INTRODUCTION

The Big Man is an enduring presence in political life across much of sub-Saharan Africa. He is the apex figure bestriding economic and political life. He is often the physical representation of personal – or Weberian patrimonial – rule: resources of the political system are his personal property; loyalty to him rather than to bureaucratic norms or procedures determines official position, and there is little if any distinction between a private and a public sector. Because Big Men have been identified across much of sub-Saharan Africa, and across much of history, the image has been a conceptual workhorse for social scientists trying to explain the complexities of African politics to students, media, policymakers and civil society actors.Footnote 1 The ubiquity of Big Men permits social scientists to generalise about the very existence of an African politics to begin with, a sort of sub-continental imaginary that permits the mental construction of an Africa that can be studied.Footnote 2 So frequently is he invoked that some scholars have said his image has become clichéd (Leonard & Straus Reference Leonard and Straus2003: 2; Therkildsen Reference Therkildsen2017).

I argue that two broad mental models exist when authors write about Big Men, but that one view is incorrect. I refer to the proper model as Big Man Governance, in contrast to an unsatisfactory mental model that is conveyed by the image of Big Man Dictatorship (the ‘boogeyman’ in my title). This latter model is the result of an unmooring of the Big Man from his original understanding. Scholars often invoke the Big Man image to explain the behaviour of dictators or kleptocrats, but, I argue, Big Men are distinct from such figures. The models differ in the following five ways. First, Big Man Governance is an (informally) institutionalised – and, thus, rule-bound – regime. As a rule-bound figure, a Big Man is accountable to others. Second, Big Man Governance achieves acquiescence through reciprocity rather than violence. Third, Big Man Governance is predictable rather than arbitrary. Fourth, Big Man Governance uses public resources to provide club goods rather than for public or private gain. Public resources are not used for public purposes, but nor are they consumed privately. Fifth, Big Man Governance connects small men to power and thus – unlike prebendalism – it is not elite-based. This article attempts to ‘put the Big Man back in his place’ by arguing theoretically and empirically that Big Men are not unaccountable thieves or despots who operate above the law.

The paper is organised as follows. In the first section, I briefly trace the emergence and spread of the concept of the Big Man in political science. In the second section, I analyse an original dataset on the discussion of Big Men, not only by political scientists, in leading African Studies journals.Footnote 3 The dataset contains 268 articles from 11 leading African Studies journals since 1980. The analysis reveals significant unevenness in how the accountability of Big Men is understood, especially among political scientists. In the third section, I describe the conceptual differences between Big Man Governance and Big Man Dictatorship. Lastly, in the final section, I draw on time spent with local Big Men in Ghanaian politics to illustrate the importance of accountability in Big Man Governance.

BIG MEN IN POLITICAL SCIENCE: A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY

References to Big Men have appeared in the field notes of researchers since before World War II, yet Big Men rarely took centre stage in the resulting scholarship. But this was not the case outside of Africa, where anthropologists studied Big Men extensively. Marshall Sahlins’ anthropology of Melanesian and Polynesian societies is the classic work.Footnote 4 Citing a wealth of anthropological studies since the 1930s, Sahlins argued that Big Men were widespread in Melanesia. In Poor Man, Rich Man, Big Man, Chief, Sahlins contrasted the politically ‘underdeveloped’ Melanesian communities with the ‘greater Polynesian chiefdoms’ (Sahlins Reference Sahlins1963: 286).Footnote 5

There were several important features of the Big Men in Melanesia. First, Big Men were powerful, but they did not rule through force: ‘It is not that the center-man rules his faction by physical force, but his followers do feel obliged to obey him, and he can usually get what he wants by haranguing them – public verbal suasion is indeed so often employed by center-men that they have been styled “harangue-utans”’ (Reference Sahlins1963: 290). In Polynesia, by contrast, a chief ‘controlled a ready physical force, an armed body of executioners, which gave him mastery particularly over the lesser people of the community’ (Reference Sahlins1963: 297). Second, Big Man systems were more meritocratic than the hereditary authority enjoyed in the monarchies or chieftaincies in Polynesia. For Melanesia's Big Men, ‘Little or no authority is given by social ascription: leadership is a creation – a creation of followership’ (Reference Sahlins1963: 290). In the struggle to become a Big Man, ‘Typically decisive is the deployment of one's skills and efforts in a certain direction: towards amassing goods, most often pigs, shell monies and vegetable foods, and distributing them in ways which build a name for cavalier generosity, if not for compassion … Merely to create a faction takes time and effort, and to hold it, still more effort’ (Reference Sahlins1963: 292). By contrast, chiefs in Polynesia could call upon labour by right of their office (Reference Sahlins1963: 295), and people working for the chief were institutionally subordinate to him. Sahlins’ work was influential among anthropologists, and it had striking parallels with African Studies that would come after Sahlins’ publications. In particular, the Big Men of sub-Saharan Africa and Melanesia appeared to have in common the importance of acquiring followers through effort rather than birthright and the need to continually feed followers.

Another important contributor to a systematic appreciation of Big Men was Weber's concept of patrimonialism (Weber Reference Weber1978). Although patrimonialism made occasional appearances in 1960s scholarship, the concept was not an immediate revolution in African Studies thinking. Thus, although Zolberg is often (and perhaps wrongly) credited with bringing Weber's patrimonialism to Africa, Foster and Zolberg's (Reference Foster and Zolberg1971) Ghana and Ivory Coast does not mention Big Men or (neo)patrimonialism.Footnote 6 Its development was not significantly advanced until the work of Eisenstadt (Reference Eisenstadt1973), Lemarchand (Reference Lemarchand1972), and Médard (Reference Médard and Clapham1982), by which time the comparative study of patron–client relations had taken off outside of Africa.Footnote 7 A lot of this literature was concerned with locating patrimonialism within trajectories of modernity or political development.

