Alcohol is one of the major risk factors for chronic diseases and injury in most countries of the world. Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra1 Rehm and colleagues estimated that 3.8% of all global mortality and 4.6% of global disability-adjusted life-years were the result of alcohol use. Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra1 The total economic cost of alcohol consumption was estimated to be 2.5% for high-income countries such as the USA, Canada, Scotland and France. Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra1 A large number of studies have documented the links between alcohol use disorders and other mental health disorders such as bipolar affective disorder, major depression, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorders and drug use disorders. Reference Burns and Teesson2–Reference Swendsen and Merikangas7 However, it is unclear whether there are any causal relationships between alcohol dependence and comorbid mental disorders, and what the direction of any such causalities may be. The nationally representative, retrospective US cohort study by Kessler et al Reference Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg and Anthony4 showed that diagnosis of a mental disorder was associated with an increased risk of alcohol use disorders. Reference Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg and Anthony4 Drawing on Australian data from the 1997 Mental Health and Well-Being (MHW) survey, Degenhardt & Hall Reference Degenhardt and Hall8 reported that mental disorders are more prevalent among people with harmful alcohol use compared with low/moderate drinkers. However, the 1997 MHW survey focused on the prevalence of mental disorders in a 12-month time frame 9 and it is therefore not possible to investigate the causal direction between alcohol use disorders and other mental disorders. Ten years on, the 2007 MHW survey aims to estimate the prevalence of lifetime mental disorders 9 and includes information on age at first onset, which makes it possible to determine which mental disorders came first. Burns & Teesson in 2002 reported that a third of respondents who had an alcohol use disorder 12 months prior to the survey also met the diagnostic criteria for at least one comorbid mental disorder for the same period, but it was not apparent whether common mental disorders may increase the risk of alcohol dependence/alcohol misuse or vice versa. Reference Burns and Teesson2 The aim of this study was to use data drawn from a representative national Australian sample to investigate whether affective disorders and anxiety disorders increase the risk of alcohol dependence and alcohol use.

Method

This is a retrospective cohort study based on data collected from the 2007 MHW survey. The 2007 MHW survey was a nationally representative household survey, and its data included 8841 Australian adults aged 18–85 years. Reference Slade, Johnston, Oakley Browne, Andrews and Whiteford10 Each interview collected information required for the assessment of ICD-10 11 disorders using a modified version of the World Mental Health Survey Initiative version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI 3.0). Reference Kessler and Ustun12 Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers. 9 The diagnoses covered in the 2007 MHW survey included: affective disorders (depression, dysthymia, bipolar affective disorder); anxiety disorders (agoraphobia, social phobia, panic disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder); substance use disorders (alcohol, cannabis, sedatives, stimulants and opioids), harmful substance use and dependence. 9 Alcohol misuse was diagnosed where the respondent had experienced at least one of the following associated with alcohol use: frequent interference with work or other responsibilities; causing arguments or other serious problems with family, friends, neighbours or co-workers; jeopardising safety because of alcohol use; or being arrested or stopped by police for drink-driving or drunken behaviour. 9 Details of measurements and interviews have been described in the summary of results produced by the Australia Bureau of Statistics 9 and by Slade et al. Reference Slade, Johnston, Oakley Browne, Andrews and Whiteford10 Alcohol dependence was diagnosed if three or more of the following occurred within the same year: strong desire or compulsion to consume alcohol; difficulties in controlling alcohol consumption behaviour; withdrawal symptoms (for example fatigue, headaches, diarrhoea, the shakes or emotional problems); tolerance to alcohol (for example needing to drink a larger amount for the same effect); neglect of alternative interests because of alcohol use; or continued use despite knowing it is causing significant problems. 9

The MHW survey estimated age at first onset for mental disorders based on the respondent’s recalled age for the first-time experience of an episode. 9 In the current study, age at first onset was used to define the mental disorder exposure variable. Kessler et al Reference Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg and Anthony4 successfully used age at first onset drawn from a national mental health survey as a measure of exposure in a previous retrospective cohort study.

