions

-

1. What types of mental health promotion programmes for young people have been implemented in SSA?

-

2. How effective are mental health promotion programmes for young people in SSA?

Methods

We used a systematic review due to its ability to synthesise studies that have been done on any topic in a more detailed, meticulous and rigorous research methodology (Caldwell and Bennett, Reference Caldwell and Bennett2020). The review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt and Brennan2021; see Figure 1). Global databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect and PsycINFO) and a regional database (Sabinet African Journals) were searched for data that were published between 2013 and 2023 without any design restrictions. This period was decided for the review in order to get the latest data on types of mental health promotion programmes for young people in SSA, including the effectiveness of these interventions. In this review, we adopted the WHO’s definition of young people as individuals aged 10–24 years (WHO, 2023). We performed a reference and hand search on Google Scholar. We used search items: (“mental health” OR “mental disorder” OR “mental illness”) AND (prevention OR “health promotion”) AND (Type OR typologies) AND (effective*) AND (“Central Africa” OR “Africa South of the Sahara” OR “West Africa” OR “Western Africa” OR “East of Africa” OR “Eastern Africa” OR “Southern Africa” OR “sub-Saharan Africa”). We included studies conducted in any of the countries within the SSA region, focusing on young people regardless of gender, religion or sexual orientation. We included clinical and non-clinical studies involving mental health promotion programmes. We considered primary studies that employed quantitative, trials, pilot, mixed methods research approaches and observational studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram flow.

Source: Page et al. (Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt and Brennan2021)

We relied on the reference manager, EndNote20, to record all the identified articles on databases. Authors, KR, FKM, DI, PW, SOD, UI, DF, PH, MB and PT were all involved in the process of screening articles for eligibility. When there was conflict, TS was responsible for resolving the conflict and finding consensus. Articles that met the inclusion criteria were appraised by FKM and KR using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). The articles that met the inclusion criteria are listed on the data chart (Annexure A, Table 3). We relied on the software Jamovi to determine the heterogeneity statistics of the selected studies (see Table 1). The p-value (<0.001), I 2 (99.26%) and H 2 (134.566) have higher values which indicate that there is substantial heterogeneity of the analysed data. We then applied narrative synthesis to discuss the types and effectiveness of mental health programmes that promote youth mental health in SSA.

Table 1. Heterogeneity statistics

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The attached Annexure B showcases the search history of the search. The search was conducted in 2023 and about 54,390 articles were found using PubMed, ScienceDirect, Sabinet African Journal, PSYCHINFO and Google Scholar (used for hand search, backward and forward search). Articles were then exported to EndNote, wherein duplicates were removed, and 41,816 articles were screened using title and abstract. Of the 41,816 articles which were screened, 47 articles were selected for full-text screening. In the end, a total of 16 studies conducted in 18 sub-Saharan countries were included in the final review (Figure 1). Detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in the data chart in Table 3 of Annexure A. Studies included in our review were drawn from Nigeria (n = 3), Rwanda (n = 1), Burundi (n = 1), Tanzania (n = 2), South Africa (n = 3), Kenya (n = 2), Burkina Faso (n = 1), Uganda (n = 1), Botswana (n = 1) and Malawi (n = 1). One of the 16 studies was a multi-country investigation that included Tanzania and Malawi. In terms of the study design, most of the included studies were either randomised control trials (n = 10) or quasi-experimental designs (n = 3). Other study designs included pre–post experimental design (n = 1), and mixed methods design (n = 2).

Types of intervention from included studies

In the analysed articles, we found that 16 different interventions categorised as family-orientated (n = 3), school-orientated (n = 8), peer-orientated (n = 4) and online-orientated interventions (n = 1) were used among youth in the SSA region. The family-orientated interventions included family strengthening intervention (FSI), VUKA family program and READY. Interventions that targeted learners in school were class-based intervention (CBI), school-based intervention, school-based educational intervention, school support intervention, school-based training programme on depression, living well post-intervention (life-skills intervention) and mental health teaching programme. Interventions that were peer-orientated were Sauti ya Vijana (SYV) intervention, Balekane EARTH programme, group-based intervention and intervention targeting grief and depression. Finally, for online-oriented methods, we found that researchers used mobile phone-based mental health interventions.