Still, by the time of Médard's classic statement on neopatrimonialism in the 1980s, he would claim it was the ‘least used’ of Weber's ideas (Reference Médard and Clapham1982: 177). For Médard, neopatrimonialism was the marriage of privatisation of the public sector – ‘the core of the concept of patrimonialism’ (177) – with ‘the bureaucratic logic’ (179). Because clientelism, nepotism, tribalism and corruption all involve the privatisation of the public sector, Médard placed them all under the umbrella of neopatrimonialism (Reference Médard and Clapham1982: 165: 171). For example, Zaire was corrupt but did not evince many patron-client relations (Reference Médard and Clapham1982: 171), while tribalism or kinship could occur among equals whereas clientelism by definition occurred among unequals (Reference Médard and Clapham1982: 172). And corruption is illegitimate, while clientelism, nepotism and tribalism are not necessarily illegitimate (Reference Médard and Clapham1982: 175).

The next important work came with Jackson & Rosberg (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982, Reference Jackson, Rosberg, Apter and Rosberg1994), who reframed patrimonialism as personal rule. Here, Big Man government was described in terms of a patrimonialism that is despotic, unpredictable and free of rules. Where personal rule is practiced, they argued, politics ‘do not conform to an institutionalised system’ (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 1). Contests for power are not undertaken ‘within an overall and legitimate framework of agreed-upon rules’. Politics is ‘not yet governed by regulations that effectively prevent the unsanctioned use of coercion and violence’, so ‘politics are more personalised and less restrained’ (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 17). But, if a social system is a set of bounded interrelationships, there is little systemic about Jackson & Rosberg's personal rule. While they said personal rule was not about the personality of the ruler, they argued that ‘the “game” of politics is without established rules and effective referees’ (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 20). Just what it means for a patrimonial ruler to be ‘personalist’ has been hard for scholars to nail down. As far back as Lemarchand & Legg (Reference Lemarchand and Legg1972: 166), for example, an important feature of patrimonialism was that it ‘is comparatively less personalised’ precisely because it is more bureaucratic than feudalism.

A tendency to imagine Big Men as unaccountable thieves and dictators continued into the 1990s, as Westerners looked for synthetic explanations of conflict and underdevelopment across the sub-continent. Typical were books such as Russell's (Reference Russell2000) Big Men, Little People: Encounters in Africa. For Russell, Zaire's Mobutu illustrated the ‘rapacity of Big Man rule and the corruption that is Africa's curse… [Mobutu's] avarice was legendary even among other Big Men. His subjects were play things to exploited at will’ (Reference Russell2000: 4). Russell depicts Big Man rule as a personality rather than an institution. To the extent factors other than personality mattered for the behaviour of Big Men, they did so by narrowing or widening the gap through which Big Man personalities emerged. Thus, the Cold War context affected Big Men, but only because its ending meant people such as Mugabe were no longer under the thumb of an international power. In the early 1990s, Russell explained, Zimbabwe was said to be ‘free of outside influence … Zimbabwe could so easily have been a triumph. Instead it is a disaster almost entirely of his own making, a monument to his greed, megalomania, and pride’ (Reference Russell2000: 315). Russell is not alone in confusing Big Man Governance with Big Man Dictatorship. The Financial Times (2016) writes that ‘many nations still labour under the yoke of seemingly immovable strongmen, including the likes of Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea (36 years), Angola's Jose Eduardo dos Santos (36 years) and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (28 years).’ The article juxtaposes ‘Big Men’ with ‘immovable strongmen’, which again downplays the importance of accountability in Big Man Governance.

Other popular accounts emphasise the greed of Big Men. One depiction for a non-African audience comes from the documentary Big Men (Boynton Reference Boynton2014). The film follows American oil executives struggling to establish oil ventures in Ghana and Nigeria. The viewer watches Ghanaian elites clamour to reap the benefits of the new oil discovery, while also witnessing the environmental and human destruction left by oil in the nearby Niger Delta. It is a fascinating depiction of greed but has nothing whatsoever to do with Big Men. It simply blurs the line between Big Men and greedy actors in the oil business.

This brief chronology of the changing ways in which Big Men have been invoked suggests that conceptual blurring has occurred, in particular on the question of the Big Man's thieving and accountability. However, highlighting misuse of academic concepts by non-academics may be a little unfair. The more important question is, how are African Studies academics invoking Big Men? To approach this question systematically, I built a dataset of Big Men in African Studies journals.

ANALYSIS OF AFRICAN STUDIES JOURNALS

Methodology

I coded discussions of Big Men in 11 leading English-language general interest African Studies journals since 1980.Footnote 8 To develop the coding scheme, I began by randomly sampling five non-contiguous years from each of African Affairs, Journal of Modern African Studies and African Studies Review. For each sampled journal-year, I used Primo and JSTOR to search ‘Big Man’ or ‘Big Men’ in the full text. I then read the pages before and after each mention of Big Men in order to code the content. Full-text searches for ‘Big Man’ or ‘Big Men’ returned 728 articles, of which 268 were found to use Big Men at least three times in the main text. Articles that were excluded from the eventual dataset typically contained Big Men in a citation, footnote, or one brief mention. This exercise was simultaneously undertaken by research assistants for inter-coder reliability, which gave me a long list of topics and Big Man descriptors from the sampled articles. I then looked for proximity between terms, such as clientelism and neopatrimonialism, or democracy and presidentialism, which gave me a pared-down set of article themes and Big Man descriptors.

The result was a simple coding scheme for the descriptors used to describe Big Men. Six descriptors were coded:

• Accountable: 1 if article depicts Big Men as accountable or responsive to people below him. The accountability of the actual figure under discussion is irrelevant. What matters is that in discussing the figure, the author appears to understand that an unaccountable Big Man is an aberration in conceptual terms.

