I INTRODUCTION

Κεῖνται δὲ καὶ λίθου Φρυγίου Πέρσαι χαλκοῦν τρίποδα ἀνέχοντες, θέας ἄξιοι καὶ αὐτοὶ καὶ ὁ τρίπους.

There are also dedicated Persians of Phrygian stone supporting a bronze tripod; both they and the tripod are worth seeing.

In the passage above, Pausanias (1.18.8) describes a tripod that stood in the precinct (ἐν τῷ περιβόλῳ) of Zeus Olympios at Athens.Footnote 1 His text is our only historical source for the lost monument. No surviving part of the tripod or its foundations has been identified, despite excavations in the Olympieion and its environs.Footnote 2 Drawing on the description of Pausanias, Rolf Schneider, in 1986, offered an influential reconstruction of the tripod-bearing Persians as bent down on one knee.Footnote 3 Schneider's evidence comprised three over-life-size pavonazzetto statues from Rome, representing kneeling male figures in eastern attire, which he identified as supports for a tripod dedication (Fig. 1).Footnote 4 He argued that the statues belonged to a monument that was erected in Rome to celebrate the negotiated return of the Roman military standards from Parthia in 20 b.c. Schneider proposed that the monument in Athens was typologically analogous, and by extension, that it also dated to the Augustan period.Footnote 5 Schneider's hypothesis was upended in 2016, when Johannes Lipps published fragments of other kneeling captives from Rome that belong to the same series.Footnote 6 Lipps has shown that the statues — now numbering at least five, and more probably, at least eight, if arranged in mirrored pairs — cannot belong to a three-legged monument and must instead come from an architectural façade. The publication of this additional material demonstrates that the existence of an Augustan tripod monument in Rome is a scholarly mirage. The kneeling figures from Rome are not relevant to the appearance of the Athenian monument described by Pausanias, therefore re-opening the discussion of a reconstruction.

FIG. 1. Over-life-size pavonazzetto statue of a kneeling male figure in eastern attire. The hands and head are early modern restorations. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli 6117. (Photo: © Vanni Archive/Art Resource, NY)

II THE TRIPOD ACCORDING TO PAUSANIAS

Date

Pausanias’ description of the tripod in Athens, excerpted above, allows us to draw conclusions regarding the date, character and size of the monument; let us take each in turn, beginning with the chronology. Previous proposals for the date of the tripod have spanned the Hellenistic period to the reign of Hadrian.Footnote 7 Up to now, most researchers, in agreement with Schneider, have accepted that the tripod was an Augustan dedication. Since the date in the early Principate rests on the now re-identified kneeling statues from Rome, the evidence is due for a careful reappraisal.

The inclusion of the tripod in the text of Pausanias fixes a terminus ante quem in the early a.d. 160s. The date is inferred from Pausanias’ description of the odeion at Patras (7.20.6). While visiting that building, Pausanias issues an apology for not mentioning the Odeion of Herodes Atticus in his account of Athens. He explains that construction of the Athenian concert hall had not yet commenced by the time he finished his first book, adding that it was commissioned by Herodes in memory of his late wife Regilla. Pausanias therefore wrote his book on Athens and Attica sometime before or shortly after the death of Regilla, which probably occurred in a.d. 160 or 161.Footnote 8

A terminus post quem for the monument is established by the identification of the material used for the statues of the Persians as ‘Phrygian stone’ (λίθου Φρυγίου). Here, Pausanias is referring to a prestigious type of white marble with deep red and purple veins (e.g. Fig. 1) that was quarried near Dokimeion in Phrygia (Fig. 2).Footnote 9 The coloured stone was also known in antiquity as marmor synnadicum (after the placename of its administration and distribution: Synnada) and marmor phrygium. Today, it is commonly called pavonazzetto.

FIG. 2. Map of the Mediterranean basin showing the approximate extent of the Roman Empire in a.d. 117 and locations discussed in the text. (Drawing: T. Ross)

Systematic exploitation of the pavonazzetto-producing quarries near Dokimeion began in the late first century b.c., during the reign of Augustus, to satisfy the needs of imperial building projects in Rome.Footnote 10 The Temple of Mars Ultor in the Forum of Augustus, dedicated in 2 b.c., supplies a securely dated example of pavonazzetto in the city for architectural purposes.Footnote 11 The temple's monolithic columns and paving slabs of pavonazzetto created an impressive space for displaying the Roman military standards, which had arrived in the capital from Parthia in October of 19 b.c., following a negotiated surrender in the preceding year.

For an early use of pavonazzetto for figural sculpture, we turn to the nearby Basilica Aemilia/Paulli on the Forum Romanum.Footnote 12 Fragments of over-life-size statues of eastern figures carved from pavonazzetto were discovered in the Augustan building.Footnote 13 The statues, standing with an arm raised in a gesture of structural support, were presumably positioned in mirrored pairs below an architrave in the interior of the basilica. The general concept might have derived from the famed Persian Stoa in Sparta, which was erected in the fifth century b.c. from spoils of the Battle of Plataea.Footnote 14 According to Vitruvius (1.1.6) and Pausanias (3.11.3), the Spartan stoa employed representations of Persians to support the roof, a metaphor for the everlasting servitude of the enemy. The statues in the Basilica Aemilia/Paulli similarly alluded to the subjugation of an eastern foe, namely the Parthians, heirs to the Persian empire.Footnote 15 The difficult-to-acquire stone from Phrygia was selected for these figures in order to exoticise their eastern origin. The striking patterns created by the veined stone conveyed the stereotyped luxuriousness of eastern garments.Footnote 16 In fact, pavonazzetto was used exclusively in this context to depict fabric and attire. The separately attached faces and hands of the statues were carved from white marble, which was subsequently painted.Footnote 17

