Introduction

Early Renaissance medical doctors knew that diseases could not only spread directly between individuals, but also through the touching of objects (Hirst Reference Hirst1953). Protocols were therefore established for the disinfection or disposal of items that had been in contact with patients (Bianucci et al. Reference Bianucci, Benedictow, Fornaciari and Giuffra2013). It is well documented that Italy played a pioneering role in the development of hygiene measures intended to prevent the spread of epidemics. The protocols formulated at Tuscan hospitals and at the Paduan College, for example, served as models for hospitals established in England during the sixteenth century AD (Henderson Reference Henderson and Cavaciocchi2010). One of the earliest protocols, the Ectypa Pestilentis Status Algheriae Sardiniae (Angelerio Reference Angelerio1588), outlines protective measures such as the burning, cleaning and disposal of furniture, bedding, tableware and other objects that had been in contact with patients (Angelerio Reference Angelerio1588; Bianucci et al. Reference Bianucci, Benedictow, Fornaciari and Giuffra2013). In this context, in 1637, immediately after the end of a major outbreak of plague, the register of expenses of the hospital of Santa Fina in San Gimignano (Tuscany) includes a large order of maiolica ceramic wares, most likely reflecting the need to replenish the stocks disposed of during the epidemic (Vannini Reference Vannini1981: 45–46 & 48–52). Medical dumps—concentrations of objects used in or associated with medical contexts—are occasionally documented by archaeological excavations of deposits dating to the Renaissance and later, but the topic has, until now, not been the subject of cross-contextual investigation.

Furthermore, the overall number of archaeological contexts securely identified as medical dumps remains low. This situation results from the difficulties in differentiating between the disposal of medical waste versus general rubbish dumping activities. Where they have been encountered, medical dumps are either related directly to hospitals (e.g. De Luca & Ricci Reference De Luca and Ricci2013) or prisons (Lugo ai tempi del colera n.d.), or they may be the result of the deposition of the personal belongings of individual patients (Ciampoltrini & Spataro Reference Ciampoltrini, Spataro and Ciampoltrini2014). To advance the study of Renaissance medical dumps—and medical practices in general—here we present the results of our investigations of a medical dump from the second half of the sixteenth century, excavated in 2021 in central Rome. Based on a comparison with an extensive medical dump excavated in 2009, connected with the Ospedale dei Fornari (also in Rome), we argue that the newly excavated objects originally stem from the same hospital, bringing to the forefront discussions about medical disposal practices in Renaissance urban contexts.

Background

Between 1931 and 1932, the Alessandrino district of Rome was demolished as part of Mussolini's grand plans for the city, leaving little time and—plainly speaking—no interest in detailed archaeological recording of the area. Located in central Rome, on top of the remains of the Roman-period fora and between Piazza Venezia and the Colosseum, the Alessandrino district was established during the second half of the sixteenth century (Meneghini & Santangeli Valenzani Reference Meneghini and Santangli Valenzani2010: 141–230; Bernacchio Reference Bernacchio, Bernacchio and Meneghini2017; Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen2020; Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen2021).

Over the three-and-a-half centuries of its existence, the basic plan of the district and the footprints of individual buildings remained largely unchanged; the internal layouts of houses and individual room functions, however, were transformed (Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen, Presicce, Raja and Vitti2019/2020). Recent excavations conducted in an area previously occupied by the buildings of Via Cremona 43 and 44 have permitted a partial reconstruction of architectural changes and aspects of daily life from the middle of the nineteenth century to the 1930s (Corsetti et al. Reference Corsetti2022). Contextual evidence for the period between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, has proven substantially more elusive. This issue relates both to the excavation reported here, as well as to previous excavations in the forum area. Specifically, while the period is well represented in terms of material culture, the vast majority of these finds come from modern fills containing archaeological materials dated between the Iron Age (tenth to sixth century BC) and the time of the deposition (infills at Fori di Pace: Fogagnolo Reference Fogagnolo and Ceci2012: 138–49; Forum of Caesar: Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen2022). The few published examples of closed contexts containing only Renaissance material from the forum area amount to a closed sewer context in the area of Caesar's Forum (Tognocchi Reference Tognocchi, Meneghini and Valenzani2006), a waste dump in the area of Trajan's Forum (Mancini Reference Mancini, Meneghini and Santangeli Valenzani2006) and wasters from a Renaissance pottery kiln (Delfino & Meneghini Reference Delfino, Meneghini, Bernacchio and Meneghini2017).