• Dictator: 1 if article depicts Big Men as dictatorial, acting without consideration or fear of the reaction of people beneath him.

• Thief: 1 if article describes Big Men as thieves, kleptocratic or corrupt, without discussion of expectation that Big Men should redistribute rather than consume by themselves.Footnote 9

• Redistributive: 1 if article depicts the Big Men as redistributing in order to maintain power. Merely giving things away does not count.

• Personalistic: 1 if article depicts the system as personalistic, meaning the power of an office rests in the person of the Big Man rather than the office's own legal authority.

• Neopatrimonialism: 1 if article clearly links Big Men to neopatrimonialism, clientelism or patron-client relations.Footnote 10

Additionally, I coded the major theme or topic of the article. An article may have more than one major theme or topic. Most articles were coded with only one of nine themes. I also coded the article's basic descriptive data, such as the author's field or discipline or year of publication. See the tables in the Appendix for more information. After finalising the coding scheme, the full exercise was undertaken on all articles published since 1980 for the 11 journals shown in Table I. Table I can be read as follows: 104 articles from JMAS from 1980–2018 were found with mentions of Big Men, 54 of which were eventually included in the dataset, representing 20% of all articles in the dataset.

Table I Journals included in the Big Man dataset

Findings

Interest in the Big Man concept has grown over time, as shown in Figure 1. Each bar shows the number of articles in the dataset in a five-year period. Note that the dataset is inclusive of 2018, but not 2019, so the appearance of a decline is misleading. The data shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3 reveal the dominance of political scientists, anthropologists and historians in discussions of Big Men, and a heavy focus on Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya.Footnote 11 Scholarship invoking Big Men has predominantly focused on regimes, elections and violence, as shown in Figure 4. Each line represents the number of articles in a five-year period containing a given thematic focus. Recall that one article can be coded for more than one theme.

Figure 1 Number of Big Men articles over time.

Figure 2 Discipline representation.

Figure 3 Country representation.

Figure 4 Big Man themes over time.

Figure 5 shows use of Big Man descriptors over time (broken down by discipline in Figure 8, Appendix). Since the late 1990s, the two descriptors most commonly associated with Big Men are redistributive and neopatrimonial. This is an encouraging finding as it marks an awareness that Big Men are figures within a broad system – neopatrimonialism – and that a feature of these systems is redistribution of goods and services. Less encouraging, however, is the jockeying for position between descriptions of the Big Man as a thief versus as accountable.

Figure 5 Big Man descriptors over time.