The effect of mental disorders on the risk of alcohol dependence and alcohol misuse were investigated in two ways: descriptive analysis showing cumulative risk of alcohol dependence (Kaplan–Meier failure function graph); and multivariate analysis using both Poisson and logistic regression models.

Data analysis

A Kaplan–Meier failure function graph was used to describe the difference in cumulative risk of alcohol dependence in participants with lifetime affective disorders and those without. The analysis was stratified by gender. The same analysis was repeated for exposure to anxiety disorders. For this analysis, survival time was defined as between birth and the time of the survey or the onset of alcohol dependence, whichever came first. Because co-occurring mental disorders may have confounding effects on risk of alcohol use disorders, multivariate analysis was used to estimate the adjusted effects of different types of mental disorders. Two sets of multivariate analyses were performed. The second set of multivariate analyses included all of the specific subtypes for affective disorders (major depressive episode, minor depressive episode, moderate depressive episode, dysthymia bipolar affective disorder), anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder), and harmful use of drugs (any of cannabis, sedatives, stimulants and opioids). Each set of analyses were repeated to assess two outcomes: alcohol dependence; and alcohol misuse with/without alcohol dependence (alcohol harmful use, ICD-10). 11 A Poisson regression model and a logistic regression model were used for each set of analyses.

In the Poisson models, the retrospective cohort data were converted from a per-participant unit of measurement to a per-person-time unit of measurement. Each unit of observation was one person-year at risk, which is denoted by the participant from whom it was observed and the age of the participant at the time when it was observed (similar to age at different follow-up periods in prospective cohort studies). A similar analytical strategy was used by Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg and Anthony4 No respondent reported alcohol misuse or dependence prior to 9 years of age, thus the analysis period was set as beginning at age 9. The analysis period for a participant ended when an event was observed or at

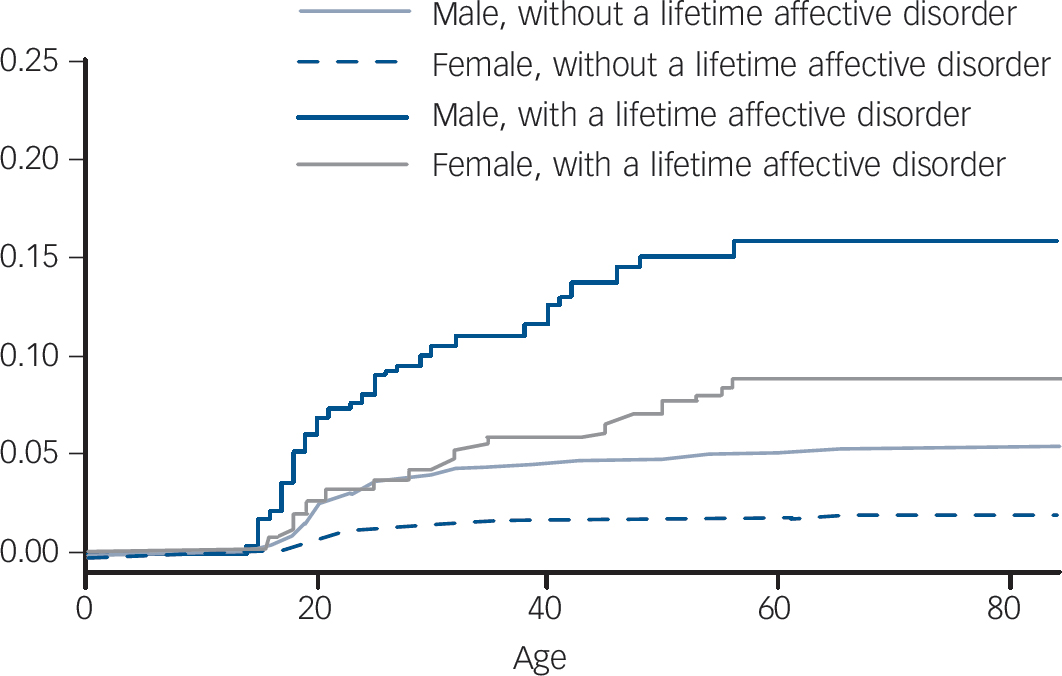

Fig. 1 Cumulative risk of alcohol dependence by gender after exposure to pre-existing affective disorder.

the time the survey was performed, whichever came first, in the same manner as a prospective cohort study. If a particular mental disorder occurred more than 5 years prior to a person-year at risk being observed, it was defined as past exposure to the mental disorder. If a mental disorder occurred within 5 years of the time when a person-year at risk was observed, it was defined as recent exposure. The Poisson regression models also controlled for gender, age at survey and the age when person-years at risk were observed.