The effectiveness of interventions

Effects on attitude, knowledge and behaviour

The study conducted by Atilola et al. (Reference Atilola, Abiri and Ola2022) in Nigeria reported that effect size (η2) was highest for knowledge (students: 0.07, p = 0.001; teachers: 0.08, p < 0.000) and least for attitude (students: 0.003, p = 0.002 teachers: 0.085, p = 0.06). In addition, Kutcher et al. (Reference Kutcher, Bagnell and Wei2015) conducted a study in Malawi and Tanzania and reported an effect size of d = 1.16 on knowledge which indicated that the training had a substantial impact on educators’ knowledge acquisition. Also, it was reported that the trial had a positive impact on attitudes towards mental health with an effect size of (d = 0.79). This demonstrates a large increase in educators’ positive attitudes and a decrease in stigmatising attitudes. Furthermore, Oduguwa et al. (Reference Oduguwa, Adedokun and Omigbodun2017) reported that attitude scores in the intervention group have an increase from 4.9 at baseline to 5.8 post-intervention (p = 0.004). Finally, McMullen and McMullen (Reference McMullen and McMullen2018) reported on prosocial attitudes/behaviours with a small effect size of, F(1,167) = 5.61, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.033, and connectedness with a large effect of, F(1,167) = 15.24, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.085. Bhana et al (Reference Bhana, Mellins, Petersen and McKay2014) did not have numeric numbers to report intervention effect size but also noted a general improvement in mental health and cited examples of improvement in attitude towards HIV treatment knowledge. In terms of behaviour, Thurman et al.’s (Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017) study reported that behaviour after intervention in adolescents was lower in the intervention group (p = 0.017, d = –0.31; Thurman et al., Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017).

Effects on perseverance, self-esteem and confidence

When assessing the intervention effect size, Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Ng, Kirk and Zahn2014) reported a significant improvement in children’s perseverance and self-esteem (6-month follow-up: d = 0.853, d = 0.853). Ismayilova et al. (Reference Ismayilova, Karimli, Sanson and Chaffin2018) also reported improvement in self-esteem at 12 months: small effect size Cohen’s d = 0.21 and improvement in self-esteem at 24 months: Cohen’s d = 0.21. In support, McMullen and McMullen (Reference McMullen and McMullen2018) reported medium effect sizes for general self-efficacy, F(1,167) = 19.66, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.106, and internalising problems, F(1,167) = 10.58, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.060. Finally, Kachingwe et al.’s (Reference Kachingwe, Chikowe, van der Haar and Dzabala2021) study established confidence by reporting the effect size of 0.098 on confidence and psycho-social well-being.

Effects on depressive, anxiety and trauma

Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Ng, Kirk and Zahn2014) reported reductions in symptoms of depression (6-month follow-up: d = −0.618, d = −0.618), anxiety/depression (6-month follow-up: d = −0.640, d = −0.640) and irritability (6-month follow-up: d = −0.788, d = −0.788). On the other hand, Ismayilova et al. (Reference Ismayilova, Karimli, Sanson and Chaffin2018) in a study conducted in Burkina Faso reported a reduction in depressive symptoms at 12 months: medium effect size Cohen’s d = −0.41, reduction in depressive symptoms at 24 months: Cohen’s d = −0.39. Thurman et al.’s (Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017) study had an effective size of (p = 0.009, d = –0.21) on depression. Again, Green et al (Reference Green, Cho, Gallis and Puffer2019) reported a moderate effect size of the intervention on depression among adolescent orphans in the study with −0.28, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.45 to −0.12. In terms of trauma symptoms, the intervention effect size reported by Ismayilova et al. (Reference Ismayilova, Karimli, Sanson and Chaffin2018)’s study indicated that there was a reduction in symptoms of trauma at 12 months: incidence risk ratio (IRR) = 0.62.

Effects on grief and resilience

The waitlisted group of participants reported an effect size for intrusive grief (p = 0.000, Cohen’s d = –0.21) and complicated grief (p = 0.015, d = –0.14; Thurman et al., Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017). Katisi et al.’s (Reference Katisi, Jefferies, Dikolobe, Moeti, Brisson and Ungar2019) study also reported small-to-moderate improvements in resilience and grieving among participants. For example, in the case of resilience, the effect sizes ranged from r = 0.10 to r = 0.14. In terms of grieving, effect sizes were reported as r = 0.03 to r = 0.41. The study reported that the overall resilience of the participants showed that males had slight improvement.

Effects on family communication outcome

Puffer et al (Reference Puffer, Green, Sikkema, Broverman, Ogwang-Odhiambo and Pian2016) reported positive outcomes on family communication, high self-efficacy for risk reduction skills and HIV-related knowledge and reduced high-risk behaviours.

Publication bias assessment

We applied a fail–safe N analysis to check for publication bias. The result in Table 2 shows that the fail–safe N is 129,365.000 with the p value at <0.001, which indicates that publication bias was avoided and suggests that the effectiveness of the analysed studies was robust and not dependent on the number of studies included in the analysis (see also funnel plot in Figure 2).

Table 2. Fail–safe analysis

Note: Fail–safe N calculation using the Rosenthal approach.

Figure 2. Funnel Plot.