While pavonazzetto was used extensively for public building projects in Augustan Rome, it was, as far as we know, absent in contemporary Athens. One telling non-appearance occurs at the Odeion of Agrippa, a concert hall constructed in the years around 15 b.c., by the son-in-law and general of Augustus. The stage floor of the odeion was paved with slabs of white and coloured marbles, which were sourced from local and regional quarries.Footnote 18 The floor anticipates a wider pattern of use: marbles under imperial control, such as pavonazzetto, tend to be scarce outside Rome until the late first century a.d.,Footnote 19 particularly in the eastern Mediterranean basin. It was around this time that the quarrying of pavonazzetto expanded. Consular dates inscribed on architectural products from the quarries witness an intense period of extraction and shipping beginning during the reign of Domitian (the earliest inscriptions provide the date a.d. 92), with increasing demand under Trajan and Hadrian.Footnote 20 The quarries continued to be exploited in the third century and later.Footnote 21 The Prices Edict of Diocletian, issued in a.d. 301, lists pavonazzetto (Δοκιμηνοῦ) among the most expensive stones in the empire.Footnote 22

The largest recorded deployment of pavonazzetto at Athens was for the Library of Hadrian, a building complex that was presumably completed in advance of the emperor's final visit to the city in a.d. 131/2.Footnote 23 According to Pausanias (1.18.9), the structure incorporated 100 columns of ‘Phrygian stone’ (Φρυγίου λίθου) that Hadrian had donated to the city. Several fragmentary shafts of these columns survive today.Footnote 24 The same stone also decorated the walls of the library, as Pausanias further describes. Chrysanthos Kanellopoulos has identified pavonazzetto mouldings and revetment slabs that were once attached to the interior walls.Footnote 25 These colourful architectural elements created an impressive visual statement of empire in Athens.

Character

The use of ‘Phrygian stone’ also provides information regarding the character of the tripod monument. The extraction of pavonazzetto near Dokimeion was under the control of imperial administrators, and as a result, acquisition of the stone was highly restricted.Footnote 26 Even though limited quantities of pavonazzetto might have been available through non-imperial channels (e.g. for making revetment),Footnote 27 large blocks for carving figural sculpture are unlikely to have been available to private citizens. Pausanias (1.18.9) makes clear that the Athenians were able to obtain pavonazzetto for the Library of Hadrian only through imperial benefaction.Footnote 28 Coloured stones of any kind were utilised sparingly at Athens and are especially rare in the city for figural sculpture. The tripod is therefore overwhelmingly likely to have been an imperial dedication.Footnote 29

Size

From Pausanias’ account, it is also possible to draw a general conclusion concerning the size of the monument. The description of the tripod and its figures as ‘worth seeing’ (θέας ἄξιοι) suggests a colossal scale, in addition to exceptional artistry. While there is no exclusive pattern for his use of the phrase, Pausanias often deploys these words to describe very large statues.Footnote 30 At the Olympieion, for instance, he declares that the chryselephantine statue of Zeus is ‘worth seeing’ because ‘in size it exceeds all other statues save the colossi at Rhodes and Rome’ (ὅτι μὴ Ῥοδίοις καὶ Ῥωμαίοις εἰσὶν οἱ κολοσσοί, τὰ λοιπὰ ἀγάλματα ὁμοίως ἀπολείπεται) (1.18.6).Footnote 31 In the same passage, Pausanias refers to the colossal statue (τὸν κολοσσόν) of Hadrian that the Athenians erected inside or near the precinct as similarly ‘worth seeing’. Given these uses of the phrase, particularly in the context of the Olympieion, it is reasonable to conclude that the tripod caught the attention of Pausanias in part because of its large size.

* * *

To summarise, the tripod and its supporting figures, both presumably of colossal scale, were surely erected through imperial agency. The use of pavonazzetto establishes a terminus post quem of the Augustan period, but this early date seems unlikely for the monument. In Athens, the first archaeologically attested use of the stone occurs in the second century a.d. Given the patterns of use of pavonazzetto in the city, and throughout the empire, a date after c. a.d. 100 seems likely. The tripod was certainly standing by the early a.d. 160s, since it was recorded in the first book of Pausanias’ travels. Therefore, the potential donors are Trajan, Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus are improbable candidates because the main military achievements of their co-reign did not occur until the mid-160s.Footnote 32