Given that the data collected by the MHW survey were retrospective, there may be recall bias among respondents. In order to be conservative, the analysis was repeated but restricted to the 5-year period before the survey (i.e. events occurring between 2003 and 2007) and analysed using logistic regression. Thus, the follow-up time of the retrospective cohort was set as beginning in 2003; if a respondent indicated an event as occurring before the follow-up period, the participant was removed from the analysis. The follow-up period ended when an event was observed or at the time the survey was performed, whichever came first. The logistic regression models also controlled for gender, age at survey and demographics at the time of the survey including: highest education qualifications obtained, Socioeconomic Index for Areas (SEIFA) index of disadvantage and remoteness of residency. 13

Results

Kaplan–Meier failure function graphs

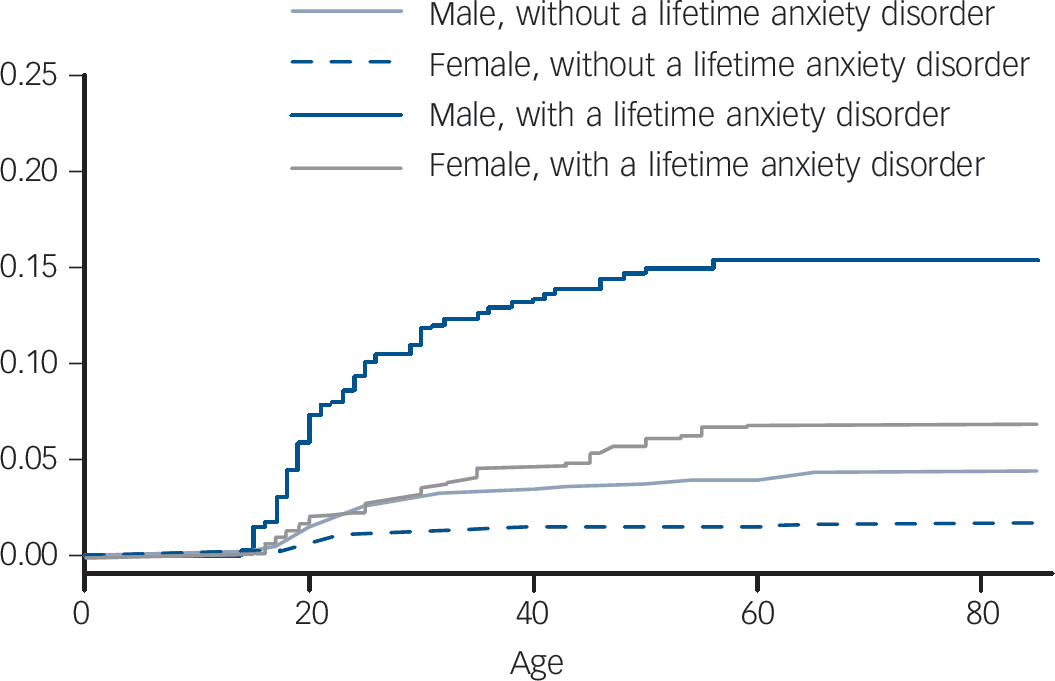

There are 8841 participants in the MHW 2007 data, 342 (3.8%) participants had received an alcohol dependence diagnosis at sometime before the survey. We were not able to determine age at first onset of alcohol dependence for six participants, thus excluding them from further analysis. The Kaplan–Meier failure function graph for onset of alcohol dependence among respondents with pre-existing affective and anxiety disorders included 8835 individuals, with 336 failures in total. As shown in Fig. 1, for both genders the cumulative risk of alcohol dependence was higher among participants with a pre-existing affective disorder than those without for any period after the age of 20 years. Similar patterns are shown in Fig. 2 for anxiety disorders. For both males and females the cumulative risk of alcohol dependence was higher among participants with a pre-existing anxiety disorder.