Fail–safe analysis was done using the Rosenthal Approach (p < 0.001). From the funnel plot, there is an apparent symmetry which shows that publication biases have been avoided.

Discussion

In this review, we sought to determine the types and effectiveness of mental health programmes that promote mental health among young people in SSA. Such initiatives are a proven effective strategy to reduce the burden of mental illness among young people in the region, especially as studies have shown that timely interventions during this developmental period can help to reduce the risk of mental ill-health (Colizzi et al., Reference Colizzi, Lasalvia and Ruggeri2020; McGorry and Mei, Reference McGorry and Mei2018; Saxena et al., Reference Saxena, Funk and Chisholm2013) and increase the prospects of a healthy adulthood. To our knowledge, this is the first such systematic review on the effectiveness of mental health promotion programmes among young people specifically in SSA despite there being several such programmes in this region (Atilola et al., Reference Atilola, Abiri and Ola2022; Bella-Awusah et al., Reference Bella-Awusah, Adedokun, Dogra and Omigbodun2014; Thurman et al., Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017). This study thus builds on a previous systematic review by Barry et al. (Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013) that explored the effectiveness of youth mental health promotion interventions in LMICs. In that review, Barry et al. (Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013) established that school-based interventions have a positive impact on the mental health of adolescents as it improves their self-esteem. Betancourt et al. (Reference Betancourt, Ng, Kirk and Zahn2014) further found that as with school-based intervention, FSI and trickle-up intervention (Ismayilova et al., Reference Ismayilova, Karimli, Sanson and Chaffin2018) had a positive impact on the self-esteem of adolescents.

In addition, we found that school-based mental health interventions such as those conducted by Bella-Awusah et al. (Reference Bella-Awusah, Adedokun, Dogra and Omigbodun2014), Thurman et al. (Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017) and Atilola et al. (Reference Atilola, Abiri and Ola2022) improved the mental health literacy of young people. However, hitherto, no subsequent studies in SSA have explored the impact of the whole school approach interventions (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Clarke, Jenkins and Patel2013). This consequently leaves a gap as the whole-school approach has been reported to have a long-term impact on the mental well-being of adolescents than single-school interventions.

The findings by Bella-Awusah et al. (Reference Bella-Awusah, Adedokun, Dogra and Omigbodun2014), Thurman et al. (Reference Thurman, Luckett, Nice, Spyrelis and Taylor2017) and Atilola et al. (Reference Atilola, Abiri and Ola2022) are consistent with those of studies conducted by Amado-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Amado-Rodríguez, Casañas, Mas-Expósito and Martín2022) and Curran et al. (Reference Curran, Ito-Jaeger, Perez Vallejos and Crawford2023), which reported that mental health literacy interventions are effective in augmenting mental health knowledge and reducing stigma. This finding offers an important avenue to support the mental health of young people since previous studies have shown that young people in SSA have low levels of mental health literacy (Wadende and Sodi, Reference Wadende and Sodi2023). Young people with enhanced mental health literacy easily seek and effectively utilise professional mental health care for themselves and others (Colizzi et al., Reference Colizzi, Lasalvia and Ruggeri2020; McGorry and Mei, Reference McGorry and Mei2018; Saxena et al., Reference Saxena, Funk and Chisholm2013). Being able to actively seek mental health care is especially important when young people live in LMIC contexts characterised by destabilising forces such as conflict and poverty and related deprivation that easily predispose them to mental illness (Kieling et al., Reference Kieling, Baker-Henningham, Belfer and Rahman2011). Further, the limited capacity of such contexts (paucity of mental health care workers) and the stigma associated with the illness (Osborn et al., Reference Osborn, Venturo-Conerly, Arango and Rusch2021) underscore the importance of a young population that has high levels of mental health literacy.

In addition to the mental health interventions increasing related literacy among participating young people (Amado-Rodríguez et al., Reference Amado-Rodríguez, Casañas, Mas-Expósito and Martín2022; Curran et al., Reference Curran, Ito-Jaeger, Perez Vallejos and Crawford2023; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang and Rhodes2021; Reference Zhang, Sunindijo, Frimpong and Su2023), those who took part in intervention programmes exhibited increased self-assurance and confidence, which consequently had a positive impact on their mental health. It is therefore important to foster more of such interventions for the young people to ensure the future of SSA, where future leaders and the general society have the desirable emotional fortitude needed in their daily encounters.

