1. INTRODUCTION

Diodorus of Sicily composed a historical work unprecedented in its broad thematic and chronological scope. Besides the mythological narrative of both Greeks and barbarians (Books 1–6), his Universal History (Bibliothêkê) encompassed the vast history of the entire Oikumenê, from the Trojan War to the beginning of Caesar's Gallic War (Books 7–40). Of the original forty books, fifteen have been preserved (1–5, 11–20), while of the remaining twenty-five only fragments survive. As can be seen both from the fully and from the partially preserved books, one of the characteristics of Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê is a systematic use of prefaces. The opening main proem is the most elaborate in terms of length, content and style (1.1.1–1.5.3). It begins with a long topical praise of universal history as ‘the benefactor of the entire human race᾿ (1.2.2, transl. Oldfather) that is conveyed with remarkable enthusiasm and stylistic refinement (1.1.1–1.2.8). Besides this appreciation of historia as magistra uitae, it also contains various significant information, such as Diodorus’ motives for writing universal history (1.3), autobiographical details (1.4.1–5) and, finally, a chronological and thematic outline of the whole work (1.4.6–1.5.1).Footnote 1 Whereas the main proem refers to the Bibliothêkê as a whole, the lesser proems relate, in general, to particular books.Footnote 2 Accordingly, every preserved book from Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê (1b, 2–5, 11–20) comprises a preface that provides a summary of that book's content and, usually, places it within the framework of the whole work by mentioning the subject matter of the preceding book or books (1b for the first part of Book 1, 2–4, 11–15, 17–20).Footnote 3 Owing to these content summaries, Diodorus enables his reader to navigate within the enormous historical material and ensures the unity of the whole work.Footnote 4 Moreover, almost every lesser preface conveys further reflections on different themes (4–5, 12–20).Footnote 5 Following Margrit Kunz, we can divide these considerations into two main groups.Footnote 6 The first group consists of prefaces approaching general methodological and historiographical questions.Footnote 7 The second group addresses different moral and political ideas that, in contrast, relate more closely to the contents of particular books.Footnote 8 The same classification also applies to prefaces that are preserved in the fragmentary books of Diodorus.Footnote 9

In this paper I argue that one further preface belonging to the second group has been overlooked by scholarship. Of particular concern are two fragments that originally belonged to Book 34 (34/35.2.33 Sent and 2.25–6 Virt). These are to be found within the narrative of the First Slave Revolt in Sicily (135–132 b.c.).

The first fragment, 2.33 Sent (= Goukowsky 34, fr. 4),Footnote 10 contains a moral precept that admonishes slave-owners and rulers to treat their subjects gently in order to avoid both domestic disturbances of slaves and political upheavals of subjects:

ὅτι οὐ μόνον κατὰ τὰς πολιτικὰς δυναστείας τοὺς ἐν ὑπεροχῇ ὄντας ἐπιεικῶς χρὴ προσφέρεσθαι τοῖς ταπεινοτέροις, ἀλλὰ καὶ κατὰ τοὺς ἰδιωτικοὺς βίους πρᾴως προσενεκτέον τοῖς οἰκέταις τοὺς εὖ φρονοῦντας. ἡ γὰρ ὑπερηφανία καὶ βαρύτης ἐν μὲν ταῖς πόλεσιν ἀπεργάζεται στάσεις ἐμφυλίους τῶν ἐλευθέρων, ἐν δὲ τοῖς κατὰ μέρος τῶν ἰδιωτῶν οἴκοις δούλων ἐπιβουλὰς τοῖς δεσπόταις καὶ ἀποστάσεις φοβερὰς κοινῇ ταῖς πόλεσι κατασκευάζει. ὅσῳ δ’ ἂν τὰ τῆς ἐξουσίας εἰς ὠμότητα καὶ παρανομίαν ἐκτρέπηται, τοσούτῳ μᾶλλον καὶ τὰ τῶν ὑποτεταγμένων ἤθη πρὸς ἀπόνοιαν ἀποθηριοῦται⋅ πᾶς γὰρ ὁ τῇ τύχῃ ταπεινὸς τοῦ μὲν καλοῦ καὶ τῆς δόξης ἑκουσίως ἐκχωρεῖ τοῖς ὑπερέχουσι, τῆς δὲ καθηκούσης φιλανθρωπίας στερισκόμενος πολέμιος γίνεται τῶν ἀνημέρως δεσποζόντων.

Not only in the exercise of political power should men of prominence be considerate towards those of low estate, but also in private life all men of understanding should treat their slaves gently.Footnote 11 For heavy-handed arrogance leads states into civil strife and factionalism between citizens, and in individual households it paves the way for plots of slaves against masters and for terrible uprisings in concert against the whole state. The more power is perverted to cruelty and lawlessness, the more the character of those subject to that power is brutalized to the point of desperation. Anyone whom fortune has set in low estate willingly yields place to his superiors in point of gentility and esteem, but if he is deprived of due consideration, he comes to regard those who harshly lord it over him with bitter enmity. (transl. Walton, adapted)

The second fragment, 2.25–6 Virt (= Goukowsky 34, fr. 1), provides an excellent analysis of the economic and social causes of the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, presenting towards its end a rather controversial comparison with Aristonicus’ uprising in Asia:

