In Lev Tolstoi's War and Peace, the icon of the Smolensk Mother of God is carried behind the army as protectress and patriot. Soldiers run to bow to the icon and the battle-weary General Kutuzov himself kneels before the image traditionally credited with Russia's victory over Napoleon. This blend of military imagery and religious symbolism is not unusual in Russia, where “palladium” icons—notably, but not limited to, the Kazan, Smolensk, and Vladimir Mother of God types—have long stood on the front lines of military, political, and cultural battles.Footnote 1 Throughout the tsarist period “[t]he production and reception of an icon were not simply attributable to the iconography and the individual believer, respectively, but involved broader religious, cultural, and even political processes.”Footnote 2 Since the fall of the Romanov dynasty no Russian or Soviet leader has capitalized more on the image of Orthodox icons than Vladimir Putin, whose extensive public engagement with icons has produced a post-Soviet political lexicon that signals his political will and favor.Footnote 3 More broadly, Orthodox icons in Russia—with their intense symbolism and propensity throughout history to assume national significance beyond the ecclesiastical context—have become for Putin a form of political discourse that conveys a loose ideology of the sacred in foreign and domestic affairs.Footnote 4 Contemporary concepts like Aleksei Lidov's “hierotopy,” Sergei Avanesov's “cultural-semiotic transfer,” and semiotic studies on Orthodox icons provide a theoretical framework to describe the mechanism through which Putin's language of the icon creates sacred time and space.Footnote 5 Within this framework, the following principles emerge: the icon is intrinsically spatial and essentially political; interaction with icons is an act of creativity and generates the “sacred”; ritual engagement with icons builds social constructs like national identity and political alliances, as well as defining disputed territory, whether that be a land mass or historical narrative.

The present study uses these same principles to examine over twenty years of data about Putin's encounters with icons as a symbolic language of political discourse on the “sacred” that ultimately devolved into Russia's violent escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014-present) in February 2022. It considers how semiotic signaling through iconographical forms allows Putin—like earlier leaders of Russia—to strengthen his political power by sacralizing his leadership, a dynamic acknowledged by supporters and challenged by opponents via a similar lexicon of iconographical imagery. Next, it demonstrates how Putin re-sacralized Russian territory beyond Moscow with Christmas visits to midnight church services, where his interaction with icons highlights national security priorities for a domestic audience. Finally, the essay shows how Putin's soft power use of icons establishes “sacred” (and thus defendable) space beyond Russia's national borders, underscoring the fundamental relationship between violence and the sacred.Footnote 6

The political semiotics of icons (the ultimate insider's language) uses religious symbolism to communicate non-ecclesiastical meaning and relies on deep historical associations between icons and political power in the Russian cultural consciousness. By the fifteenth century, such links allowed Moscow, thus imagined as “sacred empire,” to claim the mantle of “Third Rome” from a captive Constantinople.Footnote 7 Four hundred years later, the early Soviet state invoked familiar iconographical forms—albeit stripped of religious significance—to construct its own language of power.Footnote 8 This “language of symbolic practice and communication” was readily understood in Soviet Russia's “highly visual culture dominated, above all, by icons of the Russian Orthodox Church.”Footnote 9 It allowed the Bolsheviks to invoke iconographical imagery in posters and visual propaganda in order to ideologically shift the center of the “sacred” from concepts like the Third Rome and New Jerusalem to the Workers’ Paradise.Footnote 10 Despite the efforts of the Soviet state to erase religious icons from daily life, the images remained persistent cultural referents.Footnote 11 By the post-Soviet 1990s, an ideological void reenergized the idiom of iconography, which again formed a visual and ritual lexicon that shaped public and political discourse on the spiritual “rebirth” and “renewal” of Russia and its common cultural values. The Putin administration has also used the icons’ symbolism as a “solacing factor” to rekindle a sense of national unity and reestablish Russia's geopolitical significance, framing the language of icons in terms of national security.Footnote 12 Modern social media and the Kremlin's website in particular provide a digital performative space where Putin curates his interactions with icons to characterize the messianic nature of his leadership and his understanding of Russia, its history, and its future in terms of sacred space and time.Footnote 13

Icons and their sacred narratives (skazaniia) have long reflected major geopolitical shifts in Russian history—from the rise of Muscovy to fall of the Soviet Union—and the struggle for sacred space at the heart of political ideologies and the national consciousness.Footnote 14 Taking advantage of post-Soviet nostalgia for familiar symbols and the well-honed ability of the populace to perceive the encoded rhetoric of Soviet-era “Aesopian” language, Putin was able to quickly develop the visual language of icons into a “special political code.”Footnote 15 From the early 2000s, Putin promoted the icon as a symbol of a reborn Russia, a “sacred canopy” that unites citizens of the Russian Federation under a shared set of all-encompassing political, social, and spiritual values.Footnote 16 Over the next two decades, as Russia's President and Prime Minister, Putin's official schedule included hundreds of public and ritual interactions with icons—a program of sacred symbolism that was perceived as a “fresh political tradition.”Footnote 17 Averaging ten to twelve times per year, these engagements include the commemoration of holidays (Christmas, Easter, Epiphany, and the Day of National Unity); religio-cultural visits to icon exhibitions, restoration projects, churches, and monasteries; international meetings with the Russian diaspora, foreign leaders, and representatives of the Orthodox Church; and political events related to his own election and inauguration. Putin's highly performative interaction with icons evoked a dual response. On one hand, it elicited imitation and compliance from his supporters, who accept the notion that such ritual carves out sacred Russian space. But the familiar image of Putin with an icon also provoked protests from others, who, ironically, appropriated icons and their visual language to counter Putin's politics of the sacred (the Pussy Riot controversy provides a prime example).Footnote 18 Both responses, however, demonstrate an understanding of the Orthodox icon's complex symbolism and the role it plays in the struggle over what a reborn Russia might look like.