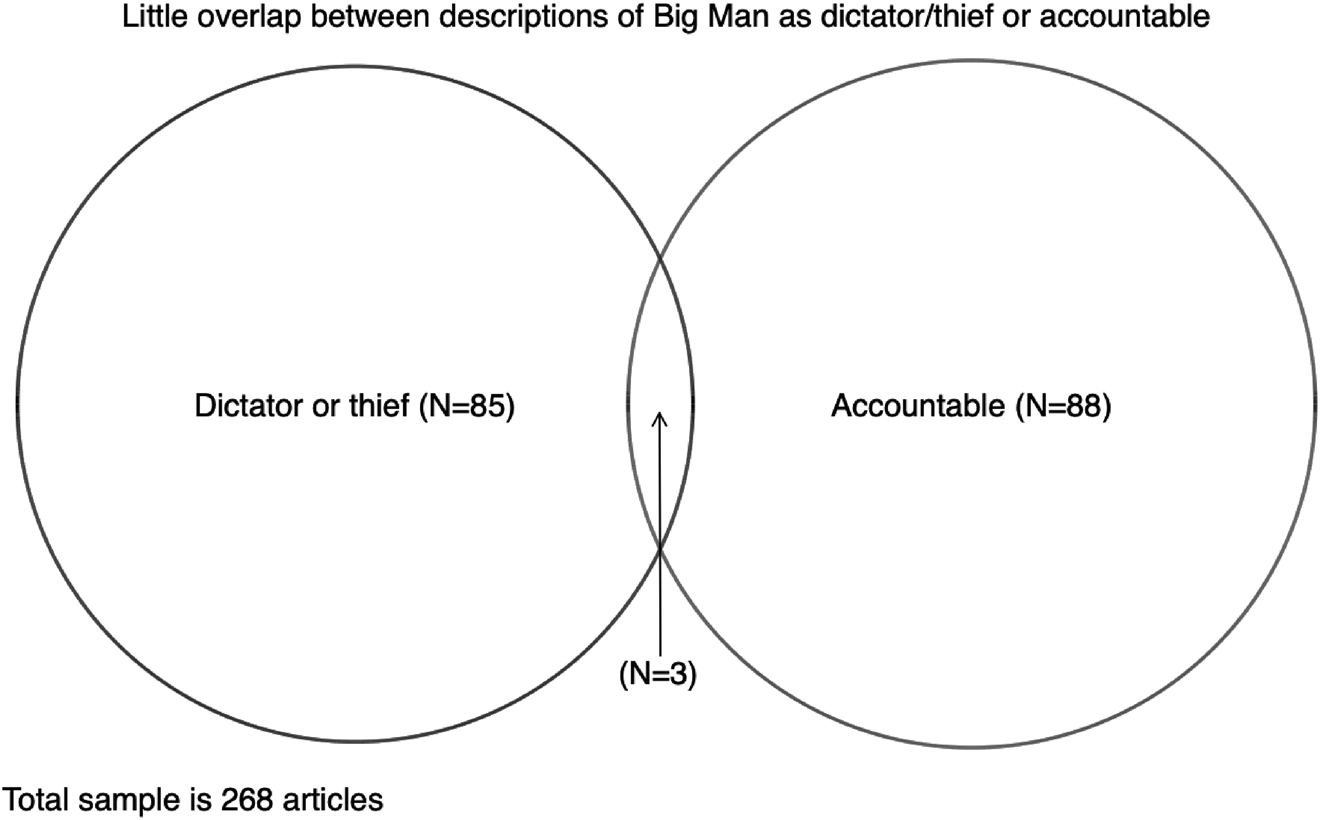

Are some authors simply muddying the waters by describing Big Men as accountable and as thieves? The Venn diagram shown in Figure 6 reveals almost no overlap between articles that describe Big Men as dictators/thieves, and those that describe them as accountable. The left circle represents the 85 articles in which Big Men are described as thieves or dictators, and the circle on the right represents the 88 articles in which Big Men are described as accountable. Few articles, therefore, describe Big Men as thieves/dictators and as accountable. Instead, scholars describing Big Men as dictators or thieves – together about one-third of the entire dataset – do not reference a core component of the Big Man, which is his accountability.

Figure 6 Venn diagram of Big Man descriptors.

Analysis of political scientists

Because the concept of the Big Man is of special interest to political scientists, and because I am a political scientist, I analysed articles in which at least one author was a political scientist. This represented 106 of the 268 articles in the dataset. The growth over time mirrors that seen in the larger dataset, with significant growth in political scientists writing about Big Men in the late 2000s. Also similar to the broader dataset is the focus of single-country articles on Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana, and unsurprisingly, the most common themes of interest to political scientists are regimes, elections and violence.

Table II shows the frequency of Big Man descriptors for all 106 articles authored by political scientists, with columns to the right offering a comparison with the whole dataset. The table can be read as follows: looking at the top row, there were 63 articles with at least one political scientist author in which Big Men were described as neopatrimonial, representing 62.4% of all articles by political scientists, compared with 49.8% of all authors in the dataset (including political scientists). Several things are noteworthy here. First, the share of political scientists describing the accountability of Big Men (27%) is significantly lower than in the broader dataset (36%).Footnote 12 This finding is striking given the basic centrality of the idea of accountability in political science, writ large. Second, by a small margin, political scientists invoke theft by Big Men more often than they invoke accountability. This is not explained by a tendency of some authors to describe Big Men as accountable as well as despotic: the Venn diagram shown in Figure 6 holds true for political scientists: only one article describes Big Men in terms of accountability and dictatorship/theft.

Table II Frequency of Big Man descriptors for political scientists

Figure 7 shows the number of articles using various Big Men descriptors over time. Again, note that multiple descriptors may be coded for one article. Similar to the whole dataset, political scientists invoke Big Men in terms of neopatrimonialism, personalism and redistribution. Yet again, a tension exists between articles emphasising the accountability of Big Men versus those emphasising theft or dictatorship.

Figure 7 Big Man descriptors over time in political science.

A clearer picture of political science scholarship emerges when examining associations between article themes and Big Man descriptors. Table III presents a visual summary of the correlation coefficients shown in the appendix (Table VI). The signs show only the correlations that are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. A plus sign means the variables are positively correlated. For example, political scientists writing about themes of violence are especially likely to use thief or dictator descriptors.Footnote 13 Authors describing Big Men in terms of accountability are likely to study chiefs or religion, while those using dictator or thief descriptors are likely to study violence or land. These findings support the view that two visions of Big Men – Big Man Governance versus Big Man Dictatorship – play out in distinct communities of inquiry that rarely overlap.

Table III Correlations between Big Man themes and descriptors

A division has arisen between articles discussing Big Men as a dictator/thief versus accountable, in particular among political scientists. Also instructive is the places in which authors discuss Big Men, since an author may discuss Big Men only in order to situate their own study and not be fundamentally concerned with the concept. The variable, Literature, is coded 1 if the author discusses Big Men only in the literature review. Analysis of Literature shows a statistically significant and negative association between authors describing Big Men as accountable and discussing Big Men in literature reviews only. Table VII (Appendix) presents marginal effects from a probit model for the probability that an article uses a variety of Big Men descriptors and does so in the literature review only. The notable finding is that an article is 20% less likely to describe Big Men as accountable if the author(s) only discusses Big Men in their literature review.Footnote 14 Moreover, this finding appears to be driven by political scientists because there is no statistically significant relationship between Literature and descriptions of Big Men as accountable in the entire dataset.Footnote 15

In sum, analysis of the Big Man dataset suggests an under-appreciation of the role of accountability in Big Man Governance. This under-appreciation appears to be exacerbated by political scientists, only about one quarter of whom describe Big Men as accountable, as well as by scholars citing Big Men only in their literature reviews. In the next section, I offer a clearer statement of what we mean when we talk about Big Men.

WHAT BIG MAN GOVERNANCE IS AND IS NOT

This section attempts to clarify what Big Man Governance is by discussing five ways in which Big Man Governance differs from the oft-implied model of the Big Man Dictator.

Big Man Governance is a rule-bound regime

Big Men are sometimes characterised as unconstrained and above the law. Of Jackson & Rosberg's (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982) three types of personal rule, one type is an autocrat such as Houphouet-Boigny who is ‘reminiscent of absolute monarchy’ (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 78), and the other is a tyrant exemplified by Idi Amin (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 80). These ‘systems do not consist of legitimate and enforceable rulers governing the exercise of power or the struggle for it’ (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 40). Similarly, Thomson (Reference Thomson2016: 117) explains how a Big Man may often change rules overnight ‘to satisfy his own personal whims’, and Moss (Reference Moss2011: 40) describes how ‘rules are subverted by the powerful’.