ὅτι οὐδέποτε στάσις ἐγένετο τηλικαύτη δούλων ἡλίκη συνέστη ἐν τῇ Σικελίᾳ. δι’ ἣν πολλαὶ μὲν πόλεις δειναῖς περιέπεσον συμφοραῖς, ἀναρίθμητοι δὲ ἄνδρες καὶ γυναῖκες μετὰ τέκνων ἐπειράθησαν τῶν μεγίστων ἀτυχημάτων, πᾶσα δὲ ἡ νῆσος ἐκινδύνευσεν πεσεῖν εἰς ἐξουσίαν δραπετῶν, ὅρον τῆς ἐξουσίας τιθεμένων τὴν τῶν ἐλευθέρων ὑπερβολὴν τῶν ἀκληρημάτων. καὶ ταῦτα ἀπήντησε τοῖς μὲν πολλοῖς ἀνελπίστως καὶ παραδόξως, τοῖς δὲ πραγματικῶς ἕκαστα δυναμένοις κρίνειν οὐκ ἀλόγως ἔδοξε συμβαίνειν. (26) διὰ γὰρ τὴν ὑπερβολὴν τῆς εὐπορίας τῶν τὴν κρατίστην νῆσον ἐκκαρπουμένων ἅπαντες σχεδὸν οἱ τοῖς πλούτοις προκεκοφότες ἐζήλωσαν τὸ μὲν πρῶτον τρυφήν, εἶθ’ ὑπερηφανίαν καὶ ὕβριν. ἐξ ὧν ἁπάντων αὐξανομένης ἐπ’ ἴσης τῆς τε κατὰ τῶν οἰκετῶν κακουχίας καὶ τῆς κατὰ τῶν δεσποτῶν ἀλλοτριότητος, ἐξερράγη ποτὲ σὺν καιρῷ τὸ μῖσος. ἐξ οὗ χωρὶς παραγγέλματος πολλαὶ μυριάδες συνέδραμον οἰκετῶν ἐπὶ τὴν τῶν δεσποτῶν ἀπώλειαν. τὸ παραπλήσιον δὲ γέγονε καὶ κατὰ τὴν Ἀσίαν κατὰ τοὺς αὐτοὺς καιρούς, Ἀριστονίκου μὲν ἀντιποιησαμένου τῆς μὴ προσηκούσης βασιλείας, τῶν δὲ δούλων διὰ τὰς ἐκ τῶν δεσποτῶν κακουχίας συναπονοησαμένων ἐκείνῳ καὶ μεγάλοις ἀτυχήμασι πολλὰς πόλεις περιβαλόντων.

There was never a sedition of slaves so great as that which occurred in Sicily, whereby many cities met with grave calamities, innumerable men and women, together with their children, experienced the greatest misfortunes, and all the island was in danger of falling into the power of fugitive slaves, who measured their authority only by the excessive suffering of the freeborn. To most people these events came as an unexpected and sudden surprise, but to those who were capable of judging affairs realistically they did not seem to happen without reason. Because of the superabundant prosperity of those who exploited the products of this mighty island, nearly all who had risen in wealth affected first a luxurious mode of living, then arrogance and insolence. As a result of all this, since both the maltreatment of the slaves and their estrangement from their masters increased at an equal rate, there was at last, when occasion offered, a violent outburst of hatred. So without a word of summons tens of thousands of slaves joined forces to destroy their masters. Similar events took place throughout Asia at the same period, after Aristonicus laid claim to a kingdom that was not rightfully his, and the slaves, because of their owners’ maltreatment of them, joined him in his mad venture and involved many cities in great misfortunes. (transl. Walton)

To demonstrate that these fragments initially constituted a part of the preface to Book 34 (section 3), I will first analyse their narrative order within the respective Byzantine collections (section 3.1) and compare it with the synopsis of Photius (section 3.2). Furthermore, I will point out that their content is overlapping and interdependent (section 3.3). Finally, I will analyse the structure, phraseology and style of both fragments, comparing them to other prefaces of Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê (section 3.4). However, before starting the argumentation, a few words need to be dedicated to the Byzantine transmission of the Diodoran narrative of the First Slave Revolt in Sicily (section 2). This short recapitulation is necessary, as further arguments of this paper rely on it.

2. THE TRANSMISSION OF DIODORUS’ NARRATIVE ON THE FIRST SLAVE REVOLT IN SICILY

Diodorus’ narrative on the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, as it is available to us now, is the modern arrangement of fragments that are of uneven value. This is due to intermediate transmission by authors or excerptors from the Byzantine era who had different approaches to Diodorus’ text, both in terms of selection of material and in terms of methods of transmission.

Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople (ninth century a.d.), composed a paraphrase of Diodorus’ narrative in his voluminous Bibliothêkê (Codex 244, pages 384a–386b). His summary is our main source of information regarding the content and the structure of the narrative.Footnote 12 Photius demonstrates that the narrative originally belonged to Book 34 and most likely followed descriptions of other historical events in that book.Footnote 13 However, the obvious drawback of Photius’ summary is that it is only a summary. Thus it mirrors Photius’ subjective understanding of Diodorus’ text, his personal interests or even biases towards it.Footnote 14 It contains intrusions of new material in terms of language, style and content, and focusses only on the introductory part of the original narrative in which the causes and the beginning of the uprising are described (34/35.2.1–18 Ph – 135–134 b.c.). Thus he omits almost entirely the middle section of the narrative (2.19 Ph – 133 b.c.) and summarizes the end of the uprising in only a few paragraphs (2.20–4 Ph – 132 b.c.).Footnote 15

On the other hand, three Byzantine collections of excerpts (Constantinian collections, tenth century a.d.), De uirtutibus et uitiis, De sententiis and De insidiis pass down almost two dozen fragments from Diodorus’ narrative which are, for the most part, verbatim quotations.Footnote 16 However, dealing with these fragments entails several difficulties as well. They contain some minor changes in wording and syntax and occasionally convey obvious textual errors. They are all thematically limited to particular topics determined by the focus of the given collection. Moreover, Constantinian excerpts are preserved without any direct context. As a result, the original framework of many excerpts is barely reconstructable or completely uncertain. Finally, there is also the question of thematic and chronological relationship between excerpts from all three Constantinian collections, with two main auxiliary means to reconstruct their original order.