III NEW EVIDENCE FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA

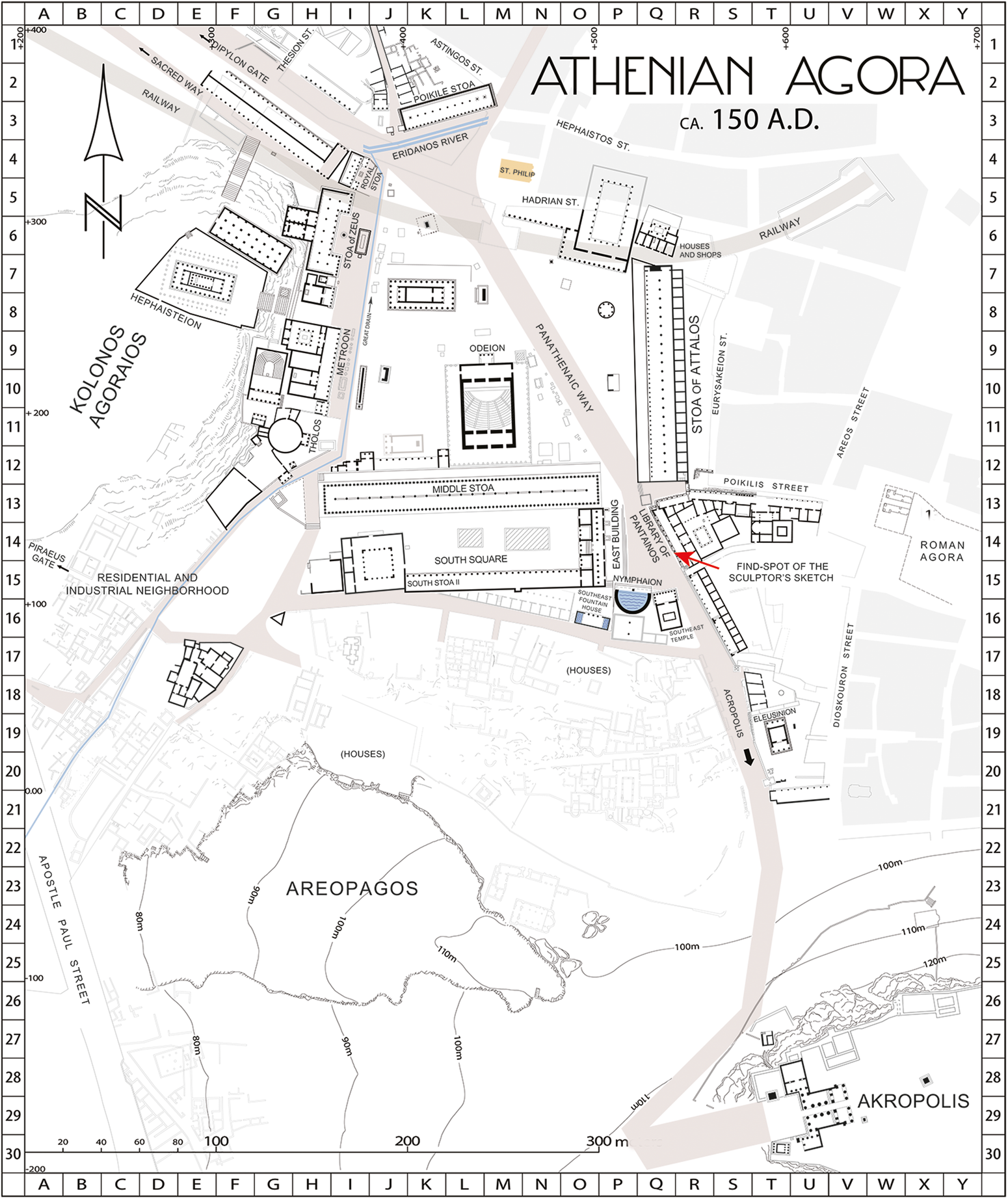

A fragmentary sculptor's sketch or model, carved from poros limestone, was excavated in 1939, from a footing trench of the Post-Herulian Wall (Fig. 3; H. 0.15; W. 0.11; D. 0.06 m).Footnote 33 The find-spot, discussed further below, establishes a terminus ante quem of the last quarter of the third century a.d. for the object. The sketch represents a standing male figure that supports, on his head, the foot of a tripod (Figs 4–5). Despite the fragmentary condition of the sculpture, the identification of the carried object as a tripod is verified by the stabilising hoop, rendered as a curved horizontal band, about 3 cm above the head of the figure.Footnote 34 The foot of the tripod takes the shape of a lion's paw, typical of ritual furniture.

FIG. 3. Plan of the Athenian Agora, with the findspot of the sculptor's sketch indicated by the red arrow in grid square Q 14. (Plan: ASCSA, Agora Excavations)

FIG. 4. Limestone sculptor's sketch from the Athenian Agora, four views. (Photos: C. Mauzy. Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.))

FIG. 5. Detail of the figure on the sculptor's sketch from the Athenian Agora. (Photo: C. Mauzy. Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.))

The figure in the sketch stands with the left leg engaged. The figure wears at least three garments: (1) trousers, rendered at the lower left leg; (2) a sleeved tunic, which is belted loosely at the waist and terminates below the knees; and (3) a ground-length cloak draped over the back and fastened below the centre of the neck by a large, disc-shaped fibula. The preserved left foot is a raised dome, without carved footwear. The head is turned slightly to the left side and bowed. The blank face is framed by medium-length hair. The facial features were not rendered, so it cannot be determined whether the figure had a beard and/or moustache or was clean-shaven. The back of the sketch is worked flat; presumably the two additional legs of the tripod were not carved because the figural type was repeated for each of the corresponding sides.

Andrew Stewart, who provided the official publication of the sketch, suggested that the figure carries something at chest level: ‘an offering tray?’.Footnote 35 Stewart mistook the pose of the figure for a non-existent object, thereby missing a critical detail: the left hand is, in fact, held over the right wrist at the level of the waist — a pose used in Roman art to represent submission and captivity, rarely deployed before the early second century a.d.Footnote 36 Stewart concluded that the figure ‘looks somewhat like a Telesphoros, but what he (or anyone else) would be doing supporting a tripod is a mystery’.Footnote 37 The distinctive pose, taken together with the costume and the function of the figure as a support, confirm that the sketch portrays a stereotyped image of a captive man. It is the only representation of a tripod–captive group known to me that survives from Greco-Roman antiquity; its importance, therefore, cannot be overstated. Given the otherwise unattested subject and the Athenian provenance, it is reasonable to propose that the creator of the sketch imitated a well-known local monument: the tripod described by Pausanias in the Olympieion.

To evaluate this claim, it is necessary to understand the sketch within its own context. Why was a sketch of the tripod created? Sculptors used three-dimensional sketches and models for the planning of figures and compositions.Footnote 38 Athenian carvers frequently employed poros limestone for this purpose because it was inexpensive and easily carved.Footnote 39 Our figure was carved almost exclusively with chisels, an approach characteristic of sketches in poros limestone. The aim was not to carve a product in detail, but to work out the overall contours of the figure and its relationship to the larger composition. While the circumstances of the related commission are lost to us today, it is possible that a request for a reduced-scale version of the monument in the Olympieion necessitated the creation of the sketch. Special meaning had accrued to the local landmark, which earlier had aroused the interest of Pausanias. Reduced-scale versions of monuments were traded in antiquity as votive offerings and as souvenirs, providing two potential uses.Footnote 40 Another possibility, although less likely, is that the sketch survived in the third century a.d., as one of the original models used in the construction of the tripod monument. Whatever its specific purpose, the archaeological find-spot of the sketch connects it to a local marble-carving atelier. The sketch was excavated from a footing trench of the Post-Herulian Wall, where the fortification passes in front of the two southernmost rooms of the west stoa of the Library of Pantainos (Fig. 3).Footnote 41 Marble chippings and unfinished works demonstrate that sculptors worked in those rooms in the third century a.d., until the building was destroyed during the Herulian raid in a.d. 267.Footnote 42 The workshop specialised in small-format works and portraiture, and the sculptors who laboured there were skilled practitioners of mechanical copying. The sketch demonstrates that the monuments of Roman-period Athens influenced local artists.