Another finding from the study is that family-based intervention programmes had the capacity to strengthen family relations by improving the bond between young people and their caregivers. Unresolved mental health problems in young people continue into their adulthood negatively impacting their relationships, productivity and overall quality of life (Colizzi et al., Reference Colizzi, Lasalvia and Ruggeri2020; McGorry and Mei, Reference McGorry and Mei2018; Saxena et al., Reference Saxena, Funk and Chisholm2013). The importance of family and related care relationships for the continued health of young people as they grow into adulthood cannot be overstated. Several studies indicate that there is a positive link between supportive family relationships and mental well-being (Daines et al., Reference Daines, Hansen and Crandall2022; Chen and Harris, Reference Chen and Harris2019). Such positive supportive relationships are also essential especially when a young person is undergoing a mental health intervention program. They help the young person not to relapse during or after the programme ends (Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Sikkema, Broverman, Ogwang-Odhiambo and Pian2016). Therefore, there is a need to invest more in such programmes that bring young people and their families much closer to improving their mental well-being.

Although it is not possible to draw any conclusions based on one study, Mindu et al. (Reference Mindu, Mutero, Ngcobo, Musesengwa and Chimbari2023) suggested that mobile phone-based interventions could be another resource that can be used in mental health promotion programmes for young people. While mobile phone-based interventions may have the potential, it is also important to take into account the limitations of such an intervention due to challenges such as language barriers, limited privacy and such interventions being perceived as not user-friendly (Mindu et al., Reference Mindu, Mutero, Ngcobo, Musesengwa and Chimbari2023). Mobile phone coverage also remains a challenge for large swathes of populations in Africa. As estimated by GMSA state of mobile connectivity 2022, Africa has a 17% gap in coverage, and for the remaining 83%, there is a 61% usage gap where hundreds of millions are covered but not using the mobile internet (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2022).

Limitations, future directions and conclusion

This systematic review identified the types of mental health intervention programmes for young people in SSA, assessed their effectiveness and identified gaps in the existing literature while highlighting areas that may need further research. The strengths of this review include the wide range of databases we searched. We obtained evidence from international databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect and PsycINFO) and regional African databases (Sabinet African Journals). Additionally, we did not set any restrictions on study design which is also a strength of our review. However, a limitation of this review is that it comprised only manuscripts published between 2013 and 2023; hence, the findings may not be applicable to any other period. We also did not include manuscripts published in other languages apart from English, which could likely result in some relevant evidence being omitted by our review.

Future studies could explore how to further strengthen school-based interventions, particularly whole-school approaches for promoting mental wellbeing and illness awareness among young people. This is of importance as our review shows its potential to have a sustainable impact on the mental health of young people, particularly when their mental health literacy is improved. Additionally, family-based interventions could be further developed and employed as our review revealed their potential to improve relationships between young people and their caregivers, thus promoting healthier families and, subsequently, whole communities. In SSA, mobile phone platforms have the potential to be useful and cost-effective avenues for mental health interventions targeting young people due to the wide use of mobile telephones even in the remotest locations. Researchers should look for creative ways to minimise the perceived impediments to the use of mobile phone platforms among young people.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.153.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to this review are available within the published manuscript and its online supplements.

Author contribution

TS conceptualised the idea, wrote the original draft, reviewed all drafts, supervised the development of systematic review protocol, developed a search strategy for systematic review and served as guarantor for the contents of this paper. KR contributed to writing the original draft, developed search strategy for systematic review, contributed to writing original draft, performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed all drafts, reviewed and approved final draft. FKM wrote the original draft, developed search strategy for systematic review, performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed all drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. PW contributed to writing the original draft, performed preliminary literature search, reviewed all drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. DI contributed to writing the original draft, performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. SOD performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. DF performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. PH performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. UI performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. MB performed preliminary literature search, conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. DM conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft. SE performed preliminary literature search, reviewed and approved the final draft. TP performed preliminary literature search, reviewed and approved the final draft. DJ reviewed and approved the final draft. JYP reviewed and approved the final draft. TA reviewed and approved the final draft. ERB reviewed and approved the final draft. LG conducted edits for the drafts, reviewed and approved the final draft.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies. T.S. received funding from the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) and National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF) Grant number 150571.

Competing interest

None.

Ethics statement

We did not seek ethical approval from any ethics committee as this is a systematic review of available and accessible literature. We registered the protocol with PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42023434887).

Annexure A: Data extraction

Table 3. Data chart

Annexure B: Search history

Comments

The Editor-in-Chief

Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health

Please find enclosed our manuscript entitled: Types and effectiveness of mental health promotion programmes for young people in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review by Sodi et al. which we would like to be considered for publication in Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health. We believe that our paper will be of great interest to the readers of Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, more especially those focusing on youth mental health.

We confirm that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration in whole or in part by another journal. All authors have approved the manuscript, and agree that it be submitted to Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this paper.

Thank you for your consideration of the manuscript. We look forward to hearing from you at your earliest

convenience.

Yours sincerely

T Sodi