However, it is misleading to suggest Big Men are above rules, since a Big Man is the apex figure within a larger regime. Whereas a government is the person or people doing the act of governing, a regime is a set of rules, principles and procedures specifying how a person or group may accede to power and how power may be used (Krasner Reference Krasner1982; O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell2001: 14). Regimes function to shape actors’ expectations and thus regularise exercises of power. An individual Big Man may change, but Big Man Governance – the regime that contains the widely understood rules about how the system works – is unchanged. In other words, Big Man Governance is more than a person. It is a system containing rules that structure the behaviour of all individuals within it, including the man at the top.Footnote 16

The historic importance of Big Man Governance as a regime is illustrated by the case of chiefs, the archetypal Big Men. While the variety of political systems in pre-colonial Africa makes generalising difficult, scholars have plentiful examples of otherwise powerful chiefs who were institutionally constrained. Councils of elders were a common source of constraint. First, council approval was needed on any matters of significance. Second, council positions were hereditary and not open to royal lineages. And third, chiefs typically could not remove council members, while councils could often remove chiefs. Ayittey explains:

The paramount chief was forbidden to do anything which affected the interest of the chiefdom without the knowledge, approval and concurrence of the council … Without the authority of the council no new law could be promulgated. He could not even receive foreigners unless a member of the council was present. (Ayittey Reference Ayittey2006: 132)

This logic scaled up in larger polities. When several chieftaincies allied (or became subordinated), the result was typically a confederation rather than a centralised state or absolutist monarchy. In confederations such as the Asante or Ekiti, informal norms prevented the highest king from regularly interfering in local affairs (Palagashvili Reference Palagashvili2018: 284–5). Much like councils of chiefs, confederations were rules that constrained the power of the apex figure. Similarly, Big Man Governance is a regime, so it can become (and usually is) institutionalised, with rules that are widely understood even if unwritten, routinised (and thus predictable) and rationalised (rule-bound and non-arbitrary). Thus, Big Men are constrained, rule-bound figures.

A Big Man is not violent

In the Big Man Dictators model, Big Men are depicted as detached from the political system and as achieving acquiescence through coercion. For example, in Moss’ (Reference Moss2011) list of Africa's ‘Big Men’, the defining characteristics appear closer to dictatorship than patrimonialism; Nkrumah's Ghana ‘generated into a dictatorship’ (Reference Moss2011: 43); Kenya under Kenyatta saw ‘growing political authoritarianism’ (Reference Moss2011: 44); Idi Amin was ‘known for his eccentricities and pathological behaviour’ (Reference Moss2011: 45); and Cote d'Ivoire's Houphouet-Boigny was ‘autocratic’ (Reference Moss2011: 49), a term also used by Diamond & Plattner (Reference Diamond and Plattner2010: 54). These Big Men pacified their societies by coercion, which is an image of Big Men also found in Thomson: ‘To protect their own position, presidential-monarchs frequently resorted to the coercive resources of the state’ (Thomson Reference Thomson2016: 116). The Christian Science Monitor (2006) insists a Big Man is ‘the kind who takes power by bullet or ballot and never lets go’. Jackson & Rosberg thought personal rule was ‘inherently authoritarian’, with ‘an arbitrary and usually a personal government that uses law and the coercive instruments of the state to expedite is own purposes of monopolizing power’ (Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 23). In these accounts, Big Men use coercion and violence to rule.

In contrast to these accounts, the responsiveness of Big Men in late-colonial Africa was typically incentivised by competition from neighbouring polities and by the Big Man's reliance on governance services as a source of revenue (Palagashvili Reference Palagashvili2018: 288). As a result of colonial rule, however, it became much harder to remove chiefs. This is in part the reason for so much anti-chief sentiment in the early 20th century, as non-elites railed against the imposition of institutions that gave many chiefs access to violence and taxation. In other words, the Big Man who often emerged during colonialism was an outrage precisely because he was not a Big Man who governed through reciprocity, but rather an indomitable figure who ruled more often with violence.

Whereas the core feature of a dictator or despot is rule without consent or consultation, a Big Man who is subject to rules is accountable to at least the actors who created or enforce those rules. Big Men know this. Cultural anthropologist Mats Utas explains:

Big Men do not generally control followers. Quite the opposite; it is in the interest of followers to maintain ties with a Big Man (and it is rarely just one) because Big Men provide economic possibilities as well as protection and social security. Gathering of power and its maintenance are built on forms of reciprocity, and if the Big Man does not distribute enough largesse he will eventually lose his supporters. (Utas Reference Utas2012: 8)

Kopytoff (Reference Kopytoff1987) explained a similar dynamic in pre-colonial Africa, which allowed for the discontented to simply desert an unsatisfactory leader.Footnote 17 Vansina's seminal Paths in the Rainforests (Reference Vansina1990) goes even further back, showing Big Man Governance has existed in some African societies for centuries.Footnote 18 Approximately 1,000 years ago, the main political units were the house, village and district. Each house was led by a Big Man, who attracted wives, friends and clients, all of whom looked to the Big Man to assure security (Reference Vansina1990: 146). The Big Man had to constantly work to attract and retain his followers, typically numbering 40–50 people, who were not compelled to follow him.

Were Big Men actually dictators, the role of subjects would be to surrender to the dictators’ rule, but no more than that. In Big Man Governance, however, the role of the constituents is to provide loyalty in return for rewards. This means constituents have a role to play and are not passive recipients of the Big Man's rule. Rule through violence indicates that a ruler is not a classical Big Man.Footnote 19

Big Man Governance is predictable

The behaviour of the Big Man Dictator is arbitrary, idiosyncratic and often deranged: rules were ‘arbitrary and unpredictable … even those that started with idealistic goals frequently descended into predatory patterns or tyranny’ (Moss Reference Moss2011: 39–41). Here the image of the Big Man as an eccentric or a psychopath is informed by rulers such as Gambia's Yahya Jammeh or Uganda's Idi Amin. These images actually de-essentialise and de-exoticise Big Men, since ‘patronage, corruption, and even mass megalomania exists in all regions’ (Moss Reference Moss2011: 42). This unpredictability breeds general political uncertainty and is one reason why Big Man Dictators are so dangerous (Leonard & Straus Reference Leonard and Straus2003).