First, it is certain that Constantinian excerptors retained the narrative order of the fragments while excerpting them; thus the order of excerpts within a single Byzantine collection is not debatable.Footnote 17 Second, the relationship between the fragments of all three collections is partly determinable thanks to the paraphrase of Photius, which occasionally contains some overlapping phraseology with the Constantinian excerpts. These main auxiliary instruments were available to modern editors for reconstructing the original order of excerpts from Diodorus’ narrative of the First Slave Revolt. In what follows, the same auxiliary apparatus is used to examine whether the two fragments may be transferred in another position and, as a result, considered part of the preface to this book.

3. FR. 34/35.2.33 SENT AND FR. 2.25–6 VIRT AS PARTS OF THE PREFACE TO BOOK 34 – THE EVIDENCE

3.1 Narrative order of fr. 34/35.2.33 Sent and fr. 2.25–6 Virt in the Constantinian collections

The occurrence of a preface from Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê within the collections of Constantinian excerpts would not be surprising, since some proems from the lost books of Diodorus have been transmitted in that way (21.1.4a; 25.1.1, 2.1; 26.1.1–3; 32.2.1, 4.1–5; 37.1.1–6, 29.2–5 and 30.1–2 from the preface to Book 38?). However, the main precondition for considering any excerpts a part of a Diodoran preface is their appropriate position within the Constantinian collection. That means that they must occupy a position corresponding to the beginning of a book in Diodorus. In our case, given that the two fragments derive from two different collections, they need to precede all other excerpts from Book 34 respectively. Table 1 (columns 1 and 2) illustrates the position of the two fragments within the respective Constantinian collection.

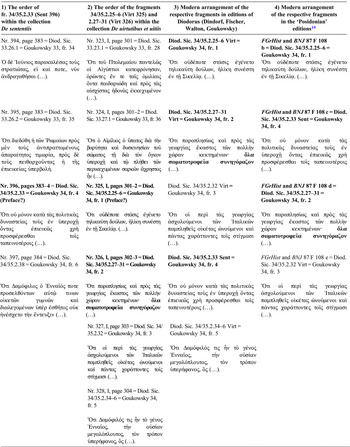

Table 1 The order of the two fragments within the Byzantine collections and modern editionsFootnote 18

Fragment 2.33 Sent derives from the collection De sententiis (Nr. 396, pages 383–4), into which Constantinian excerptors copied theoretical or moral reflections. Within this collection, it follows several excerpts that are not related to the narrative of the First Slave Revolt in Sicily. Moreover, modern editors unanimously attribute them to Book 33 (Nr. 394, page 383 = Diod. 33.26.1 = Goukowsky 33, fr. 34; Nr. 395, page 383 = Diod. Sic. 33.26.2 = Goukowsky 33, fr. 35). Yet it is indisputable that fr. 2.33 Sent initially belonged to Book 34 of the Bibliothêkê. It clearly refers to the First Slave Revolt that Diodorus originally described in Book 34, as we know thanks to Photius. In addition, it is followed by another fragment from this narrative that depicts the infamous slave-owner Damophilus, who incited the slave uprising in Enna (Nr. 397, page 384 = Diod. Sic. 34/35.2.38 = Goukowsky 34, fr. 6). As a result, it is possible to conclude that fragment 2.33 is the first excerpt from Book 34 in the collection De sententiis.

Fragment 2.25–6 Virt is to be found, on the other hand, in the collection De uirtutibus et uitiis (Nr. 325, I, pages 301–2). Yet, similarly to fr. 2.33 Sent, it follows several excerpts that refer to different subject matters and all are considered to belong to Book 33 (Nr. 323, I, page 301 = Diod. Sic. 33.23.1 = Goukowsky 33, fr. 28; Nr. 324, I, page 301 = Diod. Sic. 33.27.1 = Goukowsky 33, fr. 36). Furthermore, it precedes a long excerpt from the introduction to the First Slave Revolt (Nr. 326, I, pages 302–3 = Diod. Sic. 34/35.2.27–31 = Goukowsky 34, fr. 2) that definitely links it with Book 34. Consequently, it may be claimed that fragment 2.25–6 is the first excerpt from Book 34 in the collection De uirtutibus et uitiis.

Thus the first and main precondition is fulfilled. The position of the two fragments allows us to assume that they could belong to the preface to Book 34. However, they could also originate from the introductory part of the narrative on the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, where they are to be found in all modern editions. We need therefore to look for another auxiliary tool to determine their function: Photius’ summary.

3.2 The paraphrase of Photius and the significant absence of fr. 34/35.2.33 Sent and fr. 2.25–6 Virt

As already mentioned, Photius summarized the introductory part of Diodorus’ narrative on the First Slave Revolt at greater length and detail. This is, in fact, the only part of his synopsis that contains many textual overlaps with Constantinian fragments.Footnote 20 However, there are no distinct traces of the two fragments in the summary of Photius, especially in the opening section, where we would expect to encounter them, if they belonged to this part of the narrative (2.1–3 Ph).