Blessing the Putin Administration: The Sacralization of the Monarch

Throughout Russia's history, the identification of rulers and ruling families with certain icons endowed the monarch with authority that derived from rights considered political and religious. Putin is not perceived as “earthly tsar” in the tradition of Russia's emperors. Nevertheless, his programmatic and ritualistic engagement with icons reanimates the messianic and imperial tradition in Russian politics by which the state is regarded as the sacred center of an exceptional nation with a uniquely redemptive mission.Footnote 19 Already before his first inauguration, Putin linked himself and his presidency with icons closely associated with the Russian monarchy, like the Feodorov icon of the Mother of God.Footnote 20 Twice he sought the blessing of the Feodorov icon when he visited Archimandrite Ioann (Krest΄iankin) near the Estonian border at the Pskov-Pechersk Monastery on May 2 and August 2, 2000.Footnote 21 When Putin's first election victory fell on this icon's feast day (March 27), its role as protectress (pokrovitel΄nitsa) of Russian leadership was noted in several sources sensitive to such correlations.Footnote 22 Inauguration day in 2000 was equally rich with iconographical symbolism; the date was shifted to a feast day of the Iveron icon of the Mother of God (May 7), a “gatekeeper” (vratarnitsa) icon of the Kremlin.Footnote 23

From thereon in, as both Russian President and Prime Minister, Putin continued to invoke the history and symbolism of icons to strengthen the association between the sacred and his administrations. A prime example and one of Putin's first acts as president-elect was the modified choreography of the inaugural ceremony that introduced the now standard prayer service (moleben). This service includes the veneration and presentation of icons that symbolically emphasize important attributes of Putin's leadership—especially the task of defending and protecting the nation. At this brief service in 2000, Patriarch Aleksii II (Ridiger) gifted the Kremlin two icons of the types that, like the Iveron, have traditionally hung over the Kremlin's most revered gates—the icon of Saint Nicholas of Mozhaisk for the Nikolskie Gates and a mosaic Savoir Not Made by Human Hands icon for the Spasskie.Footnote 24 He also presented Putin with two “northern” icons, the Tikhvin Mother of God, a “protectress” (zastupnitsa) icon associated with Russia's tsars and Russia's perceived status as “Third Rome,” and the icon of Sainted Aleksandr Nevskii.Footnote 25 The Patriarch first suggested the exceptionalism that would soon take shape in Putin's presidency when, presenting the latter icon, he voiced the hope that “the defender (zashchitnik) and protector (pokrovitel΄) of the Russian lands Saint Aleksandr Nevskii would likewise act as a heavenly defender (nebesnyi pokrovitel΄) of the President and his administration.”Footnote 26 In 2004, Patriarch Kirill (Gundiaev) offered Putin the blessing of the Tikhvin Mother of God icon, whose triumphant return to Russian soil from Chicago that same year was timed to coincide with national elections. This practice of blessing the president with icons continued through Putin's 2018 inauguration.Footnote 27

Since his first inauguration, as a new millennium began and Russia focused on its “rebirth” (vozrozhdenie), both iconographical and verbal language used to describe the Putin presidency has echoed the dynamics of sacralization. When Patriarch Aleksii II requested during the inaugural prayer service in 2000 that the president “remember the enormous responsibility of the leader before the people (narod), history, and God,” he sent a clear message about the quasi-sacerdotal nature of Putin's presidency.Footnote 28 Over the course of Putin's presidential administrations, the evolution of ritual at the inaugural prayer service has underscored this message. By 2018, no longer accompanied by his wife or Dmitrii and Svetlana Medvedev, Putin entered the Annunciation Cathedral alone and stood with the clergy throughout the ceremony.Footnote 29 The well-scripted choreography of the inaugural prayer service suggested a liturgical role for Putin, who kissed and bowed to an icon as a correlate of the traditional anointment that conferred priestly status on the monarch. With the restoration of icons to its gates and towers and religious rituals included in the inaugural festivities, the Kremlin under Putin seemed once again to represent not only the seat of Russia's political power, but its sacred center as well.