* * *

The identification of the poros limestone sketch from the Athenian Agora allows me to propose a new reconstruction for the tripod seen by Pausanias in the Olympieion (Fig. 6). In the drawing presented here, it is assumed that the statues were attached to piers that actually performed the role of supporting the bronze tripod. This structural format accords with other uses of supporting figures in Roman Athens, as for example the giants and tritons from the north façade of the Odeion of Agrippa in the Agora (Fig. 7).Footnote 43 Those colossal figures, six in total, were added during renovations to the concert hall in the mid-second century a.d. Standing with one arm raised in a gesture of structural support, they emerge from an integral pier that carried the weight of the architrave. Finally, the colossal size is consistent with the description of Pausanias (Section II).Footnote 44 The height of the supporting statues in the illustration, c. 3 m, or about twice life-size, is hypothetical, based on the dimensions of the pavonazzetto statues of Dacian prisoners from the Forum of Trajan, to which we now turn.

FIG. 6. Proposed reconstruction of the tripod monument. (Drawing: T. Ross)

FIG. 7. Triton of the north façade of the renovated Odeion of Agrippa in the Athenian Agora. (Photo: C. Mauzy. Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.))

IV PARTHIANS SUPPORTING A TRIPOD

The captive figure on our sketch displays similarities with the colossal (H. c. 3 m) pavonazzetto statues of Dacian prisoners from the Forum of Trajan in Rome.Footnote 45 Several of these statues, later transferred to the attic of the Arch of Constantine, echo the posture and composition of the tripod-supporting figure with particular closeness (e.g. the statue on the left in Figure 8). The principal difference is the composition of the cloak: the Agora figure wears the garment clasped below the sternal notch, whereas the prisoners from the Forum of Trajan wear the mantle clasped below the right shoulder, with fabric drawn around the left arm. The striking similarities support the chronological range proposed above for the monument in Athens, which I established through a contextualised reading of Pausanias’ description (Section II). The Forum of Trajan marked an early — and more probably, the first — deployment of the figural type.Footnote 46 Notably, the motif appears on coins of Trajan dated to c. a.d. 106–111 (Fig. 9).Footnote 47 On these iconographic grounds, it is possible to refine the terminus post quem for the Athenian tripod: c. a.d. 105–112, when the imperial complex in Rome was constructed.

FIG. 8. Colossal pavonazzetto statues of captive Dacian men from the Forum of Trajan, re-used in the attic of the Arch of Constantine. (Photo: D. Castor, public domain)

FIG. 9. Silver denarius of Trajan, representing, on the reverse, a Dacian captive with hands crossed in front. New York, American Numismatic Society 1882.13.2. (Photos: American Numismatic Society, public domain)

If we accept that the limestone sculpture from the Agora is a sketch of the monument in the Olympieion, then it cannot portray a Dacian prisoner. Pausanias identified the figures supporting the tripod as Persians (Πέρσαι), and by this, he surely meant Parthians, the heirs to the Persian empire.Footnote 48 In fact, ancient authors routinely referred to the Parthians as Persians.Footnote 49 Pliny (HN 6.16) makes the point plainly: ‘The kingdom of the Persians, by which we now understand that of the Parthians …’ (namque persarum regna, quae nunc parthorum intellegimus). Is it possible, then, to identify the figure in the sketch as a Parthian? Without clear prompts such as an inscription, it is hazardous to seek the ethnicity of conquered peoples in Roman visual culture, because artists drew on stereotypes to communicate otherness. Emphatically, they did not endeavour to create accurate portraits. That said, there are instances in which Roman artists incorporated realistic elements in their works, such as single items of dress, and less often, weapons or other attributes. For example, Schneider has identified a small handful of Roman images dated to the first and second centuries a.d. that represent Parthians wearing a distinctive V-neck tunic, which recalls the sleeved jacket actually worn by men in that society.Footnote 50 While this type of garment is not rendered on the sketch from the Agora, its absence does not preclude a Parthian identity.Footnote 51 In Athens, the Parthian–Persian equation probably resulted in more generalised imagery that drew on pre-existing representations of Persians in local art.

Over the course of the second and third centuries a.d., representations of conquered peoples became increasingly more typecast, and the Dacian captives in the Forum of Trajan provided a leading model.Footnote 52 For example, two colossal pavonazzetto statues (original H. c. 3.20 m) from Ephesos adopt the figural type.Footnote 53 The statues were incorporated into the façade of the East Gymnasium, a complex constructed during the Severan period.Footnote 54 The better preserved of the two statues, now in İzmir, includes a hexagonal shield resting against the left leg, and next to it, a bow and quiver. Given the architectural context, the statues have been plausibly identified as prisoners commissioned to celebrate the victories of Septimius Severus in Parthia.Footnote 55 The presence of the bow would support this interpretation because Roman authors describe it as the weapon of choice for Parthians.Footnote 56 The Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome (dedicated in a.d. 203) drew on similar visual models. The Parthian prisoners on the arch are dressed in a manner comparable to the Agora sculpture. They wear trousers and long-sleeved tunics that terminate below the knees. One prisoner, being led in chains, wears the cloak over both shoulders, with the clasp arranged below the sternal notch. These figures from Ephesos and Rome echo the general remarks of Roman authors, who describe Parthians as wearing loose-fitting garments with long robes that cover their legs.Footnote 57 The main intention of the sculptors of these monuments was not to depict reality, but to create a readily identifiable image of an eastern foe, and in particular, to associate the Parthians with the Persians. Nowhere could this equation be more salient than in Athens.