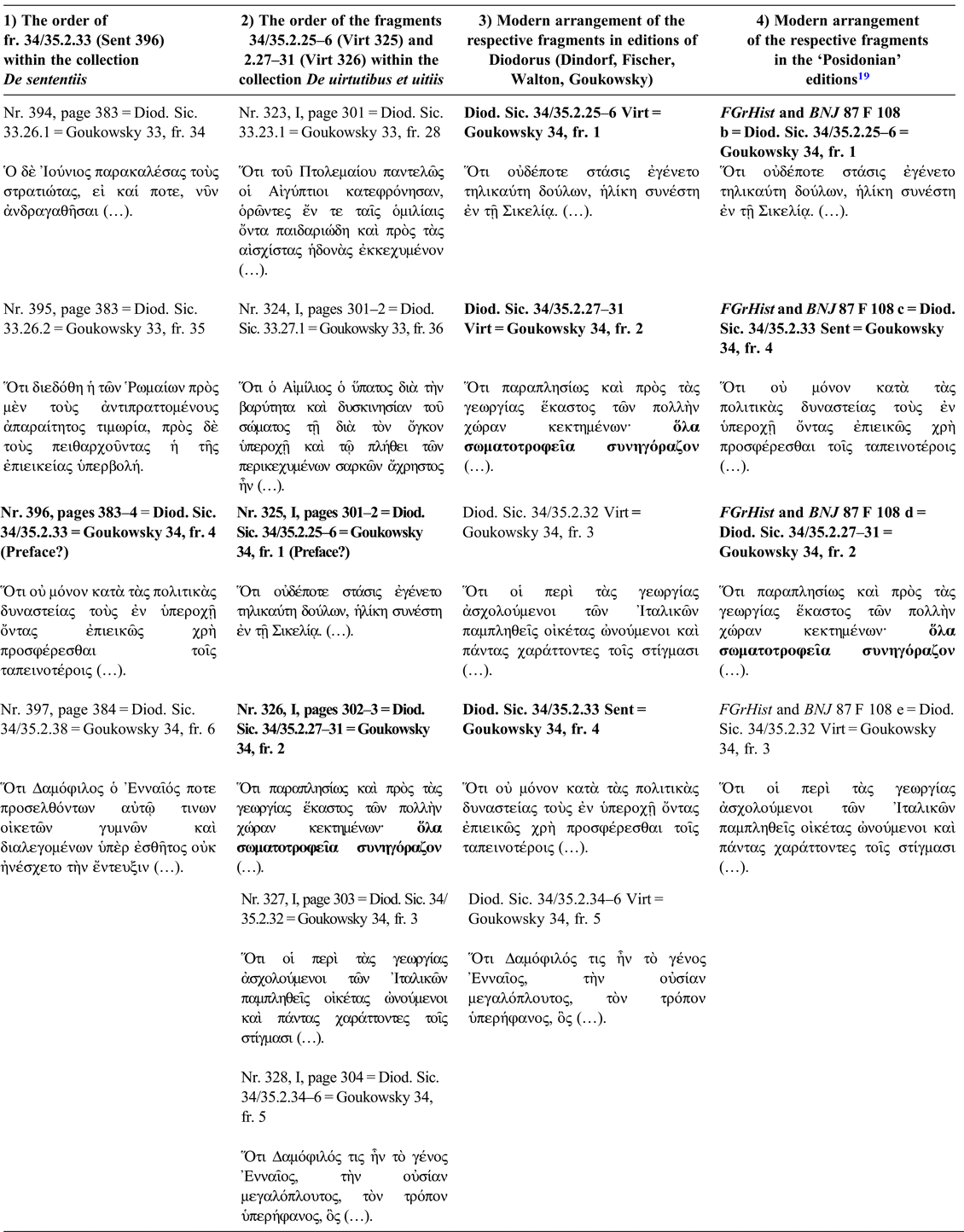

There are no indications of paraphrasing fr. 2.33 Sent and it is difficult to find any context within this summary in which this moral precept could be deployed. The absence of fr. 2.25–6 Virt from Photius’ paraphrase is even more instructive. An accurate comparison of Photius and Constantinian excerpts reveals that the beginning of Photius’ paraphrase, that is, exactly the opening part of his introduction to the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, corresponds with another excerpt from the collection De uirtutibus et uitiis, namely fr. 2.27–31 Virt. This fragment occurs in the Byzantine collection after fr. 2.25–6 Virt, which is considered here to be a part of the proem to Book 34. Table 2 juxtaposes the beginning of Photius’ summary and fr. 2.27–31 Virt.