Figure 1 shows a gradual and continuous increase in cumulative risk of alcohol dependence for participants between

Fig. 2 Cumulative risk of alcohol dependence by gender after exposure to pre-existing anxiety disorder.

the age of 18 and 50 with a pre-existing affective disorder. The cumulative risk of participants without a pre-existing affective disorder appears to be relatively constant after the age of 30. Similar patterns are shown in Fig. 2 for anxiety disorders. Continuous and relatively constant increases in cumulative risk are indicative of a relatively constant age-specific incidence of alcohol dependence. Figures 1 and 2 suggest that participants with pre-existing affective and anxiety disorders have an increased risk of alcohol dependence from age 18 to 50 years.

Multivariate models predicting alcohol misuse

Among the 8841 participants, there were 1861 with alcohol misuse with/without alcohol dependence sometime before the survey. The age at first onset of alcohol misuse could not be determined for 12

Table 1 Exposure to mental disorders and risk of alcohol misuse

| Poisson regression mode | Logistic regression model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Affective disordersa | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.43 | 1.13–1.81 | 1.82 | 1.19–2.79 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 2.50 | 2.09–2.98 | 2.19 | 1.44–3.34 |

| Anxiety disordersa | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.79 | 1.57–2.04 | 1.62 | 1.18–2.22 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.71 | 1.44–2.03 | 1.45 | 0.95–2.20 |

| Panic disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.29 | 0.93–1.78 | 1.06 | 0.51–2.17 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.49 | 1.10–2.02 | 0.84 | 0.32–2.17 |

| Agoraphobia with/without panic disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.04 | 0.80–1.35 | 0.56 | 0.30–1.06 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 0.71 | 0.49–1.02 | 0.33 | 0.09–1.14 |

| Social phobiab | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.44 | 1.21–1.72 | 1.30 | 0.82–2.05 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.52 | 1.19–1.95 | 1.74 | 0.72–4.24 |

| Generalised anxiety disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.48 | 1.09–2.02 | 2.88 | 1.52–5.43 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.08 | 0.76–1.55 | 1.33 | 0.54–3.28 |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder onsetb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.00 | 0.65–1.52 | 0.61 | 0.21–1.72 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.41 | 0.92–2.15 | 3.09 | 1.32–7.26 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.26 | 1.02–1.55 | 1.42 | 0.92–2.20 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.49 | 1.17–1.90 | 0.86 | 0.49–1.51 |

| Major depressive episodeb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.21 | 0.85–1.74 | 1.30 | 0.64–2.62 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.73 | 1.29–2.31 | 1.36 | 0.64–2.89 |

| Minor depressive episodeb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 0.79 | 0.20–3.18 | 2.98 | 0.64–13.90 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.85 | 0.88–3.91 | 1.58 | 0.34–7.45 |

| Moderate depressive episodeb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.30 | 0.81–2.09 | 0.69 | 0.23–2.10 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.39 | 0.87–2.22 | 0.90 | 0.25–3.16 |

| Dysthymiab | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.25 | 0.75–2.07 | 0.50 | 0.13–1.95 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.56 | 0.96–2.52 | 2.41 | 0.49–11.80 |

| Bipolar affective disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.27 | 0.81–2.00 | 2.88 | 1.48–5.59 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 3.23 | 2.46–4.22 | 4.40 | 2.20–8.83 |

| Harmful drug useb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 2.35 | 1.72–3.21 | 2.79 | 1.63–4.77 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 4.39 | 3.73–5.18 | 4.29 | 2.58–7.14 |

a Reference category: ‘absence’ of the specific mental disorder. The Poisson model was adjusted for affective disorders, anxiety disorders, gender, age at survey, and age when person-years at risk were observed. The logistic model was adjusted for affective disorders, anxiety disorders, gender, age at survey, demographics at the time of the survey (highest educational qualifications, index of disadvantage and remoteness of residence).