The 2009 Ospedale dei Fornari dump

Excavated in 2009, the Ospedale dei Fornari medical dump provides unique insights into Renaissance hospital practices, the organisation of patient care, and waste disposal (Serlorenzi Reference Serlorenzi, Egidi, Filippi and Martone2010: 151–54; De Luca et al. Reference De Luca, Ricci and Serlorenzi2012; De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013). The Ospedale dei Fornari, founded in 1564, was located in Piazza della Madonna di Loreto, which today corresponds to the south-eastern continuation of Piazza Venezia (Figure 1). Hundreds of intact and semi-intact ceramic vessels were excavated from the dump, together with a large quantity of glass vessels (for a detailed publication of the ceramics, see De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013). The ceramics display a high degree of consistency in terms of typology, style and vessel capacities, the latter reflecting the needs of individual patients (for use and distribution of ceramic vessels in hospitals, see Mazzucato Reference Mazzucato1971: 12–14). Most of the ceramics were sourced by the hospital for its own use; painted letters (A.S.M.L. LORETO) on numerous vessels attest to their custom manufacture for the hospital. In addition, the presence of a small number of plates decorated with heraldic shields indicates that some patients may have brought their own ‘family’ tablewares into the hospital (De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 185, fig. 45).

Figure 1. Aerial photo with indication of the Ospedale dei Fornari in Piazza della Madonna di Loreto and the 2021 excavation area on Caesar's Forum (photograph by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

As deduced by Ilaria De Luca and Marco Ricci, once admitted to the hospital, each patient was equipped with a jug, a drinking glass, a bowl and a plate, as well as a one-handled bottle that was probably used for pouring liquid medication. Each patient was also provided with a chamber pot (De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 165). Vessels for the preparation of food were, likewise, restricted to each individual patient, as illustrated by the presence of lidded cooking vessels (Italian: pignatta) used for reheating prepared food over an open fire (Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 408). The pignatte from the dump are of small and medium capacity, suitable for containing only a single meal. The dump also yielded approximately 300 small storage vessels with glazed interiors and unglazed exteriors. Glazed pottery is cited in 1498 by the Nuovo Ricettario Fiorentino (1, 8, 1–11; Collegio degli Eximii Doctori della Arte et Medicina 1968 [1498]), the first treatise of pharmacopoeia published in Italy, as ideal containers for the storage of medical products. Similar vessels are known from other Italian sites, where they are exclusively connected to medical practices (Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 427). The filling of the containers with medicines would take place in a pharmacy facility either within or outside the hospital (Mazzucato Reference Mazzucato1990: 77–78).

The medical dump from the excavations in Caesar's Forum

During the 2021 investigations in the area of Caesar's Forum, approximately 325m south-east of the Ospedale dei Fornari site, we encountered a vertical brick-built cistern (1.1m wide × 2.4m long × 2.8m deep; context 1154) in the eastern part of the excavation area (Figures 1 & 2). Relating to the latter part of the Renaissance phase, the cistern was undisturbed by later rebuilding on the site. The cistern contained a series of closed archaeological contexts that are dated, based on the well-established typo-chronology of Renaissance ceramics and coins, to the second half of the sixteenth century. The absence of material culture from earlier or later periods indicates that the cistern had been empty when the sixteenth-century contexts were deposited, and that immediately following the deposition of this material, the cistern went out of use (Corsetti et al. Reference Corsettiin press).

Figure 2. The brick-built cistern (context 1154) during excavation in 2021 (photographs and illustration by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

Three contexts (1173, 1183 & 1197) contained a series of complete as well as fragmented ceramic vessels. In addition, a number of singular sherds pertaining to individual jugs and shallow open vessels were recovered, together with approximately 1200 fragments of thin-walled glass vessels and a range of small objects, such as coins and spindle whorls. Contexts 1197 and 1183 were separated by a thin layer of lime (context 1184), some 5–10mm thick, containing no archaeological material (Figure 3). The nature of the objects recovered from the cistern's fill, and their similarity to the assemblage from the Ospedale dei Fornari, clearly suggest that the discarded material was related to patient care (although a few of the objects from the cistern fill, such as spindle whorls and ceramic figurines, are not represented at the Ospedale dei Fornari dump).