V A TRAJANIC VICTORY MONUMENT IN ATHENS

The figural type represented on the sculptor's sketch, together with the legacy of Athens as a memorial setting for Persian defeat, open up the possibility that the tripod monument commemorated Trajan's victories in Armenia and Parthia. A historical outline of Trajan's Parthian war can be reconstructed from the histories of Cassius Dio (68.17–33), whose text was epitomised by the historian Xiphilinos in the eleventh century.Footnote 58 We are told that, some time after dedicating the column in his imperial forum in May a.d. 113, Trajan departed Rome to conduct a campaign against Armenia and Parthia on the grounds that the Parthian king Osroes had violated an agreement with Rome by independently installing a new king in Armenia. On his way east, Trajan stopped in Athens, where he received an embassy from Osroes (Cass. Dio 68.17.2).Footnote 59 The Parthian delegation pleaded for peace, but Trajan reserved judgment and proceeded to Syria.

By the autumn of a.d. 114, Trajan had entered Armenia and declared the region a province (Fig. 2). In recognition of the annexation, the senate honoured Trajan with the title of Optimus. Trajan then invaded northern Mesopotamia, making it a province too. Despite a disastrous earthquake in Antioch in the winter of a.d. 115/116, Trajan continued his campaign, marching south to the Parthian capital Ctesiphon and capturing it. The senate subsequently bestowed on Trajan the title of Parthicus in February a.d. 116, and the conquest was commemorated on Roman coinage (Fig. 10). Trajan later travelled further south to the Persian Gulf. According to Cassius Dio (68.29.1), the emperor, while standing on the seashore, recalled the achievements of Alexander, remarking ‘I should certainly have crossed over to the Indian people, too, if I were still young’ (πάντως ἂν καὶ ἐπὶ τοὺς Ἰνδούς, εἰ νέος ἔτι ἦν, ἐπεραιώθην). Although he had not reached India, Trajan had brought the Roman empire to its greatest geographical extent (Fig. 2). Yet Roman control of these newly acquired regions was short lived. A series of revolts followed, and in a.d. 117, Trajan was forced to depart for Italy due to an illness, dying en route in Cilicia. His successor and adopted son Hadrian relinquished Armenia and Mesopotamia, re-establishing the Euphrates River as the eastern boundary of the empire.

FIG. 10. Aureus of Trajan representing, on the reverse, Parthian captives seated beneath a trophy. London, British Museum R.7740. (Photos: © The Trustees of the British Museum)

Memorials of Trajan's visit to Athens

Athens was an appropriate location for a memorial that celebrated Trajan's accomplishments in Parthia, for several reasons. First, as discussed above, Trajan departed for Parthia from Athens, where he had received an embassy from king Osroes — it was Trajan's only known visit to Athens,Footnote 60 and the first recorded imperial visit to the city since Augustus’ final stay, over 130 years earlier.Footnote 61 On these grounds alone, the emperor's presence must have drawn great attention.Footnote 62 The most visible impact of the visit was probably the substantial imperial entourage and the infrastructure required to support it. James Oliver suggested that Trajan was accompanied by a large military force, evidenced by epitaphs that marked the graves of Roman soldiers buried in Athens.Footnote 63 Presumably, the Roman military was stationed at Piraeus in preparation for the war and during its on-going operations.Footnote 64

Trajan's visit may have caused the Athenians to erect statues in his honour.Footnote 65 One probable example is located on the Acropolis. A statue of Trajan was added to a Julio-Claudian dynastic monument, which the demos had erected in front of the west façade of the Parthenon some time before Tiberius’ succession in a.d. 14.Footnote 66 The base of the monument, over 4.5 m long, supported statues of Augustus and his adopted family; from left to right, the inscriptions name Drusus the Younger (IG II2 3256), Tiberius (IG II2 3254), Augustus (IG II2 3253) and Germanicus (IG II2 3255). The new statue of Trajan was added to the far-right side of the base (IG II2 3284).Footnote 67 Dedicated by the Areopagos, the boule and the demos, the statue honoured Trajan as ‘god, invincible son of a god’ (θεὸν θεοῦ υἱὸν ἀνείκητον) and ‘benefactor and saviour of the world’ (εὐεργέτη καὶ σωτῆρα τῆς οἰκουμένης). The imperial nomenclature includes the title Dacicus, but not Optimus or Parthicus, narrowing the date of the statue to c. a.d. 102–114.Footnote 68 The original group had been erected to commemorate the adoptions made by Augustus in a.d. 4, which established the line of succession.Footnote 69 The addition of the statue of Trajan connected the living emperor to his predecessors, specifically through acts of adoption — meaningful for Trajan, who had been adopted by his predecessor Nerva. More importantly, the new statue, erected at a time of looming conflict with Armenia and Parthia, linked Trajan to the earlier victory achieved in these regions by Augustus and Tiberius. The martial overtones of the inscription substantiate this interpretation.