For Putin, the most potent use of the iconographical image was the sacralization of his own leadership beyond inauguration day. Putin's inaugural prayer service is held in the Kremlin's Assumption Cathedral rather than the Dormition Cathedral (where Russian emperors were anointed and enthroned), but parallels with coronations are notable.Footnote 30 Most striking is the new ceremony's familiar invocation of what Viktor Zhivov and Boris Uspenskii call the “semantics of sacralization”—the ritual symbolism of coronations that represented the power of Russian monarchs in messianic terms and created affinities between them and heavenly archetypes.Footnote 31 Seventeenth-century changes to such ceremonies in Russia evoked Byzantine ritual gestures that endowed emperors not just with priestly status (akin to the Roman concept of pontifex maximus), but with the imagery and charisma of God, Christ, the Mother of God, and the saints.Footnote 32 After the coronation, the process of sacralizing Russia's emperors and empresses continued to draw on iconographical imagery through visual and written texts like portraiture, prayers, and odes, and panegyric literature that imbued the leader with God-like qualities.Footnote 33 Notably, these forms of textual sacralization (which also reinforced the notion of the divine legitimacy of rulers with classical references) did not always align with the gender of the leader. In works by Aleksandr Naryshkin, Aleksandr Sumarokov, and Mikhail Lomonosov, for example, Catherine II and Elizabeth are described as “earthly God” (or Zeus) while Peter is compared to the virgins who went to meet the bridegroom (or Pallas Athena).Footnote 34

Putin's supporters and opponents alike quickly turned to the language of icons to amplify or challenge the dynamics of sacralization. As Zhivov and Uspenskii note, the semantics of sacralization emerge most clearly in the conflicts that arise between those who drive the cult of leadership and those who oppose it. Whether arguing for sacralization or claiming blasphemy, both sides use a similar lexicon.Footnote 35 Thus, when Putin's popularity wanes and the voices of the opposition are loudest, the idiom of the icon intensifies and its use grows more prevalent. This tendency was particularly obvious during the 2011–12 election cycle when widespread popular protests garnered a strong response from Putin's backers. A case in point is the “Prayer to Putin” (Molitva Putinu) released online on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday in October 2012 by the “National Committee +60” (Natsional΄nyi komitet +60), the extreme pro-Putin activist group that continues to propose such sacralizing ideas as the production of an icon of Putin himself.Footnote 36 For its prayer, the group repeated much of Nikolai Gogol΄'s “Prayer” (Molitva), first published in 1894 by the Kyiv-Pechersk Monastery as “Hymn to the Most Holy Virgin Mary the Mother of God” (Pesn΄ molitvennaia ko Presviatoi Deve Marii Bogoroditse). The implicit comparison between the subjects of both works—the Mother of God and Putin—offer an unlikely and perhaps unintentionally ironic imitation of the sacralizing texts of earlier centuries.Footnote 37 (Table 1)

A literary version of the akafist hymn, Gogol΄'s text imagines a supplicant praying before the Impenetrable Wall (Nerushimaia stena) Mother of God icon that shows Mary at full height in the ancient orant or “prayer” pose of the intercessor (zastupnitsa). The Ukrainian-born Gogol΄ may have envisioned the impressive eleventh-century mosaic version in the apse of Kyiv's Saint Sophia Cathedral. This icon has remained undamaged since its creation and is regarded as the city's protectress, a role Gogol΄'s “Prayer” underscores with ecclesiastical language referring to the protecting veil (pokrov) of the Mother of God and the defensive boundary (ograda) she provides.Footnote 40 In the “Prayer to Putin,” allusions to Saint Vladimir Iaroslavich of Novgorod (“faithful Vladimir”) and the “apostle of Peter's city” emphasize Putin's northern roots and, through the Gogolian subtext, characterize him in terms of the icon. In the “prayer,” Putin assumes roles attributed to the Mother of God—intercessor, guide to salvation, and merciful defender of the faithful. The distinct descriptors (the Mother of God icon is “Protectress” and “defense” while Putin is “Pillar” and “reward”) also link the subjects through the similarity of sounds in Russian; pokrov and opora echo each other in reverse (po-/op- and -ro/-or), while ograda and nagrada rhyme.

Regardless of form and genre, ties between Putin and icons were clearly registered by the public and permeated public discourse on both sides of the political spectrum. Pussy Riot's “Punk Prayer” (Pank moleben, 2012) created a verbal icon that, in contrast with the “Prayer,” entreated the Mother of God to “put Putin away.”Footnote 41 The group's detention generated like-minded street art, tee shirts, and internet memes that also used iconographical images.Footnote 42 Broad public understanding of the semiotics of these icons in Russia is perhaps attributable to the ubiquity of their images. Historically, Orthodox icons in Russia were not bound to the churches and monasteries that housed them; they were frequently processed through streets and the countryside, building the perception of Russian expanses as sacred space or even, as Oleg Tarasov notes, a “Great Icon” itself.Footnote 43 Accordingly, Putin does not confine his ritual interactions with icons to the sacred center of political power behind the Kremlin walls, but performs them for receptive domestic audiences in the smaller Russian cities and towns he visits regularly on political, economic, and cultural working trips. No such event is more potent in iconographical symbolism and semantic richness than Putin's annual attendance at Christmas Eve services, where his association with icons underscores the sacerdotal nature of his presidency while reinforcing his role as protector of the nation. As he draws icons into politics in the Kremlin, Putin also draws politics into icons as he travels the country.