Figure 3. Layer of lime (context 1184) deposited between contexts 1197 and 1183. Scale = 1m (photograph by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

The finds from the cistern fill can be divided into three main categories: medical vessels; vessels for the cooking and serving of food; and personal objects. Medical vessels are represented by small, intact ceramic medicine containers, identical to those from the Ospedale dei Fornari dump, and thin-walled blown glass vessels, including small footless bottles with a conical kick, and urine flasks, known as matula in the medieval Latin sources (Bynum & Bynum Reference Bynum and Bynum2016) (Figure 4). During the medieval period the visual examination of urine—urinoscopy—had become a central diagnostic tool in medical practice and remained so into the eighteenth century (Eknoyan Reference Eknoyan2007; Henderson Reference Henderson2016: 297–302). The patient's urine would be poured into a flask to allow a doctor to observe its colour, sedimentation, smell and sometimes even taste (Bynum & Bynum Reference Bynum and Bynum2016). Urine flasks can be difficult to identify in the archaeological record because they have a shape similar to oil lamps (Boldrini & Mendera Reference Boldrini and Mendera1994). Like other medical glass vessels and common glassware, they were a typical product of Tuscan glass workshops (Ciappi et al. Reference Ciappi, Laghi, Mendera and Stiaffini1995). Urine flasks are rare in domestic contexts (Boldrini & Mendera Reference Boldrini and Mendera1994; Ciarrocchi Reference Ciarrocchi, Volpe and Pasquale2009: 685, pl. 6), but are documented in large quantities in dumps found in connection with hospitals or care communities elsewhere in Rome, including the Ospedale dei Fornari (De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 190, fig. 59), the Conservatorio di S. Caterina della Rosa (Cipriano Reference Cipriano and Manacorda1984: 135–37, pl. XXX) and the Palazzo della Cancelleria (Del Vecchio Reference Del Vecchio, Frommel and Pentiricci2009: 475–80, pl. 2, nos 41–43).

Figure 4. Glass urine flasks excavated from the cistern. Scale in cm (photographs and illustrations by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

The second category of finds recovered from the 2021 dump relates to those vessels given to patients on admission to a hospital for the preparation and consumption of food. In total, 30 plain and decorated plates were recovered, closely resembling those found in the Ospedale dei Fornari dump (Figure 5; De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 176–87). Other finds in this category include a complete but fragmented jug, together with sherds from five other jugs (Figure 6); all of these are small and find close parallels among jugs from the Ospedale dei Fornari dump (De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013: 168–78). Among the small, lidded cooking vessels recovered, the majority have glazed interiors and half-glazed exteriors with painted floral decoration (Figure 7). A few plain cooking vessels are also represented; these vessels are all of small or medium size, and several show signs of exposure to fire, confirming their use for heating food. Many of these vessels find direct comparanda in the Ospedale dei Fornari dump, leaving little doubt that they were produced by the same workshop—a distinct Renaissance Rome-based production whose output is attested at several sites (Pannuzi Reference Pannuzi, Minicis and Maetzke2002). The close correspondence between the compositions of the 2021 dump and the Ospedale dei Fornari dump is striking.

Figure 5. Ligurian plate with depiction of a house, two Ligurian plates with floral decoration and a bowl decorated with a heraldic shield, produced in Emilia Romagna. All date to the second half of the sixteenth century AD. Scales in cm (photographs by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

Figure 6. Small jugs found inside context 1154. All date to the second half of the sixteenth century AD. Scales in cm (photographs by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

Figure 7. Small, lidded cooking vessels with yellow floral decoration. Roman production from the second half of the sixteenth century AD. Scale in cm (photographs and illustrations by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