By contrast, Big Man Governance is predictable because it is a rule-bound regime. In the following example, a French colonial officer, Pierre Alexandre, recounts the mistaken belief that African community leaders were arbitrary or despotic:

Our first administrators saw the chiefs they dealt with as little more than kings or political personalities … the expression ‘negro king’ in our language suggests an unbridled despot, whereas the most bloody and, to our eyes, the most barbaric Dahomey kings, for example, were in a certain sense far more subjected to popular control than Queen Victoria to say nothing of other contemporary European sovereigns.Footnote 20

Again the distinction between a regime and government is useful: government uncertainty relates to the fate of the persons or party in power, while regime uncertainty relates to the fate of the system itself. Very often, the uncertainty in Big Man Governance concerns the Big Man himself (the government) but not the institution of Big Man Governance (the regime) as a whole. Non-elites may not know if the Big Man will last another year, but they expect Big Man Governance will remain the polity's operative structure.

A Big Man is not a thief

The Big Man Dictator is a thief. This view can be found in the Good Governance and anti-corruption approaches to development, as well as in sensationalist journalistic accounts of Africa's venal kleptocrats (Wrong Reference Wrong2000, Reference Wrong2009; Collier Reference Collier2010). As Newsweek explains:

Africa is littered with Big Men who fell hard … But still they come, with their supersize egos, their entourage of sycophants, their penchant for violence … They plunder the continent's natural resources and leave little in their wake but ruin. (Bartholet Reference Bartholet2001)

The image of Big Man rule as theft is also found in Gilley's (Reference Gilley2010) discussion of figures who ‘ran Africa into the ground after independence by ruling like village chiefs’ (Reference Gilley2010: 93). Under Big Men, Gilley writes, ‘power is concentrated in the leader who doles out favours through face-to-face relationships in order to keep himself, rather than his party, in power’ (Reference Gilley2010: 94). In other words, the purpose of the act is personal enrichment and keeping oneself in power. I argue, however, that narratives of ‘personal enrichment’ are misleading.

A source of confusion stems from how patrimonialism has been understood. Big Men are apex figures in neopatrimonial rules who control resources for the benefit of their group. Resources are not used for public purposes (Weber's legal-rational authority), but nor are they used for strictly private (primordial) purposes, since resources are not primarily consumed alone. Official position is a club good: it exists for members to enjoy while non-members are excluded. If corruption is the use of public resources for private gain, Big Man Governance is not strictly corrupt, since it involves the circulation of goods within a network rather than consumption by one person.Footnote 21 In this respect, Big Men are like bosses in the party machines in Latin America (as well as the United States’ deep history), where the goal is to keep the party in power (for example Kitschelt & Wilkinson Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013). This is what Médard meant when he wrote patrimonialism ‘does not exclude all notion of commonwealth’ (Reference Médard and Clapham1982: 180), because the language of an office that is privatised misstates that the office is actually owned by a club. Weber's own use of the term patrimonialism was not synonymous with corruption (Pitcher et al. Reference Pitcher, Moran and Johnston2009).

One of the reasons theft is associated with Big Men is because the study of corruption has an object permanence problem. The Swiss development psychologist Jean Piaget described how infants only gradually learn that what is no longer in front of them still exists somewhere. In political life, observers can easily assume that funds that vanished from the government bank account must have been consumed. Perhaps so, but funds could instead have been recycled through a political network. For example, on the eve of colonial rule, it was a common practice in many societies that a person seeking arbitration or justice would approach their chief with a ‘gift’ or payment. As Busia explained in the case of the Asante: ‘The services and tributes which the chief received were to enable him to fulfill the obligations of his office’ (Busia Reference Busia1951: 51). Such gifts were not extortion that exploited citizens who otherwise had need-blind rights to justice. Nor were gifts privately consumed.

Everything that the ruler acquired while he was in office … automatically became stool property … To make the rule effective, the administration of stool [royal] funds and property was put in the hands of the Sanaahene (treasurer). The ruler was debarred from any close contact with the stool finances. He was neither permitted to hold the scale used for weighing out gold dust nor to open the leather bag in which the gold was kept. (Amoah 1988: 177 cited in Ayittey Reference Ayittey2006: 164)

Big Men may consume more than their followers – indeed, followers may even expect especially ostentatious consumption (Chabal & Daloz Reference Chabal and Daloz1999; Daloz Reference Daloz2003) – but what matters is that Big Men channel their public resources into the hands of their group.Footnote 22

Big Man Governance connects small men to power

One of the ways the Big Man Dictator is alleged to stay in power is by distributing resources to elites with the power to unseat him. One of the common forms of Jackson & Rosberg's personal rule was princely rule. In these systems, exemplified by Senegal's Senghor or Kenya's Kenyatta, the Prince ‘tends to rule jointly with other oligarchs’ (Jackson & Rosberg Reference Jackson and Rosberg1982: 77). This oligarchy is Bayart's (Reference Bayart1993) reciprocal assimilation of elites – the cooptation or binding of elites to form a dominant group with control of the state. Mobutu – Africa's archetypal Big Man – ruled by selectively giving Congolese political and military elites access to state patronage.Footnote 23

When state offices are shared among elites to purchase political order, it is called prebendalism. Prebendalism is an elite phenomenon in which a lord might award a state office, title or concession to a small lord who fought for him (Joseph in Kasfir Reference Kasfir1984: 30). By definition, prebends do not reach down to non-elites, as Bratton (Reference Bratton, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007) explains: ‘African leaders typically used state sources to co-opt different ethnic elites to maintain political stability. The clientelism that results was not redistributive and generally benefited only a small proportion of the citizenry in more than symbolic ways’ (Reference Bratton, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007: 50; also van de Walle Reference van de Walle, Bach and Gazibo2013).