b Reference category: ‘absence’ of the specific mental disorder. The Poisson model was adjusted for major depressive episode, minor depressive episode, moderate depressive episode, dysthymia, bipolar affective disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and harmful use of drugs (any of cannabis, sedatives, stimulants and opioids) as predictors, gender, age at survey, and age when person-years at risk were observed. The logistic model was adjusted for the same mental disorder subtypes as well as gender, age at survey, demographics at the time of the survey (highest educational qualifications, index of disadvantage and remoteness of residence).

participants, and they were therefore excluded from this analysis. The Poisson models for alcohol misuse included 1846 events. The logistic regression alcohol misuse models excluded participants who had alcohol misuse more than 5 years before the survey and thus included 334 events.

Table 1 shows the association between pre-existing mental disorders and the risk of alcohol misuse (with/without alcohol dependence). The associations were estimated by both Poisson and logistic regression models. The two broad groups of mental disorders (affective disorders and anxiety disorders) were associated with a significantly higher risk of alcohol misuse in both models. Moreover, for affective disorders, the Poisson model indicated that the risk of alcohol misuse within 5 years of first onset was significantly higher than the risk after 5 years of onset (2.50 v. 1.43, tested by Wald tests P<0.001), but was not significant in the logistic model.

When the models were fitted for subtypes of mental disorders, risk of alcohol misuse (with/without alcohol dependence) was found to be higher among those exposed to bipolar affective disorder and drug misuse (non-alcohol) in both models regardless of the period of onset. Social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder were significantly associated with an increased risk of alcohol misuse using the Poisson model for both exposure periods, but not in the logistic model. Onset of major depression within the previous 5 years was also significantly associated with increased risk of alcohol misuse in the Poisson model. Moreover, in the Poisson models, the risk of alcohol misuse within 5 years of first onset of a bipolar affective disorder or drug misuse was significantly higher than in the period beyond 5 years of onset (3.23 v. 1.27; 4.39 v. 2.35, tested by Wald tests, both P<0.001), but neither was significant in the logistic model.

Multivariate models predicting alcohol dependence

There were 336 alcohol dependence events for analysis in the Poisson model (i.e. similar to the Kaplan–Meier failure function graphs). The logistic regression for alcohol dependence excluded respondents who had an alcohol dependence more than 5 years before the survey (to reduce recall bias), and included 80 events. Table 2 shows the association between pre-existing mental disorders and the risk of alcohol dependence. Affective disorders, regardless of the length of exposure, were associated with a significantly higher risk of alcohol dependence in both the Poisson and logistic regression models. Anxiety disorders were associated with a significantly higher risk of alcohol dependence in the Poisson model where exposure was both greater and less than 5 years, but the logistic regression models indicated that only exposure to anxiety disorders for more than 5 years significantly predicted alcohol dependence. Moreover, according to the Poisson models, the risk of alcohol dependence within 5 years of first onset of an affective disorder was higher than the risk evident in the longer term (5.46 v. 2.77, tested by Wald tests P = 0.064).

When the models were fitted for subtypes of mental disorders, risk of alcohol dependence was significantly higher when exposed to generalised anxiety disorder, bipolar affective disorder and drug misuse in both models regardless of exposure time. Panic disorder and major depressive episode were significantly associated with an increased risk of alcohol dependence (for both time periods) in the Poisson model but not in the logistic model. Onset of moderate depressive episode and dysthymia within the previous 5 years was also significantly associated with an increased risk of alcohol dependence in the Poisson model. Exposure to obsessive–compulsive disorder for more than 5 years was significantly associated with an increased risk of alcohol dependence (Table 2). Furthermore, according to the Poisson models, the risk of alcohol dependence within 5 years of