Putin's Christmas Presence

Since 2002, Putin's ritualized visits to regional Christmas Eve church services have delineated sacred space (hierotopy) and time across the vast expanse of the Russian Federation. For the first two years of his presidency, Putin attended services alongside public figures and politicians at Moscow's Church of the Life-giving Trinity on Sparrow Hills (2000) and the Cathedral of Christ the Savior (2001). After that—except for four visits to his native St. Petersburg—Putin joined 150–300 worshippers in smaller towns and cities away from the capital.Footnote 44 The choice of venues for these visits is deliberate and can be read as a response to national concerns that include the desire to curate Putin's domestic image or cultivate local political influence, Russia's hosting of the Olympic Games, and military actions in Syria and Ukraine. As with the staging of post-inaugural prayers, the choreography of Putin's Christmas appearances has developed into a performative and politically charged ritual. After greeting townspeople outside, a casually dressed Putin enters the brightly lit church at midnight to the ringing of bells. He wishes worshippers a happy Christmas, lights a candle to the Nativity icon, and prays during the liturgy, surrounded by children. Some regard this “out of Moscow” (proch΄ ot Moskvy) policy as Putin's attempt to discourage perceived support for factions within his government that promote “Orthodox” ideology. “Time and time again at Christmas we see this picture,” writes one observer, “a lot of high placed officials are at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior (their make-up constantly changes), but the president is not among them.”Footnote 45 But this reading only goes so far, since Putin routinely attends Easter service in Moscow with the same government officials he purportedly avoids at Christmas.

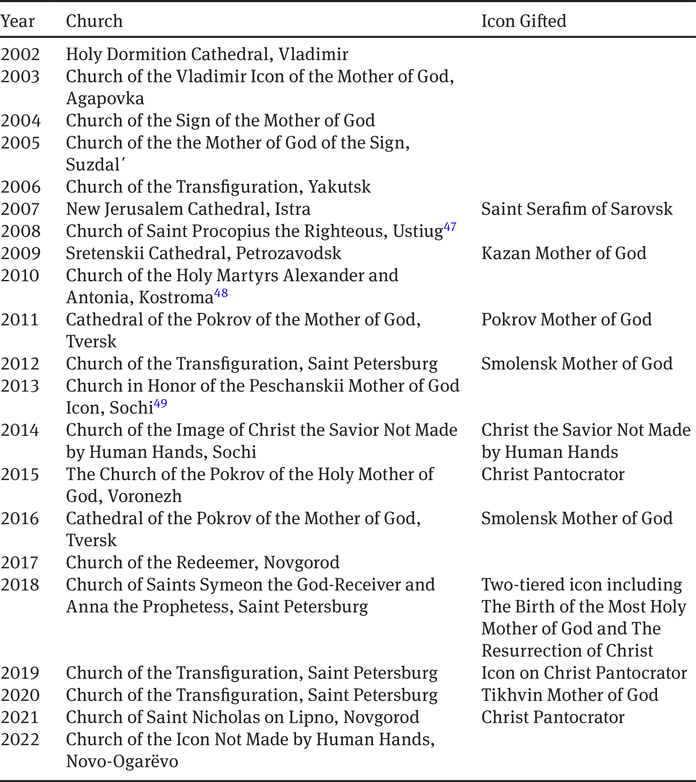

Putin's practice of leaving the capital at Christmas is better understood as a carefully crafted “going out among the people” (vykhod v narod) that uses the lexicon of icons to curate Putin's image as the people's president (he is often asked by individuals for help in minor bureaucratic or financial issues) and the nation's palladium. Although palladium icons were traditionally perceived as military commander and sovereign, their tendency to be Mother of God icons can soften the image of the leader associated with it.Footnote 46 As in the 2012 “Prayer,” the role of intercessor and protector is underscored by milieus that link Putin with Marian icons. Almost half of the churches Putin has visited are associated with the Mother of God or house notable icons dedicated to her (Table 2).

Table 2 Putin's Christmas Visits (2002–2022); *As prime minister (2009–2012)

To mark the occasion of his visit, Putin most often (55 percent of the time) gifts an icon of the Mother of God. In a notable example, he attended the 2013 Christmas services at the Saint George-Trinity Women's Monastery in Lesnoe, near Sochi, where six out of its seven churches are dedicated to the Mother of God and her icons (the Vladimir, the Burning Bush, Assuage My Sorrows, Softener of Evil Hearts, the Peschanskaia, and the Abbess of Mount Athos). The Kremlin website chose to publish four photographs from the service that show Putin with a small crowd inside the cozy, candlelit Church in Honor of the Peschanskaia Mother of God icon (located in the same building as the Church in Honor of the Vladimir Mother of God icon and the Church in Honor of the icon of the Mother of God Abbess of Mount Athos). In this series of images, the camera angle narrows progressively until it captures Putin in the familiar pose of a Mother of God icon (Figure 1).Footnote 50 While its composition actualizes the symbolic connection between Putin and the icon, the photo also reflects iconographical principles. Unlike earlier crowd shots, the attention of the people in the photograph is now drawn in various directions, which introduces the element of multiple perspectives that results in continual eye movement of the viewer of icons.Footnote 51 The woman in the green headscarf and more traditional dress has re-positioned herself closer to Putin; her downward gaze directs attention to Putin and the boy. Her clothing adds both an archaic feel to the image and introduces the life-affirming green that figures so prominently in icons of the nativity.Footnote 52

Figure 1. Christmas 2013. Sochi.