Again, colonialism altered this dynamic in many polities. As explained earlier, chiefs typically performed governance services to communities in return for compensation. This meant chiefs internalised the costs of poor leadership. But colonial rule frequently severed this link between Big Men and small men, whether by providing local rulers with fixed salaries or by guaranteeing them support from the colonial coercive apparatus. As a result, local Big Men became unaccountable despots, nurturing elite relationships at the expense of downward responsiveness (Boone Reference Boone2003).

Hence, Mobutu did not actually rule through patrimonialism at all, since local control was ultimately maintained through coercion. It is instructive that one authoritative voice often cited on Mobutu – Schatzberg (Reference Schatzberg1988) – actually showed that Mobutu rewarded loyal politicians, not that rewards effectively secured the compliance of ordinary Congolese. This elite-centrism is why Mobutu has rightly been called many things – kleptocrat, dictator, despot or tyrant – but he should not be thought of as a Big Man. Even Marshall Sahlins in Melanesia recognised that Big Men may enjoy the fruits of prestige and social elevation, but they do so because they are a politically productive force for ‘creating supralocal organization’ (Sahlins Reference Sahlins1963: 292). In other words, they are nodes that help connect and organise communities in order to connect to external communities.

‘ONLY MY OWN PEOPLE WILL GIVE ME TROUBLE’: BIG MEN IN GHANA'S DISTRICTS

One of the key Big Men at the local level in Ghana is the district chief executive, a mayoral figure in each of Ghana's 216 local government districts.Footnote 24 I spent most of 2012 conducting ethnographic and interview research on Ghana's local governments, which included time spent with chief executives. While observers emphasise the presidential or even dictatorial aspects of this local office, my data show the chief executive is a Big Man in its original sense: as the apex figure in a neopatrimonial regime that limits absolutism and theft. Beneath the Big Man are his supporters – known locally as party activists – who campaigned to bring him to power. The rules of this Big Man regime – including the relationship between district Big Men and his supporters – are widely understood by the population. In a nationally representative survey of 2,400 Ghanaian voters, respondents thought the demands of activists were generally merited: 58% agreed that the ‘demands of political party foot soldiers who toiled to get their parties elected are legitimate and should be satisfied by government’.Footnote 25 Even the General Secretary of the governing party quoted former President Mills as saying ‘party activists must be rewarded; we must understand that some get their reward in the morning, others get theirs in the afternoon and others in evening’ (Mohammed Reference Mohammed2017).

The rules of Big Man Governance in Ghana's districts are unwritten, but they can be glimpsed by outsiders when they are contravened. In the following example, angry supporters of the governing National Democratic Congress (NDC) interrupted a vetting committee of their own party tasked with reviewing applicants for public positions. The protest took place at the residence of a regional minister, where participants included the General Secretary of the NDC and the Minister for Local Government:

[Protesters] contended that some of them toiled during times of adversities to ensure the victory of the party but the party hierarchy has sidelined them during consideration for positions … According to them, there were a number of defeated parliamentary candidates in the region who should be considered for the position rather than going for somebody they claimed had not been involved in the cause of the party … [In response, the NDC said] all the names that have come up before the vetting committee were people who are known to be staunch members of the NDC. (Modern Ghana 25.2.2009)

The example is useful for several reasons. First, note the willingness of low-level party activists to confront their own party Big Men, including national-level cabinet and party figures, and at the residence of the regional minister no less. Second, note the equivalence drawn between ‘toiling’ for the party and the right to a public office, revealing a classically clientelistic understanding of government positions. Third, rather than disqualification on grounds of education, experience or character, the objectionable candidate was accused of ‘not being involved in the cause of the party’. Finally, note in the response of the NDC leadership the assurance – made publicly – that the candidates being considered for appointment to public office were ‘staunch members of the NDC’. These protestors decry the perceived failure of their co-partisan elites to live up to the protestors’ understanding of the regime's proper functioning.

In the next example, we again see the importance of office holders’ allegiance:

Irate NDC Youth in Salaga in the East Gonja District of the Northern Region last night destroyed properties and bill boards bearing the name of [NDC] President John Dramani Mahama … The Youth marched through the streets causing mayhem and threatening to set ablaze the NDC party vehicles and constituency office … The youth maintained that their protest was to send signal to President John Mahama that his decision to nominate Mohammed Amin Lukman ahead of three shortlisted candidates was not welcomed. A member of the irate Youth Seidu Aziz Jawula told Joy News that the president nominee is not known to them in the district and warned the nominee not to set his foot in Salaga. (Joy News 27.7.2013: emphasis added)

‘The nominee is not known to them’ reflects non-elite anxiety that the office holder will not fulfil the implicit contract by failing to discriminate in favour of the group. A candidate that is ‘not known’ cannot be trusted to deliver, since he did not emerge through the local party apparatus, and thus does not owe his political career to local party activists.

In my research sites, activist pressure on Big Men announced itself in daily appearances at district offices. A civil servant recounted to me a meeting held in his small office between him, the police chief and the party's constituency executive, to discuss the upcoming vote to confirm the president's nominee for chief executive. NDC activists were concerned that NPP assembly members would not attend the confirmation vote and thereby deny their man a quorum:

NDC boys wanted to bring in their own people and pretend they were assemblymen to cast votes [Laughs]. But the police chief and I refused and we insisted they would be brought to court if they tried that. So while we were in the office the NDC boys kicked in my door and smashed my desk. The chief executive doesn't have power over them. (Interview 2012a)

His comments reveal the agency enjoyed by ‘small men’ within the Big Man regime, contrary to any suggestion that Big Men is purely an inter-elite phenomenon.