Table 2 Comparison of Photius' introduction with fr. 2.27–31 Virt

Photius begins his summary with a reference to sixty years of prosperity in Sicily after the failure of Carthage in the Second Punic War (202/1 b.c.). ‘When Sicily, after the Carthaginian collapse, had enjoyed sixty years of good fortune in all respects, the Servile War broke out for the following reason᾿(2.1 Ph, transl. Walton). This sentence, presumably in a slightly altered transcription by Photius, was, in my view, the opening phrase of Diodorus’ account of the First Slave Revolt in Sicily. The reference to sixty years of prosperity was certainly not a strict chronological reference, but rather served originally as a backward cross-reference to the latest description of Sicilian events that was given in greater detail in the Bibliothêkê.Footnote 21 It is to be found in Books 26 and 27 and concerns events that happen during the Second Punic War.Footnote 22 In other words, with this reference Diodorus closes a sixty-year gap between two distant Sicilian narratives within the Bibliothêkê.Footnote 23 After this short summary, the proper introduction to the First Slave Revolt begins. Already in the first sentence of Photius’ paraphrase, a few linguistic overlaps with the Constantinian fragment 2.27–31 Virt can be discerned: cf. συνηγόραζον οἰκετῶν πλῆθος, ἐκ τῶν σωματοτροφείων, χαρακτῆρας in Photius with ὅλα σωματοτροφεῖα συνηγόραζον, χαρακτῆρσι in the Constantinian collection.Footnote 24 Particular attention should be paid to one significant word—σωματοτροφεῖον. In surviving ancient Greek literature, including Greek epigraphic sources and papyri, this word appears only in these two corresponding passages. The meaning and the function of σωματοτροφεῖα are still the subject of debate.Footnote 25 For our purpose, however, it is enough to conclude that it is a rare technical term or neologism copied by both of the Byzantine transmitters from the same passage of Diodorus. Moreover, several further corresponding phrases occur in both passages within the further narrative. Photius’ sentence καὶ μεστὰ φόνων ἦν ἅπαντα, καθάπερ στρατευμάτων διεσπαρμένων is composed of two sentences used originally in completely different settings. Finally, both the Photian paraphrase and the Constantinian excerpt transmit a relatively long chapter devoted to the misconduct of Roman administration in Sicily that is conveyed verbatim with minor textual differences (2.3 Ph, fr. 2.31 Virt).Footnote 26 These significant overlaps allow us to determine an evident correspondence of both Photius’ paraphrase from the introduction to the First Slave Revolt (2.1–3 Ph) and the Constantinian excerpt 2.27–31 Virt in terms of their narrative order.

However, if we consider fr. 2.27–31 Virt as belonging to the introduction to the narrative of the First Slave Revolt, what function and position in Book 34 is to be assigned to fr. 2.25–6 Virt? It certainly belongs to Book 34 and refers to the First Slave Revolt in Sicily. It precedes fr. 2.27–31 Virt in the collection De uirtutibus et uitiis. It has an obvious introductory character and is even more general in its tone and content than fr. 2.27–31 Virt. The answer is self-evident. According to its position in the Constantinian collection, it could belong to the preface to Book 34, which was presumably not located in close proximity to the narrative of the Slave Revolt. Photius did not paraphrase fr. 2.25–6 Virt, as he simply did not read it in the narrative of the First Slave Revolt.

I assume that the same conclusion applies to the moral precept provided in fr. 2.33 Sent. However, its belonging to the preface is conceivable owing not only to its narrative order but also to its theme, which corresponds with fr. 2.25–6 Virt. In what follows, I will demonstrate that the two fragments supplement each other providing a thoroughly consistent and interdependent argumentation.

3.3 Establishing a common topic of fr. 34/35.2.33 Sent and fr. 2.25–6 Virt

A further striking feature of the two fragments is not only that they emphasize a common moral theme, but also that they approach historical topics other than the First Slave Revolt in Sicily. Fragment 2.33 Sent conveys a moral precept that is composed in a highly antithetic way: ‘not only in the exercise of political power should men of prominence be considerate towards those of low estate, but also in private life all men of understanding should treat their slaves gently.’ The first clause of the sentence addresses rulers (τοὺς ἐν ὑπεροχῇ ὄντας) advising them to deal gently (ἐπιεικῶς) in political matters (κατὰ τὰς πολιτικὰς δυναστείας) with their subjects (τοῖς ταπεινοτέροις). The second clause recommends to slave-owners, indicated by the term ‘men of understanding’ (τοὺς εὖ φρονοῦντας), to act with consideration (πρᾴως) towards slaves (τοῖς οἰκέταις). The precept continues with exhortations against maltreatment of both slaves and subjects, as this conduct inevitably triggers either domestic uprising of slaves towards their owners or civil wars between free citizens. Thus it has wider focus differentiating between slave uprisings and other political unrests in general. The topic itself—mild treatment of subjects by rulers, expressed in the terms epieikeia and philanthropia, constitutes a predominant moral concept in Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê, often deployed elsewhere in the Bibliothêkê including even the prefaces to Books 15 and 32 (cf. also proem 14, especially 14.2.1).Footnote 27 Therefore, it would not be surprising to encounter similar sentiments in another proem. Likewise, the occurrence of the First Slave Revolt in Sicily as the main historical topic in the preface can be well explained by the origin of Diodorus. It is not unlikely that the native Sicilian would put his homeland, ‘the mighty island’ (cf. fr. 34/35.2.26 Virt – τὴν κρατίστην νῆσον), in the spotlight of his Universal History, once he has been given the opportunity to do so again (cf. n. 22 above).

Fragment 2.25–6 Virt seems to be a general introduction to the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, sometimes even compared with the opening passage of Thucydides.Footnote 28 At the beginning, the excerpt conveys a dramatic description of the horror felt by Sikeliots during the slave uprising. Subsequently, it becomes more aetiological explaining how the luxurious conduct of slave-owners gradually caused their arrogance and insolence towards their slaves, which, finally, degenerated into brutal maltreatment. In turn, slaves led by their hatred decided to rebel against their masters. Thus we are told here explicitly what the implicit reason of the uprising was: the maltreatment of slaves by the slave-owners—the topic well known from fr. 2.33 Sent.