The publication of this image unleashed an online spate of mock captions that suggested the boy may have been frightened by the encounter.Footnote 53 But Putin's Christmas greeting to the nation underscored the true intentions of the iconographical reference, highlighting the importance of gentle Christian virtues (faith, hope, and love) and describing the season as “a time of charity and mercy, of sincere consideration of those who need our care and concern.”Footnote 54 At the same time, Putin emphasized his role as Russia's protector, using the same term (opora) that the National Committee +60 linked through reverse rhyme to the protecting veil (pokrov) of the Mother of God in their “Prayer to Putin.” Preparing to host the world at the Winter Olympic Games in Sochi in 2014, Putin seemed to imagine “traditional spiritual and moral values” as a protective and unifying encirclement saying, “[The holiday] unites us around (vokrug) traditional and moral values which play a special role in the history of Russia and serve as the pillar (opora) of our society.”Footnote 55

Christmas images of Putin surrounded by icons and children have become common fare on the Kremlin website, and their visual composition has become standardized as the loosely grouped shots of the early 2000s (Figure 2) gave way to more formal and intentional posing (Figure 3). These images of Putin at prayer have resulted in a now recognizable “type” of official portraiture in the tradition of imperial representations of the leader as “political god” or “earthly god” (zemnoi bog).Footnote 56 Such overlap between political portraiture and icons also introduces the notion of “presence” into Putin's Christmas visits. As Clemena Antonova notes, both imperial portrait and icon act as “container” of the person or divine prototype they represent or with whom they are associated.Footnote 57 The reverence accorded the iconographical representations of Lenin and Stalin and the brutal treatment of their statues in the early 1990s suggest that Soviet citizens also perceived this link between image and presence.Footnote 58

Figure 2. Christmas 2000. Moscow.

Figure 3. Christmas 2020. St. Petersburg.

Putin discourages the iconographical treatment of his likeness.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, his close association with icons allows him to participate in the charisma of iconographical subjects or, as in the case of the Christmas portraits, to engage with the sense of presence.Footnote 60 After Putin's 2003 visit to the Southern Ural village of Agapovka, for example, residents refer to the Church of the icon of the Vladimir Mother of God as the “church were Putin prayed.”Footnote 61 Thus, Putin's attendance at Christmas services designates the place as (politically) “sacred” and thereafter “protected” as his visit becomes part of the sacred narrative of the place and the gifted icons seem to stand watch. As Vera Shevzov notes, specific icons of the Mother of God are believed to “guard” the country's borders to the north (Tikhvin), south (Iveron), east (Kazan), west (Pochaev and Smolensk), and center (Vladimir).Footnote 62 Putin's Christmas appearances reveal a similar geographic distribution of protective Mother of God icon types (Kazan, Smolensk, Tikhvin) to the north (Novgorod, Saint Petersburg, Petrozavodsk), south (Sochi, Voronezh), east (Ustiug, Yakutsk), west (Vladimir, Suzdal, Kostroma), and center (Moscow, Tver, Istra). One of Russia's greatest vulnerabilities is its sheer size, and the need to construct a narrative that it is safeguarded on all fronts seems as important as building actual defenses. Putin's visits to the Sochi region leading up the 2014 Winter Olympic Games or the 2015 visit to Voronezh, where he was pictured with refugee children from the Donbas region of Ukraine, show concerns with the integrity of Russia's cultural and geographical borders (Figure 4). Because icon ritual also revives memories of events association with the images (like tales of miraculous delivery from enemies), it is possible to understand Putin's perception of threats through the language of the icon.

Figure 4. Putin with Donbass refugees. 2015.

In 2022, Putin broke with tradition and spent Christmas services as the sole congregant in the Church of the Icon Not Made by Human Hands at his presidential residence near Moscow (Figure 5). Like images from the 2018 inaugural prayer service, Christmas photos that show Putin alone with clergy offer a new type of Christmas portraiture that combines his elevated political and spiritual roles to re-sacralize his leadership. Putin's Christmas address underscored partnerships between state and Orthodox Church as he emphasized the latter's role in social initiatives.Footnote 63 Doing so, he described in domestic terms the kind of public diplomacy the Church has conducted abroad since at least 2007, when Putin created The Russian World (Russki Mir) Fund.Footnote 64 In what looks like a personalized offshoot of The Russian World project, Putin has infused his own dealings with world leaders with the traditions and images of Orthodox icons in order to create and maintain political alliances. State-level exchanges of icons have also become a kind of loyalty test for “sacred” political friendships that, as in the case of Ukraine, can quickly turn into enmity.

Figure 5. Putin celebrates Christmas alone. 2022.

The End of the (Russian) World As We Know It

During the 2016 awards ceremony for the Russian Geographical Society, Putin quipped that “Russia's border doesn't end anywhere.”Footnote 65 In light of Russia's invasions of Crimea and mainland Ukraine, this facetious remark reveals the problematics of the sacred in Russia's diplomacy, especially programs like the Russian World. Much has been said about the “soft power” strategies of the Russian Orthodox Church (a member of the Russian World Foundation since 2009) that purport to strengthen historical and cultural ties with former Soviet states and to extend Russia's reach abroad by creating an “empire of diaspora” that reimagines national borders and cultivates the myth of a greater Slavic and Orthodox brotherhood of nations.Footnote 66 With similar political goals, Putin has used what might be called “icon diplomacy” to engage world leaders from a variety of faith traditions in the idiom of the icon and create “sacred” Russian space abroad by gifting, exchanging, and ritually interacting with icons during state visits (Table 3).Footnote 67 This process illustrates what Lidov and Avanesov describe as a semiotic “carrying over” or “transfer” of culturally significant or “semantic” space from one place to another through performative ritual actions key to Putin's icon diplomacy.Footnote 68 Along with the sacred space created through devotional interaction, the icons with which Putin interacts are often linked to significant historical events traditionally perceived as miraculous and convey a sense of sacred time as well. But while narratives of sacred histories may strengthen alliances through memories of common cultural experiences as in the case of Greece, Serbia, and other traditionally Orthodox countries, they can also create contested temporal territory. (Table 3)