Table 2 Exposure to mental disorders and risk of alcohol dependence

| Poisson regression model | Logistic regression modelc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Affective disordersa | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 2.77 | 1.93–3.99 | 3.78 | 2.04–6.99 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 5.46 | 4.08–7.31 | 3.18 | 1.60–6.34 |

| Anxiety disordersa | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 3.56 | 2.72–4.64 | 2.30 | 1.33–3.99 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 3.33 | 2.37–4.68 | 1.91 | 0.88–4.15 |

| Panic disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 2.13 | 1.35–3.38 | 1.43 | 0.49–4.14 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 2.91 | 1.86–4.53 | 2.98 | 0.94–9.46 |

| Agoraphobia with/without panic disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.19 | 0.78–1.83 | – | – |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 0.68 | 0.37–1.23 | – | – |

| Social phobiab | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.47 | 1.04–2.07 | 0.54 | 0.25–1.16 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.19 | 0.68–2.06 | 0.37 | 0.05–2.51 |

| Generalised anxiety disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 2.15 | 1.34–3.43 | 5.84 | 2.52–13.54 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 2.03 | 1.25–3.30 | 6.78 | 2.55–18.00 |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder onsetb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 3.28 | 2.06–5.24 | 0.90 | 0.24–3.38 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 0.96 | 0.46–2.02 | 1.01 | 0.23–4.51 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.26 | 0.86–1.84 | 0.63 | 0.27–1.49 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.75 | 1.15–2.67 | 1.03 | 0.41–2.62 |

| Major depressive episodeb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.79 | 1.03–3.11 | 2.57 | 0.98–6.76 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 2.83 | 1.74–4.60 | 1.06 | 0.23–4.80 |

| Minor depressive episodeb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.99 | 0.28–14.35 | – | – |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 1.69 | 0.23–12.10 | – | – |

| Moderate depressive episodeb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 0.95 | 0.34–2.63 | 1.77 | 0.49–6.38 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 2.29 | 1.07–4.91 | 0.78 | 0.10–6.26 |

| Dysthymiab | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 1.67 | 0.76–3.65 | – | – |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 3.31 | 1.76–6.22 | – | – |

| Bipolar affective disorderb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 2.62 | 1.47–4.68 | 6.67 | 2.83–15.76 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 7.49 | 4.94–11.35 | 5.53 | 2.13–14.37 |

| Harmful drug useb | ||||

| Occurred 5+ years ago | 2.60 | 1.68–4.04 | 2.86 | 1.35–6.09 |

| Occurred within previous 5 years | 5.49 | 4.04–7.47 | 6.23 | 3.01–12.90 |

a The reference category is ‘absence’ of the specific mental disorder. The Poisson model was adjusted for affective disorders, anxiety disorders, gender, age at survey, and age when person-years at risk were observed. The logistic model was adjusted for affective disorders, anxiety disorders, gender, age at survey, and demographics at the time of the survey (highest educational qualifications, index of disadvantage and remoteness of residence).

b The reference category is ‘absence’ of the specific mental disorder. The Poisson model was adjusted for major depressive episode, minor depressive episode, moderate depressive episode, dysthymia, bipolar affective disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and harmful use of drugs (any of cannabis, sedatives, stimulants and opioids) as predictors, gender, age at survey, and age when person-years at risk were observed. The logistic model was adjusted for the same mental disorder subtypes as well as gender, age at survey, demographics at the time of the survey (highest educational qualifications, index of disadvantage and remoteness of residence).

c Blank cells indicate that ORs were not estimated owing to insufficient sample size.

first onset of a bipolar affective disorder or drug misuse was significantly higher than the risk of alcohol dependence after longer-term exposure to these disorders (7.49 v. 2.62; 5.49 v. 2.60, tested by Wald tests both P<0.05), but neither was significant in the logistic model.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first Australian study to investigate whether a pre-existing mental disorder may predict the later onset of an alcohol use disorder with a national representative sample. The results of the current study showed that participants with pre-existing affective disorders and anxiety disorders were at greater risk of alcohol misuse and alcohol dependence; a finding also observed among the US population. Reference Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg and Anthony4,Reference Dixit and Crum14,Reference Gilman and Abraham15 For Australians, the increased risk of developing alcohol dependence is especially large for people recently (previous 5 years) diagnosed with affective disorders – some five times greater than for people without this mental health condition. This was particularly true for those with bipolar affective disorder for whom the risk of developing alcohol dependence was over seven times greater. The findings of this study concur with results from previous analyses of the 1997 MHW survey Reference Degenhardt and Hall8 and the 2007 MHW survey, Reference Slade, Johnston, Oakley Browne, Andrews and Whiteford10 both of which suggest that people with alcohol use disorders had a higher prevalence of affective disorders and anxiety disorders. Consistent with the findings of Kesser et al, Reference Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg and Anthony4 this study showed that the association between mental disorders and alcohol dependence was stronger than the association between mental disorders and alcohol misuse. It was also noted that social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder were associated with an increased risk of alcohol misuse but not alcohol dependence, whereas generalised anxiety disorders were associated with an increased risk of alcohol dependence but not alcohol misuse.