At the end, however, the excerpt refers to other historical material that raises the question of its function—the confusing comparison to Aristonicus’ uprising. This analogy perplexes many scholars who castigate it as inadequate for chronological and historical reasons. The chronological annotation κατὰ τοὺς αὐτοὺς καιρούς (‘at the same period’) simply does not make sense in an annalistic work of Diodorus, for both events, the First Slave Revolt in Sicily (135–132 b.c.) and the uprising of Aristonicus (132–129 b.c.), do not match chronologically.Footnote 29 It was therefore presumed that Diodorus—or his source Posidonius—uses some higher chronology here,Footnote 30 or that this comparison has been added or displaced by the Constantinian excerptors themselves.Footnote 31 Moreover, scholars notice that the comparison τὸ παραπλήσιον δὲ γέγονε καὶ κατὰ τὴν Ἀσίαν (‘similar events took place throughout Asia’) is rather ahistorical. Although some researchers believe that the uprising of Aristonicus was a revolutionary movement carried on the shoulders of slaves and pauperized classes of society,Footnote 32 the majority consider this event as the war of a pretender to the throne supported by the Pergamene elites and army rather than by slaves and poor citizens.Footnote 33 Moreover, as rightly noticed by Christian Mileta, Diodorus himself describes this event in Book 34 rather as the uprising of oppressed subjects or citizens against the cruel treatment of Attalos III (34/35.3.1 = Goukowsky 34, fr. 21), thus not as a slave uprising.Footnote 34 Is there any positive solution for this textual perplexity?

If we regard this fragment as belonging to the preface to Book 34, the controversies mentioned above disappear. A ‘higher chronology’ would be entirely conceivable in a preface that refers to the content of the whole book. Similarly, a chronologically imprecise comparison to the uprising of Aristonicus is comprehensible in a preface that tends to simplify historical material and focusses on the common feature of the events that are to be narrated in the book. This common feature highlighted by Diodorus on the example of both events is obviously the mistreatment of slaves by their owners and perhaps, in parallel, of subjects by their rulers.

Thus it seems certain that both fragments belong together in terms of their narrative order and theme.Footnote 35 Moreover, there are further arguments for establishing a connection between the two fragments and recognizing them as a part of a preface: their structure and to some extent their phraseology.

3.4 Structure and style of fr. 34/35.2.33 Sent and fr. 2.25–6 Virt

As already demonstrated by Margrit Kunz, prefaces of Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê reveal similar structure, style and even phraseology. Kunz identifies six main parts, which may occur in a preface, each characterized by specific wording: 1) a general thesis with explanations; 2) examples for the thesis; 3) a transition sentence; 4) content of the preceding book (or books); 5) content of the book at hand; 6) introduction to the narrative.Footnote 36 The given paradigmatic pattern occurs, in fact, only in a few prefaces.Footnote 37 In most of the cases, a preface does not contain all sections or it conveys them in a different order.Footnote 38 To some extent, this is due to the structure of the whole work (the lesser preface to Book 1, Book 2 and Book 3), or to the incomplete text transmission (Book 11), or it may depend on the different topics which prefaces deal with (methodological prefaces vs moral-political prefaces). Self-evidently, it also applies for prefaces preserved in fragmentary books that lack all technical remarks such as tables of contents or transition sentences (parts 3–6). They usually consist only of the first and the second parts, providing theoretical claims and their exemplifications, which were of greater interest for Byzantine excerptors.Footnote 39 Yet both fr. 2.33 Sent and fr. 2.25–6 Virt may be perfectly settled within the outlined structure of Diodorus’ prefaces.

Fragment 2.33 Sent begins with a general moral precept: οὐ μόνον κατὰ τὰς πολιτικὰς δυναστείας τοὺς ἐν ὑπεροχῇ ὄντας ἐπιεικῶς χρὴ προσφέρεσθαι τοῖς ταπεινοτέροις, ἀλλὰ καὶ κατὰ τοὺς ἰδιωτικοὺς βίους πρᾴως προσενεκτέον τοῖς οἰκέταις τοὺς εὖ φρονοῦντας. This statement is followed by three sentences that explain the given precept in detail: a) ἡ γάρ, b) ὅσῳ δ’ … τοσούτῳ and c) πᾶς γὰρ ὁ. Yet this pattern resembles the first structural component of Diodorus’ proem, where the general thesis and its explanation are given.Footnote 40 This similarity becomes particularly clear by comparing fr. 2.33 Sent with the beginning of other prefaces, for example to Books 5, 19 and 21.

Pr. 5 (5.1.1–2): πάντων μὲν τῶν ἐν ταῖς ἀναγραφαῖς χρησίμων προνοητέον τοὺς ἱστορίαν συνταττομένους, μάλιστα δὲ τῆς κατὰ μέρος οἰκονομίας. αὕτη γὰρ οὐ μόνον ἐν τοῖς ἰδιωτικοῖς βίοις πολλὰ συμβάλλεται πρὸς διαμονὴν καὶ αὔξησιν τῆς οὐσίας, ἀλλὰ καὶ κατὰ τὰς ἱστορίας οὐκ ὀλίγα ποιεῖ προτερήματα τοῖς συγγραφεῦσιν. ἔνιοι δὲ …

It should be the special care of historians, when they compose their works, to give attention to everything which may be of utility, and especially to the arrangement of the varied material they present. This eye to arrangement, for instance, is not only of great help to persons in the disposition of their private affairs if they would preserve and increase their property, but also, when men come to writing history, it offers them not a few advantages. Some historians indeed (…). (transl. Oldfather)

Pr. 19 (19.1.1–3): παλαιός τις παραδέδοται λόγος ὅτι τὰς δημοκρατίας οὐχ οἱ τυχόντες τῶν ἀνθρώπων, ἀλλ’ οἱ ταῖς ὑπεροχαῖς προέχοντες καταλύουσι. διὸ καὶ τῶν πόλεων ἔνιαι τοὺς ἰσχύοντας μάλιστα τῶν πολιτευομένων ὑποπτεύουσαι καθαιροῦσιν αὐτῶν τὰς ἐπιφανείας. σύνεγγυς γὰρ ἡ μετάβασις εἶναι δοκεῖ τοῖς ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ μένουσιν ἐπὶ τὴν τῆς πατρίδος καταδούλωσιν καὶ δυσχερὲς ἀποσχέσθαι μοναρχίας τοῖς δι’ ὑπεροχὴν τὰς τοῦ κρατήσειν ἐλπίδας περιπεποιημένοις· ἔμφυτον γὰρ εἶναι τὸ πλεονεκτεῖν τοῖς μειζόνων ὀρεγομένοις καὶ τὰς ἐπιθυμίας ἔχειν ἀτερματίστους.