Table 3 Putin's Icon Diplomacy, 2000–2020; *As prime minister (2009–2012)

The language of the icon that plays out in Putin's encounters with foreign leaders often reveals complex truths about political relationships. The construction of the Cathedral of the Holy Dormition in the predominantly Muslim capital of Astana, Kazakhstan, for example, established a spiritual “outpost” of Russian influence, an idea emphasized in the 2015 icon exchange between Putin and President Nursultan Nazarbayev. Putin gave the cathedral an icon of the Protecting Veil of the Mother of God, symbolically promising defense. In turn, by giving Putin a Feodorov or “Romanov” icon of the Mother of God—an image that “blessed” Putin's presidency in 2000 and, as the Metropolitan of Astana and Kazakhstan Aleksandr (Mogilev) noted during the visit, is considered a protectress of the Russian state—Nazarbayev acknowledged Putin's authority.Footnote 69 In another example, years of reciprocal visits and icon exchanges with Patriarch Feofil of Jerusalem did not preclude Putin from spending Orthodox Christmas day 2020 with Syrian president Bashar Al-Assad at the Cathedral of the Most Holy Mother of God in Damascus. With Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu looking on, Putin donated an icon of the Mother of God to the church before he and Assad lit candles to the cathedral's icons. Visiting the relics of Saint John the Baptist at the Umayyad Mosque on the same day and noting the “common moral values” and “universal humanitarian values” of Orthodoxy and Islam, Putin demonstrated in words and actions a major goal of his icon diplomacy: to create alliances among conservative cultures that might join him in questioning the universality of western liberal values.Footnote 70

For Putin, political alliances can take shape through the construction of actual sacred space. In 2010 when Roman Catholic and Orthodox Easter fell on the same date, Putin marked what he hoped was a new era of Russian-Polish relations. On that day he visited the site of the 1940 Katyn Massacre to lay the cornerstone for the Orthodox Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ and bestow on the church a Resurrection icon. In his dedication speech, Putin emphasized the transformative nature of the project—describing how it would turn a tragic place into a “sacred place” and unite people of all faiths as equal victims of Soviet repression (a move widely seen as an attempt to whitewash the historical responsibility of the Soviet regime). Putin's emphasis on the shared reverence for icons paralleled his claim to the sacred history of the tragedy:

With the construction of this cathedral this place, which was certainly associated with tragedy and crime, is turning into a sacred place (prevrashchaetsia v sviatoe mesto). Ordinary citizens and relatives of the Poles, Russians, and other peoples of the Soviet Union who are buried in the Katyn forest will be able to come here, put down flowers and pray. Remember your loved ones, remember the victims of the repression of the totalitarian regime. And remember to make sure it never happens again in our history. With the blessing of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, Orthodox icons honored by Orthodox and Catholics, especially in Poland, will be placed here. It will be another symbol that unites our peoples.Footnote 71

The icons that Putin gives to and receives from the Vatican seem to make even more grandiose claims to sacred territory. It is striking that, despite numerous visits in Rome with all three twenty-first century popes and the expressed desire for “interdenominational dialogue,” Putin has studiously disallowed the Holy Father to set foot on Russian soil. Even Pope John Paul II's historical 2004 decision to return to Russia the icon of the Mother of God of Kazan (the palladium believed to have secured Prince Dmitrii Pozharskii's victory over Polish-Catholic forces during Russia's Time of Troubles in 1612) gained entry only for the Pope's emissaries. Indeed, the only way the Vatican seems to get to Moscow is via gifts, like a majolica view of the Vatican Gardens or an etching of a view of Saint Peter's Basilica (the inspiration for St. Petersburg's Kazan Cathedral Square), given so Putin “would not forget Rome.”Footnote 72 Putin has responded to the Vatican's outreach with gifts that are equally symbolic of sacred space and history: a representation of Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Savior, volumes of the Orthodox Encyclopedia, and, most remarkably, icons that promote the idea that Moscow rather than Rome is the true heir of the Christian world. In 2013, for instance, Putin brought the Vatican an icon of the Vladimir Mother of God, the palladium and “master symbol” of the Russian state and a sign of Moscow's own covenant with Mary.Footnote 73 (Figure 6) And, in a 2019 visit to discuss Syria and Ukraine, Putin presented Pope Francis with a large and ornately covered Orthodox icon of Saints Peter and Paul, from whom both the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches claim descent. This icon challenged papal authority in several ways, claiming the keys of the kingdom of heaven in Saint Peter's right hand and making implicit references to Putin's native city of St. Petersburg, whose eighteenth-century architects strived to “surpass that which the Romans considered sufficient for their monuments.”Footnote 74

Figure 6. Putin presents Pope with an icon of the Vladimir Mother of God. Vatican. 2013.