Moreover, it is possible that the designation ἀνίκητος, or invincible, recalled honours for Alexander the Great, who had conquered Persia over four hundred years earlier. According to a fragmentary speech of Hypereides (5.32) against Demosthenes, a bronze statue of Alexander was proposed in Athens naming him ‘king [and] invincible god’ (εἰκό[να Ἀλεξάν]δρου Βασιλ̣[έως τοῦ ἀνι]κήτου θε[οῦ).Footnote 70 We have no evidence that such a statue of Alexander was actually erected,Footnote 71 but if it was, Trajan's new statue was surely in dialogue with it.Footnote 72 Plutarch (Alex. 14.4) records that, before Alexander departed for Persia, the oracle at Delphi proclaimed to him, ‘You are invincible, O child!’ (Ἀνίκητος εἶ, ὦ παῖ) (see also Diod. Sic. 17.93.4). Whatever the historicity of the oracle,Footnote 73 Plutarch shows that the story was current in Trajan's day. Indeed, Trajan seems to have admired Alexander and cultivated his memory.Footnote 74 During his campaign in Parthia, Trajan stopped at Babylon and sacrificed to Alexander in the room where he died (Cass. Dio 68.30.1).

Another statue of Trajan may have been erected around the same time in the lower city. Fragments of an over-life-size Pentelic marble statue of an emperor (original H. c. 2.30 m) (Figs 11–12) were excavated from the north stoa of the Library of Pantainos, in a room that opened onto the street joining the Agora with the Roman market (Fig. 13, no. 1).Footnote 75 The emperor is represented as a victorious general. An imprisoned male figure crouches at his side, with one knee on the ground, looking sharply upward. The emperor wears ceremonial military costume, including the cuirass and the paludamentum that hangs freely from the left shoulder. The breastplate depicts Athena being crowned by winged nikai, and below this main scene, a cosmic personification spreads his arms in a supporting gesture, referring to the breadth and stability of Roman rule. Sheila Dillon recently assigned additional fragments to the statue, including the right shoulder and separately attached arm.Footnote 76 Dillon's research demonstrates that the arm was outstretched, with the hand grasping a small orb, further communicating the authority of the emperor. The quality of workmanship is exceptional. Great care was expended on the surface textures of the garments, in particular. The statue was a magnificently carved agent of imperial power in Athens.

FIG. 11. Reconstructed statue of Trajan with a kneeling captive, probably from an imperial shrine located between the Agora and the Roman market, Athens; position of the left arm unknown. (Drawing: B. Martens and T. Ross. Photos: C. Mauzy. Agora Excavations; Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.))

FIG. 12. Right arm and hand holding an orb, from the statue of Trajan. (Photo: C. Mauzy. Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.))

FIG. 13. Plan of the Library of Pantainos and the south street stoa, showing the find-spots of sculpture and epigraphy discussed in the text; green = sculptor's workshop; yellow = probable imperial shrine. (Plan: W. B. Dinsmoor, Jr, ASCSA Agora Excavations, with additions by author)

T. Leslie Shear, Jr, identified the emperor as Trajan and the kneeling figure as a Dacian. Shear reasoned that the group had been displaced from an imperial shrine, which he proposed to locate in the next room to the east (Fig. 13, yellow).Footnote 77 The adjacent room was set off architecturally from the rest of the complex (Fig. 14). Its entrance had a temple-like façade, with more elaborate column bases and wider intercolumnations than the stoa from which it projected. The spaces between the columns were occupied by statue bases, as demonstrated by the lack of wear in the places they were once positioned (Fig. 14, bottom). One of these footprints matches the dimensions of a base for a statue of Trajan that was found nearby in a re-used context (Fig. 13, no. 2); probably the base was originally positioned in the colonnade, at the entrance of the shrine.Footnote 78 The base records the dedication of a statue, c. a.d. 98–102, by the emperor's chief priest, Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes of Marathon, the father of Herodes Atticus. Additional statues of Trajan stood in the area. A second statue offered by Claudius Atticus, with a nearly identical text, was discovered at the entrance to the Roman Agora (Fig. 13, no. 3).Footnote 79 A fragmentary plaque for attachment to a base of a statue of Trajan (c. a.d. 98–117) was found in the northwest corner of the Library of Pantainos (Fig. 13, no. 4).Footnote 80 Dillon has presented pieces of a second marble statue of an emperor from the area, but its poor preservation thwarts an identification — the armoured figure presumably represents Trajan or Hadrian (Fig. 13, no. 5).Footnote 81 In all, no fewer than three, and perhaps as many as five statues of Trajan are witnessed along the street leading from the Agora to the Roman market. We recall that the Library of Pantainos complex itself was dedicated to Trajan, c. a.d. 98–102, together with Athena Polias and the city of the Athenians (IG II/III3 4,2 1405).Footnote 82

FIG. 14. Façade of room 3 of the south street stoa, probably used as an imperial shine; lower drawing shows footprints of statue bases on the stylobate. (Drawing: W. B. Dinsmoor, Jr, ASCSA, Agora Excavations)

Let us return to the kneeling prisoner as a local expression of Trajanic victory iconography (Fig. 15). The ethnic identity of the figure is difficult to pin down. Representations of kneeling captives appear on coins of Trajan only after he was engaged in war in Dacia in a.d. 101–102, and the motif is deployed most frequently on coins after a.d. 102, following his first campaign in that region.Footnote 83 This evidence suggests that the statue group dates to after a.d. 102.Footnote 84 Like the statue on the Acropolis, it is probable that Trajan's visit prompted its erection. The very high quality of the statue certainly supports the hypothesis. The surface of the statue was painstakingly finished, perhaps with the intention that it would be seen by the emperor himself. In this scenario, the captive emphasised the recent triumphs of the emperor in Dacia — a victory not referenced in the dedicatory inscription on the Library of Pantainos, which excludes the title Dacicus. Another interpretation is that the captive is a Parthian. In this respect, it is worth pointing out that the mantle, secured at the sternal notch by a large disc fibula, matches the configuration on our sculptor's sketch. If a Parthian captive was intended, then the group must date after a.d. 116, when the emperor gained the title Parthicus. Probably the ethnic identity of the kneeling figure was ambiguous even in antiquity. Ancient viewers, most of whom are unlikely to have ever encountered a Dacian or a Parthian, drew on an accumulated knowledge of visual stereotypes to recognise the captive figure as a representation of the ‘other’ — perhaps at once Dacian and Parthian. That said, at Athens, where there existed a long tradition of Persian defeat, local audiences may have preferred, consciously or not, the latter identification.