Implications

Overall, these findings appear to suggest that pre-existing mental disorders may play an important role in the onset of both alcohol use disorders. The list of potential confounders included in these analyses was not exhaustive and there is potential for the results to be confounded by uncontrolled genetic factors. Several clinical and epidemiological studies also suggest that onset of alcohol use disorders increases the risk of other mental disorders. Reference Gilman and Abraham15–Reference Goodwin, Fergusson and Horwood18 As reported in the results, within 5 years of first onset of a bipolar affective disorder, the risk of alcohol dependence and alcohol misuse was higher than for the period beyond 5 years of onset of the mental disorder. This indicates that the prevention of alcohol use disorder is important for individuals with recent onset of a first episode of a bipolar affective disorder.

However, our observations do not preclude the possibility that the direction of causality between mental disorders and alcohol misuse may be two-way, Reference Gilman and Abraham15 that is, each may cause the other, both possibly being linked via genetic components, Reference Knopik, Heath, Madden, Bucholz, Slutske and Nelson5,Reference Prescott and Kendler19–Reference Nurnberger, Wiegand, Bucholz, O'Connor, Meyer and Reich21 with the simultaneous risks not necessarily of equivalent magnitude. Nevertheless, until further evidence of causal mechanisms come to light, in the healthcare setting, the judicious and practical approach would be to view mental health disorders as a risk factor for future alcohol misuse and alcohol dependence. Given that the risk of alcohol use disorders were found to be considerably higher among people with pre-existing affective disorders and anxiety disorders, promoting self-awareness of alcohol use disorders among such individuals in routine consultations may help to reduce the onset of alcohol use disorders as well as enable better treatment outcomes of primary mental disorders.

Limitations

The 2007 MHW survey was conducted on a nationally representative sample but the response rate was about 60% and selection bias may be present among those people who chose to participate. Individuals with mental health disorders are probably more likely to be underrepresented than overrepresented in national surveys of this nature. Reference Slade, Johnston, Oakley Browne, Andrews and Whiteford10 Nevertheless, we note that the aim of our study was to investigate the associations among mental disorders and alcohol use disorders, and not to estimate prevalence per se.

The diagnosis of mental disorders in the 2007 MHW survey relied on information gathered by trained interviewers. Although the use of WMH-CIDI 3.0 by interviewers has been validated, 9 it is possible that the diagnosis of mental disorders was not as precise as it could have been if made by a psychiatrist or psychologist. This may be especially true for older respondents who are more likely to have impaired cognitive function and have fewer standard symptoms. Reference O'Connor22,Reference Trollor, Anderson, Sachdev, Brodaty and Andrews23

Recall bias is a potential problem with this study, especially among older respondents who may have trouble remembering diagnoses over longer periods of time. Reference Kessler, Angermeyer, Anthony, De Graaf, Demyttenaere and Gasquet24 Potential confounding by recall bias was in part mitigated by the inclusion of additional logistic regression models limited to only the most recent 5 years that largely supported the findings of the Poisson regression models.

In conclusion, the results of the current study suggest that participants with affective disorders and anxiety disorders are at higher risk of alcohol misuse and alcohol dependence. It is uncertain whether the observed association is causal; however, symptoms of mental health disorders could be used to identify people at increased risk of alcohol misuse and alcohol dependence, and enable access to early interventions.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.