An old saying has been handed down that it is not men of average ability but those of outstanding superiority who destroy democracies. For this reason some cities, suspecting those of their public men who are the strongest, take away from them their outward show of power. It seems that the step to the enslavement of the fatherland is a short one for men who continue in positions of power, and that it is difficult for those to abstain from monarchy who through eminence have acquired hopes of ruling; for it is natural that men who thirst for greatness should seek their own aggrandizement and cherish desires that know no bounds. (transl. Geer)

Pr. 21 (21.1.4a = Goukowsky 21, fr. 1): πᾶσαν μὲν κακίαν φευκτέον ἐστὶ τοῖς νοῦν ἔχουσι, μάλιστα δὲ τήν πλεονεξίαν. αὕτη γὰρ διὰ τὴν ἐκ τοῦ συμφέροντος ἐλπίδα προκαλουμένη πολλοὺς πρὸς ἀδικίαν, μεγίστων κακῶν αἰτία γίνεται τοῖς ἀνθρώποις. διὸ καὶ μητρόπολις οὔσα τῶν ἀδικημάτων, οὐ μόνον τοῖς ἰδιώταις ἀλλὰ καὶ τοῖς μεγίστοις τῶν βασιλέων, πολλὰς καὶ μεγάλας ἀπεργάζεται συμφοράς.

All vice should be shunned by men of intelligence, but especially greed, for this vice, because of the expectation of profit, prompts many to injustice and becomes the cause of very great evils to mankind. Hence, since it is a very metropolis of unjust acts, it brings many great misfortunes not only on private citizens but even on the greatest kings. (transl. Walton)

In all these prefaces, a moral precept or general statement is given at the beginning, in two cases provided by means of a verbal adjective (5 προνοητέον; 21 φευκτέον). These statements precede further sentences that aim to explain given sentiments in a broader range or support them by additional arguments. The similarity of this composition with the structure of fr. 2.33 Sent is evident. As a result, it may be claimed that, if fr. 2.33 Sent were a part of the preface to Book 34, it probably occupied the equivalent position in this proem: its very beginning. In addition, there are further stylistic resemblances between fr. 2.33 Sent and Diodorus’ prefaces.

A notable stylistic feature in fr. 2.33 Sent is the dense use of antithetic parallelisms that determine the arrangement of the whole fragment:

-

κατὰ τὰς πολιτικὰς δυναστείας → κατὰ τοὺς ἰδιωτικοὺς βίους

-

ἐπιεικῶς χρὴ προσφέρεσθαι τοῖς ταπεινοτέροις → πρᾴως προσενεκτέον τοῖς οἰκέταις

-

ἐν μὲν ταῖς πόλεσιν … ἀπεργάζεται → ἐν δὲ τοῖς … οἴκοις … κατασκευάζει

-

ὅσῳ → τοσούτῳ.

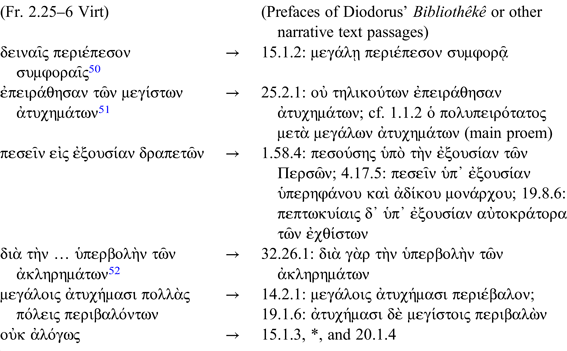

Yet antitheses and parallelisms are representative of Diodorus’ style. The main preface of the Bibliothêkê contains plenty of examples of parallel constructions.Footnote 41 The negated antithesis οὐ μόνον … ἀλλὰ καί (‘not only … but also’) employed at the beginning of fr. 2.33 Sent—although a very common rhetorical device in Greek—can be found remarkably often in a similar position in other Diodoran prefaces.Footnote 42 For expressing imperative necessity (what should or must be done) within the moral precept, the impersonal verb χρή and the verbal adjective προσενεκτέον are employed. Verbal adjectives are relatively frequent in prefaces (cf. Pr. 5 and 21 above).Footnote 43 Furthermore, several corresponding phrases used in fr. 2.33 Sent appear in other prefaces:

Thus it seems clear that fr. 2.33 Sent not only shares with other prefaces the common structural outline and stylistic devices but also contains some specific wording which is employed in several prefaces of the Bibliothêkê.