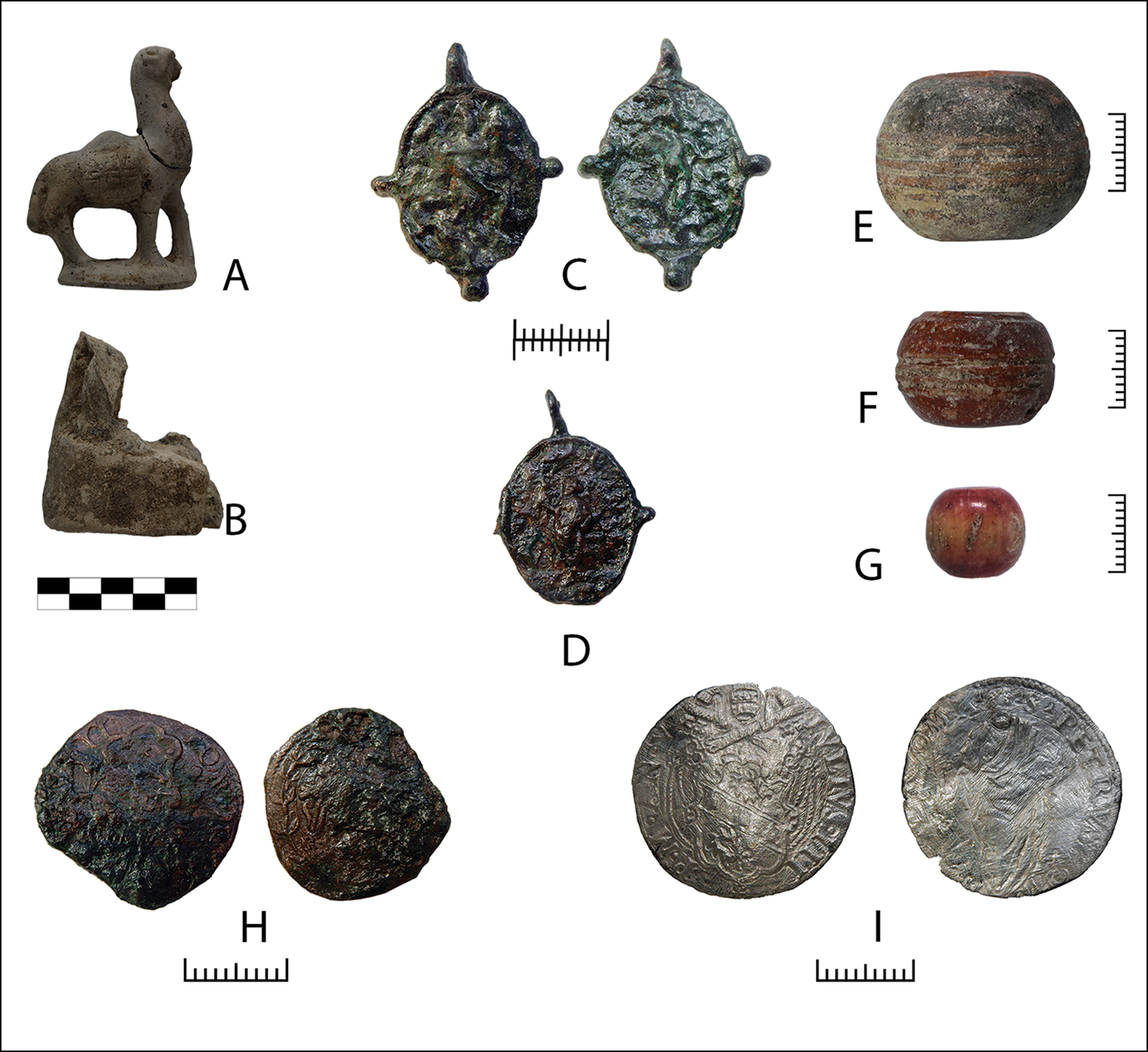

Among the personal objects recovered from the 2021 dump are a number of ceramic figurines, among which is a dromedary (Figure 8A). These unpainted, simple figurines were common during the Renaissance and they are typically interpreted as children's toys or as figurines for nativity scenes (Pannuzi Reference Pannuzi, Minicis and Maetzke2002: 169). Other personal objects include several spindle whorls (Figure 8E–F), a single rosary bead (Figure 8G), and two devotional bronze medals (Figure 8C–D), which were commonly used as the terminal component of rosaries or as individual amulets strung on necklaces or attached directly to clothing (medals: Manacorda Reference Manacorda1984: 147; Baldassarri Reference Baldassarri, Gelichi, Negrelli and Grandi2021; Bernacchio Reference Bernacchio, Presicce, Bernacchio, Munzi and Pastor2021; Renaissance spindle whorls: Lazrus Reference Lazrus and Manacorda1985: 564, fig. 129). Devotional medals venerating saints were issued on specific religious occasions, although it is not possible to specify to which occasions these particular examples relate (Altamura & Pancotti Reference Altamura, Pancotti and Dobrinić2014: 10). Also included in this category of finds are 18 coins, of which the majority are illegible; however, a silver coin was issued under Pope Julius III (1550–1555), whereas a bronze coin was issued by Pope Leo X (1513–1521) (Figure 8H–I).