In contrast, Putin has warmly hosted the late Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, whose controversial 2015 trip to the Crimean Peninsula was regarded as tacit support for Russia's 2014 annexation. Of note was Berlusconi's participation alongside Putin in rituals of icon veneration in the Cathedral of Saint Vladimir in the National Preserve of Tauric Chersoneses outside of Sevastopol, to which Putin gifted the analogous icon of Saint Vladimir. Berlusconi's presence and role in these activities seemed to ritually and politically validate Putin's perception of Crimea as “sacred” Russian space. Indeed, just months earlier in his address to the National Assembly, Putin—in a clear instance of “cultural semiotic transfer”—had symbolically relocated Jerusalem's Temple Mount to Crimea, where he pinpointed Russia's “spiritual” and political roots:

It is precisely in Crimea that the spiritual roots of a diverse but monolithic Russian state and Russian centralized government are located. For Russia, the Crimea, ancient Korsun, Chersoneses, and Sevastopol hold enormous civilizational and sacred meaning. It is like the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for those who profess Judaism or Islam. This is how we will regard it. From now on and forever.Footnote 75

In the past, Putin visited the Cathedral of Saint Vladimir (by legend the place where Prince Vladimir was Christened) with Ukrainian presidents Leonid Kuchma (2001) and Viktor Yanukovych (2013). But with these words—understood as political propaganda in Ukraine—he denoted Crimea as sacred space for Russia alone.Footnote 76 Since then, Putin's designation of the peninsula as “holy” (sviatoi) or “sacred” (sakral΄nyi) Russian territory has become commonplace.Footnote 77

Given such incursions into sacred history, Putin has understandably produced mixed results when he prods Orthodox “partner” states to participate in performative aspects of his icon diplomacy. In 2000, Putin “reminded” Ukraine's President Leonid Kuchma (fresh from a summit of the Central European Initiative states) of the sacred ties among his country, Russia, and Belarus with what amounted to a command performance and presentation of icons at the site of one of largest WWII tank battles between German and Soviet forces.Footnote 78 In contrast, Aliaksandar Lukashenka—until recently a self-described “Orthodox atheist”—has become increasingly proficient in the symbolic language of icons. Starting in 2014, Lukashenka adopted Putin's habit of attending Christmas church service (always in Minsk). In a 2018 meeting in Sochi, he gave Putin a Guardian Angel icon, observing that Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus need to act as each other's “guardians.”Footnote 79 In July 2019, Lukashenka accompanied Putin to the island monasteries of Valaam and Konevets, where the two leaders venerated and received icons. A year later, Lukashenka and an unidentified Russian “patron” funded the restoration of the Saint John the Baptist church near Minsk, which features in its courtyard a WWII monument to Soviet liberators. Lukashenka donated what is likely a Zhirovitsskaia Mother of God icon at the consecration, an event designed to distract attention from anti-government demonstrations taking place in the capital.Footnote 80

Despite Russia's political, economic, and religious efforts to keep its neighboring states within its sphere of influence, Ukraine's dramatic transition from “brother state” to “enemy” revealed the tenuous nature of Putin's icon diplomacy and the Russian World project itself. As Putin's most frequent international destination, Ukraine first seemed to offer a model historical, cultural, and spiritual partnership. Nearly 40 percent of Putin's visits to Ukraine and with Ukrainian leaders before 2014 included the veneration and exchange of icons at visits to churches and monasteries and at consecrations and meetings with leaders of the Orthodox Church. During a July 2013 visit to celebrate the 1025th anniversary of the Kyiv-Pechersk Monastery (the so-called “hub” of the Russian World in Kyiv that marked each presidential visit with a gifted icon) Putin promoted spiritual ties as the foundation of the Russian-Ukrainian “friendship.”Footnote 81 Delivered on the eve of the Maidan Revolution, his comments seem to imagine the “spiritual unity” (dukhovnoe edinstvo) of the two nations as a political marriage that only God could sunder:

Our spiritual unity is so durable (prochnyi) that is it not subject to the actions of any power—neither the power of the government or, if I allow myself to say, even the church. Because no matter how powerful human authority over people is, nothing can be stronger than the authority of God.Footnote 82

While he was speaking at the monastery, however, citizens in Kyiv were protesting the alliance and, less than a year after Putin's last engagement with icons in Ukraine, the notion of the Russian World there was soundly rejected. In fact, by spring 2022, the phrase “Russian World” had become an ironic nickname for Russia's invasion and the destruction it wreaked, inverting its relationship with any sense of the sacred.