However, if fr. 2.33 Sent originally opened the preface to Book 34, which position and function did fr. 2.25–6 Virt occupy within this preface? The only possible section to which it could belong is the second part of the preface. In this part, examples from earlier or later history are given to prove the validity and rightness of a given statement or precept. This part is often of a relatively wide scope depending on how many historical paradigms are provided.Footnote 46 In fact, fr. 2.25–6 Virt ideally fulfils the purposes of this section, providing historical exempla for the precept that Diodorus conveys in fr. 2.33 Sent. The moral instruction delivered here recommends that ʻnot only in the exercise of political power (κατὰ τὰς πολιτικὰς δυναστείας) should men of prominence be considerate towards those of low estate, but also in private life (κατὰ τοὺς ἰδιωτικοὺς βίους) all men of understanding should treat their slaves gently'. The arrogant behaviour and brutality towards all subjects, slave and fellow citizens, drive them to the state of desperation that triggers local uprisings and, in the end, wars against the whole state. And, correspondingly, fr. 2.25–6 Virt encompasses two significant historical examples that ideally suit the conceptual framework emphasized in fr. 2.33 Sent showing that the maltreatment of subjects (slaves) was indeed a reason for great slave uprisings or wars. The first example, the Slave Revolt in Sicily, belongs undeniably to the domain of domestic life (κατὰ τοὺς ἰδιωτικοὺς βίους). It was a local uprising against one slave-owner (Damophilus) in Enna that developed into a great upheaval. The second example, Aristonicus’ uprising, is more complex. At first glance, it seems to belong to the group of slave revolts. However, the phrase ‘similar events took place᾿ (τὸ παραπλήσιον δὲ γέγονε) does not necessarily mean that Aristonicus’ revolt was a slave uprising.Footnote 47 Diodorus may have only emphasized here the common denominator of both events: the participation of slaves in them. He could instead consider Aristonicus’ uprising as belonging to the domain of political affairs (κατὰ τὰς πολιτικὰς δυναστείας), for, as already mentioned, one fragment preserved in Book 34 depicts Aristonicus’ uprising rather as a revolt of citizens against the brutal royal power of Attalos III. Moreover, it cannot be excluded that in the original preface to Book 34 further historical examples from Book 34 were given.Footnote 48

Whereas the order and the content of fr. 2.25–6 Virt allow us to establish a connection with the preface to Book 34, its stylistic form and phraseology do not reveal significant evidence to support that claim. The main reason for this is that parts of prefaces that contain historical examples differ strongly from each other in terms of topic and, consequently, language. However, there are indications suggesting that fr. 2.25–6 Virt may belong to the preface of Book 34 rather than to the narrative on the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, on the grounds of its style and language. First, fr. 2.25–6 Virt introduces in a general way contents which are repeated later in Book 34 in a greater detail, sometimes even by means of the same phraseology and words.Footnote 49 Second, fr. 2.25–6 Virt introduces these contents with tragic pathos and rhetorical imprint, already characteristic of fr. 2.33 Sent. Particularly remarkable is the use of a series of hyperboles that describe the scale of sufferings of Sikeliots during the First Slave Revolt: δειναῖς περιέπεσον συμφοραῖς, ἀναρίθμητοι δὲ ἄνδρες καὶ γυναῖκες, ἐπειράθησαν τῶν μεγίστων ἀτυχημάτων, πᾶσα δὲ ἡ νῆσος or τιθεμένων τὴν τῶν ἐλευθέρων ὑπερβολὴν τῶν ἀκληρημάτων. Furthermore, certain phrases used in fr. 2.25–6 Virt also occur elsewhere in the Bibliothêkê and are representative of Diodorus’ style and language:

These corresponding elements may imply that Diodorus wrote this fragment rather more independently of his source, a circumstance that is more likely to be the case in the preface rather than in the main historical narrative on the First Slave Revolt, where he must have consulted his source or sources more closely.Footnote 53 Finally, as previously mentioned, scholars occasionally compare this fragment with the opening preface of Thucydides because of its rhetoric and aetiological character.Footnote 54 If Diodorus indeed tries to emulate Thucydides here, then it is more plausible that he would perform that in a preface rather than within the historical narrative of the First Slave Revolt.

4. CONCLUSION

In this paper it has been argued that two Constantinian fragments from the narrative on the First Slave Revolt in Sicily (fr. 2.33 Sent and fr. 2.25–6 Virt) originate from the unknown preface to Book 34. Several indications have been discussed to support this hypothesis. First, the respective positions of both fragments in the Constantinian collections suggest that they might belong to the preface of Book 34, as both of them represent the first excerpt from Book 34 in the respective collection. Moreover, it has been shown that Photius did not paraphrase these fragments in his synopsis of Diodorus and that the beginning of his summary corresponds with another excerpt from the collection De uirtutibus et uitiis (fr. 2.27–31 Virt). Significantly, this fragment follows fr. 2.25–6 Virt in the respective collection and, thus, fr. 2.25–6 Virt must have originally occurred in Book 34 before the narrative on the First Slave Revolt. Second, the two fragments share similar content, with both raising the question of the proper conduct of men of power (rulers and slave-owners) towards their subjects (citizens and slaves). While doing so, they complement each other by demonstrating in theory (fr. 2.33 Sent) and in practice (fr. 2.25–6 Virt) the dramatic and deplorable consequences that the harshness and brutality of men of power can evoke. The theme itself represents one of the most important moral and political messages in the Bibliothêkê and can be occasionally found in other book prefaces (15, 32). Moreover, the two fragments refer not only to the First Slave Revolt in Sicily, but also deal with different themes. In this context, the reference to Aristonicus’ uprising is of particular importance, for its chronological and thematic connection with the First Slave Revolt is reasonable only in the preface to Book 34. Further, the two fragments may be perfectly integrated within the structure of Diodorus’ prefaces, the first (fr. 2.33 Sent) providing a moral precept (part one of prefaces) and the second (fr. 2.25–6 Virt) historical examples that substantiate it (part two of prefaces). Finally, the phraseology of the two fragments resembles that of other Diodoran prefaces. Thus there is sufficient evidence to consider both fragments a part of a new preface from Diodorus’ Bibliothêkê.