The second major way in which the interests of party activists are laid bare is when they complain publicly about neglect by their party in government. Complaints are often framed in opposition to the behaviour of the party Big Men, who are seen as ‘eating’ too well at the trough of state. Activists in Tamale Central complained that regional and national executives had failed ‘to recognize their sacrifices to the party … Those who could not hitherto buy even bicycles are building mansions [and they] come to tell us that there is nothing to share’ (Joy News 27.10.2013). Note that they object to the failure of Big Men to share, rather than the Big Man's consumption, per se. Complaints of neglect are also explicitly tied to threats to abandon Big Men, as in this example from Agogo:

The youth of the party at Agogo Zongo in the Asante-Akim North District said their community deserved to be rewarded with developmental projects for their political loyalty. They said they were not comfortable with the ‘total neglect', and warned that if the situation did not change, it could affect the party's fortunes in 2016 … They bitterly complained about the poor and dusty nature of roads running through their area, and asked that this must be tackled without delay. [The chief executive] said he is determined to go every length to improve the socio- economic conditions in the Zongos … Baba Abdul-Rahman, Chief of the Zongo Community, said they were going to hold the chief executive to his word. (Ghana News Agency 18.4.2014)

These examples show activists wanted material improvements in their lives and in their communities, and they understood their relationship to their party Big Men in a contractual manner. They were not pawns to be endlessly shifted about in a political game, and they were keen to let their party leaders and the voting public know that they expected their just deserts.

And Big Men do pay the price. Aman District Chief Executive Adwoa Nti (NPP) paid a high price for shunning partisanship. When I asked her about the experience of governing NDC communities as an NPP chief executive, she was clear where her obstacles lay:

Only my own people will give me trouble. When I ran for chief executive in fact it was NPP people who tried to frustrate me. But I am experienced. As a nurse I came across difficult people all my life. One time they asked me to get rid of the district driver, because he is NDC, and to give the job to a party boy. I said to them ‘unless they are sabotaging my work, I won't get rid of them'. Truly I believe mostly good people get into politics but it is your own people who corrupt you. (Interview 2012b)

She remembered her official car being stoned by her own supporters when a rumour circulated that NDC people were benefiting from a government programme. She had received advance warning that protests were likely at a project launch she was going to attend, but stressed again that the problem was all ‘my own people’.

It is worth noting that Ghana's Big Men are not a product of contemporary multi-party politics. In post-colonial Ghana, according to Price (Reference Price1975: 150), it was almost expected that those in power would behave with the arrogance of traditional Big Men, yet selfishness and a failure to redistribute were seen as unacceptable (also Le Vine Reference Le Vine1975: 85). Nugent (Reference Nugent1995) wrote that this rule even held for the military coups: ‘While it was legitimate for Ghanaians to aspire to personal wealth, it was seen as the duty of those who governed to ensure that collective benefits were not sacrificed to purely private ambitions’ (Reference Nugent1995: 25–6). This is relevant to the object-permanence problem discussed earlier: public resources that disappear may not be consumed at all, but rather get recycled through the political network. Were a Big Man a mere thief, recycling would not be necessary. But in Big Man Governance, the very purpose of extracting public resources is to feed one's followers.

CONCLUSION

I have presented findings from an original dataset covering the discussions of Big Men in leading African Studies journals since 1980. The picture that emerges is of a tendency by some scholars to describe Big Men as thieves or despots rather than as accountable, especially when the author is a political scientist or the author only discusses Big Men in their literature review. But I have argued that Big Men are powerful yet accountable. They are closer to the Big Men of Marshall Sahlins’ Melanesia than a dictator like Mobutu. Above all, Big Men are individuals in a regime that is much larger than them. This regime contains rules about appropriate paths to power and how (and for whom) power is to be exercised. These rules are regularised, institutionalised, and thus predictable. Rules necessarily involve punishments, and the example of Ghana illustrates that violators frequently get punished, with the most boisterous protests directed at one's own Big Man. This article has attempted to ‘put the Big Man back in his place’ by describing his position as an apex figure in a neopatrimonial regime. A Big Man is not – cannot be – a dictator or a thief. Where observers of African politics see dictatorial or kleptocratic leaders, they should recognise that such systems have their own labels: dictatorship or kleptocracy. Neither bears much resemblance to Big Man Governance.

APPENDIX

Methodology

Coding the major theme or topic in an article: coded 1 if the major theme or topic of interest is:

• Regimes, including governance, democracy, or rule of law.

• Violence.

• Ethnicity.

• Chiefs, including traditional authority.

• Youth.

• Land.

• Environment.

• Elections.

• Religion.

• Other. 50 articles were coded as having themes that did not match the list above.

Coding basic descriptive data of an article:

• Author field: Author's discipline or field of study, as indicated by the department shown beneath their name on the article's first page, or by the author biography. If no discipline or department is found, I use their current academic department. Where that is not possible, or where the department is unclear, I use the primary field listed on their doctoral dissertation. Where multiple authors are found, an entry is made for each author.

• Literature: 1 if the article simply cites literature on Big Men, but otherwise is not concerned with the concept. Typically, this is mentioning Big Men in the first few pages, but not in the remainder of the article.

• Local: 1 if article mainly focuses at the local level, meaning not the central government or country as a whole.

• I also coded the name of the author(s), article, journal and year of publication.

Figure 8 Big Man descriptors over time, by discipline.

Table IV Frequency of Big Man descriptors, by discipline

Table V Frequency of themes in Big Men articles, by discipline

Table VI Correlation matrix for Big Man themes and descriptors (political scientists only)

Table VII Marginal effects from probit model for discussion of Big Men in literature review only (political science only)