Figure 8. Minor personal objects from the 2021 dump, comprising terracotta figurines, devotional medals, rosary bead and spindle whorls. Coin: Leo X, minted between AD 1513 and 1521 (bronze); Julius III, minted between AD 1550 and 1555 (silver). Scales in cm (photographs by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

A final group of objects recovered from the 2021 dump is an assemblage of 14 lead clamps, commonly used in furniture fitting (Figure 9). The clamps show variation in their dimensions, but their common features indicate a standardised use. The 10 narrow clamps all have a single horizontal cavity at one side, towards the top, and a narrow neck at the base, whereas four broad clamps have a transverse groove. Furthermore, the dump contained a notable quantity of carbonised wood. Some of these fragments have retained their original worked surfaces, demonstrating that they originally formed part of thin-walled, flat artefacts. Although currently difficult to verify, the burning of objects calls to mind measures specified in the 1588 manual by Quinto Tiberio Angelerio, cited above. Therein, instruction VII defines that “Fire must be set to mattresses, fittings, and furniture from all houses in which plague cases have been registered” (Bianucci et al. Reference Bianucci, Benedictow, Fornaciari and Giuffra2013: table 1, citing Angelerio Reference Angelerio1588), while instruction XXVI specifies that “Fire must be set to the infected objects with no peculiar value. High-value furniture must be washed; exposed to the wind; or even better, disinfected in dry heated stoves/ovens” (Bianucci et al. Reference Bianucci, Benedictow, Fornaciari and Giuffra2013: table 1, citing Angelerio Reference Angelerio1588) (Figure 10). As yet, it has not been possible on the basis of the visual examination of the lead clamps and carbonised wood to determine whether the material derives from burnt furniture or from other types of wooden objects, perhaps, for example, trays used for serving food.

Figure 9. Selection of lead clamps used in joints on furniture or wooden objects. Scale in cm (photographs by Sovrintendenza Capitolina – The Caesar's Forum Project).

Figure 10. Engraving showing furniture and objects being burnt in the streets of Rome during the 1657 plague (engraving by Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi. Wellcome Collection – Wellcome Library no. 1995i).

Connecting the medical dumps

The composition of the assemblage from the fill of context 1154 leaves little doubt that the objects pertain to a hospital of the second half of the sixteenth century. The intact or complete but fragmented vessels recovered from both dumps indicate that most of these objects were discarded while still, in principle, usable for their intended functions and that it was their contact with hospital patients that determined their disposal. If viewed as an isolated context, the material from the 2021 dump suggests a notable degree of diversity for a small assemblage, for instance in the typological variation of the plates and jugs. When compared with the material from the much larger Ospedale dei Fornari dump, however, a picture emerges in which almost all the vessels from the 2021 dump find direct parallels to well-defined groups. These similarities, together with the proximity of the two dumps, strongly suggest that all the material originated from the same hospital complex. Moreover, the consistency of the material from these two contexts is not mirrored in any other published contexts from Rome, strengthening the proposed combined reading of the two dumps. This implies that a terminus post quem of 1564—the year in which the Ospedale dei Fornari was built—should be applied to the 2021 dump. If accepted, this would make the dump the earliest known closed context so far excavated in the Alessandrino district.