FIG. 15. Details of the kneeling captive from the statue of Trajan. (Photos: C. Mauzy. Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens City, Ancient Agora, ASCSA: Agora Excavations, © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.))

The Persian Wars tradition

Athens curated and promoted the memory of Greek triumph over eastern foes, most especially the Persians.Footnote 85 The Acropolis became a favoured setting for celebrating these victories, both mythical and historical. Alexander the Great dedicated Persian armour to Athena, after defeating Darius’ forces at the Granicus River in 334 b.c. (Arr., Anab. 1.16.7; Plut., Alex. 16.8). Some of the captured shields, with their origins triumphantly inscribed, were possibly hung on the architrave of the Parthenon — a building that was itself a testament to Persian defeat.Footnote 86 Later, an Attalid king dedicated sculptural groups on the Acropolis that linked a series of famous victories: a gigantomachy, an amazonomachy, the battle against the Persians at Marathon and a battle against the Gauls in Mysia (Paus. 1.25.2).Footnote 87 Some time between 27 and 18/17 b.c., the Athenian demos erected a round Ionic building, or monopteros, to Roma and Augustus on the Acropolis (IG II2 3173).Footnote 88 The reasons for the dedication are not well established, but its ultimate effect seems clear. The monopteros was very probably finished by 19 b.c., when Augustus, having regained the Roman military standards from Parthia, passed through Athens on his return journey to Rome.Footnote 89 The location of the monopteros, in front of the east end of the Parthenon, integrated the recent accomplishments of Augustus into the wider memory landscape of Persian defeat. Beyond the Acropolis, in eastern Attica, the cult of Livia was installed in the Temple of Nemesis at Rhamnous, most probably in connection to vengeance over eastern foes.Footnote 90 Nemesis, the goddess of divine retribution, had helped to deliver a decisive victory over the Persians at the Battle of Marathon.

In conception, the tripod in the Olympieion recalled the golden (or gilded) tripod erected at Delphi from the spoils of the Persian defeat at Plataea in 479 b.c. (Hdt. 9.81.1; Thuc. 1.132.2; Dem. 59.97; Diod. Sic. 11.33; Paus. 10.13.9).Footnote 91 The quotation of this monument, one of the most celebrated war memorials in Greece, may further explain why the Athenian tripod drew the interest of Pausanias. The inclusion of a Trajanic victory monument in the text certainly fits with his interests in the juxtaposition of the Greek past with more recent events. Pausanias’ description of the tripod immediately follows extended comment on a statue of the fourth-century b.c. speech-writer Isocrates, who had advocated intensely for an Athenian-led campaign to liberate the Greek cities of Asia Minor from Persian rule. Pausanias uses the monuments to draw a contrast: the conquered easterners are placed in a position of perpetual architectural servitude, bearing an offering, while Isocrates is elevated on a high column. The inclusion of the tripod monument in Pausanias’ text is, however, more than just carefully crafted allusion: it reflects a built landscape that propagated living memories of Persian defeat.

Another dedication to Zeus

Finally, Trajan's impending military operations in Parthia occasioned a vow to Zeus. The Palatine Anthology (6.332) preserves an epigram, composed by Hadrian, which commemorates the dedication of Dacian spoils by Trajan to Zeus Kasios. The gift is also recorded by Arrian (Parth. 36). The visit to Zeus, whose cult was connected with Mount Kasios near Antioch, occurred before the incursion into Parthia. The epigram (lines 7–10) promises more, if Zeus delivers victory over the Parthians:

ἀλλὰ σύ οἱ καὶ τήνδε, Κελαινεφὲς, ἐγγυάλιξον

κρῆναι ἐϋκλειῶς δῆριν Ἀχαιμενίην,

ὄφρα τοι εἰσορόωντι διάνδιχα θυμὸν ἰαίνῃ

δοιά, τὰ μὲν Γετέων σκῦλα, τὰ δ᾽ Ἀρσακιδέων.

But, cloud-wrapped Lord, entrust to him, too, the glorious accomplishment of this Achaemenid war, that your heart's joy may be doubled as you look on the spoils of both foes, the Getae [i.e., Dacians] and the Arsacids [i.e., the Parthian dynasty].Footnote 92

One could readily imagine that Trajan had made a similar vow to Zeus Olympios in Athens, before departing on his expedition.

VI COMPLETION OR COMMISSION UNDER HADRIAN?

The period between the presentation of the title of Parthicus to Trajan in February a.d. 116 and the emperor's death in August a.d. 117 leaves little time to organise the construction of an elaborate victory monument in Athens. There is, in fact, no surviving memorial anywhere for Trajan's Parthian War.Footnote 93 According to Cassius Dio (68.29.3), commemorations had been planned in Rome. Following the capture of Ctesiphon, a triumphal arch (ἁψῖδα … τροπαιοφόρον) was commissioned in the capital in honour of Trajan, and ‘many other’ tributes were planned in his forum; how those efforts materialised is unknown. Trajan was commemorated in Rome after his death with celebration of games called the Parthica (Cass. Dio 69.1.3).

A scenario deserves consideration with regard to the compressed timeline: did Hadrian complete, or even commission, the tripod monument after the death of Trajan? The emperor's unexpected death fuelled suspicion about Hadrian's legitimacy as successor. Cassius Dio (69.1.1–4) presents unease regarding the circumstances of Hadrian's adoption by Trajan, insisting that it was Trajan's wife Plotina who had made the arrangement (see also SHA, Hadr. 4.10). Some degree of controversy would help to explain Hadrian's special attention to his predecessor during the early years of his reign. In Rome, for example, Hadrian enlarged the Forum of Trajan with the construction of the temple for his adoptive father (SHA, Hadr. 19.9).Footnote 94 Amanda Claridge argued that Hadrian also commissioned the narrative frieze carved on the Column of Trajan as a modification to transform the structure into the emperor's tomb.Footnote 95 In Pergamon, the porticoes framing the Temple of Zeus Philios and Trajan were completed during the reign of Hadrian.Footnote 96 Furthermore, the statue group inside the temple, at first comprising figures of Zeus and Trajan, was reconfigured with the addition of a statue of Hadrian. The group presented, in acrolithic form, divine and familial ties.