The semantic battle for the sacred continues in Russia's war in Ukraine with icons acting as important visual idioms for territorial claims on real and imagined front lines. Icons of the Mother of God, for example, are used on both sides as symbolic defenses and expressions of regional exceptionalism.Footnote 83 Like Putin, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky does not want his image treated as an icon, but neither does he avoid the idiom of the icon.Footnote 84 Indeed, Zelensky also uses iconographical images to bolster national pride and combat Russian pretensions to Ukrainian territory and history. Two clear and dramatic examples show how Zelensky both understands and appropriates Putin's lexicon of the sacred. In the first instance on April 9, 2022, Zelensky announced that the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the United States had returned the icon of Saint Mikola (Nicholas) Mokryi (“the Wet”) to Kyiv, where it had been housed in the Cathedral of Saint Sophia until World War II.Footnote 85 Credited with saving the life of an infant who fell into the Dnieper River in 1091, the image, as Zelensky noted, is considered the first miraculous icon in Kyivan Rus΄ (and perhaps the first icon of Saint Nicholas in Rus΄). In other words, the marvelous icon sanctified Kyivan lands long before the existence of the Russian state, thus legitimizing Ukraine's claims to its own sacred territory, history, and sovereignty:

I want the return of this sacred object to become an important symbol for everyone. A fundamental symbol. A symbol that we will restore to Ukraine all that is ours. Everything Ukrainian. We will restore all of our people. And we will surely restore justice—our complete control over our land.Footnote 86

Zelensky's identification of Saint Nicholas with the nation of Ukraine reflects the deep history of the saint's cult in early Rus΄, where, in the eleventh century, Grand Prince Sviatoslav Iaroslavich took Nicholas as his baptismal name and incorporated the image of the saint on his princely seals.Footnote 87 Zelensky's invocation of an Orthodox icon at this point in Ukraine's history can be understood not as a religious act (the president is Jewish), but a political gesture that imagines the icon as a symbol of Ukraine's right to self-determination.

The second example of Zelensky's icon “defensive” took place two weeks later at Easter in the Cathedral of Saint Sophia. There, Zelensky stood in front of the iconostasis to lead a Paschal prayer for deliverance from the invading Russian forces and to explain the national significance of the church's main icon—the same “Impenetrable Wall” Mother of God icon referenced in the 2012 “Prayer to Putin.” Like the Putin prayer and its nineteenth-century subtext, Zelensky's Easter prayer drew on the tradition of the akafist to the Mother of God. Although addressed to God, Zelensky's words created a symbolic correlate of the icon above him (which he refers to as the Mother of God “Oranta,” or “at prayer”) as he led the nation in prayer. At the same time, Zelensky sought to transcend the boundaries of faith traditions and frame the icon as a universal symbol of Ukrainian unity and national defense, the “impenetrable wall of the state,” “protectress,” and “immutable pillar” against the enemy from the east.

On our side we have truth, our people, the Lord, and the highest heavenly radiance. The strength of the protectress (zastupnitsa) of humankind, the Mother of God Oranta. She is right here above me; she is above us all. The immutable pillar (stovp) of the Church of Christ, the impenetrable wall of state (nerushima stina derzhavi). While there is the Mother of God Oranta —there is Saint Sophia's, and with her stands Kyiv, and with them—all of Ukraine.Footnote 88

If the text of Zelensky's remarks coopt familiar terms in the lexicon of political iconography, the professionally produced video version of the speech shows his mastery over Putin's visual idiom of icons, particularly the emphasis on his sacerdotal role during the 2018 inauguration and 2022 Christmas services. A semiotic analysis of Zelensky's 2022 Easter address shows similar dynamics of sacralization. Framed by the Royal Doors of the iconostasis, Zelensky becomes a visual part of the row of icons of Christ, the Mother of God, and other saints.Footnote 89 Zelensky stands alone just feet from the “holiest of holies” beyond the icon screen and faces an imagined congregation, symbolically assuming the liturgical status of “earthly” protector of his nation that Putin has long sought for himself. By necessity, Zelensky is playing a role he avoided early in his presidency—that of a living (political) icon for Ukraine. Indeed, as the video of his Easter address narrows to close up and Zelensky recites the impassioned prayer of protection for the people and cities of Ukraine, his newly bearded face, intense, lachrymose eyes, and recognizable olive drab clothing convey all the semiotic markings of a portrait of sacred leadership cum saintly icon.Footnote 90 On the symbolic battlefield of the sacred Zelensky presents Putin with a formidable semiotic challenge. In a matter of a few, terrible months of war, he accomplished what the messianic Putin has been trying to establish for decades—the nearly world-wide perception of the president as protector of the nation and chosen leader of the sacred mission for Ukraine's sovereignty and its right to exist.

If Putin intended to reintroduce the notion of the sacred back into the political sphere, he may have succeeded with his curated interactions with icons, which, over the course of his long political career, have functioned politically as persuasion, coercion, and war. Moving forward, it will be critical to understand the idiom of the icon as an important and persistent form of Russian political discourse. No matter what the outcome of the war in Ukraine, for example, recognizing it as a sacred cause will help us understand the roots and potential consequences of the violence. The past two decades show how the semiotic language of icons has been adopted and amplified by Putin's political allies and surrogates from Dmitrii and Svetlana Medvedev, regional politicians, Russia's business community, and friends of the president (like Vladimir Iakunin and Igor Sechin) who lead conservative social organizations and oversee the programmatic restoration of Russia's holy sites. Like Putin, the political elite in Russia may favor the flexibility and agility of this kind of semiotic signaling in the absence of true political ideology.Footnote 91 Given the Aesopic nature of Putin's politics of the sacred, his engagement with Orthodox icons, and his willingness to engage in “sacred” war, we run the risk of dangerous misunderstandings if we cannot fathom this language of the icon. Ultimately, and because there will assuredly be less direct interaction with Russia in the foreseeable future, it is critical to understand Putin's political use of icons, which may continue to indicate what space and time he considers sacred enough to defend.