The presence of a large quantity of medical glass vessels, including urine flasks, is a further common trait of the two dumps. While the new excavations at Caesar's Forum have identified many contexts yielding Renaissance material, none of these have yielded fragments of glass urine flasks. In earlier excavations in the forum, conducted between 1998 and 2000, however, urine flasks were found in two minor contexts (2450 & 4261), in association with small, intact medicine glass containers (Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsenin press), emphasising the medical function of this particular glass flask shape. The only other Renaissance Roman contexts from which a comparable quantity of urine flasks have been recovered are the dumps of the Conservatorio di S. Caterina (Cipriano Reference Cipriano and Manacorda1984) and the Palazzo della Cancelleria at Piazza Navona (Del Vecchio Reference Del Vecchio, Frommel and Pentiricci2009: 475, fig. 1). At the latter site, a large assemblage of ceramics and glass, datable to the second half of the sixteenth century, was recovered from a ditch (‘fossa 204’) on the southern side of the courtyard. The investigators of the ditch argued that, because its volume (2.20m wide × 6m long × 3.50m deep) greatly exceeds the amount of discarded material, the ditch was not originally dug with the intention to dispose of the materials recovered during the archaeological excavation; in passing, their report suggests that the reason for the dumping of the ceramics was because they had gone out of use or fashion (Termini Reference Termini, Frommel and Pentiricci2009: 231–32). This conclusion seems to be contradicted by the fact that most of the hundreds of partly reconstructable vessels were of high-quality maiolica wares. This type of ceramic was a highly prized Renaissance status symbol that was often put on prominent display in aristocratic houses. It is therefore unlikely that they would have been discarded due to changing functions or fashions (Bandini Reference Bandini2011).

Other finds strongly suggest these ceramics relate to a medical dump. Out of the 1150 glass fragments from the ditch, urine flasks/lamps comprise approximately 60 per cent, while other ceramics include miniature medicine containers, together with so-called albarello vessels, which were used for medicine storage in pharmacies. The combination of reconstructable maiolica vessels, urine flasks and other vessels associated with medicines supports our reinterpretation of this context as a medical dump. The apparently intentional sealing of the deposit by a layer of compact clay adds further weight to this argument, as this layer illustrates an urge to contain the content in the ditch for hygienic reasons.

Returning to the Caesar's Forum, the connection between the 2021 dump and the Ospedale dei Fornari dump poses the question of why material would have been discarded in two different, and widely spaced, locations. The excavators of the Ospedale dei Fornari dump suggest that when the pit was eventually filled, alternative disposal sites would have been needed (De Luca & Ricci Reference Ricci2013). At that point, the hospital appears to have diverted waste to a more distant location at Caesar's Forum. A later parallel for this kind of secondary waste disposal in Caesar's Forum was identified during excavations in 1999. Investigation of a well (context 2127) yielded a large quantity of eighteenth-century material originating from the Aracoeli monastery on the Capitoline Hill, 150m to the west (Tognocchi Reference Tognocchi, Meneghini and Valenzani2006). Ceramics with the painted letters ‘AR’ (Aracoeli) were specifically produced for the monastery and similar ceramics have been found on the Capitoline site (Distante Reference Distante2014: 22–23, fig. 7). Although some two centuries later in date, this use of Caesar's Forum for the disposal of rubbish at some distance from the material's point of use reflects that the dumping of medical waste in the sixteenth century could have been a forerunner for the eighteenth-century practice of transporting rubbish over limited distances in the forum area.

Conclusion

Defining medical dumps in archaeological contexts can be challenging because it requires an integrated approach that combines excavation data with material studies and detailed functional contextual analysis. Here, we have presented one such medical dump, excavated in the area of the Forum of Caesar in 2021. We argue that the ceramics, glass and other finds originated from the Ospedale dei Fornari, where a similar but more extensive dump was previously identified. Our interpretation of this context is based on a functional, typological and stylistic comparison of the material recovered from the two dumps. The comparison shows a great consistency between the two assemblages, which, in turn, do not find detailed similarities with other Renaissance Roman contexts. Prior to the present study, the early modern disposal of waste from hospital and medical contexts in order to prevent the spread of disease had received only sporadic archaeological attention, with limited cross-contextual investigation. In consequence, the evidence put forward here adds significantly to our understanding of waste disposal practices in the Renaissance, while highlighting the need for a more complete overview of the hygiene and disease control regimes of early modern Europe.

Funding statement

The Caesar's Forum Excavation Project is conducted as a collaboration between the Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali in Rome, the Danish National Research Foundation's Centre of Excellence, the Centre for Urban Network Evolutions (UrbNet) at Aarhus University and the Danish Institute in Rome. The project is, since 2017, funded by the Carlsberg Foundation and since 2019 by Aarhus University Research Foundation through a flagship grant. Further support comes from the Centre for Urban Network Evolutions, under grant DNRF119. The project is jointly directed by Jan Kindberg Jacobsen, Claudio Parisi Presicce and Rubina Raja.