In Athens, too, Hadrian actively promoted the memory of his adopted father. A remarkable example of the carefully curated dynastic relationship was on display on the Athenian Acropolis. An inscribed plaque, once affixed to a base for a statue of Hadrian, declares the emperor the ‘son of god Trajan Parthicus Zeus Eleutherios’ (IG II2 3312 + 3321 + 3322). Antony Raubitschek, who restored the inscription, argued that the plaque could belong to the base of the statue (εἰκόνα) of Hadrian that Pausanias (1.24.7) recorded inside the cella of the Parthenon — the only portrait statue that the ancient traveller remembered seeing in that space.Footnote 97 The identification of Trajan with Zeus Eleutherios (‘of freedom’) — the god who helped the Athenians defeat the Persians at Plataea — likely derived from the emperor's victories in Parthia, as suggested by the title Parthicus, the only part of the imperial nomenclature included in the text.Footnote 98 If it were displayed inside the Parthenon, then the inscription would, in effect, have elevated Hadrian as the brother of Athena, both being children of Zeus, as Raubitschek observed.Footnote 99 The inscribed text thus performed double duty: to emphasise the legitimacy of Hadrian and to exploit a fictitious genealogy that promoted sacred bonds between Athens and Rome. The relationship was evoked in the lower city as well. Pausanias (1.3.2) records a statue of Hadrian that stood in front of the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios alongside a statue of the god.Footnote 100 The large marble torso of Hadrian found nearby is surely the same statue, given the find-spot and scale (original H. c. 2.75 m).Footnote 101 On the cuirass of that figure, Athena is crowned by nikai while standing on the she-wolf of Rome.

There are further indications that the tripod monument may have been dedicated after the death of Trajan. First, Pausanias (1.18.6) associated the precinct of the Olympieion with the interventions of Hadrian, not least because of the many statues of the emperor he saw there. He and other authors record that Hadrian oversaw the dedication of the Olympieion (Paus. 1.18.6; Philostr., V S 533; Cass. Dio 69.16.1; SHA, Hadr. 13.6), even though the superstructure of the temple seems to have been largely completed before his reign. Second, Pausanias (1.18.9) indicates that the use of pavonazzetto was extensive at Athens under Hadrian, who had gifted 100 columns of Phrygian stone to Athens for the construction of a library complex (Section II). It is plausible, therefore, that the monument was completed early in the reign of Hadrian. Whether it was commissioned initially by Trajan or posthumously in his honour cannot be determined on the present evidence. The war in Parthia was, at any rate, of special significance to Hadrian, who had accompanied Trajan on the campaign.

VII THE LEGACY OF THE TRIPOD MONUMENT

The existence of the sculptor's sketch in a mid-third-century a.d. context suggests that the tripod drew admiration in its later life, evidently enough to be desirable in small format for private consumption (Section III). The sketch reveals that it was not only the sculptured monuments of Classical and Hellenistic Athens that were copied. The motif of the standing captive easterner was redeployed elsewhere in Achaia, asserting the wide resonance of the visual model. The colossal male architectural supports of the so-called Captives’ Façade at Corinth share general similarities with the figure represented on the sculptor's sketch. The colossal figures have been assigned to the south side and main entrance of the basilica located along the Lechaion Road, which opened onto the Forum.Footnote 102 The upper colonnade of the façade seems to have comprised four to eight figures engaged to rectangular piers, each with its own figural base and Corinthian capital. The figures represent both male and female subjects, presumably alternating in the composition.

The most complete figure stands 2.57 m high (Fig. 16). The figure is dressed in eastern attire: a thin, sleeved tunic with trousers; a heavier, loose garment tied over the waist; and a back-mantle, clasped in a central position below the neck. One arm is crossed over the torso; the other was probably raised toward the chin. The captive has curly, shoulder-length hair and wears a pointed cap made from soft fabric. A relief figure on a base for one of the engaged statues shows a captive male figure with hands in a different position: crossed over the waist. The date of the façade has not been resolved, but there is general agreement that it was erected in the mid-second to early third centuries a.d. Researchers have associated the façade with the Parthian victories of Lucius Verus or Septimius Severus.Footnote 103

FIG. 16. Colossal male figure from the Captives’ Façade, Corinth. (Photo: Petros Dellatolas. ASCSA, Corinth Excavations)

VIII CONCLUSION

This article has corrected the identification of a limestone sculptor's sketch from the Athenian Agora as a captive male figure supporting the leg of a tripod. Specifically, it has proposed that the sketch represents the tripod recorded by Pausanias in the Olympieion. The newly revealed iconography of the supporting figures, coupled with Pausanias’ identification of their material as Phrygian stone, has led to the conclusion that the tripod monument was dedicated following Trajan's victories in Parthia. The emperor's military achievements in the region, however fleeting, warranted commemoration: Trajan brought the Roman empire to its largest extent, and he was the first Roman to take the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. The tripod monument was probably completed after the death of the emperor. Whether the dedication was commissioned by Trajan or Hadrian cannot be answered on the present evidence; arguments have been presented above for both scenarios. The monument sheds new light on Trajanic Athens, and in particular on the effect that the emperor's visit in a.d. 113 had on the city. Trajan's decision to meet the Parthian embassy in Athens, where victory over the Persians was celebrated widely, was deliberate. The erection of the tripod in the Olympieion positioned the accomplishments of Trajan in this centuries-old tradition.